The Dhāraṇī Coffin from the Nongso Tomb and the Cult of Shattering Hell during the Koryŏ Dynasty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

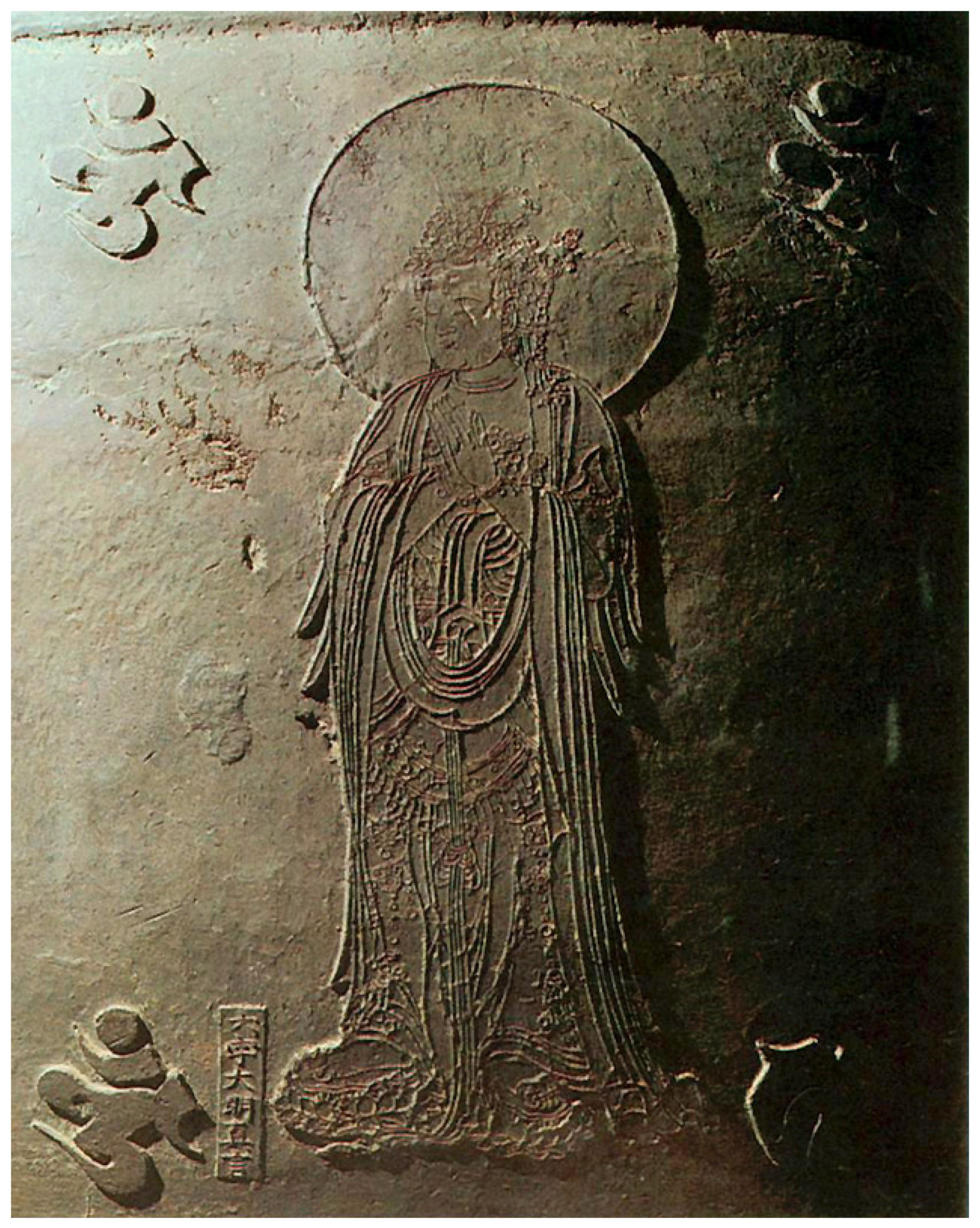

2. Some Aspects of the Liao Funerary Dhāraṇīs

3. Buddhist Perspective on the Netherworld and Funerary Dhāraṇīs of the Koryŏ

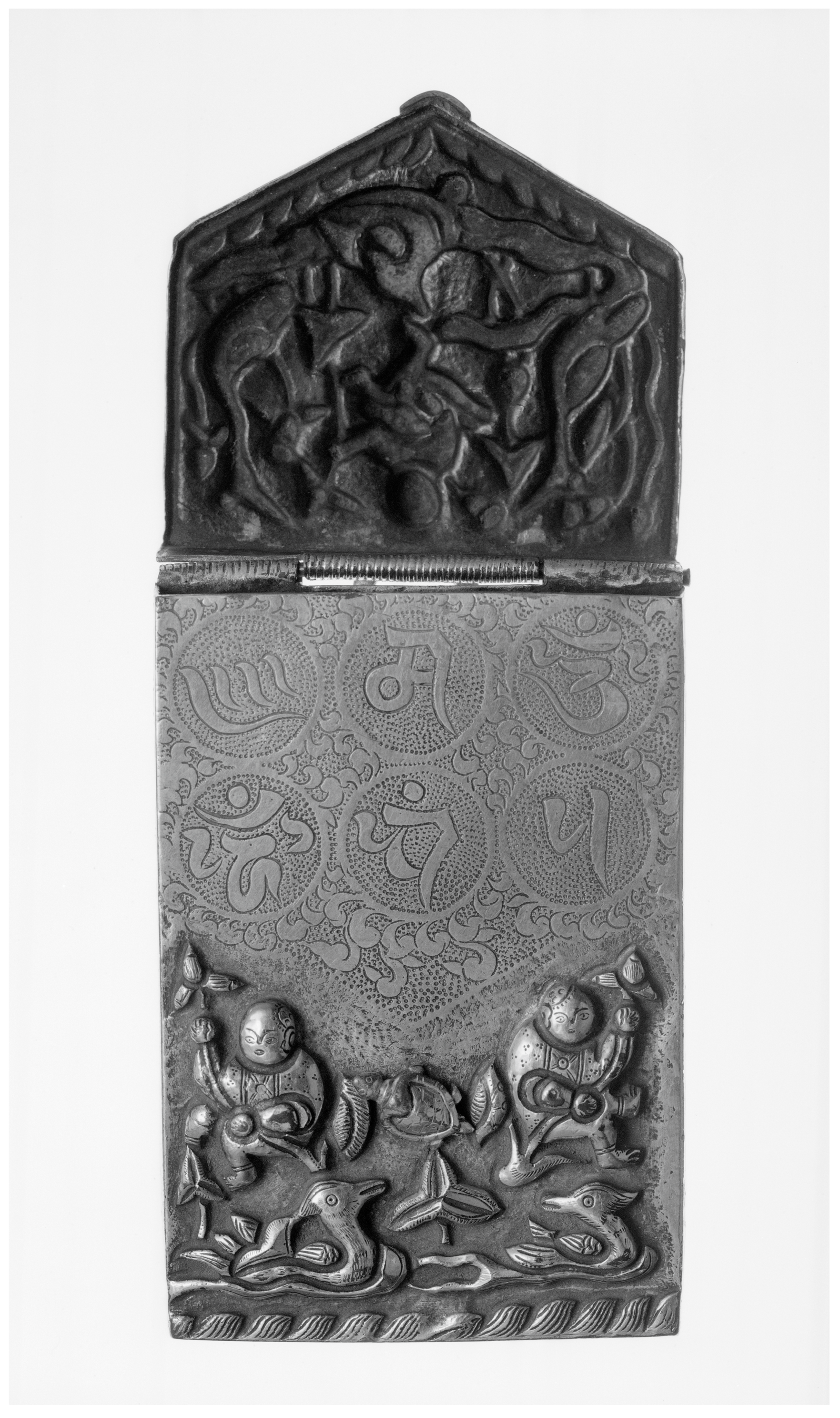

4. Dhāraṇī Coffin of Nongso Tomb and the Cult of Shattering Hell

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭, ed. 1924–1935. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大蔵経. 85 vols. Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai 大正一切経刊行会. Additionally, available online: https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2012/index.html (accessed on 17 October 2022). |

| X Maeda Eun 前田慧雲 and Nakano Tatsue 中野達慧, ed. 1905–1912. Dai Nihon zokuzōkyō 大日本續藏經. 150 vols. Kyoto: Zokyō shoin. Reprint, Taipei: Xinwenfeng chuban gongsi, 1988. Available online: http://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/ (accessed on 17 October 2022). |

| 1 | Liu Shu-fen’s influential study (S. Liu 2003), together with her two related articles (S. Liu 1996, 1997), was republished as a book. In what follows, I cite from the book for reasons of efficiency. See (S. Liu 2008). |

| 2 | The term “po diyu” or “p’a chiok” 破地獄 is often translated as “breaking hell” in English language scholarship. The use of “breaking” with “hell” might be misleading since it seemed to suggest that the destruction was permanent. Instead, I opt for “shattering” in this article since it implied that hell would be ruptured without implying that this rupture was permanent. |

