3.1. Background: Photographs and Their Story

Everybody faces a blank piece of paper, no matter what they’ve written or painted or composed before. I can’t imagine approaching every single project without doubt.

Stephen Sondheim

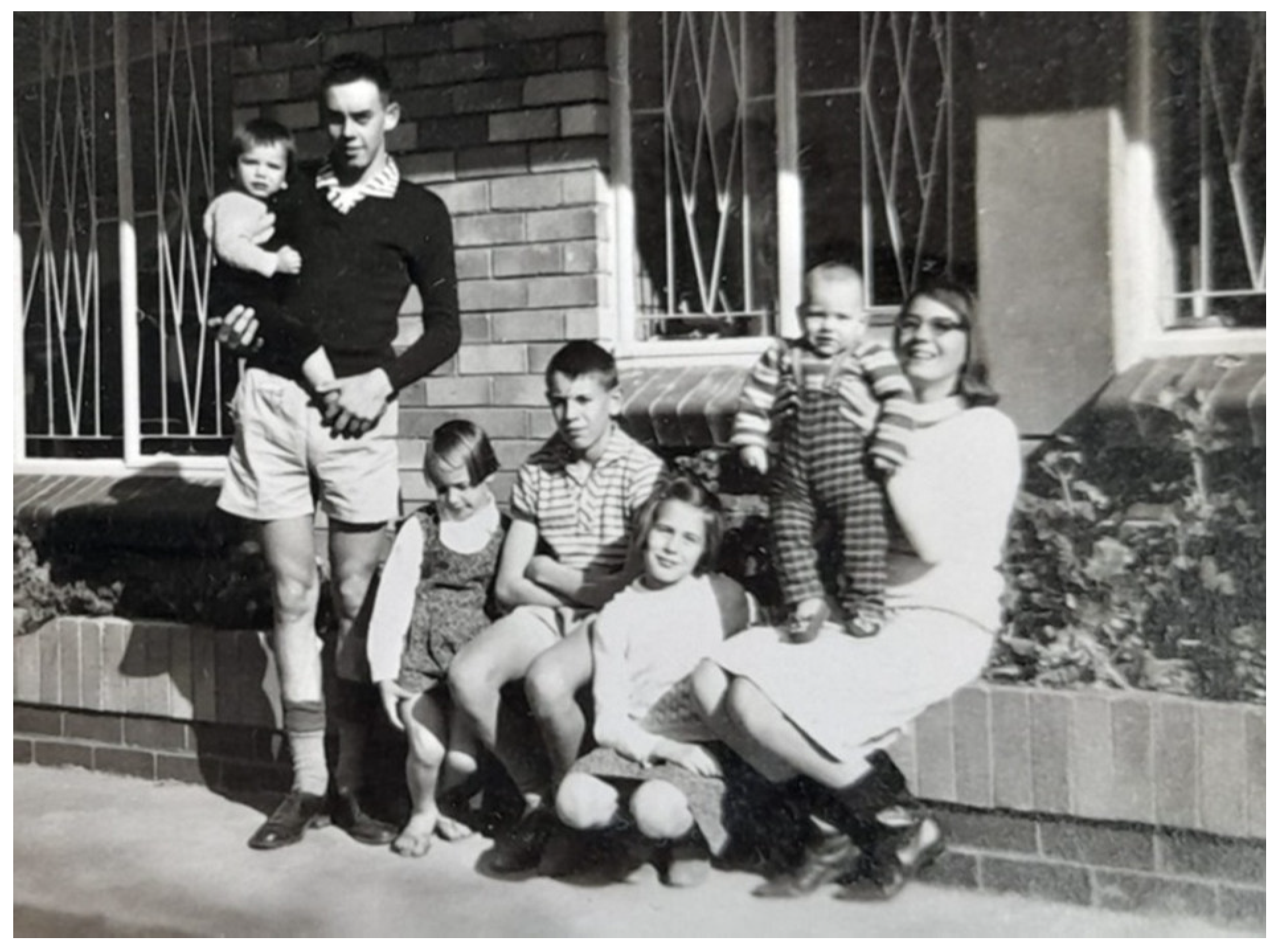

In this photo (

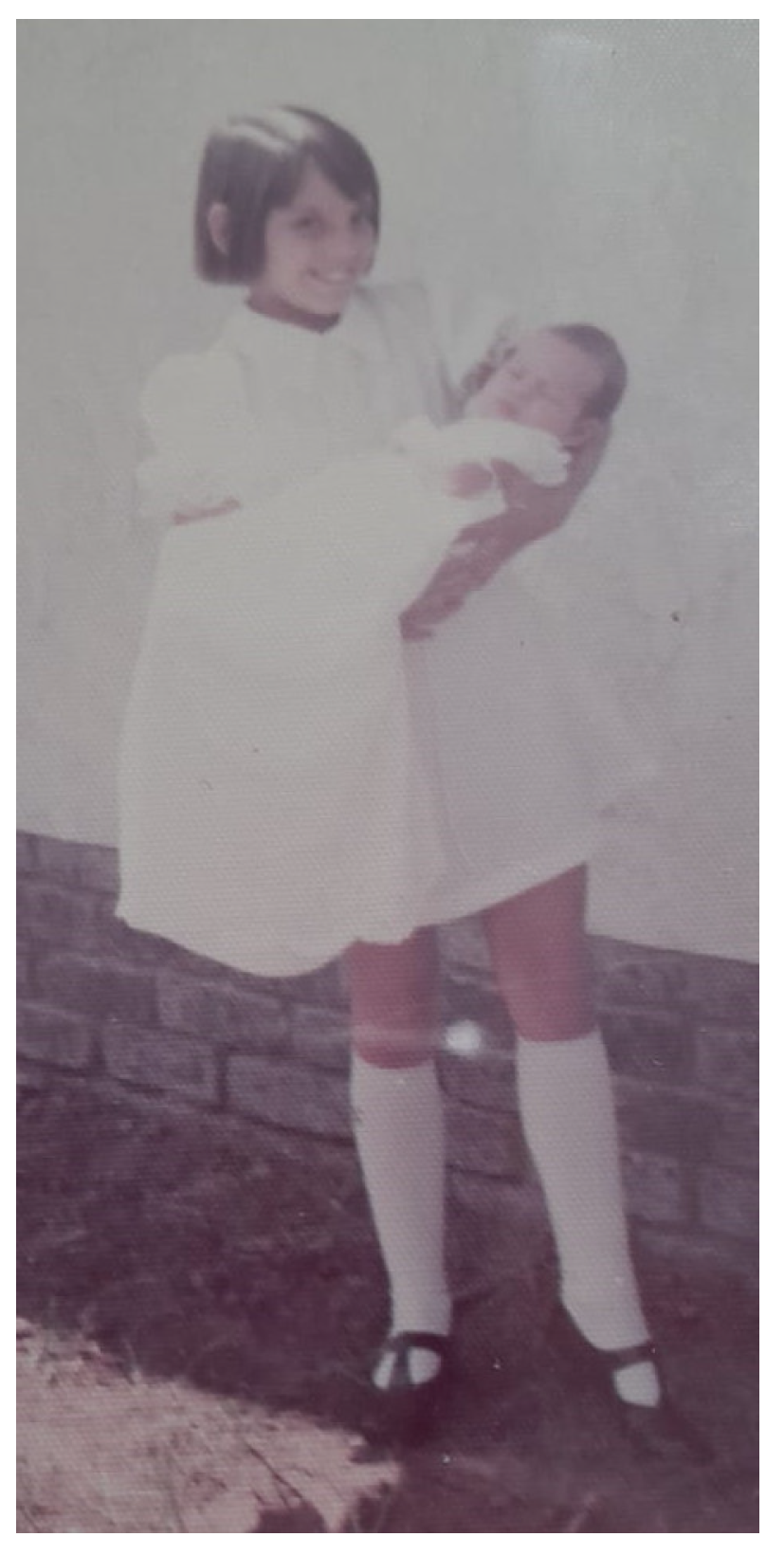

Figure 1), Henry is on the left with me on his arm with all our siblings. This picture already portrays the bond there was between us. It is clear in the photo, in the way he holds me and holding my other foot, that he cared for his little sister. I am the sixth of seven children and Henry, my oldest brother, was 17 years my senior. From a very young age, our relationship was established through music. We both studied music. I remember very well how I ran home from school to join him when he started his music teaching career at a high school in the afternoons. I was a bridesmaid at his wedding (

Figure 2). This was a highlight in my young life, as it was the first time that I played such an ‘important part’ at a wedding! Getting my hair done and wearing the long dress was particularly special. To this day, I still have my mini wedding album, which my mother put together for me at the time.

When I was asked to carry his first-born son to the pulpit for his baptism (

