Abstract

Due to its strategic position in the Mediterranean Sea, Sicily was a place of multiple cultural contaminations and commercial exchanges throughout the early modern era. Trade, piracy, and even slavery implemented continuous contacts between populations from opposing shores, regardless of their different religious beliefs. Yet, the island was also intended as a Christian bulwark against the Islamic world and its institutions fostered anti-Muslim prejudices. To date, this discrepancy has been little investigated, but the responsibilities of art in fueling discriminatory attitudes have been explored even less. Drawing on Francisco Bethencourt’s idea that racism is motivated by political projects, this paper illustrates the complicity of art in reinforcing prejudices for political interests. To do so, it explores the 1725 frescoes by the Flemish painter Guglielmo Borremans (1670–1744) in the church of the Forty Martyrs and Saint Ranieri of the Pisan Nation, in Palermo. In the face of persistent multiculturalism in the daily life of the population, these frescoes affirmed the supremacy of Pisa as a victorious guardian of Christianity in the Mediterranean. In this way, they celebrated the urban nobility of Pisan descent, while disguising the problematic identity of its enemy.

Keywords:

Palermo; Pisa; Guglielmo Borremans; Muslims; prejudices; eighteenth century; decoloniality 1. Introduction

As Edward Said incisively argued, since the late eighteenth century, “the Orient” had been an imaginative construction by Europeans of what lay beyond the borders of the old continent (Said [1978] 1995). The schematization of its otherness aimed at its comprehension within known—that is, European—structures of thought. While facilitating the construction of the very idea of Europe (Schmidt 2015), this schematization, however, ended up altering the scholarly perception of non-Europe and creating the idea of opposing and non-dialoguing fronts. Since Said’s book Orientalism a broader academic awareness of the existence of dominant discourses affecting Western perceptions of non-Western countries has grown. This awareness has promoted new attempts at disconnecting research from superimposed paradigms, more space for non-Western scholars (especially those living in the diaspora), and open debate on curricular programmes in education. Yet, this process has been slow and is far from a conclusion. Additionally, it has taken a long time to involve European art history, a discipline closely related to Eurocentrism (Barker 2017).

The world of fine arts long justified and glorified the ruthless business ventures perpetrated by European powers to the detriment of other countries. To date, the civil protests that have smeared and overturned statues of racist perpetrators around the world have pushed for a rethinking of the neutrality of art. European institutions started to seek new perspectives on their own cultural heritage. In 2021, for instance, the Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam, while opening its Slavery exhibition, added 77 labels to artworks in its permanent collection to explore the relationship between them and Dutch colonialism. Yet, attempts such as this, as honourable as they are, risk limiting the debate to the dualistic opposition between colonizing and colonized countries, stigmatized as the West and the rest of the world. This approach has driven scholars to focus mainly on the British, Dutch, and—to a lesser extent—Spanish Empires and on their colonies across the ocean. This reiterates the binary contrast of Orientalism, albeit with a different aim, and risks losing sight of the complex processes of negotiation and adaptation existing in the early modern age. Conversely, this complexity can be traced by focusing on the Mediterranean countries. The inhabitants of these territories experienced situations of conflict and suspicion with peoples of different ethnic descent, religious beliefs, and cultural backgrounds, but also engaged with them on an equal footing for political and commercial agreements.

On the intersection between Italian art production and racial discrimination, the response of art historians has been slow in coming (Howie 2022). Still in 2010 publications on the specific relationship between the Italian Renaissance and the Muslim world were rather scarce (Trivellato 2010, p. 132). Underpinning this delay, there was probably what Said decried as the limited predisposition of scholars to address issues that could embarrass their consciences or put them under social pressure (Said [1978] 1995, p. 96). More recently, however, a certain cultural liveliness on the subject has arisen from a fruitful collaboration between Italian and Spanish scholars. In 2019 the book Jews and Muslims Made Visible in Christian Iberia and Beyond, 14th to 18th Centuries questioned the effectiveness of the category of otherness to investigate the relationship between West and East. The concern that the editors Borja Franco Llopis and Antonio Urquizar-Herrera expressed was that this binary oppositional approach excluded a priori the complexities and nuances of liminal contexts that were subject to influences from both cultural poles. Following the same insight, in 2021 two collections of essays, both edited by Laura Stagno and Franco Llopis Borja, dealt with the iconography of religious otherness by challenging the stigmatisation of the two fronts and approaching the complexity of the Iberian and Italian peninsulas.

In line with the enduring dearth of interest in the art of Spanish Italy (Cole 2013), however, these recent publications dealt with Sicily only marginally. Compared to the Genoese case, which has been investigated in much more depth, Sicily raises two issues that complicate the general picture and invite further investigations. First, in Sicily the Orient was not a distant and abstract entity, but a domestic presence. The island had been dominated by the Arabs, who were in Palermo from 831 to 1072. Furthermore, throughout the early modern period, the Sicilians maintained trade with North Africa while their cities were home to some Muslims. Unsurprisingly, the category of otherness has been called into question for this context, even regarding nineteenth-century orientalism (Mallette 2005). Secondly, the island had been under foreign rule since 1412. In the city of Palermo numerous factions, such as the viceroy, the Senate, the Parliament, the clergy, and the manifold urban associations daily negotiated their own political and social space through articulated tactics. In the formation of any (pre)judgment towards Muslims, the actions and attitudes of the different stakeholders intertwined, sometimes in discordant and even contradictory ways.1 To clarify the facets of this complex reality, it is urgent not only to explore the extent of the anti-Islamic prejudices circulating in Sicily and the way they intersected with its multicultural history, but also to unravel the tangle of responsibilities of the parties involved and to investigate what the role of art in all this was.

On their part, Sicilian art historians, de-facto the main people involved in research on those areas, have long neglected the history of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, seen as an age of endured dominations (Cochrane 1986, p. 195). When in the 1980s the interest in Baroque art grew, the attention of local scholars focused more on technical data, archival discoveries, and stylistic variations than on broader, underpinning theoretical issues. While confrontations between Sicilians and other Mediterranean peoples have been studied from a historical perspective focusing on military clashes, piracy, and the slave trade (amongst others, Fiume 2009; Cancila 2007; Bono 1989, 1993, 2005; Bonaffini 1983a, 1983b, 1997, 2003; Marrone 1972), art historians hardly opened their investigations to interdisciplinary discussions. Being detached from the liveliness of the theoretical debate, it is not surprising that this self-referential approach to the discipline has had a long life. The case under inquiry is an example of this. In June 1982 the Istituto Storico Siciliano held a four-day congress on the secular relationship between Pisa and Palermo, which produced a volume with 16 essays. Two of them were dedicated to the long-neglected Chiesa dei Santi Quaranta Martiri e di San Ranieri dei Nobili Pisani alla Guilla in Palermo (Church of the Forty Martyrs, for brevity) and to its frescoes by Guglielmo Borremans (1670–1744). The volume is a valuable source of information that this paper also made use of, but inside it there is no dialogue between disciplines. The two art historians dealing with the church limited their investigation mainly to a stylistic analysis of the frescoes (Brugnò 1983; Guttilla 1983). Further, in the following forty years, many publications used the same approach for the study of Borremans and his works and, unsurprisingly, they added little more than new data to the topic.2

