3. Conversing Together

Actions and Values: “We acted. We had to”.

For clergy and faith leaders it is easy to say that we act out of faith, that our actions are (nearly) always informed first and foremost by our understanding of the biblical message. Yet, in the face of a crisis to which government and city officials—even the medical profession, initially—did not respond, responding to the apparent needs of the community came first. In those moments of attending to individuals and families amidst the water crisis, there was something deeper at work. There was an experience of meeting God in those moments. Then later, the actions of helping, advocating, and serving informed biblical interpretation. This is not to say that the theology was not present in the actions, but rather that in highlighting the actions first we can then see what values undergirded those actions.

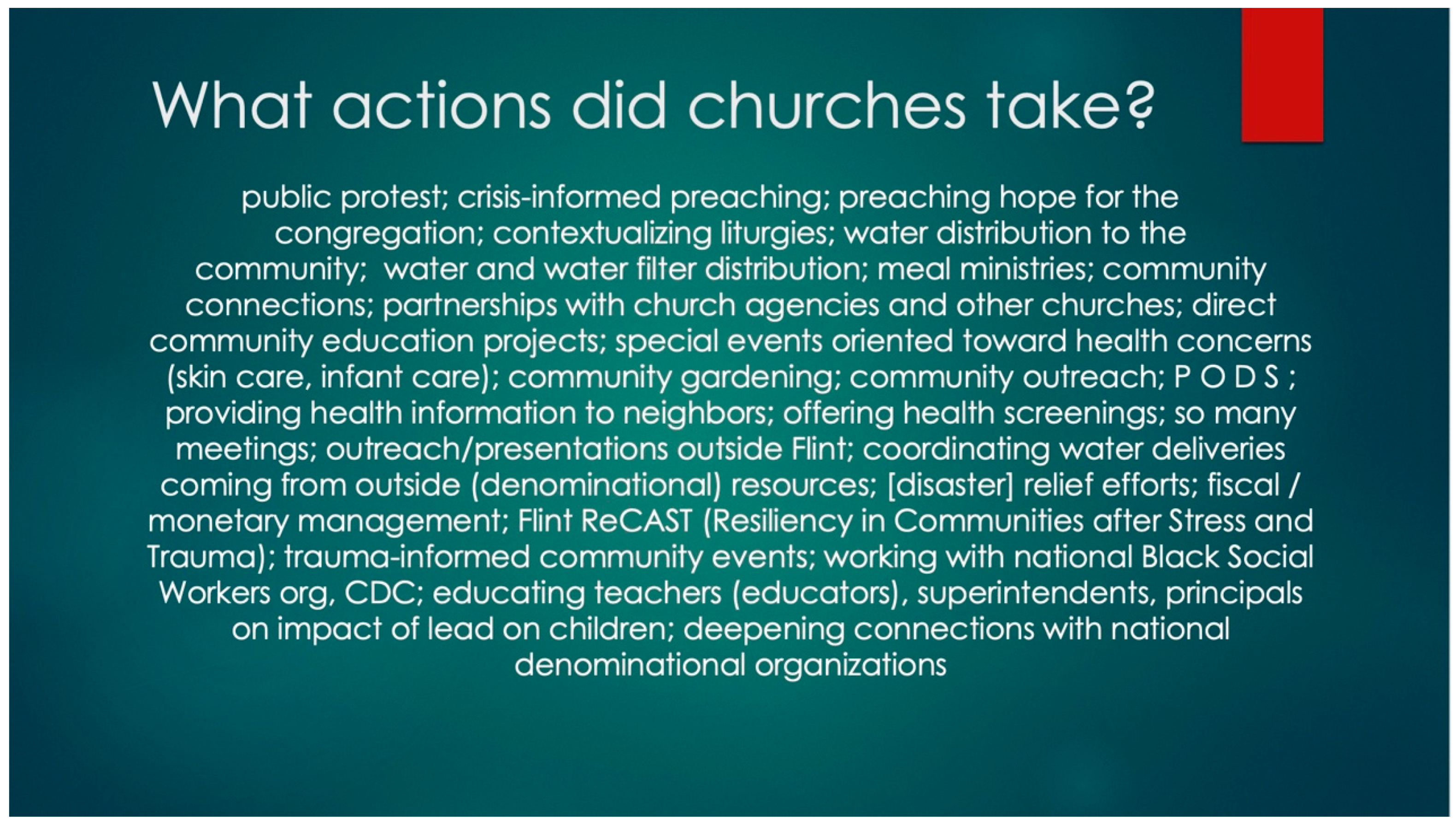

Our first session together had a staggered beginning with folks having to juggle prior commitments and extract themselves from their usual obligations. Once we were all together, though, there was a sense of anticipation and hopefulness around what might come of this communal endeavor. From the initial two project phases, Daley Mosier and Wymer had come up with an extensive list of particular actions faith leaders had taken during the water crisis. We then vetted that list with our co-authors, here (

Figure 1). One of the most notable additions was the great number of meetings that took place, with representatives from a wide variety of government, city, nonprofit, faith-based, and educational organizations. The dynamics of those meetings had made an impression as folks recounted how much time and effort they required. This speaks to a kind of persistence that refuses to leave the conversation until solutions are worked out for the benefit of everyone.

Reflecting on the actions it quickly became apparent that, of all the things listed, how few of them represented individual life—it was all about communal purpose. Traversing the crisis required believing in something bigger than oneself or one’s own community. Much of the work happened in meeting rooms and across tables, with any number of agendas initially walking into the room., and just as water finds its own level, individual egos would eventually disperse for the needs of the greater community. In fact, it was only when everyone in the room was committed to working for the greater good that forward movement was made. The anti-racism piece was significant because Flint is primarily a black community, and emerged in part through partnerships within the city between black churches and those with predominantly white congregations.

