Abstract

Although spirituality has been considered a protective factor against shopping addiction, the mechanisms involved in this relationship are still poorly recognized. The present study aims to test the association of daily spiritual experiences, self-efficacy, and gender with shopping addiction. The sample consisted of 430 young adults (275 women and 155 men), with a mean age of 20.44 (SD = 1.70). The Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale, the General Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale were used to measure the study variables. The results showed that: (1) Daily spiritual experiences had a direct negative effect on shopping addiction; (2) daily spiritual experiences were positively related to self-efficacy, thought the effect was moderated by gender; (3) self-efficacy negatively correlated with a shopping addiction; and (4) the indirect effect of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction through self-efficacy was significant for women but insignificant for men. The findings confirm that spirituality protects young adults against developing a shopping addiction. They also suggest that when introducing spiritual issues into shopping addiction prevention or treatment programs, the gender-specific effects of spirituality on shopping addiction via self-efficacy should be considered to adequately utilize young women’s and men’s spiritual resources.

1. Introduction

1.1. An Overview of Shopping Addiction

For most people, shopping is a routine part of everyday activities, a way of getting necessary goods. In the modern consumerist culture, shopping also fulfills recreational functions, providing pleasure, amusement, and enjoyment, and being a rewarding behavior in itself (Ko et al. 2020; Maraz et al. 2015). However, for some people, shopping takes the form of chronic, excessive, and repetitive purchasing that temporarily brings in euphoria or provides relief from negative emotions (Clark and Calleja 2008; Miltenberger et al. 2003), but as a long-term activity, it may lead to adverse consequences (Müller et al. 2015; Weinstein et al. 2016). People who buy compulsively regularly spend much more time shopping than they intended and often purchase items they hardly need and cannot afford (Ridgway et al. 2008). Typically, after excessive buying, they feel remorseful and guilty that they succumbed to their urges (Clark and Calleja 2008). Their focus and excitement are not on the possession of the purchased goods or their usage but on the buying process itself (Lejoyeux and Weinstein 2010).

Initially, the problem of compulsive shopping was associated with people living in rich, capitalist countries of the West. As a result of progressing globalization and political and socio-economic transformations (such as system transition in the former Eastern Bloc), the phenomenon of compulsive buying is nowadays observed in Central and Eastern Europe, as well (Belk 2015; Tarka 2020). At the beginning of the free-market era, Poles were fascinated by the abundance and variety of consumer goods after the period of shortages characteristic of a centrally planned economy. Material goods, which they often purchased in excess, were not only an indicator of luxury but also served as a source of social approval or exclusion (Tarka and Babaev 2020). Socialized this way, the young generation of Polish consumers may be inclined to buy goods they do not need but confirm their belonging to a certain group and thus improve their self-esteem and mood (Adamczyk 2018; Niesiobędzka 2010; see also Islam et al. 2018).

A meta-analysis of 40 studies estimated a pooled prevalence of 4.9% for compulsive buying in representative adult samples, with a higher ratio (8.3%) noted, among other groups, for university students (Maraz et al. 2015). In Poland, about 3–4.4% of adults may have a compulsive buying problem (Adamczyk 2018; Adamczyk et al. 2020; Centre for Public Opinion Research 2019). Despite its relatively high prevalence in modern societies, compulsive buying is not categorized as a distinct mental health disorder in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2013) and the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organization 2020), due to definitional ambiguity and insufficient evidence to establish diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, over the past three decades, compulsive buying has attracted growing interest in research communities, among therapists, and in the media (Dittmar 2005).

There has been an ongoing debate about the nature of compulsive buying and whether it should be conceptualized as impulsive behavior, compulsive behavior, or behavioral addiction (Aboujaoude 2014; Lejoyeux and Weinstein 2010). According to Andreassen (2014), compulsive buying is best understood from an addiction perspective. In line with this view, several authors have argued that compulsive buying could be conceptually considered as a type of behavioral addiction since it contains the core components of addiction: salience (including cravings), withdrawal, mood modification, tolerance, problems, and relapse (Aboujaoude 2014; Clark and Calleja 2008; Weinstein et al. 2016). Shopping addiction co-occurs with a variety of other mental health disorders and addictions such as mood and anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse disorders, impulse control disorders, and personality disorders (Maraz et al. 2015; Mueller et al. 2010). Moreover, research has shown similarities between behavioral addictions (including shopping addiction) and substance addictions in terms of neurobiological features and family history/genetics (Leeman and Potenza 2013; Raab et al. 2011). Parallels also exist between sociodemographic and family- and peer-related correlates of these two types of addictions (Griffiths 1996; Shaffer et al. 2004). In addition, engaging in excessive buying, similarly to other addictions, is linked to negative and harmful consequences such as financial or legal problems, debts, personal distress, decreased quality of life, marital and family conflicts, and social isolation (Achtziger et al. 2015; Black 2007; Dittmar 2005; Weinstein et al. 2016). In the current study, consistent with the above theoretical and empirical premises, we considered compulsive buying to be a potential behavioral addiction, and thus we prefer to use the term “shopping addiction” over other names that have been given to this problem (see, e.g., Andreassen et al. 2015).

Most studies have shown that shopping addiction is more prevalent in women (Black 2007; Dittmar 2005; Otero-López and Villardefrancos 2014; Ridgway et al. 2008). However, some evidence also exists that women and men may be affected to the same extent (Koran et al. 2006; Villella et al. 2011). Younger respondents are typically more susceptible to shopping addictions than older respondents (Adamczyk et al. 2020; Dittmar 2005; Koran et al. 2006). Several studies have found that the age onset of shopping addiction is in the late teens or early 20s (see, e.g., Dittmar 2005; Islam et al. 2018; Koran et al. 2002), though McElroy et al. (1994) noted a mean age of 30. Other risk factors for shopping addiction include extraversion, neuroticism, a materialistic orientation, stress, depression, social anxiety, low self-esteem, low self-control, reduced self-efficacy, avoidance coping, and wishful thinking (Adamczyk et al. 2020; Andreassen et al. 2015; Koh et al. 2020; Lejoyeux and Weinstein 2010; Otero-López et al. 2021; Uzarska et al. 2019b). The current study is grounded in positive psychology, in which one of the crucial tenets is to seek the protective factors for undesired behaviors before they develop into serious mental problems (Gable and Haidt 2005). We focus on two protective factors, namely, spirituality and self-efficacy, whose beneficial roles in preventing unhealthy and hazardous behaviors have been well supported (see, e.g., Cook 2004; Kadden and Litt 2011; Odaci 2011). The main purpose of the present study is to examine whether there are direct and indirect effects (via self-efficacy) of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction. We also aim to test whether the indirect effect is further conditional on gender.

1.2. Spirituality

Despite definitional difficulties, spirituality can be defined as focusing on the ultimate questions about life’s meaning and seeking significance in the connectedness with oneself, other people, nature, or the sacred (Cook 2004; Puchalski and Guenther 2012). It can be viewed as a universal human experience since most people acknowledge a spiritual aspect of their lives and seek transcendence (Bandura 2003; de Jager Meezenbroek et al. 2012). It is connected with the belief that there are aspects of human life that go beyond physical reality and that life cannot be fully understood (Cook 2004).

In this study, we follow the assumption that spirituality and religiosity are neither identical nor mutually exclusive constructs; they may coexist in a person, share some common areas, or exist separately (Astrow et al. 2001; Saucier and Skrzypińska 2006). In some people, spirituality will be expressed through belonging to a certain faith and related institutions, and following specific public and private religious practices and rituals (Oman 2013). By contrast, an individual can adopt the outward, instrumental forms of religious practices and perform them habitually or mainly for their psychological and social benefits, without establishing a profound relationship to the transcendent (Cook 2004). Furthermore, spirituality does not have to be linked to belief in God or any other higher power, not even with practicing religion; it is an internal, personal, subjective, and private experience that can be present at all levels of religiosity (Reutter and Bigatti 2014). Apart from a relationship with God or another force beyond human knowledge and existence, spirituality may lie in close contact with nature, the will to help others for the benefit of humanity, feeling a part of shared experience with other people and the universe, perceiving the meaning and significance of the surrounding world, or looking for one’s authenticity and completeness (Choi et al. 2020; Fisher 2011).

