Abstract

The development of the primarily women-of-color-led movement for transformative justice has also shed light on the fact that abolition requires not just the transformation of social relations and place, but the transformations of subjectivity itself. This movement recognizes that violence is not just enacted against oppressed communities but is enacted with them, and hence the line between those who harm and those who face harm is often illusory. The movement for transformative justice—for accountability without disposability—calls on us to create different systems of relationality, which, in turn, transform who we think we are as people. Essentially, we are required to embark on an uncharted journey that will result in the creation of new selves we would not now recognize. Abolition can be seen as a process and a methodology rather than a presumed destination. To identify abolitionist methodologies, it can be helpful to look at unexpected places rather than presume that some spaces and peoples are necessarily more abolitionist than others. Consequently, this essay will look at abolitionism in an unexpected place, Christian evangelicalism.

1. Introduction

People are declaring that they are not content with living in a carceral state, and they are building a movement that has the potential to birth something novel, restorative, and transformative. We serve a God who desires liberation, reconciliation, and reintegration for those behind bars. God invites the church to participate in setting the captives free (Gilliard 2018, p. 199).Dominique Gilliard (Director of Racial Righteousness and Reconciliation for the Evangelical Covenant Church)

Penal abolitionism is not merely a decarceration programme, but also an approach, a perspective, a methodology, and most of all a way of seeing Vincenzo Ruggiero (2011)

Abolition is ultimately a theological project. By that I mean, it is not simply about dismantling the prison industrial complex or even carceral systems of control; it is about replacing these systems with a different form of governance and relationality. It is a politics of accountability without disposability. It is thus about a project of creating a different world that simultaneously transforms us into different persons that can live in this different world. I describe abolition as theological because it imagines a world beyond what is given or what is even articulable. Many might argue that the term “theological” is so connected to Christianity that it is of little value to non-Christians. This argument may be valid, and there may well be a better word more suited to describe abolition. However, I find theology helpful for signifying a commitment to a spiritual and political project that is beyond that which we can imagine. I see the turns towards futurism, decolonization, a faith in “otherwise worlds,”, etc., in various strands within critical ethnic studies as theological turns. As Frederick Moten reminds us, white supremacy is not simply about the belief in white superiority, white supremacy structures belief itself.1

In addition, because abolitionism imagines worlds for which we have no words, it is a methodology, as Vincenzo Ruggiero describes above, that is ever-evolving rather than a clear final destination. As the works of Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore make clear, abolitionism cannot be reduced to a simple radical demand to end prisons. Rather, it involves a political and organizing methodology for creating a world in which prisons would not be imaginable. In tracing the genealogy of the concept of “abolition,” Davis contends that the abolition of slavery was limited by its lack of vision of what would replace a system of slavery. Building on the work of W.E.B. Dubois, Davis notes that abolition required more than the negative project of ending formal slavery but it required the positive project of creating democratic institutions that enabled the flourishing of Black life—hence abolition democracy (Davis 2011, p. 95). Davis argues that prison abolition must similarly be a positive project: “Rather than try to imagine one single alternative to the existing system of incarceration, we might envision an array of alternatives that will require radical transformations of many aspects of our society. Alternatives that fail to address racism, male dominance, homophobia, class bias, and other structures of domination will not, in the final analysis, lead to decarceration and will not advance the goal of abolition.” (Davis 2003, p. 108).

Ruth Wilson Gilmore notes that the current abolitionist focus on the “prison industrial complex,” originally termed in order to note the expansive nature of the carceral system, has instead truncated abolitionist politics. She calls for abolitionist geographies that recognize that “freedom is a place” and that abolition requires not simply the dismantling of prisons, but the transformation of place (Gilmore 2018). In this sense her work echoes Indigenous calls for decolonization that are not simply about a demand for the return of stolen land but challenging the manner in which colonization transforms land from a set of relationships to a commodity that can then be stolen (Smith 2014).

The development of the abolition feminist movement for transformative justice has also shed light on the fact that abolition requires not just the transformation of social relations and place, but the transformations of subjectivity itself. This movement recognizes that violence is not just enacted against oppressed communities, but is enacted with them. Hence, the line between those who harm and those who face harm is often illusory. The movement for transformative justice—for accountability without disposability, calls on us to create different systems of relationality which in turn transform who we think we are as people. Essentially, we are required to embark on an uncharted journey that will result in the creation of new selves we would not now recognize. Abolition can be seen as a process and a methodology rather than a presumed destination. To identify abolitionist methodologies, it can be helpful to look to unexpected places rather than presume that some spaces and peoples are necessarily more abolitionist than others. As Gilmore notes, the tendency for abolitionism to be co-opted into a radical chic obscures both the expansive and indeterminate politic that it is (Gilmore 2018). Consequently, this essay will look at abolitionism in an unexpected place, Christian evangelicalism, to explore how abolitionism can be understood as theological methodology that attends to simultaneous subjective and collective transformation.

