Abstract

Deviating from the predominantly women-focused investigations on Islamic clothing in anthropology, religion and consumer studies, this research places men’s Islamic clothing under the spotlight to understand how the notion of the extended self is evidenced in a religious context. Using a multi-sited ethnographic and in-depth interview approach to study the context of middle-class Pakistani male participants of the traditional revivalist movement the Tablighi Jamaat, this study finds that possessions such as clothing serve as a conduit to participants’ sense of extended self. In this case, the extended self is associated with the Muslim nation, its Prophet and his work. This investigation furthers the concept of the extended self by implicating the consumption of religiously identified clothing as an entity that becomes associated with the self. Moreover, this study concludes that possessions and the extended self are imbricated into one’s religious career path.

Keywords:

extended self; Tablighi Jamaat; clothing; attire; possessions; identity; multi-sited ethnography; Islam; Pakistan 1. Introduction

Some consumer possessions—more than others—have a special connection with one’s self. For instance, clothes have the quality to suffuse their consumers with identity and power (Twain 1905). Particularly from a religious point of view, believers exhibit fervent connections in relation to sacred belongings (Belk et al. 1989). In line with this idea, one question that requires further examination is how do religious possessions relate to one’s identity and what meanings do they inculcate for their owners?

Religious possessions are the result of moral choices made by their owners and have a complicated position in modernity. Modernity affects consumer choice in myriad ways by shaping consumers with varying senses of identity. A large body of literature argues that the shaping of selfhood (or identity) in modernity is inevitably a moral project (e.g., Alexander 2006; Calhoun 1991, 1994; Smith 2003). Even when the path towards identity is individualistic, pluralistic or devoid of institutional intervention, consumer identities are inescapably grounded in a moral shaping that is inextricably tied to the self (Winchester 2008). The self is involved with a web of normative relationships with society and implicated in socially constructed understandings of what is right, wrong and worth living for. Related to this idea, identity in modernity is argued to be an evolving process of ‘becoming’ as opposed to ‘being’ (Dillon 1999, p. 250). Personal identity can gradually transition due to individual experiences and larger sociocultural forces (McMullen 2000; Nagel 1995). The present study aims to substantiate this body of knowledge by prioritising the consumption of religious clothing as the focus of attention, and understanding how it can result from an ever-changing religious, moral self.

Theorists have espoused the idea that religion in modernity continues to provide meaning to many consumers (Edgell 2012; Husemann and Eckhardt 2019b; Iner and Yucel 2015). Religion shapes key narratives that govern individual and social comportment. For example, consumers turn to spiritual solutions such as pilgrimages (Higgins and Hamilton 2016; Moufahim 2013) or participation in religious movements (Appau 2020; Rauf et al. 2019). In this quest for meaning, materiality and spirituality co-exist (Rinallo et al. 2013). For instance, Moufahim (2013, p. 421) concludes that material consumption is inherent to religious rituals and transforms the experiential into the tangible. Further, Husemann and Eckhardt (2019b) note that engagement with the material helps religious consumers transcend beyond geographies, time and life.

While contemporary consumers have been embroiled in attaining spirituality through commercialisation and innovation in religion—including forms of digital religion (McAlexander et al. 2014; Whyte 2022; Yucel and Albayrak 2021)—many religious adherents today practice a form of religion that relies on tradition or relives a utopian past to craft spiritual and pious lives. Prominent examples of such practices include participation in the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage or revivalist Islamic movements such as the Tablighi Jamaat (Husemann and Eckhardt 2019a; Rauf et al. 2018). In such cases, modernity is implicated as a substrate for such spiritual drives as the discomfort with modern ways of living spurs consumers to break away from chaotic state of affairs and concentrate on religious ideals (Rauf 2022; Rosa 2013).

Among these religious adherents, consumption elements play an integral role in maintaining a focus on tradition or attempting to recreate the epitome of historic sacredness (Rauf 2022). Clothing is one such element. Researchers have studied clothing as an integral facet of life that lies at the intersection of consumer choice and religious regulation (Coşgel and Minkler 2004). Clothing is infused with meaning and plays a particular part in forming identity (Coşgel and Minkler 2004; Sandikci and Ger 2010). With this backdrop, I ask what meanings clothes have when they are considered part of the religious extended self? Considering this question is important as specific possessions can have great significance for religious adherents. At the same time, such attire could easily be considered mundane and taken for granted by onlookers. In such situations, contestations may arise that could instigate anxious reactions from religious adherents, as witnessed in the veiling and headscarf debate in Europe and more recently in India (Hass 2020; Mir 2022). Even if they do not provoke ostensible backlash, the lack of acceptability of religious attire in certain settings such as official meetings or public spaces can be the basis of muted consternation as well as a signal of exclusion in what may be otherwise considered diversity-welcoming settings. Therefore, to be a truly inclusive society, it is important to consider what meanings specific modes of dress offer to religious observants.

Previous research has helped us understand how women’s religious attire in the Islamic context is negotiated and what it represents for adherents (Bucar 2017; Sandikci and Ger 2010). While such research remains important, the counterpart gender (male) has been largely overlooked; we are yet to fully understand the meanings associated with men’s Islamic attire and how they are negotiated in everyday contexts.

In this study, I look at how male religious attire is a source of identity meaning for adherents of an orthodox Islamic movement and what challenges these followers face in wearing such attire. I specifically use the case study of the Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan to address the research question. The Tablighi Jamaat is an apolitical traditional revivalist movement that aims to improve Muslims’ religious state. To accomplish this, the group emphasises preaching to Muslims only, to align their lives with traditional religion as it was practised at the sacred time of Islam’s inception. I investigate the research context using three 40-day ethnographic sojourns and 20 in-depth interviews.

I use the theoretical lens of the extended self model proposed by Belk (1988) to help us understand the meanings behind religious attire. The concept of the extended self elucidates how objects, ideas, people and social groups can be considered part of the self as consumers attach special meaning to such entities. In the current investigation, I aim to understand how clothing in its form is embodied to the degree that it becomes part of the extended self.

This article makes three contributions to the extant literature on religious possessions, embodiment and the extended self. First, it redresses a gender imbalance in previous Islamic literature on dress in consumer research and religious studies by focusing on men’s attire. Second, it provides empirical support to Belk’s extended self thesis in the case of religion, particularly Islam. Third, it shows how male attire for a particular Islamic movement develops into a part of the self because of its association with an imaginary, distant religious personality and his legacy.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, I review the existing literature on Islamic attire, which has predominantly focused on women to date. Second, I review Belk’s (1988) conceptualisation of the extended self that provides the framework for this study. Next, I describe the research context and methods for this investigation and briefly mention researcher reflexivity. Then, I detail the findings of this study and discuss their implications for current conversations in consumer research and religion. Finally, I offer a conclusion that sums up this research.

2. Literature Review

The Gender Skew in Research on Islamic Clothing

Religious dress serves as a signifier that helps promote individual identity and maintain ties with social groups (Williams 1988). Regarding the latter, religious institutions may provide the resources, norms and practices that foster adopting certain attire (Riesebrodt 2010). However, particularly in the case of Islam, the connotations of religious attire are not limited to the domain of religion itself; Islamic dress is intertwined with sociocultural and political connotations. Engaging with these issues, consumer research and social science literature have discussed the adoption, lived experience and meanings associated with religious attire. Yet, the conversation to date has predominantly focused on female attire.

Researchers have made the Muslim women’s veil the subject of extensive investigation and discussion (e.g., Almila and Inglis 2017; El Guindi 1999; Hughes 2013; Osella and Osella 2007; Sandikci and Ger 2010; Secor 2002). The veil can be categorised as either the hijab (headscarf) or the niqab (additionally includes the face veil). As a visible mode of consumption, the veil incites controversy and contestation in the public domain and brings with it many different connotations.

