Abstract

Some Christian texts, and especially hagiographic and hymnographic ones, record a miraculous phenomenon at the violent deaths of several martyrs: from the beheaded bodies, milk flows instead of blood. After a superficial reading of the biographical passages in the synaxaria and iambic stichoi recorded in the Menaia, we can identify at least ten such cases, among which we find well-known saints, such as Apostle Paul and St. Katherine. This article attempts to revisit this unwonted topos of Christian literature, and to list its occurrences in the liturgical texts of the Orthodox Church and Acta Sanctorum.

“I have not found a more exciting, more extraordinary reading than the Lives of the Saints. No sensational fact reported today by the press or television exceeds in novelty and sensational what I have already read and learned from the lives of the saints”.Virgil Gheorghiu, Pourquoi m’a-t-on appele Virgil? (1968)

1. Introduction

At the beginning of 2019, German physicians consulted, in the emergency room of the Uniklinik in Cologne, a patient whose blood had turned milky white and thicker than normal. Tests showed that this thickening of the blood, as well as the abnormal color, were the result of an extremely high level of triglycerides. More precisely, 18,000 mg/dL of triglycerides were found, which is 36 times more than what is already considered a very high and dangerous level (500 mg/dL, while the normal value is 150 mg/dL). Therefore, the diagnosis made by the doctors was hypertriglyceridemia: a condition that is manifested by high levels of fatty triglyceride molecules in the blood. The case of the patient who had “milk instead of blood” made history in the medical world, being the first of its kind ever recorded by clinical research (Koehler et al. 2019, pp. 142–43).

However, Christian texts record this symptom a few times—without it necessarily being an indicator of the same disease—when recounting the martyrdoms of several saints. Upon a superficial reading of the biographical passages from the synaxaria and The Lives of the Saints, we can identify at least ten such cases, among which we find well-known saints, such as St. Paul the Apostle (29 June) and Catherine of Alexandria (25 November). Each time, the “milk” that flows from the martyr’s body (instead of blood or being accompanied by blood or water) has a miraculous character, and it acquires a special meaning in the hagiographic account, becoming an unwonted topos in the Christian hagiography and hymnography.

Although in the last century, a series of studies have been carried out on this subject, they approach the motif from a folkloric (Barry 1914), artistic (Pixley 2012), literary (Harney 2008) or historical (Ghilardi 2012) point of view, distancing themselves from the theological implications and subordinating the theme to a broader cultural framework. Therefore, the purposes of the paper are to underline some of the theological meanings, and to update the list of known sources that mention this phenomenon in order to overcome a fragmented and biased approach.

2. “Milk Flowed Instead of Blood”—The Evidence from the Menaia

In the Eastern Orthodox Tradition, this recurring motif can be identified after a brief survey of the Menaia, where a series of martyrs can be found whose violent deaths are associated with this “symptom” (Table 1).

Table 1.

References in Synaxaria (Menaia).

The occurrence of this phenomenon is mentioned mainly in the Synaxarion of the day. With one exception1, the phenomenon is not found in the rest of the other hymnological creations: stichera, troparia, canons, kontakia, ikos. But sometimes the apparition of milk at the moment of a martyr’s beheading is surprised by the iambic verses that precede the synaxaria in the Menaia (the edition published by Bartholomew the Imbrian from Kutlumush, Venice, 1889) (Table 2).

Table 2.

References in Stichoi (Menaia).

In order to establish a repertoire of this topos in the Eastern Tradition, and to better observe how important this motif of the appearance of milk is in the economy of martyrdom, it is also required that we identify the mentions made in the Great Synaxarion of the Church of Constantinople (Synaxarion periechon holou tou eniautou tōn hagiōn kai tōn hosiōn en syntomō ta hypomnēmata) (Delehaye 1902), where references can be found to this type of miracle for several saints (Table 3).

Table 3.

References in the Great Synaxarion.

3. Acta Sanctorum

The text of the Synaxaria mentioned in the Menaia is generally further developed in (or, rather, is a synthetic abstract of) other extended hagiographic creations in the form of the Lives and Passions of the saints. Thus, references to this miraculous event can especially be identified in the hagiographic dedicated texts. Among these testimonies, we should remember the results of Barry’s study—written a century ago—where he listed, along with some of the martyrs already mentioned, a group of further references in the Coptic hagiography (Table 4) regarding the appearance of milk (Barry 1914, pp. 560–61).

Table 4.

References in Coptic hagiography.

Further echoes of the phenomenon are to be found in the collection Legenda aurea, compiled around 1260 by the Dominican monk Jacob of Voragine (1230–1298), who apotheotically concludes some of the passiones, recording this miracle for Saint Catherine, Saint Victor, Apostle Paul and Saint Christine.

