1. Introduction

Qiansui Baozhang 千歲寶掌 (413 BC–657 AD), who claimed to have lived for over 1000 years, is described as a legendary Indian monk said to have existed from the twelfth year of King Weilie 威烈 of the Zhou dynasty to the second year of Xianqing 顯慶 of the Tang dynasty. Baozhang earned the name “Baozhang (precious palm)” due to a distinctive physical characteristic—according to the legend, he was born with his left hand clenched in a fist, which remained until the age of 7 years. From the Song dynasty onwards, Baozhang was revered as the founding patriarch of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery 中天竺寺 in Hangzhou as well as a number of significant Chan monasteries throughout China.

1 It is worth noting that while the legend suggests that Baozhang visited China during the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420), records about him did not appear until the Song dynasty. The only two early sources providing his relatively comprehensive hagiographies are the local gazetteer

Jiatai kuaiji zhi 嘉泰會稽志 and the Chan historiography

Jiatai pu denglu 嘉泰普燈錄, compiled in the early thirteenth century. This raises the possibility that Baozhang might be a figure constructed by the people of the Song dynasty, instead of a historical figure with verifiable accounts.

While the inclusion of Baozhang in a local gazetteer indicates his veneration as a local cult, his appearance in the Jiatai pu denglu deserves further attention, as this Chan historiography eventually propelled him to become a widely embraced Chan ideal nationwide. The Jiatai pu denglu, compiled by the Yunmen 雲門 monk Zhengshou 正受 (1147–1209), was the only imperial-sanctioned denglu work during the Southern Song dynasty. Following the pattern of the preceding imperial-sanctioned denglu works, the Jiatai lu bore a title that comprised the era name and an adjective that highlighted its unique feature. As the Jingde chuan denglu 景德傳燈錄 emphasized “chuan 傳 (transmitting)” to establish a consistent geological system, the Tiansheng guang denglu 天聖廣燈錄 emphasized “guang (extensive)” to record extended lineages, and the Jianzhong jingguo xu denglu 建中靖國續燈錄 emphasized “xu (continued)” to preserve ongoing transmission, the Jiatai pu denglu accentuates on “pu (universal)”, substantially extending its inclusion to recognize lay communities as Dharma transmitters, protectors, and patrons. Since the Jingde chuan denglu, imperial-sanctioned Chan historiographies were no more mere Chan literary works circulating within local Chan communities, but became documents for standardizing Chan history and systemizing Chan lineages. Consequently, the Jiatai pu denglu assumed a crucial role as an influential Buddhist record, holding significance not only within the Chan community, but also within the broader cultural context of its time.

Although denglu works traditionally serve the primary purpose of preserving genealogical information about the Chan school and the profound teachings of Chan masters, Qiansui Baozhang, who lacks a clear genealogical connection to any Chan lineage, is listed as the first figure in a distinct section titled “Yinghua shengxian 應化聖賢” (Sages and Worthies as Earthly Manifestations of Buddhist Deities) in the Jiatai pu denglu. Alongside him, nine other individuals, who can be identified as “outsiders” to the institutional Chan school, are venerated as Chan ideals. This research on Baozhang, therefore, revolves around several questions. First, it aims to ascertain the identity of Qiansui Baozhang and explore how he was portrayed in various sources. Second, it seeks to determine the timing and factors that led to his recognition as the founding patriarch of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. Third, it purports to investigate the roles of the Jiatai pu denglu and his portrayal as a Chan ideal in promoting his cult. By addressing these questions, I intend to delineate a general trajectory of the evolution of Baozhang’s worship, tracing its progression from a local cult to a national perception.

This paper comprises three main sections. In the first section, I use extensive local gazetteers as primary sources to present the various local sites associated with Baozhang’s cult and restore the prevailing image of Baozhang in the local area. The second section focuses on Baozhang’s connection with the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. I mainly draw upon an essay authored by a Southern Song literatus, which stands as the earliest existing record about Baozhang as the founding patriarch of the monastery. In the third section, I adopt a close reading and detailed analysis of Baozhang’s account which is preserved in the Jiatai pu denglu. It was through this Chan historiography that Baozhang gained prominence as an influential Chan ideal. The dissemination of his story reached even the far west of the border province of the Song Empire, which led many monasteries to associate themselves with this legendary monk and enhance their reputation by claiming Baozhang as their founding patriarch.

By elucidating the trajectory of Baozhang’s worship from a local cult to a national perception, I argue that the recognition of Baozhang’s cult exemplifies the Chan school’s acknowledgment and response to the prevalent folk Buddhist cults during that period. By integrating Baozhang’s cult into their narratives and molding his portrayal as a Chan ideal, the Chan school capitalized on the value of this legendary monk to elevate its own status in the Buddhist convention. This research also demonstrates the Chan school’s active engagement with and adaptation to the religious landscape of the Song dynasty. Traditionally, Chan historiographies have been employed for the study of internal matters within the Chan school, such as lineage transmission and doctrinal teachings. The exploration of Baozhang, however, could compel us to reevaluate the function and utilization of Chan historiographies. What can be read from Chan historiographies is more than Chan genealogical information and teachings, but also the Chan school’s dynamic interactions with the prevalent ideological currents within the religious milieu of the time.

Qiansui Baozhang is indeed an intriguing figure, and yet, a comprehensive study of him remains lacking in both Chinese and English academia. Chinese scholar Wang Dawei has one article delving into Baozhang’s journey in China, drawing on his account in the

Wudeng huiyuan 五燈會元.

2 He argues that Baozhang embodies a hybrid character, displaying features of both Chinese and Indian monks. This actually reflects the Song people’s imagination of Indian monks during the matured period of Buddhist Sinicization.

3 In addition to examining Qiansui Baozhang, the “

Yinghua shengxian” sections in the Chan historiographies also deserve more scholarly attention.

4 As a section recurring in various Chan historiographies, it upheld a tradition to portray figures who were “outsiders” to Chan lineages as Chan ideals.

5 Critical questions arise regarding the significance of these “outsiders” to the Chan school and why they are valued within the Chan context. Although some previous scholarship has touched upon certain figures listed in the “

Yinghua shengxian” sections, a thorough investigation of these unique sections is currently absent

6 A chronological survey on the figures compiled in the “

Yinghua shengxian” sections reveals not only an increase in the number of the figures, but also a diversification of their backgrounds, including individuals such as Tiantai patriarchs, Daoist True Men, folk deities, and even an emperor. Notably, Baozhang was not the only local cult figure to be incorporated into the Chan historiography. Two more figures, the Ancient Buddha Koubing Zaoxian 扣冰藻先古佛 and Venerable Nan’anyan Ziyan 南安岩自嚴尊者, developed their own cults in Fuzhou 福州 and Tingzhou 汀州, respectively, before being compiled in the “

Yinghua shengxian” section. Through my research on Qiansui Baozhang, which serves as one of the case studies within my comprehensive investigation of the “

Yinghua shengxian” sections, I aim to reveal that the Chan school in the thirteenth century was more inclusive and accommodating than previously assumed.