Bucar (2017, p. 1) mentions that many people from the West view the veil as a sign of enforced oppression of women (both in its form as a headscarf or as a body covering) that ostensibly demeans them or weakens their status compared to men. Among others, Hass (2020) and Hass and Lutek (2019) have discussed how this understanding of ‘oppression’ resulted in the veiling ban in the Netherlands and Dutch Muslim women taking up the matter as a contest to maintain a distinct Islamic identity and inclusivity in the Dutch populace. In consonance with this stance, Mahmood (2005) contends that the veil is a means to volitionally achieve pious goals to pursue the identity of a good Muslim woman. Additionally, Winchester (2008) finds the hijab is a style of dress that identifies a modest woman and a means through which such modesty is inculcated. Moreover, wearing the hijab can incur opportunities to signal moral and religious understanding (Bucar 2017).

Bucar (2017) argues that wearing the hijab may not just be a fulfilment of religious injunction or to inculcate modesty. The hijab can be donned for social and political reasons, encompassing various wearing styles and designs. For instance, colour choice, brand names and textures are a means to express new fashion and distinguish oneself from others (Bucar 2012, 2017). Bucar (2017, p. ix) notes that when she donned the veil herself, it modified her self-image, how she interacted socially and how aesthetically she understood Islamic clothing. Moreover, as a cultural object, the hijab varies in its meanings and styles across contexts (e.g., it may symbolise acquiescence in Tehran while indicating pious volitional choice in Istanbul). The veil is also interwoven with social class, whereby lower-class women adorn the article in a less fancy manner while upper-middle class women attempt to appropriate the garb more fashionably (Bucar 2017; Sandikci and Ger 2010).

In the Turkish context, Sandikci and Ger (2010) illustrate how the practice of wearing the tesettür (a large headscarf combined with an overcoat) transformed from an ostracised stigma statement to a fashionable modern choice. Abetted by market and political forces, the Turkish attire came into vogue via the support of multiple social actors. Customisation and aestheticisation also helped the article gain widespread acceptance.

Indeed, market and religious logic have spurred much writing on the issue of Islamic sartorial choice. Researchers have explored the paradox of women trying to practice modesty on the one hand and express overt vanity on the other, as observed among Arab women (Sobh et al. 2012). Here, the authors conclude that women balance two distinct needs: the need to abide by Islamic prescription and the need to express beauty tastes.

The issue of logic is also prevalent in tween dress choices in Pakistan, where both the market and Islam are central to choice and manner of consumption (Husain et al. 2019). Visibly identifiable consumption as per market logic, as opposed to its negation in the religious logic, forms a space to creatively navigate consumption practices so as to not disregard both logics and craft new boundary practices that straddle both separately.

Sandikci (2021) made halal nail polish the centre of her investigation to understand the debate between permissibility and impermissibility of consumer goods for Muslims. This context provides an opportunity to explore how market and religious relations shape the consumption and adoption of innovative products in mundane settings. Here, consumer choice is undergirded by the logic of religion as it interacts with the logics of the market, culture and economics. Further, it is complicated by transitory influences of multiple sources of religious authority (including self-proclaimed consumer experts) that govern the apt course of action.

In a study that serves as an exception to the focus on female dress, Gökarıksel and Secor (2017) examined males in two Turkish cities to illustrate how Muslims adapted masculine dress and pertinent practices to shape two very different versions of moral geography in the two metropolitans. Their study highlights the diversity of Islamic and masculinity interpretation and enactment.

Nevertheless, the literature on male Islamic attire remains scant. The present study aims to bolster this pool of work using the extended self framework that is discussed next.

3. Theoretical Framework: Belk’s Notion of the Extended Self

In 1988, Russell W. Belk introduced the notion of the extended self. Belk’s (1988) article has become a cornerstone for subsequent consumer research discussions on materiality, identity, ownership, sharing and consumer relationships with objects. The extended self thesis advocates that we consider our close possessions as parts of ourselves; that is, our belongings are an important contributor to our identities. Belk offers a gamut of evidence to support this premise and proffers that consumers create, express, enhance and reify their sense of being through what they have.

The extended self encompasses physical and non-physical entities. Belk theorises that the extended self also caters for persons, places, ideas, brands and experiences in addition to material possessions (Belk 1988, p. 141). For instance, children, reputation and objects are as beloved to a person as their own self. McClelland (1951) mentions that external objects may be incorporated into the idea of the self if one can deem control over them as they would a part of their body. Hence, personal objects may be considered part of the extended self more easily than other humans (such as friends) since one has more control over the inanimate than the animate. Along the same lines, Belk buttresses McCarthy’s (1984) argument that material things reinforce one’s identity and that identities may reside more in inanimate objects than humans.

The extended self may expand or contract. Using the ideas of Rochberg-Halton (1986), Belk elaborates that as people grow older, the extended self grows as the span of possessions expands, particularly those received as gifts or to which one is related. In this vein, the paper notes that possessions are not only critical for comprising the self but also influential in the development of the self (Belk 1988, p. 141). The article also proposes that conversely, the loss of possessions diminishes the extended self. Citing Goffman (1957), Belk argues that in institutional settings such as military camps or monasteries, when members are stripped of their belongings and provided standardised substitutes, it effaces heterogeneity and increases the self’s sense of group affiliation. Shared consumption symbols enact social loyalty. Hence, possessions can individualise but also antithetically create group association. Similarly, when close loved ones are viewed as part of the extended self, Belk proposes that one grieves when relations die due to a loss of self. Relatedly, Belk notes that the extended self waxes and wanes over time and is not static.

The extended self thesis also argues that one can symbolically extend the self through material items, such as when having a medal or a firearm allows us to feel that we are a different being than when we did not have one (Tanay and Freeman 1976). Moreover, we can relate to a mythic or nostalgic past through possessions (McCracken 1986). Hence, material objects are a means to maintain values across generations and through history. Possessions help us emote, experience and relive.

The experience of using material items also helps them become part of the self. Belk (1989, 2014) asserts that the longer one keeps a possession, the stronger the feeling of attachment to that possession becomes. Further, Mittal (2006) states that items tend to become more ‘I’ over time than when first acquired. This is due to the time and energy spent on such products, which gives rise to special significance. For example, driving a car regularly can enable the car to become like a second skin. Clothes (Solomon 1986) and houses (Jager 1985) are other such examples. Mittal (2006) adds that more expensive and rare possessions are more likely to become part of the self due to the investment (time, money and effort) made in them.

Overall, the extended self may be visually considered in terms of a core central self with concentric circles around it depicting the extended self, showing greater or lesser attachment with the self, depending on how far they are from the centre. Based on how important one’s affiliation to a certain identity is (e.g., nation, family, ethnicity), possessions will correspondingly be closer to or further from the core self.

Next, I examine the meanings religious possessions have for consumers in the literature and how these can be related to the extended self.

The Extended Self Thesis and Religious Possessions in Consumer Research

Religious possessions have important meanings for many consumers. Authors argue that consumers can imbue mundane objects with special characteristics that make them sacred (Belk et al. 1989). Conversely, consumers can strip away the sacredness of certain products, thus making them perceptibly profane. Belk (1992) concludes that the decision to leave behind (sacrificing) possessions in sacred journeys has played a part in advocating the regard for a higher, purposeful calling. Later work has shown how deep affection for certain brands like Harley Davidson and Apple results in a cult-like following for objects associated with these brands (Muñiz and Schau 2005; Schouten and McAlexander 1995). Such brands have the capacity to transform the self due to their specific subcultures and brand communities. In a more traditional, non-commercial context, de Britto et al. (2017) find that a sacred object such as a scapular can be transcendental and extraordinary, not only due to religious belief but also because of the source with which it is associated. Having received the gift of the scapular from a close loved one, Catholic consumers believe this object can protect owners from harm. Hence, the extended self is integrated with the scapular due to its special connection with the gift-giver (e.g., the mother) and one’s close connection with them (also part of the extended self).

