Abstract

Religiosity and spirituality can be both beneficial and harmful to happiness. It depends on its operationalization and the measures of religiosity and sociodemographics used, together with cultural and psychosocial factors, still not comprehensively explored. This topic is especially important for religious-affiliated chronic patients such as those diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Religion can deliver a sense of meaning, direction, and purpose in life and be an additional source of support to cope with the stress and limitations connected with the disease. The aim of the present study was to verify whether religiosity, directly and indirectly, through finding meaning in life, is related to one’s level of happiness and whether gender, the drinking of alcohol, financial status, and age are moderators in this relationship. In sum, 600 patients from Poland who suffered from multiple sclerosis were included in the study. Firstly, some gender differences were noticed. In women, religiosity was both directly and indirectly, through finding significance, positively related to happiness. Secondly, it was found that in women, the direct effect of age on happiness was generally negative but was positively affected by religiosity; however, among men, age was not correlated with happiness. In the group of women, religiosity and a lower propensity to drink alcohol in an interactive way explained happiness. Thirdly, both in men and women, financial status positively correlated with happiness, but in the group of wealthy men only, religiosity was negatively related to happiness. In conclusion, religion was found to show a positive correlation with the happiness of Roman Catholic multiple sclerosis patients from Poland. In this group of patients, religious involvement can be suggested and implemented as a factor positively related to happiness, with the one exception regarding wealthy men.

1. Introduction

The relationship between religiosity and happiness and subjective well-being is an area of extensive research. The impression could be that this topic has been comprehensively explored and is well-recognized, but the amount of research does not go hand in hand with its quality or unambiguous results (Sloan et al. 2000; Sloan and Bagiella 2002; Hackney and Sanders 2003; Garssen et al. 2021). One of the main reasons for such discrepancies is the multifaceted and multidimensional character of these concepts, different operationalizations, and the plethora of measures used to examine them (Poloma and Pendleton 1990; Ellison 1991). For example, the meta-analysis of Hackney and Sanders (2003) regarding 28 empirical studies from 1990 to 2000 about the link between religiosity and life satisfaction has shown a mean effect size of 0.10 [CI: 0.08 to 0.11] for institutionalized religion indicators, of 0.12 [CI: 0.10 to 0.14] for ideological religion aspects, and of 0.14 [CI: 0.13 to 0.16] regarding personal devotion manifestations. In addition, a meta-analysis conducted on 48 longitudinal studies has indicated that the category of public religious activities is the only one positively related to mental health measured by indicators of distress, life satisfaction, well-being, and quality of life. The rest of the explored forms of religiosity such as private religious activities, religious support, the importance of religion, intrinsic religiosity, positive religious coping, and meaningfulness, and composite measures including public and/or private religious activities in combination with intrinsic religiosity, were not correlated with mental health (Garssen et al. 2021).

In the literature, the two main functions of religiosity in the context of well-being are especially examined: social support and finding purpose and meaning in life (Lim and Putnam 2010; Diener et al. 2011; Prinzing et al. 2021; Krok 2015). Many studies have shown that social support (Nooney and Woodrum 2002; Prado et al. 2004; Holt et al. 2005; Diener et al. 2011) and meaning in life (Park 2006; Diener et al. 2011; Wnuk and Marcinkowski 2014; Krok 2015) underlie the relationship between religiosity and happiness and well-being regardless of the operationalizations considered and the measurement of both variables. In addition, the positive role of religion in emotional regulation and the implementation of a healthy lifestyle has been stressed (Morton et al. 2017). Some studies have confirmed that leading a healthy lifestyle, including healthy habits such as the avoidance of excessive alcohol use, a good diet, healthy eating, and physical exercise can positively influence well-being because of religiosity (Morton et al. 2017; VonDras et al. 2007). Religion plays a buffering role against excessive drinking, which can be interpreted in the category of the social control of religious groups and behavior modeling from the members of these groups.

Meaning-making and social religious functioning are connected with religious orientation. Based on the religious orientation theory of Allport and Ross (1967), one can be involved in religion as a central and autotelic value in an axiological system, being intrinsically religiously motivated. On the other hand, religion is treated as an instrumental value leading to the realization of different social values such as social support (extrinsic social religious orientation) or the endeavor to achieve important personal goals (extrinsic personal religious orientation) (Maltby 2002).

Intrinsic religious motivation is an antecedent of a meaning-oriented system facilitating leading a purposeful and meaningful life as a happiness manifestation. In this approach, religion is beneficial through appraisal and successfully dealing with stress, serving as a cognitive–behavioral framework (James and Wells 2003) to perceive, interpret, and integrate experiences within a religious meaning-oriented system (Park 2007, 2010). In contrast, using religion as a way to realize social functioning can be harmful to well-being. Recent studies have shown that the results in this topic are equivocal, emphasizing a moderating role of religious orientation in the relationship between religiosity and subjective well-being (Lavrič and Flere 2008; Steffen et al. 2015). For example, in a national sample, intrinsic religious orientation was positively related to a positive effect and negatively associated with a negative effect, and extrinsic religiosity was not connected to either of these (Steffen et al. 2015). Additionally, national culture influences the religious orientation–happiness connection. For example, in the US sample, intrinsic religiosity positively correlated with a positive effect and was not related to a negative effect. Another relationship pattern was noticed among Serbian and Slovakian citizens, where both intrinsic and extrinsic religious motivation correlated with both kinds of affectivity (Lavrič and Flere 2008). In Japanese individuals, neither intrinsic nor extrinsic religiosity were related to a positive and a negative effect.

