2.1. Factors Affecting the Development of Pilgrimages and Shrines during the Vatican II Era

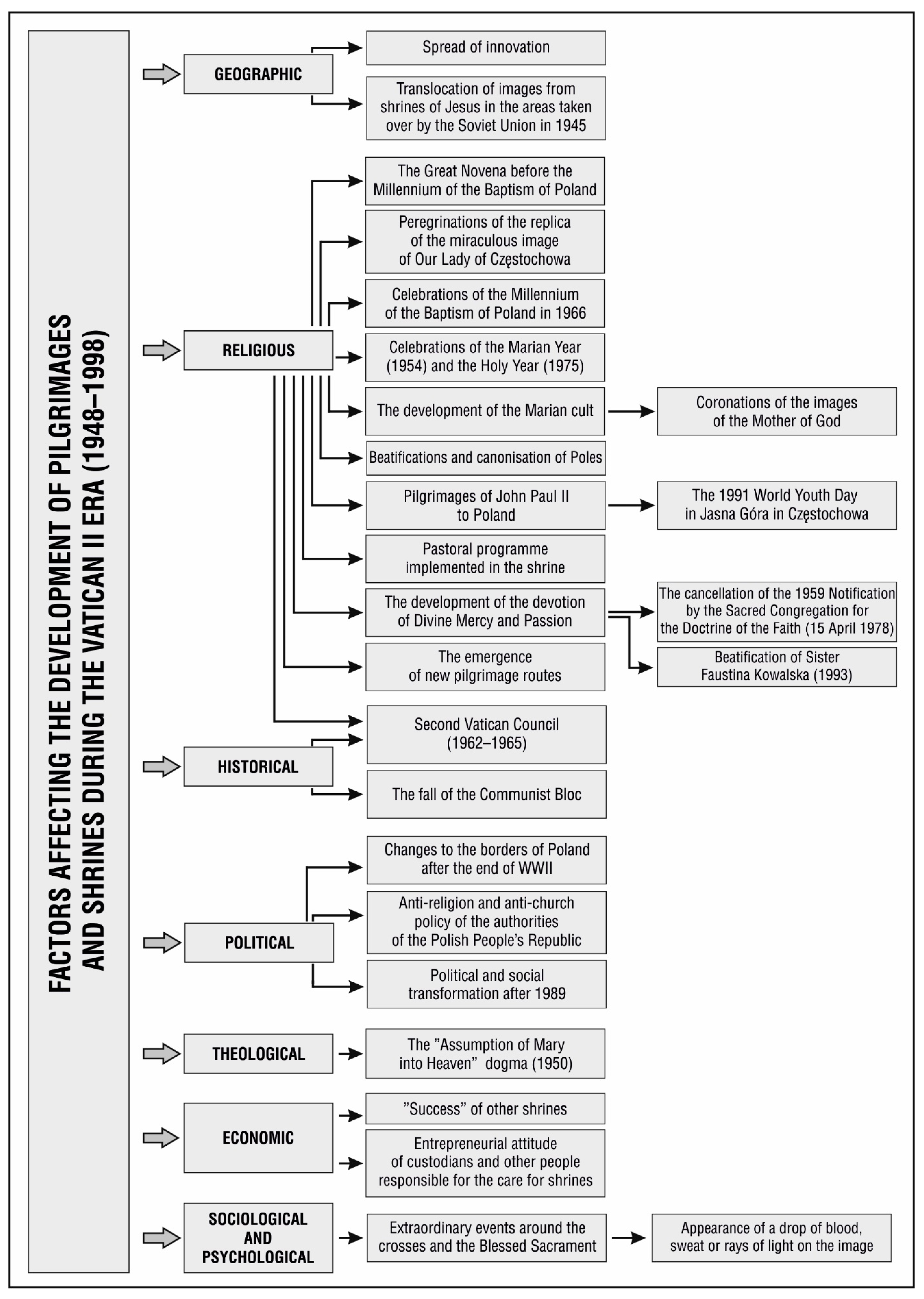

The analysis of the origins and functioning of shrines, and the development of pilgrimages, in Poland during the Vatican II era requires taking into account an entire group of religious, geographic, historical, socio-economic, cultural and political factors (

Figure 1). During the first months of the end of WWII and in subsequent years of the Vatican II era, the Polish pilgrimage space was considerably transformed and changed.

It should be emphasized that during the Vatican II era, the Polish Church struggled with completely different problems than those faced by Churches in Western European countries (

Bartnik 1987). In the case of Poland, one of the key activities on which the philosophy and service of the Church were focused was care for the Catholic identity of the Polish nation, which was heavily restricted and attacked by communist authorities. At the time, the Church in Poland was an important space of freedom. Strzelczyk emphasizes that “the difference in contexts is of immense importance to the understanding of the entire reception of Vatican II in Poland”, because “the main subject of the Council debates, from the theological perspective, was not in the centre of interests of the Polish Church”, (

Strzelczyk 2008, p. 47).

A key step in the preliminary research related to the functioning of sanctuaries and the development of pilgrimages in Poland during the Vatican II era was to take into account the historical context, the transformation of the social and political system in communist Poland, and changes to state borders in 1945. As decreed during the Yalta Conference, Poland lost 48% of its pre-war territory in the east.

Changes in pilgrimages and the network of pilgrimage centers in Poland during the Vatican II era comprise five main time intervals. Pilgrimages in Poland have been characterized by, first, a boom in pilgrimages to Polish shrines from 1945 to 1949, followed by a regression in pilgrimages during the period from 1950 to 1956 as a result of the anti-religion and anti-church policy of the communist authorities of the Polish People’s Republic. The third stage witnessed a distinct increase in pilgrimages during the period from 1957 to 1978, which was mainly the result of preparations for and celebrations of the millennium of the Baptism of Poland and the Holy Year 1975 (the Great Novena before the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland, and processions featuring a replica of the image of Our Lady of Częstochowa to all parishes). Fourth, the intense development of pilgrimages occurred between 1979 and the transformation of the political system, economy and society in 1989, as a consequence of the pontificate of John Paul II, the Pope from Poland, and his pilgrimages to his homeland. Finally, 1990–1998 saw the distinct development of pilgrimages and religious tourism (1990–1998), as especially related to the pilgrimages of John Paul II to Poland, the development of the cult of Divine Mercy, and the beatification and canonization of Poles (

Mróz 2014;

Datko 2016).

The end of WWII and the regaining of independence by Poland in 1945 intensified pilgrimages to Polish shrines. However, the period did not last long, due to the anti-religious and anti-church policy of the communist authorities (

Mróz 2021a). On 12 September 1945, the Council of Ministers of the Provisional Government of National Unity decreed that the concordat concluded in 1925 between the Republic of Poland and the Holy See no longer applied, as it had been unilaterally terminated by the Holy See (

Włodarczyk 1974).

As a result of changes in territory, the Polish pilgrimage space began to include shrines that had not been situated within the borders of the Republic of Poland during the inter-war period (e.g., Bardo Śląskie, Gietrzwałd, Góra Świętej Anny, Krzeszów, Święta Lipka, Trzebnica, Wambierzyce) (

Datko 2016). New pilgrimage centers associated with the cult of images brought from the eastern areas of the Republic of Poland and taken over by the Soviet Union in 1945 were also established. Priests and the faithful who were leaving their home towns in the areas of the former Republic of Poland risked persecution by Soviet communists when removing the miraculous images they had cherished in their parish churches for years (

Kukiz 2000;

Mróz 2021a;

Skowron-Charif 2001;

Sołjan 2002). The relocation of miraculous images of the Lord (more than 10 images), the Virgin Mary (approx. 140 images) and saints (more than 10 images) from sacred sites in the areas taken over by the Soviet Union in 1945 resulted in the emergence of more than 20 pilgrimage centers in Poland after 1945, mainly Marian

loca sacra (

Datko 2016;

Kukiz 2000,

2002;

Mróz 2021a). The change in the eastern border of Poland in 1945 had an immense impact on the reduction in pilgrimages to shrines located near the Polish–USSR border, such as Kalwaria Pacławska (

Mróz 2021a).

