Abstract

The article provides a sociological and pastoral analysis of a representative empirical study conducted by means of an interview questionnaire among 1003 secondary school students in 2020 and 2021. The analysis was expanded to include data from parallel and similarly designed sociological studies carried out among teachers of religious education in order to obtain a broader view of the research problems and a better understanding of young adults by becoming familiar with the perceptions and opinions of teachers on the analysed issues. The article reflects on and discusses the following issues: personal relationships between young adults and the Church along with their expectations towards the latter, factors considered to persuade young adults to develop their faith and be part of the Church, as well as Church activities and offers regarded by the surveyed subjects as particularly needed. These issues, presented from an interdisciplinary perspective, provide a deeper insight into people’s relations with the Church and allow for diagnosis of their needs and expectations. They also enable identification of the elements and aspects of the functioning of the religious institution, which, in a pluralistic society and the course of the ever-advancing secularisation, requires a profound diagnosis, a thorough analysis and questions about the adequacy of forms and methods of evangelisation, as well as ways of reaching the target audience and the fulfilment of the fundamental religious mission.

1. Introduction

Contemporary transformations in the religiousness of individuals and societies are part of the complex processes of social and cultural changes associated with economic and social modernisation. Their hallmarks include differentiation and institutional specialisation, worldview competition, individualisation, religious pluralism and inclusiveness when interpreting the role of individual religions in social life. These processes affect the functioning of religions and churches, causing people to distance themselves from traditional religious systems and institutional forms of religiousness. They imply the privatisation of religion and the formation of religiousness of choice, constructed by autonomous decisions of individuals (). Although religion and churches are losing their significance and binding power in the lives of many communities, their importance in the social space does not decrease while religious institutions remain key participants in public debates ().

Sociological images of religiousness in individual countries bring to light its complexity, diversity and manifestations of both secularisation and de-secularisation accompanied by clear signs of a return to the sacred. The coexistence of these multidirectional processes is noted by researchers diagnosing changes in religiousness within the Catholic Church. They indicate a decrease in the level of religious practice and self-declaration of faith, an increase in the percentage of people who do not practise and declare agnosticism or atheism, as well as a higher frequency of critical attitudes towards the Church and its representatives. At the same time, they note that many countries see a stabilisation in the percentage of individuals declaring deep faith and involvement in religious life or even manifestations of religious revival and revitalisation of traditional religious systems (). Similar conclusions were already reached in the 1980s and 1990s by Lesie J. Francis and his collaborating authors, who studied attitudes towards different Churches in various countries (See ; ).

Against this background, Poland remains a country with relatively high rates of religiousness compared to other European countries and where “the number of people declaring a high level of religiousness is higher than those who declare themselves as non-religious” (). Reasons for this state of affairs include historical conditions, national and cultural homogeneity and, as noted by many analysts, a significant influence of the pontificate of Pope John Paul II.

In Catholicism, the state of belonging to the Church and active participation in its life is fundamental to living out one’s faith and striving to attain the key goal of salvation. From a theological perspective, the Church is a community of people who believe in Christ and were baptised in that Church. In Catholic theology, they form the People of God who pursue salvation under the leadership of the Pope. However, the Church is understood not only as the community founded by Christ, but also as His Mystical Body of which He is the Head. The most crucial attributes of the Catholic Church include unity, holiness, universality and apostolicity (; ).

The sociological understanding of the Catholic Church assumes that it is “a social organisation uniting those who share common religious beliefs, undertake common actions, recognise similar religious values and norms, and accept certain hierarchical and organisational structures” (). Sociology analyses the historical and social aspects of the Church’s functioning, changes in its position and its role in society.

The theological context and sociological analyses of the Church highlight the fact that religiousness is integrally linked to ecclesiasticism. This is evident from the empirical diagnoses of changes in religiousness, which identify the intensification of “dechurching” processes (the weakening of the bond with the Church) without departure from the Transcendent (). Due to historical conditions, this link between religiousness and ecclesiasticism is particularly visible in Poland (; ). For many years, it was reflected by the high level of trust in the Church as an institution, recorded in surveys and public opinion polls, as well as by the perception of its role as an actor in the public space or a community within local communities (). According to a study conducted a few years ago in 13 countries of Central and Eastern Europe, Poland was the place where the level of trust in the Church was the highest (). Janusz Mariański believes that in Poland, trust in the Church as a social institution has a fluctuating character and, at the same time, is conditioned by a generally low level of social trust among its inhabitants (). Many sociological analyses show that Poles’ trust in the Church has been systematically weakening. In 2020, it was declared by 42% of respondents; in 2010—by 78%, in 2012—69% and in 2016—70%, with 47% of the surveyed individuals indicating their lack of trust in the same year ().

Similar to other European countries, Polish society experiences changes in religiousness, which take place at different speeds; there is even a process referred to as the emigration from the Church (), which is one symptom of the previously mentioned secularisation and individualisation of religiousness. Mariański writes about the increasingly widespread phenomenon of extra-Church religiousness and, in extreme cases, anti-church attitudes (). Particularly dynamic changes in the area of religiousness have been taking place since the death of John Paul II in 2005 (). Data collected by the Pew Research Centre show that the secularisation of young Poles occurs at the most rapid pace of all countries surveyed (, ). In Polish conditions, secularisation often does not indicate a complete rejection of religious needs, but rather the privatisation of the search for ways to satisfy them, including, among other things, the contestation of the Church (). Catholics, especially young ones, more and more frequently claim that being religious does not require belonging to any religious organisation or community (). This approach is reinforced by the postmodern philosophy involving anti-institutional assumptions (). At the same time, scholars identify the process of religious polarisation in Poland as analogous to the tendencies across Europe, meaning there is a stabilisation or even a slight increase in the percentage of people declaring to be deeply religious and practise more frequently, accompanied by a significant increase in the number of non-religious individuals ().