The occurrences of this topos were not as rare as thought, as we can see from the list compiled by Giovanni Bonifacio Bagatta at the end of the 17th century in a special chapter: Sanguis in lac mirabiliter conversus (Bagata 1695, p. 283), where he mentions the following martyrs: Apostle Paul (29 June), Sebastiana (16 September), Acacius (28 July), Victor (11 May), the women from Sebastia (3 February), Menignus (15 March), Martina (1 January), Baudelius (20 May), Catherine (25 November), Christine (24 July), Secundina (15 January), Aemilianus (28 January), Antiochus (16 July), Panteleimon (27 July), Eupsychius (7 September) and Pompeius (10 April). Still, Bagatta left his list open: “similia et al. iis martyribus evenete”.

Other important examples are mentioned by the Bollandists in their monumental hagiographic collections Acta Sanctorum (Table 5) and Analecta Bollandiana (Table 6).

Table 5.

References in Acta Sanctorum (AASS).

Table 6.

References in Analecta Bollandiana (AB).

It is obvious that some of the texts have a similar or even identical structure, they are closely related, they are using a common template, or they are simply duplicates. Such a resemblance could be seen between the Passio Sanctae Aekaterinae (25 November) and the Vita Sanctae Martinae (1 January), or in the Vita Sanctae Secundinae (15 January). Phillips Barry considered that the two vitae are closely connected, as well as the lives of St. Panteleimon and Aemilianus of Trevia (28 January)/Aemilianus of Armenia Minor, which follow the same scenario, with only the name, location and a few minor details changed (Barry 1914, p. 567). Even more obvious is the reference to the seven women martyrs mentioned in both the passiones of St. Blase (3 February) and St. Irenarchus (28 November) (Garitte 1955).

Some researchers are tempted to consider the systematic literary testimonies as a later topos introduced by the Bollandists in close connection to the “archeologic” findings of relics consisting of different kinds of vials with martyrs’ blood and milk (ampullae sanguinis) discovered by their fellow Jesuits. According to Massimiliano Ghilardi (2012, p. 1220),

“the archaeological discoveries are authoritatively confirmed in literary sources and literary sources are faithfully reflected in archaeological discoveries. But why, as we have already wondered, is there such an imposing and prolonged explosion of the white-blooded cult of martyrs in the early modern age?”

He considers this congruence of evidence too convenient: the great number of references (ancient passiones) published in Acta Sanctorum should prove a more pragmatical objective, which is, namely, to legitimize and authenticate the relics found (archaeological inventiones) in the Roman catacombs during the 16th and 17th centuries, which were the “the tangible and indisputable proof of the apostolicity of the Church of Rome, rubricata sanguine sanctorum” (Ghilardi 2012, p. 1221).

But these references to the martyrs’ “lactation” are quite old, and they appear in different Christian traditions based on a common belief in the truthfulness of the phenomenon. For example, a similar case is reported by another vita, which is part of the Georgian hagiographic tradition (prior to the seventh century): the Martyrdom of St. Philotheus of Antioch (29 January), where we find the following text:

The soldiers and executioners looked into his face and saw that it was like of an angel of God, and they were frightened by the glory, given to him from God. Then two of them came near and pierced his sides with swords. And from his sides came blood and milk (§8) (Rogozhina 2019, p. 327).

The Coptic version of the same vita (seventh century) differs a little when it comes to this final detail:

But two of them (the soldiers) pierced the blessed one in his sides: one in the right side and the other one in the left. And from his sides came water and blood and milk (Rogozhina 2019, p. 359).

Thus, we should exclude the confessional bias of the Jesuits, at least in this case.

Being hagiographic and hymnographic creations par excellence, with a clear doxological and didactic character, these passages can be regarded with some hesitation, precisely because they would have sprung from an excessive piety that could distort the facts out of the sincere desire to render the biography of “God’s servants” in the most convincing way possible and, therefore, excessively decorated with miraculous details.

On the one hand, in most cases, the phenomenon is mentioned in passing, and the insertion of the topos does not seem to be anticipated by any preparatory element. On the contrary, the sudden appearance, without further insistence on this miraculous fact and the impact that it has on the assistance, indicates the spontaneous/natural character of the event in the narrative structures of the vitae and passiones.

On the other hand, it is obvious that some texts are duplicates or are using elements from previous hagiographic creations. It is not possible to determine with certainty the reason behind the addition of this motif, or whether the martyr’s “lactation” represented the key element of these duplicates or was borrowed with the rest of the original story. Actually, the possibility should not be ruled out that the appearance of the topos may be a consequence of the taking over of the entire hagiographic template (i.e., Panteleimon) used to complete, mutatis mutandis, unknown aspects of a saint’s biography (Aemilianus of Trevia), just as in the case of the Byzantine vita of Maximus the Confessor, inspired by the “life” of Theodorus Studita (Lackner 1967, pp. 294–95).

But the verification of these texts’ veracity does not represent the objective of the present investigation, and therefore we should strictly limit ourselves, for now, to the content and the message pursued, without insisting on the authenticity of the source, manuscript history or critical interpretations. The purpose of this material is, first, an attempt to identify the occurrences of this topos in the cult of the Church.