Following our discussion on actions, we used an online tool where folks could use a QR code to add text to a word cloud, we compiled a list of “values, commitments, or assumptions” that motivated or inspired the actions. The list included the phrases: “fighting for the weak”, “economic justice”, “human rights”, “reinforce grassroot voice”, “hope”, “representing Christ”, “Social justice”, “preservation of life”, “Justice”, “Responsibility”, “public engagement”, “creation”, “Love”, “Life”, “need for action”, “protecting”, “water is life”, “resilience”, “togetherness”, “love of neighbor”, “Organizing”, “Self-preservation”, “Public leadership”, “Action”, “Environmental justice”, “Community justice”, “kindness”, “Black Lives Matter”; with “Anti-racism” and “community and connection” taking up space in the center in enlarged font. We then took a moment to pause and reflect on the words and phrases. Using a visual tool in this way allowed us to see the three most salient values clearly: anti-racism, community and connection, and justice (with justice encompassing a number of related values) (

Figure 2).

Theological Commitments: Jesus Among the People

Moving on in our conversation, we asked for “a scripture, an image, or practice that you found deeply meaningful during the water crisis”; four passages from the Bible quickly surfaced in our conversation. For Saddler “love thy neighbor as thyself” (Lev 19:18; Mt 19:19; James 2:8) communicated both the need to be concerned for one another, and reminded people of their own self-worth during a time of intense anxiety and persistent gaslighting by public officials. It communicated the need for people to realize that we are all connected with one another, which seems simple, yet, what was happening was, it was the personification of that very scripture.

Moore shared Jesus’ own call to ministry, as recounted in Luke 4:18–20, drawing attention to how Jesus himself was fully engaged in community. Jesus as the model for social gospel ministry attends not only to the physical and practical needs of the community, but also demonstrates to the church today where and how to present hope. The passage asks of the church and of people of faith, how can I get engaged? We lose church when we forget about community. There is a saying in black tradition, “trouble don’t last always”, and, while it is important to give food, and give water, at the same time, where are you presenting hope that we are going to make it through?

