2. Social Media, Cinema, and Education

The use of cinema to educate audiences, in general and in varied disciplines, is established in the existing literature. Based on data collected through an online survey and a social media discussion forum,

McCann and Huntley-Moore (

2016, p. 37) found that cinema could play a role in the teaching of mental health issues among nursing students noting that popular cinema is increasingly being used in health professional education as “part of a trend to introduce the humanities subjects into the science-based curriculum”. Similarly,

Higgins and Dermer (

2001) found that film has been used in education in the discipline of psychology, while

Sunikka-Blank et al. (

2020) demonstrated how cinema has played a role in informing audiences on specific topics. To contextualise this study, this section of the paper outlines the intersection of social media, the educative role played by cinema, and religious or societal issues. Drawing on Deleuze’s work,

De Freitas (

2016) urged moving beyond existing cinematic conventions “to map new ontologies of the social and engage with the radical thought of the time-image” (p. 568). The work of

Pacheco (

2016), looking at film in the lives of children and young people in Brazil and Portugal, assessed the purpose of the “audiovisual document” (

Pacheco 2016, p. 2) as a form of production and evaluated the importance of cinema in reflecting the lives of and educating young people. Scholars like

Clarembeaux (

2010) stressed the importance of film to encourage discussions of societal issues. An analysis of three Malay films by

Driskell (

2019) found that cinema traced the evolution of celebrity and its desirability, in the context of the shifting religious norms and increasing Islamification of Malay society.

Several long-form articles explore concepts related to the pedagogic role played by cinema and social media. While these are not academic studies, these articles help to lay out the existing work in terms of explorations of the topic of this paper.

Kumar (

2018) unpacked the notion of using storytelling to emotionally connect with audiences. Drawing on psychological and marketing frameworks, they discussed the elements of an engaging story, finding that character, drama, and resolution are key aspects of successfully selling the message or messages in content creation.

Elezaj (

2020) also looked at engaging audiences through storytelling and explained that the human mind works better with concepts that are told in the form of a story. This study is predicated on the assumption that stories have an emotional appeal, which motivates audiences to connect with narratives presented in communication forms. Today, social media is a popular media form for storytelling in both social settings or personal use and corporate use (to promote brands, for example).

Darker aspects of the use of cinema beyond education lie in the incorporation of film in state or religious propaganda. Drawing on the work of Anderson on imagined communities and the role of the media in forming national identity,

Rajgopal (

2011) found intersections of nationalistic themes and communal violence in sub-continent cinema. Similarly, the work of

Lahiri-Roy (

2010) on Bollywood as propaganda found that films can be used for the purposes of reiterating patriarchal hegemony as they reflect the slowly changing cultural mores of urban middle-class Indian society.

Like cinema, social media has emerged as a communication form that can be used for the purpose of educating and portraying religion, religious practices, and religious themes despite reservations from media scholars such as

Jakubowicz (

2017) about trolling, misinformation, and other potential negative behaviours stemming from these platforms.

Vasudevan (

2015) found that cinema—especially social film—played a role in pre-partition India (1935–1945) in the dissemination of narratives about the Hindu majority and Muslim minority in the sub-continent. Religious and social issues and their impact on society are portrayed through cinema as a way of provoking thought and analysing concepts (

Read and Goodenough 2005). For instance, the Spanish Episcopal Conference’s use of social media reflected “one of the fundamental tasks of any religion” in “the systematic spread of …beliefs, values, and practices” according to

Baraybar-Fernández et al. (

2020). The work of

Ibrahim (

2020) on Sharia implementation and (visual) media discourses suggests that among the Muslim communities of Nigeria, “short films circulated through YouTube and social media” allow audiences to engage more with cultural and faith-based narratives compared to traditional forms of religious knowledge production such as in-person sermons. Similarly,

Cornet (

2021) analysed Islamist-produced popular culture in Egypt, finding that cinema was produced by a youth group specifically for social media consumption and with the aim of claiming “an Islamic space in Egyptian popular culture” (

Cornet 2021, p. 60).

Despite many examples of the use of social media and cinema in educational contexts, these communication forms are not viewed as a formal source of knowledge; the art of cinema is still considered primarily fun and entertaining and not educational or analytical.

“Even though it’s valued, cinema is not yet seen by educational media as a source of knowledge. We know that art is knowledge, but we have trouble recognizing cinema as art (with variable quality production, like all other forms of art), because we are imbued with the idea that cinema is fun and entertaining, especially when compared with the arts considered ‘noble’.”

