Publishing Privileges the Published: An Analysis of Gender, Class, and Race in the Hymnological Feedback Loop

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Challenges in Expanding Musical Diversity in Mennonite Hymnals

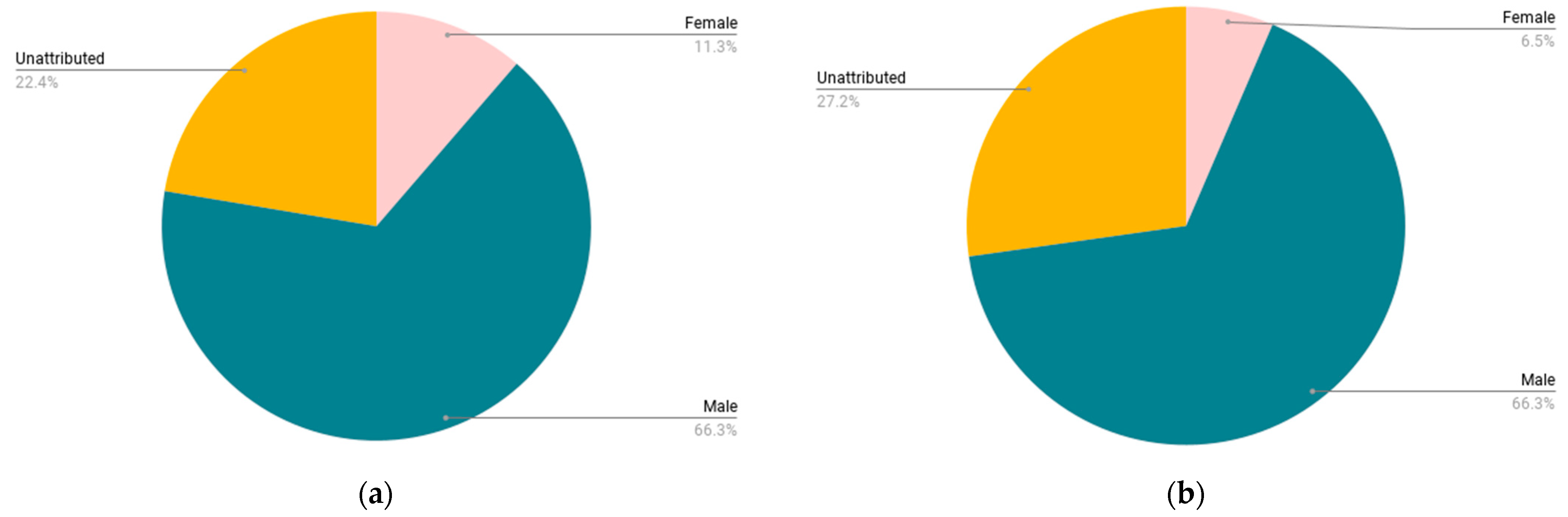

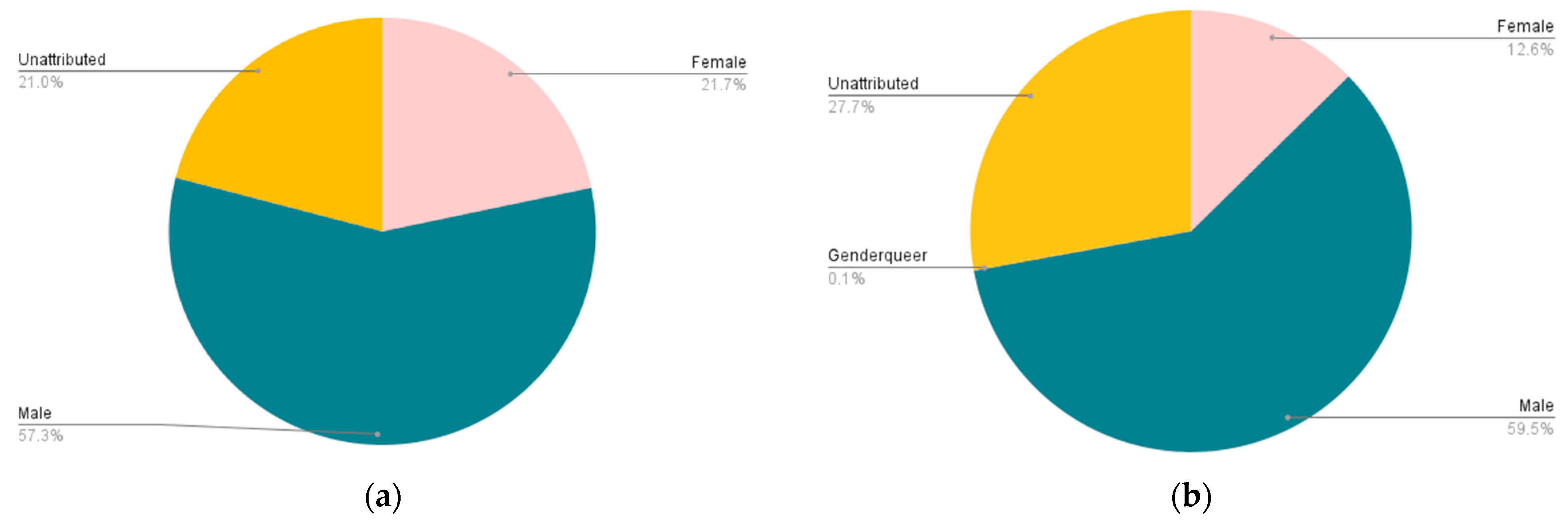

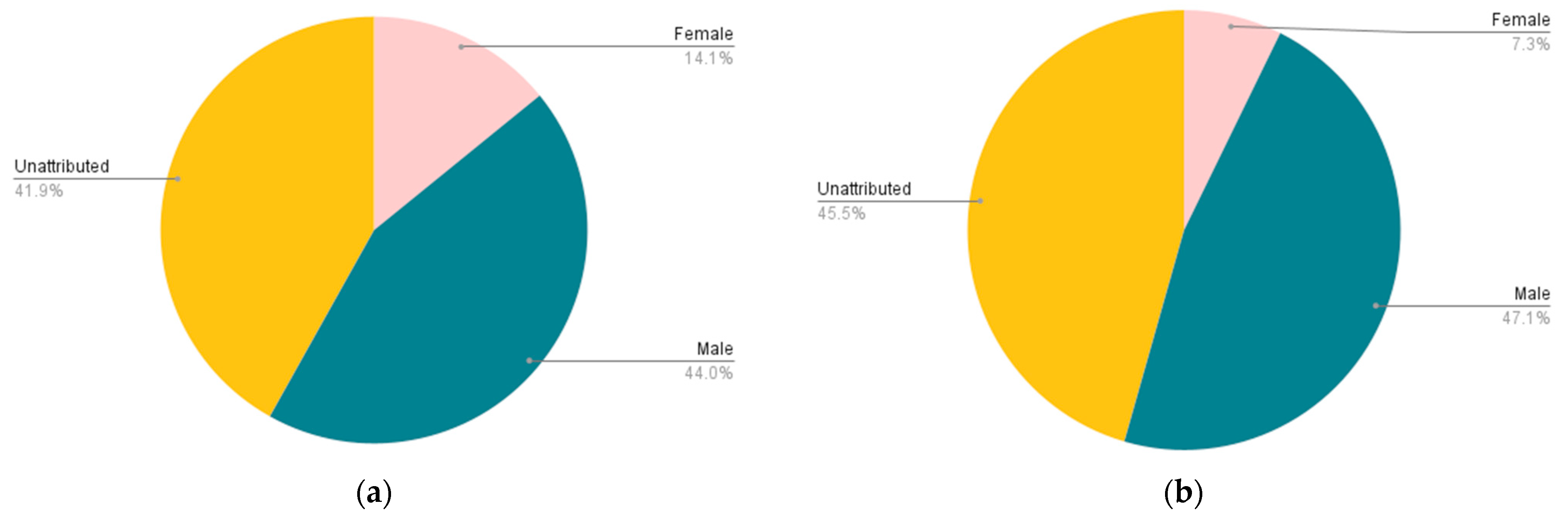

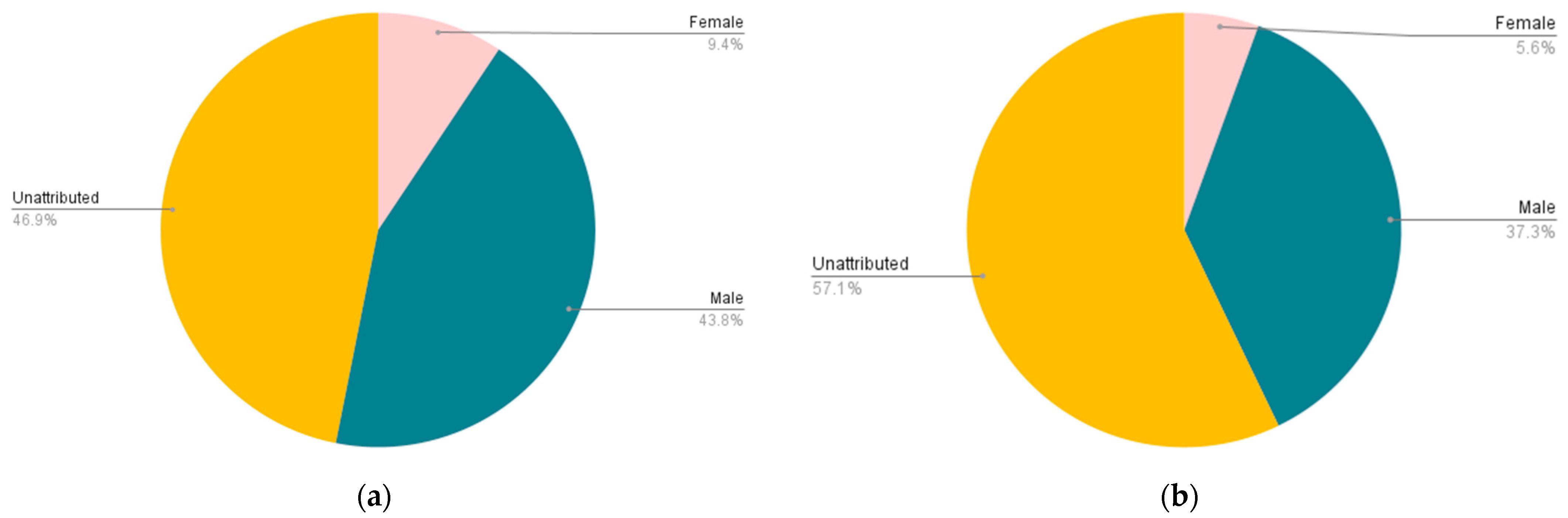

2. Gender Representation in Voices Together

Increasing the Representation of Women Composers in Voices Together

- Sometimes, an inexperienced composer is working toward standard Western compositional practices. If that is the case, they should be given the editorial suggestions needed to strengthen their compositions to align with the conventions to which they aspire.

- Other times, inexperienced composers may contribute a song with one element stronger than the others. In such cases, committees should work with contributors to use the most effective elements, for example, by including their tune paired with a separate text or letting a chorus stand alone.

- In yet other cases, a woman or other underrepresented contributor may be intentionally developing a non-standard compositional style. That also should be valued, encouraged, and edited toward the contributor’s goals.

3. Global Song and Gender Representation in Voices Together

The Trouble with Equating “Global Song” and “Traditional Music”

