Abstract

Religious individuals and communities often struggle with anger toward God (ATG) upon experiencing suffering. ATG is related to poor mental health. Certain types of religiousness can moderate the effect of this negative feeling on well-being; however, research varies. Therefore, this study aims to determine whether religion at the individual (spirituality) or communal levels (moral community) may affect the association of ATG with well-being. Moderation analysis was performed on data from 307 students at a Christian university in Indonesia. Spirituality lowered the effect of ATG as one form of a religious stressor on well-being, but moral community did not. Both the cognitive and affective aspects of spirituality (individual level) are needed to buffer the effects of ATG on well-being. Conversely, the moral/behavior and belonging/communal aspect of a moral community (communal level) do not appear to ensure support for the individual with ATG. The implications of this study are discussed below.

1. Introduction

Anger toward God (ATG) is a negative feeling toward God. This negative feeling can range from disappointment and feeling abandoned to feeling angry at God (Exline and Rose 2013; Wood et al. 2010). It is a form of religious and spiritual struggle in the divine domain (Pargament 1997). In monotheistic religions, the relationship with God is, to some extent, similar to relationships with other human beings. Exline et al. (2011) concluded that the cognitive and emotional processes involved in the relationship with God are similar to those involved in relationships with other human beings. Therefore, a relationship with God can induce both positive and negative feelings, similar to human relationships. Christians are prone to both feelings toward God because Christians believe in a personal God and use anthropomorphic metaphors to describe their relationship with God (Beck and Haugen 2012). Given that Christians view their God as a loving and powerful God, when their life experiences seem to contradict their beliefs, they may experience ATG.

A religious person is more prone to feel ATG as they tend to interpret events as being caused by God (Gorsuch and Smith 1983; Garey et al. 2016). Legare et al. (2012) also noticed that natural and supernatural explanations can coexist in how individuals interpret events in their lives. For example, if a family member died due to a car accident, a natural explanation for this unfortunate event may exist. However, religious individuals may still think that this incident happened because God allowed it or that God could easily have forbidden this incident. The more religious an individual, the more they believe in the sovereignty of God. As such, they may hold God responsible for their misery or the tragedy they see around them; this may lead to ATG.

Exline et al. (2011) found that many people may feel ATG, even though their level of anger may be low. Another study in Poland, a highly religious country, found a similar result. Both Catholics and non-believers experienced a low intensity of ATG (Zarzycka 2016). It is common for religious people to feel ATG. Feeling angry toward God does not mean that they do not love God, as people can feel both negative and positive feelings at the same time.

Studies on ATG are thus highly relevant for Indonesians as 93% of the population consider religion “very important” in their lives (Pew Research Center 2018). As such, God is deeply immersed in daily life, and Indonesian culture is deeply intertwined with religion. The importance of religion is indicated in the first sila (principle) of the country’s foundational philosophy, Pancasila (literally “Five Principles”): “Belief in the almighty God.” Indonesia also has a highly collectivist culture. People are closely interdependent, such that it would be difficult for individuals to distance themselves from the culture and religiousness deeply embedded in Indonesian society.

Previous studies consistently found ATG related to negative mental health such as anxiety, depression, and dissatisfaction with life (Abu-Raiya et al. 2015; Wilt et al. 2016; Aditya et al. 2020). Therefore, researchers were interested to find variables that can reduce the effect of ATG on well-being. Studies by Abu-Raiya et al. (2016) and Yali et al. (2019) found that certain types of religiousness significantly moderated the effect of ATG on well-being. Abu-Raiya et al. (2016) found that religious commitment, sanctification, religious support, and religious hope reduced the negative effect of religious and spiritual struggles (ATG constituting one form) on the well-being of American adults (M = 50.74, SD = 19). These four religious variables assess spirituality and closeness to God. The higher one’s level of spirituality and closeness to God, the lower the effect of religious and spiritual struggles on well-being. However, a study conducted by Yali et al. (2019) on a younger population (M = 19.99, SD = 3.56) found that one’s closeness to God increases the negative effect of ATG on well-being. The higher one’s level of closeness to God, the lower one’s well-being when they experience ATG. Therefore, contradictory results require further investigation.