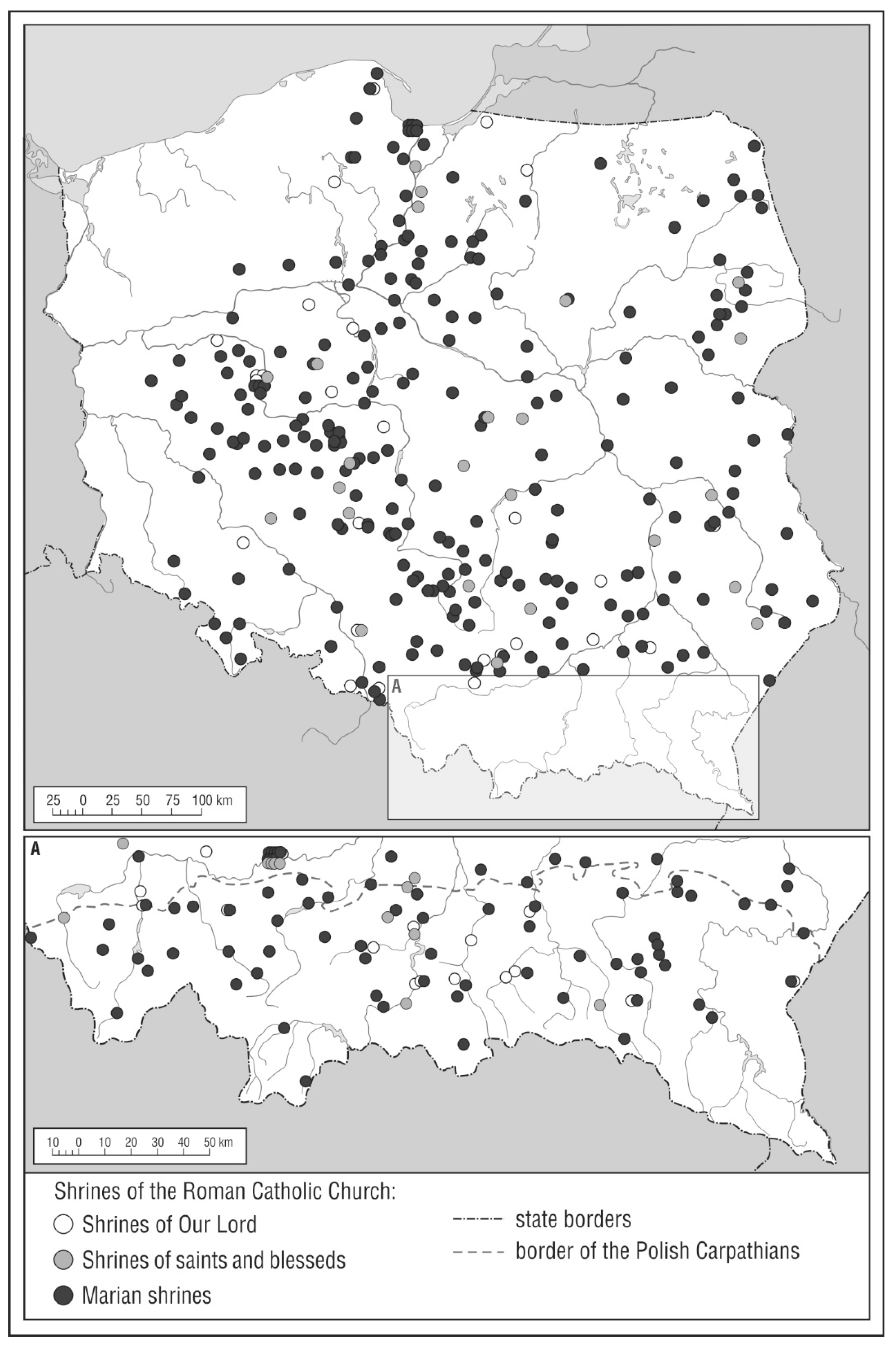

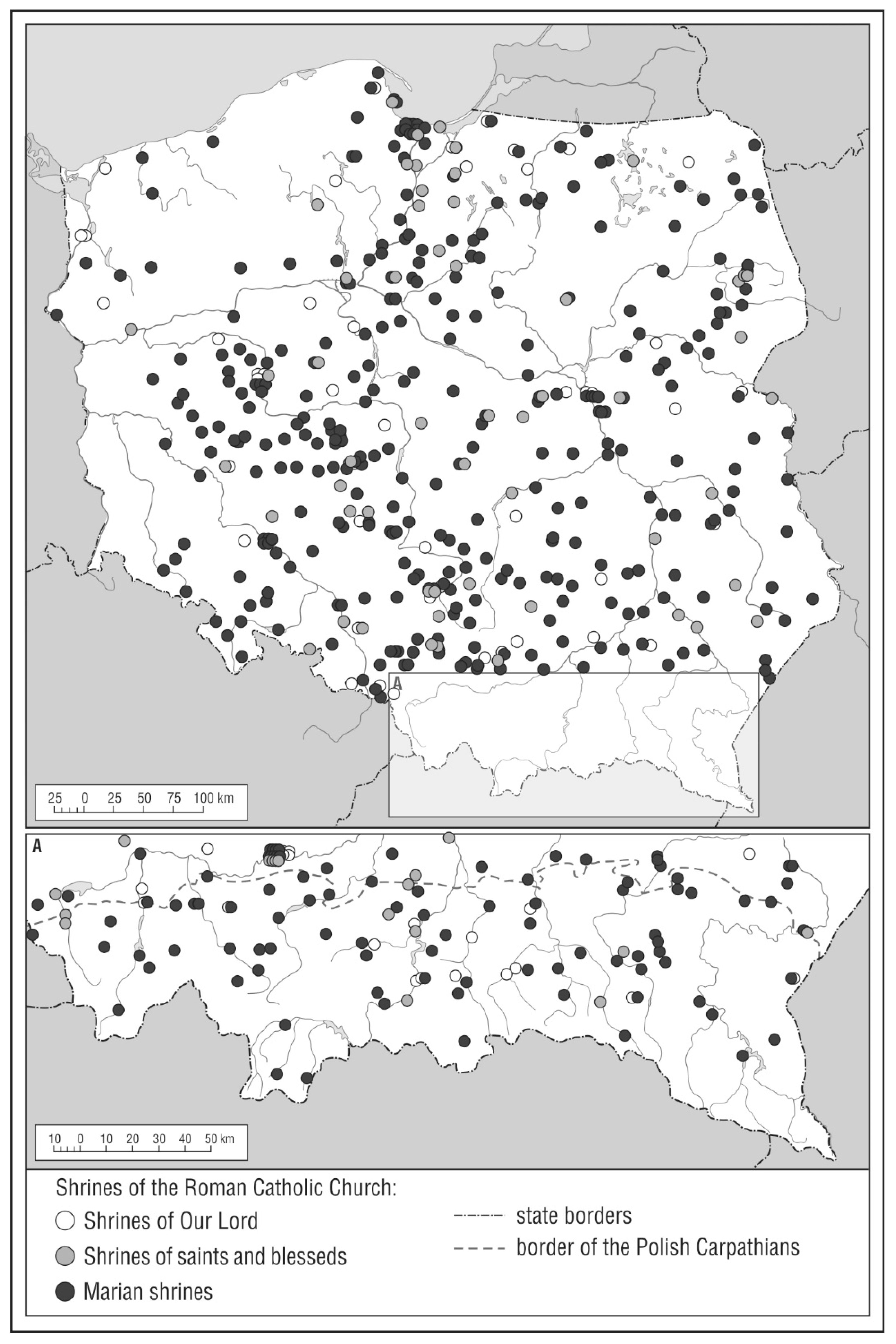

The extensive research undertaken for this article, from archives and shrine custodian interviews, determined that in 1948 there were nearly 400 shrines and pilgrimage sites in Poland. Roman Catholic Church shrines constituted the major focus of pilgrimages during the post-war period. However, several Greek Catholic shrines (Grabarka and Jabłeczna) and pilgrimage sites of Muslims (Bohoniki and Kruszyniany) should also be mentioned here. During WWII, the Nazis murdered almost the entire Jewish community in Polish lands, and destroyed synagogues, cemeteries, and the

ohele (Hebrew: tent) placed over the graves of Hassidic leaders, to which thousands of Hassids had been going on pilgrimages before the outbreak of the war. After 1945, the communist authorities of Poland closed devastated Jewish cemeteries and took steps to completely eliminate them (