2. Local Cult Figure and External Alchemist: Baozhang in Local Gazetteers

Among the surviving sources, the earliest complete account of Qiansui Baozhang can be found in the

Jiatai kuaiji zhi, a local gazetteer completed in 1201. However, literary works from the mid-Northern Song period also contain references to Baozhang. The Northern Song literatus Qiang Zhi 強至 (1022–1076), who originated from Hangzhou, wrote two poems related to the sites associated with Baozhang: “Visiting Baozhang Cloister 遊寶掌院”

7 and “Being Caught in Rain When Visiting Mt. Baozhang—Replying to Chunfu by the Same Rhyme 次韻和純甫遊寶掌遇雨”.

8The common theme of the two poems is to emphasize the sanctity of the region that bears Baozhang’s name. In the first poem, it has “While lay people are not permitted to leave any traces, it is the duty of the sacred site to protect the gate of the mountain. 不許俗人留轍迹, 却應神物護巖扃”. Qiang contrasts secular individuals with divine figures, suggesting that the location of the Baozhang Cloister is a sacred religious realm. This contrast can also be seen in the second poem, where he said the mountain god should clean the road to prevent worldly impurities (山神應洗路, 恐惹俗塵多). In the last line of the first poem, Qiang summarizes that the rough sketch on the map was not comparable to the real scenery (今日一來探絕賞, 始知全勝考圖經). From Qiang’s description, it becomes apparent that the Baozhang Cloister held enough fame to be marked on local maps. Additionally, considering that the complete account of Baozhang emerged relatively late, it is likely that the story of Baozhang was transmitted orally in this region prior to the mid-Northern Song period.

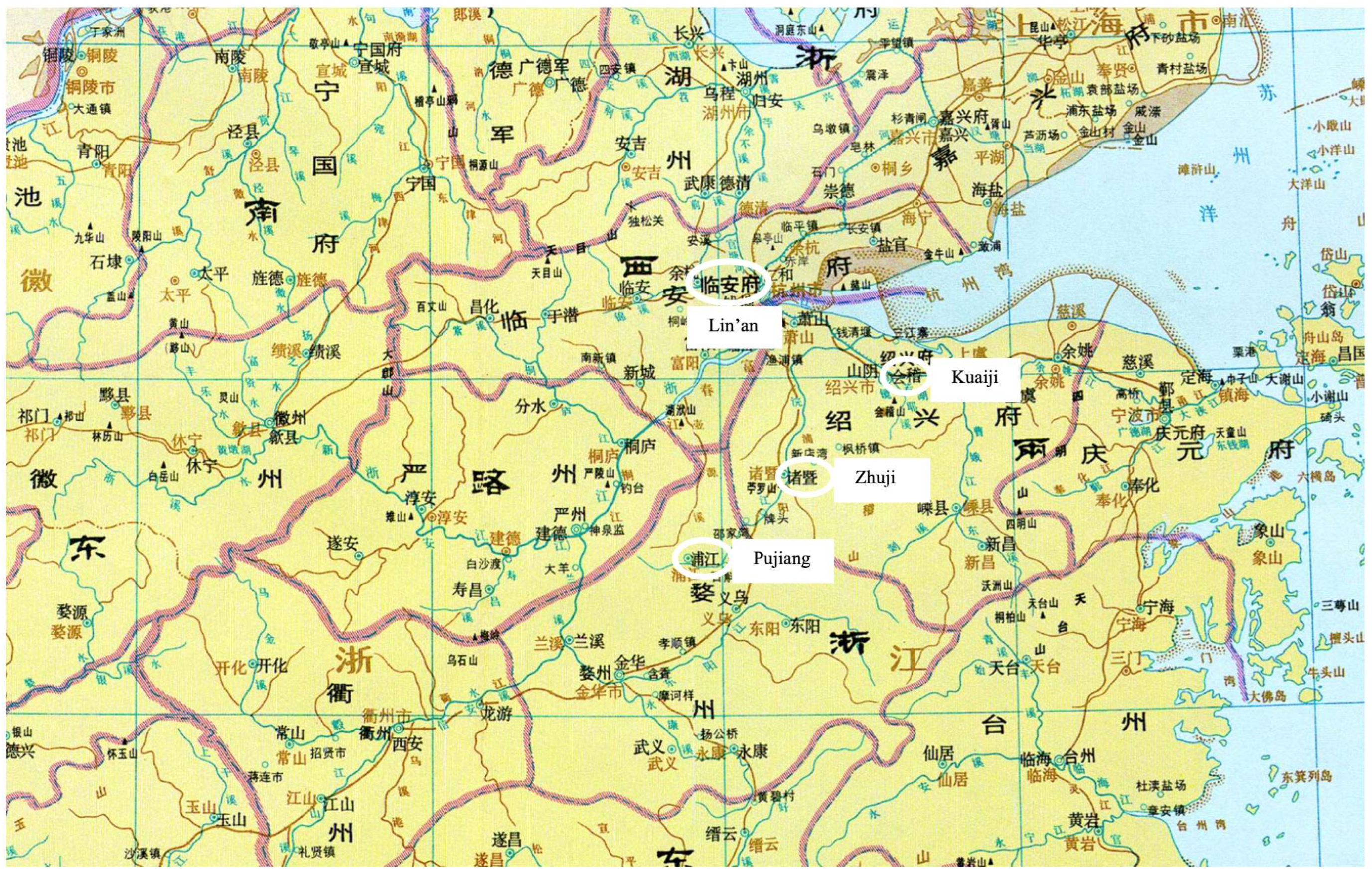

Unfortunately, Qiang did not provide specific information regarding the location of these sites. However, based on the poems, we can discern that a Buddhist complex called the Baozhang Cloister was located in a mountain also named after Baozhang. As the Northern Song sources offer limited details about Baozhang’s sites, I have to rely on gazetteers compiled during the Southern Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties as references. According to these sources, the clusters of Baozhang’s sites can be identified in three counties—Kuaiji 會稽, Zhuji 諸暨, and Pujiang 浦江. These counties were collinearly located from northeast to southwest in the Liangzhe East Circuit兩浙東路, as the map shows (

Figure 1):

Information concerning Baozhang’s sites in Kuaiji and Zhuji counties is primarily preserved in the Jiatai kuaiji zhi, which is the earliest reliable source for tracing these sites. This gazetteer lists five sites dedicated to the cult of Baozhang, including Mingjue Cloister 明覺院, Chongsheng Cloister 崇勝院, Yanqing Cloister 延慶院, Shang Purun Cloister 上普潤院, and Baozhang Cliff 寶掌巖.

Mingjue Cloister is located on Mt. Cifu, which was approximately thirty-five li east of the county [Kuaiji]. [This cloister] was initially constructed in the eighteenth year of Kaiyuan during the Tang dynasty. Unfortunately, it was destroyed during the Huichang persecution. Nevertheless, it was rebuilt in the eighth year of Tianfu during the Jin dynasty and renamed the Daming Cloister. Since the second year of Zhiping, its plaque was changed to the present name [Mingjue Cloister]. Within its premises, there is a pagoda of monk Qiansui, along with his stone tablet. The story [of monk Qiansui] is unsubstantiated and lacks verification. Nonetheless, the cloister itself is known for its exceptional seclusion and scenic beauty.