This study aimed to clarify the kind of religiousness that acts as a buffer against the effects of ATG in Christian college students in Indonesia. Indonesia has a very different culture from the United States, which may influence religiousness and its relationship with other variables (Saroglou and Cohen 2011). For example, Sujarwoto et al. (2018) found that factors of happiness and well-being among Indonesians are beyond the individual level and that both individual religiosity and community social capital found in traditions may increase well-being. Therefore, it is essential to study religiousness at both individual and communal levels in Indonesia. In this study, we explore the spirituality (individual) and moral community (communal) aspects of religiousness and identify which would buffer the effect of ATG among Indonesians.

College students, who are in the transition and exploration stages, are prone to experiencing ATG. During childhood, they inherit beliefs from their parents and other authorities. In college, students may start questioning their beliefs to determine their convictions or when confronted by suffering and evil in the world (Arnett 2000; Bryant and Astin 2008). Simultaneously, they become more critical as their cognitive abilities mature.

Exline et al. (2011) and Zarzycka (2016) confirmed that the level of ATG tends to decrease with age. Therefore, it can be inferred that college students may have higher levels of ATG when compared to older generations. Students in evangelical universities experience more religious struggles than those in non-evangelical universities (Bryant and Astin 2008; Carter 2019). Therefore, the respondents in this study were Christian and Catholic college students from a Christian university.

Religiousness

Saroglou (2011) believed that all religions have four dimensions: Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging. These four dimensions represent cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social psychological processes, respectively. Believing, as a cognitive part of religiousness, focuses on doctrines. Bonding is the emotional part of religiousness, such as the feeling of attachment to the transcendent. Behaving is the moral part of religiousness and consists of norms, practices, and values taught by religion. Belonging is a social connection with other believers. Given that religion is multidimensional, a good religiousness scale should measure the multi-dimensions of religion (Koenig 2018; Abu-Raiya 2013; Saroglou 2011).

Saroglou (2011) constructed a measure of religiousness that consists of the four basic dimensions of religiousness (4-BDRS). Each dimension can merge with another and form a typology. For example, believing and behaving together create a typology called intrinsic religion. There are six typologies, but in this study, only two are used: Spirituality and moral community. Spirituality is a combination of the believing and bonding dimensions, while the moral community is a combination of the behaving and belonging dimensions. The two typologies represent individual- and communal-level religiousness, respectively. Both levels of religiousness may be important in predicting well-being in a collectivist country such as Indonesia (Sujarwoto et al. 2018).

The spirituality typology emphasizes the relationship with the transcendent and involves knowledge about the transcendent and a relationship with the deity. In Christian terms, it is often called “knowing God.” It is more than just understanding God cognitively, but also involves having an emotional bond with God. Spirituality can help to find meaning in life and can help produce a positive emotion with God (Saroglou 2011). Meaning and closeness to God were found to buffer the effect of ATG on well-being (Exline et al. 2011; Abu-Raiya et al. 2016; Zarzycka 2016). Therefore, we expect spirituality to buffer the effect of ATG on well-being. If this is true, psychological counseling or interventions could focus more on the individual aspect of religiousness (spirituality), rather than the moral community aspect to cope with ATG.

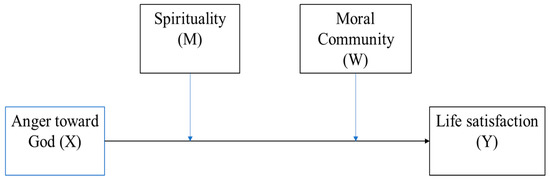

The moral community emphasizes the moral principles of and support from religious groups. It directs group members to follow certain ethics held by the group (Graham and Haidt 2010). In one sense, a moral community can give its members social support in times of trouble; in turn, this can act as a buffer against the loss of well-being. Therefore, one may be consoled by sharing personal struggles with other members of the moral community, thus easing suffering. However, respondents in this study were taken from a Christian university, and many Christians think that true believers should not feel ATG (Exline et al. 2012). Therefore, disclosing this negative feeling may involve risks. Considering the contradictory effects of the moral community, we hypothesize that the moral community is not a significant buffer for the effect of ATG on well-being. The conceptual framework of the hypotheses is reflected in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the main hypotheses.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Data were collected from a Christian university in Tangerang, Banten, Indonesia, as part of a larger project. Questionnaires were distributed in liberal art classes using a convenience sampling method, and 719 respondents returned the questionnaires. However, 204 questionnaires were discarded because the respondents gave the same answer on one or more scales or did not answer demographic questions completely. Of the 515 respondents, only 307 Protestant and Roman Catholic participants were chosen for this study (226 Protestants and 81 Roman Catholics; 71 men and 236 women). The age of the respondents ranged from 17 to 24 years (M = 19.04, SD = 1.1). Most of the respondents (57%) were Chinese Indonesians, while 22%, 7%, 6%, and 5% were of mixed ethnicity, Manadonese, Javanese, or Batak, respectively. The rest were from other ethnicities in Indonesia.

