Religion in the Home—The Sacred Songs of the Drawing Room

Abstract

:1. Prelude

It is 1953. It is a Saturday evening, and we go to my grandparents in a small village in the New Forest. We—my mother, father and I—drive in our Austin Ruby Saloon through the beautiful tree-lined roads where ponies graze on the verge and deer may appear at any time. We walk through the post office run by Grandpa Boyce, passing the counter before we arrive in the back room where the circular table is covered with a lace cloth and fine china, patterned with ivy leaves. The teapot sits with the water jug, the milk jug and the slop bowl; the sandwich plates flaunt cucumber sandwiches with the crusts cut off. I am on my best behaviour. I wear my best dress as Grandma Boyce does not think that little girls should wear trousers or shorts.

The meal ends with Grandma’s Maids of Honour cakes and the table is cleared. Grandad sits down, with me sitting beside him, on the piano stool and plays a selection of the lancers, quadrilles and military two-steps—the repertoire he plays every Saturday evening for the village hop in the village hall. When the washing up is finished, the others return and my other grandfather—Grandpa Robinson—arrives from next door. He had been a gardener on one of the aristocratic estates in the New Forest but now owns his own nursery. He sings tenor regularly in the local village parish church choir. Grandpa Boyce is a Methodist but I do not think he had much relationship with The local chapel. The singing begins. He accompanies himself for ‘The Lost Chord’. My mother launches into ‘Arise O Sun’. Grandpa Boyce follows with ‘The Volunteer Organist’ and everyone joins in with the sort-of chorus. Grandpa Robinson, who is now a widower, starts his singing with’ The Holy City’. My mother follows with ‘Trees’ and finally, I am expected to sing my party piece ‘At the End of the Day’. This is the piece that I also performed at my mother’s concert party going round the old people’s homes. My father and my grandmother listen throughout.

The past, lived experiences of the researcher are privileged as sources of knowledge, as “stories worth telling” (Ellis and Bochner 2000). These “introspective stories” by autoethnographers serve to link emotion, embodiment, spirituality, morality, action, culture, history—in essence, linking the personal to the cultural and political (Ellis 2004, p. 37).

Epiphanies will be linked to embodied experiences that are rarely voiced in institutional religious contexts and the ethnographic writing that gives them voice can convey the complexity and ambiguity of our religious selves.

Autoethnography is an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno) (Ellis 2004; Holman Jones 2005). This approach challenges canonical ways of conducting research and representing others (Spry 2001) and treats research as a political, socially-just and socially-conscious act (Adams and Holman Jones 2008) … as a method, autoethnography is both process and product (Ellis et al. 2010).

His fertility was extraordinary, and though it is easy to be contemptuous of his drawing-room lyrics, sentimental, humorous and patriotic, which are said to number about 3000 altogether, it is certain that no practising barrister has ever before provided so much innocent pleasure.

We write to make sense of ourselves and our experiences (Kiesinger 2002; Poulos 2008), purge our burdens (Atkinson 2007), and question canonical stories—conventional, authoritative, and “projective” storylines that “plot” how “ideal social selves” should live (Tololyan 1987, p. 218; Bochner 2001, 2002).

Putting the narrating “I” under poststructural scrutiny helps us unsettle what is contained in our methodological history—“the tensions, the contradictions, [and] the heterogeneity within” this history (Caputo 1997, p. 9). Our mode of inquiry here and what we suggest for a new autoethnography, then, is conducted with an eye toward the excesses of experience and the narrating “I” in autoethnography. Cixous and Calle-Gruber ([1994] 1997) write, “All narratives tell one story in place of another story” (p. 178).

2. Spirituality

Nonconformist strength went on increasing, as the middle and working classes of the new industrial order continued to grow in numbers, wealth, political power and social esteem.

The religion of church and chapel mirrored the class division between the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie and the working class.

- Metaphysical, concerning the encounter with mystery (Lancaster 2004; Tisdell 2007), connection with a life force, God or higher power.

- Narrative, which “refers to the fund of ‘story’ in which an individual ‘dwells’ andthat constitutes the primary reference for religious identity” (Pratt 2012, p. 4), often relating to a particular tradition such as Islam, Buddhism and Christianity.

- Intrapersonal (within the person), often identified as transformation and change (Boyce-Tillman 2016; Mezirow 2000), characterised by empowerment, bliss and realisation (Claxton 2002) and a sense of coming home and being at peace with oneself (Jorgensen 2008, p. 280).

- Interpersonal (relational), relating to belonging and group empathy (Kaldor and Miner 2012, p. 187).

- Intergaian (relationship with the natural world), an experience of a sense of oneness and deep relationship with the other-than-human world (Kaldor and Miner 2012, p. 187; Boyce-Tillman 2010).

- Extrapersonal/Ethical, a concern for local and global ethical behaviour and the interconnectedness of all things (Tisdell 2007).

