The Logical Problem of the Trinity: A New Solution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| (1) (Monarchical Trinitarianism) | (a) There are three relationally distinct persons within the Trinity: the Father, the Son and the Spirit, each of whom shares one divine nature, and thus are each equally termed ‘God’ (in the predicative sense). (b) The one ‘God’ (in the nominal sense) is numerically identical to one of the entities: the Father, who is the sole ultimate source of the Son and the Spirit. |

| Athanasian Creed (AC) | Identity Reading (IR)9 |

| 1. The Father is God. 2. The Son is God. 3. The Spirit is God. 4. The Father is not the Son. 5. The Father is not the Spirit. 6. The Spirit is not the Son. 7. There is exactly one God. | 1*. The Father = God. 2*. The Son = God. 3.* The Spirit = God. 4*. The Father ≠ the Son. 5*. The Father ≠ the Spirit. 6*. The Spirit ≠ the Son. 7*. There is exactly one God. |

| Athanasian Creed (AC) | Monarchical Reading1 (MR1) |

| 1. The Father is God. 2. The Son is God. 3. The Spirit is God. 4. The Father is not the Son. 5. The Father is not the Spirit. 6. The Spirit is not the Son. 7. There is exactly one God. | 1*. The Father ins Divinity (Universal). 2*. The Son ins Divinity (Universal). 3*. The Spirit ins Divinity (Universal). 4*. The Father ≠ the Son. 5*. The Father ≠ the Spirit. 6*. The Spirit ≠ the Son. 7*. There is exactly one God, the Father. |

When my daughters, Mary, Beatrice, Edith, and Agnes, each instantiate the universal, Humanity, and each has proper characteristics such that we don’t confuse them, what we have here are four humans, not a single human.

God is non-composite: God has no parts, is incapable of division, and is not composed of a number of elements. In other words, God is simple… Thus, in pro-Nicene texts, the primary function of discussing God’s simplicity is to set the conditions for all talk of God as Trinity and of the relations between the divine ‘persons’.

2. Constructing Monarchical Aspectivalism: Stage One

| Monarchical Reading1 (MR1) | Monarchical Reading2 (MR2) |

| 1*–3*. Divinity = Universal | 1’–3’. Divinity = Powerful Trope |

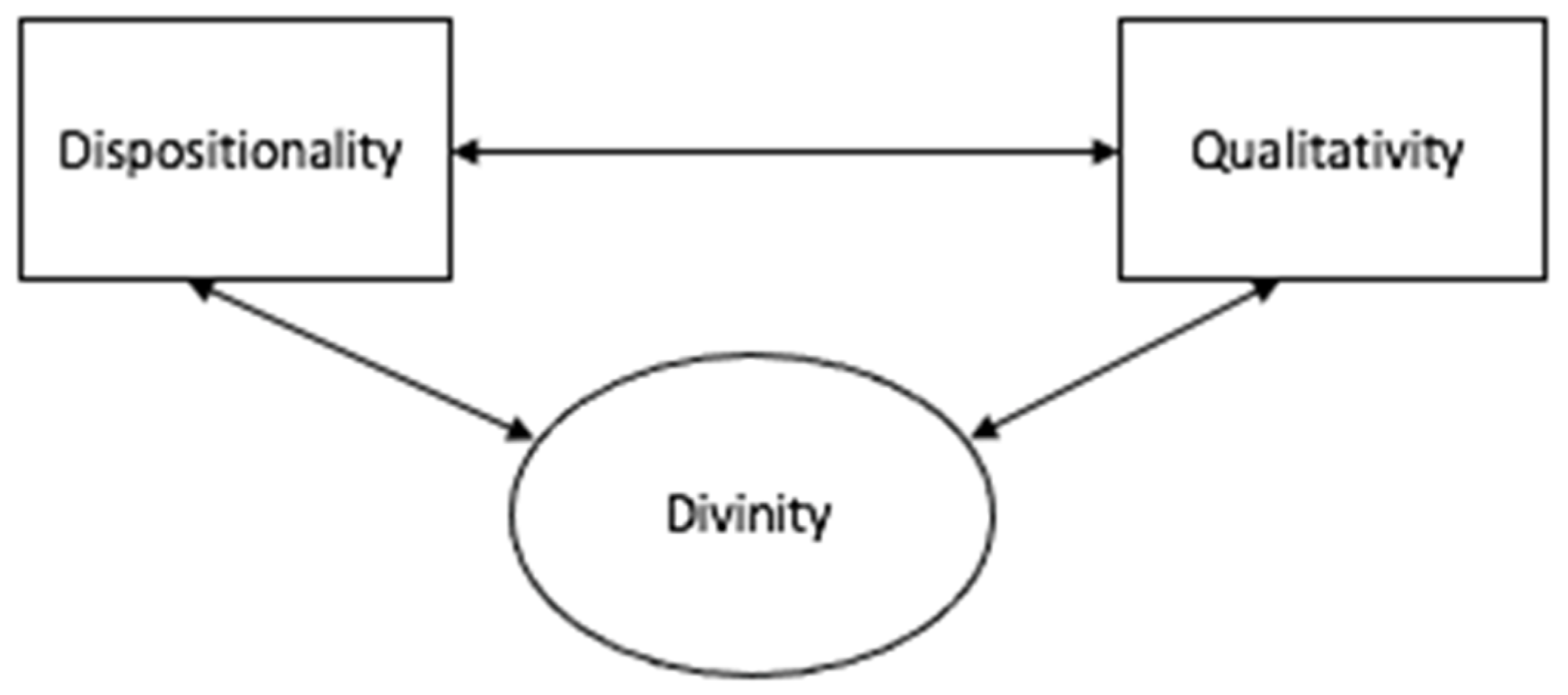

2.1. The Nature of a Powerful Trope

| (2) | (Powerful Trope): An abstract particular nature of a modifier or modular kind that can be considered as a disposition or as a quality. |

Abstract here contrasts with concrete: a concrete entity is the totality of the being to be found where our colours, or temperatures or solidities are. The pea is concrete; it monopolises its location. All the qualities to be found where the pea is are qualities of that pea. But the pea’s quality instances are not themselves so exclusive. Each of them shares its place with many others.17

| (3) (Leibniz’s Law) | (a) Identity of Indiscernibles: ∀x∀y(x = y ↔ (φ(x) ↔ φ(y)). (b) Indiscernibility of Identicals: ∀φ(φ(x) ↔ φ(y) → x = y). |

Whereas tropes are particular properties—things like this redness, this triangularity, this pallor, tropers are thin individuals—things like this individual red thing, this individual triangular thing, and this individual pale thing. The claim would be that familiar objects are bundles of compresent tropers. So the view would again dispense with properties and insist that the ultimate constituents of familiar particulars are intrinsically characterised or natured, but would construe those constituents as particulars rather than universals. Such intrinsically characterised particulars would be the ultimate or underived sources of character: a familiar particular would be, say, pale because it has a pale troper as a constituent.

According to a majority of the trope theorists, tropes have an important role to play in causation. It is, after all, not the whole stove that burns you, it is its temperature that does the damage. And it is not any temperature, nor temperature in general, which leaves a red mark. That mark is left by the particular temperature had by this particular stove now or, in other words, it is left by the stove’s temperature-trope.

