Abstract

The concept of ‘existential’, used frequently in Scandinavian healthcare journals, is associated with various, often unclear, meanings, highlighting the need for a more accurate understanding of the concept. In this integrative review we analyse how the concept has been used in Scandinavian healthcare journals from 1984 to 2020, exploring the trajectory of the concept, its definitions and its applications. A secondary aim is to offer some clarity regarding how the concept may be used in future healthcare research and provide a definition of ‘existential’ based on our findings. Our findings show that while the concept is increasingly used, it is rarely defined, and there appears to be no consensus on the concept’s meaning. We categorise applications of the concept into five overarching themes: (1) Suffering and re-orientation, (2) Meaning and meaninglessness, (3) Existential philosophy in relation to health (4) Existential questions as approaches to care and (5) Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual and religious concepts. Based on the findings, we propose a definition of the concept of ‘existential’ in the healthcare context. The study contributes to, and underscores advantages and limitations of, the use of the concept in healthcare research.

1. Introduction

The concept of ‘existential’, which is often used in Scandinavian white papers and Scandinavian healthcare journals, is associated with various meanings (Hvidt et al. 2021; la Cour and Hvidt 2010). The frequent use of the concept of ‘existential’ stands in contrast to, for instance, the practice in international research in the field of nursing, which commonly employs the consensus-based concept of ‘spirituality’ (McSherry and Ross 2017; Niu et al. 2021; Puchalski et al. 2014).

The diverse and often unclear notions of the concept of ‘existential’ in Scandinavian countries demonstrate the need for a more accurate understanding as well as to address the following questions: Why is the concept so often used in the Scandinavian context? What does the concept mean? How is the concept applied in Scandinavian healthcare journals? To explore theses question, there was a need to focus specifically on this geographical area before any comparisons could be made with the wider international literature. In Scandinavia, there are more people without a religious faith than in most other countries in the world (Urstad 2017). It is argued that ‘existential’ serves better than ‘spirituality’ because it is perceived as more open to the secular dimension (Stifoss-Hanssen 1999; Hvidt et al. 2021).

To map the use and relevance of the concept of ‘existential’ in the Scandinavian context, we started by analysing white papers published in Scandinavian countries (Sundhetsstyrelsen [Danish Health Authority] 2017; NOU Norges offentlige utreninger [Official Norwegian Reports] 2018; SOU Statens offentlige utredningar [Swedish Government Official Report] 2000). While the concept was used in documents from all Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden), definitions were not provided. Thus, the white papers became a starting point for a more precise search of the healthcare literature. In this article, we analyse Scandinavian researchers’ delineations of the concept and study its evolution and application in Scandinavian healthcare journals from 1984 to 2020. The analysis of the usage, operationalisation, meaning and interpretation of ‘existential’ has significant implications not only for clarity in research but also for the understanding of healthcare practice. In this paper we analysis how the concept of ‘existential’ is used in Scandinavian healthcare journals.

1.1. Evolution of the Concept of ‘Existential’ in Scandinavian Healthcare Research

Discussions on the use of the concept appeared in the late 1990s in the psychology of religion field (Stifoss-Hanssen 1999). In his article ‘Religion and spirituality: What a European ear hears’, Stifoss-Hanssen proposed ‘existentiality’ instead of ‘sacredness’ as the heart of spirituality because ‘existentiality’ is open to spirituality’s religious and secular dimensions.

The ‘existential’ is often seen in combination with ‘health’ (DeMarinis 2003; Sigurdson 2016; Stifoss-Hanssen and Kallenberg 1996). DeMarinis (2006, 2008) provided a much-cited definition (see Table 2) of ‘existential health’ in Pastoral Care, Existential Health and Existential Epidemiology, which emphasised the individual’s way of creating meaning. This definition remains widely used and referred to in the Scandinavian research field of the psychology of religion (Frøkedal 2020; Frøkedal et al. 2019; Haug et al. 2016; Lloyd et al. 2017; Søberg et al. 2018; Sundal and Lykkeslet 2020; Ulland and DeMarinis 2014).

Critically reflecting on DeMarinis’s work and drawing on philosophical traditions, Sigurdson (2016) provided another definition/understanding of ‘existential health’ (see Table 2), suggesting that the concept should be reserved for intentional relations with one’s own experience of illness and health. Binder (2022) also draws on philosophical traditions to explore the existential dimension in health and refers to the ‘ultimate concerns’ proposed by Yalom (1980): death, meaninglessness, isolation and freedom. Binder (2022) suggests an expansion of these concerns to include polarities, such as death and awareness of living a life of one’s own, meaning and meaninglessness, being with and isolation, and freedom and limitation (See Table 2). Austad et al. (2020) hold that the concept of existential also can refer to existential health, and they relate ‘existential’ to the basic conditions of being human proposed by Henriksen and Vetlesen (1997), such as vulnerability, dependency on others, the need for meaning and that we will die.

Little systematic research has been done to clarify the concept of ‘existential’. The first attempt to systematically examine one attribute of ‘existential’ (meaning making) was undertaken by la Cour and Hvidt (2010), who carried out a literature review identifying definitions of existential meaning making. Later Hvidt et al. (2021) conducted a survey exploring ‘Meanings of “the existential” in a secular country: A survey study’ (Hvidt et al. 2021), finding that ‘existential’ is a widely used concept though associated with diverse meanings. Based on more than 1100 responses from Danish participants, the authors created three groups of the meaning of existential: (1) ‘Essential meanings of life’ referred to as a secular, non-spiritual and non-religious sources; (2) ‘Spirituality/religiosity’ related to issues of transcendence, faith, spirituality and/or religiosity; and (3) ‘Existential thinking’ related to philosophy and philosophical ideas (Hvidt et al. 2021). Following the survey, they proposed that the concept of ‘existential’ was an overarching construct that could include secular, spiritual and religious meaning domains (Hvidt et al. 2021).

These previous studies evidence that authors have made some attempts to explore and construct a definition of ‘existential’ based on empirical data, and on theoretical and philosophical conceptualisation. To the best of our knowledge, our contribution is the first effort to explore the evolution and implementation of the concept of ‘existential’ as broadly understood as opposed to a single attribute, such as meaning making in Scandinavian healthcare journals.

1.2. The Aim

Given the gaps noted above, the primary aim of this study is to analyse, as mentioned, how the concept of ‘existential’ is used in Scandinavian healthcare journals, which involves exploring the trajectory, definitions and applications of the concept. A secondary aim is to offer clarity regarding how the concept may be used in future healthcare research by providing a definition of ‘existential’ based on our findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted an integrative systematic literature review. Because of the wide range of included material as all types of research methods and theories emerging in the material, integrative reviews have the potential to synthesise and capture the state of the field. The wide range of included material can contribute to theory development, providing implications for practice (Dhollande et al. 2021; Torraco 2016; Whittemore and Knafl 2005).

The rationale for focusing primarily on the Scandinavian journals was, as mentioned, that the term ‘existential’ is a commonly used in these countries. To explore the use of the concept, there was a need to focus specifically on this geographical area

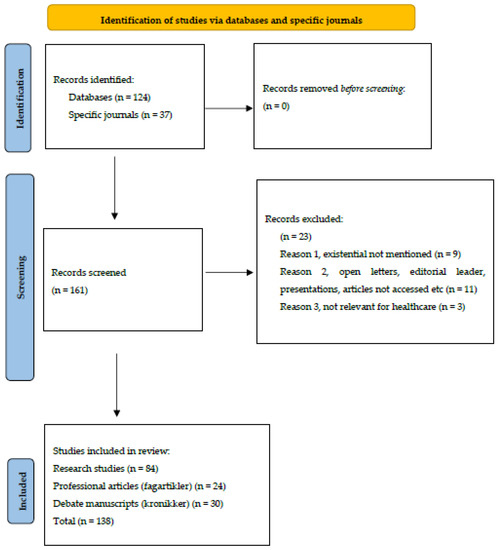

We used a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) to structure our search. To identify the material to review, we searched for the concept of ‘existential’ in journals in the healthcare field in Scandinavian countries. We did this by searching journals found in SweMed+, which was a Scandinavian database for medicine and health from 1977 until its termination in 2019. Due to the 2019 end date of SweMed+, we undertook a search for 2020 in each journal with hits for ‘existential’ in SweMed+. The latter search is mentioned as ‘specific journals’ in the diagram. Thus, our initial integrative review covered the period from 1977 to the end of 2020. As the first publication using ‘existential’ in the material we reviewed appeared in 1984, we included publications from 1984 to 2020 in our material. To grasp the current status of this field, we repeated the initial search from 2021 to May 2022, which yielded 85 publications. This underlines that concept is still increasingly used. However, this body of literature was not included in the analysis because we already had decided to focus on the literature that evolved over the previous decades. We are aware that an analysis including the most recent publications needs to be undertaken and constitutes a limitation of this study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. The PRISMA Flow diagram is based on the work of Page et al. (2021).

