The Chinshō Yasha-hō 鎮將夜叉法 and the Adaptation of Tendai Esoteric Ritual

Abstract

:1. Introduction

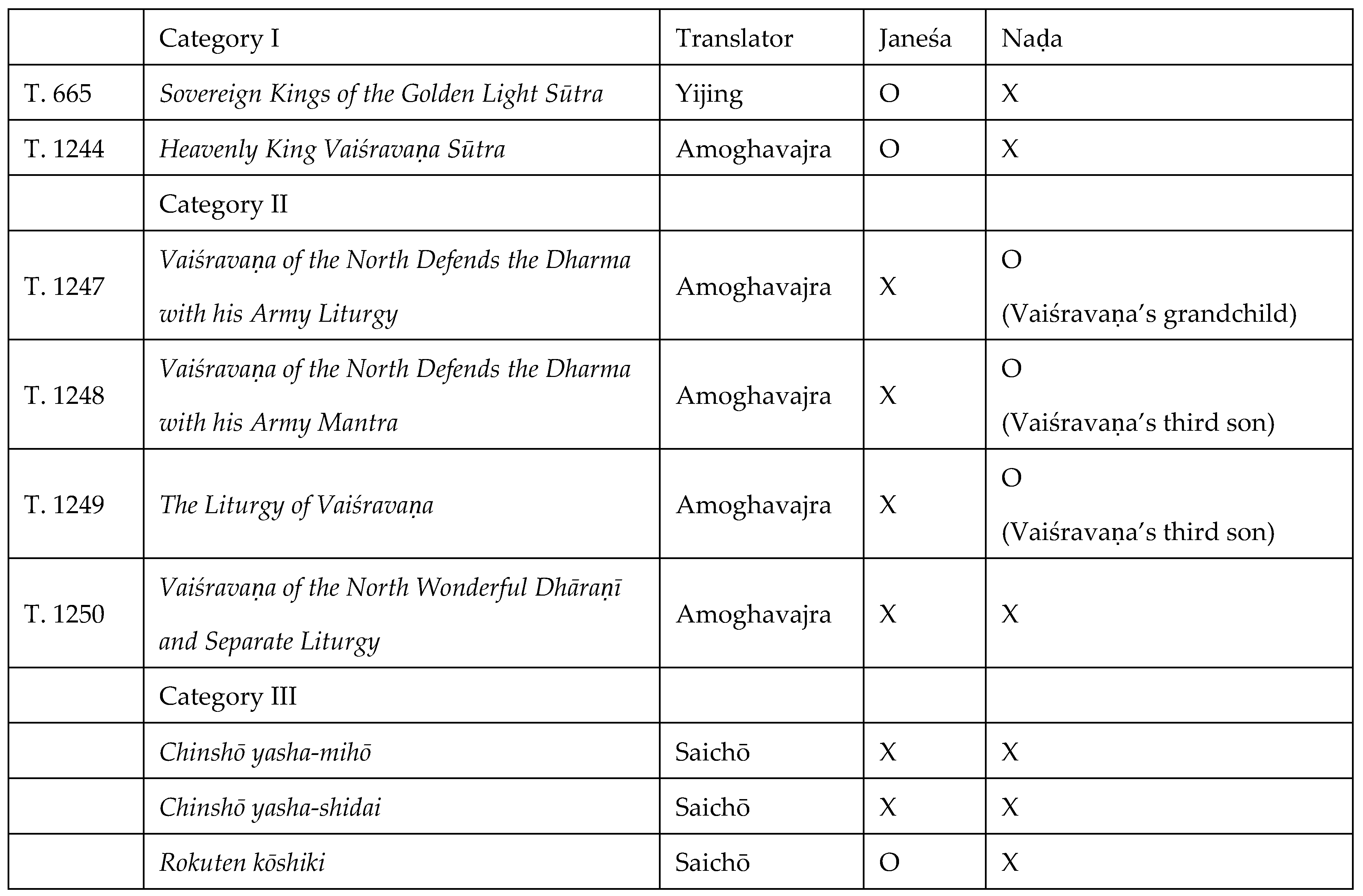

2. The Japanese Catalogues and the Texts of the Vaiśravaṇa Rituals

- Saichō (767–822): Duomentian fa 多門天法, Qingmian beifang tuoluoni fa 青面北方陀羅尼經法.

- Kūkai (774–835): Pishamen tianwang jing 毘沙門天王經 (T. 1244), Mohefeishiluo monayeti poheluoshe tuoluoni yigui 摩訶吠室羅末那野提婆喝羅闍陀羅尼儀軌 (T. 1246).

- Jōgyō 常曉 (d.867): Beifang Pishamen tianwang niansong yaojing 北方毘沙門天王念誦要經.