Figure 3) three years later, I felt noticed by my brother. It was only weeks after my grandmother had passed away and having this responsibility to hold a new life in my arms, was significant, and it certainly strengthened our bond.

We were brought up in a Christian home, and our bond in faith and music was strong. Our father passed away when I was 15, and because Henry was already married by then I was unaware of his intentions. He tried to fulfill the role of father to my youngest brother and me.

In 1983, I went to university, and the following year Henry was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Due to the big age gap, I was not involved in his life much at that stage and had no idea how this diagnosis impacted him. My only memories are of him in and out of institutions for years. In 2004 we fetched him from an institution when our mother passed away. Everybody was nervous and unsure about how he would behave at the funeral. It was 20 years since the diagnosis and his condition remained unchanged.

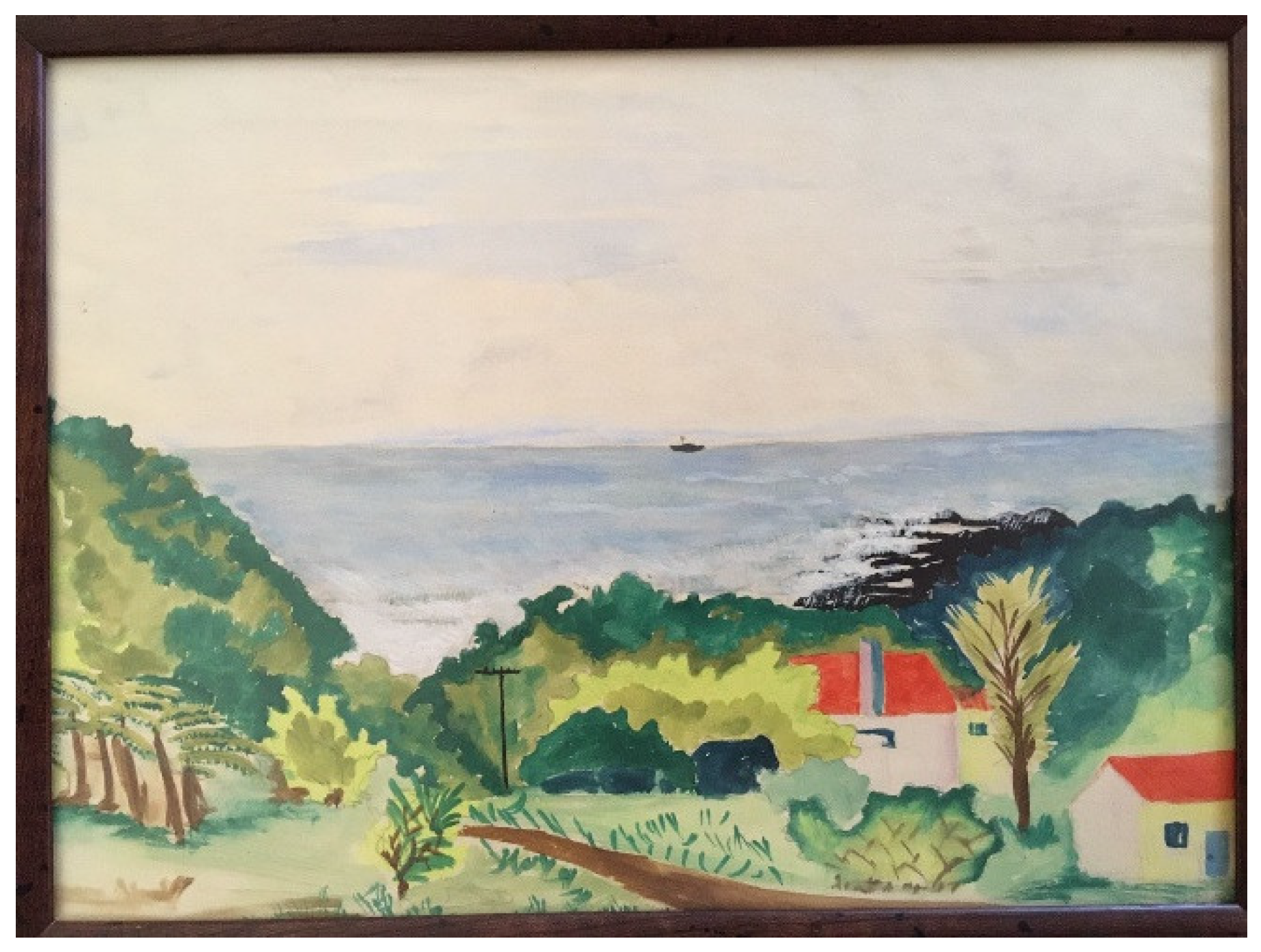

Henry got divorced at that time and after that managed to live independently in a flat. From around 2007 I became more involved in his life again. He was lonely, and as he was very creative, I bought him paint, brushes, and some canvasses.