In addition to religious orientation, other religious aspects can also perform a moderating role in the relationship between religiosity and happiness and well-being, such as religious coping (Terreri and Glenwick 2013; Park et al. 2018), attachment to God and the representation of God (Mendonca et al. 2007; Stulp et al. 2019); and the type of prayer (Lazar 2015). For example, in a sample of African Americans, positive religious coping was not related to a negative effect, negatively predicted depression, and positively explained the positive effect. Negative religious coping did not correlate with a positive effect and was a positive predictor of a negative effect and depression (Park et al. 2018). The meta-analysis of 123 samples consisting of almost 30,000 adolescent and adult participants has confirmed mostly medium effect sizes (r = 0.25 to r = 0.30) for the associations of positive representations of God with well-being and for the associations of two out of three negative representations of God with distress (Stulp et al. 2019).

The links between religiosity and well-being are more complicated and complex. In addition to some psychosocial mediators and religious moderators, other secular variables can interact with religiosity in explaining well-being and happiness, making it difficult to understand this phenomenon. These factors can be divided into two main categories such as sociodemographics and cultural variables. This first group encompasses gender (Lazar and Bjorck 2016), education level (Achour et al. 2017), financial status, age (Bartram 2021), etc. The second category includes attitudes toward religious socialization (Lun and Bond 2013), hostility toward authorities, uncertainty avoidance (Kogan et al. 2013), negative attitudes towards nonbelievers (Stavrova et al. 2013), social hostility toward a religious group (Lun and Bond 2013), and the Governmental regulation of religion, as measured by an index of political rights and civil liberties (Hayward and Elliott 2014).

It is difficult to take into account all the possible mediators, moderators, and control variables to achieve a possible full and comprehensive image of the relationship between religiosity and happiness. Bartram (2021) has focused on some problems and methodological shortcomings emphasizing that researchers investigating life satisfaction do not recognize the critical distinction between confounding variables and intervening variables, which are mixed with each other leading to substantial bias in the results.

The purpose of this study was to examine a model of associations between religiosity as a meaning system and as a way to struggle with illness by individuals suffering from multiple sclerosis, in relation to happiness, with a transparent and clear division between controlling and intervening variables.

2. Research Justification

Religion is a significant and effective way of struggling with chronic illness (Gordon et al. 2002; Koenig 2013). For example, it is a significantly important way of coping for individuals diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (Hecht et al. 2002), and this factor facilitates finding meaning (Büssing et al. 2013; Pakenham 2008). There is a lack of research that explains how religiosity is related to the happiness of multiple sclerosis patients based on the functions that religion can fill in daily life and in their struggle with the disease, taking into account the wider social and cultural context. Recent studies in this population are limited and have led to inconsistent results. For example, in a study by Büssing et al. (2013), faith was not related to a negative effect and life satisfaction. The lack of these links could have been affected by the young age of participants or other cultural factors. Contrary to these results, Vizehfar and Jaberi (2017) have confirmed that internal religion was positively correlated to mental health.

This study aims to fill this gap and widen the knowledge on this topic by appropriately selecting confounding and intervening variables (Bartram 2021) and taking into consideration cultural aspects as essential factors that influence the religiosity–well-being relationship (Büssing et al. 2013).

In Poland, the meaning-making role of religiosity for well-being, happiness, and mental health was explored among students (Wnuk and Marcinkowski 2014), adults (Krok 2014, 2015), and alcohol-dependent individuals participating in Alcoholics Anonymous (Wnuk 2021). For example, in a sample of students, spiritual experiences were positively related to life satisfaction and a positive effect through leading a purposeful and meaningful life (Wnuk and Marcinkowski 2014).

This study was conducted within the theory of religiosity as a meaning-oriented system (Park 2007, 2010) and Pargament’s (1999) religious oriented system (ROS), which, thanks to a cognitive–emotional framework (James and Wells 2003) facilitates finding meaning, significance, and purpose through successful coping based on accommodation and assimilation. Additionally, the theory of happiness of Seligman and the findings of Frankl correspond with the idea that a meaningful life leads to happiness as one way to achieve it.

For the comprehensive picture of this research, some cultural and sociodemographics factors served as a significant structure. In accordance with Pöhls (2021), in the research sample, every participant was religiously affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, which means that there were no nonreligious individuals, and other religious affiliations have not influenced the results between religiosity and happiness. The sample was also homogeneous with reference to race because all the multiple sclerosis patients participating in the study were of the White race. In addition, other cultural factors were controlled such as the national level of religiosity in Poland (Okulicz-Kozaryn 2010) and the attitude toward religious socialization (Lun and Bond 2013).

Generally, religious people are happier in religious nations (Okulicz-Kozaryn 2010; Stavrova et al. 2013) and present permissive attitudes toward religious socialization (Lun and Bond 2013). They are less happy in nonreligious countries, or this relationship is not significant. Poles are a very religious nation (Pew Research Center 2018) with a positive attitude toward religious socialization (Lun and Bond 2013).

One of the sociodemographic variables which can moderate the link between religiosity and happiness is sex (gender) (Vosloo et al. 2009; Cokley et al. 2013; Lazar and Bjorck 2016; Esat et al. 2021). Previous research leads to inconclusive results in this topic, but some of them have indicated positive correlations between religiosity and well-being indicators among women and the lack of such an association in men. For example, among Black American women, religious engagement was related to lower anxiety and depression but higher anxiety for Black men (Cokley et al. 2013). These gender differences can be explained by the fact that women are more religious than men, especially among Christians (Schnabel 2015; Robinson et al. 2019) and can have a stronger tendency to search for meaning and significance through religion. An additional element that motivates Polish women to treat religion as a meaning-oriented system is social learning and cultural permission and enhancement to involve religiosity in dealing with chronic and progressive illnesses such as multiple sclerosis. Men in Poland diagnosed with multiple sclerosis can also experience benefits connected to religion but do not necessarily find meaning and significance as women do, especially since they live in a religious background. In other words, religion can fill other functions for them but still can be related to happiness. The above leads to assumptions regarding the relationship between religiosity and happiness among men and women, and stresses some gender differences.

Hypothesis 1.

In a sample of patients from Poland suffering from multiple sclerosis, regardless of gender, religiosity is positively directly related to happiness, but additionally, in the sample of women, religiosity is indirectly related to happiness through meaning. It means that sex moderates the relationship between religiosity and meaning among women, and these variables are significantly correlated but not in the group of men.

