Abstract

Balancing the communitarian, civic, and liberal aims of faith-based education presents a significant challenge to most religious education teachers. The communitarian approach to religious education is the most common, as it socializes children to become members of a given faith community. It recognizes students’ rights to collective identity and belonging. The civic approach to religious education asks, “what is the preferred meaning of respect in a religiously pluralist society, and how can it be promoted in the context of a deep belief in the primacy of one religion?” This approach also concerns itself with managing religious identities in a multifaith and democratic society. Liberal religious education involves asking the question, “how can one’s own religious doctrine be taught so as to allow the widest possible scope for critical reflection within [and about] a faith tradition?”. The current review essay addresses these questions by exploring the meanings, significance, and limitations of each approach and their possible implications for Islamic education in Israeli-Arab and Muslim-majority schools.

1. Introduction

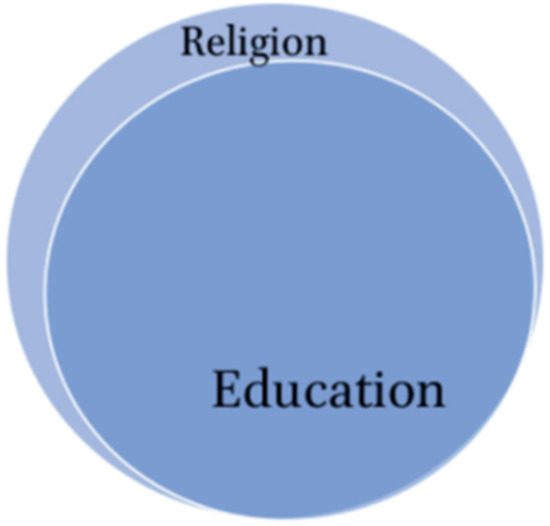

Religious education is defined differently depending on the religious landscape of the country in which it is practiced. The features of a country’s religious landscape include the role and value of religion, the relationship between the state and religion, and the history and politics of the school system and its divisions (Schreiner 2002). Religious education is broadly defined as the teaching of a set of beliefs, practices, narratives, written traditions, and values about the sacred and the relationship of members of a faith community to God. These elements may include transcendental doctrines, traditional stories, myths, sacred rituals, and ethical codes (Gross 2011). The literature differentiates between education into religion, education about religion, and education from religion (Schreiner 2002; van der Kooij et al. 2017). Education into religion means the cultivation of students’ religious identities to mold them into believers and members of a specific religious tradition. This kind of education is referred to here as communitarian. The following Figure 1 represents this idea of religious education:

Figure 1.

Education into religion and the communitarian purpose of religious education.

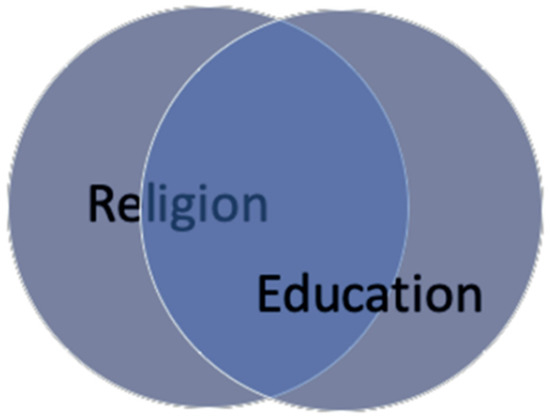

Education about religion refers to learning about the beliefs, values, and practices of a religion: “seeking to understand the way in which they may influence behaviors of individuals and how religion shapes communities [and the interactions of believers and non-believers]” (Schreiner 2002, p. 83). This type of religious education is referred to here as civic. The Figure 2 clarifies this point:

Figure 2.

Education about religion and the civic purpose of religious education.

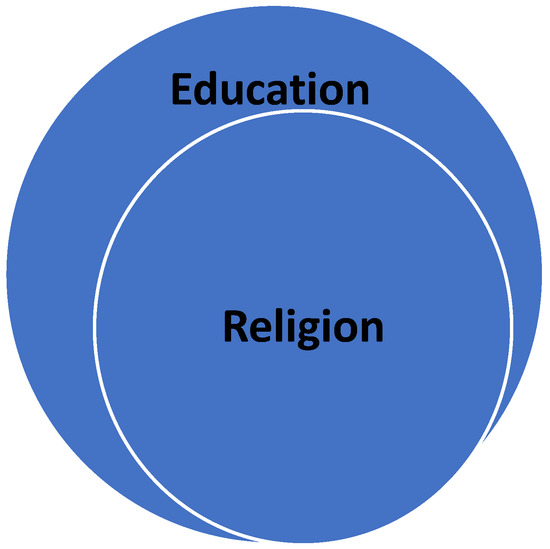

Education from religion gives pupils the opportunity to consider different answers to major religious and moral issues, so that they may develop their own views in a reflective way. This approach puts the experience of the pupils (and their individual development) at the center of the teaching (Schreiner 2002, p. 83). The Figure 3 reflects this approach to religious education:

Figure 3.

Education from religion and the liberal purpose of religious education.

Balancing the communitarian, civic, and liberal aim of faith-based education presents a challenge to religious education teachers. This is because faith-based education emphasizes education into religion (the communitarian aspect of religious education) and the socializing of children to become members of a given faith community. The exclusive focus on educating for religious collective identity and belonging—which is often demanded by parents and community leaders—may exclude civic values such as pluralism, tolerance, and mutual understanding (both within the religion and between the religion and the larger society), as well as liberal values such as autonomy and critical thinking (Halstead 2014; Tan 2008), which are essential for living in a democratic and multifaith society.

Civic religious education asks, “what is the preferred meaning of respect in a religiously pluralist society, and how can it be promoted in the context of a deep belief in the primacy of one religion?” (Feinberg 2006, p. 173). It also concerns itself with managing religious identities in a multifaith and democratic society. The liberal challenge for religious education relates to the extent of freedom, independent thinking, and agency that teachers may allow children in cultivating their religious identities. This involves asking, “how can one’s own religious doctrine be taught so as to allow the widest possible scope for critical reflection within [and about] a faith tradition?” (Feinberg 2006, p. 173). It views students as active creators of meaning and moves from an institutionalized to an individualized understanding of religious interpretation.