Few definitions of the concept of ‘existential’ were found in the publications we reviewed. As we also wanted to include definitions of ‘existential’ we expanded the search to include Scandinavian researchers’ definitions that were published internationally (Table 2).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Presentation of Data

The inclusion criteria were ‘peer-reviewed articles’ and the term ‘existential’. In SweMed+, we found 124 articles. Four articles were excluded because ‘existential’ was not mentioned in the text. After applying the inclusion criteria, 120 articles remained, comprising 27 debate manuscripts (kronikker) from medical journals, 71 research articles and 22 professional articles (fagartikler). Even though the category ‘peer-reviewed articles’ was an inclusion criterion, articles (not research articles) published in professional journals and debate manuscripts appeared in the retrieved results.

In the Scandinavian context, there is a category of articles called fagartikler (professional articles) that present and discuss relevant topics and research but are not regarded as research articles that introduce new knowledge. Nevertheless, we have included professional articles because they provided valuable information about the concept of ‘existential’. The inclusion criteria for definitions of ‘existential’ in our analysis was that they were coined by Scandinavian researchers and published in either Scandinavian or international healthcare journals.

In the additional search for articles beyond 2019 to 2020, we used the same inclusion criteria as in SweMed + and included three more debate manuscripts and 18 more articles (two professional articles and 16 research articles). In total, as mentioned, our material consisted of 138 publications (30 debate manuscripts, 84 research articles and 24 professional articles). The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) shows the processes involved in selecting the material for the integrative review. Twenty-three publications were excluded because ‘existential’ was not mentioned (9), the publications were not research articles, professional articles or debate manuscripts (11) or relevant for healthcare (3).

The debate manuscripts were written in Swedish (20), Norwegian (8) and Danish (2). The research articles and professional articles were from the followingly countries; Norway (42), Denmark (26), Sweden (24), Finland (4), Iceland (1) and Belgium (1). Some authors from other countries than Scandinavia did also publish in Scandinavian healthcare journals. In addition, 10 articles were written in cooperation between researchers from Norway and/or Sweden and/or Finland. The research articles utilised a wide variety of approaches/methods, such as case studies, surveys, phenomenology and literature review. The target group for the articles was primarily researchers/professionals in the field of nursing/healthcare. The presentation of the material is provided in the Appendix A Table A1 ‘Overview table of all articles and analytical overarching themes’.

2.3. Data Analysis

The analytical process was undertaken in three stages. (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Stages in the analytical process.

At stage 1, we conducted an exploratory review of all published material (Jebb et al. 2017). At stage 2, we undertook a keyword analysis of the definitions (Seale and Charteris-Black 2010). At stage 3, the publications were shared equally between the researchers, who reviewed each article with a focus on topics such as authors, countries, year of publication, target group, methods and whether a definition of ‘existential’ was provided. Quotes in which ‘existential’ was used, themes related to ‘existential’, relevant key findings related to ‘existential’ and the researchers’ reflections about the use of the concept were recorded. The research articles and articles from the professional journals were gathered and are presented chronologically in Table A1. When there was uncertainty about the inclusion of an article, the first author reviewed the article and made the final decision with the reviewing author. This stage ensured consistency in the inclusion of articles and material for analysis.

We used reflexive thematic analysis to develop and examine the topics presented in Table A1, which also allowed us to develop themes of the application of the concept across the articles (Clarke and Braun 2022; Braun et al. 2017). Following the six phases of reflexive thematic analysis outlined by Clarke and Braun (2022), (1) we started with familiarisation of the material by reading the articles. (2) We divided the articles between the researchers for review. (3) We coded the material, identifying relevant features, and searched for themes as we clustered codes, mapping relevant key patterns in the data. Patterns of themes emerged. (4) We then reviewed the themes, checking that they fit the coded data. (5) Further, five overarching themes became apparent to us and we gave them names according to the content of them.

Finally, conducting the sixth phase of Clarke and Braun (2022), we drew conclusions across the themes. Together, the researchers discussed each researcher’s individual findings in light of the findings presented in Table 2. This process was continued until agreement was reached on the final overarching themes to be presented.

Table 2.

Definitions of ‘existential’ included in the analysis.

Both integrative review and thematic analysis have been criticised for being too ‘flexible’ (Clarke and Braun 2022; Dhollande et al. 2021; Torraco 2016). Due to this flexibility, in our process of constructing Table A1, we emphasised transparency, which we ensured by using relevant extensive quotes from each article. However, as the quotes were long, they had to be limited to create a readable version of the table. The first author reduced the length of the quotes and comparisons, and the researchers adjusted the abridged quotes until agreement was reached. In Table A1, the overarching themes derived from the quotes are easily seen. The analysis was inductively conducted (Afdal 2010), and the findings are discussed in relation to relevant research in the field.

3. Results

The findings are presented according to each stage of the analytical process outlined in Table 1 to provide insight into the significant findings at each stage.

3.1. Findings from Stage 1: Trajectory of the Concept of ‘Existential’

To describe the trajectory of the concept of ‘existential’ in healthcare journals, we used debate manuscripts, professional articles and research articles.

The data showed that the concept of ‘existential’ was first used in the 1984 in a Swedish medical journal, in a debate of searching for a concept to describe a non-somatic-derived pain that the doctors observed in a large group of people (Dahn 1984; Hartvig 1984; Johansson 1984). The concept of ‘existential pain’ was argued to be useful because it was an extensive and open concept and provided a neutral designation, as well as an alternative to biological pain (Dahn 1984).’Existential’ was not defined, but ‘existential pain’ was described as a diffuse pain, boundless in time and space. However, the concept of ‘existential pain’ was also criticised for being too diluted and vague (Johansson 1984).

In the 1990s, the concept continued to be used in medical debate articles in Sweden (5) (Hedberg 1992; Björklund and Eriksson 1997; Strang and Adelbratt 1999; Strang and Beck-Friis 1999; Thörn 1998) and Norway (1) (Cullberg 1996). The first debate manuscript, in the material we reviewed, in the 1990s introduced an understanding of the human being inspired by existential philosophy (Hedberg 1992); the Swedish article presented a critique of the natural science approach, which divided the human into body and soul. Hedberg (1992) defined ‘existential’ as something that has vital (livsavgjørende) character for the individual. This manuscript was the first of many to introduce existential philosophy into the health debate in the Scandinavian health research journals included in this review.

The five other debate manuscripts addressed as diverse areas as the treatment of the existential side of depression (Cullberg 1996), existential questions in connection to children’s disease and death (Björklund and Eriksson 1997), the existential crisis of the medical profession (Thörn 1998), existential questions in palliative care (Strang and Adelbratt 1999), the need for existential support, such as ‘existential dialogues’, concerning existence, life, death, meaning and meaningless and loneliness in palliative care (Strang and Beck-Friis 1999). In 1999, the first research article included in our review was published in the field of nursing (Norway) (Gonzalez 1999). The article focused on existential and spiritual issues as meaning-related phenomena.