2.2. Divinity as a Powerful Trope

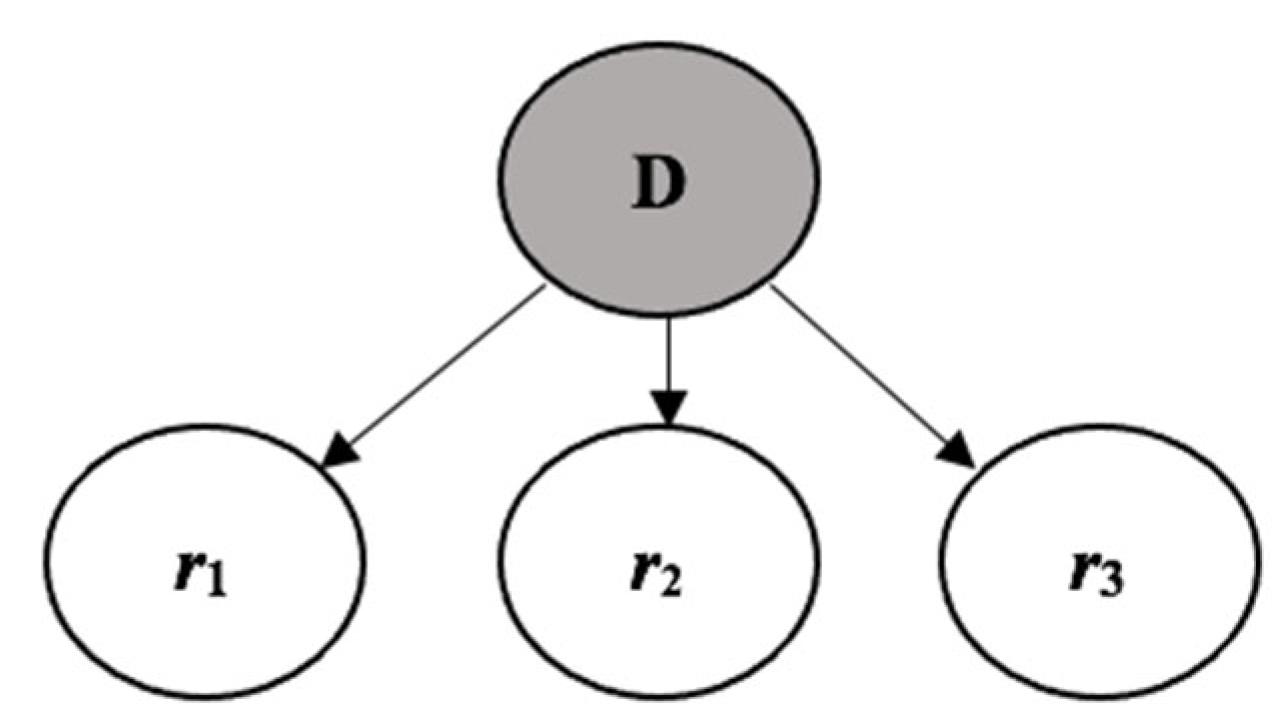

3. Constructing Monarchical Aspectivalism: Stage Two

| Monarchical Reading1 (MR1) | Monarchical Reading2 (MR2) |

| 1*. The Father ins Divinity (Universal). 2*. The Son ins Divinity (Universal). 3*. The Spirit ins Divinity (Universal). | 1’. Father-Aspect = Divinity (Trope). 2’. Son-Aspect = Divinity (Trope). 3’. Spirit-Aspect = Divinity (Trope). |

3.1. The Nature of Multiple Location and Aspects

| (4) | (Aspectival Multiple Location): A particular object having more than one (disjoint) exact location and bearing different aspects at those locations. |

| (5) | (Exact Location): An entity x is exactly located at a region y if and only if x has (or has-at-y) exactly the same shape and size as y and stands (or stands-at-y) in all the same spatial or spatiotemporal relations to other entities as does y (see note 27). |

| (6) | The cube is exactly located at just one cube-shaped region. |

| (7) | The Kuiper Belt is exactly located at a scattered region composed of lots of disjoint asteroid shaped regions. |

| (8) | A sphere is exactly located at some region with a volume equal to 4π/3 multiplied by the radius (of the sphere) cubed. |

| (9) | (Multiple Location) An entity x is multi-located if there are two or more distinct regions that x is exactly located at. |

| The Case of David | The Case of Jane |

| David is an ardent philosophy professor and is also a loving and faithful father of two children, Jacob and Melissa. Now suppose that, firstly, David has an upcoming philosophy conference in which he is the keynote speaker and, due to other work commitments, has not prepared his speech yet. Secondly, suppose that David had previously promised that he would reward his children with a camping trip this upcoming weekend if they achieved A* grades in their A-Level results. And, thirdly, suppose that Jacob and Mellissa have both, in fact, recently achieved A* grades in their A-Level results. | Jane is an ambitious lawyer and a (volunteer) senior staff member of Humanists UK. Now, suppose Jane is on her way to an important meeting at her law firm. However, when she is walking, she observes an assault taking place in an alley. An inner struggle now ensues between her conscience, to stop and call for help, and her career ambitions, which tell her she cannot miss this meeting. |

| (10) (Aspect) |

|

| The Case of a Multilocated Object |

| There is a particular object that is located at two (disjoint) spatial regions. As an entity inherits the properties (‘qualities’) and relations of the specific region that it is exactly located at, this particular object bears different properties (‘qualities’) and relations at each of the specific spatial regions that it is exactly located at. |

| (11) | Oy[y@r1] is S |

| (12) | Oy[y@r2] is C |

| (13) | Oy[y@r1] is S |

| (14) | Oy[y@r2] is S |

| (15) | (Oy[y@r1]) = (Oy[y@r2]) → ∀O [((Oy[y@r1]) is F) ↔ ((Oy[y@r2]) is F]. |

| (16) | (Aspect Identity) ∀x(∃z(z = xy[φ(y)]) → x = xy[φ(y)]). Informally: Every aspect is numerically identical with a complete individual x. |

| (17) | Oy[y@r1] = Oy[y@r2] |

| (18) | (Block) ∼(∀x)(F(xy[φ(y)]) → Fx). Informally: It does not follow from the fact that an aspect of a complete individual x is F that x is F. |

| (19) (Indiscernibility) | (II): | ∀x∀y(x = y→(F(x) ↔ F(y)). Informally: For any things x and y, if x is numerically identical with y, then for any quality F, F is had by x if and only if F is had by y |

| (IA): | ∀x∀y(x = y→(∀F)(F(zk[Xk])↔ F(wk[Yk]))) Informally: For any things x and y, if x is numerically identical with y, then, for any property, any aspect numerically identical with x has it if and only if any aspect numerically identical with y has. |