- Non-English songs in Voices Together, including songs originally written in languages other than English, as well as songs with added translations.20 This list includes all non-English languages, including European languages like French, German, and Latin.

- Songs identified as important to African American traditions by our consultant group. This list includes not only songs by African American composers (in a variety of styles), but also several written by white Americans and Europeans.21

- Songs with connections to Indigenous communities. This includes songs written or received by Indigenous people, one song written by white people in collaboration with Indigenous people, and one song with a Navajo translation.22

- African American—22 (17 listed as spirituals and 5 as traditional)

- Africa—22

- Europe—14 (including 3 Taize songs; while some Taize songs are ascribed to Jacques Berthier, many are credited to the community at large and thus labeled unattributed)

- Native American—8

- Latin America—8

- Asia—8

- Middle East—2 (both are Hebrew language)

- Caribbean—2

- Traditional Orthodox liturgy (Russia)—1

4. Discussion: Identifying and Challenging Implicit Bias in Song Selection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In addition to the authors, committee members included Bradley Kauffman (project director and general editor), Benjamin Bergey (music editor), Sarah Kathleen Johnson (worship resources editor), Adam Tice (text editor), Darryl Neustaedter Barg, Paul Dueck, Mike Erb, Emily Grimes, Tom Harder, SaeJin Lee, Cynthia Neufeld Smith, and Allan Rudy-Froese. For an analysis of power dynamics in the construction and usage of Voices Together see Johnson (2023). |

| 2 | We use the admittedly inadequate phrase “traditional Western hymnody” in this paper to describe hymnody that is typically written in four-part harmony, has several verses or stanzas, and is musically and poetically influenced by art music from Europe in the common practice era (1600–1900). Here, it is distinguished from expressions like contemporary worship music, Catholic folk, gospel traditions, and other newer forms. See Hawn (2015) for examples of recent expressions of congregational song. |

| 3 | Our analysis has interesting parallels to Andrew Mall’s exploration of the circulation of contemporary worship music. In both cases, economic forces are present but not the only capital involved; Mall writes, “Writers following the Bourdieuian tradition are concerned less with the accumulation of economic capital and more with the presence, power, and influence of symbolic capital within specific sociocultural contexts. Thus, concepts of ‘religious capital’ (Bourdieu 1991), ‘sacred capital’ (Urban 2003), ‘spiritual capital’ (Verter 2003), and ‘worship capital’ (Mall 2018b) all capture slightly different understandings of how religious institutions, leaders, and congregants manipulate and navigate power hierarchies in religious contexts through the acquisition and divestment of symbolic capital” (Mall 2021, p. 130). |