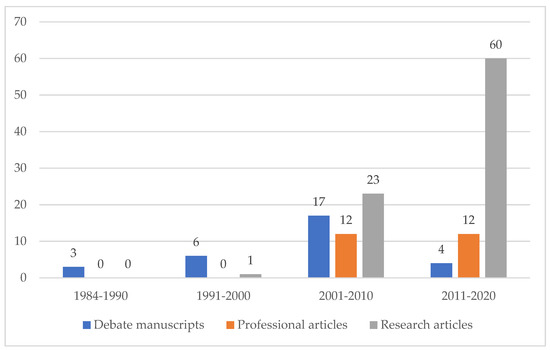

The decade 2001–2010 saw sudden growth in research articles (see Figure 2 showing an overview of publications in Scandinavian healthcare journals using ‘existential’). The topics addressed concerned for instance meaning and holistic existential care (Berg and Sarvimäki 2003; Bullington et al. 2003; Hummelvoll 2006; Jonsen et al. 2010), suffering (Gudmannsdottir and Halldorsdottir 2009; Rehnsfeldt and Eriksson 2004; Rydahl-Hansen 2005), existential topics in relation to spiritual care and religiousness (Ausker et al. 2008; Dam et al. 2006; Lundmark 2005; Schärfe and Rosenkvist 2008).

Figure 2.

Overview of publications in Scandinavian healthcare journals using the concept of ‘existential’. The figure illustrates the number of debate manuscripts (blue), professional articles (red) and research articles (grey).

The number of debate manuscripts also continued to increase (see Figure 2), dealing with issues such as lack of competence in approaching the patients’ need for existential dialogues (Bischofberger 2000), questions such as whether the patients’ ‘inside’ is the healthcare services’ responsibility (Jacobsson 2001) and meaning (Holm 2003; Skaiå 2003).

During the decade from 2010, the research articles and professional articles further increased, accounting for almost twice as many publications as had appeared to that point. Topics from the previous decade continued, such as exploring different kinds of suffering, including experiences of loneliness (Hemberg et al. 2018; Homme and Sæteren 2014), dying with pain (Poulsen 2011) and burnout (Arman et al. 2011). Philosophical approaches also appeared (DeMarinis 2011; Grelland 2012), such as quality of life, courage in life and meaning (Bondevik 2012; Thorsen 2019; Maehre 2019) and spiritual issues (Hvidt et al. 2018; Rykkje 2016). In addition, ecological topics emerged (Slåttå and Madsen 2014; Thorsen Gonzalez 2013). During this decade, there seems to be an abrupt decline in the number of debate manuscripts published, with only three publications: one about existential anxiety (Strang 2016) and two about people with COVID-19 experiencing spiritual and existential suffering (Brenne et al. 2020; Getz 2020).

Our material shows a growing use of ‘existential’, as the following publication numbers indicate: 1984 (n = 3), 1984–1990 (n = 3), 1991–2000 (n = 7), 2001–2010 (n = 52) and 2011–2020 (n = 76).

3.2. Findings from Stage 2: Keyword Analysis of Definitions of ‘Existential’

Key attributes. Ten published definitions of or commentaries on ‘existential’ were imported into a single Word document table (see Table 2) and analysed using the ‘find and highlight’ function in Microsoft Word (for 365 Microsoft Office). While this is a rudimentary form of analysis, it is a very useful and efficient way of highlighting and scrutinising the frequency and use of keywords within and across texts (in this instance, definitions).

The analysis revealed that ‘existential’ is not used as a standalone definition but often appears in association or in conjunction with a qualifying or explanatory descriptor. These descriptors explain the context and usage of the word, such as ‘existential health’ (Sigurdson 2016), ‘existential psychotherapy’ (Yalom 1980; Binder 2022). Yalom is not a Scandinavian contributor but is cited often in Scandinavian healthcare journals. Further, descriptors such as ‘existential orientations’ (la Cour and Hvidt 2010) and ‘existential care’ (Prause et al. 2020; Giske and Cone 2019) are mentioned. The 10 definitions (see Table 2) included in the keyword analysis because they have shaped the evolution of the concept of ‘existential’, informing the work of other authors working within this field. The other definitions were found while reviewing the literature (see Section 1.1).

Analysis of the keywords (Table 3) and attributes within each definition revealed that across the 10 definitions, approximately 39 attributes were used to describe or explain the concept ‘existential’. The most frequently used attribute, as may be anticipated, was the word ‘existential’, with 26 references; it is present in all the definitions. While the inclusion of the word existential may seem pointless, the decision to retain it was made because ‘existential’ is often used in conjunction with another word to denote the context and application of its use. The next was ‘meaning’, with 13 occurrences used by six authors, followed by ‘health’ with 11 references (used by only one author). Other than ‘existential’, no other attribute appeared in all the definitions. Several attributes, including religious (eight references across five definitions) and spiritual (10 references across six definitions), were used when explaining ‘existential’ in relation to important aspects of life. The word ‘existential’ was used as an overarching concept.

Table 3.

Keywords used in definitions of ‘existential’.

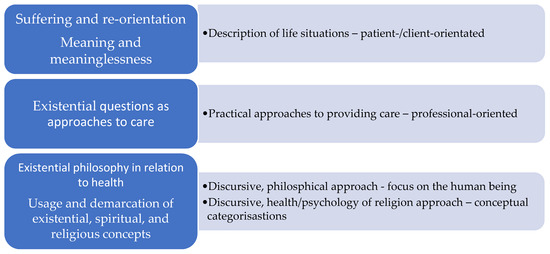

3.3. Findings from Stage 3: Thematic Analysis of the Articles’ Application of ‘Existential’

Five main overarching themes were constructed during the thematic analysis (see Table 4 and Table A1): (1) suffering and re-orientation, which related to dynamics between suffering and new orientation; (2) meaning and meaninglessness; (3) Existential philosophy in relation to health; (4) existential questions as approaches for care, referring to questions reading what is importance in life, which are often asked in relation to existential care; and (5) usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual and religious concepts.

Table 4.

Categorisation of overarching themes of the application of the ‘existential’.

Finally, ‘existential’ sometimes emerged as paired with other words, such as ‘existential pain’, ‘existential struggle’, ‘existential encounter’, ‘existential meaning’ and ‘existential health’. However, ‘existential’ paired with other words did not represent a specific theme. In some articles, only one overarching theme emerged, while in others, all the themes appeared.1 Table 4 presents the categorisation of the overarching themes found in the articles’ application of the concept of ‘existential’.

3.3.1. Suffering and Re-Orientation

The most prominent overarching theme related to ‘existential’ was suffering and re-orientation, which concerned the dynamics between suffering and orientation towards a better state of being. ‘Suffering’ in this context referred to different types of stressors, such as chronic and severe illness, physical pain, being deaf–blind, loneliness and depression. The suffering outlined in the articles could be termed chronic, acute, relational, mental, spiritual or physical and, as related to ‘existential’, was often described as severe, during terminal illness. At this boundary, the concept included a struggle between the darkness of suffering and an inner source of strength (Blegen et al. 2014).

The stressors were normally described in an interplay with openness to a better situation. Hope was linked to different situations, such as finding relief, comfort, new understandings or other resources to improve the situation.

3.3.2. Meaning and Meaninglessness

Frequently mentioned in the articles, meaning was often related to a lack of meaning and existential meaning making, which referred to sources promoting health, such as the perception of life as coherent and holding hope for the future (DeMarinis 2016; Ekblad et al. 2012). The lack of meaning, in contrast, was closely related to health challenges; for instance, depression and burnout were associated with a deficiency of meaning (Arman et al. 2011; Thorsen Gonzalez 2013). Thus, the concept of ‘existential’ was not limited to one state of meaning but related to meaning in motion between meaningfulness and meaninglessness. Moreover, ‘existential’ was used in conjunction with other terms in various ways in this theme. For example, existential suffering, existential loneliness, existential meaning making and existential resources were mentioned, among other combinations.

Even though patterns emerged in the material, producing overarching themes, the use of ‘existential’ remained complex. While the first two themes—suffering and re-orientation and meaning and meaninglessness—focused on dynamics in people’s life situations, the third theme, discussed below, emphasised ‘existential’ from philosophical perspective.

3.3.3. Existential Philosophy in Relation to Health

The theme ‘existential philosophy in relation to health’ was based on the theoretical framework of existential philosophy. In this theme, understandings of the human being and their relation to health were explicitly influenced by existential-humanistic philosophy and psychology, such as Laing, Rogers, May and Yalom (Hummelvoll 2006), van Manen (Harder et al. 2012) and Løgstrup (Thorsen 2018).