明覺院:在縣(會稽)東三十五里刺浮山。唐開元十八年建,會昌毀廢。晉天福八年復建,號大明院。治平二年改今額。有千歲和尚塔,亦有碑。而其說荒怪,不可攷質。然院頗幽絕可愛。

Chongsheng Cloister is located approximately forty-five li southeast of the county [Zhuji]. This cloister was originally constructed in the fifteenth year of Zhenguan during the Tang dynasty by the Chan master Qiansui. However, it suffered destruction during the Huichang persecution. It was then rebuilt during the Dazhong period. In the second year of Xianping, the cloister was renamed Huayan Bore Cloister. Eventually, its plaque was changed to its present name.

Yanqing Cloister is located approximately seventy li southeast of the county [Zhuji]. The cloister was constructed in the first year of Zhenguan during the Tang dynasty. Due to the Chan master Qiansui’s practice at this location, it came to be known as Daochang Cloister (Cloister of Practice). Unfortunately, it was destroyed during the Huichang persecution. However, it was rebuilt in the eighth year of Xiantong and renamed Xishan Cloister. In the fifth year of Xiande in the Later Zhou dynasty, it was renamed Xingfu Yong’an Cloister. In the first year of Dazhong Xiangfu, it was bestowed its current plague.

延慶院:在縣(諸暨)東南七十里。唐貞觀元年建,有千歲禪師修行於此,因號道場院。會昌廢,咸通八年重建,又號溪山院。周顯德五年改興福永安院。大中祥符元年改賜今額。(

Shi 1983, p. 6282)

Shang Purun Cloister is located approximately twenty-five li southeast of the county [Zhuji]. It was initially the residence of monk Qinasui. Within its premises, there is a small rock featuring carvings of Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra. The cloister was built in the seventh year of Tianfu during the Jin dynasty and originally named Liquan yuan. Later, it was changed to the current name.

Baozhang Cliff, located approximately forty-five li southeast of the county [Zhuji], used to be Chan master Baozhang’s residence. It is also known by the name of the Qiansui Cliff. The Chan master, whose name remains unknown, claimed to have been born towards the end of the Zhou dynasty. During the Wei and Jin dynasties, he traveled from the west to the Shu region. In the fifteenth year of Zhenguan, he began dwelling in this cave. He passed away in the first month of the second year of Xiande of the Latter Zhou dynasty, thereby living for 1072 years. The cliff features a carved portrait of him in the middle, approximately forty-nine chi high from the ground. The stone chamber has the capacity to accommodate over a hundred people. Within the cave, several stone tablets are present, appearing as though they have been meticulously polished. It is believed that this was a bathing spot for local inhabitants. Additionally, Chan master Qiansui once planted a palm tree here, which has thrived for several hundred years.

寶掌巖:在縣(諸暨)東南四十五里,寶掌禪師所居也。一名千歲巖。禪師不知名氏,自云生於周末。當魏晉間,由西域入蜀。貞觀十五年開岩於此,周顯德二年正月遷化。壽一千七十二歲。真儀在半巖,去地四十九尺。石室可容百餘人,洞內石版數片如削。傳云裏人沐浴之所。禪師種貝多木一枝,亦數百年矣。(

Shi 1983, p. 6309)

The account of Baozhang Cliff can also be found in

Yudi jisheng 輿地紀勝 by Wang Xiangzhi 王象之, which was compiled during the year of Baoqing 寶慶 (1225–1227).

9 Furthermore, in the Zhuji Xianzhi 諸暨縣志 compiled during Emperor Kangxi’s reign, the compiler references Ming literatus Cao Xuequan’s 曹學佺 work, Yudi mingshengzhi 輿地名勝志, which provides information about Mt. Baozhang. It was revealed that this Mt. Baozhang is an alternative name for Baozhang Cliff recorded in the Jiatai kuaiji zhi.

10 In addition, the

Shaoxing fuzhi 紹興府志 has a record regarding the palm tree planted by Baozhang, stating, “Palm tree: planted by Chan master Baozhang during the Zhenguan era in the Tang dynasty. It is located at Baozhang Cave in Zhuji”.

11Mt. Baozhang also appeared in Pujiang county. According to the

Wanli Jinhua fuzhi 萬曆金華府志, Mt. Baozhang is located eight

li north of the county and is near Mt. Xianhua 仙華. Moreover, in front of the mountain, there is a towering cliff known as Feilai Peak 飛來峰.

12 Since Pujiang county is in southwest of Zhuji, this Mt. Baozhang cannot be the same as the one in Zhuji. Interestingly, this Feilai Peak shares the same name as the more famous Feilai Peak on Mt. Tianzhu in Lin’an. It is possible that this substitution occurred after Baozhang became associated with the Hangzhou Feilai Peak. Within Mt. Baozhang, there is another site related to Baozhang called Baozhang Cold Spring 寶掌冷泉. The Yuan literatus Liu Guan 柳貫, who hailed from Pujiang, composed a poem dedicated to this spring.

13 Later, the Ming literatus Zheng Dongbai 鄭東白 had a poem titled

Visiting Baozhang Cave on Mt. Xianhua 游仙華山寳掌洞記, suggesting the existence of another Baozhang Cave located in Mt. Xianhua.

14Upon reviewing the information gathered from local gazetteers regarding Baozhang’s sites, it is appropriate to revisit Qiang Zhi’s poems. Although Qiang Zhi did not provide specific details about the Baozhang site he visited, his occupational mobility can serve as a useful reference. Qiang Zhi’s earliest biography in the surviving sources can be found in the Xianchun lin’an zhi 鹹淳臨安志, completed in 1268. It merely mentions that he was recruited by Han Qi 韓琦 (1008–1075) due to his well-rounded character and literary talent.

15 Qiang’s chronological biography is preserved in the Songshi yi 宋史翼 by the Qing literatus Lu Xinyuan 陸心源. According to this account, Qiang’s official career began with his appointment as the administrator for Public Order in Sizhou 泗州司理參軍. He was subsequently assigned to Pujiang, Dongyang 東陽, and Yuancheng 元城. In the fourth year of Zhiping (1067), he became a Confidential Copier 書記 under Han Qi and relocated to Bianjing 汴京. Following this, he was promoted to positions within the central government and remained in the capital city until his passing (

Lu 1967, pp. 1113–15).

This timeline roughly outlines the trajectory of Qiang’s life, which can be divided into two periods: Qiang resided in the southern regions prior to assuming the office of Yuancheng in the Hebei region, after which he lived in the north for the rest of his life. Given that he once held an office in Pujiang county, it is reasonable to speculate that he composed the two poems during his visit to Mt. Baozhang in that area. Thus, it can be inferred that the cult of Baozhang had already established its presence in Pujiang during the first half of the eleventh century.

The Jiatai kuaiji zhi may also have preserved an early version of Baozhang’s account, which differed significantly from the version found in the Jiatai pu denglu.