This essay argues that the communitarian, civic, and liberal aims of religious education should not be viewed as competing targets or as mutually exclusive. In fact, they are all legitimate and deserve attention from religious educators and scholars. This essay illuminates the meanings, significance, and limitations of the communitarian, civic, and liberal aims of religious education and their possible implications for Islamic religious education in Israeli-Arab and Muslim-majority schools. Islamic religious education aims, in general, to develop the students’ intellectual moral, spiritual, and physical capacities so that they behave as faithful practicing Muslims (First World Conference on Muslim Education 1977; Hussain 2004).

Islamic religious education in Israel emphasizes education into religion, or education which socializes students into being believers and members of a faith community. In fact, the communitarian approach of Islamic education is very common in Israel and worldwide (Anderson et al. 2011; Fandy 2007). This essay aims to challenge this limited approach to Islamic education and to encourage a consideration of the complementary civic and liberal aspects of Islamic education. These purposes are becoming urgent for living in postmodern, democratic, and multifaith societies. The author writes as a liberal Muslim who lives in an Israeli, Western, multifaith, and democratic society. The term “liberal” is compatible with education from religion, and it is defined further in the following sections. It entails prioritizing autonomy, rationality, independent thinking, and justice for both Muslims and non-Muslims while “consuming” the religious knowledge produced by Muslim scholars in the past and present. Islam, for the liberal Muslim, is “a historically situated expression of spiritual visions and ethical ideals” (Filali-Ansary 2003, p. 31).

2. Islamic Religious Education in Israel

Muslims in Israel constitute most of the country’s Arab citizens (82.9%, as compared to 7.9% Christians and 9.2% Druze) (Haddad Haj-Yahya et al. 2022). Muslim Arabs are undergoing competing and contradictory processes of religification (Islamization) and modernization (Al-Atawneh and Ali 2018). The educational system in Israel is divided into four branches (Jewish secular, Jewish religious, Arab, and Jewish ultra-orthodox). Arab citizens have their own schools and enjoy some level of cultural and religious autonomy (Maoz 2007). That is, Arab children (Christians, Muslims, and Druze) learn in Arabic from Arab teachers and principals, who are hired and supervised by the Israeli Ministry of Education.

Arab schools are public, are attended mainly by Muslim students, and have included religious education alongside other subjects (math, languages, and science) since 2014. Islamic education (like religious education for other faiths) in Israel aims to acculturate students to a communal system of norms and religious values. Muslim students are initiated into Islam by Muslim teachers, who are expected to exemplify what it means to be good believers.

(Saada 2020a) found that the teachers interviewed in Israel supported the Salafi (conservative), rather than the liberal, conceptions of Islamic education. Salafi Muslims seek to redefine Islam as how they imagine it was during the time of the Prophet Muhammad and his early followers. That is, they deem authentic Islam to be comprised of anything literally stated in the Quran, and in the hadith reports (actions and statements of the Prophet Muhammad). Salafism is, in short, an Islamic religious ideology that supports a literal and exclusive interpretation of the Quran, the hadith, and Islamic law (Al-Jabri 1996; Kecia and Leaman 2008). Therefore, in accordance with this ideology, Islamic education teachers in Israel focus on the transmission of religious knowledge, rather than on the practice of critical thinking and reflection. In addition, these teachers avoid dealing with the intellectual diversity within Islam, the discussion of contemporary issues, and the tenets of other Abrahamic religions (Saada 2020a).

The author argues that the conservative approach of Islamic religious education is not adequate for living in the multifaith society of Israel, where Muslims have to develop a respectful and peaceful dialogue (with believers and non-believers of other religions) about the meaning and practice of a good life and society. They must be able to negotiate and perhaps revise their religious identities in the rapidly changing and globalized world. This need arises from the exclusive focus on the communitarian aims of Islamic education and the lack of attention paid to the civic and liberal aims of Islamic religious education in Israel and worldwide, which have informed the writing of this article.

3. The Communitarian Aims of Religious Education

The communitarian approach to religious education socializes students into a specific religion by transmitting the community’s faith, rituals, and doctrine to them. The communitarian approach may take place in faith schools or through specific classes designed for this purpose.

The communitarian approach to religious education is justified by the following arguments: first, “the ability of parents to raise their children in a manner consistent with their deepest commitment is an essential element of expressive liberty” (Galston 2002, p. 102).

Second, religions provide people with ways of knowing and living that meet human demands not necessarily satisfied by rationality, empiricism, or logic. They provide believers with answers to existential questions, such as, “where does man come from and where does he go? Why is the world as it is? Why are we here? What will give us courage for life and what courage for death?” (Kung 1978, p. 75). In addition, religions may provide believers with the tools to deal with basic human feelings and experiences, such as suffering, tragedy, death, sacrifice, salvation, love, and beauty.

Third, some philosophers of education (Alexander 2008; Palmer 1993) criticize the exclusive focus on universal rationality proposed by Kant and argue that religious traditions provide young students with a concrete vision of the good and of how to live in a just society. In other words, religions provide students with a higher good (a purpose and definition of a good life, society, and human beings) to which they may aspire, by which process they become better versions of themselves. They answer moral questions, such as, “how should I live my life? What is important to value? What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be good? What are my obligations to others, family, friends, strangers?” (Kunzman 2006). By the same token, religious and ethnic groups or minorities have the right to preserve their own identities, because these identities provide their members with meaning for their decisions (Feinberg 1995; Halstead 2009; Kymlicka 2020).

