The Religious Plot in Museums or the Lack Thereof: The Case of Islamic Art Display

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Background of Islamic Museology

3. Postcoloniality and the Western Concept of the Museum

4. The Question of the Sacred in the Museum

5. From the Critique of the Museum to the Critique of the Curatorship

6. Are Islamic Art and Artifacts “Islamic”?

“Any critical work that does not fit into the current orthodoxy or into some dubious notions of ‘ethics’ is framed as ‘essentializing’. This is indeed a clever way to shut down the discussion by trumping up a series of false moral charges. I can go further. I also suspect that the post-colonialist allergy to ‘essentialism’ is equally myopic. With respect to my own case, the truth is that I am an equal ‘essentializer’”.

Interfaith Hybridization in the Muslim Artworld

7. Religious Introversion in the Traditional Islamic Art Displays

A Blogger’s Experience in the MET’s Islamic Galleries

8. “Secular Scholasticism” of the Narratives and Conservative Installation Design

Islam as a Theme among Other Themes

9. Epilogue: The Future Resides in the New Muslim Museology

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For terminological clarity, art and artifacts form two distinct categories that belong to the broad ensemble of things called “material culture”. While all artworks are artifacts, namely objects created for a certain function with certain skills or a certain artistry, the reverse is not true. Unlike artifacts, artworks present a scope of meaning and cognitivity beyond functional efficacy, possess a metaphysical and affective dimension, and express deep thoughts either articulated by a high level of aesthetic research and experiment or as the result of a long history of these researching and experimenting processes. The ontological line separating art from artifacts is, however, mobile and often blurred. |

| 2 | This issue has been discussed in a variety of publications: in the paragraph entitled “Social-historical Background of Islamic Art Curation,” in (Gonzalez 2018; Demerdash-Fatemi 2020, pp. 15–30; Shatanawi 2012a, pp. 177–92; Grinell et al. 2019, pp. 370–71). |

| 3 | Rebecca Bridgman in the booklet of the conference, From Malacca to Manchester 20. See also (Weber 2018, pp. 237–61; Grinell et al. 2019, pp. 370–71). |

| 4 | The state of affairs of the studies and curation of non-Western material cultures obviously varies depending on the areas concerned. This discussion deals only with the Islamic scholarship and curatorship. For an updated reflection on post-colonialism thought, see (Gandhi 2019). |