Nevertheless, explorations of the extended self in the religious context have been rare. Belk’s paper focused on consumption belongings in a general sense. He argued that the extended self could encompass things one feels attached to, such as the body, internal processes, ideas and experiences, and special persons, places and things. Particularly remiss in Belk’s paper is how religious possessions are inculcated into the self and how their meanings are contested in the everyday. Moreover, another advancement that may be added to Belk’s conceptualisation is the understanding of the process by which adherents can identify with another entity as the extended self. Ostensibly, Belk’s thesis can be expanded to include religious dress if it is consistently worn and identified with. Even though Belk did not initially discuss religious or Muslim consumers while outlining his thesis, it is reasonable to incorporate Islamic dress (such as the loose male dress or female veil) in the extended self thesis’ purview. This is what this paper sets out to examine.

In order to delve into understanding this topic, I now outline the research context and methods for this study.

4. Research Context

4.1. Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan

Born in the 1920s in the British-occupied Indian subcontinent, the Tablighi Jamaat (TJ), literally meaning preaching group, is one of the largest Islamic revivalist movements in the modern world (Reetz 2007). One estimate places the number of TJ adherents at 80 million worldwide (Rauf et al. 2018; Taylor 2009). TJ’s influence is spread worldwide, and its presence is felt in both Muslim majority and Muslim minority countries (Siddiqi 2018; Timol 2019).

Founded on the premise that Muslims were far removed from the teachings of Islam, TJ fashions a distinct method of drawing lay Muslim participants back to traditional religion: a focus on preaching and maintaining an orthodox lifestyle in an attempt to recreate Islam’s heyday in the 7th century (Metcalf 1999). Other defining features of the TJ are that it is apolitical and does not aim to preach to non-Muslims nor intend to convert them (Kabir 2010). Instead, TJ focuses its efforts on bringing the lives of lapsed Muslims closer to Islamic teachings (Timol 2019).

A major component of the TJ program is participant-based preaching missions assembled in small groups called jamaats that travel from one locale to another for stipulated time periods. By virtue of this preaching or dawah approach, TJ aims to revive orthodox Islam at the grassroots level across the world (Ali 2003). Dawah means inviting Muslims to be better practising Muslims (Kabir 2010). One of the major chapters of TJ is based in Raiwind, Pakistan, from where jamaats are routed across the world.

4.2. The TJ Program

TJ emphasises the revival of Islamic traditions as they were practised in the Golden Age of Islam. These traditions, called sunnah (or the Prophetic way), comprise rituals, practices and other entities transmitted intergenerationally from the utopian era to the present day through texts and religious clergy (Rauf 2022; Yucel 2009). Traditions are important for TJ but equally, so is the style in which they are resurrected. TJ elders stress performing tasks such as preaching, eating, sleeping, reading the Quran, teaching, learning, decision-making, observing etiquettes, sharing, caring and worshipping as they were performed in the 7th century. The prescribed texts from which TJ participants read in ritualistic group circles also help educate adherents about how Islam was practised at a sacred time and the virtues of performing traditional Islamic injunctions (Metcalf 1993; Pieri 2021). In terms of consumption, TJ participants are advised to refrain from indulging in the material world and only partake as required.

The sojourns are a critical component of the TJ program. Participants divide their yearly and monthly schedules to devote time to participating in sojourns. These sojourns can last from three days monthly to four months annually. Adherents also participate in international sojourns ranging from seven months to one year. The sojourns serve as a retreat from participants’ busy lives to engage in sacred rituals and lifestyles (Gaborieau 2006). The mosques or masjids play a cardinal role in the TJ regimen, especially during sojourns. Participants travel to and from masjids, practice rituals there, and are advised to maximise their time in the masjid.

5. Research Methods: Multi-Sited Ethnography and In-Depth Interviews

This study is based on a larger study comprising multi-sited ethnographic work and in-depth interview data. Ethnography aims to understand the construction of culture or subculture by observing and recording people’s behaviours and discourses (Arnould and Wallendorf 1994). The approach seeks to understand an insider perspective of experience (emic) and relies on researcher interpretation to make sense of the observations on a sociocultural level (Denzin 1989).

Marcus (1995, p. 96) defines multi-sited ethnography as a method that ‘ethnographically constructs the life-worlds of variously situated subjects [and] ethnographically constructs aspects of the [world] system itself through the associations and connections it suggests among [local] sites’. The underlying tenet of the approach emphasises that the social construction of reality is created at multiple sites (Marcus 1995). In so doing, the approach helps connect micro- (local) and macro- (global) constructions (Ekström 2006). The locations are united by the topic of study (people, places, objects, relationships, etc.), which becomes the instrument of analysis (Marcus 1995). The multi-sited approach can also equate to a theory-driven investigation of connections between locations (Boccagni 2019). Falzon (2016) notes that the effectiveness of multi-sited ethnography implies the limitation of single locations as settings and units of analysis. For the present study, multi-sited ethnography helped me understand first-hand the meanings of rituals, practices, possessions and discourses undertaken by TJ participants. Multi-sited ethnography is pertinent as observations took place at multiple locations while travelling with the jamaats on sojourns. At multiple sojourn locations, I undertook field observation, note-taking and corroboration from other off-site sources to develop understanding.

In-depth interviews enable appreciation from an in situ informant’s perspective of how they behave, feel and communicate with context-related people, processes, events, practices, discourses and materials. In-depth interviews also allow informants to share their own background and relate stories and incidents that may help inform researchers of the sociocultural context of on-site observations and behaviour. In the present case, in-depth interviews allowed me to achieve my research objectives by helping me comprehend informants’ narratives regarding cognitive processes, tensions, choices, meanings, life histories and relevant stories.

6. Research Design, Data Collection, and Researcher Reflexivity

This study is based on observation of and interlocution with middle-class Pakistani TJ participants. This focus was taken to distinguish the participants’ dress from lower and middle-class Pakistanis whose regular attire is culturally similar to those worn by TJ participants.

As a researcher, I had already spent four consecutive months in TJ sojourns in 2012. The four-month immersion period is prescribed by TJ elders as an essential course for Muslims to understand the effort of preaching (dawah) (Ali and Orofino 2018; Rauf 2022). Hence, I was well-versed in the TJ program and was a regular participant in TJ activities when I collected data for this project. I undertake the annual recommended 40-day sojourn. For this particular project, I undertook fieldwork during three 40-day sojourns (in 2014, 2018 and 2020). These included visits to masjids in Sialkot, Hasilpur, Faisalabad, Gilgit, Okara, Haripur, the national TJ markaz (centre) at Raiwind, and regional TJ centres in Lahore, Faisalabad, Gilgit, Okara, Rawalpindi and Bahawalpur. Additionally, I observed participants at retail outlets, public transport terminals, public vehicles and their local masjids.

Keeping in view the closed nature of the religious community that I studied, research ethics was instrumental to the integrity of the investigation. I obtained my university’s ethics approval for the project and disclosed my identity to sojourn participants as an academic researcher. The 40-day periods provided sufficient time to immerse and build connections with my other sojourn participants, who I had never met before the start of the journey. Being visibly identified as practising Muslim (through dress, cap and beard), I was able to easily appease jamaat members of any apprehensions of being observed. Three sojourns help crystallise my findings and achieve theoretical saturation. Moreover, as an ethnographic observation participant, donning such attire helped me reflect more closely on the meanings associated with wearing such clothing. To create distance from the research context during analysis, I discussed findings and interpretations in detail with three senior colleagues who were unrelated to the TJ. With one Muslim and two non-Muslim colleagues, their views provided useful sounding boards to my participant position.