6Villarreal leaned into Isaiah 58:9–12 for its water imagery and how it resounds with God’s call of hope. In considering the redevelopment of Flint and the many historical injustices, what does it mean to be the water in the spring of hope—in a place that was parched, in a place with contaminated water, in a place that was deserted, in a place that has no water and to be the one who is the restorer? There is everything in this passage from justice to reconciliation, to restoration, to repair, to seeing that the strength is in the people—it is already here, and to see that God never left.

For Timmons, 2 Corinthians 6:1–4 was a driving force. The call to work together as ministers of grace belied denominational favoritism and made the work ecumenical. The overarching sentiment became, we are people of God and we have to get this done. Churches who let down denominational walls were able to be effective in driving change, including when working with secular nonprofits and governmental agencies.

Reflecting further on the scriptures in relation to the values, it was clear that here was an instance of God’s word incarnate amidst the water crisis. Scripture as an ever-present guide, even at the subconscious level, was made evident in how Flint clergy responded. Clergy found they cannot hide, cannot separate out actions and values from scripture because, as Timmons observed, “your DNA are those scriptures and those scriptures are now your DNA”. Talking about how Jesus is out in the community comes about from reading that in scripture. Then, in a moment of life imitating text, folks live it and see that sense of the Holy Spirit, that sense of God at work. That the scriptures shared were on folks’ hearts as the first thing that came to mind was a remarkable witness and demonstration of how every one of the (preceding) values shared personifies love and God; and because God is love, these things are personified in all the preceding actions as well. As Saddler so eloquently noted, (amidst difficult situations):

We have to see Jesus in everything and in everybody—the kind of seeing that comes from within, the way that God looks at them. Yes, we get discouraged. Yes, we feel like this is completely overwhelming. But because we can see—as in, discerning from the heart, see the depths of things—we can look at a water crisis and still see Jesus.

While it would have been possible (perhaps even a more obvious step) to begin with scripture and still come up with the same values, moving from values to scripture illuminates just how much these particular passages are a part of each person. It is where we are, who we are as Christians first, as people of God, also as ministers, as theologians, and as people of hope and light in the community. The values, the scriptures, all point to who God is, as well, and it is that knowledge (deep knowing) that kept folks going during the water crisis. Taking time to meet together was very grounding; it filled our spirits, encouraged our fellow clergy partners, and offered some dedicated time for reflection. Where we left off on the first conversation set us up well for the second conversation and more directly addressing the theory and practice of baptism in light of the experience of the Flint water crisis.

On Baptism

From the perspective of Daley Mosier and Wymer, we noticed (and found it notable) that our co-authors referenced passages from the Bible when asked for “a scripture, an image, and/or a practice” that carried them through the water crisis. Word and text remain normative modes of spiritual engagement, which appears to be as true for those coming from a sacramental/liturgical background as it is true for those coming from more Pentecostal and Baptist backgrounds. As Wymer walked us back through those passages at the opening of our second conversation, an overarching theme emerged of Jesus among the people. In other words, wherever people are, God may be found—and a distinct edge emerges especially wherever people are experiencing harm, as has been the case in Flint. Similarly, the notion of justice takes on a deeply communal hue. Here the gospel of Luke and the message that Jesus reads in the synagogue, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me …” (Luke 4:18–19) reverberate for clergy both in terms of encountering God’s spirit of grace poured out (reception), and in terms of acting out the call to preach, heal, and mend (vocation). For clergy, the flow between reception and vocation is present whether consciously or unconsciously—a significant observation as we turn to examine baptismal practice.