A non-reductionist understanding of the human emerged as central. A holistic existential perspective focuses on an individual’s ‘being in-the-world’ (Berg and Sarvimäki 2003). Heidegger expanded the concept of being-in-the-world through basic structures or ‘existentials’ (Heidegger 1957, cited in Sundal and Lykkeslet 2020). According to Harder et al. (2012), van Manen also emphasised four so-called existentials—lived space (spatiality), lived body (corporality), lived time (temporality) and lived human relation (relationality)—as basic human features or basic conditions that apply to all people, whether healthy or sick. In this theme, the term ‘existential’ referred to our basis in life (Andermo et al. 2018).

‘Existentials’ also emerged through Yalom’s ‘existential isolation’, which can be understood as a separation from the world (Nilsson et al. 2006). According to Delmar (2019), separation from the world can result from life-limiting existential phenomena such as loneliness, homelessness, hopelessness, despair, anxiety, powerlessness, vulnerability and longing.

This overarching theme, therefore, represented a theoretical discourse related to existential philosophical views, whereas the next theme points towards discussions about the concept mainly found in the fields of psychology of religion and nursing. However, there was overlap between the two themes.

3.3.4. Existential Questions as Approaches to Care

Existential questions include ‘Who am I? What is the meaning of life? Where am I going? Why is disorder a part of my life? What would happen if I took my own life’ (Fleischer and Jessen 2008, p. 16). They often relate to the different approaches used in the provision of care from the perspectives of professionals or other helpers. Crucial in what was described as ‘existential care’ was listening to existential questions. In the psychology of religion, such questions were closely linked to existential and spiritual care; to carry out such care, the carer needs ‘to pay attention to the patient’s existential and spiritual questions and resources…and to assist the patient in his/her work with existential questions based on his/her own view of life’ (Jakobsen and Hvidt 2018, p. 22). Spiritual care in the field of nursing emphasised, among other things, the expression and discussion of existential questions as part of the care (Lundmark 2005; Rykkje 2016). Existential questions could prompt new adjustments (Barremo et al. 2008) and were said to promote empowerment and mental health when provided with care (Asbring and Jeanneau 2006).

3.3.5. Usage and Demarcation of Existential, Spiritual and Religious Concepts

Some articles presented how the concepts ‘existential’, ‘spiritual’ and ‘religious’ were linked in the three following ways: (1) spirituality as an overarching concept with ‘existential’ as a subcategory; (2) existential as an overarching concept with spirituality and religious as subcategories; and finally (3) existential and spirituality as mutual expanding concepts.

In the material we reviewed, most of the papers used ‘spirituality’ as an overarching concept, which was portrayed in different ways. For instance, spirituality was described at an ontological level, with existential serving as a subcategory to the ontological perspective (Rehnsfeldt and Eriksson 2004). Spirituality was also portrayed, as already mentioned, as a search for answers to existential questions about the meaning of life (Lundmark 2005; Toivonen et al. 2018), in which existential was argued to be a subcategory to ‘spiritual’ represented by existential questions. Moreover, the word pair ‘spirituality and existential care’ was sometimes abbreviated to become ‘spiritual care’ (Viftrup et al. 2020) and can be understood as the concept of spirituality overarching and embracing the existential.

In arguments using existential as an umbrella concept, the concept included spiritual, religious and secular domains (DeMarinis 2003, 2008; Frøkedal 2020; la Cour and Hvidt 2010). ‘Existential’ as an overarching concept provides a framework that includes the secular domain, as well as the spiritual and religious spheres.

‘Existential and spiritual’ appeared to be used as a pair giving them the same status and level. They were not presented as one concept overarching the other (Frølund 2006), with one study arguing that in Norwegian literature, the words ‘spiritual’ and ‘existential’ are commonly used in combination or in conjunction with each other (Sörbye and Brunborg 2015). Our analysis shows that the psychology of religion often emphasises ‘existential’ as an umbrella concept. In contrast, nursing tended to highlight ‘spiritual’ as the overarching concept. The pairing of ‘spiritual’ and ‘existential’ was identified across both fields.

The five overarching themes emerged in complex interactions. Each theme had inherent dynamics and appeared in various combinations. Furthermore, the themes represented different levels and interpretations of how the concept of ‘existential’ was used in diverse settings and disciplines.

3.3.6. Additional to the Overarching Themes

Some notions of ‘existential’ did not fit into the overarching themes. One example was the understanding of ‘existential needs’ as opportunities to (1) experience nature, (2) express oneself creatively and (3) feel connectedness (Prause et al. 2020), with nature, creativity and connectedness explicitly emphasised. The other categories did not relate explicitly to the nature, creativity or connectedness.

3.4. Integration and Significance of the Findings from the Three Analytical Stages

Integrating the findings from the three stages of analysis provided deeper insight into how the concept of ‘existential’ has evolved and is being applied in healthcare. First, we consider ‘suffering and re-orientation’ and ‘meaning and meaninglessness’ as themes related to dynamics in life situations—mainly as concerns in patients’ and clients’ lives but also as applicable to all human beings. The themes overlap; for instance, suffering might relate to meaninglessness and re-orientation might contribute to meaning.

The next overarching theme, ‘existential questions as approaches to providing care’, represents another dimension of the concept, highlighting how mainly professionals approach life situations. The approaches are linked to people’s life situations but also to the overarching themes of ‘Existential philosophy in relation to health’ and the ‘usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual and religious concepts’.

We regard these two final themes as being on a third level—a discursive level in the three traditions that contribute to a theoretical framework for the concept of ‘existential’. The pairing of words with ‘existential’ also appeared in some of the overarching themes but was not linked to a particular theme.

Figure 3 illustrates the three dimensions that emerged from the overarching themes. The first dimension, which included ‘suffering and re-orientation’ and ‘meaning and meaninglessness’, focused on the patients’ and clients’ life situations. The second dimension, drawn from ‘existential questions as approaches for care’, emphasised practical approaches for professionals providing care. The third dimension, which included ‘existential philosophy in relation to health and the ‘usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual and religious concepts’, underlined discursive debates on the human being and conceptual categorisation.

Figure 3.

Three dimensions of the overarching themes of ‘existential’.

The discursive approach relates to the main discourses within each tradition: existential philosophy, psychology of religion and spiritual care in health care/nursing. The five overarching themes overlapped with or intersected with each other. Thus, the concept of ‘existential’ emerged as highly complex, influenced by different traditions, discourses, fields of practice, approaches and various topics related to being human and life situations.

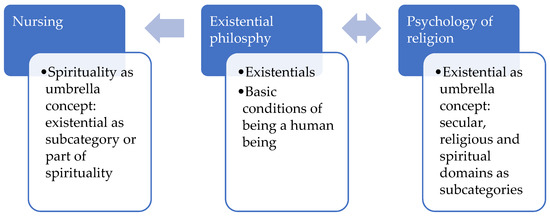

Figure 4 illustrates some of the main discourses within the three research traditions prevalent in the material we reviewed: existential philosophy, psychology of religion and nursing. These discourses include ‘being-in-the-world’ as proposed by Heidegger (1957) through basic structures or ‘existentials’ (Yalom 1980) in the traditional perspective of existential philosophical, ‘existential’ as an umbrella concept in the psychology of religion (DeMarinis 2006; Frøkedal et al. 2019) and ‘spiritual’ as a more extensive concept than ‘existential’ in healthcare and nursing research (Hvidt et al. 2018), in which context Hvidt et al. argue that ‘translating spiritual only with existential will be too sterile’ (p. 271).

Figure 4.

Discourses of ‘existential’ in three research traditions relevant to health research.

However, these discourses are not distinct as each field borrows perspectives from the others, combining theoretical and conceptual frameworks across the traditions. In the material we reviewed, existential philosophy provided understandings of ‘existential’ to both nursing and the psychology of religion. Likewise, the psychology of religion was referred to in existential philosophy (DeMarinis 2006; Sigurdson 2016). In contrast, nursing, in our material, does not seem to have been used in existential philosophy or the psychology of religion.

