Nursing Enlightenment and a Grudge—Reinventing the Medieval Virgin’s Benevolent Breasts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

jocular tales… are perplexing if we choose to consider them as tales aimed at attacking women. Even a casual reading suggests that the real target is either the complaisant husband, who is so expertly cuckholded, or the naïvely unaware ascetic, who is tempted sexually by the supposedly wicked woman.

E aunque seré de algunos reprehendido por non saber ellos mi entinçión–la qual solo Dios sabe en este paso non ser a mala parte–porque algunas cosas pongo en prática dirán que más es avisar en mal que corregir en bien. Diga cada qual su voluntad, que yo non lo digo por que lo así fagan, mas porque sepan que por mucho que ellos nin ellas encobierto lo fagan e fazen, que se sabe, e algunos sabiéndolo, a sus mugeres, fija e parientas castigarán.

And some people will scold me (since they don’t understand my intention, which in this instance God only knows is not wicked) because I show how some things are done, saying that I’m more interested in giving lessons in how to put wickedness into practice than in giving good examples to follow. Let everyone say what he thinks best. But I’m not relating this so that they’ll do things that way but so they they’ll know that, no matter how much they (either men or women) do or might do in secret, that their tricks are known and that some men, because they know it, will be able to give proper lessons to their wives, daughters, and female relatives.

“O, o, del latte della Vergine Maria; o donne, dove siete voi? E anco voi, valenti uomini, vedestene mai? Sapete che si va mostrando per reliquie: non v’aviate fede, ché elli non è vero: elli se ne truova in tanti luoghi! Tenete che non è vero. Forse che ella fu una vacca la Vergine Maria, che ella avesse lassato il latte suo, come si lassa delle bestie, che si lassano mugnare?

And, oh, oh, by the way, the milk of the Virgin Mary! Ladies, where are your heads? And you, fine sirs, have you seen any of it? You know, they’re passing it off as a relic. It’s all over the place. Don’t you believe in it for a moment. It’s not real. Don’t you believe it! Do you think the Virgin Mary was a cow, that she would give away her milk in this way—just like an animal that lets itself be milked?(qtd. in Rubin 2009, p. 300)

2. The Virgin Mother of God: Mary’s Cultural Importance

When I enter a church, I contemplate images of Jesus Christ’s miracles and his mother suckling Our Lord, and Our Lord in her arms, while angels around them sing a hymn sanctus, sanctus, sanctus

Demandóli el clérigo que yazié dormitado,

“¿Quí eres tú que fablas? Dime de ti mandado,

ca cuando lo dissiero seráme demandado

quí es el querelloso o quí el soterrado.”

Díssoli la Gloriosa: “Yo so Sancta María

madre de Jesu Christo que mamó leche mía;

el que vos desechastes de vuestra compannía,

por cancellario mío yo a éssi tenía.

The cleric, who had been sleeping, asked Her:/“Who are you who speaks? Tell me, whom you command/for when I say this I will be asked/who the aggrieved one is or who the buried one is.”/The Glorious One responded: “I am Holy Mary,/Mother of Jesus Christ, who suckled My milk./The one you excluded from your company,/I held as a chancellor of Mine.”

