The Influence of Wartime Turmoil on Buddhist Monasteries and Monks in the Jiangnan Region during the Yuan-Ming Transition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Flourishing Buddhist Landscape of Yuan Dynasty Jiangnan

2.1. Temples, Society, and Patronage: Socio-Economic Growth and Scholarly Influence in Jiangnan

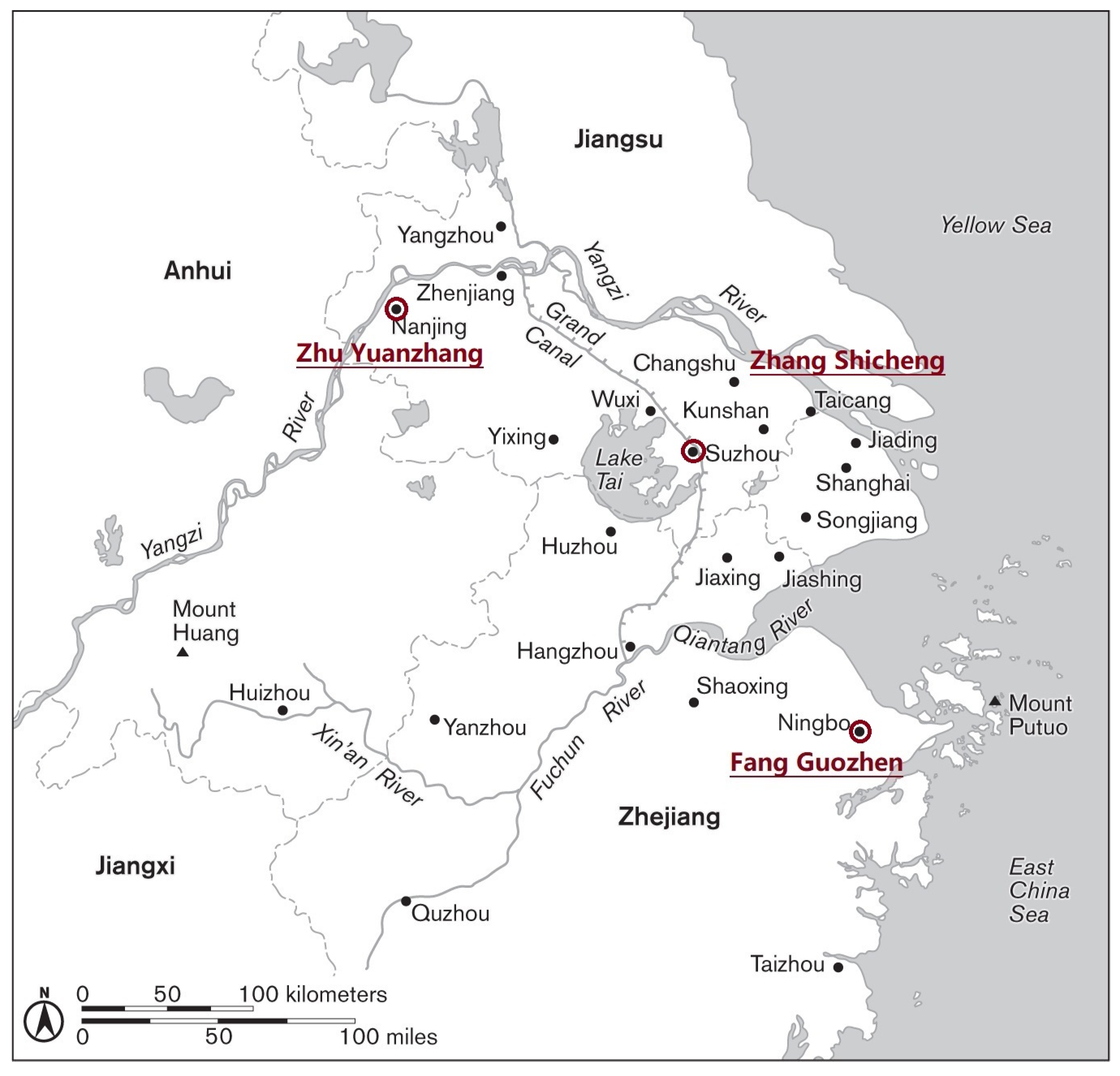

2.2. Hierarchy and Influence: The ”Five Mountains” System and Longxiang Temple in the Yuan Dynasty

3. Temples as Sites of Conflict: Vulnerability and Military Occupation

3.1. Wartime Devastation of Temples

3.2. Temples as Garrisons and Landmarks

4. Exile and Experiences of Monks in Times of Turmoil

4.1. Resolute Amid Chaos: Monastic Fearlessness and the Zen Buddhism Legacy in Jiangnan

4.2. Monastic Repatriation and the Disruption of East Asian Buddhist Exchanges

The Yuan Dynasty was plunged into widespread turmoil, with the entire nation facing challenges from all directions, leading to a state of unrest. Temples such as Jingshan, Lingyin, Jingci, and Tiantong were left deserted, their seats vacant, and many monks had their alms bowls taken by marauding enemies. To evade the tumult of war, my master resolved to journey back to our homeland, accompanied by esteemed monks like Ginan Bodhisattva and Canbiyan. Embarking from Ningbo, they sailed towards the city of Mount Cheng in Hakata. (Sho 2013, p. 140) 太元兵亂大起, 四海不安。徑山、靈隱、淨慈、天童等皆虛席, 無安單地, 多為賊曹奪衣盂去。師避兵欲歸本朝, 相隨義南菩薩、璨碧岩等諸耆宿。舶發明到博多之城山。

4.3. Reflections on Buddhist Devastation during War: Ideological Insight on Chaotic Circumstances

5. Military Warlords’ Protection and Coercion of Eminent Monks

5.1. Guardianship and Cultural Nexus: Temples in Ningbo

5.2. Buddhist Patronage and Political Strategy: Longxiang Temple’s Resilience

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Merit” refers to the accumulation of good deeds, virtuous actions, and positive karma that is believed to bring about favorable circumstances, blessings, and spiritual benefits in Buddhism. It is essentially the concept of earning positive spiritual credit through one’s actions and intentions. |

| 2 | The establishment of the “Five Mountains” system by the Southern Song government can be interpreted as an official government ranking of Zen temples. This system’s core was a cluster of five prominent temples that occupied elevated positions among Zen monasteries, entitling them to various privileges. These temples enjoyed the distinction of having their abbots appointed by the government and boasted architectural grandeur surpassing that of ordinary monastic establishments. Essentially, this system introduced a secular bureaucratic approach to the administration of Buddhism. The abbots of these temples held prestigious roles, which