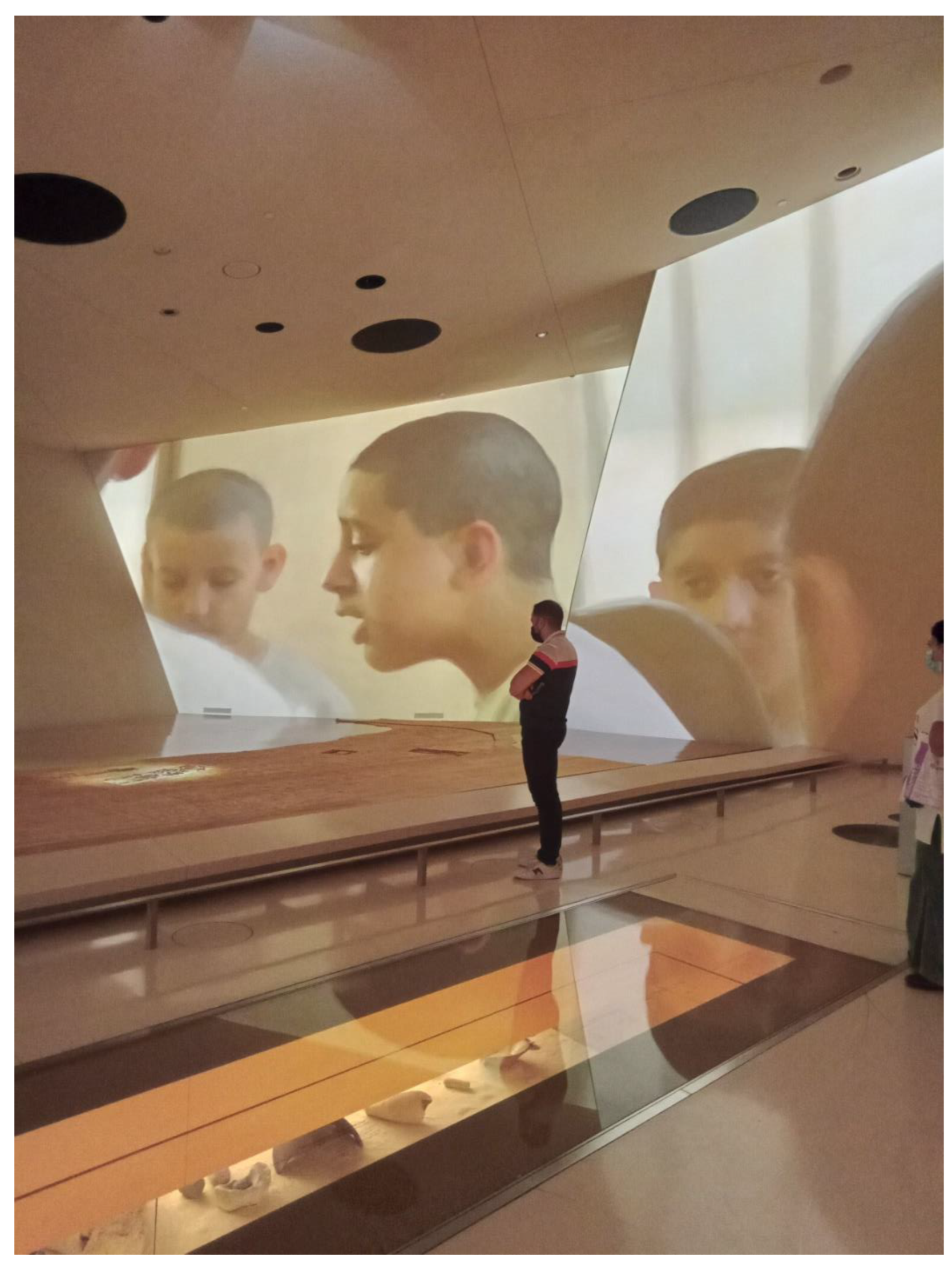

| 5 | (Shaw 2019, p. 221). See my review of this problematic book in (Gonzalez 2020). |

| 6 | Wendy M.K. Shaw holds firmly this view. See (Shaw 2002, pp. 133–55). |

| 7 | See the account from the museum’s inception in the aftermath of the French Revolution up to nowadays by (Exell 2017, pp. 49–64). |

| 8 | A remarkable installation proving this malleability of the museum, “Exposing the Public,” was conceptualized and is discussed by (Bal 2006, pp. 525–42). |

| 9 | See https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/past/the-sacred-made-real and https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2021/11/11/culture/koreanHeritage/pensive-bodhisattva-national-museum-of-korea-pensive-bodhisattva/20211111160231358.html (accessed on 8 March 2022). See also my references to some powerful religious installations in East Asian museums, in particular in Korea, in (Gonzalez 2018). This article critiques some key museums and galleries of Islamic art. |

| 10 | (Searle 2009). My own critical description is based on my visit of this show. |

| 11 | Here the term “materialism” refers to the recent trend of religious studies that emphasizes the role of objects and materiality in the exercise of piety. |

| 12 | I discuss some of these issues in “Islamic Art Curation in Perspective”. |

| 13 | See the introduction and articles in the online (Journal of Art Historiography 2012), “Islamic Art Historiography,” and (Lanwerd 2012, p. 206). For a critique of this view see (Ahmed 2015; Gonzalez 2016, pp. 5–14). |

| 14 | This term “Islamicate” was famously coined by Marshall Hogdson, in (Hogdson 1974). |

| 15 | (Ahmed 2015). A sample of this scholarship also includes (O’Meara 2020; Shatanawi 2014; Akkach 2005; Gonzalez 2001, 2019; Elias 2012). |

| 16 | See the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KWkyF02YdA4 (accessed on 8 March 2022). |

| 17 | Heba Nayel Barakat in the booklet of the conference, From Malacca to Manchester p. 34. Mirjam Shatanawi faced similar challenges when she curated and studied the similarly Islamic eclectic collections of the ethnographic Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, ranging from historic and colonial-era artifacts, household items, to popular art and contemporary creations from South East Asia, the Middle East, to Africa and the Caribbean. See (Shatanawi 2014). |