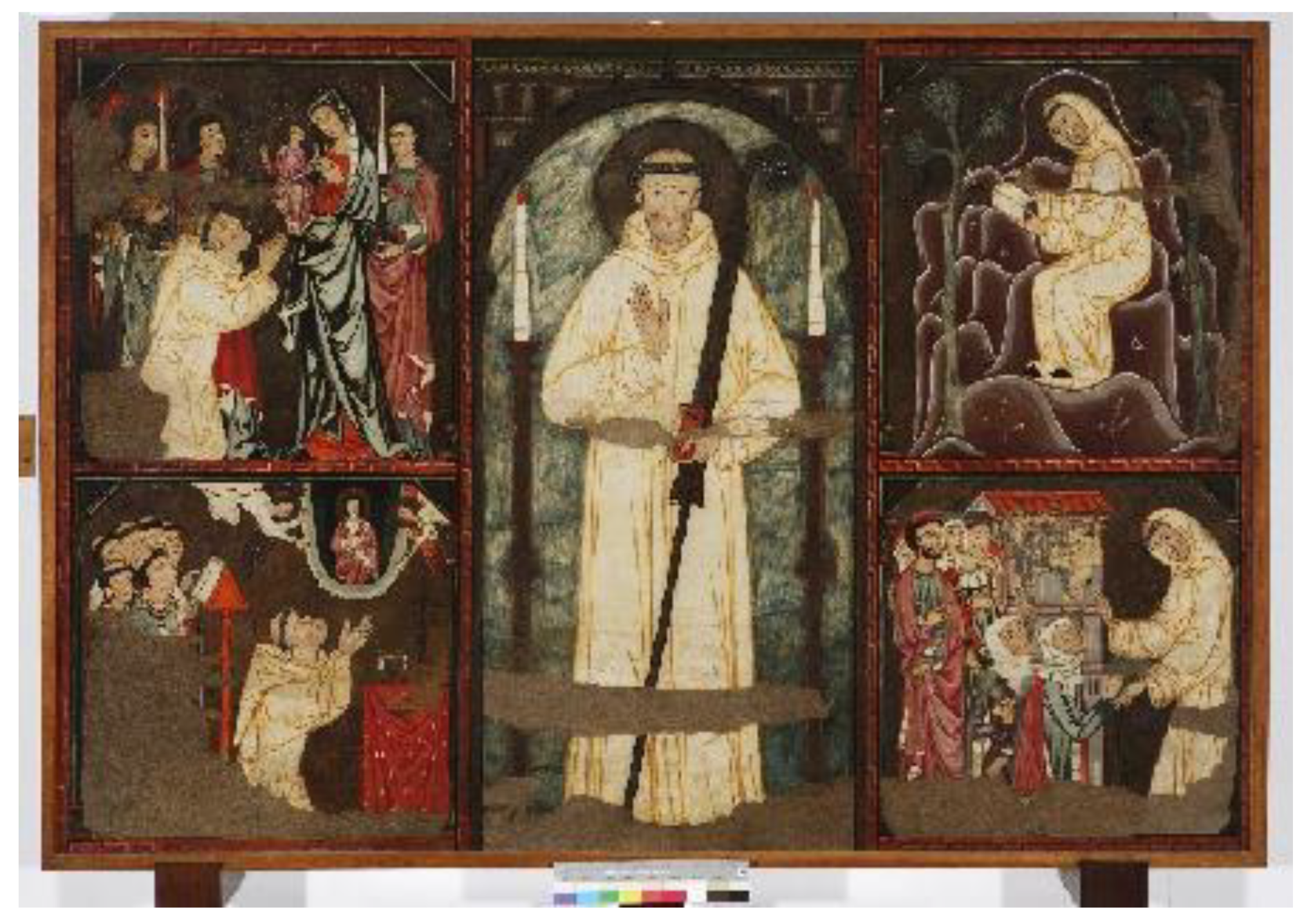

E u el a todos parecerá mui sannudo

entôn fas-ll’ enmente de como foi concebudo....

E en aquel día, quand’ ele for mais irado,

fais-lle tu emente com’ en ti foi enserrado....

U verás dos santos as compannas espantadas,

móstra-ll’ as tas tetas santas que houv’ el mamadas....

E u mostrar ele tod’ estes grandes pavores,

fas com’ avogada, ten vóz de nós pecadores

que polos téus rógos nos lév’ ao paraíso

séu, u alegría hajamos por sempr’ e riso.

And when he appears to all in great wrath,/then make him remember how he was conceived…./And on that day when he is most wrathful,/make him remember how he was enveloped by you…/When you see the frightened hosts of saints,/show him your holy breasts which he sucked…/And when he reveals all these terrible things,/take on the role of Advocate and plead for us sinners,/so that, because of your prayers, He take us to His paradise/where we may have joy and laughter forevermore.

Cantiga 46: The Moor who Venerated an Image of the Virgin Mary

Cantiga 54: The Monk who was Healed by the Virgin’s Milk

Cantiga 93: The Leper who was Healed by the Virgin’s Milk

Cantiga 138: John Chrysostom’s Vision

Cantiga 404: The Priest who was Healed by the Virgin’s Milk

(Oxford Cantigas de Santa María Database, accessed on 21 March 2022)15

y esto hace que las pinturas, no solamente narrativas, sino también las puramente rituales o devocionales, se hagan ahora más humanas, más realistas, más accesibles a la devoción personal”.

And this allows painting, not merely the narrative ones, but also those purely ritualistic and devotional, become more humane, more realistic, more accessible to personal devotion.

