Animating Idolatry: Making Ancestral Kin and Personhood in Ancient Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Framing Andean Ancestral Persons: Anthropological Perspectives and Historical Accounts

3. Honorifics and Naming Practice

4. Ritual Spaces for Ancestor Cult

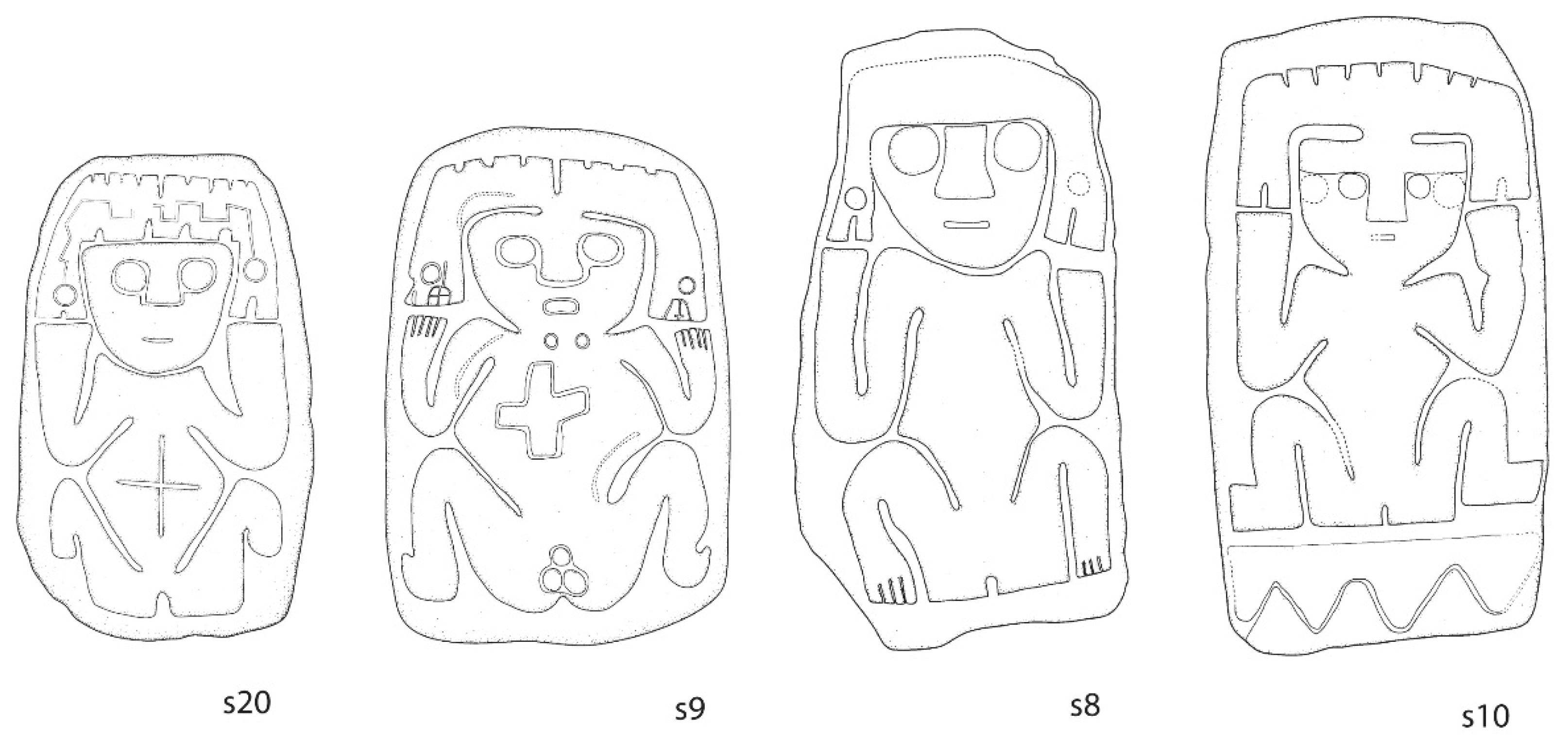

5. Cult Effigies and the Archaeological Record

6. Making Kin out of Stone: Provisional Observations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This describes many forms and disciplinary spaces of archaeology (e.g., Alberti 2016; Pauketat 2013). For the Andes, see (Bray 2009; Lau 2008; Sillar 2009) and for ethnographic and historical basis, see (Allen 2015; Duviols 1979; Salomon 1998). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | For example, very early in the Relación de los Agustinos, 1560, by Fr. Juan de San Pedro (Castro de Trelles 1992, p. 22) or by the time of Francisco de Ávila’s Tratado, in 1608 (in Arguedas and Duviols 1966, p. 200). |