| 4 | These numbers have been in flux for at least two decades; a close approximation from recent years can be found in the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, under “Mennonite Church USA” and “Mennonite Church Canada” (Mennonite Church USA n.d.; Mennonite Church Canada n.d.). |

| 5 | We prefer to leave this number as an approximation to reflect the difficulty of assessing “exclusive” or “new” publication—some songs in Voices Together previously existed as recordings or choral arrangements, and some may have been informally printed and circulated. |

| 6 | For more on Voices Together’s 759 songs and 310 worship resources (which include visual art and words for worship); see the Voices Together website (especially Guide to Adopting Voices Together 2020). This article will analyze statistics related to the songs; for more on non-musical worship resources; see Johnson (2020). |

| 7 | For more information on how songs and worship resources were chosen for inclusion in Voices Together, including a full list of these consulting groups, see (How Songs Were Chosen for Voices Together 2020). A submissions process is typical for many denominational hymnals and is often publicized among similar circles of hymn writers and composers. Significantly for this article, the Voices Together submission portal included space for the author/composer to state whether they identify as Anabaptist and their gender identity, but not their race/ethnicity. |

| 8 | In Hymnal: A Worship Book, 65% of single-author resources are written by women (24% of the total number of spoken resources in the collection, which is contrasted with 13% written by men). In Voices Together, by contrast, 53% of single-author resources are written by women (or 20% of the spoken resources, compared to the 18% written by men) (Johnson 2022). |

| 9 | Other balance considerations included theological perspectives and themes; style, length, and difficulty of music; languages and regions represented; and more. |

| 10 | Kyra Gaunt describes these circumstances in music and the discipline of ethnomusicology: “The monopoly of White, heteronormative privilege and bias is intangible; we do not see it and rarely acknowledge it. Bias shows up in the silent and persistent erasure of indifference to anti-Black racism and sexism in our culture” (Gaunt 2022, p. 39). We will expand on these ideas later in this article, along with Philip Ewell’s (2020) incisive analysis of this phenomenon. |

| 11 | Notably, these numbers are comparable with other similar collections. An unpublished study of the United Methodist Hymnal (1989) and Evangelical Lutheran Worship (2006) by Hannah Porter Denecke shows similar figures, though her approach was slightly different as she did not account for unattributed resources. She found that women composers represent 14% of the United Methodist Hymnal, and 13% of Evangelical Lutheran Worship (percentages that would surely be lower if unattributed resources were accounted for) (Porter Denecke 2018). |

| 12 | We realize that musical expectation is an unwieldy subject with nuances related to genre, style, musical culture, and more, and we argue that hymnal publishers and committees need to be aware of how these preferences affect inclusion in collections. |

| 13 | An example of this additional work includes Graber writing a new text for a standalone tune in an irregular meter that was submitted by an Anabaptist woman. The final result appears in Voices Together as “Still My Soul” (VT 603). |

| 14 | To experience some of these songs and to learn more about them, see (Loepp Thiessen 2021). |

| 15 | Ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl notes that the term “world music” arose in academia in the 1960s “to mean a curriculum in which, theoretically, all the music in the world could be studied …—well, perhaps excluding Western art music, which usually doesn’t get into those books and courses because it has books and courses of its own. So music was divided into the West, and its ‘real’ music, and ‘the rest’, or world music” (Nettl 2010, p. 34). For another analysis of scholarly and commercial uses of these terms, see Taylor (1997). Becca Whitla (2020) gives a succinct summary in relation to church music (p. 17), and Marissa Glynias Moore’s (2018) dissertation is an in-depth study. |

| 16 | For example, “I Have Decided to Follow Jesus” is often received and sung as a Western folk tune. It is ascribed in Voices Together as “Indian traditional”, though more recent scholarship indicates it was written by Simon Kara Marak, a missionary and pastor from Assam, India (Hawn 2020). Another example is “Way Maker” by Nigerian songwriter and worship leader Sinach, which has often been detached from its intercultural origins (Loepp Thiessen 2023). |

| 17 | In the blog post “Why and how should we sing interculturally?” Graber (2020c) explains to a presumed white Mennonite readership why Voices Together includes non-Western and non-English material. The Voices Together Worship Leader Edition (Johnson 2020) includes related essays, “Worship and Culture” (#28) and “Worship in Multiple Languages” (#29). |