| 18 | The literature dealing with this museology is plentiful. See for example, (Rey 2019a, 2019b, 2022; Blessing 2018; Bier 2017). |

| 19 | I wish to mention but not to discuss the issue of the representation of Prophet Muhammad in museums that ensued the infamous cartoons affair. For this topic, see (Grinell 2019b, pp. 1–13). |

| 20 | Nasser Rabbat on Twitter, https://twitter.com/nayelshafei/status/1089659395519205376 (accessed on 8 March 2022). See also (Rabbat 2012), https://www.artforum.com/print/201201/the-new-islamic-art-galleries-at-the-metropolitan-museum-of-art-29813 (accessed on 8 March 2022), and (Porter and Greenwood 2020). |

| 21 | (Grinell 2020, p. 31). It must be noted that, in their writings, curators of Islamic art often theorize against didacticism and narrative complexity in the museum, and thereby assert the benefit of the objects’ phenomenology. However, they do not follow suit in their practice, as Grinell demonstrates in his sharp critique of the renovated Museum of Islamic art in Berlin in this same article, pp. 38–41. |

| 22 | About this Soudanese lyre, see https://islamicworld.britishmuseum.org/collection/EAF40250/ (accessed on 8 March 2022). |

| 23 | See the accounts on these exhbitions by (Porter and Abdel Haleem 2012; Tamimi Arab 2020, pp. 1–4). |

| 24 | About these new Islamic museums see: (Trevathan 2020, pp. 119–33); and (Mirrors of Beauty, Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia Guide 2020; Rey 2019a, 2019b; Shaw 2010, pp. 129–31). About the Museum of Islamic art in Doha, see my critique in (Gonzalez 2018). For a collection of concisely critical essays on the museums in Qatar and the Arabian Peninsula, see the (Journal of Arabian Studies 2017). |

| 25 | See the report on this museum by (Junker 2020), in this website: https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/off-the-screen-and-off-the-charts-at-qatar-s-newest-museum-20200220-p542qz (accessed on 8 March 2022). |