2. Evangelical Abolitionism

Abolitionism is often presumed to be the property of those considered “radical.” However, this presumption implies that those who identify as politically radical abolitionists are ideologically enlightened and do not require radical transformation. To counter this presumption, it might be easier to identify abolitionism as a methodology when examined among people who do not claim ideological enlightenment, but instead understand themselves as people in need of transformation. My point is not to argue that evangelicalism is a platform that non-evangelicals should join. Rather, it is an example of what an abolitionist methodology could be when engaged by people who do not presume they are on the right side of history. That is, an abolitionist future requires not just creating new social systems, but also creating ourselves as new beings that could live in these systems.

The question arises, what is the point of secular abolitionists engaging evangelical abolitionism specifically? First, for an abolitionist future to materialize, it will actually have to go beyond being a practice employed by activist communities. In expanding beyond more “progressive” communities, it is sensible to engage evangelical communities because they have actually been engaging in critiques of the prison industrial complex since the 1970s and have developed versions of transformative justice2 that reach more conservative communities. Second, while more radical communities certainly engage in self-critique, they tend to make the same level of systemic critique that questions the very assumptions by which they organize. Evangelicals who organize for racial justice, however, do so within the context of theological communities that have arisen from histories of white supremacy. Thus, their work has had to work more consciously on multiple levels—challenging racialization in the larger society while simultaneously challenging the racialization in their own theological and political assumptions. This dual positioning that evangelicals engage in can perhaps provide a model for a more ontological critique that could be helpful for secular abolitionists who might not so consciously critique their own positioning and assumptions. Finally, the practice of actually developing transformative systems is very contextually based. Many more radical organizations begin their praxis within their current organizations and expand from there. However, very different questions arise when trying to build transformative justice systems in churches, particularly evangelical ones. In looking at how transformative justice praxis requires very different approaches in different contexts, an examination of evangelical abolitionism is helpful for the overall project of imagining how abolitionism can build to a larger scale across diverse contexts.

I do not contend that evangelical communities uniquely represent such an intervention. Rather, it provides a helpful case study that could enable an abolitionist methodology to further engage diverse communities that can add to the collective wisdom of what abolition could mean for everyone.

3. Evangelical Historical and Contemporary Engagements with Abolitionism

To provide some historical context for evangelical engagements with abolition, we can begin with the racial reconciliation movement that developed in the 1990s.3 The history of evangelical complicity in white supremacy, be it slavery, racial segregation, or American Indian genocide, is well documented.4 Additionally, as many scholars have noted, the rise of the Christian Right was in large part motivated by racial politics in reaction against the Brown v Board of Education decision.5

In the wake of the LA riots sparked by the acquittal of the police officers who assaulted Rodney King in 1991, white evangelicals finally began to address racism within evangelical churches. The evangelical men’s movement, the Promise Keepers, made racial reconciliation part of its mission, and soon virtually every evangelical organization followed suit in what became known as the racial reconciliation movement. The manner in which racism was addressed in this movement, however, was through the promotion of interracial relationships rather than through addressing institutionalized racism. Nonetheless, even limited engagement with racism did destabilize white evangelicalism, which generally positioned itself as manifesting God’s will on earth.

To manage the anxieties created by these contradictions, white evangelicals attempted to situate the racial reconciliation movement as consistent with rather than an intervention against the history of evangelical race relations. This required a considerable amount of historical amnesia as evangelicalism became imagined as being solely on the side of slavery’s and racial segregation’s abolition.6

Meanwhile, even before the prison abolitionist movement grew in the wake of the first Critical Resistance: Beyond the Prison Industrial Complex conference held in Berkeley, CA in 1999, evangelicals had been organizing for prison reform, particularly under the auspices of Prison Fellowship and its associated lobbying arm, Justice Fellowship, since 1976. Founded by Charles Colson after he was released from prison for his role in the Watergate scandal, Prison Fellowship operates from a conservative evangelical perspective. Yet, the political positions often articulated within conservative evangelical prison organizing movements are positions not commonly associated with conservatives. For example, among the many platforms implicitly or explicitly supported by Prison and Justice Fellowship and other evangelical prison advocates were decarceration for drug offenders; (Colson 1980; Bruce 1997; Colson 1977) minimum wage compensation for prison labor; decarceration of all non-violent offenders (“The first thing we have to do with prisons today is to get the nonviolent people out”) (Forbes 1982; Smarto 1993); prison construction moratoriums (Colson 1985; Mill 1999; Justice Fellowship 2000; Van Ness 1985); eradication of “zero tolerance” policies in public schools;7 eradication of mandatory minimum sentencing and three-strikes legislation; decarceration of the mentally ill;8 suffrage for convicted felons;9 expansion of community sentencing programs;10 and even prison abolition to a very limited degree (Griffith 1993). To this day, Prison Fellowship and other conservative evangelical organizations continue to mobilize conservative evangelicals to support prison reform strategies often associated with the Left.11 They were largely behind the efforts to pressure the Trump administration into supporting prison reform legislation (Miller 2018).

