1. Introduction

Under globalization, the cultural shock and friction brought about by the rapid increase of transnational immigration around the world will bring new challenges and difficulties to urban management and social development. Previous research has shown that migrants often cite improved quality of life as one of their motivations for migration; however, migration can lead to a loss of social networks, family and community ties as migrants move away from their country of origin (

Agyekum et al. 2021). In the process of social integration of local immigrants, religious beliefs will play a crucial role in offering social integration and support, ultimately leading to positive well-being outcomes for immigrants. For example,

Muruthi et al. (

2020) applied

Walsh’s (

2003) belief systems portion of the family resilience framework to understand the role of religious beliefs in coping with the often tumultuous migration and resettlement experiences of refugees. Based on the social functions and the ‘practical logic’ of religion (

Bourdieu 1990), religious ceremonies and shrines were thought to have the ability to provide religious immigrants with space for imagination and the necessary social places for regular religious activities (

Páez and Rimé 2014). Therefore, in recent years, the reshaping of religious sentiments, the process of constructing the sanctity of a holy place, and the relationship between the physical environment of the holy place and the imaginary space have become the focus of research in religious geography and other related fields (

Kong 2010). Previous studies have shown that the creation of a sense of place in a religious space is conducive to the construction of immigrant community life circles and relationship networks, which are related to the generation of transnational immigrants’ sense of place and community identity (

Mazumdar and Mazumdar 2009;

Chua 2014).

“Sense of place” refers to a reaction produced by the interaction of human emotions and the environment (

Relph 1976). As there will be emotional interactions between emotional factors such as people’s memory, feelings and values and local resources, individuals will develop attachment behaviors to places (

Hu and Chen 2018). For religious space,

Huang and He (

2014) believe that the factors that affect the generating of a sense of place can be classified into three categories: place interaction time, physical environment and social interaction environment. Among them, the physical environment has the function of telling stories and retaining social memory, and then by strengthening the religious atmosphere, it has an impact on the sense of place (

Aulet and Vidal 2018). Previous studies have focused more on qualitative research from the perspective of cultural geography to explore the interaction between sacred space, religious immigrant communities and places, and the important factors that affect place belonging and attachment to religious space (

MacDowall 2020). In contrast, this study it is not limited to the description of religious cultural landscapes, but the retrospect of historical context, focusing on the micro-space of religious space, and exploring the construction of local meaning and empirical research on the interaction between religion and local society still needs to be expanded.

Under globalization, the social space of Chinese cities is facing a new reshaping. The development of the social space of transnational immigrants that has recently emerged in many large cities is the most prominent (

Bork-Hüffer et al. 2016). As one of the most open-minded cities in China, Guangzhou is known as an open and inclusive immigrant city. Based on the data released by the local government in recent years,

Chen et al. (

2020) inferred that the proportion of international floating population in Guangzhou is high, and the process of local embedding is significant. The international floating population is gradually becoming an important part of the “human–environment” relationship in Guangzhou’s “population structure–community characteristics–urban space” linkage, which also makes Guangzhou more deeply integrated into the global production and relationship network. However, under the constraints of local politics, economy, environment, etc., it is almost impossible to implement bottom-up community building in Guangzhou’s transnational immigrant agglomeration area. Although there has been a relatively substantial literature on the subject of religion and migration, especially in the Western context (e.g.,

Kennedy and Roudometof 2002;

Furseth et al. 2014), research to date has not produced sufficient knowledge about how the self-identity and local meaning of the large number of transnational migrants respond in religious spaces. What is even more lacking is discussion on how the socio-cultural and physical environment of religious spaces affects and leads to the generation of a sense of place.

In summary, the objective of this study is to evaluate the generation of transnational immigrants’ sense of place and further explore the knowledge of the relevant rules between the religious atmosphere perceived by immigrants and their place identity, place attachment and place dependence in religious space. This study is designed as follows: taking the Chapelle Notre-Dame de Lourdes (CNDL) in Guangzhou as an empirical case, and issuing questionnaires to transnational immigrants in the area of this religious space; through the reliability and validity test of the recovered questionnaires, it is judged whether the questionnaire items are applicable and valid; on the basis of identifying the sense of place response of a large number of transnational immigrants in this religious space, and investigating the different atmosphere perception data they received in this environment, the data mining technique—Rough Set Approach (RSA)—is applied to pick out the core place-making elements and clarify the relevant rules and knowledge between them and the generating of a sense of place.

