On the Differences between Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings in Their Portrayal of the Queen Mother of the West and Their Religious Significance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literary and Visual Representations of Queen Mother

3. Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings That Feature the Queen Mother

3.1. Han Rhapsodies That Feature the Queen Mother

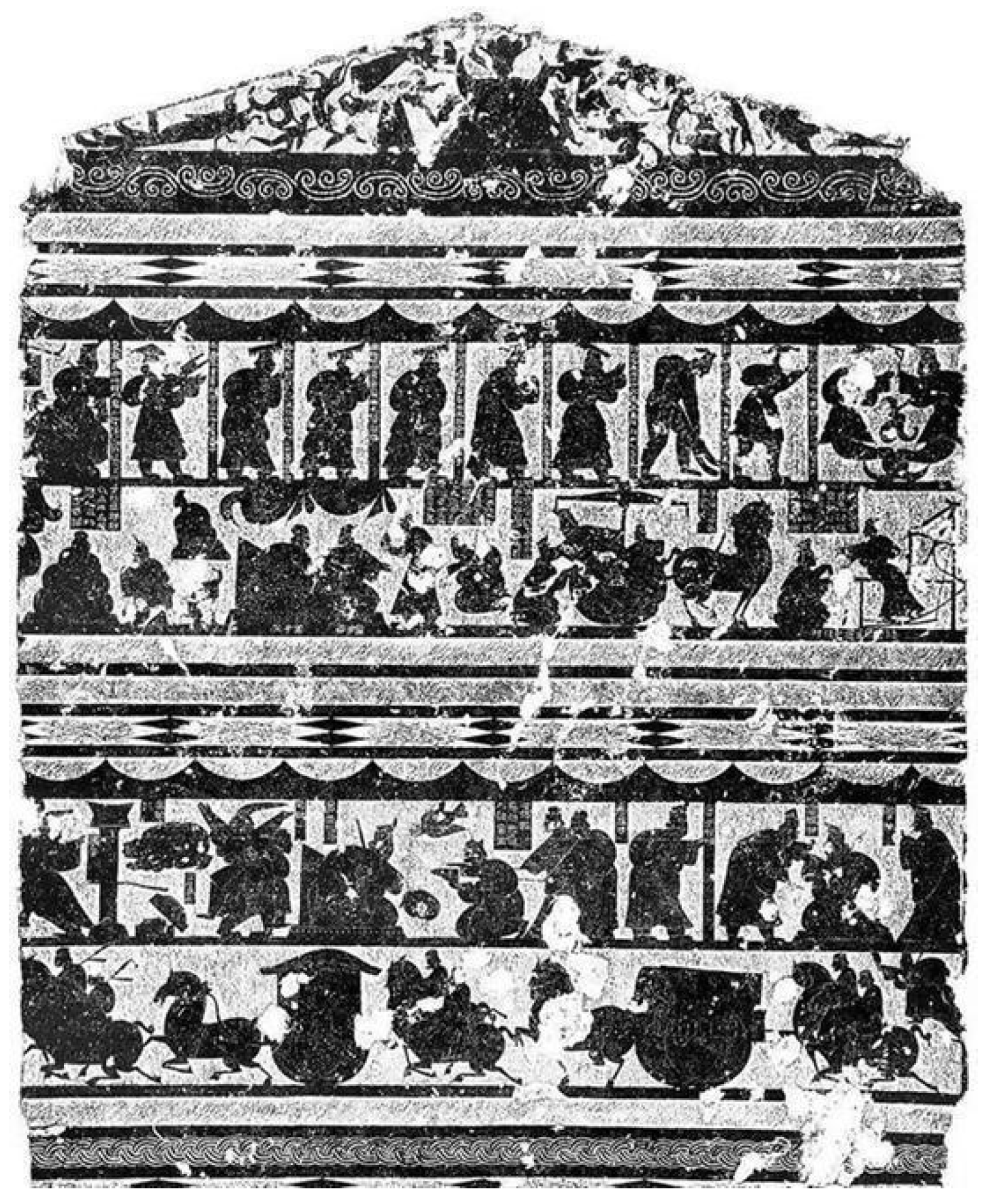

3.2. The Image of the Queen Mother in Han Paintings

4. Class Discrepancy in Works That Feature the Queen Mother

4.1. The Class Difference of the Artist Groups

4.1.1. The Writers of Han Grand Rhapsody

The ministers whose duties relied on language skills, such as Sima Xiangru, Yuqiu Shouwang 虞丘壽王, Dongfang Shuo 東方朔, Mei Gao 枚臯, Wang Bao 王褒, and Liu Xiang 劉向, spent entire days composing articles and often offered them to the emperor. The officials who held important positions in the imperial court, such as Ni Kuan 倪寬 as yushi dafu 禦史大夫 (Censor-in-chief), Kong Zang 孔臧 as taichang 太常 (Minister of Ceremonies), Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒 as taizhong dafu 太中大夫 (Palace Counsellor), Liu De 劉德 as zongzheng 宗正 (Minister of the Imperial Clan), and Xiao Wangzhi 蕭望之 as the taizi taifu 太子太傅 (the Grand Mentor), and so on, all took time to write fu.

4.1.2. The Artists of Han Stone Reliefs

4.1.3. Class Analysis of the Artist Groups

4.2. The Social Classes of the Patrons

4.2.1. Patrons of Han Dafu

When the Han dynasty quelled the Rebellion of the Seven States, Mei Cheng gained popularity for his famous fu, the “Seven Stimuli” (Qifa 七發), written during this time. Emperor Jing 景帝 (r. 157 BC–141 BC) soon appointed Cheng as the Chief Commandant (duwei 都尉) of Hongnong County. Cheng had long been a distinguished guest of the dynasty. He frequently traveled with young talents of that time; getting what he wanted, doing what he liked, he was not particularly fond of being a government official. Eventually, Cheng resigned from his post on the excuse of illness. Cheng then traveled to Liang (Han’s vassal state). Liang’s resident intellectuals were good at fu and writing and Cheng excelled amongst them. After the death of King Xiao 孝王 (r. 168 BC–144 BC), Cheng traveled back to Huaiyin 淮陰. The newly enthroned Emperor Wu 武帝 (r. 141 BC–87 BC) was an admirer of Cheng since he was a prince. By this time Cheng had reached old age. Emperor Wu invited Cheng to serve the court, sending him a special carriage with tires covered by palm leaves, which stabilized the carriage better than the typical ones of that time. Cheng died on the way.(Hanshu, 50.2365)

When Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty felt emotional, he often let Mei Gao write fu. Mei Gao wrote very quickly; he finished the works almost as soon as he received the imperial orders. Therefore, he was very prolific.(Hanshu, 20.2367)

It happened that Emperor Jing was not fond of literature. When King Xiao of Liang came to visit the court, scholars who were good at lobbying also came along, including Zou Yang 鄒陽 from Qi State, Mei Cheng 枚乘 from Huaiyin, and Zhuang Ji 莊忌 from Wu. Sima Xiangru took to liking them instantly and soon resigned from his position with an excuse of illness, and then he lived in Liang state as a sojourner. King Xiao of Liang asked Sima Xiangru to reside with the lobbyists, so Xiangru was able to stay with them for several years. He thus composed “Zixu fu” 子虚賦 (Rhapsody on Sir Vacuous).(Shiji, 117.2999)

When Sima Xiangru wrote “Shanglin fu” 上林賦 (Rhapsody on the Imperial Park) and “Zixu fu”, his heart was relaxed and unconstrained, no longer connected with the outside things. He used all things between heaven as the material of his poetry; his spirit traveled between ancient and modern times. He would appear listless and dreary at one point, but uplifted at another and continued to compose fu. A couple of hundred days later, the fu was completed.