On a societal level, citizens of wealthy nations declare higher life satisfaction but lower meaning in life than residents of poor nations because of the greater religious commitment of the second group (Oishi and Diener 2014). In a study by Diener et al. (2011), difficult societal circumstances positively correlated with religiosity less than difficult individual circumstances. In addition, extensive multinational studies have revealed a greater harmful effect of lower socioeconomic status on subjective well-being in developed countries with a low level of national religiosity (Berkessel et al. 2021). It is interesting whether this tendency is reflected on an individual level in a very religious country such as Poland and whether being wealthy goes hand in hand with happiness and a lower level of religiosity.

Hypothesis 2.

In a sample of patients from Poland suffering from multiple sclerosis, the subjective evaluation of financial status is a moderator of the relationship between religiosity and happiness. It is expected that among more wealthy patients, religiosity is not related or negatively related to happiness, and inversely, in the group of less wealthy patients, religiosity is positively correlated with happiness in both men and women.

Generally, women are more religious than men, especially in Christian groups of believers (Schnabel 2015), regardless of age (Robinson et al. 2019), and they drink less alcohol in comparison to men (Wojtyniak et al. 2005). Additionally, gender moderates the relationship between religiosity and alcohol use (Kovacs et al. 2011; Pico et al. 2012). Recent findings have shown a negative correlation between some religiosity indicators (religious service attendance and praying) and alcohol use/misuse among girls but no relationships among boys (Kovacs et al. 2011; Pico et al. 2012). In addition, in a sample of community members from the St Louis area among average and more than average religious women, religiosity was negatively linked to simultaneous polysubstance use defined as the nonmedical use of opioids simultaneously with the use of cocaine, alcohol, ecstasy, or marijuana; however, in a group of men, this relationship was noticed only among the most religious (Acheampong et al. 2016). Regardless of religious affiliation, in Poland, men drink more alcohol than women and experience social and health-related problems because of that (Wojtyniak et al. 2005).

It was assumed that women, in comparison to men, more frequently look for purpose, meaning, and significance through religion, and their lower alcohol use to cope with illness interacting with their greater religiosity is positively related to happiness.

Inversely, in the case of men, less religiosity is not related to more extensive drinking, and these two related factors do not predict happiness.

Hypothesis 3.

In a group of women from Poland suffering from multiple sclerosis, alcohol drinking moderates the relationship between religiosity and happiness.

Age interferes in the relationship between religiosity and happiness. According to the general tendency across the world, the religiosity of countries is positively correlated with age (Pew Research Center 2018). On the other hand, age is a factor positively related to life satisfaction (Diener et al. 1999; Bartram 2021). Some studies have confirmed that the beneficial role of age for well-being regards only middle age (40–64 yrs), the aged (65 yrs and older), and very old (85 yrs and older) individuals, which means that age can be a moderator in the relationship between religiosity and well-being.

For example, in a study by Tsaousis et al. (2013), age moderated the relationship between all religious measures such as intrinsic religiosity, private religious activity, and religious attendance and psychological well-being. The positive function of all three measures of religious involvement for psychological well-being was noticed only in a group of elderly participants compared to adults where this association did not occur.

Hypothesis 4.

In a sample of patients from Poland suffering from multiple sclerosis, age moderates the relationship between religiosity and happiness, and this is independent of gender.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The research participants were 600 patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. They were treated in nine Polish centers specializing in multiple sclerosis treatment localized in Białystok, Końskie, Międzylesie, Rzeszów, Sandomierz, Szczecin, Warszawa—two centers, and Zabrze. The inclusion criteria of qualification in the study encompassed being aged from 17 to 70, having clinically definite MS according to the 2017 or 2010 McDonald criteria (Thompson et al. 2018), and providing informed consent to participate in the research. The following exclusion criteria were applied: a medical condition that prevents a person from participating in the research and comorbidity of neoplastic diseases. All participants were Roman Catholic Church representatives and agreed to take part in the study.

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Institute of Psychology at the University of Szczecin (KB 13/2021, 20 May 2021) and was performed in accordance with the criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Religious Meaning System

A religious meaning system questionnaire was developed by Krok (2009, 2011), and the function of this measure was to verify the meaning function of religiosity. It consisted of 20 statements to which participants responded on a 7-level Likert scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree) and encompassed two factors: religious orientation and religious meaning which were only weakly moderated (r = −0.18). It was proof that they were two different and weakly related constructs rather than two indicators of the same concept. In the rest of the text, religious orientation was used interchangeably with religiosity.

This tool has good psychometric properties such as internal consistency measured using the alpha Cronbach coefficient and criterion validity.

3.2.2. Happiness

The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire was used to assess happiness as a unidimensional construct (Hills and Argyle 2002). The unidimensional structure of this measure was confirmed in this study. The conducted factor analysis indicated one factor which explained 55.18% of variations of the happiness concept. This instrument included 29 items, and responses were rated on a five-point scale: “agree strongly” (5), “agree” (4), “not certain” (3), “disagree” (2), and “disagree strongly” (1). Higher scores indicated a greater level of happiness. In the research of Hills and Argyle, an alpha coefficient was 0.91.

3.2.3. Financial Status and Alcohol Consumption

Both financial status and alcohol consumption were verified using one question. Regarding financial status, participants were asked: “How is your financial situation”. Participants marked the following possibilities: tragic, very bad, bad, average, good, or very good. In reference to alcohol consumption, patients responded to the question “How frequently do you drink alcohol?” marking one of the responses: occasionally, often, or very often.

4. Statistical Analysis and Results

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS version 26.0 and AMOS version 26.0 (Arbuckle 2019). Due to the fact that only 43 research participants from 600 were abstinent, and 557 drank alcohol, alcohol abstinence as a variable was rejected from the model, leaving only the alcohol consumption variable. It meant that 43 participants, who were abstinent, did not respond to the question regarding alcohol consumption, and it was treated as a lack of data regarding this variable.