The current study relates to daily spiritual experiences, which are defined as “a person’s perception of the transcendent (God, the divine) in daily life and his or her perception of his or her interaction with or involvement of the transcendent in life” (Underwood and Teresi 2002, p. 23). In the context of the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (Underwood and Teresi 2002), which was developed to measure ordinary spiritual experiences, the word “spirituality” refers to aspects of personal life that include the transcendent, divine, or holy, “something more” than what a person can perceive with their senses (Underwood 2011). Such a conceptualization of spirituality makes it possible to transcend the boundaries of any particular religion and investigate the expression of spiritual feelings and inner experiences in everyday life.

1.3. Spirituality and Shopping Addiction

Previous studies have identified religiosity and spirituality as protective factors against the development of substance and behavioral addictions (Bliss 2007; Clarke et al. 2006; Cook 2004; Grim and Grim 2019; Shim 2019). Most religions (which may serve as a conduit to transcendent experience; Oman 2013) include explicit proscriptions against risky behaviors, encourage people to work on self-control to show more resistance to urges and temptations (Carter et al. 2012), and teach about the importance of taking care of body, mind, and spirit. Believers are expected to follow these rules, and not complying with them is treated as breaking divine law.

Religious doctrines usually condemn excessive consumption, claiming that materialistic pursuits are inconsistent with living a spiritual life because they divert individuals from their spiritual duties, can prompt individuals to immoral behaviors to satisfy their material desires, and promote envy and social inequality due to an uneven distribution of goods and services (Azevedo 2020; Pace 2013). In an experimental study by Stillman et al. (2012), spirituality was found to reduce conspicuous consumption. Specifically, participants who were asked to describe a spiritual event demonstrated a lower desire to consume conspicuously than participants asked to describe an enjoyable event. Accordingly, studies have found that religiosity and spirituality are negatively related to materialism (Burroughs and Rindfleisch 2002; Pace 2013), which is one of the most salient risk factors for compulsive buying (Andreassen et al. 2015; Dittmar 2005; Harnish and Bridges 2015). Considering what has been discussed, then, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Daily spiritual experiences have a direct negative effect on shopping addiction.

1.4. Self-Efficacy

Not only may daily spiritual experiences have a direct effect on shopping addiction, but they may also affect it indirectly. In this study, we explore self-efficacy as a potential mediator of the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and shopping addiction. We decided to test the role of self-efficacy due to three reasons. First, we wanted to examine the psychological construct that is well-established in the addiction field (Kadden and Litt 2011; Odaci 2011; Yao and Zhong 2014), including literature on shopping addiction (Jiang and Shi 2016; Uzarska et al. 2019b). Self-efficacy seems perfectly suitable for this role, since it has been suggested to be a critical protective factor for the development and maintenance of shopping addiction (Jiang and Shi 2016; Koh et al. 2020). Second, we chose to investigate the role of self-efficacy as it permeates all aspects of functioning, impacting cognitive, motivational, affective, and decisional processes (Bandura 1997), potentially exerting multi-faceted influence on the buying process. Third, there is substantial evidence that spirituality is one of the sources of self-efficacy and self-efficacy has been found to mediate the relationship between spirituality and well-being and substance addictions (see below for details).

Self-efficacy is a well-researched psychological construct that Bandura introduced in his social-cognitive theory (1997). It describes an individual’s belief that they possess the social and cognitive skills to cope with adversity arising from specific demanding situations and perform the behaviors required to produce the desired outcome (Bandura 2002). Self-efficacy affects how people feel, think, act, motivate themselves, and believe in their abilities to fulfill required tasks (Bandura 2003; Schwarzer and Hallum 2008). High self-efficacy motivates people to achieve their goals with a positive attitude, due to which difficulties can be easily managed. Furthermore, people with high self-efficacy tend to treat challenges as things that can be overcome and mastered (Nguyen 2019), and thus increase their efforts when faced with difficulties. In contrast, low self-efficacy makes individuals focus on potential failure, which often leads them to avoid tasks that exceed their self-perceived abilities, to choose tasks that are easy to complete, behave ineffectively despite knowing what to do, or to abandon their attempts without arriving at a logical conclusion (Bandura 2002).

Although the original concept of self-efficacy was considered to be context-dependent and domain-specific, researchers proposed that self-efficacy may be generalized across different domains of activity (Scholz et al. 2002; Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995). General self-efficacy can be defined as an optimistic self-belief and refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to experience success across a wide range of demanding situations (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995). It reflects differences in people’s general tendency to view themselves as capable of dealing with different demands and challenges, regardless of the situation (Chen et al. 2001). Persons with high general self-efficacy are characterized by a strong motivation to action and effort, persistence, accurate assessment of their situation and ability to plan their future, stress resistance, and optimism. On the other hand, low general self-efficacy is associated with low motivation, inability to plan one’s life and to realize long-term goals, poor understanding of one’s life situation, lack of stress resistance, and pessimistic attitude towards oneself and the world (Bandura 2002; Chen et al. 2001).

1.5. Spirituality and Self-Efficacy

There is substantial empirical evidence that spirituality is positively related to self-efficacy (Abdel-Khalek and Lester 2017; Adegbola 2011; Charzyńska and Wysocka 2014; González-Rivera and Rosario-Rodríguez 2018). There are several possible mechanisms that underlie this relationship. Spirituality helps individuals understand and create positive meanings from unpleasant situations or chronic diseases (Treloar 2002). It gives people inner strength and provides spiritual guidance when facing stressful situations and uncertainties of life (de Guzman et al. 2015). Spirituality also plays an important role as a coping strategy, reduces stress, and gives comfort (Druedahl et al. 2018; Frouzandeh et al. 2015). Furthermore, spirituality is positively related to perceived social support (Hill and Pargament 2003), which is one of the sources of self-efficacy beliefs (Adler-Constantinescu et al. 2013).

Spirituality may also help some individuals gain a sense of control over their lives (Frouzandeh et al. 2015; see also Konopack and McAuley 2012), which is consistent with the modes of agency introduced in the social-cognitive theory (Bandura 2002). Specifically, when being in a situation beyond one’s control, an individual may turn to the proxy agency by enlisting others who have the means, expertise, and resources to act on their behalf to secure the desired outcomes. For religious people, God is envisioned as a proxy agent, which is a source of power, strength, and guidance. Bandura (2003) states that the effect of spirituality on self-efficacy may depend on one’s conception of divine agency. If the God–human relationship is viewed as a guiding, supportive partnership, in which a person looks toward the Supreme Being as a source of collaborative strength, it can foster a sense of personal self-efficacy (Bandura 2003; Druedahl et al. 2018).

A substantial number of studies tested simple relationships between spirituality, self-efficacy, and shopping addiction, but there are also some premises that the relationship between spirituality and shopping addiction might be mediated by self-efficacy. However, most efficacy-mediated models have been empirically tested and validated in contexts other than addictions. For instance, the study by Fatima et al. (2018) demonstrated that among adolescents and emerging adults, self-efficacy mediated the relationships between religiosity and psychological well-being, controlling for the indirect effect through perceived social support. In the study by Konopack and McAuley (2012), more spiritual individuals scored higher on self-care self-efficacy, which was associated with more positive health status; the association was stronger for mental health status than for physical health status. The study most thematically similar to the present study was carried out among the participants of substance abuse treatment in Australia (Mason et al. 2009). In this study, self-efficacy was found to mediate the relationship between spirituality and drug and/or alcohol cravings.

