1. Introduction

Despite their diversity, China’s Muslims have long been engaged in the process of reaffirming their religion and identity. This process includes the construction and renovation of mosques, the dissemination of information on Islam to the world, and the translation of religious texts. Throughout the history of Islam in China, education has always been a major issue, particularly with respect to maintaining communities of the faithful within an environment that is overwhelmingly non-Muslim.

Educational efforts are inevitably affected by the political, military, and economic conditions of a given society. The year 1905 saw the abolition of the Chinese civil-service examination, which had been used to select candidates for the state bureaucracy, heralding the establishment of a new educational system in China and indicating that education in China had entered the process of modernization. Muslim elites were concerned that the Hui people

1 were being excluded from this educational reform trend because of their different religious practices. They attempted to build new-style schools to embrace the modernization of education. These new schools, and the new curriculum, were intended to ensure the inheritance of religious knowledge while also improving Muslims’ cultural literacy and promoting citizenship. Considerable scholarly attention has been paid to an overview of Islamic modernism in the early twentieth century, including cultural movements and reformed religion (

Aubin 2006;

Chen 2018;

Henning 2015).

Through its analysis of numerous Muslim journal articles, this paper traces the formation of several modern institutions in Beijing’s millennium-old Muslim quarter, Niujie (牛街), to investigate the process of Muslim education reform during the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China. Since the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), Beijing has been home to a large Muslim community (

Liu 1990, p. 10) and has also been the country’s capital throughout most of Chinese history since the Yuan. Islamic influences began to spread throughout China after the Yuan Dynasty, and with its prime status as a capital, Beijing attracted many Muslims of various origins (

Li 2017, p. 349), most of whom settled near the Niujie subdistrict (

Liu 1990, p. 7). The present study thus chooses Beijing as the primary site of Islamic educational reform studies in light of its historical and political prominence, as well as its leading position in education.

Previous research on Islamic educational reform during the early twentieth century held the efforts of reformists in high regard and emphasized the movement’s historical significance (

Armijo 2008;

Mao 2011;

Chen 2022). Such studies have focused primarily on the changes and transformations in the scholastic system in relation to such factors as student policy, curriculum, organization, management, and financing. The present paper, however, is concerned with Muslim education and sustainability as viewed from a socio-spatial structure perspective. It explores several hitherto-neglected social backgrounds of research on Islamic modernism among Chinese Muslims.

4. Changes in the Late Qing: The New-Style Schools in Niujie (1907–1911)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the monarchy—China’s traditional state format—was compelled to modernize in response to the growing crises within the empire and China’s increasing involvement in the international state system. The reformation of the traditional educational system was on the agenda in 1901, but the Qing court’s financial situation was such that they could not afford a significant expenditure on education. After the Chinese civil-service examination’s abolition in 1905, the Qing government issued a policy that encouraged modern private schools. For a time, many new schools appeared all over the country.

Historically, most Hui people were undereducated, did not understand Chinese well enough, and were restricted to jobs at the bottom of the professional ladder. For example, many Hui people during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) fought on the frontier; moreover, Hui people have traditionally been known as farmers, shopkeepers, and craftsmen (

Yang 1995). The Muslim elites realized that if the Hui people could not read, they would be prevented from embracing new social trends due to their inadequate socialization. The establishment of new educational institutions became fashionable. However, in light of their particular dietary practices and fear of assimilation, it was difficult for Hui children to study alongside Han students (

Yang 1936). As such, it was essential that special schools be established specifically for them.

Muslim elites advocated that “[the reform of] religion and education is the starting point for propelling social progress, which in turn will enlighten the nation and restore power and prosperity to the Lands under Heaven” (

Huang 1908). Accordingly, new Muslim schools sprang up in Muslim communities across the country during the late Qing Dynasty. Noteworthy new Muslim primary schools at the time included Muyuan School (穆源學堂), founded in 1906 in Jiangsu province, and Xiejin Elementary School (偕進小學), founded in 1906 in Hunan province. The name “Muyuan” means “the origin of Muslims”, which was given to highlight the school’s religious character. The name “Xiejin” means “making progress together”, implying the determination of Hui intellectuals to catch up with the tide of educational reform in the late Qing Dynasty. Among all the new schools, Beijing No. 1 Two Grade Elementary School, established by Imam Wang Kuan (a.k.a. Wang Haoran 1848–1919) in the vicinity of the Niujie Mosque, was particularly influential (

Yin 1935).