Gładyś and Górecki 2005). As regards Roman Catholic shrines, Marian shrines comprised the largest group, with more than 300 sites; 62 of these sites had images of the Mother of God crowned, based on specific papal consent for each location. In 1948 there were still 43 shrines in Poland devoted to Jesus Christ and the Holy Trinity, and 36 shrines of saints and

beati. At the beginning of the Vatican II era, two regions in Poland were distinguished by a density of shrines: the Polish Carpathian Mountains (about 100 shrines) and the historic region of Wielkopolska (more than 70 shrines). At the time, the areas of western and northern Poland, or “Regained Territories” that were allocated to Poland after WWII in accordance with the arrangements made at the Potsdam Conference, were “blank spots” on the map of Polish shrines (

Konopka and Konopka 2003) (

Figure 2).

In 1949, the then authorities of the Polish People’s Republic started to persecute the Catholic Church and impose restrictions on it. For example, the Department of Security arrested several hundred priests, while the Polish episcopate was accused of inspiring anti-state activity in the clergy. The regression in pilgrimages in Poland continued until the early 1960s, despite the fact that communists slightly softened their attitudes during the Khrushchev Thaw and the 1956 political transformation (

Sołjan 2002).

2.2. The Great Novena before the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland

The late 1950s and the early 1960s marked a time of great reforms in the Catholic Church, initiated during the Second Vatican Council, which was opened on 11 October, 1962 by Pope John XXIII, and closed on 8 December 1965 by Pope Paul VI. During that time, the Catholic Church in Poland saw the implementation of the pastoral program, developed by Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński (1901–1981), the Primate of Poland, referred to by Poles as the “Primate of the Millennium” upon his death. Cardinal Wyszyński’s maxim was “I bet it all on the Virgin Mary” (

Okońska 2001a;

Zieliński 2008). His relentless and uncompromising attitude to the attempted atheization of Poland by the communist authorities was vitally important to the development of the awareness in Polish Catholics of what was happening to their society.

Cardinal Wyszyński was arrested on 25 September 1953 because of his defense of the Christian identity of the nation and his firm opposition to the arrest of Bishop Czesław Kaczmarek in January 1951. He was subsequently interned without court judgment until 28 October 1956. While interned, Cardinal Wyszyński made an act of personal submission to the Virgin Mary: “Holy Mother, I submit to your captivity totally (...). The Mediatrix of all graces, everything I do with your Immaculate Hands will be entrusted to the grace of the Holy Trinity—Soli Deo!” (

Okońska 2001b). Three years later, in August 1956, he undertook a nine-year program of religious and moral revival of Polish society—the Great Novena before the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland. The Novena was preceded by celebrations of great anniversaries in the subsequent three years—the Marian Year (1954) declared by Pope Pius XII on the hundredth anniversary of the Immaculate Conception dogma, the 300th anniversary of the victorious defense of Jasna Góra against the invasion of Swedish troops (1955), and the 300th anniversary of the Lviv Oath of King John II Casimir and the declaration of Mary as the Queen of Poland (1 April 1656 in Lviv) (

Kupiszewska 2014).

On 26 August 1956, the Jasna Góra Vows of the Polish Nation took place in the shrine of Our Lady of Jasna Góra in Częstochowa. The prayer, taking the form of an oath to the Virgin Mary, was read by Bishop Michał Klepacz (serving as president of the Polish episcopate) on behalf of the detained Cardinal Wyszyński. For the celebration, it is estimated that an astonishing one million people from around the country flocked to the small town. The empty chair of the primate was a symbol of calls to set Cardinal Wyszyński free.

The social turmoil in October 1956 led to transformation in the top ranks of the communist authorities, resulting in the rise of Władysław Gomułka to First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party. Under social pressure, Gomułka made a considerable compromise with the Catholic Church in Poland and released Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. However, the period of liberalization in church policy was short, and towards the end of 1958, communist authorities returned to repressive activities and harsh attacks on the Church, in particular the clergy. Communists removed crosses from school classrooms, prohibited religious education from schools, did not grant permits to construct new churches, returned to the military conscription of clergymen, and initiated a campaign to destroy sacred buildings. For example, many military chapels and garrison churches were demolished (

Wysocki 2008).

In his speeches, Wiesław Gomułka, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, continually insulted Primate Wyszyński and attacked the millennium program of the Catholic Church. The official inauguration of the Great Novena before the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland saw the participation of Primate Stefan Wyszyński on 3 May 1957 in Częstochowa. The nine-year program of the Great Novena included individual vows, including those to defend life, the Catholic family, marriage, faith, and social justice, as well as to venerate the Holy Mother.

The Shrine of Our Lady of Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, the national shrine of the Polish nation, was a center of key importance when the Great Novena program was implemented. It was also the site of the main celebrations of the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland in 1966, which were led by the Primate of Poland, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. The Polish episcopate invited Pope Paul VI to the event, but Gomułka did not agree to the visit, which became an international scandal. Again, an empty throne was the symbol of his absence. In 1966, approximately 2 million people visited the Shrine of Our Lady in Częstochowa (

Jabłoński 2000;

Jackowski 2005).

Primate Stefan Wyszyński also included other shrines in Poland in the agenda of the Great Novena, which was to prepare Poles spiritually for the celebrations of the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland. For this purpose, a new department for Polish shrines was established as part of the Marian Committee with the Episcopate of Poland (

Kupiszewska 2014). In his speech to the priests gathered in the shrine in Jasna Góra in 1959, Cardinal Wyszyński emphasized the importance of shrines to the development of Polish piety: “Their immense network in all dioceses in Poland, three hundred sources of the grace of Jesus spreading from Mary throughout the whole Country. This is the power! And this power should be used in the work of moral renewal of the Nation, especially when working on the Great Novena before the Millennium”, (

Wyszyński 2006, p. 234). Primate Wyszyński gave the custodians of shrines a duty to perform during the third year of the Great Novena: “to animate all Marian sources of grace during the Year of Life, to animate all Marian shrines, even the smallest, most ‘extinct’ ones”, (

Wyszyński 2006, p. 235).

Earlier, while interned, Primate Wyszyński had developed an idea for the pilgrimage of a replica of the miraculous image of Our Lady of Częstochowa to all parishes around Poland. The replica of the image was consecrated by Pope Pius XII in the Vatican on 14 May 1957. The peregrination of the image started on 29 August 1957 at the Warsaw Archsee (

Okońska 2008). Communist authorities tried to “arrest” the replica of the image of Our Lady of Jasna Góra at least twice (in Liksajny and in Lublin). In September 1966, when the replica of the image was being transported from Warsaw to Katowice, the Security Service ordered that the image be transported to Jasna Góra instead. The processions continued until 1972, with empty frames of the image accompanied by a sign with the words “detained and confined in Jasna Góra.” At the time, the militia and officers of the Security Service checked each vehicle leaving the shrine of Jasna Góra to see if the replica of the miraculous image of Our Lady of Jasna Góra was being transported (

Okońska 2008;

Żaryn 2008).