The purpose of this work is to give input in a different direction. To do this, this paper drew on Francisco Bethencourt’s idea that racism is motivated by political projects that use differences in language, religion, and geographical origin to justify hierarchies and the management of space (Bethencourt 2013). In this sense, racism anticipates both colonization processes and scientific theories on race. It has been used to identify opponents to a proposed political project as the Others. This produced the political exclusion—if not the definitive expulsion—of these opponents while determining the increasing sense of identity and belonging of those who remained. In this sense, the long process of Latinization of Sicily was marked by the establishment of some to the detriment of others. In particular, this paper argues that, in eighteenth-century Palermo, Borremans’ frescoes still proposed the binary opposition between Christians and Muslims, on which the Pisan aristocracy had conquered its space and power in the city.

2. Another Story

In the Sicilian history that precedes Borremans’ frescoes, two major projects used this method to legitimize new social and political orders. The first was the recovery of Sicily to Latin Christianity that started with the Norman conquest (1071–1092). This project, pursued by both the House of Hauteville (1130–1198) and the House of Hohenstaufen (1198–1266), slowly but steadily produced the integration of the Byzantine Greeks (Orthodox Christians) into the Latin Church and the eradication of the Kalbid Arabs (Muslims). The second project was the incorporation of the island into the Spanish Empire. The Sicilian revolt against the French Angevins, known as the Vespers (1282), brought the island under Spanish political influence. However, its incorporation was only fully implemented when the Kingdom of Sicily became a Spanish viceroyalty, in 1412. Since then, Sicily was framed within the broader political project of Catholicization of the Mediterranean carried out by the Spanish monarchy. This project included the expulsion of the Jews from all the Spanish territories in 1492 and the fight against the Turkish threat, which had its peak in the long-celebrated battle of Lepanto (1571).

Beyond their various reasons, nuances and consequences, the cited events had an immense local resonance in the following centuries through literature and visual arts. Culture facilitated the persistence of these political projects and of the oppositions they fostered. What emerges from these oppositions is the arbitrariness in the approach to some people over others. At some point, North Africans, Greeks, and Jews were considered foreigners and enemies, regardless of their previous relationship with the Sicilian territory. Equally arbitrarily, Norman and Spanish conquerors seem to have been accepted and glorified, while French rulers were stigmatised as tyrants, thus giving preference to one political project over another. Classification and discrimination are processes of thinking that can be rather arbitrary because they involve a schematization of social relations (Said [1978] 1995, p. 54). In Palermo, however, this schematization clashed with the social multiculturalism existing in everyday life, both in the Norman period (Johns 2018) and during the Spanish viceroyalty (Baskins 2019).3 In other words, the daily confrontations between Christians and Muslims in the city were much more varied than what emerges from the picture sketched above. This suggests the extension of the complicity of culture in supporting these political projects and the interests that were intertwined with them.

The relationship between Palermo and Pisa itself underwent a process of simplification aiming to create a binary opposition, with all the contradictions that such a simplification entails. Some epigraphs celebrating the victories over the “Saracens” hang on the facade of the Pisa Cathedral. Two of them mention the “gens sicula” as the adversary who was defeated in Reggio (1005) and in Palermo (1064). Sicilians were all identified by Pisan history with the Kalbid Arabs ruling the island in that period, and, therefore, with Christians’ opponents. While the Reggio episode was a naval engagement between armed fighters, the latter was a raid against Palermo that took advantage of the confusion created by the concurrent Norman attacks. This raid resulted in burning five vessels anchored in the harbour, stealing another one, and sacking an extra moenia area. In the same way that the façade framed the slabs into its marble cladding, twelfth-century sources, such as the Annales Pisani and the Cronicon Pisanum, framed the episodes in the context of the holy war against the Muslim threat. The religious prejudice helped justify an expedition perpetrated against commercial competitors and mostly aimed at the theft of copious loot, which was used to build the Pisa Cathedral itself (Scalia 1983, pp. 19–20). More difficult to justify was probably another detail reported by the plaque: that is, the massacre of Palermo’s citizens while they tried to reach the city gates, and the devastation of their houses.

It is beyond the scope of this essay to investigate to what extent the binary contrast illustrated by the cited sources reflected the daily experience of the two cities in that period. Certainly, though, the identification of people from Palermo with the infidel made less sense after the city was conquered by the Normans. In a similar way, this conquest changed the role of the Pisans in Palermo from enemies to allies. The decrease in the number of Arab merchants in the city, due to the discriminatory politics of the Christian monarchs, favoured traders from Genoa, Pisa, and Venice, who secured footholds in the city, thus enhancing their commerce with the Orient. The ease of exchanges made it possible for art to contribute to the Latinization process. Emblematic in this sense is the case of the sculptor Bonanno Pisano, who worked both on a portal of the Cathedral of Pisa (1181) and on one of the Norman Cathedral of Monreale (1186), near Palermo. In both portals, the reliefs prefigured the path to salvation that anyone could take by entering the Christian church. In the fourteenth century, the flow of artworks between the two cities became constant. In 1371 a relic of the patron saint of Pisa Saint Ranieri (1118–1161) was donated to the queen of Sicily, thus sealing the alliance between Pisa and the House of Aragon. Between 1405 and 1406, a large number of Pisans took refuge in Palermo, fleeing from the Florentine advance and a second wave of migration occurred after the definitive capitulation of Pisa, in June 1509.

These migrations led to a first coexistence that produced repeated negotiations for space. The members of the Pisan Nation settled mainly near the harbour, in a commercial area called Loggia, where many other foreign merchants resided. At the beginning, the intention was not to create fractures but to integrate in the city. As part of their settlement, in July 1513 the Pisans joined the confraternity dedicated to the Forty Martyrs, reactivating the royal patronage of a previous oratory (Patricolo 1983, pp. 38–41). The Forty Martyrs was a cross-recognized cult with strong ties with oriental territories. The Forty were a group of Roman soldiers who were killed in 320 because of their Christian faith, in the freezing water of a lake near Sebastes, in Armenia Minor. Their cult was very much alive in orthodox religion, with monasteries in Syria, Greece, and Constantinople, but it also intersected with the Islamic world since the Ottoman Selim I (1470–1520) was a devout believer of the Forty and benefactor of their monastery in Mount Athos. The double dedication—of the confraternity and of the oratory—to the Forty Martyrs and to Saint Ranieri was probably a first ploy by Pisan exiles to insert themselves into the community quite smoothly. However, their strategy gradually aimed at complete control of the confraternity. At the beginning, the Pisans slightly outnumbered the other groups present in the association, but soon managed to replace them almost entirely. The 1513 document of aggregation made the confraternity open to all those who would flow from Pisa to Palermo, but closed to those who had no Pisan origin. Although membership was guaranteed to the heirs of the old confriars, within a few decades the Pisans obtained full power. This was facilitated by the fact that in 1524 the election of the rectors by lot was transformed into the result of a choice by the chiefs, who were usually of Pisan descent.