According to the report published by Statistics Poland in late 2021, currently, 84.5% of the Polish society declares affiliation to the Catholic Church (). The aforementioned findings are dynamic and consistent with the above processes reported by the researchers. Pursuant to the results of the 9th edition of the 2018 European Social Survey, the percentage of people declaring religiousness in Poland fell from 93.3% in 2002 to 87.2% in 2018. Compared to other countries, Poland distinguishes itself in terms of the percentage of people describing themselves as “very religious”, but this area also features a downward trend (a decrease from 13.2% in 2002 to 11% in 2018). It is worth noting that different tendencies, e.g., regarding the revival of individuals’ religiousness, have been identified in countries such as France and Spain, where the recorded level of religiousness remains stable or decreases, while the number of followers of Catholicism who declare intensive faith is constant (). The percentage of people who pray daily (31%) and participate in religious practices at least once a week (46%) is also high (; ).

Since 2020, the process of abandoning religious practices in Poland has accelerated, and, as noted by Mirosława Grabowska, every month, the percentage of individuals claiming not to practise exceeds 20% (). The secularisation tendencies present in Polish society are further indicated by the 2019 data of the Institute for Catholic Church Statistics, according to which the rate of dominicantes was 36.9%, with the rate of comunicantes at 16.7% ().

The processes of emigration from the Church are particularly evident among young adults, who are becoming increasingly secularised across Europe. Analyses of the individual parameters of their religiousness indicate a decrease in the frequency of religious practices, a weakening of bonds with the Church and parishes, increasing autonomy of the moral sphere, a critical attitude towards the Church and a weakening trust in its representatives. Compared to other European countries, the dynamics of changes in the religiousness of Polish young adults is, as previously mentioned, particularly prominent and reaches very high. The level of religiousness declared among 15–24 year olds fell from 91.6% in 2002 to 82.1% in 2018 (). In 2021, in the 18–24 age category, the percentage of believers amounted to 71% (a 22% decrease compared to 1992), while the number of non-believers increased to 28.6%. In this group, the proportion of regular practitioners has also been declining at the fastest rate—from 69% in 1992 to 23% in 2021—while the proportion of non-practitioners has risen from 7.9% to 36%. Grabowska believes that one of the possible explanations is that for the youngest respondents, “who mostly live with their families and are still studying, non-practising is an element of emancipation from the influence of their family and immediate environment” (). A number of other factors should also be taken into account, including passage into adulthood—the process of shaping one’s own identity, attitudes and opinions, searching, contesting and verifying values passed on by adults—as well as the impact of intensive cultural changes, such as those within the communication—diffusion of cultural patterns, the influence of modern technologies, mediatisation, etc.—all of them have affected the young generation ().

The declining importance of religious life among young Poles and their tendency to ascribe it a considerably less significant role than adults is evidenced by the results of surveys, according to which young people “less and less frequently link their behaviour to any single, strictly defined system of values” (). In response to the question about the dominant types of activities in everyday life, religion was indicated by 10% of adults and 3% of young people aged 18–24. At the same time, in this group of young individuals, the share of people describing themselves as non-believers (5% in 2008 and 17% in 2018) and religiously indifferent (13% and 21%, respectively) has substantially increased, while the number of those declaring faith has decreased (from 73% to 55%). This attitude has significantly differentiated young people from the adult generation since 2018. Moreover, the rate of believers practising every Sunday is decreasing—in 2018, it was 28% ().

With regard to the topic discussed in this article, it is once again worth noting that the abandonment of religious practices is not equivalent to the departure from faith among young adults in Poland. As argued by the authors of a nationwide CBOS survey, “young adults first stop attending Church, and only then begin to identify themselves as non-believers. Still, those declaring to be non-believers constitute half the percentage of those who do not practise” (). At the opposite pole are young deep believers (about 8%), whose declarations of faith and religious practices go hand in hand.

Transformations of religiousness are also visible in its consequential dimension, i.e., in the area of values and norms shaping everyday moral attitudes. A significant part of Polish society rejects the comprehensive system of beliefs and moral principles proclaimed by the Church, constructing “its own God, its own heaven, its own salvation, its own little creed” (). The individualisation prevailing in modern societies and the autonomy of individuals as a principle of action results in the subjectivisation of faith and a change in previous forms of religiousness, often involving the “dechurching of the individual”, as well as liberation from the influence of family and tradition in favour of independently constructed, autonomous systems of belief (; ). The transformations of axiological and cultural sensitivity revolve particularly around the youngest Poles, whose beliefs and attitudes have become increasingly deviated from the institutional framework of religious culture (). The vast majority of young Poles are in favour of selective religiousness and do not accept the Church’s teachings on issues related to sexuality, such as contraception or homosexuality (), thereby consciously selecting which values and norms to accept or reject (). As the authority of the Church is weakening, a decreasing number of young people are becoming involved in its activities ().

The aforementioned processes are accompanied by critical opinions on the Church among young people. Many of them perceive it as too conservative, distant from life problems (), unreliable, intolerant and excessively focused on politics and material matters (). The main problem is that the Church does not respond to the existential problems of young people (). The indicated reasons undermining the authority of the Church include phenomena such as moral scandals, paedophilia among some priests, as well as the active involvement of the Polish Church in political activities (; ; ).

In terms of the described fluid boundaries of the religious field in the lives of young people, it is extremely important, from the perspective of both pastoral theology and sociology, to update, expand and acquire reliable knowledge about young people’s attitudes towards the Catholic Church to which they declare belonging.

2. Method

In 2020 and 2021, representative sociological research was conducted among secondary school graduation class students and religious education teachers in the Archdiocese of Lublin. This archdiocese is located in the southeastern region of Poland, covering the area between the middle part of the Vistula and Bug rivers. It is an administrative area of the Lublin province, comprising 272 parishes on 9108 km2. It is inhabited by 1,074,242 people, including 1,023,680 Catholics.