Fourth, it is argued that children have a psychological need for a coherent and stable primary culture that is consistent between home and school environments, so that they develop a sense of belonging and a safe environment (Halstead 2014, 2009; Merry 2007; Tan 2008; Thiesen 2012). In other words, “children’s minds do not operate in a cultural vacuum until they are mature enough to reflect on the nature of social and moral rules” (Halstead 2009, p. 57). Feinberg (2006) adds, “the self-esteem of children is so dependent on that given to their parents, teachers must be extremely cautious in the way they address those features of a child’s life, language, skills, and beliefs that are tied closely to the esteem with which the child’s parents are held” (p. 192). Fifth, students who develop a strong religious self-identity and who are treated fairly and justly by broader society are likely to grow up into tolerant, balanced, and responsible citizens (Short 2002).

4. The Limitations of the Communitarian Approach to Religious Education

Scholars have criticized the devotional approach to religious education in democratic and multicultural societies (Feinberg 2006; Thiesen 2012; Tan 2008; Saada 2018). It is possible to summarize the limitations of communitarian religious education into the following points:

First, such education assumes that there is only one true religion and that therefore all other religions are false or wrong and that adherents of other beliefs will be punished. This form of education, which does not allow students to think or reflect critically about their beliefs, is a kind of indoctrination (Tan 2008) because it limits the students’ autonomy and constrains their open-mindedness (Bailey 2010). Barrow and Woods (2006) explain, “the most obvious hallmark of the indoctrinated person is that he has a particular viewpoint, and he will not seriously open his mind to the possibility that viewpoint is mistaken. The indoctrinated man has a closed mind” (p. 73). (Hare 1985) adds that, “the open-minded person is one who is willing to from an opinion, or revise it, in the light of evidence and argument” (p. 16). Indoctrinated students will not be able to reflect upon their prejudices and biases and will therefore be prone to the influence of authoritative texts and figures.

Second, the lack of exposure to other religions and worldviews may lead to religious illiteracy, which fuels “prejudice and antagonism, thereby hindering efforts aimed at promoting respect for diversity, peaceful co-existence, and cooperative endeavours in local, national, and global arenas” (Moore 2010, p. 5). Religious illiteracy is defined as the lack of understanding about (1) the basic tenets of the world’s religious traditions; (2) the diversity of expressions and beliefs within traditions that emerge and evolve in relation to differing social/historical contexts; (3) the profound role that religion plays in human social, cultural, and political life in both contemporary and historical contexts (Moore 2010, p. 4). Religious illiteracy encompasses the ignorance not only of other religions, but also of the diversity within religions.

Third, claiming to have a monopoly over religious truth or interpretation, and not dealing with diversity within religions, may lead to discrimination against politically or religiously marginalized and weaker members of the same faith. This will potentially produce tensions, hate crimes, and bloodshed, as has happened historically between, for example, Sunni and Shia in Islam, and Catholics and Protestants in Christianity.

Fourth, education that aims to create monolithic or pure religious identity mystifies the dynamic nature of both religions and personal identities. In fact, religions are fluid, shift in relation to culture and context (Barnes 2014; Moore 2010), and are influenced by political and social discourses. In addition, “identity is multiple, changing, overlapping, and contextual, rather than fixed and static” (Banks 2008, p. 133). According to Panjwani (2005), “the meanings religious people give to their practices, values, norms and institutions are the result of the creative and dialectic relationship between them and their environment” (p. 382).

Fifth, educating for pure or utopian religious identity can easily lead to extremism (Saada 2022). Hull (2000) has criticized devotional religious education because it leads to religionism—a belief that is based on prejudice, exclusion, or the rejection of other religions and worldviews. Religionism promotes the belief that, “we are better than they. We are orthodox; they are infidel. We are believers; they are unbelievers. We are right; they are wrong. The other is identified as the pagan, the heathen, the alien, the stranger, the invader, the one who threatens us and our way of life” (p. 76).

The problem with the communitarian approach in Islamic religious education is that it may create a puritanical conception of Islam that is incompatible with life in a democratic and multifaith society. This, Wilkinson (2015) argues, may push young Muslims to leave their religion or to become extremist believers.

5. The Civic Aims of Religious Education

According to MacMullen (2018) and Mason (2018), it is incorrect to argue that all kinds of religious education are unable to prepare students to become informed, good, and active citizens. It is, rather, the specific types of transmitted civic knowledge, skills, and virtues that should be examined in this matter. In fact, some religious schooling may promote civic knowledge, skills, and virtues.

Civic knowledge, in the context of religious education, may include learning about the internal diversity within a religion, as well as diversity between religions. It is assumed that students need to learn about and develop a sympathetic understanding of different religious traditions in their societies. This is because we live in pluralistic societies where citizens face cultural and religious diversity at school and work and in higher education, shopping malls, and their neighborhoods.

According to Gross (2011) “religious education must include some types of interdenominational and interreligious learning in line with the increasingly pluralist situation of many countries (dialogical quality, contribution to peace and tolerance)” (p. 259). Without education about religious diversity, students become religiously illiterate, and therefore may not be able to function effectively and confidently in a multifaith society. Teaching about other religions can develop a basic level of trust and understanding among different religious groups. Developing respect for, and recognition of, religious, moral, and ideological diversity is crucial for living in a democratic and multicultural society (Williams et al. 2008).

The civic approach to religious education assumes that there are several legitimate religious traditions in society and that these traditions have their own definitions of the nature of the good life and society. What is important is not who is right or wrong; rather, it is the ability to hold a peaceful and respectful dialogue among numerous incommensurable religious and moral traditions, and to come up with shared insights on “a modus vivendi that enables people to live together across deep difference” (Alexander 2016, p. 87). Nash (1996) added that the purpose of ethical dialogue among believers of different religions is to train children to “listen carefully, reason sharply, respond empathically, raise trenchant questions … and … deal comfortably with ethical complexity and ambiguity” (1996).

Educating for civic virtues in religious education assumes that “all the world’s major religions espouse at least some values that can be interpreted to align with core liberal commitments such as tolerance, mutual respect, and the equal moral worth of all persons” (MacMullen 2018, p. 147). Gutmann (2003) argues that the civic virtues that should be promoted to achieve the civic minimum are racial, religious, and gender non-discrimination; respect for law; tolerance; mutual respect among citizens; respect for individual rights; respect for the equality of human beings; and the peaceful resolution of conflicts between different groups. Religious education may lead to a deeper level of tolerance between different citizens by arguing that citizens should tolerate practices that they do not like, not just because they believe that their fellow citizens have the right to do so, but also because they understand that they have their own rational arguments for these behaviors.