However, as examples in the literature suggest, both social media and cinema can be used to inform through the exploration of religion and religious themes. As argued by Kaplún (in

Pacheco and Juliana 2019, p. 246) “communication and education must serve a transformative educational process, in which the addressed subjects critically understand their reality and acquire tools to transform it.” Given the existing work that has been conducted in this area, this paper stands out in that little attention has been paid to the potential for cinema and film to be used in educating audiences about religious and societal themes and concepts, through employing a practice-based approach relevant to the media discipline. Therefore, this research asks the following questions:

How might cinema play a role in informing movie audiences about religion and society?

Can this role be played using media practice (in the form of a resource the researcher developed as an IMDB-type social media channel)?

The concepts and ideologies explored in this paper through the construction of a social-media-based movie database show that religious and societal issues in movies can be an important aspect of the lives of millions in the cinema-going audience.

3. Research Design

This study straddles the disciplines of journalism or communication and art, based on the assumption that even in mainstream global movies made primarily for the purpose of entertainment and profit, there are concepts that have gone unidentified and can be used to inform and communicate. For instance, a heist movie could also explore themes of abandonment, co-dependency, and the need for attention—for someone watching purely or primarily for the purpose of entertainment, educative concepts could be ignored but for someone watching from a philosophical point, educative concepts can be grasped. Art is based upon ‘an appearance incapable of appearing’ (

Lefebvre 1991, p. 395). Research into cinema, therefore, requires the incorporation of multidisciplinary core concepts that can be adapted and molded into a thematic analysis of how specific themes in the chosen data set of films are presented.

Dallow (

2003, p. 51) proposes three types of research approaches for art—“research into arts practice, research through arts practice, and research for arts practice”. Research into the arts involves not only theory and criticism but also aesthetic and cultural perspectives. Research through art is the process of the production and presentation of the framework. Research for arts practice covers the finished outlook and customisation of software and hardware in the culmination of the arc of the process. This study incorporates the second approach (research into arts practice) with a practice-based methodology from journalism to explore the educative role of movies; in the journalism practice methodology, a creative artefact appropriate to the discipline is produced (in this instance, a social-media-based curated collection of movie reviews) whose contribution to knowledge is contextualised by this study. Using a deductive approach, the researcher narrows down an initial list of films from a global selection of cinematic output that covers religious and societal themes through a range of lenses (such as characters’ well-being, trauma, religious practice, or cultural values).

