Japan’s Sacred Sumo and the Exclusion of Women: The Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler (Part 1)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. An Olympic-Sized “Gender Problem”

3. “Women Please Come Down from the Ring”

“Women please come down from the ring!” (Josei no kata wa dohyō kara orite kudasai)“Women please come down from the ring!”“Women please come down from the ring, men please enter the ring! (Josei no kata wa dohyō kara orite kudasai, dansei ga oagarikudasai)

4. Victory to the Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler

The two men stood opposite to one another. Each raised his foot and kicked at the other, when Nomi no Sukune broke with a kick the ribs of Kehaya and also kicked and broke his loins and thus killed him. Therefore the land of Taima no Kehaya was seized, and was all given to Nomi no Sukune.

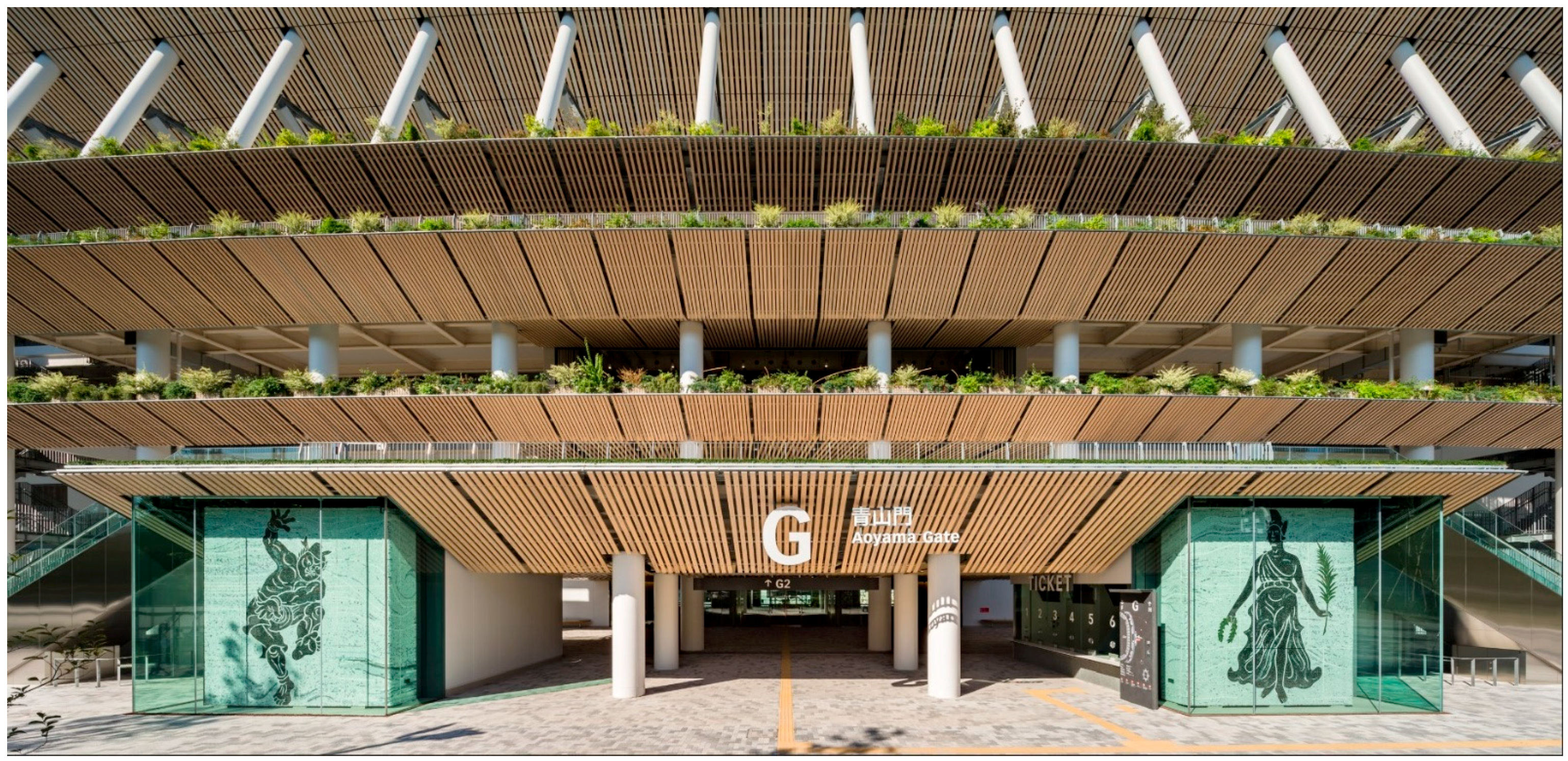

On the right side of the tower is a four-meter-tall standing image of a Greek goddess. She carries the meaning of glory and holds a Canarium album (sometimes translated as olive but of a different type) and a laurel wreath. It is a “symbol of beauty.”On the left is a “symbol of power” with Nomi no Sukune, the founder of sumo, called the national sport. It is the same size as the statue on the right.The black and white mosaic is expressed in a straightforward manner, and the white part is mixed with light colored glass to clarify the nuances of each.