| 18 | For a partial list of collections reviewed by the Voices Together Intercultural Committee, see (Graber 2020c). For more on gatekeeping processes in the North American singing of global congregational song, see (Lim 2016; Glynias Moore 2018). A testament to the recognition of this need for intercultural engagement in North American hymnody came in the form of a Vital Worship Grant from the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, with funds provided by Lilly Endowment, Inc., that allowed several committee members to visit ten Mennonite congregations across the U.S. and Canada that worship in languages other than English. |

| 19 | For example, the contemporary worship song “Tú estás aquí (My God is Here)” (VT 67), written by Michael Rodríguez (Puerto Rico) and Jesús Adrián Romero (Mexico) in Spanish, is included along with the traditional-sounding El Salvadoran song “Santo, santo, santo (Holy, Holy Holy)” (VT 102) by Guillermo Cuellar with sesquialtera 6/8–3/4 meter changes and the unattributed Guatemalan traditional song La paz de la tierra (The Peace of the Earth Be with You) (VT 838). |

| 20 | For example, the 22 songs in German: some were written in German in past centuries but are now better known in English, e.g., “Heilig, heilig, heilig (Holy, Holy, Holy)” (VT 137) written in 1826; some have been beloved in German-speaking Mennonite communities in North America into the 21st century, e.g., “Gott ist die Liebe (I Know God Loves Me)” (VT 158). Some German songs were recently written in Germany, e.g., “Herr, füll mich neu (Fill Me Anew)” (VT 739) written in 2004, and one contemporary worship song was included with German because it also appears in a German Mennonite hymnal in South America, “Here I Am to Worship (Ich will dich anbeten)” (VT 227). |

| 21 | For example, “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” (VT 160). |

| 22 | For example, “There’s a River of Life” by Indigenous songwriter Jonathan Maracle (VT 24); “Creation is a Song” (VT 181) by white Mennonite songwriters Doug Krehbiel and Jude Krehbiel; and Navajo language was added to “I Have Decided to Follow Jesus” because a Mennonite contact indicated that it is often sung in Navajo communities. |

| 23 | For example, “folk” has a history associated with Johann Gottfried Herder and the development of evolutionary thinking and biological racism, and “unknown” implies the question “unknown to whom?”. |

| 24 | Examples of these musical features include “Jesus A Nahetotaetanome (Jesus Lord, How Joyful)” (VT 8), which is unison a capella with a wide, falling vocal range and an irregular meter that follows the Cheyenne text, and “Ngayong nagdadapit hapon (When Twilight Comes)” (VT 501) with phrase lengths of 8, 6, and 4 measures. |

| 25 | Nettl (2010) explains how numbers 2 and 3 are connected, writing that two assumptions are often present (and sometimes debated) in music scholarship: “(1) all peoples have a distinct music, or (2) all music is part of a single development leading to—well, is it Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, or high-tech?” (Nettl 2010, p. 41). If both are believed to be true, then the implication is that each peoples’ distinct music is on an evolutionary path toward Western art music. |

| 26 | For an extended exploration of the value we place on music, see (Cheng 2020). He writes, “Western art music has long served ambitions to colonize land, educate ‘noble savages’, edify children, and, increasingly today, rehabilitate prisoners” (p. 11). |

| 27 | These nuanced ways of understanding and endorsing the Western classical canon have also proved a barrier for women to enter the compositional style: Anneli recalls a piano lesson in which she was working on a Baroque piano piece by a woman. The instructor consistently observed places where the composer had gotten it “wrong” because she did not follow the classical signposts of her male counterparts. A better way to explain her music, in fact, is that her composition had not been analyzed and integrated in centuries of studies that explained how compositions should work. |

| 28 | A fuller quotation of Nekola’s description of Garlock and his contemporary Bob Larson makes these connections even more evident. She writes: “For both Larson and Garlock, rock ‘n’ roll’s ‘heathen’ roots were dangerous for two key reasons: the rhythm was connected to illegitimate religious practices, and the rhythm inspired the body to act without reason and in fulfillment of demonic desire. For example, Larson explained to his readers that the dangerous beat of rock ‘n’ roll came directly from ‘heathen tribal and voodoo rites’: ‘The native dances to incessant, pulsating, syncopated rhythms until he enters a state of hypnotic monotony and loses active control over his conscious mind. The throb of the beat from the drums brings his minds to a state when the voodoo, which Christian missionaries know to be a demon, can enter him. This power then takes control of the dancer, usually resulting in sexual atrocities.’ (Larson 1970, p. 130). Similarly, Garlock claimed that: ‘All one needs to do is make a trip to the places where rock ‘n roll has its roots (Africa, South America, and India) and observe the ceremonies which often go along with this kind of music—voodoo rituals, sex orgies, human sacrifice, and devil worship—to know the direction in which we as a nation are headed.’ (Garlock 1971, p. 22).” (Nekola 2013, p. 414). |

| 29 | The authors are working on projects like these, including the Anabaptist Worship Network (Anabaptist Worship Network n.d.), which hosted a songwriting retreat supported by the Calvin Institute for Christian Worship, with funds provided by the Lilly Endowment Inc. Several of the songs from the retreat are now available online on the Together in Worship website (Together in Worship n.d.), having been refined through peer feedback, and recorded and notated in order to be easily accessible to congregations. You can find examples here: https://togetherinworship.net/Browse/10368, accessed on 4 October 2023. |

