Abstract

This paper examines popular indigenous religiosity in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca in the 1990s, in the context of a “progressive” pastoral program formed within the campaign of the New Evangelization, and attuned to the region’s large indigenous population. Based on ethnographic research in an urban Oaxacan context, I offer an account of the popular Catholic ritualization of death which highlights its independence, and sensuous, material, collective orientation. I approach popular Catholicism as a field of potential tension, hybridity, and indeterminacy, encompassing the discourses and teachings of the Catholic Church in continuous interaction with people’s own sacred imaginaries and domestic devotional practices.

Keywords:

Catholicism; popular religion; death; ritual; Vatican II; New Evangelization; indigenous theology; Oaxaca; Mexico The newly dug grave was at the edge of the cemetery. The man carrying the tiny white coffin placed it on the ground next to it. “Facing the sun,” someone instructed. The man opened the coffin lid. The children gathered around, glimpsing in at the beautiful dark-haired baby. Then he stood up and gazing at the infant, suddenly became choked with grief, his hand on his brow. He began a soliloquy, talking about the circumstances of the child’s death, about some conflict concerning the gravesite. Then he reminded us that if we think the houses in which we live are our property we are fools, for these are only homes loaned to us, and, pointing to the grave, this is the eternal home (casa de la eternidad) where we will end up. And here, he went on, no one fights.(From my fieldnotes, November 1989)

1. Introduction

In the southern states of Mexico, Catholicism is continuously reproduced, not just in colonial churches and cathedrals sprinkled throughout the region, but also in people’s homes, in graveyards, around altars in markets, buses, and roadsides, and in other sacred sites embedded throughout the landscape. Sedimented over the colonial era, today’s form of this locally rooted religiosity shows the familiar outline of Catholicism anywhere—the sacraments, the liturgy, the annual round of festivals—but it also enfolds rich, baroque multi-sensory ways of celebrating the divine, life and death, and what we might call an ontology, drawn from elsewhere.

In this article I set out to explain the nature of indigenous Catholicism in the state of Oaxaca. Plastic, vibrant, and ubiquitous, this religiosity escapes any anthropological or other perspective that defines religion according to universals of a distinctive inner mental state of “belief” and the actions it determines (Asad 1993). Nevertheless, while Oaxacan popular-indigenous Catholicism is not determined by doctrine and theology generated within the heart of the Church in Rome, nor is it immune to their influence. Interpretations of local Catholicisms anywhere in the world must therefore consider how a given expression has been shaped by what I refer to here as the institutional Church, be it through changes wrought by evolving Roman teaching or discipline, or the particular histories of given religious orders in a certain place (Cannell 2006, p. 22; Napolitano 2016). In these terms, popular religion, the religion of “the people”, is not a space of complete autonomy and unfettered innovation. Nor do practitioners of popular religion simply bend to the Church’s teachings. Catholicism in Oaxaca continues to be made from an ongoing dialectical encounter of ideas and practices between the Church and devotees over the course of the region’s specific history.

My discussion will focus on Catholicism in Oaxaca in the early 1990s, yet it also draws on several periods of ethnographic research I have conducted since then in both rural and urban areas of Oaxaca state on aspects of religiosity and the Catholic Church. Here I have witnessed and unavoidably took part in a religiosity deeply integrated in the everyday; multi-textured, sensuous, deeply affective, and embodied. In Mexico (as elsewhere in Latin America) religion—especially in its “syncretic”, or “folk-Catholic” versions—particularly among poor, largely indigenous social sectors, is an integral aspect of everyday existence. In Mexico, as elsewhere in Latin America, the term “popular” is used in scholarly and everyday language to describe cultural forms of the lower, non-elite, social classes, and sometimes carries a political, oppositional charge (Rowe and Schelling 1991). From this perspective, popular religiosity is a field of cultural creation generated from “below”, from the desires and existential realities of poor and marginalized communities. More generally, “popular religion” as a designation in early, especially historical, scholarship was criticized for cordoning off such “pre-modern” forms of religious life from an unspecified “official” or “normative ‘religion’” (Orsi 1985, p. xxxii; Hall 1998). Yet, in the Latin American context, the lens of popular religion admits the formation of Catholic Christianity from the power and violence undergirding the colonial project and its “civilizing mission”, propelled in large part by the Church (Mignolo 2000).

At the same time, “popular religion” (or “popular piety”) is also formally recognized within Catholic Church discourse as a domain for potential self-renewal as the institutional manifestation of a global religion that must remain relevant and meaningful within a changing world.1 In this work, I approach popular Catholicism, then, as a field of latent tension, hybridity, and indeterminacy, encompassing the discourses and teachings of the Catholic Church in continuous relation with people’s own sacred imaginaries and domestic devotional practices.

Thus, I address in this paper the content of Oaxacan popular-indigenous religiosity in interaction with clerics and women religious of the institutional Church and the different theologies and pastoral praxes they espouse or which guide their work. Rather than providing a contemporary historical examination of the Church’s evangelizing efforts, this article aims at clarifying, through an anthropological lens, the ethnographic ground on which these efforts were introduced.

I begin below by offering an account of this vital religious form as it developed from the colonial period in the southern part of what is now Mexico, and its character today. Based on my fieldwork in Oaxaca City and elsewhere in the state from the end of the 1980s through the 1990s, I offer an ethnographic account of the popular ritualization of death which reflects key material ethical principles of Oaxacan popular-indigenous religiosity, as seen in the texture and dimensions of religious practice, in context. I then examine the expression in Oaxaca of the “progressive” Catholic movement of the New Evangelization, and its core program of the Indigenous Pastoral (Pastoral Indígena)—both of which arose in the 1980s in Oaxaca—in their encounter with manifestations of popular devotion. As I discuss, the New Evangelization intermingled with the urban popular-indigenous Catholicism I describe in ways that touched on people’s lives, but did not fundamentally alter their ways of being Catholic. The dynamics of this interaction offer insight into the ways the reforms of Vatican II have trickled down to local settings, and the resilience of local Catholicisms.2 Understanding these dynamics demands careful attention to the nature of contemporary Catholic evangelical programs, as they attempt to influence aspects of religiosity that emerge organically from specific cultural settings.

2. The Space of Popular Religion in Oaxaca

A tension intrinsic to Catholicism arises from the Church’s inexorable need to defend the authority of “universal” Catholic doctrine while extending an openness to local cultures and lifeworlds (Mayblin et al. 2017). In Mexico’s southern states, a dynamic interplay of localism and universalism (or of “centrality and periphery”, in Napolitano’s (2016) wording) stems from the region’s high number of indigenous inhabitants. According to official estimates, roughly 70 percent of the population of Oaxaca is of indigenous origin; the state has the highest proportion of indigenous in the country, or about 18 percent of the national total.3 Although for several decades now, Protestant affiliations have attracted huge numbers of Oaxacans in both cities and the countryside (McIntyre 2019), the vast majority of Oaxacans can be seen as “cultural Catholics”, an integral aspect of their identity being anchored in “consuetudinal” or customary, culturally entrenched Catholic symbols and the cult of the saints (Barabas 2006).4 In these terms, Catholicism is the source of a deeply embodied subjectivity, a way of being in the world, rather than simply a nominal “religious” identity. To illustrate the depth of this popular Catholic sensibility, during my fieldwork I often heard that evangelistas (members of Protestant sects) were known to call the Catholic priest so they could confess before they died. Similarly, many Protestants I knew were quite willing to attend—and overtly participate in—certain aspects of Catholic funerals, and still visited the cemetery as part of the apparently Catholic celebration of Day of the Dead (Todos Santos or All Saints’).