- Engyō 円行 (799–852): Beifang Pishamentian suijun hufa zhenyan 北方毘沙門天隨軍護法真言 (T. 1248).

- Ennin 円仁 (794–864): Pishamen tianwang jing 毘沙門天王經 (T. 1244), Beifang Pishamen tianwang zhenyanfa 北方毘沙門天王真言法.

- Eiyun 惠運 (798–869): Beifang Pishamen tianwang ganlu taizi jing 北方毘沙門天王甘露太子經, Foshuo beifang Pishamen tianwang ganlu taizi nazha jufaluo mimi zangwang ruyi jiushe zhongsheng genben tuoluoni 佛說北方毘舍門天王甘露太子那吒俱伐羅秘密藏王如意救攝眾生根本陀羅尼.

- Enchin 円珍 (814–891): Pishamen tianwang jing 毘沙門天王經 (T. 1244).

- Shūei 宗叡 (809–884): Pishamen tianwang jing 毘沙門天王經 (T. 1244), Pishamen yigui 毘沙門儀軌 (T. 1249), Beifang Pishamen duowen baozang tianwang shenmiao tuoluoni biexing yigui 北方毘沙門多聞寶藏天王神妙陀羅尼別行儀軌 (T. 1250), Pishamen baozang tianwang shenmiao zhangju tuoluoni 毘沙門寶藏天王神妙章句陀羅尼, Nilanpo zhenzi 尼藍婆禎子, Pishamen zhenzi毘沙門禎子, Pishamen zangwang tuoluonifa 毘沙門藏王陀羅尼法, Nazha jubuo tuoluoni jing 那吒俱鉢陀羅尼經.

- Category I:

- Spirit Spells Spoken by the Seven Buddhas and Eight Bodhisattvas (Qifo bapusa suoshuo datuoluoni Shenzhou jing 七佛八菩薩所說大陀羅尼神呪經, T. 1332), anonymous translator in Eastern Jin.7

- Dhāraṇī Collection Scripture (Tuoluoniji jing陀羅尼集經, T. 901), translated by Atikūta (Ch. Adiquduo 阿地瞿多, fl.652).

- The Rituals of the Vaiśravaṇa Mantra, (Ch. Hongjiatuoye yigui/Jp.Ungadaya-giki吽迦陀野儀軌, T. 1251), translated by Vajrabodhi (Ch. Jin’gangzhi金剛智, 671–741).8

- Sovereign Kings of the Golden Light Sūtra (Jinguangming zuishengwang jing 金光明最勝王經, T. 665), translated by Yijing 義淨 (635–713).

