From Zerfass to Osmer and the Missing Black African Voice in Search of a Relevant Practical Theology Approach in Contemporary Decolonisation Conversations in South Africa: An Emic Reflection from North-West University (NWU)

Abstract

1. Introduction

[d]espite the multiple identities an African could possess, the unique experience of African community in its fullness, defines the African. This argument is predicated on the fact that most discursive, political, and cultural definitions of Africans and Africa do not countenance the locale of African community as underscored here as perhaps the most resilient value that wrests with those contentious notions of Africa and being an African.

2. About North-West University Practical Theology

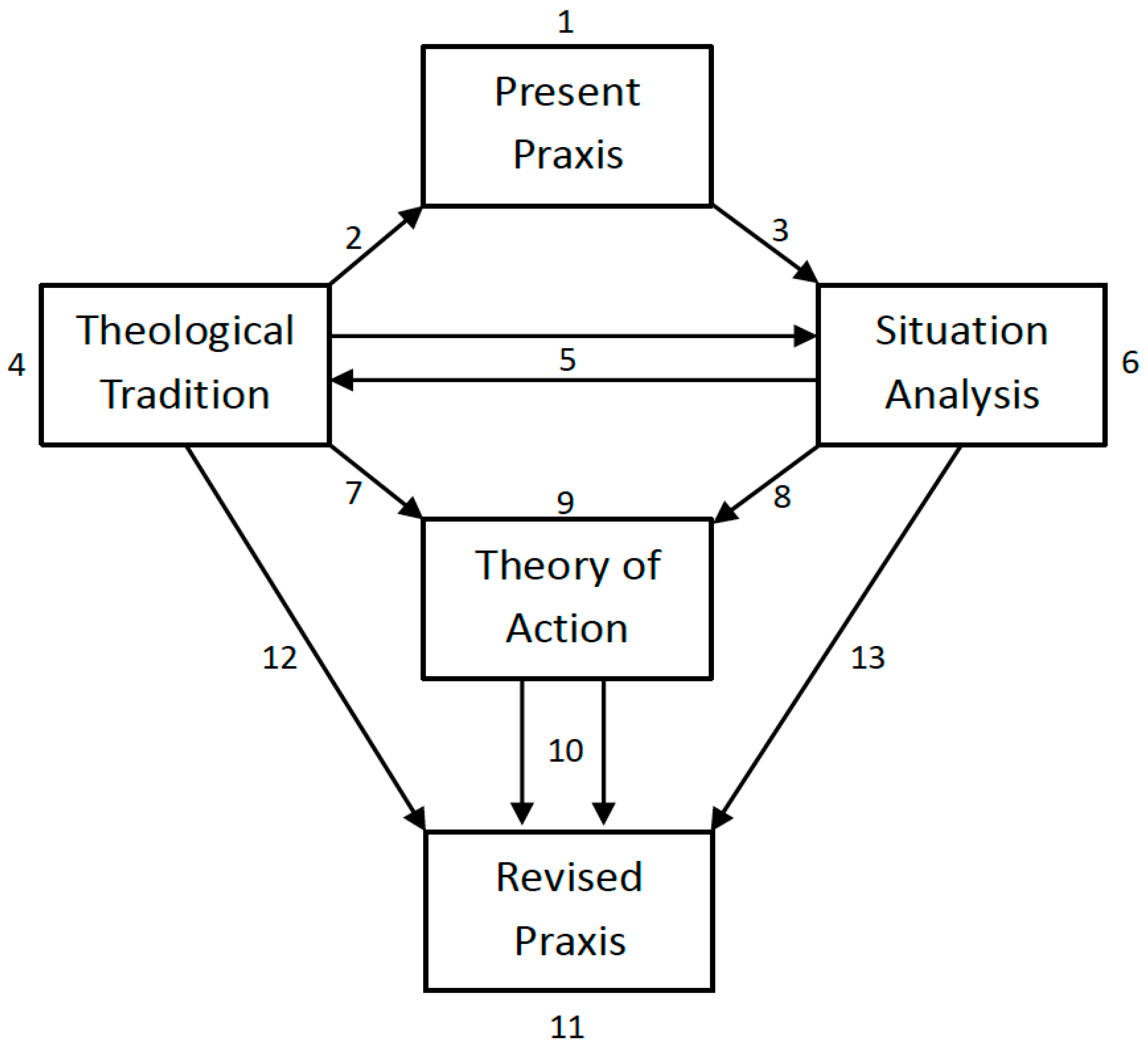

[t]he reason why Zerfass’s model is used in the methodological approach of several practical theological studies is probably located in the framework it provides for the investigation of different levels of hermeneutic interaction between theological tradition and current situation, norm and practice, the ideal and real, theology and other humanities. Defining and integrating hermeneutic interaction into theory formation ensures that basic theory does not remain suspended in the air, practice theory does not float around without an anchor and metatheory is not left unaccounted for.

