Abstract

From the perspective of production technology, the god image usually has two manifestations: paintings and sculptures, while there are two main forms of paintings: murals and prints. In this paper, the engravings of gods named “Guan-yin-ma-lian” (觀音媽聯) were taken as the research object. The origin of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is traced back. The form of plane composition of this type of engraving is analyzed from the perspective of iconology. The image of Mazu (媽祖) and its implied meaning in “Guan-yin-ma-lian” are discussed from the perspective of folk beliefs. As one of the plane images of Mazu, “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is not only a very important religious art in folk culture, but also an important link closely connecting Mazu belief circles at home and abroad. It is also an important cultural asset of Chinese people who worship Mazu.

1. Introduction

Mazu is one of the most widely worshiped gods in the folk beliefs of coastal areas (Zhang 2021), believers sincerely invite skilled craftsmen to sculpt large statues of Mazu in temples, while some small statues (usually about 6 or 7 inches in height) are enshrined on ships by merchantman and fishermen. Nowadays, the avatars of small Mazu statues can also be invited home from temples to worship. In addition to sculpting three-dimensional statues, Mazu is also often painted as a large mural in a temple or printed as plane images by craftsmen (Xu 2021).

Most of the images of Mazu worshiped by the people, especially in the early time, are in the form of woodblock printing or painted flat images, which can be roughly divided into two categories, one is the “Shen-xiang-zhi-ma” (神像紙馬) of Mazu alone, the other is the painting of the gods in the form of hanging scrolls, commonly known as “Guan-yin-ma-lian” (觀音媽聯). The “Shen-xiang-zhi-ma” is a kind of paper print of gods in China, which is used by people in traditional folk festivals to offer, sacrifice and pray. “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is a print of the portrait of multiple gods. The main deity is usually Guanyin (觀音). The author has already presented a special discussion on the “Shen-xiang-zhi-ma” of Mazu, so this paper will not repeat it, and will focus on the “Guan-yin-ma-lian”. “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is the most common god engraving used for sacrifice in family halls or ancestral halls in Fujian, Taiwan and Southeast Asian Chinese circles. In “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, Guanyin, usually as the main god, together with the folk gods, forms a multi-deity group.

Taiwanese scholars have conducted a lot of research on “Guan-yin-ma-lian”. Lin Yixuan 林沂宣 summarized the shape of the Guanyin in the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” through the analysis of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” he collected, but there has not been much discussion on the overall layout of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian”. On the basis of this research, Lai Wenying 賴文英 discussed the image connotation and belief connotation of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” by studying the origin and development of it (Lai 1997). Her research has important implications for the study of “Guan-yin-ma-lian”.

Based on the above research, through the observation and analysis of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” still remaining in Taiwan and Japan, this paper summarizes the three compositional schema of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” from a perspective of iconography and discusses the relationship between the compositional schema of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” and that of other deity engravings.

2. The Origin of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

2.1. Ancient Buddhist Engravings: The Origin of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

2.1.1. The Source of the Production Method of the “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

From the images of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” preserved today, it can be seen that the earliest “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is from the Qing Dynasty. And the source of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” can be traced back to ancient Chinese Buddhist prints. The first woodcut Buddhist painting in ancient China with the exact age to be examined is the frontispiece of the volume of the Diamond Sutra (Jingang jing 金剛經) in the ninth year of Emperor Yizong of the Tang Dynasty 唐懿宗. It can be seen from its rigorous knife technique, fine carvings, orderly structure, and layout, that the creation period of this painting is already in a relatively mature stage. Although this is not the earliest Buddhist print in ancient China, its origin of technique will have been inevitably influenced by early woodcuts.

The source of Chinese woodcuts can be traced back to the stone engravings (shike huaxiang 石刻畫像) of the Han Dynasty (Zheng 2006). Judging from the large number of unearthed painting bricks (huaxiang zhuan 畫像磚) in the Han Dynasty, the bas-relief paintings carved by the yang line (yangxian陽綫) or the yin line (yinxian陰綫) have the same production technique as the later woodcuts. The wooden blocks are first carved into Yangwen molds (yangwen muju陽文模具) or Yinwen molds (yinwen muju陰文模具), then stamped onto wet soft mud bricks. The creating method of wooden engraving stencils is very similar to the production techniques of woodcuts, and its imprinting (yayin壓印) method coincides with the rubbing (tayin拓印) method of early woodcuts in India. In 644 AD, after returning to Chang’an 長安 from India, the eminent monk Xuanzang (玄奘) in the Tang Dynasty printed images of Samantabhadra (Puxian 普賢) and distributed them to believers (Feng 1939). In 694 AD, Yijing (義靜) not only brought the Indian Buddhist print painting back to China, but also recorded its production method in volume four of “Rules of South Sea” (Nanhai jigui neifa zhuan 南海寄歸内法傳). According to the records, the production method was to make molds out of mud and print them on silk paper (juanzhi 絹紙) (Yi 1995). So, it can be seen that the early Indian Buddha paintings were printed on silk or paper by mud or wood carving molds. It is very similar to the creation method of the wooden carving stencils used in the painting bricks (huaxiang zhuan 畫像磚) of the Han Dynasty in China, and it also coincides with the method of imprinting (yayin壓印) on wet mud bricks at that time.