Bell (

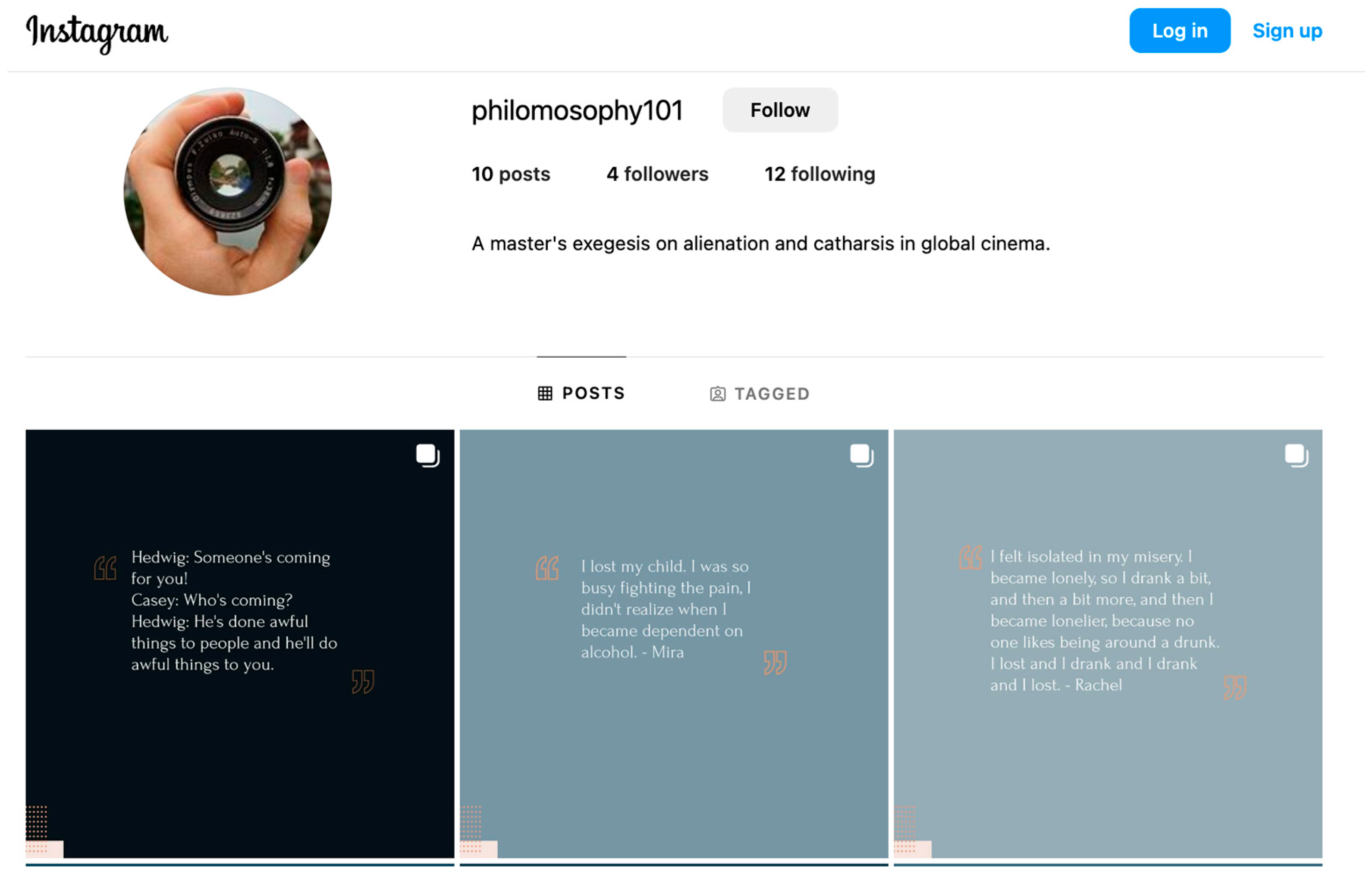

2006) stresses the importance and relevance of research in the development of a film—a framework that resonates in the research design used for this paper, of a creative artefact and a contextualising research paper. The emphasis on object and subject is highlighted in relation to art and its conceptualisation. When art is made and the artist has conducted research, according to Bell, it reflects in the art, but it is not the main purpose of the art, which is to focus on creativity and for the art to remain objective and sound. As a work of research in media, we employ a practice-based research methodology often employed in the creative arts (such as visual arts, media, performing arts, and creative and professional writing). This consists of a creative artefact appropriate to the discipline (in this instance, the social-media-based collection of movie reviews—an Instagram IMDB, if you like) along with this paper which situates and justifies the creative artefact’s contribution to knowledge as a form of research; we incorporated knowledge of literature, film, and philosophy from previously published papers and books to understand the themes present in the global selection of films we explored.

The Instagram account used for the creative artefact is @philomosophy101 (

Figure 1). Instagram was selected over other platforms known to enable or facilitate trolling or disinformation; at the time of writing, Elon Musk-run Twitter was being abandoned by advertisers and users due to the removal of the company’s safety and legal teams (

Wagner 2023). Instagram settings include the prevention of user handles from being quoted by accounts that do not follow the user and other safety parameters.

The specific parameters for the films we chose as our source of data follow the sampling method employed by

Sunikka-Blank et al. (

2020) in their study of Indian movies depicting energy use within

chawls (low-quality tenement housing for factory workers in Mumbai). To narrow down their canon of films for analysis, they used a “deductive approach to film selection, identifying a suitable dataset and systematically sampling it in order to examine specific research questions, in this case understanding the energy use and domestic practices” (

Sunikka-Blank et al. 2020, p. 2). For our study, we narrowed down our initial list of films from a global selection, not wanting the dataset to be dominated by the cinema of a particular cultural industry, such as Hollywood. The films we incorporated into the creative artefact (the social media database) ended up representing several geographical movie industries including Bollywood, Hollywood, and the Middle East. All covered religious and societal themes through a range of lenses such as characters’ well-being, trauma, or cultural values; we envisioned continuing to maintain the Instagram account upon completion of this study, with examples from other cinematic cultures we have not yet explored (such as East Asian cinema).

4. Discussion

Historically, the Horse in Motion—a compilation from 1878 of several moving horse images—is credited as being the basis of stop motion animation (

Vicencio and Piccione 2020). The idea that a few images aligned together can reflect live motion made it revolutionary; the Horse in Motion and similar works were a step in the journey to expand the stream of visual art from paintings to photography to the moving image. With the multitude of movies made since The Horse in Motion, in this study, the researcher attempted to address the question of why we watch films; given that the entertainment aspect of films is established in the literature, should the educational potential of the intersection of film and social media not also be explored?

