Risk Preference and Religious Beliefs: A Case in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Pascal’s Wager: From Theology to Psychology

1.2. Risk Preference Theory: Foundation and Extension

1.3. Related Research in China

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytic Methods

3. Results

3.1. Logistic Regression

3.2. Robustness

3.3. Heterogeneity

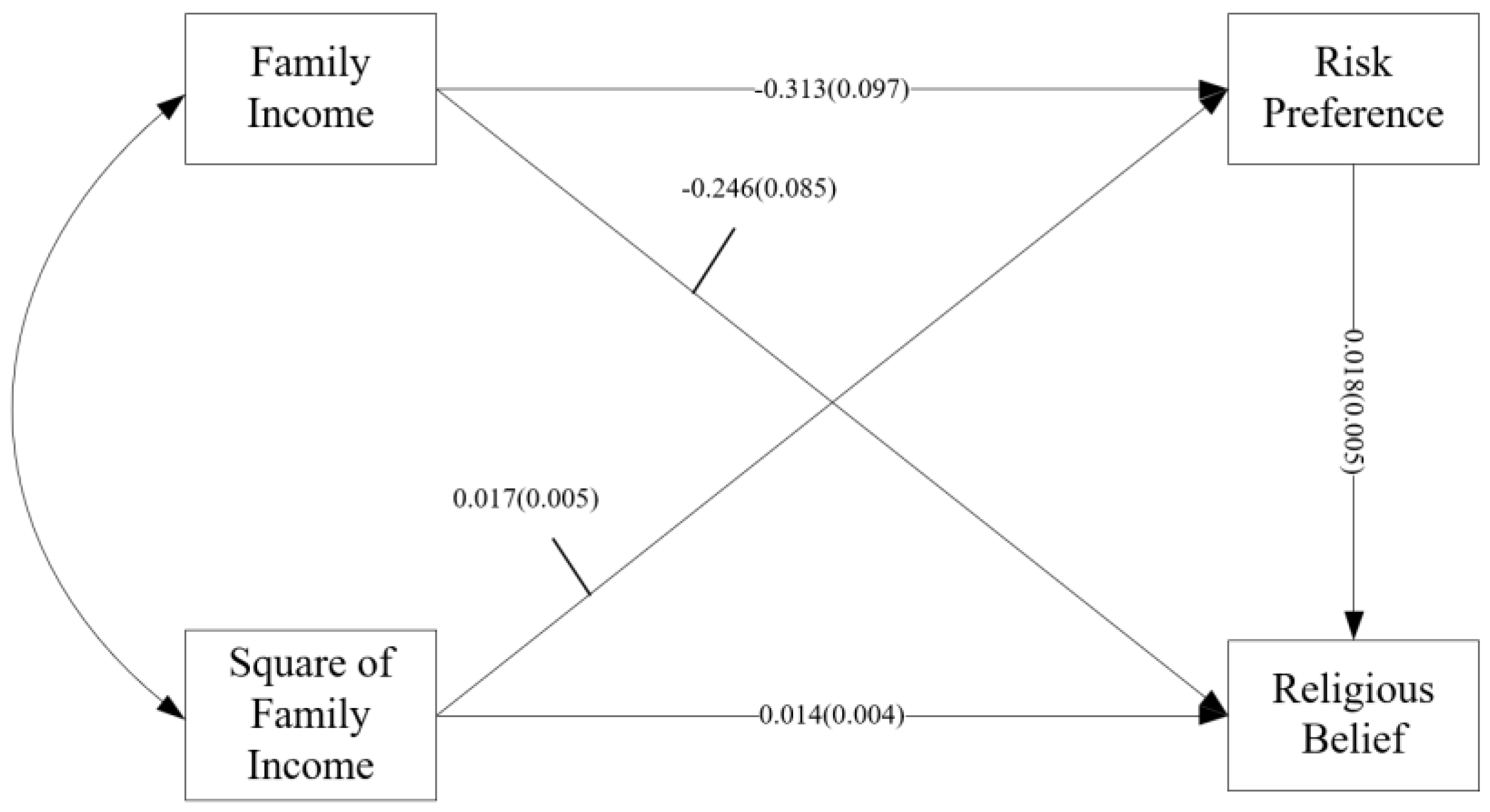

3.4. Mediation Analysis

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alper, Sinan, and Nebi Sümer. 2019. Control Deprivation Decreases, Not Increases, Belief in a Controlling God for People with Independent Self-Construal. Current Psychology 38: 1490–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Robert. 1995. Recent Criticisms and Defenses of Pascal’s Wager. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 37: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atran, Scott, and Ara Norenzayan. 2004. Religion’s evolutionary landscape: Counterintuition, commitment, compassion, communion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27: 713–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, Marie. 2009. Reifying Sex Difference Isn’t the Answer: Gendering Processes, Risk, and Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 252–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis-Tan, Andrew, and Felicia F. Tian. 2022. Fluidity of Faith: Predictors of Religion in a Longitudinal Sample of Chinese Adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 61: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, Jeremy. 2004. Risk preferences and gender differences in religiousness: Evidence from the World Values Survey. Review of Religious Research 46: 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, Jeremy, and James D. Montgomery. 2007. The devil made her do it? Evaluating risk preference as an explanation of sex differences in religiousness. In Social Psychology of Gender. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 24, pp. 187–229. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the Study of Religious Commitment. Religious Education 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, Luciens. 2013. The hidden God: A study of tragic vision in the Pensees of Pascal and the Tragedies of Racine, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeffel, Gerald J., and George S. Howard. 2010. Self-Report: Psychology’s Four-Letter Word. The American Journal of Psychology 123: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Kristopher J. Preacher. 2010. Quantifying and Testing Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models When the Constituent Paths Are Nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research 45: 627–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, Robert A. 2009. Why Gods Persist: A Scientific Approach to Religion. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, John P. 2009. Gender, Risk, and Religiousness: Can Power Control Provide the Theory? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 232–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, John P. 2019. Risk Preference Theory and Gender Differences in Religiousness: A Replication and Extension. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 210–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsee, Christopher K., and Elke U. Weber. 