This goal of prominence was also pursued through the visual language. A double panel painted by Vincenzo degli Azani, known as Vincenzo da Pavia (?–1557), which today is at the Regional Gallery of Sicily Palazzo Abatellis (Figure 1), was on the main altar of the oratory (Viscuso 1999). The superior and greater panel depicts the Forty Martyrs immersed naked in a lake in front of urban walls. Above the city, in the sky, the Madonna and Child, surrounded by numerous angels and dominated by the Eternal Father, receive a prayer from a man kneeling on the right. Dressed in his hairshirt, this man can be identified as Saint Ranieri interceding for the Forty, even though his death was more than 700 years after theirs. This chronological paradox evidently brings the Pisan saint to a more relevant position, next to Jesus. The low and large panel below shows the Saint again in a prominent position, that is, in the centre of the scene, walking on the lake surrounded by who should be the forty Roman soldiers on horseback. These images actively interacted with the beholders determining their—conscious or unconscious—interiorization of a model provided by the patrons of the paintings. A consequence of this visual manipulation of hagiographies emerges from a much later manuscript by Lazzaro Di Giovanni (1769–1856), who identified the walls in the painting as the walls of Pisa (Patricolo 1983, p. 160), although there is no element of correspondence with the Tuscan city in the painting.

Figure 1.

Degli Azani, Vincenzo. Madonna col Bambino, San Ranieri e i Quaranta Martiri and I Martiri Pisani. 1551–1553, panel painting, Regional Art Gallery of Sicily Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo. By courtesy of the Regional Art Gallery of Sicily Palazzo Abatellis.

This struggle for political power was also a search for space in the city. The Genoese community progressively took control of the Loggia, especially after the construction of their main church, San Giorgio (1576–1579). Instead, the Pisan oratory was located between two buildings, i.e., the church of Santa Cita and the adjacent oratory of the Rosary, which the Dominicans desired to enlarge. In 1605, after years of negotiations, the confraternity had to abandon its site and move to another neighbourhood. This was an upstream area rich in water sources, called Guilla. Since the twelfth century, it was dedicated to hospitality for pilgrims and the sick under the aegis of the Jerusalem order located in the ancient church of San Giovanni. Between 1608 and 1613, the confriars purchased some old buildings there and, after judicial action with the Jerusalem order about the property of the site, they realised a small single-nave church. For continuity, they brought there with them their paintings, a Crucifix, the bells, and a tombstone.

3. Political Interests, Prejudices, and Art

In the eighteenth century, the great migration from Pisa had long since ended and Pisan lineages, such as Accascina, Alliata (or Agliata), Bonanno, Galletti, Gaetani, and Vanni, had integrated into the urban aristocracy through notable public offices, marriage alliances, and the acquisition of huge estates. Yet, their need for distinction in the city as a group remained. When Guglielmo Borremans was commissioned the inner decoration of the new church in 1725, at the lead of the confraternity there were three noblemen of Pisan descent, don Luigi Gaetani, don Giovanni Alliata, and don Antonino Galletti. Since the heads of households were already engaged in more prestigious urban associations, such as the Compagnia dei Bianchi, it is not surprising that the rectors were members of cadet branches who nevertheless worked for the sake of their lineages. Borremans was already quite famous when he was appointed by them. The apprentice of Pieter van Lint (1609–1690), Borremans had practised in Flanders, Calabria, and Naples before arriving around 1714 in Sicily, where he worked extensively in confraternal oratories, monasteries, and conventual churches that were located throughout the island. The artist was himself a foreigner who underwent a process of successful integration in Sicily, becoming one of the most valued artists by the Sicilian nobility. In the Forty Martyrs, Borremans was entrusted with the task of celebrating the Pisan exiles residing in Palermo through the glory of Pisa.4

Pisa, its people, landscape, buildings, and maritime feats are the protagonists of the cycle. The inside is dominated by four large rectangular scenes on the side walls, a fifth on the counter-façade, and a further four in the two small side chapels. The scenes on the right side, both on the wall and in the chapel, depict episodes from the life of Saint Ranieri. On the left wall, there are crucial moments from the lives of two Pisan saints, Torpes (now lost) and Evelius. The left chapel is dedicated to the Crucifix and frescoed with the Sacrifice of Isaac (Gen 22:1–18) and the Serpents’ Fall upon the Israelites (Num 21:4–9). On the counter-façade there is an episode from Pisan history. The figures are all set in flourishing pastel-toned landscapes. These luminous images are enclosed within the flowing shapes of a frame simulating stucco and separated from each other by painted pilasters.

The trompe-l’oeil architecture marks the whole interior and has its apex on the wall behind the main altar (Figure 2). Despite its partial corruption, this fresco still shows a fake vaulted architecture simulating a transept. High up, some cherubs deliver the symbols of martyrdom (the palm and the crown) to the Forty, who were below, in Vincenzo degli Azani’s painting. Beyond, a fictitious depth develops further in what appears as a domed space. In contrast with the bright aforementioned landscapes of the framed scenes, these spaces remain mysterious and difficult to grasp visually. Given their location behind the altar and its painting, they seem to allude to the heavenly and inscrutable destination of the salvation path of the Forty and of Christians, in general. The optical effect of the quadrature continues on the vaulted ceiling, where painted reliefs on a gilded field are interspersed with portraits in fake medallions, epigraphs, and landscapes in gold frames (Figure 3). Maritime pines recall the Tuscan countryside, while the ships driven by a favourable wind clearly allude to Pisa’s successful seafaring adventures. To remove any doubts about this interpretation, the effigies of many Pisan saints and symbolic buildings of the city, such as the Cathedral and the leaning tower, peek out from the complex system of cornices and volutes. At the top, the fictive architecture virtually opens onto the sky in three points. This allows the sotto-in-su view of angels flying and playing music, while the Virgin is joining the Trinity in heaven.

Figure 2.

Borremans, Guglielmo. The trompe l’oeil architecture behind the altar. 1725, fresco, Church of the Forty Martyrs, Palermo. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

Figure 3.