In addition, some religious Buddhist woodcuts have been found in the Thousand Buddha Caves (Qianfodong 千佛洞) in Dunhuang 敦煌 and various places in Xinjiang 新疆, such as the print of “Great sage Manjusri Bodhisattva statue” (Dasheng wenshushili pusa 大聖文殊師利菩薩) from the Five Dynasties Period, most of which are single-frame printing (danzhen yinshua 單幀印刷). Its layout is as follows: the picture above, the text below. These Buddhist images are usually carved on wood and then printed on scriptures or paintings, which are passed on to the people for the purpose of spreading teachings. After the Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty, the content of woodcuts was no longer limited to Buddhist themes. Many religious themes with folk colors also began to appear in large numbers. Various types of god prints came into being in various places, and the custom of inviting the god prints to come home for worship was becoming popular.

It can be seen that the prosperity of Buddhism in the Tang Dynasty, especially the widespread circulation of printed scriptures and Buddhist paintings, provided the opportunity for the growth of woodcut with folk religious themes such as “Guan-yin-ma-lian”. And judging from the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” of the Qing Dynasty that remains today, their production method and sacrificial custom are the inheritance of the early religious woodcut Buddhist paintings of the Tang Dynasty.

2.1.2. The Origin of the Scroll Form of the Engraving of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

The Buddhist woodcut of the Tang Dynasty and Five Dynasties can be roughly divided into three categories from the perspective of schema: title paintings of scripture scrolls, classic illustrations, one-piece woodcuts. The single Buddhist woodcuts are images with the properties of talismans such as warding off evil spirits and praying for blessings, for example, the image of Immortality Dharani (Wuliangshou tuoluoni luntu 無量壽陀羅尼輪圖) and the image of Thousand revolutions Dharani (Qianzhuan tuoluoni luntu 千轉陀羅尼輪圖). It not only could be used by monks for posting and propaganda, but also could be used by religious believers as an offering or carried with them every day. Unlike the above, the printed drawing of the Holy White Bodhisattva (Shengguan baiyi pusa 聖觀白衣菩薩) (now in the Shanghai Museum) of the Five Dynasties period is bound with a button, which can be used for suspension. This single-piece print is regarded as a precedent that woodcut art can be independently created (Wang 2002).

The single-piece woodcuts of the Northern Song Dynasty have been significantly improved in both content and technique compared with the Five Dynasties, and the size of the paintings have also expanded from four or five inches to four or five feet. The master copies of Buddhist paintings are all drawn by painters and are finely carved, so they look especially gorgeous and luxurious. In particular, the single-piece Buddhist paintings at that time could already be made into the form of hanging scrolls, such as the image of Manjusri Bodhisattva riding a lion (Wenshu pusa qishizi xiang 文殊菩薩騎獅子像) and the image of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva riding an elephant printed (Puxian pusa qixiang xiang 普賢菩薩騎象像) in the Northern Song Dynasty. The image of Maitreya Bodhisattva (Mile pusa xiang 彌勒菩薩像) collected in Kyoto is 28.4 cm in width and 54.4 cm in length. Such a large woodcut of Buddha is often used for hanging above the temple for believers to worship.

If the Holy White Bodhisattva (Shengguan baiyi pusa 聖觀白衣菩薩) in the Five Dynasties created a precedent for hanging single-piece woodcut Buddhist paintings, the single-piece large-scale hanging scroll-style Buddhist paintings in the Northern Song Dynasty are not only the evolution of the previous hanging Buddha statue paintings, but also can be regarded as the source of the hanging scroll-style engravings “Guan-yin-ma-lian” posted in the halls of later folk houses.

2.2. Folk Religious Prints: The Basis for the Generation of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

2.2.1. The Formation of Folk Religious Prints—The Soil of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

Compared with state religious woodcut engravings, the folk religious woodcut engravings not only combine the carving of professional and non-professional, but also include woodcuts of single or multiple religious deities and folk woodcut annual paintings (nianhua 年畫). Because the beliefs of the Chinese people are realistic, scattered, and diverse, as long as the gods are helpful to their lives, they will believe in them, such as Buddhist’s karma (yinguo baoying 因果報應), yin and yang (yinyang bagua 陰陽八卦) of Taoism, loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, righteousness (zhong xiao ren yi 忠孝仁義) of Confucian and folk geomantic omen taboos.

The generation of Buddha prints is actually the product of the needs of folk religious beliefs. According to their own emotional needs, Chinese people integrate the foreign gods of Buddhism with the local gods in Taoism and other religious gods, transform them into sinicized gods, and jointly incorporate them into folk belief activities. As a result, there has been a mixture of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and foreign religions, forming an intricate and mutually integrated folk religious belief complex, creating a wide variety of different types of gods with distinct functions. Based on this, a variety of folk religious wooden prints have been produced. For example, in 1994, a woodcut “Silkworm Mother” (Canmu 蠶母) unearthed in the Huang’ao 皇岙 Stone Pagoda in Wenzhou, is the earliest existing folk religious woodcut in China. The Silkworm Mother (Canmu 蠶母) is the Silkworm God (Canshen 蠶神) worshiped by silkworm farmers in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, so this woodcut is used in folk activities of “Sacrificing the Silkworm God” and “Thanking the Silkworm God”. The smooth lines on it and the skilled carving skills can reflect the prosperity of the block printing in the Song Dynasty. The carving style of the silkworm mother on it is very similar to the Buddha statues woodcuts in the Tang and Five Dynasties.