Based on these theoretical and empirical premises, we expected that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Daily spiritual experiences are positively related to self-efficacy.

1.6. Self-Efficacy and Shopping Addiction

The important role of self-efficacy in preventing and treating substance abuse has been noted in many studies (for a review, see Kadden and Litt 2011). A growing number of studies have also shown that high self-efficacy prevents individuals from behavioral addictions (Jeong and Kim 2011; Odaci 2011; Yao and Zhong 2014). Accordingly, it has been suggested that low self-efficacy underlies most (or even all) addictions (Uzarska et al. 2019b).

Research has shown that low self-efficacy is related to compulsive buying tendencies (Jiang and Shi 2016; Uzarska et al. 2019b). According to social cognitive theory (Bandura 2002), individuals tend to avoid tasks that exceed their self-perceived abilities. Thus, if a person considers themselves as being unable to perform the task, they may abandon a task in favor of avoiding behaviors such as compulsive buying, which is less threatening to the self and may temporarily protect them from negative emotions stemming from the perceived risk of failure (Dittmar et al. 2007; Odaci 2011). Individuals with high general self-efficacy tend to adopt positive problem-focused coping strategies, which help them to manage their behaviors and deal with their emotional states more effectively compared to persons with low general self-efficacy who are more inclined to apply negative coping strategies and engage in negative self-talk (Bandura 2002; Luszczynska et al. 2005). In this sense, compulsive buying may act as a coping response to one’s feelings of inadequacy (Jiang and Shi 2016), through which a person may achieve immediate satisfaction. These assumptions were initially supported by the results of the study conducted among 3263 college students from the US, China, and South Korea, in which self-efficacy and depressive symptoms partially mediated the relationship between life stress and compulsive buying (Koh et al. 2020).

Taking into account the above findings suggesting that low self-efficacy predisposes individuals to shopping addiction, we expected that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Self-efficacy is negatively related to shopping addiction.

1.7. Gender-Specific Effects of Daily Spiritual Experiences on Self-Efficacy

Apart from testing the relationships between daily spiritual experiences, self-efficacy, and shopping addiction, we also aim to examine whether the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy is further moderated by gender. It has been well documented that, compared to men, women are generally more religious, participate in religious ceremonious more often, pray more frequently, and declare the higher importance of religiosity and spirituality in their lives (Hammermeister et al. 2005; Robinson et al. 2019; Strawbridge et al. 2000; Zarzycka 2011). These gender differences are culture- and religion-dependent at least to some degree, being especially pronounced among Christian women and men (Schnabel 2015). Moreover, a substantial number of studies have shown that religiosity and spirituality generally bring more benefits for health and well-being for women compared to men (Kovacs et al. 2011; McCullough et al. 2000; Pérez et al. 2009; Strawbridge et al. 2000). However, it should be noticed that some studies have suggested that the moderating role of gender may be more complicated or mixed (Maselko and Kubzansky 2006; Meisenhelder 2003), being dependent on religious and spiritual dimensions, area of functioning, characteristics of the study sample, or sociocultural context.

Our expectations about the moderating effect of gender were further based upon the results of studies showing differences in God images among women and men. Women tend to perceive God in more positive ways—as supportive, nurturing, relating, and providing (Dickie et al. 2006; Nelsen et al. 1985; Nguyen and Zuckerman 2016), whereas men have been found to hold a more controlling God image and focus on God’s power and judgment and on practicing spiritual discipline (Hammersla et al. 1986; Krejci 1998; Ozorak 1996). Moreover, women pay more attention to personal aspects of spirituality, emphasizing a close relationship with a loving God and the relationship with others in a religious community (Bryant 2007; Buchko 2004). The way of defining and perceiving the transcendent and own relationship with it may influence the impact that spirituality has on one’s self-efficacy beliefs (see Francis et al. 2001). Thus, it is plausible that the more personal and close relationship with the transcendent noted among women compared to men serves as an important source for women’s perceived ability to succeed in various situations, resulting in the higher effect of spirituality on perceived self-efficacy for women than for men.

Considering all the above premises, we formulated the hypothesis assuming the moderating effect of gender:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy is moderated by gender such that the effect is stronger for women than it is for men.

Finally, combining all the expected relationships between the variables, we built a moderated mediation model:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

In the mediated relationship between daily spiritual experiences, self-efficacy, and shopping addiction, the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy is stronger for women than for men. As such, the indirect effect of spirituality on shopping addiction through self-efficacy is stronger for women than it is for men.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 430 Polish students, including 275 women (64.0%) and 155 men (36.0%). The mean age of the participants was 20.44 (SD = 1.70). Most students were doing full-time courses (n = 342; 79.5%); the remaining were doing part-time studies (n = 88; 20.5%). Students were affiliated with different faculties (i.e., social, medical, humanities, economics, mathematics, electronics, computer science, law, engineering, arts). The majority of the participants were Roman Catholics (n = 328; 76.3%). There was also a small number of believers of other religions: Protestants (n = 3; 0.7%), Buddhists (n = 2; 0.5%), Muslims (n = 2; 0.5%), one Baptist (0.2%), and one biblical Christian (0.2%). Some participants (n = 13; 3.0%) declared a belief in God or a higher power but without identifying with any particular religion. The remaining participants described themselves as atheists (n = 74; 17.2%) or agnostics (n = 6; 1.4%). Most of the participants lived with their family of origin (n = 284; 66.0%). Other students rented flats or rooms (n = 88; 20.5%), had their own flats or houses (n = 30; 7.0%), rented rooms at student dormitories (n = 26; 6.0%), or were living in orphanages (n = 2; 0.5%).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Daily Spiritual Experiences

Spirituality was measured with the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES; Underwood and Teresi 2002). The items of the DSES capture the ordinary experiences of connection with the transcendent (God, the Divine) in daily life. In the current study, we used the short, six-item version of the DSES, developed for inclusion in the General Social Survey (see Underwood 2011). Although Underwood and Teresi (2002) recommended using the full, 16-item version of the DSES, the six-item version has been found to be highly correlated with the longer one (Loustalot et al. 2006). The equivalence of the two versions was further supported by non-significant differences in the normalized mean scores (Loustalot et al. 2006). Moreover, studies have shown no evidence that the full version of the DSES outperformed the short version in predicting well-being (Ellison and Fan 2008). Importantly, several studies involving different samples have supported good psychometric properties of the short version of the DSES (e.g., Bailly and Roussiau 2010; Ellison and Fan 2008; Loustalot et al. 2006; Mofidi et al. 2006). In Polish samples, the short version of the DSES was used by Wnuk (2017; see also Wnuk 2009). This version of the DSES is unidimensional (Bailly and Roussiau 2010; Loustalot et al. 2006), which was also supported in the current study by the results of confirmatory factor analysis (CMIN/df = 2.57, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.060, 90% CI (0.026; 0.096); SRMR = 0.016).

Each item of the DSES is assessed with a six-point Likert scale (1 = “many times a day”, 2 = “every day”, 3 = “most days”, 4 = “some days”, 5 = “once in a while”, and 6 = “never or almost never”). The example item for the DSES is: “I feel deep inner peace or harmony”. To make the scores easier to interpret, the responses were reverse coded so that higher scores reflect a higher frequency of daily spiritual experiences (see Underwood 2011). The total level of daily spiritual experiences is calculated by summing up the responses to the six items. In this study, the internal consistency for DSES, measured with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, was 0.92.