Yang Xiong also said that Zhao Zhaoyi 趙昭儀, a concubine of Emperor Cheng 成帝 (r. 33 BC–7 BC) of the Han dynasty, was favored by the emperor. Every time he went up to the Ganquan Palace, Emperor Cheng would order Yang Xiong to compose a fu. This exhausted Yang Xiong. He had to rack his brains every time to complete the fu. Finally, he was feeling tired and had to rest in bed, during which time he dreamed that his five internal organs were exposed on the ground, and he gathered them back into his body with his hands. When he woke up, he was inflicted with asthma and often could not breathe properly. He fell ill for a year afterward. From this, we can know that it overtaxes one’s nerves and spirit to make fu.

4.2.2. Patrons of the Han Stone Reliefs

The owner of the highest status among the Han stone tombs was a vassal king, and up till now among all excavated Han tombs there is only one such instance, which is the tomb of Liu Chong 劉崇 (r. AD 120–124), King Qing of Chen of the Eastern Han dynasty. Liu Chong’s tomb is of a very large scale, but there are not many stone reliefs inside the tomb, with most of them only being used at the entrance gate to the tomb. The original location of another stone relief fragment unearthed in the tomb cannot be determined. It can be seen that the stone reliefs were not the foremost body of the decoration of tombs of the princes and kings of the Han dynasty. The use of stone reliefs as tread stones for the toilet in the murals for the stone cliff-side tomb in Shiyuan, Yongcheng, Henan, may also be proof.

Up till now, among the unearthed 102 tombs of Han vassal kings, more than 1800 pieces of jade artifacts have been found. …Among the unearthed jade artifacts, more than 1400 pieces have been unearthed from the tombs of high-ranking vassal kings (houwang 侯王), accounting for 79% of the total. Another 380 pieces of jade were unearthed from the tombs of lower-ranking adjunct marquesses (liehou 列侯), accounting for 21% of the total.

The top arch is supported with two kinds of fan-shaped bricks. The four walls have two layers, inner and outer, and the outer layer is covered by ‘one and a half bricks’ (two horizontal bricks and one vertical brick in each layer). The walls are coated with 0.5 cm thick white plaster, and on the walls, images of carriage processions are drawn. The inner layer clings to the mural with strips of bricks. The top-down single-layer bricks are staggered and flat, stopping at a height of 2.2 m, enclosing the mural completely. Hence, the inner walls were undoubtedly added later. The reason behind it may have been that the content of the murals on the outer layer did not match the actual identity and official position of the tomb owner, so it was sealed.

4.2.3. Class Analysis of the Patrons

4.3. The Significance of the Class Analysis of Han Rhapsodies and Han Pictorial Stones

4.4. Special Comparison between Han Fu and Other Literary Works

5. The Differences in Functions of the Queen Mother in Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings

5.1. The Queen Mother in the World of Longevity and Immortality in Han Grand Rhaposodies

5.1.1. Passages That Describe the Queen Mother’s Living Environment

The immortals Chisongzi 赤松子 and Wang Ziqiao 王子喬 sat in the east wing while the Queen Mother sat in the west wing. They asked Han Zhong 韓眾 and Qi Bo 岐伯 to tell and collate the books read by deities. They hoped to be able to make friends with them and be enlightened therein, so as to travel far away from the mortal plane and roam afar.

[I] met the Queen Mother at Yintai 銀臺 (the moon) and ate the celestial food yuzhi 玉芝 (jade mushroom). She smiled and was delighted, complaining that I was a bit too late. Having brought the fairy maiden (attending the immortals) from Taihua Mountain along with her, she also summoned the Luoshui goddess Mi fei 宓妃 (Concubine Mi). They were both so beautiful and captivating, with their charming eyes and fine and delicate eyebrows.

5.1.2. Materials That Comment on the Queen Mother

Having wandered and soared in the Yinshan Mountains, I only got to see the Queen Mother with my own eyes today.… Gray-haired with a sheng 勝 headdress, the Queen Mother lived in a cave. Fortunately, there was a three-legged bird as her messenger. If to become immortal, one had to live forever like her, it is not joyful at all.

[When Emperor Cheng 成帝 (r. 33 BC–7 BC) of Han] thought of the Queen Mother, he happily went to celebrate her birthday and avoided the fairy maidens, Jade Lady and Concubine Mi. They thus had no chance to look at him with their bright eyes, or show him their slender eyebrows. Emperor Cheng mastered the essence of the subtle and strong Way and received the counsel of the gods.

5.1.3. Discussion of the Function of the Queen Mother in Han Grand Rhapsodies

5.2. The Queen Mother Who Combines the Immortal World with the Mortal World in Han Stone Reliefs

5.2.1. The Regional Distribution of the Images of the Queen Mother

Based on existing archaeological results about images of the Queen Mother, the Han Dynasty stone reliefs are divided into (1) Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan, and Anhui Districts; (2) central and southern Henan Districts; (3) northern Shaanxi District; and (4) Sichuan District. First, in the Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan, and Anhui Districts, the images of the Queen Mother were mostly found in Shandong Province, but some were also found in Jiangsu Province. Most images of the Queen Mother are frontal, with her hands arched together, sitting on her knees. According to the presence or absence of a base, they can be divided into two types: BI [frontal image on a pedestal] and BII [frontal image without a supporting pedestal]. Second, in the Central and Southern Henan Districts, the characteristics of the Queen Mother images can be summarized as: a flowery jade hairdress (sheng 勝) worn on the head, holding objects in her hands, sitting on the mountains or a pedestal. Those Queen Mother images fall into two groups: AI [profile on a pedestal] and AII [profile without a supporting pedestal], considering her different sitting postures: one being a three-quarter profile, and the other a regular profile. Third, in the northern Shaanxi District, the basic feature of the Queen Mother images is that she sits on her knees with sheng hairdress worn on her head facing the front. These images can also be divided into two types, BI and BII, according to whether they have bases or pedestals. Fourth, in the Sichuan District, the images of the Queen Mother unearthed have obvious local characteristics: the dragon-tiger throne seen in this area’s images are rarely seen in other districts.