The Faculty of Theology of the North-West University practises the science of Theology on a Reformational foundation. This implies recognition that the Word of God, the Bible, originated through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit and that the Bible is, therefore, inspired and authoritative… In its practice of Theology, the aim of the Faculty, within the unique nature of Theology, is to serve the church and society, both nationally and internationally, through the enhancement of the Christian faith, the reformation of the church, and the moral renewal of society

Many different versions of practical theology have been developed based on the different choices of four parameters, namely (1) the object, running the gamut from religious clergy through the faith community and the religious traditions to culture and society; (2) the method, approaching praxis empirically, phenomenologically, critically, constructively, or dialogically; (3) the role of the researcher as participant, consultant, referee, or observer; and (4) the audience, being primarily the academy, the church, or society.

Practical Theology is (1) an activity of believers seeking to sustain a life of reflective faith in everyday life, (2) a method or way of analysing theology in practice used by religious leaders and by teachers and students across the theological curriculum, (3) a curricular area in theological education focused on ministerial practice and sub-specialities, and (4) an academic discipline pursued by a smaller subset of scholars to support and sustain these first three enterprises.

has evolved out of three historically different styles of theology with differing concepts of and methodological approaches toward praxis: pastoral, empirical, and public theology. These three styles correlate with the three audiences Tracy described. Pastoral theology is closest to the audience of the church, empirical theology to the audience of the academy, public theology to the audience of society.

Theology is practical, therefore, but the practice is also ‘theological’—‘practice is taken to be theologically significant.’ Theology is not simply a body of knowledge and understanding that is tested or ‘applied’ in practice or as it translates into action. In this respect, practical theology opts for a dialogical model of theory and practice. Practical Theologians are congenitally more comfortable with two-way rather than one-way streets. Practical Theologians will hold that people’s practice is informed, shaped, perhaps, by doctrine—or even dictated by it. But Practical Theologians want to keep asserting that doctrine is informed, shaped, and even dictated by practice.

3. Context of Practical Theology in South Africa

Germane to the business of African Theology are questions of African spiritual, economic, religious and theological agency, which business is to reflect theologically on religion in the world, especially religion and Christianity in Africa. Accordingly, contemporary African Theology tackles several themes that speak to the problems and promises of religion in Africa and the rest of the world.

4. Considerations and Departure Points for Practical Theology at NWU and South Africa

It should come as no surprise, therefore, given practical theology’s complex location and aims, that scholars who profess expertise in the discipline encounter a variety of intellectual and practical conundrums as we do our work and live out our vocations. The challenges are not ours alone, however, but plague our scholarly peers and spill over into the lives of those who make their way from our schools into a diversity of professional roles that require practical embodiment of religious beliefs in concrete contexts.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | I use the word Africa in this article to refer to Africa’s geographical location (continent), however with particular reference to Black Africans who experienced exclusion and disadvantages due to colonialism. These people share the definition espoused by Igboin (2021), Masamba ma Mpolo (2013), and many others (see Igboin 2021, pp. 14–15). This notion of Africa is in line with the argument thread in this article. While the narrow context of this paper is South Africa, its related context is broader Africa. |

| 2 | Model C school is “a state school in South Africa that used to be for white children only and is now mixed. Model C schools are generally considered better than township schools” (Macmillandictionary.com n.d.) |