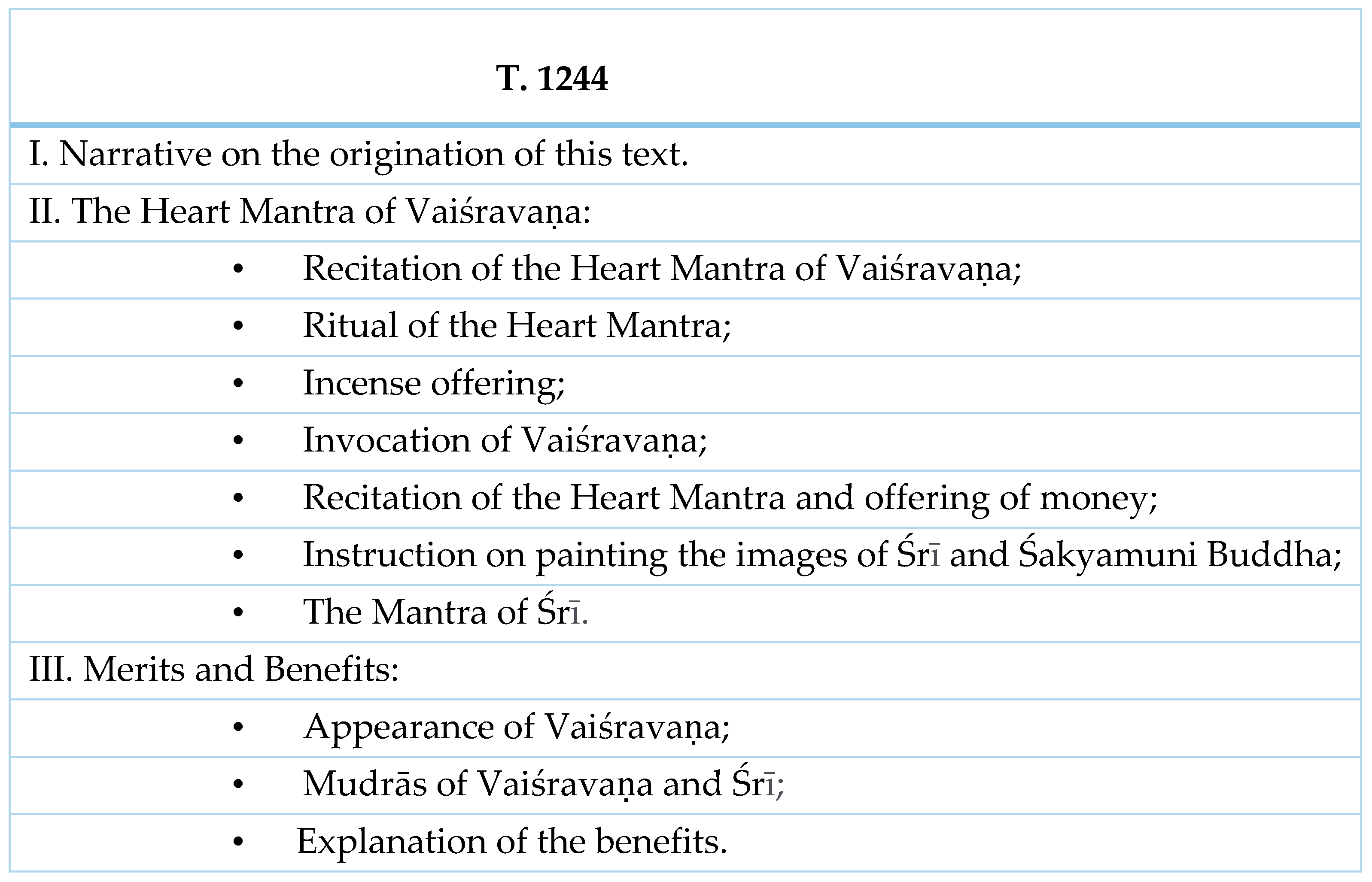

- Heavenly King Vaiśravaṇa Sūtra (Pishamen tianwang jing 毘沙門天王經, T. 1244), translated by Amoghavajra (Ch. Bukong不空, 705–774).9

- Category II:

