3.1. Aims and Context

In Taiwan, I observed what was called a “Classics Reading” (

dujing 讀經) class in the Miaoshan Kindergarten 妙善幼兒園 in the Neihu ward of Taipei City. This kindergarten is a regular, city-certified, private kindergarten (

Taipeishi shili tuoersuo) for children aged 3 to 6 years old. The kindergarten is run by the Bliss and Wisdom Culture and Education Foundation (

fuzhi wenjiao jijinhui 福智文教基金會), a national lay-Buddhist organization in Taiwan which also has some members and activities in other Chinese-speaking countries, including mainland China.

5 Like the Neihu area where it is located, the social-economic dynamic of the school is mixed, but with a lower middle class base. The school waived fees for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, and was also unusually open to children on the autistic spectrum, with ADHD and similar conditions.

The kindergarten experience in Taipei is seen as preparation for elementary school, and is therefore perceived primarily as a place of learning rather than simply a childcare facility. The teachers are qualified kindergarten teachers licensed by the City of Taipei under the auspices of the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China (Taiwan). In other words, they are all trained and qualified child pedagogues. In fact, this particular kindergarten was a training destination for student teachers as part of their college qualification—one was present in the lower class during my fieldwork.

The general ethos and practice of the teachers, therefore, is primarily informed by mainstream, modern theories of early childhood pedagogy, including early childhood education’s role in socializing children and introducing them to the basics of numeracy and literacy. However, the teachers also subscribe to the educational philosophical outlook of the Bliss and Wisdom Foundation, which sponsors the kindergarten. Although all are trained in standard pedagogy in the state-approved system, they also clearly have an alternative outlook on children and society. This is evidenced by the way they deal with children from minority backgrounds and students with autism, ADHD, and similar conditions, all of whom they engage wholeheartedly in the school, unlike some other kindergartens which may see dealing with diversity as a distraction from preparation for competitive examination performance. It is also noteworthy that, as per the global norm in these professions, all teachers and the principal of the pre-school were women. The principal would have been aged in her 40s, and most of the teachers in their 30s.

Miaoshan pre-school provided childcare and early childhood education to local people in Neihu for over 10 years before the introduction of readings of Confucian texts. The introduction of the reading of Confucian texts was inspired by the use of Confucianism advocated by the spiritual leader (or master) of the Bliss and Wisdom Foundation, Master Richang (Shi Richang 釋日常 (lay/birth name: Huang Jingsheng 黃靜生)) (1929–2004). Although leading a Buddhist organization, Richang valued Confucian texts because he saw Confucian texts as encouraging ethical behavior contributing to the larger goals of Buddhism. In other words, he saw Confucianism and Confucian texts in instrumental terms, as a means to encourage forms of behavior and action which would in turn lead to individuals and society being more in tune with Buddhist ideals. This approach interacts with the Buddhist concept of “expedient means” (upaya (Sk.) fangbian (Ch.) hōben (Jp.) 方便), which has long been used in traditional East Asia to legitimate the use of Confucian and other non-Buddhist texts and practices within Buddhist institutions (

Pye 2003). In this case, Confucianism is seen as providing an ethical education, with those ethics supporting a larger Buddhist worldview. This vision also has clear intersections with early childhood education’s objective of the socialization of children.

The primary activity in the use of Confucianism in this kindergarten, and the element I observed in the daily routine of this kindergarten, is called “Classics Reading” (dujing 讀經). Despite the kindergarten being Buddhist, five of the six “Classics” read are Confucian books, mainly Neo-Confucian pedagogical and moral primers comprising texts collated between the Song and Qing dynasties. Although the activity is called “Classics Reading” as an activity, the actual action of reading the text is not referred to as reading (du 讀), but rather as “recitation” (bei or beisong 背誦). As we will see below, the act of “recitation”, following traditional Neo-Confucian approaches, themselves influenced by Buddhist practices, seems to be seen as key to the act of “reading”.

The stated aims of the school in introducing this “Classics Reading” activity into the curriculum are twofold. The first aim is to introduce to the children “a principle of learning” in which learning itself is seen as a regular daily activity which enriches children’s lives “at the ultimate extent by connecting them with knowledge passed down through the ages”.

