Abstract

Life Scripts and Counter Scripts are used to illustrate the struggle by Israel’s Nationalist-Ultra-Orthodox Rabbinical authorities within the Zionist-religious community against military service for women. Following years in which the army had been out of bounds for the normative life scripts of the community’s women, the enlistment of women was relatively legitimized and normalized (although still far from becoming mainstream). These women identified an epistemic community that enabled them to establish life scripts offering community logics by which military service is perceived as empowering and offering positive capital and meaning. Conversely, leaders of conservative organizations within the Zionist-religious community, identifying the enlistment of women as a threat to the essentially religious-chauvinistic community order, embarked upon an internal campaign aimed at preventing it. This campaign can be seen as an attempt to establish a ‘counter script’ to the women’s enlistment script. It does not attempt to convince based on religious logics but by refuting beliefs formed as part of the script the women imagined would become their reality after they enlist. The paper analyzes a specific discourse arena taking part in the campaign—that of online videos distributed on YouTube and social media, aiming to influence attitudes. We conclude that, despite attempts to establish counter-scripts, by definition, these initiatives consist of an admission of weakness by the religious-rabbinical authority, as its very need to distribute these videos points to a double-bind and an ‘own-goal’ of sorts for the conservative authorities within religious-nationalist society.

1. Introduction

This study examines online videos produced by Nationalist-Ultra-Orthodox Jewish organizations in Israel in an aim to dissuade young women within the Zionist-religious community from enlisting in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Using the theoretical framework of normative communal life scripts ratifying the hegemonic community order versus its opponents who hold the potential of undermining it, the paper will present these online videos as consisting of ‘counter scripts’ to the cognitive ones held by young women preparing to join the army. As will be described, these are initiatives by organizations representing the conservative rabbinical leadership in a religious society undergoing modernization and feminization processes. In practice, these transitions can be noted in the growing numbers of young women wishing to fulfil their civil duty to join the army at the age of 18—despite strong opposition by the rabbinical establishment—rather than to take advantage of their community right (i.e., ‘the normative community script’) to avoid military service and replace it by a ‘national service’ consisting of civil service in the community.

2. The Corpus of the Study

The examined videos against enlistment of national-religious young women were produced between the years 2017 and 2021 by three organizations representing the most conservative discourse in the religious-national population: Brothers in Arms [לנשק אחים]—Promoting the IDF’s Strength (established in 2005); The IDF Fortitude Forum (IFF) [הפורום לחוסן צה”ל] (established in 2006); Chotam [חותם]—Judaism on the Agenda (established in 2013). The struggle against military service for women covers a large portion of the agenda of the three organizations, as can be deducted from special items dedicated to the topic on their websites, Facebook pages, and video materials. Although this had not been their original purpose, in recent years, these organizations have also initiated the production of online videos distributed on YouTube and on social media as a sort of alternative media channel, raising voices not normally represented by central media channels (Al-Rawi 2015, p. 263). These are short (1.5 to 3 min) videos characterized by a narrative structure (they tell a story), typical televisual and cinematic contexts, and stylistically presenting a combination of animation and photography (video or stills). The various common attributes in these videos, as well as their recurring themes, point to their forming a distinct discourse within a struggle that spans a range of cultural arenas.

3. Methods

The paper relies on an interpretive reading of the online videos included in the corpus. Our analysis focuses on their narrative and stylistic construction, the formation of characters and central themes, as well as further components commonly used in cinema and television studies (Elmezeny et al. 2018; Hunting 2021). We will then present the attempt of the video initiators to create a counter script by which young women are shown how their enlisting in the IDF would in fact not enable them to realize their normative life script as women who are part of the religious-nationalist community—on the personal, community and national levels, through the rhetorical power of narrative audio-visual representation (Nichols 2008, p. 78).

4. Structure

The first part of the paper presents the theoretical framework of the life and counter scripts, while the second part outlines the historical background of the polemic on women’s military service in the religious nationalist community. Finally, in the third part of the paper we examine the corpus of online videos, presenting them as a contemporary struggle arena in which conservative circles struggle against the community on the preservation of its patriarchal nature. Hence, they attempt to preserve themselves, at least de facto, as an epistemic authority for the young women of the community and, in doing so, preserve the leadership capital ascribed to them by their community (Lebel 2014).

5. Individual and Community Life Scripts

According to the ‘Life scripts’ theory developed by Eric Berne, individuals hold realistic scripts that, in their view, would become a reality as a result of decisions made. These scripts are an outcome of the primal dramas and implicit protocols of infancy, imprinting into us a self-regulation and psychological organization of our range of experiences into a clear system of expectations as to what will occur as a result of our behaviors and decisions. This implies that, regarding many issues, the individual lives according to a ‘flow chart’: a series of implications that he or she assumes would take place due to their own, or their environment’s, behavioral patterns (Berne 1961, 1972). The advantage of living according to these life scripts is a reduction in uncertainty and ambivalence while enabling decision making in many areas (Erskine 2009). Later studies have shown that the source of all life scripts is community. The individual, in fact, is a construct of his or her community scripts which, although they are not presented as such, can still be identified due to the minimal extent of deviations from them and the fact that most community members who are exposed to its institutions hold these scripts as facts (Hanitzch and Vos 2017). Hence, individuals belonging to the same community, and are thus organized around what Vos and Hanitzch refer to as ‘Stable Discursive Scripts’ (Hanitzch and Vos 2017), not only hold similar flow charts ascribing similar scripts to the same decisions, but also ‘Normative Scripts’ ascribing similar moral levels to the same decisions (for instance, on matters pertaining to sexuality; feminine or masculine behavior; heterosexual behavior, etc.) (Fishman and Mamo 2002). While these scripts are not explicitly learned, community members take part in their copying, preserving, and most of all, in expecting their realization. These may be scripts for correct behavior during a date, adolescence scripts, emotional expression scripts, career scripts, and much more. A central outcome of community scripts is that individuals who do not follow them are marked in the community discourse as deviants (Husband 2007).

As the adoption of a ‘normative script’ corresponds with the communal belief system (Hanitzch and Vos 2017, p. 120) and ‘community scripts’ serve to reproduce communal order, community institutions are in fact the leading agents responsible for distributing the scripts as well as excluding ‘counter scripts’ that would undermine the hegemonic community order (Hanitzch and Vos 2017, p. 121). Hence, these community agents mark those who attempt to ‘refashion cognitive scripts’ as their worst enemies (Hanitzch and Vos 2017, pp. 121–2). Various studies have explored these institutions responsible for preserving normative community scripts. Some identified the Nation State as one such institution (De Cillia et al. 1999), while others identified political culture (Hanitzch and Vos 2017, p. 121); some identified professions (Hanitzch and Vos 2017); most studies point to religion (through religious communities) as being the central producer of both ‘Dominant Scripts’ and ‘Dominant Life Scripts’ (Deneulin 2022).

6. Levels of Reward for Choosing the Normative Community Script

The individual’s choice of community scripts marks three different levels of reward: the first—on the personal level; the second—on the wider level—for his or her family, community, or epistemic reference group which forms his or her significant other; third—on the external and community level—in an area that grants meaning to his or her actions (whether pertaining to the State, the Nation, or the realization of a specific ideology). The three possible reward levels are intertwined, since as written by Harre following Bakhtin in his Positioning theory—the individual perceives his social status and the symbolic capital to which he is entitled as a result of the discourse to which he is exposed, offering a mirror reflection (Harre 1998). This is why Raggatt titled his seminal paper on the Positioning theory: ‘Positioning: Dialogical Voice in Mind and Culture’ (Raggatt 2015). In fact, the individual depends upon those who reflect the realization of the scripts—in the ‘mirrors’ through which he or she is gazing. Thus, if ‘community discourse managers’ (Chin 1994, p. 452) represent its contribution (through constructs, language, habitus, gestures, communicative and publicist expressions, etc.) in a way that would become the dominant communal reflection, this reflection would eventually also be adopted by the individual, who holds the ‘Communal Logic’ through which actions and decisions are evaluated. As written by Shaw et al. on the ascription of sense making: individuals who ascribe ‘sense making’ to their actions do so as part of a ‘Communal Sense Making’ (Shaw et al. 2013). This process occurs today mostly through informal discourse in messages distributed via WhatsApp groups and online videos—where the actions of individuals, trends, and modes of activity are framed, and ‘community messages’ obtained from these means are stronger than those that can be obtained from traditional media (ibid.).

