Abstract

The Five Great Mantras (Odae chinŏn) is one of the most widely circulated collections of Buddhist dhāraṇīs in premodern Korea, having been published or existing in several variant editions during the Chosŏn period (1392–1910). The title refers to the following dhāraṇīs: (1) “The Forty-Two Mantras of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara,” (2) Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī, (3) Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī, (4) Buddhoṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī, and (5) Uṣṇīṣavijaya-dhāraṇī. Another spell, “The Basic Dhāraṇī of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara,” was also added, so there are a total of six dhāraṇīs contained in the book. Although most scholarship has hitherto understood the Five Great Mantras to date from the late fifteenth century, when editions with transcriptions of the dhāraṇīs in the Korean script appeared in trilingual format along with Siddhaṃ and Sinitic transliterations, due to the patronage of Queen Insu (1437–1508) and the linguistic ability of the monk Hakcho (fl. 1464–1520), some evidence has come to light suggesting that the Five Great Mantras was initially published as early as the mid-fourteenth century in the late Koryŏ period (918–1392). This essay provides a detailed analysis of the components that appear in the Five Great Mantras by analyzing six variant editions of the text dating from the Chosŏn period, including Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance (Yŏnghŏm yakch’o) in Sinitic and Korean vernacular translation. The Five Great Mantras demonstrates the significance of non-canonical materials in the Korean Buddhist tradition and suggests a fruitful avenue for study of similar woodblock prints and manuscripts in the Sinitic Buddhist tradition.

1. Introduction

The Five Great Mantras (Odae chinŏn 五大眞言) is the general or genre name for a popular and much published one-volume collection of Buddhist dhāraṇīs and mantras that circulated widely in premodern Korea from the middle to late Koryŏ 高麗 period (918–1392) through the Chosŏn 朝鮮 period (1392–1910). However, because scholars have identified numerous similar editions printed from woodblocks that include varying materials and have different titles written on the covers, it might be more correct to describe this material phenomenon as “a body of printed material known collectively as the Five Great Mantras.” The term “five great” in the title refers to the following dhāraṇīs, which are commonly referred to in contemporary Korean Buddhist literature as: (1) The Forty-Two Mantras of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Sasibi su chinŏn 四十二首眞言), (2) Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī [The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases] (Sinmyo changgu taedarani 神妙章句大陀羅尼), (3) Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī (Sugu chŭktŭk tarani 隨求即得陀羅尼), (4) Buddhoṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī (Taebulchŏng tarani 大佛頂陀羅尼), and (5) Uṣṇīṣavijaya-dhāraṇī (Pulchŏng chonsŭng tarani 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼). However, because another spell, “The Basic Dhāraṇī of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara” (Kwanjajae posal kŭnbon tarani觀自在菩薩根本陀羅尼) was also added, there are, in fact, a total of six dhāraṇīs contained in some editions published during the Chosŏn period. Some editions of the Five Great Mantras also include a section called Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance (Yŏnghŏm yakch’o 靈驗略抄), which may appear in either Sinitic and Korean vernacular translation (Yŏnghŏm yakch’o ŏnhae영험약초언해 [靈驗略抄諺解]).

In this paper, I first briefly contextualize the importance of dhāraṇīs and dhāraṇī collections in medieval Korea and the role of Queen Insu 仁粹 (1437–1508) and the monk Hakcho 學祖 (fl. 1464–1520) in making the Five Great Mantras more accessible to a wider audience. I then introduce six different woodblock editions of the Five Great Mantras, one held by the Kyujanggak Archives1 and five by the Dongguk University Central Library in Seoul, Korea. After briefly analyzing the contents of the different editions, I discuss important characteristics of the individual dhāraṇīs appearing in the collection and describe some insights and observations that may be derived from analyzing these curious and important materials. The most important of these include that these kinds of collections show an element of lived Buddhism, or Buddhism “on the ground” following the expression often used by Gregory Schopen, focused on non-canonical materials. Although the Five Great Mantras appears to be for everyday use by a lay Buddhist audience, unlike Japanese shidai 次第 ritual books, they are not “how to manuals” and there are limited to no extant instructions for use. In addition, Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Response functions less like an explanation of how to use the dhāraṇī collection than an endorsement of the benefits of utilizing these mantras and dhāraṇīs in a lay Buddhist’s life. This jibes with arguments advanced in my previous scholarship that questions classifying Buddhist spells universally or comprehensively as “esoteric” Buddhism, because of their practical nature and accessibility to lay Buddhists (McBride 2004, 2005, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2019a, 2019b, 2020a). In addition, this material questions scholarly focus or emphasis on texts contained in published Buddhist canons, such as the Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon (Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經), because the Five Great Mantras were published independently multiple times during the Chosŏn period and because the versions of the dhāraṇīs are decidedly non-canonical. This highlights the importance of variant texts and editions for understanding the actual practice of Buddhism in the East Asian or Sinitic context.

On the surface, and in particular because of the title, the Korean Five Great Mantras bears some resemblance to the illustrated manuscripts titled Pañcarakṣā (Five Great Mantras), known from the Buddhist traditions of Nepal, Tibet, and Mongolia (Lewis 2000; Aalto 1954; Mevissen 1989, 1992).2 However, unlike the Nepalese versions, which couch the spells in a narrative framework, most of the Korean woodblock prints strip the spells from their prose context and present the spells with a minimum of prefatory material. Prose explaining the uses and benefits of these dhāraṇīs is found in some editions and printings of the Five Great Mantras in sections titled Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance, which will be discussed in detail later in the paper. That the five or six dhāraṇīs lack prose context suggests their use in settings or situations when memory and oral communication predominated. In addition, compilations of Buddhist spells remaining from the Koryŏ period just present the dhāraṇīs and mantras themselves mostly without any explanatory material. For this reason, the absence of prose context may merely be an accepted convention.

Furthermore, unlike the case of China, where the Sinitic (Buddhist-Chinese) transliteration of the spell is typically viewed as being as powerful as a Siddhaṃ text, in Korea, as in Japan, the Tang 唐 monk Amoghavajra’s (Bukong 不空, pp. 705–74) versions of the spells seem to have gained ascendency primarily because they are linked to extant Siddhaṃ texts. In other words, if a Siddhaṃ text exists, Korean Buddhists have presumed that it was transmitted or produced by Amoghavajra. This is likely because Amoghavajra’s work primarily consists of ritual manuals and rearrangements, additions, and embellishments of chapters of existing Buddhist sūtras dealing with ritual knowledge. A large number of texts have been ascribed to Amoghavajra by the later Buddhist tradition and some works probably composed by his disciples were attributed to him to provide legitimacy (Strickmann 1996, pp. 80–81; Lehnert 2011, pp. 357–59).

Until recently, these mantra collections had not been utilized or analyzed by scholars of Korean religion; rather, they were almost exclusively studied by scholars of linguistics, calligraphy, and those interested in the development and evolution of the Korean vernacular script. (The script was originally called hunmin chŏngŭm 訓民正音 [correct sounds to instruct the people], but now commonly called han’gŭl in South Korea, although scholars tend to use the abbreviation chŏngŭm 正音 to differentiate it from the modern forms of the letters) (An 1987; Nam 1999; An 2003, 2004, 2005; Kim 2011). Scholars of religion and history had really only looked at these texts in a broad sense to discuss the printing and publication of Buddhist texts in the late Chosŏn period and the popularity of mantra collections (Sørensen 1991–1992; Nam 2000, 2004a, 2004b; Nam and Diederich 2012).

2. Early Editions of the Five Great Mantras, Queen Insu, and Hakcho

The most important piece of evidence attesting that the Five Great Mantras was originally published in the Koryŏ period is that a woodblock print of one page, which depicts five of the forty-two hand-mantras associated with Avalokiteśvara, was discovered as part of the material enshrined inside a gilt-bronze seated image of the Buddha Amitābha (kŭmdong Amit’abul pokchangmul 金銅阿彌陀佛服藏物) at Munsu Monastery 文殊寺 in Sŏsan 瑞山, South Ch’ungch’ŏng Province. The print has the Sinographs odae 五大 (five great) and the number o 五 (5) printed on the seventh line from the right edge of the print. Because other material enshrined in the image, most importantly the “Vow Text on the Creation of the Buddha Image” (pulsang chosŏng parwŏnmun 佛像造成發願文), is dated to “the sixth year of the Zhizheng reign period of the Great Yuan dynasty” (Tae-Wŏn Chijŏng yungnyŏn 大元至正六年), or 1346, we can be certain that the Five Great Mantras was printed prior to that date (Chisim kwimyŏngnye 2004, pp. 16, 27; Mun and Kim 2021, p. 199). What is significant about the arrangement of the five hand-mudrās is that, unlike later editions of the Five Great Mantras dating to the Chosŏn period, the short mantras are presented only bilingually in Siddhaṃ script and Sinographic transliteration.

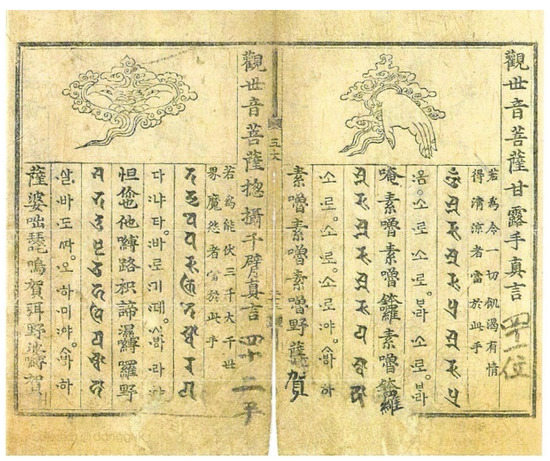

Before scholars recognized that pages from a Five Great Mantras edition from the Koryŏ period exist, many scholars, including myself, understood that the oldest extant edition was the Sangwŏnsa edition上院寺本 (also called the Wŏlchŏngsa edition 月精寺本) because it is preserved at Sangwŏn Monastery, a branch of Wŏlchŏng Monastery, on Mt. Odae 五臺山 (An 2003, 2004; Kim 2011). The most distinctive characteristic of this and later editions is that the dhāraṇīs are presented in a trilingual manner, with alternating lines of Siddhaṃ on the right, a vernacular transliteration in the Korean script to the left of the Siddhaṃ, and the Buddhist-Chinese transliteration (in Sinographs) to the left of the transliteration in Korean script (see Figure 1). In addition, this edition, and others related to it feature a colophon (palmun 跋文) dated to 1485. This date was previously held to be the earliest date for the publication of the Five Great Mantras as a complete set. This colophon links Queen Insu and the monk Hakcho to the publication of editions of the Five Great Mantras featuring the dhāraṇīs in trilingual format for the purpose of enabling the masses of common people to become familiar with, memorize, and recite these dhāraṇīs and mantras.