Despite the work of Prison Fellowship and other evangelical prison organizing movements as well as the work done under the auspices of racial reconciliation, the word “abolition” became associated not with prison abolition, but with anti-trafficking organizing within evangelical circles.

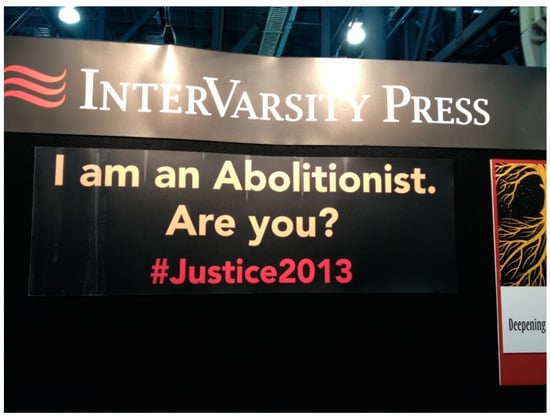

This exhibit from InterVarsity Press (Figure 1), an evangelical press, at the 2013 Justice Conference (an annual conference held for evangelicals mobilizing for social justice) was calling on conference participants not to become involved in anti-prison organizing, but to join the anti-trafficking movement. InterVarsity (which is a large college-based evangelical parachurch organization) holds a week-long program called the Abolitionist Plunge. The goal of this program: “The Abolitionist Plunge is a week-long Urban Project where students are immersed in every aspect of the fight against human trafficking, or modern day slavery. During the course of the week students hear from trafficking survivors, volunteer with local organizations that are fighting against human trafficking, and learn about a God who wants to set all His children free.” (Anderson n.d.).

Figure 1.

Intervarsity Press Exhibit at 2013 Justice Conference (Philadelphia, PA).

Thus, while the prison abolition movement has generally tried to connect legacies of anti-Black racism from slavery through incarceration, the evangelical abolition movement trades on an anti-Black racism in which trafficking supplants the legacy of chattel slavery, as in this assertion that, “During the last two decades worldwide human trafficking totals surpasses that of 400 years of colonial slavery by a million (Powell 2009; see also Olasky 2010; Justice 2016). In fact, trafficking is often described in manner to erase the importance of chattel slavery. According to World Magazine (an evangelical political magazine), “Today 27 million people live on in captivity, their lives worth far less than any colonial era slave.”12 Anti-trafficking is described as the “new abolition movement.” (Alford 2007; See also Blunt 2007; Beaty 2011) In fact, Relevant magazine (an evangelical magazine geared towards evangelicals in their 20s and 30s) published an article on the “U.S. Slave Traffic” that does not address slavery’s connection to anti-Blackness at all.13 This rhetorical strategy follows from the fact that those guilty of the “new slavery” are generally people of color and the rescuers of enslaved women are usually white, thus erasing historical connections between white supremacy and slavery, as well as contemporary connections between neoliberalism and trafficking (Powell 2009; Scimone 2009; Jewell 2007; Abraham 2006; Price 2007). My point is not to oversimplify how slavery manifests itself today but to describe how it is articulated within evangelical discourse. Or as Lyndsey P. Beutin notes, the evangelical anti-trafficking movement reduces slavery of Black peoples to a “useable past.” (Beutin 2017).

In addition, while the prison abolition movement targets carcerality in general, the evangelical abolition movement relies upon carcerality as its primary strategy for addressing trafficking. For example, Gary Haugen’s International Justice Mission, which engages in human rights legal advocacy for victims of human rights violations from a Christian perspective, has become particularly prominent within the evangelical anti-trafficking movement.14 This organization relies on carceral strategies for addressing trafficking. In fact, Haugen has blamed poverty and the lack of law enforcement (Morgan 2014). There has been a plethora of work by feminists, particularly abolition feminists, who have detailed the destructive impact of the anti-violence movement working uncritically with the state and assuming the state is the solution rather than the perpetrator of gender violence (See Kamala Kempadoo 2005; Ritchie 2017; Young Women’s Education Project 2009). Additionally, just as the discussion of trafficking often rests on the disavowal of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, so too does Haugen’s criminal justice work rest on the disavowal of mass incarceration of people of color in the United States. In Terrify No More, he compares the police in the United States which are “the good guys,” to the police in the Global South which are “corrupt and unchecked.”15 In his analysis, police brutality committed in the United States, particularly against people of color, disappears from view (Williams 2007; Human Rights Watch 1998; Andrea Ritchie 2006). Haugen argues that countries in the Global South should “establish a sound legal system that actually works, especially one that works for the poor,” just like the system in the United States, which apparently works well for the poor, despite all indications to the contrary.16

Thus, while prison abolition in more radical circles has been articulated as a racial justice project, abolition within evangelical circles has been articulated as an anti-trafficking project that puts histories of racialization, particularly anti-Black racism, under erasure. However, the trend began to change recently with the increasing prominence of social justice oriented evangelicals of color.