3.2. Divinity as a Multiply Located Aspect Bearer

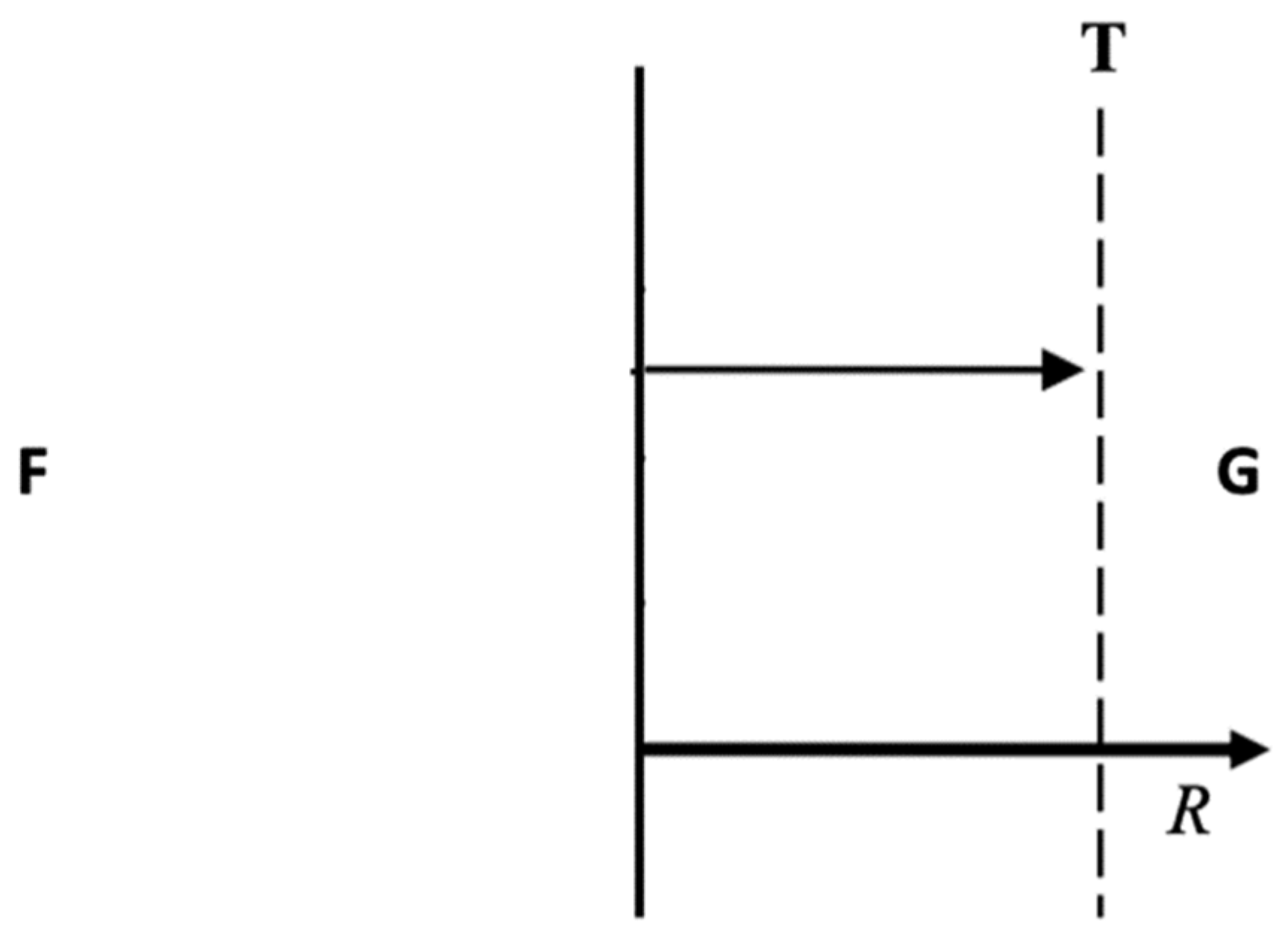

| (20) (Divinity Multiple Location) |

|

| (21) (Divinity-Aspects) |

|

| (22) | Divinityy[y@r1] has the qualities and/or relations of r1. |

| (23) | ~Divinityy[y@r2] has the qualities and/or relations of r1. |

| (24) | ~Divinityy[y@r3] has the qualities and/or relations of r1. |

| (25) | Divinity = Divinityy[y@r1]; Divinityy[y@r2]; Divinityy[y@r3]. |

| (26) | Divinityy[y@r1] = Divinityy[y@r2], |

| (27) | Divinityy[y@r2] = Divinityy[y@r3], |

| (28) | Divinityy[y@r3] = Divinityy[y@r1]. |

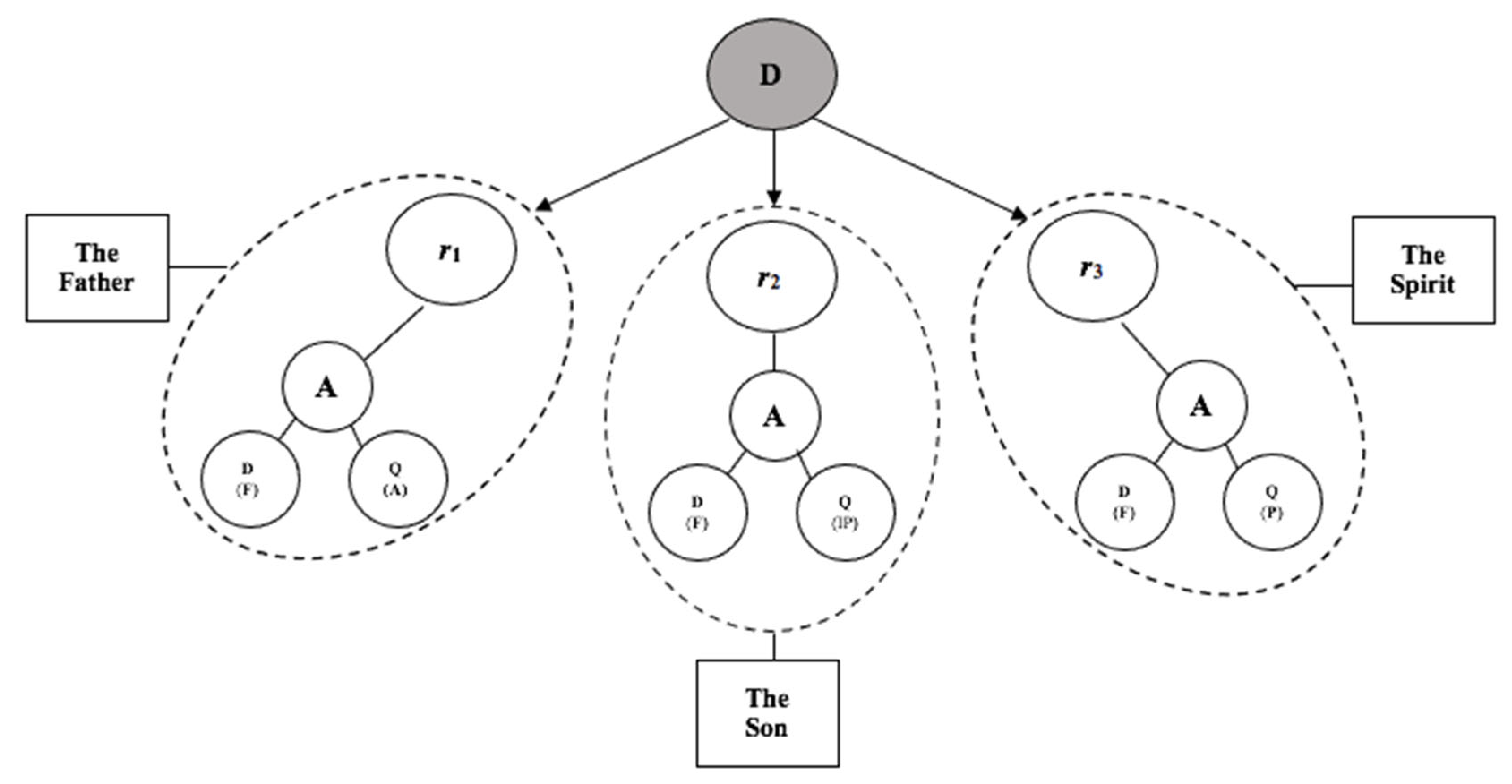

| (29) | The Father = Father-Aspect (i.e., Divinityy[y@r1]). |

| (30) | The Son = Son-Aspect (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]). |

| (31) | The Spirit = Spirit-Aspect (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]). |

4. Constructing Monarchical Aspectivalism: Stage Three

| Monarchical Reading1 (MR1) | Monarchical Reading2 (MR2) |

| 4*. The Father ≠ the Son. 5*. The Father ≠ the Spirit. 6*. The Spirit ≠ the Son. | 4’. Father-Aspect ≠ Son-Aspect. 5’. Father-Aspect ≠ Spirit-Aspect. 6’. Spirit-Aspect ≠ Son-Aspect. |

4.1. Personhood and Relations

| (32) | (Relational Personhood): A multiply located particular object that has (region-specific) aspects, each of whom has a first-person perspective and stands in a non-symmetric relation that enables it to fulfil certain onto-thematic roles. |