La prima si è d’avere dipinture in casa di santi fanciulli o vergine giovanette, nelle quali il tuo figliuolo, ancor nelle fascie, si diletti come simile e dal simile rapito, con atti e segni grati alla infanzia. E come dico di pinture, cosi dico di scolture. Bene sta la Vergine Maria col fanciullo in braccio, e l’uccellino o la melagrana in pugno. Sarà buona figura Iesu che poppa, Iesu che dorme in grambo della Madre; Iesu le sta cortese innanzi, Iesu profila ed essa Madre tal profilo cuce.

The first rule is to have pictures of saintly children or young virgins in the home, in which your children, still in swaddling clothes, may take delight and thereby be gladdened by acts and signs pleasing to childhood. And what I say of pictures applies also to statues. It is well to have a Virgin Mary with the Child in arms, with a little bird or apple in His hand. There should be a good representation of Jesus nursing, sleeping in His Mother’s lap or standing courteously before Her while they look at each other.

3. A Strange Hypothesis: The Lactation of St. Bernard

…pario siete fijos & los seys varones & la vna fembra & los varones fueron monjes & la fenbra monja Et luego que pario el fijo lo tomaua en las manos & lo ofrescia a jhesu christo & criaualos a sus tetas dandoles con la leche las costumbres que auia ella mesma e cresciendo en quanto estauan sso su poderio & rregimiento mas los criaua para monjes que para seglares

…gave birth to seven children, six sons and one daughter. The sons were all monks and the daughter a nun. After [giving] birth to a child she would take him in her hands and offer him to Jesus Christ. And she suckled them at her breast, transferring her virtues through her milk. And while they were raised under her authority and tutelage, she raised them to become monks rather than laypersons.

Por su virtud y limpieza

El melifluo san Bernardo,

Por su devoción tan alta

La Virgen un don le ha dado.

Hizole su capellán

Muy querido y regalado,

Y estando ante él un día

En oración transportado,

Puso la Virgen la mano

En su pecho consagrado,

Y con divina leche

Los labios le ha rociado.

The Virgin has given the mellifluous Saint Bernard a gift on account of his virtue and integrity and his supreme devotion. She made him her beloved and prized chaplain. While he was transported through prayer one day, appearing before him the Virgin placed her hand on her consecrated breast and moistened his lips with divine milk.

Todo esto fue efecto de aquel tan supremo regalo con que la Sacrasantissima Virgen y sin mancilla Maria endulço su voz, su pluma, y su lengua, siendo para todos atractivo suaue su doctrina. Y aunque es dulcissimo en todas sus Obras, Y Escritos este Docto Melifluo; pero donde incomparablemente vierten suauidad sus Sermones y Platicas, es en los Mysterios Inefables, y Sacrosantos del Hijo de Dios, como son, su Encarnación y Glorioso Nacimiento; y en las alabanças de la Sanctissima Virgen Maria, todo es suauidad, agudeza, y dulçura. Mamólo todo de los Pechos desta Reyna Virgen, Y Madre, para que suauemente atraxesse al seruicio de su Hijo, y suyo a los hombres: y desterrasse con su predicacion las amarguras, y azedias de la culpa, con lo sazonado, y meloso de sus palabras.

All of this was the effect of the supreme gift with which the most sacred and pure Virgin Mary sweetened his [Bernard’s] voice, his pen, and his tongue, making his teaching tender and attractive. Even though this mellifluous doctor is very sweet in all his works and writing, where his Sermons and Letters pour the most tenderness is in the discussion of ineffable and sacrosanct mysteries of the Son of God, which are, his incarnation and glorious birth. Additionally, in the praises of the most holy Virgin Mary, he is all tenderness, insight[fulness], and sweetness. He suckled this all at the breasts of our Virgin Queen and Mother, so that he might gently be drawn to the service of her Son, and so that men be drawn to his service, and so that he might banish with his preaching all sorrow and remorse over blame, with his sweetly expressive words.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Michael Gerli’s edition of the Arcipreste de Talavera o Corbacho has been used in this article. English translations are based on Eric Naylor and Jerry Rank’s translation, albeit in some cases slightly modified. All other translations, unless noted, are mine. |