2.2.2. General Self-Efficacy

General self-efficacy was measured with the Polish version (Schwarzer et al. 2011) of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE; Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995). Both the original GSE and its Polish version are one-dimensional (Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995; Schwarzer et al. 2011). The GSE consists of 10 items (e.g., “If I am in trouble, I can usually think of a solution”.) that are scored using a four-point scale (1 = “not at all true”, 2 = “hardly true”, 3 = “moderately true”, 4 = “exactly true”). Its scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-efficacy. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for GSE was 0.85.

2.2.3. Shopping Addiction

Shopping addiction was measured with the Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale (BSAS; Andreassen et al. 2015; for the Polish adaptation, see Uzarska et al. 2019a). The BSAS is unidimensional and includes seven items, one for each of the seven addiction criteria (i.e., salience, mood modification, conflict, tolerance, withdrawal, relapse, and problems). The participants are asked to rate how strongly each of the statements relates to their thoughts and behavior in the past 12 months. The example item for the BSAS is: “I shop/buy so much that it negatively affects my daily obligations (e.g., school and work)”. All items are scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “completely disagree”, 2 = “disagree”, 3 = “neither disagree nor agree”, 4 = “agree”, and 5 = “completely agree”). Higher scores indicate a higher level of shopping addiction. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the BSAS was 0.79.

2.3. Procedure

Students of three public universities in the southern part of Poland were invited during lectures and classes to participate in the study. The students were also asked to disseminate information about the study among their friends, colleagues, and family members. The participants were informed about the general aim of the study, that the study was anonymous and voluntary, and that they had the right to withdraw from the study without any consequences. They were asked to complete the questionnaires carefully and diligently, check whether all questions were answered before returning the questionnaires, and return them within 3 weeks. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

2.4. Data Analysis

In the first step of the analysis, we inspected the missing values. The percentage of missing data was very small (i.e., 0.2%). We assumed data to be missing at random (MAR), as there were no missing data patterns apparent from the analysis. To handle the missing data, we used the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977), which is included in the Missing Values Analysis module within IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp. 2019). In the preliminary analysis, we calculated descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the variables. In the next step, we assessed whether gender served as a moderator in the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy. This step was completed prior to testing the moderated mediation model to ensure that the moderating effect of gender functioned as hypothesized. To test the simple moderation model, we used Model 1 implemented in the PROCESS macro version 3.1 (Hayes 2013). Daily spiritual experiences were mean-centered, and gender was dummy-coded (0 = female, 1 = male) before creating a product term. To describe the strength of the moderating effect, we used the effect-size metric f2 (Aiken and West 1991). Effect sizes of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen 1988). However, values of f2 lower than 0.02 are common, with the median observed effect size in tests of moderation for categorical variables being around 0.002 (Aguinis et al. 2005).

Finally, we tested the moderated mediation model to evaluate whether self-efficacy mediates the association between daily spiritual experiences and shopping addiction and whether the indirect effect is further conditional on gender. To check this, in the conditional model, we entered mean-centered daily spiritual experiences as the independent variable (X), self-efficacy as the mediator (M), shopping addiction as the dependent variable (Y), and dummy-coded gender as the moderator of the relationship between X and M (W). To test this moderated mediation model, we used Model 7, implemented in the PROCESS macro version 3.1 (Hayes 2013). We used the bootstrapping method, which is widely regarded as the best available option for calculating indirect effects (Hayes 2013). The index of moderated mediation was tested with a 95% bootstrap confidence interval based on 10,000 replications. In the bootstrapping method, a confidence interval that does not contain zero shows that the effect is significant (MacKinnon et al. 2004). The size of the indirect effect was calculated as completely standardized indirect effect (abcs; Preacher and Kelley 2011). The values of abcs of 0.01, 0.09, and 0.25 are interpreted as small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Kenny 2018). All calculations were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp. 2019).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between the study variables. The mean score for shopping addiction was 11.55 (SD = 4.26). Daily spiritual experiences correlated positively with self-efficacy (p < 0.001) and negatively with shopping addiction (p = 0.009). Self-efficacy was negatively related to shopping addiction (p = 0.001). Moreover, being a man was positively related to self-efficacy (p < 0.001) and negatively to shopping addiction (p < 0.001). The relationship between gender and spirituality was insignificant (p = 0.09).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the study variables.

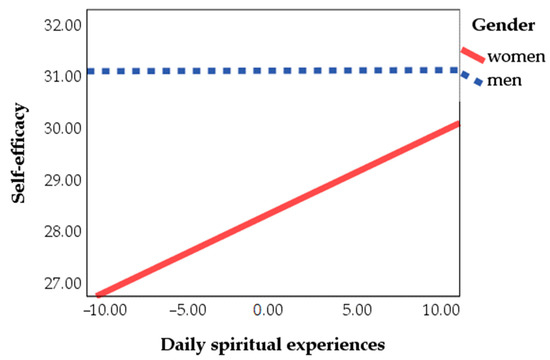

3.2. Moderation Model

Table 2 and Figure 1 present the results for the moderation model. Gender was a significant moderator of the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy. Daily spiritual experiences were positively related to self-efficacy in women (b = 0.16; p < 0.001); by contrast, in men the correlation between these variables was insignificant (b = 0.00; p = 0.98). The size of the moderating effect was 0.017 (Aiken and West 1991).

Table 2.

Regression analysis for the moderating effect of gender.

Figure 1.

Gender as a moderator between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy. Spirituality was mean-centered and gender was dummy-coded (0 = women; 1 = men). A continuous line indicates the significant relationship, whereas a dotted line was used to mark the insignificant relationship. N = 430.

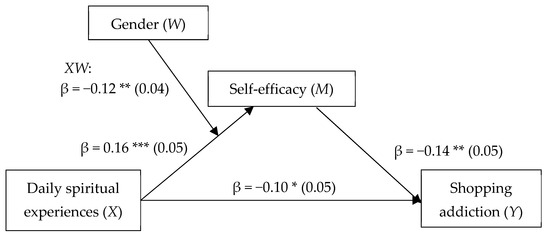

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model

The results of moderated mediation are depicted in Figure 2. Daily spiritual experiences had a direct negative effect on shopping addiction (b = −0.06; p = 0.037). Spiritual experiences were positively related to self-efficacy (b = 0.16; p < 0.001) and self-efficacy was negatively related to shopping addiction (b = −0.12; p = 0.005). Matching our simple moderation finding, gender was found to moderate the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy (b = −0.15; p = 0.007).

Figure 2.

Moderated mediation model on the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and shopping addiction. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. Standardized regression coefficients are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. X = independent variable; W = moderator; M = mediator; Y = dependent variable; XW = interaction. The value of f2 for the moderating effect is 0.017. Index of moderated mediation (standardized coefficients): 0.035 (95% CI (0.003–0.082)). Indirect effect for women (standardized coefficients): β = −0.035, 95% CI (−0.072, −0.006); abcs = −0.035. Indirect effect for men (standardized coefficients): β = 0.000, 95% CI (−0.021, 0.024). R and R2 for M: 0.346 and 0.120; R and R2 for Y: 0.184 and 0.034.

The value of the index of moderated mediation was 0.019 (95% CI (0.002; 0.047)). The confidence intervals estimated by bootstrapping did not include zero, which meant that the moderated mediation was significant. In other words, the indirect effect of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction through self-efficacy differed across genders. Specifically, the indirect effect was significant only for women (b = −0.019, 95% CI (−0.041, −0.004); abcs = −0.035). There was no evidence of a significant indirect effect for men (b = 0.000, 95% CI (−0.012, 0.013)). The results suggest that a higher level of spirituality may reduce the symptoms of shopping addiction by enhancing self-efficacy, but only among women.