The sociological research related to, among other things, the contemporary needs, values and problems of young people, the place of faith and religiousness in their everyday experience, as well as their participation in religious education lessons and extracurricular activities. One segment of the research project studied the respondents’ relationship with the Catholic Church and, more specifically, their perceptions of their own presence in it. From a sociological point of view, these issues concern the communal dimension of religiosity. Nevertheless, the research project did not aim to analyse religiousness, but rather to search for information forming the outline of a portrait depicting what young people think about themselves and their peers, their own activity, faith, religiousness, the meaning of religious education and being in the Church (See ). The original research idea was to formulate analogous questions in sociological studies conducted simultaneously among teachers in order to broaden the cognitive perspective, describe the issues of interest in a more accurate manner and establish how individual issues are identified by adults teaching young people. The goal of the project was to understand, as accurately as possible, young adults in their perception of the issues selected for analysis to gain insight into their situation and, at the same time, establish how their teachers perceive particular issues.

After taking into account the assumptions and goals, two survey questionnaires were developed targeting secondary school graduation class students and teachers. The research tools included original questions developed for the purposes of this project, as well as questions used in previous sociological or pastoral studies, modified or updated, which were relevant to the formulated research questions. Four indicator questions concerning young adults’ relationships with the Church were created within the segment; the first concerned the definition of one’s own relation with this institution, and the second one concerned young adults’ expectations towards it. The third question gathered young adults’ opinions on factors that persuade their peers to practise faith and be part of the Church, while the fourth involved offers provided by the Church that, according to the respondents, are particularly needed by young people at present. Teachers were asked to answer analogous questions from the perspective of their teaching practice and observations of young people.

The empirical research was conducted by the Centre for Sociological and Economic Analysis in Lublin. An auditorium questionnaire was used as a research tool with stratified random sampling. The study was participated in by students aged 18 and older. Auditorium questionnaires were filled in and collected during lessons in which attendance is required from all students. Religious education and ethics lessons were excluded, considering that participation in these classes is optional and thus partial. The empirical material collected from 1003 respondents was used for statistical analyses. Two independent variables were applied to describe the results of the empirical study: “gender”—questionnaires were completed by 561 females, i.e., 56.4% of all participants, and by 433 males, i.e., 43.3%, as well as “place of residence”—538 respondents lived in rural areas (54.0%) while 459 lived in urban areas (46.0%). In terms of statistical analyses, the chi-square test was used to determine the relationship between the analysed variables based on the frequency distribution of the responses. Cramer’s V was applied to demonstrate the strength of this relation. The empirical analyses in question describe only the independent variables that, when correlated with dependent variables, showed a significant statistical dependence confirmed by the chi-square test, i.e., p ≤ 0.05. The strength of the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable, as determined by Cramer’s V, can be read individually within the following ranges: 0–0.2—very weak relationship, 0.2–0.4—weak relationship, 0.4–0.6—moderate relationship, 0.6–0.8—strong relationship, 0.8–1—very strong relationship.

A sociological survey among religious education teachers was conducted in 2021, also by the Centre for Sociological and Economic Analysis. The aforementioned institution developed a survey script using the Lime Survey tool. After the survey was downloaded to the server of the analysing centre, a relevant link was sent to all religious education teachers in the Lublin archdiocese via e-mail. A total of 348 teachers completed the online survey, including 248 women (71.3%) and 100 men (28.7%). Among them were 253 laypeople, 51 priests, 42 monks and nuns and 2 individuals from institutes of consecrated life.

3. Analysis of Empirical Data and Discussion

The results of the empirical research on the following questions are presented below:

3.1. Relationship with the Catholic Church

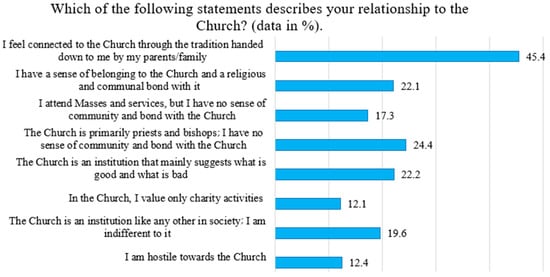

The first question posed to the young surveyed adults was: “Which of the following statements describes your relationship with the Church?”. Its purpose was to gain an understanding of how young people define their personal relationship with the Church. Each respondent could choose any number of answers from among the seven suggested. The answers gave them the possibility to declare a bond with the Church (or lack thereof), name the type of belonging in religious and community terms, provide key factors in their relationship with the Church (family tradition, religious practices) and indicate a link between the Church and clergymen or between the Church and an institution teaching only about moral issues or associated mainly with charity activities. The respondents could also declare indifference or hostility towards the Church. The detailed survey data are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Relationship of young adults with the Church.

The three answers most often indicated by young adults included the relationship with the Church based on the tradition handed down by parents/family (45.4%), followed by the belief that “the Church consists mainly of priests and bishops, I have no sense of community or bond with it” (24.4%) and: “the Church is an institution that mainly suggests what is good and what is bad” (22.2%). Taking into account the possibility of multiple-choice answers to the question at hand, it can be seen that half of the respondents declared to have a relationship with the Church that is anchored in the tradition handed down by their parents or family; one in four respondents saw the Church as an institution composed of clergy and had no sense of bond with it; one in five had a sense of belonging to the Church and felt a communal and religious bond with it; and one in five perceived the Church as an institution that first and foremost teaches what is good and what is bad or as one of many institutions of social life towards which they are indifferent. Almost one in six respondents declared that they attend Mass and services while not experiencing a sense of community and bond with the Church. It is worth noting that one in four respondents were indifferent to the Church or declared a sense of belonging along with a religious and communal bond. By contrast, one in eight individuals being studied declared a hostile attitude towards the Church.