During the sojourns investigated for this study, as per TJ recommendations, I did not have access to a mobile phone or the internet. However, I did use an audio recorder. I kept a diary to inscribe observational data, usually as soon as the opportunity presented itself.

In addition to ethnographic observation, I carried out 20 in-depth interviews with TJ informants from the Pakistani upper-middle class in Lahore who varied in their degree of participation with the movement (from newcomers to long-term participants), age (from 20 to 62 years) and professions (students, professionals, small and large business owners, etc.). I interviewed participants during the sojourns in their local masjids or at homes. The interviews ranged from 45 min to 279 min, with some informants interviewed multiple times. The names of all informants have been pseudonymised.

The following section will relate the findings from the qualitative data collection for this project.

7. Findings

The findings for this study are organised as follows: what constitutes religious attire in the TJ (using ethnographic data); how changes in appearance occur as one is involved with the TJ; how TJ-related appearance creates tensions and how these are negotiated at home and at work; and, finally, what meanings TJ-related attire holds when it is embodied over a long period of time, that is, becomes part of the extended self.

7.1. Men’s Attire in the TJ

The findings of this study reveal that TJ sojourns are an essential vehicle in creating a distinctive subculture of rituals, discourses and consumption behaviour. I adapt Schouten and McAlexander’s (1995, p. 43) explanation to describe a subculture as an identifiable subgroup of society that is formed on the basis of a shared commitment and/or beliefs with its own social structure, ethos and mode of expression. My ethnography reveals that while consumption practices in the subculture of the TJ overlap with the rest of Pakistani society (eating, drinking, sleeping, using the toilet, wearing clothes, etc.), these practices differ from cultural norms in their style of consumption. For instance, what separates eating normally and in the TJ is the way this activity is performed (e.g., TJ meals are eaten while sitting on the floor with the food and utensils placed on top of a sheet; participants use two fingers to eat while sitting in a specific stance). In the case of TJ, specific style is an outcome of the ideology of doing an action to please Allah and the way that is pleasing to him; that is, the Prophetic way or sunnah. This style is evident in clothing that I explain now.

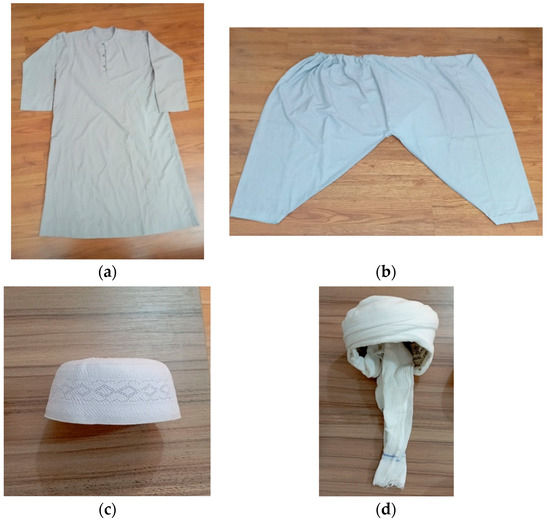

Strictly speaking, Islamic law mandates men to cover their bodies only from the belly button to below the knees (Shakona et al. 2015). However, from my notes, I observed that the TJ attire, which is commended by traditional Islamic scholars and clerics (who TJ participants hold in high regard), comprises a loose shirt down to the knees or longer (called the kameez in Pakistan or jubba in Arab countries)1 and loose pajamas (called shalwar). The pair of top and bottom is known as the shalwar kameez (see Figure 1a,b). This attire is meant to present a modest appearance that hides the physical outline of a person. No specific colour or pattern for the garb is advised. However, some of the most stringent TJ participants, including many seniors and elders, are seen to wear plain white clothing all the time. This is in accordance with a hadith (narration of the Prophet ﷺ) in which preference (but not compulsion) for white clothing is mentioned: ‘Wear white clothes for they are purer and better, and shroud your dead in them’ (Zaʼī et al. 2007). The other part of the TJ attire is the head covering in the form of a skull cap known as the topi in Pakistan and the kufi in Arabia (see Figure 1c). More senior TJ participants also continuously don the imamah or turban (see Figure 1d). The head covering via the topi or imamah also form part of the sunnah. The usual simultaneous occurrence of a triad—long beard, shalwar kameez and topi—is an indicator for lay people that the incumbent has turned into a more religious person.

Figure 1.

(a) Example of a kameez or jubba (source: author notes); (b) Example of a shalwar (source: author notes); (c) Example of a topi (source: author notes); (d) Example of an imamah (source: author notes).

7.2. First Signs of Change in Appearance

As participants increase their activity in TJ, they often incur a discernable change in physical appearance. They usually stop shaving their beards, an act carried out as a sunnah. The other act of appearance that draws attention is continuously wearing the shalwar kameez. Less religious Pakistanis dress up in the shalwar kameez occasionally as a cultural norm. For instance, they will wear it on Fridays, the day for special congregational prayer, or on special events like marriage ceremonies. However, regularly wearing the shalwar kameez is an act of ostensible religiosity. Moreover, the difference between wearing the garb out of cultural respect and as a sunnah is the pajamas usually reach below the ankles in the former, and are kept above the ankles (as prescribed in hadith to avoid arrogance) in the latter. Newcomers to TJ sojourns will also wear the shalwar kameez in the previously described cultural normative style or Western clothes such as jeans and a t-shirt. For instance, one student newcomer in my jamaat, Anwar, donned a bright yellow shalwar kameez whose shirt was short (reached above the knees), had the shalwar reaching below the ankles, and had significant embroidery and fancy design elements on it. Such attire would stand out as an anomaly in TJ circles because, as per TJ norms, the shirt should reach below the knees, the pajamas above the ankles, and yellow is an ostentatious colour.

To fit in with the group, first-time participants of a jamaat will don the shalwar kameez even if they are not accustomed to it previously. For instance, one of my sojourn cohort members Shameer, a 19-year-old motor mechanic, was a newbie and did not even own sunnah attire before he joined the jamaat. He had especially borrowed the shalwar kameez for our sojourn:

Shameer: I have decided to change (the style of my clothes from now on) … these (clothes that I am wearing) aren’t my own clothes. They belong to my brothers.

Interviewer: Where are your own clothes?

Shameer: I use pant shirt. I have never worn shalwar kameez. But now I will get it made (when I return) at home.

I conducted the interview with Shameer in the second half of the 40-day sojourn. By this time, Shameer had decided to switch to more orthodox garb upon completion of his time in jamaat.

7.3. Initial Contestations with Family and Colleagues Due to Changed Appearance

In Pakistani society at large, the religious are stigmatised (Alam 2012; Amir 2005). Based on outward appearance, this stigmatisation deems maulvis (or those with a religious appearance similar to Islamic scholars) to be problematic. A general criticism is the extraneous time and effort spent in religious activity, which is deemed unnecessary. Less religious Pakistanis believe sacred work takes away time and effort from worldly activities, roles and responsibilities. Maulvis are thought to be poor in breadwinning, worldly progress, education, occupational skills, money and prestige. They are also generally opined to be inconsiderate towards their families. Apart from mundane stigmatisation at the workplace and homes, maulvis are stigmatised in the media run by elites (see Alam 2012; Amir 2005). Press pieces also show that the term maulvi has changed meaning from one of respect to stigma. This situation has been exacerbated by political events around the world at the turn of the century (9/11 attacks, Danish cartoon controversy, etc.), after which the media has portrayed religious people as violent, curtailing liberalism and imbibing an Orientalist doctrine (Hughes 2013; Said 1978).

Hence, family members who are unaffiliated with TJ are disconcerted when a relative decides to spend time with the movement or returns from a sojourn. Talha, a medical college student, talked about how his family resisted his changed outlook when he started spending time in TJ:

Yes, at the start … they (family) did comment a bit … for example at a walima (wedding event), they said take off the topi … or that now you have finished praying your namaz (act of worship), drop your shalwar below your ankles … it looks bad, it looks very weird … they would say things like these.