| 3 | Traditionally, the inner coffin, which held the corpse, was placed inside an outer coffin (kwak 槨). The outer coffin had already decomposed by the time of the tomb’s discovery. Unless otherwise noted, the coffin from the Nongso Tomb, or the Nongso coffin, refers to fragments of the inner coffin. |

| 4 | There is also a study on the method of production for the wooden coffin. See (H. Yi 2017). |

| 5 | This view is in line with (S. Yi 2018, pp. 286–91). |

| 6 | Sutra pillars were usually made of stone and multi-sided—octagonal in most cases—with a considerable height. Since the space for inscription was relatively abundant, the sutra text could have been engraved in its entirety (S. Liu 2008, p. 52). |

| 7 | See the entry “Niutuo si jingchuang” 牛頭寺經幢 in fascicle 67 of Yidu xian tuzhi 益都縣圖志. See also (Kuo 2014) for more on this case. |

| 8 | “Longhua si ni Wei Qiyi zunsheng chuang ji” 龍花寺尼韋契義尊勝幢記 in fascicle 47 of Baqiongshi jinshi buzheng, see (Lu 1925, vol. 27, pp. 11–13). |

| 9 | See the entry “Xue Chou zunsheng chuang ji” 薛籌尊勝幢記 in fascicle 48 of Baqiongshi jinshi buzheng, see (Lu 1925, vol. 27, p. 14). The entry does not mention Dhāraṇī of the Heart of the Great Compassionate One. However, it must have been engraved together, considering that the votive inscription referred to this as the “pillar with Uṣṇīṣavijayā Dhāraṇī and the Great Compassionate One” (Foding zunsheng Dabei chuangzi 佛頂尊勝大悲幢子). |

| 10 | For more on such Liao examples, see (Xiang 1995, pp. 538, 549, 605). |

| 11 | The following discussion is indebted to Zhang Mingwu’s comprehensive study. See (M. Zhang 2013, pp. 102–32). For more on Collected Essentials on Attaining Buddhahood, see (Chŏng 2012, pp. 219–42). |

