Saint Wilgefortis: A Queer Image for Today

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Legend of Wilgefortis

3. Interpretations of Wilgefortis

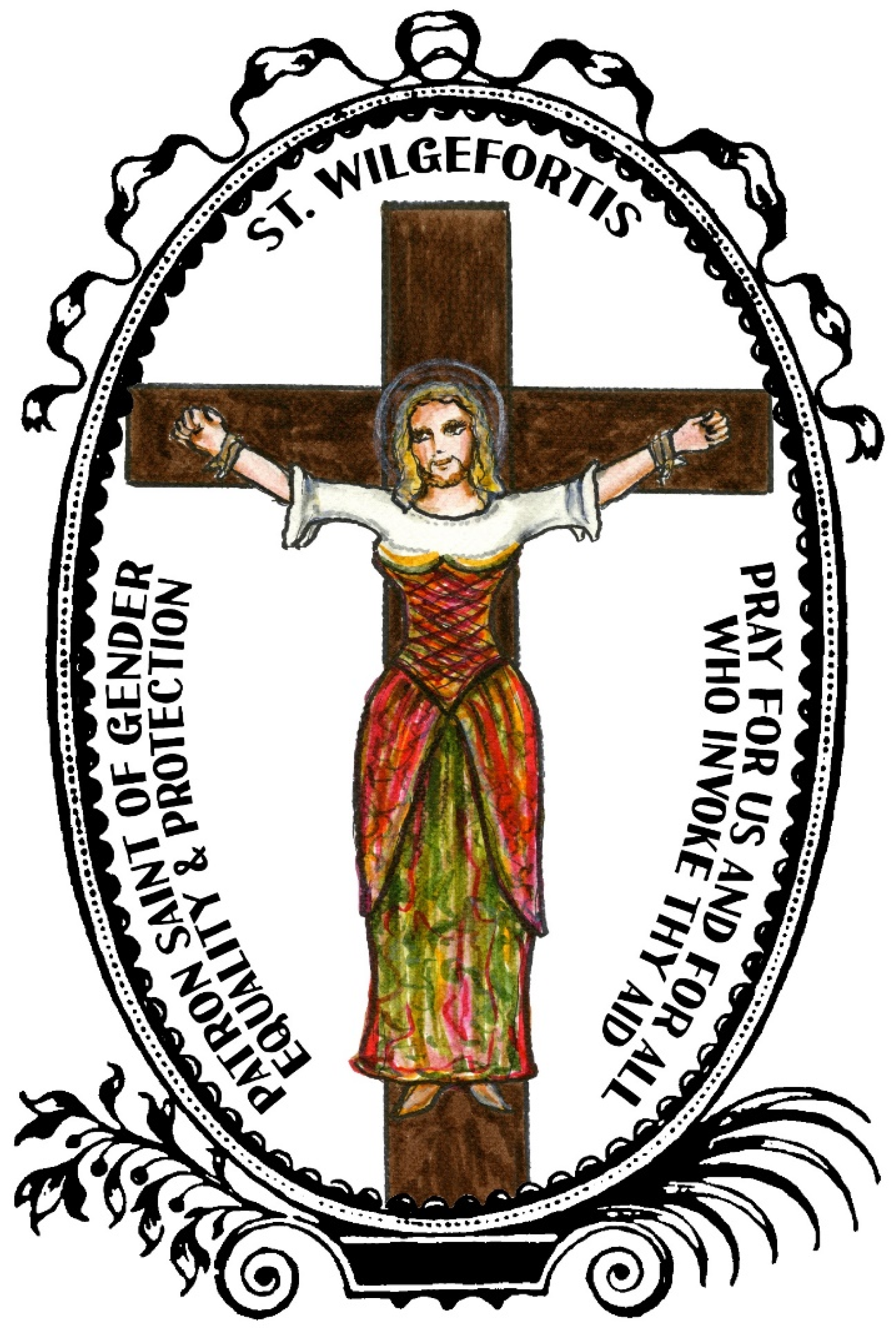

Wilgefortis’ image adorns the cover of this reader because her story offers a compelling example of how religion and sexuality intersect. It reveals, first, how sexuality regularly infuses religious devotion and identification. Wilgefortis’ religious devotion was expressed through her commitment to virginity and it was placed under threat because of an impending marriage. But there is something more here that solicits our interest in this saint’s story. For it indicates that holiness or sacredness may itself be “queer.” Here we take queer not as an identity (something that Wilgefortis has), but rather as a description of how her story unsettles binaries, such as male/female and human/divine.

4. Contemporary Images of Wilgefortis

5. Wilgefortis in the Liturgy

As you sing with the faithful in all times and all places, how often have you sang in terms that were not based on heterosexist binaries—father and mother, male and female? Are you invited to sing as “sopranos and altos/tenors and basses” or just as “women/men,” regardless of the voice God gave you? How is sexual diversity talked about and otherwise imaged in your worship? How do you recognize the one in every 2000 babies born with “indeterminate” sex organs? How many prayers begin only, “Brothers and Sisters?”.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The cisnormative view is that those who are assigned ‘female’ at birth will identify as a ‘woman’ and those assigned ‘male’ at birth will identify as a ‘man.’ It assumes a strict binary, erasing intersex people (those with variations of sex characteristics) and all those who do not identify as ‘women’ or ‘men.’ This is often coupled with heteronormativity, the assumption that romantic/sexual relationships are only between women and men. |