In a recent article, Eva Kovacheva stated that there are 40 saints whose lives describe that, in their martyrdom deaths from the wounds of their bodies, and especially when they were beheaded, milk was flowing instead of blood. Of the recorded cases, 20 were women and 20 were men, of different ages. According to their passiones and vitae, they lived in the first four centuries of the Christian era, but there are also three exceptions of martyrs in the 5th, 7th and 11th centuries (Kovacheva 2018, p. 79).

It is quite obvious that this phenomenon did not end with Late Antiquity. Phillips Barry and Eva Kovacheva included in their lists St. Godeleva (6 July—AASS, 29:431F), although the nature of the wounds does not fit the profile of the previous martyrs. Instead, there are newer testimonies regarding the emergence of white blood or milk at the beheadings of modern Christian martyrs. An eloquent case is the martyrdom of the Beata Viviana Mun Yeong-in, who, during the Shinyu persecution, was beheaded on 2 July, 1801, in Seoul: “the blood that came out of her during the tortures turned into flowers that flew away with the wind, while the one that gushed from her neck at the moment of her beheading was white like milk” (Flocchini 2014).

By overlapping the data obtained from the previous lists (Table 7), it can be seen that there are still differences between these occurrences, and that the phenomenon of the appearance of milk instead of blood takes various forms.

Table 7.

General overview of the phenomenon.

4. Motherhood, Innocence, Testimony

It is difficult to establish the significance of such a miracle to satisfactorily cover all these cases. Therefore, the approach of all occurrences was avoided, the research being limited either to the level of a single source, or to scrutinizing it rather tangentially and only limiting it to cases of female martyrs. We should also mention that the lives and deaths of these martyrs have been analyzed and interpreted almost exclusively by women researchers—an approach that can be included in gender and feminist studies.

What is certain is that the phenomenon is not limited to the martyrdom of the female martyrs, nor is it surprised by a single source. But, before interpreting the data, we should agree that the group of seven women of Sebastia is the same in both cases mentioned above. Likewise, the two Aemilianuses should be regarded as one and the same person, originally from Armenia. This is why these cases will be counted as one “occurrence”.