4. People of Color Organizing and Abolitionist Methodologies in Evangelicalism

In the midst of an awakening to racial realities in our nation, a cry to not derail the prophetic call of #blacklivesmatter with all lives matter.

It was not ALL lives that were ripped from their homes in Africa…

It was not ALL lives that were bought and sold by God-fearing white American Christians.

It was not ALL lives that were whipped and beaten on the plantations...

It was not ALL lives that were told “separate but equal” with equal never being equal…

It was not ALL lives that have been victims of police violence, but it was the black life of Oscar Grant.

It was not ALL lives, it was the black life of Trayvon Martin.

It was not ALL lives, it was the black life of Michael Brown.

It was not ALL lives, it was the black life of John Crawford, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland…

It is not ALL lives that the prison industrial complex exploits.

These historical events did not involve the destruction and death of ALL lives, they were black lives that have been systematically targeted and abused by American society.

So next time, white evangelical leaders, you feel the urge to mouth off that “ALL Lives Matter”—CLOSE your mouth and OPEN your eyes, ears, and minds to get yourself some knowledge (Rah 2015). Soong-Chan Rah.

Soong-Chan Rah is an evangelical scholar whose work has focused on the racializing logics within evangelical discourse, particularly as they impact Black and Indigenous peoples. He became a critic of racial reconciliation efforts within evangelicalism that he believed did not account for the afterlife of settler colonialism and slavery. The quote above reflects this sensibility. While evangelicals within the race reconciliation movement might find the slogan, All Lives Matter, compelling, Rah argued for a racial justice analysis that takes seriously the specificity of anti-Black racism. Like Rah, people of color involved in the evangelical racial reconciliation movement have generally become more radicalized since its inception in the 1990s, calling for a shift from racial reconciliation to racial justice.17 This increased radicalization has become particularly apparent in the wake of (1) the rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement; and (2) the election of Donald Trump. In this section, I highlight diverse voices that are illustrative of an evangelical abolitionist methodology. My goal is less to make representative claims about evangelicalism as it is to offer a prolineal genealogy—a story of what evangelicalism could be based on the contested conversations happening with in it.18

Many evangelicals of color began to intensify their efforts against police violence and mass incarceration in reaction to the Black Lives Matter movement. Building on the prior work of organizations such as Prison Fellowship, this work more explicitly centered analyses of anti-Black racism and went beyond calling for reform to challenging the carceral state itself. Many evangelicals were involved in the organizing in Ferguson, which in turn radicalized their politics. For instance, Brenda Salter McNeil, a prominent evangelical preacher on racial reconciliation, noted in her talk at the 2016 Justice Conference how her meeting with leaders at Ferguson challenged her politics with respect to LGBT organizing.19 Lisa Sharon Harper, another prominent Black feminist evangelical, also organized to ensure that InterVarsity Urbana 2015 conference, which gathers thousands of evangelical college students each year and which is held in St. Louis, Missouri, centered voices of Ferguson organizers. This conference featured speaker Michelle Higgins, Director of Worship at South City Church in St. Louis, who spoke very directly not just against racism and police violence, but also against transphobia, capitalism, and other intersecting forms of oppression. She provocatively stated that the evangelical church “has committed adultery with white supremacy.” Additionally, at the 2017 Evangelicals for Life Conference, keynote speaker, Eugene Cho (President of Bread for the World), stated that any evangelical that claims to be “pro-life” must unequivocally state that Black Lives Matter.

Dominique Gilliard’s Rethinking Incarceration, quoted at the beginning of this essay, reflects this shift in evangelical organizing against policing and prisons. Gilliard does not explicitly espouse an abolitionist position in this book. However, his interlocuters are abolitionist, and he works with the Christian Community Development Association’s Mass Incarceration Task Force which does explicitly engage abolitionism. While he does not describe himself as an abolitionist explicitly in his book, Gilliard’s critiques of incarceration go far beyond that of previous evangelical engagements with prison reform by arguing that incarceration itself is based on “dehumanization, exploitation and profiteering.”20 Further, rather than position evangelical theology as the antidote to the problems of incarceration (as is the general approach of Prison Fellowship and similar organizations), Gilliard calls on evangelicals to decarceralize their theology. Incarceration “is a byproduct of the church’s failure to sustain a witness that subverts the power of empire… It is evidence of what transpires when the church forgets its mission, ceases its prophetic witness, and cowers before imperial power.”21 Gilliard’s work suggests abolitionism as a methodology has also informed not only the radicalization of evangelicals of color against policing and prisons, but their approach to evangelicalism itself. That is, abolitionist theologies deconstruct themselves. As David Eng et al. have described queer theory: “queerness remains open to a continuing critique of its exclusionary operations… queer studies disallows any positing of a proper subject of or object for the field by insisting that queer has no fixed political referent.” (Eng et al. 2005). Essentially queer theory focuses on the logics of normalization without presuming a particular category of peoples will also be the ones that are normalized or the ones that will be queered. Similarly, abolitionism must attend to the logics of disposability and carcerality without presuming that there is a fixed category of peoples who will be rendered disposable. Perhaps unconsciously, progressives often rely upon a traditional evangelical framework in their organizing work by presuming there are some people are on the side of justice (or who are “saved”) and those that are perpetually on the side of injustice (or who are damned). Progressive organizing is often based on the premise of organizing around the “right” people with the “right” politics. However, Gilliard’s work queries what if we theologically presume we are the “wrong” people but who work to collectively become better people? Such a project entails creating a different world for which we have no words in which we will become people we would not now be able to recognize.

