Abstract

This study examines the relationship between body and spirituality in kaḷaripayaṯṯu (kaḷarippayaṯṯu), a South Indian martial art that incorporates yogic techniques in its training regimen. The paper is based on ethnographic material gathered during my fieldwork in Kerala and interviews with practitioners of kaḷaripayaṯṯu and members of the Nāyar clans. The Nāyars of Kerala created their own martial arts that were further developed in their family gymnasia (kaḷari). These kaḷaris had their own training routines, initiations and patron deities. Kaḷaris were not only training grounds, but temples consecrated with daily rituals and spiritual exercises performed in the presence of masters of the art called gurukkals. For gurukkals, the term kaḷari has a broader spectrum of meaning—it denotes the threefold system of Nāyar education: Hindu doctrines, physical training, and yogico-meditative exercises. This short article investigates selected aspects of embodied spirituality in kaḷaripayaṯṯu and argues that body in kaḷari is not only trained but also textualized and ritualized.

1. Introduction

Ferrer (2008, p. 2) defines embodied spirituality as a philosophy that regards all dimensions of human beings –body, soul, spirit, and consciousness—as “equal partners in bringing self, community, and world into a fuller alignment with the Mystery out of which everything arises”. In other words, in embodied spirituality, the body is a key tool for spiritual transformation and the search for mystical truths. Hence, embodied spirituality is in contrast with spirituality, which affirms the dichotomy of body and spirit (Ulland 2012, p. 101). However, Trousdale (2013, pp. 23–24) observes that the term is essentially a Western invention and could not have been in use in Eastern religious traditions, where the human body has long been seen as an instrument for generating various supernatural powers and a vehicle for salvation. This is especially true for esoteric paths of yoga and Tantra. These traditions promise bodily empowerment, immortality, and spiritual mastery, which grant omniscience. In fact, many Tantric teachings justify a variety of rituals, even those considered an anathema by orthodox Brahmins, if they lead to the attainment of liberation (mokṣa) or the fulfillment of worldly desires (bhoga) (Biernacki 2007, p. 208). The reconciliation of both aims, rather than denying one in favor of the other, is recognized as being one of the hallmarks of Tantric cults (Brooks 1992, p. 182). A narrow definition of Tantra focusses on cults that are directly associated with esoteric, Sanskrit literary traditions, namely with the tantras, saṃhitās, āgamas or paddhatis. A wider definition positions these scriptural traditions within a broader context of regional beliefs, mystical traditions of yoga practices, and the science of mantras (Lorenzen 2006, p. 65). Thus, the wider definition may therefore include also various styles of kaḷaripayaṯṯu (kaḷarippayaṯṯu), a Keralan martial art that is often practiced as a form of spiritual exercise so—called kaḷari-vidyā. This paper investigates the relationship between body and spirituality in kaḷaripayaṯṯu and shows how its training incorporates yogic and Tantric practices. In this study, I refer to ethnographic material gathered during my fieldwork in Kerala and interviews with practitioners of the martial art.1 The study is also based on my personal experience of training in the Northern style of kaḷaripayaṯṯu in CVN Kaḷari Nadakkavu in Kerala, during the years 2007–2013.

This short article is not meant as a comprehensive study of the complex spiritual heritage of the Keralan martial arts; instead, it investigates selected aspects of embodied spirituality in kaḷaripayaṯṯu.

2. Nāyars and Their Martial Arts

I first heard about kaḷaripayaṯṯu during my research on the Tantric traditions of Kerala. At that time, I travelled to Kannur district to conduct an interview with Swami Nādānta, a Tantric master of the Meppaṭ clan, who belonged to the Nāyar caste. To my surprise, Nādānta’s family temple was not referred to by locals as ambalam or kṣetra (the usual Malayalam terms for Hindu temples), but was known as Kaḷari Mantra-śālā. While the latter compound (The Hall of Mantras) indicates a Tantric character of the tradition, kaḷari is a term usually used to designate a martial arts hall where the Nāyars perfect their fighting skills. Kaḷari, according to Nādānta, indicates the Nāyar spiritual training where the practice of mantra-chanting and Tantric rites is entangled with physical and religious education. In the past, many Nāyars were known as warriors and mercenaries. They created their own martial arts that were further developed and taught in their family gymnasia. These kaḷaris had their own training system, rites of passage, and deities. For many Nāyars, kaḷaris were holy grounds sanctified with everyday ritualized training routines (Bayly 1984, pp. 177–213). Interestingly, kaḷaris provided martial art training for boys and girls. Kodumala Kunki and Unniyarcha were two of the medieval heroines praised for their expertise in the martial arts (Zarrilli 2005, p. 44; Chandrababu and Thilagavathi 2009, p. 156). Gurukkals, the masters of the art, would often use Tantric mantras to invoke the deities of kaḷari before the training and ask them for the empowerment and divinization of adepts’ bodies. The ancient Meppaṭ Tantrics, like many traditional kaḷari masters, cultivated yogic powers and engaged in practices of summoning female divine powers (śaktis) into their bodies. The rituals and spiritual practices of the Nādānta tradition aimed at empowerment and final liberation through identification with these divine entities. My meeting with the Meppaṭ family turned my attention to the relationship between body and spirituality in the various schools of kaḷaripayaṯṯu.