Achieving these virtues entails developing civic skills, such as perspective taking, informed empathy, respectful dialogue, intercultural sensitivity, and moral reasoning. Moral reasoning “involves the application of rationally justifiable moral principles in a rational way to the specific circumstances of any case requiring a moral judgement or decision” (Halstead and Pike 2006, p. 18). Furthermore, teachers may use religious terminology to condemn slavery, unequal suffrage, severe poverty, and unequal protections under the law. Martin Luther King’s work against racial segregation using religious arguments to support democratic and social justice is a good example of this.

6. The Civic Aims of Islamic Religious Education

The civic purposes of Islamic religious education can be understood as the belief that diversity in society is willed by God. For instance, there are plenty of verses in the Quran confirming that plurality is willed by God (5:48; 6:107; 10:99; 11:118; 16:93). These verses show that, “God if he had so willed could have joined humankind into one single community or could have compelled them to believe” (Sejdini 2022, p. 100). This makes sense, because the imposition of any faith contradicts the idea of free will, and people with no free will cannot be judged by God. The Quran confirms: “There is no compulsion in religion” (2.256, 10.99, 18.29).

Other verses (2:136; 3:64; 3:84; 5:48) similarly show that,

Islam views itself as part of the monotheistic tradition and makes no distinction between the prophets who are part of that and, in the Islamic view, have been chosen by the same God and are tasked with the proclamation of the same divine message.(Sejdini 2022, p. 114)

In fact, Muslims are requested to respect and believe in all prophets mentioned in the Quran; and the prophets Abraham, Moses, and Jesus are called Muslims in the Quran (Hermansen 2016).

In addition, the Quran (3:75 and 3:113) avoids sweeping judgments of Jews or Christians. It does not exclude them from the possibility of salvation (2:62) (Sejdini 2022). It says, for instance, “[F]or, verily, those who have attained to faith (in this divine writ), as well as those who follow the Jewish faith, and the Sabians, and the Christians—all who believe in God and the Last Day and do righteous deeds—no fear need they have, and neither shall they grieve” (2:62). Asad (2008) concluded that salvation in the Quran does not depend on religious affiliation. It depends on believing in God, the belief in the Judgment Day, and performing righteous deeds.

Another possible way of achieving the civic aim of Islamic religious education is to focus on the commonalities among different religions. This includes, for instance, the teachings about the similarities between Islam, Christianity, and Judaism in terms of creeds; rituals (such as praying, fasting, and giving to charity); holidays; myths; symbols; and customs. To achieve this aim, then, Muslim students may learn the stories of the prophets Muhamad, Jesus, and Moses, and the common values derived from these stories.

Other teachers might emphasize the periods in Islamic history when tolerance was the dominant policy towards believers of other faiths (Hermansen 2016; Sachedina 2001). Others may decide to focus on the debate about democracy in Muslim societies (Saada 2020b), how it fits with or epistemologically contradicts Islamic teachings, and how to think about democracy from an Islamic perspective (Saada 2020c).

7. The Limitations of the Civic Approach to Religious Education

The pedagogies outlined in the previous section do have some limitations, which can be summarized in the following points: First, not dealing with the truth claims of religions may lead to relativism (it does not make sense theologically and logically that all religious systems lead to salvation). Second, they do not prepare students to live in a society in which difference is inevitable, nor to deal peacefully with the differences between religions that may cause tensions, conflicts, and misunderstandings. In other words, the focus on the similarities between religions is a kind of wishful thinking that ignores the intractable divisions arising from different normative claims (Barnes 2014), and it misses the point of how believers perceive and appreciate their own religions (Kunzman 2006; Rosenblith and Priestman 2004; Wright 2007). This line of thinking has not made the world a safer place (Prothero 2010), and it does not lead to the civic tolerance that is crucial for living in democratic and multicultural societies.

Third, the pedagogies mentioned above do not pay adequate attention to alternative arguments that are based on humanist or secular ideologies. Ironically, the Islamic education curriculum in Muslim-majority schools in Israel does not cover any topics related to secularism, but Muslim citizens are expected to eventually participate in secular Israeli society.

Fourth, the pedagogies mentioned above do not encourage students to reflect critically on the mechanisms of producing religious knowledge in society and how these might be used or misused for political purposes. In essence, religious and moral agency that is based on open-mindedness is necessary for revising or adapting religious identities in rapidly changing societies. The participation of the southern Islamic party in the Israeli government in 2021 emphasizes the significance of critical reflection on the meaning and role of Islam in democratic politics. These limitations lead us to a liberal and critical approach to religious education that we explain further in the following section.

8. The Liberal and Educational Aims of Religious Education

The liberal aim of religious education is to develop students’ critical reflection, as well as their religious and moral agencies. The term “liberal” aims to challenge the dichotomy in the literature between liberal values and Islamic values (Filali-Ansary 2003). Liberal or progressive Islam can be viewed as an “umbrella term that signifies an invitation to those who want an open and safe space to undertake a rigorous, honest, [and] potentially difficult engagement with the tradition” (Safi 2003, pp. 16–17). Liberal Islam challenges “the transmission oriented and rigid interpretations of Islam and seek[s] to appreciate and to contextualize the religious claims which are compatible with ideals of reflective education, rational thinking, mutual respect, and equal citizenship” (Saada and Gross 2017, p. 807). As shown in the third figure, liberal Islamic education allows students to question all religious interpretations, the applicability of these interpretations in their lives, and how they apply to life in democratic and multifaith societies. In fact, it challenges monolithic, essentialized, ahistorical, dogmatic, literal, and past-oriented interpretations of Islam and its primary sources (the Quran and the Sunnah).

Educationally, students are supposed to justify their religious and moral decisions and to revise them when confronted with new evidence or rethinking. This releases students from fixed religious dogmas and pre-prepared answers about their faith, and promotes self-reflective inquiry, which is necessary for living in democratic and multicultural societies. Religious and moral agency are discussed further in the following subsections.