My fieldwork in Oaxaca began at the end of the 1980s in Oaxaca de Juárez, the capital of Oaxaca state, where I lived in a neighbourhood or colonia popular on what was then the edge of the city. Soon after arriving I came to recognize that the lives of many of my neighbours, first and second-generation indigenous people from villages and towns elsewhere in the state, represented a kind of hybrid way of life. While they participated in a local globalized capitalist economy in occupations such as school teachers, day laborers, mechanics, shoe-shiners, hotel workers, waiters, housewives, or students, many of them spoke both an indigenous language and Spanish at home; they consulted traditional healers or curanderas for ailments that might not addressed by an expensive visit to a hospital or pharmacy; they raised chickens or pigs on their properties; they often ground corn husks on metates (grinding stones) or made tortillas and mole from scratch instead of purchasing these at the market. A few of them still cooked mostly on open hearths, and slept on both beds and reed mats or petates. Several households regularly received visitors from the family’s native pueblo, and returned there, especially on occasions such as the Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos), the town’s annual mayordomía or patron saint festival, or other important fiestas. Many of them had compadrazgo (ritual kin) networks that still spanned both Oaxaca City and rural towns and villages throughout the state. Popular culture in Oaxaca city thus was constituted through a constant movement between the urban (“modern”) and rural (“traditional”) spheres in a stable oscillation rather than as part of a teleological process of urbanization or rural to urban migration (García Canclini 1989).

It would be problematic to see the above examples as survivals of a pristine indigenous culture in the heart of an urban mestizo5 world, not least because of the ambiguity of the label “indigenous” in Oaxaca and in Mexico more broadly. Here indigenous identity inheres in stable markers of difference vis-à-vis the national mestizo norm: skin colour, language, dress, diet, certain ritual observances, and a location in rural regions, especially in the south; at the same time, in practice, the bounds of indigenousness are slippery and context-dependent. Due to the historic marginalization of rural indigenous peoples in Mexico, indigenous identity is often associated with low socio-economic status more generally. People, therefore, may be regarded by others as “indigenous” even if they do not necessarily identify as such (Norget 2010). While today indigenous identity has impelled new social movements and the celebration of indigenous culture, throughout the country it still bears the negative valences of the colonial era: coarseness, ignorance, naïveté, dirtiness, and also the burden of a traditional culture (including “folk”-Catholicism) perceived to drag down the image of vital, enlightened, modern (Euro-white), officially secular Mexico. Throughout Oaxaca, religion takes part in the ongoing working out of ideas of modernity, tradition, and ethics in the flow of everyday social interaction within and across rural and urban spaces.

What, then, is popular religion in such a place? As noted in the introduction to this special issue, “popular religion” has been formally acknowledged by the Catholic Church as a site of evangelical importance, and efforts were made to incorporate aspects of popular religiosity into the discourses of renovation and reform ensuing from Vatican II.6 In Mexico and Oaxaca, these reforms ultimately spurred both conservative movements such as the Charismatic Catholic Renewal (CCR), and liberal tendencies such as liberation theology which I discuss below (Norget 2004, 2006). Yet, from an anthropological rather than theological perspective, popular Catholicism necessarily encompasses a space of continuous negotiation with the “official” Church (that is, the Roman Catholic Church as an institutional structure of global reach): while Catholics may enfold its teachings and directives into their lives in ways that make them meaningful to them in senses both practical and existential, official Church actors may attempt to hem in or control popular innovations regarded as somehow troubling the stability of doctrine and religious authority. My aim here is not to convey an essential definition of Oaxacan popular Catholicism. Instead, I want to illuminate points of contact—an endless series of approaches and withdrawals—between Oaxacan popular religiosity and contemporary post-Vatican II church evangelical efforts, exploring what this might reveal regarding the endurance of localized Catholic forms far from Rome.

I will first clarify what is meant by the term “indigenous-popular” Catholicism. As the category of indigenousness has been defined throughout Mexico primarily “from without”, shaped in a peripheral relation to the national centre (Molina 2017), the category of “the popular” (lo popular) in Latin America similarly defines not a specific group or geographic location but a relation of marginality. Whether in rural and urban places, popular culture in Oaxaca might therefore encompass recent migrants to the city and members of indigenous populations, or anyone not belonging to mestizo or non-indigenous elite social classes. In “indigenous” towns and villages, which I visited during my earliest period of fieldwork, and came to know better during later research (in the 1990s) on liberation theologian clergy, I was able to gain a better sense of this popular-indigenous lifeworld. These experiences helped me to recognize that the cultural practices mentioned above of my city neighbours, including those of a religious nature, did not emerge from temporary adaptations to city existence. Instead, they were part and parcel of a lifeway whose roots extend deep into the layers of Oaxaca’s past, and point to a resilience of relations between humans and divine beings, including saints and the dead, that gave rise to behaviour and actions that were at once individual, social, and collective. While these events were undertaken in ways not wholly separate from the Church or Catholic doctrine or teachings, they do point to the gap between the intentions and rationales of pastoral programs, and the desires, motivations and material logics underlying popular religiosity.

3. History

Today, popular religion in and around Oaxaca, centred on the cult of the saints and a rich array of religious forms that are largely independent of the church, embodies the logic of a traditional moral ecology emerging organically from this-worldly, everyday concerns. As a result, popular religious expressions and practices persist on the physical and conceptual peripheries of everyday life in Oaxaca. They are reservoirs for the construction of local identities and the re-creation of everyday material reality as a sensuous, multi-faceted and meaningful collective undertaking.

Appreciating the dimensions of this ethically anchored popular religiosity requires attention to its historical development in colonial Oaxaca, and the nature of concurrent shifting Church evangelical strategies. A detailed picture of the formation of this religious complex is not possible here, but I will sketch briefly its most important features. In the early sixteenth century, the first itinerant missionaries (Dominicans) in Oaxaca encountered a difficult topography and widely dispersed villages that hampered early Catholic friars’ efforts at regular instruction in Christian doctrine (Terraciano 2001; Münch Galindo 1982; Gillow [1880] 1978). By the late 1600s, a new baroque emphasis on the use of saints’ images in the Church’s “pedagogy of the sacred” (Gruzinski 2001) encouraged a rapprochement between Catholicism and currents of autonomous, locally anchored, image- and miracle-centred currents of indigenous religion (Norget 2008, p. 138). Sensory, spectacular, and emotionally evocative Spanish and indigenous sacred systems merged in an enduring, though never fixed, way, producing a plastic, heterodox religiosity which showed some capitulation to Christian teachings at same time as Indians7 retained crucial aspects of their old sacred practices.

The common thread in indigenous sacred forms—often referred to by early missionaries as “idolatry”—was a perception of the natural world as the source of health, fertility, protection and general well-being. Local myths designated caves, hills, or sources of water as places of origins of distinct peoples. Saintly miracles promoted by the Church exploited indigenous tendencies toward local, concrete, deeply affective interaction with the supernatural, and a cosmovision in which the sacred beings were essential icons and constituents of local identity (Norget 2008, 2011). Key to the entrenchment of this vital Oaxacan indigenous religiosity was the establishment and subsequent growth of cofradías (lay religious brotherhoods or sodalities, centred on devotion to a saint) which evolved towards the end of the colonial period into the institutional core of indigenous communities (Whitecotton 1977; Taylor 2016, pp. 54–55; Molina 2017). The communal infrastructure of the brotherhoods, which encouraged mechanisms of material and labour exchange, redistribution, and mutual support within communities, fostered local identity, and indigenous norms and practices of territorially rooted, corporate “ethnic” solidarity (Carmagnani 1988).

By the end of the eighteenth century, indigenous religion in Oaxaca had crystallized around the cult of community patron saints. Fiesta celebrations for the saints had become much more than “religious” occasions as defined by the Church. Commemorating community identity, they encompassed practices, actions, and beliefs that went far beyond Church teachings and official bounds of propriety, reflecting a fervent attachment and devotion to saints that was affective, interactive, continuous, and which anchored local community identities. The independence of indigenous Catholicism was enabled by the relative scarcity of clergy attending Oaxaca’s vast rural regions through the entire colonial period, a pattern extending well into the 20th century.

Still today, the round of annual fiestas based on the elaborate and multi-dimensional devotion to the saints, and sustained largely by the labour of women, remains the core of domestic and community religious festivities in both rural and urban areas of Oaxaca. While it would be problematic to suppose a direct continuation of an original logic of Oaxacan indigenous sacred experience, elements of the general sensibility and ethical orientation of past habits of sacred experience still pervade contemporary popular religious practice (Norget 2006). Nurturing an intimacy of relationship between humans and divine beings (be they saints or the dead) these practices regularly reawaken and reinforce critical forms of community and communal exchange. In effect, they make possible the performance of the ties that bind, that make life possible within particular conditions of precarity and marginality.