7. Counter Script

When promoters attempt to undermine the decisions of individuals, they invest in exposing them to counter scripts—to the discourse in which scripts resulting from their decisions and actions lead to the opposite results than those expected, on all possible reward levels—the personal, communal, and collective-symbolic. Parks refers to this process as ‘Alternative Collective Sensemaking’ (Parks 2020). One of the most influential studies pertaining to counter scripts is by Gutierrez et al. (1995) on knowledge, teachers, and studies. As researchers focusing on the communication between students and teachers, the three authors described the knowledge transferred to students by their teachers as offering dominant scripts. The status of the teacher, his leadership, and the legitimation to listen and learn from him, are based in fact on the scripts which the teacher has forecasted will become reality. However, as described by the group of researchers—at certain points, students may raise alternative counter scripts, whether due to knowledge that they hold and their teachers do not, or incidental associations resulting from error or deviation in understanding the subject matter which led to a different decision than that intended by the teacher, one that did not result in a crisis but a positive outcome. Upon the occurrence of such a positive counter script, the teacher—as shown by the researchers—instantly loses his epistemic status to educate his students and experiences a legitimacy crisis. They found that teachers’ power relies on their being ‘authorities of the Dominant Script’ while the realization of a counter script is an undermining of their status (Tzou and Bell 2012, p. 274). Thus, the counter script leads the individual to ‘counter sensemaking’ (Simmons 2007; Mauksch 2017; Leo 2020): a doubting of the ability of his or her action to lead to the expected flow chart and, finally, to a rejection of the dominant script (Ingram 1985, p. 94). This occurs, among other reasons, because of the personal implications of the situation: the understanding that taking the same action would not lead to the expected script, but probably to the opposite one. Not only that the same decision would not enable the individual to acquire positive symbolic capital, but on top of that, it would grant him what Ben-Asher and Bokek-Cohen (2019) refer to as ‘Negative Symbolic Capital’.

8. Enlistment of Women from the Religious-Nationalist Community in the IDF—The Hegemonic Script: National Service While Remaining within the Confines of the Gated Community

Since the establishment of the IDF in 1948 the leaders of the country’s religious-nationalist groups opposed to the enlistment of the young women of their community. In 1950, during deliberations on the law enabling enlistment of women to the army, the two Chief Rabbis of Israel published a Halakhic prohibition on the military service of women (Budaie-Hyman 2016, p. 76). This, in turn, served as grounds for the demand by religious parties to exempt all religious young women from military service, thereby leading to the institutionalization of a ‘dominant communal life script’ for all religious-nationalist young women, by which they know that upon completing high school they would not enlist in the army, but instead sign a ‘declaration’—an arrangement by which from the moment the girl declares that she leads a religious lifestyle (by filling a form at her school, which is then sent to the army), she is immediately granted an exemption from military service (Bick 2016). This in fact is a ‘normative bureaucratic script’ (Neumann 2005) which constructs a ‘normative life script’ (Coleman 2014) that entails a price, as these young women would not be able to convert the Israeli military capital (Swed and Butler 2015) into social, occupational, symbolic, or leadership capital, as is routinely done by secular Israeli young women and as is indeed done by religious men in their own communities (Lebel 2016).

Instead of a customary military service, these religious-nationalist young women will serve a ‘national service’ in which they provide support to civil organizations, in suitable environments, alongside other religious young women like them. This status enables the leaders of the religious-nationalist community to maintain these young women within a gated and immune space (Lebel 2016). They perceive military service as a threefold risk: exposure to secular life; mixed service with men; most of all—possible placement in ‘masculine’ positions which deviate from the communal-religious tracking to ‘feminine’ roles or scripts, in which these young women are, in fact, positioned in their national service. To this end, the Zionist-religious community invests continuous efforts in the preservation of a ‘gender regime’ (Lombardo and Alonso 2020) which, while encouraging religious boys to enlist in combat military service and, as a result, integrate in key positions in Israeli society, it does not permit the same for its young women. Moreover, the fact that these young women do not serve in the army means that they cannot convert military capital into civil capital, which enables expression of agendas in various areas—a resource that is readily available to military draftees, soldiers in active service (who sign refusal petitions), or veteran officers who lead social movements—as Israel’s military capital is, in fact, comprised of both leadership and symbolic capital (Barak-Erez 2007; Lebel and Hatuka 2016).

9. The Revolution of the Enlistment of Young Religious Women and the Evolution of a Rewarding Military Service Script for These Young Women

In the beginning of the current decade, when it became clear that the military enlistment of young men through pre-military preparatory seminaries had been a transformative experience for these young recruits—an empowering experience on all possible levels—a trend began in which this process was copied among young women. This idea had become possible due to the penetration of feminist concepts into the religious-nationalist community, as well as that of the intent to integrate in the army as an internal-religious bargaining in the gender arena (Rosman-Stollman 2018a).

It is important to note that we are not referring here to a revolution by which religious girls aim to enlist in the army so as to ‘become men’, but rather to a new ‘Jewish Religious Feminism’ (Yanay-Ventura and Yanay 2016): a trend that rejects the dichotomy between religiousness and feminism. In this new feminism, contrary to the ‘first wave’ of feminism, the mission of feminist women in religious communities is not perceived as a rebellion against the differentiation in the tracking of men and women in the various arenas, and certainly not as an undermining of the social-community order in the religious arena which relies on respecting the authority of the epistemic rabbinical leadership (Yanay-Ventura 2016). Rather, we are referring to an aspiration to legitimize female accessibility to power arenas where religious men are also present, although certainly not to the same roles and while not aiming to acquire masculine attributes. As is the practice of the second generation of feminism (Gilmore 2008), the effort here aims to gain the ability to obtain accessibility to the same public power arenas as men, and thus to gain female capital which is convertible to civil capital (whether political, leadership or symbolic) in the public arena, while understanding that this capital would still differ from that which is reserved exclusively for men. It should further be noted that this type of feminism—implemented by the religious girls in their decision to enlist in the army—has complicated things for its opponents within the religious community, as they were unable to present these girls as aiming to import into their religious-conservative society a feminist-liberal ethos which may threaten the representation of the feminine image of the girl/women in religious Zionist society.

To promote such a process, seminaries and religious pre-military preparatory seminaries for young women were founded (paralleling the dozens of existing religious pre-military preparatory seminaries for boys), which invited young women wishing to enlist in the army to a military service preparatory year in which they would experience religious, personal, and feminine community empowering. Using ‘life scripts’ terms we can say that for the first time ever, these institutions enabled the establishment of counter-hegemonic life scripts within the religious-nationalist community on the matter of military service for women. These new ‘enlistment scripts’ for young women relied on three levels, all of which are still positioned within the conservative gendered borders of the community: the promise of a golden opportunity for personal change—that would empower the girl individually; on the communal-familiar level—that it would transform attitudes towards her by her environment—providing her with the same treatment that, until then, had been reserved to boys who joined the army; on the national-collective level—an opportunity to find national meaning in a military service that would contribute to their country and its security.