Therefore, despite the concept of existential being increasingly used, few intentional definitions have been provided. The application of the concept was particularly complex because the overarching themes represented different dimensions, such as life situations, views on the human being, worldviews, such as the existential as an overarching concept or a subcategory of spirituality and, finally, practical approaches to care. Moreover, different traditions use the concept in different ways and borrow perspectives from each other.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to analyse how ‘existential’ was used in Scandinavian healthcare journals. The secondary aim was to offer some clarity regarding how the concept may be used in future healthcare research and to attempt to provide a definition of ‘existential’ in the healthcare framework based on our findings. In this section, we discuss some reasons why ‘existential’ is so often used in Scandinavian healthcare journals, the lack of uniformity of the concept and suggest a definition. The findings emphasise the utility and pitfalls of the concept and the need for further research.

4.1. Increasing Use of ‘Existential’

The findings show the increasing and wide-ranging use of the concept in healthcare journals. ‘Existential’ first emerged as a broad, open concept, used to describe a gap that biological pain could not address or resolve (Dahn 1984). According to the first authors to use the concept (Dahn 1984; Hartvig 1984; Johansson 1984), non–biological pain was combined with ‘existential’ to create a neutral (neither religious or spiritual) concept.

While non-biological pain could have been combined with the concepts of ‘spiritual’ and ‘spiritual pain’, these concepts do not necessarily have neutral associations in the Scandinavian context. As mentioned, even in 1999, Stifoss-Hanssen (1999) emphasised that ‘existential’ served better as an overarching category than ‘spiritual’ and ‘religious’ because it is open to the secular dimension. This notion is supported by recent empirical research on the concept of ‘existential’ in a secular country, Denmark, which suggested that ‘spirituality’ creates resistance (Hvidt et al. 2021). The authors argue that ‘existential’ is less polemical than ‘spirituality’: ‘Existential is a much more forgiving, inclusive and encompassing umbrella under which people can find a meaningful abode’ (Hvidt et al. 2021, pages not found in the article).

Thus, ‘existential’ might be understood as an impartial concept, encompassing the secular domain without ‘transcendent undertones’ in the Scandinavian context. Increasingly combined with health perspectives, it can be regarded as an umbrella concept, enveloping the secular, spiritual and religious domains (Hvidt et al. 2021; la Cour and Hvidt 2010), and as a means of filling a gap in a society that wants alternatives to transcendent sources.

4.2. A Concept without Consensus

Our materials show little clarity or uniformity in how the concept is understood and defined. The keyword analysis reveals that some attributes of the concept appear across the definitions, but these lack consistency. The analysis also shows how ‘existential’ is not an independent concept but is dependent on other descriptions that justify its use and application. The different stages of this integrative review demonstrate that there is no real consensus on the concept.

The publications examined provided few definitions, and only two intensional definitions were found in the work of Scandinavian researchers or in Scandinavian healthcare journals (DeMarinis 2008; Prause et al. 2020). Intensional definitions attempt to present the sense of a term (Lyons 1977). In DeMarinis’s definition, the use of the word ‘meaning’—applied to meaning-making and systems—can be religious and non-religious, and the existential dimension and spiritual nature are separated, with no definition of what is meant by a system or what the relationship is between the existential dimension and spiritual nature. The existential dimension appears to be a broad umbrella term, but there is no indication of how this relates to other dimensions of the person. The definition focuses, instead, on existentiality and how the individual makes or derives meaning in life.

For Prause et al. (2020), the principal focus of their short definition is on existential care and how this relates to holistic care. ‘Existential’ is highlighted as something that is the ‘innermost’ part of the person, considered sacred and concerning interconnections with religious, spiritual and secular aspects of life. Interestingly, some attributes employed in this definition resemble those used to define ‘spirituality’, such as ‘sacred’ and ‘nature’. A milestone in the debate in defining spirituality was the publication of the consensus definition produced by (Puchalski et al. 2014, p. 646):

‘Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.’

Some extensional definitions are provided in the material we reviewed. Extensional definitions define a concept by listing the objects that it describes (Lyons 1977). One example is Yalom’s (1980) description of the concept. Yalom is not a Scandinavian contributor but is cited often in Scandinavian healthcare journals. Yalom’s notion does not appear to be a ‘definition’ but more of a justification for not exploring this field within psychotherapy due to the vagueness and relationship with other equally nebulous terms.

Sigurdson (2016) gives another extensional definition, which was the only definition to use the word ‘reflexive’ (three occasions) to describe existential as in a reflexive feature of humanity. Sigurdson emphasises, however, that this reflexive process is central and innate to the process of living—that we are not consciously seeking it or aware of it. Binder (2022) underscores the embodied aspect by adding embodiment and emotional beings to Yalom’s ultimate concerns.

Hvidt et al. (2021) also provided what we regard as an extensional definition in a series of descriptive attributes considered by the author as aspects of secular existential orientations. Their emphasis appears to be on the aspects of the person that are located in the temporal and not the transcendent. The reflective narrative provides valuable insights into the relationship between the different dimensions of the person.

The lack of consensus around the concept of ‘existential’ contrasts with ‘spirituality’, for which consensus has been established, first in the United States (Puchalski et al. 2014). A rigorous process of consultation and consensus provided a watershed in the evolution and application of the concept of ‘spirituality’ within healthcare. A definition of the concept was developed from empirical research, incorporating a broad range of healthcare perspectives and disciplines. The definition was later adopted and developed by other associations and networks.2 However, our literature review suggests that this process of engagement, consultation and research has not occurred for the concept of ‘existential’ as used within the Scandinavian healthcare context. Thus, Scandinavian healthcare journals increasingly use a non-consensus-based concept. This may be problematic in communication with international healthcare research using the consensus-based concept of ‘spirituality’. The lack of a clear definition may complicate international healthcare debates and limit the relevance of Scandinavian healthcare research in relation to this much-used concept.

4.3. An Attempt to Define ‘Existential’ for the Healthcare Context

As a synthesises of our findings, we define the concept of ‘existential’ in the framework of healthcare as follows:

The term ‘existential’ related to health refers to the fundamental, basic condition of being a human. The existential is based on the irrefutable fact that we live and will die, facing conditions and uncertainties along the way beyond our control. The existential is expressed primarily through a quest for making and seeking meaning in life in general, as well as in demanding life situations. This may involve movements between suffering and re-orientation and meaning and meaninglessness. Existential concerns can be integrated into both religious, secular, and spiritual worldviews.

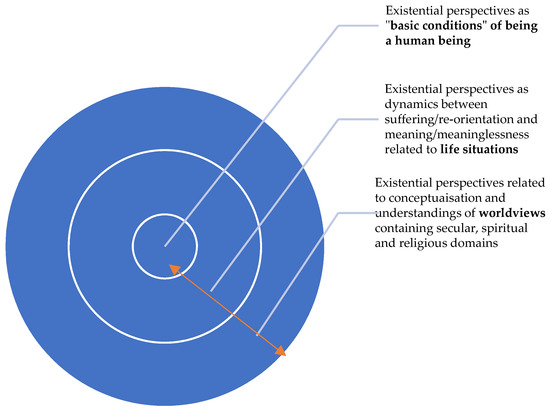

The definition is based on our findings regarding (1) ‘existential’ as ‘existentials’ and the ‘basic condition of being a human being’ (Heidegger 1957; Yalom 1980), (2) the dynamics between suffering and re-orientation, as well as meaning and meaninglessness related to life situations and (3) the usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, religious and secular domains related to understandings of world views or ontological aspects. The definition is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A definition of ‘existential’ in the framework of healthcare.

The figure shows that ‘existential’ relates to ‘being human’, ‘being in life situations’ and ‘being in the world’. The arrow in the figure illustrates the approaches to care in the material we reviewed, which relate to the basic condition of being human, the dynamics of suffering and re-orientation and meaning and meaningless, and world views. Our definition includes inherent elements of the concept, which dynamically overlap and intersect with each other.

