Crisis, Solidarity, and Ritual in Religiously Diverse Settings: A Unitarian Universalist Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Ritual Theory

2.1. Occasional Religious Practice in Times of Crisis

2.2. Crisis: Disaster Ritual

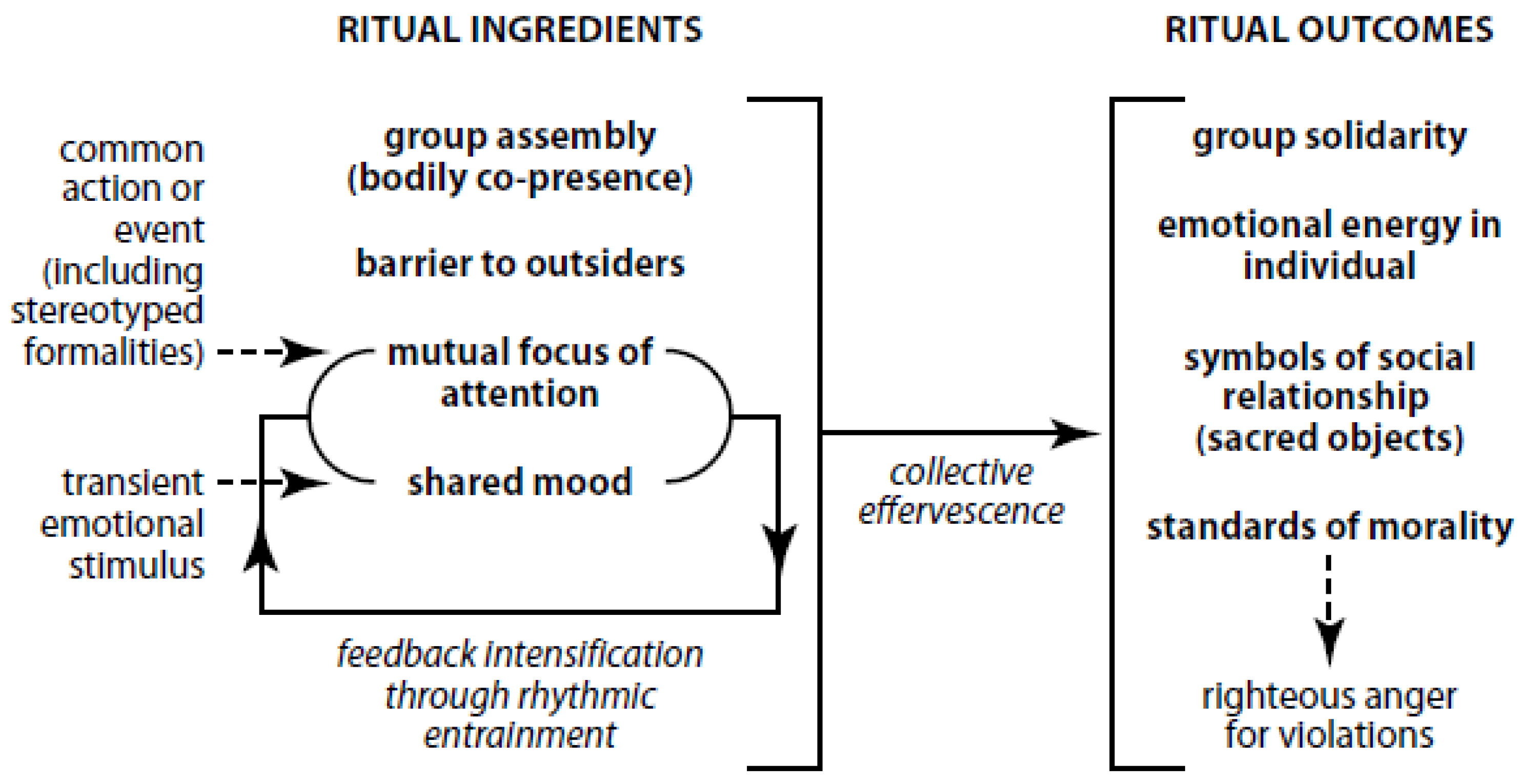

2.3. Solidarity: Interaction Ritual Chains

3. Case Study: First Unitarian Church

3.1. Unitarian Universalism

3.2. First Unitarian Church

4. Ritual Description: “Joys and Concerns” and “Meditation”

4.1. Trusted Structures

The leader then moves to the area where sharing takes place: a table with a microphone on a pillow, a basket of candles, and a bowl of sand to hold the lit candles. Various objects may be used seasonally in place of candles, such as colourful wooden eggs in the spring, folded origami objects in the summer, or stones in the autumn. The leader continues:We demonstrate our compassion in many ways, by offering rides, or rooms, or by listening to each other’s stories. Some of this we do directly, in person, or by phone, or Facebook; others are so important that we want to share them in this sacred space.

At this point, sharing begins. Individuals or pairs come forward, share with the community, and light a candle. The content of what is shared is discussed in detail below. Sharing is followed by a time of silent meditation, framed by the worship leader:I will light the first candle from our chalice, symbolically shining the illumination of our faith tradition into the tragedies and triumphs of our lives. If you have a significant event to share, I invite you to come forward and light a candle; please hold the microphone close to your mouth and share your name and, if you are willing, the reason for your candle.

The community sits together in silence. Most weeks there are seven breaths, occasionally the leader calls for five. The worship leader moves out of silence into a spoken meditation:I invite us into a short meditation. As you wish, please get comfortable in your seat. If you prefer, you could soften, or close, your eyes. Let us inhabit a period of shared awareness, as we take seven deep breaths together…

Specific items may be mentioned, often associated with the theme of worship or related to world events, such as a refugee crisis or American politics. When the pastor is leading the spoken meditation, it always concludes with the same words:Becoming aware of that moment between exhale and inhale… and in that timeless instant, allowing ourselves to be at one with the powerful, to be at one with the impoverished; we notice that we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses; our memories and imaginations are full of people we have known, or do know, or somehow know of…

This looks and sounds a lot like what theist traditions call “prayer”; in fact, the pastor calls the spoken meditation “prayer” in his personal notes. However, the word “prayer” is not used in the order of service and is rarely spoken in worship.We desire enough food, and shelter, and peace of mind for all beings this day; we pledge ourselves in pursuit of this goal. Praise for living. So may we be.