The stigmatisation stems from stereotyping all religious persons similarly based on their outlook. A fine point here is that Talha is singled out for his style of appearance rather than his possession of shalwar kameez per se. As noted above, family resistance usually occurs when other family members do not have a religious background. In families where there is already connection with traditional Islam, these contestations do not manifest.

Another form of contention often occurs in the workplace. TJ employees often face the problem of winning the struggle for acceptance of a different guise, particularly where work policies are stringent. As Salman, a university professor, relates in his interview, corporate culture defines certain etiquettes and norms that prohibit sunnah attire:

The corporate world has its own set of social norms. Tabligh (work of calling to Allah) also changes your lifestyle and your norms. And so generally it appears … that the corporate world will not tolerate your going away from norms. Any work which involves very high levels of commitment generally is very intolerant for deviation. So an example can be a simple thing as clothes. In the corporate world, at a senior level, to wear shalwar kameez is just not acceptable. It just cannot be done.

The issue of clashing norms is evident in Salman’s quote. In Pakistani society generally, lack of inclusivity remains a problem for those who desire to sport religious attire. Hence, TJ participants are often faced with the dilemma of keeping their jobs and observing office rules or sacrificing their jobs to abide by sunnah. The next section explores this dilemma.

7.4. Consequences of Continued (or Lack of) Persistence to Wear TJ Prescribed Attire

TJ participants who persist with wearing sunnah attire either win over their social circle or end up changing their social circle to maintain TJ etiquette. I heard several stories during my interaction with participants relating how certain people had left their jobs or made career decisions based on whether they could practice sunnah. Tanveer, formerly a corporate head at a television channel, relates his story in the following excerpt:

When I got sick, I got a clear message that I was probably not welcome. Because nobody came and attended to me, nobody asked me. They probably thought I was making it up. But people who came and met me were obviously people from the mosque, and my Tablighi saathis (companions). I decided to leave the job then. The moment I got well, I got to the office (and said to myself) that this is the last time I am going to the office, and I wore my normal clothing: my shalwar kameez and my imamah. I went to the office and everyone was looking at me … you know, look at, look at the way he is dressed. And there were people talking behind me. But I was there for just that day. And I told them, and I said today is my last day in this office, and I will not return. Not to the office and not to this profession Insha’Allah (God willing).

Many of my informants claimed the change to move to sunnah attire permanently came after spending four months in jamaat. While in the jamaat, no specific instructions to abide by a certain dress code are disseminated. However, the continuous inhabiting of the jamaat subculture helps inculcate a sensibility that appreciates the importance and virtues of following the sunnah. While this is akin to Schouten and McAlexander’s (1995) observations when they wore the Harley Davidson biker attire to fit in their subculture, for TJ participants the attire has added significance, as I will explain later.

In my interviews, participants who did not have prolonged exposure to TJ and its principles at the time told me they swapped between sunnah attire and Western clothing as per the demands of the situation. For instance, property dealer Muqaddam told me that when he had spent 40 days only (i.e., this was before his four months), he used to interchange between the different styles of clothing:

Interviewer: What about wearing shalwar kameez regularly (after your 40 days)?

Muqaddam: Both things were there. Both things went together–pant shirt sometimes, and shalwar kameez.

However, once he had completed his four months in jamaat, Muqaddam switched to shalwar kameez permanently. Recent university graduate Hammad, who spent 40 days in jamaat, was able to sustain his TJ clothing for a short period of time before returning to shirts and pants to yield to his new job norms:

Yes, after coming back from chilla (40 days in sojourn) I wore shalwar kameez for like two or three months and I wanted to keep a beard too, but it wasn’t growing properly so I shaved it. My mother also said that keep it when it starts to grow properly; don’t keep it right now. I would wear shalwar kameez consistently and a topi also—even in university after coming back from chilla.

But since I have been in Islamabad, it has been about a month since I have left wearing it … because my job is in marketing.

Marketing, in particular, is important here because it represents the face of a company. Marketing professionals are expected to be presentable as per company standards so they can attract more clientele. In the view of many corporations, religious attire can deter potential clients as it indicates a lack of work ethic or professionalism.

7.5. Sunnah Becoming Part of the Extended Self

7.5.1. The Ummah as the Extended Self: Clothing as a Form of Social Imaginary Identity

For many participants, the four-month sojourn seems to be a rite of passage towards a new identity. An indicator of this identity is that the sunnah attire becomes a constant feature of the participant’s makeup to the extent that participants are willing to take tough decisions such as leaving their jobs to prevent compromise with the extended self of which the shalwar kameez and topi are integral. More senior TJ participants also don the imamah and consistently wear white clothing. For instance, I observed that senior participant Salman, who has spent time in numerous 12-month, 7-month and 40-day jamaats and is now a resident at the headquarters in Raiwind, predominantly than not wears the white imamah along with white shalwar kameez. He also wears this clothing at his university workplace, which is considered odd among his colleagues and students. Salman reports that he has 10 white shalwar kameez in his collection; they are plain but made of high-quality material, so they are presentable and durable.

The durability of the material is an important factor. Several of my informants reported that they would not switch to a new piece of garment unless it tears or fades. As summer material is lighter than winter material, it usually does not last and needs to be replaced every year or two. For instance, Ismail, a garment trader and a senior TJ participant, explained his clothing choices:

Interviewer: Do you buy (sunnah) clothes every season or are they used more than one season?

Ismail: I get one or two new ones in summers, but in winters I still use very old clothes … In fact, I have some clothes that I have been using for over 20 years … I got two pairs of clothes in 1995, I still wear them … But in summers, because the clothes wear out quickly … cotton fades in colour and gets torn, I need to get new ones. Otherwise, in winters I have not made new clothes for a while.

Like Ismail, other informants also mentioned retaining clothing as long as it lasts. This is supported by TJ participants’ quest for simplicity in their clothing and not changing clothing unless required. TJ elders advise the sunnah norm of simplicity in their sermons. The garb TJs wear is not ostentatious but usually of a single colour without adornments. Such attire may stand out to outsiders in their social class because of its style; nevertheless, in TJ circles sunnah clothing is considered simple because it is affordable and commonly worn by lower classes. Thus, the garb diffuses class differences since it is the common man’s attire. Relatedly, TJ participants are not particular about brands, even if they were previous to joining the movement. Indeed, many have their clothes stitched by an unknown tailor. For instance, Muqaddam relates the following:

Interviewer: (After your four months) was there a change in (preference for) brands also?

Muqaddam: Yes, there definitely was a change … when you walk (travel) with the jamaat, simplicity does come into a person. So then there is a change in (preference for a) brand. When you embrace simplicity, then the branded things finish.

Interviewer: For example, what brands did you use before that you do not use now?

Muqaddam: For example … clothes. Before we would wear Levis and get clothes stitched from Dandy (a renowned tailor). It was like that, getting clothes from nice outlets and then getting them stitched. But when you embrace simplicity, then you say let’s just get them stitched from him (the ordinary tailor).

Unbranded clothing ensures the attire is synonymous with the Prophet’s clothing, which was bereft of branding. Brandless, simple clothing also relates to the common man. This ties into the feeling of unity with the Prophet’s ummah or nation. In my observations, I felt that TJ participants could relate to other participants wherever in the world they met, even if they did not know each other previously. This was by virtue of identification of their shalwar kameez and topi. Unfamiliar TJ participants connected with each other regardless of language, social class or other demographic barriers. The TJ movement’s universality in its practices and emphasis on brotherly bonding enabled other Muslims to become part of the self. However, this feeling also suffused to Muslims generally. As a preaching movement, TJ participants were expected to reach out and be nice to everyone they met. This was invoked by a frequently mentioned hadith:

You see the believers as regards their being merciful among themselves and showing love among themselves and being kind, resembling one body, so that, if any part of the body is not well then the whole body shares the sleeplessness (insomnia) and fever with it.(Kandhalvi 2003)

In line with this hadith, TJ work emphasises the Muslims as one body, which is a point that directly relates to the thesis of considering the ummah as the extended self.