Figure 1.

Trilingual layout from “The Forty-two Hand-Mantras” section of Five Great Mantras. (Odae chinŏn n.d. A, p. 24).

Queen Insu, the more popular title of Queen Dowager Sohye昭惠王后 (née Han韓氏, 1437–1508), the mother of King Sŏngjong 成宗 (r. 1469–1494), was a staunch promoter and protector of Buddhism in the fifteenth century. On the one hand, she is remembered for her composition of Admonitions to Women (Naehun 內訓), published in 1475, which promoted Confucian principles and mores among women; on the other hand, she was one of the most important royal patrons of Buddhism during the Chosŏn period. In 1460, she was directly involved in work on the Vernacular Translation of the Śūraṃgama-sūtra (Nŭngŏm kyŏng ŏnhae 楞嚴經諺解), which was soon thereafter published in both woodblock and moveable metal type editions. Over the next decade, she was involved with the Director-in-chief of Sūtra-Publication (kan’gyŏng togam 刊經都監) in the printing of thirty-three Buddhist sūtras in Sinitic and nine vernacular translations of Buddhist scriptures, until the position was abolished in the twelfth lunar month of 1471. She became even more involved in sūtra-publication after that, bringing to pass the publication of twenty-nine Buddhist sūtras, including the Lotus Sūtra (Fahua jing 法華經), Śūraṃgama-sūtra (Lengyan jing 楞嚴經), and Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment (Yuanjue jing 圓覺經) in 1472. Kim Suon’s 金守溫 (1410–1481) colophon for the Chosŏn edition of the Comprehensive Record of the Buddhas and Patriarchs Over Successive Generations (Fozu lidai tongzai 佛祖歷代通載) cites the importance of the “four extensive vows” (sa hongwŏn 四弘願)3 to Queen Insu (Yi 2006; Kim 2016a, pp. 93–97). Before the publication of the Five Great Mantras in 1485, Queen Insu appears to have published individually some of the vernacular Korean translations of the dhāraṇīs contained in the Five Great Mantras. A case in point is the woodblock edition of the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī (viz. The Forty-Two Hand-Mantras), published in 1476, which is preserved in the Komazawa Library in Japan (Ha 2019).

The afore-mentioned colophon to the Five Great Mantras was composed by the monk Hakcho. Hakcho hailed from the Andong Kim clan 安東金氏. His pen names were Tŭnggok 燈谷 and the “Religious Man of Hwangak” 黃岳山人. His father was Kim Kyegwŏn 金係權 (1410–1458), a scholar-official during the reign of King Sejong 世宗 (1418–1450). He enjoyed the cordial trust of King Sejo 世祖 (r. 1455–1468) as a Sŏn 禪 monk, along with such monks as Sinmi 信眉 (1403–1480) and Hagyŏl 學悅 (d.u.). He translated many Buddhist scriptures into the Korean vernacular and publish them with several eminent monks of the time. He was a famous Buddhist monk of his time who possessed surpassing learning and virtue, and he was praised as a great author of profound and powerful writing.

Hakcho was held in high esteem by the royal family and, after the time of Sejo and through the age of Chungjong 中宗 (r. 1506–1544), he held many Buddhist services on their behalf. In 1464, he welcomed King Sejo at Pokch’ŏn Monastery 福泉寺 on Mt. Songni 俗離山 and held a great dharma assembly with Sinmi and Hagyŏl. In 1467, he renovated Yujŏm Monastery 楡岾寺 on Mt. Kŭmgang 金剛山 by royal order. In 1488, by order of Queen Insu, he restored Haein Monastery 海印寺 and renovated the hall protecting the woodblocks of the Koryŏ Buddhist Canon (Koryŏ taejanggyŏng 高麗大藏經). In 1500, by order of the queen, he published the three parts of the Buddhist canon at Haein Monastery and wrote a colophon. In 1520, he again published one section of the Buddhist canon at Haein Monastery by royal order.

Hakcho executed vernacular translations of several Buddhist canonical materials. It is inferred that his Vernacular Translation of the Kṣitigarbha-sūtra (Chijang kyŏng ŏnhae 地藏經諺解) was among the first. He completed a Vernacular Translation of the Commentaries of the Three Masters of the Diamond Sūtra (Kŭmgang kyŏng samgahae ŏnhae 金剛經三家解諺解)4 for Prince Suyang 首陽大君 (1445–1455), the future King Sejo, and it was corrected and published by order of Queen Chasŏng 慈聖大妃 (1418–1483), Sejo’s primary consort. In 1476, he executed a vernacular translation and revision of the Thousand Hands Sūtra (Ch’ŏnsu kyŏng 千手經). In 1482, he completed his Korean translation of Nanming’s Continued Verses on the “Song on Realizing the Way to Enlightenment” (Zhengdao ge Nanming jisong 證道歌南明繼頌), which he had started during the time of Sejong and then discontinued. Aside from that, although the dates are not completely clear, Hakcho most likely translated and published the Five Great Mantras, the Buddhoṣṇīṣa-hṛdaya-dhāraṇī (Pulchŏngsim tarani 佛頂心陀羅尼) and Encouraging Offerings with Mantras (Chinŏn kwŏn’gong 眞言勸供) in 1485 (Kim 2016a, pp. 95–96). Hakcho’s colophon is instructive because it not only highlights Queen Insu’s purposes in making the Five Great Mantras accessible to all Buddhists, both monastic and lay, but it also shows that both Queen Insu and Hakcho espoused the mainstream Mahāyāna Buddhist goal of encouraging all people to become bodhisattvas and engage in the work of saving living beings. The fact that numerous editions of the Five Great Mantras have been preserved in Korea, many of which reprint Hakch’o’s colophon, serves as evidence that Queen Insu and Hakcho successfully disseminated the dhāraṇī collection among the people.

Now, with respect to the opportunities in the realm, the myriad works are different and the prescriptions for good medicine are also different. Therefore, our Enlightened King [Buddha], following the whole dharma realm, continually produced approaches to dharma [numbering as] the dust and sands, and [living beings] are able to enter through each and every approach. Generally speaking, those who possess knowledge invariably follow opportunities and obtain benefits. Nevertheless, the entrance into these approaches may be slow or fast, and visualization practices (kwanhaeng 觀行) may be hard or easy. There is nothing that does not draw a person to expedient means (pangp’yŏn 方便), so what will wholesome artifices (sŏn’gyo 善巧) be like? Because we live in an age when we are met with the fortunes of the degenerate age, due to this if the roots of the people rely on dhyāna (sŏnna 禪那), they will be highly praised in the sphere of the sages (sŏnggyŏng 聖境). If they discuss medicine, they must submit to being designated inferior. For this cause, square-robed round-heads [monks] all become wayfarers in the mundane world (p’ungjin 風塵), and the white-robed [laypeople] and eminent persons forever become denizens of hell (narak 那落; Skt. naraka).

Our Great Queen Insu 仁粹大妃 [1437–1504], Her Majesty, pities the cold-heartedness of the way of the world and the urgency of the trends of the time. What is acutely [necessary] for this time and is a benefit to people is that there is nothing like the “five great mantras” (odae chinŏn 五大眞言). One does not have to be engrossed in Sŏn-meditation, and one does not have to investigate the principles of righteousness; and yet if one is caused to carry and chant [these dhāraṇīs], one will obtain blessings and all the methods for benefiting people in the degenerate age that are described in the sūtras. There is nothing higher than this.

However, because this sūtra is in strange and obscure [characters] in Sanskrit and Chinese, those who read it experience great difficulty. Thereupon, I sought for and obtained an annotated Tang edition, made a translation into the vernacular (ŏn 諺) and repeatedly published it and distributed it among the masses and make it easy for recitation and practice. Because there is no difference between [practitioners who are] sharp or dull, it is convenient to wear and protect. Because there is no difference between noble and abased, it is simple to receive and observe. If profound disposition [is possessed], all will balance individually and obtain a status that follows one’s inclinations. Each and every person falls short of the merit of the height of bodhi, and causing the four groups of living beings5 [to attain] seeing and hearing6 to ascend the virtue of the sphere of liberation.

In addition, life and death, hidden and manifest, return to the ordinary and become blissful. Last time, up to the deceased spirits of the royal ancestors, all were caused to be endowed with profound dispositions. Additionally, Her Majesty, the Queen, wisely rears her descendants for a long time, causes them to flourish like jade leaves (ogyŏp 玉葉), and when they chant [texts], all offer praises for her long life, and to the limit of carrying and reciting certainly say: “The efficacy of the exalted five great [mantras] and the circulation of bright and clear popular voice will amass from generation to generation.” Could Her Majesty be able to take care of this matter perfectly as this?

The colophon was respectfully written by the religious man (sanin 山人) and vassal (sin 臣) Hakcho 學祖, in the early summer of ŭlsa 乙巳, the twenty-first year of the Chenghua 成化 reign period [1485].(Odae chinŏn 1635, palmun 1a–2b; Kim 2010, pp. 168–69)

Hakcho’s colophon asserts that dhāraṇīs are “expedient means” and are the most functional means of Buddhist practice in the “degenerate age” in which he lived. In addition, he also stresses that because Queen Insu pitied the depraved state of humanity, she recognized the superior benefits of chanting the “five great mantras.” Hakcho affirms that although visualization practices and meditation are not accessible to everyone, “if one is caused to carry and chant [these dhāraṇīs], one will obtain blessings and all the methods for benefiting people in the degenerate age that are described in the sūtras.” In other words, carrying a dhāraṇī on one’s person in the manner of a talisman (pujŏk 符籍) or chanting the dhāraṇī will provide one with the necessary merit and knowledge to benefit living beings in the p resent age of the decline of the Buddhadharma.