The composition of Buddhist scriptures engravings in the Tang and Five Dynasties period is as follows: the Buddha is in the center, the Xie shi (胁侍) Bodhisattva are on the side. This composition is imitated by folk religious woodcuts, and its carving style is inherited too. During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, a large number of religious woodcut prints appeared, but due to the complexity of folk gods, the diversity of people’s demands, and the mix of religious beliefs, those woodcut paintings are more secular and freer, such as the folk woodcut with the theme of Guangong (關公) that appeared in the Jin Dynasty. The Kozlov expedition from the imperial Russian era unearthed a woodcut of Guanyu (關羽) sitting in the pine forest with the flag “Guan” (關) raised high in Heishuicheng, Gansu Province in 1909. This Jin Dynasty woodcut is carved and printed by a folk workshop in Pingyang 平陽 (now Linfen 臨汾) and it can be hung separately because it is a rectangular vertical panel (lifu 立輻). Mr. Zheng Zhenduo 鄭振鐸 believes that it should be used as a god throne (shenzuo 神座) for worship, much like the role of today’s ‘zhima’ (紙祃) or ‘shenma’ (神祃) (Zheng 2006). Mr. Lü Shengzhong 呂勝中 regards it as a sign that woodcuts tend to become more temporal. After the death of Guan Gong, he was regarded as a god (S. Lü 1990). After the Ming and Qing dynasties, there was a widespread worship of Guan Gong in the court and in the folk. It is not only respected by Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, but is also regarded by the believers as an almighty protector with powerful divine power (Zhao 1957).

It can be seen that Chinese folk religious beliefs are open, flexible, and free. There is no systematic religious scriptures or strict religious system. It is just a spontaneous and simple expression of psychological demands of life by the people. Therefore, whether it is foreign Buddhism with religious principles and local Taoism with established rules, its original orderly system of gods will be transformed by the people’s bold behavior and spirit. People often transform existing gods in a purposeful manner, so there is a phenomenon of forcing a single god in the system to break away from its original orthodox status. And people even redo the combination of gods, so as to meet their certain expectations. Guanyin Bodhisattva is a typical example. Ignoring the authoritative statements of Buddhist classics, the Chinese folk carried out a complete transformation of Guanyin’s life experience, realm, status, and function with the influence of Taoism and folk religions. Therefore, Guanyin Bodhisattva in Buddhism was positioned as the god of heaven (tianjie 天界). In addition, Guanyin was also incorporated into the Taoist deity system, endowed with the function of fortune-telling, thus being shaped as a great immortal who could predict the future and give direction. The Guanyin worshiped by Chinese folk has been greatly expanded on the basis of the original form of Buddhism, so there have been images of Guanyin of different occupations, ages, and genders. In the folk, Guanyin can be offered as a single deity, and it also can be worshiped in combination with other deities. Guanyin became a commonly used deity for sacrificial rites in homes, so the engravings of Guanyin and other deities came into being.

2.2.2. The Production of Engravings of Deities Sacrificed in the House (Jiazhai Hesi 家宅合祀)—A Model for the Formation of the Image of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

From Five Gods Sacrificed in the House (Jiazhai Wusi 家宅五祀) to the Six Gods Sacrificed in the House (Jiazhai Liusi 家宅六祀)

Sacrifice is an inherent form of belief in the Chinese nation, which originates from the spontaneous nature of people and forms folk customs. Folk sacrificial customs usually take the family as a unit, and the places for sacrificing are mostly concentrated in their own residences, family ancestral halls, and temples. The earliest records of family sacrifices can be found in “Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals” (Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋) (B. Lü 2014).

The Book of Rites (Liji 禮記) has also recorded sacrificial rites. The guardian deities of the house, such as the Household God (Hushen 戶神), the Stove God (Zaoshen 灶神), the Windows God (Zhongliu shen中霤神), the Door God (Menshen 門神), the Well God (Jingshen井神) are worshiped. From the names of these gods, the origin of folk house sacrifice belief can be inferred. Humans build dwellings (windows, doors, households, wells), become used to cooked food (stoves), and need to travel long distances (walking行道).” Their ancestors built houses and started a settled way of life. After that, they longed for the protection of gods, so they worshiped the gods who were in charge of the door, the household, the well, the stove, and the window. This is called the “house five sacrifices (jiazhai wusi 家宅五祀)”. They hoped that the gods could guard the door, ward off evil spirits and disasters, and protect the safety of family members by performing the “house five sacrifices”.

In different historical periods and regions, there have been some minute adjustments of the five worship objects, but most people take Door God, Household God, Well God, Stove God, and Land God (Tudi shen 土地神) as worship objects. Over time, the custom of worshiping the five gods gradually became worshiping six gods. “History of Wulin” (Wulin jiushi 武林舊事) records the custom of sacrifices on New Year’s Eve in the Song Dynasty. On New Year’s Eve, people welcomed the arrival of the six gods with good wine and food. Zhoumi 周密 in the Southern Song Dynasty also recorded the folk customs about burning paper money (zhiqian 紙錢), placing offerings, and welcoming the six gods to the house 至除夕,則比屋以五色紙錢酒果,以迎送六神于門 (Zhou 2015). From this, although it is not clear which six gods are worshiped, it can be concluded that the custom of the “six gods sacrificed in the house” (jiazhai liusi 家宅六祀) is at least no later than the Southern Song Dynasty.