Monk Qiansui, also known as Chan master Baozhang, was an Indian who was born during the late Zhou dynasty. During the Wei and Jin dynasties, he arrived from the western regions. Instead of having regular meals, he only consumed lead and mercury. One day, while giving a lecture to his disciples, he said, “I desire to reside in this world for a thousand years. To date, I am 673 years old”. As a result, he acquired the title of monk Qiansui (1000 years). During the Zhenguan era of the Tang dynasty, he traveled throughout the Liangzhe region (Zhejiang xilu 浙江西路 and Zhejiang donglu 浙江東路). When he reached the foot of Mt. Lipu in Zhuji, he encountered an old man. The old man inquired, “Where are you planning to go?” The master replied: “To seek a place for practice as I am growing old”. The old man said: “Walk along the north side of this mountain. In the deep and tranquil woods covered by the hill screen, there is a stone chamber known as Lipu Cave. Why do not go and live there?” During the mid-autumn, the master arrived at the cave. He was captivated by the lush mountain, clear springs, bright moon, and refreshing breeze. He made eulogies and wrote the line, “Having traveled throughout the four hundred prefectures of China, only this place is worth wandering”. He then constructed a cottage to reside in, devoting himself to silent meditation for 17 years. One day, he counted on his fingers and realized that he had reached the age of 1072. He conversed with his disciple Huiyun and said: “My death is impending. I will teach you the [method of making] the Reverted Elixir.” Presently, there is a Baozhang Cliff in Zhuji and a pagoda dedicated to monk Qiansui at the Mingjue monastery on Mt. Cifu in Kuaiji. Additionally, there is a Bone-Washing Pond of Qiansui associated with his legacy.

千歲和尚寶掌禪師,中印土人,生周末,當魏晉時來自西域。居常不食,唯服鉛汞而巳。一日示眾,曰:“吾欲住世千歲,今六百七十三歲矣。”因號千歲和尚。唐貞觀中,周游二浙。至諸暨里浦山下,遇一老人,問:“欲何之?”師曰:“訪地修行,吾將老焉。”老人曰:“循山之陰,林嶂幽聳中,有石室,名里浦岩。盍往居之。”值中秋,師抵岩下。見其山秀泉潔,月白風清。為頌,有“行盡支那四百州,此中偏稱道人游”之句。遂結茆以居,宴坐十七年。一日屈指,一千七十二歲矣。語其徒惠雲曰:“吾將謝世,以還丹授汝。”今諸暨有寶掌岩,會稽剌浮山明覺寺有千歲和尚塔,又有千歲洗骨池。

This account provides some basic information about Baozhang, such as his home country, life span, and the specific regions he resided in China. Moreover, it has some additional significant details. One striking aspect is that Baozhang is depicted as a practitioner of Taoist external alchemy, also known as

waidan 外丹. Not only did he sustain his life by ingesting lead and mercury, but he also intended to transmit the method of making the reverted elixir, the essence of his teaching, to his disciple. Lead and mercury as two chief ingredients in the external alchemical practice were usually used for making elixir, a “medicine” to extend one’s lifespan and to attain immortality. The reverted elixir refers to the alchemical process primarily involving a firing method, through which metals like gold and jade will be refined to become elixir. According to

Baopuzi抱樸子, the reverted elixir will transform the practitioner into an immortal immediately.

16 By the end of his life, Baozhang sought to transmit the knowledge of creating the reverted elixir to his disciple, prioritizing this alchemical practice over doctrinal teachings or meditation skills. The emphasis on Baozhang’s alchemical practice rather than associating him solely with Buddhist elements presents a somewhat contradictory image of him as an external alchemical Buddhist practitioner. This account, which might be an early version or at least one circulated within local regions, introduces elements that have clear inconsistencies regarding the portrayal of Baozhang.

Furthermore, the account outlines Baozhang’s travel route in China, particularly highlighting the Liangzhe region and Mt. Lipu in Zhuji county. Baozhang is said to have been deeply impressed by the extraordinary beauty of Mt. Lipu, leading him to choose it as his residence and even to compose a verse praising its splendor. Apparently, the compiler of this account likely intended to use Baozhang’s legend to promote Mt. Lipu. Interestingly, in the account compiled in the Jiatai pu denglu, the same verse is used to extol the Feipai Peak on Mt. Tianzhu, indicating the different focuses of the compilers.

Lastly, the account mentions several cultic sites associated with Baozhang, including the Baozhang Cliff in Zhuji, the Baozhang pagoda, and the Bone-Washing Pond in the Mingjue monastery on Mt. Cifu in Kuaiji. The cliff and the monastery can be verified through the aforementioned sources. However, the Bone-Washing Pond is not mentioned in the entry for the Mingjue monastery, suggesting that it might be an additional piece of information. The story alluded to by this site can be found in the Jiatai pu denglu, which will be elaborated on later.

3. Founding Patriarch: Baozhang with the Zhong Tianzhu Monastery

It is evident that the registration of these local sites in the gazetteers was ascribed to the legend and popularity of Baozhang. As Baozhang’s story and his cult spread to other regions, his image started to be linked with more renowned sites like the Zhong Tianzhu monastery.

The Zhong Tianzhu monastery, alternatively known as Fajing monastery 法淨寺, was located on the Jiliu Peak 稽留峰 between the Shang Tianzhu monastery 上天竺寺, Faxi monastery 法喜寺, and the Xia Tianzhu monastery 下天竺寺, Fajing monastery 法鏡寺. Despite the unclear origin, the monastery witnessed several significant events during the Song dynasty. According to the

Fajing sizhi 法淨寺志, in the first year of Taiping xingguo 太平興國 (976), the Wuyue king rebuilt it and renamed it Chongshou Cloister 崇壽院. In the fourth year of Zhenghe 政和 (1114), Emperor Huizong changed its name to Tianning Wanshou Yongzuo Chan monastery 天寧萬壽永祚禪寺. When the Song imperial court fled south, Emperor Gaozong sought protection from Bodhisattva Marici. It was reported that the deity exhibited sympathetic resonance and used divine power to conceal the emperor from Jurchen soldiers. Shortly after the Song imperial court settled in Lin’an, Emperor Gaozong bestowed the Zhong Tianzhu monastery a statue of Bodhisattva Marici, which was previously enshrined in the palace.

17It remains unknown the exact time period when Baozhang began to be venerated as the founding patriarch of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. However, an essay by literatus Wang Xin 王信 (1137–1194) evinces that Baozhang’s cult was worshipped in the monastery before the mid-Southern Song dynasty.

18This essay, entitled the “Record of Huayan Pavilion”, was written for commemorating the restoration undertaken within the building complex of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery.

19 Due to the important information regarding the connection between Baozhang and the monastery, I will systematically analyze it by dividing it into several sections.

In the opening, Wang explicitly highlights the unfavorable circumstances confronting the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. Despite its location on a renowned mountain, the growth of the monastery was impeded by its dilapidated condition. In comparison to the other two Tianzhu monasteries, the Zhong Tianzhu appeared to be in isolation. Thus, it becomes evident that by the early Southern Song dynasty, both the size and financial resources of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery were incomparable to those of prominent monasteries like Lingyin monastery 靈隱寺 and Jingci monastery 淨慈寺, which enjoyed patronage from the imperial court. Even among the three Tianzhu monasteries, it is plausible that the Zhong Tianzhu was considered inferior to its sister monasteries, the Shang Tianzhu, and the Xia Tianzhu.