References

- Ahmed, Shahab. 2015. What Is Islam, the Importance of Being Islamic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Akkach, Samer. 2005. Cosmology and Architecture in Premodern Islam: An Architectural Reading of Mystical Ideas. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- al-Hijjawi al-Qaddumi, Ghada. 1996. Book of Gifts and Rarities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Nadia. 2020. The Road from Decadence: Agenda and Personal Histories in the Study of Early Islamic Art. In Empires of Faith in Late Antiquity. Edited by Jas Elsner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke. 2006. Exposing the Public. In A Companion Museum to Studies. Edited by Sharon McDonald. Malden, Oxford and Carlton: Blackwell, pp. 525–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bier, Carol. 2017. Reframing Islamic Art for the 21st Century. Horizons in Humanities and Social Sciences 2: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blessing, Patricia. 2018. Presenting Islamic Art: Reflections on Old and New Museum Displays. Review of Middle East Studies 52: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, Sam. 2017. Not Malacca but Marege: Islamic Art in Australia (or, ‘What Have the Umayyads Ever Done for Us?’). In From Malacca to Manchester, Curating Islamic Collections Worldwide. Manchester: Manchester Museum, p. 47. Available online: http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=31514 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Brown, Karen, and François Mairesse. 2018. The definition of the museum through its social role. Curator: The Museum Journal 61: 525–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerdash-Fatemi, Nancy. 2020. Objects, Storytelling, Memory and Living Histories: Curating Islamic Art Empathically in an Era of Trauma and Displacement. In Curating Islamic Art Worldwide, from Malacca to Manchester. Edited by Jenny Norton-Wright. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, Carol. 1991. Art Museums and the Ritual of Citizenship. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Edited by Ivan Karp and Stephen D. Lavine. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, Jamal J. 2012. Aisha’s Cushion, Religious Art, Perception and Practice in Islam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exell, Karen. 2017. Utopian Ideals, Unknowable Futures, and the Art Museum in the Arabian Peninsula. Journal of Arabian Studies 7: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exell, Karen, and Trinidad Rico. 2013. There is no heritage in Qatar’: Orientalism, colonialism and other problematic histories. World Archaeology 45: 670–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exell, Karen, and Sarina Wakefield, eds. 2016. Museums in Arabia, Transnational Practices and Regional Processes. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, Leela. 2019. Postcolonial Theory, A critical Introduction, 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2001. Beauty and Islam, Aesthetics of Islamic Art and Architecture. London and New York: IBTauris. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2016. Contesting the Conceptual Categories ‘Islamic Civilization, Art or Masterpiece’: A Reflection on the Problem. Kimiya-Ye-Honar Quaterly 17: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2018. Islamic Art Curation in Perspective: A Comparison with East Asian Models through the Case of the Leeum Samsung Museum. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 16: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2019. Aesthetics in Surat al-Mulk: Mathematical Typology as Metaphysical Mirror. Darulfunun Ilahiyat, Journal of Darulfunun Faculty of Theology 39: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Valerie. 2020. What Is Islamic Art? Between Religion and Perception. Al-Masāq 32: 110–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinell, Klas. 2014. Der Islam—Ein aspekt zeitgenössiger Weltkultur. In Experimentierfeld Museologie: Internationale Perspektiven auf Museum, Islam und Inklusion. Edited by Susan Kamel and Christine Gerbich. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Grinell, Klas. 2019a. Preliminary Notes towards a Soteriological Analysis of Museums. ICOFOM Study Series 47: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinell, Klas. 2019b. Muhammad at the Museum: Why the Prophet is not Present. Religions 10: 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinell, Klas. 2020. Labelling Islam: Structuring Ideas in Islamic Galleries in Europe. In Curating Islamic Art Worldwide, from Malacca to Manchester. Edited by Jenny Norton-Wright. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinell, Klas, Magnus Berg, and Göran Larsson. 2019. Museological Framings of Islam in Europe. Material Religion 15: 370–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour Loumer, Saeid. 2014. Quranic Themes and Reflections in Islamic Art and Architecture. Trends in Life Sciences 3: 474–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hogdson, Marshall. 1974. The Venture of Islam, The Classical Age of Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- ICOFOM Studies Series. 2019. Museology and the Sacred. 2019. Paris: ICOFOM, vol. 47, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Journal of Arabian Studies. 2017. CIRS Special Issue. Doha: Center for International and Regional Studies, Georgetown University in Qatar, vol. 7, p. 1.

- Journal of Art Historiography. 2012. Islamic Art Historiography. Available online: https://arthistoriographywordpress.com/number-6-june-2012-2/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Junker, Ute. 2020. Off the Screens and off the Charts at Qatar’s Newest Museum. Life and Leisure. Available online: https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/off-the-screen-and-off-the-charts-at-qatar-s-newest-museum-20200220-p542qz (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Junod, Benoît, Georges Khalil, and Stephen Weber, eds. 2012. Islamic Art and the Museum, Approaches to Art and Archaeology of the Muslim World in the Twenty-First Century. London: Saqi Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam, Tazim R. 2006. Ethics and Aesthetics in Islamic Art. The Ismaili USA, 5–7. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/219166521/Ethics-and-Aesthetics-in-Islamic-Arts (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Kitchens, Sharon. 2020. Three Empire at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/fa22b665c7894790b1b0441d0593289c (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Kreps, Christina. 2006. Non-Western Models of Museums and Curation in Cross-cultural Perspective. In A Companion Museum to Studies. Malden, Oxford and Carlton: Blackwell, pp. 457–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lanwerd, Susanne. 2012. Do You Speak Islamic Art? The Museological Laboratory. In Islamic Art and the Museum, Approaches to Art and Archaeology of the Muslim World in the Twenty-First Century. London: Saqi Books, p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Sharon, ed. 2006. A Companion to Museum Studies. Malden, Oxford and Carlton: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Masteller, Kimberly. 2020. Curating Islamic Art in the Central United States: New Approaches to Collections, Installations and Audience Engagement. In Curating Islamic Art Worldwide, from Malacca to Manchester. Edited by Jenny Norton-Wright. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Messias Carbonell, Bettina, ed. 2012. Museum Studies: An Anthology of Context. Malden, Oxford and Carlton: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Mirrors of Beauty, Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia Guide. 2020. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