In order to identify some potential common ground for discussing baptism, Daley Mosier and Wymer began by summarizing ecumenical themes from Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry (

WCC 1982, pp. 1–2). The summary of these themes included: (a) the idea that baptism somehow connects to Christ’s death and resurrection; (b) the idea that baptism connects in some way to conversion, salvation; (c) the idea that baptism connects to the gift of the Spirit in some way, or is related to, in some way—if not as gift—the receiving of the Spirit; (d) this idea that baptism involves being brought into a community, into the body of Christ, or into a community of faith; and (e) the idea that, that shared across a number of traditions, that baptism also is a sign of the future kingdom of God, of an alternative way of being in the world that points God’s order for things and not the order here on earth (

WCC 1982, pp. 1–2). Moving from these themes to each participant’s particular baptismal commitments and experiences allowed us to more easily identify what we held in common as well as what was distinctive.

As we shared our experiences of witnessing folks getting baptized, and recounted times when we have had to make pastoral decisions about baptizing or re-baptizing individuals (whether or not such a thing is officially/denominationally supported), we found ourselves describing similarly related facets of baptism. First, there is the desire for change, for connection, or for belonging that compels folk to approach baptism. In some cases there is a sense that this person really wants to change, they feel a commitment to the process of repentance. Other times it is a recognition of having found a place where they belong that draws them to choose to be baptized—or a desire to be brought into the body of Christ more wholly. Baptism becomes a bridge that connects people to community. In other words, desire for community and desire for God draw folks to the water. Then, there is the baptism itself, when exuberant joy washes over the faces of those having just emerged from the water. A spark of connection with God and others becomes a bond to the larger body of Christ, and now, belonging, accepted, and accountable to a community, the task is to live that baptism into the world, to do the things that ‘church’ is called to do. Baptism is a beginning of a new relationship with God, with oneself, and with others. This threefold experience of baptism can be traced back through the actions and values recounted above; (in the end) baptism leads to action.

For Saddler and her community, baptism is preceded by a process of repentance, where an individual experiences a change of mind, a change of heart, leading up to the act of baptism. The water washes, and the Holy Spirit fills the baptized person, leaving a distinct residue of joy and exuberance. Baptism is the culmination of an express desire to be changed, to be washed clean, and in that encounter with water and Spirit among community, the baptized are met with the joy of new beginnings. The community teaches that when baptism candidates emerge from the water, that is the beginning. The next thing to do is to reach out to other people with this new love. So it is that the desire to change, to be changed, is catalyzed in water and Spirit in order to live out a life that shows love, compassion, service, leadership, and whatever else the baptized persons senses to be their vocation. The inward change, for baptized persons, is directly linked to outward facing love in thought, word, and deed. The experience of joy at one’s baptism is meaningful because it communicates a moment of profound encounter and profound change.

Villarreal shared some observations around folks who discover a sense of belonging in a community—many who had not experienced the same kind of acceptance elsewhere—and it is that sense of community and sense of belonging that spurs their choice to be baptized. Related to this, she shared one of the practical tensions that many within the Lutheran tradition are experiencing: that is, that how often folks find meaning when they come weekly for Holy Communion, which then prompts them to choose to be baptized. That it is through the profound experience of encountering Christ in the Eucharist—among community—that draws folks to the waters of baptism. Traditionally, only baptized persons may receive the Holy Supper. Furthermore, at baptism, the rite itself does not fully reflect the reality of living in such a way that connects baptized persons with the world. For her, the liturgy is very internally focused. The baptismal vows conclude with language about care for others, the world, and works of justice and peace, only after multiple points on individual salvation. This begs the question, how do we live baptism in the world? How do we bring the table to the world? Here, we see an instance where the practice of baptism only hints at what it means to act as a baptized person in the world.

For Timmons, baptism is a twofold action of emulating Jesus Christ, and being brought into the body of Christ. Baptized persons are free to be the hands, the feet, the mouth of Christ—members of the body of Christ here on the earth. This then flows into a sense of accountability and responsibility for the wellbeing of others, as well as a responsibility for acting in such a way that is aligned with what we believe is God’s justice—caring for the poor, the orphan, the widow. To live out one’s baptism is to live humbly, to actively pursue the common good for those beyond the church walls as much as for those within. For his community, baptism is often by individual choice (with baptisms of young children occurring less frequently than older children and adults). Bridging the traditions of baptism by immersion and baptism by pouring or sprinkling, he shared that their church has both a font and a pool. What matters most, though, is the actions and commitment of baptized persons to work for the good of the community; to live out one’s vocation joined with fellow sibling in Christ.