| 12 | T 1955, 46: 994a13–998a25. The incantations listed in this section are often inscribed on bronze mirrors postdating the Yuan 元 (1271–1368) period. See (Pak 2017, pp. 150–56). |

| 13 | T 1955, 46: 1005b2-5. See (M. Zhang 2013, pp. 105–13). |

| 14 | Given that the coffin bears an inscription dated to 1107 (Jiantong 2), it appears that the builders of the tomb buried the stele, which had been previously made, in the tomb for the repose of the deceased (Datong shi wenwu chenlieguan 1963, pp. 432–33). |

| 15 | For comprehensive studies of extant examples of the Mahāpratisarā Dhāraṇī from the Tang and Song, see (Ma 2004; L. Li 2008; and Copp 2014, pp. 59–140). |

| 16 | See (M. Zhang 2013, p. 147). For the source of the quoted passage, see T 1955, 46: 1005b19–20. |

| 17 | T 1002, 19: 606b22–29. |

| 18 | Being of three different generations, Zhang Kuangzheng, Zhang Wenzao, and Zhang Shiben died at different times; yet, all were buried in 1093. Their descendant, Zhang Shiqing, seems to have planned the construction of the cemetery and buried them afterwards. The discussion above is based on the following sources, see (Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 2001, vol. 1, pp. 4–7, 308–9). See (Q. Li 2008) for a comprehensive discussion of the Liao tombs at Xuanhua. |

| 19 | The tombs of Zhang Kuangzheng and Zhang Wenzao, in which their wives had also been buried, yielded two statues made of straw, respectively. The tomb of Zhang Shiqing—who was buried alone—yielded a statue made of cypress wood. The two statues from Zhang Wenzao’s tomb, though heavily damaged at the time of discovery, originally wore clothes, shoes, and accessories (Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 2001, vol. 1, pp. 89–90). It is notable that such manikins were found in tombs of the Han Chinese, who chose to cremate their body. This has led scholars to conclude that the manikin burial was an amalgam of the Buddhist cremation and the Chinese traditional burial customs. In particular, Wu Hung’s discussion of such burial is worth noting: given that such burial custom has yet to be reported from tombs of the Han Chinese under Song rule, it might have symbolized the ethnic identity of the Han Chinese in the geopolitical context of the Liao (Wu 2010, p. 140). The funerary artifacts, excavated from Tomb No. 1 at the Xiabali Site II in 1998, are intriguing since they clearly show the difference in funerary customs of the Han and Khitan under Liao rule. Archaeologists found the body of a Khitan man, clad in metal wire clothes, and two manikins of his Han Chinese wives (H. Liu 2008, pp. 14–22). Such manikin burial customs seem to have formed as different burial customs and religious beliefs were fused. On the one hand, the practice of making an “ash-body icon” (Ch. huishen xiang 灰身像) of an eminent monk, which enjoyed popularity during the Tang, has been singled out as one of the possible origins for the manikin burial. The ash-body icon, which portrayed a likeness of the deceased in a naturalistic manner, was made of clay mixed with ashes of the deceased. The term also referred to an image whose inner recess was enshrined with ashes of the deceased (J. Huo 2002, pp. 15–20). On the other hand, Wu Hung saw the manikin burial as a mixture of the Khitan burial custom of draining liquids such as blood from the corpse for mummification and the Daoist funerary custom of a “cypress figure” (Ch. bairen 柏人)—a figurine made of cypress wood to be buried inside a tomb as a stand-in for the deceased (Wu 2010, pp. 142–46). |

| 20 | The English translation is adopted with slight modifications from (Shen 2005, p. 106). The phrase reading “transcend the substance of the returning hun soul” (ji ji hun gui zhi zhi 冀濟魂歸之質) is, according to Zhang Fan, rooted in the traditional Chinese belief in the immortality of the soul that had been formed since the Qin and Han periods. Zhang also noted that inscriptions or objects bearing a similar phrase are difficult to find in Khitan tombs. See (F. Zhang 2005, p. 72). |

| 21 | T 967, 19: 351b9–18. See also (S. Yi 2018, p. 294). |

| 22 | A close parallel may be found in a stone coffin excavated from the Liao tomb, located in Xishangtai 西上臺, Mengkexiang 孟克鄕, Shuangtaqu 雙塔區, Chaoyang City, Liaoning Province. See (Han 2000, pp. 53–59). |

| 23 | The sutra seems to have been transmitted from Tang to Silla soon after its translation into Chinese in 704. On the one hand, the sutra contains six kinds of dhāraṇīs and instructions on how to put them into practice. Stone pagodas of the Unified Silla period have yielded examples of the sutra or its dhāraṇīs. Representative examples include: (1) the relic deposit from the stone pagoda at the site of Hwangboksa 皇福寺 in Kyŏngju 慶州 (built in 692 and repaired in 706); (2) the relic deposit from the west stone pagoda of Pulguksa 佛國寺 in Kyŏngju (built in 742 and repaired in the 11th century); (3) the relic deposit from the stone pagoda at Nawŏn-ri 羅原里, Kyŏngju (early 8th century); and (4) handwritten inscriptions of dhāraṇīs on paper yielded from the five-story west stone pagoda at Hwaŏmsa 華嚴寺 in Kurye 求禮 (9th century). On the other hand, the sutra also directs its practitioners to enshrine miniature pagodas in sets of 77 or 99 inside a larger, monumental pagoda. Examples include: (1) the relic deposit from the east three-story pagoda at Sŏdong-ri 西洞理, Ponghwa 奉化; (2) the relic deposit reportedly found in the three-story west pagoda of Kŭmdang’am 金堂巖, Tonghwasa 桐華寺 in Taegu 大邱; (3) the relic deposit from the Kilsang Pagoda 吉祥塔 of Haeinsa 海印寺, Hapch’ŏn 陜川 (dated 895); and (4) the relic deposit from the three-story stone pagoda at the former site of Sŏllimwŏn 禪林院, Yangyang 襄陽. For more on these cases and their historical implications, see (H. Kim 1975, pp. 15–18; Kim 2000; Chu 2004, pp. 164–96; 2011, pp. 264–93). |