Borremans, Guglielmo. The vaulted ceiling. 1725, fresco, Church of the Forty Martyrs, Palermo. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

The small church is an all-encompassing space. The effect of luxuriant abundance is increased by the pictorial inclusion of accessory objects and vegetal elements, such as the large vases with plants and the statues of cherubim holding up leafy garlands, both resting on the severe lines of the architectural partition. In the 1798 floor, branches, flowers, and stones superimpose a curvilinear pattern on the orthogonal grid of the tiles. The trompe-l’oeil architecture widens the single nave to accommodate this abundance as a sign of the rich and harmonious dominion of Pisa. The frescoes powerfully affirmed that this dominion extended over water, land, and air, being a city in the graces of God and under the protection of its numerous saints. Nature is not only benevolent towards Pisa but even tamed as demonstrated by the two ferocious animals following Saint Ranieri as if they were domesticated pets (Figure 4). The clarity and luminosity of the entire decoration suggested to the observers (confriars and not) Pisa’s triumph over its opponents as inevitable. The Pisan nobility invested its economic and cultural capitals to perpetuate its own social distinction (Bourdieu 1986; [1945] 1996). The question that remains is at whose expense this flaunted triumph was.

Figure 4.

Borremans, Guglielmo. Saint Ranieri and the Tamed Lions. 1725, fresco, Church of the Forty Martyrs, Palermo. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

The declared attribution to the artist—Guglielmus Borremans Antuerpiensis pinxit—is placed on the counter-façade, under the only framed scene narrating a historical event (Figure 5). Both the location and the inscription suggest the scene as the key to the fresco cycle. Here, a pastel-tone landscape is dominated by the figure of a standing man, elegantly dressed, and placed slightly to the right. At the centre, his outstretched arm leads the observer’s attention towards the left side, where a friar pours water on the head of a bald and moustached man. This man, whose shadowed face is only partially visible, kneels in front of the friar for his baptism. The people on the left, among which a woman with folded hands stands out, seem to be waiting their turn. The friar is making a sign to a brother of his, placed in the background. As if obeying the sign, this second friar fills a container with water from the nearby river. Above the framed image, an inscription recites “Iolus Nobilis Pisanus per Apostolicos Viros Ord.is Minor. Catholicà fideè apud Tartaros strenue amplificavit AN.1282.” Thanks to the inscription, the standing man can be identified as the Pisan aristocrat Pericciolo di Anastasio Bofeti. At the end of the thirteenth century, Bofeti lived at the Mongol court and spread the Catholic faith in the Ilkhanate, i.e., apud Tartaros, thanks to the pro-European politics started by Abaqa Khan (1234–1282). Hence, the baptized man is most probably a Tartar, that is, a Muslim thirteenth-century man from central Asia that Borremans depicted as bald and with a moustache, as well as almost bare-chested and with knee breeches.

Figure 5.

Borremans, Guglielmo. Iolus Nobilis Pisanus. 1725, fresco, Church of the Forty Martyrs, Palermo. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

In so doing, the artist hinted at the oriental and non-European origin of this man, but he also gave the man a specific negative connotation of otherness. This connotation emerges from a comparison with another fresco by Borremans. In the same years, the artist was commissioned by the Naselli family, princes of Aragona, to fresco their villa in Bagheria. In one of his mythological-themed frescos, the multi-eyed shepherd, Argus Panoptes, is depicted asleep, lulled by the music of Hermes. In turn, Hermes is shown in the moment of switching from flute to sword to kill Argus and steal his mare (Figure 6). Apart from the numerous eyes on his head, Argus is portrayed bald and with an abundant moustache. In so doing, Borremans evidently changed Argus’ widespread iconography as a bearded old man, thus further distancing this sinister creature from the classical—and European—model of male beauty embodied by Hermes. The contrast between two different generations of gods becomes an opposition between two different ethnicities: the tanned bald adult and the young white man. The odds of success between the two are rather clear. The primordial deity—equipped only with a stick—is about to succumb to his cunning and better-armed Olympian adversary, who is in the service of the powerful (Zeus).

Figure 6.

Borremans, Guglielmo. Hermes and Argus Panoptes. 1726, fresco, Villa Aragona (today, Villa Cutò), Bagheria. Photograph by the author, by courtesy of the Comune di Bagheria.

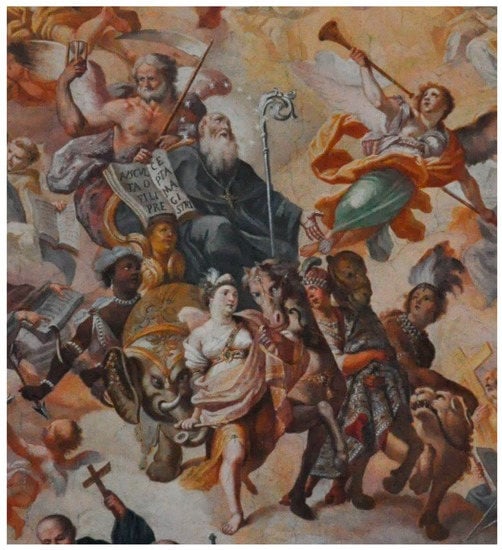

This opposition between winners and losers, with a moustached man playing the latter, recurred in some coeval frescoed vaults. The 1742 vault frescoed by Giovan Battista Piparo (?–1790) in the Monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena, in Catania, is illuminating on the identity of the loser. This Glory of Saint Benedict, which covered the refectory, shows the Saint carrying the precepta magistri to the four corners of the world (Figure 7). His chariot flies in the sky pulled by four animals led by four girls. In the foreground stands a white girl with a horse representing Europe. Behind her, a black girl with an elephant refers to the Black Africans, a reddish-skinned girl holding a camel to the Arabs, and a tanned girl with the feathered headdress and a lion to the peoples of the Americas. The lower scene on the left shows the preaching of the Benedictines to Americans and the baptism of Black Africans (Figure 8). However, on the right two moustached, half-naked, reddish-skinned men are hurled down from the clouds by what appears to be a spear (or a lightning bolt) brandished by a pope. In their hands, two books indicate the different creed that prevents them from accepting the Christian God. This image was visible to the monks during their daily meals, producing in them prejudicial attitudes and behaviours. Despite a persistent multiculturalism at the base of society, the attitude of Sicilian religious institutions was ambiguous towards Muslims. Captives taken because of conquests or corsair activity, if remaining in Sicily, were considered difficult to convert. This meant that they were left with the possibility of retaining their faith and having a certain ease of movement, but they were still considered treacherous people and seen with suspicion (De Lucia 2020, p. 147). Their exclusion from the path of salvation, as shown by the fresco, was interiorised by the monks, thus constructing in them a perception of the social order (Bourdieu [1945] 1996).

Figure 7.

Piparo, Giovan Battista. The Glory of Saint Benedict (detail). 1742, fresco, Monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena, Catania. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

Figure 8.