5.2.2. The Distribution of Subject Types of the Images of the Queen Mother

Daily life: including chariot procession, feasting, lecturing, field hunting, pavilion construction, arsenal(s), Liubo 六博 [ancient Chinese board game], cockfighting, and hunting with hounds. These are addressed to a variety of local magistrates, and servants. (2) Ancient myths: including Fuxi and Nüwa from the Chinese creation mythology, the Queen Mother, the King Father, Hou Yi 後羿 Shooting Ten Suns, Lady Chang’e’s 嫦娥 Flying to the Moon, etc. (3) Historical tales: including Killing Three Generals with Two Peaches, Hongmen Feast (鴻門宴 the banquet where Liu Bang 劉邦 escaped attempted murder by his rival Xiang Yu 項羽), Fan Sui 範睢 receiving the robe, Nie Zheng 聶政 taking his own life, Qin Shi Huang 秦始皇 (First Emperor of Qin) dispatching a thousand men to search for the Nine Tripod Cauldrons lost in the Si River. (4) Astronomical images: the sun and the moon, the sun and the moon harmoniously hanging together in the sky, sun and moon glowing together, constellations such as the Black Dragon 蒼龍, the White Tiger 白虎, Beidou 北斗 (the Big Dipper), Gouchen 勾陳 (the North Star), and so on. (5) yuewu baixi樂舞百戲 (“hundred operas,” or ancient acrobatics, music and dance performances in general): various dances including drum and dance, changxiuwu 長袖舞 (long sleeve dance), qipanwu 七盤舞 (seven-tray dance), etc.; chongxia 沖狹 (ancient aerobatics, jumping through a grass ring studded with knives), feijian tiaowan 飛劍跳丸 (flying sword and juggling), nonghu 弄壺 (balancing a pot on an arm), tuhuo 吐火 (spitting fire), juedixi 角抵戲 (sports and aerobatics such as wrestling, ancient pod lifting, illusion magic, etc.).

5.2.3. A Discussion of the Functions of the Queen Mother in Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

Sitting on the summit of Kunlun or a dragon-tiger throne, she is portrayed frontally as a solemn image of majesty, ignoring the surrounding crowds and staring at the viewer beyond the picture. The viewer’s sight is guided to her image in the center, to be confronted directly by the goddess.

5.3. Hierarchical Order and Functional Role as Seen in the Hierarchy of Han Pantheon

There also exists the idea about the class of deities. In the Huainanzi, we find the two deities acting as representatives of the emperor were on duty throughout the night by walking arm in arm. Many other passages also show that both deities and ghosts are subordinate to the hierarchical order under the emperor. A second century author even differentiated a series of deities corresponding to the hierarchy of the human world. Thus, some deities were prescribed to be worshiped by emperors or nobles, others were said to be in the charge of wizards, and still others were the objects to be prayed, aspired and awe-stricken of lesser mortals.

We cannot say that all the religious objects or activities in the official religious sacrifice system are not referred to as the folk beliefs. The religion of the Han Dynasty may be characterized by the entanglement between the official religious system and folk beliefs. This can be regarded as a continuation of the development of ancient Chinese religious beliefs since the pre-Qin era, that is, the cosmology of basically sharing the same religions between the upper and lower societies without any fundamental conflicts, and there are only some differences in application.

6. Special Significance of the Sage-King Images in the Wu Liang Shrine

6.1. Description of How the Two Worlds Overlap

The image elucidates this theme in two ways. First of all, the Queen Mother of the West usually wears a unique crown as a necessary attribute. This crown can be interpreted as a symbol of her power to weave the web of the universe, symbolizing the power of perpetuating the human life. Second, the theme of Yin and Yang is often presented in other ways: either as a description or as a symbol.

6.2. The Mutual Evidence in Official Historical Records

In the first month of the fourth year of Jianping (3 BC), during the reign of the Emperor Ai of the Han dynasty, people fled in panic, holding a stick of dried-up wood or hemp stalk in their hands, and passing it to one another, which is called “passing edict sticks” (xing zhaochou 行詔籌). Thousands of people ran across each other along the road. Some walked barefoot with scattered hair, some destroyed the official pass at night, some went over the wall, and some took carriages or rode on horseback, changing horses at the relay station for fresh ones to continue their journey. It was only after passing through twenty-six vassal states did they arrive at the capital. In the summer of that year, people in the capital gathered in the alleys, streets and squares, and they set up gaming tools and sang and danced to worship the Queen Mother of the West. Then there came a word, saying: “The Queen Mother of the West tells the people that those who carry this amulet shall not die. Those who don’t believe what I have said, just look under your door hinge and you will find white hair.”. The incident did not stop until autumn.(Hanshu, 27.1476)

The Grand Empress Dowager (Empress Xiaoyuan) was with the blessing of the holy land of Shalu 沙鹿 in Yuancheng元城, as well as the auspicious sign from the deity who represented the yin essence and fertility. Consort of Emperor Han Yuan, she gave birth to Emperor Han Cheng. Thus, she was able to show the harmony of the Han family, and also received the blessings and auspicious signs from the Queen Mother, to protect the emperor’s clan, stabilize the long-standing and influential families, and continue their lineage to inherit the feats of the Han family to dominate the world.(Hanshu, 84:54:3432)

During the reign of Emperor Ai of the Han dynasty, rumors about the miracle of Queen Mother’s book of immortality were prevalent among the people. Therefore, people worshiped Xiwangmu and prayed to her for a peaceful year. This is a sign that the Grand Empress Dowager will become the mother of all generations. How dare I disobey the destiny of heaven! Therefore, I deliberately chose an auspicious day to personally lead the royal family, ministers, and celebrated scholars to present the seal of the empress dowager respectfully to show to the world that I have complied with the will of heaven.(Hanshu, 98:68:4033)

6.3. Properties of Commoners’ Class Characteristic of Han Tombs with Stone Reliefs

Wu Ban 武斑 died in 145 at the age of 25. Before his death, he served as a chief clerk to a protector-general of the Dunhuang District.

Wu Ban’s father, Wu Kaiming 武開明, died in 148. He once worked in the imperial house as a royal coachman.