| 2 | Tales of adulterous deception play largely in the catalogue of folklore motifs identified by Stith Thompson (1955–1958) and Harriet Goldberg (1998), but this one is unique to the Archpriest’s story. The complete episode is as follows: “Contarte he un enxiemplo, e mill te contaría: una muger tenía un ombre en su casa, e sobrevino su marido e óvole de esconder tras la cortina. E quando el marido entró dixo: “¿Qué fazes, muger?” Respondió: “Marido, siéntome enojada.” E asentóse el marido en el banco delante la cama, e dixo: “Dame a çenar.” E el otro que estava escondido, non podía nin osava salir. E fizo la muger que entrava tras la cortina a sacar los manteles, e dixo al ombre: “Quando yo los pechos pusiere a mi marido delante, sal, amigo, e vete.” E así lo fizo. Dixo: “Marido, non sabes cómo se ha finchado mi teta, e ravio con la mucha leche.” Dixo: “Muestra, veamos.” Sacó la teta e diole un rayo de leche por los ojos que lo cegó del todo, e en tanto el otro salió. E dixo: “¡O fija de puta, cómo me escuece la leche!” Respondió el otro que se iva: “¿Qué debe fazer el cuerno?” E el marido, como que sintió ruido al pasar e como non veía, dixo: “¿Quién pasó agora por aquí? Paresçióme que ombre sentí.” Dixo ella: “El gato, cuitada, es que me lieva la carne.” E dio a correr tras el otro que salía, faziendo ruido que iva tras el gato, e çerró bien su puerta e tornóse, corrió e falló su marido, que ya bien veía, mas non el duelo que tenía” (Gerli 1992, p. 188). [I’ll tell you a tale, and I could tell you a thousand. A woman had a man in her house and her husband came back unexpectedly, and she had to hide him behind the curtain. And when her husband came in he asked: “What are you up to, wife?” She answered: “Husband, I feel a little indisposed.” And her husband sat down on the bench in front of the bed and said: “Give me some supper.” And the other man who was hidden [neither could] nor dared to leave. And the woman pretended that she was going behind the curtain to get out the tablecloths and said to the man: “When I stick my tits in front of my husband, scram, sweetheart, and get yourself out of here.” And this is what she did. She said: “Husband, you don’t realize how my breast has swelled; and I’m dying because there’s so much milk.” He said: “Let’s see: show me.” And she took out her breast and gave him a squirt of milk in the eye and completely blinded him, and in the meanwhile the other man started out. And the husband said, “O son of a bitch, how the milk smarts.” The other man who was going out answered: “I bet horns hurt more!” And the husband, since he heard noise as the other man passed by and since he couldn’t see, said: “Who just passed by? I thought I heard a man.” She said: “It’s the cat, woe is me, and he’s carrying my meat off.” And she started running after the other man who was leaving, making noise like she was going after the cat, and she shut the door tight and went back and found her husband who could see fine now but who couldn’t manage to see his own grief” (Naylor and Rank 2011, p. 133). |

| 3 | This translation does not follow Naylor and Rank in order to preserve the gendered insult. |

| 4 | See Emilie Bergmann (2002) and Caroline Castiglione (2013) for the cultural significance and social practices regarding breastfeeding, and the use of wetnurses. Much of our understanding about breasfeeding in the Middle Ages comes from studies that point out how wetnurses were chosen and for how long they were employed. Curiously, one of the first literary mentions to wetnurses exemplifies the before mentioned need to select the proper woman. The Libro de Alexandre notes that the ancient Macedionian king “nunca quiso mamar leche de mugier rafez,/si non fue de linaje o de grant gentilez” (7cd) [never wanted to suckle the milk of a common woman, only a noble or a woman of good manners] (Casas Rigall 2014, p. 6). |

| 5 | It is not unusual to see in medieval Castilian narratives an insisting that one be understood correctly. In the Archpriest of Talavera, Juan Ruiz cautions against the deliberate mishandling of his work. Sin is an intrinsic part of human nature. The negative examples in the Libro de buen amor are not intended to promote sin, even though those who want to sin will find in the reading a way to do it. |

| 6 | An ambivalent connection between mother and suckling child may be seen in The Libation-Bearers. In Aeschylus’s tragedy, Clytemnestra futilely begs her son Orestes for mercy. Clytemnestra leans on the bond established between mother and suckling child. It is not enough. |

| 7 | Anthony Cárdenas notes these versions (chapter 510 of the Estoria de España, cantiga 2 from the Cantigas de Nuestra Señora, and a marginal gloss in mss. T.1.1), although only two are considered to belong to the wise king (Cárdenas 1983, pp. 339–40). These versions refer to one or both of the Virgin Mary’s miraculous appearances to the sainted bishop. In the first, she appears with his book in her hands, gratified by his literary defense of her virginity before the heretics who questioned it. In the second, she appears with a fine vestment, a chasuble, also as recompense for his defense. |