- Tradition, the use of practices from a particular tradition, often not within the context of that religious tradition (based on Boyce-Tillman 2016, pp. 73–9).

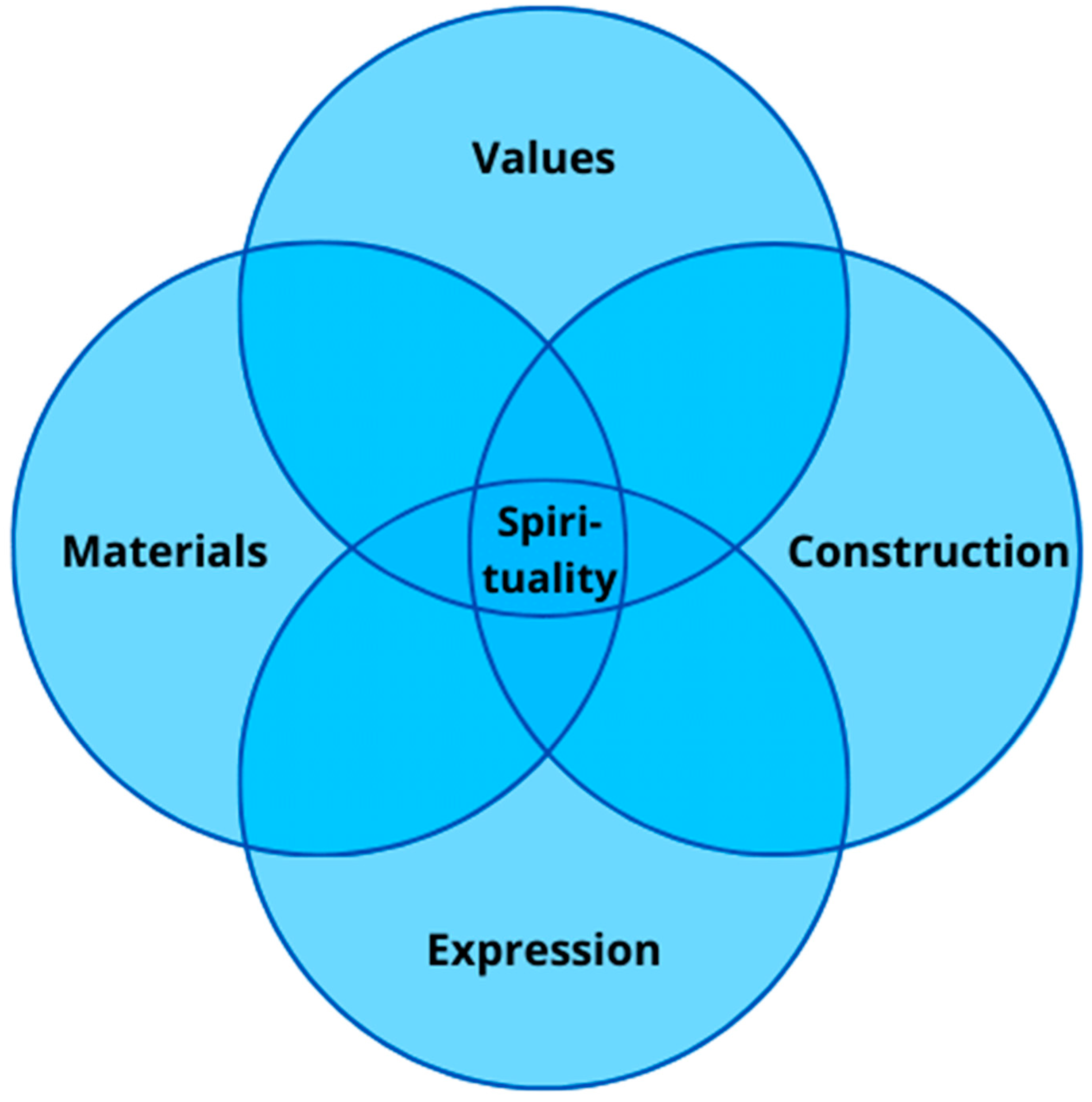

- The Materials making the sound, such as instruments and voices;

- The Expression, including the mood, feeling and emotions expressed;

- The Construction1, which concerns the shape of the form that is repeated and how often and how the ideas are put together;

- The values, which include the context and the cultural context.

3. The Cultural Context of the Secularisation of Spirituality

- The short strophic song resembling the hymn;

- The song modelled on the solo found in oratorio or drawn from an oratorio;

- The genteel style of ballad already familiar in the drawing room often concerning romantic love;

- The solo sacred song.

They took on a marked secular quality as their musical style became indistinguishable from the other ballads with which they vied for success in the ballad boom of the 1880s.(Scott 2001, 2023)

- Claribel Sacred Songs and Hymns published posthumously in 1869;

- Boosey Sacred Songs, Ancient and Modern (edited by J. Hiles), 1870s;

- Metzler Forty Sacred Songs second of their Popular Musical Library from 1873;

- Charles Sheard—Sacred Songs from 1874 with accompaniments for piano or harmonium.