presented a formidable temptation for even reclusive monks, given the allure of fame and status. Engaging in active competition for acknowledgment within influential circles, some monks sought to secure positions as abbots through strategic social affiliations (Ishii 1991). The term “Five Mountains” refers to the five major Buddhist temples of Jiangnan, with their abbots serving as recognized leaders of Jiangnan Buddhism under governmental auspices. |

| 3 | The first zenith had occurred after the migration of the Southern Song Dynasty, marked by the flourishing of Zen Buddhism as the political center settled and prospered in the Jiangnan region. |

| 4 | After unifying the entire country, the Hongwu Emperor implemented stringent control over Buddhist temples. He witnessed a laxity in the monastic discipline during the Yuan Dynasty, which he believed would undermine people’s reverence for Buddhism. Moreover, he observed that some monks had formed alliances with anti-Yuan forces towards the end of the Yuan Dynasty, leading him to suspect that temples could serve as sanctuaries for political opponents, potentially organizing activities against him. Consequently, he instituted a series of rigorous regulations for the management of temples (Chen 2021, pp. 423–3426). |

| 5 | Considering that the Yuan Dynasty was a unified realm, it becomes imperative to explore the influence of various Buddhist sects on Jiangnan Buddhism. The Mongols introduced Tibetan Buddhism to the Jiangnan region. Yanglian Zhenjia 楊璉真加, a disciple of Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1290–1364), played a pivotal role in propagating Tibetan Buddhism in Jiangnan, resulting in a noteworthy surge in temple construction activities (B. Zhang 1983, p. 751). This proliferation of diverse Buddhist sects significantly augmented the presence of Buddhist temples in Jiangnan, leading to a more densely distributed network of these religious institutions. Nonetheless, scholars contend that Tibetan Buddhism’s penetration into Jiangnan was chiefly propelled by political power and lacked robust social foundations, thus impeding its sustained development (Chen 2021, p. 287). In the mid-Yuan period, Zen Buddhism experienced a revival in Jiangnan, an upsurge primarily attributed to the influence of three prominent monks: Gaofeng Yuanmiao 高峰原妙 (1238–1295), Zhongfeng Mingben, and (Xiaoyin) Daxin. Among these figures, Master Daxin played a pivotal role. He maintained close ties with Emperor Wenzong and bore the honorific title of the “Leader of the Five Mountains”, symbolizing the preeminence of Jiangnan Zen Buddhism over other sects (Chen 2021, p. 309). This historical context elucidates Zhu Yuanzhang’s endeavors to secure support from Longxiang Temple. |