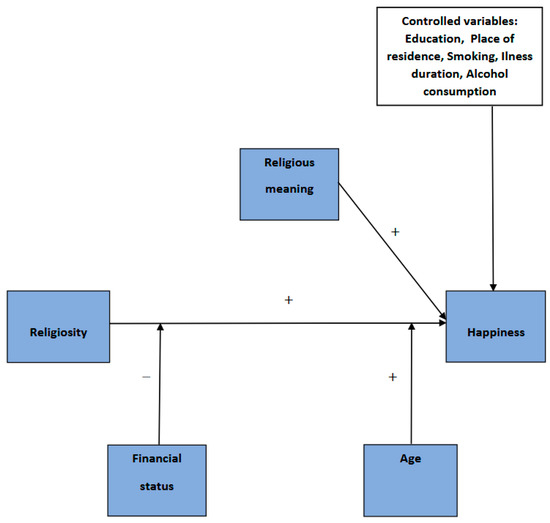

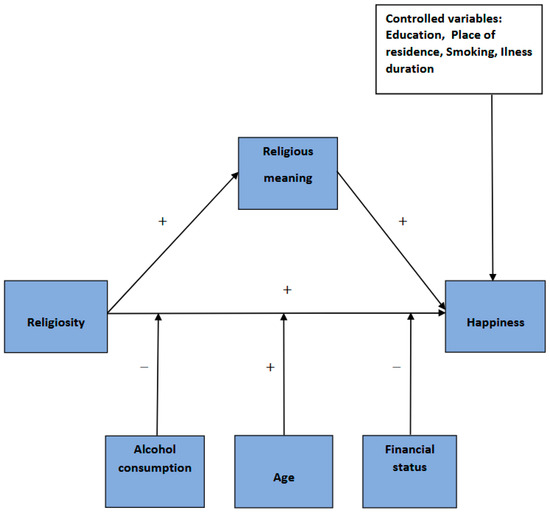

According to expectations due to the potential moderating role of gender, the model regarding men and women was different which is reflected in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model in men.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model in women.

The model was tested using structural equation modelling with the maximum likelihood method. It was dictated by the fact that following Mardia’s (1970) coefficient, the skewness of items was less than 2.0 and kurtosis less than 7.0 (Curran et al. 1996) which means that data distribution was close to a normal distribution.

To assess the goodness of the fit of the model, the following fit indices were chosen, such as the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), whose values should be under 0.90 and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with an acceptable value below 0.08 (Kline 2005). Additionally, for the comparison between men and women with reference to religiosity and alcohol drinking, the t-student test was applied.

Descriptive statistics of the sociodemographic variables are presented in Table 1. The independent variables and dependent variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics in sample of patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

The model fitted the data well: χ2(84) = 106.6; p = 0.57; CMIN/df = 1.25; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.021 (90% CI [0.000, 0.032]). Especially the RMSEA value and CMIN/df value less than 2 unequivocally proved the good model fit (Kline 2005).

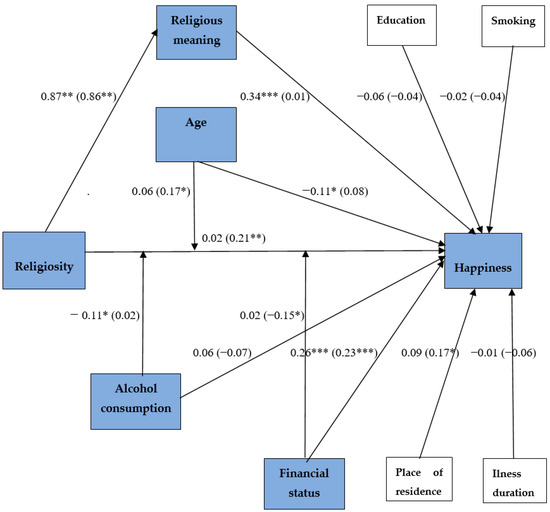

The results in men and women are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Research results in men and in women. Note. The standardized regression coefficients are presented. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. The residuals for variables were allowed to covary but are not shown for the sake of legibility.

There were no statistically significant differences between the model in the sample of men in comparison to women: df(13) CMIN = 8.84; p = 0.358. In addition, every path between independent variables and the dependent variable, the same as between the controlled variables and the dependent variable, was tested from the perspective of potential differences between gender. The results of these analyses are available in Table 3. A statistically significant difference was observed in the relationship between religious meaning and happiness due to gender, as well as between age and happiness. Finding religious meaning was positively correlated with happiness only in women, not in men; however, age was negatively related to happiness only in women.

Table 3.

Results of comparison in gender differences between independent, controlled, and the dependent variable of patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

As supposed, women were more religious than men (t = 2.58; p < 0.05), showed a greater religious meaning (t = 2.32; p < 0.05), and drank less alcohol (t = −2.23; p < 0.05), respectively: (M = 39.77; SD = 13.62 versus M = 36.50; SD = 14.61), (M = 39.72; SD = 10.36 versus M = 37.50; SD = 10.72), and (M = 0.94; SD = 0.15 versus M = 1.01; SD = 0.35).

5. Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between religiosity and happiness taking into account: one mediating variable, religion as searching for significance; four moderators such as gender, financial status, alcohol consumption, and age; and some controlled variables. Both religiosity and happiness concepts were positive and general to not complicate and obfuscate the comprehensive picture by using potentially moderating religiosity measures such as, for example, religious coping (Terreri and Glenwick 2013; Park et al. 2018), attachment to God and the representation of God (Mendonca et al. 2007; Stulp et al. 2019), or effective and cognitive indicators of subjective well-being (Diener et al. 1999).

The prepared model displayed a complex character and included both intervening and controlling variables.