References

- About MWC. n.d. Mennonite World Conference. Available online: https://mwc-cmm.org/en/about-mwc (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. White Men. Feministkilljoys (blog). November 4. Available online: https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/11/04/white-men/ (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Albrecht, Elizabeth Soto, and Darryl W. Stephens, eds. 2020. Liberating the Politics of Jesus: Renewing Peace Theology through the Wisdom of Women. T & T Clark Studies in Anabaptist Theology and Ethics. London: T & T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Anabaptist Worship Network. n.d. Available online: https://www.anabaptistworship.net/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Becker, Judith. 1986. Is Western Art Music Superior? The Musical Quarterly LXXII: 341–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bederman, Gail. 1995. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, John L. 2001. The Singing Thing. Chicago: GIA Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Boldt, John, and Glenn Musselman, eds. 1972. Mennonite World Conference Songbook. Curitiba: Mennonite World Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Deb. 2022. Antiracism and Your Music Ministry. Presentation for United in Learning: Music United, online. January 12. [Google Scholar]

- Browner, Tara. 1997. ‘Breathing the Indian Spirit’: Thoughts on Musical Borrowing and the ‘Indianist’ Movement in American Music. American Music 15: 265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budwey, Stephanie A. 2022. Religion and Intersex: Perspectives from Science, Law, Culture, and Theology. Routledge New Critical Thinking in Religion, Theology and Biblical Studies. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, Anna. 2019. Class, Control, and Classical Music. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, William. 2020. Loving Music Til It Hurts. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Citron, Marcia J. 1993. Gender and the Musical Canon. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discipleship Ministries. n.d. Hymns by Women. Available online: https://www.umcdiscipleship.org/resources/hymns-by-women (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Doubleday, Veronica. 2008. Sounds of Power: An Overview of Musical Instruments and Gender. Ethnomusicology Forum 17: 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dueck, Jonathan. 2013. Making Borrowed Songs: Mennonite Hymns, Appropriation and Media. In Christian Congregational Music: Performance, Identity and Experience. Edited by Monique Ingalls, Carolyn Landau and Tom Wagner. New York: Routledge, pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Eastburn, Susanna. 2017. We Need More Women Composers—And It’s Not about Tokenism, It’s about Talent. The Guardian. March 6. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/mar/06/sound-and-music-susanna-eastburn-we-need-more-women-composers-talent-not-tokenism (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Ewell, Philip. 2020. Music Theory and the White Racial Frame. Music Theory Online, 26. Available online: https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.2/mto.20.26.2.ewell.html (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Gaunt, Kyra. 2022. Diversity on Repeat: The Deceptive Cadence of Social Domination in Ethnomusicology. In At the Crossroads of Music and Social Justice. Edited by Brenda M. Romero, Susan M. Asai, David A. McDonald, Andrew G. Snyder and Katelyn E. Best. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Glynias Moore, Marissa. 2018. Voicing the World: Global Song in American Christian Worship. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Graber, Katie. 2020a. Mennonite Voices. American Religious Sounds Project Gallery, Lauren Pond, Producer. Available online: https://gallery.religioussounds.osu.edu/mennonite-voices/ (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Graber, Katie. 2020b. White as Snow: Race and Church Music. Anabaptist Worship Network (blog). October 17. Available online: https://www.anabaptistworship.net/blog/blog-post-title-four-ld457 (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Graber, Katie. 2020c. Why and How Should We Sing Interculturally? Menno Snapshots (blog), MCUSA. January 23. Available online: https://www.mennoniteusa.org/menno-snapshots/why-and-how-sing-interculturally/ (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Green, Lucy. 1997. Music, Gender, Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guide to Adopting Voices Together. 2020. Harrisonburg: Mennomedia. Available online: http://voicestogetherhymnal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Guide-to-Adopting-Voices-Together-download.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Hadden Hobbs, June. 1997. I Sing for I Cannot Be Silent: The Feminization of American Hymnody, 1870–1920. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawn, Michael. 2015. New Songs of Celebration Render: Congregational Song in the 21st Century. Chicago: GIA Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hawn, Michael. 2020. History of Hymns: ‘I Have Decided to Follow Jesus’. Discipleship Ministries. June 10. Available online: https://www.umcdiscipleship.org/articles/history-of-hymns-i-have-decided-to-follow-jesus (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Hiebert, Clarence, and Rosemary Wyse, eds. 1978. World Conference Songbook. Wichita: Mennonite World Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa, Felipe. 2014. Latino Mennonites: Civil Rights, Faith, and Evangelical Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- How Songs Were Chosen for Voices Together. 2020. Harrisonburg: Mennomedia. Available online: http://voicestogetherhymnal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/How-Songs-and-WR-Chosen-for-Voices-Together-infographic.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Hymnal: A Worship Book. 1992. Scottdale: Mennonite Publishing Network.