Piparo, Giovan Battista. The Glory of Saint Benedict (detail). 1742, fresco, Monastery of San Nicolò l’Arena, Catania. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

Clear indications such as the one emerging from the Benedictine fresco of Catania, however, were quite rare. More frequently, only ambiguous stereotyped traits referred to Muslims. A case in point was the lost Triumph of the head of the Alliata household, which was painted in 1757 by Gaspare Serenario (1707–1759) in Palazzo Villafranca in Palermo.5

A black-and-white photograph (Figure 9) shows us that this fresco depicted a young prince surrounded by Virtues while two angels drove a naked man and a clothed woman away from him. Later interpreted as demons (Marsalone 1942), the two appeared as a real couple falling, in an unseemly pose, into the abyss. As Borremans left the wide moustache of the Tartar still visible despite his face being half-hidden, the falling man painted by Serenario sports a large moustache, although his face is in shadow. In the Forty Martyrs’ church, another example of this vague reference to evil can be found in the Beheading of Saint Evelius (Figure 10). This Pisan martyr was killed by the Romans, who are represented here by the centurion standing on the left. However, the centurion just watches the scene from behind a rock, holding nothing but a stick. The one who is about to unsheathe the sword against a (Pisan) Christian Saint is a moustached man, bare-chested, with slightly reddish skin, and wearing knee breeches and a high red band around his waist. The portrait of Saint Evelius’ executioner seems too close to Muslim iconography not to fill the viewer with doubt as to who is the villain of the story.

Figure 9.

Serenario, Gaspare. The Ascent of the Prince, 1757, (lost) fresco, Palazzo Villafranca, Palermo. Photograph kindly provided by Francesco Brugnò.

Figure 10.

Borremans, Guglielmo. The Beheading of Saint Evelius. 1725, fresco, Church of the Forty Martyrs, Palermo. Photograph by Gaetano Scaduti.

In the counter-façade, however, a more evident religious reference stands out. At the bottom centre, a turban is placed on the ground, clearly visible but turned upside down. Its closeness to the baptised Mongol alludes to its being his, while its position suggests that it was not placed there carefully but thrown with little regard. Since the sixteenth century, viceregal prescriptions obliged Muslims in Sicily to wear the alla turca turban, under penalty of imprisonment (Pomara 2017, p. 134). More than an object freely chosen, the turban was a mark imposed by the authorities to immediately identify the Muslims circulating in the city and to exercise a form of social control over them, whatever their actual origin. The purpose was not to create confusion between the faithful and infidels and endanger the city’s order and its underpinning social hierarchies. However, for the Inquisition, this was not enough to eliminate the threat, since the display of the Muslim faith, determined by the outdoor use of the turban, could attract Christians to Islam (Sorce 2021, p. 173).

Painting a turban, Borremans recycled a pre-existing iconography referring to the Muslim faith, widespread in many cities, including Venice (Čapeta Rakić 2017), Genoa (Stagno 2017), and Rome (Capriotti 2017), but also visible in many monuments in Palermo, as in the nearby Porta Nuova (1569–1584, modified in 1669 and 1686). On the outer façade of this main urban gate, four telamons wear turbans and three of them have big moustaches. In the local literature they have been identified, from 1590 onwards, as the Turks defeated and enslaved by Charles V in the battle of Tunis (1535). From Valerio Rosso (1572–1602) to Antonino Mongitore (1663–1743) and beyond, Sicilian writers supported the correspondence between these iconographic traits and the idea of a single enemy, the infidel. As Cristelle Baskin argues, this interpretation simplified the facts, omitting the alliance between Charles V and the Hafsid king of Tunis and denying other possible identification of the telamons, such as with the North Africans circulating in Palermo (Baskins 2019).

The enduring confusion between Ottoman Turks, the numerous Berber and Arab tribes of North Africa and the peoples of the Near East was already largely established in Europe, in association with the use of vague terms, such as Moors and Saracens, to define them all (Sorce 2021, p. 174). The result of this deliberate attempt to confuse was to identify different peoples with a single and indistinct enemy, but in Palermo the vagueness of the enemy’s image stemmed also from a matter of prudence. It is plausible to think that the example of Bofeti was suggested to Borremans by his patrons, who were well established in Palermo society. Understandably, they did not want to recall the battles against the Arabs of Sicily, which could imply an opposition between Pisans and Sicilians. Their visual manipulation of history began with the choice of a geographically distant event and continued with some deliberate omissions. As the chroniclers who narrated Charles V’s conquest of Tunis without mentioning the support that he had from the Hafsid king, Borremans omitted Bofeti’s collaboration with the Mongol khans. Beyond his specific duties, it now seems clear that the Pisan nobleman worked in their service (Ceccarelli Lemut 2008, p. 18). Yet, to make the good/evil contrast more effective, the artist transformed a negotiating partnership into a message of binary opposition, in which the Pisan nobleman appears to exceed in importance the people hosting him. However, it should be added that, although the vagueness of the traits used by Borremans allowed a circumvention of an uncomfortable past, the same vagueness could allude to many, that is, not only the Berber pirates and the Turkish soldiers, but also the Muslims circulating in the city, thus extending to them the same negative connotation of otherness.

The attitude suggested by the artwork towards converts was not much different either. Unequivocally, the baptized Tartar depicted by Borremans has thrown his turban to the ground with little care, thus denying his previous belief. On the right a child is bringing him another hat of a different shape, that is, the Christian alternative. Theoretically, after the conversion, his journey of salvation, from the counter-façade to the altar and the mysteries of the doctrine shown on the other side of the nave, can begin. However, a distance towards the convert is still recommended. Both Evelius (during his decapitation) and Ranieri (during his baptism) are kneeling like the Tartar, but, unlike him, they face the observers. This produced a different relationship between the depicted characters and the confriars looking at them. The confriars were called to walk with their saints along their sanctification path. Conversely, a direct relationship between the convert and the viewers was hampered by his turning his back on them. Although the conversion was the necessary condition to be accepted, the convert was alone along his path. No matter how sincere their conversion could appear, culture suggested that the climate of distrust around Muslims should not end when their turban was removed. As treacherous people, they might be able to disguise themselves and lie. Another fresco by Serenario very eloquently gives us an idea of this prejudice (Figure 11). In an anteroom of Palazzo Scordia, the shining ascent of two young and blonde divinities is painted on the vault. On the opposite side of the ascent, two angels repel some people out of the ceiling (a cardboard foot even protrudes beyond the edge of the stucco frame!), using incandescent darts and liquids. In the plunging couple in the foreground, the man has all the characteristics already mentioned (reddish complexion, partially covered face, and moustache). The woman is seen from behind and therefore her face is completely invisible, but she is evidently holding a mask in her right hand. The presence of this item suggested to observers that the wicked could disguise themselves. Consequently, it was licit to suspect that their conversion was insincere.