Beijing No. 1 Two Grade Elementary School was established in the posterior courtyard of the Niujie Mosque, which was dissected by boards. The eastern section was used as a school building, and the western part was used for religious activity. Imam Wang Kuan was among China’s most prominent Muslim scholars at the time and a defender of the need to modernize education. Like many elite Sino-Muslims, he had received a dual education in both the Confucian and Muslim traditions

3, reading both the Koran and Confucian classics (

Ma 1934). From 1905 to 1907, he traveled to Cairo and Istanbul, where he was impressed by the Egyptian and Ottoman Muslims’ emphasis on education. In Istanbul, he was warmly welcomed by Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1842–1918), who had taken significant action to propel modern education forward. Under his reign, 18 professional schools were established; Darülfünun, later known as the University of Istanbul, was founded in 1900, and a network of primary and secondary schools extended throughout the country (

Kartal 2016, pp. 380–85). Turkey was a positive example of a Muslim country that—through educational reform and the unity of its people—had succeeded in maintaining its Muslim identity while also modernizing. Wang explored Ottoman educational methods as well as various aspects of Islam and education, and at Wang’s request, the sultan dispatched teachers with Islamic books to China.

After returning home, Wang jointly founded the elementary school with the official of the Qing court’s Education Board, Ma Linyi (马邻翼, 1864–1938), and with several rich members of the Muslim gentry in the Niujie area, including Sun Zhishan (孫芝山) and Gu Liangchen (古亮臣). These Muslim elites—namely, the Ahong—were not only religious figures, but also handled the affairs of the Muslim community in the domains of social welfare, dispute arbitration, and education. Consequently, Wang Kuan was able to coordinate and establish a new-style school in the Niujie subdistrict.

Wang’s co-founder Ma Linyi, a Chinese Muslim who was passionate about education, joined the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance founded by Sun Yat-sen in 1905 in Japan. The following year, Ma returned home with newly acquired books and language skills, established Xiejin Elementary School, and served as its principal, despite having little experience of school administration.

Sun Zhishan, one of the Muslim elites, ran a jewelry store. In 1906, Sun and Wang Kuan made a pilgrimage to Mecca together (

Yin 1937). After returning to China in 1907, Sun served as the director of Beijing No.1 Two Grade Elementary School and personally managed the affairs of the school. His son, Sun Shengwu (1894–1975, 孫繩武), was also enrolled in the school.

Wang Kuan’s other collaborator, Gu Liangchen, lived in the north of Niujie, and was primarily engaged in the jade business. He had always been enthusiastic about education and had once attempted to establish a private tuition facility for Muslim children at his home.

The school’s name “No. 1” refers to the fact that it was the first new primary school founded in Beijing’s Niujie area, while “Two Grade” denotes that it provided two levels of primary education. According to the Regulation of Elementary School by the Imperial Court (欽定小學堂章程), which was promulgated in 1902, children began to attend elementary school at the age of seven years old. The would then spend five years completing their primary-level education (初等小學堂) and another four years completing their higher primary-level education (高等小學堂). On January 4, 1908,

Zhengzong Aiguobao (正宗愛國報), the first vernacular newspaper founded by the Hui people, advertised for enrollment in the school, specifying the age and admission requirements for students:

Our school is located in Niujie Mosque and it does not charge for tuition. Now, our school has decided to recruit 40 higher primary-level school students and 40 primary-level school students. Higher primary-level students are required to be between the ages of 12 and 16, be proficient in reading and writing; while primary-level students are required to be between the ages of 7 and 11.

To make it easier for Hui children to attend school nearby, four branches were opened in the suburbs of Beijing, breaking with the previous convention whereby schools were completely attached to mosques (see

Table 2).