4. Discussion

4.1. Direct and Indirect Effects of Daily Spiritual Experiences on Shopping Addiction

Emerging adulthood is characterized by heightened spiritual exploration (McNamara Barry et al. 2010), during which an individual poses questions about the meaning of life, their own beliefs and purposes, and discovers aspects of life that often challenge their conceptions of faith and belief (Parks 2000). Spiritual and religious beliefs play an important role in the everyday life of young adults, influencing their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Despite the important functions served by spirituality and religiosity in young adulthood, relatively little research has explored the possible protective role of spirituality against shopping addiction. The present study was conducted to fill this gap by examining the direct and indirect effects of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction among young Polish adults.

As expected, we noted the significant direct effect of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction (H1 supported). Curbing excessive consumption and materialistic desires is a common tenet for most religions (Pace 2013). In Christianity, overconsumption, materialism, and greed are decisively disapproved, being regarded as offenses against God (Adamczyk et al. 2020; Azevedo 2020). Spiritual paths often indicate the need to have a balanced attitude towards material goods, not denying their value, but at the same time emphasizing the primacy of caring for one’s spiritual development (Pace 2013). Highly self-transcendent people have been found to prioritize questions of life meaning over material possessions (Reed 2014). Accordingly, for those young adults who exhibit a high level of spirituality, caring for their inner life and raising existential questions about meaning and purpose may be so engaging that purchasing new items and goods seems less important or maybe even trivial or indecent, which protects them from developing a shopping addiction.

Consistent with previous studies, we noted the negative relationship between self-efficacy and shopping addiction (H3 supported). Excessive shopping addiction may be understood as avoidant coping induced in response to stress and unwanted feelings of inefficacy (Clark and Calleja 2008). When a difficult situation arises, individuals with low self-efficacy may resort to extensive buying as it is easily available, allowing them to redirect attention from the source of stress immediately, and help reduce negative feelings momentarily (Dittmar et al. 2007; Ridgway et al. 2008). Since self-efficacy is seen as a malleable construct, applying intervention strategies and techniques to boost its level among young adults may significantly reduce the symptoms of shopping addiction (see Hyde et al. 2008). Introducing coping programs and psychological counseling may also be helpful in improving perceived self-efficacy (see, e.g., Martinez et al. 2010) by instructing individuals on how to adopt active coping strategies such as problem solving, cognitive restructuring or social support, which have been recently suggested as protective factors against shopping addiction (Otero-López et al. 2021). In addition to coping-skills training, other possible means of enhancing self-efficacy in the contexts of shopping addiction involve cognitive-behavioral therapy and Motivational Interviewing (e.g., the “supportive self-efficacy” strategy; Miller and Rollnick 2002).

In the current study, daily spiritual experiences were positively related to self-efficacy (H2 supported). This finding is in line with previous research showing significant links between spirituality and self-efficacy. Interestingly, in the current study, the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and self-efficacy was moderated by gender, such that the effect was significant and positive for women; no significant relationship was found for men (H4 partially supported). This result suggests that daily spiritual experiences contribute to perceived self-efficacy but only in young women. Compared to men, women declare spirituality and religiosity to be more important in their lives, are more committed to integrating spirituality into their daily activities, more frequently practice spirituality on a daily basis, and more often feel assured that God is present and active in their lives (Bryant 2007; Buchko 2004; Robinson et al. 2019). Moreover, the gender-specific effect noted in this study may be rooted in differences in the perceived relationship with God and in the image of God, expressed primarily in women’s tendency to see God as supportive and nurturing (Dickie et al. 2006; Nelsen et al. 1985; Nguyen and Zuckerman 2016). This way of perceiving God and one’s relationship with God may improve the self-perceived abilities in women.

In explaining the gender differences noted, it is also important to observe that in the current study, young Polish women demonstrated significantly lower perceived self-efficacy than young Polish men. Previous research suggests that women tend to underestimate their abilities and performance, whereas men overestimate both of them (Cooper et al. 2018; Ehrlinger and Dunning 2003; Niederle and Vesterlund 2007). In view of the above, spirituality seems to be an important resource for young Polish women, which allows them to partially compensate for their deficits in perceived self-efficacy. This is in line with the theory of resource substitution (Ross and Mirowsky 2006), which states that in case of deficiency in one resource in human capacity, another resource can thrive. In light of the findings of the current study, it seems plausible to state that young Polish women compensate for their low self-efficacy with the cultivation of their spiritual experiences in everyday life.

It is also possible that the main sources of self-efficacy beliefs differ among genders. Indeed, there is some evidence that women tend to rely primarily on social factors such as social persuasion when forming their self-efficacy. For men, mastery experiences seem to be a more salient source for building self-efficacy beliefs (Butz and Usher 2015; Usher and Pajares 2006). Thus, the tendency to emphasize the relational aspects of spirituality, which is characteristic for women (Buchko 2004), may bring them more psychological benefits such as profound gains in perceived self-efficacy.

Consistent with the simple moderating effect, we found that the indirect effect of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction through self-efficacy was significant only for women (H5 partially supported). This result indicates that women utilize spirituality as a resource that enhances self-efficacy, which in turn contributes to the reduced level of shopping addiction. It also suggests that it may not be appropriate to assume that the effects of spirituality on shopping addiction are uniform for men and women. In accordance with this, some gender-dependent effects were also noted in previous studies. For instance, Ching et al. (2016) conducted a study concerning gender differences in pathways to compulsive buying among Chinese college students. The results showed that the mood compensation pathway was significant in females only; by contrast, the irrational cognitive pathway was supported for both genders. In another study, contingent self-esteem was a strong predictor of compulsive buying for both genders (Biolcati 2017). However, only for women was the relationship between contingent self-esteem and compulsive buying mediated by fear of negative evaluation. Gender differences in mediational effects warrant further investigation to inquire more deeply into the underlying mechanisms of shopping addiction.

4.2. Practical Implications

The direct relationship between spirituality and shopping addiction suggests the need to address spiritual issues when working with young adults who have a shopping addiction or those who are susceptible to developing it. This is further supported by the results of a study by Granero et al. (2016), in which low self-transcendence has been found to predict poor outcomes of a standardized, individual cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for compulsive buying behavior. The inclusion of spiritual issues can take various forms, depending on the client’s religious and spiritual beliefs, values, preferences, and willingness as well as the knowledge and experience of the counselor or therapist (Harris et al. 2016; Plante 2007; Vieten et al. 2016). Incorporating any spiritual practice into treatment should be preceded by an assessment of the client’s spiritual resources such as daily spiritual experiences (Underwood and Teresi 2002), spiritual coping (Charzyńska 2015), spiritual well-being (Paloutzian and Ellison 1982), and the perceived efficacy for learning from spiritual models (Oman et al. 2012). Exemplary spiritual methods and techniques may include making references to spiritual resources and motivating individuals to take advantage of such resources, using spiritual lifemaps, discussing spiritual beliefs, values, feelings, and meanings, or encouraging individuals to engage in spiritual practices such as meditation and yoga (Bergin and Richards 2005; Hodge 2005). Other practices potentially enhancing spirituality involve observing nature, performing arts, strengthening bonds with other people and the universe, nurturing values, and working on one’s virtues and character strengths (Charzyńska 2015; Choi et al. 2020; Fisher 2011). Although not necessarily a spiritual activity, mindfulness practice can also be introduced, taking into account some evidence of its usefulness in shopping addiction treatment (Armstrong 2012; see also Sancho et al. 2018). Further research is required to identify the most effective and most efficient spiritual strategies and interventions for shopping addiction treatment.

