Abstract

The zhuiniu 椎牛 ritual is one of the most elaborate of the Miao people of western Hunan, China. Zhuiniu means “kill the buffalo with a spear” and traces its origins to the worship of spirits and natural elements. Sponsored by a family to repay the spirits, the ritual was a village-wide event that culminated with the sacrifice of a water buffalo and a community celebration. The zhuiniu, estimated to be several thousand years old, is rapidly vanishing from cultural memory. In July and August of 2018, six master badai-spiritual specialists of the Miao—were gathered in La Yi 腊乙, a village in the Wuling Mountain by the cultural bureau of the Xiangxi Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hunan Province to reenact and document the ritual. Using performance ethnography as research methodology, the author employs on-site observations, interviews, field notes, audio, and video to document the reenactment and describe its significance in the words of its practitioners. This essay argues that the zhuiniu has no definitive expression but is an adaptative and interpretative cultural narrative adjusting to circumstances and practice. The ritual exists today as it had historically, in many and varied expressions and interpretations shaped by local need, geography, and subject to the vagaries to orally transmitted forms of practice. Although fragmentary in performance expression and interpretation, the zhuiniu ritual narrative serves as a mythologically-based script that organizes a series of dramatic events that invites community awareness and interaction. In so doing, this sacred ritual has sustained its importance in conveying, embodying, and encoding a spiritual, social, and cultural record of Miao cosmology, culture, and history. Performatively conveyed—using song, music, costumes, dance and movement, props, and set pieces—the zhuiniu has been efficiently and sensorially reimagined in order to reiterate and reaffirm cultural knowledge. With rural modernization, dissolution of cultural context and need, and the aging of its practitioners, the traditional role of the zhuiniu is now in question.

1. Contexts

In late July 2018, in the village of La Yi 腊乙, deep in the Wuling Mountains of the Xiangxi Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hunan Province Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Hunan, China, six Miao badai gathered to enact the zhuiniu 椎牛 ritual. The ritual, one of their most complex and sacred, culminates in the sacrifice of a water buffalo and is considered the penultimate offering to the gods. Once commonly practiced, it is today quickly fading from cultural memory. Orally transmitted for hundreds of years, the ritual and traditional narratives it encodes and reaffirms have proven to be no match against the prevailing forces of modernization, urban migrations, and the shift to a cash economy.1

Massive commercial and aestheticized versions of the ritual have been governmentally sponsored to stimulate the local economy, create jobs, and stem migrations to crowded industrial cities. Museums and various Miao cultural heritage parks have been developed to draw domestic tourists to the region, employing hundreds of Miao dancers, musicians, and artisans (Figure 1). Theatricalized badai shows worthy of Las Vegas are what is presented. A large-scale zhuiniu ritual, which included a sacrifice, was part of the local government’s tourism and employment initiatives. These initiatives were shaped as sensationalized entertainment yet careful to downplay “superstition” or ethnic identity, two issues the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has deemed anathema to its efforts to modernize and unify the nation under party rule.

Figure 1.

A theatricalized performance depicting Badai. Created and presented by actors for tourists and without any spiritual or ritual significance. Shanjiang Miao Tourist Village in Fenghuang County. 2018. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

Annual Miao festivals are a central component of the region’s widely promoted tourism attractions. All festivals are organized and overseen by government offices or representatives, from elected village committees for the village-based events to prefectural or provincial cultural affairs bureaus for large-scale parades and performances. Ethnic tourism, cultural heritage preservation, and rural development intersect in the state, provincial, and prefectural-level programs for the region and play a hyper-visible role in evidencing the projected beneficence and desired successes of national, ethnic policies and agendas(Chio 2019, p. 541).

The most recent theatricalized tourist rendering of the zhuiniu ritual in impoverished Fenghuang County failed to sustain interest or profitability despite best efforts. Heavy rains, rising costs, and poor attendance the previous years forced the cancelation of the event in 2018 and 2019, with the pandemic indefinitely halting future plans.

Knowing my interest in the ritual, Ma Mei, the director of Xiangxi Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hunan Province Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hunan Province Cultural Ministry and longtime research collaborator, organized a gathering of six respected badai in her home village of La Yi. A five-day re-enactment and documentation project of the zhuiniu ritual was prompted by the rapidly transforming and threatened ritual.2 The gathering of the six badai was unprecedented, serving as an ad hoc summit to discuss, pool, and exchange knowledge through the step-by-step re-enactment of the zhuiniu ritual.

Each step of the ritual was re-enacted, explained, and discussed to identify each action’s details, meaning, and significance. What emerged, and what this paper documents, was a unique scholarly opportunity offering a vivid and considered examination of a ritual from the perspective of its practitioners. Extensive discussions, documentation, and interviews allowed for a thorough examination of the ritual, Miao culture, and badai practice.

Badai practice is orally transmitted, with practitioners adhering to the dictates of their training. For the most part, badai work in isolation or with similarly trained badai. To openly share their ways of working and understanding of the zhuiniu, its meaning, mythology, and importance were revelatory. As diverse understandings emerged, so too did a cosmological narrative of Miao culture that the ritual contained and conveyed. The zhuiniu is essentially an immersive sensory retelling of Miao history, values, beliefs, and society. The zhuiniu is a medium and embodied cultural text that performed and encoded the Miao way of being in and with the world. The zhuiniu has survived to this day by adapting and adjusting. How far it will continue before it passes into history remains to be seen. This paper is a record of an event occurring from 26 July to 1 August 2018.

2. Miao Spiritual Practice

Miao spiritual practices are comprised of animism, ancestor worship, and characteristics common to shamanic practice. “The belief in this unity of nature, spirits and human being makes them very dependent, emotionally and psychologically, on their land. It also points to an internal mechanism of a defensive landscape and a symbolic boundary that resists the outsiders’ interference” (Wang 2011, p. 122).

Animal sacrifices and other forms of propitiation are central to these practices. Ritual experts known as badai are the Miao tradition keepers. Badai are formally trained in ritual performance, chants, animal sacrifice, and the making of scared objects. The badai engage in various practices, among them healing, exorcism, thanksgiving, and life-cycle rituals. Their spiritual role is complemented by the xianniang, who use trance and serve as spirit mediums. The third type of Miao spiritual practitioner works surreptitiously and sorcerer-like, using so-called gu sorcery in which they control others through harm inflected by poisons gleaned from insects (Schein 2000, pp. 53–54).

Each village has a Badai, often more than one, serving their community’s spiritual and ritual needs. The position adheres to traditional practice but is shaped to the abilities and personality of the individual badai. In addition to their spiritual role, many badai are also herbalists, fortunetellers, and healers. Being a badai is a calling transferred from father to son. On rare occasions, those not of a lineage line may become badai if they show a spiritual inclination and are taken on as a student by a master badai. The training is extensive and can take many years without guaranteeing an apprentice becoming accepted as a master.

The term badai encapsulates their role: “ba” means father and master, “dai” means the offspring, meaning they are the ones the pass the culture on with a sacred charge.

To keep alive and develop the invisible aspect of the Miao culture, ritual, and society is the duty of the badai. The Miao developed rituals for all functions: physical, political, artistic, mythological, literature and poetry, ritual, social organization, and relationships. Anything and everything to heal and balance their community and carry out the ancestors’ original culture. Badai culture is the encyclopedia of the Miao people(S. Shi 2016).

Badai are male. However, there are rare instances of women, the daughters of a master badai, becoming badai. Female badai are also xianniang (spirit mediums) 仙娘 and are also referred to as zimei 紫梅; they are aligned, but separate, in the spiritual practice of the badai. Most commonly, xianniang are female; unlike the badai, their primary cultural function is to enter a state of trance and access a parallel spiritual reality, often channeling family ancestors to enable a dialogue with their living descendants. Male mediums are generally known as xianshi 仙師. (Katz 2022, p. 15) and serve a similar role and relationship with badai.3 In their role, they confer with ancestors to identify the source of sickness in the family or the spirits4 that haunt, guide, or protect the family. The xianniang is consulted by the badai for the setting of ritual dates. “The xianniang is the female energy and the badai the male, serving as a yin-yang for the balance and well-being of the community. The Badai is the male energy” (S. Shi 2016).