7.5.2. The Noble Figure as the Extended Self: Clothing as a Replication of Sacred Celebrity

The question is how does the religious extended self develop during the four-month period in jamaat? My involvement in the sojourns shows that the social subculture within the jamaat plays an important role. However, perhaps more importantly, the discourse and practices within the jamaat are critical in inculcating the change towards the extended self. The four months in jamaat are a prolonged period in which rituals and dialogues that emphasise the Prophetic life are carried out. The everyday reading of the prescribed texts (Fazail-e-Aamal and Fazail-e-Sadaqaat) that comprise Quranic verses, hadith and corresponding explanations mainly relate the virtues of obeying the Prophet and his lifestyle. For instance, one of the Quranic verses often mentioned in the text and other rituals advocates the argument:

Say (O Prophet): If you really love Allah, then follow me, and Allah shall love you and forgive you your sins. Allah is Most-Forgiving, Very-Merciful—Al Quran 3:31(Usmani 2010)

This verse essentialises that love with the Creator and his forgiveness depend on following the sunnah or the Prophetic way. In this vein, TJ discourse accentuates that the way of practising Islamic rituals is as important as practising them per se. For example, TJ elders discourage the use of innovation in the jamaat for preaching as it goes against the sunnah. Hence, the use of cell phones for dawah is condemned.

Related to the emphasis given to the Prophetic way, one ritual that is part of the daily routine in jamaat is the ailaan or announcement. The words of the ailaan are prescribed, repeated, taught and practised verbatim by all participants in discussions. The ailaan also signifies the importance of the Prophetic effort and the manner in which it should unfold. The words of the ailaan are as follows:

Brothers, elders, and friends: please listen to an important announcement. Allah (the pure) has kept my, your, and the entire mankind’s complete success in complete religion. Religion comprises fulfilling Allah’s commandments as in the way shown by the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. Complete religion will come into all our lives through the way of the effort of the Prophet ﷺ, which due to the finality of Prophethood is incumbent on each of us. Regarding this, there will be a talk after the supplication/worship. Everyone is requested to attend. InshaAllah (God willing) it will be very beneficial.

Known as the complete dawah (invitation), the ailaan summarises the spirit and essence of all the TJ rituals. Salient in the announcement is the connection of success with religion, and religion not only being an attempt to simulate the Prophet but the process of bringing religion is also that of the Prophetic way and the responsibility of each Muslim. With the significance of the Prophet’s ﷺ personality an overarching theme of all discourse and practice within TJ, it is not surprising that over the course of 120 days of continuous repetition of this message, TJ participants engrain within themselves a special connection with the figure of the Prophet. Hence, it can be deemed that the Prophet ﷺ becomes part of the extended self where every action, sign and discourse is related to the personality becomes an integral part of the participant. This aligns with the proposition that people and ideas can be part of the extended self.

An indicator that a possession is part of the extended self is the hurt felt when the extended self is injured. In our case, we see that TJ participants consider the personality of the Prophet ﷺ as part of the self when any simulation of the figure is disrespected. For example, Mustafa, a director at an electronics family business, felt aggrieved when he returned from his four-month sojourn to see his family members complaining about his change in appearance:

Interviewer: Have you worn shalwar kameez since the start or…?

Mustafa: No, I started wearing it after the four months (sojourn).

Interviewer: How did people look at you and perceive you at that time?

Mustafa: They did give their opinions and were shocked to see the change.

Interviewer: So what do you feel when people objected?

…

Mustafa: It pinched me a lot. My eldest brother had his mehndi (wedding) function (event) and we had just come back from the four months. So at the start it pinched a lot and I remember I cried from inside.

Interviewer: Really? Why?

Mustafa: (In reaction) They commented ‘what is this that you have started?’ … they said that religion should be to an extent and not to such a large extent.

The emotion of bereavement indicates how clothing style has become part of the self. Notably, this happened after the four months sojourn, which, as stated earlier, is when the discourses regarding the exaltedness of the Prophet ﷺ are constantly repeated. Hence, the clothing style is an imitation of the Prophet, and when the style is insulted, the Prophet ﷺ is effectively insulted and, in turn, the extended self is insulted.

An excerpt from Musab’s interview highlights another variation of the aforementioned injury. Musab relates the story of his uncle and when he started wearing the sunnah attire and sporting the beard. The reaction from his uncle’s father (i.e., Musab’s grandfather) was repulsive and hurtful to Musab’s uncle, but he justified the change with a rhetorical, poignant question that the elder could not rebut:

Musab: (When TJ participation) changed Chachu (paternal uncle) … he also started keeping a little beard. Dada (paternal grandfather) told him, ‘trim your beard, what are you doing?’ Chachu (paternal uncle) knew how to respond the right way. He said, ‘Father, when people used to compare your son’s looks to Rock Hudson you used to get very happy, but now that he looks like Hazoor (Prophet Muhammad ﷺ) you feel sad?’

While this quote indicates the repulsion of an onlooker specific to the beard, the beard is part of the triad that comprises semblance to the Prophet ﷺ. Hence, it denotes a broader problem with religious guise. Insulting the likeness of the Prophet ﷺ is injurious to the one bearing it because it is contained within the extended self, which provokes various sentiments; for example, in this case, anger. Chachu’s question brings to the fore the issue of values. Since some part of every Muslim honours the Prophet ﷺ, the contrast of the values foreign to Islam and native to it serve as a reminder to the disparager of one’s own Muslim identity. Hence, Chachu’s retort prompts Dada to honour the status of the sacred image of the Prophet ﷺ, whose exaltedness is unquestionable for any Muslim.

7.5.3. The Purpose as the Extended Self: Clothing as a Uniform for Sacred Work

The sunnah attire also signifies a connection with sacred work; that is, the work of the Prophet ﷺ. In TJ circles, elders and participants incessantly reiterate how the work of preaching is incumbent for every participant and for this, time, wealth and energy has to be spared. To this end, TJ participants often narrate the Quranic verse in sermons:

Say (O Prophet): This is my way. I call (people) to Allah with full perception, both I and my followers.—Al Quran 12:108(Usmani 2010)

The above verse explains that it is the responsibility of each follower of the Prophet ﷺ to call others towards Allah and religion. While imitating the Prophet in other respects is also encouraged, TJ ideology stresses that if each Muslim gives due credence and honour to the work of dawah, other parts of the religion will be revived. Since this work requires dedication and sacrifice, it is in very serious and senior participants that the work is embodied in the extended self such that they are willing to prioritise the work over all other commitments. While on a preaching sojourn, Tanveer relates how he explained this stance of following the Prophet in entirety to a group of people from another sect:

I said, look, you and I believe that Muhammad ﷺ is the last prophet, don’t we? They said yes … Then I said, I said prophets are meant to be followed, and followed not in piecemeal, but in completeness, and I said don’t you think it is important? They said yes. I said do you see me visibly as a follower of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ because I am wearing an imamah, I’m wearing this attire, right? They said yes, pretty much so. I said this is it. Whoever is following the prophet, he is on the right lines.

Tanveer’s quotation only highlights how dress is actually a manifestation of a partial emulation of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, and since he was on a preaching mission, it implies the work is also a cardinal facet of following the Prophet. Hence, the significance of the Prophet’s work is not lost on TJ veterans who give years of their lives to carry out the work and sacrifice work and family life in the process. Thus, the TJ guise is emblematic of the work of TJ. Aslam, a plastic surgeon and TJ senior, depicts this stance in the following quote. While on a jamaat to Brazil, he responded to a non-Muslim Brazilian’s question stressing the relationship between dress and the work:

We were in Brazil dressed in sunnah attire. One non-Muslim asked us, ‘Why are you dressed like this?’ I said, ‘this is the attire of our Prophet and we like to imitate him’. He said, ‘I know that. But why are you dressed like this? You are not Prophets.’ At that moment, it struck me and I replied, ‘we are not Prophets, but we are doing the work of the Prophet and because of that we have to also resemble the Prophet’.