It should be mentioned that a client does not have to be religious or spiritual to use at least some of the spiritual practices listed above. Studies have shown that the vast majority of persons with substance use disorders would prefer spirituality topics to be more featured in treatment (Dermatis et al. 2004), regardless of their religious beliefs (see also Pargament 2011). Moreover, in many spiritual paths, material possessions are treated less restrictively and without condemnation characteristic for religions. Instead of this, spiritual approaches often appreciate material goods, but at the same time emphasize the need for temperance and reasonable use of resources (Pace 2013). This view is shared by some scholars who argue that spirituality and some forms of materialism can be tied and are not necessarily in opposition (Belk et al. 1989; O’Guinn and Belk 1989). Such a balanced approach towards material possessions may be more acceptable and easier to adapt by young persons than following strict religious rules.

The results of testing the moderation mediation model suggest that using spiritual means to increase self-efficacy may indirectly help reduce symptoms of shopping addiction in women. However, this path seems to be ineffective for men. Thus, gender-dependent mechanisms should be taken into account when developing prevention and treatment programs for shopping addiction. More specifically, for men, interventions aimed at reducing symptoms of shopping addiction by enhancing self-efficacy beliefs should be targeted at other sources of self-efficacy than spirituality.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to measure the association of daily spiritual experiences, self-efficacy, and gender with a shopping addiction. The current study comprised a relatively large sample size of young women and men. Reliable and valid psychometric instruments were used. The study substantially contributes to the research literature on the direct and indirect relationships between spirituality and addictions. Moreover, it suggests that gender-dependent mechanisms should be considered in the counseling and treatment of shopping addiction to utilize the spiritual resources of both genders most effectively.

Despite these strengths, our study has some limitations. First, the sample consisted of undergraduate students, which restricts the ability to generalize these findings to other groups. Second, although we built our model on sound theoretical premises and the findings of previous studies, which provided a basis for the hypothesized directions of the relationships between the variables, the cross-sectional nature of the current study precludes inferences about causality. Applying an experimental design to explore the effects of spirituality on shopping addiction is highly recommended. Furthermore, since spiritual experiences (Kashdan and Nezlek 2012), self-efficacy (Warner et al. 2018), and symptoms of shopping addiction (see Miltenberger et al. 2003) are not fixed characteristics of a person and may fluctuate from day to day, intensive longitudinal studies are required to explore within-person relationships between these concepts. Third, this study relied entirely on self-report measures, which may affect the quality of data to some degree. Moreover, to measure daily spiritual experiences, we used a short version of the DSES. Although this measure has good psychometric properties, it would be advisable to use the long version of the DSES to capture the wider range of spirituality scores in future studies. Additionally, since in this study we measured only general self-efficacy, it is recommended to test specific self-efficacy in shopping addiction, connected with the belief that one will be able to abstain from participating in compulsive shopping, especially in situations that trigger such behaviors (for example, when experiencing negative emotions).

When interpreting the results, it should be taken into account that the relationships between daily spiritual experiences, self-efficacy, and shopping addiction were weak, albeit significant. The size of the significant indirect effect noted for women was also relatively small (i.e., abcs = −0.035). More work is needed to replicate these findings and thus clarify their implications. In addition, although spirituality and self-efficacy seem to play a significant role in shopping addiction, other protective factors should be considered in future studies, including resilience, optimism, and hope, which—along with self-efficacy—constitute positive psychological capital (Luthans and Youssef 2004).