| 2 | The terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ are often conflated and “used synonymously in both social and legal contexts” (Viloria and Nieto 2020, p. 16). This article follows the definitions of Viloria and Nieto where ‘sex’ (female, male, intersex) refers to “biological traits” and ‘gender’ (woman, man, nonbinary) refers to “gender identity” (Viloria and Nieto 2020, p. 16). Furthermore, ‘sex/gender’ is used “in situations where it is accurate to note that both sex and gender, or either sex or gender, are being referenced” (Viloria and Nieto 2020, p. 16). For a helpful glossary of terms, see (Viloria and Nieto 2020, pp. 143–46). |

| 3 | Single quotation marks are used in this article around terms such as ‘female’ and ‘male’ to recognize their constructed nature. |

| 4 | For an in-depth look at emancipatory liturgical language and congregational song as it relates to intersex people, see (Budwey 2023, chp. 5). |

| 5 | The identity of the saint in this image has “long remained a mystery” (Bosch c. 1497), with some believing it to be Saint Julia of Corsica. However, after the image underwent restoration from 2013–2015, the beard was clearly visible and the person in the painting was identified as Wilgefortis. See also (Mills 2021). |

| 6 | The image of the decorated cross can be viewed here: https://www.twopartsitaly.com/blog/2017/9/16/the-legend-of-the-volto-santo-holy-face (accessed on 29 May 2022). |

| 7 | Friesen (2001, pp. 111–25) and others discuss the possibility of female hirsutism (de Jong and de Herder 2016; Katritzky 2014). |

| 8 | For the connection between Saint Librada and Wilgefortis see (González 2014/2015). |

| 9 | There is a statue of Saint Uncumber (16th c.) in The King Henry VII Chapel of Westminster Abbey in London (Lipscomb and Hoff 1963). In addition to Lipscomb and Hoff’s article, an image of this statue can be viewed here: https://genderben.com/2017/06/19/how-saint-wilgefortis-came-to-be-the-saint-of-bearded-ladies/ (accessed on 29 May 2022). |

| 10 | In discussing the cult of Saint Uncumber, Thomas More complained that women “reckon for a peck of oats she will not fail to uncumber them of their husbands” (Friesen 2001, p. 60). Furthermore, Lewis Wallace writes that “what is notable here is that Uncumber is not criticized for her appearance or gender blending, but for her unusual role as a patron saint of unhappy married women” (Wallace 2014, p. 57). |