4. Death in Oaxacan Popular Culture

While many current collective Catholic practices in Oaxaca are under the official direction of the Church or the state—mass, or public aspects of religious fiestas—much of the daily activity that an outsider might recognize as “religious” goes on outside the physical confines of the church and its hierarchy’s sphere of influence. Most of the devotional expressions that attend to the cult of the saints, for example, illustrate popular religion’s domestic-oriented, dynamic, rich, affective texture. In Oaxaca the saints are visible, tangible beings who have practical needs and emotional capacities—love, capriciousness, sorrow, anger—and power to grant favours large and small. Thus, sacred images on household altars are clothed, visited, offered food and flowers, caressed, conversed with, or sung to in the same way as any beloved person. Kissing or touching an image of a Virgin, Christ or other saint, brushing them with a piece of clothing, flower, or herb, allows the transfer of a material sense of the sacred or divine. Rather than some transcendent or abstract dimension, sacredness in these terms is an incarnated and tangible reality that belongs to the here and now of the everyday. In peoples’ rather intimate and deeply affective ways of interacting with saintly beings, and in their choice of saints for special devotion—be these officially recognized saints such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, or unrecognized, quintessentially “popular” saints such as the Santa Muerte (e.g., Lamrani 2018)—we see a self-sufficiency, vibrancy, and innovation that are integral to Oaxacan popular Catholicism.

No other domain of religious practice condenses the communal thrust and deep sensuousness and vitality of popular religiosity more than the ritualization of death, as evident in the series of popular funeral rituals and rites, including the Day of the Dead. Often several hours long, warm and intimate, the many such events I have taken part in in Oaxaca see strangers, neighbours, and friends came together to pray and care for the difunto (the deceased, as she is now affectionately called), and for each other. The death, in 1990, of Alfredo, a much beloved older man in the local parish who originated from the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, reflects central aspects of a singular popular moral ecology of death that demonstrates a subtle yet significant reworking of Catholic doctrine. In keeping with the material nature of a sacred imaginary in Oaxaca, the journey undertaken by the dead is conceptualized in rather concrete spatio-temporal terms, and encloses a journey whose teleology closely intertwines the fate of the living with that of the dead.

Alfredo was a retired bus driver whose health had taken a steep decline in the wake of a stroke. After he died, his body was placed on a cross of powdered lime on the floor of the home he had shared with his wife, and his son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren. There he remained for some time, while, as people explained, his soul or spirit became absorbed by the cross; a brick placed under his head indexing the initiation of Alfredo’s process of penance. His body was then transferred to a coffin for the wake or velorio later that night. A large black ribbon was hung above the entrance to the metal fence around his property, which remained open, welcoming the scores of people—compadres (“fictive kin”) relatives, neighbours—who arrived later that evening to say goodbye to Alfredo and offer their support to his family. Alfredo’s velorio was also the first of nine nights of rosaries, referred to as the Novenario de los Difuntos, or more commonly, simply novenario, during which prayers are said for the salvation of the deceased’s soul. As with the novenario evenings, visitors brought small gifts—flowers, mole, sweet bread, candles, offered coffee, hot chocolate, tamales, or sweet rolls as gifts for Alfredo’s family, items which were then consumed as part of these collective gatherings or convivencias. On this and other prayer evenings, mezcal (an agave-based liquor ubiquitous in Oaxaca) was served later in the night. Thus, such foods and other items were metonyms of the network of concrete substantive and affective links that existed among those present: relatives, friends, and compadres.

The next afternoon, Alfredo’s body was carried to the church for the funeral mass—the Misa del Cuerpo Presente (Mass of the Body Present)8—in the back of a borrowed truck. The church bells tolled slowly as six pallbearers carried Alfredo’s simple casket inside the church, setting it at right angles to the altar. The pews quickly filled, and the priest delivered a short sermon focused on the significance of death, and its relation to salvation and Christ’s resurrection. At the end of the mass, Alfredo’s casket was then transported to the cemetery where it joined the entourage of us who had arrived earlier. The sky had turned dark and cloudy as a man holding a large three-foot wooden cross led us into the graveyard. The pallbearers, holding the coffin aloft, followed the cross; as they passed us, members of the group fell in behind them, saying rosaries and singing hymns. As the procession moved slowly into the cemetery, a man waved an incense burner in the coffin’s path. Someone had hired a small group of musicians who accompanied us, and as we stepped carefully through the tightly packed graves to a freshly dug site in a new section of the cemetery, they played a slow and plaintive version of the oft-heard popular song, La Canción de la Mixteca—the region in Oaxaca’s northwest where Alfredo was from. His widow, Eleuteria, who had fainted just a couple of hours earlier before the funeral, was weeping, her body propped up by two women on either side of her.

Before Alfredo’s coffin was lowered into the ground, a couple of his compadres opened his coffin so that we could all offer him a final farewell. A cemetery worker and a couple of men in the funeral entourage slowly lowered his coffin into the grave by the means of two thick ropes. Rosary prayers continued, led by the rezador or prayer specialist, Gustavo, who had presided over the wake, and would be there for all nights of the novenario. As Alfredo’s coffin disappeared into the grave, we all tossed a handful of dirt on top of it; a couple of people did so in the form of a cross. I was told later that, as with resting his head on a brick before the wake, this was a way for Alfredo to gain indulgences. Overcome with emotion, Eleuteria refused to throw dirt into the grave. “Throw dirt to him, comadre,” Guillermo, her compadre urged. “Throw dirt, or he can’t rest!”. Finally, with her daughter supporting and moving her arm for her, she did.

We tossed flowers into the grave as well. Alfredo’s compadre poured the contents of a bottle of holy water over the coffin—again, in the form of a cross, giving him a final blessing. The grave was then filled with earth, by a small group of men in the funeral party. His son took out a bottle of mezcal and distributed in little plastic cups. By this time, Alfredo’s daughter had led Eleuteria, her body curled forward and heaving with her sobs, away from the gravesite. Finally, Alfredo’s son and a couple of compadres ensured the wooden cross that led the procession to the gravesite was embedded in the earth at the head of the grave, and flowers and small lighted candles were placed all along the grave.

From my observations, interviews, and many more informal conversations with Oaxacans, I learned that death-related rites in Oaxaca see the living care for and help the soul of their difunto/a (dearly departed) to die “well”, and ease their transition to a new life in the afterworld, or mas allá. The sensuous, protracted, demanding and extravagant character of the popular ritualization of death serves to build and cement reciprocal communal ties, links and dependencies within a framework that strongly articulates the nature of the “good.” In other words, biological death does not signify the extinction of someone’s life as a social actor. Instead, the dead continue to exist in the lives of their surviving relatives, and the world of the dead and that of the living are tightly linked in practical, material and emotional exchange and interaction. Theological explanations cannot fully account for what a “good death” is in Oaxaca. The dead belong, even as they are dead, to the community of the living. In these settings, time and energy are invested in events that bear little or no resemblance to church-led rites; certain social roles are exaggerated and stylized. Such occasions elicit repeated enactments of fidelity to a mother or father, “proper” neighbourliness, the carrying out of compadrazgo obligations, displays of self-sacrifice, and so on. I witnessed how people demonstrated their care for the difunto/a, and in doing so enacted and revitalized an ethic of care for each other with reference to an ideal of community—even if their behavior outside of these sacred spaces sometimes contradicted such ideals.9

Aside from the funeral mass that precedes the burial, rituals of death are not the province of the church, but the home. Throughout Alfredo’s novenario, and in many others I attended, it was women, not men, who took charge of this ritual space, the rosary prayer evenings rendering it overtly sacred and central in the project of ensuring the safe passage of Alfredo to the mas allá. Every evening during the novenario, Gustavo led prayers in the family house, which took place in the room where Alfredo’s body had lain during the wake. Here we gathered, some sitting on rented metal folding chairs, some standing, before the lime cross on the cement floor, now decorated with candles; we read scriptures, recited the rosary, and sang. After each session of prayer and song, the group of those in attendance would break up; those who remained in the room were invited to gather in the patio for coffee, hot chocolate, and bread.