As the above table illustrates, the five schools enrolled more than 300 students in total. The education offered by these new schools differed fundamentally from the traditional religious education. First, with respect to the educational content and curriculum, these new schools primarily taught natural and social sciences (such as history, geography, mathematics, and science), just like other schools. At the same time, Muslim schools established a special religious curriculum. Second, in addition to cultivating the religious talents required by Islam itself, the new schools aimed to cultivate the skills needed in society, so that the purpose was not only to cultivate imams only but also to cultivate Muslims within society; as such, the graduates of the new schools could thrive throughout society and not just in the mosques. Although some schools were located in or managed by mosques, their operations socialized with new schools and exerted a positive impact on the community. Third, the school hired full-time professional teachers, instead of

Ahong or

Halifan. Wang Kuan boasted that “all the teachers invited by the school are celebrities from the north and the south” (

Yin 1935), which reflected his extensive interpersonal circle.

The school board was composed of wealthy Hui social elites who ensured that the initial school had access to operating funds. In the Niujie subdistrict, mutton shops accounted for the highest proportion of the Hui people’s operating income. To secure consistent and regular funding, Wang Kuan and the school directors suggested “donating one silver coin for each sheep sold”, but this was opposed by some mutton retailers and ultimately failed (

Liu 1990, p. 151).

The second solution that the school directors proposed was to run a school lottery. The lottery industry had emerged during the late Qing Dynasty. As the capital city, Beijing had numerous schools, many of which faced the problem of insufficient funds. Shu Shen Girls’ Middle School (淑慎女學) was the first to issue education lottery tickets in the name of “helping girls go to school”, which attracted public attention and proved to be a great success. Thus,

Ta Kung Pao, a daily newspaper that was published in China from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, called on Muslim schools to raise funds using this method (

Anonymous 1909). Niujie’s primary schools also joined the trend. However, Wang Kuan was criticized on the grounds that Muslim schools went so far as to participate in “gambling” (

Liu 1990, p. 152).

After the 1911 Revolution, the funds and teaching staff of Beijing No.1 Two Grade Elementary School were not fully guaranteed. At this stage, Wang Kuan considered making the school public, meaning that it would be run by the government, to address funding problems (

Yin 1935). The school’s directors decided to put forward three requirements to the Ministry of Education: (1) the school’s president must be of Hui ethnicity; (2) Arabic should be taught for at least one hour per week; and (3) in recognition of the fact that Friday is a Muslim day of worship, a half-day holiday should be given on Friday afternoons (

Wang 1937). The Ministry accepted all the above requirements, and Beijing No.1 Two Grade Elementary School was officially converted into a public school on September 15, 1912 and renamed “the 31st public primary school of Beijing Normal University”, according to the school establishment order at the time (

Beijing Municipal Archives 1912). Soon after, it was renamed “Niujie Primary School”.

To summarize, the establishment of Beijing No. 1 Two Grade Elementary School constituted a significant milestone in the transformation of Muslim education. Wang Kuan is also remembered as a key figure in the promotion of both Islamic modernism and Chinese nationalism among Chinese Muslims.

5. Further Development during the Republic (1912–1937)

The collapse of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) initiated a period of political unrest and social chaos, and major changes in Chinese ideology ensued as a consequence. In responding to these changes, the Muslim literati could no longer rely on their previous Confucian approach to legitimizing their place within China’s mainstream culture. The change in Chinese society provided the basis for the Muslim religious innovation and cultural awareness movement (

Matsumoto 2003). In this regard, many Muslim intellectuals sought to “awaken” the Hui people so that they might transform their past identity as Muslim subjects of the Qing Empire into “politically conscious and active” citizens of the Chinese Republic (

Goldman and Perry 2002). Many of China’s Muslims—particularly the urban Hui—seized upon the opportunity to disseminate new ideas. They argued that the quality of national politics depended on the quality of each citizen within a country. The principle of “Five Races Under One Union” was analogized as the five fingers of one hand—that is, if one finger was not sound, the function of the entire hand would be affected. The government—and indeed society overall—was supposed to help the Hui people become responsible and well-educated citizens (

Yang 1936). Their efforts promoted modernist education for Muslim children as a form of social uplift and a program for cultivating citizens.