| 11 | See also (Tanis 2017, pp. 147–48). Throughout this article I refer to the author by his present name, Justin Sabia-Tanis. |

| 12 | The image is Saint Wilgefortis the Bearded by Alana Kerr and can be viewed here: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/bloomsbury-reader-in-religion-sexuality-and-gender-9781474237789/ (accesed 29 May 2022). |

| 13 | This paragraph draws from (Budwey 2023, p. 144). For a theology of ‘both/neither,’ see (Budwey 2023, pp. 150—57). |

| 14 | I recognize that in the intersex community, ‘hermaphrodite’ can be an extremely hurtful term for some, while others are reclaiming it, and so I only use it in a historical context when it is specifically used by the author. |

| 15 | See also (DeVun 2021), particularly Chapter 6, which highlights writings where Christ is described from a feminine side as well as a joining of feminine and masculine. Chapter 6 also looks at The Jesus Hermaphrodite in alchemy. |

| 16 | The image can be downloaded here: https://myaltar.com/products/saint-wilgefortis-download (accessed on 29 May 2022). |

| 17 | For a discussion of Wilgefortis and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, see (Richardson 2020). For a discussion of some issues that might cause difficulty in Wilgefortis being adopted by transgender people, see (Mills 2021). |

| 18 | These images can be viewed here: https://qspirit.net/saint-wilgefortis-bearded-woman/ (accessed on 29 May 2022). The Queer Santas series also includes Saint Lucy, Saint Agatha, and Julia Pastrana (Tanis 2017, p. 144). |

| 19 | The image can be viewed here: http://almalopez.com/ourlady.html (accessed on 29 May 2022). For more about this image and the controversy surrounding it, see (Gaspar de Alba and López 2011). |

| 20 | López also describes the nature imagery as challenging the notion that being a lesbian is “unnatural” (Tanis 2017, p. 157). |

| 21 | For more on the sex/gender binary in liturgy, including the need for multiple images of God, the use of inclusive, expansive, and emancipatory language, as well as the stories of intersex people who have been made to feel excluded due to binary liturgical language and how this creates liturgical violence, see (Budwey 2023, chp. 5). |

| 22 | For a discussion of images of God and Jesus Christ that are outside of the sex/gender binary, see (Budwey 2023, pp. 137–50). |

| 23 | While many of these services fall under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella, it is important to acknowledge that not everyone outside of the sex/gender binary identifies as such. |

| 24 | Additionally, there are organizations such as enfleshed (https://enfleshed.com/liturgy/lgbtq-related/ accessed on 29 June 2022) and Q Worship (https://www.qworshipcollective.com/ accessed on 29 June 2022) that offer liturgical resources around trauma, healing, and worship for those in the queer community. |

| 25 | It is important to acknowledge that not all intersex and transgender people identify outside of the sex/gender binary. |

| 26 | A video of the service may be viewed here: https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=312541587280581 (accessed on 29 June 2022). For more information on the Saint Wilgefortis Mission, a mission to the transgender community, see here: http://cacina.org/index.php/17-parishes-and-missions/161-saint-wilgefortis-mission (accessed on 29 June 2022). |

| 27 | A video of the service may be viewed here: https://peoplespresbyterian.org/events/evening-prayer-for-saint-wilgefortis-day/ (accessed on 29 June 2022). |