9. Religious Agency

Religious agency is defined here as the ability to develop and refine one’s religious claims and beliefs by comparing religious interpretations and examining the merits and viability of one’s own faith from outside a tradition. Religious agency allows for more autonomy and responsibility for individuals to cultivate their own religious identities. It is not necessary that all believers of a religion share a homogenous or monolithic understanding of their faith. According to Quinton (1985), there are “continuously variable degrees of belief and not just the decision between believing a proposition, believing its contradictory and suspending judgment” (p. 47). In essence, we might think of beliefs as “true or false, important or trivial, interesting or uninteresting, relevant or irrelevant, appropriate or inappropriate” (Barnes 2014, p. 244). What is important is that students reflect on and revise their religious beliefs depending on the strength of the evidence available to justify and support them (Hobson and Edwards 1999).

Religious agency assumes that: First, religions are dynamic entities (Barnes 2014), and religious knowledge is produced by religion scholars according to their experiences; life conditions; and, sometimes, their political orientations. Therefore, what was produced in the past might not be relevant in the present, and students have the right to question and examine the validity of past religious interpretations and how they might be corrected or changed to fit the needs of life in modern societies. For instance, Muslims’ interpretation of tolerance in treating the religious Other in the past may no longer be valid, and a new interpretation of the Quranic statements on this matter is therefore required.

According to Aslan (2015), “living in the various European countries, Islamic theologians felt compelled to look beyond their traditional frameworks and to address questions that had no place within their own history” (p. 32). In other words, a religion does not offer ashes, but instead passes on the fire (Sejdini 2022). That said, critical reflection on religious arguments enables students to actively contextualize, refine, and develop their religious interpretations. For example, critical reflection encourages Muslim students to question the premodern interpretations of religious texts, to conduct Ijtihad (rational thinking), and to come up with new and reasonable answers to the phenomena that they face in their lives. Issues such as the compatibility of Islam and democracy; the status of women in political, juridical, and religious spheres; the status of believers of other religions and non-believers in Muslim majority societies; and the meaning and practice of personal autonomy (freedom of thought, speech, and conscience), must be reconsidered.

In addition, the liberal approach to religious education is not at odds with Islamic intellectual heritage. In the Quran, for instance, there are abundant words that encourage Muslims to think and reflect critically about God’s wisdom. These include tafakkur (contemplation), tadabbur (reflection), tafaqquh (understanding), and taaqqul (reasoning) (Davids and Waghid 2016). In addition, critical reasoning and rational inquiry were integral to the work of Muslim theologians and philosophers (such as Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), Al-Farabi (878–950), Al-Kindi (801–873), Ibn Aqil (1040–1119), Al-Ghazali (1058–1111), and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (1126–1198)) during the golden age of the Islamic empire (between the eighth and twelfth centuries).

Other Muslim scholars, such as Al-Jahis (776–869), Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), and Al-Zarnuji (1196–1223), condemned passive learning, or learning by rote, and instead suggested a student-centric pedagogy that used dialogue and discussion, problem-posing and reflection, deductive reasoning, critical reading, and the applicability of knowledge (for further explanations, see Tan 2014; Tan and Ibrahim 2017). Also, the different and valid religious decisions made by the four major Imams—Abu Hanifah (699–767), Malik (711–795), Ibn Hanbal (780–855), and Shafi (767–820)—during the eighth century indicates that religious reasoning and inquiry may lead to multiple legitimate religious answers (for further analysis see Al-Azhari 2009)

Second, religious knowledge and interpretations are influenced by different political communities of interpretations. Religious knowledge can be politicized to serve the agendas of powerful groups and to oppress others. In fact, some elites may use religious knowledge to legitimize or delegitimize religious identities and political activities. That said, students should be encouraged to challenge religious authorities who might use their power for unfair or discriminatory purposes.

According to Barnes (2014), religious education should equip pupils with the skills, abilities, and religious knowledge to enable them to challenge aspects of religion that may lead to prejudice, intolerance, or extremism. Historically, many caliphs of the Umayyad and the Abbasid dynasties used Islam or religious figures to manipulate people and to justify their regimes (Crone and Hinds 1986). In addition, “Shi’a Islam has known nothing but persecution and expulsion by most pre-modern state powers … [and] the most important founders of the Sunni law schools were either murdered or had to spend most of their lives in prison” (Aslan 2015, p. 27).

Today, many of the conflicts between groups in Muslim societies in the Middle East stem from clashes between different Islamic ideologies. In Israel, the divide between the northern and southern factions of the Islamic movement is based on different religious interpretations. The examples mentioned so far emphasize the need for liberal religious education that recognizes the politics of religious knowledge, including how it reflects the power relationships between groups and religious traditions in society, and how it may produce oppression and injustice. Students should practice evaluating their religious attitudes according to principles of justice, rationality, tolerance, freedom of conscience, and egalitarianism. These values are useful for living in democratic and pluralistic societies. Muslim students may investigate the Islamic perspective on these values and reflect on how they have been ignored or manifested in Islamic history. Shahrur’s (2022) On Freedom in the Quran: Cotemporary Reading is a good example of such an inquiry. Teachers may also encourage the contextualization and historicization of those religious verses that may lead to intolerance, and highlight those that support values of mercy, diversity, and justice.

Third, the postmodern perspective argues that language controls experience, rather than the opposite (Aronowitz and Giroux 1991). This suggests that meanings and representations embedded in the use of (religious) language are not fixed once and for all, but, rather, reflect the language games and power/knowledge relations in the broader society (Foucault 1980). That said, our religious subjectivities, consciousness, and regime of truth are matters of subjugation and liberation by different discourses of religious knowledge. Therefore, the linguistic conventions, codes, and forms of language that constitute religious discourse can be questioned, opening the possibility for individuals to rethink and reshape their religious identities.