| 24 | T 1024, 19: 718a25–27; 718b25–29. |

| 25 | Notable examples bearing an inscription of the verse include: (1) two silver strips from the wooden pagoda site at the former site of Hwangnyongsa 皇龍寺, Kyŏngju (ca. 872); (2) a gilt-bronze case from the stone pagoda at the former site of Powŏnsa 普願寺, Sŏsan 瑞山 (9th or 10th century); and (3) bricks with images of pagodas excavated at the former site of Sŏkchangsa 錫杖寺, Kyŏngju. A manuscript of the Cundī Dhāraṇī was found among the relic deposit of the west stone pagoda that originally stood at the former site of Karangsa 葛項寺 in present-day Kimch’ŏn 金泉 but was relocated to the National Museum of Korea in Seoul (dated 758). For more on the Korean reception of the verse and surviving examples, see (Kang 2014; Kim 2010). |

| 26 | The following discussion is indebted to (Na 2008, pp. 245–65). |

| 27 | Koryŏsa, fascicle 2, sega 2, the nineteenth year of King Kwangjong; Koryŏsa, fascicle 93, yŏlchŏn 6 Ch’oe Sŭngno. |

| 28 | For more on Zangchuan, see (Teiser 1994, pp. 69–71). |

| 29 | See Koryŏsa fascicle 127, yŏlchŏn 40, Kim Ch’iyang. It is worth noting that paintings of the ten kings occupy a large proportion of the Buddhist paintings produced in present-day Ningbo 寧波 during the Song and Yuan dynasties. These examples are mostly sets of ten hanging scrolls—each of which features one king. |

| 30 | See Koryŏsa, fascicle 11, sega 11, the ninth lunar month of the seventh year of King Sukchong; Koryŏsa, fascicle 11, sega 11, the seventh year of King Sukchong. |

| 31 | See Koryŏsa, fascicle 16, sega 16, the twenty-fourth year of King Injong. This record further indicates that Siwangsa in Kaegyŏng was active at least until the twelfth century. |

| 32 | A notable example is found in the Tomb of Chŏng Pyŏn 丁㭓, designated as Tomb No. 5 among those scattered on Mount Sŏkkap 石甲山 at Pyŏnggŏ-dong 平居洞 in Chinju 晋州. Facing south, the tomb consists of a circular earthen mound and rectangular stone structure. Three seed syllables in Siddhaṃ are carved at the center of the stone structure’s south side. Both sides of every corner of the stone structure bear a circle in which a seed syllable is engraved in Siddhaṃ symbolizing each of the Four Guardian Kings. The east wall of the tomb bears an inscription reading “Buried Taesang Chŏng Pyŏn on the tenth day of the twelfth lunar month of the chŏnghae year” (丁亥十二月十日大相丁㭓 葬), whereas the west wall bears an inscription reading “Began here in the eighth month and completed on the fifteenth day of the twelfth lunar month of the following year” (翊年八月始茲十二月十五日造成). Taken together, the chŏnghae year seems to correspond to 1107. The archaeologist Kim Wŏnyong, who first investigated the tomb, identified the three seed syllables on the south side as follows: the upper one stands for Amitabhā Buddha, the lower left one for Vairocana Buddha, and the lower right one for Śākyamuni Buddha (W. Kim 1964, p. 10). A new reading that identified the lower left one as the seed syllable of Mahāsthāmaprāpta Bodhisattva and the lower right one as that of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva has been forwarded in recent years (Yokota and Miki 2008, pp. 79–86; Ŏm 2016b, pp. 157–59). |

| 33 | The provenance and current whereabouts of this set remain unknown. The set is known from black-and-white photographs published in vol. 9, entitled “Craftworks Discovered inside Tombs of the Koryŏ Period,” of the Chōsen koseki zufu 朝鮮古蹟圖譜. It was the art historian Kim Pomin 김보민 who surmised that this dhāraṇī was originally encased in a round silver container on the same page of the publication. See (P. Kim 2018, pp. 33–34, 51–60). |

| 34 | Some fragments of the skull, mandible, and cervical vertebrae were reported to have been found inside the inner coffin, but the rest were decomposed leaving only partial traces (Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso 2016, p. 78). |

| 35 | Based on his interpretation of the Mantra of the Six-syllable King of Great Clarities, which might mean “May the jewel in the lotus purify and save [us],” the art historian Yi Yongjin 이용진 suggested that the mantra might have been inlaid on the P’yoch’ungsa incense burner “to achieve the aspiration to purify and save the world by means of burning incense”. He further suggested that the four letters on the body were a combination of the letters deemed most significant. See (Y. Yi 2011, pp. 14–18). |

| 36 | Earlier studies discussed a temple bell of 1157 (Chŏngp’ung 正豊 2) as the oldest instance of the Mantra of the Six-syllable King of Great Clarities and Mantra for Shattering Hell being inscribed together. The twelve letters, each of which appears in a circle on the upper part of the bell body, were considered to be double representations of the Mantra of the Six-syllable King of Great Clarities, whereas seven letters set in circles in the lower part of the body were identified as the Mantra for Shattering Hell. See (Hwang 1961, pp. 59–61; Chŏng 1961, pp. 175–76). In contrast, the art historian Chŏng Munsŏk 정문석 noted the difficulty of identifying this inscription due to the unclear shape of the Siddhaṃ letters (Chŏng 2011, p. 87n6). I also agree with Chŏng’s opinion. |