References

- Acolatse, Esther. 2014. For Freedom or Bondage? A Critique of African Pastoral Practices. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Acolatse, Esther. 2018. Powers Principalities and the Spirit: Biblical Realism and the West. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Agang, Sunday Bobai. 2020. The Need for Public Theology in Africa. In African Public Theology. Edited by Sunday Bobai Agang, H. Jurgens Hendriks and Dion A. Forster. Carlisle: Langham Publishing, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Agang, Sunday Bobai, H. Jurgens Hendriks, and Dion A Forster, eds. 2020. African Public Theology. Carlisle: Langham Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, Tom. 2016. Why does practice matter theologically? In Conundrums in Practical Theology. Edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Joyce Ann Mercer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 8–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, Tom, and Kathleen Turpin. 2014. White practical theology. In Opening the Field of Practical Theology. Edited by Kathleen A. Cahalan and Gordon S. Mikoski. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 251–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Paul. 2009. Christian intellectual responsibilities in modern Africa. Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology 28: 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- De Wet, F. W. 2006. The application of Rolf Zerfass’ss action scientific model in practical-theological theory formation-a Reformed perspective. In die Skriflig 40: 57–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, Jaco S. 2012. South Africa. In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Practical Theology. Edited by Bonnie Miller-McLemore. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 505–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, Jaco S. 2016. Knowledge, Subjectivity, (De) Coloniality, and the Conundrum of Reflexivity. In Conundrums in Practical Theology. Edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Joyce Ann Mercer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 90–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, Jaco S. 2017. Practical theology and the call for the decolonisation of higher education in South Africa: Reflections and proposals. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73: a4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, William E. B. 2008. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1990. The Wretched of the Earth, Trans. Constance Farrington. London: Penguin Books. First Published 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzevoort, R. Ruard. 2009. Forks in the Road When Tracing the Sacred: Practical Theology as Hermeneutics of Lived Religion. Keynote at the International Academy of Practical Theology, Chicago. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.489.9830 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Ganzevoort, R. Ruard. 2022. Cultural Hermeneutics of Religion. In International Handbook of Practical Theology: A Global Approach. Edited by Birgit Weyel, Wilhelm Gräb, Emmanuel Y. Lartey and Cas Wepener. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 633–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzevoort, R. Ruard, and Johan Roeland. 2014. Lived religion: The praxis of Practical Theology. International Journal of Practical Theology 18: 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereformeerde Kerke in Suid-Afrika—GKSA. 2022. Theological School. Available online: https://eng.gksa.org.za/theological-school/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Graham, Elaine L. 2017a. On becoming a practical theologian: Past, present and future tenses. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73: a4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Elaine. 2017b. The state of the art: Practical theology yesterday, today and tomorrow: New directions in practical theology. Theology 120: 172–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräb, Wilhelm. 2022. Life Interpretation and Religion. In International Handbook of Practical Theology: A Global Approach. Edited by Birgit Weyel, Wilhelm Gräb, Emmanuel Y. Lartey and Cas Wepener. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 169–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Elle. 2022. Inside the Fastest Growing Religious Movement on Earth. Available online: https://www.premierchristianity.com/features/inside-the-fastest-growing-religious-movement-on-earth/6009.article (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Igboin, Benson Ohihon. 2021. I Am an African. Religions 12: 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knighton, Ben. 2004. Issues of African Theology at the turn of the Millennium. Transformation 21: 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, Emmanuel Y. 2013. Postcolonializing God: An African Practical Theology. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lartey, Emmanuel Y. 2022. Postcolonial Studies in Practical Theology. In International Handbook of Practical Theology: A Global Approach. Edited by Birgit Weyel, Wilhelm Gräb, Emmanuel Y. Lartey and Cas Wepener. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 661–75. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillandictionary.com. n.d. Model C. Available online: https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/model-c#:~:text=DEFINITIONS1,to%20a%20Model%20C%20school (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Magezi, Christopher, and Jacob T. Igba. 2018. African theology and African Christology: Difficulty and complexity in contemporary definitions and methodological frameworks. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74: 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magezi, Vhumani. 2018. Changing family patterns from rural to urban and living in the in-between: A public practical theological responsive ministerial approach in Africa. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74: 5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magezi, Vhumani. 2019. Political leadership transformation through churches as civic democratic spaces in Africa: A public practical theological approach. In Reforming Practical Theology: The Politics of Body and Space—IAPT.CS. Edited by Auli Vähäkangas, Sivert Angel and Kirstine Helboe Johansen. Tuebingen: Tubingen University, pp. 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magezi, Vhumani. 2022. African publics and the role of Christianity in fostering human-hood: A public pastoral care proposition within African pluralistic contexts. Paper presented at Inaugural Lecture, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark Campus, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa, June 15. [Google Scholar]

- Maluleke, Tinyiko. 2020. Racism en Route: An African Perspective. The Ecumenical Review 72: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluleke, Tinyiko. 2022. Currents and Cross-Currents on the Black and African Theology Landscape Today: A Thematic Survey. Black Theology 20: 112–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masamba ma Mpolo. 2013. Spirituality and counselling for liberation: The context and praxis of African pastoral activities and psychology. In Voices from Africa on Pastoral Care: Contributions in International Seminars 1988–2008. Edited by Karl Federschmidt, Klaus Temme and Helmut Weiss. Magazine of the Society for Intercultural Pastoral Care and Counselling (SIPCC). pp. 7–18. Available online: www1.ekir.de/sipcc/downloads/IPCC-020-txt.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2016).