| 8 | José Madoz y Moleres notes few adaptations in the Archpriest’s translation of Ildephonsus’s life from the sources used by the fifteenth-century writer. Nevertheless, in the Archpriest’s translation of filius hominis for hijo de la Virgen, one might understand Martínez’s veneration for the Mother of God. |

| 9 | These are the celebration of the Nativity (December 25), the Purification (February 2), the Incarnation of the Word in Mary (March 21), the Assumption (August 15), the Nativity of Mary (September 8), and the Annunciation of Mary’s Birth (December 18). |

| 10 | Lesley Twomey notes that early examples of literature from the Iberian peninsula were marked by devotion to the Virgin and her appearance within the Protoevangelicum. Art historians have leaned on this and other apocryphal gospels, as well as on the saintly tales that brought out much of the humanity represented in the figures of the Virgin. |

| 11 | Geographical and familial ties lie at the heart of many hagiographic narratives. Saints are often associated with a particular place and are configured as a symbolic father or mother for that village, town, or city. The work of Jacobus da Voragine (1230–1298) expanded the importance of saints beyond the local, tribal level. His Golden Legend included the lives of many saints and martyrs; it also included stories that told the life of Mary. The Golden Legend extended Mary’s profile throughout the European continent and created numerous opportunities to see Mary in the role of divine mother. |

| 12 | Martínez de Toledo and de Talavera (2010) composes the hagiographic tale Vida de San Ildefonso, in which he emphasizes the virginal purity of Mary. Martínez disabuses those who believed “un omne sabidor… Elbidio,” whose teachings proclaimed that Mary had not remained a virgin after Jesus’s birth. He refutes this idea with a direct appeal to the Virgin on behalf of all humankind, claiming that the righteous know that Mary was sanctified in her mother’s womb by the Holy Spirit, and that after having conceived through the Holy Spirit she had a virgin birth of Jesus Christ (Madoz y Moleres 1962, p. 86). |

| 13 | Andrachuk’s article deals specifically with the definition of the word “adonado.” For him, the word cannot simply be translated as “full of grace” but rather “full of the gift that is Jesus Christ”. |

| 14 | Angela Vaz Leãno attributes the many references to breastmilk within the Cantigas de Santa María, a collection of over four hundred Marian miracle tales, to fecund pagan divinities. She notes, “[a] força e a extensão do culto mariano se explicam, entre outras causas, pela sua associação ao mito femenino, presente em religiões pré-históricas e atestado por estatuetas de mulhiere nuas, muitas vezes estilizadas e com seus órgãos sexuais exagerados, tais como se entraram em várias escavações, sobretudo no Oriente Médio. Eram imagens da Grande-Mãe, cujo culto a identificava às vezes com a Terra e que assim se espalhou pelo Mediterrâneo” (Vaz Leão 2007, p. 118). [The strength and wide-spread circulation of the Marian cult may be explained, among other reasons, by her association with the feminine myth, present in prehistoric religions and represented by small statues of female nudes, many of them stylized and with exaggerated sexual organs, as have been found in multiple excavations, especially in the Middle East. These were images of the “Great Mother,” whose cult sometimes identified her with the Earth Mother and in this form spread throughout the Mediterranean.]. |

| 15 | These are the summarized titles given in the Oxford Database. In Portuguese, they are as follows: Cantiga 46: “Esta é como a omagen de Santa Maria, que un mouro guardava en sa casa onrradamente, deitou leite das tetas.” 54: “Esta é como Santa Maria guaryu con seu leite o monge doente que cuidavan que era morto.” Cantiga 93: “Como Santa Maria guareceu un fillo dun burges que era gafo.” Cantiga 138: “Como San Joan Boca-d’Ouro, porque loava a Santa Maria, tiraron-ll’os [ollos] e foi esterrado e deitado de patriarcado; e depois fez-lle santa Maria aver ollos, e cobrou per ella sa dinidade.” Cantiga 404: “Como Santa Maria, com seu leite, cura um jovem clérigo seu devoto de grande enfermidade”. |

| 16 | Enrique II and his family appear in the bottom corners of the tempera panel. Enrique had been in exile in Aragón and under the protection of the Aragonese king, Pere IV. Pilar Silva Maroto notes that Enrique II commissioned three retables for the Nuestra Señora del Tobed sanctuary in Zaragoza between 1356 and 1359. Notarial documents also indicate that by 1359, the altar for the side panels to the Virgen del Tobed had been completed (Silva Maroto 2006). |