6 This first aim envisages the activity as an important introduction to the act of book learning itself. Importantly, the principle of learning in this context does not aim at the passing of examinations (a dominating and heavily criticized element in contemporary Taiwanese children’s lives) but something broader. This links to the second stated aim of the “Classics Reading” curriculum, encouraging “good action” (shanxing 善行, also commonly translated as “virtuous conduct”, “correct action”, “kind deed”, etc.). Good action is interpreted by the teachers in context as activity by the children contributing to the social good. Regular organized exemplifications of this are activities of filial piety (for instance, the physical massage of parents and grandparents), and activities focusing on the communal good of the school community (for instance, the cleaning and repair of the physical environment and furniture of the school, as seen in

Figure 1).

3.2. People and Practice

The school day usually runs from 8:30 a.m. until 5 p.m. and the children are divided into three groups delineated mainly by age—a lower group (xiaban) for children around 3 years old, a middle group (zhongban) for children around 4 years old, and a higher group (shangban) for children around 5 years old (immediately pre-primary school). The “Classics Reading” activity takes about 1 to 2 h and is usually performed in the late morning, although the teachers are extremely flexible and reactive to the students in terms of the length of teaching time, especially with the lower group.

The actual practice of “Classics Reading” for one to two hours per day is markedly different in each of the three groups, each of which also concentrates on different texts. The lower group read

Dizigui 弟子規 (

Rules for Younger Sons) and

Qianziwen 千字文 (

The Thousand Character Classic). The latter text, dating from at least the mid-first millennium AD, is a rhyming arrangement of a thousand characters in four character sets which is used to teach characters. The former is a Qing period short primer for young children, teaching them basic moral rules from a Neo-Confucian perspective—in this case, through listing moral rules and advice.

7The class reads 12 characters at a time. The 12 characters are set up on a white board in front of the class and the class communally reads through several times in a loud voice. Both texts have been designed to rhyme and chant well, and the school uses the intended musicality of the texts effectively to make the process fun and exciting for the children. After chanting the 12 character set several times, the teachers begin to remove certain characters from the 12, then ask the students communally and individually to pick out the right character to replace. A clear aim is to use this traditional technique to communally begin to teach Chinese character literacy. The instructors put much emphasis on making the activity enjoyable for the students, even including physical games in the process. For instance, after individually picking the correct replacement character or reciting the 12-character set, the student will get to go through a small fun obstacle course at the back of the class. In this way, the process is made very dynamic and at times physical for the 3- to 5-year-old students involved.

8 Chanting is the major element, and clearly the most enjoyable for the students. It is clear that nearly all students can chant most of the texts, especially if prompted now and again. However, the capacity to recognize characters shows much greater diversity between individuals.