Fourth, the expansion of social media and the massive use of information technologies in recent decades have made it impossible to shield children and young people from confrontations with alternative religions, truth claims, and non-religious ideologies. This means they may be faced with questions from outside their tradition. These questions might be ontological—why is there something rather than nothing? And what is the nature of human beings?; cosmological—what is the origin and nature of the universe and the place of human beings in it?; teleological—what is the purpose of life and what gives an individual’s life purpose or sense?; theological—is there a God? If God exists, why does He not intervene and remove evil from our lives?; eschatological—is there life after death?; or ethical—what makes things, acts, or ideas good or bad, right, or wrong? Can we live morally without a religion? Muslim students and teachers do not have to agree on answers to these philosophical and existential questions, but they do have to contemplate them and understand the merits and limitations of their faith; to tolerate non-religious arguments and ways of life; and to be able to defend their faith against common misunderstandings, Islamophobia, and orientalist perceptions (Saada and Magadlah 2021) that view Islam as antithetical to the West and therefore as anti-humanist, anti-modernist, and anti-democratic (Said 1978). Reviewing the Islamic education curricula in Muslim-majority schools in Israel shows that these questions are rarely addressed.

Fifth, each religion has its own controversies. These have to do with competing or contradictory interpretations of individual sacred beliefs (Gutmann 2003). Developing students’ autonomous and reflective thinking enables them to deal with religious controversies and to reach informed and critically justified positions. For instance, many Muslims face controversial issues in their lives, such as the place of democracy vs. caliphate (religious rule) in Muslim-majority states; the meanings of Jihad; the practice of music and fine arts; gender equality and gender segregation in public areas; the integration of Muslim minorities in non-Muslim societies; and believers’ control over their destinies. Dealing with controversial issues enhances students’ cognitive reasoning, epistemic curiosity, problem-solving capacities, skills in collecting and evaluating data, and ability to compare and contrast different attitudes (Avery et al. 2013; Johnson and Johnson 2009).

Sixth, there is a strong correlation between education that encourages critical reflection and levels of tolerance (Mason 2018). That is, there is some evidence that education enhances cognitive sophistication, and thereby contributes to higher levels of tolerance (Peri 1999; Vogt 1997; Wagner and Zick 1995). Critical reflection in religious education enables students to identify useful values in other (religious and non-religious) ways of life and to acquire a rich and tolerant understanding of how others see the world.

10. Moral Agency

According to Fisher (1999), “part of the credibility of a religious tradition is its ability to enter into reasoned and reasonable dialogue with other religious [and non-religious] traditions and the community in which is stands” (p. 110). In essence, the aim of liberal and civic education “is to create citizens [and believers] who will participate in the democratic process of collective decision-making by offering reasoned justifications for their (initial) political preferences, listening to and fair-mindedly evaluating the reasoned proposals of others, and acting (by voting, for example) on their resulting judgments about the balance of reasons” (MacMullen 2018, p. 144).

Moral agency develops through ethical dialogue with believers of other religions and non-believers (Kunzman 2006). The focus here is on moral issues, because ethical frameworks are deeply informed by religions; religions can be viewed as “concrete instruction and support regarding the meaning of life, love, goodness, right and wrong, evil, and death” (Nash 1996, p. 107); ethics are a matter of public and democratic deliberation about what constitutes a good life and society, and therefore prepare students for active citizenship. This approach encourages learning from, and not only about, both religious and non-religious worldviews; it contributes to pupils’ moral development; and it connects religious education to pupils’ realities and interests (Barnes 2014). The purpose of respectful and ethical dialogue with moral ideas and ideologies is to legitimize the diversity of ethical knowing and being and to encourage principles of diversity, freedom of consciousness, and equality of respect.

Gutmann (1994) explains that “mutual respect requires a widespread willingness and ability to articulate our disagreements, to defend them before people with whom we disagree, to discern the difference between respectable and disrespectable disagreement, and to be open to changing our own minds when faced with well-reasoned-criticism” (p. 24). Barnes (2014) convincingly adds that, “pupils need to be familiar both with secular challenges to religion and with religious challenges to secularism. There must be an open, dialectical, and critical enquiry into religious truth, an enquiry that interprets and evaluates not only religious beliefs and practices but also secular ones” (p. 241).

Saada (2015) argues that the purpose of ethical dialogue with different moral perspectives in Islamic religious education is not to show the superiority of Islam, but, rather, to “help students advance their critical thinking and moral reasoning, and to practice building up coherent and logical arguments [which are crucial for democratic deliberation in a multifaith society]” (p. 104). According to Gutmann (2003), “those who dismiss religiously based ideas in politics as dangerous because they are dependent on faith do a disservice to the non-dogmatic ways in which moral faith can work when it works best” (p. 159). Saada (2015) confirms:

if religious believers want their morals to be considered for democratic deliberation in a secular society, they cannot just use the language of sin and salvation; they need, if possible, to develop the language of reason and evidence, the language of here and now, and the language of science.(p. 102)

For instance, teachers may address the Islamic input on issues such as polygyny, gambling, sexual ethics, determining the sex of babies before birth, birth control, interest-based transactions, marrying a person from another religion, euthanasia, the transplant of organs, environmental ethics, and how to make their arguments accessible to other religious and non-religious people. They can also discuss the similarities and differences between Islam, Christianity, and Judaism regarding these issues.

Successful ethical dialogue in democratic and multifaith societies entails the acceptance of certain conditions. Alexander (2001) and Barnes and Wright (2006) talk about four such conditions. The first of these is free will and freedom of belief: that I can “do good or evil, that I am the master of my own being, and responsible for my own behavior” (Alexander 2001, p. 46). A belief can be “religious and secular, orthodox and unorthodox, realistic and non-realistic” (Barnes and Wright 2006, p. 73). The second prerequisite is fallibility: “I can misunderstand and make incorrect choices. I can be wrong, both in what I believe and in how I act” (Alexander 2001, p. 46). Fallibility implies that human beings make mistakes, learn from them, change, and grow accordingly. The third is critical intelligence: having “the capacity to understand the difference between good and bad, right, and wrong, better, and worse” (Alexander 2001, p. 44). Critical intelligence means moving away from narrow rationalism and superficial emotivism and being “attentive, intelligent, reasonable, and responsible” (Barnes and Wright 2006, p. 73) in the pursuit of truth and the ultimate order of things. The fourth prerequisite is forbearance, which means, “the greatest possible tolerance…accepting and living alongside those whose beliefs are fundamentally incompatible with one’s own” (Barnes and Wright 2006, p. 73).