But unlike the zimei, who can include women, the badui spirit officials must be male. Their title and authority are inherited through male filial lineage (father to son, or father-in-law to son-in-law). As spirit officials, they have a superior status compared to zimei practitioners. During rituals, the badui actually controls his familiar spirits and is not possessed by them. Moreover, the badui beat drums and wear red gowns during the performance. Therefore, I conclude that the badui spirit officials are shamans, in contrast to the zimei mediums. Spirits may reveal their will and speak to worshippers through the zimei, who have been selected for communicating with spirits for humans. During rituals, the zimei are possessed by spirits, and they function as mediators between yangjian, the living world and yinjian, the spiritual world(H. Wu 2010, p. 34).

All the badai I interviewed adamantly denied entering a state of trance, an ability that is central and classically defines the shaman’s function worldwide. The relationship of the badai to their community is comparable to that of a classically defined shaman in every function except the use of trance to communicate and mediate the material and spiritual worlds. The badai is unique and best described as a spirit mediator or officiator of forms. Rather than entering a state of trance to access the spirit realm, the badai and all their actions, settings, and props serve to unlock what can be described as a code. The badai is the master of forms, and it is when enacting a sequence of performative codes that they open, access, and communicate with the spirit realm. Their rituals are best understood as dramatic narratives, theatrically expressed, that reference, reiterate, and reaffirm the Miao worldview which is held and revealed by way of ritual forms and actions. In this way, ritual serves as a reiteration and reaffirmation of material and spirit world interaction and order.

In January 2016, I interviewed Shi Shougui, a badai master and descendent of thirty-two generations of badai and master in three different schools of badai practice. A man in his 60s, he is, unlike most badai, literate and educated. In addition to being a recognized and sought-after practitioner, the indefatigable Shi has devoted his life to archiving badai culture and Miao history. He is the author of several books, and we met in his self-financed museum and library in the village of Dadongchong Village, Dongmaku Township, where he explained how the badai evolved with the needs of the Miao people. The badai can trace its origins and influences from ancient Tibetan and Chinese shamanism, which serves as the “Root, spirit, energy and inheritance of the Miao people” (S. Shi 2016).

The badai draw upon many traditions and apply a wide variety of time-tested and culturally codified tools—actions, gestures, movements, dance, music, settings, ritual and narrative sequences, divination, song, chant, objects, and animal sacrifice—to open pathways to the spirit world. Their elaborate system of hand gestures, for instance, is used to “open” passageways to a parallel world and to call up and communicate with the gods and spirits (S. Shi 2016).

The Miao zhuiniu has a close correspondence with the ritual practices of other cultures from Southeast China.

[…] in both the structure of the ritual sequence and in terms of how the buffalo is handled, are particularly significant. […] The rite is preceded by various preparations and begins with the invocation and invitation of the deities and ancestral spirits. Then follows the sacrifice of the buffalo, and the division of the buffalo body into a number of portions, often corresponding to the number of either tutelary deities of the locality or of ancestral spirits. Finally, there is a feast in which the entire community, however constituted, takes part(Holm 2003, p. 214).

The badai I have interviewed over the years uniformly agree that the mastery of ritual forms enables them to communicate with the spirits. They see their role as functional and pragmatic, addressing spiritual needs through the material world.

From the very beginning of the world, we need the badai as a medium between the spirits, gods and human beings to communicate and help us when gods have problems with people or do something harmful to the people. You need the badai to heal the problems. If human beings do something wrong with the environment, the natural world, they need the badai to ask the gods to help. They hold the tradition and are responsible for learning everything from their teachers. They have the responsibility to do everything, to memorize everything. Only after they have memorized all the rituals, the songs of their master and teacher, are they permitted to practice rituals independently(Tian 2018b).

My fieldwork with various indigenous groups—the Yup’ik and Athabaskan of Alaska, the !Xuu and Khwe Bushmen of the Kalahari and the Sakha of Siberia, among others—suggests that the deep structure of badai culture is Cosmo-centric. For the Miao, the world is animistic, conscious, and dynamic, with

All things having souls […] natural phenomena and ancestors were given supernatural power […] natural phenomenon include ancestors, forefathers, five-grain ghosts, mountain, river, stone, tree, wind and thunder ghosts(L. Wu 2017, pp. 80–81).

The initiate becomes a practicing badai after extensive training and passing through a series of skill and ability tests. Once the initiate is deemed ready, master badai conduct an examination; if satisfied, the initiate is presented to the village and recognized as a legitimate practitioner. The process of training and certifying a new badai can vary widely, and in addition to recognition by the presiding badai master, the village must accept the initiate. The announcement of a new badai is considered a blessing for the village. Badai Wu Xiankun from the village Niuyan explains:

My close master was my grandfather, who taught me skills, singing different songs, reciting in different languages and sacred poems and fighting. Not physical fighting, fighting ghosts and evil. This is what you learn from your close master. There must be four different masters to receive and teach you. These four masters taught me special skills, hand gestures, ritual props and sacred objects, making ritual decorations, Nuo masks, and different ceremonies. These masters were not from my school. During the training, I had to prove I was a good person, and people asked for help, that I could help them, be equal and generous, and do no evil. When my close master said I was qualified and ready, I had to be approved by all the villagers and went to each house asking for approval. There were examinations and demonstrations on a special day, and I showed myself in public at the market. This special day is called Qianjie, the day I prove to all the villagers to be authentically a real master. That is a special ceremony for a would-be Badai to become a real badai, and there must be five masters to approve and decide(Z. Wu 2015).

3. Six Badai

Each of the six badai gathered in La Yi village had varying knowledge of the zhuiniu ritual, the narrative sequence of events, and the spiritual process of altar settings, objects, meaning, and mythology. The zhuiniu was traditionally practiced by badaixiong (Miao tradition), but through the years, many badaizha (Chinese tradition) elements were interpolated into the ritual.5 This is partly due to the dwindling and aging number of badaixiong and the appropriation and exchange between practices that were once distinct.

The La Yi reenactment project also served as a skill and knowledge exchange with badai learning from one another and with younger badai benefiting from elders. Only two of the six badai were badaixiong; they were 72 and 85 years old. Given the vagaries of orally transmitted ritual traditions, each knew parts of the ritual with variations. There was never a definitive ritual but rather a composite derived through collaborative agreement (Ma 2018a). The objective of the unprecedented gathering was to produce a written record of the zhuiniu ritual and a documentary film. This essay is offered in tribute to the life and efforts of the participating badai and Miao people.

The zhuiniu ritual varies from region to region and is in a constant state of transformation.6 This is so for a few reasons: (1) it is orally transmitted and subject to the vagaries of memory and transference; (2) being sacred knowledge, it must be kept secret; (3) government suppression and persecution of Miao “superstitious” practices during the Cultural Revolution disrupted generational transmission and disrupted practice; (4) modernization and economic migrations have upended traditional village life, profoundly altering Miao society and cultural transmission; (5) many badai are willfully illiterate, preferring to remain closer to the immediacy of the world unfiltered by written words; (6) it has been increasingly difficult for the ritual to obtain community effort and interest; (7) the ritual is cost- and time-intensive; and (8) when combined with the distractions and economic pressures of modernization, it is challenging to organize. The world has evolved beyond the need and ability to enact the ritual (Ma 2018b; X. Wu 1990, p. 104)

The badai and zhuiniu ritual traditions are dying. “Few people practice these rituals because people believe more and more in modern medicine and technology. If they have problems, they go to the hospital, and some people may not know their traditional healing practices” (Tian 2018c).

The last time badai Tian, at eighty-five years old, the eldest of the gathering, conducted the ritual was in 2012. As a badai, he has only conducted two and assisted in three zhuiniu rituals. For intricate rituals such as the zhuiniu, it is not uncommon to have several badai facilitating, a master and two to four assistants. The Huan Nuoyuan thanksgiving rituals I documented (in 2015 and 2016) (Riccio 2019, p. 85) had three and seven badai, respectively. Some badai never reach master status and remain assistants; others are in training and participate under the tutelage of a master badai.