- Shield’s The Wolf—a through-composed aria;

- Moore’s The Last Rose of Summer—strophic air;

- Bishop’s Home, Sweet Home!—verse with refrain;

- Horn’s Cherry Ripe—rondo form4;

- Russell’s The Maniac—an operatic mad scene.

- Character numbers often concerning adult males such as blacksmiths, bellringers and watchmen but seldom factory workers.

- Moral ballads with moral lessons;

- Love songs;

- Separation and death;

- Songs concerning the poor and the marginalized;

- Patriotic songs;

- Disaster songs often treated as operatic scena;

- Nostalgia for an imagined past;

- Songs for the young to sing, usually selected by the older family members. (Based on Scott 2001)

4. The Lost Chord 18775

I sit by the side of Grandpa Boyce on the double piano stool. The design of the cover of the song fascinates me with curling letters that make it look somewhat old. The name of the lyricist is Adelaide which also seems somewhat grand. My Grandpa starts to play and I watch his big hands over the keys. It starts low and the notes sound rather like the music of the organ in church. It builds up in the height of the notes and the volume but then decreases in volume until the voice comes in. His foot operates the right-hand pedal all the time6. His fingers press the chords gently and the song starts on a single note:

Seated one day at the organ, I was weary and ill at ease.

And my fingers wandered idly over the noisy keys;

More notes appear in the piano and the key shifts. I feel the intensity rising as we approach the Amen. It is repeated, getting slower as the volume rises:

I know not what I was playing or what I was dreaming then,

But I struck one chord of music, like the sound of a great Amen.

The first verse is over, and the piano starts again, as at the opening. Grandpa’s voice starts softly. The notes are repetitive again and the piano is high; I see the vision of the angels in my mind. I love angels. The key moves forward but it is still peaceful:

It flooded the crimson twilight like the close of an Angel’s Psalm,

And it lay on my fevered spirit with a touch of infinite calm.

It quieted pain and sorrow like love overcoming strife,

It seemed the harmonious echo from our discordant life.

His right hand repeats an octave over and over; I marvel because I find octaves so difficult with my small hands:

It linked all perplexed meanings into one perfect peace,

It trembled away into silence as if it were loath to cease;

The peace seems to be evaporating as the speed increases while the octaves continue. The speed of the chords doubles. They are bright major chords and I feel a sort of desperation; I try to imagine an organ with a soul:

I have sought, but I seek it vainly, that one lost chord divine,

Which came from the soul of the organ, and enter’d into mine.

It becomes grander. The big chords are slower, and I marvel at how Grandpa’s fingers move so swiftly across the whole keyboard. His big hands seem so strong and in command of the piano.

It may be that Death’s bright Angel will speak in that chord again;

Death’s bright angel enters my thoughts as the accented chord paints it so fiercely using a tune similar to the ‘crimson twilight’ before; I wonder at the majesty of it all. Everything in the music and me rises as the tune rises to its top note with an amazing chord that lifts me into a new place:

It may be that only in Heav’n I shall hear that grand Amen.

This has always been one of my favourite songs and can still transport me to a different way of knowing despite all the criticism and satire that has been levelled at it. Its composer, Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (1842–1900) composed it during his brother’s final illness in 1877 when he was becoming better known, although few of the operettas for which he is famous had been written then. He was still relatively poor, although this song was to bring him many royalties when Boosey & Co. began their ballad concerts involving professional singers. He dedicated some of his ballads to famous singers, which helped them raise money. This song was immediately successful (Jacobs 1984, p. 2) and had great commercial success in Britain and America in the 1870s and 1880s, reaching sales of half a million by the end of the nineteenth century. It was taken up by the American singer, Antoinette Sterling, who may have asked him to set the poem. It did receive its first performance at a ballad concert, sung by Sterling, with Sullivan at the piano and Sydney Naylor at the organ. The song was also sung by Mrs. Ronalds, a rich American society hostess with a flourishing London salon, who became Sullivan’s mistress. The Prince of Wales remarked that he would travel anywhere in the British Isles to hear her sing it. The outstanding contralto Clara Butt also became associated with it and saw in it the grandeur of Beethoven7. Her voice was a legend that still existed in my parents’ day. Her voice was so rich, full and powerful that Sir Thomas Beecham declared that it could be heard in France.8 It is a timbre that is not so greatly favoured today but which I think influenced the way that female singers approached the sacred ballad—not fearing the power and timbre of the mature woman’s voice. Clara Butt saw fit to accompany it in later ballad concerts with a speech affirming the Christian Science of Mary Baker Eddy, in case the audience did not get the religious message of the song. It was later recorded by Enrico Caruso who had sung it in a benefit concert for the victims of the Titanic. Sullivan saw the song as one of his best works (Encyclopedia Titanica 2023). In 1888, it was the subject of one of Thomas Edison’s first recordings in a version for cornet and piano.Grandpa is singing at his loudest. The voice is powerful. The words are repeated, and the speed slows; the notes get slower and longer and longer. The first syllable of the Amen seems to last forever. I too have found a chord inside me and I long to stay there with my Grandpa forever.