2. Previous Works

For many immigrant groups, culturally valued behaviors are grounded in religious associations and beliefs (

Kumar et al. 2015). Religious culture is not just a religious belief or a set of beliefs and ways of worship, but a way of life which covers a series of civilizations recognized by this ethnic group, from weddings and funerals to the law and economy (

Guveli 2015). Religion provides a means for immigrants and their allies to transform their new surroundings into meaningful spiritual, cultural and sometimes political places that facilitate immigrants’ societal integration and yet help immigrants maintain and nurture their distinct cultural identities (

Kotin et al. 2011). It is likely that many transnational migrants have experienced some traumatic event, and they often have to mediate what is happening in their outside world. Especially in the teenage years, there will be insurmountable pressure, overwhelming events and transitional chaos.

Tan (

2006) pointed out that when confronted with a profound moral crisis, many young immigrants who have already experienced traumatic events ask deep existential questions introspectively. In order to create meaning in their lives in foreign countries, many of these immigrants turned to the spirituality of faith to alleviate their trauma and to find support from a group that understood their needs. Spirituality can provide answers for transitioning youth in the period of alien adaptation, preventing suicide or destructive behavior (

Openshaw et al. 2015).

Sánchez-Alonso (

2019) believes that the church may represent a refuge and hope in the eyes of transnational migrants, alleviating shared challenges such as social isolation and other forms of immigrant stress through supportive social networks.

As transnational migrants leave their home countries with solid physical, social and cultural ties, their sense of place disintegrates. Therefore, a new sense of belonging and place identity is generated with the immigrant place, which is called the Diasporic Identity (

Gautam 2013). The generating of the sense of place of transnational immigrants in the religious places of the place of migration can strengthen the positive impact of religious beliefs on immigrant groups through the interaction between people and places, shape local identity and sense of belonging, and protect and promote the integration of immigrants into the local society (

Agyekum and Newbold 2016). The services and functions provided by the church in the immigrant’s new country are similar to those in the immigrant’s home country, and other religious artifacts such as similar religious buildings will tell stories and retain the memory of the immigrant country. A sense of place (as other related concepts like place, region, and landscape) is dealt with in many ways and, without doubt, is a very vague concept (

Hashem et al. 2013). Compared with the research on the sense of place of general places, the research on the sense of place of sacred places needs to consider religious meaning, belief and symbolic meaning. Previous research has generally observed and understood the generating of attachment, identity, and belonging between humans and their environment through the theoretical framework of space and place provided by Yi-Fu Tuan in 1977 (

Lewicka 2011).

MacDowall (

2020) believes that the spatial connotation of religious space does not come from a specific source, but is multi-level and multi-attribute. Although there are certain common laws in the generating mechanism of people’s sense of place in religious spaces, it depends on each person’s different perception of the religious environment. Although the urban space of transnational immigrants has become the focus of scholars in related fields, the research on the agglomeration space of Chinese transnational immigrants is very limited. In particular, there is less discussion on how urban micro-spaces create, express and maintain cultural identity from the perspective of transnational immigrant beliefs.

As one of the main factors affecting the generation of a sense of place, the physical environment has a very real, immediate or long-term impact on people’s behavior, psychology and body (

Najafi and Shariff 2011). The placemaking of urban spaces is generally analyzed by observing the interaction time, aesthetic perception and social behavior of people in the place (

Huang and He 2014). A person’s interaction time in urban space, and the intensity of his experience in space, enhance people’s understanding of space and give it meaning (

MacDowall 2020). The dynamic relationship between aesthetics and society can also play a role in propaganda and appeal to people in the space, promote people’s interactive behavior, and render the meaning of space (

Hu and Chen 2018). With regard to the placemaking of holy places, other cultural objects such as architecture also tell stories and preserve social memory and enhance the sanctity of the place by shaping “transcendence”. The environmental layout of religious buildings is a rigid condition for the development of religious activities, which also has an important impact on the improvement of the sense of place.

Mazumdar and Mazumdar (

2009) summarized three components of the process of religious place-making in immigrant communities: (1) local organization and planning, which helps bring communities together to fit, purify and transform spaces; (2) place design, which needs to conform to religious requirements, promote a special relationship between spaces and activities and transform spaces that promote a sense of community; (3) place activities and the physical environment needs to meet the religious as well as social and cultural needs of the immigrant community.