Badai are broadly categorized as either badaizha 巴代扎 or badaixiong 巴代雄. Badaizha, the most practiced tradition, is the “mixed” or “Chinese style” because it is performed in Mandarin and borrows heavily from the Han, Buddhist, and Daoist ritual traditions. All sacred badaizha books and writings, including letters written to the spirits, are in Mandarin (Z. Wu 2015). Red robes distinguish badaizha and their crown-like headpieces, made of leather and called the san qing fa guan 三清法冠 (Figure 2), that depict Daoist and Buddhist deities; the performances use “both local dialect and standard Han Chinese” (Katz 2017, p. 158). “In Miao culture, almost all gods and ghosts do not have facial design or detail, so they have been borrowed from Buddhism and Taoism” (Yang 2018a).

Figure 2.

Badai Shi Shougui, wearing a san qing fa guan with twelve Daoist and Buddhist gods depicted, marking his status as a master badai. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

In the earliest times the Chinese and the Miao were one family. The Miao was the older, the more powerful, and the more respected brother, and the Chinese was the younger […] But in the centuries that followed the decedents of the two brothers grew apart and forgot their common ancestry, and so the Chinese have forgotten it all together. Moreover, the Chinese descendants have grown more and more powerful and numerous, so that the Miao are now the younger and weaker brothers, the Chinese are the older and stronger brothers.(Graham 1955, p. 27).

The practice and regalia worn by badaizha bear many similarities with those of other Chinese ethnic groups such as the Tujia, Dong, Yao, and Jingpo. All of these are similarly borrowed from the Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist traditions.7 They were

[…] quite routine on the eighteenth-century frontier, where many locals had taken to the Manchu-style queue or Han Chinese-style clothing as a mark of status […] much later these Miao were to adopt religious practices that they called guest rituals and practice them alongside their ‘Miao’ ritual(Ling and Rui in Sutton 2003, p. 125).

In addition to their spiritual practice, it is essential to recognize the badaizha as a multi-disciplinary artist. Their training and work required the making of props and settings, singing and chanting, storytelling, drama, dancing, performance, musicianship, and drawing (writing notes, calligraphy, and images to the spirits).

The other Miao badai tradition is badaixiong, distinguished by white, blue, or black robes and a traditional cloth head wrap. Badaixiong is referred to as the “Miao tradition.” Unlike the Zha School, badaixiong use the Miao language only to tell the stories of the Miao ancestors. Although Miao, most badaizha either do not know the Miao language or have an imperfect knowledge of it.

Those ancient stories cannot be told because they do not know the Miao language. Each story holds a ritual. The difference between badaizha and badaixiong is language. Badaixiong uses the Miao language, and badaizha uses the Chinese language. Badaixiong is for language. Badaizha for military things, the generals and soldiers. Badaixiong are officials and storytellers(Tian 2018b).

The badaizha and badaixiong traditions both recognize thirty-six houses of gods. The badaixiong conduct rituals for sixteen houses of god, the Zha for twenty houses of god. Each house represents a god, which constitutes a unit that is in turn divided into thirty-six different categories of different gods. There are many thousands of categories of gods (Tian 2018c). “Gods” for the badaizha and badaixiong are legendary, mythological, or spiritual figures associated with an archetypal role, task, or need. “Spirits” are more vaguely defined as ancestral (familial, community, or cultural) or as beings that are a form created by a feeling or emotion and are generally negative or evil. If, for instance, a neighbor harbors ill will, it is manifested as a harmful spirit that may inhabit a family’s house and instigate harm or mischief. Like other animist traditions, a thought, feeling, or word has agency, can become a presence, and can accumulate power to affect the physical, mental, or emotional health and well-being of a person or family. “Ghost” refers to lost spirits, often of an unknown origin.

Within the broadly defined badaizha and badaixiong traditions are several practice variations defined by linage lines or regions. The overwhelming majority of badai are Zha; however, those initiated and recognized as practitioners are of both the Zha and Xiong schools. With fewer men interested in becoming badai, both schools are challenged and are aging into obsolescence. Many generational inheritors have opted not to continue their hereditary lines. Badaixiong are critically endangered because of the reliance on the Miao language, which has declined among those 40 years old and younger.

Of the six badai attending the zhuiniu ritual, four were exclusively badaizha: Hong Shuyang, Yang Guangquan, Wu Zhengnian, and Yan Zaiwen. One badai practiced both Zha and Xiong: Shi Changwu. One badai exclusively practiced Xiong: Tian Zhanliang.

Badai Shi Changwu was the only badai trained in both traditions; he was most familiar with the zhuiniu ritual and grew into the role of ritual organizer. The respected seventy-two-year-old was trained in both traditions by his father and grandfather beginning at the age of five and became recognized as a badai in his teens. He is articulate and personable and from a long line of badai extending back many generations. “During the Cultural Revolution, I continued to practice in secret because there was much sickness” (C. Shi 2018b).

4. The Miao and Han

The Miao are dispersed over a large geographical area in south-central China, with significant numbers in the Hunan and Guizhou provinces. The Miao are not homogenous, which gives rise to variations in ritual and cultural practice. The Miao badai culture is best understood as the foundation of cultural themes, myths, customs, and social practices that share similarities and variations. Variance is due to the centrality of the Miao village in determining the social, cultural, and economic organization and expression and, in turn, spiritual and ritual practice. Many Miao villages remain isolated and autonomous entities shaped by the geography and historical founding of the village. The Miao are pragmatic functionalists who identify and share a culture wellspring. Each village is specific and unique to its history, location, and geography.

The traditional bedrock of Miao society is the cunzhai 村寨 (village). The village is the most critical form of Xiangxi Miao social organization, for it is not only a natural grouping but also an economic community. Some villages have dozens of households; others have hundreds. The affiliations within a village are not organized by blood lineage but rather by clan surnames. People living in a village are treated as brothers and sisters(H. Wu 2010, p. 8).

The Miao migrated southward from central China beginning 2000 years ago and increased in waves to the Xiangxi region six hundred years ago (Diamond 2021 https://www.encyclopedia.com/places/asia/chinese-political-geography/miao, accessed on 3 June 2021). The Miao, pushed by advancing Han seeking land and opportunities, could not settle until reaching the rugged Wuling Mountains. The region was undesirable, challenging, and isolated, which provided a respite from the advancing Han. They brought their subsistence, agriculturalist, and herding lifestyle, which required a community effort to survive.

Villages are best understood as micro-units of Miao culture, many of which remain organized by a clan or group of families. Each village worships different animals and shapes their “belief and customs to maintain best ecological balance and biodiversity” (L. Wu 2017, p. 82).

Unmolested isolation lasted for three hundred years, and during this time, the village as a social, cultural, and economic unit evolved. The badai became a significant spiritual, cultural, and civic leader for their community.

The Miao people were on the run and defeated. To protect themselves, the badai became a significant conduit of cultural transmission. The Miao people were illiterate, and the badai had to carry out the physical manifesting, making visible and felt the Miao culture. We had to hide our culture from the Han. The Miao developed two faces, a surface face and something behind and beneath. The badai is the one who reveals the two features, the seen and behind”(S. Shi 2016).

Today, isolated villages remain characteristic of the Miao. Cities like Jishou and Fenghuang, which were founded to serve as military, trading, and political centers, have, to this day, Han-majority populations. The Miao essentially remain village-based as extended families or as a grouping of families generationally cooperating to eke out their existence. They can best be understood as subsistence social units organized to sustain a limited capacity of people who survive as farmers, herders, and gatherers who occasionally hunt and trap.

Historically, each village identified an auspicious tree, which they saw as a sign and called “founder.” “The villagers regard it as the ‘divine tree’ of understanding, which can protect the happiness and well-being of the people in the village and is a spiritual sustenance” (Chen and Bao 2021, p. 102). Such large and older trees (generally maple) are still found on the road just outside a village. “Great trees are the symbol of life, death, marriage, ancestors, and descendants. They symbolize almost all aspects of life and reproductive continuity” (Wang 2011, p. 129). They are considered the “guiding spirit” of the village and revered as an ancestor surrounded by stone altars and worshiped (S. Shi 2016). During my field research (2001–2018), I have encountered a wide range of village identities. Each is recognized and organized by what they grow, the geography, economy, and climate, which directly influences dialects and cultural practices.8 “Human activities and material environment together constitute the overall landscape of Miao villages in Qiandongnan and become the symbol of Miao identity” (Chen and Bao 2021, p. 103).9

The cultural complexity of the Miao was shaped in no small part by their historical interactions with the Han, who initially expanded into present-day Miao areas seeking land in the 17th century. Early encounters went quickly from interactions to suppression, war, and colonization.