Figure 11.

Serenario, Gaspare. Vaulted ceiling of an anteroom (detail), c. 1750, fresco and stucco, Palazzo Scordia (today, Palazzo Mazzarino), Palermo. Photograph by Rossella Campagna, by courtesy of the Berlingeri family.

These implicit references awakened never-dormant fears, which can be comprehensible in a period when the gruesome and violent exploits of piracy and slavery were not yet concluded. However, these fears were kept alive and fuelled by culture. Don Francesco Maria Gaetani, marquess of Villabianca, still expressed a binary opposition between the Christian and the Muslim fronts on the Mediterranean Sea, in a manuscript of the end of the eighteenth century.

“Merchant vessels, however, when not accompanied, must not march lightly, I mean equipped with few cannons and little ammunition for war, but they must carry armaments in some way so as to be able to stand against the corsairs and sea-owners, who are the plagues of commerce; if there were no such sea robbers, it [the commerce] would yield three times the ordinary which it usually brings with the feared dangers on pirates and assassins in the loss of life and goods, and of the loss of freedom with slavery which, at the same time, one can suffer.”6

Two considerations scale down Villabianca’s words. First, the Sicilian maritime commerce was negatively affected not only by piracy, but also by the competition from Italian navies. This was meaningfully omitted by Villabianca whose family had a Pisan origin. Secondly, there was no stable line between sea robbers and honest traders. In an economy where private interest weighed as much as that of nation states, piracy and slavery were reciprocally considered an investment (Zappia 2021, p. 261). Not only was the corsair war a source of income for Christians too, but the Muslim enemies were ideal trading partners for them. Rather, after the main trade routes had shifted to the Atlantic Ocean, the war contractors had every vested interest in keeping military forces engaged in the area (Carpentier 2021, pp. 241-242). Reiterating the usual binary contrast served this purpose.

In this contrast, however, it was necessary to keep the city of Palermo and the entire island on the side of Christianity. Any trick or mystification could contribute to this effect. A consideration in this sense emerges in about the year 1282 so evidently written in the fresco of the counter-façade. To date, there is very little information on Bofeti’s activity at the Mongol court, none of which is before 1284 (Block Friedman and Figg 2000, p. 67). It is possible that in the eighteenth century there was more data on him. However, the year 1282 saw the end of the Ilkhanate of Abaqa Khan and the start of the rapprochement with Muslim countries by his brother Tekuder (1246–1284). Therefore, even if Bofeti already had an influential position at the Mongol court in 1282, it is unlikely that he could openly contribute to the conversion of Muslims in that year. Instead, his active involvement in favour of the Christian faith could have been easier after 1284, when Abaqa’s son, Arghun Khan (1258–1291), led a successful revolt against Tekuder and took power, returning to pro-Christian politics (Prazniak 2019, p. 61). Whether the mistake was intentional or not, the date of 1282 certainly resonated in the collective memory of the citizens of Palermo as a moment of successful revenge, because of the Sicilian Vespers. This stratagem could bring the—chronologically and geographically distant—episode of Pisan history closer to the observers and perhaps even prompt them to identify themselves in Bofeti’s role as defender of the Christian faith.

In this coincidence of dates, it is possible to read a more subtle political move. When Borremans was commissioned to fresco the church walls, Sicily had passed from the long Spanish rule (1412–1713) into the hands of the Savoy House (1713–1720), and from the Piedmonts to the Habsburgs of Austria (1720–1734). The reference to the Vespers revolt, which had led to the start of Spanish rule in Sicily, could not go unnoticed in a period when the Austrian authorities had jeopardized the centuries-long privileges of Palermo nobility. The failed military attack of 1718 had proved that the Spanish ambitions on Sicily had not subsided. Rather, they were fuelled by the manoeuvres of Elisabeth Farnese (1692–1766), the Spanish queen with Italian origins who had married Philip V on 16 September 1714 and whose son Charles would take Naples in 1734. For its part, the aristocracy continued to have pro-Spanish attitudes. In 1735, while Syracuse put up a strenuous resistance to the Spanish army, the nobility of Palermo would hurry to open city gates to the new bourbon king (Mongitore 1871, pp. 270–71). Amongst the first aristocrats paying King Charles their respects, there were heads of the households with Pisan origins, such as don Domenico Alliata prince of Villafranca and don Francesco Bonanno prince of Cattolica, who were, respectively, Governor of Messina and Praetor of Palermo. It is not easy to grasp how ready they were to join the new regime in 1725, but the “heavy fiscal hand” of the Habsburgs crown had probably already pushed many of them to embrace again the Spanish political project (Storrs 2016, p. 189). An episode seems to confirm it. In 1733 a second relic of Saint Ranieri was sent from Pisa to Palermo, this time destined for the renovated church of the Forty Martyrs (Sainati 1898, pp. 40–41). It is possible to read in this act the renewal of the bond between the two cities, but perhaps also, in the memory of the first relic, the regeneration of the political alliance between Pisa and the Spanish crown.

By distorting history, images promoted an anti-Islamic attitude that could bring the city closer to the European—and Spanish, in particular—conflictual approach to the Muslim threat. However, the time was almost ripe for a turnaround, which would make Borremans’ work appear antiquated. In 1788 Father Fedele from San Biagio (1717–1801) wrote about the inventiveness and the consequent lack of truthfulness of Borremans’ painting. The Capuchin lamented the incorrect proportions of his figures, the bizarre spirit of his compositions, and the pretentious colours of his palette (Tirrito 1788, p. 243). Consciously or unconsciously, Father Fedele’s criticism conveyed more than purely aesthetic issues. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, Sicilian collectors and historians were rediscovering their Arab past and beginning a new ideological manipulation of it (Armando 2017, pp. 8–9, 17). While the Mediterranean gradually became a less dangerous sea, that component of Sicilian society, which culture had long tried to declare as something other than itself, was now being recovered to create a new identity and to promote a new political project.

4. Conclusions

This paper has argued for the complicity of culture in spreading discriminatory messages in eighteenth-century Palermo. To do this, it has investigated the church of the Forty Martyrs and its fresco cycle by Guglielmo Borremans, where political interests, prejudices, and art intersected. By using historical events and hagiographic episodes rather ambiguously, the frescoes produced a persistent binary opposition between Christians and Muslims. In the face of the everyday multiculturalism of the city, this work of art fuelled fears and suspicions towards Muslims to support the political interests of the nobility of Pisan descent. On the one hand, the numerous references to Pisa’s success, floridness, and sanctity suggested the ineluctability of its supremacy. On the other hand, the insinuating message about the malice of its main enemy indicated the need for this supremacy to defend Christianity in the Mediterranean.