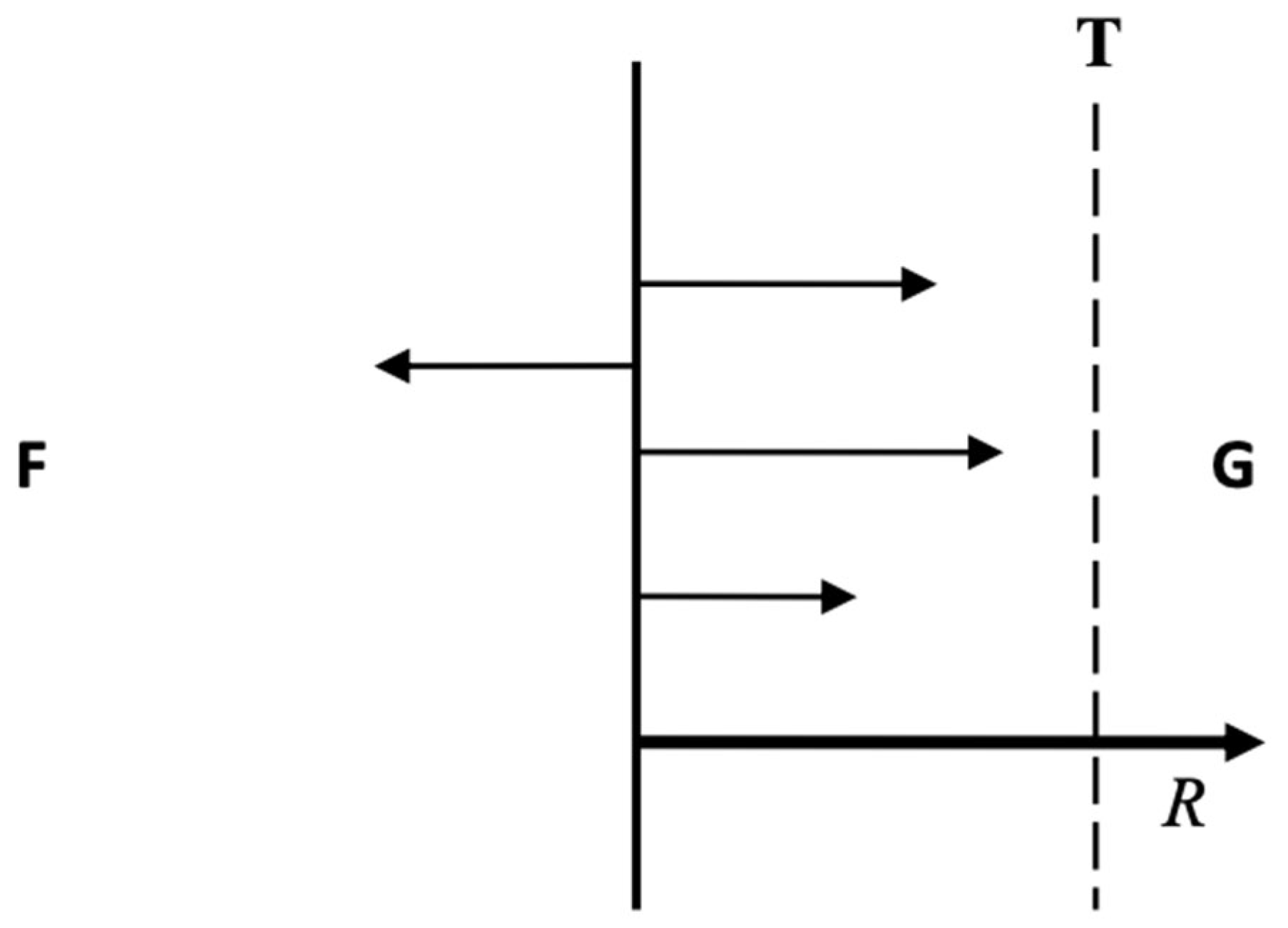

| (33) (Relations) |

|

| (34) | Dante loves Beatrice. |

4.2. Divinity as Onto-Thematic Persons

| (35) | The Father (Divinityy[y@r1]) is a person (i.e., has a robust first-person perspective). |

| (36) | The Son (Divinityy[y@r2]) is a person (i.e., has a robust first-person perspective). |

| (37) | The Spirit (Divinityy[y@ r3]) is a person (i.e., has a robust first-person perspective). |

| (38) | The Father generates the Son. |

| (39) | The Father generates the Spirit through the Son. |

| (40) | The Father (Divinityy[y@r1]) is a person (i.e., has a robust first-person perspective) and fulfils the O-Role of *agent*. |

| (41) | The Son (Divinityy[y@r2]) is a person (i.e., has a robust first-person perspective) and fulfils the O-Roles of *patient* and *instrument*. |

| (42) | The Spirit (Divinityy[y@ r3]) is a person (i.e., has a robust first-person perspective) and fulfils the O-Role of *patient*. |

| (43) (Divinity-Aspects (ii)) |

|

5. Constructing Monarchical Aspectivalism: Stage Four

| Monarchical Reading1 (MR1) | Monarchical Reading2 (MR2) |

| 7*. There is exactly one God, the Father. | 7’. There is exactly one fundamental Divinity-Aspect, the Father-Aspect. |

5.1. The Nature of Fundamentality

| (44) | (Fundamentality) An entity is fundamental if it is independent (i.e., unbuilt/ungrounded) and complete (i.e., the builder/ground of everything else). |

| (45) | (Independence) x is independent if nothing builds x (Bennett 2017). |

| (46) | (Completeness) The set of the xxs is (or the xxs plurally are, or a non-set-like x is) complete at a world w just in case its members build (…) everything else at w (Bennett 2017, p. 109). |

| (47) | (Grounding) An asymmetric, necessitating dependence relation that links the more fundamental entities to the less fundamental entities, and is best conceptualised as a type of causation: metaphysical causation. |

| (48) | (FundamentalG): x is fundamental if x is independentG and completeG. |

| (49) | (IndependenceG): x is independent if nothing grounds x. |

| (50) | (CompletenessG): The set of the xxs is (or the xxs plurally are, or a non-set-like x is) complete at a world w just in case its members ground everything else at w. |

5.2. ‘God’ as the Fundamental Aspect

| (51) (Monarchical Aspectivalism) |

|

| Athanasian Creed (AC) | Monarchical Reading2 (MR2) |

| 1. The Father is God 2. The Son is God 3. The Spirit is God 4. The Father is not the Son 5. The Father is not the Spirit 6. The Spirit is not the Son 7. There is exactly one God. | 1’. Father-Aspect = Divinity (Trope). 2’. Son-Aspect = Divinity (Trope). 3’. Spirit-Aspect = Divinity (Trope). 4’. Father-Aspect ≠ Son-Aspect 5’. Father-Aspect ≠ Spirit-Aspect 6’. Spirit-Aspect ≠ Son-Aspect 7’. There is exactly one fundamental Divinity-Aspect, the Father-Aspect. |

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The veracity of the filioque is assumed in this conception of the Trinity. |

| 2 | By a model, following Alvin Plantinga (2000), I mean a collection of propositions that shows how it could be so that another collection of target propositions is true or actual. In light of this, certain models of the doctrine of the Trinity seek to provide a possible means in which the doctrine could, in fact, be true. |

| 3 | The Latin Trajectory includes Latin-speaking theologians such as Hilary of Poitiers, Ambrose of Milan and Augustine of Hippo. However, the origin of the Athanasian Creed post-dates the writing of these authors, yet its language and concepts are firmly grounded within the Latin (Augustinian) tradition. For a detailed exposition of the historical development of the Athanasian Creed within the trajectory, see (Kelly 1964). |

| 4 | Cartwright appears to be the first individual to have introduced into the literature what has come to be known as the ‘Logical Problem of the Trinity’. There are other terms used in reference to this problem, such as the ‘Inconsistent Septad Problem’ and the ‘Fundamental Problem’. However, due to the ambiguity of some of these terms, I will continue to refer to this problem through the more generic term of the ‘Logical Problem of the Trinity’ (LPT). More on the nature of this problem below. |

| 5 | Swinburne’s ‘social Trinitarianism’ account of the Trinity provides a ‘three-self’ answer to the Logical Problem of the Trinity. |

| 6 | Leftow’s ‘Latin Trinitarianism’ account of the Trinity provides a ‘one-self’ answer to the Logical Problem of the Trinity. |

| 7 | van Inwagen’s ‘Relative Identity’ account of the Trinity provides an answer to the Logical Problem of the Trinity by questioning the ‘absoluteness’ of identity—and proposing a relativisation of identity. |

| 8 | For further clarity, (IR) can be translated into predicate logic and reduced to three premises as follows (where f stands for the Father, s for the Son, h for the Spirit and G for God). |

| 9 | 1*. Gf & Gs & Gh. 2*. f ≠ s & f ≠ h & s ≠ h. 3*. ∃x (Gx & ∀y(Gy → x = y). |

| 10 | (Sijuwade 2021) is the first to propose this type of account within a Monarchical Trinitarian context. |

| 11 | For a helpful explanation of this issue within a detailed historical context—namely that of the notion of a universal within the Cappadocians and the tri-theistic theology of John Philoponus, see (Erismann 2008). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | We can further understand the term to mean that each of the persons is extensively equal such that they possess numerically the same essential property of Divinity. For a further explanation of this construal of the notion of the homoousion, see: (Mullins 2020, p. 2). |

| 14 | For a response to this issue within an instantiation-based framework, see (Sijuwade 2021). |

| 15 | Which has been done frequently within the analytic theology literature to deal with the distinction issue by taking the ‘is’ of (1)–(3) as one of predication rather than that of identity. For this, see (Swinburne 1994), (Wierenga 2004), (Hasker 2013) and (Davis 2006). |

| 16 | With the oneness issue now being held at bay by one utilising a Monarchical framework. |

| 17 | This use of the term ‘abstract’ (and concrete) also contrasts with the prevalent understanding of the term, which sees an abstract entity as something that has, for concrete entities, or lacks, for abstract entities, spatiotemporal location or causal efficacy (Fisher 2020). Thus, as Campbell (1990, p. 3) further writes, focusing on abstract entities:

|

| 18 | Given the complexity and space required to unpack Langton and Lewis’ account, the brief explanation here will be based on Alvarado’s interpretation of it. |

| 19 | I leave the account of analogy here undefined. Furthermore, I do not assume here that the ‘properties’ borne by this particular have to be properties in an ‘ontologically robust sense’—as other entities could be borne by this particular, such as ‘sub-aspects’, which are introduced below. |