The middle class read

Gujin beishufangfa 古今背書方法 (

Method for Reciting Texts from the Past and Present) and the

Xiaojing 孝經 (

Classic of Filial Piety). The

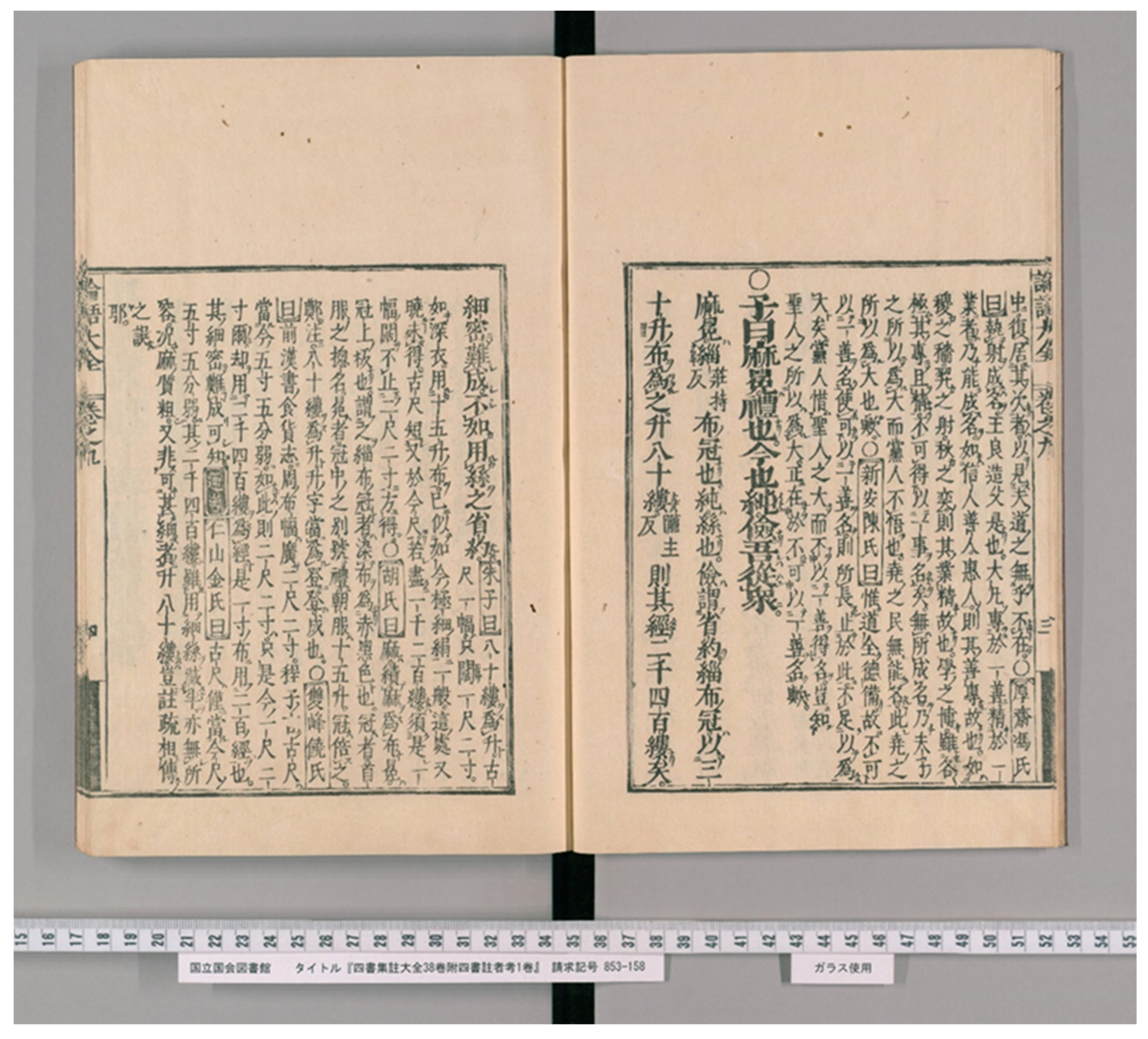

Gujin beishufangfa is a Qing period compilation of short excerpts from famous Confucian scholars, giving instruction on how one should recite (

beishu 背書—so recite, not read) texts. The excerpts are drawn from Neo-Confucian scholars from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing periods, with an emphasis on excerpts from the Song doyen of Neo-Confucianism, Zhu Xi (1130–1200 AD), and his adherents. Zhu Xi developed Neo-Confucianism under heavy Buddhist influence, emphasizing religious methods of self-cultivation as sitting at the heart of Confucian practice. Correspondingly, the contents of this compilation emphasize approaching the recitation of the text in terms of creating a certain mood, by placing the text carefully, facing it calmly, paying close attention, etc., as can be seen in

Figure 2.

9 It emphasizes mood and affect in the reading of the text, rather than meaning. It is clear from my observation of the recitations in Taipei, notably in contrast to the approach in Tokyo, how influential this Buddhist-inspired, traditional Neo-Confucian approach to textuality is in this example of early childhood practice. The

Xiaojing, or

Classic of Filial Piety, is one of the so-called 13 Classics. The text dates at least from the Han and is self-ascribed as a record of a conversation between Confucius and his disciple Zengzi, traditionally thought to have lived in the fifth century BCE. A relatively short text, it focuses on the import and meaning of filial piety, set in the context of the hierarchies of political and family relations of the time.

10The middle group is larger in number than the lower group, comprising 40 students with two teachers (as opposed to about 28 students with three teachers in the lower group). The core practice is also chanting, and sets of characters are shown on the board, but the visual aids are not used as much, the students instead encouraged to follow the chanting by moving their hand through their own copy of the book character by character. As with the lower group, students are asked individually to fill in the removed parts of the text. However, these are longer sections and have fewer visual aids, so the students are asked, both individually and as a group, to complete comparatively long sections of the text. Again, this is achieved through musical chanting.

In the higher class, with about 30 students and two very active teachers, the students read from their own books large sections of text. They read the Daxue 大學 (The Greater Learning) and Fumenping 普門品 (The Universal Gate). The Daxue is the first book of the Neo-Confucian Four Book canon. Edited by Zhu Xi in the Southern Song, this very short treatise was traditionally the first Confucian book read by young children across East Asia from around the Yuan dynasty onwards. The Fumenping, or Universal Gate, is the 25th chapter of the Buddhist Lotus Sutra relating to the Boddhisatva Guanyin 觀音 (Jp: Kannon).