Between 1919 and 1921, the illustrious American philosopher and educationist John Dewey (1859–1952) visited China. During his stay, his lectures were published in numerous journals and articles, and he exerted a profound and extensive influence, both intellectually and in terms of educational institutions (

Sun 1999;

Wang 2005). In “America and Chinese Education”, he wrote,

There is nothing which one hears so often from the lips of the representatives of Young China of today as that education is the sole means of reconstructing China. There is no other topic which is so much discussed. There is an enormous interest in making over the traditional family system, in overthrowing militarism, in extension of local self-government, but always the discussion comes back to education, to teachers and students, as the central agency in promoting other reforms.

From Dewey’s perspective, education proved to be something that could improve society. Moreover, Dewey’s famous argument that “education is not preparation for life; education is life itself” became well known in China. Many Muslim intellectuals admitted that their thoughts were influenced by Dewey’s advocacy of the essentiality of education (

Yang 1936). Dewey managed to persuade another Muslim scholar, Ma Xinquan (馬心泉), of the power of education to change society (

Ma 1935). In addition, he believed Dewey’s argument that the aim of education was to serve the “needs of Society”. Thus, he strongly supported Muslim vocational education in addition to liberal education.

Many Hui people were influenced by educational reform trends during the period of the Republic of China, having come to realize that they could not make a living—let alone become qualified citizens—without basic knowledge. In 1929,

Qingzhen Duobao (清真鐸報), a monthly journal of Islamic academic culture, published a series of articles on “education reform and Islam”. The authors were unanimous that reforming Islamic education was the key to everything they had hoped to achieve. In 1929, Ma Fuxiang, Bai Chongxi, Ma Linyi, and Sun Shengwu founded Beijing Halal High School, renamed Northwest High School in 1931. At the same time, Chengda Teachers Academy, which was founded in Shandong province, was relocated to Beijing. These are Beijing’s two most famous middle schools and have been the subject of extensive discussion in earlier studies (

Mao 2011).

At that time, a significant portion of education funding was concentrated on tertiary education, while funding for elementary education remained scarce. In the past, the funding for scripture hall education had been derived mainly from the mosque’s assets or neighborhood donations (

Brown 2013). The mosque is responsible for the imam’s salary, teaching costs, and the students’ daily meals. Enrolled students are exempted or charged very small fees. The new-style school uses a class teaching system that requires more full-time teachers and is more costly. As mentioned above (see