The first hypothesis about the mediating role of meaning between religiosity and happiness in the group of women and only the direct effect between these variables among men was partially confirmed. Women from Poland diagnosed with multiple sclerosis use religious commitment to successfully find significance, purpose, and direction, which, in turn, is positively related to their happiness.

Contrary to women, in men, religiosity is a way to achieve happiness without reference to the meaning-making functions of religiosity such as social support, emotional regulation, or a healthy lifestyle. This means that among women, religious meaning totally mediates the relationship between religiosity and happiness; however, in men, religion serves as a religious meaning-making factor, and finding the purpose and meaning in religion is not related to the feeling of happiness. Conversely, among men, only religiosity without religious meaning is positively connected with happiness, but this is not the case in women. This study did not consider these religiosity roles in the endeavor to achieve happiness, but it was partially achieved by examining the potentially harmful effects of drinking alcohol. Consistent with recent research, our study indicates the mechanism underlying the relationship between religiosity and happiness and well-being and the benefits of finding meaning and purpose as a significant element of this mechanism (Park 2006; Diener et al. 2011; Wnuk and Marcinkowski 2014; Krok 2014, 2015) but only in women.

It is worth noticing that, in men, the link between religiosity and meaning was only a little above statistical significance, which can mean that many of the men are searching for meaning and purpose in life through religion, especially since this group was not as homogeneous in reference to religiosity as the women, which was reflected by the higher standard deviation. As was indicated in men, religiosity has not interacted with alcohol drinking in predicting happiness, which, in turn, does not exclude using other kinds of healthy habits motivated by religion and leading to feeling happy, which were not taken into account in this study.

The hypothesis about the moderating role of financial status in the relationship between religiosity and happiness was partially confirmed. The moderating effect took place only in the group of men. Among individuals with a higher level of financial (economic) status, religiosity was negatively linked with happiness. At the same time, for both women and men, religiosity and financial status controlled by sociodemographic variables were beneficial for their happiness. Similar to the elderly from East and Central European countries including Poland, financial status positively predicted happiness in both men and women (Bodogai et al. 2020). The prediction strength among men was almost the same value as in the above-cited study, but in the group of women, it was smaller; however, the identified gender difference was not statistically significant in the moderation test. These findings correspond with recent studies on the societal nonindividual level (Oishi and Diener 2014) showing that religiosity is a tool to deliver social norms and values for poor individuals to feel happy and is not necessary and is even harmful to wealthy ones. The noticed gender differences probably have their roots in cultural conditions and social and gender norms and roles assigned to women and men (Cislaghi and Heise 2020) enhanced by religion, as well as the significance religion plays in life and can be explained by classic sociological theories regarding gender role socialization and structural location (de Vaus and McAllister 1987). In this study, similar to other research, women were more religious than men (Schnabel 2015; Robinson et al. 2019), and the discrepancy of Poland between gender regarding the declared importance of religion was reflected in the ranging where Poland took second place among 36 countries (Pew Research Center 2018), which means that among Poles, religion is much more significant for women than for men in comparison to other countries.

For men who, often as breadwinners, focus on materialistic values more than women (Segal and Podoshen 2013). Financial status is especially significant for fulfillment and happiness, and achieving appropriate high financial wealth can lead to a decrease in religiosity as some ballast, unfavorable to happiness. As was confirmed in this study, among women, age was positively related to happiness, but in men, this link was not statistically significant.

It is probable, as shown by Watson et al. (2004), that men, in comparison to women, treat religion more instrumentally, and more frequently represent power–prestige attitudes about money due to a narcistic approach. Contrary to men, women are more intrinsically religious-oriented, and religious growth is an important goal in their life that delivers meaning, purpose, direction, and support.

These findings are consistent with the existential security framework postulated by Barber (2011), who claims that the need for religiosity declines with economic development, income security, and improved health. Recent results support this thesis on a societal level, but as has been shown, it also has an application on an individual level but only in regard to men.

The hypothesis that in women from Poland with multiple sclerosis, alcohol drinking is a moderator of the relationship between religiosity and happiness was positively verified. This effect, anticipated among women, was not observed in men. In the group of women, religiosity and alcohol consumption influence happiness in an interactive way. With stronger religiosity, women drink less alcohol and are happier because of that. In the group of men, religiosity was not related to alcohol consumption in predicting happiness. Consistent with recent research, gender moderated the link between religiosity and alcohol consumption (Kovacs et al. 2011; Pico et al. 2012), and the moderation effect of alcohol consumption between religiosity and happiness took place only in women. This could have been affected by two reasons. Similar to other studies, the women were more religious in comparison to the men (Schnabel 2015; Robinson et al. 2019), and in the women, religiosity was protective against the misuse of alcohol (Kovacs et al. 2011; Pico et al. 2012).

In conclusion, in the sample of multiple sclerosis patients, women were happier due to a stronger religiosity associated with less drinking, but among men, who generally are less religious than women, this effect was not noticed. Men drank more alcohol than women, as reflected in the general population of Poles (Wojtyniak et al. 2005), and the avoidance of alcohol and other harmful substances was not connected with religious motivation. In addition to the religious factor, cultural reasons can also have a positive impact both on more drinking in men and a lack of a moderating effect. It can be identified as a social norm that it is deemed more acceptable for men to drink alcohol compared to women (Bailly et al. 1991), who are usually negatively labeled in society when drinking too much alcohol (Wilsnack et al. 2000).

The hypothesis about the moderating role of age in the link between religiosity and happiness independent of gender was not confirmed. The interactions of both men and women between religiosity and age did not explain happiness. The lack of a positive link in our study between age and happiness in the men and a negative correlation among the women probably has its roots in the multiple sclerosis disease, which has a chronic and progressive character and negatively influences the quality of life. Contrary to this explanation, both in men and women, illness duration was not negatively connected with happiness. In the case of the women, this could be a result of the reduction in financial status, which goes hand in hand with age, especially since the financial status of women was found to be the most significant after religiosity and the second positive predictor of happiness.