He started painting again, and his images were all about nature. I thought that the themes of his paintings brought him peace and tranquillity (

Figure 4).

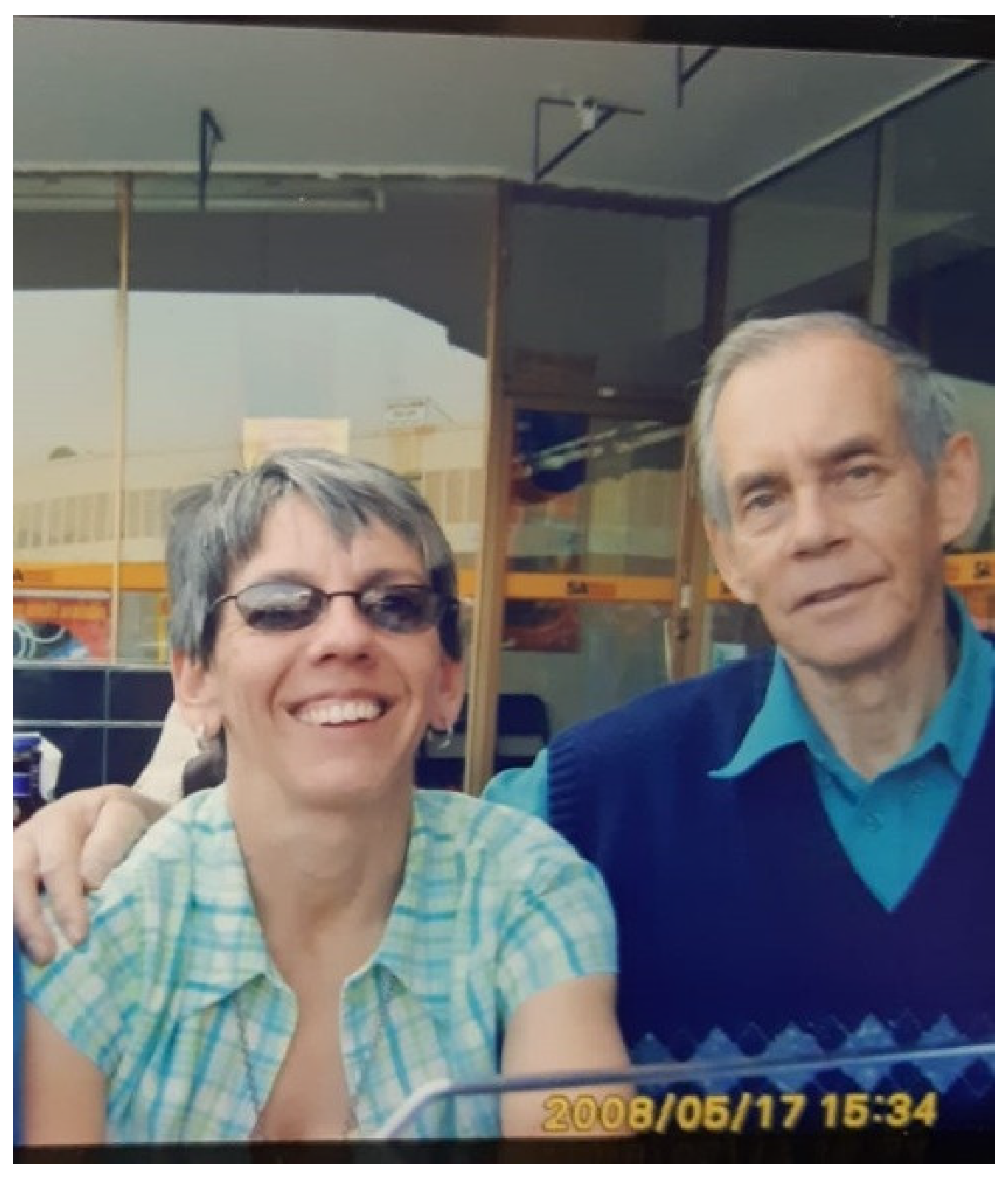

Although we were living on opposite sides of the country, I visited him as often as I could. We took long walks and shared ice-creams and lunches.

Figure 5 is an example of one of our walks to an ice-cream shop and just enjoying each other’s company.

We also made music together and he became the main inspiration for me to continue my studies. I qualified as a music therapist in 2013 and the same year we celebrated his 65th birthday. One year later, on my sister’s 65th birthday, Henry and I had a long conversation about him continuing his studies (

Figure 6). It was another significant moment in our relationship, as now I felt that he was treating me as an adult, an equal, and not his little sister anymore. He shared a deep disappointment with me.

He wanted to pursue a new career in theology and was disappointed at having been turned down, firstly because of his age, but also because of his diagnosis. I tried to convince him that he could feel fulfilled by writing articles, or a book, or some music. Little did I know then that this conversation would lead to Henry composing his “Six Sandglass Youth Songs”. I decided to enrol for a MA degree in Positive Psychology and I completed my studies in 2018, and Henry published his book of songs (

Figure 7). My focus was on the exploration of Guided Imagery and Music as a well-being intervention, and Henry described his motivation for writing the songs as the impact of shortcomings in worship dogma.

Henry was diagnosed with a brain tumour in February 2017 and three operations followed. I made every effort to visit him in the hospital each time (

Figure 8). We sang together. We were reminded of the Dutch songs that our mother used to sing to us. It was possible to lift the heavy spirit of being sick through music, laughing, and praying together and there was also an opportunity for me to connect with his sons around his bed (

Figure 9). Each time the doctors claimed success, but every time the tumour grew back rapidly. He had 41 radiation sessions between February and June 2018.

We gathered as a family for his 70th birthday in November 2018 and on this occasion, he gave me and each of my sisters a precious bracelet (

Figure 10). The inscription is from Scripture: Philippians 4:13 I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me. This gesture of giving presents to your siblings on your birthday stayed with me. Also, the significance of the gift. It was simple and inexpensive, yet the message that it carried, that we were believers and that our faith in God was still binding us together, felt important. I believe it was yet another way for Henry to try and fulfil the role of my absent father, being the carer. He wanted to make sure that we would be fine without him. I believe also wanted us to know that he was fine.