| 37 | T 1050, 20: 48c5–7. |

| 38 | T 1050, 20: 59c13–14. |

| 39 | T 1050, 20: 60a2–3. |

| 40 | Apart from these two incantations, others were also practiced by the Chinese and Korean Buddhists thanks to their presumed efficacy of shattering hell. For more on this, see (Hŏ 2016, pp. 151–52). |

| 41 | Manual on the Yoga Collection for Feeding the Searing Mouths (Ch. Yuqie jiyao yankou shishi yi 瑜伽集要焰口施食儀), whose Chinese translation is attributed to Amoghavajra, mentions another text called Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Lamp of Knowledge Which Destroys the Avīci Hell (Ch. Po api diyu zhiju tuoluoni jing 破阿毘地獄智炬陀羅尼經) as the source text of the mantra. See T 1320, 21: 476c. For more on the scriptural bases of the Mantra of the Lamp of Knowledge, see (M. Zhang 2013, pp. 106–7). |

| 42 | See X 1232, 63: 164a23–b7. For more on this, see also (Wang 2011, pp. 247–72). |

| 43 | T 1955, 46: 1005a27–b2. |

| 44 | T 1955, 46: 1005b5–6. |

| 45 | T 1955, 46: 1005b6–7. |

| 46 | T 1318, 21: 470b11–12; T 1320, 21: 476c11–19. |

| 47 | The modern scholar Heo Ilbeom (Hŏ Ilbŏm) mentioned two notable exceptions that are inscribed with the Mantra of the Lamp of Knowledge: the bell of Yujŏmsa 楡岾寺 (dated 1729) and a fragment of brick discovered at Mount Tongdaebong 東大峰山 in Andong 安東. See (Hŏ 2016, p. 152). |

| 48 | For more on the preface of this edition, see (Suyŏn Kim 2016a, 2016b). The bibliographic details of the known editions are discussed in (Nam 2017). |

| 49 | While translating Korean version of this article into English, I came across the art historian Son Hŭijin’s recent study that sheds new light on Koryŏ’s reception of the Mantra of the Lamp of Knowledge. She pointed out that the Mantra of the Lamp of Knowledge was published in the Collection of Sanskrit Dhāraṇīs and featured in a type of printed maṇḍalas from the thirteenth century. These printed maṇḍalas were originally part of the consecratory deposit (pokchang 腹藏) of Koryŏ Buddhist statues. See (Son 2021, pp. 35–38, 43–44). As Son rightly pointed out, the Koryŏ Buddhists made use of the two types of the mantras. However, I would like to emphasize that the Mantra of the Lamp of Knowledge rarely appears on Koryŏ Buddhist musical instruments on which the Collected Essentials on Attaining Buddhahood instructs to inscribe it. Such a shift may point to a different, perhaps native understanding of the mantra in Koryŏ. |

| 50 | X 961, 57: 119b17–c12, 119c13–21. |

| 51 | X 1497, 74: 807a12–17. |

| 52 | X 1136, 60: 800c4. |

| 53 | X 1499, 74: 1050a9. |

| 54 | Another possibility to entertain is the role of Jin, which succeeded much of Liao Buddhism. |

References

Primary Sources

Bukong juansuo Piluzhenafo da guanding guang zhenyan 不空羂索毘盧遮那佛大灌頂光眞言, T 19, no. 1002.Chŏng Inji 鄭麟趾 (1396–1478), ed. 1451. Koryŏsa 高麗史. Koryŏ sidae DB, compiled by Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe. Kwach’ŏn: Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe. Available online: http://db.history.go.kr/KOREA/item/level.do?itemId=kr&types=r (accessed on 17 October 2022).Dasheng zhangyuan baowang jing 大乘莊嚴寶王經, T 20, no. 1050.Fajie shengfan shuilu da zhai falun baochan 法界聖凡水陸大齋法輪寶懺, X 74, no. 1499.Fajie shengfan shuilu shenghui xiu zhai yigui 法界聖凡水陸勝會修齋儀軌, X 74, no. 1497.Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jing 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經, T 19, no. 967.Jinglü jiexiang busa guiyi 經律戒相布薩軌儀, X 60, no. 1136Shishi tonglan 施食通覽, X 57, no. 961.Wugou jingguang da tuoluoni jing 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經, T 10, no. 1024.Xianmi yuantong chengfo xin yaoji 顯密圓通成佛心要集, T 46, no. 1955.Yuqie jiyao qiu Anan tuoluoni yankou guiyi jing 瑜伽集要救阿難陀羅尼焰口軌儀經, T 21, no. 1318.Yuqie jiyao yankou shishi yi 瑜伽集要焰口施食儀, T 21, no. 1320.Zhijie chanshi zixing lu 智覺禪師自行錄, X 63, no. 1232.Secondary Sources