Another curious statement that cannot be ignored is that Hakcho emphasizes that he sought for and acquired a “Tang edition” of the dhāraṇīs with annotations. Why did Hakcho search for Tang editions? Did Tang editions confer legitimacy? Did he consider them superior to the more edited and elegant collections of scriptures published by the Song (Kaibao Canon 開寶藏), Liao (Khitan Canon 契丹藏) and Koryŏ courts? Being a monk favored by the royal family and one familiar with Haein Monastery, which had housed the woodblocks of Koryŏ Buddhist Canon since 1398, why did he not want to use the versions of the spells available in that collection? The source texts used by Hakcho usually range from slightly different to quite different from the versions of the dhāraṇīs printed in the Koryŏ Buddhist Canon and, hence, in the Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon.

In this study, I have examined six versions of the body of material that scholars call the Five Great Mantras. Table 1 provides a summary of the contents of these versions that compares them to the other versions. Not for arbitrary reasons have I listed the 1635 edition first—as a complete edition of the Five Great Mantras. The primary reason is that it is the only edition of the Five Great Mantras that has been published in photolithographic form (Kim 2010, pp. 139–358 [from the back]). In addition, it represents a fully realized edition in literary Sinitic that has evolved from the early editions of 1485. Although none of the editions have all the same material, there is remarkable continuity between the various versions of the Five Great Mantras in that the trilingual transliterations of the dhāraṇīs and invocative petitions (kyech’ŏng 啓請; Skt. adhyeṣanā) are the same in all of the woodblock editions I examined.

Table 1.

Comparison of Odae chinŏn Manuscripts.

Now I will examine each of the six dhāraṇīs individually and the Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance. Before proceeding with this analysis, let me concisely describe the differences of these remaining five versions. The 1485A version contains five of the six dhāraṇīs, strongly supporting the supposition that the “Basic Dhāraṇī of the Thousand-Handed Thousand-Eyed Avalokiteśvara” was added as a sixth dhāraṇī to the Five Great Mantras during the early Chosŏn period. The 1485A version also includes a handwritten dhāraṇī-sūtra and a short sūtra both written in transliteration in the Korean script. These two texts are not found in other versions of the Five Great Mantras, although dhāraṇī-sūtras written in the Korean script are not uncommon from the late Chosŏn period. The 1485B version comprises the Buddhoṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī, Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī, and Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance, and also includes Hakcho’s colophon. The 1550 version comprises a Vernacular Translation of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance, written in the Korean script, with the postscript and Hakcho’s colophon. It also preserves the names of the donors who published this edition. The first undated print (n.d. A) has the first three dhāraṇīs matching the 1635 edition, but ends after the first page of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī. The second undated print (n.d. B) has the Forty-two Hand-mantras of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara and the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī, both without their invocative petitions, as well as the sections of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance corresponding to the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī and the Buddhoṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī.

3. The Forty-Two Hand-Mantras

The forty-two hand-mantras are closely related to the widespread worship of Avalokiteśvara and the importance of the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī in premodern Korea. Translations of the dhāraṇī-sūtra likely entered the Korean peninsula during the second half of the seventh century. The cult of this form of Avalokiteśvara flourished in premodern Korea just as it did in other parts of East Asia (Ok 2020). The Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī is better known in East Asia as the “Great Compassion Spell” (taebi chu, Ch. dabei zhou 大悲呪), which will be discussed in more detail in the next section. Simply stated, the forty-two hand-mantras are not mudrās, “seals,” or “hand-seals” (su 手, suin 手印, in 印) that aspirants make with their own hands while chanting the associated mantras so much as they depict objects held in the hands of images (statues and paintings) of the Thousand-armed Thousand-eyed Avalokiteśvara (Ch’ŏnsu Ch’ŏnan Kwanŭm 千手千眼觀音; Skt. Sanhasrabhuja Sahasranetra). In East Asian Buddhist art, the Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara is often combined with the Eleven-headed Avalokiteśvara (Sibimyŏn Kwanŭm 十一面觀音; Skt. Ekādaśamukha), and the “thousand-armed” part of the image depicts most, if not all, of these items. The forty-two hand-mantras of the Five Great Mantras influenced representations of Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara in paintings and statues throughout the Chosŏn period (Kim 2018).

As mentioned previously, the single sheet of a Five Great Mantras published in the Koryŏ period displays five of the forty-two hand-mantras found in more complete editions of the collection from the Chosŏn period. The origin of the forty-two hand-mantras found at the beginning of many editions of the Five Great Mantras has been a matter of considerable debate among scholars because the received canonical editions of the Nīlakaṇṭha only describe either forty or forty-one hand-mantras. The Indian monk Bhagavaddharma’s (Qiefandamo 伽梵達磨, fl. 650–661) translation of the Nīlakaṇṭha (Qian-shou qianyan Guanshiyin pusa guangda yuanman wuai dabeixin tuoluoni jing 千手千眼觀世音菩薩廣大圓滿無礙大悲心陀羅尼經, T 1060) describes forty mantras (chinŏn, Ch. zhenyan 眞言) (T 1060, 20.111a–b). A translation of the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī (Qianshou qianyan Guanshiyin pusa dabeixin tuoluoni 千手千眼觀世音菩薩大悲心陀羅尼, T 1064) attributed to Amoghavajra presents forty-one hand-mantras (sujinŏn, Ch. shouzhenyan 手眞言), images depicting them, and short mantras transliterated using Sinographs (T 1064, 20.115b–119b). The forty-two hand-mantras in the Five Great Mantras comprise a mixture of at least these two versions of the Nīlakaṇṭha, and perhaps combined with influences from other associated texts (see Figure 1).

As we shall also see in the section on the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī, the section on the forty-two hand-mantras of Avalokiteśvara shows something of a Korean proclivity to combine and arrange extant materials in creative ways. In this section, the first forty hand-mantras follow the order and almost always the descriptive sūtra language presented in Bhagavaddharma’s translation of the Nīlakaṇṭha, but the image depicting the seal or mudrā and the mantra follow the translation attributed to Amoghavajra (Kang 2013, pp. 268–75). In this, the Five Great Mantras follows the form of an edition of the Dhāraṇī Collection in Indic Script (Pŏmsŏ ch’ongji chip 梵書摠持集), a non-canonical work which was published in Koryŏ in 1218 (Kim 2016b, pp. 174–75). Often the Sinographs used to transliterate the emphatic words used to end the mantra (svāha, phaṭ, etc.) are given using different Sinographs than those in the received edition, based on the Koryŏ Buddhist Canon (viz., what is found in the Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon). From the standpoint of Amoghavajra’s translation, the hand-mantras are all mixed up, and the forty-first hand-mantra is the first one given in the Amoghavajra translation (T 1064, 20.117a10–15).

Kang Taehyŏn (Kang 2013, pp. 259, 275) has shown evidence that the forty-second hand-mantra, the “seal that comprehensively embraces the thousand arms” (ch’ongsŏp ch’ŏnbi in 摠攝千臂印), is based on Zhitong’s 智通 (fl. 627–649) translation of the Nīlakaṇṭha (Qianyan qianbi Guanshiyin pusa tuoluoni shenzhou jing 千眼千臂觀世音菩薩陀羅尼神呪經, T 1057) and/or, perhaps, Bodhiruci II’s (Putiliuzhi 菩提流支, d. 727) translation of the Nīlakaṇṭha (Qianyan qianbi Guanshiyin pusa lao tuoluoni shenzhou jing 千眼千臂觀世音菩薩姥陀羅尼身呪經, T 1058) because both translations describe “seals” with this name (T 1057, 20.85c16–21; T 1058, 20.99a4–9). Hwanggŭm Sun (Hwanggŭm 2016) suggested the possibility that illustrated manuscripts from Ming 明 China (1368–1644) had been transmitted to Korea to account for the forty-two hand-mantras and hand-seals. Ha Chŏngsu (Ha 2019) introduced a Korean vernacular text published in 1476 that contains the forty-two hand-seals.

By focusing on the Dhāraṇī Collection in Indic Script, which was published in the Koryŏ period, Ok Nayŏng (Ok 2020), on the other hand, argues that the forty hand-mantras were particularly recognized in Koryŏ’s Buddhist community and that the published editions of the forty-two hand-mantras published in the Chosŏn period are different from those made in the Ming period. Mun Sangnyŏn (Venerable Chŏnggak) and Kim Yŏnmi (Mun and Kim 2021) promote the idea that the Sūtra on the Esoteric Dharma of the Thousand-eyed Avalokiteśvara (Qianguangyan Guanzizai pusa mimifa jing 千光眼觀自在菩薩祕密法經, T 1065), which was translated by the otherwise unknown Indian monk Sanmeisufuluo 三昧蘇嚩羅, who was active in the Tang period, played a key role in the development of these hand-mantras, which then became widespread in thirteenth-century Koryŏ.

Despite varying scholarly opinions on the origin, the grouping of forty and, later, forty-two hand-mantras shows great continuity through the Chosŏn period and into the modern period. A modern Buddhist collection of dhāraṇīs and mantras created for mass consumption includes the forty-two hand-mantras in two formats: a revised transliteration in the Korean script that is closer to Sanskrit, as well as the received pronunciation that is the same as that found in the Five Great Mantras (Chŏng 2013, pp. 115–31). In addition, the forty-two hand-mantras have been repackaged for the South Korean audience of the twenty-first century interested in Sanskrit Buddhist spells, without the transliteration in Sinographs (Pak and Yi 2015, pp. 266–313; Pak 2018).

4. Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī, or The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases

The Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī is arguably the most popular Buddhist spell in Sinitic Buddhism. Used to invoke the sublime and mysterious power of one of the most commonly venerated versions of Avalokiteśvara, the Thousand-Armed Thousand-Eyed Avalokiteśvara, this dhāraṇī, widely known as the “Great Compassion Spell,” has been deployed extensively by the Buddhist faithful since its introduction to the Korean peninsula shortly after its translation into Buddhist Chinese in the mid-seventh century (McBride 2008, pp. 70–72, 81, 85, 119–20). Space does not permit a survey of the relevance of the Great Compassion Spell and the related Great Compassion Repentance Ritual in East Asia, particularly China (see Reis-Habito 1993, pp. 249–69; 1994; Yü 2001, pp. 263–91). Modern annotated translations of Bhagavaddharma’s version (T 1060) have been published in German, Japanese, and Korean (Reis-Habito 1993, pp. 160–244; Noguchi 1999, pp. 53–195; Chŏnggak 2011, pp. 400–63). The canonical versions of the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī or Great Compassion Spell are different from the version in the Five Great Mantras and other texts circulating in Korea. Takubo Shūyo classifies the canonical version of the dhāraṇīs associated with the Nīlakaṇṭha into four groups, as outlined in Table 2 (Takubo 1967, p. 119).

Table 2.

Canonical Versions of the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī.

The Korean version published in the Five Great Mantras, at 77 phrases (Odae chinŏn 1635, pp. 24a–29a; Kim 2010, pp. 233–34), represents a different transmission and more than likely specialized editing by the Korean Buddhist community. In the Korean context, this spell is more commonly known as “The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases” (Sinmyo changgu taedarani 神妙章句大陀羅尼). During the late Chosŏn period, “The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases” became the centerpiece and primary spell of a continually revised version of the Nīlakaṇṭha that reads like a ritual manual. Detailed ritual procedures appeared in numerous texts beginning in 1607, continued to evolve, and reached their “final” or current form in Received and Upheld by Practitioners (Haengja suji 行者受持), which was published by Haein Monastery in 1969 (Chŏnggak 2011, pp. 110–17). Scholars refer to this as the “current” (hyŏnhaeng 現行) Thousand Hands Sūtra (Ch’ŏnsu kyŏng 千手經). It is one of the most widely popular and utilized sūtras in contemporary Korean Buddhism, particularly in what are best described for an Anglophone audience as daily devotionals. “The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases,” by itself, currently plays a significant role in daily devotionals, sūtra-copying, and other dhāraṇī-practices in the contemporary Korean Buddhist tradition (McBride 2019b, pp. 365–70, 375, 379).

The Five Great Mantras prefaces “The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases” with a twelve-line series of invocations of individual bodhisattvas, with all bodhisattva-mahāsattvas being invoked in the final line.

| 觀世音菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Avalokiteśvara |

| 大勢至菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Mahāsthāmaprāpta |

| 千手菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Thousand-Armed [Avalokiteśvara] |

| 如意輪菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Cintāmaṇi-cakra [Avalokiteśvara]7 |

| 大輪菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Mahācakra8 |

| 觀自在菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Avalokiteśvara |

| 正趣菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Ananyagāmin9 |

| 滿月菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Full Moon |

| 水月菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Water Moon |

| 軍陁利菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Kuṇḍalī10 |

| 十一面菩薩摩訶薩 | The Bodhisattva-Mahāsattva Eleven-Faced [Avalokiteśvara] |

| 諸大菩薩摩訶薩 | All the great bodhisattva-mahāsattvas (Odae chinŏn 1635, 24a) |

Six of the eleven bodhisattva names refer to different incarnations or versions of Avalokiteśvara, if we accept that the Bodhisattva Water Moon refers to a version of Avalokiteśvara. As expected, this list of invocations is not common in canonical materials, but it does correspond well to the final portion of the pre-spell invocations found in the “Procedures for the Evening Recitation” (Sŏksong chŏlch’a 夕誦節次) found in two of the most important compendia of Korean Buddhist rituals published in the 1930s: Must Read Texts for Buddhists (Pulcha p’illam 佛子必覽), which was compiled and published in 1931 by Ch’oe Ch’wihŏ 崔就墟 (1865–d. after 1940) and An Sŏgyŏn 安錫淵 (also known as Chinho 震湖, 1880–1965) and An Chinho’s Buddhist Rituals (Sŏngmun ŭibŏm 釋門儀範), which was first published in 1935. The latter text remains to this day the standard ritual text of the Chogye Order of Korean Buddhism (Taehan Pulgyo Chogyejong 大韓佛敎曹溪宗), the largest Buddhist denomination in the Republic of Korea (McBride 2019a). The only differences are that these modern versions add the invocative salutation or expression of faith namaḥ (lit. nammu, but read namu 南無) before each of the bodhisattva names and add the line “Homage to the Original Master, the Buddha Amitābha” 南無本師阿彌陀佛 afterward (Ch’oe and An 1931, 17a; An 1984, 1.95). In addition, the Siddhaṃ for the “The Great Dhāraṇī of Spiritually Sublime Phrases” in the Five Great Mantras is the same as the Siddhaṃ in these two ritual manuals from the 1930s (Ch’oe and An 1931, 17b–18b; An 1984, 1.95–96).

5. Basic Dhāraṇī of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara

The “Basic Dhāraṇī of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara” is short for the “Basic Dhāraṇī of the Thousand-Handed Thousand-Eyed Avalokiteśvara” (Ch’ŏnsu ch’ŏnan Kwanjajae posal kŭnbon tarani千手千眼觀自在菩薩根本陀羅尼). The transliteration of this dhāraṇī is attributed to Amoghavajra (Odae chinŏn 1635, 29a). The Korean Five Great Mantras does not include an invocative petition for this dhāraṇī. In addition, this dhāraṇī does not appear to have been included in the original Five Great Mantras collection from the Koryŏ period, and was probably added sometime later as a sixth dhāraṇī in some versions with the colophon dated 1485.11

Of all the dhāraṇīs in this Korean collection, this one most closely corresponds to the received version of a “basic dhāraṇī” (genben tuoluoni 根本陀羅尼) in a text translated by Amoghavajra, the Ritual Manual Sūtra on Cultivating Practices of the Thousand-Handed Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara of the Vajraśekara Yoga (Jin’gangding yuqie qianshou qianyan Guanzizai pusa xiuxing yigui jing 金剛頂瑜伽千手千眼觀自在菩薩修行儀軌經, T 1056). Both dhāraṇīs are forty phrases, and there are only slight variations in the Sinographs used in the transliteration (T 1056, 20.79b18–80a5; Odae chinŏn 1635, 29a–32a). This dhāraṇī is part of the corpus of related dhāraṇīs associated with the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī, such as we have seen in the previous two sections. Thus, three of the six dhāraṇīs published in the Five Great Mantras are closely associated with the cult of Avalokiteśvara, suggesting the widespread popularity and importance of Avalokiteśvara worship in Korea during the Koryŏ and Chosŏn periods.

6. Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī

The Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī was and is one of the most widely popular spells among Buddhists and most studied dhāraṇīs among scholars. Manuscripts of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī-sūtra have been discovered in Gilgit, written on birchbark (von Hinüber 1981, 1987–1988, 2004, 2006). Gergely Hidas translated and analyzed five Gilgit fragments and fifteen selected eastern Indian and Nepalese manuscripts of the Mahāpratisarā-Mahāvidyārājñi, which provide important evidence on how the dhāraṇī was used as an amulet in the Indian and Central Asian contexts (Hidas 2003, 2007, 2012). A Sanskrit recension of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī-sūtra is the first and most detailed of the group of five dhāraṇī-sūtras that circulated together in the Pañcarakṣā collections of the modern Newari Buddhist tradition (Lewis 2000, pp. 121–46; Hidas 2003). Amulets of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī have been found in the medieval Chinese context, as well as prints of Siddhaṃ version of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī found in funerary contexts (Drège 1999–2000; Copp 2008; 2014, pp. 59–140). Even a modern edition of the Sanskrit Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī has been packaged for consumption by lay Korean Buddhists (Pak 2021).

The complete text of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī in Buddhist-Chinese exists in two recensions, a translation by Baosiwei 寶思惟 (*Ratnacinta or *Manicintana, d. 721) titled Foshuo suiqiu jide dazizai tuoluoni shenzhou jing佛說隨求即得大自在陀羅尼神呪經 (T 1154) and a retranslation by Amoghavajra titled *Samanta-jvalāmālā viśuddhaisphūrita-cintāmaṇi-mudrā-hṛdayāparājitā mahāpratisāravidyā dhāraṇī (Pubian guangming qingjing chisheng ruyi baoyinxin wunengsheng damingwang dasuiqiu tuoluoni jing普遍光明清淨熾盛如意寶印心無能勝大明王大隨求陀羅尼經, T 1153). Elsewhere I have compared the two translations, described the popularity of the spell, and problematized the evidence regarding a third version of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī, which is said to have been a correction of Baosiwei’s translation executed by Vajrabodhi (Jin’gangzhi金剛智, 671–741) (McBride 2018, pp. 57–73).

The primary dhāraṇī, or “basic spell,” found in the sūtra was relevant to a broad range of practitioners in Korea because multiple versions of the principal dhāraṇī were published and circulated in a variety of forms in the Chosŏn period. On the peninsula, as in Japan, the received edition of Amoghvajra’s translation—or at least the name Amoghavajra—was more favored in the Buddhist community during the Koryŏ and Chosŏn periods. The name Amoghavajra appears to have conferred legitimacy and authority more than the names of other Tang-period translators of dhāraṇīs. Special collections including a transliteration of the main dhāraṇī attributed to Amoghavajra and related ritual texts continued to be published in Korea at least six times. Although the dates of two editions are unclear or unknown, woodblocks were cut and the dhāraṇī was published either by itself or as part of a collection of dhāraṇīs and mantras in 1476, 1485, 1550, 1569, 1635, 1729, and 1854 (Sørensen 1991–1992, p. 174 n. 66; Tongguk Taehakkyo Pulgyo Munhwa Yŏn’guwŏn 1982, p. 371). Due to the assistance of Sin Haech’ŏl, the librarian who controls the old books collection at Dongguk University, I was able to view several of these texts in the possession of the Dongguk University Library, on 29 June 2011 and 27 June 2014.