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. 2012. Five Misunderstandings about Practical Theology. International Journal of Practical Theology (IJPT) 16: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. 2022. Understanding Lived Theology: Is Qualitative Research the Best or Only Way? In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Theology and Qualitative Research. Edited by Knut Tveitereid and Pete Ward. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 461–70. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J., and Joyce Ann Mercer. 2016. Introduction. In Conundrums in Practical Theology. Edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Joyce Ann Mercer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mucherera, Tapiwa N., and Emmanuel Y. Lartey. 2017. Pastoral Care, Health, Healing, and Wholeness in African Contexts: Methodology, Context, and Issues—African Practical Theology, Vol. 1. Oregon: Wipf & Stock. [Google Scholar]

- Nwachuku, Daisy N. 2012. West Africa. In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Practical Theology. Edited by Bonnie Miller-McLemore. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 515–24. [Google Scholar]

- NWU Ancient Languages and Text Studies. 2022. School of Ancient Languages and Text Studies. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/ancient-language-and-text-studies/home (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- NWU Ancient Texts. 2022. Ancient Texts: Text, Context, and Reception. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/ancient-texts (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- NWU Minister Training. 2022. Minister Training. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/minister-training (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- NWU Practical-Theological Perspectives. 2022. Practical-Theological Perspectives. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/unit-reformed-theology-and-development-sa-society/practical-theological-perspectives (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- NWU Practical Theology. 2022. Practical Theology. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/christian-ministry-and-leadership/practical-theology (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- NWU Public Practical Theology and Civil Society. 2022. Public Practical Theology and Civil Society. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/unit-reformed-theology-and-development-sa-society/public-practical-theology-and-civil-society (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- NWU Theology. 2022. Theology. Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/theology/theology-reformational-foundation (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- NWU URT. 2022. Unit for Reformational Theology and the Development of the South African Society (URT). Available online: https://theology.nwu.ac.za/unit-reformational-theology-and-development-sa-society (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Osmer, Richard R. 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Hee-Kyu Heidi. 2014. Toward a Pastoral Theological Phenomenology: Constructing a Reflexive and Relational Phenomenological Method from a Postcolonial Perspective. Journal of Pastoral Theology 24: 3-1–3-21. [Google Scholar]

- Roest, Henk. 2020. Collaborative Practical Theology: Engaging Practitioners in Research on Christian Practices. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Kevin G. 2013. Integrated Theology: Discerning God’s Will in Our World. Johannesburg: South African Theological Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. 2022. Distribution of the Population of Sub-Saharan Africa as of 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1282636/distribution-of-religions-in-sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Stoddart, Eric. 2014. Advancing Practical Theology: Critical Discipleship for Disturbing Times. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tiénou, Tite. 1990. Indigenous African Christian theologies: The uphill road. International Bulletin of Missionary Research 14: 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, Andrew. 2008. Bediako Kwame. Available online: https://dacb.org/stories/ghana/bediako-kwame/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Weyel, Birgit, Wilhelm Gräb, Emmanuel Y. Lartey, and Cas Wepener. 2022. Introduction. In International Handbook of Practical Theology: A Global Approach. Edited by Birgit Weyel, Wilhelm Gräb, Emmanuel Y. Lartey and Cas Wepener. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zerfass, Rolf. 1974. Praktische Theologie als Handlungswissenschaft. In Praktische Theologie Heute. Edited by Ferdinand H. Klosterman and Rolf Zerfass. Translated by Roger A. Tucker, and Schwär Walter. München: Kaiser Grünewald, pp. 164–77. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magezi, V. From Zerfass to Osmer and the Missing Black African Voice in Search of a Relevant Practical Theology Approach in Contemporary Decolonisation Conversations in South Africa: An Emic Reflection from North-West University (NWU). Religions 2023, 14, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050676

Magezi V. From Zerfass to Osmer and the Missing Black African Voice in Search of a Relevant Practical Theology Approach in Contemporary Decolonisation Conversations in South Africa: An Emic Reflection from North-West University (NWU). Religions. 2023; 14(5):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050676

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagezi, Vhumani. 2023. "From Zerfass to Osmer and the Missing Black African Voice in Search of a Relevant Practical Theology Approach in Contemporary Decolonisation Conversations in South Africa: An Emic Reflection from North-West University (NWU)" Religions 14, no. 5: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050676

APA StyleMagezi, V. (2023). From Zerfass to Osmer and the Missing Black African Voice in Search of a Relevant Practical Theology Approach in Contemporary Decolonisation Conversations in South Africa: An Emic Reflection from North-West University (NWU). Religions, 14(5), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050676