- “Aohanqi”. 1999. Aohanqi Lamagou Liao dai bihua mu (敖汉旗喇嘛沟辽代壁画墓). Neimenggu weunwu kaogu (內蒙古文物考古) 1: 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’a, Sunch’ŏl (Cha Soon Chul 차순철). 2008. T’ongil Silla sidae ŭi hwajang kwa Pulgyo waŭi sangho kwallyŏnsŏng e taehan koch’al: Chosa wa chot’ap sinang kwaŭi kwallyŏnsŏng ŭl chungsim ŭro (통일신라시대의 화장과 불교와의 상호관련성에 대한 고찰: 조사[造寺]·조탑[造塔] 신앙과의 관련성을 중심으로). Munhwajae (文化財) 41: 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏnggak (Junggak 正覺). 2002. Pulgyo cherye ŭi ŭimi wa haengbŏp: Si agwi hoe rŭl chungsim ŭro (불교 祭禮의 의미와 행법: 施餓鬼會를 중심으로). Han’guk Pulgyohak (韓國佛敎學) 31: 305–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏng, Munsŏk (Jung Moon-seok 정문석). 2011. Chosŏn sidae pŏmjong ŭl t’onghae pon pŏmja (조선시대 梵鐘을 통해 본 梵字). Yŏksa minsok’ak (역사민속학) 36: 83–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏng, Sŏngjun (Cheong Seong-joon 정성준). 2012. Yo Song sidae Chungguk milgyo ŭi Chunje chinŏn suyong yŏn’gu: Hyŏnmil sŏngbul wŏnt’ong sim yojip ŭl chungsim ŭro (요송시대 중국 밀교의 준제진언 수용 연구: 『현밀성불원통심요집』을 중심으로). Han’guk Sŏnhak (한국선학) 32: 219–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chŏng, Yŏngho (Chung Young-ho 정영호). 1961. Chŏngp’ung i nyŏnmyŏng sojong (正豊二年銘小鐘). Kogo misul (考古美術) 16: 175–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chōsen sōtokufu (朝鮮總督府), ed. 1919. Chōsen kinseki sōran (朝鮮金石總覽). Vol. 1. Keijō: Chōsen sōtokufu. [Google Scholar]

- Chōsen sōtokufu (朝鮮總督府), ed. 1929. Chōsen koseki zufu (朝鮮古蹟圖譜). Vol. 9. Keijō: Chōsen sōtokufu. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Kyŏngmi (Joo Kyeongmi 주경미). 2004. Han’guk pulsari changŏm e issŏsŏ Mugu chŏnggwang tae tarani kyŏng ŭi ŭiŭi (韓國佛舍利莊嚴에 있어서 『無垢淨光大陁羅尼經』의 意義). Pulgyo misulsahak (불교미술사학) 2: 164–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Kyŏngmi (Joo Kyeongmi 주경미). 2011. 8–11 segi Tongasia t’ap nae tarani pongan ŭi pyŏnch’ŏn (8~11세기 동아시아 탑내 다라니 봉안의 변천). Misusa wa sigak munhwa (미술사와 시각문화) 10: 264–93. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, Paul. 2014. The Body Incantatory: Spells and the Ritual Imagination in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Datong shi wenwu chenlieguan (大同市文物陳列館). 1963. Shanxi Datong Wohuwan si zuo Liao dai bihua mu (山西大同臥虎灣四座遼代壁畵墓). Kaogu (考古) 8: 432–36. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Yongqian (馮永謙). 1960. Liaoning sheng Jianping, Xinmin de san zuo Liao mu (遼寧省建平, 新民的三座遼墓). Kaogu (考古) 2: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Guoxiang (韓國祥). 2000. Chaoyang Xishangtai Liao mu (朝陽西上台遼墓). Wenwu (文物) 7: 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hebei sheng wenwu yanjiusuo (河北省文物硏究所), ed. 2001. Xuanhua Liao mu: 1975–1993 nian kaogu fajue baogao (宣化遼墓─1975–1993年考古發掘報告). 2 vols. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hŏ, Hŭngsik (허흥식). 1984. Koryŏ ŭi Yang T’aekch’un myoji (高麗의 梁宅椿 墓誌). Munhwajae (文化財) 17: 143–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hŏ, Hŭngsik (허흥식). 2008. Koryŏ e namgin Hyuhyuam ŭi pulbit (고려에 남긴 휴휴암의 불빛). Seoul: Ch’angbi. [Google Scholar]