Through the vaunted grandeur of their original city, the Pisan lineages in Palermo were indirectly celebrated. On the international political front, the praised role of Pisa against Islam placed these aristocratic families in line with the politics of European courts, and especially with the centuries-old project of the “Most Catholic King of Spain,” whose renewed ambitions towards Sicily were quite well known by then. On the domestic front, the frescoes confirmed the ties of the aristocrats of Pisan descent with the Latin-Christian component of the urban population, which had by then surpassed the Muslims in number and power. To do this, the identity of the enemy underwent a process of deceptive coverage. The vague image of the infidel, resulting from this process, was in line with the confused identification of Muslims that was implemented throughout Europe. However, another reason for this camouflage emerges from the analysis, that is, the past conflicting relationship between Palermo and Pisa, which was not convenient to rehash. Paradoxically, though, as art worked to connect Palermo to the continent, new cultural impulses emerged in the city to recover the relationship with its Arab past.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This article greatly benefited from the sharing of ideas that took place at the Sicilia Schiava conference on 18 November 2022, in Palermo. Among the many who engaged in its organization with me, I would like to thank Lori De Lucia for her support and contribution. I thank Manuel Rossi, Head of the heritage and archives of the Opera Primaziale in Pisa for his courtesy in providing information and my dear friend Helena Moore for her careful proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A case in point is that of the different behaviours demonstrated by the viceroy and the Inquisition towards the Moriscos (Pomara 2017, pp. 127–28). |

| 2 | A complete bibliography on Guglielmo Borremans can be found in (Di Bella 2012). To my knowledge, only a couple of more recent works are to be added to Di Bella’s list, i.e., (Benintende 2013) and (Gino Li Chiavi 2018). |

| 3 | As to the Norman period, this discrepancy emerges from the comparison between the continuity of poor art forms, such as ceramics, and the reinvention of monumental architecture around 1130, made with the extensive use of external contributions (Johns 2015) to show the universality of royal power (Bongianino 2017). |

| 4 | I leave aside the vexed question of the possible collaboration of local architects and assistants opened by a comment by Gioacchino Di Marzo (Di Marzo 1912), which, to my knowledge, has never been documented. |

| 5 | Born in Palermo, Gaspare Serenario trained with local painters. However, it seems that he collaborated with Borremans in the 1720s (Brugnò 1992, pp. 458–59). The works mentioned here were created by Serenario after his long stay in Rome (1731–1745). |

| 6 | “I bastimenti però mercantili, quando non sono di compagnia non devon marciar leggeri, voglio dire provvisti di pochi cannoni e di poche munizioni di guerra, ma bisognano portare armamento in qualche maniera da poter stare a fronte de’ corsali e degli armatori di mare, che sono le pesti del commercio, se non vi fossero tali ladri di mare, frutterebbe il triplice dell’ordinario che suol portare coi pericoli temuti sulli pirati ed assassini nella perdita di vita e della robba, e della perdita di libertà colla schiavitù che allo stesso si può patire” (Gaetani 1989, p. 67). |

References

- Armando, Silvia. 2017. The Role and Perception of Islamic Art and History in the Construction of a Shared Identity in Sicily (ca. 1780–1900). Memoirs of the American Academy 62: 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Emma. 2017. Introduction. In Art, Commerce and Colonialism 1600–1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baskins, Cristelle. 2019. The Play of Mistaken Identities at the Porta Nuova of Palermo. In Jews and Muslims Made Visible in Christian Iberia and Beyond, 14th to 18th Centuries. Edited by Borja Franco Llopis and Antonio Urquizar-Herrera. Leiden: Brill, pp. 331–54. [Google Scholar]

- Benintende, Claudio. 2013. Guglielmo Borremans nella chiesa di San Giuseppe a Leonforte. Leonforte: Euno. [Google Scholar]

- Bethencourt, Francisco. 2013. Racism. From the Crusades to the Twentieth Century. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Block Friedman, John, and Kristen Mossler Figg. 2000. Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages. An Encyclopedia. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaffini, Giuseppe. 1983a. La Sicilia e i Barbareschi. Incursioni Corsare e Riscatto Degli Schiavi (1570–1606). Palermo: Ila Palma. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaffini, Giuseppe. 1983b. La Sicilia e il Mercato Degli Schiavi alla Fine del ‘500. Palermo: Ila Palma. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaffini, Giuseppe. 1997. Un Mare di Paura. Il Mediterraneo in età Moderna. Caltanissetta-Roma: Salvatore Sciascia Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaffini, Giuseppe. 2003. Cattivi e redentori nel Mediterraneo tra il XVI e XVII Secolo. Palermo: Ila Palma. [Google Scholar]

- Bongianino, Umberto. 2017. The King, His Chapel, His Church. Boundaries and Hybridity in the Religious Visual Culture of the Norman Kingdom. Journal of Transcultural Medieval Studies 4: 3–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, Salvatore. 1989. Siciliani nel Maghreb. Trapani: Arti Grafiche Corrao s.n.c. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, Salvatore. 1993. Corsari nel Mediterraneo: Cristiani e Musulmani fra Guerra, Schiavitù e Commercio. Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, Salvatore. 2005. Lumi e corsari. Europa e Maghreb nel Settecento. Perugia: Morlacchi Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John Richardson. Westport: Greenwood, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste [1945]. Cambridge and Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. First published 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Brugnò, Francesco. 1983. La decorazione pittorica della chiesa dei Santi Quaranta Martiri e di San Rainieri dei nobili pisani alla Guilla: Note ed ipotesi. In Immagine di Pisa a Palermo. Atti del Convegno di Studi sulla Pisanità a Palermo e in Sicilia nel VII Centenario del Vespro. Edited by Istituto Storico Siciliano. Palermo: Istituto Storico Siciliano, pp. 555–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brugnò, Francesco. 1992. Contributi a Gaspare Serenario. In Le arti in Sicilia nel Settecento. Studi in Memoria di Maria Accascina. Edited by Maria Giuffrè and Manfredi La Motta. Palermo: Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei beni Culturali e Ambientali e Della Pubblica Istruzione, pp. 457–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cancila, Rossella. 2007. Il Mediterraneo assediato. In Mediterraneo in Armi (secc. XV–XVIII). Edited by Rossella Cancila. Palermo: Associazione Mediterranea, vol. 1, pp. 7–66. [Google Scholar]

- Čapeta Rakić, Ivana. 2017. Distinctive features attributed to an infidel. The political propaganda, religious enemies and the iconography of visual narratives in the Renaissance Venice. Il Capitale culturale 6: 117–43. [Google Scholar]