The examples of the cinema featured on the social media database, which forms the creative artefact in this study, explore several themes relevant to religion and society which have the potential to educate as well as entertain audiences to reflect on our research question (new media and cinema’s potential role in informing audiences about religion and society). The Hindi comedy film Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara directed by Zoya Akhtar exemplifies a product of global cinema that plays this role, with the portrayal of the characters exploring the impact of religious and societal values on their lives. The movie (whose title can be translated to “you only live once”) revolves around three childhood friends meeting for a bachelor road trip prior to the wedding of one of the friends, Kabir—a marriage signifying a critical milestone for the Indians of Hindu and Muslim faith represented by the characters. Kabir, Arjun, and Imran’s backstories about family, love, and self-discovery are explored as the story unfolds. Despite a falling out, Arjun and Imran come together for their friend Kabir’s pre-marriage road trip that they had been putting off for a while. During this road trip, they travel to various foreign locations and explore a variety of extreme sports, each emphasising the realisation of self against the societal and religious pressures to conform. Another work by Akhtar, Dil Dhadakne Do (Let The Heart Beat), revolves around a dysfunctional family riddled by the pressure of status and class while suppressing desires and honesty (which is what eventually brings the family together). The movie is also about an ongoing journey of life through a travel choice—this time, a cruise ship. Parents Kamal and Neelam were once madly in love, but their relationship has been engulfed by the pressure of social status and elite culture. The movie begins with son Kabir’s dream of becoming a pilot, highlighting the need to soar high and to fly away from the toxic environment in his house. Being the only son in a South Asian Muslim household, it is assumed that the audience understands the pressure Kabir is under to run his father’s family business and achieve success in its field. On the other hand, daughter Ayesha is running a successful business of her own but is married due to the pressure of her parents’ status, living with her dominant husband and his mother—circumstances that resonate with the film’s primary target audience of individuals of South Asian Muslim or Hindu faith (perhaps reminding a viewer of an aunty or relative in their lives).

Religious, cultural, and family pressures are also reflected in Sand Storm, an Israeli film directed by Elite Zexer, and Dukhtar, a Pakistani film by Afia Nathaniel. Sand Storm explores the culture of second marriages among Arab–Israelis of Islamic faith; the opening scene shows father Suliman teaching his daughter Layla to drive outside the town’s borders but once they start to return towards it, they switch places, portraying a patriarchal culture where women cannot be seen in a place of empowerment and control. Suliman has taken a new bride as he only has daughters from Jalila, which makes her quite uncomfortable in her new role as the first wife. Suliman, despite his conservative stance, is in support of the aspirations of Layla, who in turn has plans of her own. To his disappointment and Jalila’s shame, Layla is in love with a boy from her college and a different tribe. In Dukhtar, the ideology of tribal marriages for the purpose of strategic alliances is shown to be an entrenched process in the Pakistan of today. Dukhtar highlights the struggles of mother Rakhi and her 10-year-old daughter Zainab. Rakhi was married to an older man and the chief of her father’s rival tribe at a very young age to bring about a truce. In both movies, differing forms of catharsis are reached by the characters; whether audiences do so is debatable (particularly audience members unfamiliar with these films’ cultural contexts, but also audience members from Arab or Pakistani cultures with different expressions of or relationships with cultural and religious teachings).

One overriding theme that we encountered in the films was the increasing interplay between global religious communities and cultures. The documented abandonment or kidnapping of young children is not infrequent in South Asia (

Shahidullah 2017), providing the backdrop for

Lion—an Australian biographical drama set in India and Australia, exploring the journey of Saroo—a young boy from a small village in India who escapes several kidnapping attempts and is ultimately adopted by an Australian couple. After being separated from his family, he returns as an adult to find them. However, the intersection of Western and Eastern religious or cultural norms is not just a feature of the narrative within individual movies; intercultural references are evident in the adaptations of movies across national cinematic industries.

The Girl on the Train (2021) is a Hindi-language Bollywood version of

The Girl on the Train (2016), which in turn is a United States film adaptation of a 2015 British book. In the Hindi version, lawyer and divorcee Mira struggles with her mental health and substance abuse after losing her unborn child in an accident. The narrative of the earlier American version of the movie accurately reflects the plot of the book with a tormented woman, Rachel, and her abusive partner as the main characters but delves deeper into the abuse the man inflicts on both his former wife and his new partner. Both films explore self-sufficient strong women in either deeply religious or irreligious contexts (depending on the film version) being pushed towards alcoholism following loss or a toxic relationship and eventually overcoming their torment. While not explicitly about established religion, the movie

Split (a Western psychological thriller by M. Night Shyamalan) contains undercurrents of spirituality in its exploration of societal trauma (sexual abuse, abandonment, and self-harm). Shyamalan has stated that he uses film to have conversations about faith and about human beliefs in the unknown (

Alter 2017). Previous encounters with movies exploring dissociative identity disorder from Bollywood demonstrate an inconsistent history of depicting mental illness (

Singh 2017).