9.1. The Personal Level: The Personal Capital of Military Service: Personal Empowerment in the Army

Just like the young men of their community—women too wished to face, through military service, an experience of maturation, which as many studies on Israeli military service have shown accompanies those who serve (Dar and Kimhi 2000)—an experience of empowerment, growth, and personal development in a range of areas, not so as to blur the gendered borders of the community, but so as to empower its women. Michal Nagen, founder of the first religious pre-military academy for young women expressed this notion when saying that “Our goal is to take girls who were taught to avert their gaze and convert them into forward looking officers in long skirts. From this perspective the IDF is indeed a tool of sorts” (Slovik and Voll 2012). In the graduation ceremony of the first class of the academy she spoke to the graduates, saying that: “You are the leaders of the next generation. Without you we have no future” (Kaplan 2007). This marked a dramatic revolution in the way in which women are treated in the Zionist-religious community. In fact, young women who chose to enlist in the army perceived their military service as such that would provide them with a life script that is parallel to that of men in the religious-nationalist society: one that would lead to a complete transformation of the normative community script expected of them—the roles to which they are tracked—but most of all, the Israeli script that is now expected to be a part of their lives (the ways in which Israeli society perceives religious women). They hoped that just as do young religious men in their society following their military service—they too would be able to convert military capital into social capital, leadership capital, financial capital, business capital, political capital, and most of all ‘Israeli capital’, and undergo a complete process of Israelization. In other words—completely transform their feminine positioning within the community: the communal one, the national one, but most of all, the personal one—the way in which they began perceiving themselves in their own eyes. This was not done in secret. Yifat Sela, CEO of “Aluma” association that strives to promote military recruitment of religious-nationalist young women, explicitly stated the organization’s goals: “This is the entry ticket to Israeli society. A woman who has been a company commander… or served in the Intelligence corps, will no longer reduce herself to traditional professions such as teacher or nurse. She can now perceive of herself as a bank manager, or hi-tech professional. Success for me is that young religious women are positioned where they want to be, rather than where they were tracked to be at” (Artzi-Sror 2017). The message was clear: a woman who enlists in the army would be able to cope with many challenges—in the army and after it—thanks to empowerment and maturation processes that she will have endured. She would no longer remain the religious girl which the Zionist-religious community had kept for years within the private arena while only boys were tracked to become men and go out to the public sphere.

9.2. The Community Level: Religious Capital in Military Service: A Communal Legitimacy That Follows Religious Legitimacy

The message was that, similarly to men, women in the army would gain collective capital (both familial and communal) that would mark them as the best of their community, mainly due to their ability to maintain a religious life style while opting not to give up military service. To this end, all the while an emphasis was made on components showing just how much the new recruits persist in a religious life style throughout their military service. This was achieved through classes offered by the academy staff during military service, or during their time at the academy itself, which served as an arena of ‘immunized integration’ (Lebel 2016). As illustrated by Roni, an academy graduate who served in the IDF: “Until Officers Course I wore pants. Once I decided to become an officer I decided to wear a long skirt. I realized that when I become a religious officer in the IDF, the way I represent myself has an even greater meaning and that I am looked at with even more scrutiny. You could say that [my religiousness] became even stronger in the army” (Slovik and Voll 2012).

A further expression of community legitimacy to recruit women can be found in the book Shalom Becheileich—a halakhic guidebook for religious women in the IDF, published by Rabbi Eli Reiff who is a teacher at the Tzahali pre-military academy for young women. While it appears at first to be one of many books offering answers to halakhic questions relevant to daily military life, in fact its publication poses a true precedent—as contrary to many other books intended for boys only, this book is dedicated to female recruits, and its very existence is a significant step in the normalization of the recruitment of religious women and in ensuring the script of their ability to cope with the challenges of maintaining a religious life style in the army. This is even more true due to the biography of the author: Rabbi Reiff taught in the past in an arrangement Yeshiva for boys, works in a research institute for religious literature, and is the editor of the books of Rabbi Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch, head of the “Birkat Moshe” Yeshiva, who had even granted his endorsement for the book, emphasizing that while he still opposes women’s military service, he realizes that it exists and therefore it is important to make sure it is done while observing a religious life style (Hollander 2017).

Further community support for the army enlistment script in the religious context was organized from within the army itself. In 2009, especially for female religious recruits, the Military Rabbinate initiated a special department named ‘Bat Chayil’ (“daughter of valor”), led by a female religious officer whose job is to support religious soldiers during their military service. The female soldiers serving at the department are ‘Jewish trustees’—located at all units in which religious women serve, ensuring their service conditions, providing consulting services to the soldier and her commanders, maintaining contact with her and her family, as well as with religious associations which provide her with religious services while in the army, and more (Slovik and Voll 2012). This, of course, further reinforces the promise that the women’s community would be proud of those recruits whose religiousness is not even slightly compromised in the army.

9.3. The National Level: Military Service as National Capital: Taking Part in Fortifying Israel’s Security

Similarly to that of men, the military recruitment script for women is supported by a range of columns and positions by intellectuals and opinion leaders within the Zionist religious community who clearly state that the enlistment of women—not only is legitimate from a religious and personal perspective, but moreover is a meaningful step having strong religious, military and national implications.

In these written texts we see liberal rabbis who have framed the recruitment of young women similarly to the way in which they had that of the young men of the community—as a way to take part in the religious command of contributing to the security of the State of Israel, the protection of which is held to be a Milḥemet Mitzvah (War by commandment) (Budaie-Hyman 2016, p. 86). We will not detail all of them here, only to note that this had not only involved the identification of meaning but also a passion for positioning in the national arena, since, for instance, from the moment the general public became aware of the integration of settlers in the army’s combat units, despite its general apprehension of the settlements—at once the levels of public empathy towards settlers increased (Lebel 2015). Thus, military service in Israeli society is, by definition, a leverage of appreciation leading to a process that links between public positioning and personal sense of appreciation, which, in turn, connects between the three levels presented.

As aforesaid, the intent to reproduce the success of Pre-military preparatory seminaries for boys in Zionist-religious society, was not at all about creating masculine warriors, but rather about their success in functioning as ‘Launching Pads’—from which graduates are ‘launched’ not only to the army but also to their post-army life, possessing the social, professional, leadership, and symbolic capital needed for inclusion in key positions in Israeli society, while in parallel completely transforming attitudes towards them within Zionist-religious society as they become its ambassadors in general (secular) society (Lebel 2015).

10. Opposition to Enlistment Scripts and Their Reliance on Communal-Religious Logics

Since the enlistment of young religious women began, rabbis of the religious nationalist sector—the community hegemony—began to publicly express their firm opposition towards this practice. They did this at first by adhering to religious logics. By organizing a range of conferences, writing publicist columns, and issuing religious edicts, they reiterated over and over that military enlistment (of women) is a blatant religious offence. For instance, rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu, member of the Chief Rabbinate Council sent the following message to principles of seminaries for religious girls: “The military service in unsuitable for a daughter of Israel… the military service causes girls very severe moral and religious damage” (Adamker 2013). Similarly, in a conference organized in 2014 by the Religious Education Administration at the Reut seminary for girls in Petach Tikva on this topic, Rabbi Yaacov Ariel, one of the leading adjudicators in religious Zionism, referred to the rabbis who had permitted young women to enlist in the army as “Irresponsible…similarly to the occurrence of the beginning of reform” (Puterkovsky 2014). Rabbi Yehuda Deri, the Rabbi of the city of Beer Sheva, stated that “It is better to die than agree to military service [for women]” (Yehoshua 2014), while Rabbi Shlomo Aviner, one of the leading publicists and opinion leaders of religious Zionism ruled that “Military service for girls… is prohibited by Halacha… if there are a few individual rabbis who have expressed a different opinion…they are not reputable adjudicators and their opinion is void”. Rabbi Aviner specifically emphasized that in military service [for women]: “The main damage is the damage to the soul that transgresses against the will of god” (Peretz 2013). Three years later, when Aviner realized that the flow of female religious recruits continues, he referred to them as ‘sinners’, emphasizing that their joining the army results from a blurring of the difference between idol worship and the work of god (Aviner 2015). He was surpassed only by Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu the rabbi of the city of Zafed, who identified women in the army as no less than “a part of the erasure of Israel’s identity as a Jewish State” (Ettinger 2015).