On the day of his birthday celebrations, he was still playing the old family pump organ at his home (

Figure 11). He played The Little Drummer Boy with the melody in the left hand, and I can recall the squeaking pedals as he was pumping away. Although it was such a simple tune, the playing gave him so much pleasure and is one of my fondest memories. I wondered in hindsight whether he chose this specific song because of its simple message. Did he relate to the poor boy? Or the fact that God expects nothing of us except our faith?

On that day, we did not know that it would be the last time that all the siblings would be together. We spent time around a good meal and took a lot of photos. I recall how I asked my brothers to gather around me with my selfie stick (

Figure 12). These memories will be treasured as part of my life journey.

The last operation was performed May in 2020. This was in the depth of the pandemic, yet the surgery was unavoidable as my brother’s health was deteriorating fast. He was in ICU for 30 days, and he passed away on 4 June 2020. Although we could not visit him, his son had him listen to all our voice messages and prayers for him. He did not react, but I believe that he could hear and understand. I thought back to his birthday and the bracelets. Could it have been that he knew it might be one of his last gifts to us? The inscription on each bracelet could also have been a message from him. Did he hope that we would stay faithful and trust in God?

At his funeral, which was postponed for weeks due to the pandemic, I chose to throw seven spades full of ground into the grave (

Figure 13). One spade for each sibling, but also to remember the symbolism of seven being the perfect number according to Scripture.

3.2. Fracturing and Connecting: Personal Notes during MI Training

Music, because of its specific and far-reaching metaphorical powers, can name the unnameable and communicate the unknowable.

Leonard Bernstein

3.2.1. Day 1

MI is a therapeutic method where music and imagery are used together to give insight into a specific problem/issue. The MI method was developed by Lisa Summer who was also our trainer. MI therapy is part of a continuum model where the first step is to support clients who need help in finding and developing their internal resources (

Summer 2002), or personal strengths, such as patience, gratitude, leadership, etc. (

Peterson and Seligman 2004). In turn, these resources can be applied in the re-educating of the client around their problem or issue. Lastly, it can lead to transformation for the client (

Summer 2015).

In an MI session, the problem or issue is established first between the therapist and the client. Then a piece of meaningful and suitable music is collaboratively selected. It should be music that suits the issue, for example, if the client needs to improve patience, the music must have qualities that will enhance patience. The client then draws a picture while listening to the chosen music. The music is repeated until the image is completed, after which the process is discussed (

Scott-Moncrieff et al. 2020).

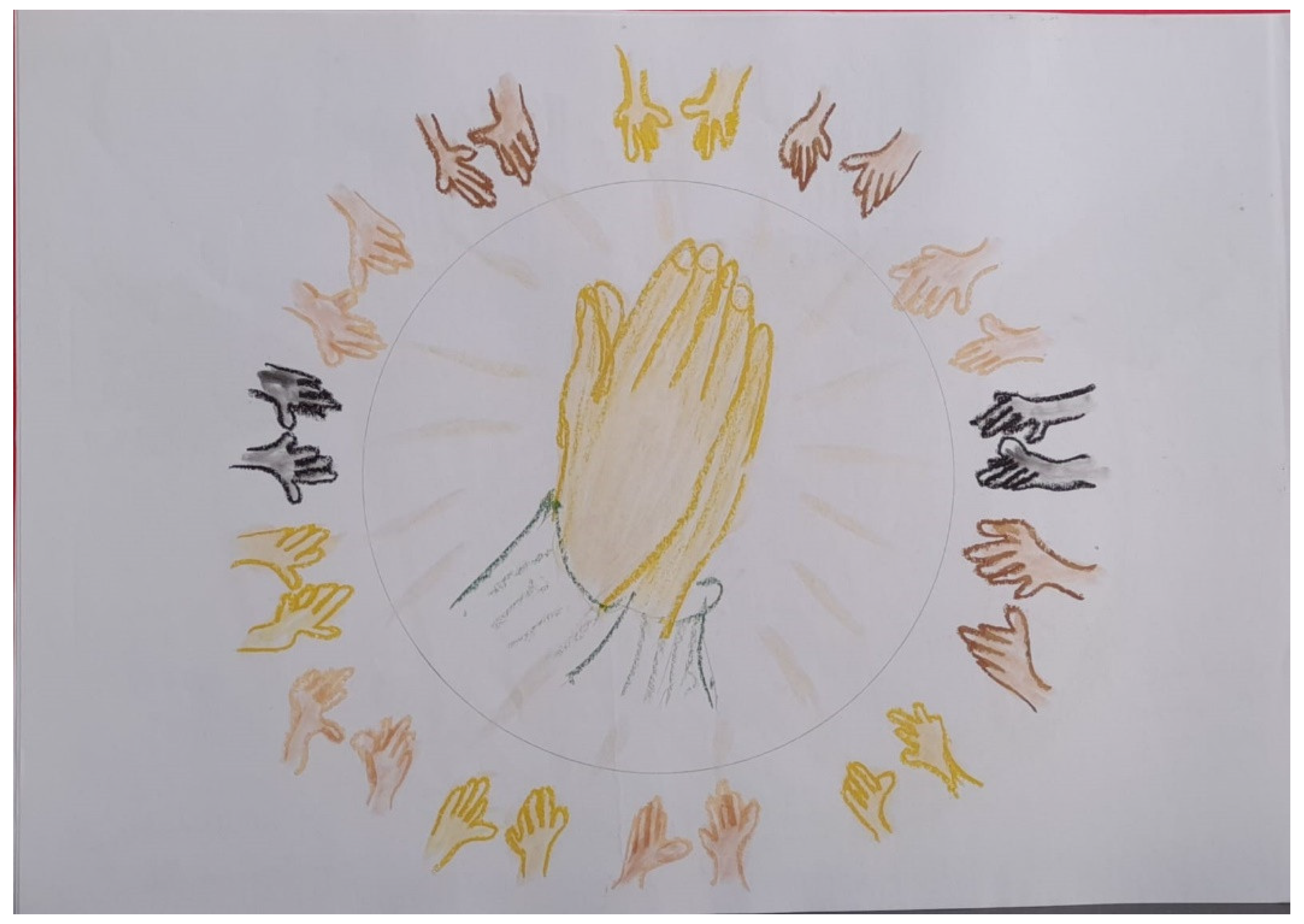

As an introduction to our course, we were asked how we all were. I had to share that my brother was in ICU and that I was preoccupied with the fact that I could not visit him because of COVID-19 restrictions. Also, the fact that Henry was unexpectedly deteriorating was worrying. Being in the group of MI students and facilitators reassured me that I was not completely alone. I was surrounded by people who cared and understood. Their presence and the music connected me with an amazing tenderness. The hands I drew represent both giving and receiving support. I labelled this mandala: trusting in that balance.