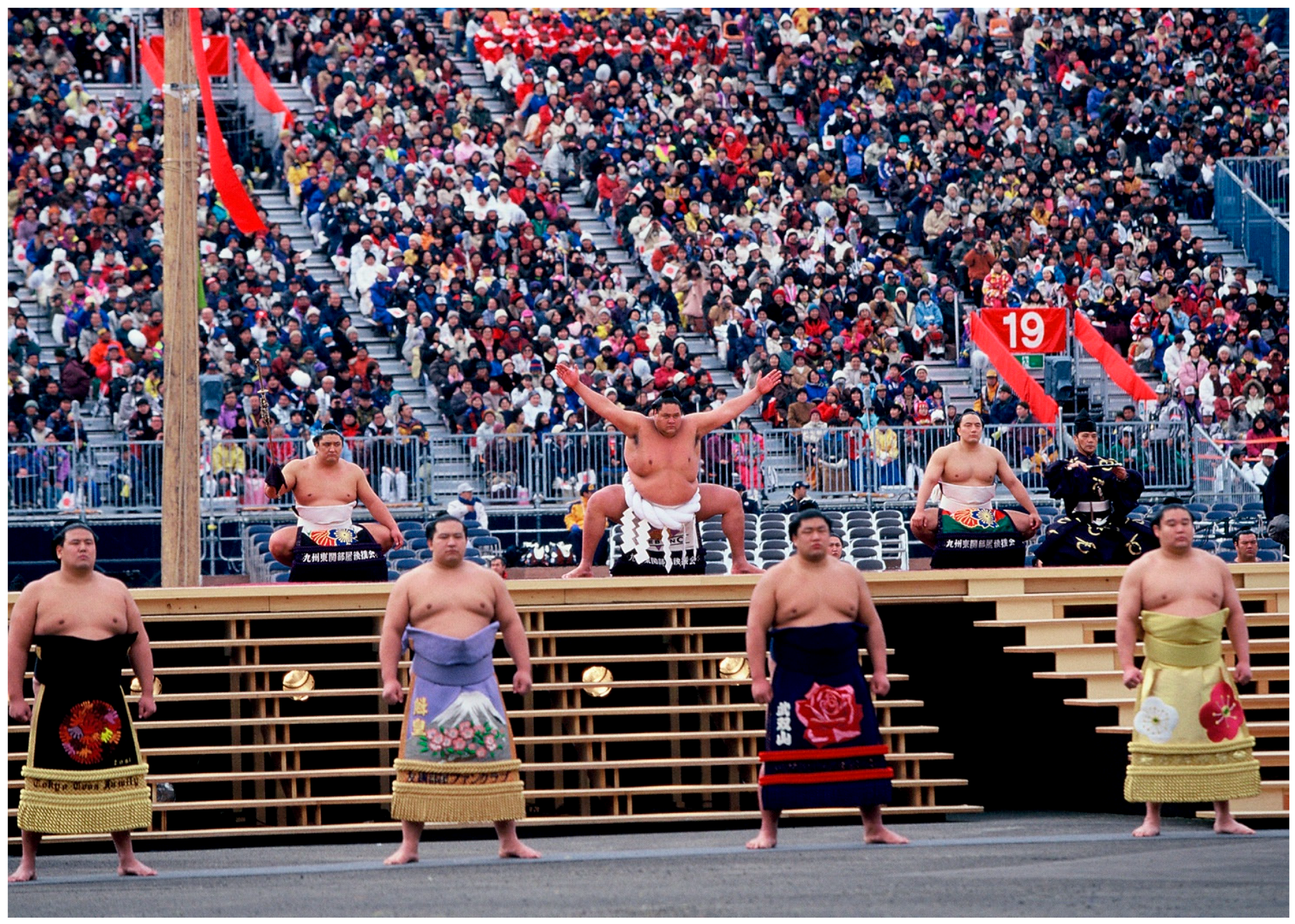

5. Setting the Olympic Stage in Nagano

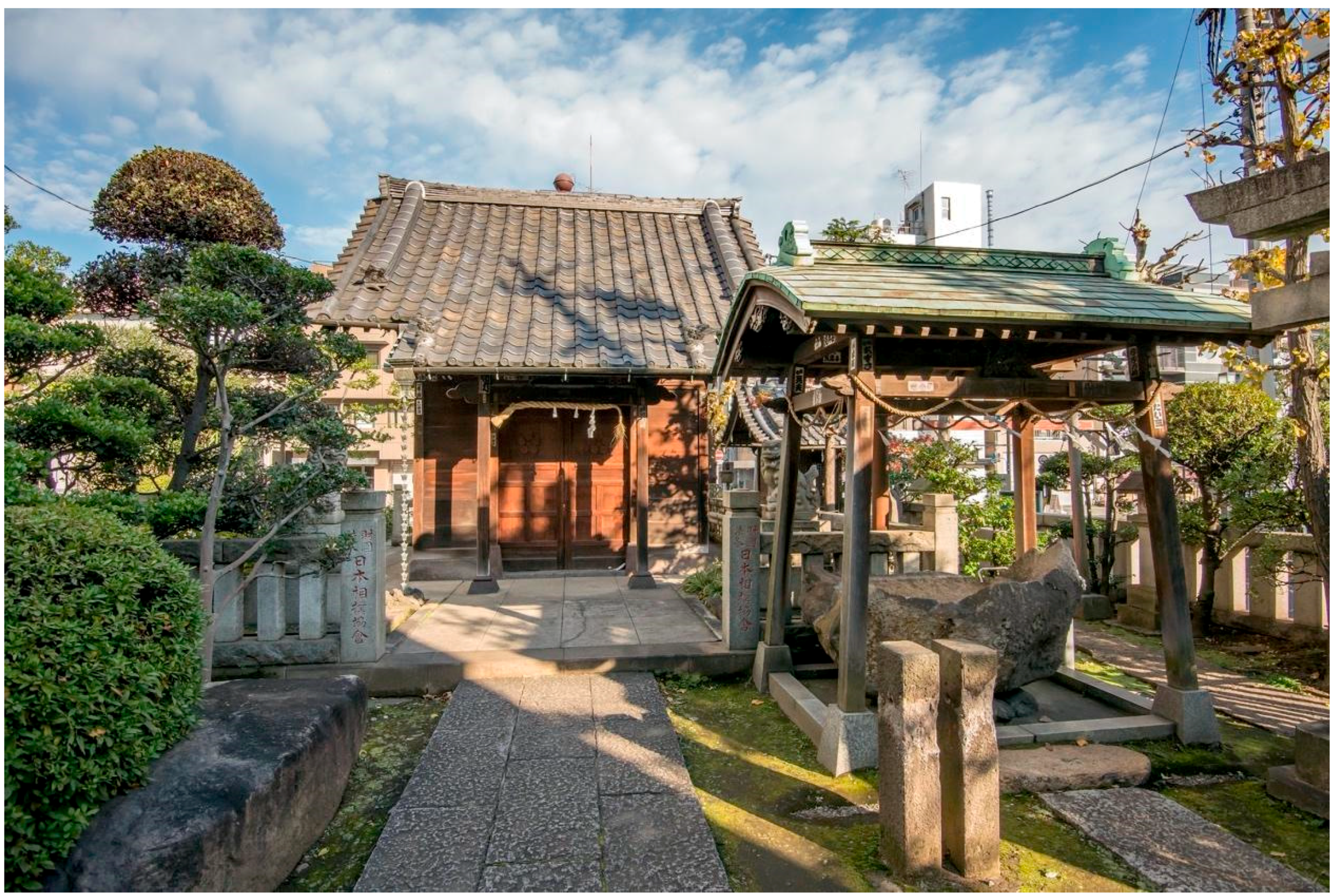

6. Enshrining the Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler

Sumo’s mythical origins first appear in the “land-ceding” tales [of the Kojiki] at the time of the heavenly ancestors’ descent, and they reappear in the national history in the context of a sumo match viewed by the ruler. Local people have long regarded these grounds as the historic ruins of “Ketayakeshi” (lit., “extinguishing” [keshi] on the “ring” [kataya]), where the sovereign ruler (tennō) beheld a sumo match, thus we erect here a modest and pleasing shrine. Far from a simple combat technique, sumo, the national sport, constitutes a kami ritual … a sacred affair performed in an agrarian nation to quell evil spirits. Successive generations of national histories, beginning with the Nihon shoki, clearly articulate sumo’s origins and purpose as such.

7. Entering the Ring

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Sumo Wrestler Plays All the Sports in France TV’s Tokyo Olympics Spot,” The Daily Brief, Promax, May 21, 2021, https://brief.promax.org/article/sumo-wrestler-plays-all-the-sports-in-france-tvs-tokyo-olympics-spot (accessed on 28 August 2021). |

| 2 | “Orinpikku e no torikumi: Ōzumō Tōkyō 2020 Orinpikku Pararinpikku basho,” Nihon Sumō Kyōkai, https://www.sumo.or.jp/Efforts/olympic/ (accessed 20 May 2021). |

| 3 | The Japan Sumo Federation (JSAF; Kōeki Zaidanhōjin Nihon Sumō Renmei, est. 1946), aiming to make sumo an official sport of the Olympics, established an affiliate federation in 1996, the Osaka-based New Sumo League (Shin Sumō Remmei), to develop and promote women’s sumo. The JSAF apparently selected the word “new” in the title, rather than “women’s” or “girls’” in order to skirt the negative image associated with the mixed-gender wrestling shows of the Edo period (Ikkai 2010). The organization was renamed as Japan Women’s Sumo Federation (Nihon Joshi Sumō Renmei) in 2007. In 1997, Japan hosted its