- Johnson, Sarah Kathleen. 2022. The Problem of Mennonite Worship Leadership Becoming ‘Women’s Work’. Vision: A Journal for Church and Theology 23: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sarah Kathleen. 2023. The Power of Naming Power: Domination, Resistance, Solidarity: An Analysis of Power in the Making of a Mennonite Worship Book. In Worship and Power: Liturgical Authority in Free Church Traditions. Edited by Sarah Kathleen Johnson and Andrew Wymer. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sarah Kathleen, and Adam Tice. 2022. Our Journey with Just and Faithful Language: The Story of a Twenty-First Century Mennonite Hymnal and Worship Book. The Hymn 73: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sarah Kathleen, and Anneli Loepp Thiessen. 2023. Contemporary Worship Music as an Ecumenical Liturgical Movement. Worship 98: 204–29. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sarah Kathleen, ed. 2020. Worship Leader Edition, Voices Together. Harrisonburg: MennoMedia. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Swee Hong. 2016. World Christianity and World Church Music: Singing the Lord’s Song in a World Church. In World Christianity: Perspective and Insights. Edited by Jonathan Y. Tan and Anh Q. Tran. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, pp. 338–53. [Google Scholar]

- Loepp Thiessen, Anneli. 2021. Still Singing—Women Composers and the Voices Together Hymnal. Noon Hour Concert at Conrad Grebel University College, January 27. Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/grebel/events/noon-hour-concert-still-singing-women-composers-and-voices (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Loepp Thiessen, Anneli. 2022. Boy’s Club: A Gender Based Analysis of the CCLI Lists from 1988–2018. Journal of Contemporary Ministry 6: 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Loepp Thiessen, Anneli. 2023. Establishing Best Practices for Intercultural Contemporary Worship Music: A Case Study of ‘Way Maker’ by Sinach. The Hymn 74: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mall, Andrew. 2021. Political Economy and Capital in Congregational Music Studies: Commodities, Worshipers, and Worship. In Studying Congregational Music: Key Issues, Methods, and Theoretical Perspectives. Edited by Andrew Mall, Jeffers Engelhardt and Monique M. Ingalls. London: Routledge, pp. 123–38. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, Gerardo. 2012. Worship across the Racial Divide: Religious Music and the Multiracial Congregation. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe Juhnke, Austin. 2018. Music and the Mennonite Ethnic Imagination. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe Juhnke, Austin. 2019. The Lawndale Choir: Singing Mennonite from the City. Mennonite Quarterly Review 3: 309–33. [Google Scholar]

- McClary, Susan. 1991. Feminine Endings. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, Andrew Clay. 2023. Music as Ethics: Stories from Virginia. American Musicspheres. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mennonite Church Canada. n.d. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Available online: https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mennonite_church_canada (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Mennonite Church USA. n.d. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Available online: https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mennonite_church_usa (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Mosley, Paul, and Rebecca Mosley. 2013. Give Us Courage for the Journey–GLI 2013. Paul and Rebecca Mosley in Burundi (blog). January 31. Available online: http://pamosley.blogspot.com/2013/01/give-us-courage-for-journey-gli-2013.html (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Nekola, Anna. 2013. ‘More than Just a Music’: Conservative Christian Anti-rock Discourse and the U.S. Culture Wars. Popular Music 32: 407–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettl, Bruno. 2010. Nettl’s Elephant: On the History of Ethnomusicology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhoff, Krissy. 2020. Writing Worship: How to Craft Heartfelt Songs for the Church. Colorado Springs: David C Cook. [Google Scholar]

- Penner, Carol. 2019. Women Moving into Ministry: A Canadian Mennonite Press Survey. Journal of Mennonite Studies 37: 159–77. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Christopher N. 2018. The Hymnal: A Reading History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani, Michael. 2005. Imagining Native America in Music. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Denecke, Hannah. 2018. Final Project Findings. Unpublished paper for Survey of Hymnody class, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA. April 30. [Google Scholar]

- Previous Assemblies. n.d. Mennonite World Conference. Available online: https://mwc-cmm.org/en/previous-assemblies (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Procter-Smith, Marjorie. 1990. In Her Own Rite: Constructing Feminist Liturgical Tradition. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schlitz, Paul, Jr. 2023. Letter to the Editor: A Dying Art Form? Anabaptist World. May 24. Available online: https://anabaptistworld.org/a-dying-art-form/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Sing the Journey. 2005. Scottdale: Mennonite Publishing Network.