The situation of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery was improved when monk Fahua assumed the abbotship, for he effectively rescued the monastery from its brink of bankruptcy. The most remarkable endeavor that Fahua made was the organization of a rain praying ceremony. In the fourteenth year of Chunxi 淳熙 (1187), the Zhong Tianzhu monastery received an official order, which instructed the monastery to pray for rain to Bodhisattva Guanyin, the primary deity enshrined in the three Tianzhu monasteries. Although official records about this event were scarce, as it was likely a localized ceremony, Wang Xin, at the invitation of Fahua, documented the proceedings. Through his observation, we are able to gain insight into the revitalization of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. According to his account, in the main hall there resided a statue of Mahāvairocana, who was flanked by Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra. Surrounding these deities were the fifty-three wise men whom Sudhana visited in the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra. Adjacent to the main hall were the bell platform and the sutra platform on the two sides. Wang was deeply impressed not only by the grandeur of the monastic complex, but also by Fahua’s resolute determination and execution. In response to Fahua’s request, Wang recorded the timeline and duration of the reconstruction project, which spanned over 3 years from 1183 to 1186.

Instead of seeking personal credit, Fahua humbly attributed this achievement to the power of Qiansui Baozhang, the divine monk who appeared in his dream. This brief account of Baozhang represents the earliest surviving source that documents his biographical information and his connection to the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. According to Fahua’s introduction, Baozhang, who lived for an astonishing 1072 years from the twelfth year of King Weilie of Zhou (BCE 414) to the second year of Xianqing of Tang (657), was the founder of the monastery. In the winter of the sixth year of the Chunxi (1179), during the midnight of the fifteenth day of the eleventh month, Fahua dreamt about a monk who identified himself as monk Qiansu. In Fahua’s description, the monk showed a typical exotic appearance which is similar to a high horsehead and wearing golden earrings. Baozhang entrusted Fahua with the tasks of revitalizing the monastery and promoting his teachings. Interpreting this dream as an auspicious sign, Fahua gathered the assembly in the following morning and held a ceremony in front of Baozhang’s portrait. While Wang expressed some skepticism towards Fahua’s account, he discovered a line from a verse composed by Baozhang on his deathbed, which read, “[I will] come back in another life”, serving as potential evidence to support Fahua’s dream.

Wang’s description of Fahua’s dream provides several important pieces of information. First, it articulates Baozhang’s year of birth and death, which aligned with those found in later hagiographies. This suggests that the basic information about Baozhang’s legend had started to be substantiated. Second, it establishes the connection between Baozhang and the Zhong Tianzhu monastery, where he is revered as the founding patriarch, and his portrait is venerated. Since this record was written in 1187, it demonstrates that their connection predates the mid-Southern Song period. Third, when quoting Baozhang’s verse, Wang mentions that he examined the lines and discovered that particular sentence. This implies that he might not be familiar with Baozhang’s literary works, and it is possible that he had not previously read Baozhang’s stories and verses until this visit. Lastly, showing up in Fahua’s dream, Baozhang instructed him to renovate the monastery and thereby promote his teaching (今汝能建立, 吾道興矣). This detail suggests that Baozhang’s presence probably remained unknown in Lin’an before the monastery’s renovation took place.

Wang Xin’s record highlights the critical role of Abbot Fahua in promoting Baozhang’s cult at the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. Seizing the opportunity of the rain praying ceremony, Fahua extended invitations to a number of government officials. The ceremony served not only to showcase the renovated monastery, but also to propagate the worship of Baozhang among literati.

Unfortunately, Fahua’s biographical information is scarce in existing sources, and Wang’s record appears to be the primary and perhaps the only account providing insights into this monk. According to Wang, Fahua originated from the Guangdong region (Guangnan East Circuit 廣南東路). Since he had the dream of Baozhang in the sixth year of Chunxi (1179), he must have resided at the Zhong Tianzhu monastery prior to that. The

Fajing sizhi lists several notable abbots who had previously resided at the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. Among them, four were from the Song dynasty, including Haikong 海空, Fodeng 佛燈, Aotang Zhongren 拗堂中仁, and Chijue Yuanmiao 癡絕元妙 (

Sun 2006, pp. 101–3). Haikong was said to have resided at the monastery for 16 years during the reign of Emperor Ningzong 寧宗 (1194–1224). After his passing, the abbotship was passed on to Fodeng, who remained at the monastery for 12 years during the year of Jiading 嘉定 and Duanping 端平 periods. Aotang Zhongren, a disciple of Yuanwu 圓悟, assumed the abbotship of Dajue monastery 大覺寺 soon after the relocation of the imperial court to Lin’an. He then was appointed to administer Zhong Tianzhu monastery and Lingfeng monastery 靈峰寺 successively. Regrettably, the available source does not specify Zhongren’s tenure at the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. Zhongren was summoned to the imperial court by Emperor Xiaozong 孝宗 during the year of Chunxi (1174–1189) and passed away in the second year of Jiatai (1202). Considering Fahua’s arrival at the monastery before the sixth year of Chunxi, it is highly likely that Fahua succeeded Zhongren as the next abbot. The last Song dynasty abbot on the list, Chijue Yuanmiao, resided at the monastery during the early year of Shaoxing 紹興 (1131–1162). Given the timeline described above, it is reasonable to suggest that Zhongren assumed the abbotship after Yuanmiao, followed by Fahua’s succession.

4. Chan Ideal: Baozhang in the Jiatai pu denglu

Upon the completion of the Jiatai pu denglu in 1204, Baozhang’s prominence was solidified as he was listed as the first ideal in the “Yinghua shengxian” section. His hagiography underwent significant expansion, portraying him as a divine monk devoted to sutra chanting and an awakener having attained enlightenment through direct instruction from Bodhidharma. Notably, his travel route throughout China covered nearly all the locations of great significance to the development of Chan Buddhism. In this account, the compiler Zhengshou rewrote Baozhang’s hagiography, ensuring that his portrayal fits well in the Chan context.

I will provide an analysis after each paragraph of the translation.

Chan master Qiansui Baozhang originated from the central region of India. In the twelfth year of King Weilie of the Zhou dynasty, he was born with divine qualities. His left hand remained clenched into a fist until the age of 7 years when he cut his hair to embark on his monkhood. It was due to this feature that he was named Baozhang. During the Wei and Jin dynasties, he traveled eastward and arrived in China. He visited Xishu (Western Shu) to pay homage to Samantabhadra and resided at the Daci monastery. He did not adhere to regular meals but instead devoted himself to reciting sutras, such as reciting the Prajnā Sutra for several thousand fascicles each day. Some people lauded him, saying, “His jade-like teeth toil in the cold, resembling the bursting of a rapid mountain spring.” Sometimes he would sit on the steps at midnight, evoking tears from both deities and ghosts. One day, he addressed the assembly, announcing, “I have a wish to reside in this world for a thousand years. Currently, I am at age six-hundred-and-twenty-six”. Consequently, people bestowed upon him the appellation Qiansui, meaning “thousand-year”.