11. The Futility of Religious Logics

Despite rabbinical voices—more and more religious women could be found in the army. According to the Knesset research department, 2015 saw a 14% growth rate each year (Avgar 2017), amounting to over a quarter of potential female recruits (Lotan and Worgen 2017). Moreover, during the same period, a 30% increase in the number of religious female IDF officers was also noted (Ettinger 2015). This trend marks an even more extreme deviation from the normative life script planned for religious women, being an opening for a military career, rather than only a short term service. As these young women came from the most prestigious education institutions of the religious-nationalist community (Budaie-Hyman 2016, p. 86) they could not be framed as part of marginal or weak populations in terms of their religiousness, having studied at institutions led by the most central, legitimate, and normally, also the most conservative rabbis of the community.

In practice, as illustrated by Rosman-Stollman in her studies, we see a continuous process of ascription of community legitimacy to the recruiting of young women to military service (Rosman-Stollman 2018a). While the phenomenon did not become a mainstream script, it did become one that is in a state of constant bargaining rather than constant exclusion (Rosman-Stollman 2018b). Using the language of social representations, we can argue that, in the religious Zionist community itself, the representation of a young woman in uniform, and moreover one who holds arms (and hence is not serving in a ‘feminine’ rear position), is yet to become the ‘hegemonic social construct’, but nevertheless has evolved from being a ‘counter hegemonic representation’ to a ‘polemic representation’ (Ben-Asher and Lebel 2010; Farah Bidjari 2011).

In the past decade, a number of female IDF recruits have established themselves as role models (whether due to their high rank or a heroic act that gained media coverage). The most prominent of these women became ‘local heroes’ for others wishing to walk in their paths (Rosman-Stollman 2018b). The ultimate example of this is Tamar Ariel—a pilot which even before her death (a fact that only contributed to the empowerment of the myth and led to the first pre-military academy for young women being called after her)—became an admired and groundbreaking heroine in religious nationalist society (Artzi-Sror 2017). In her last interview—which is available online and went viral after her death—she said: “Halachic ruling is important to me but apparently not enough. This would not prevent me from realizing my dream of flying” (Erlich 2016). In her words, she gave legitimation to the young women of the community to form their life’s script on their own, rather than through rabbis. It seems that this example can serve to explain the moral panic of the community’s rabbis who rushed to initiate a range of campaigns in an attempt to prevent the recruiting of young women, which, in their eyes, undermines the communal order organized around obedience to the rabbis and respecting their authority. In a pioneering study, Budaie-Hyman found that around 50% of religious women in the army do not ascribe special importance to rabbinical positions against their service (Budaie-Hyman 2016). Moreover, contrary to the rabbis’ horror scenarios—most women, in fact, do finish their military serving at the same or higher level of religiousness than they had when they entered the army (ibid.; Artzi-Sror 2017; Yehoshua 2018). This fact is a ‘counter script’ that refutes the rabbis’ threats that the army would lead religious women to abandon their faith. Despite the above, the bargaining on the question of religious women in the army continues, with one of the current struggle arenas being that of online videos.

12. Online Videos Opposing Military Service for Women and the Attempt to Establish Non-Rewarding Counter-Scripts

In this section, we focus on a corpus of videos promoted on YouTube and other social media channels (Facebook), aimed at diverting young women belonging to the religious-nationalist community from enlisting in the army. As part of the struggle by traditionalist gatekeepers of the Zionist religious community against the enlisting of young women and following the failure of a range of campaigns that established their opposition based on religious logics, Nationalist Ultra-Orthodox agents turned to online videos, which can be classified based on the three reward levels to which they are directed and which they aim to refute:

- Counter script for personal capital reward from military service

- Counter script for collective capital reward (communal-familial-religious) from military service

- Counter script for national-symbolic capital reward from military service

For each of the categories we will illustrate their arguments and rhetorical structuring by analyzing those videos that describe them in the clearest manner.

12.1. Counter Script for Personal Capital Gained from Military Service: Personal Empowerment in the Army

This counter script, as depicted and exposed in the videos, includes two components: a psychosocial counter component focusing on the maturation process; a counter script focusing on physiological empowerment and the erotic capital it entails.

12.1.1. The Psychosocial Component: Undermining the Empowerment of Maturation

A central case study for the psychological component of the personal capital counter script achieved in the enlistment of young women in the army is found in the video entitled: ‘Alone in battle—the story of a religious [female] soldier’ (Figure 1) (2017). This video turns against the promise of military service as an experience of maturation and empowerment, or as defined by Michal Nagen, founder of the first pre-military academy for young women: “An opportunity to fight the community identity of clipped winged girls“. As described in its title, the video depicts a young religious woman—graduating from high school, through her military service, and finally, her wish to be discharged from the disappointing military system. The video aims to show that a religious girl in the army would be no more than a little girl in a patriarchal adult world—alone and helpless.

Figure 1.

‘Alone in battle—the story of a religious [female] soldier’ (January 2017). [Hebrew wording on the soldier’s hand: “shomeret negiah”, literally meaning “observant of touch,” refers to observant Jewish women who refrain from physical contact with men who are not their immediate family members.]. (Supplementary material).

The video’s main reference is popular film, as can be seen in its construction as a cinematic trailer. As such, it is narrated by a strong and authoritative male voice, which further validates its message (Bell 2011, p. 19). An even stronger validation of the message is achieved through the written phrase: “Based on a true story”—a well-known rhetoric tool used in a range of cinematic and televised genres aiming to achieve a realistic effect (Redmon 2016, pp. 16–17).

Thematically speaking, the video illustrates the military base as being a dangerous place for female religious soldiers, with the main danger being posed by male commanders. This argument is expressed in various shots presenting unequal power relations between her and them: she always fills only a small part of the frame, while the figures of the male commanders are large and block the screen in a way that enhances their physical dimensions, their supremacy over her and the danger entailed to her due to their physical proximity. Furthermore, the men shown in the video (commanders and soldiers alike) are generally presented and identified with military tools—tanks and planes.

From a stylistic viewpoint, this identification relies on the use of two distinct and opposing animation styles: while the male soldiers as well as the tanks and planes are depicted through a ‘treated photography’ realistic animation, the protagonist, as the rest of the female soldiers depicted, is always ‘hyper animated’. In fact, the animation of the protagonist is designed in a way reminiscent of Bratz dolls (Hains 2009, p. 91) or Japanese Anime characters (Horno-Lopez 2015, p. 40). This stylistic choice gives her a paper thin body and a large and disproportional head. These characteristics support the rebuttal of the psychosocial component in the personal empowerment narrative. Her large green eyes (signaling the color most identified with the IDF) empower her emotions (Horno-Lopez 2015, pp. 41–44): her strong passion to enlist and serve; her disappointment from the roles which she had been allocated; her helplessness towards many situations; her angst towards men, and most of all—her deep sorrow when she realizes that she will not be given the opportunity to make a meaningful contribution in the army. The men, on the other hand, are brown eyed, with proportional bodies, marking them as rational and free of any unrealistic fantasies about their military service. In other words, the protagonist, similarly to the other female soldiers, is depicted as a girl whose army dream is no more than an adolescent fantasy.