4.2. Shared Stories

4.3. Embodied Symbols

The ambiguity of these symbols allows them to function differently for participants with different beliefs. For example, a candle could point to the light of knowledge for an atheist, the light of Christ for a Christian, and light in the darkness of winter for an Earth-based practitioner.They are extraordinarily flexible and adaptable to multiple social uses. Such symbols can work in different ways for different people simultaneously, depending on their sensitivity to different valences.

5. Ritual Analysis

5.1. Solidarity: “Joys and Concerns” and “Meditation” as an Interaction Ritual Chain

- Bodily co-presence. The participants are physically gathered.11 Those sharing present themselves physically before the group. The experience of bodily co-presence is amplified in the action of taking seven deep breaths together.

- Barriers to outsiders. Worship is open to all who choose to attend. However, the group is defined by internal norms and expectations. There is a sense that the worship context is set apart from other environments. For example, on one occasion a participant asked the community to keep a concern “within the walls of the sanctuary”.

- Mutual focus of attention. The community is intently focused on listening to the story of the individual sharing, observing the action of the sharer with the symbol, and participating in the meditation, including the deep breaths. Storytelling and embodied symbols are both highly engaging points of focus. Furthermore, the participants play a primary role in this interaction ritual, which strengthens their experience of it.

- Shared mood. The mood of the sharing time reflects the emotional content that is shared. This is evident in the physical and audible responses of the congregation in laughter, sympathetic sighs, and applause.

- Individual emotional energy. For instance, there is a sense of release following sharing a concern or the boost that comes from being applauded for an accomplishment. The importance of the ritual to the participants may reflect the emotional energy they acquire from it.

- Symbols of social relationship. Symbols include the objects representing joys and concerns that are prominently placed at the front in the worship space, as well as the less tangible symbol of shared breath. It is noteworthy that a shared image of God is not a central symbol in this religious ritual at First Unitarian, nor is there a common conception of this practice as “prayer”.

- Standards of morality. The community’s commitments to mutual support and social justice are evident both in what is shared and how the community responds to sharing. This is evident in the immediate response to sharing, such as applauding certain personal choices or local social programs, and in the ongoing activism of the community.