The Birth of Engravings of House Sacrifices (Jiazhai Hesi 家宅合祀)

There is often more than one deity who protects the house, so people often worship multiple gods together. Gradually, the worshiping custom of the “five sacrifices in house” (jiazhai wusi 家宅五祀) or the “six sacrifices in house (jiazhai liusi 家宅六祀)” was formed in various places. The five gods revered by the families in Fujian 福建 and Taiwan 台灣 are the Guanyin Bodhisattva, Heavenly Goddess (Tianshang shengmu 天上聖母), Guangong god (Guansheng dijun 関聖帝君), Stove God (Zaojun 灶君), and Land God. The six gods in Foshan 佛山 area of Guangzhou 廣州 are Guanyin Bodhisattva, Xuantian God (Xuantian dijun玄天帝君), Heavenly Goddess (Tianshang shengmu 天上聖母), Guangong god (Guansheng dijun 関聖帝君), and Huaguang god (Huaguang dadi 華光大帝). In Hong Kong, the Guanyin Bodhisattv, or Guangong, or Huang God (Huangdaxian 黃大仙), the Land God, Xuantian god, the Stove God are generally worshiped. In most areas of mainland China, during the Chinese New Year, the Stove God, the Land God, the Door God, the Household God, the Well Spring Boy (Jingquan tongzi 井泉童子), and the Third Aunt (Sangu furen 三姑夫人) are usually worshiped. The six gods’ image is of different genders, different ages, and different social classes, reflecting the psychological expectations of various people at different levels for a happy and peaceful family life in the new year. However, due to differences in lifestyles, habits, and appeals in the northwest region, the six gods they worshiped are different. Some people worshiped Heaven God (Tianshen 天神) (posted in the courtyard), Land God (posted at the door), Stove God (posted in the kitchen), Granary God (Cangshen 倉神) (posted in the granary), Dragon King (Longwang 龍王) (posted in the well), King of Cows and Horses (Niumawang 牛馬王) (posted in the stable); the others believed in Land God, Horse God (Mawangshen 馬王神), Door God, Well God, Cow God (Niuwangshen 牛王神), Worm God (Chongshen 蟲神).

The time and the form of offering sacrifices to the six gods are also slightly different between the north and south regions. In the northwest region, people offer sacrifices to the six gods on New Year’s Eve. For example, in Baoji 寶鷄, people usually attach the prints of the six gods with special couplets in the kitchen on the afternoon of New Year’s Eve. At the five periods of the night, the candles are lit, and the offerings are placed. After this, people invite the six gods to their house to celebrate the New Year. After putting on new clothes in the morning of the first day of the new year, before eating breakfast, people light candles and place offerings to worship the six gods again. While in Suzhou 蘇州, people usually invite the Stove God to their house to worship the six gods together. There are different ways in Shanxi 山西 in the form of worshiping: in Xi’an 西安, the six gods are placed in the shrine in the form of memorial tablets; in Baoji, the throne of the six gods written with brush is pasted at the shrine; in Fengxiang 鳳翔 and Hanzhong 漢中 areas, the woodcuts of the six gods are pasted in the shrines specially designed for every god.

In Beijing 北京, people usually used engravings composed of the Stove God, the Door God, the Household God, the Land God, Well Spring Boy (Jingquan tongzi 井泉童子), and Third Aunt (Sangu furen 三姑夫人). As recorded in volume one of the Record of qingjia (Qingjia lu 清嘉錄) (Gu 1986), in January, people hang engravings of gods in ancestral halls and light candles to pray for peace in the new year元旦為歲朝,比戶懸神軸于堂中,陳設几案,具香燭以祈一歲平安. As recorded in volume twelve of the Record of qingjia, in December, people choose a day to hang engravings of gods in ancestral halls, then they offer animals, fruits and other sacrifices to gods 擇日懸神軸、供佛馬,具牲、糕果之屬,以祭百神. The so-called god scroll (shenzhou 神軸) is actually a vertical scroll painting that gathers multiple gods in the same frame for sacrifice. The format of paintings is usually a multi-layer type, which can be divided into three layers and five layers.

The engraving named “Three gods of the family, six gods of the house” (jiatang sanzun jiazai liushen 家宅三尊 家宅六神) in the late Qing Dynasty reflects that the prints used in Tianjin have placed Guanyin, Door God, Household God, Stove God, Land God and other gods together to worship. In the article “Paintings of gods in the family hall” (jiatang zhong de shenhua 家堂中的神畫), Mr. Lou Zikuang 婁子匡 wrote that Taiwan inherited the rural customs of Fujian and other coastal areas, and they hung painting of gods in the center of the family hall. There are usually five gods in the large-scale god painting. Guanyin is on the top, Guan Gong and Stove God are on the left, and Mazu and Land God are on the right. So, these five gods are the most common and profound in the beliefs of Taiwan (Lou 1972).

The paintings of the image of Mazu, Avalokitesvara and other gods hanging in the house in Fujian and Taiwan are all available ready-made, and in large quantities before the Spring Festival. Some are painted, some are printed, and some are glass paintings painted in frames.

On the basis of the five gods and the six gods, in Fujian, Guangdong 廣東, Taiwan and other places, there has also been a custom in which the images of Avalokitesvara, Mazu and other gods are painted in a single painting to worship together. People hang “Guan-yin-ma-lian” in the halls of their house or Buddhist halls with horizontal batches and couplets, and make offerings with incense, lamps, and fruit.

3. The Printing Method and Composition Schema of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

3.1. The Printing Method of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian”

The construction method of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is to engrave the images of Avalokitesvara and Mazu on two large wooden boards, and then to print them. The first step of using the woodblocks of the engravings in Zhangzhou漳州, Fujian is to print the color and the second step is to print the ink. Taiwan has inherited the printing method of the Quanzhou, especially the traditional woodblock watermarking technology in Tainan. Its printing order is just the opposite of that in Zhangzhou. The printing table used is also very simple, which is made of two long benches. The first color plate is embedded in a large wooden frame on the printing table. The paper is fixed on the printing table with bricks for painting color. After the paper is air dried, the second color plate is positioned and the same action is repeated. The coloring sequence is from the lightest to the darkest, and the printing sequence of white is the penultimate. After that, the ink plate was printed (Lin 2016). Therefore, the early Guan-yin-ma-lian generally used this method to print on rice paper, and then it was spliced into a finished flat image by mounting.