Governmental mandates imposed on the Miao and other ethnic groups have made for an uneasy relationship with the Han-dominated central government. There were Miao rebellions in 1795–1806 and 1854–1874, with uprisings occurring in 1936 and 1942 (Katz 2017, p. 133) and resistance to governmental policies occurring into the 1950s. All rebellions were about land and control. The Miao were quelled and forced to accept the Qing imperial rule and its inheritors, the Republic of China and then the People’s Republic of China.

Republican leader Sun Yat-sen prescribed: ‘We must facilitate the dying out of all names of individual people inhabiting China, i.e., Manchus, Tibetan, etc.…uniting them in a single cultural and political whole.’ Place names in non-Han areas were renamed in Chinese, and people were encouraged to adopt Han surnames. Miao women had their topknots cut off and their pleated skirts shredded by Republican troops; women in Guizhou recalled having their red headdresses removed and fastened to dogs’ heads. Meanwhile, the opening of roads to minority areas brought cholera and more aggressive tax collection. Han immigration and appropriation of minority lands were supported by the government(Schein 1989, p. 72)

The PRC established autonomous areas for several minority ethnic groups in 1951, purporting “home rule.” During the Cultural Revolution, the Miao were persecuted for expressing their “superstitious” and “harmful” customs, which sent many badai underground and had a chilling effect on cultural expression.

There were many hardships during the communist takeover and the Cultural Revolution; the Miao people ate grass, roots, and tree bark. Those who believed in ghosts and spirits were persecuted. My family’s ritual materials were destroyed. Others secretly hid anything suggesting they were badai. My grandfather and father were persecuted in the 1940s and 1970s and called professionals of superstition and shamed by the community. I trained at the risk of political and personal life. It was a difficult time, and I would learn at night because to become a badai requires person-to-person teaching. It is an apprenticeship, learning by doing. Now the climate has changed and is more accepting. But certain kinds of persecution continue. Four books of mine were published—but I was the second author, the government assigned another writer as a censor. My other materials were not allowed to be published(S. Shi 2016).

The single most destructive force affecting Miao culture and its spiritual practice was the Cultural Revolution, an event from which it may never recover. Rural development and anti-poverty programs have gone far to quell ethnic tensions, but resentments and distrust remain. Ultimately, time and the progression of modern technology, social media, tourism, and a burgeoning cash economy transformed Miao culture, bringing it closer to the Chinese government’s values and objectives.

The influx of Han settlers into the Miao region in the 18th and 19th centuries initiated an informal cultural exchange, resulting in an adjustment of Miao spiritual practice. In particular, the badai culture interpolated Han spiritual practices, mythology, cosmology, and deities. Most prominent was the introduction of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, as well as the Yijing or Book of Changes,10 which was adapted and interpolated into badai practice in the Fenghuang area. The Miao adapted regalia, ritual objects, deities, and organization, which were highly developed and characteristic of the Han.

Miao cosmology is very similar to Chinese cosmology. Chinese folk religion divides the cosmos into three interconnected realms: heaven, the world of the living, and the underworld. Here, heaven is equal to the upper realm; the world of the living is equal to earth, and the underground is equal to the spirit world. Indeed, in most of the eastern and southeast Asian areas, this three-part view of the universe is common(H. Wu 2010, p. 35).

In creating a syncretic spiritual belief, the Miao did what so many other world cultures have done. They responded to a changing social and political condition through spiritual adaptation. Their syncretic spirituality evolved in a manner that persists to this day and can be viewed as a theatrically performed expression of their historical journey and evolution. Syncretic adaptation was key to the Miao ability to process humiliation and subjugation by providing a means to assert agency. It was a means to take ownership, transform, empower, and mitigate the trauma of defeat. This assertion will vividly reveal itself in reference to calling on martial implements, such as swords and flags, and protectors in the form of generals and soldiers to do battle on their behalf—all of whom are of Han origin.

“Interestingly, some Han settlers adopted Miao cultural lifestyles during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the changing frontier of western Hunan, the main flow of influence can go either direction” (Sutton 2003, p. 109). The Han settlers were taken by the Miao lifestyle and welcomed into the Miao community. Today, several hundred years after Han settlers arrived, certain villages are known as “Han Miao” in recognition of their historical origins, acculturation, and subsequent Miao “otherness” (Cheung 2012, p. 152).

The six badai gathered to re-create the zhuiniu ritual exemplified the rich, varied, and syncretic Miao culture, making it difficult to assess and document the ritual. “They are not culturally homogenous, and the differences between local Miao cultures are often as great as between Miao and non-Miao neighbors” (Diamond 1996, p. 473).

5. Zhuinui Overview

Unlike the one-day government-sponsored tourist rendering of the zhuiniu ritual, the traditional ritual was an elaborate, multi-faceted village-wide event requiring months of preparation and organization, which financially obligated the sponsoring family. Although a family-initiated event, given the extended family socialization of traditional villages, the participation of the entire community was an understood given.

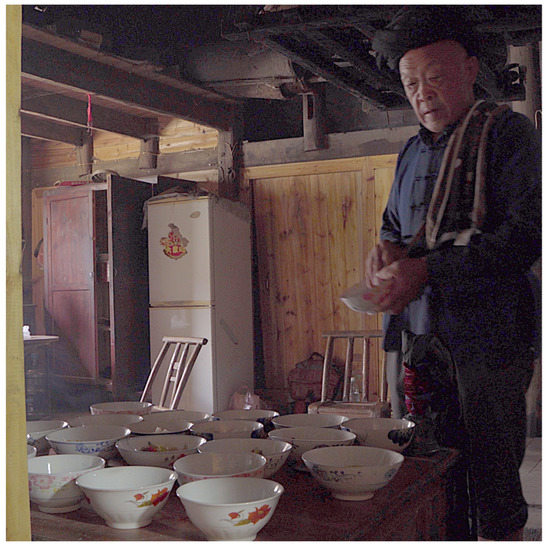

When I arrived at La Yi village, the six badai were gathered, discussing the sequence of events to begin the ritual the following day. They had just finished a three-day fast with a meal of vegetables and rice. “To begin, we must have no blood in our body and be pure for the gods. We must not even swat a mosquito, which can draw blood. You must instead shake it off” (Yang 2018a).

They were seated around a central open pit with a low fire burning. Ma Mei’s brother’s rough-hewn, barn-like home was a high, open structure of wood darkened by the smoke from the fire pit, used for warmth and gathering. A wood-fed “stove” was in the adjacent kitchen area. The stone and concrete floor was wide and open to accommodate the drying, sorting, and storage of harvested items. Large rice and grain sacks were piled next to farm tools in the corners. The ceiling was hung with hundreds of ears of corn drying. Nearby was a ladder to a sleeping loft. The sounds of pigs, chickens, and goats could be heard from the interconnected barn area. The house was typical of rural houses throughout the region. The zhuiniu would occur in the adjacent house belonging to the parents, which was similarly arranged and larger.

With me were Wheeler Sparks, my assistant and videographer; Megan Evans, my former student and now a professor at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand; Yang Bingfeng, a former Ph.D. student of mine and translator; and Peng Jinquan, a dear friend, filmmaker, and translator, and activist for Miao cultural preservation. As the six badai spoke, a silent flat-screen television flashed a sporting event in the background. Ma Mei, the event organizer, a government official and Miao scholar and cultural activist, welcomed us.

Such a gathering was unprecedented. Badai generally work alone or with those from their school.11 All six badai were known and respected masters. Except for badai Tian, who was from the hosting La Yi village, the others were from nearby villages. Ma Mei had chosen well.12

The excitement of the six badai was palpable.

They enjoy meeting and talking with the other badai and being hosted. There is food, and people take care of them, and they are paid. If they, do it quickly, it will end quickly, and they will be back home. For them, this is a great pleasure”(Peng 2018a).