The content of the first learning session included the following:

One of my colleagues said something that resonated with me: You are in pain because you are alive. Since this was coming from an observing friend, I realised that this was a common truth and that there are many others out there also feeling pain. At the same time, it gave me hope, as I was certainly alive.

3.2.2. Day 2

On our second day of the course, we were given practical examples of how to engage in a full MI session where re-educative work needed to be done. The pre-talk (establishing the issue), transition (choosing of music), induction (preparing the client for the listening), and active listening and drawing were demonstrated after which we had to practise this after being asked to:

Be open, be curious

Accept whatever the music brings

Challenge yourself to be genuinely authentic

Don’t try to solve

Try to see whatever is there clearer

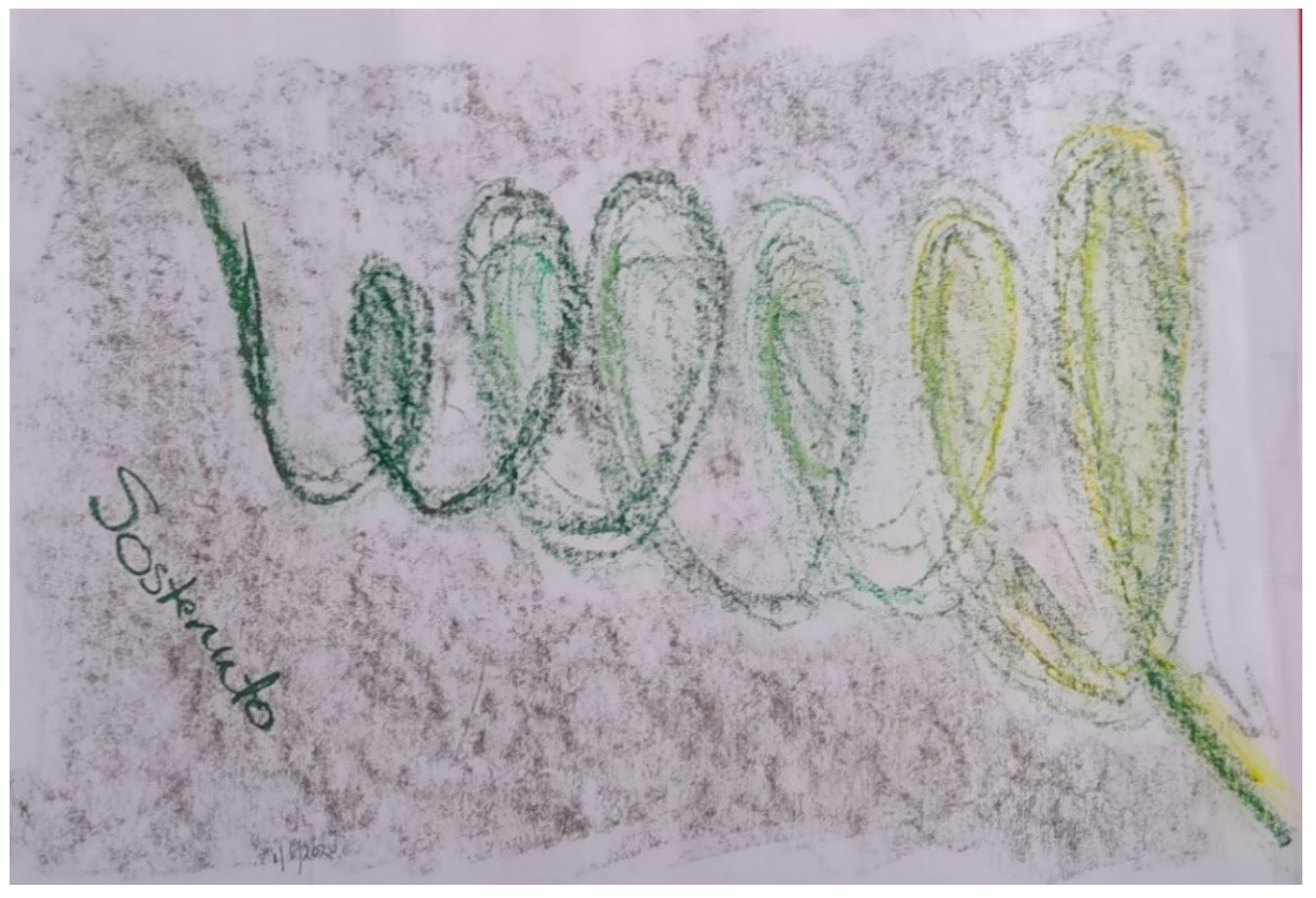

Reflecting on the process of making this drawing (

Figure 15) while listening to the music, these were my thoughts: I feel a little stuck but there is some acceptance about the universality of it. It is not only me feeling this, but everybody is stuck in COVID-19. Also, there is a sense of letting go of the tension that the music and the circumstances have provoked. Yet, it’s not gone; it’s not fixed; it’s not solved; it is there; it is real and it is even growing! I called this picture: Sostenuto.

1 3.2.3. Day 3

In our first dyad, where two students worked together as client and therapist, my focus as a client was on the need to allow myself to be vulnerable and to grieve. I grew up in a social culture of always being grateful and not giving in to more challenging emotions such as sadness. In the Christian faith, this is linked to the message found in 1 Thessalonians 5:16–18: “Always be joyful. Always keep on praying. No matter what happens, always be thankful, for this is God’s will for you who belong to Christ Jesus” (

The Living Bible 1971, p. 188). I realised that I felt frustrated because honest emotions were ‘not allowed’, ever. I remembered a similar feeling when my father died. We had to be grateful because his suffering had ended and were not allowed to cry for our loss. I realised how warped this belief was. Yet, Scripture tells us that even Jesus cried for the loss of His friend (John 11:35,

The Living Bible 1971, p. 91)! I might have understood it incorrectly, but now, I felt at last, that I had the opportunity to dig into these two conflicting concepts: on the one hand, feeling vulnerable and on the other hand needing to be strong and grateful. I thus chose a concerto, as it is a dialogue between an instrument (lonely and “vulnerable”) and an orchestra (strong). The music I chose was

Boccherini’s (

[1770] 2017) Cello concerto in B-Flat Major: Adagio. We listened to the recording by Jacqueline du Pré from the album

The Heart of the Cello. (

https://open.spotify.com/track/5lWrKno3WGaPLg8hwGuzQ0?si=db5e4d02f9504a46, accessed on 3 June 2020).