The grander way of making engravings is to apply color on silk or rice paper by hand. Over time, some paper shops launched half-printed and half-painted forms in response to the needs of believers. Ink line woodblock was carved. Then the woodblock was inked and brushed onto paper. Finally, the face, exposed skin and clothing crown and shoes of the god were colored. After the Japanese lithography printing technology was introduced into Taiwan, it soon became the main printing method of “Guan-yin-ma-lian”.

3.2. Interpretation of the Composition Schema of “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian” from the Existing Wooden Prints

Due to the increasing innovation of printing technologies in Fujian, Guangdong, and Taiwan, the previous methods of woodblock watermarking and lithography were replaced, so the woodcuts of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” gradually disappeared. In addition, the materials used for god engravings were mostly paper or silk cloth, and changed every year, so most of the early “Guan-yin-ma-lian” were thrown away. Judging from the wooden engravings and their printed copies of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” still remaining in Taiwan and Japan, the composition schema of the “Guan-yin-ma-lian” can be divided into the following types:

3.2.1. Edge-and-Corner Composition

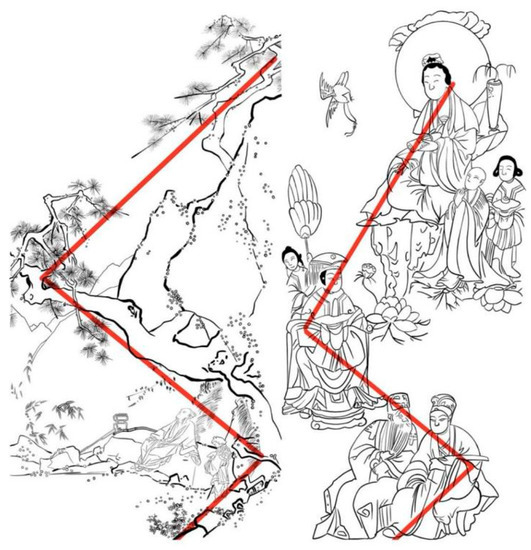

Figure 1 is the ink line wood-block of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” provided by the Japan Reference Center for the special exhibition of traditional prints held by the Taipei Art Museum. Judging from the engraving, Avalokitesvara did not sit cross-legged, but sat comfortably on the right side of the uppermost layer with the scriptures in one hand. A poplar vase (yangzhi jing ping 楊枝净瓶) is placed on the right side of the Bodhisattva, and the Good Fortune Boy (Shancai tongzi 善財童子) and dragon girl (longnü 龍女) are also standing on her right. On the left side, a warbler bird with a bug in its mouth is flying towards Avalokitesvara. In the middle left of the picture, Mazu’s hands are folded in front of him, covered with a towel, and the palace maid is holding a feather fan behind him. There are lotus flowers inscribed on the right side of Mazu. On the lower side of the picture, the god of land who is holding ingots (yuanbao 元寶), leans to the right, as if he is whispering to the Stove God.

Figure 1.

“Guan-yin-ma-lian” provided by the Japan Reference Center.

The pine figure (songtao tu 松濤圖) of Figure 2 is collected by the Liaoning 遼寧 Museum, which was painted by Mayuan (馬遠), a painter in Song Dynasty. This painter makes good use of the composition of looking up or looking at the front horizontally. In addition, he is good at highly condensing, concentrating, and generalizing the complex mountains and trees. The composition of most of the pictures of this painter is edge-and-corner composition. The main scenery deviates from the center of the picture. And he likes to paint a corner of a mountain, a part of a tree, which leaves a large area of blank in the picture, forming an open pattern. Compared with the panorama composition, this corner composition is unique, interesting, concise, and powerful.

Figure 2.

Composition form comparison.

Judging from the compositional form of this “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, as shown in Figure 2, the main gods such as Avalokitesvara, Mazu, Stove God, and Land God are not located in the central position, but located in the upper, middle, and lower side of the picture. In this way, although the overall appearance of gods is presented, there is still some blank space in the picture, creating an empty and distant artistic conception. Edge-and-corner composition is not common in the existing “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, and it even can be said to be the only one. The compositional form of landscape painting in Southern Song Dynasty had a profound influence on the engravings of “Guan-yin-ma-lian”.