Moore shared with us his shift in perspective on baptism from seeing it merely as an outward sign of an inward change, to reflecting more deeply on how it is through baptism people feel genuinely connected with the church. Having grown up in the Baptist tradition and even when moving into leadership roles, he noticed that baptism itself was rarely a topic of preaching or teaching. Similarly to what Saddler described, though, he noticed people’s excitement when they came up out of the water. Here again, witnessing the lived reality of baptized persons suggests that baptism is the bridge that connects people to community. People feel part of the church body when they are baptized, and when they feel part of the larger body then they feel a need to follow up with action and outreach—because this is what the church does. Caring for others moves from solely an individual responsibility to a shared, communal response.

Wymer posed the question, drawing from what Moore had said earlier, if water can bring us together, can baptism do the same? This is in some ways a difficult question to answer. The water crisis provided a focal point that required a communal effort to address and correct. Yet, as we demonstrate here, that communal effort was undergirded by the values and theological commitments that emerge from living as baptized persons, taking the words of Jesus seriously and acting out of the love of God. As baptized persons we recognize an interconnection across human communities; what affects one directly affects all indirectly. Water as an essential element highlights common needs that cut across denominational, socioeconomic, religious and even political differences.

Further on in our conversation together, Daley Mosier asked the others, “What would you teach people (pastors, ministers, seminarians) about baptism in light of the water crisis, in light of a pandemic, in light of these times of crisis?”

For Villarreal, there is a crucial need for baptism to be taught alongside public leadership. Seminary training needs to include a public leadership course to begin with—one that incorporates a variety of aspects and approaches to prepare folks for more direct community engagement. Just as baptism is discussed in church history courses and theology courses, similarly it needs to be paired with public leadership. There is a vital and essential connection between being baptized and being a leader in the church with the level of responsibility one holds in the public sphere. If we are to be the arms and legs of Jesus in the world, then seminary training needs to take seriously the level of engagement that is required outside church walls.

Moore noted how he is still thinking in crisis mode when it comes to baptizing, and so what he would teach others is: do not be foolishly spiritual. Do not pray over the water and put the people in it anyway; be conscious. Some people have had to wait over a year to be baptized, but during the pandemic they have been practicing social distancing. Keeping the overall needs of the community requires attending to physical, material realities—such as avoiding toxic water in a water crisis, and keeping safety measures in a pandemic. Do not compromise those things in the name of being (foolishly) spiritual.

Saddler summed up the sentiment with the phrase, “don’t be so heavenly minded you’re of no earthly good”. We have to be cognizant of the body, the soul and the spirit. If the best practical approach to keep people physically safe is to use filtered water, bottled water, or to change the timetable of when baptisms occur, then we do so as a way of continuing the mission of Jesus Christ. Doing so is an expression of love for the people and serves as a witness to who God is—God is love.

Timmons encourages ministry leaders and pastors to hold fast to their vocation and sense of call from God. In light of that, do not give up the power and influence and responsibility to the community when trouble hits. Serving in the church is a holy calling. Baptizing people is a sacred act. A significant aspect to Christian leadership is to share Christ and serve as a leader with a sense of deep trust that God provides internal and external resources for such a role, and so it is important that we know who we are, and that we know that we are called, and we continue to operate amidst difficult circumstances.

4. Baptismal Solidarity: Observations

“Flint is still broken”. Media attention has long since turned its eyes away from the town of Flint, Michigan, yet the impact of toxic water continues to percolate throughout the communities. Long term impacts of exposure to lead in infants and children have begun to surface as legal settlements and court battles make their way through belabored systems and broken structures. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the water crisis appears all but buried while residents continue to wonder if the water is really safe and leaders question where their former collaborators and partners went. Reflecting together on the actions, values, commitments, and practices that emerged from this specific instance of environmental racism, we constructed a baptismal ethic of solidarity that is grounded in the lived realities of impacted communities and that contributes both to theological discourse and ecclesial practices.

