A Paratext Perspective on the Translation of the Daodejing: An Example from the German Translation of Richard Wilhelm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Paratexts in Wilhelm’s Translation

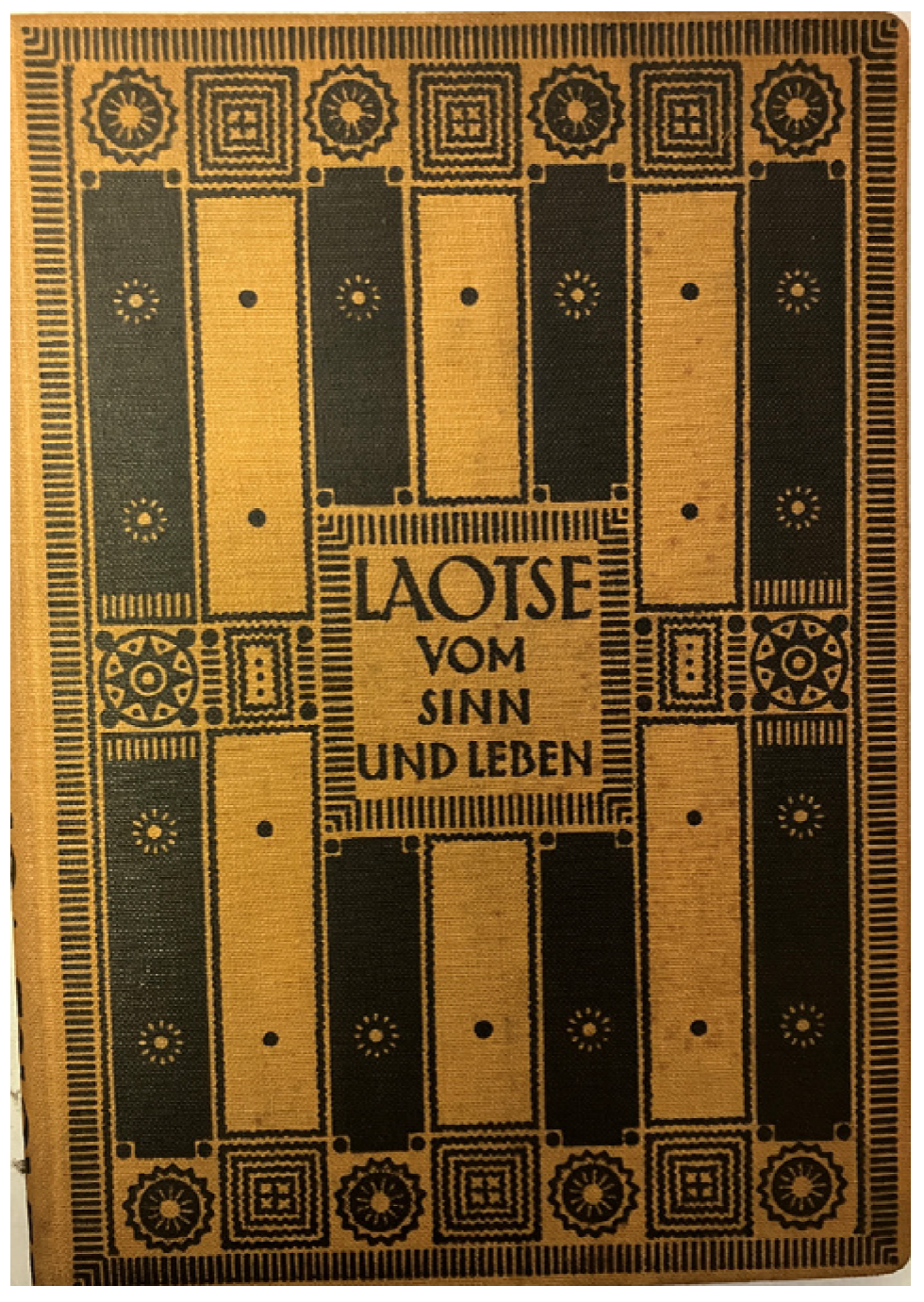

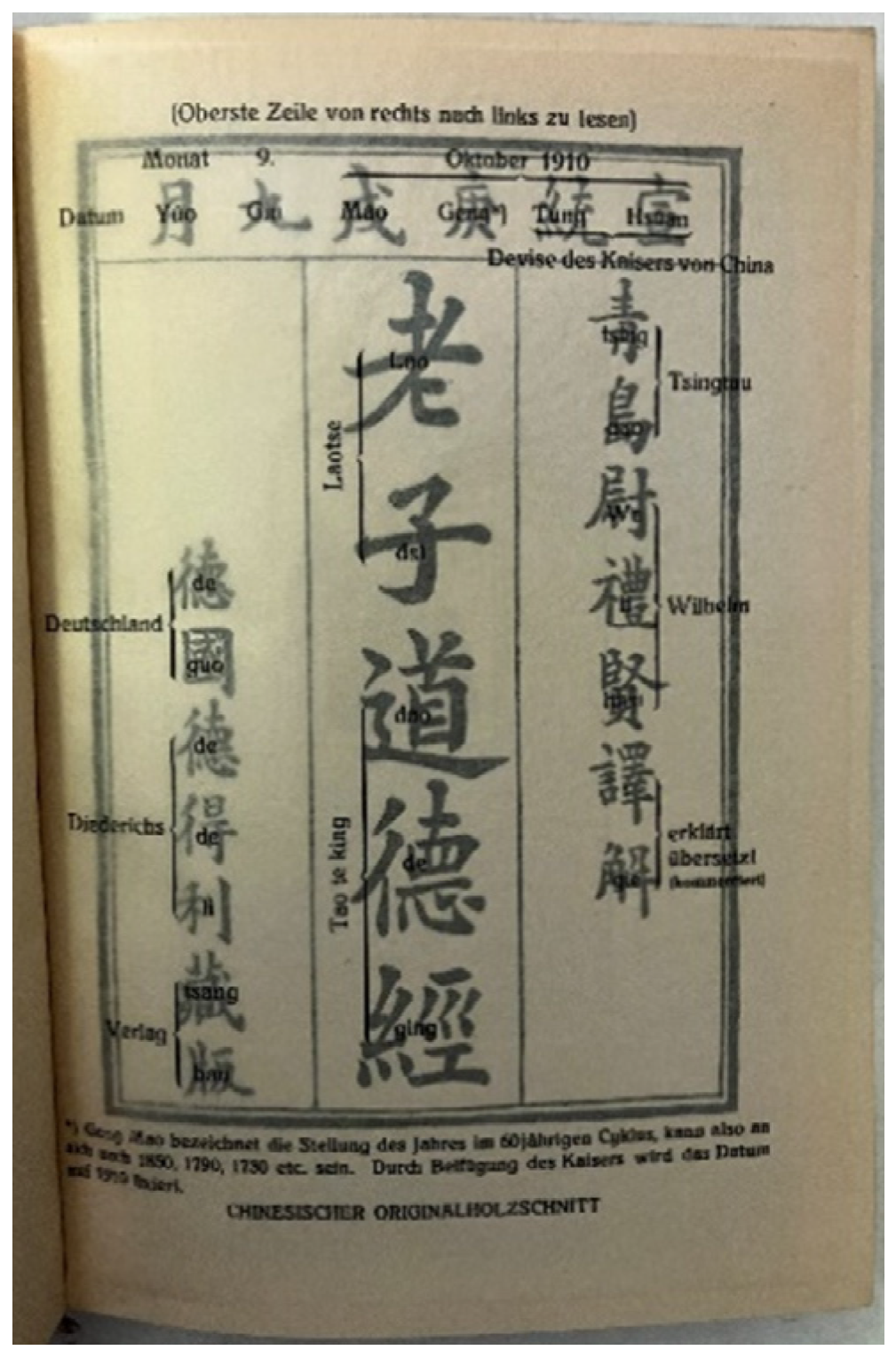

2.1. Cover, Title Pages, and Illustrations: Identifying Book Categories and Attracting Readers

2.2. Foreword and Introduction: Background Supplement and Text Overview

2.3. Footnotes and Post-Textual Interpretation: Knowledge Integration and Meaning Clarification

In sacrificial rites, dogs were made of straw, which were festively decorated during the sacrifice, but once they had served their purpose, were carelessly discarded.