| 4 | The close cultic relationship between ancestral images, especially mummies, and their worshipping descendants was widely acknowledged at least since the early detective work of Polo de Ondegardo on Inca mummies (MacCormack 1991, pp. 390–91). |

| 5 | Similar huanca-like lithified tutelaries were called Guachecoal in the Huamachuco area (Juan de San Pedro, in Castro de Trelles 1992, p. 27). There were other terms for them, such as marca apárac and marcachárac (Arriaga 1999, p. 31). At other times, they were referred to as marcayoc, llactayoc, or chacrayoc, referring to their vigilance over villages and fields. |

| 6 | See also the different names of similar objects of Huamachuco province (Castro de Trelles 1992, p. 56). |

| 7 | “Camayoq” signifies master or owner, and “wasi” means house. |

| 8 | Conopas and illas were another category of small talismanic objects, occasionally conflated with the other “lesser idols”. Conopas were typically in the form of animals and plants and were worshipped to give abundance to the form depicted, e.g., camelids, guinea pigs, maize. These could communicate with their bearers, were efficacious in household-level ritual activities, and were also valuable heirlooms, but did not feature heavily in the wider cults of founding ancestors (Arriaga 1999, pp. 35–36). Many of these included “mama” in their names, connoting the maternal quality and also the parental/authority associations of the “lesser idols”. |

| 9 | They were frequently compared to ancient Roman family gods, the lares and penates. |

| 10 | Ávila notes the distinction that cunchur (of Huarochirí) act as intermediaries for the principal huacas/gods (Ávila, in Arguedas and Duviols 1966, pp. 255–56), while the chanca helps in divining and communicating the will of the cunchur. |

| 11 | Overseen by Hernando de Avendaño in the highland Chancay and Cajatambo areas. |

| 12 | There are also certainly Christian connotations, in the use of “lord” and “father”. The term “yaya” (or father) is also used as an honorific for celestial bodies (e.g., sun, stars) and large landforms, such as mountains and boulders (Itier 2003, p. 783; Taylor 2000, p. 33). |

| 13 | Hamilton (2018, p. 82) also notes, following Sillar (2012), that conopa manufacturing may have been related to Inca standardized production and materialized ideology. |

| 14 | There is also mention of Manco Capac ordering a gold effigy made of his mother Mama Ocllo; his afterbirth was placed in the stomach area of the figure. |

| 15 | This resonates with Zuidema’s observation that the oldest figures in long-lasting genealogies are so old and “so far removed” that they have been turned into stone (Zuidema 1973, p. 19). |

References

- Acosta, Jose de. 1954. Historia Natural y Moral de Las Indias. In Obras del Padre José de Acosta. Edited by Francisco Mateos. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, pp. 1–247. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, Benjamin. 2016. Archaeologies of Ontology. Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Catherine J. 1988. The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Catherine J. 2015. The Whole World Is Watching: New Perspectives on Andean Animism. In The Archaeology of Wak’as. Edited by Tamara L. Bray. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas, José María, and Pierre Duviols, eds. 1966. Dioses y Hombres de Huarochirí: Narración Quechua Recogida Por Francisco de Avila (¿1598?). Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga, Pablo José. 1999. La Extirpación de La Idolatría En El Piru (1621). Edited by Henrique Urbano. Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Bartolomé de Las Casas. [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño, Fernando. 2003. Relación de Las Idolatrías de Los Indios de Fernando de Avendaño. In Proceso y Visitas de Idolatrías: Cajatambo, Siglo XVII. Edited by Pierre Duviols. Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, pp. 713–19. First published 1617. [Google Scholar]

- Bazán del Campo, Francisco. 2008. Monolitos Hallados En El Sector de Batán En La Ciudad de Huaraz. Hirka 16: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Tamara L. 2009. An Archaeological Perspective on the Andean Concept of Camaquen: Thinking through Late Pre-Columbian Ofrendas and Huacas. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19: 357–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bria, Rebecca. 2017. Department of Anthropology Ritual, Economy, and the Construction of Community at Ancient Hualcayán (Ancash, Peru). Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, Mirko. 2018. Cabezas Clavas de La Tradición Recuay: Exposición de La DDC-Ancash 2018–2019. Huaraz: Dirección Desconcentrada de Cultura—Ancash, Huaraz. [Google Scholar]