| 20 | Further philosophers who have defended and developed the Powerful Qualities view are: Alexander Carruth (2015), J. Henry Taylor (2013, 2017, 2019), William Jaworski (2016) and Joaquim Giannotti (2019), Galen Strawson (2008), Jonathan D. Jacobs (2011), Kristina Engelhard (2010) and Rognvaldur Ingthorsson (2013). |

| 21 | Character language will be favoured over that of nature language. |

| 22 | An assumption is made here concerning a powerful trope being multi-track, rather than single-track. |

| 23 | We can assume the notion of intrinsicality noted above. |

| 24 | In contradistinction to this, one could hold (as some philosophers do) to the conception of the dispositionality of a trope as ‘single-track’—which is that of a given trope only having one manifestation type. |

| 25 | Construing qualitativeness in this specific way, rather than as a term that is synonymous with the term ‘non-dispositional’—as it regularly has been done—enables the proponents of the Powerful Qualities view to ward off the charge of inconsistency that has been raised by David Armstrong (1997) and Stephen Baker (2013), amongst others. For an extended and informative examination of the notion of qualitativeness within the literature, see (Taylor 2019). |

| 26 | This example is adapted from (Taylor 2017). |

| 27 | The proponents of the Powerful Qualities view do not use the term ‘traits’ to refer to the dispositionality and qualitativeness of a trope. However, I feel that it is less metaphysically loaded than the terms ‘parts’ or ‘sides’, and thus I will continue to utilise this term here. |

| 28 | This distinction is usually drawn by the proponents of the positions of Dispositionalism—all properties are purely dispositional, Categoricalism—all properties are solely non-dispositional, and a ‘mixed view’—some properties are solely dispositional, whilst other properties are held to be solely categorical/qualitative. For a defense of Dispositionalism, see Sydney Shoemaker (1980) and Alexander Bird (2007). For a defense of Categoricalism, see David Lewis (1983) and David Armstrong (1997). Additionally, for a defense of a mixed view, see George Molnar (2003) and Brian Ellis (2001). |

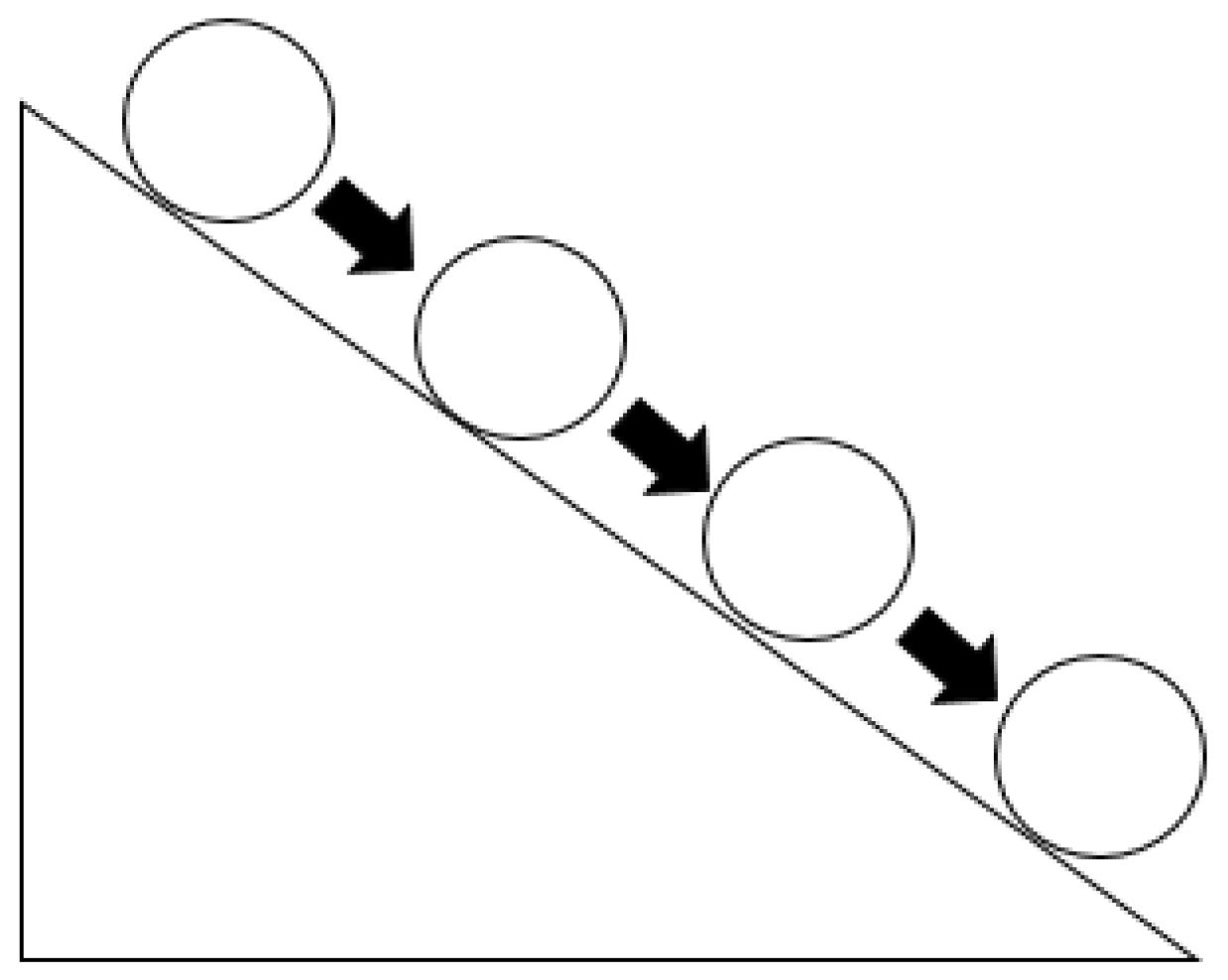

| 29 | This can be termed the canonical conception of the Powerful Qualities view, given that this specific version is the one proposed by the formulators of the Powerful Qualities view: Martin and Heil. However, there are other versions of the Powerful Qualities view, such as that provided by Giannotti (2019) and Taylor (2013), that do not adhere to a ‘surprising identity’ between a property’s dispositionality and its qualitativity. |

| 30 | Another example of a general case of a powerful quality is that of the mass or charge of a particle: we can consider a particle quantitatively when we consider it to have a certain mass or for it to have a certain quantity of charge that can be measured in Coulombs—with each of these being ‘here and now’ features that a particle has. However, at the same time, we can consider a particle dispositionally when we regard it to have a disposition to generate gravitational force or a disposition to produce an electromagnetic force. In this example, it is in virtue of a particle having a certain mass or quantity of charge (both qualities of this particle) that it has the dispositions that it does. |

| 31 | An objection that can be faced here—as was raised by an anonymous reviewer—is that of one getting the physics wrong with this example. That is, it seems to be the case that whether the ball is disposed to roll down the slope depends on much more than the shape of the ball. For example. if the ball and slope are in zero gravity, the ball is not disposed to roll down the slope. If the ball and slope are appropriately magnetised, then the ball is not disposed to roll down the slope. If the ball is made from a super-adhesive substance, then the ball is not disposed to roll down the slope. If—perhaps per impossible—the ball is massless, then the ball is not disposed to roll down the slope. Thus, it seems to be a mistake in taking the ability of a ball to roll down a slope to be a paradigm example of a powerful quality. However, in response to this, one can—in following Heil (2012, p. 129)—understand that the case of a ball rolling down a slope to be a mutual manifestation of dispositions of the ball/slope and the dispositions present in the environment. Hence, if the ball and the slope are in zero gravity, or are magnetised, or the ball is massless, or made from a super-adhesive substance, then these additional things simply inhibit this manifestation. However, this inhibition is simply a matter of the dispositional system that includes dispositions of the magnetic field, the super-adhesive substance, and the absence of gravity and mass, yielding a different sort of mutual manifestation—namely, the manifestation of the ball to remain still on the slope. Hence, in these cases, it is a matter of certain dispositions of the ball and the slope manifesting themselves with various other mutual manifestation partners that results in a different effect than if the ball and slope were manifesting their dispositions without the interference of these other dispositional partners. For more on this issue, see (Heil 2012, pp. 126–30). |

| 32 | |

| 33 | More on the nature of location below. |

| 34 | We can also say that Divinity is in some sense a personal agent, as to exercise its maximal power/omnipotence, it must be an entity that has a rich form of consciousness that enables it to perform a range of actions that are solely limited by logic. Thus, taking Divinity to be a trope does not rob it of this personhood, given that it is a trope of a modular kind. More on the notion of personhood below. |