5. Arise O Sun 1921

The Victorian ‘perfect lady’ was innocent and chaste before marriage and a devoted wife and caring mother after marriage. Her education took place within the family, and the range of subjects she could study was limited by the fear of making her opinionated and therefore less submissive to her future husband’s views. Literary, artistic and musical skills were thought appropriate for female study. The mechanics of the subjection of women were to be found in the ideologies of purity, chastity and the family. Female sexuality was repressed by the ideology of purity and found sublimation in religion, motherhood and the spiritual side of love.

My grandfather starts the big opening chords—a demanding piano part even at the opening. It is strongly in a major key with rising intervals in the vocal part imploring:

Arise, O sun, and shine o’er land and sea

Bring to the world, the glorious day to be

Accompanied by simple chords the tune is repeated as:

The stars are fading and the night is done

Arise O sun and shine into our hearts

For at thy bidding weariness departs

The request to

Show us the way and faithful we will run

Arise, O sun

takes us to the dominant key again and I feel the power of the grandiose triplets on the piano heralding the triumphant final verse—a formula often used for requesting divine intervention. This is accompanied by the chords sounding all over the keyboard similar to ‘The Lost Chord’. Again, I marvel at my grandfather’s huge hands managing this grand pianistic landscape:

Arise O sun, O light of love arise

When to God’s morning we shall raise our eyes

The long night ended and the battle won

Inside, I rise too into God’s morning, whatever this might be. The piano chords now have added sevenths,15 giving the music a grandiose intensity.

The final

Arise, arise, O sun

contains the song’s highest note which my mother approaches with caution. I know that sometimes she is forced to transpose it down the octave. She holds the top note as long as possible accompanied by a chord of the dominant thirteenth. I pray that her breath will hold out. The penultimate note has tenuto16 over it and occasionally my mother risks a small mordent17 to decorate it, if she has the breath. The final sustained note reminds us of the middle verse. There is a chord that is reminiscent of the middle verse (the flattened submediant chord) before returning safely to a strong tonic major chord to end.

6. The Volunteer Organist 189318

Grandpa Boyce picks up the organ theme again with ‘The Volunteer Organist’, written by William B. Gray and George Spaulding and published in 1893. I like the story. It is set in a church and centring on an organ gives it a religious atmosphere, but I never found that this could move me in the same way as the previous numbers. The form is very simple—two verses with the same tune and the same chorus for each. I find it very easy to follow. But I miss Grandpa’s spreading hands over the big chords of ‘The Lost Chord’ and ‘Arise O Sun’. I call the accompaniment ‘oom-jah’—a single octave in the left hand and a three-note chord in the right. The introduction simply introduces the tune of the song, similar to the overture to an operetta rather than the scene setting of the other openings. I see that it is called a descriptive song; it simply tells a story rather than drawing me into a different way of knowing. I am, however, fascinated by the story because again it is an organ and organist that draws a congregation into a profound religious experience. The song describes a Sunday church service whose organist is ill. A request by the preacher for a volunteer produces a ragged staggering man, who the congregation assumes is drunk. However, the music he makes is more moving than the preacher’s sermon as it

Told his own life’s tale

In the chorus, Grandad makes sure that I hear the melody of the tune of ‘All people that on earth do dwell’ in the accompaniment and I enjoy the fact that I have learned the chorus and can join in with it. The man leaves and the preacher asks the amazed congregation to pray. There is not the dramatic lengthened ending of the earlier songs.

7. The Holy City 189220

If the words were particularly moving, he would frequently break down with emotion and have to wait until he could compose himself sufficiently to continue.

At the opening, Grandpa Boyce’s rising piano chords give a sense of expectancy. The opening words set the dream sequence:

Last night as I lay sleeping there came a dream so fair

It is semi-spoken, like operatic recitative and Grandpa’s beautiful tenor voice draws me into the dreaming story. There is little melody, and the simple chords underneath seem to support the story and occasionally add greater depth. The appearance of the angels in the text makes the chords become more sustained. The mood builds and a tune that I know starts too. I am excited by the angels, and the semiquaver chords that my Grandpa Boyce executes so easily add to the feeling—emerging strongly, fading and slowing into the cries of ‘Jerusalem’ which start softly and build over the pulsating triplets summoning the Divine presence. I always wait for this passage that is like a chorus:

Jerusalem! Jerusalem, Lift up your gates and sing, Hosanna in the highest, Hosanna to your King!