None had met before but knew of the others by name and reputation. Each day, during and after dinner, the badai spent hours going over the details for the following day. Although the reconstruction of the zhuiniu was why they were gathered, their discussions were often opportunities to reflect, exchange, compare, and reaffirm their tradition and lives as badai. Used to conducting all-night rituals, they talked well into the night about a range of issues revealing their roles as spiritual and cultural guides.

These days are an extraordinary situation. We come from different schools, but there is cooperation. Usually, only badai from the same school work together. The badai knows those in his line, the same system, only those masters. We are not familiar with their practice and learning different ways(C. Shi 2018b).

6. Preparation

Traditionally the zhuiniu ritual begins with the family’s announcement of intent at the beginning of the Chinese lunar New Year, usually in January or February. Before that, the family consulted a xianniang (spirit medium) who enters into a state of trance to speak to the family ancestors and determine whether it is an auspicious time for the ritual. “Ancestors are particularly revered and are worshipped as though they possessed god-like qualities. Some Miao believe there are spirits everywhere” (Wang 2011, p. 119).

Once approved, a fortuneteller—a badai with fortunetelling ability or a specialist—is then consulted. According to the Chinese calendar, fortunetelling is based on the birthday of the head of the sponsoring family (Hong 2018a). Using the Yijing, the five essential elements of the universe are consulted: fire, water, metal, wood, and earth. The days for the ritual are set, as is the day to purchase the water buffalo and the day it should be sacrificed. Then the preparations begin (Yang 2018c).

The zhuiniu is considered the highest way to give thanks to the gods. The reasons for having a family to sponsor the ritual include: (1) someone in the family is seriously wounded or ill, (2) the family have experienced a disaster or some great bad luck (e.g., house burnt down), (3) having a problem with children birthing or no children, (4) giving thanks for a great fortune bestowed on the family, and (5) the need to gather money for the family (Hong 2018b). According to badai Tian and Shi, the last reason was most prominent. Other, smaller and less expensive rituals, such as the Huan Nuoyuan, addressed similar issues.

To sponsor a zhuiniu ritual is expensive, often requiring the sponsoring family to make long-term financial arrangements, often borrowing money. Badai Shi estimated the total cost to be CNY 19,500.00 to 22,500.00 (approximately USD 3000.00–3500.00), which for those living in poverty-blighted rural areas can equal their income for six months (Ma 2018b).

Most rural Miao presently live at or below poverty levels, eking out a subsistence living. Since my first visit to the region in 2001, the PRC has focused a great deal of attention and funding on improving roads, education, and employment opportunities. Like others living with generational poverty, it is a continuing process with the Miao, looking for opportunities to better their lot. Money and wealth become preoccupations with gambling, investing, and lotteries, fueled by hope, these being the few opportunities. For the Miao seeking to better their economic standing, the zhuiniu—like divination, astrology, belief, religion, and luck—was an expression of hope and aspiration.

The zhuiniu offered an opportunity to interact with the “god of the treasury” and was viewed as a proactive way to manage the family’s money and wealth. For the Miao, the gods, ancestors, and spirits are responsible for the wealth and well-being of the family. Reciprocity and interaction with the spirit world was the conceptual context anchoring the cosmological narrative the zhuiniu articulated. “The family sponsoring the water buffalo killing must be very rich or want to become rich to maintain their wealth by this ritual. People will ask you, ‘How did you become rich?’ And you respond, ‘Because of the gods’” (Yang 2018b).

The La Yi village demonstration of the ritual condensed into five days what traditionally would have taken eight or nine months of preparation and culminating during harvest season (generally on or around a full moon) in September or October of the same year. “In the fall, the meat will be good for a long time. The fall is also when the weather is cooler. Summers in Hunan are notoriously hot and humid. Even today, there is little refrigeration in Miao villages, and meat will become rotten” (Peng 2018c).

7. House Cleaning

With the announcement of intent, an ox is sacrificed according to the badaizha tradition. The badaixiong tradition sacrifices a sheep and a cock (Yang). The ox sacrifice must happen before the house cleaning and is a “payment” to the gods to protect the sponsoring family. “Once you begin the ritual process, the spirits, both good and bad, are awakened (C. Shi 2018a; Yang 2018b).

Water buffalos were traditionally (as is the case today) expensive, requiring the hiring of guards to travel a long distance and carrying money for the purchase. The sacrifice of the ox is also necessary to feed those who will, in traditional times, travel to purchase a water buffalo. Once purchased, the water buffalo was brought back to be fed and groomed until the fall sacrifice. As part of the house cleaning ritual, which occurs in the family’s home, the god of the treasury is called upon to protect the family, the guards (which include family members), and those who travel with money to purchase the water buffalo.

It is important to remind the reader that the circumstances and requirements for the zhuiniu ritual were shaped in an earlier era. It was a time when travel beyond one’s village was fraught with danger, when highwaymen, robbery, and death were real threats, and when evil and hungry spirits played on the imagination of the isolated and poorly educated. The zhuiniu was encoded as a ritual during this era.

The ox sacrifice and house cleaning serves several functions: (1) it announces to the community and the spirits the onset of the zhuiniu and the family’s intent; (2) it is a house cleaning, cleansing the home of evil spirits and preparing for the events to come; (3) it calls upon the god of the treasury to protect the family financially and to assure their ability to fulfill the complete ritual financially and to protect the money sent to purchase the water buffalo; and (4) it calls upon the gods with spirit armies to protect those who will be traveling (Hong 2018b).

The zhuiniu begins, as do all house-located rituals, with the “house cleaning,” a ritual used for various purposes (Peng 2018a).

Agreeing on the house cleaning details, Badai Yang was charged with enactment.

For each segment, a leading master decides what is to be done. It is the one who has the most knowledge of that part. They ask for our experiences, and they determine everything, all the details, including props and movements. They are the master and determine the process and the ritual(C. Shi 2018b).

Badai Yang was the master of the house cleaning ritual, which was required to clear out the evil spirits. Evil spirits are especially fond of doors, corners, windows, and beds to influence those sleeping. Essential to the house cleaning was the liu jin 绺巾 (Figure 3), a ritual device adopted from the Han and “used to sweep ghost and any disaster or weirdness away” (S. Shi 2016). It is a stick (made from the commonly found Chinese fir tree) hung with strips (24, 33, or 36 strips) of richly varied cloth, often embroidered, to represent the various branches of Miao clans. Each strip of cloth is made and contributed by the village households and given to the village Badai to symbolically affirm that he is empowered and protector of the families and village. The badai repays each family with wine or sugar when given the cloth strip. “It is also called the cloth of the dragon or phoenix. It represents the coming of the Han from the north, where dragons from the time of the ancestors. Using it honors the influence of the Han, but when the people see it, they know it is Miao” (S. Shi 2016).

Figure 3.

A liu jin used by badai to sweep away evil spirits. Each cloth was embroidered by families from the village and given to the badai to protect the village. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

If a badai sees an evil form or group of bad spirits walking around the house, a rooster will be sacrificed by a procedure that entails going behind the house cleaning altar with his back to the people. Then he bites the rooster on the neck, killing the rooster, flinging its body over the altar and the heads of the family. This “crossing over the people” is to protect them from evil and bad spirits because the blood of the rooster has magical power” (Yang 2018c). Yang told me he could see the spirits, but not always. When conducting a house cleansing ritual the previous year, an evil spirit reached to take an altar sacrifice. Using his shidao 司刀—a ritual knife used historically as a battle weapon—he fought to take the sacrifice back. Shi recounted that he returned home after a ritual to find a ghost sitting at his feet. The ghost was lonely and had followed him, remaining at his house for several days. During that time, the family living next to him died in a car accident (C. Shi 2018c). Badai Tian related, “When I see them, they are just a shape you cannot see. Clearly, they do not look like a person. I do not tell other people, because they might take it as a curse” (Tian 2018c).

A xianniang, when in a state of trance, is often asked by the badai to identify and locate the evil spirits affecting the family. The xianniang, channeling the family ancestors, names all the evil things present in the house, where they are hiding, and words to attract and kill the demons.

Because we will do the ritual, it is necessary for this cleaning to be done. It is a necessary part of the ritual. The cleaning of the house is required for all the major rituals. It is to prepare the house for all that follows, and the host family must clean all the persons, animals, take baths, and change the mattress’s clothes. Everything must be clean(Yang 2018a).