- Castro de Trelles, Lucila, ed. 1992. Relación de Los Agustinos de Huamachuco. Lima: Fondo Editorial PUCP. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo, Bernábe. 1990. Inca Religion and Customs. Edited by Roland Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press. First published 1653. [Google Scholar]

- Creese, John L. 2017. Art as Kinship: Signs of Life in the Eastern Woodlands. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 24: 643–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Carolyn. 2010. A Culture of Stone: Inka Perspectives on Rock. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeonardis, Lisa, and George F. Lau. 2004. Life, Death and Ancestors. In Andean Archaeology. Edited by Helaine Silverman. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 77–115. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 1986. In the Society of Nature: A Native Ecology in Amazonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dillehay, Tom D., ed. 1995. Tombs for the Living: Andean Mortuary Practices. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Mary Eileen. 1988. Ancestor Cult and Burial Ritual in Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Central Peru. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dransart, Penelope, ed. 2006. Kay Pacha: Cultivating Earth and Water in the Andes. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Duviols, Pierre. 1971. La Lutte Contre Les Religions Autochtones Dans Le Pérou Colonial: L’extirpation de l’idolâtrie, Entre 1532 et 1660. Lima: Institut français d’études andines. [Google Scholar]

- Duviols, Pierre. 1977. Un Symbolisme Andin Du Double: La Lithomorphose de l’ancêtre. Actes du XLIIe Congrès International des Américanistes (Paris) 4: 359–64. [Google Scholar]

- Duviols, Pierre. 1979. Un Symbolisme de l’occupation, de l’aménagement et de l’exploitation de l’espace: La Monolithe ‘huanca’ et Sa Fonction Dans Les Andes Préhispaniques. L’Homme 19: 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duviols, Pierre, ed. 2003. Procesos y Visitas de Idolatrías: Cajatambo, Siglo XVII. Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos. [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhout, Peter, and Lawrence S. Owens, eds. 2015. Funerary Practices and Models in the Ancient Andes: The Return of the Living Dead. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Falcón, Victor, and Patricia Diaz. 1998. Representaciones Líticas de Tinyash. Andesita 1: 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto, Carlos. 2012. Warfare and Shamanism in Amazonia. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa, Jorge A. 2009. Diversidad Formal y Cronológica de Las Prácticas Funerarias Recuay. Kullpi 2: 35–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gero, Joan M. 1991. Who Experienced What in Prehistory? A Narrative Explanation from Queyash, Peru. In Processual and Postprocessual Archaeologies: Multiple Ways of Knowing the Past. Edited by Robert W. Preucel. Occasional Paper No. 10. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, pp. 126–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gose, Peter. 2006. Mountains historicized: Ancestors and landscape in the colonial Andes. In Kay Pacha: Cultivating Earth and Water in the Andes. Edited by Penelope Dransart. Oxford: BAR International Series 1478, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gose, Peter. 2016. Mountains, Kurakas and Mummies: Transformations in Indigenous Andean Sovereignty. Poblacion y Sociedad 23: 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Grieder, Terence. 1978. The Art and Archaeology of Pashash. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guaman Poma de Ayala, Felipe. 1980. Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno. Edited by John Murra, Rolena Adorno and Jorge L. Urioste. Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno. First published 1615. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell, Irving. 1960. Ojibwa Ontology, Behavior, and World View. In Culture in History. Edited by Stanley Diamond. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Andrew. 2018. Scale & the Incas. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Príncipe, Rodrigo. 1923. Mitología Andina—Idolatrías En Recuay. Inca 1: 25–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, Bebel. 2009. Historia Prehispánica de Huari: 3000 Años de Historia Desde Chavín Hasta Los Inkas. Huari: Instituto de Estudios Huarinos. [Google Scholar]