The invocative petition (kyech’ŏng 啓請; Skt. adhyeṣanā), which is in the form of a gāthā-poem with seven Sinographs per line, has a title suggesting that it was presented to the Tang court in association with a translation of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī: “Invocative Petition Regarding the Dhāraṇī for the Accomplishment of Spiritual Metamorphosis and Empowerment of Conferring Whatever One Wishes, for the Achievement of the Most Superior Esoteric Buddhahood of the Yoga of the Adamantine Pinnacle, Spoken by the Buddha” (Pulsŏl kŭmgangjŏng yuga ch’oesŭng pimil sŏngbul sugu chŭktŭk sinbyŏn kaji sŏngch’wi tarani kyech’ŏng 佛說金剛頂瑜伽最勝秘密成佛隨求卽得神變加持成就陀羅尼啓請). This title is different from the received title of Amoghavajra’s translation and suggests a link to the so-called Vajraśekhara (jin’gangding 金剛頂) family of scriptures (Misaki 1977). The petition is neither mentioned in Collected Documents of the Trepiṭaka Amoghavajra Bestowed with a Posthumous Title and Honors in the Reign of Daizong (Daizong chaozeng sikong dabian zhengguangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji 代宗朝贈司空大辨正廣智三藏和上表制集, T 2120), which comprises Amoghavajra’s official correspondence with Tang emperors, other letters, documents, and biographical writings, which was compiled by Yuanzhao圓照 (fl. 785–804) nor is it found in the received Buddhist canon in literary Sinitic. The Collected Documents, reports, however, Amoghavajra’s presentation of a Sanskrit version of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī (Fanshu dasuiqiu tuoluoni yiben 梵書大隨求陀羅尼一本) to the court in the time of Suzong 肅宗 (r. 756–762), the chanting of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī and the Mahāpratisarā-mantra along with other sūtras and spells on birthdays, and the intonation of a “Mahāpratisarā essay” (feng Suiqiu zhang 諷隨求章) (T 2120, 52.829b4–15, 835c28–836a2, 836a27–b3, 848c5–6). A translation of the petition is as follows:

| 稽首蓮華胎藏敎 | I humbly kowtow to the teaching of the lotus flower womb treasury, |

| 無邊淸淨摠持門 | The approach of the dhāraṇī of boundless cleanliness and purity, |

| 普遍光明照十方 | The ten directions of universal light and radiance, |

| 燄鬘應化三千界 | The three thousand worlds of the response and transformation of flaming fair hair, |

| 如意寶印從心現 | The jeweled seal of wish-fulfillment follows the manifestations of the mind, |

| 無能勝主大明主 | The lord who is unable to be overcome, the lord of great brilliance, |

| 常住如來三昧中 | Who constantly abides in the samādhi of the tathāgata, |

| 超證瑜伽圓覺位 | Transcends to and realizes the level of Yoga and Perfect Enlightenment. |

| 毘盧遮那尊演說 | The Honored Vairocana delivered a sermon |

| 金剛手捧妙明燈 | Vajradhara held the lamp of sublime brilliance in his hands |

| 流傳密語與衆生 | Circulated esoteric words with living beings |

| 悉地助修成熟法 | Siddhis aid in cultivating ripe dharmas |

| 五濁愚迷心覺悟 | The five impurities12 deceive and delude the awakening and enlightenment of the mind. |

| 誓求無上大菩薩 | Swear to seek the unsurpassed great bodhisattvas |

| 一常讚念此微詮 | Who all constantly praise and recollect this subtle explanation, |

| 得證如來無漏智 | Attain the realization of the Tathāgata’s knowledge that is devoid of outflows, |

| 諦想觀心月輪際 | True perception visualizes the limits of the moon-wheel of the mind |

| 凝然不動觀本尊 | The Honored One who gazes fixedly, is immovable, and observes the origin, |

| 所求願滿稱其心 | Is he who pursues vows and fully states his mind |

| 故號隨求能自在 | Hence, he is called the Self-Existing One Who Is Able to Confer Whatever One Wants |

| 依敎念滿洛叉遍 | Depending on teaching and recollecting the universality of abundant lakṣas |

| 能攘宿曜及災神 | It is able to resist the lodges, luminaries, and gods of calamities |

| 生生値此陀羅尼 | At the time they are produced, this dhāraṇī |

| 世世獲居安樂地 | Obtains residence in the land of peace and bliss generation after generation |

| 見世不遭諸枉橫 | Sees that the world does not encounter all vain and cross things |

| 火焚水溺及災殃 | From being burned by fire and drowned by water to injured by calamities |

| 不被軍陣損身形 | [And] does not suffer injury to one’s physical form on the battlefield |

| 盜賊相逢自安樂 | Thieves and robbers meet each other from peace and bliss, |

| 縱犯波羅十惡罪 | Are allowed to break the pāramitās and [commit] the sins of the ten evil acts13 |

| 五逆根本及七遮 | The root origin of the five heinous crimes14 and seven heinous crimes.15 |

| 聞誦隨求陀羅尼 | Hearing and chanting the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī |

| 應是諸惡皆消滅 | It responds to all these evils and eradicates them all. |

| 陁羅尼力功無量 | The power and merit of the dhāraṇī are limitless, |

| 故我發心常誦持 | So I arouse the aspiration to constantly chant it and bear it [in mind]. |

| 願廻勝力施含靈 | I vow to turn its victorious power and bestow it on living creatures |

| 同得無爲超悉地 | So that together they may obtain the siddhi that transcends the unconditioned. (Odae chinŏn 1635, 32a–33a; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 1a–3b; Kim 2010, p. 238) |

Although a petition composed in gāthā form would be appropriate for many of these occasions, thus serving as circumstantial evidence for its authenticity, many works probably not composed or translated by Amoghavajra have been ascribed to him to lend them validity, legitimacy, and authority. An example of this situation will be described in detail below.

The longer version of the great dhāraṇī (Odae chinŏn 1635, 33a–55a; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 4a–14b) starts with the same first lines as the received text of the great dhāraṇī as found in a ritual manual (yigui, Kor. ŭigwe 儀軌) attributed to Amoghavajra, but diverges afterwards (T 1155, 20.645a1–4). Although this ritual manual is not preserved in the Koryŏ Buddhist Canon, one like it probably circulated in Silla 新羅 (ca. 300–935) or Koryŏ Korea because a prose text titled “Efficacious Resonance of the Mahāpratisarā” (Sugu yŏnghŏm 隨求靈驗), which will be discussed below, begins in the same way.

What is more intriguing is that most of the seven short spells that follow the great dhāraṇī in the second section are the same as six of the eight dhāraṇīs found after the basic dhāraṇī in Baosiwei’s translation of the Mahāpratisarā, and one of the short mantras in the ritual manual mentioned above. More precisely, (1) “The true word of the mind of all the tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae sim chinŏn 一切如來心眞言; Odae chinŏn 1635, 55b–56b; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 15a–b) in the Chosŏn-period text is the same as “The spell of the mind of all the buddhas” (Ch. yiqie foxin zhou一切佛心呪) in Baosiwei’s translation (T 1154, 20.639c23–640a3; cf. 644a12–20); (2) “The true word of the seal of the mind of all the tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae simin chinŏn 一切如來心印眞言; Odae chinŏn 1635, 56b–57a; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 15b) is the same as “The spell of the seal of the mind of all the buddhas [or spell for sealing the mind of all the buddhas]” (Ch. yiqie foxin yinzhou一切佛心印呪; T 1154, 20.640a4–7; cf. 644a21–24); (3) “The true word of consecration of the mind of all the tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae sim kwanjŏng chinŏn 一切如來心灌頂眞言; Odae chinŏn 1635, 57a–b; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 16a) is the same as “The spell of consecration” (Ch. guanding zhou灌頂呪; T 1154, 20.640a8–13; cf. 644, a25–b2); (4) “The true word of the seal of the consecration of all tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae kwanjŏngin chinŏn 一切如來灌頂印眞言 (Odae chinŏn 1635, 57b–58a; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 16b) is the same as “The spell of the seal of consecration [or spell for sealing the consecration]” (Ch. guanding yinzhou灌頂印呪; T 1154, 20.640a14–17; cf. 644b3–5); (5) “The true word for drawing a strict line of demarcation for all the tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae kyŏlgye chinŏn一切如來結界眞言; Odae chinŏn 1635, 58a–b; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 16b–17a) is the same as “The spell for drawing a strict line of demarcation” (jiejie zhou結界呪, Skt. sīmabandha; T 1154, 20.640a18–21; cf. 644b6–8); (6) “The true word of the mind within the mind of all the tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae simjungsim chinŏn 一切如來心中心眞言 (Odae chinŏn 1635, 58b; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 17a) is the same as “The spell of the mind within the mind” (Ch. xinzhongxin zhou心中心呪; T 1154, 20.640a25–27; cf. 644b12–15); and (7) “The true word the follows the mind of all the tathāgatas” (ilch’e yŏrae susim chinŏn 一切如來隨心眞言; Odae chinŏn 1635, 59a; Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 17a–b) is the same as “The true word in the mind” (xinzhong zhenyan 心中真言) in the ritual manual attributed to Amoghavajra (T 1155, 20.648b26–c2). Thus, the body of mantras that comprise the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī, which circulated in the Chosŏn period, is at least a composite of materials translated or written by—or at least attributed to—Amoghavajra and Baosiwei, and perhaps other writers.