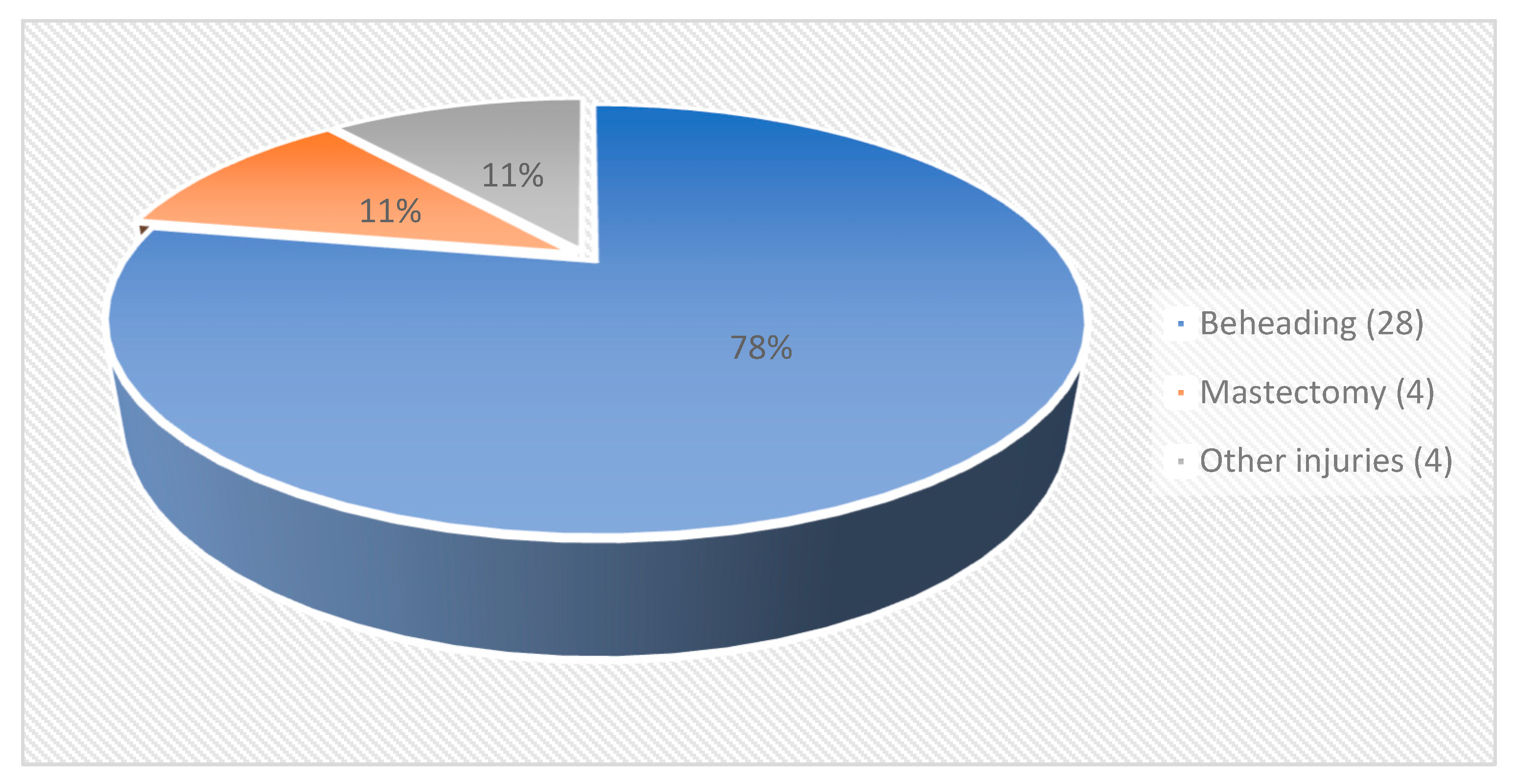

The type of lesions that cause the milk appearance is not the same either, or, if we resort to a classification of the wounds caused, we also see three different circumstances in which milk appeared instead of blood (Figure 1). Thus, we distinguish between beheadings and other wounds or mutilations.

Figure 1.

Classification by type of lesion.

A common denominator of all these cases is martyrdom. On the one hand, in the age of persecution, when both men and women followed the Savior’s command to leave their loved ones behind in their quest for spiritual perfection, motherhood itself was considered a social bond that was renounced in the name of faith, and that was thus incompatible with the idea of martyrdom (Salisbury 2004, p. 70).

On the other hand, in trying to find metaphors to describe the sacrifice of martyrs, the Christian authors focused on the idea of motherhood, believing that Christ’s confessors play the role of mothers caring for believers, as mothers began to be compared to martyrs for their devotion and self-sacrifice. Joyce Salisbury even claims that the very image of motherhood has changed, just as the blood of martyrs has changed into breast milk (Salisbury 2004, p. 70).

As already mentioned, the category of female martyrs has received special attention so far, emphasizing that, in their case, the physiological manifestation of motherhood (pregnancy) was not required for the appearance of milk when the breasts were amputated, as in the case of Saints Pistis, Cyprilla, Lucia and Christina. Their breasts were cut off—basically a brutal double mastectomy—but, instead of bleeding, “milk” gushed out. For Nicola Denzey, this reversal betrays a rather deep ambivalent sexism that is uncomfortable with the overlapping notion of martyrdom and motherhood (Denzey 2007, p. 170).

But the phenomenon of “lactation” is rather the undeniable proof of their quality as spiritual mothers, and the martyrs have the consciousness of being the “mothers” of the next generations of Christians, converted to the sight of the miracle. Thus, they are considered holy vessels of spiritual food, and even imitators of Christ and the Virgin Mary (Denzey 2007, p. 245). According to Western mysticism in the Middle Ages, the wound on the Savior’s side is perceived as the breast from which the Church is nourished (Bynum 1982, pp. 125–35). Julian of Norwich (1342–1416) points out, in Revelations of Divine Love (ch. 60), this parallel between the milk flowing from the mother’s breast and the blood flowing from the side of Christ, which he describes as a nursing mother. The image had a great impact on Catholic spirituality, and, after a few decades, graphic representations of this breastfeeding with the blood of Christ appeared, such as the scene “The Savior” (1460–1478) by Quirizio da Murano. Following a two-century-old graphic tradition, the Italian Renaissance artist places the wound from the side of Christ high enough to create the image of a breast, drawing the parallel between the saving blood and the breast milk of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

If we take into account this blood–milk relationship, which includes the “maternal nature of Christ’s wound”, the female martyrs come to be perceived—especially in light of the hagiographic depiction of the Golden Legend—as the ones who spring the redeeming power that has its origin in the wounds of Christ (Harney 2008, p. 243).

Becoming imitatrices Christi in this way as well, the bodies of the female martyrs represent the food of the faithful, and the appearance of milk underlines this idea even more deeply, consolidating, at the same time, their status as spiritual mothers of the community. Their blood is redemptive and nourishing milk, a symbol of their spiritual quality.