3.2.2. Double-Layer Composition

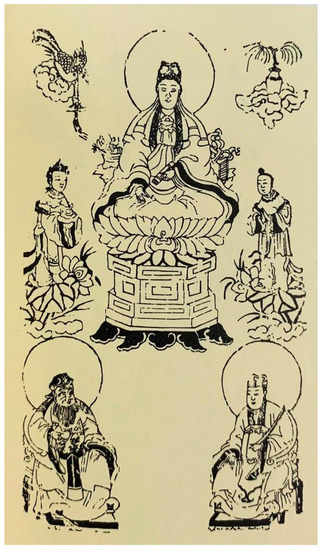

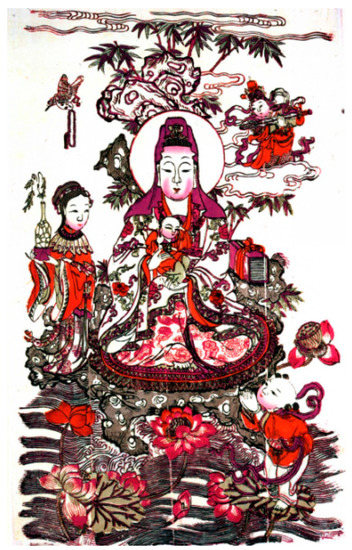

The compositional form of two “Guan-yin-ma-lian” collected in the Wenying museum of the Taichung city cultural center in Taiwan are both double-layered composition. Figure 3 is 86 cm × 50 cm, the composition of the upper layer of the picture is square and full, with few large areas of white space. The Avalokitesvara is in the center of the picture, his eyes are slightly closed, and his face is beautiful. He wears a Guanyin pocket (guanyin dou 觀音兜) on his head, shaped like a hood. He holds a scripture scroll in his right hand, sitting cross-legged on a beautiful lotus seat. In the upper layer, the upper left is the warbler bird supported by the clouds, the upper right is the poplar vase (yangzhi jing ping 楊枝净瓶), the lower left is the dragon girl (longnü 龍女), and the lower right is the Good Fortune Boy (shancai tongzi 善財童子). The top of Avalokitesvara’s head is flush with the tail feathers of the warbler and the top of the willow branch. The bottom of the lotus pedestal is at the same level as the bottom of the clouds on which the girl and the Good Fortune Boy step on, as well as the heads of the Stove God and the Land God. If the lower layer of the print is regarded as a rectangle, the Stove God and the Land God are seated on the left and right sides of the rectangle, and there is a blank space in the middle. Judging from the compositional form of the whole picture, compared with the Stove God and the Land God, the Avalokitesvara in the upper layer accounts for about two-thirds of the entire painting.

Figure 3.

“Guan-yin-ma-lian” collected in the Wenying museum (86 × 50 cm).

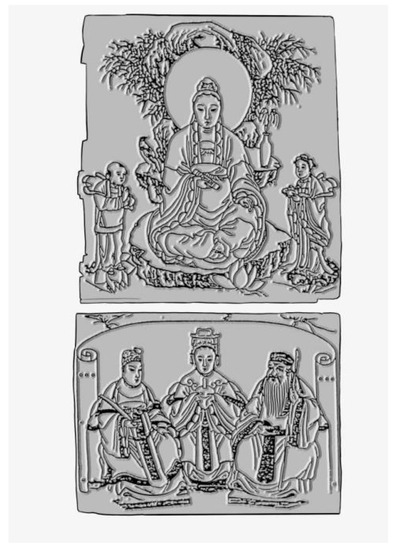

The engraving of Figure 4 is 119 cm × 63 cm. The Avalokitesvara wears a large-sleeved robe tied within a long skirt, laced up at the front waist. Avalokitesvara sits on a rock pedestal. His left hand is on his knee, and his right hand is holding the scriptures. The back side of Avalokitesvara is lush bamboo, the left side is a poplar vase, and the right side is a warbler bird. The dragon girl on the lotus leaf stands on the left side of Avalokitesvara, and the Good Fortune Boy on the lotus stands on the right side of Avalokitesvara. Compared with Figure 3, the top of the picture is bamboo extended laterally from the rockery. On the lower level of the picture, there are three gods juxtaposed in front of the folding screen, with Mazu in the middle, and the Stove God and the Land God on both sides. This compositional form of the engraving (Figure 5) is double-layer composition. The upper layer is Avalokitesvara, and the lower layer is Mazu, Stove God, and Land God. The upper layer and the lower layer can be combined into a complete picture. Mr. Zhang’s collection of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” is almost the same as Figure 3, except that there is no screen behind the three gods. It can be seen that the two-in-one woodblock composition has become an important influence on “Guan-yin-ma-lian”.

Figure 4.

“Guan-yin-ma-lian” collected in the Wenying museum (119 × 63 cm).

Figure 5.

“Guanyin Malian” collected in the Wenying museum (double-layer composition).

3.2.3. Multilayer Composition

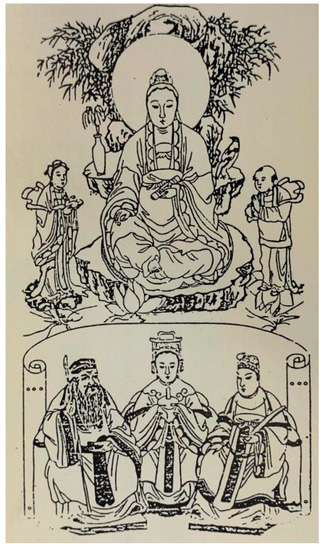

Judging from the existing engravings of “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, the Avalokitesvara usually is on the first layer, with the dragon girl and the Good Fortune Boy on the left and right; Mazu, Guangong, and Xuantian are usually the middle layer; the Stove God and the Land God are usually the third layer. Wooden engravings are divided into single editions, four-in-one editions, five-in-one editions, and so on. The more the number of editions, the larger is the “Guan-yin-ma-lian”. Figure 6 is a print of five-in-one editions. The Avalokitesvara and the dragon girl is on the first layer; smart vulture (lingjiu 靈鷲) and Good Fortune Boy are on the second layer; Mazu and his two maidens are on the third layer; the Stove God is on the fourth layer; the Land God is on the fifth layer. The size of it is 160 cm × 86 cm. It was usually hung in the family hall or the Buddhist hall accompanied by horizontal couplets (duilian 對聯).

Figure 6.

“Guan-yin-ma-lian” (five-in-one editions).