- Social solidarity. Central to this analysis, the ritual produces a feeling of membership and commitment to shared symbols and goals. This is evident in what and how the participants share, the immediate response of those gathered, and in how the participants follow up with one another over time. The way the practice of sharing “Joys and Concerns” and “Meditation” fosters solidarity may also account for its centrality in the worship experience of the participants at First Unitarian.

The structured ritual storytelling and symbolic action of the “Joys and Concerns” and “Meditation” likewise fosters solidarity that does not depend on shared belief in a diverse community that includes both theists and nontheists. It resonates with Heider and Warner’s argument that “Social solidarity, the conviction on the part of individuals that they are part of a collectivity larger than themselves, is grounded in physically involving, emotionally compelling group rituals” (Heider and Warner 2010, p. 77). The capacity for the sharing and meditation ritual at First Unitarian to produce solidarity in the absence of common beliefs is significant in increasingly theistically and religiously diverse contexts, especially because this is also a ritual response to crisis.Solidarity does not necessarily mean that they come to agree with one another. … Powerful solidarity does not rest on, or even necessarily produce, common ideas or common emotions. Solidarity is, instead, a matter of common identity, a conviction that we share with others ‘something in us that is other than ourselves’.

5.2. Crisis: “Joys and Concerns” and “Meditation” as a Ritual Response to Crisis

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A similar list can be found in Handbook of Disaster Ritual (Hoondert et al. 2021, p. 5). |

| 2 | Several studies have applied Collins’ theory to responses to disasters, although these responses have not primarily been in the form of explicitly religious rituals (Rigal and Joseph-Goteiner 2021; Hawdon and Ryan 2011; Massey 2013; Høeg 2015). |