first national competition for women, and the inaugural international women’s competition took place in Germany in 1999. On contemporary women’s sumo (see Pauly 2008; Shimokawa et al. 1999, esp. pp. 82–88; Ikkai 2010; Gilbert and Watts 2014, esp. pp. 171–73). On the successful refashioning of judo, another male-dominated Japanese sport, as an Olympic discipline in 1964, see Niehaus (2006). |

| 4 | The term sumo designates a rich variety of stylized wrestling forms with a provenance that extends over several millennia and spans multiple continents. Professional sumo refers specifically to the Japanese sport organized and managed by the Japan Sumo Association, since 2014 a Public Interest Incorporated Juridical Person (Kōeki Zaidan Hōjin) operating under the nominal supervision of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Monbukagakushō, or MEXT). |

| 5 | Stage names and name changes are standard in professional sumo. Most professional wrestlers adopt ring names imbued with mythical symbolism (shikona) as they rise through the ranks. High-ranking wrestlers who become Sumo Association elders (toshiyori) after retirement typically assume the name associated with the “stock” they acquire or inherit. Elders hold equal shares of the organization (105 in total), which function like stock holdings. These men control all facets of the profitmaking Japanese sport. On the complex and secretive elder system, see West (1997, 2005). |

| 6 | Yokozuna (lit., “horizontal rope”) refers to the highest rank in professional sumo and takes its name from the white woven rope that adorns the waist of a grand champion wrestler. Modeled on hemp ropes or twisted rice straws used for ritual purification at shrines (shimenawa), the rope functions to visually distinguish the wrestler as a sacred being. On the late-nineteenth-century invention of the yokozuna system, see Thompson (1998). |

| 7 | “Kyōkai kara no oshirase: Rijichō danwa,” Nihon Sumō Kyōkai, http://www.sumo.or.jp/IrohaKyokaiInformation/detail?id=268 (accessed 20 May 2021). |