- Hŏ, Ilbŏm (Heo Ilbum 허일범). 2016. Han’guk ŭi Yukcha chinŏn kwa P’a chiok chinŏn (한국의 육자진언과 파지옥진언). In Sunch’ang Ullim-ri Nongso kobun (淳昌 雲林里 農所古墳). Naju: Kungnip Naju munhwajae y’ŏn’guso, pp. 141–53. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Jiena (霍杰娜). 2002. Liao mu zhong suojian Fojiao yinsu (遼墓中所見佛敎因素). Wenwu shijie (文物世界) 3: 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Wei (霍巍). 2011. Tang Song muzang chutu tuoluoni jing zhou ji qi minjian xinyang (唐宋墓葬出土陀罗尼经咒及其民间信仰). Kaogu (考古) 5: 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Suyŏng (황수영). 1961. Koryŏ pŏmjong ŭi sillye (ki sam) (高麗梵鐘의 新例[其三]). Kogo misul (考古美術) 6: 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Hŭijŏng (Kang Heejung 강희정). 2014. Powŏnsa chi och’ŭng sŏkt’ap sariham ŭi yŏn’gi pŏpsong kwa haesang silkŭ rodŭ (보원사지 오층석탑 사리함의 연기법송[緣起法頌]과 해상실크로드). Misulsa wa sigak munhwa (미술사와 시각문화) 13: 38–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chihyŏn (Kim Jihyun 김지현). 2010. Kyŏngju Sŏkchangsa chi chŏnbul yŏn’gu (慶州 錫杖寺址 塼佛 硏究). Misulsahak yŏn’gu (美術史學硏究) 266: 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Chŏnghŭi (Kim Junghee 김정희). 1996. Chosŏn sidae Chijang siwang to yŏn’gu (조선시대 지장시왕도 연구). Seoul: Ilchisa. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hŭigyŏng (金禧庚). 1975. Han’guk Mugujŏng sot’ap ko (韓國無垢淨小塔考). Kogo misul (考古美術) 127: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Musaeng (김무생). 1986. Yukcha chinŏn sinang ŭi sajŏk chŏn’gae wa kŭ t’ŭkchil (六字眞言 信仰의 史的 展開와 그 特質). In Han’guk milgyo sasang (韓國密敎思想). Seoul: Tongguk taehakkyo Pulgyo munhwa yŏn’guwŏn, pp. 551–608. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Pomin (Kim Bomin 김보민). 2018. Koryŏ sidae Sugu tarani yŏn’gu: Pulbokchang mit punmyo ch’ult’op’um ŭl chungsim ŭro (고려시대 隨求陀羅尼 연구: 불복장 및 분묘 출토품을 중심으로). Master’s thesis, Myongji University, Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sŏngsu (金聖洙). 2000. Mugu chŏnggwang tae tarani kyŏng ŭi yŏn’gu (無垢淨光大陁羅尼經의 硏究). Ch’ŏngju: Ch’ŏngju koinswae pangmulgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Suyŏn (Kim Soo-youn 김수연). 2016a. Koryŏ sidae kanhaeng Pŏmsŏ ch’ongji chip ŭl t’onghaebon Koryŏ milgyo ŭi t’ŭkching (고려시대 간행 梵書摠持集을 통해본 고려 밀교의 특징). Han’guk chungsesa yŏn’gu (한국중세사연구) 41: 201–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Suyŏn (Kim Soo-youn 김수연). 2016b. Min Yŏnggyu pon Pŏmsŏ ch’ongji chip ŭi kujo wa t’ŭkching (민영규본 『범서총지집[梵書摠持集]』의 구조와 특징). Han’guk sasang sahak (韓國思想史學) 54: 145–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Wŏnyong (金元龍). 1964. Chinju P’yŏnggŏ-dong kinyŏn Koryŏ kobun’gun (晋州平居洞 紀年高麗古墳郡). Misul charyo (美術資料) 9: 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yongsŏn (金龍善), ed. 1993. Koryŏ myojimyŏng chipsŏng (高麗墓誌銘集成). Ch’unch’ŏn: Hallim taehakkyo Asia munhwa yŏn’guso. [Google Scholar]

- Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan (National Museum of Korea국립중앙박물관). 2006. Tasi ponŭn yŏksa p’yŏnji, Koryŏ myojimyŏng (다시 보는 역사 편지, 高麗墓誌銘). Seoul: Kungnip chungang pangmulgwan. [Google Scholar]

- Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso (국립나주문화재연구소), ed. 2014. Sunch’ang Ullim-ri Nongso kobun (淳昌 雲林里 農所古墳). Naju: Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso. [Google Scholar]

- Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso (국립나주문화재연구소), ed. 2016. Sunch’ang Ullim-ri Nongso kobun (淳昌 雲林里 農所古墳). Naju: Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Liying. 2014. Dhāraṇī Pillars in China: Functions and Symbols. In China and Beyond in the Mediaeval Period: Cultural Crossing and Inter-Regional Connections. Edited by Dorothy C. Wong and Gustav Heldt. New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 351–85. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Ling (李翎). 2008. Da suiqiu tuoluoni zhou jing de liuxing yu tuxiang (大隨求陀羅尼呪經的流行與圖像). Pumen xuebao (普門學報) 45: 127–67. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qingquan (李清泉). 2008. Xuanhua Liao mu: Muzang yishu yu Liao dai shehui (宣化辽墓: 墓葬艺术与辽代社会). Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Haiwen (劉海文), ed. 2008. Xunahua Xiabali II qu Liao dai bihua mu kaogu fajue baogao (宣化下八里II區遼代壁畵墓考古發掘報告). Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen (劉淑芬). 1996. Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jing he Tang dai Zunsheng jingchuang de jianli: Jingchuang yanjiu zhi yi (《佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經》和唐代尊勝經幢的建立─經幢硏究之一). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan (中央硏究院歷史語言硏究所集刊) 67: 145–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen (劉淑芬). 1997. Jingchuang de xingzhi, xingzhi he laiyuan: Jingchuang yanjiu zhi er (經幢的形制ㆍ性質和來源─經幢硏究之二). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan (中央硏究院歷史語言硏究所集刊) 68: 643–786. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen (劉淑芬). 2003. Muchuang: Jingchuang yanjiu zhi san (墓幢—經幢硏究之三). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan (中央硏究院歷史語言硏究所集刊) 74: 673–763. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen (劉淑芬). 2008. Miezui yu duwang (滅罪與度亡). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Zengxiang (陸增祥), ed. 1925. Baqiongshi jinshi buzheng 八瓊室金石補正. 130 vols. Wuxing: Liu shi Xigulou, Available online: https://repository.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/en/item/cuhk-2798404#page/2/mode/2up (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Ma, Shichang (馬世長). 2004. Da suiqiu tuoluoni manchaluo tuxiang de chubu kaocha (大隨求陀羅尼曼茶羅圖像的初步考察). Tang yanjiu (唐硏究) 10: 527–79. [Google Scholar]