2.3. The Development of Marian Shrines

Primate Wyszyński believed that Marian shrines played a very important role in the development of Marian piety. With reference to such shrines, he wrote that “even the small and poor ones are like the hand of Immaculate Mary, the Queen of Poland, reached out to help the nation and defend it”, (Królowa Polski w wielu obliczach (Królowa Polski w wielu obliczach: 7). Shrines promoted mass religion, and initiated and supported religious celebrations, which gathered tens of thousands of followers (

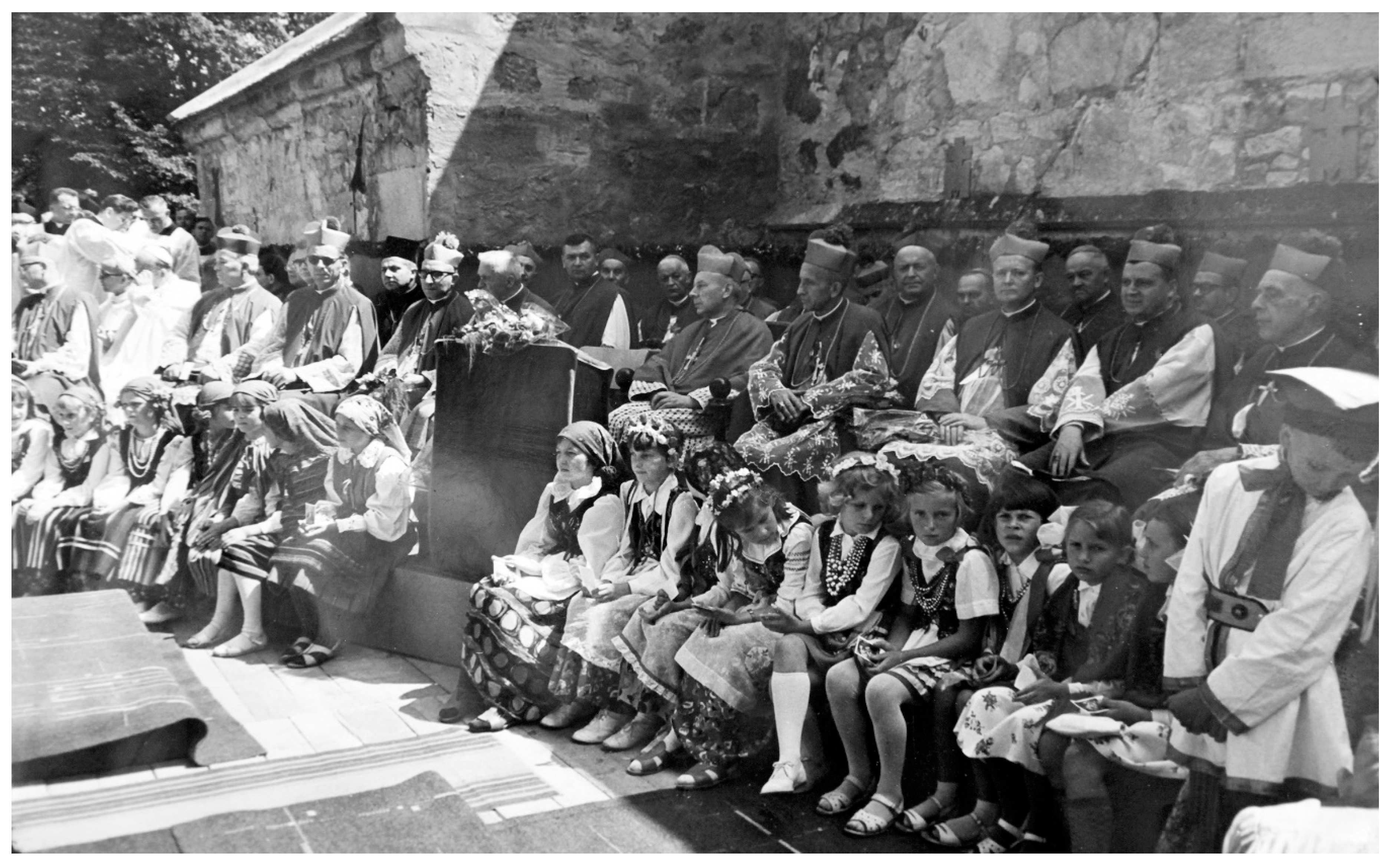

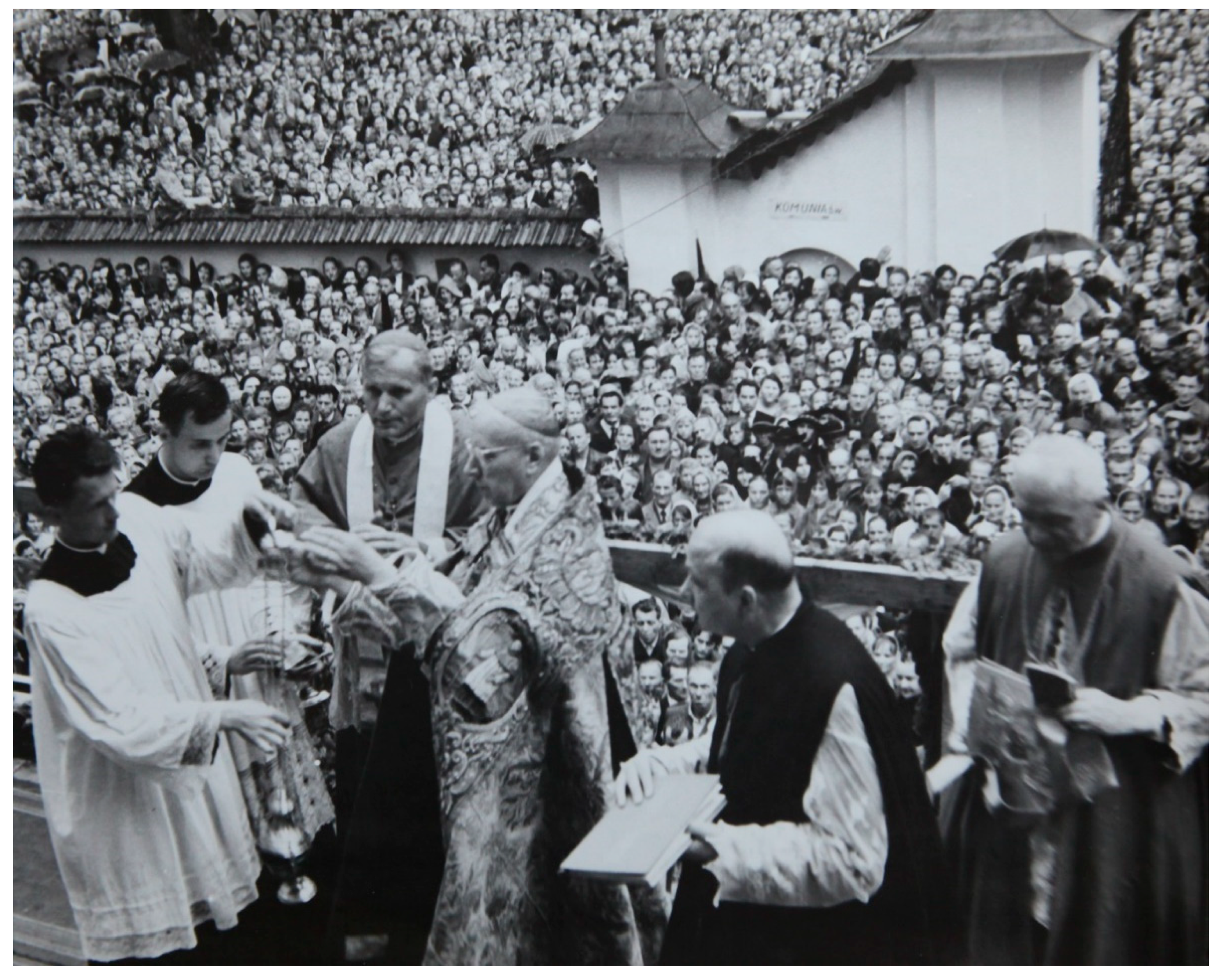

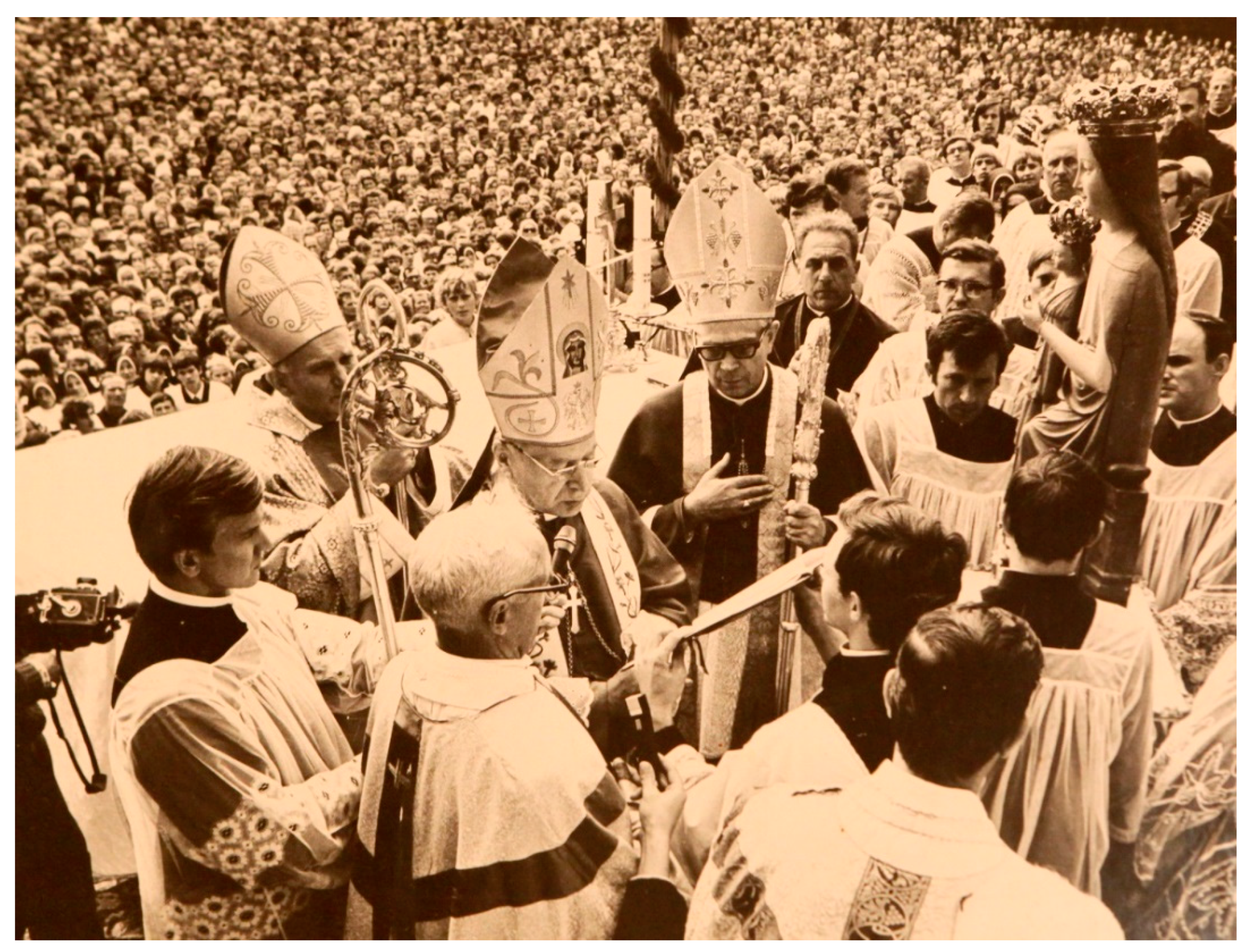

Datko 2016). Such celebrations mainly included coronations of miraculous Marian images. Coronation celebrations, which were mainly presided over by Primate Wyszyński, strengthened the Poles spiritually in their national, social and personal dedication to Mary, the Mother of the Church and the Queen of Poland.