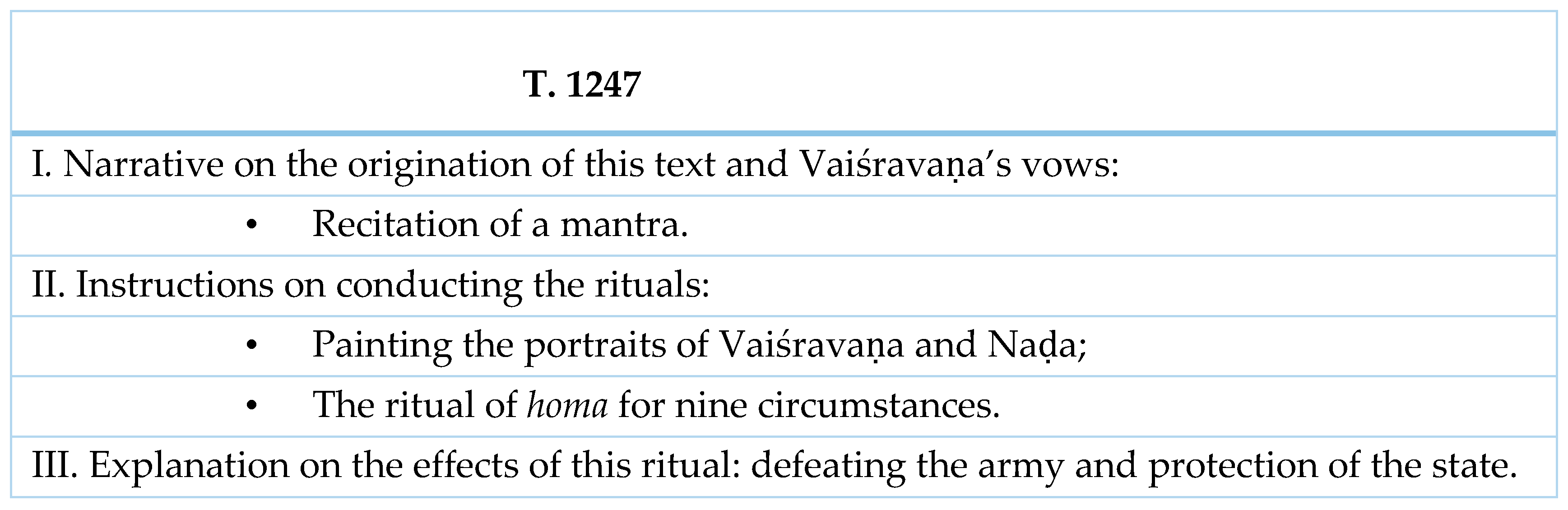

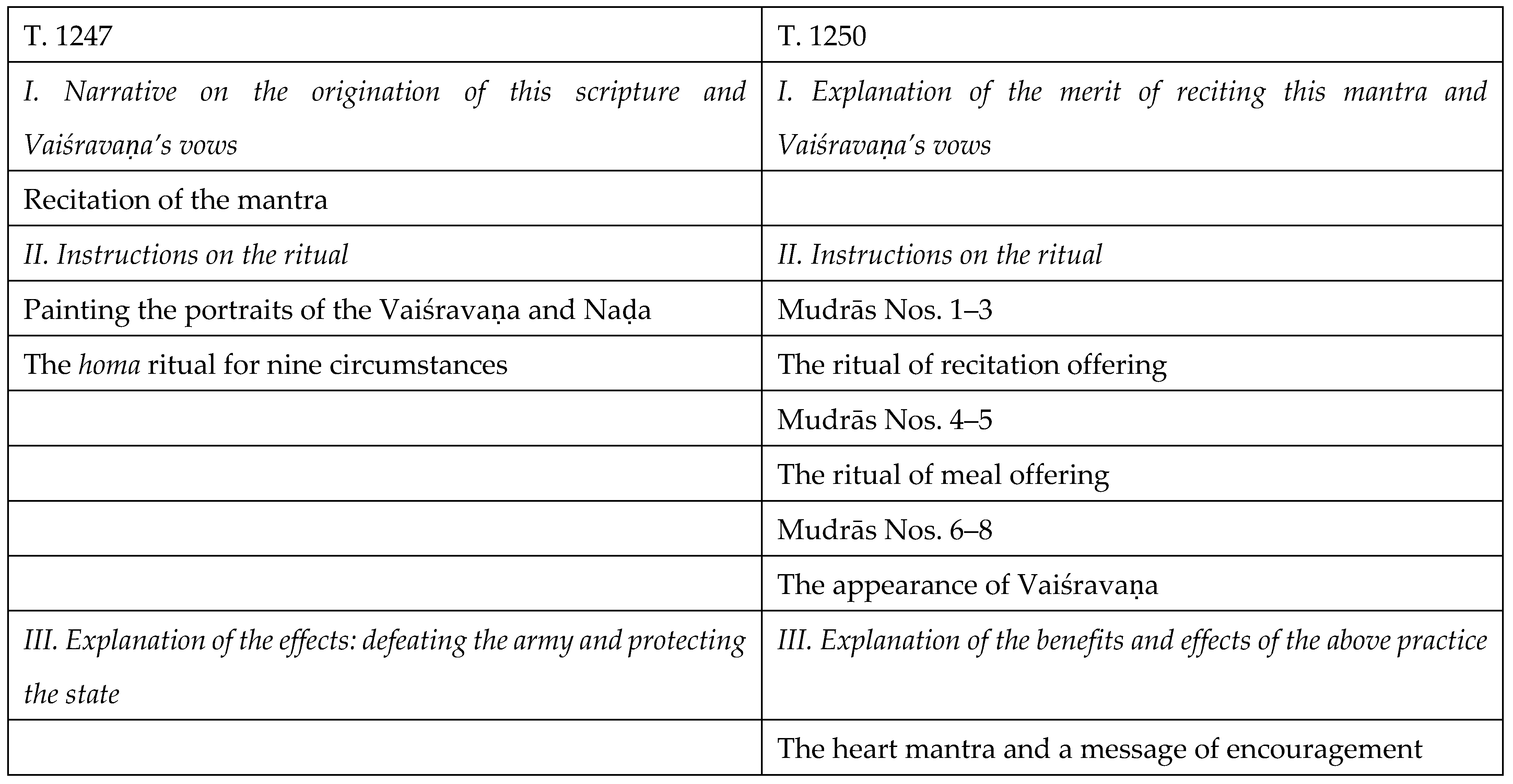

- Vaiśravaṇa of the North Defends the Dharma with his Army Liturgy (Beifang pishamen suijun hufa yigui 北方毘沙門隨軍護法儀軌, T. 1247), translated by Amoghavajra.10

- Vaiśravaṇa of the North Defends the Dharma with his Army Mantra (Beifang pishamen suijun hufa zhenyan 北方毘沙門隨軍護法真言, T. 1248), translated by Amoghavajra.11