3. Methodology and Steps

This study takes the Chapelle Notre-Dame de Lourdes (CNDL) in Guangzhou as an empirical case, and obtains the implicit rules by processing relevant data such as the sense of place and the perception of religious atmosphere of foreign immigrants in this religious space. In this study, a three-month period of data collection was carried out around the CNDL, and questionnaires were mainly distributed to foreign immigrants in the venue. Then, this study uses the attribute reduction algorithm and rule extraction algorithm based on rough sets to process the data, and finally picks up the core place-making elements and clarifies the relevant knowledge of the rules between each element and the generating of the sense of place.

Rough set is a mathematical tool proposed by Polish scientist Pawlak in 1982 to deal with fuzzy and uncertain knowledge. It can effectively analyze various types of incomplete information such as inaccuracy, inconsistency, incompleteness, etc. It can also find hidden knowledge and reveal potential rules through data analysis and reasoning. At present, rough sets have been widely used in various fields, such as machine learning in the field of artificial intelligence, knowledge acquisition, analysis and decision-making, etc; it can also be combined with other soft computing methods to design smarter and more efficient hybrid systems (

Sihotang 2020;

Fang et al. 2021). For a large number of data sets, the connection between data usually represents special practical significance. However, due to the huge database, manual processing is almost impossible, and the introduction of rough set method can refine a large amount of data into knowledge described in the form of rules, which is convenient for analysis.

3.1. Rough Set Approach (RSA)

Step I: build an information system. The information system can be expressed as , where refers to a finite non-empty object set (called “universal set”), and denotes a finite non-empty attribute set (which can be divided into two finite non-empty sets, namely condition attribute and decision attribute ); , where denotes the value set of each attribute . represents the information description function (e.g., if then ) defined by mapping to .

Step II: confirm the indistinguishable relation. For any condition attribute subset

, its correlation equivalence relation is defined as Equation (1).

Step III: set the upper and lower bounds. The set

(

) refers to a subset of conditional attributes.

refers to the equivalent class function of attribute subset

for each object. The approximation set of the object

is obtained by using the equivalence class function

, and then the lower approximation set

and the upper approximation set

are obtained as shown in Equations (2) and (3).

Step IV: confirm the dependency of condition attributes. The whole domain

is divided based on the indistinguishable relation of decision attribute

. See Equation (4).

where

,

refers to the lower approximate bound of each subset of the condition attribute

B for the decision attribute

, and it also represents the positive domain range of the decision attribute.

can be calculated by Equations (5) and (6).

The degree of dependence between the condition attribute

and the decision attribute

can be calculated by Equation (7), where

represents the cardinality of

and

represents the cardinality of

.

where

shows the degree of dependency between the subset of decision attribute

and the subset of condition attribute

.

Step V: calculate the importance of condition attributes. As shown above,

represents the degree of consistency in the decision table and the degree of dependence between attributes

and

. Then, check how the coefficient

changes when the condition attribute

is deleted. In other words, the difference between

and

is clarified. Finally, the difference can be defined as the importance of attribute

after normalization, as shown in Equation (8).

Step VI: deduce knowledge rules. As for the reduction of condition attribute set, the correlation between condition attributes and decision level will be maintained. Therefore, a set of decision rules can be derived from the decision table for the purpose of decision analysis, as shown in Equation (9).

3.2. Data Collection

This research mainly collects data in the empirical case religious space by means of a questionnaire survey. As an empirical case in this study, Chapelle Notre-Dame de Lourdes (CNDL) is a small Catholic church located on Shamian Island in the urban area of Guangzhou, China. The church was built in 1889 and is located in the French Concession of Guangzhou Prefecture with an area of only 60 mu (as shown in

Figure 1). Shamian Island was a French concession in the early days. After the Second World War, the Chinese government took back the concession, and the church was handed over to the South China Diocese of the Chinese Anglican Church. The CNDL presents a typical Gothic Revival architectural style. The building is located in the northeast corner of Shamian Island, covering an area of over 1000 square meters. The layout of the building adopts a Chinese-style north-south orientation layout, with a Basilica-style plane and a single-spire Gothic style. The exterior shape of the church consists of a towering bell tower and a rectangular chapel. The combination of the tower and the spire forms the bell tower at the entrance. The side walls of the tower and the chapel deliberately highlight the elements of the vertical pointed arch and the minaret, and the Gothic lines are distinct. The rose windows on the three sides of the clock tower have been simplified, and are only made into the form of a recessed round window hole. Only the round high windows of the chapel retain the symbol of the rose pattern, and there are no structural forms such as the spire arches and flying buttresses. This is in keeping with its smaller building volume, which is simple and elegant.