Badai Yang Guangquan, 56 years old and from Tang Jia village in the adjacent county, was, like the others, a farmer. He descended from four generations of badai and was taught by his father (a badaixiong and badaizha)13. Beginning at 12 to be a badai and healer, not all Badai can heal.

During the day, I studied at school and at night, I learned to be a Badai and began to practice at the age of twenty-five. I have traveled to many places in this province and the next province. I am not a fortuneteller, but I can help villagers choose the dates and the place for marriages and help with funerals. The busiest time of the year is the fourth month of the lunar system. This time of the year, the summer, there is not much to do. If you come other times, you will not find me(Yang 2018a).

Badai Yang had conducted the house cleaning ritual many times that year for several families. The ritual is not specific to the zhuiniu and is often conducted independently with variations by both badaixiong and badaizha. “There is no limitation. The ritual can be done anytime of the year and for many reasons if the family needs it” (Yang 2018a). Generally, pigs or other meat (chicken, goat) are sacrificed to satisfy the spirits. However, the sacrifice of the ox is specific to the zhuiniu “because it is special and more expensive than pigs, sheep or roosters, but the ritual is the same. Usually, house cleanings are one hour, for the zhuiniu, it is much longer, depending on the gods and spirits, they must be made happy” (Yang 2018a).

Yang had never participated in a zhuiniu ritual before. Using his knowledge of housecleaning under the guidance of the badai Shi and Tian, he shaped his experience to the requirements of the zhuiniu. The physical demands of the house cleaning required a younger man to perform it. When asked why the ox sacrifice for the zhuiniu house cleaning, he replied, “It is more treasured that is why the spirits want it. The meat is practical and necessary for their travel to get the water buffalo” (C. Shi 2018b).

The house cleaning ritual made the house into a sacred space to perform the ritual, and strict adherence to detail had to be followed. Form and sequence adherence was essential for efficacy, with patterns, words, and actions considered sacred and necessary for communication with the spirit world.14 The house cleaning that prepares for the zhuiniu moves beyond cleaning and into the calling of the spirits of the five heavens to prepare for the most elaborate and spiritually intensive Miao ritual.

8. Altars and Armies

During the two days before my arrival, the six badai gathered what they needed for the ritual from the nearby fields and forest. The forest surrounding the village is sacred, hosting several spirits, including the “seven fairy daughters”15 and some animal spirits, known as “gold” spirits because of their glistening appearance. In this way, the forest becomes a living and ongoing host of the Miao cosmological narrative. The world is charged with meaning, with the zhuiniu reiterating and reaffirming their worldview.

The ritual items sought in the forest were wild-grown peach tree branches, essential for house cleaning. The peach tree is said to have originated in China and produces a beautiful blossom. Sweet fruit is symbolic of driving out evil spirits.

Two badai were charged with going to the mountains and cutting peach tree branches, which were boiled. This created reddish water used by all six Badai to wash their face and hands, who then rinsed their mouths to protect them from evil spirits and ghosts (Hong 2018c). As the badai are gathering, the family prepares “fast” cakes, rice cakes made with tofu offered in respect to the gods. This is the only food eaten by the family before the ritual.

From here forward, the zhuiniu ritual comes into focus with each subsequent step in the sequence of events leading to the sacrifice of the water buffalo.

On the morning of the house cleaning, all six badai assisted in setting up two altars (also referred to as temples) at the main entrance and room of the house. The larger altar, also known as the “left altar,” was set against the far wall at the house’s interior for the god of the land (Hong 2018a) (Figure 4). The Miao believe that each piece of land has a god, and the land altar is in honor of the overseeing “land god”. Often conflated with the god of the treasury is Caishen 財神, a god personification borrowed from the Chinese.16 The god of the treasury, depicted as corpulent and generous, is evoked to help the host family afford a water buffalo, protect the family from the evil spirits, and help those traveling to buy the water buffalo. Badai Yang, speaking on behalf of the god of the treasury, thanked the host family and, in turn, announced the household’s support of the god of the treasury.

Figure 4.

Badai Yang inviting in the spirits and armies. He dances the hexagon in front of the left altar. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

The left altar was elaborately arranged, hung on three sides with two rows of hanging paper cut to look like fencing and serving as a defense against evil spirits by protecting the altar and creating a sacred space. “You need to go to create this altar in the house, to make a temple to protect the family and to communicate with the god of the treasury” (C. Shi 2018b). On the table were arranged (1) rice cake offerings, (2) a rice bowl with incense, (3) a shidao (a brass knife-like implement with a round handle and dangling metal), (4) a gao (two pieces of bamboo used for divination), and (5) three bowls of peach water, one for each kingdom of heaven.17 The inviting in of the water spirits to make holy water was necessary to establish the presence of the gods. It was essential that protocol be followed and that the guardian spirits be positioned correctly on the altar and given respect and comfort. The last item on the altar was (6) a rolled scroll, the shenxiang juan 神像卷 depicting the spirit army (Yang 2018b).

The second, smaller altar was at the house’s main entrance (Figure 5). This altar was known as the “right” altar to call the “armies” to protect the journey and the ritual. The god that oversaw the armies and this altar was qiaoshi, 桥师 or qiaoshen 桥神, bridge god or bridge master, who facilitates the crossing of distance (Peng 2018a).18 This altar is sparse, arranged prominently with beeswax incense—burning wax wrapped in paper—and it was constantly burnt throughout the house cleaning. Located at the doorway, the altar advances the belief that gods should come and go as they please and travel (like bees) to and from heaven more easily with the beeswax smoke (Peng 2018c).

Figure 5.

Badai Shi Changwu at the right altar in front of the main door to the family’s home. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

Traditionally, this ritual began at midnight. For the La Yi re-enactment, it was conducted mid-day.19

9. Inviting the Gods and Spirits

Next came the introduction of the badai participating in the ritual to the spirits and gods. The introductions were done using a complex system of hand gestures (C. Shi 2018a), which linked ordinary and spirit realities. Hand gestures, numbering in the dozens, serve various functions, most notably communicating with the spirits, mythical animals and soldiers, magical powers, and master badai to assist (J. Shi 2001); the hand gestures were used throughout the ritual. Then, Yang and the other badai changed into their regalia.

Gestures are ways to communicate with the spirits and ancestors. There are many gestures from the ancestors, and they are used for different reasons. Some are used to communicate and move with the spirits. Some gestures are used to hide your body from those evil spirits so they cannot get into you. Sometimes the masters make mistakes with the hand gestures, and the ancestors come and help(Yang 2018a).

The introduction of the Badai and invitation to the spirits was repeated twice to avoid any confusion in communication. Special consideration was given to inviting the god of the “doors and gates” because entrances and thresholds are where evil spirits often linger and hide. The function of the ritual is first to clean out the devils and evil spirits: “some must be driven away, others are locked up,” and then I ask for guidance and protection of the good spirits (Yang 2018a).

Peach water was offered to each of the spirits. To verify their acceptance Yang threw his gao, a palm-sized ritual object typically made of bamboo or wood split in two and thrown as a form of divination. The gao is thrown on the floor midway between the two altars. If the gao lands with both sides down, the spirits have accepted the water and will participate. If both sides land up, it is an absolute refusal. If one up and one down, it is a negotiable refusal. The gao is thrown repeatedly, each time with a vocal request, plead, or persuasion until the offering is accepted. Once accepted, the peach water is offered and poured onto the earth.

Throwing for an agreeable response to multiple questions and wishes required multiple throws of the gao and is considered dialogue and negotiation with the spirits. With discussions taking place and propitiations offered as necessary in the form of chant or an additional offering of “fortune money” or “spirit money,” gold-colored paper (typically 8 × 8 inches square) is burnt and sent to the gods.20 Smoke is considered a pathway to heaven. The money sent to the gods, specifically the god of the treasury, is never a burden but seen as communication, opportunity, and blessing. “Human beings send money to gods so the gods can send back real money—so you give money to gods, and they will give to you. Yin money is sent to the gods, and yang money is sent to the family (Ma 2018b). Spirit money burning occurs throughout the ritual and is an integral part of all Miao rituals. The white paper is symbolically “silver,” and the yellow paper is gold (Peng 2018b).