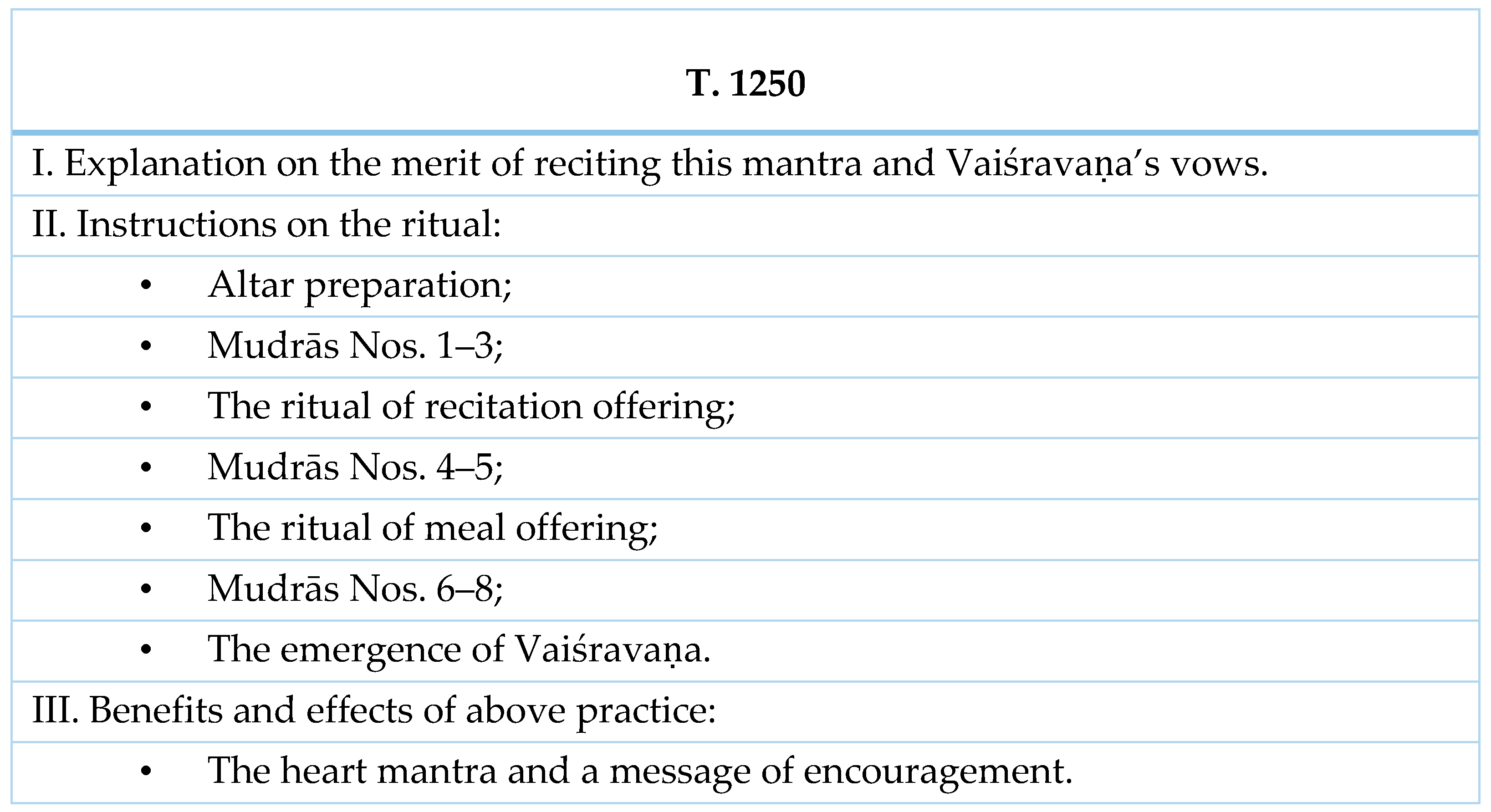

- Vaiśravaṇa of the North Wonderful Dhāraṇī and Separate Liturgy (Beifang pishamen duowen baozang tianwang shenmiao tuoluoni biexing yigui 北方毘沙門多聞寶藏天王神妙陀羅尼別行儀軌, T. 1250), translated by Amoghavajra.13

- Category III:

- The Chinshō yasha-shidai 鎮將夜叉次第.

- The Chinshō yasha-mihō 鎮將夜叉秘法 and the Chinshō yasha-nenjuhō 鎮將夜叉秘密念誦法 (Mostly identical).

3. Liturgy and Narratives in the Texts

3.1. Category I

I practiced the bodhi [path] and became a demon king for the benefits of all sentient beings.

Sentient beings long resided in ignorance, and I opened their eyes with my golden blade.