In the concerto the long melodic lines, predictable, stable, cello solo, and the string orchestra supporting it with a clear metre throughout kept me safe. Although there is no piano in the music I selected, I started by drawing a piano as it is the first instrument that both my brother and I learned to play as young children. But then I felt that I had to let out some of my frustration in terms of feeling sad for him. Hence I drew the black triangles. In the end, even this feeling was quite contained, therefore I added the green half-circle with some new growth. I labelled this picture: Comfortable with the uncomfortable (

Figure 16).

This realisation was, contrary to what I expected, quite strengthening and it gave me hope amidst feeling confused about my own emotions. For me, this picture meant being more genuine about my real feelings.

One of the main purposes of MI is to use music that matches closely the feeling associated with the ‘issue’. One needs to demand the emotional honesty of oneself and wait with an attitude of expectancy; a state of total receptivity. It is more important to discover that it feels great letting go of control in favour of finding a solution: Give oneself over to the music to get closer to oneself. I could get back into myself with great relief, understanding emotions, also repressed feelings, and expressing them on paper. This meant that nothing had changed, except that when I reflected on the experience, it felt much softer or kinder. It is lighter because there was a discharge of something negative. There is a new openness within you that can be filled with something positive. The difficult issue feels less overwhelming and is more tolerable. I started to enjoy accepting my inner complexity without trying to simplify it. This is in line with the concept that

Romanyshyn (

2021) describes as “(r)e-search with soul in mind, re-search that proceeds in-depth and from the depth, is about finding what has been lost, forgotten, neglected, marginalized, or otherwise left behind” (p. 13). In this way, we get to know ourselves and can realise who we are in our life worlds.

Through interacting with the group and facilitators, I learnt that it was important to find the tension within myself. One must own it, name it, and stay with it. One must move through the difficulty to integrate it into one’s wider experience.

3.2.4. Day 4

My brother died on this day.

Therapy is about illuminating struggle. The support of my study group was exceptional. They took a minute to send me personal messages on Zoom: This is what I got from them:

I’m sending you so much love and support. I hope you can feel it.

Sending love! It means so much that you are here today with us. Thank you, I’m here for you always.

I’m sending you my wishes to go through this time and appreciate you are here today.

I am sending you my love and my feeling of being there for you, very close! You know that my dear!

It is good that you are here.

I’m sorry for your loss. Sending you love and support to hold you through this challenging time so amazed at your strength to be here with us today. Thank you for your presence and courage.

I felt your pain in my heart so deeply! I can feel your brother is with my twin brother and my sister. I love you!

In my session on that day, I chose the original Joshua Bell version of Anna’s theme from the soundtrack of the motion picture

The Red Violin. The composer is

John Corigliano (

1998). This choice helped me to own and accept my sadness because of the loss of my brother. I felt so alone and this is clear in the image (

Figure 17). I realised that I need to take responsibility for my feelings and not try and negate them. (

https://open.spotify.com/track/275rJuuD6y2ogk5HDGDjp3?si=0c9dd83d91304849, accessed on 4 June 2020).

I gained deep insight into my sadness. The fact was that I felt so isolated. The music conveyed this sense of being isolated and it felt like an allowance to grieve. The music was like a hand on my shoulder. I can compare this feeling of the music being there for me with

Gabrielsson’s (

2011) description of being “embraced by the music” (p. 100). The music helped me being alone by accompanying me.

Gabrielsson (

2011) also speaks about “identifying with the music” (p. 102). In this case, I felt like the music was identifying with me.

Bonny (

2010), the inspiration behind the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (BMGIM) explained how she wanted clients to have emotional experiences while listening to music which would bring healing. This is what I encountered.

3.2.5. Day 5

This was the last day of doing course work and I cannot say that I was not relieved. There was so much support for me and an insight into my grief, but I felt that I now needed time on my own. Although our last exercise was a group drawing, each participant selected their music. I chose

Bottesini’s (

[1870] 2020) Elegy in D major No. 1 for double bass and piano, played by Robert Oppelt, recorded in 2020. (

https://open.spotify.com/track/1ytPiOSoKrKYcWOM7830iO?si=74a6165d3da94c7a, accessed on 5 June 2020).

There is something very sad and melancholy about this music. The form is predictable and safe. Yet there is some movement in the melody line which helps the listener not to get stuck. I felt similar in the drawing process to when I drew the ’Sostenuto’ picture (Day 2). However, I wanted to use colours to represent the awesome people who were with me in my isolated pain over the past few days. I labelled this image: Left up in the air because this was exactly how I felt at that moment (

Figure 18).

These mixed emotions of feeling isolated and left up in the air, yet safe and surrounded by people who cared, made me realise how clients who come for therapy might feel. The need to feel heard and to experience empathy. This is a universal need, as

Edwards (

2010) claims that, although we are individuals, being human also means that we are subjective and social beings.

3.3. Zooming In and Zooming Out

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.

Albert Einstein

As part of qualifying as an MI therapist, one is expected to do a lot of personal MI sessions. Many of these sessions are supervised. These sessions were particularly helpful in my grieving process.

The advanced level of MI therapy is also called re-educative MI. The purpose of re-educative MI is to gain insight into, and a new perspective on, an existing internal issue such as anger, anxiety, guilt, or sadness. The purpose is not to ‘fix’ the matter, but to better understand or to deal with something that had previously been too overwhelming, and ultimately to become more honest about it personally on an emotional level (

Scott-Moncrieff et al. 2020).

During this difficult time for me, personal MI sessions had a significant impact on my emotions and functioning. I called two of these sessions “Deep pain”, as I struggled to accept the fact that I could not say goodbye to Henry. The mere thought that I did not know whether he knew we cared and would have wanted to be near him was extremely painful. I needed at least two sessions to process these feelings.

It was difficult to find the right music. I realised that this feeling had very deep, almost primordial, roots, which led me to look for mythical or archetypal symbols and sounds. Finding images, symbols, myths, and stories that can open the heart, is part of the role of art, literature, and depth psychology (

Paris 2016). According to

Jung (

[1959] 1991), archetypes represent the real roots of our consciousness. They are the links with our past. It would seem to me that the trauma played quite a part here, and I was trying, subconsciously, to protect myself.

Kalsched (

1996) talks about archetypal defences: “The psyche seemed to be making use of ‘historical layers’ of the unconscious to give form to otherwise unbearable suffering” (p. 77).

In this song, her voice has an almost moaning quality, yet an empathetic ‘I feel with you, I feel for you’ is also present. The music gave me a chance to cry deeply without feeling guilty, and I felt it was okay to feel weak. In the first session, I just worked with my raw emotions and visualised the pain in my mind. I gave myself permission to cry and cry until it literally felt better.