By the ninth and final night of the novenario, the painful weight of Alfredo’s death seemed palpably to have lessened: conversation among those present was lighter, his widow Eleuteria now assuming a more active role in greeting visitors and coordinating the preparation and serving of food and drink. During the day, the official rezador, Gustavo, had made a tapete de nueve días (carpet of nine days) over the lime cross. The tapete was created from a base of moistened sand or sawdust that had been coloured with powdered paint in an image of Christ Alfredo had been fond of, embellished with flower blossoms and candles; it was the focus of the ceremony scheduled for that evening: the Levantada de la Cruz or the Raising of the Cross, which would mark the last farewell to Alfredo’s soul before he traveled to the land of the dead. Significantly, I often heard people refer to the Levantada as a “second burial;” this is perhaps because it enacts a removal and separation of the spiritual remains of the difunto from a prior domain of existence—the home, the realm of the living—to the cemetery, or the realm of the dead. The lime cross covered by the tapete thus acts as a “second body” of the dead, retaining some material essence of the difunto.

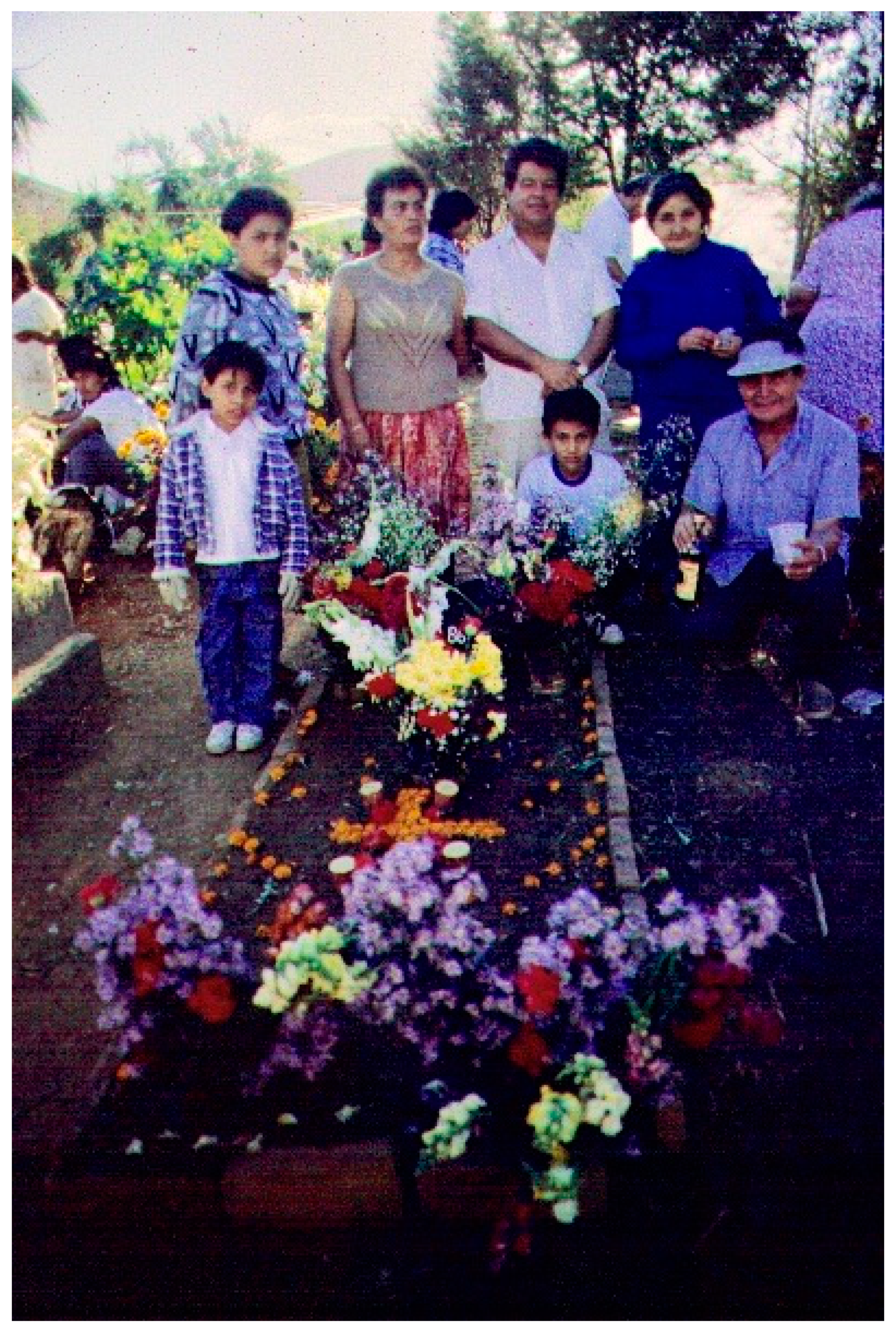

That night, following the final session of rosaries, Gustavo directed the “raising” or “taking up” of the cross and the entire tapete containing it, by five compadres or godparents specially chosen for the event (Figure 1). The ceremony was timed so that the “taking up”—the scraping up of sections of the “body” of the cross—was completed just before midnight so as to end the novenario appropriately at the end of the ninth day. (In some pueblos, the final night of the novenario, including the Levantada, is an all-night affair; everyone present goes to the cemetery to bury the remnants of cross and tapete at dawn.) The first godparent “took up” the head of the cross, carefully brushing its entire contents into a cardboard box; the next godparent, its right arm, the third its left arm, the fourth its “heart” or center. Finally, the fifth godparent “took up” the foot of the cross. Once the tapete had been completely “raised,” a rite called the Adoración de la Cruz (Adoration of the Cross) began. Every person present, beginning with Alfredo’s relatives, and then the five compadres de la cruz (godparents of the cross), took their turn in kissing the crucifix from the household altar, which had been placed on top of the tapete. As each mourner kissed the cross, the rest of us followed Gustavo in reciting a line from a prayer called the “Adoration of the Holy Cross”.10

Figure 1.

Dividing the Novenario “tapete” for the Levantada de la Cruz ceremony (photo by author).

The next morning, we returned to Alfredo’s home for another rosary session; we then repeated the prayer of farewell, first said before the difunto was taken to the church for the funeral mass. The “godparents (padrinos) of the cross” then took the cardboard boxes filled with sand carpet scrapings to the cemetery; the rest of us brought along the flowers and candles that had adorned the tapete. One compadre took a shovel and carved a depression in the form of a cross in the earth over the burial mound. Prayers and singing continued while each godparent took a turn at pouring the contents of the cardboard box he carried into this crucifix, then sprinkled the grave using a flower dipped in holy water. The earth was smoothed over to cover up this tapete-filled cross, flowers and candles placed on top of the mound. Gustavo then offered an oral summing-up of the novenario and words of thanks. Another period of convivencia or social gathering followed the departure from the cemetery.

This brief description of Alfredo’s novenario foreground death and burial as part of a protracted social transition guided by the need for proper care and treatment of the body of the dead, and of the dying by the living. Because the dead can remain “wandering” in a perpetual state of penance, it is important to ensure that those who go on living will continue praying and interceding, soliciting God’s mercy on the behalf of the dead. Funeral rites allow for a kind of resocialization of the dead—one that is painstakingly gradual and affectionate—for some form of closure and control of unrest. Unless sufficiently cared for at the point of death, difuntos may remain with the living and haunt them, causing mischief or even misfortune. Once a person dies, she therefore needs the help of those who are living to pay—pray, make offerings, accompany her—for her sins. Yet, aside from the priest who conducts the funeral mass, the series of complex death-related ritual performances and events was carried out quite independently of the institutional Church: instead, it is the community of relatives, friends and neighbours that administers the care that death demands, a care that is tenderly addressed not just to the difunto/a but to those that she or he leaves behind.