The liberal approach to religious education is perhaps the most difficult for faith schools and communities because it relies on the values of autonomy, open-mindedness, critical thinking, and freedom of choice. However, as will be explained in the following section, it is possible to incorporate the communitarian, civic, and liberal aspects of religious education in ways appropriate to the students’ ages, their psychological needs, and their cognitive capacities. This point is explained further in the following section.

11. Conclusions: Balancing the Communitarian, Civic, and Liberal Aspects of Religious Education

We should not view the communitarian, civic, and liberal aspects of religious education as mutually exclusive. They can be viewed as complementary targets of religious education that respect students’ needs for belonging, civic efficacy, and religious or moral development. The communitarian approach may be more suitable for children during elementary school, as it provides belonging and cultural consistency. In other words, students at this age are in the stage of establishing an initial religious/cultural identity that is compatible with their parents and the larger community.

The civic and liberal aspects of religious education can be promoted during the middle- and high-school levels, assuming that students at this age have likely already developed the basic capacities of critical and cognitive thinking (such as reflection, abstractive thinking, and the evaluation of religious arguments and interpretations) that are crucial for civic and moral agency. According to Thompson (2004) and Halstead and Pike (2006), it is possible to encourage an advanced (civic and liberal) level of religious education when students have already established their religious identity during elementary school.

The following Table 1 summarizes the three aims of religious education:

Table 1.

The three aims of religious education.

Ultimately, teachers’ ability to incorporate the three aims of religious education into their classes depends on students’ cognitive abilities, the resources/curriculum available to them, the limitations of time, and the flexibility of the local religious community. The current essay is an invitation to Islamic faith schools and teachers to consider and pay more attention to alternative (civic and liberal) aims of religious education.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Atawneh, Muhammad, and Nohad Ali. 2018. Islam in Israel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Azhari, Muhammad. 2009. The Consensus among the Four Imams and Their Disagreement. Egypt: Dar Al Ola. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Hanan. 2001. Reclaiming Goodness: Education and the Spiritual Quest. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Hanan. 2008. Autonomy and authenticity: Alternative conceptions of education in an open society. In Autonomy and Education: Critical Perspectives. Edited by Sheila Sheinberg. Tel Aviv: Resling (Hebrew), pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Hanan. 2016. Conflicting conceptions of religious pluralism. In Islam, Religions and Pluralism in Europe. Edited by Ednan Aslan, R. Ebrahim and Marcia Hermansen. Vienna: Springer VS, pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jabri, Muhammad. 1996. The Religion, State, and the Implementation of Sharia. Lebanon: Markez Derasat. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Paul, Charlene Tan, and Yasir Suleiman. 2011. Reforms in Islamic Education. In Report of a Conference Held at the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Centre of Islamic Studies. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz, Stanley, and Henry Giroux. 1991. Postmodern Education: Politics, Culture, and Social Criticism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, Muhammad. 2008. The Message of the Qur’an. Bristol: The Book Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Ednan. 2015. Citizenship education and Islam. In Islam and Citizenship Education. Edited by Ednan Aslan and Marcia Hermansen. Vienna: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, Patricia, Levy Sara, and Annette Simmons. 2013. Deliberating Controversial Public Issues as Part of Civic Education. The Social Studies 104: 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Richard. 2010. Indoctrination. In The Sage Handbook of Philosophy of Education. Edited by Richard Bailey, Robin Barrrow, David Carr and McCarthy Christine. Thousand Oakes: SAGE Publications Inc., pp. 269–81. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, James. 2008. Diversity group identity, and citizenship education in a global age. Educational Researcher 37: 129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Philip. 2014. Education, Religion, and Diversity: Developing a New Model of Religious Education. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Philip L., and Andrew Wright. 2006. Romanticism, representations of religion and critical religious education. British Journal of Religious Education 28: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, Robin, and Ronald Woods. 2006. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crone, Patricia, and Martin Hinds. 1986. God’s Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davids, Nuraan, and Yusef Waghid. 2016. Ethical Dimensions of Muslim Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fandy, Mamoun. 2007. Enriched Islam: The Muslim crisis of education. Survival: Global Politics and Strategy 49: 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, Walter. 1995. The communitarian challenge to liberal social and educational theory. Peabody Journal of Education 70: 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, Walter. 2006. For Goodness Sake: Religious Schools and Education for Democratic Citizenry. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Filali-Ansary, Abdou. 2003. What is liberal Islam: The sources of enlightened Muslim thought. Journal of Democracy 14: 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First World Conference on Muslim Education. 1977. First World Conference on Muslim Education. Makkah: King Abdul Aziz University. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Rob. 1999. Philosophical approaches. In Approaches to the Study of Religion. Edited by Peter Connolly. New York: Cassel, pp. 105–27. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. Two lectures. In Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews. Edited by Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Galston, William. 2002. Liberal Pluralism: The Implications of Value Pluralism for Political Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Zehavit. 2011. Religious education: Definitions, dilemmas, challenges, and future horizons. International Journal of Educational Reform 20: 256–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, Amy. 1994. Multiculturalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Amy. 2003. Identity in democracy. In Identity in Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad Haj-Yahya, Muhammed, Khalaily Nasreen, and Arik Rudnitzky. 2022. Statistical Report on Arab Society in Israel 2021. Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, Mark. 2009. In defence of faith schools. In Faith in Schools: A Tribute to Terence McLaughlin. Edited by G. Haydon. London: Institute of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, Mark. 2014. Values and values education: Challenges for faith schools. In International Handbook of Learning, Teaching and Leading in Faith-based Schools. Edited by Judith Chapman, Sue McNamara, Michael Reiss and Yusef Waghid. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, Mark, and Mark Pike. 2006. Citizenship and Moral Education: Values in Action. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, William. 1985. In Defence of Open-Mindedness. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hermansen, Marcia. 2016. Classical and contemporary Islamic perspectives on religious plurality. In Islam, Religions, and Pluralism in Europe. Edited by Ednan Aslan, Ranja Ebrahim and Marcia Hermansen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, Peter, and John Edwards. 1999. Religious Education in a Pluralist Society: The Key Philosophical Issues. London: Woburn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, John. 2000. The Transmission of Religious Prejudice. British Journal of Religious Education 14: 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Amjad. 2004. Islamic education: Why is there a need for it? Journal of Beliefs & Values 25: 317–23. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, David, and Roger Johnson. 2009. Energizing Learning: The Instructional Power of Conflict. Educational Researcher 38: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecia, Ali, and Oliver Leaman. 2008. Islam: The Key Concepts. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kung, Hans. 1978. On Being a Christian. London: Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzman, Robert. 2006. Grappling with the Good: Talking about Religion and Morality in Public Schools. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kymlicka, Will. 2020. Multicultural citizenship. In The New Social Theory Reader. Edited by Steven Seidman and Jeffrey Alexander. London: Routledge, pp. 270–80. [Google Scholar]