It feels secure in the tonic major and I feel safe and loved. Grandpa Robinson pulls the time out as the verse closes and Grandpa Boyce stays with him on the piano beautifully. The piano chords keep my mood strong.

The second verse starts just like the first, softly, but the scene changes. I do not like the shadow of the cross appearing up a lonely hill. I am always frightened by the cross as it always makes me feel guilty about what I have done to hurt Jesus. Words from Stainer’s ‘Crucifixion’, echo in my head:

Is it nothing to you all ye that pass by?

I feel that I have rejected Jesus in a way about which I am not quite clear. Fortunately, this does not last long here for we are already building up to the Jerusalem sequence with changed words but the same tune. I feel safe and protected, even redeemed from the guilt that I experience so regularly in church.

The third verse starts differently. The chords in the piano are sustained and the pace moves forward. There is more chromaticism, and I am uncertain about what will emerge. But we return safely to the secure tonic key to emphasize:

But all who would might enter and no-one was denied.

I love this line. I, who indulge regularly in the self-examination exhorted by my confirmation book with disastrously distressing effect, am very glad that no-one—not even me, a miserable sinner—is denied. My excitement rises as we no longer need stars or moon. The speed ebbs and flows leading to the last repetition of the chorus-like section. A modulation to the dominant sets up the expectant mood. The Jerusalem tune is as before but Grandad takes much more license as it comes to the end, pulling out the length of the notes and adding pauses in what seem very high notes—but he is a tenor.

8. Trees 191321

My mother takes over with another of her and my favourite songs, ‘Trees’ by Joyce Kilmer from 1913 set to music by Oscar Rasbach. It is a simple poem of two-line rhyming stanzas (Kilmer 1886–1918) which I have learned by heart and recite at school. It combines the beauty of the environment with Christianity—in this case, Kilmer’s Roman Catholic Faith. The poem sees the feminine tree as looking toward God and proceeding from Mother Earth—which I love. God is never feminine in my experience in church. Its skyfacing leaves are seen as praying, while the robin’s nest enhances her hair—a beautiful picture and close to a feminine version of the Divine. I understand this view of the trees of the New Forest that I love so much. The rhythm of the poem dictates the prevailing rhythm of the song, making it easy for me to grasp and remember musically and in spoken form. The piano introduction sets up that rhythm with thick chords. It adds grandeur to the poem and throughout the setting, the chromaticism, and the 7ths and 9ths added to chords intensify what seems to me a very simple poem. Near the end, the rhythm changes and my mother adds her own rubato22 here—pulling the tempo about. Sometimes she does this more than at other times. It depends on the audience and her own emotional state at that time. Both her singing and the harmony emphasize the last two lines:

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

The closing chords include a striking flattened chord which for me adds to the feeling of this beautiful song.

Sometimes a tune gets stuck in my head, and I find myself singing the song over and over again. Today I was happily singing, ‘I think that I shall never see, a poem lovely as a tree…’ …Singing that song resurrected memories of the tropical trees in our garden in Bombay, India when I was growing up, a long, long time ago.

As my mind’s eye now travels around that garden, I can see the tall coconut tree, and trees laden with fruit: guava, mango, papaya, chickoo, jackfruit, custard apple, and pomegranate. I was in a paradise, and never knew it! … [It] made me think of some significant biblical stories that have happened around trees. Stepping into the Garden of Eden in Genesis, the trees there, were ‘pleasing to the eye and good for food.’ (Gen 2:9) … Gazing in awe at the pink blossoms on the crab-apple trees leaning over our fence, I sang along with Mario Lanza’s soulful recording, the end of the song that had haunted me all day...”

9. At the End of the Day 1951

The piano introduction is gentle, suggesting a winding down at even tide. The tune resembles a waltz—a rhythm found in very few pieces of the gatherings that I remember except Grandpa Boyce’s dance tunes. My mother made sure that I did pray each night by kneeling down every night with hands pressed together. The tune is simple and predictable, and the harmony is simple. I really have done what I am singing about,

tried to be good because I know that I should

There is no indication that there will be judgement if I fail—just gratitude—no self-examination and guilt. So, as the dawn comes, there is a faster section in the middle in 6/8 which modulates to the dominant which is brighter and hopeful in order to lead to the next section about power which is more confident and faster. I tell people they should welcome everyone. As the next section starts—still softly—I always get a bit anxious as the music broadens—getting louder and slower approaching the highest note in the song. If it is a good note and the note starts well and I have enough breath, I will sustain it as long as possible. If it is not safe, I will quickly embark on the descent to the end of the section. The first section now returns. The accompaniment has many more chords than its earlier appearance, not unlike the closing sections of ‘The Holy City’ and ‘The Lost Chord’. I cannot rival my grandfather’s volume but I sing as loud as I can safely, and hope I can do credit to the revised ending that rises up higher than the first verse. The final note is as high as the one in the section before; so, I have already seen how well the high note will go in this performance. I like singing this song, setting out the possibility of a less religious but nonetheless moral new generation. I sing it regularly in the old people’s homes. I know they love it because it affirms their faith in a new generation. I am being the good little girl that my parents and the wider society will affirm—if I try hard enough to be good and help other people. Fortunately, I am not confronted with the guilt of not getting it right that has plagued my young spiritual life.