Efficacious Resonance of the Mahāpratisarā (Sugu yŏnghŏm 隨求靈驗) is believed by scholars to be one of the oldest Buddhist texts of the Chosŏn period written using both Sinographs and the vernacular script, having been first published in 1476 (An 1987; Kim 2010, p. 80). The Dongguk University library preserves an almost complete copy of the 1569 reprinting of this document, which was originally published at Ssanggye Monastery 雙磎寺 in Ŭnjin 恩津 in Ch’ungch’ŏng Province (Hong 1986, p. 421; Kim 2010, p. 81). The text is divided into four parts. The first part is an introduction that contains the previously discussed invocative petition informing the buddhas and bodhisattvas and requesting their protection before one vocally chants the sūtra attributed to Amoghavajra (Sugu yŏnghŏm 1569, 1a–3b), a short version of the great dhāraṇī that confers whatever one wants (Taesugu taemyŏngwang taedarani 大隨求大明王大陀羅尼), and a statement that the larger dhāraṇī that follows was translated by Amoghavajra (3b–4b). As analyzed above, the second part is comprised of the great dhāraṇī from the text written solely in the Korean vernacular (4a–14b), as well as seven other mantras with their names provided first in the Korean vernacular script in one line and in Sino-Korean in the following line and the spells themselves in the Korean vernacular (15a–17b). The third part of the text is the “Syugu ryŏnghŏm” 슈구령험 (Efficacious Resonance of the Mahāpratisarā), which explains why and how to use this spell in an efficacious manner (18a–26b). This part will be discussed in the section below on Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance. The fourth part is a vernacular transcription of the Uṣṇīṣavijaya-dhāraṇī (Pulchŏng chonsŭng tarani 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼) (27a–29a). Although no information is listed regarding who executed the transliteration of the dhāraṇīs and wrote or translated the section titled “Efficacious Resonance,” because the material is closely related to material in the Odae chinŏn published in 1485 under the guidance of Queen Insu, Hakcho probably translated the “Efficacious Resonance” section from material existing from the Koryŏ period.

7. Buddhoṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī

Texts with the words “Buddha’s crown” (foding, Kor. pulchŏng 佛頂), referring to the Buddha’s or a buddha’s uṣṇīṣa, constitute a large and complex lineage of texts (Misaki 1977). Although the dhāraṇī I refer to as the Buddhoṣṇīsa-dhāraṇī (taebulchŏng tarani 大佛頂陀羅尼) in the Five Great Mantras is attributed to Amoghavajra, neither the Siddhaṃ nor the Sinographic transliteration of the incantation corresponds to extant canonical versions of the spell. The “Invocative Petition for the Buddhoṣṇīsa-dhāraṇī” (Taebulchŏng tarani kyech’ŏng 大佛頂陁羅尼啓請), which inaugurates the section, is a curious composition. The language of the petition suggests that it may have been originally crafted for use in connection to the body of texts associated with the Śūraṃgama-dhāraṇī (Lengyan zhou 楞嚴呪), because the second line invokes the name, although much of the petition is extremely conventional in terms of the promises it makes regarding the efficacy of chanting the dhāraṇī.

| 稽首光明大佛頂 | I humbly kowtow to the radiant Great Buddha’s crown, |

| 如來萬行首楞嚴 | The śūraṃgama16 of the myriad practices of the Tathāgata. |

| 開無相門圓寂宗 | He discloses the approach to the markless and the core teaching of perfect quiescence; |

| 字字觀照金剛定 | In each and every word one contemplates the vajra absorption. |

| 瑜伽妙音傳心印 | The sublime sounds of Yoga transmit the mind-seals, |

| 摩訶衍行揔持王 | The king of the dhāraṇī of Mahāyāna practice, |

| 說此秘密悉怛多 | Explains this esoteric Sitāta[patra-dhāraṇī?], |

| 解脫法身金剛句 | Delivering the vajra phrases of the dharma-body. |

| 菩提力大虛空量 | The power of bodhi and the capacity of great empty space, |

| 三昧智印果無邊 | The fruits of samādhi and wisdom-seals are boundless. |

| 不持齋者是持齋 | Not observing abstinence is observing abstinence; |

| 不持戒者名持戒 | Not observing the precepts is called observing the precepts |

| 八萬四千金剛衆 | The throng of eighty-four thousand vajradevas |

| 行住坐臥每相隨 | Walking, standing, sitting, and lying down—always accompany one [in all situations]. |

| 十方法界諸如來 | All tathāgatas in the dharma realms of the ten directions |

| 護念加威受持者 | Protect and keep in mind and empower the majesty of those who receive and observe them. |

| 念滿一萬八千遍 | Chanting them a full eighteen thousand times |

| 遍遍入於無相定 | In each and every individual [chant] one enters the markless absorption |

| 号稱堅固金剛憧 | Which designates a firm vajra yearning |

| 自在得名人勝佛 | Unrestrained, it acquires the name: Buddha Victorious Over Men |

| 縱使罵詈不為過 | Even if abusive language is not excessive |

| 諸天常聞說法聲 | All gods constantly hear the sounds of the dharma being preached |

| 神通變化不思議 | Spiritual penetrations change into the inconceivable; |

| 陁羅尼門最第一 | The approach of dhāraṇī is the greatest! |

| 大聖放光佛頂力 | The Great Saint emits light by means of the power of the Buddha’s crown; |

| 掩惡揚善證菩提 | Coving up unwholesomeness and propagating wholesomeness, one realizes bodhi. |

| 唯聞念者瞻蔔香 | Merely hearing chants, campaka17 incense, |

| 不齅一切餘香氣 | Does not smell all remaining incense fragrances |

| 設破二百五十戒 | Establishing and breaking the two hundred and fifty precepts |

| 及犯佛制八波羅 | And violates the Buddhist regulations, the pārājikas |

| 聞念佛頂大明王 | Hearing and chanting the Buddhoṣṇīṣa-mahā-vidyā-rāja |

| 便得具足聲聞戒 | One soon acquires the full precepts of the śrāvakas |

| 若人殺害怨家衆 | If a person kills an enemy family or throng, |

| 常行十惡罪無變 | Constantly doing the ten unwholesome actions, and his sins are unchanged, |

| 蹔聞灌頂不思議 | And momentarily hears of the inconceivability of consecration, |

| 恒沙罪障皆消滅 | His sins and hindrances, as much as the sands of the Ganges, will all be eradicated. |

| 現受阿鼻大地獄 | [If] he is actively experiencing Avīcī, the Great Hell, |

| 鑊湯鑪炭黑繩人 | Or a person in [the hells of] cauldrons of molten iron, stoves of burning coals, or black rope; |

| 若發菩提片善心 | If he arouses bodhi, a piece of a wholesome aspiration, |

| 一聞永得生天道 | All at once he will hear and perpetually obtain rebirth in the Path of the Gods. |

| 我今依經說啓請 | I now relying on this sūtra, explain this invocative petition, |

| 無量功徳普莊嚴 | Immeasurable meritorious virtues and universal ornamentation |

| 聽者念者得揔持 | Those who hear and those who chant [will] attain [this] dhāraṇī |

| 同獲涅盤寂滅樂 | And together obtain nirvāṇa, the bliss of quiescence. (Odae chinŏn 1635, 59a9–92b3; Kim 2010, p. 256). |

This gāthā-like invocative petition corresponds to—but is not exactly the same as—an invocative petition found at the beginning of the Dhāraṇī on the Great Buddha’s Crown of the White Parasol of All the Tathāgatas (Yiqie rulai baisan’gai dafoding tuoluoni一切如來白傘蓋大佛頂陀羅尼), which is attributed to Amoghavajra and preserved in the Fangshan Stone Canon (Fangshan shijing 房山石經; F 1048, 27.390a2–25). This dhāraṇī is one of several extant versions of the *Buddhōṣṇīṣa-prabhā-mahā-sitātapatra-dhāraṇī, or Sitātapatra-dhāraṇī (Baisan’gai zhou 白傘蓋呪, T 944A), which scholars have demonstrated to be closely connected to the Śūraṃgama-dhāraṇī (Keyworth 2022, pp. 102–4). One scholar thinks that the Buddhōṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī in the Five Great Mantras corresponds to the dhāraṇī in the seventh roll of the Śūraṃgama-sūtra (Ok 2018, p. 100). Roll seven presents two dhāraṇīs, one is 439 phrases (T 945, 19.134a1–136c14); and the other, at the end of the roll is 427 phrases (T 945, 139a14–141b13). The first dhāraṇī in roll seven is the “canonical version,” while the second is the version that circulated in China during the Ming (1368–1644) and, later, Qing 淸 (1644–1911) periods. The dhāraṇī associated with the invocative petition in the Fangshan Stone Canon is only 480 phrases (F 1048, 27.390a28–395b22), while the dhāraṇī in the Five Great Mantras is 510 phrases (Kim 2010, pp. 264–71). Although they are relatively close in the number of phrases, which could vary depending on where the transliterated text was parsed, the simple fact remains that these and the canonical versions of the spell represent different but related versions of the dhāraṇī, and that versions of the dhāraṇī that circulated popularly were not the same as the “canonical” version.

8. Uṣṇīṣavijaya-dhāraṇī

Like other dhāraṇīs, Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī refers to a corpus of spells that circulated under the general name of Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī. Much scholarship has been published on this dhāraṇī because many versions of both the spell and the whole dhāraṇī-sūtra were carved on stone pillars and mortuary pillars in China during the Tang and succeeding periods (Tanaka 1933; Ogiwara 1938; Nasu 1952; Liu 1996, 1997, 2003, 2008; Sasaki 2008, 2009; Kuo 2007, 2012, 2014; in English, see Kroll 2001; Copp 2005, pp. 171–236; Copp 2014, pp. 141–96). Nine-tenths of the dhāraṇī-pillars in China are engraved with the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī (Kuo 2014). Although most of the foregoing translations and/or transliterations of dhāraṇīs have been attributed to, or at least linked to Amoghavajra in some way, the Five Great Mantras unequivocally attributes the translation of sūtra associated with the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī, the Sūtra on the Superlative Dhāraṇī of the Buddha’s Crown (Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jing 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經, T 967), to the trepiṭaka-śramaṇa *Buddhapālita (Fotuoboli佛陁波利, fl. late seventh century) from Kashmir. The translation of the sūtra attributed to Buddhapālita is the most famous of five known translations.18

A Sanskrit text of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī was apparently brought to China in the late sixth century.19 More Sanskrit manuscripts of the dhāraṇī arrived during the seventh century, and five translations were completed in a short span of time in the late 670s and 680s, most likely because the dhāraṇī was deemed relevant to Buddhist attempts to treat Tang emperor Gaozong’s 高宗 (r. 649–683) poor health. The Tang monk Yancong 彥悰 (fl. 650–688), who participated on the translation team, reports that the first was done in 679 by the court official Du Xingyi 杜行顗 and a general named Dupo 度婆 (T 968; T 969, 19.355a27–28). In 682, Gaozong ordered a new translation to be made, which did not include taboo Sinographs (T 969, 19.355a26–b3). This was accomplished by Divākara (Dipoheluo 地婆訶羅, 613–688), a monk from central India, with the assistance of the same Du Xingyi (T 969, 19.355b4–11). The following year, about 683, a one-roll version of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī-sūtra. This is the translation attributed to *Buddhapālita, which was accomplished with the help of the Chinese monk Shunzhen 順貞 (T 967, 19.349b1–c19). In 685, a year or so after Gaozong’s death, a fourth translation attributed to Divākara was made just prior to the monk’s return to India (T 2154, 55.564a3–4; T 2128, 54.544a). Several years after his return from India, Yijing 義淨 (635–713) made the fifth and last translation of the sūtra in 710 (T 971). *Buddhapālita’s version is the only one to appear on dhāraṇī-pillars. The reason for the popularity of this translation is probably because a story circulated about this monk’s encountering the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī on Mt. Wutai 五台山 in the guise of an old man. The old man reportedly told *Buddhapālita to return to India so he could bring a Sanskrit version of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī to China. The legendary circumstances of this narrative are depicted in two Dunhuang murals in Dunhuang associated with illustrations of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī-sūtra (T 967, 19.349b1–c19; Kuo 2014, p. 356).