For multi-layer “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, the gods in the first and last layers usually are basically fixed, Avalokitesvara is usually in the first layer, the Stove God and the Land God are at the bottom. There are relatively many changes in the middle layers. The more common ones are the single Mazu, the combination of Mazu and her maid, the combination of Mazu, Clairvoyant (Qianli yan 千里眼), and Clairaudience (Shunfeng er 顺风耳), the combination of Mazu and Guangong, Xuantian and Mazu. In addition to this, due to the influence of modern folk beliefs, there have also been combinations of Avalokitesvara and other folk gods.

4. The Relationship between the “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian” and the Other Engravings

4.1. The Similarity of the Plane Schema of the Multi Gods Set in the God Engravings

Among the folk beliefs in various parts of China, polytheism has certain commonalities. For example, during the Chinese New Year, folk sacrifices to all gods in the three realms (sanjie 三界) are generally carried out throughout the country. All kinds of folk gods are painted in one painting, such as “All gods (Quanshen tu 全神圖)” (eight layers) in Hebei 河北 from the Qing Dynasty, “Nine Buddhas between heaven and earth (Tiandi jiufo zhushen 天地九佛諸神)” (five layers) in Beijing, “All gods of heaven and earth (Tiandi quanshen 天地全神)” (four layers) in Kaifeng 開封, Henan 河南, “All gods (Zhongshen tu 衆神圖)” (eight layers) in Suzhou. There is a great similarity in the compositional schema of god prints. These prints are basically divided into 4–8 layers. Buddhist deities such as Sakyamuni and Guanyin Bodhisattva generally rank in the first three floors, and the deities on the central axis of the picture are all high-ranking gods.

Sometimes, some people choose different gods to worship according to their own needs, so as to meet the needs of their families. Families in Huizhou usually draw Guanyin, Longevity God (Fulu shouxing 福祿壽星), and Wealth God (Caishen ye 財神爺) into a print to pray for peace and wealth. In the “Three Gods” (Sanshen tu 三神圖) printed in Suzhou, Guanyin is above, Guangong is in the middle, and Wealth God is below. An existing 32 cm × 22 cm “Guan-yin-ma-lian” from the Qing Dynasty in Zhangzhou also has three gods: Avalokitesvara, Stove God, and Land God. The composition of idols in Figure 3 is exactly the same as that in the Zhangzhou area. There are five gods in the “Five Gods” (Wushen tu 五神圖) in Foshan, Guangdong: Avalokitesvara, Xuantian god, Mazu, Guan Gong, Huaguang god, but the layout of the picture is very similar to that of the prints in Suzhou, Zhangzhou, and Taiwan. Their composition forms are both three-layer composition. The first level is Guanyin Bodhisattva. The second level and the third level are different because of the people’s belief.

4.2. The Reference and Reorganization of the “Guan-Yin-Ma-Lian” to Other God Prints

As part of folk culture, the Guan-yin-ma-lian and other god statue prints are rooted in folklore. As a materialized form of folk belief, they reflect the historical accumulation of cultures in different regions in terms of content, style, and schema. But they have the same characteristics in terms of aesthetics and artistic expression, which is the result of the historical accumulation of people’s aesthetic psychology and the integration of the art of idol image. According to research, the composition of the Guan-yin-ma-lian carved in Taiwan in the early days is almost the same as that in Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, and even the ink color and printed sheets are very similar. Guangdong is also the main source of immigrants from Taiwan, so the carving techniques of Guangzhou, Chaozhou, and Foshan have been inherited by Taiwan. In their research, Feng Jicai 馮驥才 and Yang Yongzhi 楊永智 of Tianjin University found that the layout of the images of deity disclosed for the first time in Foshan is similar to that of “Guan-yin-ma-lian”.

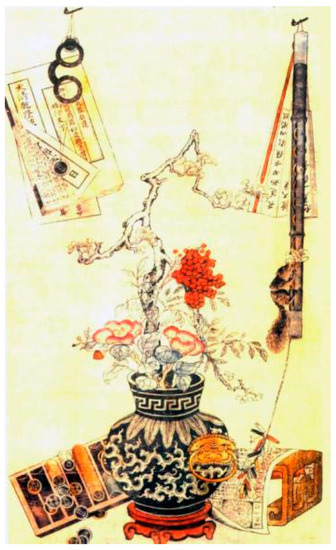

The main reason is that during the Qing Dynasty, Chinese woodblock prints were in their heyday, and workshops of god engravings spread all over the country. The workshops in Zhangzhou, Quanzhou, and Fujian are famous for the scale of workshops, the quantity and scope of sales, and the richness of styles. Taiwan and Fujian are only separated by water. Many people from southern Fujian emigrated to Taiwan, and they brought in folk beliefs, religious beliefs, and living customs, which made the early Taiwan god statue prints of very special strong Fujian color. Fujian Province is also close to Jiangsu and Zhejiang. In the middle of the Ming Dynasty, the engraving technology in the Jiangnan area was extremely brilliant. During the the Qing Dynasty, the printing technology in the Suzhou area was very prosperous, so the adjacent Fujian area was naturally deeply influenced. Figure 7 shows the Avalokitesvara print in Suzhou. The composition and style of the rockery and bamboo forest behind the Avalokitesvara in this figure are very similar to that of Figure 4 above. The warbler in the upper left corner in this figure is also exactly the same as that in Figure 1 and Figure 3.

Figure 7.

Print of Guanyin.