The independent variable “gender” revealed a significant statistical differentiation with regard to only one statement included in the question: males declared that the only thing they value in the Church is its charity activity more often than females (14.8% vs. 10.0%; p = 0.013, Cramer’s V = 0.073). Significant statistical differentiation was found more often in the case of the independent variable “place of residence”; rural residents more frequently felt connected to the Church through the tradition handed down by their parents/family (51.2% vs. 38.6%; p = 0.0001, Cramer’s V = 0.127) and indicated a sense of belonging to the Church along with the feeling of communal and religious bond with it than urban residents (28.4% vs. 15.4%; p = 0.0001, Cramer’s V = 0.160). In the remaining three statements revealing a significant statistical relationship, urban residents were more likely to state that “the Church consists mainly of priests and bishops, I have no sense of community or bond with it” (29.2% vs. 20.4%; p = 0.023, V Cramer’s V = 0.023), regard the Church as an institution like any other in society, declaring their indifference towards it (23.1% vs. 16.5%; p = 0.009, Cramer’s V = 0.082) and indicate hostility towards the Church than rural residents (16.5% vs. 8.9%; p = 0.0001, Cramer’s V = 0.0115). The above data show that aversion and hostility towards the Catholic Church are more common among urban residents than rural ones.

As previously mentioned, an analogous question was asked in a sociological study conducted on a group of religious education teachers. They were asked to determine, on a seven-point scale where “1” means “very often” and “7” means “never”, the relationship of secondary school students with the Church. The empirical results indicate that, according to the teachers, young adults most often feel connected to the Church through the tradition handed down by their parents/family (scale from 1 to 3: 71.0%). The second most frequent answer provided by the teachers concerned the perception of the Church as an institution that first and foremost suggests what is good and what is bad by young adults (62.0%), and the third answer reflected young adults’ conviction that the Church consists mainly of priests and bishops and their lack of a sense of community and bond with it (61.9%). It is worth noting that the hostility of young adults towards the Church was identified, although to varying degrees, by every third surveyed teacher (31.6%). Detailed data on the analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Opinions of religious education teachers on the relationship of students to the Church.

Declarations of a considerable part of young adults suggest the dominance of the family tradition in their bonds with the Church. The teachers’ observations are analogous: they are convinced that for a large number of young people, their bond with the Church stems from the tradition handed down by parents and family. From the perspective of sociological and pastoral analyses of Polish Catholicism, it is crucial to note that the answers of the students and observations of the teachers ranked second and third in terms of frequency (the image of the Church as consisting only of priests and bishops and the lack of bond with it, as well as the image of the Church that mainly teaches what is good and what is bad). On the one hand, it can be concluded that these statements reflect stereotypical beliefs, which have been reproduced or popularised in Polish society and confirmed by numerous sociological studies (; ). The analogous answers of students and teachers show the actual awareness of a significant part of young adults. These included their observations and perceptions; they often identify the Church exclusively with priests and bishops without feeling any bond with it and see the Church as an institution whose primary message concerns the distinction between what is good and what is bad, i.e., moral issues.

From a pastoral perspective, the results of the empirical research raise two issues. First, there is the matter of paying particular attention to family as an environment for religious and ecclesial formation, considering that it continues to influence a young adult and has significance as far as faith and the Church are concerned. This could involve various forms of pastoral support for parents, who are the primary bearers of the responsibility for the religious education of their children. The second issue concerns creating an image of the Church as a community of all the believers, and not only of the clergy. To this end, it would be necessary to initiate the abandonment of clericalism, which is quite common in Poland, while striving to establish the awareness that the Church constitutes a community of both the clergy and the laity. In practice, this may mean increasing openness to daily dialogue between the clergy and the laity and seeking space for cooperation.

3.2. What Do Young Adults Expect of the Catholic Church?

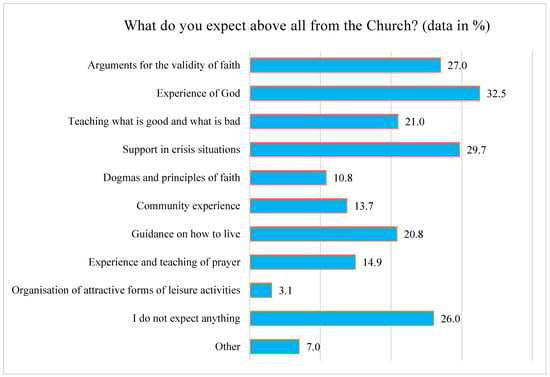

In the next part, the surveyed individuals were asked the following question: “What do you expect above all from the Church?”. After gaining knowledge about their attitudes towards the Church, the aim was to indicate which areas are primarily concerned and how the expectations of young people towards the Church are distributed. The questionnaire contained answers corresponding to the selected functions of the Church, understood in theological and sociological (religious, communal, moral, assistance-related) terms. The respondents were able to select up to three out of ten suggested answers and provide their own suggestions. Detailed data on the study are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Expectations of young adults towards the Church.

Young people most often expected the Church to allow them to “experience God” (32.5%), followed by the provision of “support in crisis situations” (29.7%) and “arguments for the validity of faith” (27.0%). One in four respondents expected nothing from the Church (26.0%), while one in five (20.8%) expected guidance on how to live. Females expected to experience God (36.0% vs. 28.6%; p = 0.014, Cramer’s V = 0.0780) and the sense of community more often than males (16.4% vs. 10.0%; p = 0.003, Cramer’s V = 0.093), while males more frequently admitted to expecting “dogmas and principles of faith” (9.1% vs. 13.2%; p = 0.041, Cramer’s V = 0.065) or claimed not to expect anything (22.8% vs. 29.6%; p = 0.014, V Cramer’s V = 0.078). In the case of the independent variable “place of residence”, a significant correlation was identified with regard to two answers: young adults from rural regions more often expected “to be taught what is good and what is bad” (23.6% vs. 18.0%; p = 0.032, Cramer’s V = 0.068) and less often claimed not to expect anything than those from the urban areas (23.0% vs. 29.0%; p = 0.0019, Cramer’s V = 0.074).