Negative gao responses provoke the badai to ask if the gods have changed their minds or require more spirit money, rice cakes, further cleaning of evil spirits, or animal sacrifices (Yang 2018a). The gao throwing continues going through a step-by-step checklist of wishes asked of the gods to assure a successful zhuiniu ritual. Daoist rituals inspired the checklist of wishes, and depending on the school of badai practice, were either written (text) or spiritual (visually conveyed via scroll). Yang’s school used the visual scroll form.

The asking of the gods concluded with a rooster sacrifice; its spirit is believed to protect those who travel.

For the sacrifice, the rooster’s mouth is stuffed with rice cakes, and its beak tied with thread to protect the travelers from any bad words. “When they are on their trip to look for a water buffalo, people may say bad things about the journey. Not the local people, but people along the journey. Tying the mouth will protect them from bad words” (C. Shi 2018b).

The ritual proceeds to a more intimate interaction as badai Yang moves with the gods and dances to “open up heaven.”

The horn is blown again for Yuhuang the Jade Emperor, the highest of the gods.21 There are two distinct types of horn blowing. “For the Jade Emperor,” sounds like, Who EE Who EE Who EE and is blown to fulfill the family’s will and respect to the Jade Emperor. The second type is used more generally as an announcement and in various contexts is identified as Laojun in honor of the Daoist god Laozi and sounds like Ho Ye Ho Ye Ho Ye. The blowing of a water buffalo horn serves as an announcement to the heavens that the section is complete.

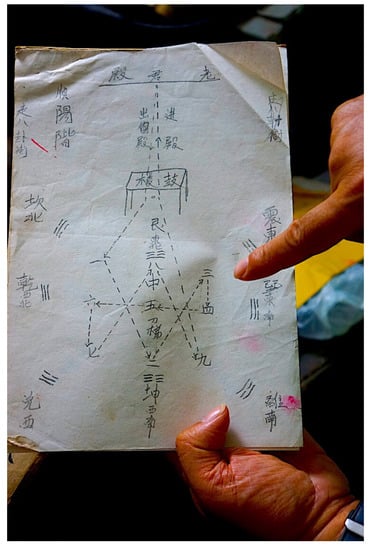

Yang sang and chanted exclusively in Chinese. The dance steps were in nine parts or “states” called the “nine ancient steps.” Based on hexagram readings of the Yijing (Figure 6). With this action, Yang “danced” to evoke the “Kingdoms of Heaven” (Yang 2018b). The function of the dance is twofold: (1) to connect the human world with heaven by way of ritual and (2) to symbolically travel to each kingdom of heaven. The dance steps opened each of the five heavens (one in each of the four directions and one for the center axis), following a dance step pattern unique to each direction and center axis. “Dancing the hexagram” required nine repetitions of step patterns, with each consisting of two steps followed by four steps performed nine times. The dance can be viewed as a danced drama that culminates with a nine-step repetition of an eight-step pattern for the center. The dance step pattern of nine (2 × 4) for each direction and then eight for the center each equaled nine when accounting for each direction and center as one. The dance opens each heaven (Hong 2018c) and retraces the cosmological structure of the Miao worldview.

Figure 6.

A diagram of the Yijing-inspired dance steps that evoke the “Kingdom of Heaven.” (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

The Miao believe that the Yijing originated with the Miao and not with Confucius or Daoism, who came after the Miao were historically established in central China. The Miao maintain that others formalized the Yijing into a written culture and a belief system. When pressed for details, Yang said he did not understand nor was it important to know the reason for the dancing, only that he must strictly adhere to the form to preserve its sacred meaning and open each heaven (Yang 2018c).

While visiting heaven, he encountered eighteen sacred gods and four officials—gods in charge of each specific heaven (Yang 2018c). While traveling to each heaven, Yang verbally invited the gods, ancestral spirits, and badai masters from his school that resided in each heaven. His song and chant declared why he was there and what he needed from each heaven. By so doing, he linked the material world with the cosmological, becoming the embodiment and articulator of the Miao mythic narrative.

His hand gestures, vocalizations, and actions (such as tapping the buffalo horn) varied according to his interaction with the various heavens. Tapping the horn signified the invitation of his school’s ancestral teachers. Once they accepted, Yang persuaded them to eat from the altar table, talked with them, and then released them before he moved on to another heaven.

After visiting the heavens, the spirit army, which resides at the center, was called upon to support the ritual and chase away the devil and evil spirits. “It is the army sent from heaven to help the host family. There are many gods and soldiers in each heaven that gather at the center. There are 99,000 soldiers and horses” to protect those traveling long distances carrying cash to purchase the water buffalo. “This ritual is about what you should do before you go into battle (Yang 2018a). The soldiers are called to protect against three types of bad people, spirits, or gods: (1) enemies of the host family, (2) those who may be friendly but say bad things, and (3) those that could do harmful things. There are three types of evil spirits: (1) natural spirits, like a tree or rock (anything in nature can potentially be an evil spirit), (2) ghosts from unnatural death (murder, accident, or suicide), and (3) those that come from relationships (people or spirits) that fight or kill each other. Evil spirits are always close at hand, with the best protection being working together, respect, and communication. If that does not work, one must fight with the armies (C. Shi 2018b). Traditionally, it was at this point in the house cleaning when the intestines and butchered body of the ox were brought and piled between the two altars and equally offered to the two altars. The uncooked ox head was placed at the center, midway between the two altars with the oxtail facing the left altar of the land god, Tudigong 土地公, which is borrowed from the Han. Once the offering is accepted (determined by throwing the gao), the head is cooked. “It must be an ox because this is an offering for the Water Buffalo killing ritual. The head must be cooked for the gods to eat” (Yang 2018c).

No ox was sacrificed for the La Yi demonstration, and only the ox head was used, purchased at a local slaughterhouse earlier that day. The badai interpreted the ready availability of the ox head (which are seldom slaughtered) as a sign from the gods. “Without it, even the demonstration could not proceed” (C. Shi 2018b).

Every aspect of the ox sacrifice and cooking was important. Traditionally, a host family member oversaw the ox killing and preparation. “It is not a badai. It is another one who will kill the ox and then take it away to clean it and cook it and bring it back to the altar” (C. Shi 2018b). In keeping with tradition, the demonstration charred the ox head then separated the meat from the skull (Figure 7). An ax was used to split the horns from the skull. The meat was then distributed into five bowls to compliment five bowls of corn wine altar offerings. Every aspect, from the type of basin, towel, and fire used to the process of how the head must first be boiled in a pot without blood being split, was strictly observed. Throughout the process, a devotion to the thunder god, Ji Leishen 祭雷, and jade god Yuhuang Dadi 玉皇大帝, was held foremost in the minds of those doing the preparation of the ox head and its meat.

Figure 7.

The flaying of the ox head by members of the host family to make the meat an offering to the gods. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

Yang then sang to the armies. The armies are “From the past, from the very beginning of ancient times and do not use modern weapons, only spears and shields” (Hong 2018c). The soldiers from five different directions/heavens are asked to gather at the center between the two altars where the “barracks” are located.

Once gathered, the shenxiang juan—the scroll placed on the altar—is unfurled. It is extended to create a pathway from the altar to the house entrance to invite the army. As Yang chanted the invitation, he walked with a dance step along the side of the scroll. By moving back and forth with the “army,” he symbolically walked with the soldiers serving as their guide to the material world. When Yang walked on the cloth, he “walked on clouds” between heaven and earth. While doing so, he gave the army the names and information needed to protect the host family. Then the armies “must take the sacrifice and be sent back because they do not belong here. When you learned to be a badai, you have a right to call those armies and lead them” (Yang 2018c). The shenxiang juan scroll is canvas, approximately twelve inches wide and twelve feet long and colorfully painted with martial figures.