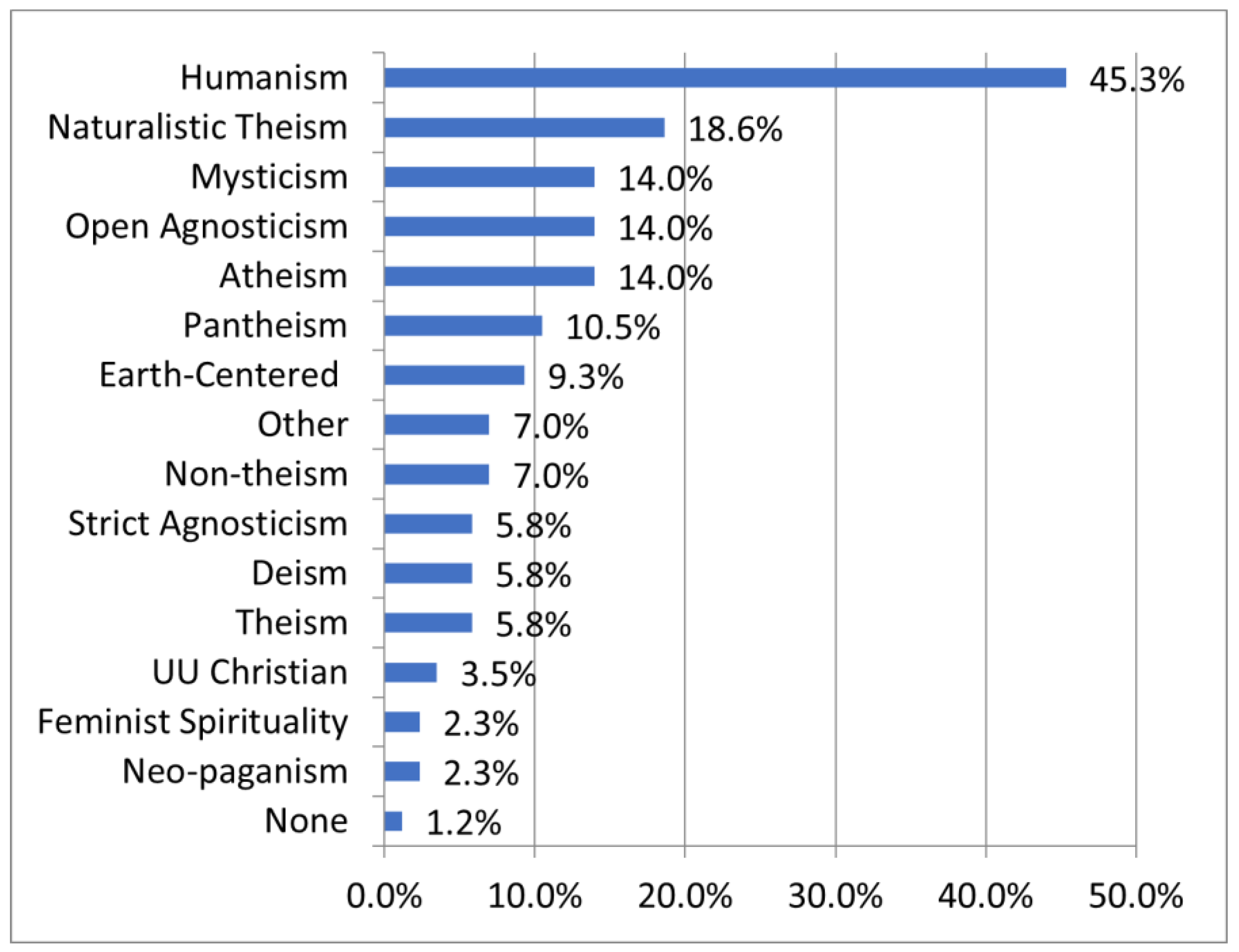

| 3 | A 1999 survey allowed Unitarian Universalist respondents to select multiple labels to describe their religious identity; on average, they chose 3.66 labels. The largest group was Humanist at 54.4%, agnostic was second at 33%, followed by Earth-centered at 30.6%. Atheists were next at 18%, Buddhists followed at 16.5%, and both Christians and Pagans came in at 13.1%. Various other traditions were also represented. Other labels respondents could select included: Muslim, Quaker, Deist, Theist, Taoist, Pantheist, Gnostic, Hindu, and Rationalist (Casebolt and Niekro 2005, p. 238). |

| 4 | Seven Principles: (1) the inherent worth and dignity of every person; (2) justice, equity, and compassion in human relations; (3) acceptance of one another and encouragement of spiritual growth in our congregations; (4) a free and responsible search for truth and meaning; (5) the right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large; (6) the goal of world community, with peace, liberty, and justice for all; and (7) respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part (Unitarian Universalist Association 2022b). |

| 5 | First Unitarian Church conducted surveys of its congregation in 2007 and 2012. The 2012 survey had 85 respondents. Eighty-five percent of the respondents were formal church members and 15% were “friends”. Fifty-nine percent of the respondents had been associated with the congregation for 11 or more years. Sixty-three percent had been Unitarians for 11 or more years. |

| 6 | I conducted ethnographic research at First Unitarian Church, South Bend from January to November 2016; this included attending worship and community events, semi-structured interviews with the pastor, and numerous informal conversations with community members. Orders of worship and detailed scripts provided by the pastor were also subjected to analysis. I am grateful to the leaders and members at First Unitarian Church for welcoming me and giving me permission to name them as collaborators in this research. This research was reviewed and approved by the University of Notre Dame IRB. |

| 7 | Only one of the twenty-five Sunday worship services that I observed did not include the opportunity to share joys and concerns. This service was intended to echo the form of worship at the Unitarian Universalist General Assembly. |

| 8 | Rev. Chip Roush served as the minister of First Unitarian Church, South Bend at the time of this study. He has given permission to name him and share his words. |