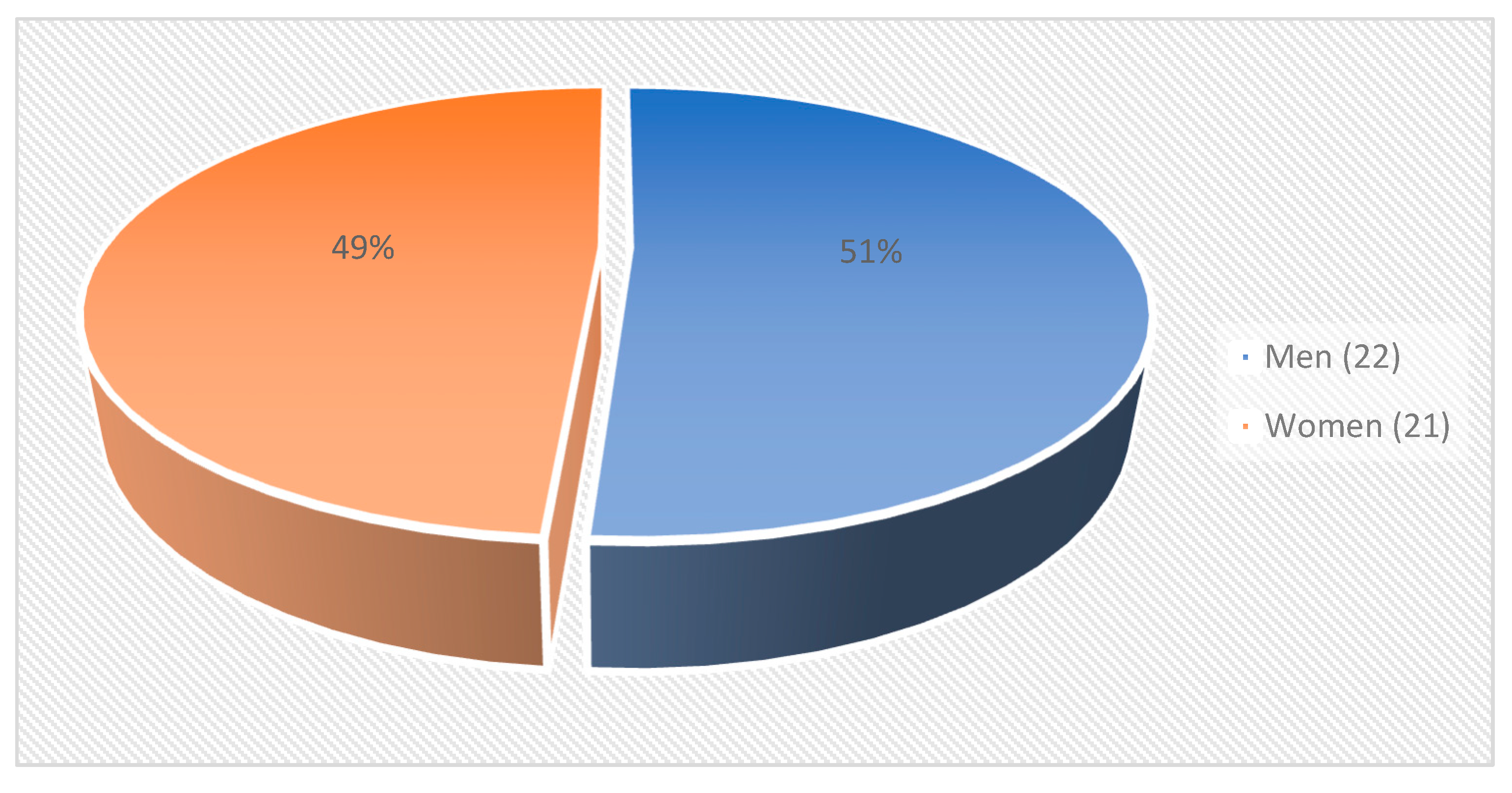

But it must be pointed out that the number of female martyrs upon whose deaths this phenomenon occurs is about half of the total number of “lactating” martyrs identified so far (Figure 2). Thus, this trope is not related only or mainly to female martyrs, but it is also a topos that is used for both genders in a nondiscriminatory manner.

Figure 2.

Classification by gender.

Therefore, an examination of the significance of this phenomenon in the case of male martyrs is also required. The male martyrs themselves become, through their sacrifice, mothers who contribute to the rebirth of the Church’s new members. They are the exponents of the Church’s motherhood that is manifested regardless of gender. The idea of motherhood expresses the need for Christians to remain united in the love of Christ, and the martyrs come to embody this double image of (a) the sacrificial love manifested by Christ, and (b) the motherhood of the Church. That is why “martyrs served as mothers” (Salisbury 2004, p. 74), and, with a real “maternal affection” (μητρικὰ σπλάγχνα), they interceded for other Christians, “shedding rich tears for them before the Father.” (Eusebius of Caesarea, Historia ecclesiastica, V.2, PG 20:436.)

Intercession thus becomes the attribute of motherhood, and martyrs each incarnate the maternity of the Church through their sacrifice and intercession before God the Father. And if the blood of the martyrs is the seed of Christians, according to Tertullian’s vision, then they nurture and increase in faith the Christian communities, like loving mothers (Salisbury 2004, p. 75). This role becomes even more evident through the appearance of milk at the beheadings of martyrs.

Such a perspective derives from the belief, manifested in the ancient eastern Mediterranean cultures, that there is a fine distinction between motherhood and womanhood, and Christianity embraced it: “the motherhood is understood as the topos of agapic love, of total devotion to the child, and the womanhood in seen as the archetype of devotion—in love, in family preservation, in the professional activity or in that of personal holiness […] Maternal love is a reflection of the sacredness in the world. The link between motherhood and sacredness is a given, beyond any contextualization” (Pătru 2021, p. 95).