- Capriotti, Giuseppe. 2017. Becoming paradigm: The image of the Turks in the construction of Pius V’s sanctity. Il Capitale Culturale 6: 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier, Bastien. 2021. The Necessary Enemy. In Lepanto and Beyond. Images of Religious Alterity from Genoa and the Christian Mediterrenean. Edited by Laura Stagno and Borja Franco Llopis. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 241–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli Lemut, Maria Luisa. 2008. Pisa nel Mediterraneo durante il XIII secolo. In La Storia di Pisa Nelle Celebrazioni del “6 Agosto” (1959–2008). Edited by Alberto Zampieri. Pisa: ETS, pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, Eric. 1986. Southern Italy in the Age of the Spanish Viceroys: Some Recent Titles. The Journal of Modern History 58: 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Michael. 2013. Toward an Art History of Spanish Italy. I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 16: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, Lori. 2020. Sicily and the Two Seas: The Cross Currents of Race and Slavery in Early Modern Palermo. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Di Bella, Nicoletta. 2012. Guglielmo Borremans di Anversa pittore fiammingo in Sicilia nel secolo XVIII (1912) di Gioacchino Di Marzo. Aggiornamento critico-bibliografico. Un progetto multimediale. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo, Gioacchino. 1912. Guglielmo Borremans di Anversa. Pittore Fiammingo in Sicilia nel secolo XVIII (1715–1744). Palermo: Stabilimento Tipografico Virzì. [Google Scholar]

- Fiume, Giovanna. 2009. Schiavitù Mediterranee: Corsari, Rinnegati e Santi di età Moderna. Milano: Bruno Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetani, Francesco Maria. 1989. L’arte Nautica e i Vantaggi della Navigazione. Edited by Orazio Cancila. Palermo: Edizioni Giada. [Google Scholar]

- Gino Li Chiavi, Claudio. 2018. L’apparato decorativo della chiesa di San Vincenzo Ferreri a Nicosia. Nuove acquisizioni documentarie. A.S.Si.Ce.M. 8–9: 145–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guttilla, Mariny. 1983. Guglielmo Borremans e gli affreschi nella chiesa dei Santi Quaranta Martiri e di San Rainieri dei nobili pisani alla Guilla: Analisi stilistica ed iconografica. In Immagine di Pisa a Palermo. Atti del Convegno di Studi sulla Pisanità a Palermo e in Sicilia nel VII Centenario del Vespro. Edited by Istituto Storico Siciliano. Palermo: Istituto Storico Siciliano, pp. 493–54. [Google Scholar]

- Howie, Ana. 2022. Materialising Racialised Blacknesses in Early Modern Italy. Paper presented at the Race and the Early Modern Conference, London, UK, May 24. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Jeremy. 2015. Muslim Artists and Christian Models in the Painted Ceilings of the Cappella Palatina. In Romanesque and the Mediterranean Romanesque and the Mediterranean. Patterns of Exchange Across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds c.1000-c.1250. Edited by Rosa Bacile. London: Routledge, pp. 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Jeremy. 2018. L’invenzione dell’arte islamica nella Sicilia normanna. Paper presented at the Seminar at the Humanistic Deptment of the University of Catania, Catania, Italy, May 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mallette, Karla. 2005. Orientalism and the Nineteenth-Century Nationalist: Michele Amari, Ernest Renan, and 1848. The Romanic Review 92: 233–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, Giovanni. 1972. La Schiavitù nella Società Siciliana dell’età Moderna. Caltanissetta and Rome: Edizioni Salvatore Sciascia. [Google Scholar]

- Marsalone, Nunzio. 1942. Il Cavaliere Gaspare Serenario. Pittore Palermitano del Settecento. Palermo: IRES. [Google Scholar]

- Mongitore, Antonino. 1871. Diario Palermitano 1720–1736. In Diari della città di Palermo dal secolo 16°al 19° Pubblicati sui Manoscritti della Biblioteca Comunale. Edited by Gioacchino Di Marzo Ferro. Palermo: L. Pedone Laurel, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Patricolo, Roberto. 1983. La Confraternita e la Chiesa nazionale pisana da Porta San Giorgio alla Guilla nella dinamica socioeconomica dell’emigrazione a Palermo. In Immagine di Pisa a Palermo. Atti del Convegno di Studi sulla Pisanità a Palermo e in Sicilia nel VII Centenario del Vespro. Edited by Istituto Storico Siciliano. Palermo: Istituto Storico Siciliano, pp. 33–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pomara, Bruno Saverino. 2017. Rifugiati. I Moriscos e l’Italia. Firenze: Firenze University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prazniak, Roxann. 2019. Sudden Appearances. The Mongol Turn in Commerce, Belief, and Art. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1995. Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient [1978]. London: Penguin Book. First published 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sainati, Giuseppe. 1898. Diario Sacro Pisano. Turin: Tipografia Salesiana. [Google Scholar]

- Scalia, Giuseppe. 1983. L’impresa pisana del 1064 contro Palermo nella testimonianza del Duomo di Pisa. In Immagine di Pisa a Palermo. Atti del Convegno di Studi sulla Pisanità a Palermo e in Sicilia nel VII Centenario del Vespro. Edited by Istituto Storico Siciliano. Palermo: Istituto Storico Siciliano, pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Benjamin. 2015. Inventing Exoticism. Geography, Globalism, and Europe’s Early Modern World. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorce, Francesco. 2021. The Turks at the Lord’s Table. Servants, Observers, Guests. In A Mediterranean Other. Images of Turks in Southern Europe and Beyond (15th–18th Centuries). Edited by Borja Franco Llopis and Laura Stagno. Genova: Genova University Press, pp. 170–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stagno, Laura. 2017. Triumphing over the Enemy. References to the Turks as part of Andrea, Giannettino and Giovanni Andrea Doria’s artistic patronage and public image. Il Capitale Culturale 6: 145–88. [Google Scholar]

- Storrs, Christopher. 2016. The Spanish Resurgence 1713–1748. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tirrito, Fedele. 1788. Dialoghi Familiari sopra la pittura difesa, ed esaltata dal p. Fedele da S. Biagio pittore cappuccino col. sig. avvocato d. Pio Onorato palermitano alla presenza de’ suoi allievi nella bell’Arte…. Palermo: Per don Antonio Valenza impressore camerale. [Google Scholar]

- Trivellato, Francesca. 2010. Renaissance Italy and the Muslim Mediterranean in Recent Historical Work. The Journal of Modern History 82: 127–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscuso, Teresa. 1999. Vincenzo degli Azani da Pavia e la Cultura Figurativa in Sicilia nell’Età di Carlo V. Siracusa: Ediprint. [Google Scholar]

- Zappia, Andrea. 2021. In the Sign of Reciprocity. Muslim Slaves in Genoa and Genoese Slaves in Maghreb. In Lepanto and Beyond. Images of Religious Alterity from Genoa and the Christian Mediterranean. Edited by Laura Stagno and Borja Franco Llopis. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 241–53. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).