- Na, Hŭira (Na Hee La 나희라). 2008. T’ongil Silla wa Na mal Yŏ ch’o ki chiok kwannyŏm ŭi chŏn’gae (통일신라와 나말려초기 지옥관념의 전개). Han’guk munhwa (한국문화) 43: 245–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Kwŏnhŭi (Nam Kwon-Hee 南權熙). 2017. Koryŏ sidae kanhaeng ŭi sujinbon soja ch’ongji chinŏn chip yŏn’gu (고려시대 간행의 수진본 小字 총지진언집 연구). Sŏjihak yŏn’gu (서지학연구) 72: 323–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ŏm, Ki-p’yo (Eom Gi-pyo 엄기표). 2016a. Han’guk pŏmja chinŏnmyŏng tonggyŏng ŭi t’ŭkching kwa ŭiŭi (韓國 梵字 眞言銘 銅鏡의 特徵과 意義). Yŏksa munhwa yŏn’gu (역사문화연구) 58: 35–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ŏm, Ki-p’yo (Eom Gi-pyo 엄기표). 2016b. Kobun ch’ult’o pŏmja chinŏn tarani ŭi hyŏnhwang kwa ŭiŭi (고분 출토 범자 진언 다라니의 현황과 의의). In Sunch’ang Ullim-ri Nongso Kobun (淳昌 雲林里 農所古墳). Naju: Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso, pp. 154–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, Chinkyŏng (Park Jinkying 박진경). 2017. Chunje suhaeng ŭigwe wa ŭisikku ro chejaktoen tonggyŏng (准提修行儀軌와 儀式具로 제작된 銅鏡). Pulgyo misul sahak (불교미술사학) 24: 147–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Hsueh-man. 2005. Body Matters: Manikin Burials in the Liao Tombs of Xuanhua, Hebei Province. Artibus Asiae 65: 99–141. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Hŭijin (Son Heejin 손희진). 2021. Koryŏ sidae pulbokchang paryŏp samsipch’il chon mandara yŏn’gu (고려시대 불복장 팔엽삼십칠존만다라[八葉三十七尊曼陀羅] 연구. Master’s thesis, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen F. 1994. The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, Patrick R. 2007. A Buddhist Rite of Exorcism. In Religions of Korea in Practice. Edited by Robert Buswell Jr. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 112–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Tsui-ling (王翠玲). 2011. Yongming Yanshou de xiuxing xilun: Yi youguan zhaomu er ke de tuoluoni weizhu (永明延壽的修行析論: 以有關朝暮二課的陀羅尼為主). Zhongzheng daxue Zhongwen xueshu niankan (中正大學中文學術年刊) 2: 247–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2010. The Art of the Yellow Springs. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Nan (向南), ed. 1995. Liao dai shikewen pian (遼代石刻文編). Shijiazhuang: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sŭnghye (Lee Seunghye 이승혜). 2018. Chungguk myojang tarani ŭi sigak munhwa: Tang kwa Yo ŭi sarye rŭl chungsim ŭro (중국 墓葬 陀羅尼의 시각문화: 唐과 遼의 사례를 중심으로). Pulgyohak yŏn’gu (佛敎學硏究) 58: 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Yongjin (이용진). 2011. Koryŏ sidae ch’ŏngdong ŭnipsa hyangwan ŭi pŏmja haesŏk (고려시대 靑銅銀入絲香垸의 梵字 해석). Yŏksa minsok’ak (역사민속학) 36: 7–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chigwan (李智冠), trans. 1994. Kyogam yŏkchu yŏktae kosŭng pimun (校勘譯註 歷代高僧碑文). Vol. 1 of Koryŏ. Seoul: Kasan mungo. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chiyŏng (이지영), Hyewŏn Yi (이혜원), and Sora Kim (김소라). 2016. Nongso kobun ŭi t’ŭkching kwa sŏnggyŏk (농소고분의 특징과 성격). In Sunch’ang Ullim-ri Nongso kobun (淳昌 雲林里 農所古墳). Naju: Kungnip Naju munhwajae yŏn’guso, pp. 128–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Hyeyŏn (Lee Hye Youn 이혜연). 2017. Sunch’ang Ullim-ri Nongso kobun ch’ult’o mokkwan ch’il punsŏk ŭl t’onghan chejak pangbŏp yŏn’gu (순창 운림리 농소고분 출토 목관 칠 분석을 통한 제작방법 연구). Pojon’gwahak’oeji (보존과학회지) 33: 355–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, Akira (横田明), and Haruko Miki (三木治子). 2008. Bonji no kizamareta “Kōrai” funbo: Keishōnandō Shinshū “Hirai hora kofungun” no saikentō (梵字の刻まれた「高麗」墳墓-慶尚南道晋州「平居洞古墳群」の再検討-). Ōsaka bunkazai kenkyū (大阪文化財研究) 33: 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Fan (張帆). 2005. Shitan Xuanhua Liao mu zhong suojian de zhenrong ouxiang (試談宣化遼墓中所見的眞容偶像). Zhongguo lishi wenwu (中國歷史文物) 1: 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Mingwu (張明悟). 2013. Liao Jin jingchuang yanjiu (遼金經幢硏究). Beijing: Zhongguo kexue jishu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S. The Dhāraṇī Coffin from the Nongso Tomb and the Cult of Shattering Hell during the Koryŏ Dynasty. Religions 2023, 14, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010121

Lee S. The Dhāraṇī Coffin from the Nongso Tomb and the Cult of Shattering Hell during the Koryŏ Dynasty. Religions. 2023; 14(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seunghye. 2023. "The Dhāraṇī Coffin from the Nongso Tomb and the Cult of Shattering Hell during the Koryŏ Dynasty" Religions 14, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010121

APA StyleLee, S. (2023). The Dhāraṇī Coffin from the Nongso Tomb and the Cult of Shattering Hell during the Koryŏ Dynasty. Religions, 14(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010121