Such a project requires the recognition that our theology must always be in flux as we collectively learn from our mistakes and questions our assumptions. Indeed, with the majority of white evangelicals voting for President Trump who seemed to personify none of the values white evangelicals previously claimed to prioritize, many evangelicals of color began to conclude that white evangelicals value their whiteness more than Jesus. This tweet from Bishop Talbert Swan (Church of God in Christ) summarizes this sentiment. “Calling a Black POTUS married 25 yrs to 1 wife with 2 children, no mistresses, affairs or scandals, ‘the antichrist’ but a white POTUS married thrice, 5 kids by 3 women, mistresses, affairs & scandals, ‘God’s anointed,’ proves your religion is only a front for white supremacy.”22 The crisis created by Trumpism ran deeper for many evangelicals. The issue was not simply that some “bad” evangelicals supported Trumpism. However, what within evangelicalism enabled Trumpism? Consequently, increasingly more evangelicals of color began asking the question, is evangelicalism itself an inherently colonial and white supremacist project? An example can be found in the conference statement for the Liberating Evangelicalism: Decentering Whiteness Conference (Chicago, September 2019):

Christian evangelicalism, particularly of late, has often been equated with partisan politics and the faulty assumption that all evangelicals are white. Liberating Evangelicalism seeks to challenge this assumption by creating a space for a biblically based, people of color centered movement that is open to all who seek to build a Jesus-centered vision for social justice.

We imagine a space where people of color are at the center rather than the margins of the conversation, a place to build visions of liberation and inclusion, and a place for belonging and community-building with peoples across diverse political and theological perspectives.

By “liberating evangelicalism,” however, this conference does not presume a particular attachment to Christian evangelicalism.

Some may seek to reclaim the term “evangelical” while others, suspicious of its history and contemporary expression, intend to jettison it from their faith identity altogether. We seek to create a space that allows for diverse engagements with biblically rooted faith traditions. In building this space, this gathering also does not presume any particular theological or political perspectives.23

This organizing does not claim to replace a “bad” conservative evangelicalism with a “good” progressive evangelicalism, but instead calls for a theological and political enterprise based on uncertainty. In fact, several speakers at the above-named conference, such as AnaYelsi Sanchez-Velasco and Ken Fong argued that evangelicalism could not be liberated. One speaker Michael Mata, argued that he was now an “evangelical atheist” because he could no longer support that which had been packaged as evangelicalism. Others, such as Soong-Chan Rah argued that white evangelicalism was more invested in whiteness than Jesus and hence was not actually evangelical at all. Additionally, at that conference, Michelle Higgins explicitly articulated an abolitionist politic that made the connections between evangelical and prison abolitionism. She argued that evangelical theology fundamentally challenges white supremacist notions of “innocence.” That is, evangelicalism recognizes that no one is more pure than other people. All are in need of grace and redemption. Or as evangelical activist Shane Claiborne articulated at the 2019 Christian Community Development Association, “No one is beyond reproach or redemption.” Consequently, one must reject incarceration because it is a punishment strategy that presumes that some are less “innocent” than others and hence are disposable. Again, this means that not only are those incarcerated not disposable, but one’s political or theological opponents are not disposable either.

These theological formulations suggest that the process of decolonizing and dismantling white supremacy in Christianity may result in something that we might not even be able to recognize currently. Additionally, as many in this movement have suggested, some of these terms such as “evangelical” may or may not survive the process of decolonization. It coalesces around a commitment towards an open-ended theological praxis and process rather than a commitment to a bounded-set of theological and political principles. Or to quote Daniel J. Camacho, it resists the politics of theological stop-and-frisk. Essentially, this work can be seen as abolitionist theology- it is willing to deconstruct the carceral logics of evangelicalism itself and imagine something else, even when it is not clear what that something else is.