千歲寶掌禪師,中印度人也。周威烈十二年丁卯。降神受質。左手握拳。至七歲祝髮乃展。因名寶掌。魏晉間。東游此土。入蜀禮普賢。留大慈。常不食。日誦般若等經千餘卷。有詠之者曰。勞勞玉齒寒。似迸巖泉急。有時中夜坐堦前。神鬼泣。一日。謂眾曰。吾有願住世千歲。今年六百二十有六。故以千歲稱之。

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434a4–434a9)

The account begins by explaining the origin of Baozhang’s name, which was derived from one of his divine qualities—the clenched left hand, and it opened soon after he became a monk. Along with providing specific details about his birth and death years, the account elaborates on Baozhang’s travel route within China. It starts with his initial residence at the Daci monastery in Chengdu, where he worshipped Bodhisattva Samantabhadra. Considering that the cult of Samantabhadra on Mt. Emei actually rose to prominence during the Song dynasty, scholar Wang Dawei proposes that Baozhang’s case exemplifies the symbiotic relationship between the construction and association of a charismatic religious figure with a sacred mountain.

20 Baozhang’s residences after the Daci monastery in Xishu will be elaborated on in the subsequent sections. While the account also mentions that Baozhang did not take regular meals, rather than relying on alchemical elixirs, as highlighted in the

Jiatai kuaiji zhi, he engaged in reciting sutras for thousands of fascicles as part of his daily routine. This adaptation suggests that the author removed Taoist elements from Baozhang’s hagiography and transformed him into a devout Buddhist figure.

He then traveled to Wutai and successively resided in the Huayan on Zhurong, the Shuangfeng on Huangmei, and the Donglin on Lushan. Upon his arrival in Jianye, he encountered Bodhidharma, who had recently arrived in China by chance. The master embraced Bodhidharma’s teachings and attained enlightenment. Emperor Wu esteemed his spiritual accomplishment and invited him to the inner hall of the palace. Shortly thereafter, he ventured to the Wuyue region. He composed a verse, stating: “Encountering my spiritual guide in China, I gained profound insight into the nature of my mind through meditative practice. As I traverse the Liangzhe region, I intend to explore all the enchanting mountains and rivers”.

次游五臺,徙居祝融之華嚴,黃梅之雙峰,廬山之東林。尋抵建鄴,會達磨入梁,師就扣其旨開悟。武帝高其道臘,延入內庭。未幾,如吳。有偈曰:“梁城遇導師,參禪了心地。飄零二浙游,更盡佳山水。”

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434a9–434a13)

The following places in Baozhang’s travel route hold significant historical importance in the context of Chan Buddhism. Upon departing Xishu for Mt. Wutai 五臺, Baozhang consecutively resided at Huayan monastery 華嚴寺 on Mt. Zhurong 祝融, Huangmei monastery 黃梅寺 on Mt. Shuangfeng 雙峰, and Donglin monastery 東林寺 on Mt. Lu 廬山. Mt. Wutai, revered as the center of Mañjuśrī’s worship, experienced high prosperity during the Tang dynasty and retained its unsurpassable status in the Song Buddhist landscape. Zhurong Peak, a part of Mt. Heng 衡山 in Nanyue 南嶽, was once the residence of Nanyue Huairang 南嶽懷讓. The Huangmei monastery 黃梅寺, located in Huangmei county at the foot of Mt. Shuangfeng, served as the residence of the fourth patriarch Daoxin 道信. Moreover, Huangmei county housed the Dongshan monastery 東山寺, which is associated with the fifth patriarch Hongren 弘忍. The Donglin monastery on Mt. Lu was the headquarters of Huiyuan’s 慧遠 Lotus Society 蓮社, which played a prominent role in the Pure Land movement during the Song dynasty.

Subsequently, Baozhang is said to have met Bodhidharma in Jiankang 建康 and attained enlightenment through Bodhidharma’s instruction. The intention of the author to include this episode is evident: despite the legendary status of Baozhang, he still required Bodhidharma’s guidance to attain the ultimate awakening. Ironically, Baozhang as an Indian monk hailing from the birthplace of Buddhism, found enlightenment through the words of Bodhidharma, an emblematic figure of Chinese Chan Buddhism. This implies the superiority of Chan teachings within Buddhism, while also indicating the confidence of Chinese Buddhists when interacting with their Indian counterparts, which marks the maturity of Chinese Buddhism.

Descending the stream to the east, he left Qianqing for Tianzhu. He visited Maofeng, ascended to Taibai, and journeyed through Yandang. He extensively explored seventy-two cloisters on Cuifeng. Following that, he returned to Chicheng and consecutively resided at Yunmen Fahua, Zhuji Lipu, and Chifu Dayan. He then returned to Feilai and took shelter in a cave. He composed a verse, “Having traversed four hundred prefectures in China, I found only this place worth wandering.” This occurred during the fifteenth year of Zhenguan.

順流東下,由千頃至天竺。往鄮峰,登太白,穿鴈蕩。盤礴於翠峰七十二庵。回赤城,憩雲門法華,諸暨里浦,赤符大巖等處。反飛來棲之石竇,有“行盡支那四百州。此中偏稱道人游”之句。時貞觀十五年也。

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434a13–434a17)

Following his previous travels, Baozhang was said to have embarked on a southeast journey from Mt. Qianqing 千頃 to Tianzhu. The places he visited in the Liangzhe region were likely significant Buddhist centers, particularly during the Song dynasty. He explored Peak Mao 鄮峰, ascended Mt. Taibai 太白山, and passed through Mt. Yandang 雁蕩山, visiting a total of seventy-two cloisters on Peak Cui 翠峰. Upon returning to Mt. Chicheng 赤城山, he resided at Mt. Yunmen 雲門山, Fahua 法華, Zhuji Lipu 諸暨裡浦, and Chifu Dayan 赤符大巖. Eventually, he returned to Tianzhu and resided in a cave on Peak Feilai 飛來峰.

According to Wang Dawei’s research, it is documented that Huangbo Xiyun 黃檗希運, the founding patriarch of the Huangbo branch of the Linji school, established his teachings on Mt. Qianqing (

Wang 2013, p. 130). Moreover, Tang Chan masters Chu’nan 楚南 and Wuzhu Wenxi 無著文喜 preached there. Mt. Tianzhu was renowned for its three Tianzhu monasteries, among which Baozhang was associated with the Zhong Tianzhu, as discussed earlier. Peak Mao and Mt. Taibai, home to Yuwang monastery 育王寺 and Tiantong monastery 天童寺, respectively, held the second and third positions in the Five Mountain system. Although scholars have noted that the consensus on the Five Mountain system and their ranks had not concurred until the end of the Southern Song dynasty, it is evident that these mountains enjoyed fame throughout the Song dynasty.

21 Mt. Yandang gained prominence due to the residence of monk Zhenxie Qingliao’s 真歇清了 in the early years of Taiping Xingguo era (976–984). In the Southern Song period, Mt. Yandang was said to have numerous monasteries, with the Nengren monastery 能仁寺 being the most famous one. Wang’s findings suggest that the Southern Song gazetteers registered an increasing number of monasteries on Mt. Yandang, implying that the mountain was a significant Buddhist site during that period (

Wang 2013, p. 131).

The location of Peak Cui cannot be determined because peaks bearing the same name can be found in Suzhou, Kuaiji, and Siming (

Wang 2013, p. 131). Chicheng refers to Mt. Chicheng near Mt. Tiantai. Yunmen refers to Mt. Yunmen, located thirty

li south of Kuaiji, which also houses a Mingjue Cloister.