We believe that the definition and illustrating model are applicable to healthcare research and practice. The definition is dynamic and can be adjusted to the specific needs of the research or practice, defining the basic condition, life situations and worldview relevant to the case. The model can be used to clarify which aspects of the concept are emphasised. For instance, the basic conditions of being human can be nuanced with other relevant literature, such as Henriksen and Vetlesen’s basic conditions that people are vulnerable and dependent on others, that relations are fragile, that life has an end and that we all need care (Henriksen and Vetlesen 2006) or Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1943).

The dynamics of suffering and re-orientation and meaning and meaninglessness can, for instance, be emphasised through literature on meaning making (Damásio et al. 2013; Schnell 2010) and existential meaning making (Binder 2022; Hvidt et al. 2021; la Cour and Hvidt 2010). However, meaning making is closely related to the ontological perspectives and cannot be separated from the outer circle in the model.

The ontological perspectives in the model can be emphasised on their own or as linked to the other perspectives. The arrow in the model indicates that the different layers of the circle can be linked but also adjusted to a special research interest in one of the layers. However, the definition of ‘existential’ illustrates that there can be no other meaningful understanding of a person apart from his or her relationships with, for instance, community, the ‘other’ and the environment. We regard people as individuals who are inseparable from the social system in which they live (Myers 2011). While Myers understands the individual as having a relation to a transcendental force, in the material we reviewed, the need for such a force related to the concept of ‘existential’ is not emphasised. We believe that our definition must be further elaborated on with more research.

4.4. Limitations of the Concept Based on Our Findings

The concept appeared psychologically, philosophical and was, with some exceptions, cognitively orientated, emphasising intellectual and reason to achieve meaning. This is a serious limitation as it excludes individuals who have lost or do not possess these functions. The danger is that a cognitively oriented approach could lead to the exclusion and dehumanisation of people who do not possess these abilities. It could also produce a reductionistic view of the human that does not include embodied meaning.

In the definitions of ‘existential’ in the material we reviewed, ‘connectedness’ is seldom mentioned. We consider it important to be aware of the inherent understanding of the human being as isolated. This view risks making the person appear isolated rather than a relational individual whose connectedness is a significant core of being a human being. We consider the view of the embodied and relational human interacting with their context important in both research and healthcare practices.

4.5. Strength and Limitations of the Study

An original and unique contribution of this integrative review is its attempt to draw upon different disciplines, such as nursing and the psychology of religion, to gain a rich and deep understanding of the concept of ‘existential’.

One significant limitation was the inability to identify a precise definition of the concept that can be applied consistently. The study classified definitions into two broad categories (intentional and extensional). However, applying these two categories was not always possible due to the fluidity and interplay between the two.

It was also difficult to identify specific attempts to define ‘existential’ within articles that did not provide a standalone definition of the concept but sought to define an attribute, such as existential needs (Prause and Sørlie 2018). In addition, some authors sought to address the concept of ‘existential’ while referring to spirituality (Hvidt et al. 2018), blurring the concepts and boundaries.

Due to these challenges, we may have overlooked possible attributes or descriptors that inform the ongoing debate and understanding of ‘existential’ as used in Scandinavian healthcare research. A limiting factor in this integrative review was the decision to focus only on SweMed+ sources since this means we only captured and retrieved manuscripts published in this database. Another limitation was that as some Scandinavian authors have published on the concept of existential in non-Scandinavian journals, we have omitted a significant body of work that could offer important perspectives on this discussion.

5. Conclusions

The concept of ‘existential’ is used frequently in Scandinavian healthcare journals. Various disciplines use this concept, including nursing and the psychology of religion, but no consensus on the concept has yet emerged. A lack of clear definitions may complicate international healthcare debates and make Scandinavian healthcare research less relevant.

Our findings highlight five overarching themes in the application of the concept: (1) suffering and re-orientation, (2) meaning and meaninglessness, (3) Existential philosophy in relation to health (4) existential questions as approaches to care and (5) usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual and religious concepts.

The findings also inspired a definition of the concept. The term ‘existential’ in the context of health embraces the basic conditions of being human, the dynamics of suffering and reorientation, meaning and meaninglessness and, finally, secular, spiritual and religious worldviews.

While our article contributes to the process of clarifying the concept of ‘existential’, further research and development of consensus is needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.N., W.M., T.S., O.S., A.A.; methodology, M.R.N., W.M., T.S., O.S., A.A.; Formal analysis, M.R.N., W.M., A.A.; investigation, M.R.N., W.M., T.S., O.S., A.A.; resources, M.R.N.; data curation, M.R.N., W.M., T.S., O.S., A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.N., W.M.; writing—review and editing, M.R.N., W.M., T.S., O.S., A.A.; visualization, M.R.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided in Appendix A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview table of all articles and analytical overarching themes.

Table A1.

Overview table of all articles and analytical overarching themes.

| Author, Year, Country | Discipline and Language of the Articles | Research Design | Definition of Existential | Themes—Key Attributes | Some Exemplars | Overarching Categories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | (Gonzalez 1999) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Literature review | No | Pair Meaning | Existential –threat, –struggling, –frustration, –alienated, –isolation Existential and spiritual as meaning related phenomena | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 2. | (Berg and Sarvimäki 2003) Norway, Sweden, Finland | Nursing, researchers in the field English | Theoretical, philosophical | No | Holistic being in the world | A holistic existential perspective focuses on individual’s ‘being in-theworld’ promote health | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 3. | (Bullington et al. 2003) Sweden | Dance Therapist, Clinicians in the field English | Empirical | No | Existential Pain Meaning | From chaos to meaning Existential, psychological/psychosomatic aspects of chronic pain, as seen from the clinicians’ perspective | Meaning and meaninglessness Suffering and reorientation |

| 4. | (Ladegaard Jensen 2004) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Professional article | No | Questions | Existential questions Existential unrest | Existential questions as approaches for care Suffering and reorientation |

| 5. | (Rehnsfeldt and Eriksson 2004) Sweden, Finland | Researchers in the field English | Empirical | No | Suffering Caring encounter Meaning | The human existence …experienced suffering can mean not to be able to hold oneself together as a whole ‘Existential caring | Existential philosophy in relation to health Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness Existential questions as approaches for care Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts |

| encounter’…the encounter between patient and caregiver can create meaning in communion and thereby alleviate suffering by making it bearable. Existential movement of suffering that makes it possible to understand life in a more profound spiritual or ontological way and in this way experience alleviated suffering. | |||||||

| 6. | (Erdner et al. 2005) Sweden | Health professions English | Empirical | No | Social alienation | Experiencing existential and social alienation | Suffering and reorientation |

| 7. | (Lundmark 2005) Sweden | Chaplaincy and nursing Swedish | Empirical | No | Problems Freedom Meaning Isolation Death | Existential—patients’ challenges related freedom, meaning/meaninglessness, existential isolation, and death Spiritual care means making possible/facilitating for the patient, with help of suitable nursing interventions, to express and discuss existential questions and to practice his/her spirituality | Meaning and meaninglessness Suffering and reorientation Existential philosophy in relation to health Existential questions as approaches for care Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts |

| 8. | (Nyman and Sivonen 2005) | Nursing Swedish | Conceptual analysis | No | Meaning | Existential perspectives on the ultimate meaning is belief in the ultimate being | Meaning and meaninglessness Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 9. | (Rehnsfeldt and Arman 2005) Sweden | Healthcare professionals Swedish | Professional article | No | Questions | Existential questions Existential and spiritual Existential suffering | Existential questions as approaches for care Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Suffering and reorientation |

| 10. | (Rydahl-Hansen 2005) Denmark | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Suffering | Existential and theological theories about human suffering | Suffering and reorientation |

| 11. | (Carlstedt 2006) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Professional article | No | Basic condition | Basic conditions Existential freedom | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 12. | (Dam et al. 2006) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Professional article | No | Dialogue | Existential/spiritual Existential dialogue | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 13. | (Frølund 2006) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Empirical | No | Spiritual existential Death Loss | Loss of existents because of imminent death. Terminally ill patient…focusing on the spiritual/existential dimension. | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Suffering and reorientation |