- MacMullen, Ian. 2018. Religious Schools, Civic Education, and Public Policy: A Framework for Evaluation and Decision. Theory and Research in Education 16: 141–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, Asher. 2007. Religious Education in Israel. University of Detroit Mercy Law Review 83: 679–728. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Andrew. 2018. Faith Schools and the Cultivation of Tolerance. Theory and Research in Education 16: 204–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael. 2007. Culture, Identity, and Islamic Schooling: A Philosophical Approach. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Diana. 2010. Guidelines for Teaching about Religion in K-12 Public Schools in the United States. Atlanta: Atlanta American Academy of Religion. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Robert. 1996. “Real World” Ethics: Frameworks for Educators and Human Service Professionals. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Parker. 1993. To Know as We Are Known: Education as a Spiritual Journey. San Francisco: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Panjwani, Farid. 2005. Agreed Syllabi and Un-agreed Values: Religious Education and Missed Opportunities for Fostering Social Cohesion. British Journal of Educational Studies 53: 375–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, Pierangelo. 1999. Education and prejudice against immigrants. In Education and Racism: A Cross National Inventory of Positive Effects of Education on Ethnic Tolerance. Edited by Louk Hagendoorn and Shervin Nekuee. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Prothero, Stephen. 2010. God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions that Run the World—And Why Their Differences Matter. New York: HarperOne. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, Anthony. 1985. On the Ethics of Belief. In Education and Values. Edited by Graham Haydon. London: University of London, Institute of Education, pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblith, Suzanne, and Scott Priestman. 2004. Problematizing Religious Truth: Implications for Public Education. Educational Theory 54: 365–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan. 2015. Retheorizing critical and reflective religious education in public schools. The International Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Society 5: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan. 2018. The theology of Islamic education from Salafi and liberal perspectives. Religious Education 113: 406–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan. 2020a. Teachers’ perceptions of Islamic religious education in Arab high schools in Israel. In Global Perspectives on Teaching and Learning Paths in Islamic Education. Edited by M. Huda. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 135–63. [Google Scholar]

- Saada, Najwan. 2020b. Understanding the controversy about democracy in Muslim-majority societies: An educational perspective. Citizenship Teaching and Learning 15: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan. 2020c. Perceptions of democracy among Islamic education teachers in Israeli Arab high schools. The Journal of Social Studies Research 44: 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan. 2022. The meanings, risk factors and consequences of religious extremism: The perceptions of Islamic education teachers from Israel. British Educational Research Journal, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan, and Haneen Magadlah. 2021. The meanings and possible implications of critical Islamic religious education. British Journal of Religious Education 43: 206–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada, Najwan, and Zehavit Gross. 2017. Islamic Education and the Challenge of Democratic Citizenship: A Critical Perspective. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 38: 807–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachedina, Abdulaziz. 2001. The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, Omid. 2003. Progressive Muslims on Justice, Gender, and Pluralism. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, Peter. 2002. Religious education in the European context. In Issues in Religious Education. Edited by Lynne Broadbent and Alan Brown. London and New York: Routledge Falmer, pp. 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sejdini, Zekirija. 2022. Rethinking Islam in Europe. Contemporary Approaches in Islamic Religious Education and Theology. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrur, Tariq Muhammad. 2022. On Freedom in the Quran: Contemporary Reading. Beirut: Dar Al-Saqi Publications. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Short, Geoffrey. 2002. Faith-based Schools: A Threat to Social Cohesion? Journal of Philosophy of Education 36: 559–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Charlene. 2008. Teaching without Indoctrination: Implications for Values Education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Charlene. 2014. Rationality and autonomy from the Enlightenment and Islamic perspectives. Journal of Beliefs and Values 35: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Charlene, and Azhar Ibrahim. 2017. Humanism, Islamic education, and Confucian education. Religious Education 112: 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesen, Elmer. 2012. Democratic schooling and the demands of religion. In Commitment, Character, and Citizenship: Religious Education in Liberal Democracy. Edited by Hanan Alexander and Ayman Agbaria. New York: Routledge, pp. 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Penny. 2004. Whose Confession? Which Tradition? British Journal of Religious Education 26: 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kooij, Jacomijn, Doret J. de Ruyter, and Siebren Miedema. 2017. The Merits of Using “Worldview” in Religious Education. Religious Education 112: 172–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Paul. 1997. Tolerance & Education: Learning to Live with Diversity and Difference. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Ulrich, and Andreas Zick. 1995. The Relation of Formal Education to Ethnic Prejudice: Its Reliability, Validity, and Explanation. European Journal of Social Psychology 25: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Matthew. 2015. A Fresh Look at Islam in A Multi-Faith World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Kevin, Helle Hinge, and Bodil Persson. 2008. Religion and Citizenship Education in Europe. London: CICE. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Andrew. 2007. Critical Religious Education, Multiculturalism, and the Pursuit of Truth. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).