- Isbell, William H. 1997. Mummies and Mortuary Monuments: A Postprocessual Prehistory of Central Andean Social Organization. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Itier, César. 2003. Apéndice: Textos Quechuas de Los Procesos de Cajatambo. In Procesos y Visitas de Idolatrías—Cajatambo, Siglo XVII. Edited by Pierre Duviols. Lima: IFEA, pp. 781–818. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Justin D., and Edward R. Swenson, eds. 2018. Powerful Places in the Ancient Andes. Albuquerque: Unviersity of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaulicke, Peter. 2001. Memoria y Muerte En El Perú Antiguo. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosiba, Steven, John Wayne Janusek, and Thomas B. Cummins, eds. 2020. Sacred Matter: Animacy and Authority in the Americas. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2000. Espacio Ceremonial Recuay. In Los Dioses Del Antiguo Peru. Edited by Krzysztof Makowski. Lima: Banco de Crédito, pp. 178–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2002. Feasting and Ancestor Veneration at Chinchawas, North Highlands of Ancash, Peru. Latin American Antiquity 13: 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, George F. 2006. Recuay Tradition Sculptures of Chinchawas, North Highlands of Ancash, Peru. Zeitschrift für Archäeologie Aussereuropäischer Kulturen 1: 183–250. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2008. Ancestor Images in the Andes. In Handbook of South American Archaeology. Edited by Helaine Silverman and William H. Isbell. New York: Springer Science, pp. 1025–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2011. Andean Expressions: Art and Archaeology of the Recuay Culture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2013. Ancient Alterity in the Andes: A Recognition of Others. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2015a. Different Kinds of Dead: Presencing Andean Expired Beings. In Death Rituals, Social Order and the Archaeology of Immortality in the Ancient World. Edited by Colin Renfrew, Michael J. Boyd and Iain Morley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 168–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2015b. The Dead and the Longue Durée in Peru’s North Highlands. In Living with the Dead in the Andes. Edited by Izumi Shimada and James Fitzsimmons. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 200–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F. 2016. An Archaeology of Ancash: Stones, Ruins and Communities in Ancient Peru. London and Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, George F., and Milton Luján Dávila. 2020. Informe Final del Proyecto de Investigación Arqueológica, Región Pallasca (Temporada 2019). Lima: Ministerio de Cultura del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- López Austin, Alfredo. 1988. The Human Body and Ideology: Concepts of the Ancient Nahuas. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- MacCormack, Sabine. 1991. Religion in the Andes: Vision and Imagination in Early Colonial Peru. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meddens, Frank. 2020. Reflective and Communicative Waka: Interaction with the Sacred. In Archaeological Interpretations: Symbolic Meaning within Andes Prehistory. Edited by Peter Eeckhout. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía Xesspe, Toribio. 1941. Walun y Chinchawas: Dos Nuevos Sitios Arqueológicos En La Cordillera Negra. Chaski 1: 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Kenneth. 1997. Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640–1750. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Alexia. 2019. La Sculpture Recuay: Signification Iconographique et Fonction Sociale d’un Marqueur Territorial Dans La Sierra Nord Centrale Du Pérou (100–700 Ap. J.-C.). Paris: Sorbonne Université. [Google Scholar]

- Murra, John V. 1980. The Economic Organization of the Inka State. Greenwich: Research in Economic Anthropology. Supplement 1. Greenwich: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, Juan. 2012. El Conjunto Funerario de Ichic Wilkawaín. Exhibición en el Museo Arqueológico de Ancash. Peru: Huaraz. [Google Scholar]