| 35 | Though in the Father’s ‘grounding’ of the Son and the Spirit—as will be detailed below—Divinity’s power will not move from inactivity to activity but, instead, would always be manifested, given that its grounding act will be a necessary action that stems from Divinity’s perfect goodness. More on this below. |

| 36 | As Christian Theism is being assumed here, Divinity is taken to be a ‘part’ of the Trinity and thus is borne by, and works through, the Trinity (i.e., in cooperation with the Son and the Spirit). This conception of the Trinity assumes the notion of the ‘monarchy of the Father’—the teaching that Divinity is numerically identical to the Father alone—which is contrary to the common position that holds to Divinity being numerically identical to the Trinity. As noted in the main text, the difference between these positions is more than a linguistic issue as proponents of the monarchy of the Father will take the existence of the Father to be the basis for Christian Theism being monotheistic—as there is ‘one Father’, there is ‘one Divinity’—whereas proponents of the common position would take the existence of the Trinity to be the basis for Christian Theism being monotheistic—the ‘unified collective’ (i.e., the Trinity) is the ‘one Divinity’. |

| 37 | With the temporal relativisation being kept implicit. |

| 38 | Aspects are also further developed by Baxter in the different context of clarifying the instantiation relation between a particular and a universal. For this, see (Baxter 2001). |

| 39 | As Baxter writes, ‘aspects should not be confused with Casteneda’s guises (1975), or Fine’s qua-objects (1982), or other such attenuated entities’ (Baxter 2018b, p. 103). |

| 40 | In reference to aspects, there will be an interchanging of the term ‘qualities’ with the term ‘properties’. However, the former term is preferable over the latter term, as it helps us to ward off mistaking the entities that are born by aspects needing always to be further entities that are ontologically different from them—as aspects can bear qualitied ‘sub-aspects’. |

| 41 | More on this below. |

| 42 | In motivating aspects, Baxter believes that the clearest cases, as in the example in the main text, are those of the internal psychological conflict of a person. However, self-differing, according to Baxter, is not only confined to these psychological conflicts but, as Baxter writes, cases ‘of being torn give us the experiences by which we know that there are numerically identical, qualitatively differing aspects. We feel them’ (Baxter 2016, p. 99). Self-differing is present in any case where an entity has a property and lacks it at the same time, in the virtue of playing different roles (Baxter 1999). |

| 43 | One can ask the question of if aspects can vary over time? I believe that they can, and do, given that the paradigm examples of aspects—as noted above—are had in self-differing cases. Given the modal variance of aspects, how could they be numerically identical to their bearers? I believe that one way in which one can hold to the numerical identity of an aspect with their bearer, despite their modal variance, is by assuming an account of ‘temporary identity’ (or ‘occasional identity’)—such as that found in the work of André Gallois (1998), and which has been endorsed by Baxter (2018c)—in which something identical with itself at one time is at that time distinct from itself at another. That is, any case of identity is identity at a time, which, following (Baxter 2018c, p. 767) allows one to formalize temporary identity as follows:

A good reason that motivates adopting this view of identity (as ‘temporary’ or ‘occasional’) is explained well by McDaniel (2014, p. 16) and thus deserves to be quoted in full:

Now, in adopting this view of identity, one is indeed required to make further restrictions to Leibniz’s Law (i.e., there being a temporal analogue of Leibniz’s Law)—which might indeed have some pushback. Nevertheless, for good reasons to make these further restrictions (and for a method on how to do this), see: (Baxter 2018c, pp. 769–79) and (McDaniel 2014, pp. 17–19). |

| 44 | Thus, the abstractness and particularity of an aspect fit neatly with that of a trope’s abstractness and particularity that was noted above. |

| 45 | Region-specific in the sense that an aspect borne by a particular object in the specific region in which it is located is not borne in any other region in which that object is also exactly located at. |

| 46 | As noted by Ted Sider (2007, p. 57), ‘Defenders of strong composition as identity must accept this version of Leibniz’s Law; to deny it would arouse suspicion that their use of ‘is identical to’ does not really express identity’. Likewise, as noted by Einar Bohn (2021, p. 4597, square parenthesis added), [Leibniz’s Law] is simply conceptually rock bottom of what I mean by identity. So, violating it amounts to, at best, changing the subject’. Furthermore, one might still comment that it is inconceivable to define numerical identity without utilising Leibniz’s Law, and thus Baxter’s approach should be rejected. However, Baxter (2018a, p. 908) notes that he is not defining identity; but instead, is taking it as primitive—for one to be numerically identical is to be one single individual and to be numerically distinct is simply to be two single individuals (Baxter 2018a). It is the connection with cardinality, rather than qualitative sameness, which is essential to numerical identity. |

| 47 | A single individual differs from itself by having two or more aspects. An important question that can be raised here is if the two-ness of the aspect entails a numerical distinctness between the aspects? Baxter (2018a, p. 908) believes not, as counting aspects is only a loose way of counting individuals—aspects possessed by a single individual are counted as more than one in virtue of their qualitative difference; however, this does not entail a numerical difference that would result in the individual being more than one individual. More on this below. |

| 48 | Baxter notes that Leibniz’s Law does not entail Indiscernibility of Identical Aspects, given that it could only do this if aspects were included within the domain of quantification for the principle, but as it is not, there is no entailment and the variables thus instead range only over individuals alone (Baxter 2018a). |

| 49 | Baxter (2018a, p. 909) sees Leibniz’s Law as being closely related to the further principle that co-referential terms are substitutable salva veritate. However, he notes that this specific principle concerns only singular reference, and thus the substitution of expressions only refers to single individuals. One would thus need to provide an argument for why it should be generalised to aspects. |

| 50 | An objection that can be raised here concerns the importance of location relations to the current proposal, as one could argue that, even if the proposal works, it is not applicable within a theological context, given that the Trinitarian persons are usually taken to not stand in any location relation. Or, at least, the Trinitarian persons stand in a location relation in a derivative sense, such as that found within the accounts of divine omnipresence featured in: (Swinburne 2016) and (Wierenga 2010). However, a possible way to deal with this issue is to adopt Hud Hudson’s (2009) and Alexander Pruss’ (2013) ubiquitous entension account of location, which takes Divinity to stand in location relations in a fundamental sense—by entending the region in which it is located. Additionally, thus, within this account, Divinity does indeed have an exact location in the manner that the proposal requires it to have—it entends three specific spatial regions. For a further discussion and historical modification of this position in light of the ‘materialist’ implications of the account, see (Inman 2017). However, another issue that one could raise is that, given the further assumption that Divinity entends the entirety of space (as it is omnipresent), it is hard to see how the Trinitarian persons could have distinct regions of space in which they are located within—that is, they, too, will entend the entirety of space. Additionally, thus, to suggest otherwise would be to suggest that the three persons are subject to arbitrary limitations. However, one can respond to this issue by questioning the assumption that Divinity entends the entirety of space. Rather one can assume the derivative view of omnipresence such that Divinity is related to the entirety of space in a derivative sense and thus does not entend it. More specifically, this derivative form of omnipresence would take ‘Being present at’ relation in a non-basic sense, which means, as Georg Gasser (2019, p. 45) ‘that any locative facts about an object’s presence in a region in space are constituted by facts about another entity (or entities) bearing a ‘present at’-relation in a basic sense and to which the object in question stands in a particular relation’. Being present at thus means being present at in a derivative sense, and thus Divinity, being omnipresent, would be present to all of space in this specific sense of the terms. Hence, Divinity is to be taken to be an entity that only entends the three disjoint spatial regions of r1, r2 and r3—and is then, from these regions, related to the rest of the spatial regions in a derivative sense. |

| 51 | |

| 52 | More on this issue below. |

| 53 | Thus, human infants are persons in virtue of them having a rudimentary first-person perspective and developing, over time, a robust first-person perspective as they mature and learn a language (Baker 2013). |

| 54 | Heil (2009, 2012) himself affirms Moderate Realism. However, for a further explanation of the role played by Hyper-Realism within the field of contemporary metaphysics, see (Macbride 2020). |

| 55 | Positionalism is a specific conception of the nature of relations which takes there to be certain ‘positions’ in a relation that are ‘occupied’ by the relata. For a further explanation of positionalism, see (Macbride 2020, §4). Furthermore, Mario Paoletti (2016) has also developed Orilia’s theory by providing a reformulation of the nature of O-Roles through a utilisation of E.J. Lowe’s and John Heil’s notion of a mode. Paoletti (2019) then applied this reformulated theory of O-Roles to certain logical issues concerning the Trinity. Despite the plausibility of Paloletti’s proposal, this development cannot affirm the numerical identity (yet qualitative distinctiveness) of the members of the Trinity—as a mode is not identical to its bearer— and thus, given this, I will stick with Orilia’s position that O-Roles are simply sui generis properties (which, however, provides ‘conceptual room’ to conceive of them as aspects within a theistic context). |