A similar representation establishing the depiction of the women as young girls can be found in the video ‘A tale of five declarers’ which makes reference to the classic Israeli children’s book ‘A tale of five balloons’ (2019) and is presented as a televised story-hour by a storyteller that resembles the Israeli children’s TV star Yuval Hamebulbal—both clearly secular texts.

In addition, we can identify in the girl a strong similarity and intertextuality with the character played by Uma Thurman in the film Kill Bill (Tarantino 2003). This is true not only because both are blond with green eyes, but because of the presence of martial arts scenes and the decision not to give her a name—just like Tarantino’s protagonist before her—thereby pointing to her loss of honor in both cases: in Tarantino’s film due to the loss of her status as a mother (Reilly 2007, p. 43), and in the video, due to her enlisting in the IDF—according to the religious logic of the initiators of the video. Moreover, in the martial arts scene the protagonist is presented from the waist up, leaving her skirt (a clear mark of her religiousness) outside the frame, although it is seen in other scenes.

However, while in Kill Bill the protagonist is able to establish a congruence between motherhood and martial arts and to be both a mother and a warrior—in the video, the emerging outcome is dichotomous rather than hybrid: the girl is unable to preserve her religious-communal identity alongside the military-Israeli one, which, in turn, leads to the collapse of the fantasy of her becoming an Uma Thurman-like heroine.

12.1.2. The Psychological Component: Undermining the Empowerment of Erotic Capital

Examples of videos illustrating attempts to refute the physiological component of the personal empowerment reward ‘Noa volunteers to become a fighter’ (Figure 2) and ‘The integration of women fighters—essential facts’ (Figure 3) (The IDF Fortitude Forum, 2017). In fact, these videos are part of a number of campaigns that appeared on social media and in religious newspapers and promoted the message that military service for women is a health and femininity disaster (in the gynecological context, these campaigns focused on the idea that women who served as combat soldiers are less likely to eventually become mothers, and as a result, attractive wives).

Figure 2.

‘Noa volunteers to become a fighter’ (The IDF Fortitude Forum, September 2017). [Hebrew wording in the picture: “Medical Corps”]. (Supplementary material).

Figure 3.

‘The integration of women fighters’ (The IDF Fortitude Forum, August 2017). [Hebrew wording in the picture: Top Left corner: “The Security System”; Bottom left: “Anterior cruciate ligament”, “Cruciate ligament”, “Lateral collateral ligament”; Bottom right: “Herniated Disk”, “Spinal disc herniation”] (Supplementary material).

These videos use the polemic on the enlistment of women to combat roles, which is not limited to the religious-nationalist community, as a rhetorical means for spurring the very idea of IDF enlistment of young women of the community. This is while contrary to other videos in the corpus, which focus on female soldiers or military recruits from within the religious-nationalist community, these videos refer to the recruitment of women in general and present soldiers who can be identified as secular.

These two videos are animated, with the addition of a small number of photographs, with a common composition of DIY style instruction videos for ‘feminine’ practices such as crafts and makeup, although following Hains, it may also be possible to link them to the development of the “Riot Grrrl” movement (Hains 2009, p. 97). The combination of a female narrator and the conventions of DIY training videos identified as a ‘feminine’ or ‘women’s genre’ (Kuhn 1992, p. 301) is ratified and emphasized in the videos through the use of female hands—depicting the patriarchal message of the videos as a clearly ‘feminine’ envelope, which could also point to the fact that they are speaking to a female audience.

The two videos establish their arguments against recruiting women to combat positons (and, by extension, also against the enlistment of women in general) by using a quasi-scientific discourse (Overton 2013). The data presented in them seems to be ‘official’ IDF data. This is achieved through the use of infographics depicting documents that seem to have been taken from scientific psychology and medical journals, attesting to the alleged physical risks to women serving as combat soldiers, including pelvic organ collapse, herniated disc, tearing of back and knee ligaments, and more. While these arguments are directed towards the enlistment of women in general in military combat roles, within the discourse arena of these videos, their importance for girls from the religious-nationalist community is specifically emphasized.

This presentation is stylistically validated using the rhetoric of the ‘real thing’, using the tradition of anatomical scientific illustration (Kemp 2010, pp. 192, 198) that originated with Leonardo Da Vinci’s illustrations and culminated in the 18th century, when it was used to allocate a quasi-scientific look to various reports (Massey 2017, p. 94).

The two components—rebuttal of the psychosocial mental maturation as well as the feminine-physiological one—jointly establish a counter script to religious young women’s dream that, during their military service, they would have similar experiences as religious boys, having transitioned from representing religious identities depicted as feminine and soft, to being perceived as masculine leaders and as holders of erotic, leadership, and Israeli capital following the pre-military preparatory seminaries revolution that took place within the religious-nationalist community (Lebel 2015). As aforesaid, in the context of female soldiers, the aim is to achieve female empowerment rather than a masculine structuring of the female body.

12.2. Counter Script for Religious Capital Gained from Military Service: Community Legitimacy Achieved from Religious Legitimacy

This category includes videos which undermined the promise that military service would transform the young women into local heroes of the collective arenas to which they belong, similarly to the young men who walked this path before them, whether marked as leaders of their family, community, yeshivas, or the settlements in which they had been educated, and while ascribing religious capital to their military service, even if, in practice, they did not follow all commandments, as the actual military service is perceived as a Milḥemet Mitzvah (War by commandment) which exceeds all other commandments. Similarly to the previous counter script, this one also includes two aspects—religious and familial.

12.2.1. The Religious Aspect: A Disengagement of Religion

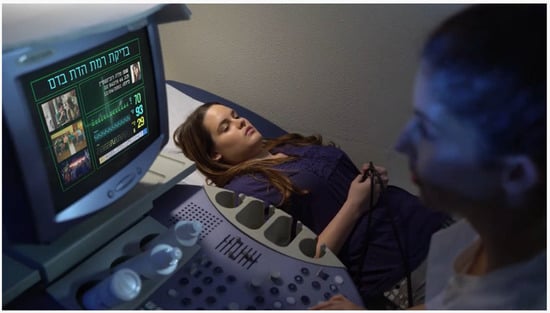

The video ‘Interview with declarers of religiousness’ (Figure 4) (2018) presents a religious girl who having declared her religiousness (so as to obtain an exemption from military service), is invited by the IDF to pass what seems, in the video, to be a test administered using a so-called “religion meter”—a sort of ultrasound device that examines a person’s religiousness level. It should be noted that historically the video had, in fact, been produced in response to the army’s demand to examine the credibility of the declarations made by religious girls seeking exemption from military service for religious reasons—but we propose analyzing it in a way that identifies messages that are certainly relevant to the campaign that presents a counter script for military service of religious women, while focusing on the communal reward of the service.

Figure 4.

‘Interview with declarers of religiousness’ (April 2018). [Hebrew wording on the monitor: “Test for level of religiousness in the blood”] (Supplementary Materials).

From a production viewpoint, this video is the only video in the corpus of this study which is entirely photographed and does not use animation. This, and the fact that it was shot on location (at a clinic) presents what seems to be a relatively high production value compared to the other videos analyzed. Similarly to the use of the phrase ‘based on a true story’ as in the ‘Alone in battle’ video, this one also opens with the title: ‘based on real questions presented to religious girls during a religion interview at the recruiting office’. Later on, the video depicts the girl’s visit to the clinic and her examination by a female physician with the device. The physician instructs her to partially undress and lay on a bed, with the procedure simulating an ultrasound examination. With growing helplessness which is further emphasized by the choice of camera angles that emphasize the balance of power between them, the girl realizes to her amazement that the device has found that she is not as religious as she had thought and that intimate details about her past are unearthed. “You call yourself religious?” the tester asks in a demeaning voice as the test concludes.