| 28 | The English translation of the Latin prayer is: “Hail, holy servant of Christ, Wilgefortis, you loved Christ with all your soul; as you spurned marriage to the king of Sicily, you kept faith to the crucified Lord. You suffered the torments of imprisonment by order of your father; a beard grew on your face, a gift you obtained from Christ because you wished to be His; you confounded those who wished you to marry. When your impious father saw you thus deformed, he raised you up on the cross, where you quickly in your virtue gave back your pleasing soul, commended to Christ. Therefore, we reflect on your memory with devout praise, O virgin; O blessed Wilgefortis, we request you to pray for us” (Friesen 2001, p. 59). The original Latin can be found in (Acta Sanctorum 1868) (available online at https://archive.org/details/actasanctorum32unse/page/n99/mode/2up accessed on 29 June 2022). The prayer may be found on p. 64 of the book which is volume 32, July part 5, and the section on Wilgefortis begins on p. 50, “De S. Liberata alias Wilgeforte virgine et martyre”. I recognize the difficulty of the language of deformity (deformatam in the original Latin) in this prayer and how this would be harmful to those who identify outside of the sex/gender binary, particularly to intersex people who are told their bodies are ‘deformed’ and need to be ‘corrected’ or ‘fixed.’ |

| 29 | I especially recognize here the importance of allowing transgender people to identify with a gender (woman and/or man) that is different from the one in which they were assigned/raised, as well as all those who choose to not identify with any gender. |

References

- Acta Sanctorum. 1868. Paris and Rome: Jules Moreau.

- Berger, Teresa. 2015. Christian Worship and Gender Practices. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by John Barton. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budwey, Stephanie A. 2018. “God is the Creator of All Life and the Energy of the World”: German Intersex Christians’ Reflections on the Image of God and Being Created in God’s Image. Theology & Sexuality 24: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budwey, Stephanie A. 2020. What We Think is New is in Fact Very Old! In In Spirit and Truth: A Vision of Episcopal Worship. Edited by Stephanie A. Budwey, Kevin Moroney, Sylvia Sweeney and Samuel Torvend. New York: Church Publishing, Inc., pp. 157–68. [Google Scholar]

- Budwey, Stephanie A. 2023. Religion and Intersex: Perspectives from Science, Law, Culture, and Theology. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert, Donald L., and Caryl Daniel-Hughes. 2017. Introduction to the Volume. In The Bloomsbury Reader in Religion, Sexuality, and Gender. Edited by Donald L. Boisvert and Caryl Daniel-Hughes. London: T&T Clark, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, Jheronimus. c. 1497. Saint Wilgefortis Triptych. Bosch Project. Available online: http://boschproject.org/#/artworks/Saint_Wilgefortis_Triptych (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Cherry, Kittredge, and Zalmon Sherwood, eds. 1995. Equal Rites: Lesbian and Gay Worship, Ceremonies, and Celebrations. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, Kittredge. 2021. Saint Wilgefortis: Holy Bearded Woman Fascinates for Centuries. Q Spirit. July 19. Available online: https://qspirit.net/saint-wilgefortis-bearded-woman/ (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- de Jong, F.H., and W.W. de Herder. 2016. Saint Wilgefortis: Sudden Hirsutism to Prevent an Unwanted Marriage. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 39: 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- DeVun, Leah. 2008. The Jesus Hermaphrodite: Science and Sex Difference in Premodern Europe. The Journal of the History of Ideas 69: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVun, Leah. 2021. The Shape of Sex: Nonbinary Gender from Genesis to the Renaissance. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Episcopal Church. 2018. The Book of Occasional Services. Available online: https://www.episcopalchurch.org/files/lm_book_of_occasional_services_2018.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Friesen, Ilse E. 2001. The Female Crucifix: Images of St. Wilgefortis Since the Middle Ages. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan, Siobhan. 2009. Queer Worship. Theology & Sexuality 15: 211–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar de Alba, Alicia, and Alma López. 2011. Our Lady of Controversy: Alma López’s Irreverent Apparition. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- González, Cristina Cruz. 2014/2015. Crucifixion Piety in New Mexico: On the Origins and Art of St. Librada. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 65–66: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, Teresa J. 2016. Slender Man and the New Horrors of the Apocalypse. In Transgender, Intersex, and Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Teresa J. Hornsby and Deryn Guest. Atlanta: SBL Press, pp. 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Creative Mindfulness. 2022. I Am Not a Mistake: A Healing Service for the Queer Soul. YouTube. June 26. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UiQlnCSI0c (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Jasper, Alison. 2005. Theology at the Freak Show: St Uncumber and the Discourse of Liberation. Theology & Sexuality 11: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Patricia Beattie. 2006. Christianity and Human Sexual Polymorphism: Are They Compatible? In Ethics and Intersex. Edited by Sharon E. Sytsma. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky, M.A. 2014. “A Wonderfull Monster Borne in Germany”: Hairy Girls in Medieval and Early Modern German Book, Court and Performance Culture. German Life and Letters 67: 467–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knauss, Stefanie, and Daria Pezzoli-Oligati. 2015. Introduction: The Normative Power of Images: Religion, Gender, Visuality. Religion & Gender 5: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, Harry S., and Hebbel E. Hoff. 1963. Saint Uncumber or La Vierge Barbue. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 37: 523–27. [Google Scholar]