The received, canonical edition of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī does not have an associated invocative petition. The “Invocative Petition to the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī” (Pulchŏng chonsŭng tarani kyech’ŏng 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼啓請) presented in the Five Great Mantras is shorter and more simply constructed than the long, detailed invocative petitions attributed to Amoghavajra.

| 稽首千葉蓮華藏 | I humbly kowtow to the thousand-leaf lotus flower storehouse [realm], |

| 金剛座上尊勝王 | The Victorious King of the Adamantine High Seat, |

| 爲滅七返傍生難 | For eradicating the disasters associated with seven rebirths |

| 灌頂摠持妙章句 | [There are] consecrations and dhāraṇīs, subtle syllables and phrases. |

| 八十八億如來傳 | Eighty-eight million tathāgatas transmit |

| 願舒金手摩我頂 | And vow to stretch out their golden hands to touch the crown of my head |

| 流通變化濟舍靈 | To circulate, transform, and bring about my efficacy |

| 故我一心恒讚頌 | Hence, I, with a single mind, always sing its praises. (Odae chinŏn 1635, 92b4–7) |

This invocative petition is extremely generic; and yet, unlike the invocative petition associated with Buddhoṣṇīsa-dhāraṇī discussed above, this gāthā specifically references both consecrations (kwanjŏng, Ch. guanding 灌頂) and the ritual act of touching the crown of an aspirant’s head (majŏng, Ch. moding 摩頂), which is one of the crowning experiences an advanced bodhisattva has just prior to attaining complete enlightenment.

The received canonical version of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī is broken into 85 phrases, but the version found in the Korean Five Great Mantras is 66 phrases (T 967, 19.350b25–c28; Odae chinŏn 1635, 93a–96b; Kim 2010, pp. 276–77). In addition, the Five Great Mantras supplements the longer or primary Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī with two “heart spells”: a “Greater Superlative Heart Spell” (chonsŭng taesim chu 尊勝大心呪) and a “Lesser Superlative Heart Spell” (chonsŭng sosim chu 尊勝小心呪) (Odae chinŏn 1635, 97a–b; Kim 2010, pp. 333–34). The “Greater Superlative Heart Spell” and the “Lesser Superlative Heart Spell” are very similar to two mantras found in the Tang monk Fachong’s 法崇 (fl. 760s–770s) commentary titled Record of the Meaning of Doctrinal Traces the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī-sūtra (Foding zunsheng tuoluoni jing jiaoji yiji 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經教跡義記, T 1803), the “Greater Superlative Mantra” (Foding zunsheng daxin zhenyan 佛頂尊勝大心真言) and the “Lesser Superlative Heart Mantra” (zunsheng xiaoxin zhenyan 尊勝小心真言) (T 1803, 39.1032c25–29).

- Greater Spell

Korea: 唵 阿蜜哩多 鉢囉陛 尾布攞蘖陛 母地娑多迷 悉地悉地 麽賀蘖陛都嚕都嚕 娑嚩賀Om amirida parabye miboraalbye mojisadamye sijisiji mahaalbye torodoro sabaha(Odae chinŏn 1635, 97a1–7)

Tang: 唵 阿密哩多 鉢羅陛 微布擇蘖陛 鉢羅菩提 摩訶蘖陛 都魯都魯 娑嚩賀Om amirida parabye mibot’aegalbye parabori mahaalbye torodoro sabaha(T 1803, 39.1032c25–27)

- Lesser Spell

Korea: 唵 阿蜜哩多 惹縛底娑嚩賀Om amirida abajisabaha(Odae chinŏn 1635, 97a8–b2)

Tang: 唵阿密里多諦 惹縛底娑嚩賀Om amiridadye abajisabaha(T 1803, 39.1032c28–29)

Curiously, Fachong’s commentary also includes a mantra that might be rendered loosely in English as the “Heart of Hearts Superlative Mantra” (zunsheng xinzhongxin zhenyan 尊勝心中心真言; T 1803, 39.1033a1–2), which does not appear in the editions of the Five Great Mantras that I have been able to analyze. The Korean and Tang spells are quite similar, but both are completely different from another set of similarly titled spells recorded in a large compendium of dhāraṇīs and mantras, Collection of Dhāraṇīs in the Esoteric Storehouse of the Most Superior Vehicle of the Śākyamuni’s Teachings (Shijiao zuishangsheng mimizang tuoluoni ji 釋教最上乘秘密藏陀羅尼集, F 1071), which was compiled by the Liao monk Xinglin 行琳 (d.u.) of Da’anguo Monastery in the Upper Capital 上都大安國寺. These short spells, called the “Greater Heart Dhāraṇī of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā” (Foding zunsheng daxin tuoluoni 佛頂尊勝大心陁羅尼) and “Lesser Heart Dhāraṇī of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā” (Foding zunsheng xiaoxin tuoluoni 佛頂尊勝小心陁羅尼), unlike the Korean and Tang versions, both begin with the invocative expression nama 曩莫/曩謨 (F 1071, 28.19b19–20a2, 20a3–6).

9. Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance

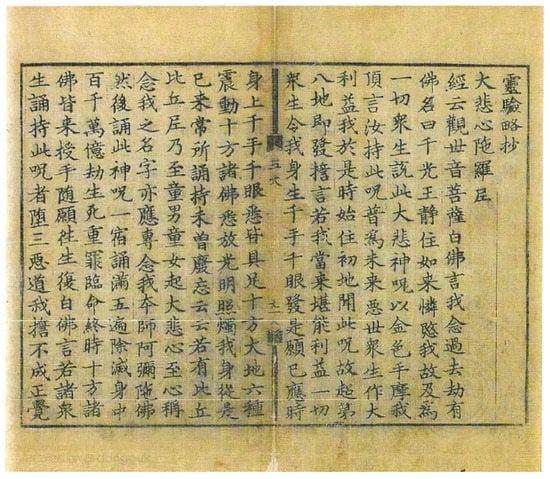

Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance comprises four short extracts associated with four of the dhāraṇīs found in the Five Great Mantras. These sections are titled: “Dhāraṇī of the Heart of Great Compassion,” or perhaps simply Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī (Taebisim tarani 大悲心陀羅尼), Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī (Sugu chŭktŭk tarani 隨求卽得陀羅尼), Buddhōṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī (Taebulchŏng tarani 大佛頂陀羅尼), and Uṣṇīṣavijaya-dhāraṇī (Pulchŏng chonsŭng tarani 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance (Yŏnghŏm yakch’o) in literary Sinitic (Odae chinŏn 1485B, p. 41).

The section on the Nīlakaṇṭha-dhāraṇī paraphrases the part of Bhagavaddharma’s translation of the sūtra (T 1060) in which Avalokiteśvara reports to the Buddha that in a past kalpa (a Buddhist eon), a buddha named Tathāgata Abiding in Quiescence, King of a Thousand [Kinds of] Light (Ch’ŏn’gwangwang Chŏngju Yŏrae 千光王靜住如來) gave him the “spirit spell of great compassion” (taebi sinju 大悲神呪) while touching the crown of his head. Avalokiteśvara reported that upon hearing the spell, he jumped to the eighth stage of the bodhisattva path and vowed to benefit all living beings and requested a body with a thousand hands and a thousand eyes by which to accomplish the vow. The bodhisattva promises that if monks and nuns and young men and young women arouse the “mind of great compassion,” recollect Avalokiteśvara’s name, and chant this spirit-spell a full five times in one night, they will eradicate the weighty sins accumulated in the cycle of rebirth and death over millions of kalpas. Avalokiteśvara promises that if people chant and bear in mind this spell, they will avoid falling into the three evil paths of rebirth, be born in buddha-lands, obtain the eloquence of limitless samādhis, and accomplish all they seek in their present lives. Women who seek to avoid rebirth again in a female body will attain their desire. People who commit the ten evil acts and five heinous crimes, and perpetuate other odious acts against the Buddhist church and the Buddhist teaching, will be able to expiate their unwholesome karma. The bodhisattva also promises protection from inclement forces of nature, such as violent winds, for those who chant and recite the spell (Odae chinŏn 1635, 98a–100b; Kim 2010, pp. 83–84).