1997. A Fundamental Prediction Error: Self-Others Discrepancies in Risk Preference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 126: 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Anning, and Dongyu Li. 2021. Are Elders from Ancestor-Worshipping Families Better Supported? An Exploratory Study of Post-reform China. Population Research and Policy Review 40: 475–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Anning, Xiaozhao Yousef Yang, and Weixiang Luo. 2017. Christian sIdentification and Self-Reported Depression: Evidence from China. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 765–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Jianguo, and Panpan Yang. 2019. Network Pledge: Lucky Game, Spiritual Selfishness and Identity Dilemma. Exploration and Free Views 1: 68–75+142–143+145. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1984. Choices, values and frames. American Psychologist 39: 341–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, Aaron C., Danielle Gaucher, Jamie L. Napier, Mitchell J. Callan, and Kristin Laurin. 2008. God and the government: Testing a compensatory control mechanism for the support of external systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95: 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, Aaron C., Jennifer A. Whitson, Danielle Gaucher, and Adam D. Galinsky. 2009. Compensatory Control: Achieving Order Through the Mind, Our Institutions, and the Heavens. Current Directions in Psychological Science 18: 264–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keister, Lisa A. 2003. Religion and wealth: The role of religious affiliation and participation in early adult asset accumulation. Social Forces 82: 175–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamaster, Reid J., and Anning Hu. 2014. Popular Buddhists: The Relationship between Popular Religious Involvement and Buddhist Identity in Contemporary China. Sociology of Religion 75: 234–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xiangping. 2017. Private Believe and Average Society—The Pattern of Religious Believe and its Value in Contemporary Chinese. Academic Monthly 49: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yi, Robert Woodberry, Hexaun Liu, and Guang Guo. 2020. Why are Women More Religious than Men? Do Risk Preferences and Genetic Risk Predispositions Explain the Gender Gap? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59: 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Xianghui. 2019. China: Some Exceptions of Secularization Thesis. Religions 10: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Eric Y. 2010. Are Risk-Taking Persons Less Religious? Risk Preference, Religious Affiliation, and Religious Participation in Taiwan. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 172–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, Rui, Renato Frey, David Richter, Jürgen Schupp, and Ralph Hertwig. 2018. Risk Preference: A View from Psychology. Journal of Economic Perspectives 32: 155–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S. 2000. Going to Hell in Asia: The Relationship between Risk and Religion in a Cross Cultural Setting. Review of Religious Research 42: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S., and John P. Hoffmann. 1995. Risk and Religion: An Explanation of Gender Differences in Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan S., and Rodney Stark. 2002. Gender and Religiousness: Can Socialization Explanations Be Saved? American Journal of Sociology 107: 1399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Worldwide Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Rongping, and Linlu Liu. 2012. Reasons for ‘Rural Religion Fever’: Religion Social Risk Hypothesis. Journal of South China Agricultural University (Social Science Edition) 1: 108–16. [Google Scholar]