The far-reaching impact of this evangelical abolitionist stream was evident in the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) conference, Caring Well, held in Dallas in October 2019. This conference was organized to address the abuse crisis in Southern Baptist Churches that was publicly exposed by the Houston Chronicle (Downen et al. 2019). This newspaper series chronicled the countless number of survivors in abuse in SBC churches and institutions that have gone unaddressed for decades. This conference was noteworthy in the far reaching critique of the SBC made by speakers, including those in leadership given that the SBC is not known for radical politics. Russell Moore, the head of the ERLC, argued that abuse proliferates when churches think abuse always happens in churches that have the “wrong” theology. Abusers are often the most theologically correct, contended Moore. Diana Langberg, psychologist, argued that the abuse crisis in the Southern Baptist Convention can be connected to the fact that it was created in defense of slavery, and hence was “rotten to the core.” Phillip Bethancourt, Vice President of ERLC, claimed that the question on the table given the abuse crisis was not how should the SBC address the crisis, but will the SBC continue to exist at all? Additionally, Boz Tchvidijian (founder of GRACE which organizes around abuse in churches) stated that the SBC “system is broken.” He stated that if kids were being murdered inside SBC churches and a newspaper wrote an exposé about it, “either the entire denomination would implode or the entire system would have to be dismantled.” He likened sexual abuse to the murder of children. He also specifically called on SBC to renounce its male dominated structures. Beth Moore similarly called on the SBC to renounce is complicity in “misogyny.” Additionally, Chris Moles argued that the SBC needed to fundamentally question its power structures in which pastors have unquestioned authority. As Beth Moore similarly stated, “those who cannot be questioned cannot be trusted.”

However, while the speakers generally recognized that the SBC was fundamentally flawed, the solution it offered was that churches should stop trying to internally address abuse and should instead immediately report abuse to the police. While this recommendation was important in terms of recognizing the complete inability of SBC churches to adequately address abuse, it presumed that the criminal justice system is capable of addressing abuse. However, this context speaks to the importance of the transformative justice movement expanding its organizing scope. Transformative justice calls for the creation of communities that can hold people accountable without rendering them disposable. Transformative justice projects often begin with the assumption that communities need to realize their abilities to address abuse rather than presume that the criminal justice system should be the default.24 Additionally, they are often generally utilized by more politically radical communities. However, centering evangelicalism in this analysis brings forth the question, what does transformative justice organizing look like in contexts where people assume they can handle abuse adequately without the legal system, but are failing miserably? Given the efforts of many churches to address abuse inadequately and privately, traditional transformative strategies may be particularly dangerous in such contexts. Abolitionists invested in transformative justice are then called to reflect on how transformative justice organizing changes depending on context. Further, challenging the logics of carcerality may require a willingness to admit, as did the participants in the above-named SBC conference, that not only is our “system” broken, but the very movements we have created to challenge systems are also broken.

5. Conclusions: Abolitionism as Methodology

From a radical non-evangelical perspective, this evangelical abolitionist critique might seem obvious: Of course evangelicals of color should be questioning evangelicalism because evangelicalism is terrible. However, what I think is significant about these evangelical abolitionist methodologies is that they are internal critiques. These people are not placing themselves outside of their critique and displacing these critiques onto “bad” evangelicals, but are willing to put themselves in a place of theological indeterminacy. Essentially this abolitionist theology requires a rethinking of the division between “the sinners and the saved” in evangelical terms. When Jesus stated that he “came for the sinners, not the saints,” Jesus is articulating the church as not a space to affirm us as we are but to enable us to become something different from what we are. Thus, Jesus’s command to have a church for sinners is actually also a critique of liberation movements. That is, liberation theologies have often positioned God as really being on the side of the “oppressed” rather than the “oppressor.” However, the concept of a church of sinners indicates that God stands against oppression, no matter who commits is. There is no pure community before God—we are churches of sinners, and hence we need to develop church communities that engage in continual and humble self-critique and interrogation to ascertain when, even with good intentions, we may be hurting others. To quote Eugene Cho: “We ask God to move mountains without considering we may need to be the mountain that needs to be moved.”25

However, in secular abolitionist terms, we can think of this abolitionist methodology as a troubling of the division between those perceived to be on the side of justice and those perceived to be on the side of oppression. It is a methodology that recognizes that no one has escaped hundreds of years of white supremacy, settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy unscathed, and hence our movements for liberation must also transform ourselves in the process. As an example, I was once teaching a class in which we got onto a discussion of Trump’s advocacy of a wall at the U.S./Mexico border. All the students in my class where critical of this policy and argued it was an example of racism. I then asked my students, if you were in a conversation with someone who voted for Trump because that person supported the border wall, what would you say to them? They all said that they would not even try to talk to that person because all Trump supporters are hopeless. I then asked them if they were born with the political positions they currently have, and if not, what changed their mind? As it turned out, about half of the students had been Trump supporters the year before. However, now they had trouble even talking to their former selves.

It may be argued that secular social justice organizations also engage in self-critique. However, a lesson to be learned from evangelical abolitionism is the willingness to consider that no only may a movement or organization be in need of improvement, but that it may be fundamentally flawed such that it should no longer exist and that other alternatives may not be knowable at this point. How do we move forward if the way we have been mobilized might actually be “rotten to the core?”