Therefore, the concept of motherhood, based on the notions of devotion, intercession and nursing by providing spiritual nourishment, was not limited in early Christianity just to female martyrs, but was perceived as an attribute suitable for all martyrs, regardless of gender.

Unfortunately, under the pressure of the new ideological wave of gender studies, milk has come to be considered as the environment through which a body can change its gender (transgendered)—from female to male, from male to female. Just as cutting off the breasts of virgins would mean changing their bodies into masculine ones, so the gushing out of milk from the bodies of martyrs would turn their masculine bodies into feminine ones (Denzey 2020, pp. 287, 294). The temptation to anachronistically and gratuitously project contemporary concepts is a common practice today, theorizing the “trans* saints’ hagiography” (Godsall 2020, pp. 233–70). But the body’s significance should be understood in terms of the specific characteristics and limits of the original cultural environment in which these texts appeared.

Therefore, the phenomenon of “lactation” must be read in the hermeneutic key that is indicated by sources as close as possible to these vitae and passiones.

What the authors of these studies seem to ignore is that another common denominator of these occurrences is the virginity of both female and male martyrs. The appearance of milk is considered the visible sign of the purity of the soul and body that these Christians have cultivated, devoting their whole lives to God. It is also considered the final proof of the martyrs’ innocence in front of their accusers (Boldetti 1720, p. 137).

More than that, milk is, at the same time, a symbol of spiritual nourishment, and a sign of the imperfection of those who need such a miracle as a testimony or an additional impetus to strengthen their faith. Christians still needed “pure spiritual milk, so that by it may grow up in salvation,” according to the Apostle Peter (NIV 1Peter 2: 2). Therefore, one can guess that there was a pedagogical dimension to this phenomenon, meant to raise the believers to a higher natural spiritual state, as the Apostle Paul pointed out: “I gave you milk, not solid food, for you were not yet ready for it. Indeed, you are still not ready” (NIV 1Cor 3: 1–3), for “solid food is for the mature, who by constant use have trained themselves to distinguish good from evil” (NIV Heb 5:14).

In his exegesis to these verses, Clement of Alexandria points out even better that the milk can not only be interpreted as testimony and preaching (κατήχησις) (Paedagogus I.VI. 38–50), but it can also be considered, simultaneously, the first food of the soul and the very body of Christ (τὸ σῶμα τοῦ Χριστοῦ—§42). Following Empedocles’ and Aristotle’s medical observations, and the Hippocratic gynecological theories regarding the origin of breast milk as concocted or cooked menstrual blood (Tuten 2014, p. 165–67), Clement considered that “the blood is the source of milk” (§45), and “milk retains its underlying substance of blood” (§39), and therefore he “had been equating milk with Jesus’ blood as true drink in order to show that milk as a perfect drink gives us the γνῶσις of the Truth” (Van Eijk 1971, p. 107).

The martyrs’ sufferings often caused the torturers to fear and the witnesses to convert, and thus the miraculous appearance of milk further mediated the γνῶσις shared by those subjected to violence and violent deaths.

Milk itself becomes a form of confession or preaching the faith to an audience still unprepared to comprehend all the meanings of the Gospel (1 Cor 3: 2). The symbolic nature of milk is even better emphasized on other occasions, the saints being considered “the breasts that spring the milk of salvation,” (Men. 30 January), and the “breasts of the Church that spring the milk of good faith and feed the believers,” (Men. 25 October), watering them “with God-inspired intelligible milk” (Men. 30 January). The holy martyrs come to be represented as icons of the Church because, apparently contrary to any logic, they bear fruit and nourish the community precisely by coming out of this life (Isaiah 54: 1).

Beyond the symbolic nature of milk, and taking into account the recent medical research, we must consider the possibility that this phenomenon could be the manifestation of extreme cases of hypertriglyceridemia—induced by certain types of health problems or by the ill treatment suffered by martyrs in prison. Hypertriglyceridemia can be divided into primary and secondary types: the first is determined by genetic factors, and the second is caused by metabolic conditions and is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension and hyperuricemia (Yuan et al. 2007), but it can also be triggered and worsened by traumatic and stressful life events (Anni et al. 2021) and starvation (Urayama and Banks 2008, p. 3595). The torture (physical and mental) is an aggravating factor, which is often described in detail, becoming the core of the martyr’s passio, but the starvation of Christians in prisons was also a common practice (Tilley 1996, p. XXXV) and, although it is not explicitly mentioned in the passiones, it cannot be omitted: “For the prison must become familiar to us, hunger and thirst practiced, and tolerance both for the absence of food and for anxiety about it grasped.” (Tertullian, De ieiunio adversus Psychicos, 12.2, CCSL 2:1270.) Thus, the ill treatment provided aggravating conditions for the development of such a metabolic abnormality.