The shalwar kameez is a uniform for TJ’s work, just as a policeman’s outfit would be for a traffic policeman to perform his duties. Without the uniform, people at a traffic junction would not obey the officer. Similarly, people would probably not entertain the preaching of a TJ participant seriously if he is not in the proper attire. Hence, it can be said the work and the uniform go hand in hand.

Some informants, and I myself, felt the sunnah clothes and beard engrained a higher sense of responsibility and status in participants. Because of the attire, people looked up to them and expected good from them. I often met people in preaching tours who appreciated the work TJ participants were doing, even though they were not able to take part themselves. Hence, the responsibility of the attire and its connection to a noble figure and the related work made it more difficult and shameful to sin.

8. Discussion

This article investigated how a style of clothing can develop into the extended self of TJ participants. The findings show that the path towards sunnah attire becoming a second skin for TJ participants is non-linear and shaped by social pressures emanating from their families and workplaces. However, the four-month sojourn seems to be a rite of passage (see Section 7.5.1). It is in this prolonged continuous time in the TJ subculture that participants’ understanding of the effort of preaching grows. TJ members develop a sense of self for loosely fitting long shirts and pajamas and some form of head covering. This evolution is interlaced with the participants’ advancement towards their version of piety, comprehension of their place in the global Muslim community, attachment to the noble figure of their Prophet, and shouldering the responsibility of the work of tabligh.

Contributions

This paper has aimed to contribute to existing conversations in religious consumer research in a few ways. First, this article shifts the existing emphasis on Islamic female attire in the literature towards men’s attire. While female attire is a charged subject that has been under scrutiny in global discourse for a number of sociopolitical reasons, this article notes how male Islamic attire can also be a source of sociocultural contestation as religious adherents try to practice the ideals of a pious life. The gender angle plays out differently in the case of men, as males are not as restricted in terms of religious prescription and have a distinct role in the TJ. Men are required to follow in the footsteps of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ more saliently, which brings its own struggles.

Second, this research provides empirical support in the context of religion to Belk’s (1988) extended self thesis. The concept of the extended self has received tremendous support over the years across disciplines in consumer research. However, religion has remained subjugated in this conversation. This is a gaping caveat since religious practice and sacred objects have deep emotional and experiential dimensions. Hence, we see in this research using the South Asian context of Pakistan that there appears to be a strong capacity for sacred objects and figures to become part of the extended self. This paper adds to Belk’s concept by explaining the various ways religious entities can be identified with the self.

Third, this paper shows how male attire in an orthodox Islamic movement develops into a part of the self because of its association with a distant religious personality, his legacy, and the Muslim nation. The conceptualisations of the extended self with regard to historic personalities and work were missing in the original thesis. More explicitly, a dress code associated with simplicity brings into the extended self a feeling of oneness with the ummah. Moreover, TJ participants consider the shalwar kameez an extension of the self as they consider the imitation of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ and his work to be their own selves and work. A certain identity is imbued in this goal, with adherents trying to mimic the lifestyle of the holy person and the purpose for which he came. The shalwar kameez not only underscores emulation in terms of materiality but also functions as a symbol of brotherhood, piety and responsibility. Moreover, due to these factors, religious clothing becomes an embodiment for devout TJ participants such that they do not think they can don any other form of dress.

Thus, this paper articulates that possessions in the religious sense do not attain the status of the extended self per se, but do so because they are associated with another being that becomes part of the self. We can use Mittal’s (2006) idea of the ‘I’ as a signifier of the self for understanding. The reason TJ participants refrain from choosing particular brands is that the garb they wear is not used to express and signify the ‘I’ to signal material value. Instead, the attire signifies different entities; that is, the Prophet and the work of TJ. Hence, extending Belk (1988), we see that no particular article of shalwar kameez becomes part of the self; however, the form of attire is something that is part of the self since it resembles a noble figure. Hence, I propose that style of attire rather than attire per se can become part of the extended self. While participants could wear clothes of varying colours, designs or even brands and even replace old ones, the form of the garb remains loose as per religious prescription.

In a talk, Mahmood (BAK basis voor actuele Kunst 2009) tries to explain the injury caused by the blasphemic cartoons emanating from Denmark by reasoning that orthodox Muslims contested those images because they deeply identified with the Prophet ﷺ. On 30 September 2005, 12 cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ in a satirical fashion were published in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten (Lægaard 2007). The cartoons were offensive and insulting to many Muslims, which resulted in global riots, violence and even killings (Battaglia 2006; Post 2007). In the present investigation, we see the reaction to a similar offence (although less severe in degree) when the appearance of Musab’s uncle, Mustafa, or Tanveer was criticised. While this reaction was not violent and can be interpreted as culture shock, it did arouse sentiments like in the Danish cartoon controversy due to similar reasons. This hurt was due not only to criticism of adherents’ own beliefs or lifestyle, but it was a blot on the guise of the Prophet ﷺ (Asad et al. 2013; Mahmood 2013). When the embodiment of the Prophet ﷺ is disgraced, the (extended) self is disturbed. This is another instance that supports Belk’s reasoning of one grieving the loss of a loved one. The difference here is that the loved one is a distant, historic personality that lived in Arabia.

Adding to Belk’s theory, this study shows that the (style of) possession grows over time into the extended self. It is a process; it does not come about spontaneously. The regular wearing of sunnah attire engrains a sense of identity in the self. I note that if religious possessions are to become part of the extended self, then this process is subject to the life course of religious change in participants. The TJ regimen of sojourns is a means to accomplish this, where a ‘safe’ space for regularly wearing sunnah clothing helps embodiment. Moreover, TJ discourse and practices indirectly reinforce the significance of the attire by idealising the Prophet ﷺ, crafting a sense of purpose for life and being united with the ummah. Setting aside conflicting ideas of the self in a noisy world, the TJ program allows one to focus their energies towards fulfilling Allah’s command and trying to replicate the Prophet ﷺ. For TJ travellers, the embodiment of attire can be contrasted with the lack of embodiment of places. In sojourns, necessary belongings like clothing are continuously with oneself for which one develops a sense of self; however, one develops no sense of attachment to the places visited as one is always in transition in sojourns.

Mahmood’s (2005) study also shows that Islamic veiling brings about shyness within its female subjects who, over time, become accustomed to wearing the cover so much that they feel uncomfortably shy not wearing it. Hence, certain practices can induce moral capacities. In Islam, such practice is not only virtuous itself but also a means to virtues. This helps connect inner and outer spirituality. Thus, in the case of TJ, the sunnah dress is not just an object representing modesty; it is a route to personal development and piety. Hence, stigmatising personal clothing cannot only scar one’s religiosity (Sandikci and Ger 2010) but can also restrict one’s right to becoming religious (Bucar 2012). Moreover, in the current case, participants do not aim to just live pious lives but purposeful pious lives. The goal of participants is not only to achieve virtuousness but also to spread piety, which in itself is a virtuous act.

Another advancement to Belk’s (1988) thesis is that the formation of the extended self is dependent on other social forces or relations. A possession’s path to becoming part of the extended self can be hampered if other pressures (like work or family) are disapproving and the participant is still nascent in his religious career. However, participants who become firm in their beliefs are able to chart their own life course based on religious principles. Furby (1980) espouses that we build a firmer sense of self by learning to effectively control the material in our environment rather than being controlled by it. This aligns with a frequently narrated TJ saying that if a TJ participant does not preach, they will be preached to. We see that unless participants take a firm stance, they accede to living by others’ ideals.