The obtained results can be interpreted within the concept of the religious meaning-oriented system (Park 2007, 2010) and Pargament ROS. This cognitive–emotional consistent and integrated religious structure facilitates finding meaning and direction, delivering religious sources to effectively cope with chronic illness and interpret the world as a coherent, predictable, and friendly place to live. This religious function in finding purpose and meaning in life has been emphasized regardless of gender. Consistent with the suggestions of Frankl (2009), who treated finding meaning as a necessary condition for a happy life, and the same as Seligman (2002), who interprets purposeful and meaningful life as a way to achieve happiness, meaning as a result of religiosity was related to the happiness of multiple sclerosis patients from Poland but only in women. Among men, contrary to women, religiosity without religious meaning was positively directly related to happiness which can be interpreted as men not needing religious meaning to obtain life satisfaction.

It supports the theory of Frankl that it is possible to find purpose and significance despite experiencing harmful and difficult circumstances such as those due to chronic and deadly illnesses and due to suffering as a result of nondeserved diseases, which can be transformed into something fruitful and filled with hope (Frankl 2009).

From a theoretical point of view, the existential mechanism underlying the relationship between religiosity and the happiness of multiple sclerosis patients from Poland was confirmed. It is consistent with the claim of Luttmer (Luttmer 2005) that religiosity is positively correlated with happiness even when demographic variables are taken into account. In addition, some gender differences in this sample were found. The women were more religious and more easily found meaning in religion than the men. Their religiosity was positively linked to finding meaning and to less alcohol intoxication and indirectly through these variables, was positively related to happiness. The beneficial effect of religiosity on happiness rooted in less alcohol drinking was not confirmed in men. Additionally, a detrimental role of religiosity was identified among men with high financial status. In the group of wealthy men, religiosity was negatively correlated with happiness. Both for men and women, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, educational level, and illness duration did not predict happiness, but financial status was the strongest positive predictor of a happy life. Older women were less happy, the same as men living in small places.

From a practical point of view, recipients of these findings, such as individuals diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, members of their families, and caregivers, should remember that it is a heterogeneous population, and there is no one universal factor that can positively influence their happiness. The achieved results have suggested the beneficial effect of religiosity but did not indicate what form of religious commitment (individual or institutional) leads to happiness and the mechanism of influence among men. Involvement in religious practices is recommended for all different groups of Roman Catholic patients from Poland diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. They should be encouraged to develop and to involve themselves in the religious sphere of life as a benevolent factor for their happiness. Indeed, their preferences regarding engaging in different religious activities should be recognized to establish the best way of religious expression adequate to the severity of their disease and mobility possibilities and the function the religion fills in their lives such as providing meaning, social support, emotional regulation, and encouraging a healthy lifestyle. Improving the financial situation for all patients and moving to a bigger city in the case of men could lead to greater feelings of happiness. This purpose should be realistic because health problems and other circumstances can be an obstacle to changing jobs, finding an additional source of income or a part-time job in the case of the retired and pensioners. The same is the case among men from rustic areas or small towns, where social connections and support and financial issues could prevent moving. According to the results, financial status positively correlated with the place of residence in both men and women.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations of the study should be emphasized. The sample was homogeneous regarding denomination, and every participant declared Roman Catholic affiliation, which means that the generalizability of the results is limited to Roman Catholic Church representatives suffering from multiple sclerosis. Some research has indicated differences in the relationship between religiosity and subjective well-being or happiness in dependence of religious affiliation (Stulp et al. 2019), but others have indicated a lack of it (Rizvi and Hossain 2017). In addition, the race, cultural, and economic factors which can modify these links were controlled. Conducted studies in other social and cultural backgrounds and economic conditions, especially those which are less religious and where the religious socialization is less common, could lead to interesting results and act as a good comparable plane. Future research should encompass more specific measures regarding subjective well-being such as eudaimonic and cognitive on the one hand, as well as hedonic and effective on the other hand. In addition, the use of more religiosity indicators, divided on personal, institutional, and devotional levels (Hackney and Sanders 2003), is needed. This could give a more comprehensive picture of the relationship between the plethora of aspects of religiosity and well-being and the search for some patterns and trends in this issue showing which religious aspects are positively related to a particular indicator of happiness, which are not connected, and which are negatively correlated.

One disadvantage of this study that must be considered and requires explanation is the strong links between religiosity and religious meaning, which can be interpreted as a manifestation (indicators) of the same variable explanation. On the hand, they are strongly linked constructs but still theoretically different. The positive proof for this thesis is the lack of gender differences between religiosity and happiness, when religiosity was introduced to the research model and consisted of the summing up the results of religious orientation and religious meaning. In both men and women, the correlation was weak, positive, and statistically significant. The distinction in the research model between religious orientation and religious meaning as two separate constructs resulted in that religious orientation was positively related to happiness in men but not in women, and inversely, religious meaning was correlated with happiness among women but not in men.

Another suggestion regards exploring other potential mechanisms underlying the links between religiosity and happiness, focusing on other religious functions, such as social support, effect regulation, and the promotion of a healthy lifestyle (Morton et al. 2017).