In 151, Wu Kaiming’s older brother, Wu Liang 武梁, died at age 74. He was a “virtuous man” who became a recluse devoted to learning.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Composition | Name of the Remain | Location | Period | Source (Archaeological Report) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition solely with the Queen Mother | Sarcophagus adorned with pictorial stone carvings from a brick tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty (Sarcophagus No. 1) 四川郫縣東漢磚墓的石棺畫像 (一號石棺) | Pixian County, Sichuan 四川郫縣 | Eastern Han | (Liang 1979) |

| Sarcophagus adorned with pictorial stone carvings from a brick tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty (Sarcophagus No. 2) 四川郫縣東漢磚墓的石棺畫像 (二號石棺) | Pixian County, Sichuan 四川郫縣 | Eastern Han | (Liang 1979) | |

| Sarcophagus adorned with pictorial stone carvings from a brick tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty (Sarcophagus No. 4) 四川郫縣東漢磚墓的石棺畫像 (四號石棺) | Pixian County, Sichuan 四川郫縣 | Eastern Han | (Liang 1979) | |

| Sarcophagus in cliff-side tomb, Shuanghe Township, Pengshan County 彭山縣雙河鄉崖墓石棺 | Pengshan County, Sichuan 四川彭山 | Han Dynasty | (Gao 1985) | |

| Leshan Mahao Eastern Han cliff–side tomb 樂山麻浩東漢崖墓 | Leshan, Sichuan 四川樂山 | Eastern Han | (Tang 1987) | |

| Fushun Sarcophagus 富順石棺 | Fushun County, Sichuan 四川富順 | Eastern Han | (Gao and Gao 1988) | |

| Hejiang Sarcophagus 合江石棺 | Hejiang County, Sichuan 四川合江 | Eastern Han | (Gao and Gao 1988) | |

| No. 12 Luzhou Sarcophagus 瀘州12號石棺 | Luzhou, Sichuan 四川瀘州 | Han Dynasty | (Xie 1991) | |

| No. 13 Luzhou Sarcophagus 瀘州13號石棺 | Luzhou, Sichuan 四川瀘州 | Han Dynasty | (Xie 1991) | |

| Eastern Han cliff–side tombs, Tuoguzui, Leshan City, Sichuan 四川樂山市沱溝嘴東漢崖墓 | Leshan, Sichuan 四川樂山 | Eastern Han | (Hu and Yang 1993) | |

| Hejiang Zhangjiagou No. 2 cliff–side tomb sarcophagus adorned with pictorial stone carvings (Hejiang No. 4 Coffin) 合江張家溝二號崖墓畫像石棺 (合江四號棺) | Neijiang, Sichuan 四川內江 | Han Dynasty | (Wang and Li 1995) | |

| Changshunpo No. 2 Sarcophagus adorned with pictorial stone carvings, Nanxi District 南溪縣長順坡二號畫像石棺 | Nanxi, Sichuan 四川南溪 | Period of sarcophagus known; patterned bricks date back to Han Dynasty | (Yan 1996) | |

| Tomb No. 1, Tiantai Mountain, Qijiang cliff–side tombs, Santai, Sichuan 四川三臺郪江崖墓群天臺山l號墓 | Santai, Sichuan 四川三臺 | Han Dynasty | (Zhong 2002) | |

| M3 sarcophagus adorned with pictorial stone carvings in Huzhu Village, Sanhe Town, Xindu District 新都區三河鎮互助村M3畫像石棺 | Chengdu, Sichuan 四川成都 | Eastern Han | (Chen et al. 2002) | |

| Cliff-side tomb HM3, Huzhu Village, Sanhe Town, Xindu District, Chengdu 成都市新都區三河鎮互助村崖墓HM3 | Chengdu, Sichuan 四川成都 | Eastern Han | (Chen et al. 2007) | |

| Niushihan cliff-side tomb, Luxian County, Sichuan 四川瀘縣牛石函崖墓 | Lu County, Sichuan 四川瀘縣 | Late Eastern Han | (Luzhou Museum and Chengdu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 2009) | |

| M6, Area A, Shiziwan cliff–side tombs, Leshan City, Sichuan 四川樂山市柿子灣崖墓A區M6 | Leshan, Sichuan 四川樂山 | Late Eastern Han to Shu Han | (Chen et al. 2014) | |

| Eastern Han Tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Yanjiacha, Suide County, Shaanxi 陝西綏德縣延家岔東漢畫像石墓 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Eastern Han | (Dai and Li 1983) | |

| No. 2 Tomb with pictorial stone carvings, Yanjiacha, Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德延家岔二號畫像石墓 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Eastern Han | (Li 1990) | |

| Tomb with pictorial stone carvings with Portraits in Wuyequan Village, Suide 綏德嗚咽泉村畫像石墓 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Around the Reign of Emperor He (AD 88–106) and Emperor Shun (AD 125–44) of the Eastern Han Dynasty | (Wu 1992) | |

| Stone tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Sishilipu, Suide County, Shaanxi 陝西綏德縣四十裏鋪畫像石墓 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Eastern Han | (Cultural Management Committee of Yulin Prefecture and Museum of Suide County 2002) | |

| M6 Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings, in Huangjiata, Suide County, Shaanxi 陝西綏德縣黃家塔漢代畫像石墓M6 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Han Dynasty | (Li 2004) | |

| M9 Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings, in Huangjiata, Suide County, Shaanxi 陝西綏德縣黃家塔漢代畫像石墓M9 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Han Dynasty | (Li 2004) | |

| M3 Eastern Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Dabaodang, Shenmu, Shaanxi 陝西神木大保當東漢M3畫像石墓 | Shenmu, Shaanxi 陝西神木 | Eastern Han | (Xiao et al. 2011) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Shenliuzhuang, Juxian County, Shandong 山東莒縣沈劉莊漢畫像石墓 | Juxian County, Shandong 山東莒縣 | Late Eastern Han | (Su and Zhang 1988) | |

| M2 Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings, Shantou Village, Tengzhou City, Shandong 山東滕州市山頭村M2號漢代畫像石墓 | Tengzhou, Shandong 山東滕州 | Early Western Han | (Tengzhou Han Stone Relief Museum 2012) | |

| Brick tombs with pictorial stone carvings at Dazhulin, Taojiazhen, Jiulongpo, Chongqing 重慶九龍坡陶家大竹林畫像磚墓 | Jiulongpo, Chongqing 重慶九龍坡 | Eastern Han | (Lin and Liu 2007) | |

| M1 Eastern Han cliff–side tombs in Bishan County, Chongqing 重慶璧山縣棺山坡東漢崖墓群(M1) | Bishan, Chongqing 重慶璧山 | Late Eastern Han | (Fan et al. 2014) | |

| Tomb No. 3 in Bainijing, Zhaotong 昭通白泥井三號墓 | Zhaotong, Yunnan 雲南昭通 | Eastern Han | (Sun 1955) | |

| Ancient tombs in Zhaotong, Yunnan 雲南昭通古墓葬 | Zhaotong, Yunnan 雲南昭通 | Eastern Han | (Yunnan Provincial Cultural Relics Team 1960) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. 1 (Grave of Nine Women) in Chulan District, Suzhou, Anhui 安徽宿縣褚蘭漢畫像石一號墓(九女墳墓) | Suzhou, Anhui 安徽宿州 | Eastern Han | (Wang 1993) | |