| 17 | The Prado Museum documents Jaume Serra to have been active circa 1358–1390. Destorrents is thought to have worked between 1351 and 1362. Lorenzo Zaragoza may have outlasted both, as he is documented from 1363 until 1406 (Archiniega García 32). Ramón de Mur was active between 1412 and 1435, according to the Museo National d’Art de Catalunya (Mur 2022). There is a curious website (Art+E 2022) with a catalog of Madonna lactans images: www.historia-del-arte-erotico.com/cleopatra/home.htm. While offering very little description of the images it contains, this website catalogs a vast number of images throughout the European continent, many of which are painted in the same International Gothic style as those described in this article. |

| 18 | Images of a nursing Eve may also be found within Christian art, which are used as the basis of a figural exegesis foretelling Mary’s future redemptive role. Examples of the nursing Eve image can be seen on the eleventh-century Bernward Doors, made for the Hildesheim Cathedral; in the thirteenth-century relief of a portal to the Upper Chapel in Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, and in the stained glass paneling of the Rheims Cathedral of Notre Dame. |

| 19 | Rubin attests to this in her Mary, Mother of God (Rubin 2009, p. 150), while Rafael Durán denies it (Durán 1990, p. 40). Others note that the story first appears in art, as part of an altarpiece from a Mallorcan Templar Church, circa 1290. This altar was dedicated to the Cistertian monk and tells his life in pictures (Bauer, Salvadó). Louis Rèau believes that the first images of St. Bernard’s lactational miracle may be dated to 1200; the first narrative stories of this miracle may be dated to about 1350 (qtd. in González Zymla 2019, p. 212; Réau 1955–1959, pp. 215–20). |

| 20 | |

| 21 | The Osma Master paints a retable dedicated to Saint Ildephonsus in the Catedral de Burgo de Osma during the second half of the fifteenth century, as does Martín Bernat for a retable in the Tarrazona Cathedral (Zaragoza). An additional altarpiece, attributed to the Master of La Seu de Urgel, whose Retablo de la Mare de Déu de Canapost is also known as the Retablo de la Virgen de la Leche, dates to the last quarter of the fifteenth century. |

| 22 | Bernard supported the creation of the Order of the Templars during the 1129 Council of Troyes. While there is no consensus as to the part he played in creating the Templar rule, he did write De laude novae militiae [In Praise of the New Knighthood] to exhort Templar knights in the crusade. |

| 23 | Rafael Durán also includes within his Iconografía española a plate from a Cordoban Cathedral Chapter Office of the Virgin with Saints Bernard and Ildephonsus. While the painting contains the Madonna lactans icon, the lactational miracle is not present. |

| 24 | Durán traces the appearance of this miracle both in and outside of the Iberian peninsula. He cites its appearance in Guillermo Eysengreinio’s Crónica de Espira from 1561. Durán also notes the lactational miracle in an authenticum dated 1599 from Edmundo de la Croix, the Abbot General of the Cistercian Order to Fr. Fermín Ignacio de Ibero, the Fietro monastery abbot, which attests to the location of the miracle in Châtillon-sur-Seine. A larger narrative of Saint Bernard presumably appears in the Historia de la esclarecida Vida y Milagros del Bienaventurado Padre y Mellifluo Doctor San Bernardo, which was a compilation by F. Cristóbal González de Perales that was published in 1601. Cistercian historians make the story more well known in the seventeenth century; their devotion to the saint may be seen in monasteries throughout the eighteenth century (Durán 1990, pp. 41–43). |