| 14. | (Hummelvoll 2006, p. 22) | Nursing Norwegian | Professional article | Yes | Existential suffering and holistic care | “Existential here means what concerns the human existence and life situation, ie problems and challenges that people encounter related to, e.g., freedom of will and responsibility of choice» “Eksistensiell betyr her det som angår menneskets eksistens og livssituasjon, dvs. problemer og utfordringer som mennesker møter knyttet til bl.a. viljens frihet og valgets ansvar» From a perspective of a holistic existential understanding of suffering in psychiatric nursing practice four overlapping aspects emerge: (1) suffering from illness, (2) existential suffering as lack of meaning with life and that the human being carries insight about being separated and lonely, (3) suffering in the relation between care provider and receiver, (4) social suffering as reduced possibilities for taking part in the society | Meaning and meaninglessness Suffering and reorientation |

| 15. | (Nilsson et al. 2006) Norway, Finland | Nursing English | Literature study Philosophical | No | Isolation | Existential isolation Yalom perceives as a ‘separation from the world’ | Suffering and reorientation Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 16. | (Stolt 2006) Sweden | Medicine Swedish | Empirical | No | Suffering | Existential questions | Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 17. | (Östergaard Jensen 2006) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Empirical | No | Threat | Existential threat | Suffering and reorientation |

| 18. | (Mjaaland 2007) Norway | Philosophical Norwegian | Professional article | No | Basic condition of being human being | An existential possibility as a dialectic between freedom and no freedom as Kirkegaard regards as basic condition of the human being | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 19. | (Nyström 2007) Sweden | Nursing English | Philosophical | No | Human needs, emotions, visions, possibilities Interpersonal | Existential—as human needs, frustration, dreams, possibilities Existen tial philosophy converted to lifeworldhermeneutics by Heidegger/Gadamer | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 20. | (Ausker et al. 2008) Denmark | Health care workers, researchers | Empirical | No | Religious and existential Meaning | Religious and existential thoughts Existential questions and meaning | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 21. | (Barremo et al. 2008) Sweden | Nursing Health professions Swedish | Systematic literature review | No | Suffering | Existential questions as adjustments to new meaning Existential suffering | Meaning and meaninglessness Suffering and reorientation Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 22. | (Fleischer and Jessen 2008) Denmark | Healthcare workers Danish | Professional article | No | Aging Transfers in life | Existential questions related to be older Who am I? What is the meaning of life? Where am I going? Why is the disorder a part of my life? | Existential questions as approaches for care Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 23. | (Holmgaard Thygesen and Appel Esbensen 2008) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Empirical | No | Problems | Existential problems | Suffering and reorientation |

| 24. | (Meiers and Brauer 2008) | Nursing English | Theoretical—conceptualization | No | Philosophy | Existential philosophy is understood as the basic underlying lens guiding the nurse in taking an existential caring orientation as depicted in the resultant conceptualization | Existential philosophy as an understanding of health and illness Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 25. | (Olesen 2008) Denmark | Physiotherapist Danish | Professional article | No | Philosophy | Existence philosophy Existential themes | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 26. | (Ribe 2008) Norway | Health professionals Norwegian | Professional article | No | Existential suffering | Existential crisis | Suffering and reorientation |

| 27. | (Schärfe and Rosenkvist 2008) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Professional article | No | Questions | Existential questions Existential and religious search | Existential questions as approaches for care Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts |

| 28. | (Stålhandske 2008) Sweden | Healthcare professions Swedish | Professional article | No | Existential experiences | Existential experiences in a secular context | Suffering and reorientation |

| 29. | (Berg 2009) Norway | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Being Meaning | Existential approach focuses on “the human-being in the world” and individuals’ understanding of their being and the meaning they give their life. | Existential philosophy in relation to health Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 30. | (Borge and Rolfsnes 2009) Norway | Health professions Chaplaincy Norwegian | Empirical | No | Spiritual and existential questions | The dialog with pastors’ space for spiritual and existential questions | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 31. | (Enderlein 2009) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Professional article | No | Questions | Existential questions Meaning Existential anxiety | Existential questions as approaches for care Meaning and meaninglessness Suffering and reorientation |

| 32. | (Gudmannsdottir and Halldorsdottir 2009) Iceland | Nursing home residents living with chronic pain English | Empirical | No | Pain | The authors explore chronic pain and argue that chronic pain must be seen as closely related existential pain and suffering. | Suffering and reorientation |

| 33. | (Helle-Valle and Binder 2009) Norway | Psychology English | A phenomenological analysis of a literary work in light of psychology | No | Playfulness, selfassertion, insecurity, curiosity and more | An exploration of existential and phenomenological themes in Alice in Wonderland analyzed in light of psychology | Humanistic psychology and theories of selfexperience |

| 34. | (Hammerlin 2010) Norway | Sociology, suicide prevention Norwegian | Scientific essay | No | Suffering | Existential suffering is complex and the result of societal and individual factors. | Suffering and reorientation |

| 35. | (Jonsen et al. 2010) Sweden | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Meaning Pair | Meaning of existence, death, choice and retirement Frankl’s existential theory | Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 36. | (Jystad and Bongaard 2010) Norway | Parents who have lost a child Norwegian | Empirical | No | Loss Questions Meaning | The loss of a child triggers existential questions and existential challenges. These are related to the loss/continuing bond with the child, the question of guilt, of embodied grief, relationship to others and finding meaning in grief. | Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 37. | (Arman et al. 2011, p. 300) Sweden | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Burnout Deficiency meaning | “Existential deficiencies” as part of the lived experience for people with burnout. Existential “blindness” and reflection that can be seen as avoiding one suffering. Burnout implies a “lack of conscious reflection on existential issues such as the meaning of life and existence” Katie Eriksson’s theory which sees health as an ontological condition where spiritual and existential/universal dimensions are crucial | Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness Existential questions as approaches for care Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts |

| 38. | (Bjelland and Severinsson 2011) Norway | Nursing English | Literature review | No | Pair | “existential problems”, “existential questions”, “existential care”, etc | (Only pair) |

| 39. | (DeMarinis 2011) Sweden | Psychiatry and mental health Swedish | Theoretical with one empirical case | No | Meaning Existential information | Existential meaning is tied to religion and spirituality. ” Existential information” as part of cultural perspective is vital for understanding what is providing meaning t a person’s life. | Meaning and meaninglessness Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Existential questions as approaches for care Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 40. | (Poulsen 2011) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Professional article | No | Existential/religious | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts | |

| 41. | (Bondevik 2012) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Empirical | No | Questions | Dialogue about existential questions, Death | Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 42. | (Ekblad et al. 2012) Sweden | Mental health among seekers of asylum and refugees Swedish | Empirical | No | Meaning | Existential meaningfulness is essential for providing health for refugees | Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 43. | (Grelland 2012) Norway | Philosophy and psychology Norwegian | Theoretical | No | Anxiety in light of existential philosophy | Existential anxiety is understood in the theories of Kierkegaard, Heidegger and Sartre. | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 44. | (Rehnsfeldt and Arman 2012) Norway, Sweden | Health professions Researchers in the field English | Empirical | No | Pair | Existential health perspective existential and relational aspects Existential distress is to see a person as being in a ‘darkness of understanding of life’. struggling can therefore be understood as an existential health process (2). | Suffering and reorientation |

| 45. | (Wang et al. 2012) Norway | Psychotherapy Self-reflective film course for adolescence Norwegian | Professional article | No | Self-reflection | Existentialistic theory (Buber) used for selfreflection | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 46. | (Binder and Hjeltnes 2013) Norway | Researchers Health care professions Nursing Norwegian | Professional article | No | Present in joy and suffering Mindfulness | Basic condition | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 47. | (Lien Hansen et al. 2013) Denmark | Nursing Danish | Empirical | No | Death, isolation, meaningsless | Death, isolation and meaninglessness as existential conditions Yalom | Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 48. | (Nielsen and Sørensen 2013) Denmark | Health professions Danish | Empirical | No | Struggle Meaning | Through one existential, inner struggle, a personal development is achieved Units of meaning as «Existential challenged» | Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 49. | (Thorsen Gonzalez 2013) Norway | Health care professions and researchers Norwegian | Empirical | No | Depression Suffering meaning | Depression as a phenomenon has an existential dimension associated with deficiency on experience of meaning | Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 50. | (Baklien and Bongaardt 2014) Norway | Health professionals Norwegian | Professional article | No | Anthropology | Phenomenological existential anthropology in psychiatry | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 51. | (Beck et al. 2014) Sweden | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Holistic | Palliative care is a holistic approach that integrates psychosocial and existential aspects in the care | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 52. | (Blegen et al. 2014) Norway | Mothers who are patients in psychiatric care Nursing English | Empirical | No | Pair In between Suffering and sources | Existential underpinning existential conditions existential assumptions existential meaning level The struggle between the darkness of suffering and their inner source of strength as mothers | Suffering and reorientation |