Once their eyes of wisdom are opened, they transcend life and death; since they have transcended life and death, they will ascend to nirvana.14

This dhāraṇī can defeat all kinds of disasters, including natural disasters caused by disrupted sun and moon, unseasonable wind and rain, or famine. It can also chase away intruders to the country, subjugate rebellious ministers, and so on.15

3.2. Category II

3.2.1. T. 1247

3.2.2. T. 1248

3.2.3. T. 1249

3.2.4. T. 1250

3.2.5. Comparing Texts of Category II

4. The Chinshō Yasha-Shidai

5. Naḍa in the Ritual Texts

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Chapter 6 in T. 663; Chapter 12 in T. 665. |

| 2 | See Asabashō 阿娑縛抄, TZ 9:429, Figure 71. |

| 3 | Ashizu Jitsuzen蘆津實全 (1850–1921)’s Kōchō tendai shiryaku, p. 6. |

| 4 | Mochizuki bukkyō daijiden, vol. 4, p. 3631. |

| 5 | See Faure’s (2016, pp. 29–31) explanation of the similarity in iconographic features, but they are clearly different figures in images. |

| 6 | According to Annen’s catalogue, most of the eight scriptures concerning Ātavaka in the list above were brought back to Japan by Ennin and Jōgyō, except the first one by Kūkai. |

| 7 | This scripture has four fascicles. According to the Tang catalogue of Kaiyuan shijiao lu 開元釋教錄, the translator was anonymous and was not recorded in catalogues until the Tang dynasty (T. vol. 55, no. 2154: 510b13). Part of its mantras and verses were collected in the first three fascicles of the Tuoluoni zaji 陀羅尼雜集 (T. vol. 21, no.1336: 536b-556c). |

| 8 | The Japanese pronunciation of Ungadaya-giki can also be spelled “Unkyadaya-giki” as in the Bussho kaisetsu daijiden, vol. 1, p. 228. This text was possibly forged in Japan. See Misaki (1980, pp. 1383–404), especially p. 1394. |

| 9 | This scripture was likely to be forged in China during the Tang dynasty. See Ishii’s serial studies (Ishii 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019b). |

| 10 | This scripture was possibly forged in China during the Tang dynasty. See Matsumoto (1939, p. 10). |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | This scripture was likely to be forged in the Tang. See Matsumoto (1939, p. 10). |

| 14 | 我於往昔修菩提, 為眾生故作鬼王。眾生久處無明闇, 我以金錍開其眼。慧眼既開度生死, 生死既度昇泥洹. T. vol. 21, no.1332: 556a23-26. |

| 15 | 此陀羅尼力悉能摧伏,移山斷流乾竭大海,摧碎諸山猶如微塵。若日月失度能使正行,悉能穰災,風雨失時能使時節,穀米不登能使豐熟,隣國侵境悉能穰却,大臣謀反惡心即滅. This is abbreviated translation of the original passage, T. vol. 21, no. 1332: 536b23-c2. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | T. vol. 21, no. 1249: 228c5-6. |

| 19 | T. vol. 21, no. 1250: 230c3-231c23. |

| 20 | For this Northern Chan text and its relationship with the Tiantai school, see Lin (2017, pp. 156–94). |

| 21 | The alleged translator of this text was Śubhākarasiṃha (pp. 637–35), but it was probably composed in China, whether by Śubhākarasiṃha or not. See Bussho kaisetsu daijiden, vol. 1, pp. 16–17. |

| 22 | Bussho kaisetsu daijiden, vol. 4, pp. 278–79. |

| 23 | The Chinese characters for Janeśa could be Channishi禪膩師 (Jp. Zennishi), Channizi禪尼子, or Shenisuo 赦儞娑. |