10. Summary

Cathedrals … seek to offer an experience without requiring evidence of faith credentials or pressure to join the club. It is precisely that liminal threshold which Tavener exemplifies. If you happen upon a Cathedral and stay for Evensong, the glory of Tavener’s music can come as sheer grace. You are simply invited to let it anoint you with its costly perfume. It is a gift. No one is demanding anything first, checking your fitness or looking for the right answers. A door is opened in Heaven. It is a moment of Christ-inspired generosity. The kingdom is offered without restriction or condition.

11. Postlude

The car is now a Ford Mazda. The road through the forest is part motorway (M27) and part dual carriageway. I do not think the post office exists anymore. I doubt if there are community dances every Saturday as the village hall is now probably expensive apartments. I do not know who got the round table or the piano when my grandparents died, but I do have two of their chairs. I do cherish my grandfather’s bound volume of schottisches, quadrilles, and military two-steps that he played each Saturday night. I used the military two-step ‘Over the Top’ in one of my pieces about the New Forest with grandfather’s name in it.

These gatherings ended when my grandparents died. The ivy leaf tea set is now in my loft and unlikely to be sought-after by my two sons. There are no more Maids of Honour, or big hands on a piano or my mother’s aging voice. These have been replaced by recordings, radio, television and the Internet. At that time, I was going to church, as expected of me by my parents, although I was already starting to question what was taught there. In church, I learned about God, but, in these musical gatherings, I encountered the experience of the Divine which had a variety of names. In church, to understand God, I needed to know the meaning of certain significant words all of which ended in ‘tion’—incarnation, creation, redemption, salvation. I do not remember there being any of those words in the drawing-room songs. Their words were relatively simple and understandable. Prayer for me at that time involved the acronym ACTS—adoration, confession, thanksgiving and supplication—more ‘tions’. My prayer involved much self-scrutiny as to whether I had done it right. The simplicity of prayer as set out in ‘The End of the Day’ was appealing and let me off the self-persecution of the religious teaching.

I went on to study music and learn that this music was sentimental and to be despised. I think my own satirisation of ‘The Lost Chord’ was an attempt to belong in these circles and share their value systems. But at Oxford in the 1960s I could not belong. There were only three women in my year and thirty-six men, who, in general, had come through the cathedral choir schools from which I had been excluded. There were no women lecturers and no women in the curriculum. There was little place for a grammar school girl.

I realise that in those drawing-room gatherings I did have a place and a contribution to make. Controlled by the adults concerning my repertoire, nevertheless, I had an offering alongside them, unlike in the church worship. I reflect on my best-known hymn (Boyce-Tillman 2006) We Shall Go Out and its final line

Including all within the circles of our love (Boyce-Tillman 2006, pp. 80–81)

I wonder if that line was born in The Holy City:

And all who would might enter and no-one was denied.

I entered a world of pass/fail examinations, competitive festivals and final recitals where I was compared with others and external standards. In these Saturday gatherings, I was who I was and was valued for that. The sounds of all the participants were valued, even though two participants did not sing. These are the ones—my father and grandmother—who I feel I knew least. I found out about the adults in my family through their singing—the power of Grandpa Boyce, the sweet tenor of Grandpa Robinson, the aging tones of my mother.

All the elements I identified at the beginning of this article were there. I encountered a metaphysical presence—only sometimes called God. There were profound interpersonal relations and sharing. Many of the pieces included extrapersonal/ethical elements, particularly what I was asked to sing. There were intergaian elements—in a post office in the New Forest—the sun and the trees, for example. They linked with my experience in a school assembly whose songs were drawn from the hymnbook ‘Songs of Praise’ (Dearmer et al. 1925) which—in an effort to be less denominational—found the natural world a safer place to find the divine rather than dogma and creed. ‘Morning has broken’, ‘All things bright and beautiful’ and ‘Daisies are our silver’ were some of my favourites. They certainly transformed me intrapersonally. My young voice was not being taught or corrected—it was simply accepted as it was. I had a valuable practical contribution to make, which was more than I could say about the church and religion. I realised in writing this paper how the sacredness of these gatherings shaped me.