- López, Alma. 2014. Harkness Lecture 2014: “Queer Santas, Holy Violence”-CLGS. Berkely: Pacific School of Religion. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, Peter, Dorothy McCrae McMahon, and Francis Voon. 2016. Order of Service for ‘Lament and Apology Liturgy’ to LGBTIQ. Australian Catholics for Equality. August 13. Available online: https://australiancatholicsforequality.org/prayer-reflections/order-of-service-for-lament-and-apology-liturgy-to-lgbtiq/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Mills, Robert. 2021. Recognizing Wilgefortis. In Trans Historical: Gender Plurarlity before the Modern. Edited by Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov and Anna Kłosowska. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 133–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nightlinger, Elizabeth. 1993. The Female Imitatio Christi and Medieval Popular Religion: The Case of St. Wilgefortis. In Feminine Medievalia 1: Representations of the Feminine in the Middle Ages. Edited by Bonnie Wheeler. Dallas: Academia Press, pp. 291–328. [Google Scholar]

- Povoledo, Elisabetta. 2020. A Long Revered Relic is Found to Be Europe’s Oldest Surviving Wooden Statue. New York Times. June 19. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/19/world/europe/christ-statue-lucca-italy.html (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Procter-Smith, Marjorie. 2013. In Her Own Rite: Constructing Feminist Liturgical Tradition. Akron: Order of Saint Luke. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Sam. 2020. A Saintly Curse: On Gender, Sainthood, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. eFlux Journal 107. March. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/107/318895/a-saintly-curse-on-gender-sainthood-and-polycystic-ovary-syndrome/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Schnürer, Gustav, and Joseph M. Ritz. 1934. St. Kümmernis und Volto Santo. Düsseldorf: Schwann. [Google Scholar]

- Tanis, Justin. 2017. Queer Bodies, Sacred Art. Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. 2021. 1.2 Million LGBTQ Adults in the US Identify As Nonbinary. Williams Institute. June 22. Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/press/lgbtq-nonbinary-press-release/ (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Viloria, Hida, and Maria Nieto. 2020. The Spectrum of Sex: The Science of Male, Female, and Intersex. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Lewis. 2014. Bearded Woman, Female Christ: Gendered Transformations in the Legends and Cult of Saint Wilgefortis. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 30: 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Robin Knowles. 1999. Moving Toward Emancipatory Language: A Study of Recent Hymns. Lanham and London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Budwey, S.A. Saint Wilgefortis: A Queer Image for Today. Religions 2022, 13, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070616

Budwey SA. Saint Wilgefortis: A Queer Image for Today. Religions. 2022; 13(7):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070616

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudwey, Stephanie A. 2022. "Saint Wilgefortis: A Queer Image for Today" Religions 13, no. 7: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070616

APA StyleBudwey, S. A. (2022). Saint Wilgefortis: A Queer Image for Today. Religions, 13(7), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070616