References

- Almonacid, José de. 1682. Vida y Milagros del Glorioso Padre y Doctor Melifluo San Bernardo. Madrid: Francisco Sanz, Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=QAY8G2DK7u8C&pg=PA562&lpg=PA562&dq=milagros+cister&source=bl&ots=y8e0nNHXDz&sig=ACfU3U2Bdzw_2c4s0JxNOuIbDh9kwwM9Ng&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-wojp8O7uAhV0EVkFHeVZC-Q4ChDoATAAegQIAxAC#v=onepage&q=bernardo%20maria&f=false (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- Andrachuk, Gregory Peter. 2017. La Gloriosa, ess cuerpo adonado: The Body of Mary in Berceo’s Milagros de Nuestra Señora. eHumanista 35: 534–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega García, Luis. 1995. Lorenzo Zaragoza, Autor del Retablo Mayor del Monasterio de San Bernardo de Rascaña, Extramuros de Valencia (1385–1387). Available online: https://www.uv.es/arcinieg/pdfs/lorenzo_zaragoza_retablo_san_bernardo_rascanya_Luis_Arciniega.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Art+E. 2022. Available online: http://www.historia-del-arte-erotico.com/cleopatra (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Bauer, Doron. 2015. Milk as Templar Apologetics in the St. Bernard of Clairvaux Altarpiece from Majorca. Studies in Iconography 36: 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Emilie. 2002. Milking the Poor: Wet Nursing and the Sexual Economy of Early Modern Spain. In Marriage and Sexuality in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia. Edited by Eugene Lacarra Lanz. New York: Routledge, pp. 90–116. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca de Autores Españoles. 1855. Romancero y Cancionero Sagrados. Poesías Cristianas, Morales y Divinas. Sacadas de las obras de los Mejores Ingenios Españoles por Don Justo de Sancha. Madrid: M. Rivadeneyra. [Google Scholar]

- Blaya Estrada, Nuria. 1995. La Virgen de la Humildad. Origen y significado. Ars Longa: Cuadernos de Arte 6: 163–71. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, James. 1998. Desire against the Law the Juxtaposition of Contraries in Early Medieval Spanish Literature. Stanford: Stanford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, Anthony. 1983. Tres versiones del milagro de San Ildefonso en los códices de la cámara regia de Alfonso el Sabio. In Actas del VIII Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas: 22–27 agosto 1983. Edited by Coords. A. David Kossoff, Ruth H. Kossoff, Geoffrey Ribbans, José Amor and Vázquez. Madrid: Istmo, vol. 1, pp. 339–47. [Google Scholar]

- Casas Rigall, Juan, ed. 2014. Libro de Alexandre. Madrid: RAE. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, Andrew. 2022. Cantiga 422: Lyrics: Madre de Déus, óra por nós téu Fill’ essa hóra. Cantigas de Santa María. Available online: http://www.cantigasdesantamaria.com/csm/422 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Castiglione, Caroline. 2013. Peasants at the Palace. Wet Nurses and Aristocratic Mothers in Early Modern Rome. In Medieval and Renaissance Lactations. Edited by Jutta Gisela Sperling. London: Routledge, pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, Giovanni. 1860. Regola del governo di cura Familiare. Edited by Donato Salvi. Florence: Presso Angiolo Garinei Libraio. [Google Scholar]

- Dominici, Giovanni. 1927. Regola del Governo di cura Familiare, Parte Quarta: “On the Education of Children,” By Giovanni Dominici. Coté, Arthur Basil, trans. Ph.D. dissertation, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dorger, Cecelia M. 2012. Studies in the Image of the Madonna Lactans in Late Medieval and Renaissance Italy. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, Rafael. 1990. Iconografía Española de San Bernardo. Poblet: Monasterio de Santa Mariá de Poblet. [Google Scholar]

- Gerli, Michael. 1969. Monólogo y diálogo en el Arcipreste de Talavera. Revista de Literatura 36: 107–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gerli, Michael. 1988. Milagros de Nuestra Señora. Edited by Gonzalo de Berceo. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Gerli, Michael. 1992. Arcipreste de Talavera, 4th ed. Edited by Alfonso Martínez de Toledo. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Ryan. 2009. Introduction: Saints and Anti-Saints. In The Laughter of the Saints: Parodies of Holiness in Late Medieval and Renaissance Spain. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Harriet. 1983. Sexual Humor in Misogynist Medieval Exempla. In Women in Hispanic Literature. Icons and Fallen Idols. Edited by Beth Miller. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Harriet. 1998. Motif-Index of Medieval Spanish Folk Narratives. Tempe: Medieval and Renaissance Texts & Studies. [Google Scholar]

- González Zymla, Herbert. 2019. La iconografía del premio lácteo de San Bernardo en el Monasterio de Piedra. In Monasterio de Piedra, un Legado de 800 años. Historia, Arte, Naturaleza y Jardín. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, pp. 208–33. [Google Scholar]

- Grant Cash, Annette, and Richard Terry Mount. 1997. Miracles of Our Lady. Edited by Gonzalo de Berceo. Lexington: Studies in Romance Languages, UPK. [Google Scholar]

- Kulp-Hill, Kathleen. 2000. Songs of Holy Mary of Alfonso X, the Wise: A translation of the Cantigas de Santa María. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Lappin, Anthony. 2008. Gonzalo de Berceo: The Poet and His Verses. Serie A: Monografías, 268. Woodbridge: Tamesis. [Google Scholar]