- Nayel Barakat, Heba. 2017. From Malacca to Manchester, Curating Islamic Collections Worldwide. Manchester: Manchester Museum, pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara, Simon. 2020. KaE ba Orientations: Readings in Islam’s Ancient House. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Venetia, and Muhammad A. S. Abdel Haleem. 2012. Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Venetia, and William Greenwood. 2020. Displaying the Cultures of Islam at the British Museum: The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World. In Curating Islamic Art Worldwide, from Malacca to Manchester. Edited by Jenny Norton-Wright. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbat, Nasser. 2012. The Islamic Art Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artforum. Available online: https://www.artforum.com/print/201201/the-new-islamic-art-galleries-at-the-metropolitan-museum-of-art-29813 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Rey, Virginie. 2019a. Islam, Museums, and the Politics of Representation in the West. Material Religion 15: 250–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, Virginie. 2019b. Mediating Museums, Exhibiting Material Culture in Tunisia, 1881–2016. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, Virginie. 2022. From “Islamic Art” to “Muslim Heritage”: A Survey of Material and Visual Cultures in Museums of Europe and Beyond. In Archaeology, Politics and Islamic Cultural Heritage in Europe. Edited by David Govantes-Edwards. London: Equinox, pp. 183–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, Trinidad. 2019. Islam, Heritage, and Preservation: An Untidy Tradition. Material Religion 15: 148–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, Adrian. 2009. Torture and Trancendence at the National Gallery’s Sacred Made Real. The Guardian. October 19. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/oct/19/national-gallery-sacred-made-real (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Shatanawi, Mirjam. 2012a. Curating against Dissent: Museums and the Public Debate on Islam. In Political and Cultural Representations of Muslims, Islam in the Plural. Edited by Christopher Flood, Galina Miazhevitch and Henri Nickles. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 177–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shatanawi, Mirjam. 2012b. Engaging Islam: Working with Muslim Communities in a Multicultural Society. Curator: The Museums Journal 55: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatanawi, Mirjam. 2014. Islam at the Tropenmuseum. Volendam: LM Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Wendy M. K. 2002. Tra(ve)ils of Secularism, Islam in Museums from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic. In The Invention of Religion, Rethinking Belief in Politics and History. Edited by Derek R. Peterson and Darren R. Walhof. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, pp. 133–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Wendy M. K. 2003. Possessors and Possessed: Museums, Archaeology, and the Visualization of History in the Late Ottoman Empire. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Wendy M. K. 2010. Between the Secular and the Sacred, a New Face for the Department of the Holy Relics at the Topkapı Palace Museum. Material Religion 6: 129–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Wendy M. K. 2019. What Is Islamic Art? Between Religion and Perception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi Arab, Pooyan. 2020. Longing for Mecca (Verlangen naar Mekka). Material Religion 16: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevathan, Idries. 2020. Islamic Art and Saudi Arabia: Reconnecting Communities with Collections. In Curating Islamic Art Worldwide, from Malacca to Manchester. Edited by Jenny Norton-Wright. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 119–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vernoit, Stephen. 2000. Discovering Islamic Art: Scholars, Collectors and Collections, 1850–1950. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Wazeri, Yehia Hassan. 2020. Architecture in the Islamic Vision. Journal of Islamic Architecture 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Stefan. 2018. Pulling the Past into the Present: Curating Islamic Art in a Changing World, a Perspective from Berlin. International Journal of Islamic Architecture 7: 237–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonzalez, V. The Religious Plot in Museums or the Lack Thereof: The Case of Islamic Art Display. Religions 2022, 13, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040281

Gonzalez V. The Religious Plot in Museums or the Lack Thereof: The Case of Islamic Art Display. Religions. 2022; 13(4):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040281

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez, Valerie. 2022. "The Religious Plot in Museums or the Lack Thereof: The Case of Islamic Art Display" Religions 13, no. 4: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040281

APA StyleGonzalez, V. (2022). The Religious Plot in Museums or the Lack Thereof: The Case of Islamic Art Display. Religions, 13(4), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040281