Split explores the disorder through its main character, who has twenty-four personalities. It intellectually explains how dissociative identity disorder is due to abuse and abandonment, where victims of abuse and abandonment find a safe space amidst themselves and find companionship with themselves. Similarly, the lens of mental instability is a concept unpacked in

Zodiac, a Hollywood historical mystery based on real-life events. The mental instability on show in this movie is that of a serial killer whose identity (off-screen) remains unknown to law enforcement, although the real-life Zodiac Killer sent encrypted letters to the media claiming that he was killing people to collect as slaves for the afterlife. Narrative closure has been postulated as an over-used aspect of the process of consuming Hollywood films as media texts (

MacDowell 2013). The portrayal of the serial killer underlines a form of detachment from secular modern society, but without a resolution, denying both the audience and law enforcement (in the movie as well as in the real world) any form of closure to the extent that even the killer’s true motivations cannot be ascertained.

The key to understanding films is to understand how human perceptions are illustrated. As time progressed, the monochromatic reel was made visually appealing by adding colours to it, as concepts around cololurs made a larger impact on the mind-set of the viewers, and as colours made an impact, filmmakers started experimenting with varied genres. The catalogue of films that formed this study’s creative artefact suggests that there are various reasons as to why audiences watch a movie including socialization, relaxation, or spending time without pressure to achieve an outcome. In the fast-paced life of the twenty-first century, two hours of exploration of religious and societal themes through global narratives can form the basis of intellectual exploration of such themes. Researchers have noted visual media’s potential to empower audiences with cross-cultural sensitivities (

Hedberg and Brown 2010). Movies assessed in the creative artefact that forms part of this study are examples of films that can be used to understand the complexity of human experiences.

Film is a form of communication that is widely available and popular. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted self-education—a process in which cinema can play an essential part. Visual communication has become critical in a social media-saturated world; the production of films predicated on educative narratives about religious or societal concepts allows audiences to benefit from a more evolved and nuanced understanding of the world.

5. Conclusions

Can cinema play a role in informing society through explorations of religious and societal issues? This study used a practice-based journalism methodology to explore how movies educate audiences about religion and society through various lenses including those such as characters’ well-being, trauma, religious practice, or cultural values. Through a social media movie database, this research has explored the subliminal educative effect of movies’ findings, for instance, that Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara can teach an important lesson that life is too short to leave passions for tomorrow, and instead, people should ‘seize the day’ and live without regrets. The movie Dil Dhadakne Do can impart insights about how, emotional distance in a family aside, a tiny flame of trust and bonding can be fanned to bring family members together. The Pakistani film Dukhtar is another key example of the informative role played by movies with regard to religious or societal concepts. The viewer is brought face-to-face with the horrific reality of child marriage, which may be a religiously sanctioned norm and a neglected issue in ‘foreign’ parts of the world, but due to awareness of this crime (through cinema), policymakers internationally have taken a stand, emphasising that women are not the property of men and that daughters are to be cherished and loved and not sold off for land and stature. The struggle portrayed in Dukhtar reflects the struggle of many young girls in South Asian tribal areas, so the potential for such movies to educate and spread awareness is very real. Similar faith-based struggles are seen in Sand Storm, which explores the culture of second marriages among Arab–Israelis of Islamic faith. Religious and societal concepts are also explored in the Australian movie Lion through the adaptation of a real story, giving audiences the chance to connect with the narrative even if that connection (imagining a life away from family and home) is scarring. The story of Lion, however, is the story of many—especially and including those living on the streets of cities in India and Pakistan. Not every child is as lucky as the titular character to get adopted and have a chance at a better life. Away from the Middle East and the subcontinent (and their diasporic communities), Hollywood films like Split or Zodiac educate and inform audiences about mental trauma through their characters with undercurrents of spirituality (or lack of it) running throughout these films. These are just some examples of how cinema informs society about religious and societal issues and trends instead of merely entertaining audiences, with the creative artefact which is a part of this research project (@philomosophy101 on Instagram) going into greater detail about these movies. The concepts and ideologies explored in this paper through the construction of a social-media-based movie database show that religious and societal themes explored in cinema can be an important aspect of the lives of millions in the cinema-going audience.