| 8 | A Google Scholar search reveals thousands of instances of the phrase “gender problem.” In the Japanese context, the phrase appears in, e.g., Hara 2004; and Asahi shinbun 2021b. |

| 9 | Apologies in Japan are often given as a prerequisite for avoiding formal penalty. Gender conservatives rallied to Mori’s defense. Takasu Katsuya, for instance, a cosmetic surgeon known for his public denial of military sexual slavery in the Japanese colonies Imperial Japan and of the Nanjing Massacre, expressed sympathy for the aged Mori on Twitter and reminded his followers that the Olympics were originally prohibited to women (Riaru Raibu 2021). |

| 10 | In addition to six official sumo tournaments (honbasho), the Sumo Association organizes provincial tours (jungyō) each season which fan out all across the Japanese archipelago. |

| 11 | The two women who took action, later identified as nurses, chose to remain anonymous. Independently, (Mr.) Dr. Ōfusa Yukihiro of the Japanese Society of Emergency Medicine and Director of Anesthesiology Department, Showa Inan General Hospital, a CPR expert, chose to analyze videos of the incident and evaluated the action of the women as a “perfect” first response (Kinkōzan 2018). |

| 12 | The most popular videos of the incident have for reasons unknown been removed from YouTube. At the time of writing (July 2021), the following link remained active: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpAMLJBfP8g&ab_channel=Throlouldabc (accessed on 28 August 2021). |

| 13 | A video of the speech can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GW_YZOwlOI8 (accessed on 28 August 2021). For a transcript of Nakagawa’s speech, see Mainichi shinbun (2018a). |

| 14 | “I spoke out on behalf of my fellow mayor friends,” he later reflected (Nikkan Sports 2018a). Not all male mayors showed the same courtesy, however. When the tour appeared in Kakegawa City, Shizuoka prefecture on April 9, Mayor Matsui Saburo opened his speech by stating, “I’m very grateful to be permitted to stand in the ring … I’ll do my best not to collapse, but if I do there are male doctors nearby.” In response to charges that his statement was inappropriate, the mayor claimed that he had been “really nervous” but that he had “no awareness whatsoever” about what happened in Maizuru (Sankei shinbun 2018). |

| 15 | The design, created by Greek artist Elena Votsi for the 2004 Athens Games, drew inspiration from the famous marble statue carved by Paionios in the fifth century BC and offered as a war trophy to Zeus, the supreme deity of Mount Olympus (Fasel 2016). |

| 16 | “Tokyo 2020 Olympic Medal Design,” The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, 2020, https://olympics.com/tokyo-2020/en/games/olympics-medals-design/ (accessed on 20 May 2021). |

| 17 | On the exclusion of women from the ancient Olympic Games, see Patay-Horváth (2017), Mouratidis (1984). Patay-Horváth urges us to think of the strict male-only rule at Olympia as a vestige of hunting cults there dedicated to the goddess Artemis that predated the cult of Zeus and the Olympic Games. He bases this provocative speculation on evidence from the Artemis cult site at Ephesia, and from global research on the rituals and taboos of hunting cultures, especially those related to the avoidance of menstrual blood and sexual intercourse as necessary conditions for successful hunts. Lore of jealous female deities whose proper supplication entails the complete avoidance of women circulates in the Japanese archipelago as well, especially associated with mountainous hunting cultures, and proponents of sumo’s female taboo frequently cite that lore. Mouratidis, in contrast, traces the female taboo to the figure of Herakles, the hero-athlete turned divinity around whom worship cults developed prior to the introduction of Zeus at Olympia. Mouratidis additionally implicates pre-Hellenic cults to the goddess Artemis, pointing out that the only real woman permitted to observe the games was the priestess of Demeter Chamy who, according to the author, assumed Artemis’s primary functions as a fertility and vegetation goddess. We learn from Mouratidis that earlier scholars interpreted the gender ban as an effort to protect warriors and heroes from having their energy diminished by the distracting powers of women (Gardiner [1910] 2016; Farnell [1921] 2017). The parallels between the Greek and Japanese exclusionary logics and their prominent tropes will be revisited in more depth in a separate publication. |

| 18 | Paionios’ Nike, a marble statue rising more than two meters tall, was situated thirty meters to the east of the Temple of Zeus façade, erected atop an eight-and-a-half-meter tall marble pillar. Art historians typically date the statue to ca. 420 BC (Barringer 2015, p. 32). |

| 19 | “Kokuritsu kyōgijō kinen medaru jun kinmedaru (Dai),” Japan National Stadium, https://kokuritsu-official-store.com/items/60efe3e1053624633ec45829 (accessed 7 September 2021). The large-size medallion carries a price tag of 1,089,000 yen (more than 8000 euros). |

| 20 | Hasegawa, a celebrated Japanese artist and fashion historian known for his religious paintings of Christian themes (Hasegawa was Catholic), is attributed with formally introducing fresco and mosaic techniques to Japan. While honing his artistic skills in Europe, Hasegawa copied Buddhist mural fragments collected by the Berlin expeditions to Central Asia, in particular murals from the Kizil caves along the Silk Road. (National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo 2019; SANPAOLO and Mizuno 2017). |

| 21 | Bolitho (1988, pp. 17–18); adapted from (Aston [1896] 1972, p. 173). The full text of the Shoki shūge (30 vols.) version of the Nihon shoki, written by Kawamura Hidene and printed by Ritsuanzō in 1785, accompanied by Aston’s English translation, can be found online at https://jhti.berkeley.edu (accessed on 28 August 2021) courtesy of the University of California at Berkeley’s Japanese Historical Text Initiative. |

| 22 | Sumo Association Chairman Tokitsukaze (the former yokozuna Futabayama), director Hidenoyama (the former upper-division wrestler Takagiyama), and two members of the Yokozuna Deliberation Council (Yokozuna Shingi Iinkai), right-wing figures Miura Giichi and Ozaki Shiro. The Yokozuna Deliberation Council, established in 1950, is a group of roughly ten high-profile laypeople with an understanding of sumo (e.g., writers, celebrities, academics) who independently advise the Sumo Association on the promotion and retirement of yokozuna. |