The most crucial disadvantage of this study is the cross-sectional design. Even though almost all recent research has indicated religiosity as an antecedent of happiness, only longitudinal studies could confirm that religiosity leads to happiness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Data curation, M.S.; Formal analysis, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Funding acquisition, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Methodology, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Project administration, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk) and H.B.-P.; Software, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Supervision, M.W. (Maciej Wilski), W.B. and A.P. (Andrzej Potemkowski); Validation, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Visualization, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Writing–original draft, M.W. (Marcin Wnuk); Writing–review & editing, M.W. (Maciej Wilski), W.B., M.Ż., P.S., K.K.-T., J.T., A.C., A.K., B.Z.-P., K.K.-B., N.M., M.A.-S., A.S., J.Z., A.R., M.R., R.R.S., Z.K., B.L., A.P. (Adam Perenc), M.P. and A.P. (Andrzej Potemkowski). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by authors sources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee of Institute of Psychology at the University of Szczecin (KB 15/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acheampong, Abenaa B., Sonam Lasopa, Catherine W. Striley, and Linda B. Cottler. 2016. Gender Differences in the Association Between Religion/Spirituality and Simultaneous Polysubstance Use (SPU). Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1574–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achour, Meguellati, Mohd Roslan Mohd Nor, Bouketir Amel, Haji Mohammad Bin Seman, and Mohd MohdYusoff. 2017. Religious commitment and its relation to happiness among muslim students: The educational level as moderator. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1870–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, James L. 2019. Amos (Version 26.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: IBM SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, Rebecca C., Roderick S. Carman, and Morris A. Forslund. 1991. Gender differences in drinking motivations and outcomes. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 125: 649–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, Nigel. 2011. A cross-national test of the uncertainty hypothesis of religious belief. Cross-Cultural Research 45: 318–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, David. 2021. Age and life satisfaction: Getting control variables under control. Sociology 55: 421–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkessel, Jana B., Jochen E. Gebauer, Mohsen Joshanloo, Wiebke Bleidorn, Peter J. Rentfrow, Jeff Potter, and Samuel D. Gosling. 2021. National religiosity eases the psychological burden of poverty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118: e2103913118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodogai, Simona Ioana, Şerban Olah, and Gabriel Roşeanu. 2020. Religiosity and Subjective Well-Being of the Central and Eastern European’s Elderly Population. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 784–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F. Matthiessen. 2013. The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Medical Patients in Germany. Journal of Religion and Health 44: 321–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislaghi, Beniamino, and Lori Heise. 2020. Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociology of Health and Illness 42: 407–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cokley, Kevin O'Neal, Samuel Beasley, Andrea Holman, Collette Chapman-Hilliard, Brettjet Cody, Bianca Jones, Shannon McClain, and Desire Taylor. 2013. The moderating role of gender in the relationship between religiosity and mental health in a sample of Black American college students. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 16: 445–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, Patrick J., Stephen G. West, and John F. Finch. 1996. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods 1: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vaus, David, and Ian McAllister. 1987. Gender differences in religion: A test of the structural location theory. American Sociological Review 52: 472–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Eunkook M. Suh, Richard E. Lucas, and Heidi L. Smith. 1999. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin 125: 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Louis Tay, and David G. Myers. 2011. The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101: 1278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G. 1991. Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32: 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esat, Gulden, Susan Day, and Bradley H. Smith. 2021. Religiosity and happiness of Turkish speaking Muslims: Does country happiness make a difference? Mental Health, Religion & Culture 24: 713–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, Viktor E. 2009. Man’s Search for Meaning. Warsaw: Black Sheep Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garssen, Bert, Anja Visser, and Grieteke Pool. 2021. Does spirituality or religion positively affect mental health? meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 31: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Phyllis A., David Feldman, Royda Crose, Eva Schoen, Gene Griffing, and Jui Shankar. 2002. The role of religious beliefs in coping with chronic illness. Counseling and Values 46: 162–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, Charles H., and Glenn S. Sanders. 2003. Religiosity and mental health: A meta–analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R. David, and Marta Elliott. 2014. Cross-national analysis of the influence of cultural norms and government restrictions on the relationship between religion and well-being. Review of Religious Research 56: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, Martin, Thomas Hillemacher, Elmar Gräsel, Sebastian Tigges, Martin Winterholler, Dieter Heuss, Max-Josef Hilz, and Bernhard Neundörfer. 2002. Subjective experience and coping in ALS. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders 3: 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, Peter, and Michael Argyle. 2002. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: A compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 33: 1073–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, Cheryl L., Laura A. Lewellyn, and Mary Jo Rathweg. 2005. Exploring religion-health mediators among African American parishioners. Journal of Health Psychology 10: 511–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, Abigail, and Adrian Wells. 2003. Religion and mental health: Towards a cognitive-behavioural framework. British Journal of Health Psychology 8: 359–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, Rex B. 2005. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2013. Religion and spirituality in coping with acute and chronic illness. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol. 2): An Applied Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Annette Mahoney and Edward P. Shafranske. New York: American Psychological Association, pp. 275–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, Aleksandr, Joni Sasaki, Christopher Zou, Heejung Kim, and Cecilia Cheng. 2013. Uncertainty avoidance moderates the link between faith and subjective well-being around the world. The Journal of Positive Psychology 8: 242–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, Eszter, Bettina Franciska Piko, and Kevin Michael Fitzpatrick. 2011. Religiosity as a protective factor against substance use among Hungarian high school students. Substance Use & Misuse 46: 1346–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2015. The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 2292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2009. Religijność a Jakość życia w Perspektywie Mediatorów Psychospołecznych. Opole: Redakcja Wydawnictw WT UO. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2011. Skala Religijnego Systemu Znaczeń (SRSZ). In Psychologiczny Pomiar Religijności. Edited by Marek Jarosz. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, pp. 153–68. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2014. The religious meaning system and subjective well-being: The mediational perspective of meaning in life. Archiv für Religionspsychologie/Archive for the Psychology of Religion 36: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrič, Miran, and Sergej Flere. 2008. The role of culture in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health 47: 164–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, Aryeh. 2015. The relation between prayer type and life satisfaction in religious Jewish men and women: The moderating effects of prayer duration and belief in prayer. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 25: 211–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, Aryeh, and Jeffrey P. Bjorck. 2016. Religious support and psychological well-being: Gender differences among religious Jewish Israelis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19: 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 75: 914–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, Vivian Miu-Chi, and Michael Harris Bond. 2013. Examining the relation of religion and spirituality to subjective well-being across national cultures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 5: 304–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttmer, Erzo. 2005. Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics 120: 963–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, John. 2002. The Age Universal I-E Scale-12 and orientation toward religion: Confirmatory factor analysis. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 136: 555–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, Kanti V. 1970. Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika 57: 519–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, Dudley, K. Elizabeth Oakes, Joseph W. Ciarrocchi, William J. Sneck, and Kevin Gillespie. 2007. Spirituality and God-attachment as predictors of subjective well-being for seminarians and nuns in India. In Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, Kelly R., Jerry W. Lee, and Leslie R. Martin. 2017. Pathways from religion to health: Mediation by psychosocial and lifestyle mechanisms. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9: 106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooney, Jennifer, and Eric Woodrum. 2002. Religious coping and church-based social support as predictors of mental health outcomes: Testing a conceptual model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 359–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Shigehiro, and Ed Diener. 2014. Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychological Science 25: 422–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam. 2010. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction across Nations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 13: 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, Kenneth I. 2008. Making sense of caregiving for persons with multiple sclerosis (MS): The dimensional structure of sense making and relations with positive and negative adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 15: 241–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1999. The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2006. Exploring relations among religiosity, meaning, and adjustment to lifetime and current stressful encounters in later life. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal 19: 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2007. Religiousness/spirituality and health: A meaning systems perspective. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 30: 319–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L. 2010. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 136: 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L., Cheryl L. Holt, Daisy Le, Juliette Christie, and Beverly Rosa Williams. 2018. Positive and negative religious coping styles as prospective predictors of well-being in African Americans. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 318–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Eastern andWestern Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importanceofreligion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Piko, Bettina F., Eszter Kovacs, Palma Kriston, and Kevin M. Fitzpatrick. 2012. “To believe or not to believe?” Religiosity, spirituality, and alcohol use among Hungarian adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 73: 66674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloma, Margaret M., and Brian F. Pendleton. 1990. Religious domains and general well-being. Social Indicators Research 22: 255–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöhls, Katharina. 2021. A complex simplicity: The relationship of religiosity and nonreligiosity to life satisfaction. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60: 465–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, Guillermo, Daniel J. Feaster, Seth J. Schwartz, Indira Abraham Pratt, Lila Smith, and José Szapocznik. 2004. Religious involvement, coping, social support, and psychological distress in HIV-seropositive African American mothers. AIDS and Behavior 8: 221–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinzing, Michael, Patty Van Cappellen, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2021. More than a momentary blip in the universe? Investigating the link between religiosity and perceived meaning in life. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 1461672211060136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Mohd Ahsan Kabir, and Mohammad Zakir Hossain. 2017. Relationship between religious belief and happiness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1561–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, Oliver C., Karina Hanson, Guy Hayward, and David Lorimer. 2019. Age and cultural gender equality as moderators of the gender difference in the importance of religion and spirituality: Comparing the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Journal of Scientific Study of Religion 58: 301–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2015. How Religious are American Women and Men? Gender Differences and Similarities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 616–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Brenda, and Jeffrey S. Podoshen. 2013. An examination of materialism, conspicuous consumption and gender differences. International Journal of Consumer Studies 37: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, Martin E. P. 2002. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Richard P., and Emilia Bagiella. 2002. Claims about religious involvement and health outcomes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 24: 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, Richard P., Emilia Bagiella, Larry VandeCreek, Margot Hover, Carlo Casalone, T. Jinpu Hirsch, Yusuf Hasan, Ralph Kreger, and Peter Poulos. 2000. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? The New England Journal of Medicine 342: 1913–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, Olga, Detlef Fetchenhauer, and Thomas Schlösser. 2013. Why are religious people happy? The effect of the social norm of religiosity across countries. Social Science Research 42: 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, Patrick R., Spencer Clayton, and William Swinyard. 2015. Religious orientation and life aspirations. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 470–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulp, Henk P., Jurrijn Koelen, Annemiek Schep-Akkerman, Gerrit G. Glas, and Liesbeth Eurelings-Bontekoe. 2019. God representations and aspects of psychological functioning: A meta-analysis. Cogent Psychology 6: 1647926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreri, Cydney J., and David S. Glenwick. 2013. The relationship of religious and general coping to psychological adjustment and distress in urban adolescents. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 1188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, Alan J., Brenda L. Banwell, Frederik Barkhof, William M. Carroll, Timothy Coetzee, Giancarlo Comi, Jorge Correale, Franz Fazekas, Massimo Filippi, Mark S. Freedman, and et al. 2018. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. The Lancet Neurology 17: 162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousis, Ioannis, Evangelos Karademas, and Dimitra Kalatzi. 2013. The role of core self-evaluations in the relationship between religious involvement and subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 16: 138–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizehfar, Fatemeh, and Azita Jaberi. 2017. The Relationship Between Religious Beliefs and Quality of Life among Patients With Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1826–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VonDras, Dean D., R. R. Schmitt, and D. Marx. 2007. Associations between aspects of spiritual well-being, alcohol use, and related social-cognitions in female college students. Journal of Religion and Health 46: 500–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, Cristel, Marié P. Wissing, and Q. Michael Temane. 2009. Gender, spirituality and psychological well-being. Journal of Psychology in Africa 19: 153–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Paul J., Nathaniel D. Jones, and Ronald J. Morris. 2004. Religious orientation and attitudes toward money: Relationships with narcissism and the influence of gender. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 7: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilsnack, Richard W., Nancy D. Vogeltanz, Sharon C. Wilsnack, and T. Robert Harris. 2000. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: Cross-cultural patterns. Addiction 95: 251–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, Marcin, and Jerzy Tadeusz Marcinkowski. 2014. Do existential variables mediate between religious-spiritual facets of functionality and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, Marcin. 2021. Indirect relationship between Alcoholics Anonymous spirituality and their hopelessness: The role of meaning in life, hope, and abstinence duration. Religions 12: 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyniak, Bogdan, Jacek Moskalewicz, Jakub Stokwiszewski, and Daniel Rabczenko. 2005. Gender-specific mortality associated with alcohol consumption in Poland in transition. Addiction 100: 1779–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).