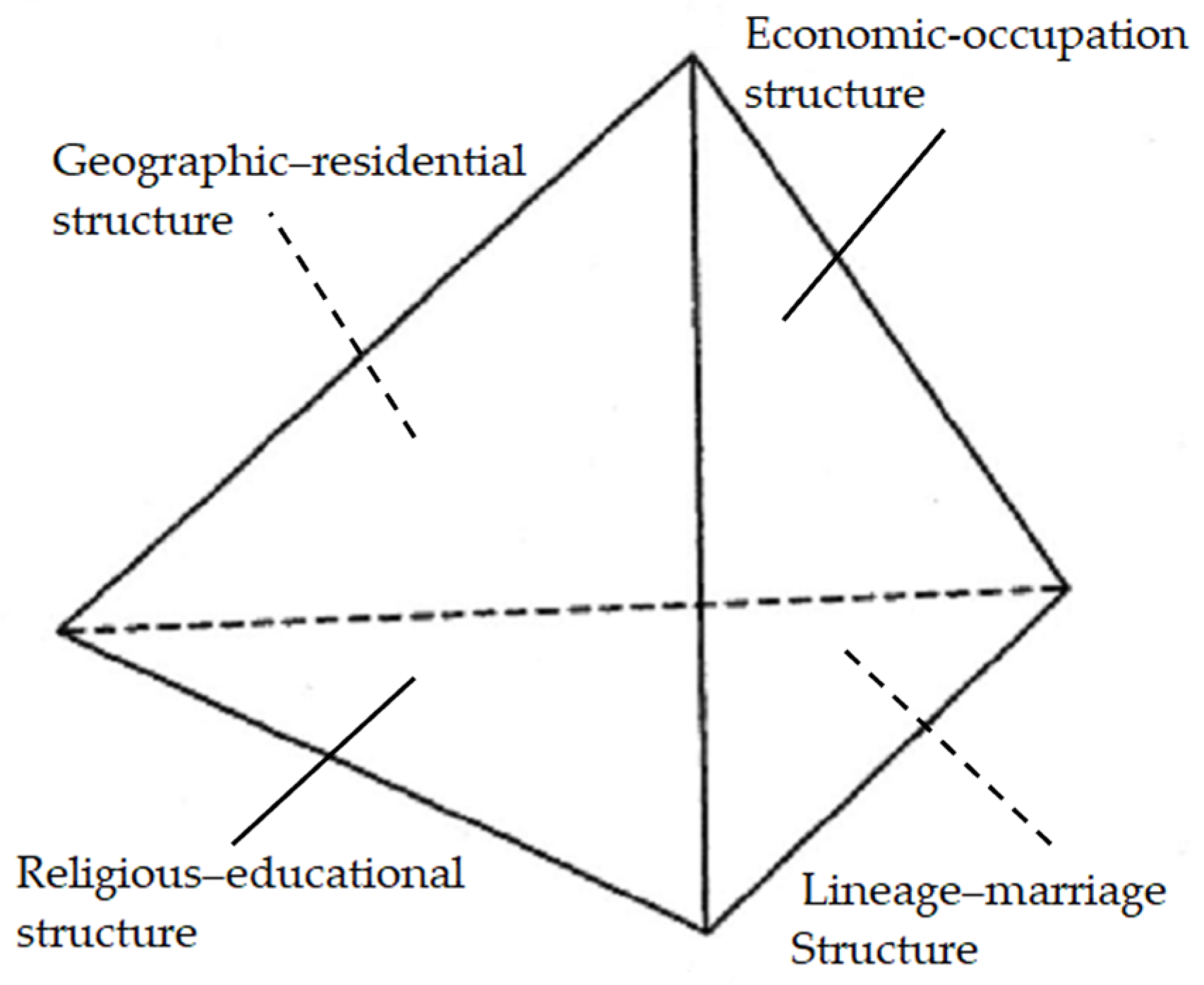

Figure 1), based on Niujie’s economic structure, guild funding became the main source of school start-up costs, along with perennial funding. That is because within a Muslim community (Jamāʿat), Hui people usually get first-hand information about job opportunities and business information, mainly through family members, relatives, and ethnic groups. In other words, they use connections in the community to get financial help to aid their small businesses. In return for this, they also contribute to the development of new-style education within the community. However, as small traders, their economic ability is limited. During the period of the Republic of China, the social and economic environment was unstable, and the Niujie Hui people could not provide long-term and large amounts of capital for the new school.

In 1921, the Mutton Guild sponsored the establishment of the Yude Primary School (育德小學, means “cultivating morality”), which enrolled 40 students (

Wang 1937) in 1931, and the Camel Transportation Guild funded the establishment of the Zhenyu Primary School (振育小學), which covered all expenses, including teachers’ salaries (

Anonymous 1936). However, as automobile transportation became increasingly available, the camel transportation industry’s turnover continued to decline.

In summary, the number of new-style Muslim schools in Beijing increased during the period of the Republic, changing the traditional enlightenment education format that Hui children were accustomed to. However, many of these schools were forced out of existence as a result of extreme financial hardship. The Hui people typically came from poorer economic backgrounds and could not afford tuition. Muslim elementary schools generally lacked stable funding; therefore, it was important to motivate society as a whole to increase the available funding channels. The social influence of the school board was particularly important in this process. Whether they relied on community donations or applied for official financial subsidies, these approaches were inseparable from the school board’s social activities. Furthermore, the Hui people had no cultural concept of the importance of sending their children to school. Only an imam acting as a school board member could convince parents and gain their trust. When government intervention made the schools’ sponsorship solely governmental, the schools’ Islamic character was gradually lost. Thus, these schools could only be run by influential Muslim elites, which resulted in the inability to scale up schooling. Such a way of establishing and managing schools is unscalable and unsustainable.