The section on the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī paraphrases Amoghavajra’s ritual manual (T 1155) in which the Bodhisattva Eradicator of the Evil Destinies (Myŏrakch’wi posal 滅惡趣菩薩) addresses the Buddha Vairocana requesting a means by which he can liberate living beings from their weighty sins so they do not fall into Avīcī Hell. Vairocana responds that he has put in place a secret method that is the best in making sins disappear and attaining Buddhahood: the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī. He promises that if people hear the name of this mantra (lit. “true word”) or if they are familiar with it or recite it by heart, all the gods (both good and bad, and even including Māra) will always follow and defend them. If people recite it by heart and wear it on their persons, they will not fall into hell, even if they commit all manner of weighty sins. If people wear even so little as one or two graphs, one passage or one section of this mantra on the crown of their heads (chŏngdae 頂戴), such people will be no different from all the buddhas. The text then asserts that if buddhas do not obtain this true word they will not obtain buddhahood, and that if brahmans of heterodox religions obtain it, they will achieve the way to buddhahood quickly. The section then illustrates this idea by narrating the story of the brahman *Kobāk (Kubak 俱愽) from Magadha, who rejected the dharma and killed all manner of animals. When he died, King Yama and King Śakra decreed that he should go to Avīcī Hell; but when he was sent there, it transformed into a lotus pond. Confused, Śakra asked Śākyamuni for an explanation of this divine transformation. The Buddha directed him to observe the man’s skull. Through detective work, Śakra realized that *Kobāk had been buried not far from a monastery, from whence one graph of a decayed copy of the Mahāpratisarā-mantra (Sugu chinŏn 隨求眞言) had been blown by the wind and collided with the deceased person’s bones. Such is the power of the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī. The section goes on to narrate a story of a king named Bestowed of Brahmā (Pŏmsi 梵施; Skt. *Brahmādatta?), different from the story in Baosiwei’s translation of the sūtra (T 1154). Bestowed of Brahmā sought to execute a man for his weighty sins, but since the man wore the Mahāpratisarā-dhāraṇī on his arm, the sword kept breaking in several pieces. The king then ordered him to enter a cave where he expected that he would be eaten by yakṣas (demons), but the yakṣas, instead, circumambulated and worshiped him because bright light emitted from his face due to the power of the spell. After another attempt to kill him failed, Bestowed of Brahmā awarded him with official rank and made him ruler over a city (Odae chinŏn 1635, 100b–103a; Kim 2010, pp. 105–6; full English translation in McBride 2018, pp. 87–91).

The section on the Buddhōṣṇīṣa-dhāraṇī begins by paraphrasing the Śūraṃgama-sūtra (Shoulengyan jing 首楞嚴經), in which Buddha explains to Ānanda that this “subtle and sublime passage on the light of the Buddha’s uṣṇīṣa” (Pulchŏng kwangch’wi mimyojanggu 佛頂光聚微妙章句) causes all the buddhas of the ten directions to be born and achieve complete and total enlightenment. This spell subjugates all demons and heterodox religions, and will cause all those who bear it in mind to attain the powers and accomplishments of buddhas. More important for ordinary people is that they will be freed from many troubles and will be liberated from the cycle of rebirth and death; and in addition, they will be saved from numerous kinds of calamities, such as those brought about by warfare, capricious kings, and ferocious monsters. Those familiar with and who practice this spell will understand Buddhist truth of causation as it effects their lives, and it will strengthen their resolve and ability to observe Buddhist precepts. If living beings in the degenerate age of the decline of the dharma (malbŏp 末法) recite this spell or teach others to recite it, poison will not be able to harm them and noxious fumes will be transformed in their mouths into sweet dew (kamno 甘露; Skt. amṛta), and they will obtain boundless meritorious virtues (Odae chinŏn 1635, 103a–104b; Kim 2010, p. 129).

The final section on the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī narrates the story of the deity Supratiṣṭha (Sŏnju 善住; Abiding in Wholesomeness) who resided in the Heaven of the Thirty-three Gods (Torich’ŏn忉利天, Skt. Trayastriṃśās). This god usually spent his time frolicking with all the goddesses. However, in the middle of the night, Supratiṣṭha heard a voice saying that he would be reborn in the human world, suffer through rebirth as an animal seven times, and then fall into hell. When finally freed from hell, he will be reborn in poverty and obscurity. Seeking to avoid this fate, the deity sought the Lord Śakra’s advice. Śakra said that only the Buddha can cause you to avoid this suffering. In response, the Buddha taught the Uṣṇīṣavijayā-dhāraṇī, asserting that if people just hear it once, all the unwholesome karma one has committed in previous lifetimes causing one to be reborn in all the hells will be eradicated. In addition, he promised that if a person’s life-force is exhausted, thinking of and chanting this spell will add it all back to the individual again and will completely purify all actions of body, speech, and mind. The text then goes on to articulate the method for carrying or maintaining this dhāraṇī (chi tarani pŏp 持陀羅尼法) on one’s person for benefits (although the instructions do not specify how one should carry it): people should first bathe, put on clean clothes, and observe the precept of abstinence (fasting, avoiding sex, etc.) for a full day during the time of the waxing moon—and chant this dhāraṇī. If one chants it a thousand times, one’s lifespan will be increased and will be free from suffering from illness. The dhāraṇī protects against epidemic illnesses, and can be used to enchant dirt to be placed over the bones of a deceased person resulting in rebirth in heaven. The Buddha instructed Śakra to give the dhāraṇī to Supratiṣṭha and report back in seven days. The god wore it on his clothes for six days and nights and preserved it in his mind as the Buddha had instructed. The god’s bad fate was overcome, his lifespan increased, and eventually he received a prophesy of his future attainment of buddhahood (Odae chinŏn 1635, pp. 105a–106b; Kim 2010, p. 148).

These descriptive prescriptions on the use of these dhāraṇīs serve the purpose of explaining to the reader how to employ dhāraṇīs as well as the specific miraculous benefits of dhāraṇī-practice. Although perhaps serving a similar function, they are not like Japanese shidai 次第 ritual books because they are not specific “how-to” manuals with set procedures. More precise how-to processes may have existed in oral transmission, and certainly exist in contemporary dhāraṇī- and mantra-practice in South Korea in the twenty-first century (McBride 2019b); but they seem to be missing from extant woodblock prints and manuscripts from the Chosŏn period (McBride 2020b). The narratives in the sections dealing with each dhāraṇī do recommend certain practices, but they do not explicitly advocate a set procedure. There is enough vagueness for individuals to utilize the dhāraṇīs in personal ways.

Kim Sua reports that the Kyujanggak possesses a woodblock edition of the Yŏnghŏm yakch’o in literary Sinitic published at Inhŭng Monastery 仁興寺 in 1239 (Inhŭngsabon Yŏnghŏm yakch’o 仁興寺本 靈驗略抄); and she asserts that the Vernacular Translation of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance (Yŏnghŏm yakch’o ŏnhae), which was published by Queen Insu and the Chosŏn court in 1485, was based on this earlier, Koryŏ-period edition (Kim 2016a, p. 100). I have not yet been able to independently verify the existence of this Koryŏ-period edition of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance. However, as we have seen above, considering that at least one sheet of a bilingual edition of the Five Great Mantras appears to have been in circulation in 1346, when it was enshrined in the gilt-bronze image of Amitābha at Munsu Monastery, it is likely that Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance was also a popular text that circulated widely in Korea since the mid-to-late Koryŏ period.

Woodblock editions of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance, both the literary Sinitic edition and the translation in the Korean script, circulated in Korea outside of the context of the Five Great Mantras. The catalog of the Seoul National University Library reports that the Kyujanggak possesses three woodblock editions of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance: an undated edition (古 1730 41) and two 1550 editions (古 1730 22A and 294.3 Y43). The second 1550 edition (294.3 Y43) is a Korean vernacular translation of the text and is available for online viewing through a link in the online catalog. The Dongguk University Library possesses a 1550 woodblock edition in Sinitic (213.19).

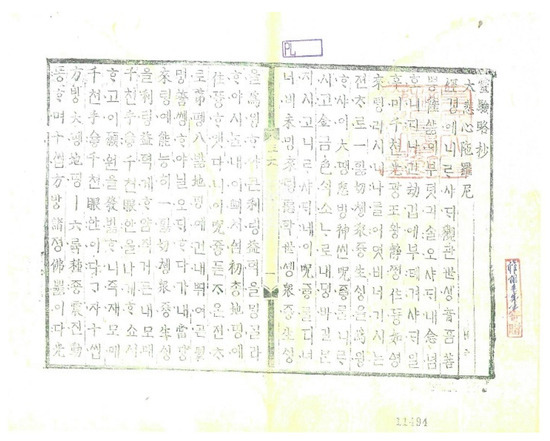

Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance was usually placed at the end of the Five Great Mantras, although at least one edition of the Five Great Mantras is comprised solely of a vernacular version of the Efficacious Resonance text (Odae chinŏn 1550, 2a1–19b) (see Figure 3). This may be a special case because all other editions of the Five Great Mantras I have analyzed have at least one of the transliterated dhāraṇīs. After the vernacular version of the text, this edition concludes with the postscript (hugi 後記) and colophon by the monk Hakcho, just as in the 1485B and 1635 editions of the Five Great Mantras.

Figure 3.

Vernacular Translation of Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Resonance (Yŏnghŏm yakch’o ŏnhae) (Odae chinŏn 1550, p. 2).

10. Concluding Reflections

The most important result or consequence of this analysis of the Five Great Mantras is that it problematizes the traditional or conventional way the field of East Asian Buddhist studies has sought to describe the history of the tradition. Hitherto, the histories of Buddhism in East Asian countries have been conceptualized or imagined based on a quasi-orthodox, canonical tradition based on the study of sūtras and commentaries. Scholarly obsession with, or perhaps allegiance to, texts contained in the Taishō Edition of the Buddhist Canon (as well as similar canons and collections published in modern times), has unduly influenced the way scholars interpret the importance of particular editions of texts and understand the historical or evolutionary development of the religion. The popularity and publishing history of the Five Great Mantras directly questions scholarly loyalty or adherence to the relevance of claims of canonicity because none of the editions of the dhāraṇīs and the sūtra-like descriptions for use of the dhāraṇīs as found in Brief Transcriptions of Efficacious Response is “canonical.” Thus, the uncomfortable truth, or, rather, the significance of this point is that so-called “non-canonical,” independently published materials were just as important—if not more important—to the living Buddhist communities in Korea during the Koryŏ and Chosŏn periods, and likely other parts of East Asia. This makes the circumstances regarding the production of manuscripts and the printed publications in East Asian Buddhism comparable to that of Christianity in medieval and early modern Europe, where variant texts played an important role in the development of regional characteristics.