Using this narrative, the video illustrates a cinematic medical discourse that focuses on the female body, the origins of which can be found in Hollywood’s ‘Woman’s films’ of the 1940s and 50s—which addressed a female spectator (Doane 2002, p. 284), and its heroes were women (Doane 2002, p. 286), but hovering above them was a masculine viewpoint that using a masculine-medical gaze undermined women’s extent of deviation from the norm, and even held the power to commit them or distance them from society (Doane 2002, p. 290).

These films represent an arena of abuse and violence, in which even if there are other women present—there can be no ‘sisters at arms’, but the exact opposite—a misogyny and hatred between women—which, by definition, serves the patriarchal order (Tirosh 2014, p. 304). Similarly, the video gives potential recruits the message that they would not be able to serve in the army while holding onto both religious and military capital within the religious-nationalist community: Your military ‘sisters’ will tell of your deviations from religious ways, and in general—see what the army does to religious-nationalist girls. We will never allow a religious-nationalist woman in the army to become a local heroine in our community. By definition, she would be defined as ‘other’, victimized, and even perceived as an enemy. This is not a lone video. A similar one, entitled ‘A tale of five declarers’ (Figure 5) also presents the abuse encountered by girls who came to declare their religiousness and ask for an exemption from military service, but instead are confronted with embarrassing information refuting their allegations regarding the level of religiousness they ascribe to themselves.

Figure 5.

‘A tale of five declarers’ (January 2019). [Hebrew wording on the book cover depicted in the picture: “A tale of five declarers; Based on a true story”; On the military identity disc: “Declarers”] (Supplementary Materials).

Despite the fact that the video is presented as a children’s book, it too is stamped with the phrase ‘Based on a true story’.

Both videos together can be perceived as a threat of extortion: ‘May every religious female soldier who intends to hold her religiousness as a resource within the religious nationalist community know that the way will be found to refute her allegations of reinforcing her religiousness during her military service, that she had remained loyal to her religious life, did not deviate from it, and that she would not be able to enjoy this type of capital’.

12.2.2. The Familial Aspect: A Disengagement of the Family’s Functions

A third video, entitled ‘To choose correctly’ (Figure 6) (2020) pertains to the collective reward of community and religious legitimation focusing on the familial component, this time by approaching mothers of potential recruits and calling them to action. In Judaism, as in other conservative communities, the maternal institution is responsible for protecting tradition, communal and religious values, and the preservation of norms from generation to generation. The mother is assessed based on her ability to relinquish many components of her life in favor of allocating, and correctly directing, the choices made by her children (Herzog 1998). For good, and for bad, if something goes wrong, for instance if the child becomes gay, this is seen as ‘Mama’s Fault’ (Caplan 2000).

Figure 6.

‘To choose correctly’ (October 2020).

The video opens with an exterior shot of a house on a quiet street. It is evening, and in the window of the house we see the shadow of a young woman wearing a long skirt, presumably training for her military service. This opening, presenting the exterior, the house and the window, again brings to our analysis the critical reading of Hollywood’s ‘Woman’s films’ which maintained the division between the masculine space (outside) and the feminine one (inside) (Doane 2002, p. 285). The following shot is in the house itself, and the bedroom of the protagonist, who does in fact seem to be training for the army.

As the girl huffs and puffs, her mother walks into the room. “Are you still thinking of enlisting?” She asks, and the girl answers a decisive “Yes mother”, and adds, “…by the way, the book that you gave me […] is not convincing”. A close shot of the book entitled “The roles of the mother and daughter in the Jewish world” shows that it is covered with cobwebs—a testimony to its irrelevance for young women nowadays. “You can see that all the data is completely in my favor” the girl blurts out to her mother, flinging the book to the floor. In the room we see a billboard add with a historic enlistment poster (‘Enlist!’), a headline simulating the popular Israeli news website Ynet: ‘New-religious girls in the spire’, and one that simulates the well-known Israeli TV content website Mako: ‘The complete guide for the [female] religious recruit’. “Religious girls have no problems in the army”, states the girl, but the mother is doubtful. “Whose data is that? The IDF spokesman’s?” she asks, as a male figure appears on screen, in uniform and open mouthed, in what seems to be an attempt to undermine military authority itself. “To be truthful I assume that there are problems, but I want to be a part of it” explains the girl. The room behind her transforms into a military base with a guard tower, a flag, a tank and a few male soldiers. When she adds that she ‘wants to sanctify Heaven in the skies’ (which religious women would recognize immediately as being a reference to the late Tamar Ariel), the picture changes again and she is a pilot. In an attempt to ‘ground’ the girl, the last part of the video, for the first time in our corpus, turns to the mothers. “Mother, do you want to help your daughter choose correctly?” asks a female narrator, promising “tools and extensive information” that will assist in directing daughters in “making the right choice”.

This can be seen as a development of the motherhood drama that is at the center of many Woman’s films and exposes the heavy prices demanded of women in their role as “good mothers” (Williams 2000, p. 479). Similarly, the video reminds mothers that alongside the temptation to be there with her daughter in the excitement of enlisting, it may be that the right thing to do, even if this would not be appreciated by the daughter in real time, is to do everything in her power to prevent her daughter’s enlistment, as is expected of one who is not a friend, but a mother.

12.3. Counter Script for National Capital Gained from Military Service: A Partnership Reinforcing Israel’s Security

The videos representing the third counter script category pertain to one of the most central themes: the pretense that, by their enlisting in the army, religious young women will make a viable contribution and, similarly to the boys, would contribute to the nation’s security. The most representative example of this script is the video entitled ‘A folk tale—Who wants to weaken the IDF?’ (Figure 7) (2017), which directly refers to the Army’s gender revolution during which the ‘joint service’ order had been introduced: an achievement which the organizations, producers of the videos, have vowed to invalidate, and indeed some of the videos are part of a campaign aimed at disseminating a message that joint service undermines the IDF and its fitness. In fact, the leaders of the religious-Zionist community were the first to fight against the joint service order and to minimize it (Yefet and Almog 2016). Similarly to the videos ‘The integration of women fighters—essential facts’ and ‘Noa volunteers to become a fighter’, this video also refrains from presenting the issues as pertaining exclusively to the religious-nationalist community, attempting instead to present them as a general risk to the IDF itself. Within the corpus of videos created as part of the struggle against recruitment of women from the religious-nationalist community, this argument serves to reinforce the counter-scripts which the organizations creating the videos aim to promote.

Figure 7.

‘A folk tale’ (Brothers at Arms, April 2017). [Hebrew wording on the slide, top to bottom, right to left: “22% are injured”; |rate of injuries are double comparted to male soldiers”; “high rates of uterine prolapse, pelvic organ prolapse and fertility issues compared to the general female population”] (Supplementary Materials).

The ‘Folk tale’ video includes two parts. The first tells of a faraway Kingdome were the consultant on equality matters meddled in the army’s functional division of roles, and weakened it; the second part reminds the viewer that ‘this is a folk tale that might be relevant to the IDF after all’, by describing the destructiveness of the Gender Affairs Advisor to the Chief of Staff ("Yohalam”)—the unit responsible for gender equality in the IDF, which according to the producers of the video operates as ‘a tool for promoting a radical feminist agenda, even at the price of undermining operational fitness’. While the first part presents the story through fictional characters that seem taken from a fantasy fable of nights in shining armor, the second part visually relies on an infographic of scientific data: figures, tables, and percentages. Both parts of the video make the allegation that the joint service—which implements the gender mainstreaming idea (Joachim and Schneiker 2012), weakens the IDF, causing it to ‘lower its standards’ so as to blur the clear characteristic differences between women and men. In parallel, the video also alleges that gender equality in the army—meaning combat service for women—causes women irreparable physical harm.