Additionally, the lack of qualified teachers was another problem that hindered the development of the new Hui primary schools. Most new-style schools were established in mosques and would only hire Muslim teachers. Owing to the very low salaries that these positions offered, the teachers hired were not qualified, and many were unable to find other jobs. They had only received traditional scripture education, with no modern scientific education, and the education method used was typically indoctrination, with a preference for memorization rather than understanding. The teachers simply read the material from the books each day in class, unconcerned with whether the students understood or not, and did not like to answer any questions. If the students could not remember the textbooks’ contents, the instructors would follow the management method of traditional education, using scolding and intimidation as the only means of disciplining the children. This method not only discouraged students from studying but also caused them to fear school and even hate their teachers. In 1925, the Chengda Teachers Academy (成達師範學院) was established in Jinan to train teachers in both the modern curriculum and religious learning. The Academy was moved to Beijing in the winter of 1929. Previous studies have concluded that Chengda produced very successful graduates (

Mao 2011). However, given that few qualified teachers had received new-style education during the Republic period, once their students had graduated, they were attracted by other non-Hui schools that paid well, and many of these qualified teachers did not go on to teach in Muslim schools (

Yang 1936).

6. Discussion

The Ming–Qing system of Chinese Muslim scripture hall education was criticized for emphasizing rote memorization and for its unstandardized and vulnerable practices of oral knowledge transmission (

Zhou 2008, pp. 81–85). Islamic society required specialists who were well-versed in Islamic teachings and laws to preside over religious affairs; however, the number of religious personnel needed was limited and an oversupply was inevitable. Many elite Muslim families sent their children to mosques for further education, regardless of their qualifications, personalities, and aspirations (

Yang 1936). Those young people who did not go on to become imams acquired no other skills that would allow them to support themselves. In the early twentieth century, many Muslim elites believed that Islamic society needed not only imams, but also teachers, doctors, judges, lawyers, tailors, carpenters, blacksmiths, silversmiths, and other professionals (

Ma 1940). As society became increasingly advanced, so too did the division of labor become more complex, and society now required a greater diversity of talents. All the skills and crafts required by Islamic society had to be specialized to meet the society’s requirements. This provided the basic context for the intentions behind the foundation of the new Muslim schools.

Chinese Muslims’ new-style schools were designed to balance “traditional” topics, such as the Arabic language and Islamic doctrine, with “modern” subjects, such as mathematics, geography, biology, physics, music, hygiene, painting, and physical education, in addition to emphasizing the Chinese language. They hoped to transform non-Chinese Muslims into indoctrinated citizens and even Chinese social elites by means of modern education.

Zarrow (

2015) examines how textbooks published for the Chinese school system played a significant role in shaping new social, cultural, and political trends, how schools conveyed traditional and “new-style” knowledge, and how they sought to socialize students within a rapidly changing society in the early twentieth century. The numerous textbooks and primers on Islamic doctrine published in the early twentieth century served the same purpose. They were quintessentially “modern” in representing Islamic doctrine as a discrete, objectified body of knowledge that could be transmitted via textbooks (

Hefner 2010, pp. 1–39). In other words, Islamic knowledge and disciplines could be transmitted as modern subjects when taught in modern institutions.

However, the curricula of the Muslim new-style schools were not adapted to the needs of Hui students. Most Hui students were poor and eager to make a living. They simply wished to learn the skills necessary for life and looked forward to a shorter period of studying. Given that the curricula implemented by elementary schools during the late Qing Dynasty were rigidly modeled after those of Japan

4, they included several courses on aesthetic education. However, Muslim students had little interest in art and singing. Many of Niujie’s Muslim students were destined to follow their families into their businesses upon leaving school. To practice art lessons, they were obliged to purchase painting materials, which increased their economic burden. Moreover, many students regularly missed school because of family wedding ceremonies, funerals, festivals, and other family obligations (

Yang 1936). Other courses taught in the schools focused on the Arabic language

5, philosophy, and the humanities but failed to train students in practical livelihood skills on a secular level. Consequently, it was said that “the courses taught by schools are not in line with actual social life” (

Yang 1936). The curriculum taught in schools did not take into account the specificities of Muslim socio-spatial structure.

After leaving education, the jobs of graduates have not changed much compared to their uneducated peers. There are graduates who cannot find a decent job and are thus unemployed for a long time (

Liu 1936). Some Muslim intellectuals believed that school curricula should focus on practical and employable skills that graduates could use in the market without requiring on-the-job training (

Yang 1936;

Lingding 1929).