2.2. Measures

As this study was part of a larger study, besides the questionnaires described below, the respondents received the following scales: Generalized Anxiety Scale-7 (Spitzer et al. 2006), Personal Meaningful Profile-Brief (McDonald et al. 2012), and Religious Commitment Inventory-10 (Worthington et al. 2003).

Religiousness. The level of religiousness—namely, believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging—was assessed using the 4-BDRS (Saroglou 2011). Each dimension consists of three items rated on a seven-point Likert scale. The factorial structure of the 4-BDRS was confirmed in Aditya et al. (2021). In other word, the uniqueness of the four dimensions of the 4-BDRS has been established.

In this study, combinations of two dimensions from the 4-BDRS, called typologies, were used to assess religiousness; these typologies were Spirituality (a combination of believing and bonding) and moral community (a combination of behaving and belonging). By combining two dimensions, we obtain two types of religiousness (spirituality and moral community) for the analysis in this paper.

The religiousness scale (4-BDRS) used here does not contain many overlapping items measuring spiritual well-being or emotional well-being (a concern raised by Garssen et al. 2016). Rather, it measures dimensions of religiousness felt by religious individuals (cognitive/believing, affective/bonding, behavioral/moral, and belonging/communal). The sample items for each typology are as follows: Spirituality (“I feel attached to religion because it helps me to have a purpose in my life”), moral community (In religion, I enjoy belonging to a group/community). Internal reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha and was 0.87 for spirituality and 0.86 for the moral community.

ATG. ATG was assessed using the four-item ATG subscale of the Attitudes toward God Scale (ATGS-9) (Wood et al. 2010; Aditya et al. 2022). The sample items include, “Feel angry at God.” The ATGS-9 had nine items that had to be rated on a 10-point Likert scale. Internal reliability measured using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

Well-being. Well-being was assessed using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). (Diener et al. 1985). The SWLS had five items on a 7-point Likert scale. Internal reliability measured using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85. Sample questions on the SWLS include: “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”, and “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.”

2.3. Analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS 25. Moderation analysis was conducted using PROCESS macro (Hayes 2018). As the correlation between spirituality and moral community is high, a simple moderation analysis (Model 1; Hayes 2018) was used instead of a double moderation analysis (Model 2; Hayes 2018) to test whether the relationship between ATG and well-being was moderated by spirituality and the moral community. In the first moderation analysis, the moral community was used as a moderator, while in the second moderation analysis, spirituality was used as a moderator.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlational Statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the main variables. The level of spirituality and the moral community was high (11 and 10.41, out of a maximum of 14). There was a rather low ATG (1.77 out of a maximum of 10), and a rather high degree of well-being (4.4 out of a maximum of 7). The correlation between moral community and well-being is much higher than the correlation between spirituality and well-being, and this is consistent with the results of prior studies, which found belonging (part of the moral community) had the highest correlation with well-being (Aditya et al. 2018; Saputra et al. 2016). Spirituality and moral community have a high correlation. This is consistent with the result of Saroglou et al. (2020), who found a high correlation among the four dimensions of 4-BDRS. In spite of the high intercorrelation, these two typologies of religiousness are distinct constructs, as proven in the previous study (Saroglou et al. 2020) and this current research. It is also an indication that respondents from this study are highly religious (Pew Research Center 2018). In religious people, all dimensions of religiousness tend to be intercorrelated (Saroglou 2011).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

3.2. Regression Analysis

ATG, spirituality, moral community, and well-being. As shown in Table 2, the interaction between anger and moral community was not significant (B = 0.03, p > 0.05; 0 was in the 95% confidence interval). However, as shown in Table 3, the interaction between anger and spirituality was significant (B = 0.07, p < 0.05; 0 was not in the 95% confidence interval). This means that spirituality significantly moderated the effect of ATG on well-being, while moral community did not.