References

- Akanuma, Nanao. 2010. Stepping Outside the Ring: An Ethnography of Intimate Associations in Japanese Professional Sumo. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Asahi shinbun. 2018. Dohyō ni tairyō no shio maku joseira ga taoreta shichō kyūmeigo Maizuru. April 5. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASL453VCJL45PLZB006.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Asahi shinbun. 2021a. ‘Josei ga takusan haitte iru kaigi wa jikan kakaru’ Mori Yoshirō-shi. February 2. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASP235VY8P23UTQP011.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Asahi shinbun. 2021b. (ThinkGender) jendā mondai, bunka jinruigaku no shiten kara. March 2. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/articles/DA3S14817616.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Aston, William George. 1972. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest times to 697 A.D. Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing. First published 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Barringer, Judith. 2015. The Changing Image of Zeus in Olympia. Archäologischer Anzeiger 1: 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bēsubōru Magajinsha. 2017. Ōzumō meimon retsuden shirīzu (3): Takasagobeya. Tokyo: Bēsubōru Magajinsha. [Google Scholar]

- Bogel, Cynthea J. 2020. Un cosmoscape sous le Bouddha: le piédestal de l’icône principale de Yakushi-ji, soutien de l’empire des souverains. Perspective: Actualité en histoire de l’art 1: 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolitho, Harold. 1988. Sumo and Popular Culture: The Tokugawa Period. In The Japanese Trajectory: Modernization and Beyond. Edited by Gavan McCormack and Yoshio Sugimoto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2001. Masculine Domination. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- BuzzFeed Japan. 2018. Ōzumō no nyonin kinsei o kaigai media wa dō hōjita ka. April 6. Available online: https://www.buzzfeed.com/jp/eimiyamamitsu/dohyo-sumo (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Translated and Edited by David A. Campbell. 1991, Greek Lyric III: Stesichorus, Ibycus, Simonides, and Others. (Loeb Classical Library, 476). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, Lucas. 2013. Combat Sports Professionalism in Medieval China (220–960 AD). In Nikephoros—Zeitschrift für Sport und Kultur im Altertum: 26. Edited by Paul Christesen, Wolfgang Decker, James G. Howie, Christian Mann, Peter Mauritsch, Zinon Papakonstantinou, Robert Rollinger and Ingomar Weiler. Hildesheim: Weidmannsche Verlasbuchhandlung GmbH, pp. 227–52. [Google Scholar]

- Como, Michael. 2009. Weaving and Binding: Immigrant Gods and Female Immortals in Ancient Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, Lindsey E. 2015. A Mountain Set Apart: Female Exclusion, Buddhism, and Tradition at Modern Ōminesan, Japan. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, Lindsey E. 2016. Envisioning and Observing Women’s Exclusion from Sacred Mountains in Japan. Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University (JAH-Q) 1: 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, Lindsey E. 2018. Island of Many Names, Island of No Name: Taboo and the Mysteries of Okinoshima. In The Sea and the Sacred in Japan: Aspects of Maritime Religion. Edited by Fabio Rambelli. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, Lindsey E. 2020. World Heritage and Women’s Exclusion. In Sacred Heritage in Japan. Edited by Aike P. Rots and Mark Teeuwen. London: Routledge, pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dinnie, Keith. 2008. Nation Branding: Concepts, Issues, Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, Jesse. 2016. The Survival of Winged Victory in Christian Late Antiquity. Discentes 1: 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Duthie, Torquil. 2014. Man’yōshū and the Imperial Imagination in Early Japan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Farnell, Lewis Richard. 2017. Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality: The Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of St. Andrews in the Year 1920. Coronado: Andesite Press. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Fasel, Marion. 2016. Elena Votsi Designed The Olympic Medal. The Adventurine. Available online: https://theadventurine.com/culture/jewelry-history/elena-votsis-story-about-designing-the-olympic-medal-is-pure-gold/ (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Faure, Bernard. 2003. The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 2015. Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/doi/book/10.21313/9780824857721 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- FNN. 2018a. ‘Onnanoko wa sabishisōdatta’ Chibikko Sumō demo ‘nyonin kinsei.’ Transcript of April 12 broadcast of program “Chokugeki LIVE guddi!” [GOODY! GOOD DAY!]. Available online: https://www.fnn.jp/articles/-/3473 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- FNN. 2018b. Sumōkai no ‘nyonin kinsei’ wa dentō ka sabetsu ka…kaigai demo hōdō. April 9. Available online: https://www.fnn.jp/articles/-/22531 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Gardiner, E. Norman. 2016. Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals (Classic Reprint). Charleston: Forgotten Books. First published 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Howard, and Katrina Watts. 2014. Internationalizing Sumo: From Viewing to Doing Japan’s National Sport. In Internationalising Japan: Discourse and Practice. Edited by Jeremy Breaden, Stacey Steele and Carolyn S. Stevens. London: Routledge, pp. 158–79. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Xavier. 2018. Japanese Women Attempting to Save Man’s Life after Suffering Stroke in Sumo Ring Ordered to Leave for Being ‘Ritually Unclean’. The Independent. April 5. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/japan-sumo-wrestling-man-stroke-women-ritually-unclean-maizuru-ryozo-tatami-a8290236.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Guajardo, Maria. 2016. Tokyo 2020 Olympics: Nation Branding Creates an Opportunity for a New Cultural Narrative for Japan. In The IAFOR International Conference on Japan & Japan Studies 2016: Official Conference Proceedings, June 2–5. Kobe: The International Academic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, Keiko. 2021. Nihon no jendā gyappu shisū 120-i no haigo ni iru ‘seki o akenai’ danseitachi. Tokyo: Kōdansha, April 4, Available online: https://gendai.ismedia.jp/articles/-/81861 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Hara, Hiroko. 2004. Jendā mondai to gakujutsu kenkyū. Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, Akira. 1993. Sumō no tanjō. Tokyo: Shinchōsha. [Google Scholar]