9. Limitations and Future Research

This research is not without limitations. As noted earlier, social factors help or hinder in making the extended self. While this study identified family and the workplace as important factors in shaping the self, future research could scrutinise in more detail how family composition, religious upbringing or friendships are important in influencing participants’ lifestyle choices and religious involvement. Additionally, future examinations could focus on how different kinds of work (family businesses, multinational corporations, small businesses, etc.) and positions in related organisations (junior versus senior) help or hinder the adoption of TJ consumption norms.

Moreover, this research looked at the particular context of an Islamic orthodox religious movement and how a related possession shaped the self. However, future research could investigate other religious movements from Christianity, Judaism or any other religion and how particular material consumer items (clothing or otherwise) can become associated with the self. Within Islam itself, other religious movements, such as the Jamaat-e-Islami or Muslim Brotherhood, could be studied to understand sacred consumption and the extended self.

Dress is a part of a network of other parts of the TJ identity. While this particular investigation focused on attire, future work could study other consumption facets, such as eating style, gifting or food preparation, and how they help develop the extended self.

10. Conclusions

Modernity brings myriad choices of moral pursuits resulting in an array of possible identities. The TJ, in the context of Pakistan, represents a peculiar strand of the diversity of possible Islamic choices in modernity. Hence, this article exhibits the variegated nature of Islamic interpretation and identity, which differs in accordance with social, political and cultural conditions (Iner and Yucel 2015).

With a focus on preaching to the Muslim community, TJ adherents aim to revive and relive a utopian historic past by following the style of the sunnah. This distinctive regimen creates a particular self that manifests itself in specific forms of consumption, one of which has been explored in this article. Consumers are aided in their vision to reenact traditional Islam via clothing consumption. Therefore, consumption is part and parcel of identity formation.

Additionally, this paper illustrates that the concept of the extended self can be advanced usefully in the religious context. Nevertheless, in this regard, we see some additions to the original extended self thesis Belk proposed. This study shows that personal identities are evolutionary, as are the consumption practices associated with them. This article unravels the processual yet reciprocal relationship of one’s belongings with one’s religious trajectory. Relatedly, we also see the hardening or softening of the extended self as tied to these possessions. As such, possessions become part of the extended self, they come to be imbued with deep emotions and meanings for consumers and are inextricably tied to one’s religious trajectory.

Moreover, identity formation through the extended self results from a continued investment of time and effort to live out a specific TJ vision. Hence, we see that a vision can help develop the extended self.

Contrary to the sociopolitical nature of attire that goes against the Western paradigm discussed with regard to female Islamic attire, the focus on TJ male attire is more about crafting a specific identity that emulates distant celebrity; that is, Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. Hence, this article also extends the notion of the extended self from prior notions of objects, persons and places to more abstract concepts removed by time and space. As clothing becomes a part of the self, like a second skin, religious consumers feel an increase in responsibility towards what the clothing represents; that is, historic celebrity, nation and religious work. The meticulous nature of emulation through clothing and relatedly religious practice helps embody a certain style in the extended self that allows for nostalgia and affinity with distant, abstract entities.

The process of extended self development is abetted by the institutionalised nature of TJ doctrine and its rituals. In particular, TJ sojourns play an important role in the formation of the extended self. Sojourns allow the time and space to craft distinct identities in addition to resources such as discourses, community and rituals. Therefore, this article shows how the extended self requires a sustained environment for its grooming. In sum, this article illustrates that well-defined identities are a product of particular sustained conditions and consumption practices in modernity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel (HREAP) F of University of New South Wales (protocol code: HC 126061—1 November 2012).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | The slight difference between the kameez and the jubba is that the kameez has long slits on the sides reaching the waist, while the jubba does not. |

References

- Alam, Masud. 2012. Na Ker Maulvi. Dawn. Available online: http://www.dawn.com/news/767626/na-ker-maulvi (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. 2006. The Civil Sphere. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Jan A. 2003. Islamic Revivalism: The Case of the Tablighi Jamaat. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 23: 173–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Jan A., and Elisa Orofino. 2018. Islamic Revivalist Movements in the Modern World: An Analysis of Al-Ikhwan Al-Muslimun, Tabligh Jama’at, and Hizb Ut-Tahrir. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 31: 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almila, Anna-Mari, and David Inglis. 2017. The Routledge International Handbook to Veils and Veiling. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, Ayaz. 2005. Understanding the Maulvi Point of View. Dawn. Available online: http://www.dawn.com/news/1072992 (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Appau, Samuelson. 2020. Toward a Divine Economic System: Understanding Exchanges in a Religious Consumption Field. Marketing Theory 21: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, Eric J., and Melanie Wallendorf. 1994. Market-Oriented Ethnography: Interpretation Building and Marketing Strategy Formulation. Journal of Marketing Research 31: 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, Talal, Wendy Brown, Judith Butler, and Saba Mahmood. 2013. Is Critique Secular?: Blasphemy, Injury, and Free Speech. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BAK basis voor actuele Kunst. 2009. Saba Mahmood—Moral Injury and Secular Law: The Danish Cartoon—Discussion. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgvG65tHkPk (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Battaglia, Adria. 2006. A Fighting Creed: The Free Speech Narrative in the Danish Cartoon Controversy. Free Speech Yearbook 43: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 1988. Possessions and the Extended Self. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 1989. Extended Self and Extending Paradigmatic Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 16: 129–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 1992. Moving Possessions: An Analysis Based on Personal Documents from the 1847–1869 Mormon Migration. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 2014. You Are What You Can Access: Sharing and Collaborative Consumption Online. Journal of Business Research 67: 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W., Melanie Wallendorf, and John F. Sherry, Jr. 1989. The Sacred and the Profane in Consumer Behavior: Theodicy on the Odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research 16: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccagni, Paolo. 2019. Multi-Sited Ethnography. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug and Richard A. Williams. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bucar, Elizabeth M. 2012. The Islamic Veil: A Beginner’s Guide. Oxford: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- Bucar, Elizabeth M. 2017. Pious Fashion: How Muslim Women Dress. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Craig J. 1991. Morality, Identity, and Historical Explanation: Charles Taylor on the Sources of the Self. Sociological Theory 9: 232–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, Craig J. 1994. Social Theory and the Politics of Identity. Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Coşgel, Metin M., and Lanse Minkler. 2004. Religious Identity and Consumption. Review of Social Economy 62: 339–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Britto, Larissa, Olga Pépece, Elisabete Camilo, and Ana Paula de Miranda. 2017. (Religious) Scapular and Devotion: Extended Self and Sacralization. In Latin American Advances in Consumer Research. Edited by Enrique P. Becerra, Ravindra Chitturi, Maria Cecilia Henriquez Daza and Juan Carlos Londoño Roldan. Duluth: Association for Consumer Research, p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K. 1989. Interpretive Biography. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, Michele. 1999. Catholic Identity: Balancing Reason, Faith, and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, Penny. 2012. A Cultural Sociology of Religion: New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology 38: 247–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, Karin M. 2006. 37 The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography in Anthropology and Marketing. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Marketing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, p. 497. [Google Scholar]

- El Guindi, Fadwa. 1999. Veiling Resistance. Fashion Theory 3: 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, Mark-Anthony. 2016. Multi-Sited Ethnography: Theory, Praxis and Locality in Contemporary Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Furby, Lita. 1980. The Origins and Early Development of Possessive Behavior. Political Psychology 2: 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaborieau, Marc. 2006. What Is Left of Sufism in Tablîghî Jamâ’at? Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 51: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1957. The Characteristics of Total Institutions. In Symposium on Preventive and Social Psychiatry. Washington, DC: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, pp. 43–84. [Google Scholar]