In recent years, kaḷaripayaṯṯu has gained popularity in India and abroad as a traditional martial art and a spectacular performing art.2 Developed exclusively in the Southern State of Kerala, it is now known and practiced globally. Its elements have been adapted by actors, yoga teachers, dancers, and manifold other practitioners, who appreciate the health benefits of kaḷaripayaṯṯu training. However, the kaḷaripayaṯṯu practitioners traditionally belonged exclusively to the Nāyar community. The Nāyars were natives of Kerala who gained high social status through connections and ties with the Brahmin caste, the Nambudiris. The term “Nāyar” (spelled “Nair” in modern Kerala) most likely comes from the Sanskrit nāyaka—leader, chief. Some Keralan inscriptions also show that “-Nāyar” was often added as an honorific suffix to names of famous warriors (Gurukkal 1992, p. 88). However, this caste was not uniform and comprised a constellation of various groups and communities of varying social ranks (Gough 1952, p. 72). Nevertheless, the Nāyars formed a respected community of landlords and warriors, who were even praised by Barbosa, a 16th-century Portuguese traveler and chronicler, for their courage and fighting skills (Barbosa 1995, pp. 124–28).

3. Kaḷaripayaṯṯu—Its Name and Origin

Kumaran (1993, p. 18) observes that in Kerala there were three institutions in which martial arts were taught:

- (1)

- kaḷari—local and family-owned schools where young people acquired physical fitness and proficiency in using weapons. There were many local fighting styles known collectively in Kerala as kaḷaripayaṯṯu. Distinctly different fighting techniques were used by tribal communities living in the Wayanad region. The first kaḷaris taught hand-to-hand combat and archery. Over time, the repertoire of techniques and weapons has expanded significantly.

- (2)

- kudippalikūdam—Buddhist centers of fencing.

- (3)

- salai—temple schools. The teachers in these schools were Brahmins, experts in the Vedic lore, martial arts, and archery.

Some scholars derive the term kaḷari from the Sanskrit khalūrikā (“battlefield”), others from the Tamil kalam (“arena”). The word -payyattu means training or practice (Pati 2010, p. 175). The whole compound is often translated as “place of exercise” (Zarrilli 1998, p. vii).

Today, as kaḷaripayaṯṯu has gained worldwide recognition, there are many adepts praising its antiquity or even claiming that kaḷaripayaṯṯu is the “mother of all martial arts”, the oldest martial art in the world. Some also quote popular Keralan legends that talk about a divine hero Paraśurāma, who reclaimed the land of Kerala from the ocean and taught kaḷaripayaṯṯu to his disciples (John 2011, p. 5). Another widespread legend says that Bodhidharma, an Indian Buddhist monk who supposedly lived in the 5th–6th centuries C.E, introduced kaḷaripayaṯṯu to China and Japan, where it evolved into kung fu and karate (McDonald 2007, p. 147). Some gurukkals still recall ballads from the 4th century C.E that speak of warrior-artists, experts in kaḷaripayaṯṯu, who set off in search of fame in the Tulu country (the modern state of Karnataka). On the other hand, historians have dated the origins of kaḷaripayaṯṯu to a fully fledged martial art of the 11th century CE. It has been postulated that the codification of this martial art began during the so-called “Hundred Years’ War” between the Cera and Ćola empires (c. 1000–1100) (Pillai 1970, p. 241). However, other scholars argue that kaḷaripayattu is a recent term that replaced the older kaḷari-vidyā,3 a word referring primarily to a spiritual practice of certain Keralan clans. Thus, for instance, Sasidharan P.K., a researcher on the history of kaḷari states:

Many of the terms, concepts used to describe kaḷari-vidyā have been coined in the recent years in the process of some ideological appropriations of the tradition. In its entirety, it is not a martial art practice, though some of its aspects have been used for military training during the medieval period.4

Moreover, it should be noted that the currently known styles of kaḷaripayaṯṯu developed under the influence of the great Tamil martial arts, such as ati murai or varma ati. Additionally, in modern times, many Muslim or Christian gurukkals follow the same training routine as the Hindu instructors but they remove the Hindu idols from the kaḷari, reinterpret initiatory rituals, and introduce simple prayers at the start of the training sessions. The scholars of the Keralan martial arts distinguish between the Northern, Central and Southern styles of kaḷaripayaṯṯu and indicate that, in time, adepts from castes other than Nāyar were permitted to attend the kaḷari training (Zarrilli 1998, p. 27). In modern times, CVN Kaḷari is among the best-known traditional schools of the northern style. The CVN Kaḷari in Nadakkavu, Calicut was established in 1945 by K. Narayanan (1927–2000) and is currently run by his sons: Anil Kumar, Sunil Kumar, and Gopa Kumar. In this article, I refer to the practices and training routines that I studied in CVN Kaḷari Nadakkav, under these gurukkals.