Walking on the clouds is a trained specialization worthy of note in that it reveals the intricacy of badai ritual training. Badai Shi outlined the training,

For forty-nine days, you are trained for that kind of walking. Every morning at daybreak, I washed my face and went on the roof and practiced the walk. You must walk on the house roof barefoot with a cup of wine in hand, an offering to the teachers. For forty-nine days, you cannot pause. Each day, you must do it and chant sacred words to the elements five times very fluently without any pause. You are walking on the roof, and after practicing, you learn to walk on clouds. If you pause, you must begin again and do another forty-nine days. You say those words, and that finishes that day’s practice(C. Shi 2018c).

During the call of the army, Yang described how he saw gods riding horses and how he “invited them to get off their horses and drink corn wine.” The army “took away food” with some “hanging over the table after finished eating. I must invite the gods to get their horses or vehicles (chariots) and go back to heaven with their army otherwise they will stay”. Often Yang would drink from the bowl of corn wine and gesture towards the heavens, so that the gods do not drink alone. Sometimes the gods enjoy themselves too much and are reluctant to go and must be persuaded by giving them spirit money for their travel (Yang 2018c).

Once Yang’s visits to the heavens were complete, he cleaned the altar and all the ritual implements with incense and prepared it for sacred writing, a process by which he wrote on paper a list of each altar element, thereby making them sacred. He did this to ensure that “everything is done correctly, and then I check again” (Yang 2018c). Satisfied that all was in order and done correctly, the ritual of inviting the gods and armies was complete.

That evening, when the badai had their dinner of ox meat (the first meat they had in several days), they chanted to invite the god of the treasury to come to the house and share in the sacrificial meat. For breakfast the next day, they ate ox head meat from the night before. Once dinner was complete, they chanted again, asking the god to go back because he belonged in heaven.

10. Fall: Preparing the House and Family

Traditionally, the house cleaning ritual, inviting the gods and armies, and ox sacrifice all occur in February during the lunar New Year.

The following sequence of rituals occurred in October, after harvest season, and climaxed with the water buffalo sacrifice. The eldest son of the sponsoring family invited his uncle-in-law (his mother’s eldest brother) to the ritual. A flag was hung at the house’s main entrance “for the water buffalo” (Tian 2018b), identifying the family’s ritual intent.

The Miao are not strictly defined as matrilineal in classic, anthropological terms. However, throughout my fieldwork with the Miao, I have observed a high degree of gender equity. Women are empowered and enjoy social, economic, and cultural respect, status, and autonomy. This may be attributed to the equanimity, and shared burden required by hardscrabble farming life, where women are “visible contributors to the regional culture and economy” (Faure and Siu in Oakes and Schein 2006, p. 44). “Since ancient time, the Miao have kept a matrilineal tradition and sense of respect for women, which put women before men. Our culture has no derogatory words for women. The divorce rate is nearly zero” (S. Shi 2016). When asked why the importance of women in Miao culture, badai Tian replied, “All comes from our mother. We all come from our mother” (Tian 2018b). The mother’s brother is also part of the family, that origin. “Married women and their relatives are key figures in Western Hunan Miao family and communal life, especially maternal uncles, mujiu 母舅; mother’s brothers and brothers-in-law qijiu 妻子的兄弟 wife’s brothers, often guests of honor at major ritual events like the oxen sacrifice and zhuiniu” (Katz 2022, p. 40).

Miao men are protective of their women, which may have originated at the time garrisoned Han soldiers came to the region several hundred years ago and sexualized Miao women. The eroticization and objectification of Miao women is a perception persisting to this day. Their vigorous, primal, and sensual dancing of Miao women, along with their dialogic love songs, are, in comparison to Han culture, considered sexually alluring and permissive (Rack 2005, p. 59).

The importance of the uncle-in-law is one of many expressions recognizing the importance of women in Miao society.

Miao society today keeps this system. The mother’s family is vital, and the uncle represents the mother’s family showing respect to the mother’s family. Even now, the mother is very important. So, when we say mom, as we Miao do, we always say father and mother as ‘baba.’ We do not say mama and papa. They are the same.(Peng 2018c)

Once the invitation is sent, the house is prepared for rituals. White fortune paper, representing silver, was burnt outside the house entrance to notify the gods of the family’s ritual intent. A goat and rooster, their necks tied with rope, were then led through the house and outside the house’s main entrance. “We must let the spirits know. Because we do not know where the spirits are, we take the animals to be where the spirits might be inside to prove the animals are alive and will be offered to the spirits (Tian 2018a). A ritual altar, called the “tali tree,” is then set up outside the house’s main entrance.

11. The Tali Tree

The function of the tali tree ritual was to dispel the evil spirits and curses that haunt the family (Figure 8). Unlike the house cleaning ritual earlier in the year, this and the following ritual delve into the historical and ancestral curses. The evil spirits and all the curses they embody must be called up and purged before a water buffalo sacrifice. This tree is also considered sacred because of its function and is part of a cultivated forest of spirit trees. “It also takes a long time to establish an intimate spiritual relationship with the mountain by worshipping the spirits and for the integration of the ‘implanted’ spirits and the naturally living spirits of the land” (Wang 2011, p. 133).

Figure 8.

Badai Yang during the first part of the tali tree ritual. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

The locally found tali tree is an evil attractor because the Miao consider it accursed. After all, it is rare, difficult to burn, and has no fruit or practical application. “If you see that kind of tree in the woods, you need to cut it because it is cursed, you must not let it grow. It is a symbol of the cursed and that is why it is used” (C. Shi 2018b).

An altar table was set with a rice bowl stuck with incense offerings (Figure 9). On either side of the bowl were two empty bowls face down, later filled with rice offerings. At the edge of the table facing away from the house was a series of paper flags of different colors, representing protecting spirits and serving as a fence for the altar against evil spirits.

Figure 9.

The table altar setting for the first phase of the tali tree ritual. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

A hemp rope hung with more flags and anthropomorphic figures extended from the table, representing evil spirits and protecting gods (Figure 10a). The rope was attached to a tali tree branch (approximately three meters high) and symbolized a bridge that linked present and ancient generations of the family (Figure 10b). Also on the rope, interspersed between the paper figures and flags, were looped “hooks” made of bamboo and meant to capture evil.

Figure 10.

(a,b) The tali tree altar. (b) Note the tali tree branch and the anthropomorphic figures symbolizing spirits. (Photo: Thomas Riccio).

In ancient times, many generations ago, there was a curse. It is said that the curse would continue for ninety-nine generations. But we do not know when that curse started, so we do not know the duration, and so we do not know if we are in that curse or not. It is to protect the family. To ensure that that curse will not hurt them, we need to do the tali ritual to protect the family. Since we do not know which generation has the curse, we use the rope as a symbol for all ninety-nine generations and use the hooks on the rope to separate the curse’s effects because you do not know which generation is affected by the curse. The hooks are to block the effects of the curse from ancient times. At the end of the bridge is the altar, the paper symbolic of protecting spirits, so today is completely separated from the ancient time(Tian 2018b).

If the ritual is practiced at night, as few as five flags are required. If performed during the daytime, more flags are required to attract evil spirits, which are said to travel more at night and require fewer flags and hooks to attract them.

The tali tree altar is built outside the house to prevent spirits from entering the house. Yang took the animals into the house again during the ritual to attract evil spirits with a living sacrifice. “When the spirits are ready, they will make the sacrifices at the altar” (Yang 2018b).

While Yang was inside circling with the goat, Shi posted bamboo sticks topped with red flags around the altar to further entice and capture evil spirits. To make sure the spirits do not escape the boundary of the altar, he sets a trap. Yang then circles clockwise around the altar, ringing a bell with a low chant, “whispering to attract the evil spirits.” This action is consistent with the Miao preoccupation of “possible invasions, attacks and interventions on all sides, and it points to the tension with their neighbors. This spiritual boundary is maintained through worship in daily life and important festivals. Worshipping and the relevant rituals not only cultivate Miao’s intimate relationship with the land but also strengthen the spatial boundary and their ideas of resisting outsiders” (Wang 2011, p. 132).

The bell is symbolic of the uncle-in-law who witnessed the ritual and will oversee the sacrifice of the goat. The goat’s throat was slit, and its blood drained at the altar. The final action of the ritual was an offering of rice followed by the cleaning of the rice bowls with peach water. The rice and the water used to clean the bowls were contaminated and dumped in a nearby wooded area. The table was then wiped with peach water and deemed clean and safe.

12. Jiuixi