When teachers were asked the same question, the distribution of their responses was found to be very similar to that of young adults. Detailed data concerning these answers are included in Figure 3 below.

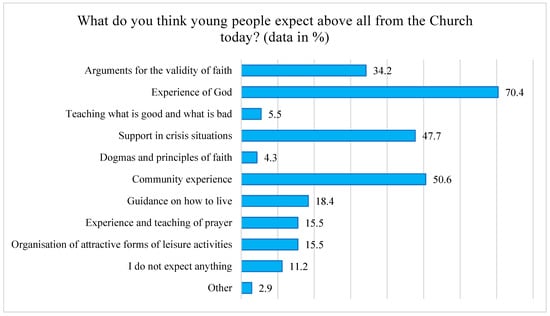

Figure 3.

Opinions of religious education teachers on young adults’ expectations towards the Church.

More than half of the surveyed teachers indicated that young adults primarily expect the Church to allow them to experience God (70.4%) and community (50.6%); nearly half pointed to support in crisis situations (47.7%), and one in three indicated an expectation for arguments for the validity of faith (34.4%). When analysing the young adults’ expectations towards the Church, it is interesting to note the similar percentage of the three most frequently selected answers: the wish to experience God, receive support in crisis situations and arguments for the validity of faith. The first and third expectations, selected by one in three respondents, refer to the basic relationship in the life of any person declaring religious faith—a relation with God. From a theological perspective, such a response relates to the essence of being a believer and the fundamental mission of the Church, as mentioned earlier in the article. The expectation of arguments for the validity of faith implies the need for rational content in the Church’s message and religious education. It may also point to a deficit in the Church’s education of young people, especially in situations of uncertainty; a clash with contemporary culture and its pluralism, syncretism and eclecticism; the need to justify one’s own beliefs; and the multiplicity of alternatives to faith.

The vast majority of the teachers stated that young people mainly expect the Church to allow them to experience God. This answer ranks first, while the remaining ones fall 20 percentage points behind. In the second place, teachers indicated the expectation to experience community and support in crisis situations. In turn, this observation brings to prominence the aspect of building relationships, showing the Church as a place where community may be experienced and where young people undergoing crises typical of this stage of development need to find support and feel a sense of community.

From a pastoral point of view, it is worth paying particular attention to the need to personally experience God and community, which was clearly emphasised by the surveyed group. This includes desires arising from the natural, spiritual and psychological needs of human beings, inherent in religion and their own constitution. At the same time, however, they indicate deficits and unfulfilled desires in this dimension of the Church’s activity in Poland. It is often perceived as a formalised institution, offering few possibilities for personal and communal experience of faith (). The expectations of young people constitute both a challenge and an opportunity for the Church to reformulate its current style of pastoral ministry towards the community by providing both individual and social religious experiences.

3.3. What Encourages Young People’s Faith Development?

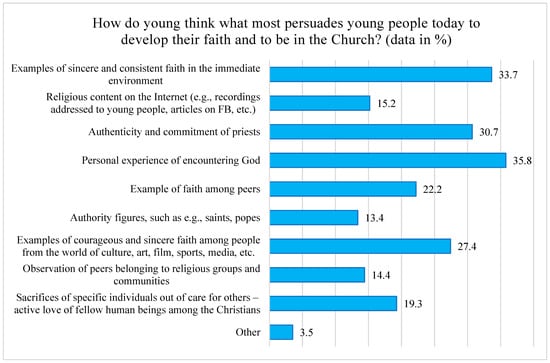

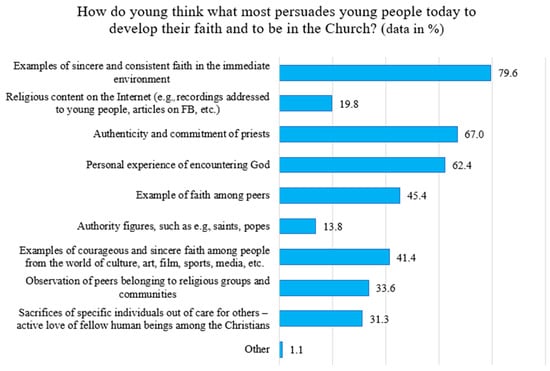

In the next question, the surveyed individuals were asked to indicate what, in their opinion, most convinces young people today to develop their faith and be part of the Church. The goal was to discover, from the perspective of a young person, what persuades their peers to practise their faith and what influences their decisions to be part of the institution. It is, therefore, a question about the factors that young people identify as significant in the discussed context. Each of the respondents was able to select up to five out of nine responses. Detailed data on this question are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Factors persuading young adults to develop their faith and be part of the Church.

The answer “personal experience of encountering God” achieved the highest rate (35.8%). Other most frequent answers included “examples of sincere and consistent faith in the immediate environment” (33.7%), “authenticity and commitment of priests” (30.7%), “examples of courageous and sincere faith among people from the world of culture, art, film, sports, media, etc.” (27.4%) and “example of faith among peers” (22.2%).

The variable “gender” revealed a significant statistical differentiation of the studied group with regard to the following answers: “religious content on the Internet as the factor that most persuades young people today to develop their faith and be part of the Church” (24.9% vs. 14.5%; p = 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.127), “authenticity and involvement of priests” (46.9% vs. 34.2%; p = 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.127), “authorities such as saints, popes” (15.4% vs. 22.3%; p = 0.0019, Cramer’s V = 0.018) and “examples of courageous and sincere faith among people from the world of culture, art, film, sports, media, etc.” (40.6% vs. 32.2%; p = 0.020, Cramer’s V = 0.086).