References

- Anonymous. 2002. 披剃僧尼給據 [Regulations for Shaving Monks and Nuns]. Yuandianzhang 33. Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2016a. Island of Guanyin—Mount Putuo and its Gazetteers. London and New York: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2016b. The General and the Bodhisattva: Commander Hou Jigao Travels to Mount Putuo. Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies (New Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies) 29: 129–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Peter Kees. 2003. The “Localist Turn” and “Local Identity” in Later Imperial China. Late Imperial China 24: 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, Timothy. 1994. Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Jian. 2004. 古心禪師半葬塔銘 [Inscription on the Half-Burial Stupa of Master Guxin]. In 全元文 Complete Works of the Yuan Dynasty. Nanjing: Phoenix Publishing House, vol. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Gaohua. 2021. 元代佛教史論 [Historical Study of Buddhism in the Yuan Dynasty]. Shanghai: Guji Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Elman, Benjamin. 2000. A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Sarah E. 2003. Merit, Opulence, and the Buddhist Network of Wealth. Shanghai: Shanghai Fine Arts Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Qi. 1985. Preface to the Poem “Sending Monk Lü on the Path to Enlightenment”. In 高青丘集 [Gao Qingqiu Collection]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Literature Publishing House, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Shulin. 1997. Yuandai Fuyi Zhidu Yanjiu. A Study of the Taxation System in Yuan China. Shijiazhuang: Hebei University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Ying. 2008. 玉山璞稿 [Yushan Pugao]. Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Chengwei. 2000. 大元通制條格 [Dayuan Tongzhitiaoge]. Beijing: Legal Press, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, Mark. 2006. Out of the Cloister: Literati Perspectives on Buddhism in Sung China, 960–1279. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, Mark. 2014. Buddhists and Southern Chinese Literati in the Mongol Era. In Modern Chinese Religion. Edited by Pierre Marsone and John Lagerwey. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe, Yukei. 1993. 明清佛教教團史研究 [Research on the History of Buddhist Sangha in the Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Kyoto: Tongpeng She. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Natasha. 2014. The Cultural Construction of the Chan Monk Zhongfeng Mingben. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jin. 2013. 黄溍集 [Huangjinji]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Literature Publishing House, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Shūdō. 1991. 中國の五山十刹制度の基礎的研究 [The Fundamental Study of China’s “Five Mountains and Ten Monasteries” System]. Komazawa University Journal of Buddhist Studies 6: 30–82. Available online: http://repo.komazawa-u.ac.jp/opac/repository/all/18971/KJ00005120564.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Kieschnick, John. 1977. The Eminent Monk: Buddhist Ideals in Medieval Chinese Hagiography. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinomiya, Yasuhiko. 1985. 中日佛教交通史 [History of Sino-Japanese Cultural Exchange]. Taipei: Huayu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Jifu. 1998. 楚石梵琦禪師語錄 [Recorded Sayings of Chan Master Chushi Fanqi]. In 禪宗全書 [Complete Works of Chan Buddhism]. Taipei: Wen Shu Publishing Company, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yeran. 1980. 徑山志 [Jingshanzhi]. In 中國佛寺史志彙刊 [Compilation of Historical Records of Chinese Buddhist Temples]. Taipei: Mingwen, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ji. 1999. Preface to the Poem “Sending Monk Ke on a Distant Journey”. In 劉基集 [Liu Ji Collection]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Literature Publishing House, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shilin. 2010. 江南佛教文化的界定與闡釋 [The Definition and Interpretation of Jiangnan Buddhist Culture]. Academics 7: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Quansun. 1993. 江蘇通志稿 [Jiangsu Tongzhi Manuscript]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Ancient Literature Publishing House, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Mote, Frederick W. 1960. Confucian Eremitism in the Yuan Period. In The Confucian Persuasion. Edited by Arthur F. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mote, Frederick W. 1962. The Poet Kao Chi: 1336–1374. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Qianyi. 1996. 牧斋有学集 [Muzhai Youxueji]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Ryuchi, Kiyoshi. 1939. 明の太祖の仏教政策 [Buddhist Policies of the Ming Taizu]. 仏教思想講座 [Lecture on Buddhist Thought] 8: 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sensabaugh, David. 1989. Guests at Jade Mountain: Aspects of Patronage in Fourteenth Century K’yn-san. In Artists and Patrons. Edited by Chu-tsing Li. Lawrence: University of Kansas, pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Dahe. 2006. 南屏淨慈寺志 [Annals of the Jingci Temple at Nanping]. Hangzhou: Hangzhou Publishing House, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Jianye. 2009. 洪武時代佛教之研究 [A Study of Buddhism in the Hongwu Era]. Taipei: Mulan Cultural Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Laifu. 1995. 澹遊集 [Danyouj]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Literature Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Minghe. 1994. 續補高僧傳 [Continued Compilation of Biographies of Eminent Monks]. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Publishing Company, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sho, Enoki. 2013. 無文禅師行業 [Biography of Mumon]. In 元代日中渡航僧傳記集成 [Biographical Collection of Japanese Monks Traveling to China During the Southern Song and Yuan Dynasties]. Tokyo: Bensei Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Lian. 1999. 宋濂全集 [Songlian Quanji]. Hangzhou: Zhejiangguji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka, Gentei. 1960. 無文元選の行狀記について [Regarding the Record of Mumon Gensen’s Travels]. 印度學佛教學研究 [Research in Indian Buddhist Studies] 8: 251–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Zongyi. 1958. 南村輟耕錄 [Records of the Idle Farmstead in the Southern Village]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Xingdao. 1976. 天童寺志 [Tiantong Temple Annals]. Taipei: Guangwen Shuju, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Yingfang. 1986. 龜巢稿 [Guichao Gao]. Taipei: Taiwan Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Juzheng. 1478. 東文選 [Tongmunson]. Tokyo: National Archives of Japan Digital Archive Copy, vol. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yikui. 2008. 始豐稿校注 [Shifegngao Jiaozhu]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Guji Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Weizhen 楊維楨. 1929. 東維子文集 [Collected Works of Dong Weizi]. Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