- HuffPost Japan. 2018. ‘Chibikko Sumō’ demo kinshi; Onna no ko wa dohyō ni agaranai yō ni Sumō Kyōkai ga yōsei. April 8. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.jp/2018/04/12/sumogirl_a_23409239 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History. 2007. ‘Tatsuno’ no hajimari: Sumō no kamisama, Nomi no Sukune. Hyōgo densetsu kikō 2: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ikkai, Chie. 2010. Sumō to josei no igaina kankei. In Shiru supōtsu kotohajime. Edited by Ishii Takanori and Tasato Chiyo. Dai 1-bu supōtsu to shakai, Chapter 6 (no pages available for online version). Tokyo: Meiwa Shuppan, Available online: http://home.att.ne.jp/kiwi/meiwa/sport07.htm (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Inoue, Makiko, Motoko Rich, and Tiffany May. 2021. Tokyo Olympics Official Resigns After Calling Plus-Size Celebrity ‘Olympig’. The New York Times. March 18. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/18/world/asia/tokyo-olympics-hiroshi-sasaki.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- International Olympic Committee. 2021. IOC Statement on gender equality in the Olympic Movement. February 9. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/ioc-statement-on-gender-equality-in-the-olympic-movement (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Katsuura, Noriko. 2009. Women and Views of Pollution. Acta Asiatica 97: 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kida, Takuya. 2013. Tōkyō Orinpikku 1964 sono dezainwāku ni okeru ‘Nihon-tekina mono’. In Tōkyō Orinpikku 1964 Dezain Purojekuto [Design Project for the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games]. Edited by Tōkyō Kokuritsu Kindai Bijutsukan [The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo]. Tokyo: Tōkyō Kokuritsu Kindai Bijutsukan, pp. 8–14. Available online: http://design-cu.jp/iasdr2013/papers/1757-1b.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Kinkōzan, Masako. 2018. Dohyō de kyūmei ni atatta josei no shoki taiō, ishi ga zessan ‘sōtō torēningu o tsunda kata to omowaremasu’. HuffPost Japan. April 5. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.jp/2018/04/05/rescue-doctor_a_23404339 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Kobayashi, Naoko. 2017. Sacred Mountains and Women in Japan: Fighting a Romanticized Image of Female Ascetic Practitioners. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 44: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyodo News. 2018. Sumo: Female Mayor Barred from Giving Speech on Sumo Ring in Wake of Furor. April 6. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2018/04/c39e66ddcedf-female-mayor-barred-from-giving-speech-in-sumo-ring-in-wake-of-furor.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Mainichi shinbun. 2018a. Haru jungyō Takarazuka basho; Shichō ‘Dohyōjō de aisatsu dekinai, kuyashī.’ Gunma local edition. April 7. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/articles/20180407/ddl/k28/050/368000c (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Mainichi shinbun. 2018b. Josei dohyō mondai: Josei shichō, dohyōka kara chūmon Takarazuka jungyō ‘Sumō Kyōkai wa henkaku no yūki o.’ Morning edition. April 7. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/articles/20180407/ddm/041/050/069000c (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Mainichi shinbun. 2021. Gorin soshikii shinkaichō; Hashimoto an; yoron mikiwame; sekuhara hihan, genteiteki. February 19. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/articles/20210219/ddm/003/050/038000c (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- MIKIKO. 2021. Ichiren no hōdō ni kanshimashite. March 26. Available online: https://elevenplay.net/mikiko_comment_20210326.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Minamoto, Junko. 2020. Itsu made tsuzuku “Nyonin kinsei”: Haijo to sabetsu no Nihon shakai o tadoru. Osaka: Kaihō shuppansha. [Google Scholar]

- Mori Kaichō No Shogū No Kentō O Motomeru Yūshi. 2021. Please address Chairman Mori’s remark and take measures to not tolerate such behaviors. Online petition. Available online: https://www.change.org/p/we-request-that-chairman-mori-s-recent-behavior-are-properly-addressed-and-steps-taken-to-ensure-that-similar-behavior-will-not-be-tolerated-in-the-future (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Mouratidis, John. 1984. Heracles at Olympia and the Exclusion of Women from the Ancient Olympic Games. Journal of Sport History 11: 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, Tomoko. 2020. Naze dohyō no ue de aisatsu dekinainoka: Takarazuka shichō no kēsu. Interview. In Itsu made tsuzuku "Nyonin kinsei": Haijo to sabetsu no Nihon shakai o tadoru. Edited by Minamoto Junko. Osaka: Kaihō shuppansha, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- NAOC. 1998. [Organizing Committee for the XVIII Olympic Winter Games, Nagano 1998]. The XVIII Olympic Winter Games, Nagano 1998: The Opening Ceremony Media Guide. Tokyo: NAOC. [Google Scholar]