Table 2.

Moderation analysis: Anger, moral community, and well-being.

Table 3.

Moderation analysis: Anger, spirituality, and well-being.

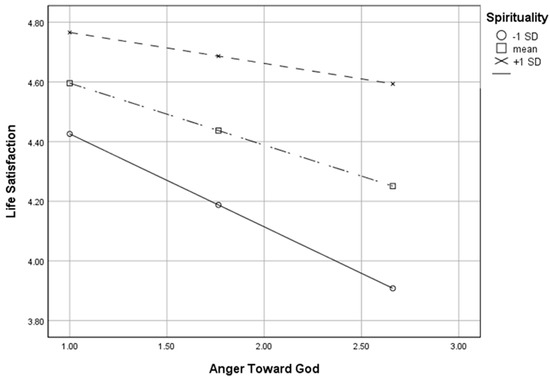

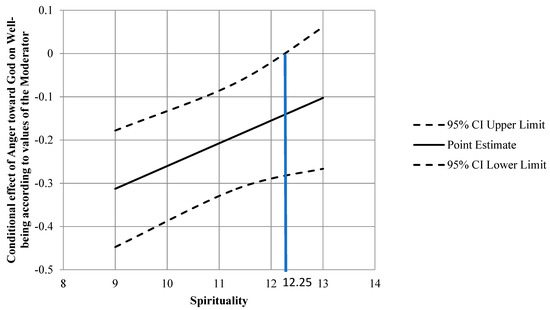

The simple slope for the association between ATG and spirituality was tested at the third level of spirituality (−1 SD, mean, and +1 SD), as presented in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows that the magnitude of the negative correlation between ATG and well-being decreased as the level of spirituality increased. This implies that the association between ATG and well-being was more influential for those with low levels of spirituality. The Johnson–Neyman (JN) technique, as depicted in Figure 3, revealed that the effect of anger on well-being was no longer significant when the level of spirituality was the same or above 12.25 since 0 appeared in the confidence interval if the level of spirituality was 12.25. In other words, ATG did not have any effect on the well-being of those with a spirituality level of 12.25 and above. In this study, 94 (30.61%) students had spirituality levels above 12.25.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes showing the interaction between ATG and spirituality and the effect on well-being.

Figure 3.

Interaction between ATG and spirituality and the effect on well-being using the Johnson–Neyman technique.

4. Discussions

Garssen et al. (2016) raised a legitimate concern regarding tautology when assessing subjective well-being using religiosity scales that have items referring to emotional well-being. Out of 12 items of the 4-BDRS, 1 item referring to emotional well-being (“religious rituals, activities or practices make me feel positive emotion”) is far below the cut off score (25%) suggested by Garssen. Meanwhile, the ATGS-9 also has one item (“feel angry at God”) that is within the cut off score (one out of four items for the Anger toward God dimension). Therefore, both the 4-BDRS and ATGS provide distinct measures and do not overlap with the assessment of subjective well-being measured by SWLS. Consistent with previous studies, ATG was associated with lower levels of well-being, while spirituality and the moral community were associated with higher levels of well-being (Exline et al. 2017; Exline et al. 2011; Zarzycka 2016). The moderation analysis found that spirituality significantly moderated the effect of anger on well-being. However, moral community did not. Therefore, the main hypotheses of this study are confirmed.

As predicted, spirituality is likely to have a buffering effect. College students with high levels of spirituality have a better chance of maintaining their well-being even when they feel ATG. High levels of spirituality are characterized by high levels of belief and bonding. College students with high spirituality knew their God personally and understand that God cares about their lives and can change circumstances for their benefit (Romans 8:29). This understanding helps them find meaning in their difficulties; as such, their well-being is not affected much (Exline et al. 2011). Abu-Raiya et al. (2016) also found that, among individuals who understood that their struggles could have positive effects on their lives, well-being was not highly affected by struggle.