By 1936, the year before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, only 5% of the Muslim children in Beijing were enrolled in school, and the overall Chinese literacy rate of the Hui people was no higher than 20% (

Liu 1936). According to a survey conducted in 1936, the occupations of Muslims in Beijing were as follows:

Among the various occupations engaged by the Hui people in Beijing, the largest number are engaged in the food industry, such as restaurants, teahouses, meat shops (selling chicken, duck, beef and mutton) and fried goods shops (selling melon seeds and candy), with a total of 9824 practitioners. There are 2301 Muslims engaged in commerce, including antique and jade stores, hardware stores, silk stores, tobacco stores, etc. There are 4003 Muslims who rely on their crafts to make a living, including working as carpenters, masons, painters, pickers, etc. The number of Muslims engaged in agriculture is 905. Among the Muslims who were engaged in decent jobs, 15 were employed in universities, 108 in secondary schools, 238 in politics, and 966 as police officers.

Based on the above, we may infer that the progress achieved in education had not fully translated into labor market success. Many students in Niujie were obliged to perpetuate their family’s small business after graduation, and the education they had received in school was incompatible with what they wished to do in the future. Many who had gained some levels of education did not have the chance to continue to higher education and compete with the majority for qualified jobs.

Hui intellectuals doubted that the young people who had received education simply consumed society’s resources without giving anything back to society after they graduated. Under such circumstances, some Hui people argued that it was better to improve the Hui people’s livelihood rather than promoting their education—that is, that it was better to build more factories than to set up more schools

6. Many intellectuals believed that education was not the most urgent thing; China’s utmost priority at that time was to develop its national manufacturing industry (

J. Ma 1940;

Z. Ma 1940;

Ding 1936). Muslim intellectuals argued that the course content should be practical and prepare graduates for entry into the labor force.

In fact, the Koran and the literature of prophetic tradition (

hadith) contain teachings that promote and encourage commerce as a livelihood. The Muslim scholar, Ibn-Sina (980–1037), advocated for children to be educated in certain professions. Once children had learned the Koran and acquired basic proficiency in Arabic, their education would focus on their future professions (

Naqib 1993). Early Muslim education also emphasized practical studies, such as the application of technological expertise to the development of irrigation systems, architectural innovations, textiles, iron and steel products, earthenware, and leather products. Evidently, Muslim educational reforms during the early twentieth century did not continue this important cultural tradition, which was important in maintaining the connection to the essence of the Islamic faith.

7. Conclusions

Using historical materials, this paper has analyzed the establishment process, curriculum, financing, and other issues pertaining to the new-style Muslim primary schools in Beijing’s Niujie subdistrict. Although this paper presents only a case study of Niujie, the “mosque-block” structure of the Hui people remains the same across other similar communities. Therefore, this paper’s key findings may be extended to the narrative of education reform among urban Hui people throughout the country.

For the founders of new-style schools during the late Qing Dynasty, as previous research has pointed out, their observations of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the nationalist secularist reforms in Turkey reinforced their desire to implement similar reform efforts and lift Chinese Muslims out of poverty in the ways they had witnessed in the Middle East. Islamic educational institutions in the early twentieth century combined the traditional scripture hall education system with Middle Eastern school education. This vision sought to align Islam and Muslims in China with trends in the Islamic world beyond China; to elevate them out of their alleged state of “backwardness” and “ignorance”; to set them firmly on the path toward progress and modernity; and to encourage them to accept the new Chinese nation and participate in its society and politics. These new-style schools invested significant efforts in evolving, adapting, and transforming themselves in response to changing needs, times, and circumstances.

The development of modern education in Niujie in the early 20th century was meant to enable young Muslims to gain more knowledge about the modern world. By doing so, it was hoped they would be better integrated within the broad scope of society, and have access to more employment opportunities and a higher socio-economic status. However, education, which is believed to be the engine of social mobility for the Hui people, has scarcely played such a role. Education offers Hui students opportunities to realize their academic potential. Unfortunately, such students in Niujie are ultimately unable to channel their unskilled labor into professions in a closed community. Low socio-economic societies are unable to provide a large number of high-quality jobs. Progress in education therefore cannot solve the problem of structural constraints. The reformation of the Muslim education system would not be achieved by the effort of establishing only one or two schools.