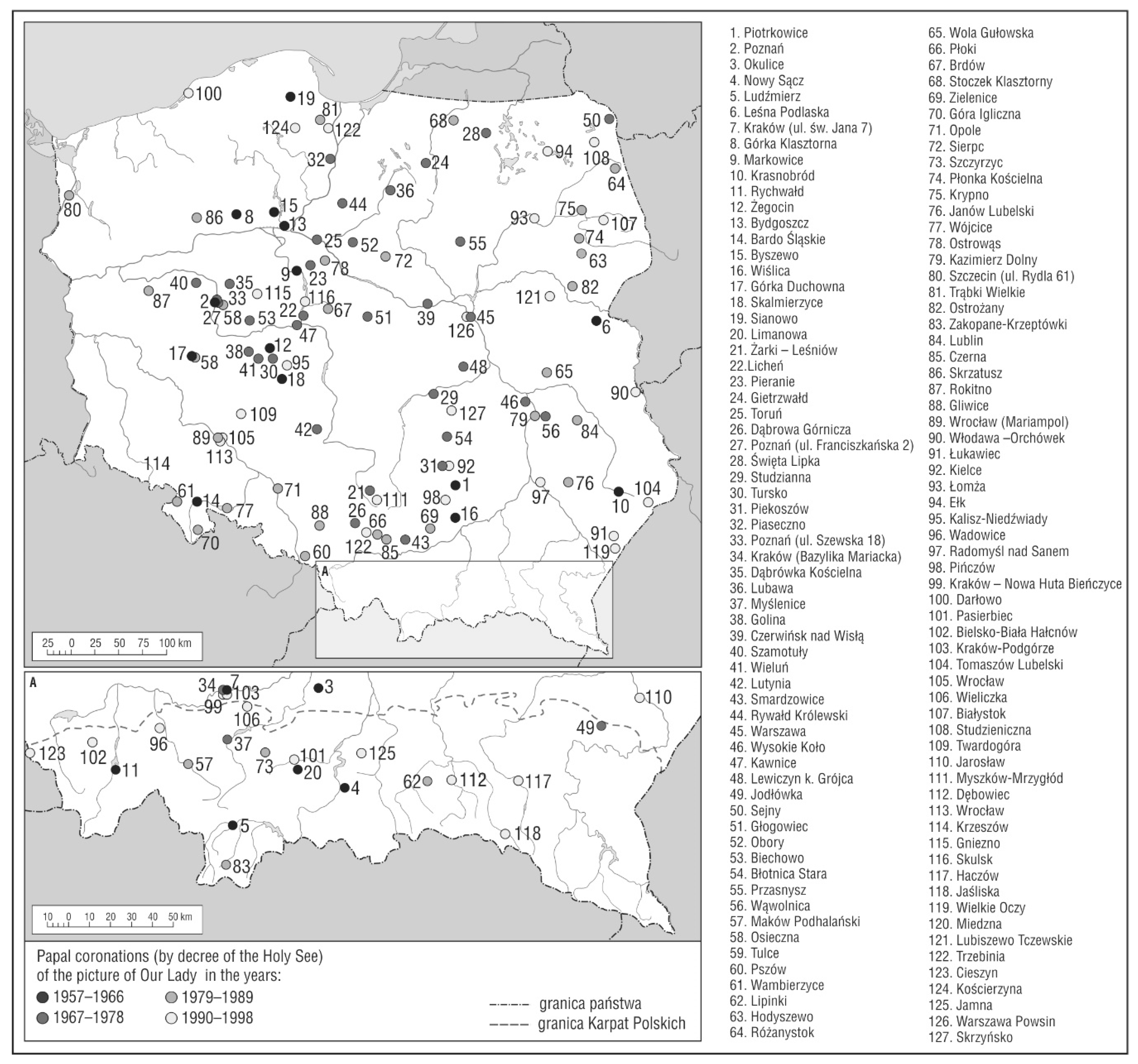

It should be recalled here that the custom of crowning the gracious and miraculous images of the Mother of God has had a long history in the religious life of Poles. The first image of the Mother of God in Poland, the miraculous icon of Virgin Mary in the Church of the Pauline Fathers in Jasna Góra, was crowned in 1717 with the consent of the Holy See. Before the late 18th century, 29 images of the Mother of God had been ceremonially crowned in Poland; during the period of the partitions of Poland, 12 images were crowned (1800–1918), and during the period of the Second Commonwealth of Poland (1919–1939), 22 images were (

Fridrich 1904;

Mróz and Mróz 2012;

Witkowska 1996).