| 24 | DZ, vol. 3, pp. 4–7. |

References

Primary Sources

Asabashō 阿娑縛抄, Shōchō 承最 (1205–1282). TZ 8–9, 3190; also DNBZ 57–60.Azhaboju yuanshuaidajiang shangfo tuoluonijing xiuxing yigui 阿吒薄俱元帥大將上佛陀羅尼經修行儀軌, Śubhākarasiṃha (637–735), trans., T. vol. 21, no.1239.Beifang Pishamen duowen baozang tianwang shenmiao tuoluoni biexing yigui 北方毘沙門多聞寶藏天王神妙陀羅尼別行儀軌 [Vaiśravaṇa of the North Wonderful Dhāraṇī and Separate Liturgy], Amoghavajra, trans., T. vol. 20, no.1250.Beifang Pishamen suijun hufa zhenyan 北方毘沙門隨軍護法真言 [Vaiśravaṇa of the North Defends the Dharma with his Army Mantra], Amoghavajra, trans., T. vol. 20, no. 1248.Beifang Pishamen tianwang suijun hufa yigui 北方毘沙門天王隨軍護法儀軌 [Vaiśravaṇa of the North Defends the Dharma with his Army Liturgy], Amoghavajra (704–774), trans., T. vol. 21, no. 1247.Bishamonten-kōshiki 毘沙門天講式, Saichō, DZ vol. 3: 4–7.Bussho kaisetsu daijiden 仏書解説大辞典, Ono Genmyō 小野玄妙 (1883–1939), ed. Tokyo: Daitō shuppansha 大東出版社.Chinshō yasha-mihō 鎮將夜叉秘法, Saichō, DZ vol. 3: 207–12.Chinshō yasha-nenjuhō 鎮將夜叉秘密念誦法, Saichō, DZ vol. 3: 201–5.Chinshō yasha-shidai 鎮將夜叉次第, Saichō, DZ vol. 3: 184–99.Dai Nihon Bukkyō zensho 大日本佛教全書. Tokyo: Bussho Kankōka 佛書刋行會, 1912–1937. [DNBZ]Daizong chao zeng sikong dabianzheng guangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhiji代宗朝贈司空大辨正廣智三藏和上表制集, Amoghavajra. T. vol. 52, no. 2120.Dengyō dashi zenshū 傳教大師全集, Saichō 最澄 (767–822). Eizan gakuin 叡山學院, ed. Shiga: Hieizan Tosho Kankōsho 比叡山圖書刊行所, 1926–1927. [DZ]Ganlu Juntuli pusa gongyangniansong chengjiuyigui 甘露軍荼利菩薩供養念誦成就儀軌, Amoghavajra, trans., T. vol. 21, no. 1211.Jinguangming zuishengwang jing 金光明最勝王經 [Sovereign Kings of the Golden Light Sūtra], Yijing 義淨 (635–713), trans. T. vol. 16, no. 665.Jizōdaidōshin kusakuhō 峚窖大道心驅策法.T. vol. 20, no.1159A.Kōchō tendai shiryaku 皇朝天台史略 [On the Tendai sect in Japan], Ashizu, Jitsuzen 蘆津實全 (1850–1921). Enryakuji bunshoka. Kyoto: kaiba shoin 貝葉經書院, 1896.Mochizuki Bukkyō daijiten望月佛教大辞典 [Mochizuki Buddhist Dictionary]. Mochizuki Shinkō 望月信亨 (1869–1948), ed. 10 volumes. Tokyo: Sekai Seiten Kankō Kyōkai 世界聖典刋行協會. 1954–1958. ()(Originally published 1932–1936).Pishamen tianwang jing 毘沙門天王經 [Heavenly King Vaiśravaṇa Sūtra], Amoghavajra, trans., T. vol. 21, no. 1244.Pishamen yigui 毘沙門儀軌 [The Liturgy of Vaiśravaṇa], Amoghavajra, trans., T. vol. 20, no. T. 1249.Qifo bapusa suoshuo datuoluoni Shenzhou jing 七佛八菩薩所說大陀羅尼神呪經 [Spirit Spells Spoken by the Seven Buddhas and Eight Bodhisattvas], anonymous translator, T. vol. 21, no. 1332.Shoajari Shingon mikkyō burui sōroku諸阿闍梨眞言密教部類總録 [A Catalogue of the Shingon Esoteric Buddhist Canons brought into Japan by Acaryas], Annen 安然 (841–901), T. T. vol. 55, no. 2176.Taishō shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經, Takakusu Junjiro 高楠順次郎, ed. Tokyo: Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai, 1988. [T]Taishō shinshū Daizōkyō zuzō 大正新脩大藏經續藏, Takakusu Junjiro 高楠順次郎, ed. Tokyo: Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō Kankōkai, 1988. [TZ]Tuoluoniji jing陀羅尼集經 [Dhāraṇī Collection Scripture], translated by Atikūta (Ch. Adiquduo 阿地瞿多, fl.652), T. vol. 18, no. 901.Ungadaya-giki吽迦陀野儀軌] (Ch. Hongjiatuoye yigui), Vajrabodhi (Ch. Jin’gangzhi金剛智671–741), trans., T. vol. 21, no. 1251.Zhenyuan xinding shijiao mulu 貞元新訂釋教目錄 [Catalogue of the Zhenyuan Era]. Yuanzhao 圓照 (727–809). T. vol. 55, no. 2154.Secondary Sources