Abolitionism as methodology is something that is essential for all social justice movements. Abolitionism is not simply about the end of the prison industrial complex; it is an end to the world as we know it and an end to ourselves as we know them. Such a journey requires more than having the correct radical political positions—it requires courage and commitment to embark on a collective journey into uncertainty. Those movements that explicitly organize around such abolitionist methodologies, such as the people of color evangelical movement described in this essay, may provide helpful clues towards what this collective journeying might entail.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Frederick Moten. Class Lecture, UC Riverside, April 2, 2014. |

| 2 | Restorative justice and transformative justice are contested concepts. Restorative justice is an umbrella term that describes a wide range of programs which attempt to address harm—from the individual to the systemic level - from restorative and reconciliatory frameworks rather than a punitive framework. That is, as opposed to the criminal justice system that focuses solely on punishing a person who causes harm and removing that person from society through incarceration, restorative justice attempts to involve all parties (the person who caused harm, the person who was harmed, and community members) in determining the appropriate response to a harm in an effort to restore the community to wholeness. However, as restorative justice became popularized through being increasingly attached to the criminal justice system through diversionary programs, organizers operating from an abolition feminist perspective sought to develop a framework that did not rely on the criminal justice system. Transformative justice emerged as a political organizing project geared towards creating communities of mutual accountability within the context of transforming structures of oppression in society at large. For more see (Piepzna-Samarasinha and Dixon 2020; Zehr 2015). |

| 3 | For a more in-depth description of this movement, see Smith (2019). |

| 4 | See for example, Heltzel (2009). |

| 5 | See Smith, Unreconciled, op cit; (Rosenberg and Rosenberg 1989; Balmer 2021). |

| 6 | See Smith, Unreconciled op cit for a more extended analysis. |

| 7 | Pat Nolan (2004a), “Study Shows “Neighborliness” Reduces Crime,” Justice Fellowship. |

| 8 | Pat Nolan (2004b), “Two New Laws Provide Important Justice Reform,” Justice Fellowship. |

| 9 | Colson, “God Behind Bars.”, 34. |

| 10 | Colson, “God Behind Bars.”, 29; Pulliam (1987); Van Ness. |

| 11 | For a more detailed description and analysis of evangelical prison organizing, see Smith (2008). |

| 12 | Abraham (2007). This is not to argue that these statistics are accurate but just to explain the facts about slavery as they are articulated in evangelical magazines. |

| 13 | Tracking the Rise of U.S. Slave Traffic (2011), Reject Apathy, no. 1. |

| 14 | Haugen (2007). For a book length narrative of Haugen’s work, see (Haugen 2005). |

| 15 | Haugen, Terrify No More., 38 |

| 16 | Haugen, Terrify No More., 85. For similar pro-law enforcement approach, see Harris (2011). For an account of how the court system impacts the poor in the U.S., see Bach (2009). |

| 17 | Here, I am signifying what I term a people of color movement within evangelicalism that is not simply identity-based but signifies a commitment to an intersectional theological and political engagement across sites of racialization and oppression. This people of color-centered evangelicalism emerges out of and overlaps with Black evangelicalism, Latino/Hispanic evangelicalism, Indigenous evangelicalism, and Asian American evangelicalism without being reducible to them. Certainly, there are many evangelicals of color who do not have such theological or political commitments. Yet, a people of color centered evangelicalism would not exist without work of more conservative evangelicals of color who might not identify with this movement done in organizations like the National Black Evangelical Association, Chief, the National Hispanic Leadership Conference, and many others, as well as work done through independent ministries and racially or ethnically based denominations and churches. |

| 18 | Smith, Native Americans, op cit. |

| 19 | Quotations without reference are from events the writer attended and witnessed. |

| 20 | Gilliard., 191 |

| 21 | Ibid., 189 |

| 22 | Talbert Swan, @talbertswan—Twitter. 2:05 P.M., March 6, 2019. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | For a helpful clearinghouse on transformative justice, see https://transformharm.org/. For a toolkit on community accountability, see http://www.creative-interventions.org/tools/toolkit/ (accessed on 1 August 2022). |

| 25 | Plenary speech, Justice Conference, Chicago, June 6, 2015. |

References

- Abraham, Priya. 2006. The Abolitionist. World 21: 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, Priya. 2007. Let My People Go! World 22: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, Deann. 2007. Free at Last. Christianity Today 51: 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Connie. n.d. Fighting against Human Trafficking on the Abolitionist Plunge. InterVarsity. Available online: http://up.intervarsity.org/content/fighting-against-human-trafficking-abolitionist-plunge (accessed on 1 August 2022.).