| 56 | I leave it open here whether the argument for the distinctiveness of the first-person perspectives had by the members of the Trinity that has been put forward here is sufficient to ground the distinctiveness of a robust first-person perspective or only a rudimentary one. If not, then one can modify (32)–(34) by taking them to bear rudimentary rather than robust first-person perspectives—which is sufficient for them being persons. |

| 57 | The ‘in virtue’ clause here indicates that this is a metaphysical grounding relation. More on the nature of grounding below. |

| 58 | For the reasons for privileging independence over completeness, see (Bennett 2017, pp. 122–23). |

| 59 | For a historical explanation of these individuals’ roles in developing the notion of ground, see (Raven 2020). |

| 60 | For a different, but highly influential conception of ground, that does not take it to be a relation, but a sentential operator that has facts within its purview, see: (Fine 2012). |

| 61 | That grounding is super-internal was first posited by (Bennett 2011, pp. 32–33). Furthermore, grounding’s super-internality is not to be confused with the internality of other relations. As the former type of internality, and not the latter, requires that only one of the relatum exists in order for the relation to hold between the relata. |

| 62 | In following Wilson in taking grounding to be identical to causation—metaphysical causation—we are not taking grounding to be analogous to, but distinct from, causation as Schaffer (2016) does. For the reasons why Schaffer does not make this identification, see (Schaffer 2016, pp. 94–96). Additionally, for a summary of reasons why someone should make this identification, see (Wilson 2018, p. 748). |

| 63 | Wilson (2018) is more instructive than Schaffer (2016) in highlighting the importance of the different ways that the causal sufficiency relation is mediated. Furthermore, Schaffer (2016, p. 57) uses the terms ‘laws of metaphysics’ rather than ‘principles of grounding’, which feature in a later article (Schaffer 2021). We can thus take both of these terms to be synonymous and continue using the latter. |

| 64 | For a further explication of the notion of grounding within a Trinitarian context, see (Sijuwade 2022). |

| 65 | For brevity, the additional clause ‘in that specific world’ will now be an unwritten assumption. |

| 66 | For ease of writing, in this specific constructive stage, the sub-aspects of each of the Divinity-Aspects will be suppressed. |

| 67 | Specifically, the Father would be the sole member of this set. |

| 68 | However, by the Son and the Spirit being ‘derivative’, it does not mean that they are created, which, assuming the doctrine of creatio-ex-nihilo (i.e., creation out of nothing), would require the Son and the Spirit to be brought from non-being into being at some point in time. However, as the Son and the Spirit are backwardly everlasting, this is clearly not the case. |

| 69 | For further clarity, (MR2) can also be translated into predicate logic and reduced to three premises as follows (where f stands for the Father, s for the Son, h for the Spirit and G for God):

With this alternative reading, in comparison to (IR), we have a numerical identity relation being retained in (MR2), with solely the negation of a relation of a qualitative identity (sameness) between them—which is brought out in the main text by stating in (4’)–(6’) that each of the Divinity-Aspects is not identical (i.e., ≠) to another. Importantly, however, this is not a form of relative identity, as identity is not assumed to be relative in this specific account. |

| 70 | I am grateful to the editors and publishers of the International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and the European Journal for Philosophy of Religion for allowing me to reuse certain material from previously published work. |

References

- Alvarado, José. T. 2019. Are Tropes Simple? Teorema 38: 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, David. 1997. A World of States of Affairs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, L. 2004. Nicaea and Its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Lynne R. 2005. When Does a Person Begin? Social Philosophy and Policy 22: 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, Lynne R. 2007. Persons and the metaphysics of resurrection. Religious Studies 43: 333–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Lynne R. 2013. Naturalism and the First-Person Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, Donald L. M. 1999. The Discernibility of Identicals. Journal of Philosophical Research 24: 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Donald L. M. 2001. Instantiation as partial identity. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 79: 449–64. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, Donald L. M. 2016. Aspects and the Alteration of Temporal Simples. Manuscrito 39: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Donald L. M. 2018a. Self-Differing, Aspects, and Leibniz’s Law. Noûs 52: 900–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Donald L. M. 2018b. Oneness, Aspects, and the Neo-Confucians. In The Oneness Hypothesis: Beyond the Boundary of Self. Edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe, Owen Flanagan, Victoria S. Harrison, Hagop Sarkissian and Eric Schwitzgebel. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, Donald L. M. 2018c. Temporary and Contingent Instantiation as Partial Identity. International Journal for Philosophical Studies 26: 763–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, John. 2004. The Nicene Faith Part 1 & Part 2. New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, John. 2018. One God Father Almighty. Modern Theology 34: 320–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Karen. 2011. By Our Bootsraps. Philosophical Perspectives 25: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Karen. 2017. Making Things Up. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, Einar. 2021. Composition as identity: Pushing forward. Synthese 198: 4595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Alexander. 2007. Nature’s Metaphysics: Laws And Properties. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Branson, Beau. 2022. One God, the Father. TheoLogica: An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and Philosophical Theology 6: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Keith. 1990. Abstract Particulars. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, Richard. 1987. On the Logical Problem of the Trinity. In Philosophical Essays. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Carruth, Alexander. 2015. Powerful Qualities, Zombies and Inconceivability. The Philosophical Quarterly 66: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Stephen T. 2006. Christian Philosophical Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Effingham, Nikk. 2015a. The Location of Properties. Noûs 49: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effingham, Nikk. 2015b. Multiple Location and Christian Philosophical Theology. Faith and Philosophy 32: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehring, Douglas. 2011. Tropes: Properties, Objects and Mental Causation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Brian. 2001. Scientific Essentialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhard, Kristina. 2010. Categories and the Ontology of Powers: A Vindication of the Identity Theory of Properties. In The Metaphysics of Powers: Their Grounding and Their Manifestations. Edited by Anna Marmodoro. New York: Routledge, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Erismann, Christophe. 2008. The Trinity, Universals, and Particular Substances: Philoponus and Roscelin. Traditio 53: 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Kit. 2000. Neutral Relations. Philosophical Review 199: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Kit. 2012. Guide to Ground. In Metaphysical Grounding: Understanding the Structure of Reality. Edited by Fabrice Correia and B. Schnieder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 37–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Anthony. R. J. 2018. Instantiation in Trope Theory. American Philosophical Quarterly 55: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Anthony. R. J. 2020. Abstracta and Abstraction in Trope Theory. Philosophical Papers 49: 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois, André. 1998. Occasions of Identity: A Study in the Metaphysics of Persistence, Change, and Sameness. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Robert K. 2015a. Two Ways to Particularize a Property. Journal of the American Philosophical Association 1: 635–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Robert K. 2015b. Is Trope Theory a Divided House? In The Problem of Universals in Contemporary Philosophy. Edited by Gabriele Galluzzo and Michael Loux. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 133–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gasser, Georg. 2019. God’s omnipresence in the world: On possible meanings of ‘en’ in panentheism. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 85: 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotti, Joaquim. 2019. The Identity Theory of Powers Revised. Erkenntnis 86: 603–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilmore, Cody. 2018. Location and Mereology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved March 2021. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/location-mereology/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Hasker, William. 2013. Metaphysics And The Tri-Personal Divinity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, John. 2009. Relations. In The Routledge Companion to Metaphysics. Edited by Robin. L. Poidevin. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, John. 2012. The Universe As We Find It. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Hud. 2009. Omnipresence. In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophical Theology. Edited by Thomas Flint and Michael Rea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Christopher. 1989. On a Complex Theory of a Simple God: An Investigation in Aquinas’ Philosophical Theology. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingthorsson, Rögnvaldur. 2013. Properties: Qualities, Powers, or Both? Dialectica 67: 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, Ross. 2017. Omnipresence and the Location of the Immaterial. In Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion, 8th ed. Edited by Jonathan Kvanvig. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 168–206. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Jonathan. 2011. Powerful Qualities, Not Pure Powers. Monist 94: 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, William. 2016. Structure And The Metaphysics Of Mind: How Hylomorphism Solves The Mind-Body Problem. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, John N. D. 1964. Athanasian Creed. Manhattan: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, John N. D. 1968. Early Christian Doctrine, 4th ed. London: Adam & Charles Black. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, Rae, and David Lewis. 1998. Defining ‘Intrinsic’. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58: 333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftow, Brian. 2004. A Latin Trinity. Faith and Philosophy 21: 304–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, Jerrold. 1978. Properties and Related Entities. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 39: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, David. 1983. New work for a theory of universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 61: 343–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loux, Michael. 2015. An exercise in constituent ontology. In The Problem of Universals in Contemporary Philosophy. Edited by Gabriele Galluzzo and Michael Loux. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–45. [Google Scholar]