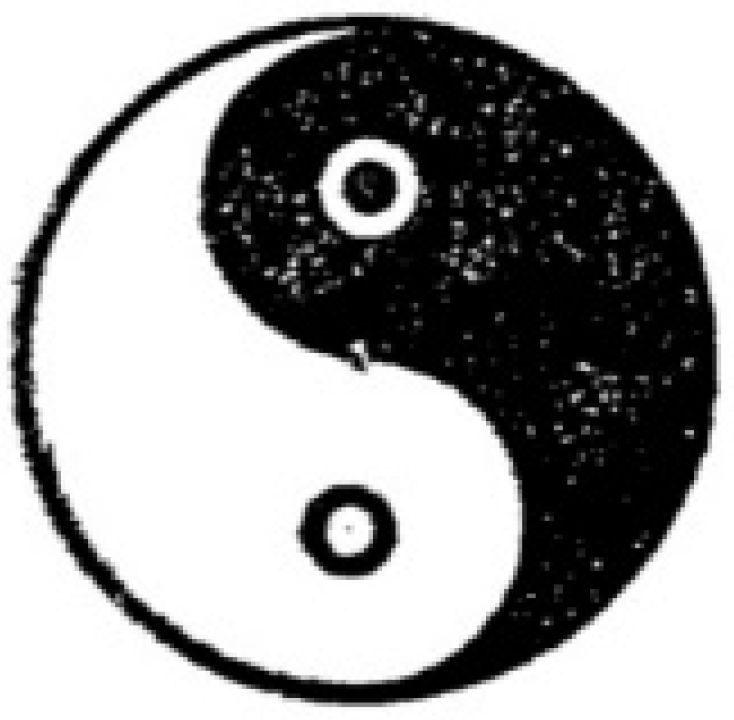

To elucidate this unity, Laozi refers to the symbolic figure of taiji (often translated as “Primordial Beginning”), which has significant resonance in ancient Chinese thought and has been particularly used in endless variations and adaptations, representing the intertwining of the positive and negative (Figure 4).

Wherein the white half of the circle, containing within itself a black circle with a white dot, signifies the positive, masculine, and luminous principle. In contrast, the correspondingly designed black half symbolizes the negative, feminine, and dark principle. This symbolic figure is likely alluding to the profound mystery of the unity between the existent and the non-existent (=μη ὀν, as consistently referred to by Laozi whenever discussing the “non-existent”). An even deeper mystery within this enigma would be the so-called wuji (translated as “Non-Beginning”, even beyond taiji), representing a chaotic state before any distinctions are made, typically represented by a simple circle (Figure 5). It can be described as the pure possibility of existence, akin to chaos.

The Unity refers to wuji, the Duality refers to taiji—with its division into yang 陽 and yin 陰,4 and the Ternarity signifies “the infinite vitality”, namely, the spirit, is, so to speak, the medium of the unification of the two dual forces.

The Duality encompasses the opposites of light and darkness, of male and female, of positive and negative, and the Ternarity emerging from taiji represents the process wherein opposing entities combine, counteracting each other, subsequently engendering myriad entities.

2.4. Appendix: Academic Supplements and Book Series Promotion

3. The Constructive Role of Paratexts in Wilhelm’s Translation

3.1. Constructing a Philosophical Framework of Daoism

Every principle taken from external experience will be refuted and become obsolete over time, because as human progress advances, so does the understanding of the world. On the contrary, what is recognized from central experience (from the inner light, as expressed by the mystics), remains irrefutable, provided it was otherwise purely and correctly perceived.

3.2. Comparing the Thought of Confucianism and Daoism

The sentence: “Respond to resentment with LIFE (LEBEN)” usually translated as: “Repay wrong with kindness”, plays a certain role in the discussions of the time. Laozi justifies it in Chapter 49 by stating that our actions necessarily arise from our nature, thus we can only be good. He thus surpasses the concept of “reciprocity”, which occupies such an important place in post-Confucian systems. Confucius had doubts about this concept for reasons of state justice (see his statement on the question in the Analects, book XIV. 36, page 163), although he has acknowledged the principle for individual morality (see Liji).

3.3. Broadening the Dialogue between Chinese Philosophical Thought and Western Intellectual Traditions

The three names of the SENSE (SINN): “The Equal” “The Subtle” “The Minute” signify its supernatural qualities. Attempts to read the Hebrew name of God from the Chinese sounds I, Hi, We may now be at an end. (Victor von Strauss, as is well known, still believed in this; see his translation.)