Contrary to a “common sense” definition of solidarity, which has the potential to “[dissolve] into a cliché, an empty sign signifying nothing authentic or essential”, theologian M. Shawn Copeland observes, “A theological understanding of solidarity realizes itself in intelligent and effective compassionate action, in doing, in discipleship” (

Copeland 2018, p. 143). She continues, “What does solidarity require? Compassionate action… Compassionate action entails attentive consciousness of others, informed and critical awareness and understanding of others and their condition, and acts with them to resist unjust suffering, to liberate and heal the human spirit, and to repair breakdowns in the natural, religious, cultural, social, and interpersonal realms” (

Copeland 2018, p. 144). Copeland’s definition maps well onto the experience of clergy and leaders of communities of faith during the water crisis as many found themselves having to advocate for the needs of the people, learn strategies for communicating with local and state governments, develop public leadership skills, and a myriad of other ways to resist injustice and continue to care for congregations and communities. Many found themselves examining their own understanding of baptism—what it is, what it means—during a time when the water was a sign of dehumanization and environmental racism. The call to pastoral care rapidly expanded outward as folks recognized a need to act beyond the church walls.

In defining solidarity, liberation theologian Jon Sobrino offers a distinction between “aid” and “solidarity”. He notes, “aid (especially official, international aid) can be a quasi-mechanical, unilateral reaction immediately after the catastrophe. It can be a way of soothing the conscience, maintaining social control, and evading the responsibilities of justice, because it will not challenge us to overcome selfishness, especially structural selfishness” (

Sobrino 2004, p. 18). In contrast, “solidarity means not only giving but self-giving… Solidarity means

letting oneself be affected by the suffering of other human beings, sharing their pain and tragedy” (

Sobrino 2004, p. 19, emphasis in the original). Sobrino, here, is reflecting on catastrophic events that were easily recognizable as tragedies. The catastrophic change to the water in Flint, however, was contested until a state of emergency was officially declared, twenty months after the fact. This form of “slow violence” calls for a contoured form of solidarity that sees outside aid as a form of love—especially prior to official rulings—and that can hold together expressions of solidarity across neighborhoods, cities, and bioregions (See

Nixon 2011).

The baptismal ethic constructed out of our conversation connects with our understanding of baptism in that it demonstrates how baptized persons responded in a crisis to the needs of a community beyond the congregational directory list, and why. Out of the particularities of the Flint water crisis, we have constructed something that could be applicable in a great variety of places and under any number of circumstances. The acute suffering brought on by this particular crisis should not overshadow the more pervasive impacts of systemic racism and slow violence of mundane ecological degradation. Rather, it should shine a light on dirty water everywhere. Through this project we identified localized and inter-regional facets to solidarity—localized, in that, clergy and community leaders developed connections across neighborhoods and ecclesial lines in order to organize aid and advocacy efforts; and inter-regional, in that, clergy and community leaders developed connections beyond the city limits of Flint and beyond the Flint River watershed.

The call to baptismal solidarity begins the moment we emerge from the baptismal pool or font having received the cleansing waters of new life and the gift of the Holy Spirit, and it is renewed with each baptism we witness. Walking out that call means that we embrace our responsibility to one another to pursue the common good, particularly in times of trouble and in crisis. Steeped in the Jesus tradition and instructed by the gospel stories, we are sent out to offer Jesus in the form of prayer and truth-telling words; grace and love manifest in actions for the sake of others, just as Jesus taught. To rely solely upon those who are most impacted, or who appear most committed to changing systems and the status quo is to relinquish our responsibility to this earth and the communities in which we live. God is love, and love is an action.