From the end of WWII until 1961, only two celebrations associated with the crowning of images of the Mother of God were held: in in village Piotrkowice (Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship) and in the parish church in Poznań. In the course of preparations for the celebration of the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland, bishops designated at least one image of the Mother of God in each of the dioceses in Poland (

Sołjan 2002). During the period of the Great Novena before the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland (1957–1965), twelve coronations based on papal consent (“in the name of and with the authority of God”) were held with the appropriate consent of the Congregation of Divine Worship. During the Year of the Millennium of the Baptism of Poland (1966), nine images of the Mother of God were crowned (during Millennium celebrations in Jasna Góra on 3 May 1966, Primate Wyszyński crowned the image of Our Lady of Jasna Góra again). In subsequent years (1967–1970), there were 20 coronations (cf.

Grażyna od Wszechpośrednictwa et al. 1999;

Witkowska 1996). It should be emphasized, with reference to the Vatican II, era that the number of coronations of papal images of the Virgin Mary in Poland from 1948 to 1998 (126 coronations) was a rare phenomenon around the world (cf.

Jackowski et al. 1999) (

Figure 3). During that period, the Primate of Poland, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, celebrated the greatest number of coronations out of all bishops of the Catholic Church: a total of 41 coronations and six re-coronations of Marian images (

Kupiszewska 2014;

Datko 2016) (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

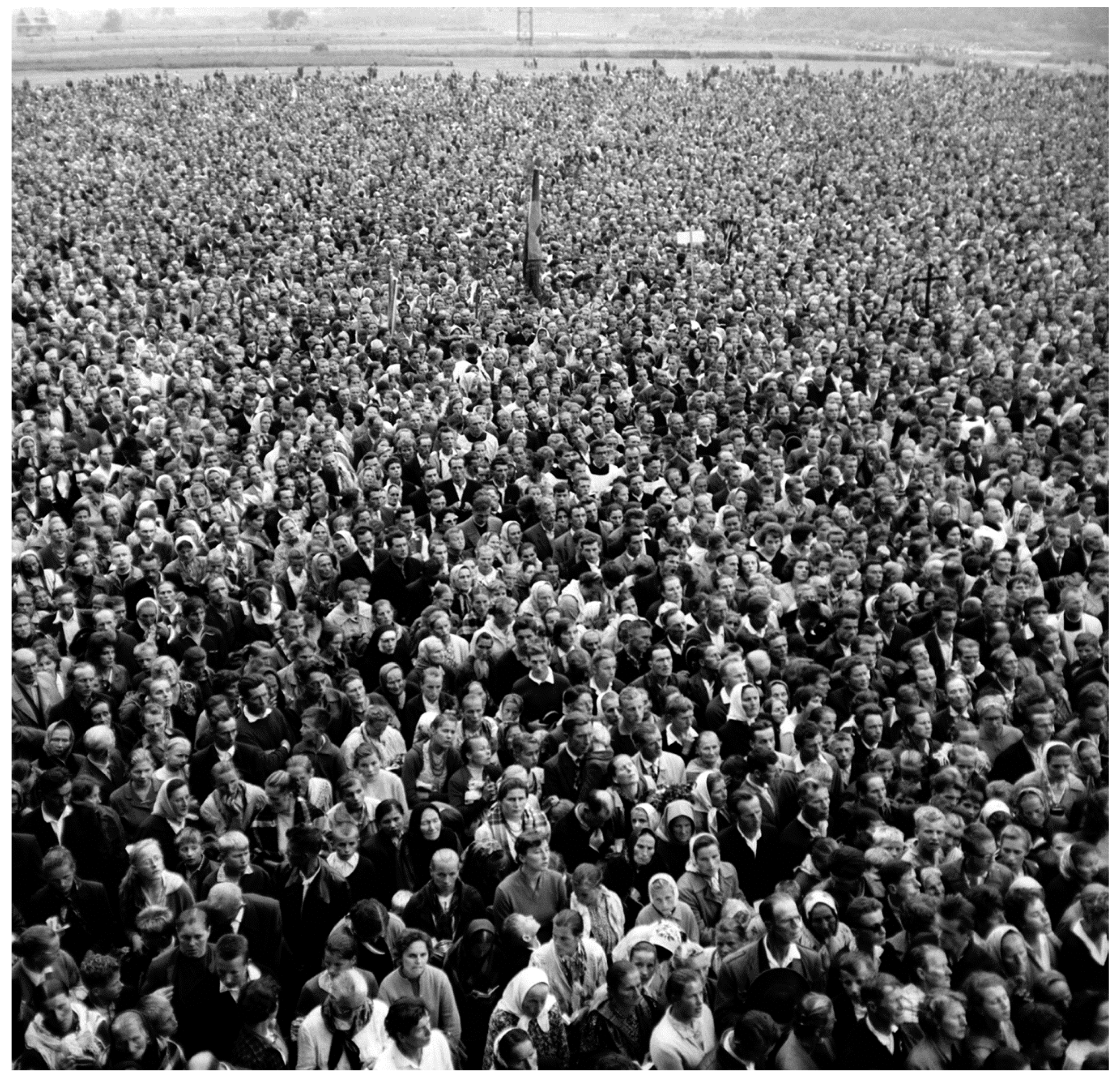

As already mentioned, religious celebrations conducted by Primate Wyszyński and by Cardinal Karol Wojtyła gathered tens of thousands of faithful. The celebrations of the coronation of the image of Mary in Okulice (9 September 1962) saw the participation of approx. 80,000 people; in Nowy Sącz there were approx. 300,000 people, in Ludźmierz approx. 200,000 (

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) in Leśna Podlaska approx. 150,000, in Górka Klasztorna 60,000, in Gietrzwałd 150,000, in Studzianna approx. 150,000 (

Figure 12), in Wysokie Koło approx. 100,000, in Kawnice approx. 50,000, in Błotnica approx. 200,000, in Wąwolnica approx. 200,000, in Pszów approx. 100,000, in Różanystok approx. 300,000, in Wola Gułowska approx. 100,000, in Sejny—over 60,000 pilgrims (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

The national pilgrimages of men, young people, women, school pupils and children to Jasna Góra, associated with the greatest celebrations in the shrine, were some of the leading elements of the pastoral strategy of the Polish episcopate. Such celebrations included the Feast of the Mother of God the Queen of Poland (3 May), the Feast of the Assumption of Mary (15 August) and the Feast of Our Lady of Jasna Góra (26 August). The largest of such national pilgrimages during that period were the following: the National Pilgrimage of the Youth (26 August 1962) with the participation of approximately 500,000 people, the National Pilgrimage of Women and Girls (26 August 1965) with the participation of more than 300,000 women, and the Pilgrimage of Men and Boys (28 August 1966) with the participation of more than 250,000 people (

Jabłoński 2000). In 1982, the First Pilgrimage of the Labour World to the Shrine of Our Lady of Częstochowa was organized upon the initiative of Rev. Jerzy Popiełuszko, and it was continued in subsequent years with the participation of approximately 100,000–200,000 people each time (

Jabłoński 2000).