This medical aspect could shed new light on the biographical accounts of Apostle Paul’s health issues, for example. By placing separate passages side by side, some exegetes came to the conclusion, very popular in the 19th century, that his illness “was acute and disfiguring ophthalmia, originating in the blinding glare of the light which flashed round him at Damascus, and accompanied, as that most humiliating disease usually is, by occasional cerebral excitement” (Exell 1985, p. 291). This condition “would naturally disincline him to the physical labour of writing. When he did write, his letters seem to have been large and straggling (Gal 6:11: See what large letters I use as I write)” (Exell 1985, p. 551). Later, epilepsy was offered as the most likely hypothesis for Paul’s chronic disease, and Pierre Vercelletto suggests the possibility of facial motor and sensitive disturbances coming after ecstatic seizures (Vercelletto 1994). While correlated with the possible hypertriglyceridemia mentioned by the hagiographic sources, the ophthalmologic problem is, rather, a form of retinopathy, which is consistent with diabetes symptoms.

5. Conclusions

Observing the magnitude of this phenomenon, we can consider that the martyrs’ “lactation” is much more than the result of a folklore heritage or tradition, nor is it limited to a certain cultural area (Egyptian, Mediterranean or even European), such as Barry seemed to believe. His thesis, “in the traditions of the saints, lived on the mythology and folk-lore of the old gods”, appears to establish a plausible relation between the “lactation” of Egyptian goddesses (Ivanova 2009, pp. 12–22) and the miraculous milk spilled from the beheaded bodies of martyrs, considering “the martyr-cult, a tribute of the church to latent polytheism” (Barry 1914, p. 561). But this premise fails to apply to the eastern and northern Mediterranean areas, and there is no common ground to link the phenomenon in a similar way to other pre-Christian traditions. On the other hand, the antiquity of the hagiographic testimonies places the development of this topos before any attempts of denominational definition, and independent of the systematization of the archeological testimonies, realized in the 16th–17th centuries, as Ghilardi suggests. Therefore, the criteria of the antiquity and general spread of this topos in the Christian tradition represent sufficient arguments that the phenomenon’s occurrences are neither perpetuations of some ancient Egyptian traditions, nor recent invetiones.

In addition to the symbolic value of the milk’s appearance, which has been interpreted arbitrarily in recent decades, it must be borne in mind that the phenomenon is not just a literary cliché, and it could correspond to a real event, a symptomatology that can be documented with the support of recent medical discoveries. It is true that we cannot prove with certainty whether true milk appeared at the martyrs’ deaths, or whether these were just extreme cases of hypertriglyceridemia—induced by certain types of health problems and extreme stress.

And even if a medical term were applied to these situations, it does not then mean a contestation of the miracle itself, and a possible explanation does not underestimate the value of confession, nor does it diminish the virtue of martyrdom, just as the definition of “hematidrosis” does not at all change the conviction that the soul-stirring of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane was as real as could be: “and his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground”(NIV Lk 22:44). Likewise, Christ’s diagnosis of traumatic serous pericarditis and hemopericardium (Malantrucco 2013), as evidenced by the fact that “one of the soldiers pierced Jesus’ side with a spear, bringing a sudden flow of blood and water” (Jn 19:34), only further confirms the reality of Christ’s death on the cross, dispelling any suspicion of fainting or simulated death.

From a theological point of view, “γάλα ἀντὶ αἵματος” is more than a hagiographic trope based on “pious” fabrications. The appearance of milk is an iconic phenomenon that expresses, in a symbolic manner, the martyrdom–motherhood relationship. This miracle is a visible sign of the maternal vocation proven by those who devoted their lives to Christ and suffered death for their faith. The martyrs, regardless of gender, incarnate the maternity of the Church through their sacrifice and intercession before God, and so the miraculous milk becomes the attribute of this sacred motherhood.

Funding

This research was financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu and Hasso Plattner Foundation research grants LBUS-IRG-2021-07.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | The kanon of St Eupsychius (9 April) states that: “Thy divine head was cut off with a blow from a sword, O valiant martyr, and instead of blood thou didst miraculously pour forth milk and water, and didst draw the ignorant to understanding, receiving ineffable glory and granting great mercy to all by thy divine mediations.” |

References

- Anni, Naharin Sultana, Sun Jae Jung, Jee-Seon Shim, Yong Woo Jeon, Ga Bin Lee, and Hyeon Chang Kim. 2021. Stressful life events and serum triglyceride levels: The Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center cohort in Korea. Epidemiol Health 43: e2021042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagatta, Giovanni Bonifacio. 1695. Admiranda Orbis Christiani Quae Ad Christi Fidem Firmandam, 2nd ed. Venice. vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Phillips. 1914. Martyr’s Milk. (Miraculum: Lac pro sanguine). The Open Court 9: 560–73. [Google Scholar]

- Boldetti, Marc’Antonio. 1720. Osservazioni Sopra i Cimiterj de’ Santi Martiri ed Antichi Cristiani di Roma, Aggiuntavi la Serie di Tutti Quelli che Fino al Presente si Sono Scoperti, e di Altri Simili, che in Varie Parti del Mondo si Trovano, con Riflessioni Pratiche Sopra il Culto delle Sagre Reliquie. Roma: Salvioni. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1982. Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delehaye, Hippolyte. 1902. Synaxarium Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae e Codice Sirmondiano. Brussels: Socios Bollandianos. [Google Scholar]