The popular Oaxacan perception of death renders it a kind of journey, not linear or geographic or temporal, but material and cyclical. My neighbours spoke of death not as an extinction of life, but as a paso, step, a spiritual transition from one state to another, be it better (heaven) or worse (hell). The material, physical body becomes a site both for gauging a moral transformation, and also for focusing care of the difunto/a while they are undergoing that transitional journey. Moral valuations routinely accompany and preside over the decomposition of the body in the cemetery; changes in the physical condition of the body, its dissolution and dissipation are bound, by popular eschatology, to shifts in the fate of the soul. In accounts of the afterlife which people offered me during my fieldwork, I learned of the flexibility and malleability of popular eschatology and its ideas of fate, which focus, in particular, on the indeterminacy or mutability of outcomes, the possibilities of intervention by the living in the fates of the dead (Norget 2006). My friends and neighbours visited their dead regularly in the cemetery, speaking to them at their gravesites; they dreamed of them and interpreted these dreams as messages, and they placed their photos on their home altars alongside images of saints and popes. The dead were gone, but also remained—as (sometimes tangible) presences, as interlocutors, as advisors, as vital memories—in the world of the living.

In Oaxaca, I came to see that death-related practices emanated organically in everyday life; funeral rites were the space where a certain popular ethical system and its related customs and social relations were repeatedly dramatized in vibrant form. While in the urban context there is more variability in people’s adherence to these practices, and in details of their content, both novenario and Levantada followed most deaths I witnessed. That it was necessary to follow them was never questioned. Thus, despite living in precarious financial situations, I saw families draw on whatever sources were available to them—family, compadres, neighbours—to secure the necessary funds in the end to enable their difunto/a to die “well”. In popular communities in Oaxaca such as the colonia neighbourhood I’ve described, funeral rites offered a critical social stage to create the image of an ideal community; one establishing a unity of purpose between living and dead, as well as forming a visceral sense of local identity and social memory.

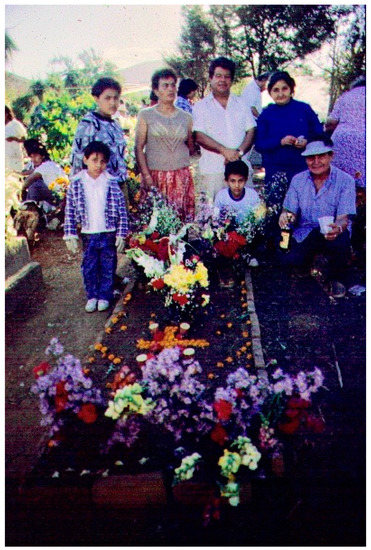

The Oaxacan celebration of the Day of the Dead, the well-known Mexican version of All Souls’ and All Saints days at the beginning of November, is another critical part of this cycle of reciprocity and sensuous exchange in the service of interpersonal connection and community (Figure 2). The festival marks the return visit of the dead to the land of the living to commune with those they left behind. Domestic household altars are expanded to include brightly coloured flowers, candles, sugar skulls or toy skeletons (calaveras), and strongly flavoured traditional food (pan de muerto (bread of the dead), mole, chocolate, tamales, oranges, apples, squash) and drink (hot chocolate, sweet coffee, mezcal, Coke) offered to specific difunto/as and to the dead in general. Officially recognized as a holiday, the fiesta sees people visit their friends and relatives for convivencias, often bringing along the same foods that are on the altar. Cemeteries are also sites of communal gathering as people gather with family members, often for hours at a time, at newly cleaned, repainted and adorned graves of their difunto/as, there to share a meal or to chat, share memories of the dead, or simply to remain silent, though still “accompanying” them. Musicians—mariachi groups, or a single singer with a guitar—wander amongst graves adorned with a profusion of flowers, more candles, balloons, offering their services. The world of the cemetery—the domain of the dead– becomes a kind of conjuring of ideal relationships between extended kin, compadres, and the community more broadly.

Figure 2.

Family beside the grave of their difunto in El Marquesado. Cemetery, Oaxaca de Juárez, Oax., 1989 (photo by author).

I have drawn attention in the above account of the popular ritualization of death to a sacred sense and moral imagination not easily captured by Catholic theological reasoning when official church actors translate this into evangelical practice. This is especially the case where the church intervenes in public and more private or domestic settings of popular religious practice. Again, we have a situation where a dominant normalizing concept of “religion” is not appropriate when attempting to “translate” other religious traditions (Asad 1993); I would add that this is also the case for syncretic expressions of Christian tradition such as Oaxacan popular-indigenous religion.

5. The Oaxacan Church and Popular Religion

As noted above, popular religion is not a clearly bounded, stable set of distinct beliefs or practices. Instead, it emerges from a process of negotiation within church efforts to cultivate ideal Catholic subjects versus people’s own desires to preserve a reservoir of practices which have been shaped by Catholic doctrine, while also diverging from it in significant ways. I now shift the focus away from relatively independent cultural expressions in the terrain of popular religion, to explain ways that this popular religiosity interacted with the teachings of the Oaxacan Catholic Church during my research in the 1990s, a period when the repercussions of Vatican II reforms were becoming manifest throughout Latin America and in Mexico.

In Oaxaca city in the early 1990s, many local clergy displayed the “progressive” theological slant of then archbishop, Bartolomé Carrasco, who had led the Oaxacan diocese since 1975. Compared with the Vatican II-inspired manifestations of liberation theology in Latin American regions such as in Nicaragua, Brazil, and Peru, the liberationist movement in Mexico was supported by only a small portion of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, and Carrasco was among them. In rural parts of Oaxaca and in the neighbouring southern state of Chiapas, clergy and nuns inspired by Vatican II- and Medellín-inspired declarations of human rights and the model of the Church as the “People of God” worked explicitly in defense of indigenous communities, while empowering them to become “subjects of their own histories”. In the 1980s and early 1990s, with the organization the Centro Diocesano del Pastoral Indígena de Oaxaca (CEDIPIO, the Diocesan Center of the Indigenous Pastoral Plan), as its driving force, the Oaxacan archdiocese was known as a bastion of liberation theology, both in its teachings and practice. In addition, founded in 1969, the seminary of the South Pacific (Pacifico sur) region, SERESURE, nearby in Tehuacán, Puebla, was a key liberationist training ground. Here, seminarians received courses in the social sciences in addition to the customary traditional systematic theology. They were also afforded hands-on practical pastoral experience in rural indigenous communities to prepare them for the challenge of working with the huge and diverse indigenous populations in the region in the course of working toward an “integral evangelization”.

Lending more urgency to such efforts was the Mexican government’s gradual implementation through the 1980s of neoliberal social and economic programs which had engendered worsening exclusions of rural indigenous populations in Mexico (Norget 1997), particularly in the south. Further south, in the state of Chiapas, and led for some forty years (1959–1999) by renowned liberationist bishop Samuel Ruiz, liberation theology dovetailed with an arguably more radical program for conscienticización (Freirean consciousness-raising) and mobilization of indigenous communities (see Leyva Solano 1995; Kovic 2005). However, in parallel, in rural communities throughout Oaxaca too, clergy had organized robust projects on electoral education, “language rescue”, and human rights, among others (Norget 1997, 2004). The project of the Pastoral indígena, or Indigenous Pastoral, advocated for the direct immersion of Church representatives in the realities of the communities, and the creation of a Popular Church pressuring for social justice (Norget 2004). Importantly, the communal infrastructure of the indigenous community—the roots of which were explained above—instead of the liberationist ideal of the Christian base community, was the privileged focus of consciousness-raising and organizing efforts. Additionally, the ideal of inculturation proposed a program for incarnating the Christian gospel in the community as well as making relations between Church agents and indigenous peoples more open and less hierarchical.11 In the philosophy of Indigenous Theology, the Church calls for the incorporation and reinvigoration of local traditions and culture within a revised Catholic doctrine, liturgy, and pastoral activities in indigenous communities (Norget 2004).