- Saka, Paul. 2001. Pascal’s Wager and the Many Gods Objection. Religious Studies 37: 321–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2011. Believing, Bonding, Behaving, and Belonging: The Big Four Religious Dimensions and Cultural Variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, Magali Clobert, Adam B. Cohen, Kathryn A. Johnson, Kevin L. Ladd, Matthieu Van Pachterbeke, Lucia Adamovova, Joanna Blogowska, Pierre-Yves Brandt, Cem Safak Çukur;, and et al. 2020. Believing, Bonding, Behaving, and Belonging: The Cognitive, Emotional, Moral, and Social Dimensions of Religiousness across Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 51: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney. 1996. Religion as context: Hellfire and delinquency one more time. Sociology of Religion 57: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney. 2002. Physiology and Faith: Addressing the “Universal” Gender Difference in Religious Commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney. 2017. Why God?: Explaining Religious Phenomena. West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sullins, Donald Paul. 2006. Gender and Religion: Deconstructing Universality, Constructing Complexity. American Journal of Sociology 112: 838–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, William, ed. 2005. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiuhua, and Sung Joon Jang. 2018. The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis. Religions 9: 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Dedong, and Eric. Y. Liu. 2013. Religious Involvement and Depression: Evidence for Curvilinear and Stress-Moderating Effects Among Young Women in Rural China: Religious Involvement And Depression. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 349–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2006. The Red, Black, and Gray Markets of Religion in China. The Sociological Quarterly 47: 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang, and Anning Hu. 2012. Mapping Chinese Folk Religion in Mainland China and Taiwan. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 505–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Jiexia Elisa. 2010. Contrasting Trends of Religious Markets in Contemporary Mainland China and in Taiwan. Journal of Church and State 52: 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chunni, and Yunfeng Lu. 2020. The measure of Chinese religions: Denomination-based or deity-based? Chinese Journal of Sociology 6: 410–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chunni, Qi Cui, and He Sheng. 2022. How did Christianity Rise in Contemporary Chinese Cities? The World Religious Cultures 1: 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Chunni, Yunfeng Lu, and He Sheng. 2021. Exploring Chinese folk religion: Popularity, diffuseness, and diversities. Chinese Journal of Sociology 7: 575–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Guoqi. 2005. The Influence of the “Guan-gong Culture” on the Underworld Crime. Journal of Guizhou University (Social Science) 4: 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Fengtian, Rongping Ruan, and Li Liu. 2010. Risk, social security and religious beliefs. China Economic Quarterly 9: 829–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xing. 2017. Folk Belief and Its Legitimization in China. Western Folklore 76: 151–65. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Measure | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious belief | Belief in Buddha, Taoist god, Allah, God, Jesus Christ, ghosts, or geomancy = 1, other = 0 | 0.580 | / |

| Folk religion | Belief in more than one deity or belief in ancestor only = 1, other = 0 | 0.537 | / |

| Eastern religion | Only belief in Buddha/Bodhisattva or Taoist deity = 1, other = 0 | 0.024 | / |

| Western religion | Only belief in Allah, God, or Jesus Christ = 1, other = 0 | 0.019 | / |

| Risk preference (1–6) | The higher the number, the higher the risk preference | 2.263 | 1.781 |

| Age | Years | 47.917 | 16.078 |

| Marriage | Married or cohabiting = 1, other = 0 | 0.812 | / |

| Gender | Male = 1, female = 0 | 0.498 | / |

| Urban resident | Urban = 1, rural = 0 | 0.429 | / |

| Family income | The log of the total income of the family over the past 12 months plus 1 | 10.607 | 1.057 |

| Ethnic minority | No = 1, yes = 0 | 0.851 | / |

| Education years | Years | 8.050 | 4.954 |

| Subjective health (1–5) | The higher the number, the less healthy | 3.058 | 1.121 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample from CFPS Survey | Matched Sample from CFPS Survey | Sample from CGSS | |