- Lembrí, Pere Museo del Prado. 2022. Available online: https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/la-virgen-de-la-leche-con-el-nio-entre-san/9b376cb9-cb0b-4fb1-80c2-12da1fdd09f6 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Leyenda Aurea. 1400–1499. MSS/12689. Biblioteca Nacional de España. Available online: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000253554&page=1 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Libro de Horas. 1490–1500. Horas de Philippes Bigota RES/281. Biblioteca Nacional de España. Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000008624 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Madoz y Moleres, José. 1962. Vidas de San Ildefonso y San Isidro. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez de Toledo, Alfonso, and Arcipreste de Talavera. 2010. Vida de San Ildefonso. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, Available online: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmcqn627 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Menéndez y Pelayo, Marcelino. 2012. Historia de las Ideas Estéticas en España. Spain: Editorial de la Universidad de Cantabria. [Google Scholar]

- Miquel Juan, Matilde. 2015. La novedad de lo desconocido. Las aportaciones foráneas como elemento de lujo y ostentación en los retablos medievales valencianos. In Mercados de lujo, Mercados del arte. El gusto de las Élites Mediterráneas en los Siglos XIV y XI. Edited by Juan Vicente García Marsilla and Sophie Brouquet. Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de Valencia, pp. 503–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mormando, Franco. 1999. The Preachers’ Demons: Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mur, Ramon. 2022. Museo National d’Art de Catalunya. Available online: https://www.museunacional.cat/es/colleccio/virgen-de-la-leche/ramon-de-mur/015818-000 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Naylor, Eric W., and Jerry R. Rank. 2011. The Archpriest of Talavera by Alonso Martínez de Toledo. In Dealing with the Vices of Wicked Women and the Complexions of Men. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Cantigas de Santa María Database. 2005. Oxford: Centre for the Study of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, Available online: http://csm.mml.ox.ac.uk/index.php?p=poem_list (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Réau, Louis. 1955–1959. Iconographie de l’art Chrétien. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Peinado, Laura. 2013. La virgen de la leche. Revista Digital de Iconografía Medieval 5: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Miri. 2009. Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadó, Sebastián. 2006. Interpreting the Altarpiece of Saint Bernard: Templar Liturgy and Conquest in 13th Century Majorca. Iconografía V: 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Mariana, Manuel. 2004. Un códice del monasterio de Santa Maria de Sandoval: Los sermones de San Bernardo. In Escritos dedicados a José Mariá Fernández Catón. Caja España de Inversiones: Archivo Histórico Diocesano, León: Centro de Estudios e Investigación “San Isidoro”, vol. 2, pp. 1361–74. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Maroto, Pilar. 2006. “Serra, Jaume” Fundación Amigos del Museo del Prado. Prado Museum Encyclopedia Entry. Available online: https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/artista/serra-jaume/a229f862-9b02-4e77-9900-18436e5905df?searchMeta=serra%20jaume (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Thompson, Stith. 1955–1958. Motif-Index of Folk-Literature. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey, Lesley. 2008. The Serpent and the Rose: The Immaculate Conception and Hispanic Poetry in the Late Medieval Period. Brill: Leiden. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz Leão, Angela. 2007. Cantigas de Santa María de Afonso I, o sábio. São Paulo: Veredas & Cenários, Linear B Gráfica. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez Sainz, Julio. 2008. Propaganda y difamación: Alfonso Martínez de Toledo, el linaje de los Luna y el arzobispo de Toledo. Romance Philology 62: 137–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Marina. 1976. Alone of All Her Sex. The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guardiola-Griffiths, C.M. Nursing Enlightenment and a Grudge—Reinventing the Medieval Virgin’s Benevolent Breasts. Religions 2022, 13, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040326

Guardiola-Griffiths CM. Nursing Enlightenment and a Grudge—Reinventing the Medieval Virgin’s Benevolent Breasts. Religions. 2022; 13(4):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040326

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuardiola-Griffiths, Cristina M. 2022. "Nursing Enlightenment and a Grudge—Reinventing the Medieval Virgin’s Benevolent Breasts" Religions 13, no. 4: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040326

APA StyleGuardiola-Griffiths, C. M. (2022). Nursing Enlightenment and a Grudge—Reinventing the Medieval Virgin’s Benevolent Breasts. Religions, 13(4), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040326