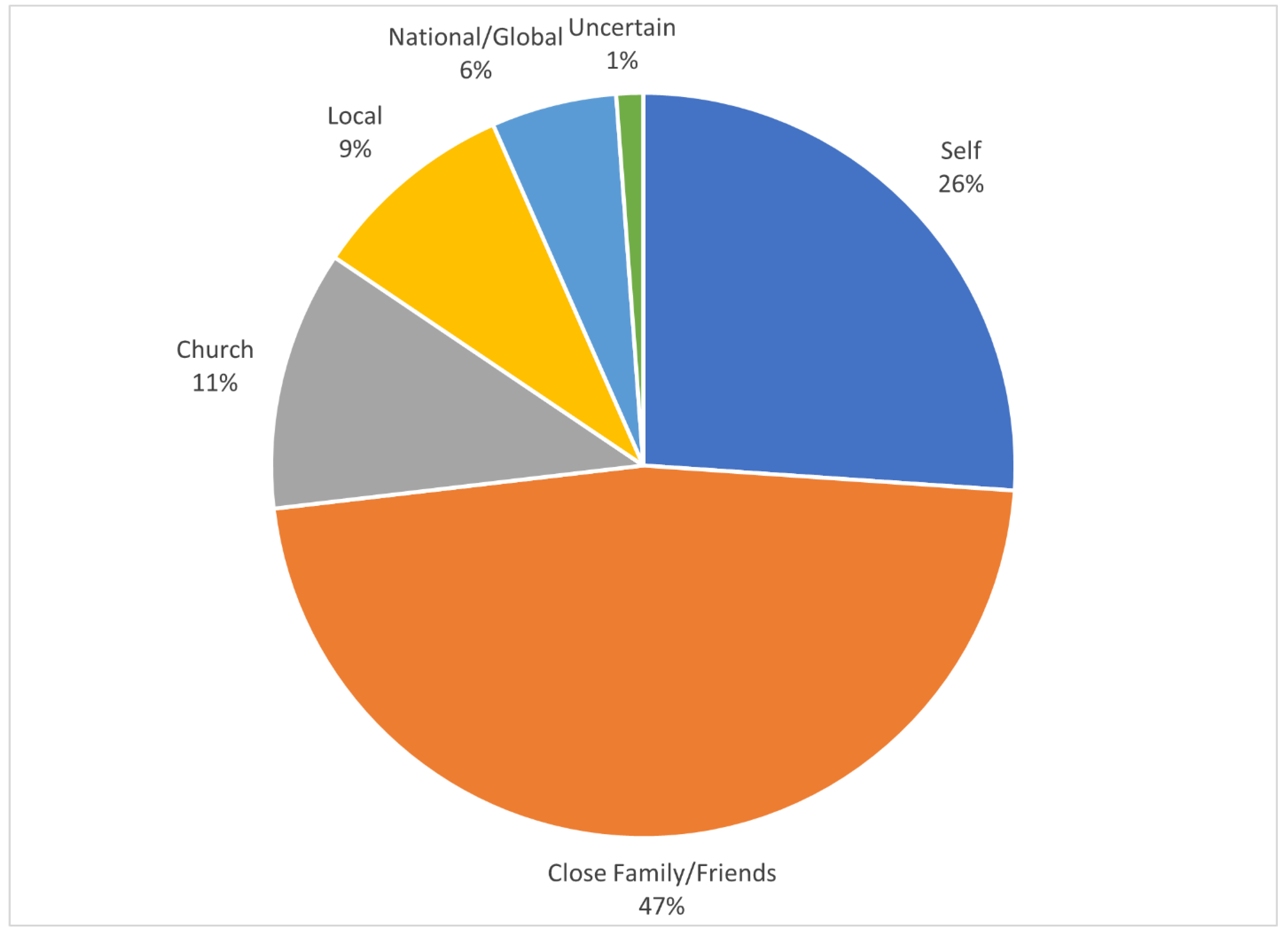

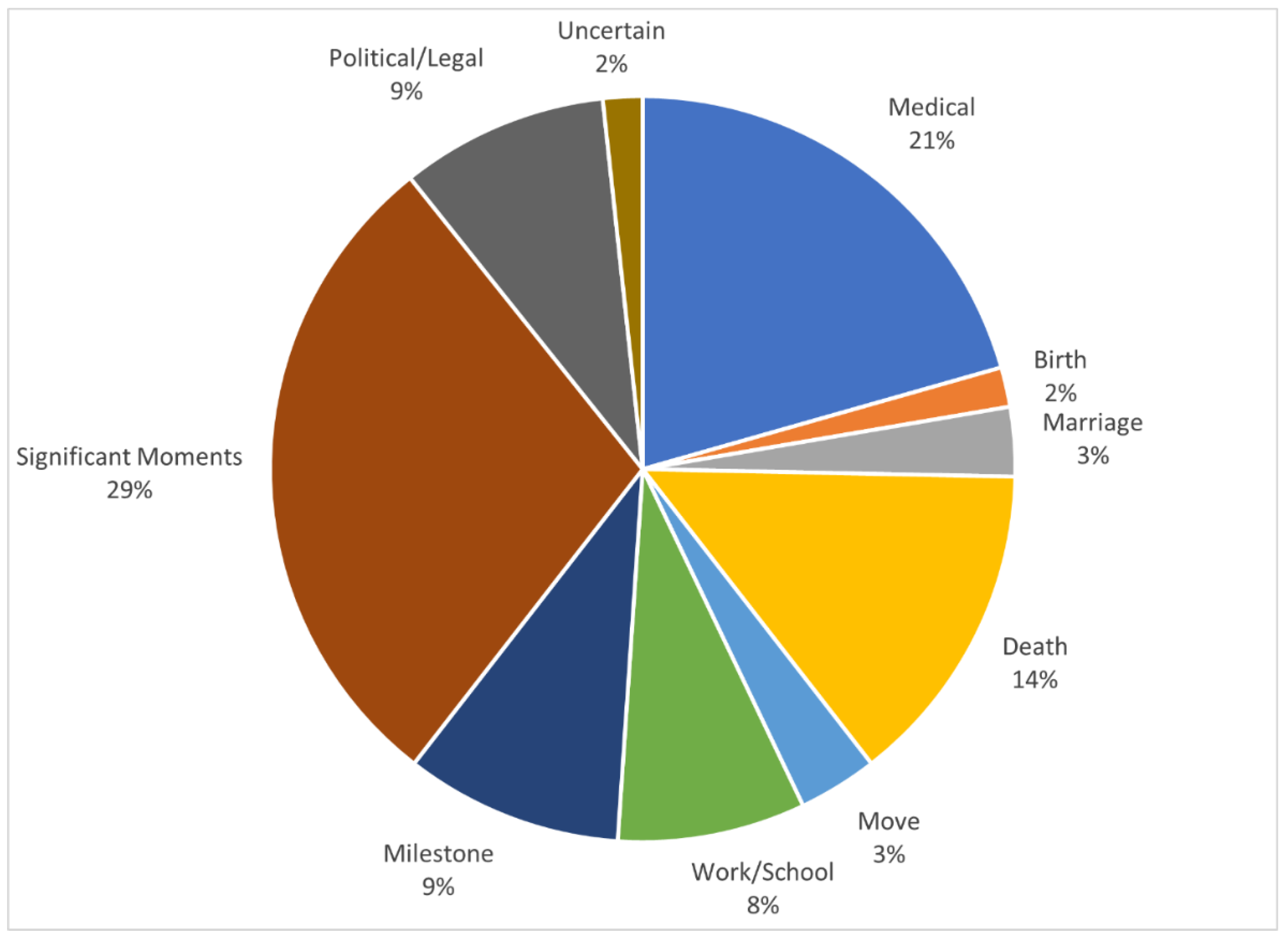

| 9 | A sharing consists of an individual or group coming forward. Sharings frequently include more than one item. |

| 10 | A single sharing may be coded in multiple categories, especially when the participants mention more than one item when they come forward to share. |

| 11 | There is a growing literature related to how interaction rituals function in online environments, although this is beyond the scope of this study, which centers on an in-person ritual (DiMaggio et al. 2018; Collins 2020). |

References

- Bell, Catherine. 1997. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casebolt, James, and Tiffany Niekro. 2005. Some UUs are more U than U: Theological self-descriptors chosen by Unitarian Universalists. Review of Religious Research 46: 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Randall. 2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Randall. 2020. Social distancing as a critical test of the micro-sociology of solidarity. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 8: 477–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C-SPAN. 2016. President Obama Remarks in Orlando, Florida. Available online: https://www.cspan.org/video/?411255-3/president-obama-makes-statement-meeting-orlando-victims-families (accessed on 31 December 2017).