| Religious belief | |||

| Risk preference | 0.029 *** (0.008) | 0.043 *** (0.008) | 0.058 *** (0.024) |

| Age | −0.007 *** (0.001) | −0.009 *** (0.001) | 0.008 *** (0.003) |

| Urban resident | −0.042 *** (0.0196) | −0.022 ** (0.013) | −0.051 (0.088) |

| Gender (rf: female) | −0.332 *** (0.027) | −0.297 *** (0.029) | −0.243 *** (0.076) |

| Education years | −0.051 *** (0.003) | −0.052 *** (0.004) | −0.039 *** (0.010) |

| Ethnic minority | −0.070 (0.105) | 0.0107 ** (0.045) | −0.655 *** (0.202) |

| Marriage (rf: the unmarried) | 0.033 (0.036) | 0.060 (0.038) | −0.108 (0.087) |

| Health | 0.060 *** (0.011) | 0.086 *** (0.013) | 0.046 (0.038) |

| Family income | −0.463 *** (0.120) | −0.627 *** (0.135) | −0.134 *** (0.062) |

| Square of family income | 0.026 *** (0.006) | 0.033 *** (0.006) | 0.014 *** (0.004) |

| Province dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Intercept | 2.800 ** (0.628) | 3.622 ** (0.712) | 0.523 (0.438) |

| Inflate | |||

| Age | / | / | 0.045 *** (0.006) |

| Ethnic minority | / | / | −0.700 *** (0.300) |

| Intercept | / | / | −1.788 *** (0.515) |

| N | 24,743 | 21,276 | 3925 |

| Variable | Measure | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious belief | The number of times parties prayed for good luck in the past year | 0.413 | 0.963 |

| Risk preference (1–7) | The higher the number, the higher the risk preference | 3.559 | 1.573 |

| Age | Year | 51.416 | 16.898 |

| Marriage | Married or cohabiting = 1, other = 0 | 0.760 | / |

| Gender | Male = 1, female = 0 | 0.480 | / |

| Urban resident | Urban resident = 1, rural = 0 | 0.376 | / |

| Family income | The log of the total income of the family over the past 12 months plus 1 | 10.432 | 2.120 |

| Ethnic minority | No = 1, yes = 0 | 0.931 | / |

| Education years | Year | 9.050 | 4.940 |

| Subjective health (1–5) | The higher the number, the less healthy | 3.548 | 1.076 |

| Folk Beliefs | Eastern Beliefs | Western Beliefs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk preference | 0.033 *** (0.014) | −0.010 (0.025) | −0.030 (0.030) |

| Age | −0.008 *** (0.001) | −0.003 (0.003) | 0.006 * (0.004) |

| Urban resident | −0.045 *** (0.014) | 0.018 (0.050) | −0.015 (0.056) |

| Gender (rf: female) | −0.294 *** (0.027) | −0.700 *** (0.088) | −0.917 *** (0.104) |

| Education years | −0.051 *** (0.003) | −0.052 *** (0.011) | −0.066 *** (0.012) |

| Ethnic minority | 0.128 (0.044) | −0.031 (0.146) | −1.375 *** (0.131) |

| Marriage (rf: the unmarried) | 0.019 (0.036) | −0.002 (0.113) | 0.563 *** (0.142) |

| Health | 0.069 *** (0.012) | −0.076 ** (0.035) | 0.010 (0.004) |

| Family income | −0.469 *** (0.122) | −0.203 (0.318) | −0.515 * (0.294) |

| Square of family income | 0.027 *** (0.006) | 0.007 (0.016) | 0.028 * (0.015) |

| Province dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Intercept | 2.643 ** (0.634) | −0.234 (1.683) | 0.448 (1.532) |

| Risk preference | 24,743 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, D. Risk Preference and Religious Beliefs: A Case in China. Religions 2022, 13, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111072

Zhou D. Risk Preference and Religious Beliefs: A Case in China. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111072

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Dao. 2022. "Risk Preference and Religious Beliefs: A Case in China" Religions 13, no. 11: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111072

APA StyleZhou, D. (2022). Risk Preference and Religious Beliefs: A Case in China. Religions, 13(11), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111072