| 53. | (Brinkmann et al. 2014) Norway | Psychology Danish | Professional article | No | A critique of diagnostic culture with grief as example | Existential phenomenon as grief and depression. | Suffering and reorientation |

| 54. | (Dybvik et al. 2014) Norway | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Good life, meaning | Good life has a deeper meaning because it challenges the existential preconditions for life | Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 55. | (Ellingsen et al. 2014) Norway, Sweden | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Distress Loss existence, home safe | “Not knowing where to be in a time of change is like an existential cry of distress where the foothold in existence is lost.” | Suffering and reorientation |

| 56. | (Homme and Sæteren 2014) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Empirical | No | Challenges Suffer Future | The patients suffer because of the existential challenges, such as concerns for the future and the progress of the disease, loss of life possibilities, guilt and shame and concerns about death. | Suffering and reorientation |

| 57. | (Kvaal et al. 2014) Norway | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Empty Boredom | Existential dimensions | Suffering and reorientation |

| 58. | (Slåttå and Madsen 2014) Norway | Psychology Norwegian | Professional article | No | Existential psychotherapy Nature | Yalom’s i existential psychotherapy and how four existential conditions for living | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 59. | (Biong et al. 2015) Norway | Medicine, psychiatrics Norwegian | Empirical | No | Thoughts Value | Existential thoughts—the value of ones’ own life | Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 60. | (Fridh et al. 2015) Sweden | Health professions Researchers in the field English | Empirical | No | Suffering Dialogues | Advanced and progressive illness brings existential suffering to patients as an inevitable consequence of the disease and its treatment. Limited time and a lack of undisturbed spaces have been shown to be obstacles to existential dialogues with patients Existential, phenomenological tradition as described by van Manen | Suffering and reorientation Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 61. | (Hammerlin 2015) Norway | Researchers in suicidology | Professional article | No | Suffering | Existential load and possibility | Suffering and reorientation |

| 62. | (Molnes 2015) Norway | Health professional, researchers Norwegian | Empirical | No | Meaning of problems | “Spiritual care for seriously ill patients can be understood as perceiving the patient’s existential problems, listening to the meaning of these problems in the patient’s life history” | Suffering and reorientation Meaning and meaninglessness Providing care |

| 63. | (Ozolins et al. 2015) Sweden | Health care workers, Nursing, researchers English | Empirical | No | View on human being Individuals’ own life force | Anthroposophical medicine and care take account of humanity and human existence as a whole. Existential nature, as an omnipresent human vulnerability. | Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 64. | (Sjursen et al. 2015) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Empirical | No | Crisis | Existential crisis of the patient, the courage to make the patient face his or her own ability to cope and find strength to carry on and finally | Suffering and reorientation |

| 65. | (Solvoll 2016) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Professional article | No | Dilemma | Relatives may experience the situation strongly existential, being stuck in dilemmas, thus making them less responsive to the actions of the nurses. | Suffering and reorientation Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 66. | (Sörbye and Brunborg 2015) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Empirical | No | Spiritual existential | In Norwegian literature it is common to use the word spiritual/existential | 1,demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts |

| 67. | (DeMarinis 2016) Sweden | Mental health workers English | Professional article | No | Meaning | Rituals and existential meaning making processes in a cultural context | Meaning and meaninglessness |

| 68. | (Lid et al. 2016) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Empirical | No | Community Pair Source | Existential community The existential in the patient Existential in the togetherness Existential and touching in life Existential nursing | (Only pair) |

| 69. | (Rehnsfeldt and Arman 2016) Norway, Sweden | Nursing Health care workers and researchers English | Empirical | No | Pair | “existential strain”, “existential challenges”, “existential wounds”, Existential processes are natural, contains paradoxes (e.g., Life- death, meaning, meaninglessness) ‘existential life issues’ refers to the existential questioning of life values, priorities, people’s relationships with each other and the importance of health, suffering, love and death | Meaning and meaninglessness Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 70. | (Rykkje 2016) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Literature study | No | Spirituality and existential meaning question | In old age, spirituality and existential issues may become salient Existential and spiritual questions The meaning of life and the existential in the form of the circle of life | Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Meaning and meaninglessness Existential questions as approaches for care |

| 71. | (Hemberg 2017) Finland | Health care workers and researchers English | Empirical | No | Pain | Existential pain | Suffering and reorientation |

| 72. | (Rehnsfeldt et al. 2017) Norway/Sweden/Finland | Nursing Health care workers and researchers English | Theoretical | No | Health is at stake | Being a patient is mostly an existential condition where health or even life is at stake, and the patient suffers as a result | Suffering and reorientation |

| 73. | (Andermo et al. 2018) Sweden | Researchers Health care workers English | Empirical | Basis in life | Existential suffering and health means to pay attention to …experiences of significant meaning in their life. The term existential refers to our basis in life | Suffering and reorientation Existential philosophy in relation to health | |

| 74. | (Berland et al. 2018) Norway | Nursing Norwegian | Empirical | No | Loss Transition | The existential impact on age related loss | Suffering and reorientation |

| 75. | (Hemberg et al. 2018) Finland | Nursing English | Empirical | No | Suffering loneliness | Existential loneliness (34) can arise if an individual cannot find ways to deal with loneliness or find peace by listening to his/her inner voice. | Suffering and reorientation |

| 76. | (Hvidt et al. 2018, p. 272) Denmark | Health care workers and researchers Danish | Scientific debate article | Partly, see rubric for exemplars | Existential Spiritual | The National Board of Health therefore also translates spiritual care in not one but two words: existential and spiritual (care), precisely because spiritual as term both contain an existential dimension of meaning and orientation as well as human life’s own inner dynamics, it inner life The existential …a broad category… A factor analysis indicated four understandings of the existential: 1. Essential meaning of life, 2. Spirituality, 3. Existential thinking, oriented about philosophical traditions, and 4. Crisis management. («det eksistentielle …en meget bred kategori…Faktoranalysen indikerede her fire forståelser af det eksistentielle: 1. Essentiel livsmening, 2. Spiritualitet, 3. Eksistentiel tænkning, orienteret om filosofiske traditioner, samt 4. Krisehåndtering») People find meaning in primarily three existential domains of meaning: Secular (not spiritual nor religious, for instance the significance of family or the work), spiritual (the inner spiritual life, for instance meditation, experienced connectedness with nature or the univers), and religious (understood as beliefs one shares and practices with others, typically on the basis of holy scriptures such as the Bible) » («… mennesker finder mening i tre primære eksistentielle meningsdomæner: sekulære (hverken spirituelle eller religiøse, fx familiens eller arbejdets betydning), spirituelle/åndelige (det indre åndelige liv, fx meditation, oplevet forbindelse med natur eller univers) og religiøse (forstået som overbevisninger, man deler og praktiserer med andre, typisk på basis af hellige skrifter som Bibelen).») | Meaning and meaninglessness Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts Existential questions as approaches for care Existential philosophy in relation to health |

| 77. | (Jakobsen and Hvidt 2018) Denmark | Health care workers, researchers | Empirical | No | Existential and spiritual care are defined by Stifoss Hansen and Kallenberg as “to pay attention to the patient’s existential and spiritual questions and resources. To listen to the opinion they have in the patient’s life history, and to assist the patient in his/her work with existential questions based on his/her own view of life | Existential questions as approaches for care Meaning and meaninglessness Usage and demarcation of existential, spiritual, and religious concepts | |