In a follow-up session, I chose the same music, and this time, I felt that I could draw. I already had material processed in my mind, and words like ‘cold’, ‘rooted’, ‘unrefined’, and ‘honest’ stayed with me from the previous session. I felt terribly alone and was crying again. I thought of the colours blue and water. This reminded me of the snowman session (Day 4) just after I have heard the news, but these cold colours did not seem to work. The ancient feel of the music evoked an atmosphere of sitting at a fire for me (

Figure 19).

I started with the black, but soon the flames were big and bright, with sparks in the foreground, each spark starting a possible new fire. During the process, the burning fire was simulating the burning pain, and it felt like it could go on forever. Yet the small, new fires also symbolised new possibilities and different dimensions. The important message for me was that there was life! Life after death. This was a very reassuring message in the midst of my sadness.

During this time, I asked my friends who did the course with me if they would send me feedback on how they experienced my reactions after receiving the news. I analysed their feedback and coded and themed it in ATLAS.ti.23. The three themes that emerged were Empathy, Respect and the Influence of the pandemic.

Empathy, according to

Dos Santos (

2022) is an ability to regulate emotional responses which are flexible enough to move between another’s and one’s own perspectives. The importance of self-empathy is also empathised by

Dos Santos (

2022) as “it improves our capacity to be empathic towards others” (p. 8). This was clearly seen in the first theme, which included deep shock and a genuine need to support me. This was linked to understanding from those who had similar experiences. Some of the quotations in this theme include: “I remember your news and I really felt for you. I recall feeling shocked. I lost my brother suddenly and felt I had lost part of myself with his passing”; “My first feeling was one of empathy and grief for your loss. It was hard to conceive what you must have been feeling”, and “I remember you were in tears sharing the drawing you have made. It was all snow with just a few strokes. It was a freezing drawing. I remember thinking: That’s frozen pain!”. Another touching comment was “I felt a huge urgency to be with you and caring for you, supporting you, because that is what a person needs in a grieving moment”.

The second theme was about the respect many of my colleagues felt after I decided to finish the course. After the course, a substantive load of homework in the form of practising the method follows. These comments from my friends motivated me to do the personal and supervised MI sessions. One such comment was: “I do remember being amazed that you had been able to turn up for the seminar when you must have been in turmoil inside after hearing such strongly emotional news, and I knew that it would bring a very strong challenge to the dyad experience”. Another comment that meant a lot to me, and I kept going back to it was: “I was surprised that you had decided to attend the training that day. It was hard to conceive what you must have been feeling”. When reflecting on this theme of respect, I understood that it was also a significant part of my culture to always respect others. In this instance, I would never have dropped out of the course out of respect for others as well as for myself.

The third clear theme was the impact of the pandemic, and how it struck everyone harder when this news was brought into the group and the training: “I believe that the many complications during the pandemic affected my level of engagement with the training” was one of those comments that made me realise I was not alone in this difficult situation. Another comment was: “It was a first for me, to be in our group, online, with you across the other side of the world…. To witness your sudden experience of loss and grief in this way was unreal”. One of the group members reacted as follows: “I felt frustrated, and we [two group members] decided to make a video call to you to stay with you. You needed it and you deserved it”. The memory of this call stayed with me and carried me through every difficult session I had during my time of grief. I realised just how fortunate and blessed I was to have such support!

3.4. Insight, Intuition, and Impressions

Pain will leave once it has finished teaching you.

Bruce Lee

After traumatic events, many people may also experience positive psychological change, which is referred to as post-traumatic growth (

Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004). Post-traumatic growth refers to a transformational change, which can be seen in one or more of five distinct domains: first, personal strengths; second, new possibilities can be seen in a changed perception of the self; third, relating to others is different; fourth, new appreciation for life; five, spiritual growth becomes clear in a changed philosophy of life (

Calhoun and Tedeschi 2014). Although

Carson et al. (

2021) reported that post-traumatic growth was observed in very low numbers in their survey during the pandemic, this was certainly not the case with me. When I completed the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) (

Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996), significant changes were evident in the domains of personal strengths, appreciation of life, and spiritual growth.

Some of my personal MI sessions can be described as examples of transformative growth in these three areas.

Hearns (

2010) describes how their client ‘s experience in MI work was transformative and transformational when the client explained how they saw themselves differently. A client who felt that their journey was difficult and that they were stuck was described by

Angulo et al. (

2021). In this case, the music in the MI session had such a powerful effect that it ultimately led to change for the client. A sense of growth and expansion was also experienced by a client of

Paik-Maier’s (

2017).

Two of my sessions, which I will be focusing on below, were connected, with the first of the two being the catalyst for change. The transformation that I experienced during and because of these two sessions became clear.