- Faure, Bernard. 2016. Gods of Medieval Japan. Protectors and Predators. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goble, Geoffrey. 2013. The Legendary Siege of Anxi: Myth, History, and Truth in Chinese Buddhism. Pacific World 15: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, Akihiko 橋本章彥. 2008. Bishamonten: Nihon-Teki Tenkai No Shosō 毘沙門天: 日本的展開の諸相. Tōkyō: Iwata Shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Masatoshi 石井正稔. 2014. Tamonten giki ni tsuite—Hoppō shingon to no kankeisei—『多聞天儀軌』について―『北方真言』との関係性―. Bukkyō Bunka Gakkai Kiyō 佛敎文化學会紀要 23: 97–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Masatoshi 石井正稔. 2015. Kōbō daishi Kūkai shōrai no Bishamonten kyōkirui ni tsuite—jidai haikei miru Fukū yaku no Bishamontennōkyō no seiritsu nendai 弘法大師空海請來の毘沙門天經軌類について—時代背景より見る不空訳の『毘沙門天王經』の成立年代—. Buzan Kyōgaku Daigai Kiyō 豊山敎學大会紀要 43: 153–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Masatoshi 石井正稔. 2016. Fukū yaku Bishamontennōkyō ni tsuite 不空訳『毘沙門天王經』について. Bukkyō Bunka Gakkai Kiyō 佛敎文化學会紀要 25: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Masatoshi 石井正稔. 2017. Bishamontennōkyō oyobi ni Konkōmyōsaishōōkyō no kōzō to naiyō ni tsuite (1)『毘沙門天王経』並びに『金光明最勝王経』の構造と内容について(1). Buzan Kyōgaku Daigai Kiyō 豊山教学大会紀要 45: 169–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Masatoshi 石井正稔. 2019a. Bishamontennōkyō narabi ni Konkōmyōsaishōtennōkyō no kōzō to naiyō ni tsuite (2) 『毘沙門天王経』並びに『金光明最勝王経』の構造と内容について(2). Bukkyō Bunka Gakkai Kiyō 佛教文化学会紀要 28: 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Masatoshi 石井正稔. 2019b. Fukū yaku Bishamon giki ni tsuite 不空訳『毘沙門儀軌』について. Indogaku Bukkyōgaku Kenkyū 印度學佛敎學硏究 68: 190–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyanaga, Nobumi 彌永信美. 2002. Daikokuten Hensō: Bukkyō Shinwagaku 1 大黒天变相: 仏敎神話学 I. Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyota, Jakun 清田寂雲. 1976. Chinshō yasha-hō no shingon no yakukai ni tsuite 鎮將夜叉法の真言の譯解について. Tendai Gakuhō 天台学報 18: 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Komoro, Junko 小師順子. 2003. Chūgoku ni okeru Bishamonten reikentan no seiritsu 中国における毘沙門天霊験譚の成立. Komazawa Daigaku Bukkyōgakubu Ronshū 駒澤大学仏教学部論集 34: 263–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Pei-ying. 2017. A Comparative Approach to Śubhākarasiṃha’s (637–735) Essentials of Meditation: Meditation and Precepts in Eighth Century China. In Chinese and Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism. Edited by Yael Bentor and Meir Shahar. Leiden: Brill, pp. 156–94. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, Bunzaburō 松本文三郎. 1939. Tobatsu Bishamon kō 兜跋毘沙門攷. Tōhō gakuhō 東方学報 10: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Misaki, Ryōshū 三崎良周. 1968. Annen no Shoajari shingon mikkyō burui sōroku ni tsuite 安然の諸阿闍梨眞言密教部類惣録について [On “A Catalogue of the Shingon Esoteric Buddhist Canons brought into Japan by Several Masters” by Annen]. Indogaku Bukkyōgaku Kenkyū 印度学仏教学研究 16: 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Misaki, Ryōshū 三崎良周. 1980. Chinshō yasha-hō ni tsuite 鎮将夜叉法について. Dengyō Dashi Kenkyū 伝教⼤師研究 18: 1383–404. [Google Scholar]

- Rambelli, Fabio. 2002. The Emperor’s New Robes: Processes of Resignification in Shingon Imperial Rituals. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 13: 427–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, P.-y. The Chinshō Yasha-hō 鎮將夜叉法 and the Adaptation of Tendai Esoteric Ritual. Religions 2023, 14, 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081060

Lin P-y. The Chinshō Yasha-hō 鎮將夜叉法 and the Adaptation of Tendai Esoteric Ritual. Religions. 2023; 14(8):1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081060

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Pei-ying. 2023. "The Chinshō Yasha-hō 鎮將夜叉法 and the Adaptation of Tendai Esoteric Ritual" Religions 14, no. 8: 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081060

APA StyleLin, P.-y. (2023). The Chinshō Yasha-hō 鎮將夜叉法 and the Adaptation of Tendai Esoteric Ritual. Religions, 14(8), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081060