The Divine Mercy devotion was developed after the end of WWII (

Alvis 2021). In 1946, the Polish episcopate addressed the Holy See with a request to approve the Feast of Mercy based on the visions of Sister Faustina Kowalska. A similar resolution was sent to Rome by participants of the 1948 session of the Theological Society in Krakow. Due to the fact that the Holy See did not reply, the Chief Committee of the Polish episcopate sent a request to Archbishop Romuald Jałbrzykowski to give his opinion; the archbishop refused (

Socha 2000). On 7 March 1959, the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office issued a Notification to prohibit the popularization of the Divine Mercy image and service in the forms proposed by Sister Faustina (

Figure 1). As instructed, many churches had images of the Divine Mercy either removed or repainted, and banned Divine Mercy services. With the consent of Archbishop Eugeniusz Baziak, Divine Mercy images were not removed from the Valley of Mercy in Częstochowa or from the Chapel of St. Joseph in Kraków-Łagiewniki (

Mróz 2008). The College of Divine Mercy was established in the Valley of Mercy in Częstochowa. It was involved in scientific research on Divine Mercy devotion and organized theological symposiums concerning the cult and its essence (

Mróz 2013). Devotion to the Divine Mercy in the forms proposed by Sister Faustina Kowalska was finally revived in Poland in the late 1970s after the cancellation of the 1959 Notification by the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on 15 April 1978.

2.4. Pilgrimages in Poland in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s

In the 1960s, pilgrimages were not only a form of public demonstration of the faith, but also a means to express resistance to communist authorities, on the part of the Polish people. No other country behind the Iron Country noted such processes of the development of pilgrimages and shrines as Poland did. Datko emphasizes that “only mass religiosity could have been effective in opposing the communist ideology used as a tool of oppression and enslavement”, (

Datko 2016). At the time, the Polish pilgrimage space was a space for prayers and debates on social, patriotic and political topics (

Jackowski et al. 1999;

Myszor 2008). Shrines were amongst the main bastions of faith and the Church in the communist state (

Datko 2016).

It is necessary to pay attention to the attitudes of communist authorities towards organizers of pilgrimages and to pilgrims. The authorities of the Polish People’s Republic issued administrative ordinances that were supposed to hinder or even disable the organization of pilgrimages, especially walking pilgrimages, to sacred places. Vehicle traffic was restricted, and scheduled journeys on trains, buses and trams along the routes to pilgrimage sites were cancelled. The militia carried out thorough road inspections, recorded vehicle registration cards, noted and photographed registration plates of vehicles in shrine car parks, and then took measures against the pilgrims who were the owners of those vehicles. Authorities organized cultural events and entertainment for local communities that were designed to compete with traditional pilgrimages. In order to draw the faithful away from participation in pilgrimages, party and state authorities organized football games of first-league teams, as well as international games, speedway rallies, free trips to tourist attractions, and attractive TV broadcasts, to entice people to stay home. The militia and the security service persecuted, detained and inspected pilgrims. Lay pilgrim guides were frequently arrested and taxi drivers were prohibited from carrying the faithful during church fairs (

Jackowski et al. 1999;

Kopiczko 1996;

Myszor 2008;

Datko 2016). Numerous documents (which were confidential at the time) evidence the scale of the efforts taken by communist authorities to thwart the plans of pilgrims and the organizers of pilgrimages.

Officers of the Department of Security also took more extreme measures. Group “D” functioned in the Fourth Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs after 1973 and took “special steps” against pilgrims going to Jasna Góra. Grzegorz Piotrowski, who later killed Rev. Jerzy Popiełuszko, was one of these officers. Piotrowski was given the order to burn the barn of the host of pilgrims, to attempt to rape the host’s daughter, and to contaminate his well during the pilgrimage of students to Jasna Góra (

Dziurok 2008, p. 10). A tragic example was the use of napalm to set fire to the miraculous image of the Holy Mother of Stara Wieś in the shrine in Stara Wieś on 6 December 1968. The arsonist was never found. On 11 August 2006 the Institute of National Remembrance officially confirmed that the image was burnt by the Department of Security and the event was classified as a communist crime. The replica of the image was re-crowned (with the saved golden crowns dating back to 1877) on 10 September 1972 by the Primate of Poland, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, and Bishop Ignacy Tokarczuk (

Mróz and Mróz 2015;

Mróz 2018).

The communist authorities of the Polish People’s Republic also hindered walking pilgrimages to the shrine in Jasna Góra. The only pilgrimage tolerated was the Warsaw Walking Pilgrimage to Jasna Góra (dating back to 1711), which became the all-Poland pilgrimage in the 1960s, and in the 1970s won international recognition. In 1969, approximately 8000 pilgrims participated in this pilgrimage, in 1976 18,000, and in 1977 almost 25,000 people (

Wlaźlak and Sznajder 2009, p. 20). The propaganda of state authorities conveyed the message that the organization of the pilgrimage was a manifestation of civic and religious freedom in Poland. However, the Warsaw Walking Pilgrimage was under the constant surveillance of around 60 agents and officials of the Security Service. Additionally, secret collaborators were recruited. They were offered substantial pay for their operational intelligence activities. For example, in 1981, the Ministry of Internal Affairs paid 300–500 zlotys for ordinary information, 1000–2000 zlotys for accounts of attendance at a Holy Mass, and 3000 zlotys for a tape recording (in 1981, an average monthly salary in the national economy amounted to 7689 zlotys) (

Jabłoński 2000);

www.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 26 May 2021).

The celebrations of the Holy Year 1975 were another important factor affecting the development of pilgrimages in Poland during the Vatican II era. In order to facilitate the grace of indulgences for all the faithful around the world, Pope Paul VI declared the year 1974 to be a Holy Year for all countries worldwide, except for Italy and the Vatican. In Poland, pilgrimage centers where it was possible to obtain the Holy Year indulgence, after fulfilling the prescribed conditions, were designated (

Kupiszewska 2014).

Devotion to the Holy Cross, the Passion and the Holy Sepulchre was one of the main characteristics of Polish religiosity during the Vatican II era. Several new Calvary shrines and shrines of Passion were established during that period: in Licheń, Serpelice, Ujście nad Notecią, Oborniki Wielkopolskie and Krasnobród, the Ecce Homo Shrine of St. Albert Chmielowski in Krakow, and the Shrine of the Holy Cross in Olecko and Rększowice. The shrine in Rększowice was built in expiation for the profanation of the cross by officers of the militia and ORMO (Volunteer Reserve of the Citizen’s Militia) in April 1966. Cross segments that were cut by communists can be found in the shrine, on the main wall of the chancel, and incorporated in the scene of the Last Judgment (

Mróz 2021a, p. 183). In 1951, the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre in Miechów, the oldest shrine of the Lord in Poland, was restored and prepared for veneration. In 1969, after a break of more than 120 years, devotion to the Holy Sepulchre was revived at the shrine in Przeworsk (

Mróz 2000).

When it comes to shrines of the Lord, the greatest development in pilgrimages was noted in the Passion and Marian shrine in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, and in the Shrine of the Holy Cross in Kraków-Mogiła. In August 1974, Cardinal Wojtyła wrote a letter to the residents of Krakow requesting them to go on a pilgrimage to the shrine in Mogiła on 15 September. More than 150,000 people responded to the Cardinal’s call, mostly coming on foot. This was the First Expiatory Pilgrimage of the residents of Krakow to Mogiła (

Mróz 2021a).

The constantly increasing pilgrimage movement is exemplified in the national shrine of Poland in Jasna Góra, but also in dozens of Marian shrines, shrines of the Lord, and shrines of saints and beati. In 1983, Poland celebrated the 600th anniversary of the convent in Jasna Góra. Some of the walking pilgrimages to Jasna Góra were initiated then (e.g., the Kashubian Pilgrimage) (

Jackowski et al. 1999). The pilgrimage of men to the shrine of Our Lady in Piekary Śląskie was especially important at the time. It saw the participation of more than 100,000 pilgrims each year, and often witnessed speeches by Cardinal Karol Wojtyła. During the 1970s, 12.5% of the population of Poland participated in religious pilgrimages, increasing to 15% during the 1980s (

Jackowski et al. 1999).