Figure 8 is a picture of a vase in the Qianlong 乾隆 period collected by the Aisha Art Museum in Japan. The shape of the feet at the bottom of the vase is exactly the same as that of the Guanyin lotus in “Guan-yin-ma-lian” collected by Zhang Muyang 張木養, as shown in Figure 9, but the latter has an increased number of feet due to the multi-faceted corner of the base.

Figure 8.

The vase in the Qianlong period.

Figure 9.

“Guan-yin-ma-lian” collected by Zhang Muyang.

In the combined prints of Avalokitesvara statues, the combination of Avalokitesvara and Guan Gong, Avalokitesvara and Sakyamuni, Avalokitesvara and the Land God appeared in many regions of China. Mazu has not been found in the Guan-yin-ma-lian in Foshan, and there is also no Mazu among the few remaining Guan-yin-ma-lian in Taiwan. In the article “Traditional Prints and Folk Life in Taiwan”, Mr. Pan Yuanshi 潘元石 and Mr. Lü Lizheng 呂理政 believed that in the later period, Mazu and her maids were added to the Guan-yin-ma-lian, and then they replaced the two maids with clairvoyance and clairaudience, which makes the family deity paintings include the gods of the most common beliefs of the people (Huang 1985). From this, it can be seen that the composition and style of Guan-yin-ma-lian in Fujian and Taiwan have borrowed from the prints of god in Jiangnan and other regions to varying degrees, and the Guan-yin-ma-lian were innovated by aesthetics and folk beliefs of the region.

5. Conclusions

The god engravings of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” are a product of polytheistic beliefs, and their form is a flat image. Guanyin Bodhisattva is usually regarded as the main deity. He and the folk gods together form a polytheistic group for people to worship. Since “Guan-yin-ma-lian” belongs to the folk religious prints system, the source of the images and the custom of worshiping can be traced back to ancient Chinese Buddhist prints. Its production techniques have absorbed the carving techniques of early woodcuts. The production of the engravings of the family gods provides a copy model for the formation of the image of “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, and their printing method is basically the same. From the perspective of the composition of the picture, first, “Guan-yin-ma-lian” incorporates the edge-and-corner composition of the landscape painting in the Song Dynasty, second, it is influenced by the multi-layered god prints in the surrounding areas, third, combined with the needs of aesthetics and beliefs in Fujian, Taiwan, Guangdong, and other regions, it formed a unique graphic art of the polytheistic group. So, through the observation and analysis of the existing “Guan-yin-ma-lian”, this study has interpreted the three compositional schema of it: edge-and-corner composition, double-layer composition, and multi-layer composition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S.; Methodology, B.Z., A.L. and X.S.; Validation, B.Z., A.L. and X.S.; Formal analysis, B.Z.; Investigation, B.Z. and X.S.; Resources, B.Z. and X.S.; Data curation, B.Z.; Writing—original draft, B.Z. and X.S.; Writing—review & editing, B.Z., A.L. and X.S.; Visualization, B.Z. and X.S.; Supervision, B.Z. and X.S.; Project administration, B.Z. and X.S.; Funding acquisition, B.Z. and X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Art Project “Research on Ancient Mazu Statues and Image Art under Folk Beliefs” (14CG131), National Social Science Art Project “Multi-integrated Research on Ancient Chinese Women’s Clothing (Qin, Han to Qing)” (20BG119).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feng, Zhi. 1939. Yunxian Zaji 雲仙雜記 (Yunxian Miscellany). Beijing: The Commercial Press, p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Lu. 1986. Qingjia lu 清嘉錄 (Record of Qingjia). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社, p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Cailang 黃才郎. 1985. Taiwan Chuantong Banhua Yuanliu Tezhan 台灣傳統版畫源流特展 (Research on Traditional Prints in Taiwan). Shanghai: Qiuyu Yinshua Gufen Youxian Gongsi 秋雨印刷股份有限公司, p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Wenying. 1997. A Study on the Iconography of “Guan-yin-ma-lian” in Taiwan. Master’s thesis, National Taipei University 臺北國立大學, Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Weiwen. 2016. Research on Traditional Art of Fujian and Taiwan. Fuzhou: Strait Literature and Art Publishing House, p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Zikuang. 1972. Taiwan Minsu Yuanliu 台灣民俗源流 (Origin of Taiwanese Folklore). Taipei: Dongfang Wenhua Shuju 東方文化書局, p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Buwei. 2014. Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋 (Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社, pp. 1, 67, 113, 132, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Shengzhong. 1990. Zhongguo Minjian Muke Banhua 中國民間木刻版畫 (Chinese Folk Woodcut Prints). Changsha: Hunan Meishu Chubanshe 湖南美術出版社, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bomin 王伯敏. 2002. Zhongguo Banhua Tongshi 中國版畫通史 (General History of Chinese Prints). Shijiazhuang: Hebei Meishu Chubanshe 河北美術出版社, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Zhenyuan. 2021. Building a Community: The Unique Value of Mazu Culture in Southeast Asian Chinese Society. Cultural Heritage 2: 135–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Jing. 1995. Nanhai jigui neifa zhuan 南海寄歸内法傳 (Rules of South Sea). Shanghai: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yanchao. 2021. Transnational Religious Tourism in Modern China and the Transformation of the Cult of Mazu. Religions 12: 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yi. 1957. Gaiyucongkao 陔余叢考. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Zhenduo. 2006. Zhongguo Gudai Mukehua Shilüe中國古代木刻畫史略(A Brief History of Ancient Chinese Woodcut Paintings). Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian Chubanshe 上海書店出版社, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Mi. 2015. Wulin jiushi 武林舊事 (History of Wulin). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Guji Chubanshe 浙江古籍出版社, p. 63. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).