In these arguments, as well as the visual means by which they are presented, we can see the intertextuality that exists between the videos included in the corpus, despite the fact that they were produced by more than one organization. For instance, one of the data tables presented in the video illustrates the argument that women serving in combat positions are diagnosed with ‘high rates of uterine prolapse, pelvic organ prolapse and fertility issues compared to the general female population’.

However, this is not the ‘main’ concern of the video, as can also be deducted from the fact that it is the only video in the corpus without a female protagonist. Hence, it does not even pretend to offer a subjective viewpoint or a female ‘focalization’ (Shohat 2005, p. 36). Hence, it appears that, of all videos, this one provides the most ‘hermetical’ hegemonic counter script (Shohat 2005, p. 72).

As such, the video underlines the argument that the enlistment of young women in the army puts them in danger by ‘falling’ into combat service. This ‘slippery slope’, as shown in the video, will necessarily lead to irreparable damage (to the nation, the army and the private bodies) which the young women will be the cause of if they decide to join the army in general, and combat positions in particular. As mentioned, this video is the spearhead of a wider campaign that reverberated such messages in a range of publicist columns, seminars, advertisements, and bumper stickers, all aiming to show that the integration of female combat soldiers in the IDF undermines the army’s operational fitness and that those young women who choose to enlist so as to contribute to national security will, in fact, only lead to its devastation.

13. Discussion

An analysis of the videos comprising the research corpus as aiming to promote counter-scripts against the enlistment of young women from Israel’s religious-nationalist community in the IDF exposes the ways in which they establish this position, both narratively and stylistically. In addition, the analysis of the videos presents an application to non-religious logics in the rhetorical composition of the online videos. Despite the fact that the organizations initiating the production of the videos aim to preserve the conservative and patriarchal order of the religious community, specifically their position, and despite the fact that in other arenas these positions were depicted through religious logics, in the videos, we discover a significant deviation from religious rhetoric, and even use of a clearly secular one. Thus, in the videos ‘A folk tale—Who wants to weaken the IDF?’, ‘The integration of women fighters—essential facts’ and ‘Noa volunteers to become a fighter’ we see a reliance on a scientific or quasi-scientific discourse, and in the videos ‘Alone in battle’, ‘Interview with declarers of religiousness’, and ‘To choose correctly’ we see a typically secular cinematic discourse. In fact, even the video ‘A tale of five declarers’ presents this same trend in its intertextual reference to Israeli secular children’s literature (‘A tale of five balloons’) and children’s television programs, which are also devoid of religious content (such as children’s TV star Yuval Hamebulbal). Such attributes of the videos can, more than anything else, point to a moral panic among conservative patriarchal circles, for fear of losing their authority. It may be possible to find an echoing between these attributers in the videos and parallel ones in actual patterns of military enlistment among female members of the religious-nationalist community.

14. Conclusions

In this paper, we used the theory of scripts and counter-scripts to illustrate what we believe may contribute to an understanding of political communication processes. In fact, this theory can be used to expose the political strategies behind what may be perceived as unsophisticated political advertising, which is difficult to classify as it does not match any single political marketing or popular culture category. Understanding the counter script penetration strategy clarifies the subtext of the matter: these are, in fact, sophisticated texts whose aim had not been to penetrate a specific brand or slogan into the discourse, or to pave the way for a specific policy or candidate, but rather to penetrate the personal mind-set of individuals, causing them to doubt the cognitive script that they hold. This understanding may lead to renewed perceptions towards a wide range of visual representations which may not have been previously classified by the research community as being part of the ‘influence industry’ (Chester and Montgomery 2018), nearly all of which can be found in new media (ibid.).

15. Thoughts for Future Research

- One future recommended study would be the direct influence of these videos on their consumers—potential female recruits and their families, and the discourse they created among then. We know that ultimately these videos were not very influential—as we have shown in this paper through statistical data, the number of female religious soldiers continued to rise. However, it would be fascinating to examine the concrete approach to these videos through ‘Reception studies’ (Schrøder 2019) that monitor the immediate discourse that followed the videos themselves. These studies may help identify the dominant reference themes that were created in response to these videos and the population groups that responded to them. For instance, whether they evoked rejection, ridicule, scorn, ambivalence, or any other type of response. Such analysis would be made possible in studies outside the category of our research, which wholly pertains to the study of political advertising principles with an emphasis on modes of approaching the public (Henneberg 2006). The study of reception, however, requires research pertaining to the category of researching the effectiveness of political and marketing campaigns (Thaler and Helmig 2013).

- It would also be interesting to examine whether similar influence tactics (such as the videos we have examined) exist in the USA and Canada and were a source of inspiration for the conservative organizations who created them. In general, the discourse we have discussed originates in what is known as ‘the new American and Canadian conservatism’ (Cass 2021), consisting of organizations who perceive the liberal elites as destructing the military and undermining its likelihood of winning the USA’s wars, in part due to the fact that the military is open to women and the LGBT community (Blain 2005). These organizations invest their efforts in battling against this reality, telling the military “to man up” (Jackson et al. 2012), and opposing the enlistment of women in combat positions by at least two methods: an attempt to prevent the enlistment of these women by approaching them directly (similarly to the tactics presented in the current paper), or by approaching young conservative women who wish to serve in the army despite their communities’ beliefs that the military should remain masculine. If such examples do in fact exist, they would be an interesting case study in order to examine whether they may have anything in common with the cases presented in the current paper.

Supplementary Materials

The following videos are available online “Alone in battle—the story of a religious [female] soldier” produced by Chotam Org. (January 2017): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EnmCIxXoPzE (accessed on 9 September 2021); Noa volunteers to become a fighter—produced by The IDF Fortitude Forum (August 2017): https://he-il.facebook.com/IDF.Fortitude.Forum/videos/%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%A2%D7%94-D7%9E%D7%AA%D7%A0%D7%93%D7%91%D7%AA-%D7%9C%D7%94%D7%99%D7%95%D7%AA%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%97%D7%9E%D7%AA/1953506678228935 (accessed on 9 September 2021); The integration of women fighters—produced by The IDF Fortitude Forum (August 2017): http://www.forum-ltz.co.il/women-warriors-facts/ (accessed on 9 September 2021); Religion-Meter—produced by Chotam Org. (April 2018): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PMNl1ZQg0Qo (accessed on 9 September 2021); To choose correctly—produced by Chotam Org. (October 2020): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zSwIg2hI-DE (accessed on 9 September 2021); A folk tale—produced by ‘Brothers at Arms’ Org. (April 2017): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6EuW9HUgGOM (accessed on 9 September 2021); A tale of five declarers—produced by Chotam Org. (January 2019): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sStI0O_euSw (accessed on 9 September 2021).

Author Contributions

Both authors have equally contributed to the paper’s Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, and writing. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Talya Alon, our Research Assistant, for contributing to the collection of publicist columns on the polemic in Zionist-religious society. We also thank Yael Nachumi for her professional editing and valuable suggestions. Many thanks to Esther Gleichman, Manager of the Library of Social Sciences at Bar Ilan University for extraordinarily professional and obliging support, even during this difficult year. Without her support our research would not have been completed and a great thank you to Poppy Wu, the journal’s Assistant Editor, for her professionality, kindness, and endless dedication for the excellence of this article. Working with you Poppy was a refreshing experience in the world of academic journals’ industry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamker, Yaki. 2013. Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu: Military service is unsuitable for a daughter of Israel. Walla News, December 16. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawi, Ahmed. 2015. Online Reactions to the Muhammad Cartoons: YouTube and the Virtual Ummah. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artzi-Sror, Chen. 2017. Eshet Chayil Mi Tikra. Yedioth Ahronoth, September 7. [Google Scholar]

- Avgar, Ido. 2017. Data on Recruitment of Religious Women to the IDF. Jerusalem: Knesset Research and Information Center. [Google Scholar]