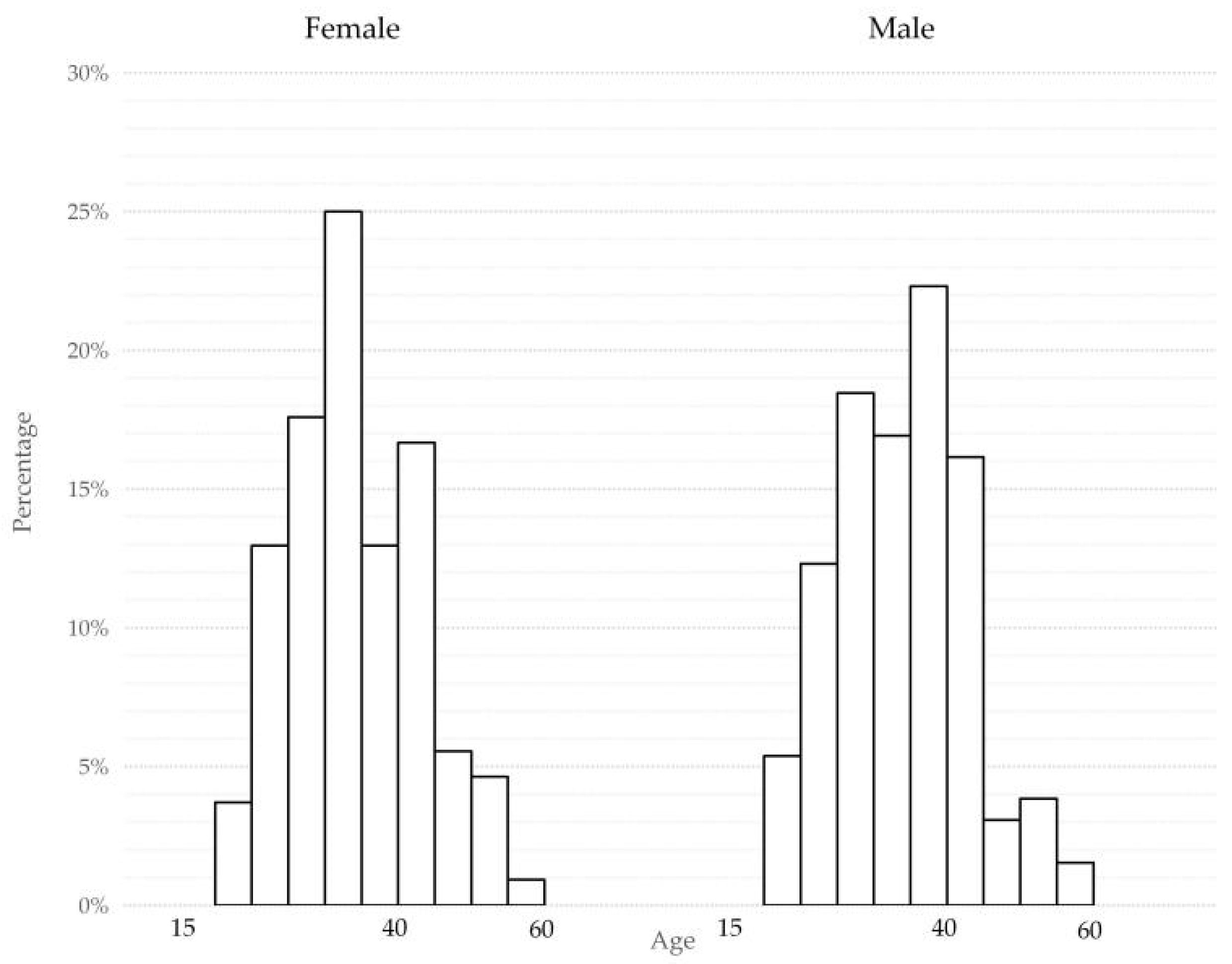

The respondents were transnational immigrants who visited the CNDL in Guangzhou between July and October 2021. Foreign immigrants who have lived and lived in Guangzhou for more than 3 years and have stable jobs were selected from the respondents for questionnaire testing. During the questionnaire survey of this research, a total of 317 foreigners were observed to visit CNDL in Guangzhou, of which 246 respondents accepted the questionnaire, and 238 valid questionnaires were finally obtained. The gender and age structure ratio of the subjects tested by the questionnaire are shown in

Figure 2, and the sample distribution has a good balance.