- Bach, Amy. 2009. Ordinary Injustice: How America Holds Court. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer, Randall Herbert. 2021. Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beaty, Katelyn. 2011. Portland’s Quiet Abolitionist. Christianity Today 55: 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beutin, Lyndsey P. 2017. Black Suffering for/from Anti-trafficking Advocacy. Anti-Trafficking Review. 9. Available online: https://www.antitraffickingreview.org/index.php/atrjournal/article/view/261/245 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Blunt, Sheryl Henderson. 2007. The Devil’s Yoke. Christianity Today 51: 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Billy. 1997. More Than Jailhouse Religion. Charisma 23: 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Colson, Charles. 1977. Who Will Help Penitents and Penitentiaries? Eternity 28: 12–17, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Colson, Charles. 1980. Prison Reform: Your Obligation as a Believer. Christian Life 41: 23–24, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Colson, Charles. 1985. God Behind Bars. Christian Life 47: 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Angela. 2003. Are Prisons Obsolete. New York: Seven Stories Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Angela Y. 2011. Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and Torture. New York: Seven Stories Press. [Google Scholar]

- Downen, Robert, Lise Olsen, and John Tedesco. 2019. Abuse of Faith. Houston Chronicle. February 10. Available online: https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/investigations/article/Southern-Baptist-sexual-abuse-spreads-as-leaders-13588038.php (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Eng, David, Judith Halberstam, and Jose Esteban Munoz. 2005. Introduction: What’s Queer About Queer Studies. Social Text 23: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, Cheryl. 1982. What Hope for America’s Prisons. Christian Herald 105: 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliard, Dominique DuBois. 2018. Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice That Restores. Westmont: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2018. Abolition Geography and the Problem of Innocence. Tabula Rasa 28: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, Lee. 1993. The Fall of Prison. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Alisa. 2011. Trafficking Cops. World 26: 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Gary. 2005. Terrify No More. Nashville: W Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Gary. 2007. On a Justice Mission. Christianity Today 51: 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heltzel, Peter Goodwin. 2009. Jesus and Justice: Evangelicals, Race, and American Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. 1998. Shielded from Justice. New York: Human Rights Watch. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell, Dawn Herzog. 2007. Red Light Rescue. Christianity Today 51: 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Justice Fellowship. 2000. Jubilee Extra, 1–6, no. February: 1–3.

- Justice, Jessilyn. 2016. Setting the Sex-Trafficked Captives Free. Charisma 41: 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kempadoo, Kamala. 2005. Victims and Agents of Crime: The New Crusade Against Trafficking. In Global Lockdown. Edited by Julia Sudbury. New York: Routledge, pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, Manny. 1999. No Prisons in Heaven. New Man 8: 74. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Emily McFarlan. 2018. How Evangelicals Teamed up with the White House on Prison Reform. Religious News Service, May 25. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Timothy C. 2014. Why We’re Losing the War on Poverty. Christianity Today 58: 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, Pat. 2004a. Study Shows Neighborliness Reduces Crime. Justice Fellowship. January 14, 2004 Email Newsletter. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, Pat. 2004b. Two New Laws Provide Important Justice Reform. Justice Fellowship. October 21, 2004 Email Newsletter. [Google Scholar]

- Olasky, Marvin. 2010. The Life of a Slave. World 25: 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshimi, and Ejeris Dixon, eds. 2020. Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement. Chico: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Charles. 2009. America’s Ugliest Crime. Charisma 35: 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Clive. 2007. The Day Slavery Ended. Charisma 32: 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam, Russ. 1987. A Better Idea Than Prison. Christian Herald 110: 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rah, Soong-Chan. 2015. Soong-Chan Rah Says Black Lives Matter Because of What Experienced. National Black Evangelical Association. Available online: http://www.the-nbea.org/articles/soong-chan-rah-says-black-lives-matter-because-of-what-experienced/ (accessed on 13 December 2016).

- Ritchie, Andrea. 2006. Law Enforcement Violence against Women of Color. In The Color of Violence: Violence against Women of Color. Edited by Incite. Cambridge: South End Press, pp. 138–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, Andrea J. 2017. Invisible No More: Police Violence against Black Women and Women of Color. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Ellen M., and Ellen MacGilvra Rosenberg. 1989. The Southern Baptists: A Subculture in Transition. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, Vincenzo. 2011. An abolitionist view of restorative justice. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 39: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scimone, Diana. 2009. Stop Child Slavery Now. Charisma 35: 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Smarto, Don, ed. 1993. Setting the Captives Free. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Andrea. 2008. Native Americans and the Christian Right: The Gendered Politics of Unlikely Alliances. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Andrea. 2014. Humanity through Work. Borderlands 13: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Andrea. 2019. Unreconciled: From Racial Reconciliation to Racial Justice in Christian Evangelicalism. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tracking the Rise of U.S. Slave Traffic. 2011. Reject Apathy, 1, 8.

- Van Ness, Daniel. 1985. The Crisis of Crowded Prisons. Eternity 36: 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Kristian. 2007. Our Enemies in Blue. Cambridge: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young Women’s Education Project. 2009. Girls Do What They Have to Do to Survive: Illuminating Methods Used by Girls in the Sex Trade and Street Economy to Fight Back and Heal. Chicago: Young Women’s Education Project. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr, Howard. 2015. Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times. Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).