By higher class stage, the students read several pages at a time, so many use the text as their main prompt (as seems to be the literacy pedagogy aim). The diversity in capacity to read at a higher level is very high. Some children appear to use the text and actually read, while others have their fingers nowhere near the right part of the text and are clearly just mumbling along. Possibly for this reason, instead of asking individuals to read, the class is broken into different teams (usually two or three) which chant at each other, chanting half a page before the next group takes up the other half. The parallels with music education are very clear. One notable example is that the teachers have to keep reminding the students not to speed up as they chant. I was reminded of choir practice or class singing at school when I was a child. It is clear that the children enjoy this activity very much. Again, the physical act of loud articulation and chanting is clearly physically stimulating for the students and allows them to release energy and enjoy themselves. The higher group class I observed lasted for nearly two hours, and at the end although some of the students seemed exhausted it was also clear that most of them felt exhilarated and had enjoyed themselves.

I had the opportunity to interview the higher-group students together with the teachers and principal immediately after the class. I asked the children simply how was their lesson and what they thought of it. The two main responses shouted from the floor by several children were either “hard” or “good”. With help from the teachers, I encouraged the children to answer individually about what they found “hard” and what they found “good”. Answers to what was “hard” included: “It’s hard when I cannot remember”; “the characters are hard”; “it’s difficult to read”; “it’s difficult to read so much”. The child who gave the last answer after thinking then added, “but it’s OK when Daddy helps”. The children who replied “good” gave as reasons: “you can read things you see outside or in the street” (to which several children nodded and loudly expressed agreement); “you learn to sing”; “learn characters”. The teachers, seemingly noticing, as I had, that all the answers related to language pedagogy rather than ethics then prompted the students to say something about the ethical or moral side of things. The response was initially a long silence. This silence was finally broken by one girl saying, in a very humorous tone, “I learnt that whatever mama says to do I should do”, after which all the children and teachers broke out laughing, which from her reaction was clearly the response to her joke the girl had been looking for. It was clear from observation, and particularly from the question session, that the children saw the “Classics Reading” sessions as a fun form of singing or literacy lesson. They are aware that they are learning characters and seem to see that as the main event.

It should be pointed out, however, that the Confucian elements of the curriculum related to “Classics Reading” are not limited to these actual reading sessions. As noted above, there are regular activities run by the school under the auspices of the Buddhist organization, notably the “Filial piety days”, where children are helped to perform activities for their parents such as massages or writing letters, which are supposed to enact the ethics articulated in the texts. Other Confucian activities include biannual school trips to the Confucian Temple in central Taipei. Intriguingly, these trips to the Confucian Temple, which include communal worship (praying) at the temple by the Buddhist school children, are not in any way coordinated with the Confucian organization running the temple. The temple is a public installation, so the school simply turns up and uses it. The way they use it also conforms to the manner of their reading activities. At the temple, as well as lining up and bowing, which obviously takes only a moment, the children are asked to sing songs and move around. The teacher remarked that the children like it because it is an open space where they can make noise and move. Again, here we can see the packaging of “Confucian” activities in ways which allow children to do child-like activities, employing modern pedagogical practice to pad out the Confucian activity in what appears to me to be a very effective manner. This is yet another example of the admirable pedagogical skills and personal flexibility of the teachers at this school.

11Teachers were very aware of the importance of repetition and musicality, and intriguingly they also discussed this in relation to the sociality of the introduction of “Classics Reading” in their curriculum. In explaining why they introduced it, the principal of the school talked about the need to offer competing cultural forms to children in a manner they could absorb. She used the example of TV commercials, a constant on Taiwanese children’s television, and including advertisements for unhealthy foodstuffs. She pointed out that these TV commercials use repetition, music, and movement because they know that repetition in particular works on children. She asked, “should we leave the children to simply absorb TV commercials of how they should consume more, or should we offer something else?” In this sense, the practice can be seen as a reaction against contemporary consumerism, not only in its attempt to counter it, but also in its adoption of practices which, despite being “traditional” pedagogical techniques, are being deployed to compete against commercial culture and materialism using similar methods on similar grounds. In other words, the influence of “traditional culture” in the pedagogy is overlaid with, or plaited into, the influence of mainstream society (capitalist modernity) and an attempt to resist its deleterious influences.

This is the same logic which explains the big question of why a Buddhist school uses Confucian classics and Confucian pedagogy instead of their own texts. The principal explained to me that “Master Richang” had suggested that, given the current state of human society, the Confucian content was more appropriate and effective—a classic “expedient means” argument. This again relates to the understanding of the teachers (also as practitioners) that the “Classics Reading” activity, as a religious and educational activity, is one which deliberately interacts with a particular moment in the development of human society.