The questionnaire consists of two parts: (1) a survey of foreign immigrants’ sense of place in the religious space; (2) a survey of foreign immigrants’ perceptions of their environment in the religious space. In this study, the measurement data of each respondent’s sense of place within this religious space are considered as decision attributes (

D), and the survey data of each respondent’s perception of this environment as conditional attributes (

C). This study investigates foreign immigrants’ perceptions of place in a religious space, focusing on aspects of attachment, dependence, and identification. Combined with the division of the sense of place dimension in related research, the evaluation items of sense of place in this part of the questionnaire are divided into three dimensions: place attachment, place identity and place dependence. This part of the questionnaire is composed of 12 items, which are measured by a positive sentence system. Each measurement indicator is measured using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (representing “strongly disagree”) to 5 (representing “strongly agree”) (as shown in

Table 1).

By summing up the recognition degrees of the 12 sentences collected in the questionnaire, the

PA,

PI and

PD scores of each sample were calculated, and the sense of place score corresponding to each sample was obtained. The formula for the measure of decision attribute is:

This study collected conditional attribute data by investigating people’s perceptions of the sociocultural and physical environment in the religious space. A sense of place, or place attachment, is not just an emotional and cognitive experience. The sociocultural intangible attributes recognized by this study include the historical importance of the place, activities on the street in support of ritual (since this is a study of religious and sacred sites) and the opportunities for interaction and belonging on the street that exist. In terms of the physical environment, the condition attributes include the lighting, landscape vegetation, building materials and colors, architectural style characteristics and daily maintenance. Therefore, the environmental perception evaluation items of the religious space in this part of the questionnaire are divided into two dimensions: social culture and physical environment. This part of the questionnaire consists of 9 elements of environmental perception, and the semantic scale is divided as shown in

Table 2.

4. Results and Discussion

This study applied the RSA technique to sequentially analyze the knowledge of hierarchical patterns between foreign immigrants’ environmental perception data and sense of place assessment data (place attachment

PA, place identity

PI, place dependence

PD) in religious space. The overall quality of the decision class approximation boundary for the three sets of data obtained by calculation is, respectively, 0.983, 0.887, and 0.937 (as shown in

Table 3), and the approximation accuracy for each class is shown in

Table 4. The results showed that the classification boundary of the global decision has a high approximation quality. In terms of approximation accuracy, the approximation boundaries of each category of the three data sets are fuzzy, that is, there is a fuzziness (i.e., roughness). On the other hand, by calculating the importance of the conditional attributes through the RSA technique, the nine environmental perceptual elements extracted from the relevant literature that have a key influence on the formation of people’s sense of place in religious places were further selected and summarized. This study found that for foreign immigrants’ place attachment formation at CNDL in Guangzhou, the sense of history and value of this religious space (

C11), was of low importance compared to other environmental elements (conditional attributes) and was screened out of the core attributes. In addition, the results of the data analysis (

Table 3) show that the three elements of lighting environment (

C21), material and color of the building (

C23), and attractiveness of the building’s features (

C25) in the religious place cannot be considered as core conditional attributes for foreign immigrants to form a sense of local identity in this religious place due to their low level of importance. Compared to other environmental elements, the natural landscape features and vegetation within this religious space (

C22) do not play a significant role in influencing foreign immigrants to develop local dependence in the religious space, and are screened out of the core attributes.