- DiMaggio, Paul, Clark Bernier, Charles Heckscher, and David Mimno. 2018. Interaction ritual threads: Does IRC theory apply online? In Ritual, Emotion, Violence: Studies on the Micro-Sociology of Randall Collins. Edited by Elliot B. Weininger, Annette Lareau and Omar Lizardo. New York: Routledge, pp. 81–124. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, Scott. 2019. Religious Interaction Ritual: The Microsociology of the Spirit. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, Scott. 2021. Effervescence accelerators: Barriers to outsiders in Christian interaction rituals. Sociology of Religion 82: 357–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1995. Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Karen E. Fields. New York: The Free Press. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Todd. 2020. Whose bodies? Bringing gender into interaction ritual chain theory. Sociology of Religion 81: 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawdon, James, and John Ryan. 2011. Social relations that generate and sustain solidarity after a mass tragedy. Social Forces 89: 1363–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, Anne, and R. Stephen Warner. 2010. Bodies in sync: Interaction ritual theory applied to Sacred Harp singing. Sociology of Religion 71: 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høeg, Ida Marie. 2015. Silent actions—Emotion and mass mourning rituals after the terrorist attacks in Norway on 22 July 2011. Mortality 20: 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hoondert, Martin, Paul Post, Mirella Klomp, and Marcel Barnard. 2021. Handbook of Disaster Ritual: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Cases and Themes. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sarah Kathleen. 2021. Occasional Religious Practice: An Ethnographic Theology of Christian Worship in a Changing Religious Landscape. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Margry, Peter Jan, and Cristina Sánchez-Carretero, eds. 2011. Grassroots Memorials: The Politics of Memorializing Traumatic Death. New York: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Kate V. Lewis. 2013. The power of interaction rituals: The student volunteer army and the Christchurch earthquakes. International Small Business Journal 31: 811–31. [Google Scholar]

- Post, Paul, Ronald L. Grimes, Albertina Nugteren, P. Pettersson, and Hessel Zondag. 2003. Disaster Ritual: Explorations of an Emerging Ritual Repertoire. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Rigal, Alexandre, and David Joseph-Goteiner. 2021. The globalization of an interaction ritual chain: “Clapping for carers” during the conflict against COVID-19. Sociology of Religion 82: 471–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenbuhler, Eric W. 1998. Ritual Communication: From Everyday Conversation to Mediated Ceremony. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tavory, Iddo. 2013. The private life of public ritual: Interaction, sociality and codification in a Jewish Orthodox congregation. Qualitative Sociology 36: 125–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Alan. 2016. Worldwide Vigils and Memorials for Orlando Victims. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2016/06/worldwide-vigils-and-memorials-for-orlando-victims/486782/ (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Time. 2017. Watch the Orlando Pulse Nightclub Shooting Anniversary Service for Survivors and Families. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1P-jH2NiCrw (accessed on 31 December 2017).

- Turner, Victor. 1967. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Unitarian Universalist Association. 2022a. Sources of Our Living Tradition. Available online: https://www.uua.org/beliefs/what-we-believe/sources (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Unitarian Universalist Association. 2022b. The Seven Principles. Available online: https://www.uua.org/beliefs/what-we-believe/principles (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Walsh, Andrew. 2002. Returning to Normalcy. Religion in the News. Available online: https://www3.trincoll.edu/csrpl/RINVol5No1/returning%20normalcy.htm (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Wellman, James K., Katie Corcoran, and Kate Stockly. 2020. High on God: How Megachurches Won the Heart of America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, James. 1989. Protestant Worship: Traditions in Transition. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- Wollschleger, Jason. 2012. Interaction ritual chains and religious participation. Sociological Forum 27: 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollschleger, Jason. 2017. The rite way: Integrating emotion and rationality into religious participation. Rationality and Society 29: 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, S.K. Crisis, Solidarity, and Ritual in Religiously Diverse Settings: A Unitarian Universalist Case Study. Religions 2022, 13, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070614

Johnson SK. Crisis, Solidarity, and Ritual in Religiously Diverse Settings: A Unitarian Universalist Case Study. Religions. 2022; 13(7):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070614

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Sarah Kathleen. 2022. "Crisis, Solidarity, and Ritual in Religiously Diverse Settings: A Unitarian Universalist Case Study" Religions 13, no. 7: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070614

APA StyleJohnson, S. K. (2022). Crisis, Solidarity, and Ritual in Religiously Diverse Settings: A Unitarian Universalist Case Study. Religions, 13(7), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070614