| Composition with both the Queen Mother and King Father | Eastern Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. 14 in Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石東漢畫像石墓(14號) | Lishi, Shanxi province 山西離石 | Eastern Han | (Shang and Liu 1996) |

| Eastern Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. 19 in Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石東漢畫像石墓(19號) | Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石 | Eastern Han | (Shang and Liu 1996) | |

| Eastern Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. 44 in Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石東漢畫像石墓(44號) | Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石 | Eastern Han | (Shang and Liu 1996) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Shipancun, Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石石盤漢畫像石墓 | Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石 | Han Dynasty | (Wang 2000) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Shipancun, Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石石盤漢畫像石墓 | Lishi, Shanxi province 山西離石 | Eastern Han | (Wang 2005) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Mamaozhuang, Lishi 離石馬茂莊漢畫像石墓 | Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石 | Han Dynasty | (Wang and Wang 2006) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Maomaozhuang, Lishi, Shanxi, fourth year of the Jianning reign period 山西離石馬茂莊建寧四年漢畫像石墓 | Lishi, Shanxi 山西離石 | AD 171 | (Wang 2009) | |

| Han pictorial stones painted with colors in Liulin, Shanxi 山西柳林漢彩繪畫像石 | Liulin, Shanxi 山西柳林 | Han Dynasty | (Gao and Kong 2014) | |

| Han pictorial stones painted with colors in Xipo, Zhongyang, Shanxi 山西中陽西坡漢墓彩繪畫像石 | Zhongyang, Shanxi 山西中陽 | Han Dynasty | (Qiao and Kong 2016) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. M8 in Huangjiata, Suide County, Shaanxi 陝西綏德縣黃家塔漢代畫像石墓M8 | Suide, Shaanxi 陝西綏德 | Han Dynasty | (Li 2004) | |

| Tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. 2 in Guanzhuang, Mizhi County, Shaanxi 陝西米脂官莊二號畫像石墓 | Mizhi, Shaanxi 陝西米脂 | Mid-Eastern Han | (Ji 2011) | |

| Wu Liang Shrine 武梁祠 | Jiaxiang, Shandong 山東嘉祥 | Late Eastern Han | (Jiang and Wu 1995) | |

| Stone tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Wubaizhuang, Linyi, Shandong 山東臨沂吳白莊漢畫像石墓 | Linyi, Shandong 山東臨沂 | Late Eastern Han | (Guan et al. 1999) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. M1, Wohushan, Zoucheng City, Shandong 山東鄒城臥虎山M1號漢畫像石墓 | Zoucheng, Shandong 山東鄒城 | Late Western Han or Early Eastern Han | (Hu 1999) | |

| Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings No. M2, Wohushan, Zoucheng City, Shandong 山東鄒城臥虎山M2號漢畫像石墓 | Zoucheng, Shandong 山東鄒城 | Late Western Han or Early Eastern Han | (Hu 1999) | |

| Tomb with pictorial stone carvings from the Three Kingdoms Period in Tengzhou City, Shandong Province 山東滕州三國時期畫像石墓 | Tengzhou, Shandong 山東滕州 | Cao Wei or Western Jin Dynasty | (Tengzhou Museum 2002) | |

| Luzhou No. 1 Sarcophagus 瀘州一號石棺 | Luzhou, Sichuan 四川瀘州 | Eastern Han | (Gao and Gao 1988) | |

| M1 Han Tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Shengcun, Xiaoxian County, Anhui Province 安徽蕭縣聖村M1漢畫像石墓 | Suzhou, Anhui 安徽宿州 | Eastern Han | (Zhou 2010) | |

| Han Tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Wayao, Xinyi, Jiangsu 江蘇新沂瓦窯漢畫像石墓 | Xinyi, Jiangsu 江蘇新沂 | Late Eastern Han | (Wang et al. 1985) | |

| Composition solely with the King Father | Han tomb with pictorial stone carvings in Liujiatuan, Feixian County, Shandong Province 山東費縣劉家疃漢畫像石墓 | Feixian, Shandong 山東費縣 | Late Eastern Han | (Yu et al. 2018) |

| Han tombs in Changli Reservoir 昌梨水庫漢墓群 | Donghai, Jiangsu 江蘇東海 | End of Eastern Han | (Li 1957) |

| 1 | See the Appendix A (Table A1) for more details about the Han stone carving remains that feature the Queen Mother. |

References

Primary Sources

Ban, Gu 班固 (AD 32–92). 1962. Hanshu 漢書 (Book of the Han). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.Fan, Ye 範曄 (AD 398–445). 1965. Hou Hanshu 後漢書 (Book of the Later Han). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.Ge, Hong 葛洪. 1985. Xijing Zaji 西京雜記 (Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.Sima, Qian 司馬遷 (ca. 146–ca. 90 BC). 1958. Shiji 史記 (Records of the Grand Historian). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.Secondary Sources