The second independent variable, i.e., the “place of residence”, showed a significant statistical differentiation within only one of the proposed responses. Rural residents were more likely to choose online religious content as a way of developing their faith and being part of the Church than urban residents (23.6% vs. 17.0%; p = 0.027, Cramer’s V = 0.081). The religious education teachers were asked the same question to assess what is crucial in persuading young people to develop their faith and be part of the Church from their own perspective. Detailed data on teachers’ opinions are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Opinions of religious education teachers on factors persuading young people to develop their faith and be part of the Church.

The surveyed teachers most often indicated “examples of sincere and consistent faith in the immediate environment” (79.6%), “authenticity and commitment of priests” (67.0%) and “personal experience of encountering God” (62.4%). Nearly half of the respondents chose the “example of faith among peers” (45.4%) and “examples of courageous and sincere faith among people from the world of culture, art, film, sports, media, etc.” (41.4%). It is worth noting that the young adults participating in the study more frequently indicated the importance of the testimony of faith among people from the world of culture, art, film, sports, media, etc., than examples of faith among peers.

The juxtaposition of the teachers’ and students’ answers to the above question implies several observations. The three most frequent answers are the same for both groups; the only changing variables are order and frequency. As in the previous question, the young adults emphasised the personal experience of encountering God as the element persuading their peers to develop faith and be part of the Church. The most frequent motive and argument selected by the respondents to maintain faith and stay in the Church’s orbit is therefore a personal relationship with the sacrum. From the pastoral perspective, this piece of information is extremely valuable and opens space for reflection on today’s model of the Church’s functioning and its attempts to strengthen the communal dimension.

Other answers provided by the respondents refer to examples of sincere and consistent faith among close and distant people in their environment. The emphasis placed on the importance of examples of faith in shaping the religiousness of young adults is very clear among the surveyed religious education teachers. While this factor was quoted by approximately 30% of young adults (it is among the most frequently chosen answers), nearly 80% of teachers indicated examples from the immediate environment. The latter also highly value the attitudes of priests and personal experience of God (over 60%). Approximately half of those in second place selected examples of faith among peers and famous persons from the world of culture. In summary, both from the perspective of young adults and based on the observations made by teachers, personal religious experience and encounters with attitudes of consistent faith, authenticity, courage and commitment, including among the clergy, have the utmost importance for developing faith and being part of the Church.

From a pastoral perspective, it is necessary to draw a practical conclusion from the research to attach more importance to the testimony of faith as an effective method of religious, including ecclesial, formation. The testimony of conformity between one’s lifestyle and life choices, on the one hand, and the message of the Gospel combined with the teaching of the Church, on the other, is a convincing argument for their credibility. This is especially true of decisions involving a dose of renunciation and sacrifice. Their acceptance for religious reasons is an indication of a genuine commitment to these values.

3.4. Activities Needed by Young Adults from the Catholic Church

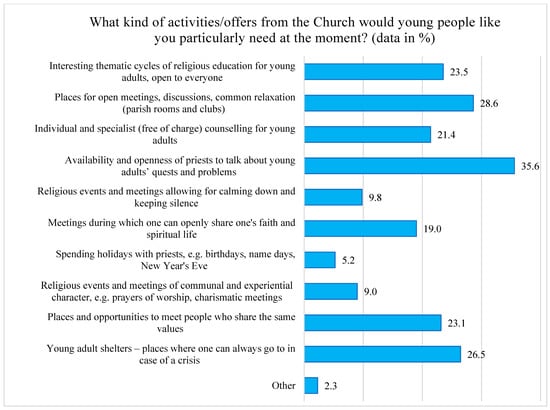

The picture of young adults’ personal attitudes towards the Church, its conditions and their expectations towards the institution was to be supplemented with answers to the following question: What kind of activities/offers provided by the Church are particularly necessary in young people’s opinion? In this way, the respondents were guided through reflection on their own attitudes towards the Church: what they expect from it, what does and does not persuade them to develop their faith and be part of the Church and specific proposals, i.e., types of activities and offers particularly needed by young adults. They could choose up to five answers from the proposed list. Detailed data on this study are presented in the Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Types of activities/offers provided by the Church that are especially needed by young adults (data in %).

The most frequently selected answers included: “availability and openness of priests to talk about young adults’ quests and problems” (35.6%), “places for open meetings, discussions, common relaxation, parish rooms and clubs” (28.6%), “young adult shelters—places where one can always go to in case of a crisis” (26.5%), “interesting thematic cycles of religious education for young adults, open to everyone” (23.5%) and “places and opportunities to meet people who share the same values” (23.1%).

The independent variables revealing a significant statistical differentiation for some answers included gender; males indicated that the “open meetings, discussions, common relaxation, parish rooms and clubs” are especially needed by young adults from the Church more often than females (46.6% vs. 33.2%; p = 0.0001, Cramer’s V = 0.135). In contrast, females were more inclined to choose “individual and specialist (free of charge) counselling for young adults” (34.6% vs. 20.7%; p = 0.0001, Cramer’s V = 0.151), “availability and openness of priests to talk about young adults’ quests and problems” (52.0% vs. 42.8%; p = 0.014, Cramer’s V = 0.091) and “young adult shelters—places where one can always go to in case of a crisis” (44.0% vs. 24.0%; p = 0001, Cramer’s V = 0.205). Urban residents were more willing than rural residents to select individual and specialist (free of charge) counselling for young adults (34.0% vs. 25.3%; p = 0.010, Cramer’s V = 0.094%), as well as religious events and meetings of communal and experiential character, e.g., prayers of worship, charismatic meetings (14.5% vs. 9.3%; p = 0.032, Cramer’s V = 0.079).