22 Fahua indicates Mt. Fahua, located twenty-five

li south of Shanyin county 山陰縣, which is home to Tianyi monastery 天衣寺 (

Wang 2013, p. 131). Zhuji Lipu, located to the west of Kuaiji, had several sites dedicated to the worship of Baozhang, as aforementioned. Chifu Dayan could potentially refer to a place near Kuaiji.

Baozhang was said to return to Peak Feilai on Mt. Tianzhu by the end and expressed supreme admiration for its scenery with the verse: “Having traversed four hundred prefectures in China, I found only this place worth wandering.” Interestingly, this line was written for Mt. Lipu in the local gazetteer. This shift reflects the compiler’s intention to emphasize the significance of the Hangzhou region as the new Buddhist center at the time. As the Jiatai pu denglu was an imperial-sanctioned Chan historiography and a formally distributed “historical record” aimed at standardizing the Chan history, this alteration also suggests that Baozhang’s worship, which had been a local cult, was promoted, recognized, and propagated by the state.

Following his previous travels, Baozhang settled at Baoyan in Pujiang, where he developed a friendship with master Xuanlang. Whenever they exchanged letters, Baozhang would dispatch a white dog, and in response, Xuanlang would send a black ape. This correspondence led Baozhang to inscribe a verse on Xuanlang’s wall, which read, “The white dog came with a letter in its mouth. The black ape returned with a washed alms bowl at hand”. Over time, all the places where master Baozhang traveled became esteemed sites of significance.

後居浦江之寶巖,與朗禪師友善。每通問,遣白犬馳往,朗亦以青猿為使令。故題朗壁曰:“白犬㘅書至,青猿洗鉢回。”師所經處,後皆成寶坊。

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434a17–434a19)

Subsequently, Baozhang relocated to Cliff Bao 寶巖 in Pujiang and passed away there. Zhengshou appears to attribute Pujiang as the last residence of Baozhang, possibly explaining the abundance of the sites dedicated to him in Pujiang. However, based on previous analysis, it seems more plausible to consider Pujiang as the birthplace of Baozhang’s cult. This account introduces an additional episode depicting the interactions between Baozhang and Chan master Xuanlang 玄朗. Xuanlang’s hagiography can be found in Zanning’s 讚寧

Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳, where he is portrayed as a devoted ascetic whose lectures could captivate even wild animals such as apes and blind dogs.

23 It is possible that Zhengshou designed the episode of the two masters’ letter exchange based on Zanning’s description. However, in Xuanlang’s account, there is no mention or allusion to Baozhang, the renowned divine monk who had supposedly enjoyed great fame since the Wei and Jin dynasties. This seems to evince that while Baozhang’s legend and worship might have been prevalent in the local area, they had not yet reached the attention of the monk scholars participating in the compilation of the

Song gaoseng zhuan in the early Song dynasty.

After providing a concise overview of Baozhang’s travels, Zhengshou makes the comment that “Over time, all the places where master Baozhang traveled became esteemed sites of significance”. In history, these places gained significance due to the presence of the notable Chan masters. However, the account reverses the causality and gives all the credit to Baozhang, a legendary divine monk. This strategy adopted by the compiler serves to enhance Baozhang’s authority and elevate his status within Chan Buddhism. By bestowing this higher religious authority upon Baozhang, the renowned Chan masters and the sites dedicated to them also obtained a higher reputation. Additionally, it reinforces the superiority of the Chan school over other traditions within the Buddhist landscape.

On the first day of the second year of Xianqing, Baozhang started handcrafting a statue. By the ninth day, the statue was fully formed. He inquired his disciple Huiyun, “Whom does this statue resemble?” Yun replied: “It bears no distinction from you, Master.” Baozhang then proceeded to cleanse himself and change his clothes. Assuming a lotus position, he conversed with Yun: “I have been residing in this world for a thousand and seventy-two years. Now that I am going to depart. Listen to my verse: ‘Originally, there is no existence of life and death. Yet, now, I shall demonstrate life and death to you. Although I depart, my mind will remain. In another lifetime, I shall return.’”

顯慶二年正旦。手塑一像。至九日像成。問其徒慧雲曰。此肖誰。雲曰。與和尚無異。即澡浴易衣。趺坐謂雲曰。吾住世已一千七十二年。今將謝世。聽吾偈曰。本來無生死。今亦示生死。我得去住心。他生復來此。

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434a20–434a23)

The verse recited by Baozhang on his deathbed was also documented by Wang Xin in his records. Therefore, this verse had to be included in Baozhang’s account which is preserved in the Zhong Tianzhu monastery, as well.

At that moment, Baozhang entrusted Huiyun, saying, “Sixty years after my passing, a monk will come to retrieve my relics. Do not refuse him.” With these final words, Baozhang breathed his last. Fifty-four years later, Elder Cifu arrived at the pagoda from Yunmen. He paid reverence to the pagoda and said, “Pagoda, please open your gate”. After a while, the gate of the pagoda truly opened. Baozhang’s bones interlocked as if they were gold. Elder Fu then transported Baozhang’s bones to Mt. Qinwang and built a stupa to enshrine them.

頃時囑曰:“吾滅後六十年,有僧來取吾骨。勿拒。”言訖而逝。入滅五十四年。有刺浮長老自雲門至塔所。禮曰:“冀塔洞開。”少選,塔戶果啟。其骨連環若黃金。浮即持往秦望山,建窣堵波奉藏。

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434a23–434b3)

This account also includes the events after Baozhang’s passing. As Baozhang predicted, master Cifu 刺浮長老 from Mt. Yunmen carried Baozhang’s relics to Mt. Qinwang 秦望山 and erected a monument for him. In the account, the compiler referred to the monk as “Cifu”. It is worth noting that according to the

Jiatai kuaiji zhi, Cifu was a mountain located in the east of Kuaiji, which housed the Mingjue monastery with Baozhang’s pagoda, stele, and Bone-Washing Pond, as previously mentioned. Mt. Yunmen, on the other hand, was in the south of Kuaiji, and it was not part of the same mountain range as Mt. Cifu. The

Yunmen zhilue 雲門志略, compiled during the Ming dynasty, mentions the Mingjue monastery on Mt. Yunmen, which was one of the six divisions of the old Yunmen monastery (

Zhang 2006, p. 27). It also featured a pagoda and Bone-Washing Pond (

Zhang 2006, pp. 50–51). Strikingly, the entry for Mt. Yunmen in the

Jiatai kuaiji zhi does not mention any sites associated with Baozhang. This suggests that the second Mingjue monastery on Mt. Yunmen was very likely constructed after the circulation of the

Jiatai pu denglu. Finally, the author chose Mt. Qinwang, the most famous and highest mountain in the Kuaiji region, as the final resting place for Baozhang’s relics. This brief episode connects Baozhang to three mountains in the Kuaiji area, at least two of which had Baozhang’s sites registered on local gazetteers. This not only demonstrates the influence of Baozhang’s cult in local regions, but also reveals how a religious paradigm, possessing great religious value, becomes assimilated into local culture.

Considering that between the twelfth year of King Weilie of the Zhou dynasty to the second year of Xianqing during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of the Tang dynasty, that was 1072 years, Baozhang had lived in China for more than 400 years. However, none of the Buddhist historiographies ever recorded his story. During the year of Kaiyuan, a monk named Zongyi, who was a disciple of Huiyun, carved Baozhang’s story on a stone tablet.