There is a regret about what the initiation into the classical tradition made me feel about this repertoire—now still clearly loved when I look at the numerous recordings on YouTube and the songs the Caribbean members of my congregation enjoy. If Sunday church music was sometimes boring then, and I was excluded, these pieces represented a context in which I was included, and maybe my interest in religionless spirituality began with ‘The Lost Chord’. If the Church was complicated, mostly spoken and exclusive, the drawing-room gatherings were simple, inclusive and totally sung.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the domain of Construction, I have used technical terms such as ‘dominant thirteenth chords’ in my autoethnographic accounts, although such technical terms would not have been familiar to me at the age I was for these experiences. I do this to describe the Construction of these songs for the reader and the way that their often intense expression was achieved. |

| 2 | These domain names are given capital letters in the text. |

| 3 | Strophic form uses the same tune for each verse. |

| 4 | In rondo form a tune recurs regularly in a piece interspersed with contrasted sections. |

| 5 | The Lost Chord is available on YouTube: youtube.com/watch?v=f9L-L6X4xBY (accessed on 10 August 2023). |

| 6 | The so-called sustaining pedal which was needed to sustain the big chordal accompaniments of the songs. |

| 7 | Available on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_bauqCoMOMM&NR=1&feature=fvwp (accessed on 14 August 2023). |

| 8 | See http://www.cantabile-subito.de/Contraltos/Butt__Clara/butt__clara.html (accessed on 23 August 2023). |

| 9 | See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQ9KUuqsBlQ (accessed on 14 August 2023) and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9L-L6X4xBY (accessed on 14 August 2023). |

| 10 | A pedal is a note repeated during several bars of a song. |

| 11 | The term chromatic refers to notes which are outside the notes of the key in which the song is situated. |

| 12 | Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWETTdRCWXA (accessed on 23 August 2023). |

| 13 | This is the key based on the fifth note of the original scale. |

| 14 | This is a minor scale based on the home key of the song. |

| 15 | To the three notes of a chord a fourth one is added seven notes above the root note of the chord. |

| 16 | Tenuto means hold and is the equivalent of a pause and involves lengthening the note if possible. |

| 17 | This is a little extra two notes—a ‘twiddle’—a decoration of the original note. |

| 18 | The The Volunteer Organist is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwAFRXAUMnE (accessed on 25 August 2023). |

| 19 | This instrument has a reedy tone, is operated by a hand-operated bellows and is used to produce long single notes to accompany singing. |

| 20 | The Holy City is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KG9pYsTc8vk (accessed on 25 August 2023). |

| 21 | The Trees is available YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GcnnUpsAVRI (accessed on 25 August 2023). |

| 22 | Rubato is a term used to indicate when a singer pulls the original rhythm about, going faster and slower for often for emotional effect. |

| 23 | Available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkpFKiuzmuQ (accessed on 25 August 2023). |

| 24 | Available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jeVI1apgT0w (accessed on 25 August 2023). |

| 25 | This style of singing not only centres on a note by moves around it—often called wobbling in a disparaging way—but part of an older woman’s singing style and timbre. |

References

- Adams, Tony E., and Stacy Holman Jones. 2008. Autoethnography is queer. In Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies. Edited by Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln and Linda T. Smith. London: Sage, pp. 373–90. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Matthew. 1932. Culture and Anarchy. Edited by J. Dover Wilson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Athaide, Viola. 2023. Those Tantalizing Trees. Available online: https://ignation.ca/2020/10/15/those-tantalizing-trees/ (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Atkinson, Robert. 2007. The life story interview as a bridge in narrative inquiry. In Handbook of Narrative Inquiry. Edited by D. Jean Clandinin. London: Sage, pp. 224–45. [Google Scholar]

- Atwell, James. 2020. Postlude. In Hearts Ease: Spirituality in the Music of John Tavener. Edited by June Boyce-Tillman and Anne-Marie Forbes. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 275–79. [Google Scholar]

- Autoethnography. 2023. Available online: https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/untitled-f37b8157-fac5-4cdf-9673-880f0d013c86/section/52742b90-2204-474c-97c0-0e27ec51f642 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Bochner, Arthur P. 2001. Narrative’s virtues. Qualitative Inquiry 7: 131–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochner, Arthur P. 2002. Perspectives on inquiry III: The moral of stories. In Handbook of Interpersonal Communication. Edited by Mark L. Knapp and John A. Daly. London: Sage, pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Tillman, June. 2000. Constructing Musical Healing: The Wounds that Sing. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Boyce-Tillman, June. 2006. A Rainbow to Heaven. London: Stainer and Bell. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Tillman, June. 2010. Even the stones cry out: Music Theology and the Earth. In Through Us, with Us, in Us: Relational Theologies in the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Lisa Isherwood and Elaine Bellchambers. London: SCM Press, pp. 153–78. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Tillman, June. 2016. Experiencing Music—Restoring the Spiritual, Music as Wellbeing. Oxoford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, John. 1997. Deconstruction in a Nutshell. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Heewon, Faith Wambura Ngunjiri, and Kathy-Ann C. Hernandez. 2013. Collaborative Autoethnography. New York: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cixous, H., and M. Calle-Gruber. 1997. Rootprints: Memory and Life Writing. Translated by Eric Prenowitz. New York: Routledge. First published 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Claxton, Guy. 2002. Mind Expanding: Scientific and Spiritual Foundations for the Schools We Need. Public Lecture. Bristol: University of Bristol. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Guy. 1997. The Geography of the Imagination. Jaffrey: David R. Godine. [Google Scholar]