In previous studies, scholars have often expressed the term “place attachment” as a positive emotional attachment between place and person, in which group cultural characteristics, place habitability, social interaction and communication play a crucial role (

Kyle et al. 2004). In this study, RSA can produce minimal-coverage rules, 25 rules in this dataset. Among these, 8 rules apply to the “Good” class (

D = 3), 5 rules apply to the “Medium” class (

D = 2) and 12 rules apply to the “Poor” class (

D = 1). In order to better promote the formation of place attachment of foreign immigrants in religious spaces, this research only focuses on the “Good” class (

D = 3) and sets the data percentage threshold of this grade to 10%. As shown in

Table 5, there are 3 rules in which foreign immigrants have a certain probability of having a better sense of place attachment in the CNDL place if the required status of the conditional attributes is satisfied; there are 4 rules revealing that if the required status of one of the conditional attributes is met, it will effectively contribute to a good sense of place attachment among foreign immigrants to the CNDL area; 3 rules indicate that foreign immigrants have a certain probability of developing a better sense of place attachment in the CNDL if one of the conditional attributes is fulfilled.

The findings suggest that foreign immigrants’ sense of place attachment to the premises of CNDL in Guangzhou, in addition to being influenced by physical environmental factors, depends to some extent on the social environment and opportunities for interaction in that religious space, as well as support for religious ritual activities. The type, frequency, quality and public participation in religious rituals in a given place are related to the maintenance of foreign immigrants’ own religious beliefs, the satisfaction of their spiritual needs, and the formation of local attachments (

Huang and He 2014;

Counted and Watts 2017;

MacDowall 2020). As

Hashem et al. (

2013) have emphasized, the importance of social interactions cannot be ignored, local attachments develop as people interact positively and socially compatible in places, and the sense of local attachment is directly related to the power and rate of these transmissions. Based on the hierarchical knowledge obtained, this study found that when foreign immigrants have not yet developed a strong sense of local belonging to a religious space, a site that supports frequent and interactive religious rituals and provides a natural, harmonious, and solemn green landscape to the population can effectively promote a sense of local attachment to the place. On the other hand, based on the results, it is easy to find that the establishment of emotional relationships between religious spaces and foreign immigrants depends on the satisfaction and perceived judgment of the immigrant community on the physical environment of the place. The speed of attachment and identity building depends on the light and shadow environment, the color and material of the buildings, the natural vegetation, and other environmental elements related to the creation of the religious atmosphere that people perceive in the places. The CNDL is a Gothic style building with a steeple shape and a three-part upper, middle and lower facade. The building has been repainted in white and warm colors, which makes it more harmonious and unified in the sand-faced complex. Although the building is much smaller than the Sacred Heart Cathedral, which is located in the same area of Shamian, the stained glass makes the interior of CNDL more soft and solemn, creating a harmonious and intimate atmosphere.

In contrast to the core conditional attributes of place attachment formation, the establishment and strengthening of a foreign immigrant’s sense of place identity, also requires a uniqueness of the religious space, in addition to the experience of iconic activities over time. Since foreign immigrants shape and clarify their identities through uniqueness and interact with places to construct their identities; this is also a process of their social identity construction. This means that the religious connotation and history of the architectural space of CNDL, as well as the ritual services provided by the place, are needed to bring out the uniqueness of the space and to separate the foreign immigrant community from other religious communities and the native population in the site. In addition, the physical environment of CNDL should be able to better perpetuate the emotional memory of the foreign immigrants, which helps to accelerate the construction of their local identity. In previous studies, some scholars also call it a “Diasporic Identity” (

Brah 2005). As suggested in

Table 5 rules 4–7, if a religious space provides immigrants with religious services and functions similarly to those of their home countries while focusing on the historical authenticity of religious buildings and maintaining the character of the interior and exterior natural landscape, this will help to enhance the narrative of the space and preserve the common emotional memory of immigrants.

The place survey revealed that the area where CNDL is located is home to a large number of foreign immigrants living in Guangzhou. In other words, the respondents of this study were very familiar with this location. The longer the respondents have lived in Guangzhou, the more they report that their own personal abilities and knowledge have been enhanced here, that they have made many friends in this religious space and that their work and life here are going well. As suggested by