In Oaxaca city, the more general movement for pastoral reform was referred to as the New Evangelization (Nueva Evangelización). This campaign originated in the early 1980s, following Vatican II’s call for an updating (aggiornamento) of practice, doctrine, and global presence and the active “re-missionization” or, echoing the language of evangelical Christian churches, conversion of Catholics by both clergy and lay Catholics. As I came to know it at the start of the 1990s, the movement in the city took the form of applying, in clergy’s pastoral care to the city’s roughly 27 parishes, a diluted version of liberation theological principles. While it was not as consolidated as was the Pastoral Indígena in certain parishes in the countryside, it bore many of its guiding precepts. Hence, despite the arrival of a conservative archbishop to Oaxaca at the end of Carrasco’s term in 1991, most priests I knew or interviewed during my research—some of whom had been trained at SERESURE— agreed in principle with then tenets of the Option for the Poor and the “People’s Church” (Iglesia Popular). Many discussed popular religious forms as being necessary for a productive dialogue or “reciprocal evangelization” between clergy and poor, indigenous classes.

The Latin American hierarchy’s anxieties over the seeming never-ending tide of Catholics “lost” to evangelical Protestant Christianities inform some of the New Evangelization’s ethos, in an apparent concern to transform a passive, taken-for-granted religious identity into a conscious and active one. In Oaxaca city, for example, the New Evangelization campaign seemed to have appropriated certain aspects of the charismatic proselytizing style of evangelical sects: it stressed an abrupt “change of life” (cambio de vida) and the abandonment of ideas and vices standing in the way of the individual’s spiritual and social development, and self-realization. A sense of renewal percolated through the discourse of the New Evangelization, which I heard in Bible study groups, mass, in other church-sponsored events, and replicated on written materials distributed in masses and at other Church events. The discourse invested in Catholics an “apostolic mission”, aiming to strengthen their faith through a more profound and rigorous knowledge of Catholic doctrine. This deepening engagement was likened to a “conversion” (conversión) by Catholics within their own faith, realizable through the rejection of certain aspects of popular religious practice and a greater degree of biblical and doctrinal literacy and understanding.

Along these lines, expressions of the New Evangelization in Oaxaca city were aimed at “purifying” components of popular religion which were seen to reflect a misinterpretation and/or misuse of Catholic symbols and doctrines. As Andrew Orta has observed, liberationist theology contains an implicit critique of the “excesses” of forms of piety stemming from the colonial period as part of a suspicion of indigenous, syncretic (popular) religiosity as representing an imperfect or inauthentic Christianization (Orta 2016, p. 594; see also Napolitano 2016). Thus, examples of “corruptions of faith” raised by church proponents of the New Evangelization in Oaxaca were drunkenness during church fiestas and ceremonials, the use of confession to divulge the sins of other people, and lavish overspending on mayordomías (saints’ day festivals), baptisms and weddings—those celebrations known to be important arenas for intense competition for prestige. Clergy and deacons repeatedly stressed a more literal application of formal doctrine to everyday existence: faith was represented as ideally being a conscious (consciente) aspect of one’s everyday activity, exemplified by the encouragement of participation in Bible Study groups.

Other popular practices that the progressive Church was concerned to re-orient were those of an independent nature which took place outside the Church’s purview. The cult of the saints and other religious practices centred on domestic liturgies, for example, posed a threat to the centralization of spiritual teachings and devotions, and were therefore regarded as most susceptible to “irregularities” in interpretation and action. The Marian (i.e., Virgin Mary-centered) character of fervent popular devotion especially, and certain devotions to the saints—such as elaborate dressing of saints on home altars, for example—were firmly disapproved of by both some priests I spoke with and more orthodox or “evangelized” Catholics. In Bible meetings and in interviews with clergy, I heard people accused of being overly “idolatrous”, of indulging in “paganism” (a charge which carries condescending connotations of ignorance and backwardness associated with indigenous identity), and of failing to acknowledge that the various Virgins and “Señores” were simply distinct refractions of the Virgin Mary and Christ rather than distinct personages.

Reynaldo, a lay Catholic deacon who had attended many Church workshop events in and around the city regarding bishop Carrasco’s pastoral plan, commented on the thrust of the campaign thus:

Popular religiosity is the people’s religion (religion del pueblo)—processions (calendas), mayordomías—they are all expressions of the people, ways that the people have expressed their love of the true God (Dios Verdadero). However, some things have infiltrated or taken over that religiosity that are contrary to that faith: vices such as getting drunk, things that people shouldn’t do, have come to deform that popular religiosity. So, the Church has tried, through our pastoral plan, to purify those customs.

Similarly, Padre Daniel, a priest heading a city parish, explained,

We don’t accept anything that runs contrary to the gospel; we offer an explanation. That which is negative or offensive, that which goes against human dignity, or human rights, or the well-being of the family. […] Such as when in our religious fiestas you see things that are more commercial: cockfights and so on. The church must show that it’s bad, that it’s immoral that these elements become part of religious celebrations.

Significantly, points of conflict between popular religiosity and the “renewed” Catholic campaign were often translated in conceptual terms as a debate between “tradition”—in its most negative sense—and “progress.”14 Some of the overtly liberationist priests in Oaxaca I have known, working in both rural and urban places, a few of them from indigenous communities themselves, celebrate and encourage elements of popular tradition and the ideals of inculturation. Some clergy expressed pride in an apparently growing concern of clergy to know more about significance of symbolic components of local indigenous rites—what Padre Daniel called the “New Christian Anthropology” (Nueva Antropología Cristiana). Yet other clergy and lay people involved in New Evangelization efforts, even while appearing to support a progressive pastoral praxis, highlighted the problems of popular religious practices as rooted precisely in their indigenous origins. Hence during my interviews such practices were associated with a “naïve,” “ignorant” lifeway “del campo” (from the countryside) that was an impediment to getting ahead (seguir adelante).

In keeping with the rational, modernist tone of the campaign, Padre Claudio15, the priest attending to the local parish where I was living (late 1989 to mid-1991) stated to me, for example, that popular religion was “very good”; he acknowledged it as “an expression of faith, though not very clear nor profound.” Popular religion, in Padre Claudio’s opinion, “should be conserved, but also should continue to be renewed, and interpreted with more consciousness” (Norget 2006).

The local parish’s pastoral program (attending to some 15,000 inhabitants) appeared to rest on the assumption that such undesirable aspects of popular religiosity could be combatted with a more concerted effort to be a consciously committed Catholic, using possibilities offered in church and non-church spaces to engage in “evangelizing” activities aimed at deepening people’s active participation, and their understanding of the Bible and the significance of scripture. For example, lay people were encouraged to take part in reading homilies during mass and in other ceremonies. On occasion, such efforts made their way into the novenario prayer gatherings described earlier. For example, Carolina, an older woman in the colonia who was very involved in the deacon’s re-catechizing efforts within the New Evangelization campaign, used periods between rosary sessions on one novenario evening I attended to initiate discussions on the content of the passage of the Bible read during the prayer session. In these conversations, the difunto’s death at the time was related, in a direct and simple way, to scriptural teachings on death and sacrifice—not altogether differently from a priest’s sermon at a funeral mass. These interventions were aimed, seemingly, at swaying people towards recognizing the “true”, “proper” Catholic theological understanding of death’s significance. Yet in my experience, no one present at the prayer evening ever raised any objections to these reflections; they seemed to contribute to the calm solemnity of the occasion rather than detracting in any fashion from the character of these events.

In the celebration of the Day of the Dead, the confrontation between “official” and popular religiosities was similarly subtle. While I never witnessed any efforts by Church representatives to expunge “unacceptable” aspects of popular practice from people’s celebration of the festival, a significant divergence in orientation motivated church efforts to redefine the fiesta’s underlying rationale. The private, domestic-oriented aspect of the celebration of the fiesta centres on the building of elaborate household altars and the making of ofrendas to individual difuntos. In this it runs counter to official Catholic teachings which emphasize the (church) altar as the material site for devotion to God and/or the saints—not the ordinary dead—and in almost all significant ritual contexts emphasize the need for a cleric to act as a mediator with the sacred domain. The discourse of church representatives shifted attention away from popular, domestic religious activities by focusing the celebration of the Día de los Muertos on the veneration of the total corpus of souls. Thus, the Church held special masses proclaiming the significance of Christ’s death to all people (similar to the funeral masses that preceded a difunto’s burial). A small handout distributed to those gathered in the colonia’s church at one mass on 2 November to commemorate los fieles difuntos (the faithful dead), referred to the date as the Fiesta de Resurrección (Feast of Resurrection). In 1990, in the cemetery close to the colonia where I lived, I saw placards with biblical citations referencing the promise of the resurrection of the dead at Christ’s Second Coming fastened to the trees, announcing a mass that was held in the graveyard that afternoon. One church placard, suggestive of the progressive tone of the New Evangelization movement, made use of the language of St. Paul to proclaim: “While there is injustice, while there is suffering, we are dead to God—to Jesus!” And throughout the day, deacon Reynaldo and Padre Claudio tried to maintain a conspicuous official presence, offering responsory prayers at particular gravesites throughout the afternoon. Other church groups, including Catholic youth groups, mingled in cemeteries and also offered prayers for the families of the dead.