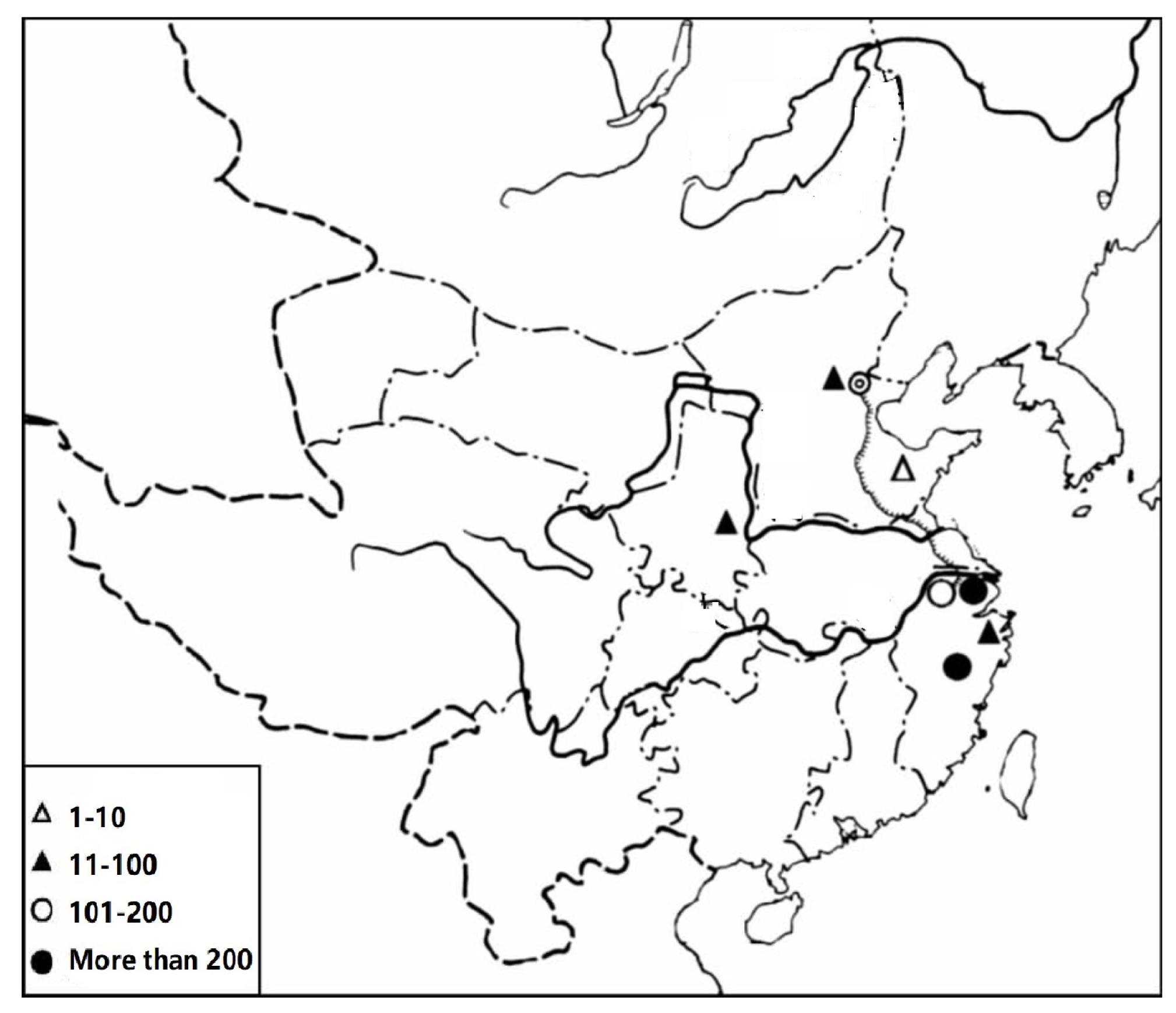

- Yin, Yan. 2017. 試論元代佛教寺院的地域分佈——基於元、明 《一統志》和地方誌的考察 [A Study on the Regional Distribution of Buddhist Temples in the Yuan Dynasty: Based on the Investigation of the “Yitong Zhi” of Yuan and Ming Dynasties and Local Chronicles]. Journal of Chinese Historical Geography 32: 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Chun-fang. 1982. Chung-feng Ming-pen and Ch’an Buddhism in the Yuan. In Yuan Thought: Chinese Thought and Religion under the Mongols. Edited by Hok-lam Chen and William Theodore de Bary. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 419–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Bochun. 1983. 至元辯偽錄序 [Preface to the Zhiyuan Bianwei Lu]. In Taisho Tripitaka 大正藏. Taipei: Xin Wen Feng Corporation, vol. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shiche. 2014. 嘉靖寧波府志 [Jiajing Ningbo Prefecture Gazetteer]. Nanjing: Fenghuang Chubanshe, vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xuan. 1344. 至正金陵新志 [Zhizheng Jinling Xin Zhi]. Special Collections CJK Microfilm. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yi. 1986. 可閑老人集 [Kexian Laoren Collection]. Taipei: Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Derun. 1973. 存復齋文集 [Cunfuzhai Collection]. Taipei: Xuesheng Shuju, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 2007. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