Finally, the study was carried out in Poland, a highly religious country, with more than 90% of Polish people describing themselves as religious, mostly Roman Catholic (Centre for Public Opinion Research 2020). Although the level of religiosity of young Polish adults has decreased significantly over recent years (Pew Research Center 2018), the percentage of believers among young Polish adults is still higher than in other European countries (Bullivant 2018). In our sample, more than 75% of young adults declared themselves Roman Catholic. Living in a religiously homogenous country may affect the impact of spirituality on people’s attitudes (Stolz et al. 2013), possibly including behaviors related to shopping and spending money. Similarly, the moderated relationship between spirituality and self-efficacy noted in the current study may depend on sociocultural factors such as religious traditions, cultural heritage, and national identity (see Smith et al. 1979). This is consistent with Bandura (1997, p. 32)’s view that “cultural values and practices affect how efficacy beliefs are developed”. Therefore, further research is needed to examine the effect of daily spiritual experiences on shopping addiction through self-efficacy in more spiritually diversified countries than Poland.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.; methodology, E.C.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, E.C.; resources, E.C., M.S.-D., E.W., and A.O.-M.; data curation, E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C., M.S.-D., E.W., and A.O.-M.; writing—review and editing, E.C., M.S.-D., E.W., and A.O.-M.; visualization, E.C.; project administration, E.C.; funding acquisition, E.C., M.S.-D., E.W., and A.O.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was covered by the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Silesia in Katowice (the Dean’s fund for interdisciplinary research teams).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures in the study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Silesia in Katowice and adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. It consisted of the following elements: the purpose of the study, a statement regarding anonymity of participants and their voluntary participation, a statement regarding the participants’ right to withdraw their consent at any time, a description of potential risks, burdens, and benefits of research, and the full name and contact details of PI.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [E.C.] upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M., and David Lester. 2017. The Association Between Religiosity, Generalized Self-Efficacy, Mental Health, and Happiness in Arab College Students. Personality and Individual Differences 109: 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboujaoude, Elias. 2014. Compulsive Buying Disorder: A Review and Update. Current Pharmaceutical Design 20: 4021–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtziger, Anja, Marco Hubert, Peter Kenning, Gerhard Raab, and Lucia Reisch. 2015. Debt Out of Control: The Links Between Self-Control, Compulsive Buying, and Real Debts. Journal of Economic Psychology 49: 141–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, Grzegorz. 2018. Phenomenon of Compensative and Compulsive Buying in Poland. A Socio-Economic Study. Economic and Environmental Studies 4: 1181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, Grzegorz, Jorge Capetillo-Ponce, and Dominik Szczygielski. 2020. Compulsive Buying in Poland. An Empirical Study of People Married or in a Stable Relationship. Journal of Consumer Policy 43: 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbola, Maxine. 2011. Spirituality, Self-Efficacy, and Quality of Life Among Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research 11: 5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adler-Constantinescu, Carmen, Elena-Cristina Beşu, and Valeria Negovan. 2013. Perceived Social Support and Perceived Self-Efficacy During Adolescence. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 78: 275–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, Herman, James C. Beaty, Robert J. Boik, and Charles A. Pierce. 2005. Effect Size and Power in Assessing Moderating Effects of Categorical Variables Using Multiple Regression: A 30-Year Review. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, Leona S., and Stephen G. West. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, Cecilie S. 2014. Shopping Addiction: An Overview. Journal of Norwegian Psychological Association 51: 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, Cecilie S., Mark D. Griffiths, Ståle Pallesen, Robert M. Bilder, Torbjørn Torsheim, and Elias Aboujaoude. 2015. The Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale: Reliability and Validity of a Brief Screening Test. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Alison J. 2012. Mindfulness and Consumerism: A Social Psychological Investigation. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Surrey, Surrey, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Astrow, Alan B., Christina M. Puchalski, and Daniel P. Sulmasy. 2001. Religion, Spirituality, and Health Care: Social, Ethical, and Practical Considerations. The American Journal of Medicine 110: 283–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, António. 2020. Recognizing Consumerism as an “Illness of an Empty Soul”: A Catholic Morality Perspective. Psychology & Marketing 37: 250–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, Nathalie, and Nicolas Roussiau. 2010. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES): Validation of the Short Form in an Elderly French Population. Canadian Journal on Aging 29: 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2002. Social Cognitive Theory in Cultural Context. Applied Psychology: An International Review 51: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2003. On the Psychosocial Impact and Mechanisms of Spiritual Modeling: Comment. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 13: 167–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 2015. Culture and Materialism. In Handbook of Culture and Consumer Behavior. Edited by Sharon Ng and Angela Y. Lee. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 299–323. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, Russell W., Melanie Wallendorf, and John F. Sherry, Jr. 1989. The Sacred and the Profane in Consumer Behavior: Theodicy on the Odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research 16: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, Allen E., and P. Scott Richards. 2005. Spiritual Strategy for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Biolcati, Roberta. 2017. The Role of Self-Esteem and Fear of Negative Evaluation in Compulsive Buying. Frontiers in Psychiatry 8: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Donald W. 2007. Compulsive Buying Disorder: A Review of the Evidence. CNS Spectrums 12: 124–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, Donna L. 2007. Empirical Research on Spirituality and Alcoholism: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 7: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Alyssan N. 2007. Gender Differences in Spiritual Development During the College Years. Sex Roles 56: 835–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchko, Kathleen J. 2004. Religious Beliefs and Practices of College Women as Compared to College Men. Journal of College Student Development 45: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2018. Europe’s Young Adults and Religion: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014–16) to Inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops. St Mary’s University Twickenham. London: Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society. Available online: https://www.stmarys.ac.uk/research/centres/benedict-xvi/docs/2018-mar-europe-young-people-report-eng.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Burroughs, James E., and Aric Rindfleisch. 2002. Materialism and Well-Being: A Conflicting Values Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 29: 348–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, Amanda R., and Ellen L. Usher. 2015. Salient Sources of Early Adolescents’ Self-Efficacy in Two Domains. Contemporary Educational Psychology 42: 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Evan C., Michael E. McCullough, and Charles S. Carver. 2012. The Mediating Role of Monitoring in the Association of Religion with Self-Control. Social Psychological and Personality Science 3: 691–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Public Opinion Research. 2019. Szacowanie rozpowszechnienia oraz identyfikacja czynników ryzyka i czynników chroniących hazardu i innych uzależnień behawioralnych—Edycja 2018/2019. Raport z badań. Available online: https://www.uzaleznieniabehawioralne.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hazard_2019_raport_CBOS.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Centre for Public Opinion Research. 2020. Religijność Polaków w ostatnich 20 latach. Available online: https://cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2020/K_063_20.PDF (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Charzyńska, Edyta. 2015. Multidimensional Approach Toward Spiritual Coping: Construction and Validation of the Spiritual Coping Questionnaire (SCQ). Journal of Religion and Health 54: 1629–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyńska, Edyta, and Ewa Wysocka. 2014. The Role of Spirituality and Belief in Free Will in the Perception of Self-Efficacy Among Young Adults. New Educational Review 36: 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Gilad, Stanley M. Gully, and Dov Eden. 2001. Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organizational Research Methods 4: 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, Terence H. W., Catherine S. Tang, Anise Wu, and Elsie Yan. 2016. Gender Differences in Pathways to Compulsive Buying in Chinese College Students in Hong Kong and Macau. Journal of Behavioral Addictions 5: 342–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Simon H., Clayton H. Y. McClintock, Elsa Lau, and Lisa Miller. 2020. The Dynamic Universal Profiles of Spiritual Awareness: A Latent Profile Analysis. Religions 11: 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Marilyn, and Kirsten Calleja. 2008. Shopping Addiction: A Preliminary Investigation Among Maltese University Students. Addiction Research & Theory 16: 633–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Dave, Samson Tse, Max Abbott, Sonia Townsend, Pefi Kingi, and Wiremu Manaia. 2006. Religion, Spirituality and Associations with Problem Gambling. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 35: 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Christopher C. 2004. Addiction and Spirituality. Addiction 99: 539–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, Katelyn M., Anna Krieg, and Sara E. Brownell. 2018. Who Perceives They Are Smarter? Exploring the Influence of Student Characteristics on Student Academic Self-Concept in Physiology. Advances in Physiology Education 42: 200–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guzman, Allan B., Rose A. Lacao, and Czarnina Larracas. 2015. A Structural Equation Modelling on the Factors Affecting Intolerance of Uncertainty and Worry Among a Select Group of Filipino Elderly. Educational Gerontology 41: 106–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager Meezenbroek, Eltica, Bert Garssen, Machteld van den Berg, Dirk van Dierendonck, Adriaan Visser, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2012. Measuring Spirituality as a Universal Human Experience: A Review of Spirituality Questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 336–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempster, Arthur P., Nan M. Laird, and Donald B. Rubin. 1977. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 39: 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dermatis, Helen, Marianne T. Guschwan, Marc Galanter, and Gregory Bunt. 2004. Orientation Toward Spirituality and Self-Help Approaches in the Therapeutic Community. Journal of Addictive Diseases 23: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickie, Jane R., Lindsey V. Ajega, Joy R. Kobylak, and Kathryn M. Nixon. 2006. Mother, Father, and Self: Sources of Young Adults’ God Concepts. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45: 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, Helga, Karen Long, and Rod Bond. 2007. When a Better Self Is Only a Button Click Away: Associations Between Materialistic Values, Emotional and Identity-Related Buying Motives, and Compulsive Buying Tendency Online. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 26: 334–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, Helga. 2005. Compulsive Buying—A Growing Concern? An Examination of Gender, Age, and Endorsement of Materialistic Values as Predictors. British Journal of Psychology 96: 467–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druedahl, Luise C., Duaa Yaqub, Lotte S. Nørgaard, Maria Kristiansen, and Lourdes Cantarero-Arévalo. 2018. Young Muslim Women Living with Asthma in Denmark: A Link between Religion and Self-Efficacy. Pharmacy 6: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlinger, Joyce, and David Dunning. 2003. How Chronic Self-Views Influence (and Potentially Mislead) Estimates of Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Daisy Fan. 2008. Daily Spiritual Experiences and Psychological Well-Being Among US Adults. Social Indicators Research 88: 247–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Shameem, Sumera Sharif, and Iffat Khalid. 2018. How Does Religiosity Enhance Psychological Well-Being? Roles of Self-Efficacy and Perceived Social Support. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, John. 2011. The Four Domains Model: Connecting Spirituality, Health and Well-Being. Religions 2: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J., Harry M. Gibson, and Mandy Robbins. 2001. God Images and Self-Worth Among Adolescents in Scotland. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 4: 103–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouzandeh, Nasrin, Fereshteh Aein, and Cobra Noorian. 2015. Introducing a Spiritual Care Training Course and Determining its Effectiveness on Nursing Students’ Self-Efficacy in Providing Spiritual Care for the Patients. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 4: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gable, Shelly L., and Jonathan Haidt. 2005. What (and Why) Is Positive Psychology? Review of General Psychology 9: 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, Juan A., and Adam Rosario-Rodríguez. 2018. Spirituality and Self-Efficacy in Caregivers of Patients with Neurodegenerative Disorders: An Overview of Spiritual Coping Styles. Religions 9: 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero, Roser, Fernando Fernández-Aranda, Gemma Mestre-Bach, Trevor Steward, Marta Baño, Amparo Del Pino-Gutiérrez, Laura Moragas, Núria Mallorquí-Bagué, Neus Aymamí, Mónica Gómez-Peña, and et al. 2016. Compulsive Buying Behavior: Clinical Comparison with Other Behavioral Addictions. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Mark. 1996. Behavioural Addiction: An Issue for Everybody? Employee Counselling Today 8: 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grim, Brian J., and Melissa E. Grim. 2019. Belief, Behavior, and Belonging: How Faith is Indispensable in Preventing and Recovering from Substance Abuse. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1713–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammermeister, Jon, Matt Flint, Amani El-Alayli, Heather Ridnour, and Margaret Peterson. 2005. Gender Differences in Spiritual Well-Being: Are Females More Spiritually-Well than Males? American Journal of Health Studies 20: 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersla, Joy F., Lisa C. Andrews-Qualls, and Lynne C. Frease. 1986. God Concepts and Religious Among Christian University Student. The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 25: 424–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnish, Richard J., and K. Robert Bridges. 2015. Compulsive Buying: The Role of Irrational Beliefs, Materialism, and Narcissism. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 33: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Kevin A., Brooke E. Randolph, and Timothy D. Gordon. 2016. What Do Clients Want? Assessing Spiritual Needs in Counseling: A Literature Review. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 3: 250–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2003. Advances in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Religion and Spirituality. Implications for Physical and Mental Health Research. The American Psychologist 58: 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, David R. 2005. Spiritual Lifemaps: A Client-Centered Pictorial Instrument for Spiritual Assessment, Planning, and Intervention. Social Work 50: 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, Jeff, Matthew Hankins, Alicia Deale, and Theresa M. Marteau. 2008. Interventions to Increase Self-Efficacy in the Context of Addiction Behaviours: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Health Psychology 13: 607–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk: IBM Corp.