The effect of believing (cognitive understanding) is intertwined with bonding (emotional closeness to God). College students with high levels of bonding have a good relationship with God. Given that the relationship with God mimics the intimacy and trust in any close relationship, Christian college students with high levels of believing and bonding (high spirituality) are likely to be able to positively interpret their incidents (Kim et al. 2015). They will continue to trust God’s goodness and believe that these incidents will ultimately serve their goodness. Therefore, spirituality has a buffering effect, and for students with levels of spirituality above 12.25, the effect of ATG no longer significantly affected well-being.

The results of this study differ from the findings of Yali et al. (2019), who found that the higher the level of closeness, the higher the effect of ATG on well-being. They argued that people who are less close to God are not bothered about being angry with God and may feel that their anger is justified. Conversely, those closer to God may perceive ATG as a threat; such anger represents damage to their relationship with God, in turn disturbing their well-being. A similar phenomenon was found by Carter (2019) who observed that students from evangelical institutions experienced higher levels of religious struggles than those from other institutions.

Yali et al. (2019) state that facilitating continued engagement in one’s relationship with God may buffer the effect of ATG. Our study used a combination of closeness and belief, which may confirm their suggestion. Christian college students with high levels of belief understand that God loves them and that the suffering they face is not caused by God, but is rather the side effect of living in a sinful world (Horton 2016). This understanding may facilitate continued engagement in their relationship with God; in turn, this may counterbalance their emotional disturbance thus buffering the effect of ATG on well-being.

The importance of both the cognitive (believing) and bonding (affective) components of spirituality in buffering religious struggles was also attested to by Abu-Raiya et al. (2016), who found that both the sanctification of life and religious support moderate the effect of religious struggle and stress on well-being. Life sanctification in Abu-Raiya’s study is similar to the cognitive (believing) component of spirituality (e.g., “I feel there is something about me that is sacred”), where one perceives seemingly secular aspects of life as having a divine character. Meanwhile, religious support in Abu-Raiya’s study is similar to the affective (bonding) component of spirituality (e.g., “Sought God’s love and care”). In our study, believing and bonding are factors for spirituality that work together to buffer the effect of ATG on well-being.

Table 2 indicated that being part of a moral community when adjusted for ATG seems to be beneficial for well-being. The results of the correlation (Table 1) supported the idea that moral community was beneficial for well-being. However, the moral community did not have any significant effect on our findings. The moral community used in this study is a combination of the behaving and belonging dimensions of the 4-BDRS (Saroglou 2011). Belonging is the dimension of the 4-BDRS that has the highest association with well-being for college students in Indonesia (Wardoyo and Aditya 2021). However, behaving was associated with a higher level of anger and was not associated with comfort toward God. Therefore, it makes sense that moral community has a positive contribution to well-being, but it did not help in reducing the effect of anger on well-being. It may also reflect the situation of the respondents, who are from a Christian university where anger toward God is not encouraged. They also live in a Muslim-majority country where anger toward God is prohibited (Abu-Raiya et al. 2015), which may influence their perception of ATG. Although religions bind people together into moral communities where they may receive communal support (Graham and Haidt 2010), there remains no guarantee that people may be comfortable sharing their feelings of ATG or receive support for such feelings. Yali et al. (2019) discovered that even when ATG was deemed morally acceptable, it only led people to be more readily angry; in turn, this had the potential to reduce well-being.

The behaving dimension of 4-BDRS only measures the importance of the moral behavior dimension of religiousness perceived by individuals, but not the content of the moral teachings. If being angry at God is perceived to be morally wrong by the consensus of the community, then the Moral Community type of religiousness (Behaving + Belonging) will not help lower ATG, as seems to be the case in our study. However, if moral teachings provide a room for lamentations and other free expressions of distress toward God, then the results might be different. Future studies may study this prediction.

5. Implications, Limitations, and Directions for Future Studies

The findings of this study underscore the importance of having both an understanding of doctrine (believing) and a relationship with God (bonding). Therefore, it is important for counselors working with Christians to address both dimensions of religiousness to help them overcome their ATG.

It also seems important to pay attention to the kind of moral consensus that colors the interrelation in the religious community. It is true that the community can provide support and increase well-being. However, certain moral teachings prohibiting ATG can put communal pressure on individuals experiencing ATG. Ministers and counselors could help shape community values through their teachings and relations with clients.