The fact that the view of SENSE (the deity) outlined here has some parallels in Israelite teachings is not to be denied; see especially the passages in Chapter 33 of the Exodus and Chapter 19 of the Book of Kings for our section. However, such agreements are understandable enough even without direct contact. This view of the deity simply represents a certain stage of development of human consciousness in its understanding of the Divine. Moreover, the fundamental difference between Laozi’s impersonal pantheistic conception and the sharply defined historical personality of the Israelite God must not be overlooked.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Laozegetics” emerges from the Chinese study of Laoxue 老學, which means “the study of, doctrine of, school of, knowledge of, or field of study of Laozi the person or Laozi the text” (Tadd 2022b, p. 2). Laozegetics shifts the focus from seeking the original text and its original meaning to appreciating the hermeneutical and historical value of the various translations and interpretations on the Daodejing, including those in different cultures and languages. |

| 2 | Diederichs publisher was founded by Eugen Diederichs (1867–1930) in 1897. Since then, Diederichs has always led discussions on important social issues in Germany, dedicating himself to introducing the finest cultures of various nations into the German-speaking world. He can be considered one of the most significant figures in the German cultural sphere in the first half of the 20th century (Diederichs 2014, p. 8). In addition to the “Chinese Religion and Philosophy” series, Wilhelm also published a large number of academic monographs at this publishing house. |

| 3 | Before the appearance of Wilhelm’s translation, there were eight full German translations of the Daodejing (Tadd 2022a, pp. 145–146, 156): 1. Laò-Tsè‘s Taò Tě Kīng (Victor von Strauss 1870); 2. Lao-Tse Táo-Tě-King, der Weg zur Tugend (Reinhold von Plaenckner, 1870); 3. Taòtekking von Laòtsee (Friedrich Wilhelm Noak, 1888); 4. Theosophie in China. Betrachtungen über das Tao-Teh-King (Franz Hartmann, 1897); 5. Lao-tsï und seine Lehre (Rudolf Dvorák, 1903); 6. Die Bahn und der rechte Weg des Lao-Tse (Alexander Ular, 1903); 7. Des Morgenlandes grösste Weisheit. Laotse Tao Te King (Joseph Kohler, 1908); 8. Lao-tszes Buch vom höchsten Wesen und vom höchsten Gut (Julius Grill, 1910). |

| 4 | Yang 陽 and yin 陰 are two significant concepts in Chinese philosophy, representing two fundamental forces in nature that are both opposing and interdependent. Yang symbolizes traits such as positivity, masculinity, daylight, and strength, while yin represents passivity, femininity, nighttime, and gentleness. These two principles are considered as the foundation for the existence and development of all things. Wilhelm’s interpretation here referred to the content of Chapter 5 of Yizhuan Xici 易傳·系辭 (Commentary on the Attached Verbalizations of the Yijing), which states, “The interaction of yin and yang is called Dao”. |

References

- Amarantidou, Dimitra. 2023. Translative Trends in Three Modern Greek Renderings of the Daodejing. Religions 14: 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debon, Günther. 1961. Lao-Tse Tao-Te-King. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam. [Google Scholar]

- Detering, Heinrich. 2008. Bertolt Brecht und Laotse. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs, Eugen. 1936. Eugen Diederichs Leben und Werk: Ausgewählte Briefe und Aufzeichnungen. Jena: E. Diederichs Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs, Ulf. 2014. Eugen Diederichs und sein Verlag Bibliographie und Buchgeschichte 1896 bis 1931. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Qiang 耿强. 2016. 翻译中的副文本及研究: 理论, 方法, 议题与批评 (Paratexts and Research in Translation: Theory, Methodology, Issues, and Criticism). Journal of Foreign Languages 39: 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, Andrew. 2006. Book Design. London: Laurence King Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, Hermann. 1911. Weisheit des Ostens. In Münchner Zeitung. Reprinted in Hermann Hesse. 2012. Sämtliche Werke. 2 vols. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, pp. 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, Hermann. 1921. Tao Teh King von Lao Tse übertragen von H. Federmann. In Vivos Voco: Zeitschrift für neues Deutschtum. Reprinted in Hermann Hesse. 2012. Sämtliche Werke. 8 vols. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, p. 250. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Qingyun 胡清韵, and Yuan Tan 谭渊. 2021. 《西游记》德译本中副文本对中国文化形象的建构研究 (Research on the Construction of Chinese Cultural Image through Paratexts in the German Translation of Journey to the West). Chinese Translators Journal 2: 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Shaoxiang 华少庠. 2012. 卫礼贤德译本《道德经》诗性美感的再现 (The Reproduction of Poetic Aesthetics in Richard Wilhelm‘s Translation of the Daodejing). Social Sciences in Guangxi 210: 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1982. Zum Gedächtnis Richard Wilhelms. In Das Geheimnis der goldenen Blüte: Ein chinesisches Lebensbuch. Olten und Freiburg: Walter Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz, Corinne. 1994. On Telling/Selling a Book by Its Cover. Cultural Anthropology 9: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutner, Mechthild. 2003. Kontroversen in der Sinologie: Richard Wilhelms kulturkritische und wissenschaftliche Positionen in der Weimarer Republik. In Richard Wilhelm. Botschafter Zweier Welten. Frankfurt and London: Iko. [Google Scholar]