- Islam, Tahir, Zaryab Sheikh, Zahid Hameed, Ikram U. Khan, and Rauf I. Azam. 2018. Social Comparison, Materialism, and Compulsive Buying Based on Stimulus-Response-Model: A Comparative Study Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Young Consumers 19: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Eui J., and Doo H. Kim. 2011. Social Activities, Self-Efficacy, Game Attitudes, and Game Addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14: 213–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Zhaocai, and Mingyan Shi. 2016. Prevalence and Co-Occurrence of Compulsive Buying, Problematic Internet and Mobile Phone Use in College Students in Yantai, China: Relevance of Self-Traits. BMC Public Health 16: 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadden, Ronald M., and Mark D. Litt. 2011. The Role of Self-Efficacy in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders. Addictive Behaviors 36: 1120–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, Todd B., and John B. Nezlek. 2012. Whether, When, and How Is Spirituality Related to Well-Being? Moving Beyond Single Occasion Questionnaires to Understanding Daily Process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38: 1523–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, David A. 2018. Mediation. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Ko, Young-Mi, Sungwon Roh, and Tae K. Lee. 2020. The Association of Problematic Internet Shopping with Dissociation Among South Korean Internet Users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Yvaine W., Catherine S.-K. Tang, Yiqun Q. Gan, and Jee Y. Kwon. 2020. Depressive Symptoms and Self-Efficacy as Mediators Between Life Stress and Compulsive Buying: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Journal of Addiction and Recovery 3: 1017. [Google Scholar]

- Konopack, James F., and Edward McAuley. 2012. Efficacy-Mediated Effects of Spirituality and Physical Activity on Quality of Life: A Path Analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 10: 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koran, Lorrin M., Kim D. Bullock, Heidi J. Hartston, Michael A. Elliott, and Vincent D’Andrea. 2002. Citalopram Treatment of Compulsive Shopping: An Open-Label Study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63: 704–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koran, Lorrin M., Ronald J. Faber, Elias Aboujaoude, Michael D. Large, and Richard T. Serpe. 2006. Estimated Prevalence of Compulsive Buying Behavior in the United States. The American Journal of Psychiatry 163: 1806–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, Eszter, Bettina F. Piko, and Kevin M. Fitzpatrick. 2011. Religiosity as a Protective Factor Against Substance Use Among Hungarian High School Students. Substance Use & Misuse 46: 1346–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejci, Mark J. 1998. A Gender Comparison of God Schemas: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 8: 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Robert F., and Marc N. Potenza. 2013. A Targeted Review of the Neurobiology and Genetics of Behavioural Addictions: An Emerging Area of Research. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie 58: 260–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejoyeux, Michel, and Aviv Weinstein. 2010. Compulsive Buying. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 36: 248–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loustalot, Fleetwood V., Sharon B. Wyatt, Barbara Boss, and Tina McDyess. 2006. Psychometric Examination of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale. Journal of Cultural Diversity 13: 162–67. [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska, Aleksandra, Benicio Gutiérrez-Doña, and Ralf Schwarzer. 2005. General Self-Efficacy in Various Domains of Human Functioning: Evidence from Five Countries. International Journal of Psychology 40: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, Fred, and Carolyn M. Youssef. 2004. Human, Social, and Now Positive Psychological Capital Management: Investing in People for Competitive Advantage. Organizational Dynamics 33: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, David P., Chondra M. Lockwood, and Jason Williams. 2004. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, Aniko, Mark D. Griffiths, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2015. The Prevalence of Compulsive Buying: A Meta-Analysis. Addiction 111: 408–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, Elisa, Kristina L. Tatum, Marcella Glass, Albert Bernath, Daron Ferris, Patrick Reynolds, and Robert A. Schnoll. 2010. Correlates of Smoking Cessation Self-efficacy in a Community Sample of Smokers. Addictive Behaviors 35: 175–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselko, Joanna, and Laura D. Kubzansky. 2006. Gender Differences in Religious Practices, Spiritual Experiences and Health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science & Medicine 62: 2848–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, Sarah J., Frank P. Deane, Peter J. Kelly, and Trevor P. Crowe. 2009. Do Spiritual and Religiosity Help the Management of Cravings on Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Use & Misuse 44: 1926–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., William T. Hoyt, David B. Larson, Harold G. Koenig, and Carl Thoresen. 2000. Religious Involvement and Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Psychology 19: 211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, Susan L., Paul E. Keck, Jr., Harrison G. Pope, Jr., Jacqueline M. Smith, and Stephen M. Strakowski. 1994. Compulsive Buying: A Report of 20 Cases. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55: 242–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McNamara Barry, Carolyn, Larry Nelson, Sahar Davarya, and Shirene Urry. 2010. Religiosity and Spirituality During the Transition to Adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development 34: 311–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisenhelder, Janice B. 2003. Gender Differences in Religiosity and Functional Health in the Elderly. Geriatric Nursing 24: 343–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, William R., and Stephen Rollnick. 2002. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger, Raymond G., Jennifer Redlin, Ross Crosby, Marcella Stickney, Jim Mitchell, Stephen Wonderlich, Ronald Faber, and Joshua Smyth. 2003. Direct and Retrospective Assessment of Factors Contributing to Compulsive Buying. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 34: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofidi, Mahyar, Robert F. Devellis, Dan G. Blazer, Brenda M. Devellis, Abigail T. Panter, and Joanne M. Jordan. 2006. Spirituality and Depressive Symptoms in a Racially Diverse US Sample of Community-Dwelling Adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194: 975–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Astrid, James E. Mitchell, Donald W. Black, Ross D. Crosby, Kelly Berg, and Martina de Zwaan. 2010. Latent Profile Analysis and Comorbidity in a Sample of Individuals with Compulsive Buying Disorder. Psychiatry Research 178: 348–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Astrid, James E. Mitchell, and Martina de Zwaan. 2015. Compulsive Buying. The American Journal on Addictions 24: 132–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, Hart M., Neil H. Cheek Jr, and Paul Au. 1985. Gender Differences in Images of God. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 24: 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Hoa T. 2019. Development and Validation of a Women’s Financial Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 30: 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Thuy-vy T., and Miron Zuckerman. 2016. The Links of God Images to Women’s Religiosity and Coping with Depression: A Socialization Explanation of Gender Difference in Religiosity. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 309–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederle, Muriel, and Lise Vesterlund. 2007. Do Women Shy Away From Competition? Do Men Compete Too Much? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1067–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesiobędzka, Małgorzata. 2010. Rola rodziny i rówieśników w procesie kształtowania się skłonności do kupowania kompulsywnego wśród nastolatków. Psychologia Rozwojowa 15: 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- O’Guinn, Thomas C., and Russell W. Belk. 1989. Heaven on Earth: Consumption at Heritage Village, USA. Journal of Consumer Research 16: 227–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odaci, Hatice. 2011. Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Procrastination as Predictors of Problematic Internet Use in University Students. Computers & Education 57: 1109–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]