Such activities were not only about re-centering the church in the lives of the faithful, or displacing popular religious activities. At its most the basic, the Church seemed to seek to connect with beliefs that were congruent with a crucial aspect of “popular” theology. Such a convergence is perhaps most clearly expressed in relation to the celebration of Easter or Holy Week (Semana Santa), the most important week on the official religious calendar. The Church emphasizes the link between the concept of mortal death and Christ’s Passion during the Day of the Dead, a link that is emotive yet still somewhat abstract. Popular religion, however, focuses upon recognition of both specific individual difunto/as and the entire community of dead souls. At the beginning of the 1990s, when the New Evangelization campaign was fully underway, Church representatives in Oaxaca city made efforts to temper or sway the singular popular fixation on death by promoting Easter as a time for the spiritual rejuvenation of all members of the church community. The intention was to identify Christ’s Passion and self-sacrifice with the regeneration of the community as a social and moral whole. The additional effort by official Church representatives to add a reflection on the entire community of souls of the dead and of the saints to Easter activities, was an apparent move to deepen the theological scope of the Day of the Dead, and to defuse the intensity of the popular, household-centred focus of devotional practices.

The Church-defined significance of death as linked to communal renewal and the remembrance of the dead marked an important point of commensurability—a meeting of understandings within divergent ontological perspectives—with popular Catholic attitudes towards death on display in the novenario and the Day of the Dead.16 With their sensuous, family and community-centered, material practices, the principles organizing these celebrations were also importantly different: they made concrete demands on individuals; they compelled particular acts of respect to individual, known relatives and ancestors. These rites also put into circulation and reciprocal exchange specific objects, stories, and affect within the framework of close community ties in ways that church activities and efforts simply did not.

6. Conclusions

Oaxacan popular-indigenous Catholicism is comprised of a heterogenous blending of traditional indigenous sensibilities with those of more orthodox Catholicism over more than five centuries. Even in the urban context, the aesthetic texture of popular religiosity reflects an ethics and logic that is, in important ways, quite at odds with the teachings or activities of the official church. At the same time, areas of articulation and overlap—even if these are irregular or intermittent—unavoidably remain: the majority of Oaxacan Catholics attend mass, even if only occasionally, seek out priests to confess or deliver other sacraments, or to officialize compadrazgo relationships. Additionally, as is the case of contemporary church evangelization efforts, they might even be drawn into church activities and begin to internalize a somewhat different sense of Catholic identity.

An ethnographic approach allows for attention to the phenomenology of religion as it unfolds in people’s experience in space and time, and as embedded in a broader social and cultural context. Through such a lens, the aesthetic sense or material logic of Oaxacan popular-indigenous religiosity becomes apparent particularly in the ritualization of death; here a complex of unofficial rituals related to, or derived in part from the practices of the Catholic Church, is sustained with little or no involvement of church representatives, and in domestic or other spaces quite separate from those controlled by the Church. As celebrated by the vast majority of Oaxacans, poor and of indigenous origin, these concrete events incarnate a distinct and sensuous social vision, with strong familial and communal ties and an economy of sacrifice and reciprocity. The independent quality of local popular Catholicism derives from an embeddedness of religiosity in quotidian existence: popular religious practices are woven into the most important communal gatherings and celebrations; they are present in everyday settings such as domestic altars and public streets, and in special festivals that punctuate the cycle of seasons or, as with the Day of the Dead, create sites of memory and filial duty. These relationships are deeply personal and satisfyingly lavish; they entangle anticipations, affects, tastes, and scents in many domains of everyday life.

Understanding Catholicism as produced from the ongoing interaction of devotees and Church representatives affords a more complete understanding of Catholicism “as lived”. I have offered an ethnographic glimpse into a moment where the Vatican II-inspired New Evangelization was put into practice in the particular setting of Oaxaca. This throws into relief the provisional, mediated nature of Church pastoral efforts as theology “hits the ground” in its meeting with Catholics’ own approaches to and practices of devotion. As we saw, the discourse of the New Evangelization movement in Oaxaca privileged the officially-sanctioned meanings of certain rites and practices over the inherent plasticity, immediacy, openly sensuousness, and non-systematized nature of ritual performance. In the 1990s, the Oaxacan forms of the New Evangelization attempted to make an appeal to individual freedom and progress through rationality, knowledge (conciencia) and self-determination. They also aimed at tempering inflections of indigenous culture associated with aspects of quintessentially popular and independent practices and customs, including the fervour of devotion to the saints and to the dead. Such efforts to mitigate the “illiteracy” in Catholics’ knowledge thus often echoed condescending critiques of indigenous identity in dominant cultural discourse in Mexico more broadly. My research observations and personal experience in Oaxaca since the initial fieldwork on which this article is based confirm that the rites I have described here and, I suggest, the motivations behind them, are still ongoing.

In Oaxaca, the Church’s concept of “popular religion” troubles commonplace ideas of what it means to be Catholic as a lived identity. The weighting of church New Evangelization discourse with enlightened “modern” concerns which demand a reflective knowledge of Catholic faith, for example, overlooked the kinds of agency and creativity suffusing popular piety. Expressions of a withdrawing self-reliance—heard in people’s statements such as “I’m Catholic, but in my own way”, or seen in the local church’s evident failure to attract many local Catholics to its evangelical activities—were responses to its efforts to define proper Catholic practice within the New Evangelization campaign. These expressions also attest to the self-defined pragmatics of popular religiosity, which implicitly challenge any Church attempts to control or domesticate expressions of faith through the imposition of official doctrinal interpretations. In these terms, popular-indigenous rituals can be seen to enact a form of meaning that exceeds the “commensurability, legibility, and fixity of Christian meaning” (Orta 2006, p. 180).

The inherent responsiveness and flexibility in Oaxacan popular Catholicism means that the survival of many of its practices does not depend on the institutional Church. This is unlike official theologies or pastoral practice, which are subject to the disciplinary power of Rome, as mediated by national and regional ecclesiastical hierarchies. While the New Evangelization progressivist agenda in Oaxaca and Pastoral Indígena were alive and well in the late 1970s and 1980s, the beginning of 1990s saw the liberationist tone in Oaxaca begin to erode and, one by one, liberationist bishops—as was the case with Carrasco—were replaced by conservatives more favoured by Rome (Norget 2004). The liberationist seminary SERESURE was closed in 1990. In the end, although a handful of Oaxacan clergy and nuns sustained programs of inculturation in indigenous communities, support for such initiatives gradually waned, as did the coherence of the pastoral programs in the Oaxacan diocese more broadly. While today some priests in Oaxaca continue to implement aspects of progressive Catholicism and the Popular Church, such efforts are fragmented and partial, reliant as they were on the moral and material support of the hierarchy.