- Dearmer, Percy, Martin Shaw, and Ralph Vaughan Williams, eds. 1925. Songs of Praise. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn, and Art Bochner. 2000. Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. London: Sage, pp. 733–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2010. Autoethnography: An Overview [40 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopedia Titanica. 2023. The Lost Chord. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/lost_chord_caruso.html (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Foucault, Michel, and Colin Gordon, eds. 1980. Power Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–77. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, Rosemary. 2019. Music and Mass Education: Cultivation or Control? In Music and Victorian Liberalism: Composing the Liberal Subject. Edited by Sarah Collins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 60–80. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Solomon. 1994. The Lost Chord, The Holy City and Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Available online: https://www.lycoming.edu/umarch/chronicles/1995/7.%20GOODMAN.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Gounod, Charles. 1856. Jésus de Nazareth. Paris: Choudens. [Google Scholar]

- Holman Jones, Stacy. 2005. Autoethnography: Making the personal political. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Cambridge: Sage, pp. 763–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hullah, John. 1841. Wilhem’s Method of Teaching Singing: Adapted to English Use, Under Supervision of Committee of Council on Education. Cambridge: John W. Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Iturbi, Jose. 2023. Fantasie Impromptu. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3P8GZ-EZOe8 (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Jackson, Alecia Y., and Lisa A. Mazzei. 2008. Experience and “I” in Autoethnography A Deconstruction. International Review of Qualitative Research 1: 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Arthur. 1984. Arthur Sullivan: A Victorian Musician. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, Estelle J. 2008. The Art of Teaching Music. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldor, Sue, and Maureen Miner. 2012. Spirituality and Community Flourishing—A case of circular causality. In Beyond Well-Being—Spirituality and Human Flourishing. Edited by Maureen Miner, Martin Dowson and Stuart Devenish. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, pp. 183–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesinger, Christine E. 2002. My father’s shoes: The therapeutic value of narrative reframing. In Ethnographically Speaking: Autoethnography, Literature, and Aesthetics. Edited by A. P. Bochner and C. Ellis. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, Brian L. 2004. Approaches to Consciousness: The Marriage of Science and Mysticism. Lomdon: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, John Henry. 1904. Olivet to Calvary. London: Novello. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, Margaret. 1997. Labour and Childhood. London: Swan Sonnenschein. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, John. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Process. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. 1960. Music in Schools. Pamphlet no. 27. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Poulos, Christopher N. 2008. Accidental Ethnography: An Inquiry into Family Secrecy. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Douglas. 2012. The Persistence and Problem of Religion: Exclusivist Boundaries and Extremist Transgressions. Paper presented at the Conference of the British Association for the Study of Religion, Winchester, UK, September 6. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, Adelaide Anne. 1860. The Lost Chord. The English Woman’s Journal 36. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Derek. 2001. The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlor, 2nd ed. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Derek. 2004. The Musical Soirée: Rational Amusement in the Home. The Victorian Web. Available online: https://victorianweb.org/mt/parlorsongs/scott1.html (accessed on 30 September 2009).

- Scott, Derek B. 2013. Music, Morality and Rational Amusement at the Victorian Middle-Class Soirée. In Music and Performance Culture in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Temperley. Edited by Bennett Zon. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Derek. 2023. The Victorian Web. Available online: https://victorianweb.org/mt/dbscott/7.html (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Southcott, Jane. 2019. Sarah Anna Glover: Nineteenth Century Music Education Pioneer. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spry, Tami. 2001. Performing autoethnography: An embodied methodological praxis. Qualitative Inquiry 7: 706–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainer, John. 1887. Crucifixion. London: Novello. [Google Scholar]

- The Times obituary, 1929 September 9, p. 7.

- Tisdell, E. 2007. In the new millennium: The role of spirituality and the cultural imagination in dealing with diversity and equity in the Higher Education Classroom. Teachers College Record 109: 531–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tololyan, Khachig. 1987. Cultural narrative and the motivation of the terrorist. The Journal of Strategic Studies 10: 217–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Heather. 2014. Writing Methods in Theological Reflection. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boyce-Tillman, J. Religion in the Home—The Sacred Songs of the Drawing Room. Religions 2023, 14, 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111400

Boyce-Tillman J. Religion in the Home—The Sacred Songs of the Drawing Room. Religions. 2023; 14(11):1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111400

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoyce-Tillman, June. 2023. "Religion in the Home—The Sacred Songs of the Drawing Room" Religions 14, no. 11: 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111400

APA StyleBoyce-Tillman, J. (2023). Religion in the Home—The Sacred Songs of the Drawing Room. Religions, 14(11), 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111400