The respondents in this study came from various ethnic backgrounds in Indonesia, but they were limited to one Christian university, with specific ideas and practices in nurturing the life of faith through education. The sampling method was convenience sampling. Therefore, future studies need to consider recruiting respondents from other universities and religious backgrounds in Indonesia and using a more rigorous sampling method to ensure the results will not be considerably limited by the context. The respondents of this study were chosen from among general students and not those who had experienced distress. It would be interesting to study distressed students to determine whether spirituality still displays a buffering effect.

Having anger toward God is not always negative. It is common in every type of human relationship. Anger toward God may indicate a relationship with God, and they may have a better relationship with God when they can resolve their anger and have better well-being afterward. This hypothesis can only be tested in a longitudinal study.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to explore the relationships between ATG and well-being as moderated by two types of religiousness: Spirituality and the moral community. The study discovered that moral community did not moderate the effect of ATG on well-being. The expression of ATG may be considered taboo within certain Christian communities. Despite ATG being considered morally acceptable, it does not automatically induce supportive action from the community, thus leaving angry believers with a reduced sense of well-being.

In contrast, we found that spirituality has a buffering effect on the relationship between ATG and well-being. For college students with spirituality levels of 12.25, the effect of ATG on well-being was no longer significant. The closeness to God (spirituality), which involves the mind and heart (cognitive and affective) of students, can help in forming positive attitudes in times of distress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A.; methodology, Y.A. and I.M.; software, Y.A.; validation, Y.A., I.M., J.A. and R.P.; formal analysis, Y.A.; investigation, Y.A. and I.M.; resources, Y.A., I.M. and J.A.; data curation, Y.A., I.M. and J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A., I.M., J.A. and R.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.A., I.M. and J.A.; visualization, Y.A.; supervision, Y.A. and I.M.; project administration, I.M. and R.P.; funding acquisition, Y.A., I.M., and R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Research and Higher Education of Indonesia: 26/AKM/PNT/2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Nusantara Scientific Psychology Consortium (Konsorsium Psikologi Ilmiah Nusantara) No. 0001/2019, 9 October 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham. 2013. The psychology of Islam: Current empirically based knowledge, potential challenges, and directions for future research. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality: Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, vol. 1, pp. 681–95. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Julie J. Exline, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Qutaiba Agbaria. 2015. Prevalence, Predictors, and Implications of Religious/Spiritual Struggles among Muslims. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 631–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Neal Krause. 2016. Religion as problem, religion as solution: Religious buffers of the links between religious/spiritual struggles and well-being/mental health. Quality of Life Research 25: 1265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aditya, Yonathan, Ihan Martoyo, Firmanto Adi Nurcahyo, Jessica Ariela, and Rudy Pramono. 2021. Factorial structure of the four basic dimensions of religiousness (4-BDRS) among Muslim and Christian college students in Indonesia. Cogent Psychology 8: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, Yonathan, Ihan Martoyo, Firmanto Adi Nurcahyo, Jessica Ariela, Yulmaida Amir, and Rudy Pramono. 2022. Indonesian students’ religiousness, comfort, and anger toward God during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 44: 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, Yonathan, Jessica Ariela, Ihan Martoyo, and Rudy Pramono. 2020. Does anger toward God moderate the relationship between religiousness and well-being? Roczniki Psychologiczne/annals of Psychology 23: 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, Yonathan, Riryn Sani, Ihan Martoyo, and Rudy Pramono. 2018. Predicting well-being from different dimensions of religiousness. Paper presented at the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS), Surabaya, Indonesia, November 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2000. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Richard, and Andrea D. Haugen. 2012. The Christian religion: A theological and psychological review. APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality: Context, Theory, and Research 1: 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Alyssa N., and Helen S. Astin. 2008. The correlates of spiritual struggle during the college years. The Journal of Higher Education 79: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Jennifer L. 2019. The predictors of religious struggle among undergraduates attending evangelical institutions. Christian Higher Education 18: 236–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., and Eric D. Rose. 2013. Religious and spiritual struggles. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 379–97. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Crystal L. Park, Joshua M. Smyth, and Michael P. Carey. 2011. Anger Toward God: Social-Cognitive Predictors, Prevalence, and Links with Adjustment to Bereavement and Cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., Kalman J. Kaplan, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2012. Anger, exit, and assertion: Do people see protest toward God as morally acceptable? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 264–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., Shanmukh Kamble, and Nick Stauner. 2017. Anger toward God(s) among undergraduates in India. Religions 8: 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garey, Evans, Juke R. Siregar, Ralph W. Hood, Hendriati Agustiani, and Kusdwiratri Setiono. 2016. Development and validation of Religious Attribution Scale: In association with religiosity and meaning in life among economically disadvantaged adolescents in Indonesia. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 19: 818–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garssen, Bert, Anja Visser, and Eltica de Jager Meezenbroek. 2016. Examining whether spirituality predicts subjective well-being: How to avoid tautology. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 141–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and Craig S. Smith. 1983. Attributions of responsibility to God: An interaction of religious beliefs and outcomes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22: 340–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Jesse, and Jonathan Haidt. 2010. Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 140–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Gilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, Michael. 2016. Core Christianity: Finding Yourself in God’s Story. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, John S., Yanna J. Weisberg, Jeffrey A. Simpson, M. Minda Oriña, Allison. K. Farrell, and William F. Johnson. 2015. Ruining it for both of us: The disruptive role of low-trust partners on conflict resolution in romantic relationships. Social Cognition 33: 520–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2018. Religion and Mental Health: Research and Clinical Application. San Diego: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Legare, Christine H., E. Margaret Evans, Karl S. Rosengren, and Paul L. Harris. 2012. The Coexistence of Natural and Supernatural Explanations Across Cultures and Development. Child Development 83: 779–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, Marvin J., Paul T. P. Wong, and Daniel T. Gingras. 2012. Meaning-in-life measures and development of a brief version of the Personal Meaning Profile. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed. Edited by Paul T. P. Wong. New York: Routledge, pp. 357–82. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. How Religious Commitment Varies by Country among People of all Ages. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2018/06/13/how-religious-commitment-varies-by-country-among-people-of-all-ages/ (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Saputra, Andy, Yonathan Aditya Goei, and Sri Lanawati. 2016. Hubungan Believing dan Belonging sebagai dimensi religiusitas dengan lima dimensi well-being pada mahasiswa di Tangerang. Jurnal Psikologi Ulayat 3: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassillis. 2011. Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: The big four religious dimensions and cultural variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassillis, and Adam B. Cohen. 2011. Psychology of culture and religion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1309–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassillis, Magali Clobert, Adam B. Cohen, Kathryn A. Johnson, Kevin L. Ladd, Matthieu Van Pachterbeke, Lucia Adamovova, Joanna Blogowska, Pierre-Yves Brandt, Cem Safak Çukur, and et al. 2020. Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: The cognitive, emotional, moral, and social dimensions of religiousness across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 51: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, Robert L., Kurt Kroenktse, Janet B. W. Williams, and Bernd Löwe. 2006. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1092–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujarwoto, Sujarwoto, Gindo Tampubolon, and Adi C. Pierewan. 2018. Individual and contextual factors of happiness and life satisfaction in a low middle income country. Applied Research in Quality of Life 13: 927–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardoyo, Jason T., and Yonathan Aditya. 2021. Religiusitas versus dukungan sosial: Manakah yang lebih berkontribusi bagi well-being mahasiswa? Jurnal Studi Pemuda 10: 163–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Joshua B. Grubbs, Julie J. Exline, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2016. Personality, religious and spiritual struggles, and well-being. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Benjamin T., Everett L. Worthington, Julie J. Exline, Ann Marie Yali, Jamie D. Aten, and Mark R. McMinn. 2010. Development, refinement, and psychometric properties of Attitudes toward God Scale (ATGS-9). Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2: 148–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, Everett. L., Jr., Nathaniel G. Wade, Terry L. Hight, Jennifer S. Ripley, Michael E. McCullough, Jack W. Berry, Michelle M. Schmitt, James T. Berry, Kevin H. Bursley, and Lynn O’Connor. 2003. The religious commitment inventory-10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology 50: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yali, Ann Marie, Sari (Sara) Glazer, and Julie J. Exline. 2019. Closeness to God, anger toward God, and seeing such anger as morally acceptable: Links to life satisfaction. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 22: 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2016. Prevalence and social-cognitive predictors of anger toward God in a Polish sample. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 26: 225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).