- Pauketat, Timothy R. 2013. An Archaeology of the Cosmos: Rethinking Agency and Religion in Ancient America. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pillsbury, Joanne. 2008. Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–900. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Polia, Mario. 1999. La cosmovisión religiosa andina en documentos inéditos del Archivo Romano de la Compañia de Jesus 1581–1752. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Polia, Mario, ed. 2017. Documentos Inéditos Del Archivo Romano de La Compañia de Jesus (Ministros de Cultos Autóchtonos: Sacerdotes, Terapeutas, Adivinos y Brujos). Cusco: Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte, Víctor M. 2015. Regional Perspective of Recuay Mortuary Practices: A View from the Hinterlands, Callejón de Huaylas, Peru. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Quilter, Jeffrey. 1996. Continuity and Disjunction in Pre-Columbian Art and Culture. RES 29/30: 303–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, John Howland. 1946. Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest. In Handbook of South American Indians, Volume 2: The Andean Civilizations. Edited by Julian Steward. Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, vol. 143, pp. 183–330. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Frank. 1991. Introductory Essay: The Huarochirí Manuscript. In The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Religion. Edited by Frank Salomon and George Urioste. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Frank. 1995. ‘Beautiful Grandparents’: Andean Ancestor Shrines and Mortuary Ritual as Seen through Colonial Records. In Tombs for the Living: Andean Mortuary Practices. Edited by Tom D. Dillehay. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, pp. 315–53. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Frank. 1998. How the Huacas Were: The Language of Substance and Transformation in the Huarochiri Quechua Manuscript. RES 33: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, Frank. 1999. Testimonies: The Making and Reading of Native South American Sources. In Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas: Volume III, South America, Part 1. Edited by Frank Salomon and Stuart B. Schwartz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–95. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Frank. 2018. At the Mountains’ Altar: Anthropology of Religion in an Andean Community. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Frank, and George Urioste, eds. 1991. The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Religion. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando, ed. 2009. The Occult Life of Things: Native Amazonian Theories of Materiality and Personhood. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2019. Amerindian Political Economies of Life. HAU Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9: 461–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento de Gamboa, Pedro. 2007. History of the Incas. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaedel, Richard P. 1948. Stone Sculpture in the Callejón de Huaylas. In A Reappraisal of Peruvian Archaeology. Edited by Wendell C. Bennett. Menasha: Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, vol. 4, pp. 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Schaedel, Richard P. 1952. An Analysis of Central Andean Stone Sculpture. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, Izumi, and James L. Fitzsimmons. 2015. Living with the Dead in the Andes. Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9: 461–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sillar, Bill. 2009. The Social Agency of Things? Animism and Materiality in the Andes. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19: 369–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillar, Bill. 2012. Patrimoine vivant: Les illas et conopas des foyers andins. Techniques & Culture 58: 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sillar, Bill, and Gabriel Ramón. 2016. Using the Present to Interpret the Past: The Role of Ethnographic Studies in Andean Archaeology. World Archaeology 48: 656–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano Infante, Augusto. 1950. Memoria Del Director Del Museo Arqueológico de Ancash. Huaraz: Imp. El Lucero. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Gerald. 2000. Travaux de l’Institut français d’études andines 126 Camac, Camay y Camasca y Otros Ensayos Sobre Huarochirí y Yauyos. Lima: Travaux de l’Institut français d’études andines, p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, Julio C. 1929. Antiguo Perú: Primera Época. Lima: Comisión Organizadora del Segundo Congreso de Turismo. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Donald E., and Rogger Ravines. 1973. Tinyash: A Prehispanic Village in the Andean Puna. Archaeology 26: 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Richard F., ed. 1992. The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Guchte, Maarten. 1990. ‘Carving the World’: Inca Monumental Sculpture and Landscape. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Guchte, Maarten. 1996. Sculpture and the Concept of the Double among the Inca Kings. RES 29/30: 257–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1992. From the Enemy’s Point of View: Humanity and Divinity in an Amazonian Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2001. GUT Feelings about Amazonia: Potential Affinity and the Construction of Sociality. In Beyond the Visible and the Material. Edited by Laura M. Rival and Neil L. Whitehead. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Walens, Stanley. 1981. Feasting with Cannibals: An Essay on Kwakiutl Cosmology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, Steven A. 2007. Huaraz Prehispánico. Hirka 12: 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, Andrzej. 1978. El Mausoleo de Piedra con Decoración Plástica: Callejón de Huaylas. In III Congreso Peruano Del Hombre y La Cultura Andina. Edited by Ramiro Matos. Lima: Editora Lasontay, pp. 443–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zuidema, R. Tom. 1973. Kinship and ancestor cult in three Peruvian communities: Hernández Príncipe’s account of 1622. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Ètudes Andines 2: 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zuidema, R. Tom. 1990. Dynastic Structures in Andean Culture. In Northern Dynasties: Kingship and Statecraft in Chimor. Edited by Michael E. Moseley and Alana Cordy-Collins. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, pp. 489–505. [Google Scholar]

| Priest-Writer | Year of Visit | Region/Number of Towns-Confessors | Huacas Principales/Públicas | Mallquis | Huancas | Lesser Idols |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan de San Pedro (Castro de Trelles 1992) | c.1560 | Huamachuco | - | - | 300+ Guachecoal(es) | - |

| Arriaga and Avendaño (Arriaga 1999) | 1617–1618 | Cajatambo and Chancay | 603 | 617 | - | 3418 |