以周威烈丁卯至唐高宗顯慶丁巳攷之,實一千七十二年。抵此土歲歷四百餘。僧史皆失載。開元中,慧雲門人宗一者,甞勒石識之。

(Zhengshou X. 79, pp. 434b3–434b6)

Huiyun, the only disciple mentioned in Baozhang’s hagiography, was reported to have a disciple named Zongyi 宗一. Unfortunately, no hagiographies for Huiyun or Zongyi have been preserved in existing sources. Nevertheless, an entry in the

Pujiang zhilue 浦江志略, a Ming dynasty gazetteer, is attentive. Under the section of “Stele 碑碣”, there is a record entitled “

Record of Monk Qiansui of Baoyan Cloister by monk Zongyi in the fourth month of the second year of Kaiyuan in the Tang dynasty, 寶嚴院千歲和尚記,唐開元二年四月僧宗一撰.” (

Mao 1981, fasc. 7, p. 7b). It is plausible that Zhengshou read this information in local records and regarded it as substantial evidence when compiling Baozhang’s hagiography.

The incorporation and adaptation of Baozhang’s hagiography in the

Jiatai pu denglu exemplify how a valuable religious paradigm underwent recognition and promotion, transforming from a local cult into an esteemed Buddhist ideal within an imperial-sanctioned Buddhist work. The widespread circulation of the

Jiatai pu denglu afforded Baozhang an opportunity to emerge as a celebrated figure on a national scale. Consequently, his legend found inclusion in many subsequent Buddhist works, while also gaining veneration as a founding patriarch in purportedly affiliated monasteries.

24 Notably, the reason that Baozhang could captivate the attention of the compiler of the

Jiatai pudeng lu was due to his establishment of a popular base within local regions. As his story gained widespread dissemination, individuals were inspired to either construct or designate local sites bearing his name. Moreover, the compiler Zhengshou skillfully integrated locations of significance to the Chan school’s history into Baozhang’s hagiography, embellishing his encounter with Bodhidharma. As a result, Zhengshou capitalized on Baozhang’s intrinsic value to promote the status of the Chan school, thereby validating its superiority over the schools featuring doctrinal teachings.

5. Conclusions

This article commences with two poems by Qiang Zhi, a literatus from the Northern Song era, which are considered the earliest surviving records pertaining to Baozhang. To identify the locations where Qiang visited, I examined various local gazetteers and revealed three distinct clusters of Baozhang-related sites in Pujiang, Zhuji, and Kuaiji. Given Qiang’s prior service in an official post in Pujiang, it is reasonable to infer that the sites mentioned in his poems were located in Pujiang, meaning that the cult of Baozhang had already established a presence in this region before the mid-eleventh century. Later, during the Southern Song period, a “

yimin 遺民” (leftover man) Fang Feng 方鳳 who hailed from Pujiang, documented his visits to Baozhang-related sites in his two poems:

Visiting the Monastery in Mt. Baozhang 遊寶掌山寺 (

Fu 1998, p. 43326) and

Visithing Mt. Baozhang with Gaoyu and Zishan 與皋羽子善遊寶掌山 (

Fu 1998, p. 43335). This attests to the prosperity of Baozhang’s cult within the Pujiang region over several centuries.

Notably, the

Jiatai kuaiji zhi not only offers detailed entries concerning Baozhang’s sites, but also preserves an early version of Baozhang’s account. In this account, Baozhang is portrayed as a “hybrid” figure, embodying both Buddhist and Taoist elements. This amalgamation suggests that this particular version of Baozhang was likely a popular figure within the local culture, as the inconsistencies in his identity remain unresolved, and he had yet to be firmly established as a pure Buddhist model. While Pujiang appears to have been the probable birthplace of Baozhang’s cult, tracing its spread among the three clusters proves to be challenging.

25 What can be determined is that during its dissemination, numerous sites dedicated to Baozhang’s cult were constructed or designated. As a result, various replicas of Baozhang’s sites emerged, such as Baozhang Cliff and Mt. Baozhang in different counties. The replication even occurred within Kuaiji county, with both Mt. Cifu and Mt. Yunmen claiming to have Mingjue monasteries and Baozhang’s steles. This phenomenon demonstrates the captivating appeal of Baozhang as a legendary figure within popular culture, garnering widespread popularity and following. This phase represented the period when Baozhang’s cult was revered in local regions.

It remains unknown the exact timing of the spread of Baozhang’s cult to Hangzhou and the establishment of the connection between Baozhang and the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. However, by the latter half of the twelfth century, Baozhang was already venerated as the founding patriarch of the Zhong Tianzhu monastery. Nevertheless, it is very likely that during this period, Baozhang’s story remained unfamiliar in the capital city. It was through the efforts of abbot Fahua, who seized the opportunity to host a rain praying ceremony, that Baozhang gained recognition among literati. This event played a crucial role in promoting Baozhang’s cult and propagating his story in the Hangzhou region. As Baozhang’s reputation grew, it ultimately led to his inclusion by Zhengshou, the compiler of the Jiatai pu denglu. Zhengshou not only positioned Baozhang as the first figure in the “Yinghua shengxian” section, but also made significant adaptations to Baozhang’s hagiography. An analysis of the text reveals that the author achieved several objectives through his writing: (1) The author removed all Taoist elements and portrayed Baozhang as a devoted Buddhist. (2) The author highlights the significance of Chan Buddhism by incorporating the encounter between Baozhang and Bodhidharma and aligning Baozhang’s travel route with important sites in Chan history. (3) The author emphasizes the Liangzhe region, particularly Lin’an, as the new Buddhist center at the time. (4) The author asserts the superiority of the Chan school and its teachings by depicting Baozhang’s attainment of enlightenment under Bodhidharm’s instruction. (5) The author utilized Baozhang’s fame, in reverse, to honor the Chan masters who made great contributions to the development of the Chan school.

The Jiatai pu denglu, as an imperial-sanctioned denglu work, played a critical role in standardizing the teachings and history of the Chan school. The incorporation of Baozhang into the Jiatai lu thus elevated him from a local popular cult figure to a national precepted Buddhist ideal. Zhengshou’s version of Baozhang’s account subsequently found its way into various Buddhist historiographies, indicating that it helped Baozhang’s story popularize in a wider range.

At last, incorporating Baozhang in the Jiatai pu denglu exemplifies how the state recognized individuals initially revered as popular cult figures in local regions. By examining the figures selected in the “Yinghua shengxian” section in the Jiatai lu, we can observe that the compiler included individuals from more diverse backgrounds, with various divine attributes, and living during the Song dynasty, such as monk Jiuxian Yuxian 酒仙遇賢和尚, Venerable Nan’anyan Ziyan, Mahasattva Fahua Yanzhi 法華言志大士, and True men Zhang Boduan 張伯端真人. This demonstrates that the denglu works went beyond exclusively documenting the teachings and lineages of the Chan school, acknowledging and incorporating popular trends beyond Chan Buddhism. Therefore, a thorough examination of the “Yinghua shengxian” sections provides us with valuable insights and prompts a reevaluation of our understanding and utilization of the Chan denglu works.