- Steavu, Dominic. 2019. Paratextuality, Materiality, and Corporeality in Medieval Chinese Religions. Journal of Medieval Worlds 1: 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Strauss, Victor von. 1870. LAO-TSE Tao Tê King. Leipzig: Friedrich Fleischer. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Victor von. 1987. LAO-TSE Tao Tê King. Zürich: Manesse Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Tadd, Misha. 2022a. 《老子》译本总目: 全球老学要览 (The Complete Bibilography of Laozi Translations: A Global Laozegetics Reference). Tianjing: Nankai University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tadd, Misha. 2022b. What Is Global Laozegetics?: Origins, Contents, and Significance. Religions 13: 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Yuan 谭渊. 2011. 《老子》译介与老子形象在德国的变迁 (Translation and Introduction of Laozi and the Transformation of Laozi’s Image in Germany). Deutschland-Studien 26: 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Yuan 谭渊. 2012. 从流亡到寻求真理之路—布莱希特笔下的老子出关 (From Exile to the Pursuit of Truth: “Laozi’s Departure” as Depicted by Bertolt Brecht). Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages 35: 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Xue 唐雪. 2019. 1945 年以前《道德经》在德国的译介研究 (A Study of the Translation of Daodejing in Germany before 1945). Journal of Yanshan University (Philosophy and Social Science) 20: 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Valussi, Elena. 2008. Female Alchemy and Paratext: How to Read nüdan in Historical Context. Asia Major 21: 153–193. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Richard. 1904. Die Chinesischen Klassiker. Die Welt des Osten 9: 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Richard. 1911. Laotse. Tao Te King. Das Buch des Alten vom SINN und LEBBN. Jena: Eugen Diederichs. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, Richard. 1967. Brief an Eugen Diederichs. In Eugen Diederichs Selbstzeugnisse und Briefe von Zeitgenossen. Düsseldorf-Köln: Diederichs Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Ruonan 徐若楠. 2023. 中国精神在德国的现代建构—卫礼贤中国典籍的翻译与接受 (Richard Wilhelm’s Translations of Chinese Philosophical Classics and Their Impact on Modern German Culture). Chinese Translators Journal 44: 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xu 张旭. 2020. “出版+文创”跨界融合背景下的书籍装帧设计 (Book Binding Design under the Background of Cross-border Integration of “Publishing + Cultural Innovation”). Editorial Friend 01: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yubo 朱宇博, and Weihan Song 宋维汉. 2022. The Shifting Depictions of Xiàng in German Translations of the Dao De Jing: An Analysis from the Perspective of Conceptual Metaphor Field Theory. Religions 13: 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chinese Classics | Foreword (Page) | Introduction (Page) | Footnote (Item) | Endnote (Item) | Post-Textual Interpretation (Page) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lunyu 论语 | 3 | 31 | 407 | - | - |

| Daodejing 道德经 | 3 | 29 | 1 | - | 25 |

| Liezi 列子 | 2 | 21 | - | - | 42 |

| Zhuangzi 莊子 | 2 | 17 | - | 463 | - |

| Mengzi 孟子 | 1 | 18 | 525 | - | - |

| Yijing 易經 | 2 | 11 | 50 | - | 70 |

| Lüshi Chunqiu 呂氏春秋 | - | 13 | 7 | 731 | - |

| Liji 禮記 | - | 18 | - | 588 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Tan, Y. A Paratext Perspective on the Translation of the Daodejing: An Example from the German Translation of Richard Wilhelm. Religions 2023, 14, 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121546

Li X, Tan Y. A Paratext Perspective on the Translation of the Daodejing: An Example from the German Translation of Richard Wilhelm. Religions. 2023; 14(12):1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121546

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaoshu, and Yuan Tan. 2023. "A Paratext Perspective on the Translation of the Daodejing: An Example from the German Translation of Richard Wilhelm" Religions 14, no. 12: 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121546

APA StyleLi, X., & Tan, Y. (2023). A Paratext Perspective on the Translation of the Daodejing: An Example from the German Translation of Richard Wilhelm. Religions, 14(12), 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121546