- Aviner, Rabbi Shlomo. 2015. A girl enlisting in the IDF contributes to the destruction of the State. Knitted News, November 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barak-Erez, Daphne. 2007. On Women Pilots and Conscientious objection to military service: A single struggle or separate ones? In Studies in Law, Gender and Feminism. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, pp. 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Desmond. 2011. Documentary Film and the Poetics of History. Journal of Media Practice 12: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Asher, Smadar, and Yaarit Bokek-Cohen ’. 2019. Negative Symbolic Capital and Politicized Military Widowhood. Journal of Political & Military Sociology 46: 301–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Asher, Smadar, and Udi Lebel. 2010. Social Structure Vs. Self-Rehabilitation: IDF Widows Forming an Intimate Relationship in the Sociopolitical Discourse. Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology 1: 39–60. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12424/1579686 (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Berne, Eric. 1961. Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy: A Systematic Individual and Social Psychiatry. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berne, Eric. 1972. What Do You Say after You Say Hello?: The Psychology of Human Destiny. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bick, Etta. 2016. Institutional layering, displacement, and policy change: The evolution of civic service in Israel. Public Policy and Administration 31: 342–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, Michael. 2005. The Politics of Victimage: Power and subjection in a US anti-gay campaign. Critical Discourse Studies 2: 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budaie-Hyman, Ranit. 2016. Religion-Gender-Military: Feminine Identities: Between Religion and Military in Israel. Ph.D. dissertation, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, Paula J. 2000. The New Don’t Blame Mother. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, Oren. 2012. A New Conservatism. Foreign Affairs 100: 116–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chester, Jeff, and Kathryn C. Montgomery. 2018. The Influence Industry: Contemporary Digital Politics in the United States. Tactical Technology. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.io/s/ourdataourselves.tacticaltech.org/ttc-influence-industry-usa.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Chin, Elaine. 1994. Redefining “Context” in Research on Writing. Written Communication 11: 445–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Justin T. 2014. Examining the Life Script of African-Americans: A Test of the Cultural Life Script. Applied Cognitive Psychology 28: 419–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, Yechezkel, and Shaul Kimhi. 2000. Military service and self-perceived maturation among Israeli youth. Megamot 40: 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cillia, Rudolf, Martin Reisigl, and Ruth Wodak. 1999. The discursive construction of national identities. Discourse and Society 10: 149–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneulin, Severine. 2022. Religion and Development. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Development. Edited by Matthew Clarke. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Doane, Mary Ann. 2002. The "Woman’s Film": Possession and Address. In Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and Woman’s Film. Edited by Christine Gledhill. London: BFI Publishing, pp. 238–98. [Google Scholar]

- Elmezeny, Ahmed, Nina Edenhofer, and Jeffrey Wimmer. 2018. Immersive Storytelling in 360-Degree Videos: An Analysis of Interplay between Narrative and Technical Immersion. Journal of Virtual World Research 11: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlich, Yifat. 2016. Halachic ruling is important to me but apparently not enough. This would not prevent me from realizing my dream of flying. Yedioth Ahronoth, October 13. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, Richard G. 2009. Life Scripts and Attachment Patterns: Theoretical Integration and Therapeutic Involvement. Transactional Analysis Journal 39: 207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, Yair. 2015. The Number of religious women enlisting in the IDF doubled since 2010. Haaretz, May 6. [Google Scholar]

- Farah Bidjari, Azam. 2011. Attitude and Social Representation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 30: 1593–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, Jennifer R., and Laura Mamo. 2002. What’s in a Disorder. Women and Therapy 24: 179–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, Stephanie. 2008. Feminist Coalitions: Historical Perspectives on Second Wave Feminism in the United States. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, Kris, Betsy Rymes, and Joanne Larson. 1995. Script, Counterscript, and Underlife in the classroom: James Brown versus Brown v. Board of Education. Harvard Educational Review 65: 445–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hains, Rebecca C. 2009. Power Feminism, Mediated: Girl Power and the Commercial Politics of Change. Women’s Studies in Communication 32: 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanitzch, Thomas, and Tim P. Vos. 2017. Journalistic Rules and the Struggle over Institutional Identity: The Discursive Constitution of Journalism. Communication Theory 27: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harre, Rom. 1998. The Singular Self. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Henneberg, Stephan C. M. 2006. Leading or Following? A Theoretical Analysis of Political Marketing Postures. Journal of Political Marketing 5: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. 1998. Homefront and Battlefront: The Status of Jewish and Palestinian Women in Israel. Israel Studies 3: 61–84. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30246796 (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Hollander, Y. 2017. Innovation in the books of Jewish religious literature: A guidebook to the female religious recruit. Makor Rishon, August 25. [Google Scholar]

- Horno-Lopez, Antonio. 2015. The Particular Visual Language of Anime: Design, Color and Selection of Resources. Animation Practice, Process & Production 5: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunting, Kyra. 2021. Critical content analysis: A methodological proposal for the incorporation of numerical data into critical/cultural media studies. Annals of the International Communication Association 45: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husband, Charles. 2007. Social Work in an Ethnically Diverse Europe. Social Work and Society 5. Available online: http://www.socwork.net/2007/festschrift/esp/husband (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Ingram, Robert. 1985. Transactional Script Theory Applied to the Pathological Gambler. Journal of Gambling Behavior 1: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Joshua J., Felix Thoemmes, Kathrin Jonkmann, Oliver Lüdtke, and Ulrich Trautwein. 2012. Military Training and Personality Trait Development: Does the Military Make the Man, or Does the Man Make the Military? Psychological Science 23: 270–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, Jutta, and Andrea Schneiker. 2012. Changing discourses, changing practices? Gender mainstreaming and security. Comparative European Politics 10: 528–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Gila. 2007. Tzahali and Roni. Religious Kibbutz Organization Website. Available online: http://www.kdati.org.il/cgi-webaxy/sal/sal.pl?lang=he&ID=812319_kdati&act=show&dbid=pages&dataid=pages_891040_kdati_info_amudim_5767_715_09.htm (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Kemp, Martin. 2010. Style and Non-Style in Anatomical Illustration: From Renaissance Humanism to Henry Gray. Journal of Anatomy 216: 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, Annette. 1992. Women’s Genres. In The Sexual Subject—A Screen Reader in Sexuality. Edited by Mandy Merck. London: Routledge, pp. 301–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, Udi. 2014. ‘Blackmailing the army’—’Strategic Military Refusal’ as policy and doctrine enforcement: The formation of a new security agent. Small Wars & Insurgencies 25: 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, Udi. 2015. Settling the Military: The Pre-military Academies Revolution and the Creation of a New Security Epistemic Community—The Militarization of Judea and Samaria. Israel Affairs 21: 361–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, Udi. 2016. The ‘Immunized Integration’ of Religious-Zionists within Israeli Society. Social Identities 22: 642–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, Udi, and Guy Hatuka. 2016. De-militarization as political self-marginalization: Israeli Labor Party and the MISEs (members of Israeli security elite) 1977–2015. Israel Affairs 22: 641–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, Brooklyn. 2020. The Colonial/Modern [Cis]Gender System and Trans World Traveling. Hypatia 35: 454–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, Emanuela, and Alba Alonso. 2020. Gender Regime Change in Decentralized States: The Case of Spain. Social Politics 27: 449–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, Orly, and Yuval Worgen. 2017. IDF Service of Religious Women. Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Lyle. 2017. Against the ‘Statue Anatomized’: The Art of Eighteenth-Century Anatomy on Trial. Art History 40: 68–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauksch, Stefanie. 2017. Managing the dance of Enchantment. Organization 24: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Iver B. 2005. To Be a Diplomat. International Studies Perspectives 6: 72–93. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44218353 (accessed on 9 September 2021). [CrossRef]