- Cahill, Suzanne. 1993. Transcendence and Divine Passion: The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Weidong 陳衛東, Rui Liu 劉睿, Fei Li 李飛, Xiaonan Zhou 周曉楠, Jian Zhao 趙建, Xiaodong Jia 賈曉東, Qi Jia 賈琪, Xueyi Peng 彭學義, Tao Wang 汪濤, and Enze Mao 毛恩澤. 2014. Sichuan Leshan shi Shiziwan yamu A qu M6 diaocha jianbao 四川樂山市柿子灣崖墓A區M6調查簡報 (Investigation Briefing on M6, Area A, Shiziwan Cliff–side Tombs, Leshan City, Sichuan). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 4: 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yunhong 陳雲洪, Yue Li 李躍, Zhongxiong Wang 王仲雄, Ping Li 李平, Bing Yang 楊兵, Guosong Dang 黨國松, Bo Wang 王波, Lixin Chen 陳立新, Yinke Lu 盧引科, and Jiamei Cao 曹佳梅. 2002. 成都市新都區互助村、涼水村崖墓發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the Excavation of Cliff–side Tombs in Huzhu Village and Liangshui Village, Xindu District, Chengdu). Chengdu Kaogu Faxian 成都考古發現 (Archaeological Discoveries of Chengdu) 00: 4316–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yunhong 陳雲洪, Yuxin Zhang 張俞新, and Bo Wang 王波. 2007. 成都市新都區東漢崖墓的發掘 (Excavation of Eastern Han Cliff-side Tombs in Xindu District, Chengdu). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 9: 300–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Xinde 叢新德. 2008. Xiwangmu tuxiang de leixingxue yanjiu 西王母圖像的類型學研究 (Typological Research on the Image of the Queen of the West). In Xiwangmu Wenhua Yanjiu Jicheng: Lunwen Juan 西王母文化研究集成·論文卷 (Collected Research on the Culture of the Queen Mother of the West, Collected Essays). Guilin: Guangxi Shifan Daxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Management Committee of Yulin Prefecture and Museum of Suide County. 2002. Shaanxi Suide xian Sishilipu huaxiangshi mu diaocha jianbao 陝西綏德縣四十里鋪畫像石墓調查簡報 (Investigation Briefing on Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Sishilipu, Suide County, Shaanxi). Kaogu Yu Wenwu 考古與文物 (Archaeology and Cultural Relics) 3: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Yingxin 戴應新, and Zhongxuan Li 李仲煊. 1983. Shaanxi Suide xian Yanjiacha Dong Han huaxiang shimu 陝西綏德縣延家岔東漢畫像石墓 (Eastern Han Dynasty Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Yanjiacha, Suide County, Shaanxi). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 3: 233–37. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Wenping 杜文平. 2014. Xiwangmu Gushi de Wenben Yanbian Ji Wenhua Neihan 西王母故事的文本演變及文化內涵 (The Evolution of the Xiwangmu Narrative and Its Cultural Connotation). Ph.D. thesis, Nankai University, Tianjin, China. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Peng 范鵬, Dadi Li 李大地, and Houxi Zou 鄒後曦. 2014. Chongqing Bishan xian Guanshanpo Dong Han yamu qun 重慶璧山縣棺山坡東漢崖墓群 (Eastern Han Cliff-side Tombs in Bishan County, Chongqing). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 9: 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Zhengang 費振剛, Shuangbao Hu 胡雙寶, and Minghua Zong 宗明華, eds. 1993. Quan Hanfu 全漢賦 (Complete Han Rhapsodies). Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, Chris J. 1988. The Hindu Pantheon and the Legitimation of Hierarchy. Man 23: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Wen 高文. 1985. Xuanli duocai de huaxiang shi: Sichuan jiefang hou chutu de wuge Han dai shi guanguo 絢麗多彩的畫像石—四川解放後出土的五個漢代石棺槨 (Brilliant and Colorful Stone Portraits—Five Han Dynasty Sarcophagus Coffins Unearthed after the Liberation of Sichuan). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 1: 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Wen 高文, and Chengying Gao 高成英. 1988. Sichuan chutu de shiyi ju Handai huaxiang shiguan tushi 四川出土的十一具漢代畫像石棺圖釋 (Eleven Han Dynasty Sarcophagi with Pictorial Carvings Unearthed in Sichuan). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 3: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Jiping 高繼平, and Lingzhong Kong 孔令忠. 2014. Shanxi Liulin faxian de Han caihui huaxiang shi 山西柳林發現的漢彩繪畫像石 (Han Dynasty Pictorial Stone Carvings Painted with Colors Found in Liulin, Shanxi). Wenwu Shijie 文物世界 (World of Cultural Relics) 1: 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Enjie 管恩潔, Qiming Huo 霍啟明, and Shijuan Yin 尹世娟. 1999. Shandong Linyi Wubai zhuang Han huaxiang shimu 山東臨沂吳白莊漢畫像石墓 (Han Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Wubaizhuang, Linyi, Shandong). Dongnan Wenhua 東南文化 (Southeasteastern Culture) 6: 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Xinli 胡新立. 1999. Shandong Zoucheng shi Wohu shan Han huaxiang shimu 山東鄒城市臥虎山漢畫像石墓 (Han Dynasty Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings at Wohu Mountain, Zoucheng City, Shandong). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 6: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Xueyuan 胡學元, and Yi Yang 楊翼. 1993. Sichuan Leshan shi Tuogouzui Dong Han yamu qingli jianbao 四川樂山市沱溝嘴東漢崖墓清理簡報 (Brief Report on Cleaning up the Cliff-side Tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty at Tuoguzui, Leshan City, Sichuan). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 1: 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Minglan 黃明蘭, and Yinqiang Guo 郭引強. 1996. Luoyang Han Mu Bihua 洛陽漢墓壁畫 (Han Dynasty Tomb Murals Near Luoyang). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Xiangyue 姬翔月. 2011. Shaanxi Mizhi Guanzhuang erhao huaxiang shimu fajue jianbao 陝西米脂官莊二號畫像石墓發掘簡報 (Excavation Report on the No. 2 Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings at Guanzhuang, Mizhi County, Shaanxi). In Zhongguo Han Hua Xuehui Di Shisanjie Nianhui Lunwen Ji中國漢畫學會第十三屆年會論文集 (Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Chinese Society of Chinese Painting). Zhongzhou: Zhongzhou Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Yingju 蔣英炬, ed. 2000. Zhongguo Huaxiang Shi Quanji 中國畫像石全集 (Collected Works of Chinese Tomb Reliefs). Jinan: Shandong Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Yingju 蔣英炬, and Wenqi Wu 吳文祺. 1995. Handai Wu Shi Muqun Shike Yanjiu漢代武氏墓群石刻研究 (Study on Stone Carvings of the Wu Family Tombs of Han Dynasty). Beijing: Renmin Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhongyi 黎忠義. 1957. Changli shuiku Han muqun fajue jianbao 昌梨水庫漢墓群發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the Excavation of Han Tombs at the Changli Reservoir). Wenwu Cankao Ziliao 文物參考資料 (References for Cultural Relics Studies) 12: 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Lin 李林. 1990. Shaanxi Suide Yanjiacha erhao huaxiang shimu 陝西綏德延家岔二號畫像石墓 (Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings No. 2 in Yanjiacha, Suide, Shaanxi). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 2: 176–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Lin 李林. 2004. Shaanxi Suide Huangjiata Han dai huaxiang shi muqun 陝西綏德縣黃家塔漢代畫像石墓群 (Han Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Huangjiata, Suide County, Shaanxi). Kaoguxue Jikan 考古學輯刊 (Archaeology Edits) 1: 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Chen. 2018. Han Dynasty Stone Carved Tombs in Central and Eastern China. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Wenjun 梁文駿. 1979. Sichuan Pixian Dong Han zhuanmu de shiguan huaxiang 四川郫縣東漢磚墓的石棺畫象 (Eastern Han Dynasty Sarcophagus with Portraits from a Brick Tomb in Pixian, Sichuan). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 6: 495–503. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Bizhong 林必忠, and Chunhong Liu 劉春鴻. 2007. Chongqing Jiulongpo Taojia Dazhulin huaxiang zhuanmu fajue jianbao 重慶九龍坡陶家大竹林畫像磚墓發掘簡報 (Excavation Briefing on the Tombs with Pictorial Brick Carvings in Dazhulin, Taojiazhen, Jiulongpo, Chongqing). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 2: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Weiyi 鲁惟一. 2009. Handai de Xinyang Shenhua He Lixing 漢代的信仰、神話和理性 (Faith, Myth and Reason in Han China). Translated by Hao Wang 王浩. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luzhou Museum and Chengdu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. 2009. Sichuan Luxian Niushihan yamu qingli jianbao 四川瀘縣牛石函崖墓清理簡報 (Brief Report on the Cleaning of Niushihan Cliff-side Tomb in Lu County, Sichuan). Chengdu Kaogu Faxian 成都考古發現 (Chengdu Archaeological Discoveries) 11: 296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Poo, Muchou. 1998. Search of Personal Welfare: A View of Ancient Chinese Religion. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Jinping 喬晉平, and Lingzhong Kong 孔令忠. 2016. Shanxi Zhongyang Xipo Han mu caihui huaxiang shi 山西中陽西坡漢墓彩繪畫像石 (Pictorial Stone Carvings Painted with Colors from a Han Dynasty Tomb in Xipo, Zhongyang, Shanxi). Wenwu Shijie 文物世界 (World of Cultural Relics) 1: 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Tongliu 商彤流, and Yongsheng Liu 劉永生. 1996. Shanxi Lishi zaici faxian Dong Han huaxiang shi mu 山西離石再次發現東漢畫像石墓 (Eastern Han Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings Discovered Again in Lishi District, Shanxi). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 4: 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Zhaoqing 蘇兆慶, and Anli Zhang 張安禮. 1988. Shandong Juxian Shenliuzhuang Han huaxiang shi mu 山東莒縣沈劉莊漢畫像石墓 (Han Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Shenliuzhuang, Juxian County, Shandong). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 9: 788–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Taichu 孫太初. 1955. Liangnian lai Yunnan gu yizhi ji muzang de faxian yu qingli 兩年來雲南古遺址及墓葬的發現與清理 (The Discovery and Cleaning of Ancient Sites and Tombs in Yunnan in the Past Two Years). Wenwu Cankao Ziliao 文物參考資料 (References for Cultural Relics) 6: 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Changshou 唐長壽. 1987. Leshan Mahao yamu yanjiu 樂山麻浩崖墓研究 (Study on the Leshan Mahao Cliff–side Tomb). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 2: 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tengzhou Han Stone Relief Museum 滕州市漢畫像石館. 2012. Shandong Tengzhou shi Shantoucun Handai huaxiang shi mu 山東滕州市山頭村漢代畫像石墓 (Han Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Shantou Village, Tengzhou City, Shandong Province). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 4: 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tengzhou Museum 滕州博物館. 2002. Shandong Tengzhou shi Sanguo shiqi de huaxiang shi mu 山東滕州市三國時期的畫像石墓 (Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings from the Three Kingdoms Period in Tengzhou, Shandong). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 10: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Lillian Lan-Ying. 2011. Picturing Heaven in Early China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Buyi 王步毅. 1993. Anhui Su xian Chulan Han huaxiang shi mu 安徽宿縣褚蘭漢畫像石墓 (Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Chulan District, Suxian County, Anhui). Kaogu Xuebao 考古學報 (Journal of Archaeology) 4: 515–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jinyuan 王金元. 2000. Lishi shi Shipan Han huaxiang shi mu fajue jianbao 離石市石盤漢畫像石墓發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the Excavation of Han Dynasty Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Shipan, Lishi). Shanxi Sheng Kaogu Xuehui Lunwen Ji 山西省考古學會論文集 (Proceedings of Shanxi Archaeological Society) 4: 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jianzhong 王建中. 2001. Handai Huaxiang Shi Tonglun 漢代畫像石通論 (A General Theory of Han Stone Carvings). Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jinyuan 王金元. 2005. Shanxi Lishi Shipan Handai huaxiang shi mu 山西離石石盤漢代畫像石墓 (Han Dynasty Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Shipan, Lishi, Shanxi). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 2: 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Shuangbin 王雙斌. 2009. Shanxi Lishi Mamaozhuang Jianning simian Han huaxiang shi mu 山西離石馬茂莊建寧四年漢畫像石墓 (Han Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Maomaozhuang, Lishi, Shanxi, fourth year of the Jianning reign period). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 11: 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiaoyang 汪小洋. 2018. Zhongguo Mushi Bihua Shilun 中國墓室壁畫史論 (The History of Chinese Tomb Murals). Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Rulin 王儒林, and Chenguang Li 李陳廣. 1989. Nanyang Han Huaxiang Shi南陽漢畫像石 (Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs in Nanyang). Henan: Henan Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Tingfu 王庭福, and Yihong Li 李一洪. 1995. Hejiang Zhangjiagou erhao yamu huaxiang shiguan fajue jianbao 合江張家溝二號崖墓畫像石棺發掘簡報 (Brief Report on the Excavation of Sarcophagus with Pictorial Stone Carvings from Zhangjiagou No. 2 Cliff-side Tomb in Hejiang). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 5: 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jinyuan 王金元, and Shuangbin Wang 王雙斌. 2006. Lishi Mamaozhuang Han huaxiang shi mu 離石馬茂莊漢畫像石墓 (Han Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Mamaozhuang, Lishi). San Jin Kaogu 三晉考古 (Three-Jin Archaeology) 3: 257–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Kai 王愷, Kaichen Xia 夏凱晨, Xuzhou Museum 徐州博物館, and Xinyi County Library 新沂縣圖書館. 1985. Jiangsu Xinyi Wayao Han huaxiang shi mu 江蘇新沂瓦窯漢畫像石墓 (Han Tomb with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Wayao, Xinyi, Jiangsu). Kaogu 考古 (Archaeology) 7: 614–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 1989. The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Lan 吳蘭. 1992. Suide Wuyequancun huaxiang shi mu 綏德嗚咽泉村畫像石墓 (Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in WuyequanVillage, Suide). Wenbo 文博 (Cultural Relics and Museology) 5: 39. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung 巫鴻. 2005. Liyi Zhong De Meishu 禮儀中的美術—巫鴻中國古代美術史文編 (Art in Its Ritual Context: Essays on Ancient Chinese Art). Beijing: Sanlian Shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2010. Art of the Yellow Springs. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Jianyi 肖健一, Ningwu Kang 康寧武, Genrong Cheng 程根榮, and Aihong Shang 尚愛紅. 2011. Shanxi Shenmu Dabaodang Dong Han huaxiang shi mu 陝西神木大保當東漢畫像石墓 (Eastern Han Tombs with Pictorial Stone Carvings in Dabaodang, Shenmu, Shaanxi). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 12: 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Li 謝荔. 1991. Luzhou bowuguan shoucang Handai huaxiang shiguan kaoshi 瀘州博物館收藏漢代畫像石棺考釋 (A Textual Research and Explanation of the Han Dynasty Sarcophagus with Pictorial Stone Carvings Collected by Luzhou Museum). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 3: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Lin 徐琳. 2006. Handai Wanghou Muzang Chutu Yuqi Yanjiu 漢代王侯墓葬出土玉器研究 (Study on the Jade Unearthed from the Tombs of Princes of the Han Dynasty). Ph.D. dissertation, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Ling 顏靈. 1996. Nanxi xian Changshunpo huaxiang shiguan qingli jianbao 南溪縣長順坡畫像石棺清理簡報 (Brief Report on Cleaning the Sarcophagus with Pictorial Stone Carvings at Changshunpo, Nanxi County). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 (Sichuan Cultural Relics) 3: 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Aiguo 楊愛國. 2006. Youming Liangjie 幽冥兩界:紀年漢代畫像石研究 (Of the World of the Dead and the World of the Living—A Study of the Stone Carvings of the Han Dynasty). Xi’an: Shaanxi Renmin Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, Tadao. 2011. Xiwang mu 西王母 (Queen Mother of the West). In The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, vol. 2, M–Z, pp. 1119–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Qiuwei 於秋偉, Zhenhua Pan 潘振華, Hua Zhu 朱華, Chuanling Yin, Tao Sun, Hao Ruan, Xihui Yang, and Shanyi Liu. 2018. Shandong Fei xian Liujiatong Han huaxiang shi mu fajue jianbao 山東費縣劉家疃漢畫像石墓發掘簡報 (Excavation Report on a Han Tomb with Pictorial Stones in Liujiatuan, Feixian County, Shandong Province). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 9: 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Cultural Relics Team 雲南省文物工作隊. 1960. Yunan Zhaotong wenwu diaocha jianbao 雲南昭通文物調查簡報 (Brief Investigation Report on the Cultural Relics in Zhaotong, Yunnan). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 6: 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Wuchang 鄭午昌. 2009. Zhongguo Huaxue Quanshi 中國畫學全史 (A Complete History of Chinese Painting). Changchun: Shidai Wenyi Chubanshe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Zhi 鍾治. 2002. Sichuan Santai Qijiang yamu qun 2000 niandu qingli jianbao 四川三臺郪江崖墓群2000年度清理簡報 (Annual Report on the Cleaning of the Qijiang Cliff-side Tombs in Santai, Sichuan, 2000). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 1: 16–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shuili 周水利. 2010. Anhui Xiao xian xin chutu de Handai huaxiang shi 安徽蕭縣新出土的漢代畫像石 (Newly Unearthed Han Dynasty Pictorial Stone Carvings in Xiaoxian County, Anhui). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) 6: 59–65. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Images That Feature the Queen Mother and/or the King Father | Images of the Queen Mother Only | Images That Feature Both the Queen Mother and the King Father | Images of the King Father Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | 52 | 31 | 19 | 2 |