The example of Oaxacan popular religion shows that we cannot assume a seamless connection between theologies and the changes they are predicted to engender within local Catholicisms. In places at the peripheries of a Rome-centred Catholic regime, such as Oaxaca, renewal movements such as the New Evangelization inevitably must contend with vibrant local popular religiosities that, despite the presence of the Church, have become integrated over centuries and in profound ways into everyday lifeworlds. While such local Catholicisms can pose a challenge to the Church, they also revitalize Catholicism through the masses of devotees who sustain them.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Société et Culture (FRQSC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of McGill University (1995).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For example, see the Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy. http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccdds/documents/rc_con_ccdds_doc_20020513_vers-direttorio_en.html (accessed on 11 January 2021) |

| 2 | William Christian (2006) underlines Catholicism’s inherently “local” condition in reference to the Church’s traditional practice of tolerating local practice and interpretation as long as it is not directly heretical. |

| 3 | (INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia) 2020). This figure is based on the number of indigenous language speakers. The largest indigenous groups in the state are Zapotecs and Mixtecs; there are also Triquis, Chinantecs, Chontales, Mixes, Chatinos, Mazotecs, Chochos, Cuicatecs, Huaves, Zoques or Tacuates, Ixcatecs, Amuzgos and Nahuas. There is also a small Afro-descendant population originating from the slave trade in the 16th century. |

| 4 | Next to its southern neighbour state Chiapas, Oaxaca has the highest number of non-Catholics in the country, or approximately 30% of the state’s population. |

| 5 | Mestizo, literally “mixed race” (i.e., Spanish and indigenous) is the national “default” identity of most Mexicans, yet the nationalist narrative of mestizaje is based on a homogenizing racial logic (Moreno Figueroa 2010). |

| 6 | Pope Paul VI’s (1975) encyclical Evangelii Nuntiandi, for example, stressed concepts of culture and “popular religiosity”, and popular religion emerged as a prominent theme at CELAM in Medellín in 1968; here popular religion was of interest as a platform for consciousness-raising toward a profound social and political transformation of Latin America. For a thorough and insightful examination of the theorization of popular religion in varieties of Latin American liberation theology, see Bellemare (2008). |

| 7 | Following the practice of historians, I employ the term used as a juridical and legal label during the colonial period to designate the autochthonous inhabitants of the New World. |

| 8 | A Oaxacan priest told me that Oaxaca remains one of the few places in Mexico where the custom of the Misa del Cuerpo Presente is still practiced. This funerary mass stands in contrast to what is more widely observed, a requiem mass, said following a burial, when the body is no longer present. |

| 9 | See Ryan (2016) for a thoughtful contemplation on popular Catholic death rites in rural Ireland in the 1970s and 1980s, which are similarly part of a rich local intimacy with death and of deep communal significance. |

| 10 | See (Norget 2006, pp. 97–98) for the words to this prayer. |

| 11 | In formal terms, inculturation denotes “the process of adapting (without compromise) the Gospel and the Christian life to an individual [non-Christian] culture” McBrien (1994, p. 1242), which pointed to the Church’s desires for a more dialogic interaction with “Other” cultural communities in the context of evangelization and missionization. For an insightful anthropological examination of the genealogy of the concept in Catholic theology, see also Orta (2016). |

| 12 | Interview with Deacon Reynaldo S, 14 March 1990, Oaxaca de Juárez. |

| 13 | Interview with Padre Daniel R, February 1991, Oaxaca de Juárez. |

| 14 | See also (Napolitano 1998). |

| 15 | A pseudonym, as are all other proper names mentioned, unless accompanied by a surname. |

| 16 | Following anthropologist Marilyn Strathern, De la Cadena states that “partial connections” are represented in an encounter between parties of different world views (“onto-epistemic worlds”) whose knowledge practices both contain (overlap) but also exceed each other simultaneously (De la Cadena 2015). I use this concept to acknowledge the commensurability of liberationist or other “progressive” Vatican II-inspired praxes and popular religion in terms of their focus on the interests of poor and marginalized social sectors, despite the disconnections of personal backgrounds, language and worlds of experience of indigenous persons and Church. |

References

- Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barabas, Alicia. 2006. Dones, Dueños y Santos. México City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Miguel Angel Porrua. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare, Mario. 2008. The Feast of the Uninvited: Popular Religion, Liberation, Hybridity. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Theology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell, Fanella. 2006. Introduction. In The Anthropology of Christianity. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Carmagnani, Marcelo. 1988. El Regreso de los Dioses. México City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, William. 2006. Catholicisms. In Local Religion in Colonial Mexico. Edited by Martin Austin Nesvig. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 259–68. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cadena, Marisol. 2015. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García Canclini, Néstor. 1989. Culturas Híbridas. Estrategias Para Entrar y Salir de la Modernidad. México City: Grijalbo. [Google Scholar]

- Gillow, Eulogio G. 1978. Apuntes Históricos Sobre la Introducción del Cristianismo en la Diócesis de Oaxaca. Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlaganstaltung. First published in 1880. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzinski, Serge. 2001. Images at War. Translated by Heather MacLean. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, David. 1998. Introduction. In Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. vii–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia). 2020. Censo de Población y Vivienda. Oaxaca: INEGI, Available online: https://inegi.org.mx/app/saladeprensa/noticia.html?id=6265 (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Kovic, Christine. 2005. Mayan Voices for Human Rights: Displaced Catholics in Highland Chiapas. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamrani, Myriam. 2018. From the Saints to the State: Modes of Intimate Devotion to Saintly Images in Oaxaca, Mexico. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Anthropology, University College London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva Solano, Xóchitl. 1995. Militancia político-religiosa e identidad en la Lacandona. Espiral 1: 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayblin, Maya, Kristin Norget, and Valentina Napolitano. 2017. Introduction. In The Anthropology of Catholicism: A Reader. Edited by Kristin Norget, Valentina Napolitano and Maya Mayblin. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- McBrien, Richard P. 1994. Catholicism. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, Kathleen M. 2019. Protestantism and State Formation in Postrevolutionary Oaxaca. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2000. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, J. Michelle. 2017. Fluid indigeneity: Indians, Catholicism, and Spanish law in the mutable Americas. The Immanent Frame. Available online: https://tif.ssrc.org/2017/07/12/fluid-indigeneity/ (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Moreno Figueroa, Mónica G. 2010. Distributed Intensities: Whiteness, mestizaje and the logics of Mexican racism. Ethnicities 10: 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münch Galindo, Guido. 1982. La Religiosidad Indígena en el Obispado de Oaxaca Durante la Colonia y sus Proyecciones Actuals, Anales de Antropología. México City: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM, pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano, Valentina. 1998. Between ‘traditional’ and ‘new’ Catholic church religious discourses in urban Western Mexico. Bulletin of Latin American Research 17: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, Valentina. 2016. Migrant Hearts and the Atlantic Return. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norget, Kristin. 1997. The Politics of ‘Liberation’: The Popular Church, Indigenous Theology and Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca, Mexico. Latin American Perspectives 24: 96–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norget, Kristin. 2004. ‘Knowing Where We Enter’: Indigenous Theology and the Catholic Church in Oaxaca, México. In Resurgent Voices in Latin America: Indigenous Peoples, Political Mobilization, and Religious Change. Edited by Edward Cleary and Tim Steigenga. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 154–86. [Google Scholar]

- Norget, Kristin. 2006. Days of Death, Days of Life: Ritual in the Popular Culture of Oaxaca. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norget, Kristin. 2008. Hard Habits to Baroque: Catholic Church and Popular-Indigenous Religious Dialogue in Oaxaca, Mexico. Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos 33: 131–58. [Google Scholar]

- Norget, Kristin. 2010. A Cacophony of Autochthony: Representing Indigeneity in Oaxacan Popular Mobilization. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 15: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norget, Kristin. 2011. Pope. Saints, Beato Bones and other Images at War: Religious Mediation and the Translocal Roman Catholic Church, Postscripts 5: 337–64. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, Robert A. 1985. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orta, A. 2006. Catechizing Culture: Missionaries, Aymara, and the ‘New Evangelization’. New York: University of Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orta, Andrew. 2016. Inculturation theology and the ‘New Evangelization’. In The Cambridge History of Religions in Latin America. Edited by Victoria Garrard-Burnett, Paul Freston and Stephen C. Dove. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 591–602. [Google Scholar]

- Paul VI. 1975. Encyclical Letter. Evangelii Nuntiandi. December 8. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_p-vi_exh_19751208_evangelii-nuntiandi.html (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Rowe, William, and Vivian Schelling. 1991. Memory and Modernity: Popular Culture in Latin America. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Salvador. 2016. Death in an Irish Village—The resilience of ritual. The Furrow 67: 618–22. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, William. 2016. Theater of a Thousand Wonders. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Terraciano, Kevin. 2001. The Mixtecs of Colonial Oaxaca. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitecotton, Joseph. 1977. The Zapotecs: Princes, Priests and Peasants. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).