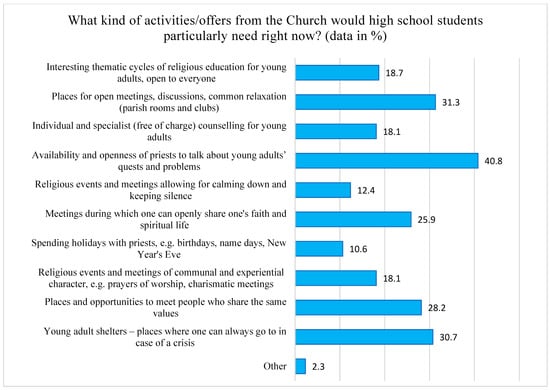

Similar to the students surveyed, teachers taking part in the study were also asked to answer the question about activities and offers provided by the Church that they believe are particularly needed by young people (secondary school students) today. Detailed data on this question are included in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Opinions of religious education teachers on types of activities/offers provided by the Church that are particularly needed by young people.

The five most frequent answers were the “availability and openness of priests to talk about young adults’ quests and problems” (40.8%), “places for open meetings, discussions, common relaxation” (31.3%), “young adult shelters—places where one can always go to in case of a crisis” (30.7%), “places and opportunities to meet people who share the same values” (28.2%) and “meetings during which one can openly share one’s faith and spiritual life” (25.9%).

It is interesting to note that the answer to the question about the type of activities/offers provided by the Church that are particularly needed by young people today according to the students and teachers surveyed, which was selected most often in both groups, was the “availability and openness of priests to talk about young adults’ quests and problems”. They agreed that this is the most necessary to provide.

The second place of the most frequently selected answers, with a slightly lower percentage of indications in the case of the students and teachers alike, was taken by “places for open meetings, discussions, common relaxation (parish clubs and room)” and “young adult shelters—places known to provide help in crisis situations”. Among teachers, they are followed by “places and opportunities to meet people who share the same values”. Young adults also chose this answer, as well as, with slightly greater frequency, “(interesting) thematic cycles of open religious education for young adults”. This comparison draws attention to the conviction that the Church needs to offer places and spaces for meetings, relationships, exchange of opinions, support and spending time together. The similarity between the observations of students and teachers is very telling in this regard.

From a pastoral perspective, the results of the sociological survey conducted compel one to rethink the current style of pastoral care and religious formation. It is worth placing particular emphasis on creating and providing young adults with various spaces to allow encounters, acceptance, dialogue and action. Special attention should be paid to dialogue about the existential problems of young adults in order to build empathy and offer tangible help.

4. Conclusions

When attempting to answer the question of how Polish young adults perceive their relationship with the Church, it is worth noting that this relationship is most often based on the tradition handed down by their parents and family. Consequently, it is often not a personal bond with the Church, which results in internalised beliefs and involvement in its life. However, the sociological research at hand shows that rather than being indifferent to the Church, young people expect a place where they can personally experience God and community. The fact that some individuals see it only as an institution teaching about moral issues should also not be overlooked. Irrespective of the reasons behind this perception, this is an important message for the Church—one that raises the question of what factors, on its part, elicit such a narrow view and what could be changed in this area.

Empirical research shows that young adults primarily expect the Church to provide them with the availability of priests, their readiness to meet and offer their time, and physical space, a place where young people can meet and spend time together. Personal religious experience, which was frequently indicated by the young adults being studied in various questions, is expected but requires external conditions that allow this type of experience to flourish. Teachers observing young adults also notice their need for religious experience, as well as availability, openness and support from priests. By contrast, a significant discrepancy between the declarations made by the young adults surveyed and the observations made by the teachers concerned attractive forms of leisure time activities and the experience of community as the main expectation of the former towards the Church. Teachers indicated the former answer five times, and the latter almost four times, more often than the young adults.

Hostility towards the Church was declared by one in eight respondents; however, indifferent attitudes of varied intensity are much more common. This group includes one in five young adults for whom the Church is simply one of many institutions, and one in four respondents who identify the Church with priests and bishops and feel no bond with it. Some young people participate in religious practices but do not feel any bond with the Church community and do not expect anything from the institution. All of these responses pose a challenge for the institutional Church, which should become seriously and practically concerned about building ecclesiastical awareness among the clergy, the faithful, the laity, and especially among young adults.

From the sociological perspective, it is worth noting that the independent variables of “gender” and “place of residence” analysed in this article generally did not show a significant statistical differentiation for the most frequently chosen answers proposed in the survey questionnaire. The percentages for both males and females, as well as rural and urban residents, were similar. Differences could be found in the independent variables concerning answers to questions selected less frequently by the young adults surveyed.

It is beneficial to listen to the desires of young adults presented in sociological studies. In order to fulfil them, it is necessary to change the mentality of people responsible for the Church and their involvement in renewing the way it is functioning. These actions should result in a reconstruction of the pastoral model in Poland and the abandonment of clericalism and formalism in favour of creating opportunities for the clergy and the lay faithful, especially young ones, to experience a sense of belonging to the Church and parish community, expressed in ordinary daily experiences of being with other people—including shared prayer (of the clergy and the laity), liturgy, meetings and religious formation, the possibility to exchange experiences, support in a crisis, mutual concern for various dimensions of the functioning of local parish communities, sharing responsibility for certain areas, etc., in the spirit of faith. It is also necessary to build experiences of a more democratic community that attaches greater value to laypeople.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S.; methodology, W.S.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, W.S., P.M.M., T.A.; data curation, W.S., P.M.M., T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S., P.M.M., T.A.; writing—review and editing, W.S., P.M.M., T.A.; visualization, T.A.; project administration, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article is a part of the project funded by the Ministry of Education and Science, Republic of Poland, “Regional Initiative of Excellence” in 2019–2022, 028/RID/2018/19, the amount of funding: 11 742 500 PLN.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (protocol code 02/DKE/NS/2020 and date of approval: 10 February 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found at https://repozytorium.kul.pl/ (1 June 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamczyk, Tomasz. 2020. Autentyczność i duchowość. Księża w opinii polskiej młodzieży—Analiza socjologiczna. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Baniak, Józef. 2015. Kościół instytucjonalny w Polsce w wyobrażeniach i ocenach młodzieży licealnej i akademickiej: Od akcepcji do kontestacji. Konteksty Społeczne 1: 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boguszewski, Rafał, and Marta Bożewicz. 2019. Religijność i moralność polskiej młodzieży—Zależność czy autonomia? Zeszyty Naukowe KUL 62: 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2005. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- Ebertz, N. Michael. 2017. Europa: Eine immer komplexere und ausdifferenzierte Gesellschaft. Junge Menschen zwischen Immanentz und Transcendenz. Studia Pastoralne 13: 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Głowacki, Antoni. 2019. Religijność młodzieży i uczestnictwo w lekcjach religii w szkołach. In Młodzież 2018. Edited by Mirosława Grabowska and Magdalena Gwiazda. Warszawa: Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, pp. 153–69. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, Mirosława. 2021. Religijność młodych na tle ogółu społeczeństwa. Komunikat z badań nr 144/2021. Warszawa: CBOS. [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu-Leger, Danièle. 2003. Individualism and the Validation of Faith and the Social Nature of Religion in Modernity. In The Blackwell Companion to Sociology of Religion. Edited by R. K. Fenn. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 161–75. [Google Scholar]

- Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego. 2021. Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia. Warszawa: ISKK. [Google Scholar]

- Janaszek-Ivaničková, Halina. 2002. Nowa twarz postmodernizmu. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Franz-Xaver. 2011. Kirchenkrise. Wie erlebt das Christentum? Freiburg im Breisgau: Verlag Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, William K., and Leslie J. Francis. 1996. Drift from the Churches: Attitudes towards Christianity during Childhood and Adolescence. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierska, Kaja. 2018. Młodzież Archidiecezji Łódzkiej. Szkic do portretu. Łódź: Archidiecezjalne Wydawnictwo Łódzkie. [Google Scholar]

- Kiełb, Dominik, and Paweł Mąkosa. 2021. Between personal faith and facade religiosity. Study on youth in the south-eastern Poland. European Journal of Science and Theology 17: 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch, Hubert. 2018. Individualisierung, Privatisierung und Subjektivierung. In Handbuch Religionssoziologie. Edited by Detlef Pollack, Volkhard Krech, Olaf Müller and Markus Hero. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, pp. 329–46. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżak, Tomasz. 2020. Sondaż: Kościół w błyskawicznym tempie traci wiernych. Rzeczpospolita 15 November 2020. Available online: https://www.rp.pl/kosciol/art422501-sondaz-kosciol-w-blyskawicznym-tempie-traci-wiernych (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Mąkosa, Paweł. 2009. Katecheza młodzieży. Stan aktualny i perspektywy rozwoju. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Mąkosa, Paweł. 2017. Zwischen orthodoxem Katholizismus und Individualisierung der religiösen Überzeugungen der Polen. Religionen Unterwegs 23: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2006. Sekularyzacja i desekularyzacja w nowoczesnym świecie. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2008. Emigracja z Kościoła. Religijność młodzieży polskiej w warunkach zmian społecznych. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2014. Postawy Polaków wobec Kościoła katolickiego—Analiza socjologiczna. Zeszyty Naukowe KUL 57: 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2018. Kondycja religijna i moralna młodzieży szkół średnich w latach 1988-1998-2005-2017. Toruń: Adam Marszałek. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2021. Scenariusze przemian religijności Kościoła katolickiego w społeczeństwie polskim. Studium diagnostyczno-prognostyczne. Lublin: Wyższa Szkoła Nauk Społecznych. [Google Scholar]

- Mikołejko, Zbigniew. 2020. Jak zmieniła się religijność Europejczyków. Przypadek katolicyzmu. In Polska—Europa. Wyniki Europejskiego Sondażu Społecznego 2002–2018/19. Edited by Paweł B. Sztabiński, Dariusz Przybysz and Franciszek Sztabiński. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Filozofii i Socjologii PAN, pp. 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Olaf. 2013. Kirchlichkeit und Religiosität in Ostittel- und Osteuropa. Entwicklungen—Muster—Bestimmungsgründe. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018a. Being Christian in Western Europe. Available online: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2018/05/14165352/Being-Christian-in-Western-Europe-FOR-WEB1.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Pew Research Center. 2018b. Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities and Key Social Issues. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/eastern-andwestern-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Richter, Philip J., and Leslie J. Francis. 1998. Gone but Not Forgotten: Church Leaving and Returning. London: Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Rusek, Halina. 2018. Young People—Religion—The Church in the Sociological Perspective. Continuations. Przegląd Religioznawczy—The Religious Studies Review 4: 113–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sadłoń, Wojciech. 2021. Religijność Polaków, w: Kościół w Polsce. Raport. Warszawa: Katolicka Agencja Informacyjna, s., pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Skoczylas, Kazimierz. 2017. Stosunek do Kościoła młodzieży Kujaw wschodnich. Studia Włocławskie 19: 609–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowska, Ewa. 2019. Religijność młodzieży w Europie—Perspektywa socjologiczna. Kontynuacje. Przegląd Religioznawczy 3: 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. 2021. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland; Edited by Dominik Rozkrut. Warszawa: Statistics Poland.

- Steinfels, Peter. 2004. A People Adrift: The Crisis of the Roman Catholic Church in America. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak, Wioletta. 2018. Społeczny odbiór autorytetu i misji Kościoła w Polsce. In Bunt mas czy kryzys elit? Edited by Aniela Dylus and Sławomir Sowiński. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo TUM, pp. 257–87. [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak, Wioletta. 2020. Interdisciplinarity in Pastoral Theology. An Example of Socio-Theological Research. Verbum Vitae 38: 503–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbańska, Beata. 2021. Religijność młodych Polaków: Ucieczka od religii czy od Kościoła? In Młodzi dorośli: Identyfikacje, postawy, aktywizm i problemy życiowe. Edited by Katarzyna Skarżyńska. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo SGGW, pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Kenneth D. 2000. One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic: The Early Church Was the Catholic Church. Ignatius Press: San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).