| Ranking | Temple Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Ahead of the five temples | 大龍翔集慶禪寺 Longxiang Temple | Jiqing (modern-day Nanjing) 南京 |

| 1st | 徑山興盛萬壽禪寺 Jingshan Temple | Hangzhou 杭州 |

| 2nd | 北山景德靈隱禪寺 Lingyin Temple | Hangzhou 杭州 |

| 3rd | 太白山天童景德禪寺 Tiantong Temple | Qingyuan (modern-day Ningbo) 寧波 |

| 4th | 南山淨慈報恩光孝禪寺 Jingci Temple | Hangzhou 杭州 |

| 5th | 阿育王山廣利禪寺 Ayuwang Temple | Qingyuan (modern-day Ningbo) 寧波 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X. The Influence of Wartime Turmoil on Buddhist Monasteries and Monks in the Jiangnan Region during the Yuan-Ming Transition. Religions 2023, 14, 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101294

Liu X. The Influence of Wartime Turmoil on Buddhist Monasteries and Monks in the Jiangnan Region during the Yuan-Ming Transition. Religions. 2023; 14(10):1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101294

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xunqian. 2023. "The Influence of Wartime Turmoil on Buddhist Monasteries and Monks in the Jiangnan Region during the Yuan-Ming Transition" Religions 14, no. 10: 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101294

APA StyleLiu, X. (2023). The Influence of Wartime Turmoil on Buddhist Monasteries and Monks in the Jiangnan Region during the Yuan-Ming Transition. Religions, 14(10), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101294