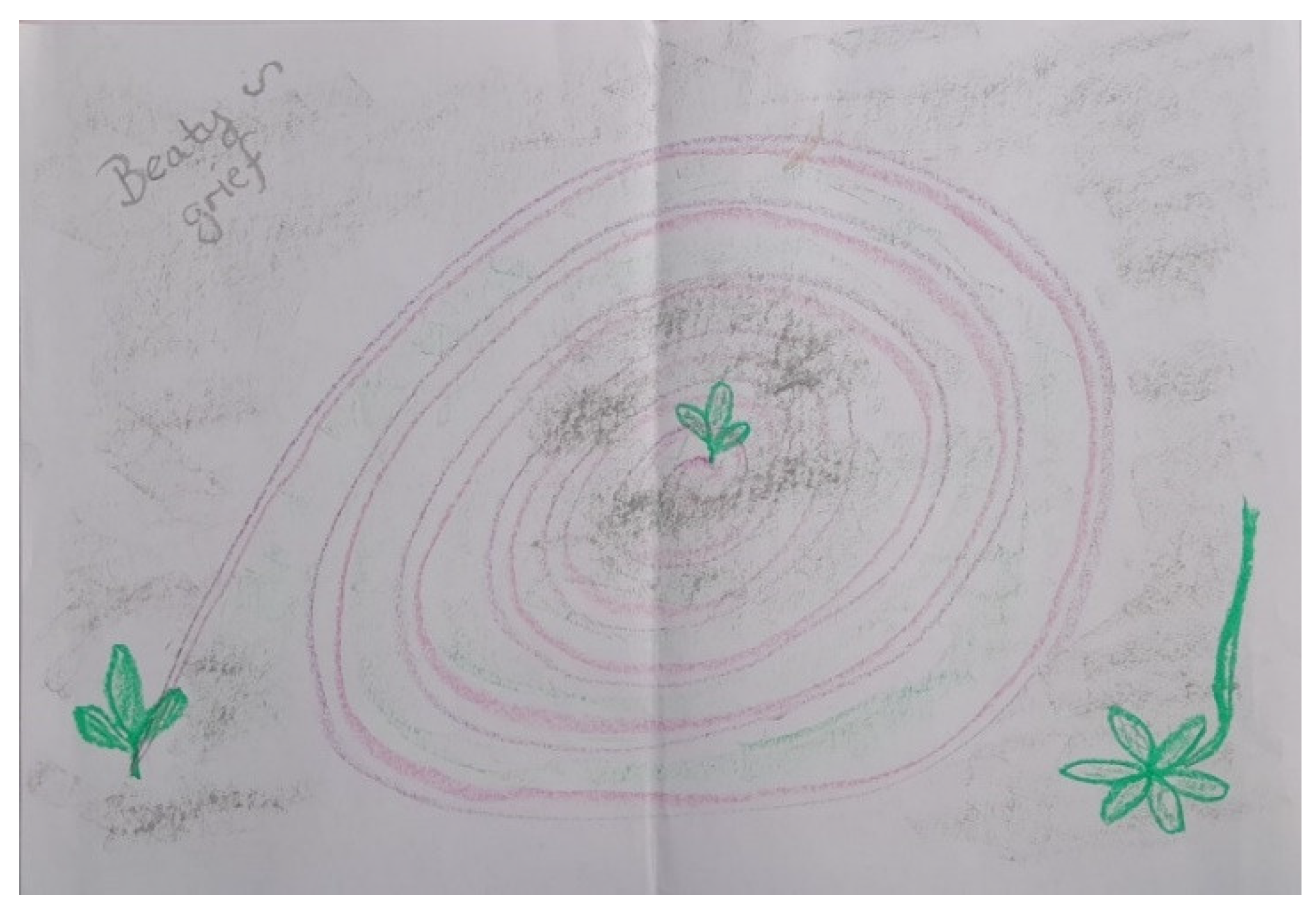

Although the tears have subsided, the sadness remained acute, and I struggled with moving forward. I felt a little bit as if I were trapped in a maze and going around in circles (

Figure 20). This feeling of ‘going round in circles’ brought to mind the song ‘The windmills of my mind’, composed by

Michel Legrand (

[1968] 2015). When I listened to the song, it also reminded me of the snowman session, as well as the session with the fire burning. (

https://open.spotify.com/track/7waSF4UCc7xkc6x87zoc2L?si=74b679271cdc4a6b, accessed on 3 July 2020).

The English lyrics of the first verse by Alan and Marilyn Bergman are as follows:

Like a circle in a spiral

Like a wheel within a wheel

Never ending or beginning

On an ever-spinning reel

Like a snowball down a mountain

Or a carnival balloon

Like a carousel that’s burning

Running rings around the moon

Although my image is a maze, with different broken lines and various branches from the core, I called it ‘labyrinth’. This shift happened during the process of listening and drawing. Similar experiences had been described by

Summer (

2011) where their client expressed how finding focus, acceptance, contentment, and hope happened while drawing during an MI session. Another example is

Liu’s (

2021) client describing the process as if they were taken on an adventure. A labyrinth is a continuous path which leads to the centre, as long as there is forward movement. The autumn leaves to the left turning green on the right-hand side of the image is another sign of subconscious movement. This was a direct precursor for the next session when I used

Nils Frahm’s (

2021) music ‘Because this must be’ from the album

Graz. (

https://open.spotify.com/track/4CJUL27qGiX5MfHFcFpr38?si=d8a3652fec784cd1, accessed on 20 July 2020).

The music also goes ‘in circles’, but there is an atmosphere of empathy and a soothing quality to it. It was perfect for my ‘real’ labyrinth, and my motions during the listening and drawing process changed from the turmoil of a whirlwind to acceptance (

Figure 21). I started to understand the real symbolic meaning of entering and exiting a labyrinth: taking whatever felt heavy and unbearable to the centre, and leaving it there to return without it, feeling lighter and accepting what cannot be changed. Labyrinths are ancient symbols, which want to lead from the visible to an invisible or divine dimension. The ultimate goal is to reach the centre, which will make the way back lighter and completely new (

Ronnberg and Martin 2010). A labyrinth takes up as little as possible space with as long and difficult as possible a path. This complicated path is symbolic of the difficulty of the journey towards the centre or end goal (

Chevalier and Gheerbrant 1996).

I experienced a deep sense of gratitude and appreciation of life during this session. Gratitude for life was also an experience described by various clients, especially after the realisation of the impact of COVID-19, by various clients during MI in a study by

Jerling (

2023). My personal strength was recognised not only by myself but also by people close to me including my supervisor: “I was struck by the thought of how well-resourced you must be”.

These personal MI sessions and the way in which I experienced the music and my own emotions, led me to realise that I have grown on a spiritual level as well. Spiritual experiences during MI sessions were noted by

Paik-Maier (

2017) when the client expressed their awareness of God’s presence, as well as

Creagh and Dimiceli-Mitran (

2018) who’s client experienced themselves as being clothed in shimmering attire by a beautiful figure during the music listening. My relationship with God has deepened as I was accepting the loss of my brother and realising that there was so much hope for a future, even after my life on earth. I noticed this already in the session which I labelled ‘Pain burning like fire’ (

Figure 19) when I discovered that, for me at least, there was life after death. This realisation came almost as a surprise to me since I have been holding on to that inner conflict that I experienced and explored on day 3 of our course. How could God expect us to ALWAYS be joyful and grateful, even when we are feeling so much pain? In spite of this conundrum, I now realised that “the myth of redemption is so ingrained in our collective psyche” (

Paris 2016, p. 150) that I want to be perfect too. Through this journey of loss and finding peace, I finally realised that God does not expect me to be perfect. He only expects me to keep growing: Romans 12:2 “Be a new and different person with a fresh newness in all you do and think” (

The Living Bible 1971, p. 141).

My transformation became clear when I was preparing for a session using MI as a method to explore ‘the hero within oneself’ with a group of clients who are all suffering from PTSD.

The introduction to this music created a pulling feeling within me, and when the piano started, it felt as if I could fly. After one minute the music changed and it was clear to me that there was a struggle, but this was resolved, again taking me higher and higher. I was soaring. Similarly, during Mi sessions,

Meadow’s (

2015) client described their body as flowing; a sense of release was described by a client of

Dimiceli-Mitran’s (

2020). There is a lightness in the second half of the music, which I drew in the sun. The music, for me, portrayed the cycle of life with its ups and downs, but my faith helped me to realise that the journey is worth all these ups and downs, as it ends well.

Gabrielsson (

2011) describes people’s “visions of heaven, paradise (and) eternity” (p. 191), “spiritual peace, (a) holy atmosphere and Christian community” (p. 194), “music that conveys a religious message and contact with divinity” (p. 196) and even “meeting the divine, God” (p. 201), all while experiencing music.