Table 5 Rules 8–10, the formation of foreign immigrants’ sense of place dependence at CNDL is significantly influenced by the environmental elements under the socio-cultural dimension. If foreign immigrants perceive the historical importance of religious space and receive support to facilitate frequent religious activities, complemented by interior light and shade, and facade materials and color features that are in harmony with the overall environment of a clean and orderly religious space, this will significantly increase the immigrants’ local dependence on this place. In this study, foreign immigrants’ place attachment to the religious space, also known as functional attachment, refers to the degree to which the place is satisfying for the realization of personal self-worth. The results showed that the functional attachment to this religious space was not overshadowed by the emotional attachment, although it was often latent and silent. Being in a foreign country, many respondents agreed that they are enhancing their social contacts through their religious beliefs and do not believe that expressing such needs would be seen as utilitarian and negative. In fact, CNDL is indeed a place of social integration for them, and its social interaction environment attributes cannot be ignored. Some immigrants become part-time or full-time clergy or choir members, responsible for organizing group Bible sharing and communication activities. The division of labor in religious organizations enhances the functional attachment of foreign immigrants to their locations, accelerates their integration into the native religious organization system, develops karmic and religious ties with local clergy and residents, and contributes to the social integration of foreign immigrants.

5. Conclusions

The sense of place explored in this study is based on the micro-scale of religious space. From the perspective of globalized transnational immigration’s sense of place, it is one of the important research directions of new cultural geography to explore the construction of local meaning from the microscopic urban space. This study uses the Shamian Chapelle Notre-Dame de Lourdes (CNDL) in Guangzhou as an empirical case to investigate the sense of place and environmental perception evaluation of foreign immigrants in this place. This study mainly emphasizes the attachment to, dependence on, and identity of foreign immigrant groups with a religious space, combined with the division of the concept of sense of place in relevant research. Therefore, this research divides the items of the sense of place into three dimensions: place attachment, place identification and place dependence. This study found that in the Shamian area of Guangzhou, foreign immigrants generally have a high willingness to integrate. Guangzhou has provided abundant job opportunities and business services for the international floating population, enabling the immigrant group (especially the economically driven floating population) to play a higher economic role and gain a better sense of economic gain.

Although respondents’ experiences of integration varied, the data mining reflected the basic paradigm of foreign immigrants’ sense of place in religious space: immigrants’ perception of the physical environmental elements of religious spaces are particularly important for the formation of the group’s place attachment and dependence; the formation of a sense of place identity is more dependent on the social and cultural atmosphere that foreign immigrants perceive in a religious space. This study suggests that project managers or planners should focus on controlling the lighting layout and light and shadow effects inside religious buildings, the natural landscape features in courtyards, and the materials and colors of building facades. The findings also reveal the importance of prolonged interaction and socialization with place in the process of generating a sense of place in the holy space, both in relation to the imaginary space in which religious teachings are formed, and the functional role of religion in influencing social relations. In addition, paying attention to the material environment of religious spaces, we should create a religious atmosphere familiar to immigrant groups and improve religious services so as to help foreign immigrants establish new local connections.

The limitations of this study should be acknowledged as they may provide guidance for future studies. First, this cross-sectional study used a convenience sample of expatriate immigrants from the Shamian area of Guangzhou city. To overcome this limitation and advance the interpretation degree, a future study should conduct long-term research on a random basis with a sufficient number of samples. Second, the evaluation items on the sense of place are derived from the more common sentence systems in the relevant literature. In the future, based on this research, a more systematic evaluation index system for the sense of place of religious places at the micro scale can be constructed. On this basis, the multi-attribute decision-making (MADM) model can also be applied, and from the perspective of the formation of a sense of place, several religious spaces in the same region are selected as empirical cases to sort the performance of the cases. Third, variables such as the immigrants’ country of origin or their religious practice before emigrating were not included in this study. The immigrants’ perceived sense of place and behaviours may be constrained by the fit between environmental conditions in religious spaces, and individual life experience of religion, both in their origin countries and in the new ones. In consideration of this point, the subgroup differences of immigrants’ value, capital, and habitus in religion can be explored in future studies, in order to make a better understanding of the rules between the sense of place construction in religious spaces and the environmental perception among different subgroups of transnational immigrants.

Furthermore, based on the evaluation and analysis of the site environment of the empirical case, further explore the specific improvement strategies. This study argues that with the acceleration of globalization, transnational migration is undergoing unprecedented and frequent spatial transfers, the inherent sense of place is breaking or continuing, and new local meanings are constantly being reconstructed and produced. Therefore, the identity construction of the diaspora community has been paid more and more attention in the international academic community. It is worth mentioning that religious spaces are not only places for accommodating religious activities, but also directly participate in the construction of local meaning as a medium. In turn, this special local meaning will continue to guide the religious behavior of immigrants and even their daily behavior space.