| Francisco de Ávila (Arguedas and Duviols 1966, p. 255) | 1611 | Huarochirí | Mentions that over 5000 idols were observed in five parishes comprised of over 7000 confessors | |||

| Hernández Príncipe (1923) | 1622 | Recuay (Huaylas) (ca. 10 communities) | 46 | “100 y más” | - | “no hay número” (includes huancas) |

| Diego Álvarez de Paz (in Duviols 2003; Polia 1999) | 1618 | Ocros and Lampas provinces (2427 confessors) | 345 | 230 | - | 1225 |

| None identified (Polia 1999, p. 434) | 1619 | Conchucos (5 doctrines, 5 villages and 3104 persons) | 297 | - | - | - |

| Example 1.Prayer to shrine (of two stone effigies) to bring forth maize beer (Itier 2003, p. 785). | |

| A qapaq yaya, | Oh, powerful father |

| a apu yaya, | oh lord father |

| ka, | Take |

| kayta mikuy, | eat this |

| kayta upyay, | drink this |

| aswa mirananpaq | so that there’s abundance of chicha |

| Example 2.Prayer (to conopa (small charmstone)) for camay, vitalizing force (Itier 2003, p. 790). | |

| Yaya qunupa, | Father conopa, |

| runakta kamay, | give vitality to the people, |

| waynakta kamay, | give vitality to the young ones, |

| alli kanapaq kamay, | Give them vitality so that they are well, |

| mikuyta qumay, | give us food, |

| aykatapis qumaytaq | and give us all that is necessary. |

| Example 3.Prayer/offering to Huari mummy bundles (Itier 2003, p. 805–6). | |

| Yaya warikuna, | Huari fathers, |

| mikuy kamaq, | who vitalize the food, |

| puĉa kamaq, | who vitalize the nourishment, |

| tiqŝi kamaq, | who vitalize the soil, |

| parquyuq, | Owners of the canals, |

| ĉakrayuq, | Owners of the fields, |

| kayta mikuy, | eat this, |

| kayta upyay, | take this, |

| ĉuriykikuna arpaŝunki, | Your children make you an offering, |

| allin ĉakra kaĉun | to have good fields, |

| allin mikuy kaĉun. | to have good harvests. |

| Example 4.On the intercessional role of Con Churi (Salomon and Urioste 1991, p. 86). | |

| cay chica llactam cay chaupi ñamca llacsa huatu mira huatu lluncu huachac hurpay huachac ñis cap cascanta yachanchic chaymantas cay ñiscanchiccuna ñau pachaca chayman ric runacunacta con churiquip yayaiquip ma chuyquip simincamachu hamunqui ñispas ñic carcan chaysi manam ñictaca ri cuti con choriiquictarac huyarichimuy ñiptin cotimuc carcan | This is all we know about Chaupi Ñamca, Llacsa Huato, Mira Huato, Lluncho Huachac, and Urpay Huachac. In the old days, they say, these huacas would ask those who went to them, “Have you come on the advice of your own Con Churi, your father, or your elders?” |

| Sapa Inca Name | Huauque Name | Material | Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinchi Roca | Guanachiri Amaro | stone | fish |

| Manco Capac | Indi | bird (~falcon) | |

| (another) Huanacauri | (stone) | mountain | |

| Lloqui Yupanqui | Apo Mayta | ||

| Capac Yupanqui | Apu-Mayta | ||

| Inca Roca | (Vica-Quirao?) | stone | |

| Inca Viracocha | Inga Amaro | ||

| Pachacuti Inca | Indi illapa | golden | (bulto)—made in his image |

| Yamque Yupanqui | golden | (bulto)—made in his image | |

| Topa Inca Yupanqui | Cuxi churi | ||

| Huayna Capac | Guaraqui inga | gold | (large) |

| Atahualpa | Ynga Guauqui, and Ticci Capac | bulto |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lau, G.F. Animating Idolatry: Making Ancestral Kin and Personhood in Ancient Peru. Religions 2021, 12, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050287

Lau GF. Animating Idolatry: Making Ancestral Kin and Personhood in Ancient Peru. Religions. 2021; 12(5):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050287

Chicago/Turabian StyleLau, George F. 2021. "Animating Idolatry: Making Ancestral Kin and Personhood in Ancient Peru" Religions 12, no. 5: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050287

APA StyleLau, G. F. (2021). Animating Idolatry: Making Ancestral Kin and Personhood in Ancient Peru. Religions, 12(5), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050287