- Macbride, Fraser. 2004. Whence the Particular-Universal Distinction? Grazer Philosophische Studien 67: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbride, Fraser. 2020. Relations. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved March 2021. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relations/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Martin, Charlie B. 2008. The Mind in Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Charlie B., and John Heil. 1999. The Ontological Turn. Midwest Studies in Philosophy 23: 34–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurin, Anna-S. 2018. Tropes. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved March 2021. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/tropes/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- McDaniel, Kris. 2014. Parthood is identity. In Mereology and Location. Edited by S. Kleinschmidt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, George. 2003. Powers: A Study in Metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moreland, James P., and William Lane Craig. 2003. Philosophical Foundations For A Christian Worldview, 1st ed. Westmont: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, Stephen, and Rani L. Anjum. 2010. A Powerful Theory of Causation. In The Metaphysics of Powers: Their Grounding and Their Manifestations. Edited by Anna Marmadoro. New York: Routledge, pp. 143–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, Ryan T. 2020. Trinity, Subordination, and Heresy: A Reply to Mark Edwards. TheoLogica: An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and Philosophical Theology 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orilia, Francesco. 2008. The Problem of Order in Relational States of Affairs: A Leibnizian View. In Fostering the Ontological Turn: Essays on Gustav Bergmann. Edited by Guido Bonino and Rosaria Egidi. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, pp. 161–86. [Google Scholar]

- Orilia, Francesco. 2011. Relational Order and Onto-Thematic Roles. Metaphysica 12: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orilia, Francesco. 2014. Positions, ordering relations and o-roles. Dialectica 68: 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, Michele. 2016. Non-Symmetrical Relations, O-Roles and Modes. Acta Analytica 31: 373–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, Michele. 2019. The Holy Trinity and the Ontology of Relations. Sophia 60: 173–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawl, Timothy. 2020. Conciliar Trinitarianism, Divine Identity Claims, and Subordination. TheoLogica: An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and Philosophical Theology 4: 102–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platinga, Alvin. 2000. Warrented Christian Belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pruss, Alexander. 2013. Omnipresence, Multilocation, the Real Presence and Time Travel. Journal of Analytic Theology 1: 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, Michael. 2020. (Re)discovering Ground. In The Cambridge History of Philosophy, 1945–2015. Edited by Kelly Becker and Iain D. Thomson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 147–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Gideon. 2010. Metaphysical Dependence: Grounding and Reduction. In Modality: Metaphysics, Logic, and Epistemology. Edited by Bob Hale and Aviv Hoffmann. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 109–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, Jonathan. 2009. On what Grounds what. In Metametaphysics: New Essays on the Foundations of Ontology. Edited by David Manley, David J. Chalmers and Ryan Wasserman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 347–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, Jonathan. 2016. Grounding in the Image of Causation. Philosophical Studies 173: 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, Jonathan. 2021. Ground Functionalism. In Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Mind 1. Edited by U. Kriegel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, Sydney. 1980. Causality and properties. In Time and Cause. Edited by Peter van Inwagen. Kufstein: Reidel, pp. 109–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sider, Theodore. 2007. Parthood. Philosophical Review 116: 51–91. [Google Scholar]

- Strawson, Galen. 2008. The identity of the categorical and the dispositional. Analysis 68: 271–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijuwade, Joshua. 2021. Monarchical Trinitarianism: A Metaphysical Proposal. TheoLogica: An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and Philosophical Theology 5: 41–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijuwade, Joshua. 2022. Building the monarchy of the Father. Religious Studies 58: 436–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburne, Richard. 1994. The Christian Divinity. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2016. The Coherence of Theism: Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, John H. 2013. In Defence of Powerful Qualities. Metaphysica 14: 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, John H. 2017. Powerful qualities and pure powers. Philosophical Studies 175: 1423–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, John H. 2019. Powerful Problems for Powerful Qualities. Erkenntnis 87: 425–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, John. 2014. Donald Baxter’s Composition as Identity. In Composition as Identity. Edited by D. Baxter and A. Cotnoir. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 225–43. [Google Scholar]

- van Inwagen, Peter. 1995. And Yet They Are Not Three Divinitys But One Divinity. In Divinity, Knowledge & Mystery: Essays in Philosophical Theology. Edited by Peter van Inwagen. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 241–78. [Google Scholar]

- van Inwagen, Peter. 2003. Three Persons in One Being: On Attempts to Show That the Doctrine of the Trinity is Self-Contradictory. In The Trinity: East/West Dialogue. Edited by Melville Y. Stewart. Boston: Kluwer, pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga, Edward. 2004. Trinity and Polytheism. Faith and Philosophy 21: 281–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierenga, Edward. 2010. Omnipresence. In A Companion to the Philosophy of Religion. Edited by Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper and Philip Quinn. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 258–62. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Donald C. 1953. On the Elements of Being II. Review of Metaphysics 7: 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Donald C. 1986. Universals and Existents. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 64: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Alastair. 2018. Metaphysical Causation. Noûs 52: 723–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grounding Principles | IndependentG (Ungrounded) | CompleteG (Ground) |

|---|---|---|

| Directed | This entity does not rank below any other entity in the hierarchical structure of reality. | This entity is part of a set that ranks higher than any other entity in the hierarchical structure of reality within the specific world in which this set exists. |

| Necessitating | The existence of another entity does not necessitate the existence of this entity. | This entity is part of a set that necessitates the existence of every other entity within the specific world in which this set exists. |

| Generative | This entity’s existence and intrinsic nature are not fixed by the existence and intrinsic nature of any other entity. | This entity is part of a set whose existence fixes the existence and intrinsic nature of every other entity within the specific world in which this set exists. |

| Explanatory | This entity’s existence, at a specific time, is not explained by the existence of any other entity. | This entity is part of a set that, at a specific time, explains the existence of all other entities within the specific world in which this set exists. |

| Causal | This entity is not a grounded effect of any other entity. | This entity is part of a set that is the metaphysical cause of other entities, which are grounded effects within the specific world in which this set exists. |

| Grounding Principles | IndependentG (Ungrounded) | CompleteG (Ground) |

|---|---|---|

| Directed | The Father (Divinityy[y@r1]) does not rank below the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) or any other entity in the hierarchical structure of reality. | The Father (Divinityy[y@r1]) ranks higher than the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) and any other entity in the hierarchical structure of reality within the specific world in which he exists. |

| Necessitating | The existence of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) or any other entity does not necessitate the existence of the Father. | The Father’s (Divinityy[y@r1]) existence necessitates the existence of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3])and every other entity within the specific world in which he exists. |

| Generative | The Father’s (Divinityy[y@r1]) existence and intrinsic nature are not fixed by the existence and intrinsic nature of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) or any other entity. | The Father’s (Divinityy[y@r1]) existence and intrinsic nature fix the existence and intrinsic nature of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) and every other entity within the specific world in which he exists. |

| Explanatory | The Father’s (Divinityy[y@r1]) existence, at a specific time, is not explained by the existence of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) or any other entity. | The Father’s (Divinityy[y@r1]) existence, at a specific time, explains the existence of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) and all other entities within the specific world in which he exists. |

| Causal | The Father (Divinityy[y@r1]) is not a grounded effect of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]) or any other entity. | The Father (Divinityy[y@r1]) is the metaphysical cause of the Son (i.e., Divinityy[y@r2]) and the Spirit (i.e., Divinityy[y@r3]), and all other entities that are grounded effects within the specific world in which he exists. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sijuwade, J.R. The Logical Problem of the Trinity: A New Solution. Religions 2022, 13, 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090809

Sijuwade JR. The Logical Problem of the Trinity: A New Solution. Religions. 2022; 13(9):809. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090809

Chicago/Turabian StyleSijuwade, Joshua Reginald. 2022. "The Logical Problem of the Trinity: A New Solution" Religions 13, no. 9: 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090809

APA StyleSijuwade, J. R. (2022). The Logical Problem of the Trinity: A New Solution. Religions, 13(9), 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090809