- Nara shinbun. 2013. ‘Kaettekita’ Nomi no Sukune. July 8. Available online: https://www.nara-np.co.jp/news/20130708101925.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo. 2019. Hasegawa Roka: Nihon bijutsu nenkan shosai mokkosha kiji; Tokyo: Tōkyō Bunkazai Kenkyūjo. Available online: https://www.tobunken.go.jp/materials/bukko/9099.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Niehaus, Andrea. 2006. ‘If you want to cry, cry on the green mats of Kōdōkan’: Expressions of Japanese cultural and national identity in the movement to include judo into the Olympic programme. International Journal of the History of Sport 23: 1173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihon Supōtsu Shinkō Sentā [Japan Sport Council]. n.d. Kokuritsukyōgijō kinen sakuhintō no saishū hozon basho ni tsuite; Sankō 5. Tokyo: Nihon Supōtsu Shinkō Sentā. Available online: https://www.jpnsport.go.jp/newstadium/Portals/0/kinennhinnhozonn/itiran.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Nikkan Sports. 2018a. Shizuoka shichō ga dohyōjō de kaikaku uttae ‘21 seikichū ni kaete’. April 8. Available online: https://www.nikkansports.com/battle/sumo/news/201804080000547.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Nikkan Sports. 2018b. Bei NY Taimuzu nado dohyō mondai o ‘sabetsuteki kanshū’ to hōdō. April 7. Available online: https://www.nikkansports.com/battle/sumo/news/201804070000128.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Nitta, Ichirō. 1994. Sumō no rekishi. Tokyo: Yamakawa shuppansha. [Google Scholar]

- Ōkubo, Naoki, Suzuki Kensuke, and Takezono Takahiro. 2018. Dohyō ni josei, gyōji ‘Atama no naka de fukuranda’ nyonin kinsei no rekishi. Asahi shinbun. April 5. Available online: https://digital.asahi.com/articles/ASL456G6ML45UTQP021.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Park, Ju-min, and Akiko Okamoto. 2021. Don’t be silent: How a 22-year-old woman helped bring down the Tokyo Olympics chief. Reuters Tokyo. February 18. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-olympics-2020-women-idUSKBN2AI0ZF (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Patay-Horváth, András. 2017. Why were Adult Women Excluded from the Olympic Games? Arys 15: 133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, Ulrich. 2008. Die Nonne im Ring: Eine kurze Geschichte des Frauen-Sumō. Tokyo: OAG NOTIZEN, Tokyo: German Society for Nature and Ethnology of East Asia (OAG), pp. 10–25. Available online: https://oag.jp/img/images/publications/oag_notizen/Notizen_0804_Feature_Pauly.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Philippi, Donald. 1968. Kojiki. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, Available online: https://archive.org/details/kojikitranslated00phil/page/132/mode/2up?q=sumo (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Plugh, Michael. 2018. Born Again Yokozuna: Sports Media and National Identity. In Routledge Handbook of Japanese Media. Edited by Fabienne Darling-Wolf. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, Ltd., pp. 101–20. [Google Scholar]

- Polley, Martin. 2014. Sport, Gender and Sexuality at the 1908 London Olympic Games. In Routledge Handbook of Sport, Gender and Sexuality. Edited by Jennifer Hargreaves and Eric Anderson. London: Routledge, pp. 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reider, Noriko T. 2015. A Demon in the Sky: The Tale of Amewakahiko, a Japanese Medieval Story. Marvels & Tales 29: 265–82. [Google Scholar]

- Riaru Raibu. 2021. Takasu inchō ‘Motomoto Orinpikku wa nyonin kinsei’ ‘Mori kaichō wa o kinodoku’ yōgo hatsugen ni hihan atsumaru. docomo (NTTドコモ). February 8. Available online: https://news.goo.ne.jp/article/npn/entertainment/npn-200011088.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Rich, Motoko, Hikari Hida, and Makiko Inoue. 2021. Tokyo Olympics Chief Apologizes for Remarks Demeaning Women. The New York Times. February 28. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/03/sports/olympics/tokyo-olympics-yoshiro-mori.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Rich, Motoko. 2018. Women Barred from Sumo Ring, Even to Save a Man’s Life. The New York Times. April 5. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/05/world/asia/women-sumo-ring-japan.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Rich, Motoko. 2021. After Leader’s Sexist Remark, Tokyo Olympics Makes Symbolic Shift. The New York Times. February 18. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/18/world/asia/yoshiro-mori-tokyo-olympics-seiko-hashimoto.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Roche, Maurice. 2000. Mega-events and Modernity: Olympics and Expos in the Growth of Global Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, Michael, and John Tosh. 1991. Manful Assertions: Masculinities in Britain Since 1800. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai City Public Relations. 2020. Sumō hasshō no chi: Sakurai. Wakazakura 1: 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sankei shinbun. 2018. ‘Taoretemo dansei no isha ga chikaku ni iru’ Shizuoka Kakegawashi no Matsui Saburō shichō ga haru jungyō de aisatsu. April 9. Available online: https://www.sankei.com/article/20180409-US4WJ5VOQRJP5MAL4FLKYDFA3Y/ (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- SANPAOLO [Sei Pauro Shūdōkai Sanpauro], and Hiromi Mizuno. 2017. Botsugo 50 nenkinen: Hasegawa Roka furesuko, mozaiku no paionia. Tokyo: SANPAOLO. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Andrew. 2017. Nike: The Origins and History of the Greek Goddess of Victory. Ann Arbor: Charles River Editors. [Google Scholar]