- Denzey, Nicola Frances. 2007. The Bone Gatherers: The Lost Worlds of Early Christian Women. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denzey, Lewis Nicola. 2020. Food for the body, the body as food: Roman martyrs and the paradox of consumption. In Lived Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Approaching Religious Transformations from Archaeology, History and Classics. Edited by Valentino Gasparini, Maik Patzelt, Rubina Raja, Anna-Katharina Rieger, Jörg Rüpke and Emiliano Urciuoli. Berlin and Boston: DeGruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Exell, Spence-Jones. 1985. The Pulpit Commentary (23 Volume Set). Edited by Joseph S. Exell and Henry Donald Maurice Spence-Jones. Virginia: Hendrickson Publisher, vol. 19. First published 1880–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flocchini, Emilia. 2014. Beata Viviana Mun Yeong-in Vergine e martire. Enciclopedia dei Santi. Available online: http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/96457 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Garitte, Gérard. 1955. La Passion de S. Irénarque de Sébastée et la Passion de S. Blaise. Analecta Bollandiana 73: 18–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilardi, Massimiliano. 2012. Lac pro sanguine fluxit passiones antiche, inventiones moderne: Intersezioni tra agiografia e archeologia. In Hagiologica. Studi per Réginald Grégoire. Edited by Alessandra Bartoloemei Romagnoli, Ugo Paoli and Pierantonio Piatti. Fabriano: Monastero San Silvestro Abate, pp. 1209–22. [Google Scholar]

- Godsall, Jade C. 2020. ‘The Word Became Flesh and Dwelt among Us’. The Interrelation between the Gendered Body and Holiness in Late Medieval Hagiography. Ph.D. thesis, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Harney, Eileen Marie. 2008. The Sexualized and Gendered Tortures of Virgin Martyrs in Medieval English Literature. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, Maria. 2009. Milk in Ancient Egyptian Religion. Essay: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, Philipp, Paul J. Bröckelmann, Hallek Michael, and Kochanek Matthias. 2019. Bloodletting to Treat Severe Hypertriglyceridemia. Annals of Internal Medicine 171: 142–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacheva, Eva. 2018. Paнноxpиcтиянcки мъчeници, от които, cпоpeд житиятa, изтичa “мляко вмecто кpъв” [Early Christian Martyrs According to the Passional from Which “Milk Is Flowing Instead of Blood”]. In Cъвpeмeннaтa cвятоcт: иcтоpия, обpaзи, cимволи, пpaктики. Sofia: Пловдивcки yнивepcитeт Пaиcий Xилeндapcки, pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lackner, Wolfgang. 1967. Zu Quellen und Datierung der Maximosvita (BHG 1234). Analecta Bollandiana 85: 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malantrucco, Luigi. 2013. Cum a Murit de Fapt Iisus? Investigațiile Unui Medic [How Did Jesus Died Actually. The Investigations of a Medic], 2nd ed. Sibiu: Deisis. [Google Scholar]

- Pătru, Alina. 2021. Valenţe creatoare ale femininului ancorate în sfera sacrului. Contextualizări religios-culturale europene şi orientale [Creative Potentialities of the Feminine Anchored in the Realm of the Sacred. European and Oriental Religious-Cultural Contextualizations]. Transilvania 6: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pixley, Mary L. 2012. Preserved for Eternity on Obsidian. A Baroque Painting Showing the Miracle of Milk at St. Catherine of Alexandria’s Martyrdom. MVSE 46: 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rogozhina, Anna. 2019. ‘And from His Side Came Blood and Milk’: The Martyrdom of St Philotheus of Antioch in Coptic Egypt and Beyond. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, Joyce E. 2004. The Blood of Martyrs. Unintended Consequences of Ancient Violence. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, Maureen A. 1996. Literary and legal notes. In Donatist Martyr Stories. The Church in Conflict in Roman North Africa. Translated by Maureen A. Tilley. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. xix–xxxvi. [Google Scholar]

- Tuten, Belle Stoddard. 2014. Lactation and Breast Diseases in Antiquity: Medical Authorities on Breast Health and Treatment. Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae 19: 159–86. [Google Scholar]

- Urayama, Akihiko, and William A. Banks. 2008. Starvation and Triglycerides Reverse the Obesity-Induced Impairment of Insulin Transport at the Blood-Brain Barrier. Endocrinology 149: 3592–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, Antonius Henricus Christiaan. 1971. The Gospel of Philip and Clement of Alexandria: Gnostic and Ecclesiastical Theology on the Resurrection and the Eucharist. Vigiliae Christianae 25: 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelletto, Pierre. 1994. La maladie de Saint Paul. Extase et crises extatiques. Revue Neurologique 150: 835–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, George, Al-Shali Khalid Z., and Hegele Robert A. 2007. Hypertriglyceridemia: Its etiology, effects and treatment. Canadian Medical Association Journal 176: 1113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).