The greatest numbers of visitors in the history of the Marian Shrine of Jasna Góra were recorded in 1979 (the first pilgrimage of John Paul II to Poland) and in 1991, when the Sixth World Youth Day was held from 10 to 15 August in Częstochowa, with the attendance of Pope John Paul II and approximately one and a half million young people from 77 countries worldwide. The estimated number of pilgrims amounted to 6–8 million people in each of these years (

Jabłoński 2000). The number of participants in walking pilgrimages to Jasna Góra rapidly grew after 1977, and reached a record high in 1991 when 400,000 pilgrims came on foot to the World Youth Day organized in Częstochowa (

Jackowski 2005). Numerous pedestrian pilgrimages to Jasna Góra were initiated for the 600th jubilee of the Jasna Góra convent, celebrated in 1983, e.g., the Kashubian pilgrimage from Swarzewo to Częstochowa, “600 kilometres for the 600th anniversary” (

Jackowski et al. 1999, p. 166).

The beatification on 17 October 1971 by Pope Paul VI of Maximilian Maria Kolbe, and his subsequent canonization by Pope John Paul II on 10 October 1982, influenced the development of pilgrimages to the shrine of the saint in Niepokalanów. However, it should be emphasized that pilgrimages to the site had been increasing since 1954, when the construction of a large Basilica of Blessed Virgin Mary the Immaculate, the Mediatrix of All Graces, was finished. The Primate of the Millennium, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, visited the shrine 37 times.

From 3 November 1984, the tomb of Rev. Jerzy Popiełuszko (1947–1984), the chaplain of “Solidarity”, who was brutally murdered on 19 October 1984 by Security Service officers, became a new Polish pilgrimage site of international importance. The tomb of Rev. Popiełuszko can be found in the Church of St. Stanislaus Kostka in Warsaw. According to data from the Documentation Centre of the Life and Cult and Shrine of Blessed Rev. Jerzy Popiełuszko in Warsaw, his tomb was visited during the period from 1984 to the end of 2019 by almost 23 million people, including Pope John Paul II, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, President of the USA George Bush, Prime Minister of Great Britain Margaret Thatcher and President of the Czech Republic Václav Havel (

www.niedziela.pl/artykul/46270/Z-potrzeby-serca-%E2%80%93-kult-ks-Jerzego; accessed on 11 January 2021).

From 4 to 18 June 1989, the first partially free parliamentary election after WWII was held in Poland. The result of the election is considered to have been the decisive moment in the commencement of political transformation in Poland, which marked the beginning of a new stage in the functioning of pilgrimage centers and the dynamic development of pilgrimages in Poland. Subsequent years saw the transformation of the tourism economy into a market-oriented economy.

In 1988, before the transformation, there were around 500 shrines in Poland—over 380 Marian shrines, 70 shrines of the Lord Jesus Christ, and 48 shrines of saints and beati. During the period from 1948 to 1988, 70 new shrines were established in Poland and 20 shrines regained their cult, resulting in a renaissance of pilgrimages, which had been hindered by the partition of Poland and WWII (

Figure 15).

The pilgrimages of Pope John Paul II to Poland and the beatifications or canonizations of figures from Poland by the Pope had an immense influence on the development of Polish shrines, and on the distinct development of pilgrimages and religious tourism during the period of 1990–1998 (

Mróz 2014). During his pontificate, John Paul II made eight pilgrimages to Poland. Six of them occurred during the Vatican II era under discussion here (in 1979, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, and 1997). In the course of these six pilgrimages to Poland, Pope John Paul II visited more than 30 shrines (

Jackowski and Sołjan 2005). On his pastoral visits to Poland, Pope John Paul II crowned 21 images of the Mother of God (Jodłówka, Łukawiec, Kielce, Łomża, Ełk, Kalisz-Niedźwiady, Wadowice, Darłowo, Wrocław, Krzeszów, Gniezno, Skulsk, Haczów, Jaśliska, Wielkie Oczy, Jamna, Wejherowo, Warszawa, Jaworzno, and Wadowice i Bydgoszcz). It should be emphasized that during his pontificate, John Paul II canonized 9 Poles and beatified 155 (

www.opoka.org.pl/biblioteka/T/TH/THO/25jp/turek_kanonizacje.html; accessed on 29 January 2021). As a result of these canonizations and beatifications, new shrines were established in Poland.

On 18 April 1993, Pope John Paul II beatified Sister Faustina Kowalska, the Apostle of Divine Mercy, who was later canonized on 30 April 2000. The first shrine of Divine Mercy in Poland was established in Częstochowa in 1992. During the Vatican II era, before the end of 1998, five more shrines were established in Poland (Kraków-Łagiewniki, Szczecin, Myślibórz, Kalisz and Ożarów Mazowiecki) (

Mróz 2021a).

2.5. The Polish Pilgrimage Space from the Political Transformation of 1989

The Polish pilgrimage space, comprising the Polish network of shrines and pilgrimage routes, was considerably transformed following the political transformation of 1989 to 1998. From early 1990 to 31 December 1998, 66 new shrines were established with the approval of the local ordinary in accordance with Canon 1230 of the Code of Canon Law. The greatest increase in the number of new shrines was noted in the case of shrines of saints and beati, and in the group of shrines of Our Lord. The establishment of new shrines in Poland was also associated with the development of the cult of the Divine Mercy, and the renewal of the cult of saints and beati who experienced great popularity among members of the faithful in the Middle Ages, e.g., St. Anthony (in Brodnica, Częstochowa, Dąbrowa Górnicza Jasło, Koziegłówki, Mińsk Mazowiecki), St. Adalbert (Bieliny, Cieszęcin, Gdańsk, Gorzędziej k. Tczewa), and St. Joseph (Nisko, Prudnik). It should also be stressed that the development of the cult of Our Lady of Fatima led to the establishment of 14 shrines of Our Lady of Fatima (Braniewo, Biskupiec Reszelski, Elbląg, Ełk, Górki k. Gawrolina, Kraków, Korsze, Lubajny, Olsztyn, Rozogi, Sosnowiec, Trzebinia, Węgrów), whereas the development of the cult of Our Lady of La Salette resulted in the establishment of the shrines in Dębowiec, Gdansk-Sobieszewo and Rzeszów, and the development of the cult of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn resulted in the establishment of the shrine in Gdańsk, Skarżysko-Kamienna and Warsaw. The first decade following the political transformation in Poland was also marked by intensified coronations of Marian images. During the period from 1990 to 1998, 37 coronations of images of the Blessed Virgin Mary were held in Poland based on a papal bull.

The first decade after the political changes in Poland also saw increased coronations of Marian images. In the years 1990–1998, 37 coronations of images of the Blessed Virgin Mary, on the basis of a papal bull, took place in Poland.

From the early 1990s, regional and local pilgrimage routes associated with John Paul II were established. Papal Routes covered hiking routes (mainly in the mountains), bicycle routes and kayak routes, which had been used by the then Rev. Karol Wojtyła (

Mróz 2014). Various shrines began to gradually extend the pilgrimage infrastructure, and underwent renovation works that were almost impossible during the era of Communism. Moreover, it must be stressed that, since the 1990s, pilgrimages of Poles to shrines abroad (mainly Rome, Loreto, Assisi, Vilnius, Lourdes, and Fatima) have also developed (

Ogórek 2006).

On 31 December 1998, almost 35 years after the Second Vatican Council ended, there were more than 560 Catholic shrines in Poland, including over 420 Marian shrines, 70 shrines of Our Lord, and more than 70 shrines of saints and beati. The largest number of shrines could be found in the Polish Carpathians (more than 110 shrines), and also in Wielkopolska, Warmia and Mazowsze. There were also new shrines created in the areas of western and northern Poland (

Figure 16).