- Sing the Story. 2007. Scottdale: Mennonite Publishing Network.

- Smith, Christen A. 2017. Cite Black Women. Available online: https://www.citeblackwomencollective.org/our-collective.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Stace Vega, April. 2014. Musical Genre and Liturgical Spirituality. Worship 87: 444. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Timothy D. 1997. Global Pop: World Music, World Markets. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- The Hymn Society. n.d. Publications. Available online: https://thehymnsociety.org/publications/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- The Mennonite Hymnal. 1969. Scottdale: Herald Press. Newton: Faith and Life Press.

- Together in Worship. n.d. Available online: togetherinworship.org (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Van Opstal, Sandra. 2016. The Next Worship: Glorifying God in a Diverse World. Downers Grove: IVP Books. [Google Scholar]

- Voices Together. 2020. Harrisonburg: MennoMedia.

- Wallaschek, Richard. 1893. Primitive Music: An Inquiry into the Origin and Development of Music, Songs, Instruments, Dances, and Pantomimes of Savage Races. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Jada. 2020. Reproducing Inheritance: How the Country Music Association’s Award Criteria Reinforce Industry White Supremacy Capitalist Patriarchy. American Music Perspectives 1: 136–50. [Google Scholar]

- Weidler, Scott, Robert Farlee, and Mark Sperle-Weiler, eds. 2017. Singing in Community: Paperless Music for Worship. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, Regina. 2021. History Against Hierarchy: Ruth Brunk Stoltzfus and Women’s Leadership in the Mennonite Church. Anabaptist Historians (blog). May 14. Available online: https://anabaptisthistorians.org/2021/05/14/history-against-hierarchy-ruth-brunk-stoltzfus-and-womens-leadership-in-the-mennonite-church/ (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Whitla, Becca. 2020. Liberation, (de)Coloniality, and Liturgical Practices: Flipping the Song Bird. New Approaches to Religion and Power. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton, Janet. 2010. This Is Our Song: Women’s Hymn-Writing. London: Epworth. [Google Scholar]

| Ewell’s White Racial Frame in Music Theory (from Ewell 2020) | Graber and Loepp Thiessen’s White Racial Frame in Hymnody |

|---|---|

| The music and music theories of white persons represent the best, and in certain cases the only, framework for music theory. | Hymnody written by white people has historically made up our framework for evaluating the quality of congregational song. |

| Among these white persons, the music and music theories of whites from German-speaking lands of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early-twentieth centuries represent the pinnacle of music-theoretical thought. | Hymnody written by white people from German- (and English-) speaking lands of the 18th to early 20th centuries has been upheld as the pinnacle of congregational song output and the standard to which new compositions are held. |

| The institutions and structures of music theory have little or nothing to do with race or whiteness, and that to critically examine race and whiteness in music theory would be inappropriate or unfair. | Since hymnody is about worship, it has been considered inappropriate to examine race or whiteness in congregational song. Limitations of race and gender have been overlooked since what has mattered most is finding material that helps people worship God. |

| The best scholarship in music theory rises to the top of the field in meritocratic fashion, irrespective of the author’s race. | The best hymnody is presumed to have risen to the top of the field in meritocratic fashion, irrespective of the author’s race or gender. |

| The language of “diversity” and “inclusivity” and the actions it effects will rectify racial disparities, and therefore racial injustices, in music theory. | The inclusion of global song will rectify racial disparities, and therefore racial injustices, in church music. Because of this, it is unnecessary to interrogate the race and gender of songwriters further so long as global songs are included. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graber, K.; Loepp Thiessen, A. Publishing Privileges the Published: An Analysis of Gender, Class, and Race in the Hymnological Feedback Loop. Religions 2023, 14, 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101273

Graber K, Loepp Thiessen A. Publishing Privileges the Published: An Analysis of Gender, Class, and Race in the Hymnological Feedback Loop. Religions. 2023; 14(10):1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101273

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraber, Katie, and Anneli Loepp Thiessen. 2023. "Publishing Privileges the Published: An Analysis of Gender, Class, and Race in the Hymnological Feedback Loop" Religions 14, no. 10: 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101273

APA StyleGraber, K., & Loepp Thiessen, A. (2023). Publishing Privileges the Published: An Analysis of Gender, Class, and Race in the Hymnological Feedback Loop. Religions, 14(10), 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101273