- Seiner, Jake. 2021. Sumo Scare? Riders Say Horses Might Be Spooked by Statue. New York: The Associated Press, August 4, Available online: https://apnews.com/article/2020-tokyo-olympics-equestrian-sumo-sculpture-8c9a3588952acf9502221636a5bf29d5 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Shimokawa, Takashi, Futatsumori Osamu, Okuda Toshihiro, Koyama Yasufumi, Furuya Yōichi, Satō Kazuhiro, Shimokawa Manabu, and Shimokawa Tetsunori. 1999. Shin sumō no hossoku to kongō no kadai: Onnazumō no rekishi o fumaete. Kokushikan daigaku taiiku kenkyūshohō 18: 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shūkan bunshun. 2021. ‘Watanabe Naomi o buta = Orinpiggu ni’ Tōkyō Gorinkaikaishiki ‘sekininsha’ ga sabetsuteki enshutsu puran. March 25. Available online: https://bunshun.jp/articles/-/44102 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Slavitt, David R., and Bacchylide. 1998. Epinician Odes and Dithyrambs of Bacchylides. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- St. Michel, Patrick. 2021. The 2020 Tokyo Olympic Creative Team Controversy Underlines Japan’s Pop Culture Failures. OTAQUEST. March 23. Available online: https://www.otaquest.com/the-2020-tokyo-olympic-creative-team-controversy-underlines-japans-pop-culture-failures/ (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Suzuki, Masataka. 2002. Nyonin kinsei. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Masataka. 2003. Nyonin kinsei to gendai. In Onna no ryōiki, otoko no ryōiki. Edited by Akasaka Norio. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Masataka. 2017. ‘Kegare’ to nyonin kinsei. Shūkyō minzoku kenkyū 27: 102–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tagsold, Christian. 2002. Die Inszenierung der kulturellen Identität. Das Beispiel der Olympischen Spiele Tôkyô 1964. München: Iudicium. [Google Scholar]

- Tagsold, Christian. 2011. The Tokyo Olympics: Politics and Aftermath. In The Olympics in East Asia Nationalism, Regionalism, and Globalism on the Center Stage of World Sports. Edited by William W. Kelly and Susan Brownell. Yale CEAS Occasional Publications Volume 3. New Haven: Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University, pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, Kana, and Yoshitake Matsuura. 2016. Hekiga isetsu, 700man-en waridaka JSC ni ‘futō’ shiteki e kaikeikensain. Mainichi shinbun. October 25. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/articles/20161025/ddm/041/050/074000c (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Takeda, Yūkichi. 1996. Shintei Kojiki. Tokyo: Kōdansha. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Teshima, Taeko, and Andrew W. Jones. 2011. Nationalism and Religious Abjection in the 1998 Nagano Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony. Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 25: 1–42. Available online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue25/teshima.htm (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- The Daily Brief. 2021. Sumo Wrestler Plays All the Sports in France TV’s Tokyo Olympics Spot. Promax. May 21. Available online: https://brief.promax.org/article/sumo-wrestler-plays-all-the-sports-in-france-tvs-tokyo-olympics-spot (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Thompson, Lee A. 1998. The Invention of the Yokozuna and the Championship System, or, Futahaguro’s Revenge. In Mirror of Modernity: Invented Traditions of Modern Japan. Edited by Stephen Vlastos. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 174–87. [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer, Kai Michael. 2015. The Goddess of Victory in Greek and Roman Art. In Spirits in Transcultural Skies, Transcultural Research—Heidelberg Studies on Asia and Europe in a Global Context. Edited by Niels Gutschow and Katharina Weiler. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Mark D. 1997. Legal Rules and Social Norms in Japan’s Secret World of Sumo. Journal of Legal Studies 26: 165–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Mark D. 2005. Law in Everyday Japan: Sex, Sumo, Suicide and Statutes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2020. Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/gender-gap-2020-report-100-years-pay-equality (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- World Economic Forum. 2021. Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Yasuda, Yojūrō. 1988. Kokugi sumō no hasshōchi. In Yasuda Yojūrō zenshū. Tokyo: Kōdansha, vol. 33, pp. 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, Reiji. 2018. Banning women from the sumo ring: Centuries-old tradition, straight-up sexism or something more complex? The Japan Times. April 30. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/04/30/national/social-issues/banning-women-sumo-ring-sexism-centuries-old-cultural-tradition/#.Xt4Qf54za1s (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Yoshizaki, Shoji, and Kazuhiko Inano. 2008. Sumō ni okeru ‘Nyonin kinsei no dentō’ ni tsuite. Hokkaidō kyōiku daigaku kiyō 59: 71–86. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

DeWitt, L.E. Japan’s Sacred Sumo and the Exclusion of Women: The Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler (Part 1). Religions 2021, 12, 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090749

DeWitt LE. Japan’s Sacred Sumo and the Exclusion of Women: The Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler (Part 1). Religions. 2021; 12(9):749. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090749

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeWitt, Lindsey E. 2021. "Japan’s Sacred Sumo and the Exclusion of Women: The Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler (Part 1)" Religions 12, no. 9: 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090749

APA StyleDeWitt, L. E. (2021). Japan’s Sacred Sumo and the Exclusion of Women: The Olympic Male Sumo Wrestler (Part 1). Religions, 12(9), 749. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090749