| Name of the Fu Writer | Fu Works that Feature the Queen Mother | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Sima Qian | “Daren fu” 大人賦 (Rhapsody on the Great Man) | Shiji (117.2999–3057) Hanshu (57A.2529–2577) Hanshu (57B.2577–2613) |

| Yang Xiong | “Ganquan fu” 甘泉賦 (Rhapsody on the Sweet Springs) | Hanshu (87.3513–3557) Hanshu (87.3557–3589) |

| Ban Biao | “Lanhai fu” 覽海賦 (Rhapsody on Viewing the Sea) | Hanshu (100.4167–4235) Hou Hanshu (49.1323–1330) |

| Zhang Heng | “Sixuan fu” 思玄賦 (Rhapsody on Contemplating the Mystery) | Hou Hanshu (59.1897–1951) |

| Name | Source | Content | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Song Weijia宋威甲, Song Wenjia宋文甲 | Han Tomb at Yangguan Monastery 楊官寺, Nanyang 南陽 County, Henan Province | Song Weijia, and Song Wenjia | Late Western Han |

| [Surname unknown] Yi □宜 | Han Tomb at Yangguan Monastery, Nanyang County, Henan province | Yi from Lu, a stonemason | 17th year of the Yongyuan reign (105AD) |

| Zhang Boyan 張伯□(嚴) | Stone Stele with the Portrait of Wang Xiaoyuan王孝渊 in Xipu 犀浦, Pixian 郫縣 County, Sichuan Province | Zhang Boyan, a craftsman | 3rd year of the Yongjian reign (128 AD) |

| Wei Zheng 衛政 | Inscriptions on The Wu Liang 武梁 Shrine, Jiaxiang 嘉祥 County, Shandong Province | Wei Zheng, a good craftsman | Mid- to Late- Eastern Han |

| Wang Shu王叔, Wang Jian 王堅, etc. | Caption to the Portrait of Anguo 安國 in Songshan 宋山 Village, Mantong 滿硐 Township, Jiaxiang County, Shandong Province | Famous craftsmen such as Wang Shu, Wang Jian, etc. | 3rd year of the Yongshou reign (157 AD) |

| Tomb Occupants | Princes | Prefects | Lower Ranking Officials | Commoners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of tombs with stone reliefs | 1 | 5 | 18 | 35 |

| Genre | Book Title | Occurrence Number | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Works | Origins of Things (Shiben 世本) | 1 | 8 |

| The Great Commentary to the Book of Documents (Shangshu dazhuan 尚書大傳) | 2 | ||

| Shiji | 2 | ||

| Hanshu | 3 | ||

| Masters’ Philosophical Works | New Writings (Xinshu 新書) | 1 | 5 |

| Huainanzi 淮南子 | 1 | ||

| Records of Rites by Dai the Elder (Dadai liji 大戴禮記) | 1 | ||

| Discourses Weighed in the Balance (Lunheng 論衡) | 1 | ||

| The Numinous Constitution of the Universe (Lingiian 靈憲) | 1 | ||

| Philological Studies | Approaching Correct Meanings (Erya 爾雅) | 1 | 1 |

| Han Rhapsodies | “Rhapsody on the Great Man” | 1 | 4 |

| “Rhapsody on the Sweet Springs” | 1 | ||

| “Rhapsody on Viewing the Sea” | 1 | ||

| “Rhapsody on Contemplating the Mystery” | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wang, S. On the Differences between Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings in Their Portrayal of the Queen Mother of the West and Their Religious Significance. Religions 2022, 13, 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040327

Wang X, Wang S. On the Differences between Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings in Their Portrayal of the Queen Mother of the West and Their Religious Significance. Religions. 2022; 13(4):327. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040327

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaoyang, and Shixiao Wang. 2022. "On the Differences between Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings in Their Portrayal of the Queen Mother of the West and Their Religious Significance" Religions 13, no. 4: 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040327

APA StyleWang, X., & Wang, S. (2022). On the Differences between Han Rhapsodies and Han Paintings in Their Portrayal of the Queen Mother of the West and Their Religious Significance. Religions, 13(4), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040327