4. The Ritual Paradigm of Kaḷaripayaṯṯu

Kaḷaripayaṯṯu training functions in a paradigm of Hindu daily rituals (nitya), occasional ceremonies (naimittika), and initiations (dīkṣā). In the context of the kaḷari training, it can be said that nitya is a compulsory rite performed at properly appointed times each day and at the start and end of training. Naimittika are rituals performed on special days of the year, during holidays or other important events (Benard 1999, p. 23). Naimittika rituals in kaḷari are, for example, services in honor of the former masters of a given tradition. According to the Hindu doctrine, while performing nitya and naimittika rituals does not bring any specific benefits, these rituals are obligatory religious activities through which adepts affirm their bond with a specific tradition (Flood 1996, p. 132). In other words, nitya rituals express the views and values of a given community through a hermetic language of signs and symbols. In this way, by performing specific rituals, the imponderables of a given community are preserved. Similarly, an adept of kaḷaripayaṯṯu confirms their affiliation to a given school by daily ritual acts—for instance, venerating the gurukkals, prostrating themselves before the kaḷari deities, and circumambulating the training hall (see Appendix A Figure A1).

The initiatory rituals also play an important role in the life of kaḷari. The first of these rites introduces a new adept into the “family” of a kaḷaripayaṯṯu school. This is usually a simple rite in which the gurukkal anoints and blesses a new student and then teaches them basic movements. However, before the anointment, a flower offering is typically performed for the patron gods and a coconut is sanctified and then ritually cracked open near the entrance to the kaḷari. The fruit is then shared by all the adepts and this special “communion” additionally unites the community of a kaḷari. The progress of the adept is marked by subsequent initiations. During these dīkṣās, a gurukkal introduces an adept to new weapons and techniques. Thus, Hindu ritual praxis forms a frame within which the kaḷaripayaṯṯu training is conducted.

5. Kaḷari-Yoga: Defining Yoga of Kaḷaripayaṯṯu

This paper argues that the practice of kaḷaripayaṯṯu, like yoga, aims to develop external and internal powers of the human body, and what Tantric and yogic texts call vikalpa-samskāra—gradual refinement of mental states (Rastogi 1993, p. 250).

The term “yoga” has been commonly associated with various philosophical systems, esoteric traditions and health-oriented practices.5 Jacobsen (2005, p. 4) observes that yoga is a polyvalent Sanskrit term which, depending on the context, may refer to (1) spiritual discipline that leads one to the attainment of a goal; (2) techniques of controlling the body and the mind; (3) one of the classical Indian systems of philosophy (darśana); (4) a particular technique or school of yoga, for example, haṭha; and (5) the goal of yoga practice. In fact, even though yoga, in modern parlance, is commonly understood as a practice (of physical postures, breathing, meditation, etc.), in many Indian treatises the term was often used to indicate a spiritual goal to be achieved through those practices (Mallinson and Singleton 2016). This goal ranged from attaining supernatural powers, especially in early ascetic traditions and Tantra, to being liberated from the cycle of reincarnations.

The best-known paradigm of classical yoga is the conception of the aṣṭāṅgayoga (eight-limbed yoga) presented in the Yogasūtras of Patañjali. The aṣṭāṅgayoga system presents a vision of yoga as a set of exercises that discipline body and mind and by which a practitioner gains progressive control over their senses and eventually a spiritual mastery. The path of aṣṭāṅgayoga starts with the practice of yama (ethical norms) and niyama (observances). The other limbs relate to “the physical and psychic dimensions of embodiment”. In Tantric and haṭhayogic traditions, the āsanas (postures) and prāṇāyāma6 (breath control) are practised to gain control over subtle energies in the body. A proper practice of both leads to pratyāhāra—withdrawal of the senses. The above-mentioned limbs are also known as outer limbs (bahiraṅga). The inner ones (antaraṅga) are dhāraṇā (concentration), dhyāna (meditation), and samādhi (deep contemplation) (Sarbacker 2012, p. 197).

Nevertheless, there were also systems that employed three, four or six limbed yoga (Rastogi 1993).7 Tantric traditions developed further those yogic techniques and focused on so-called inner ritualism (antar-yāga) that additionally involved visualizations and creative meditation (bhāvana)8, purification of one’s microcosmic body (bhūtaśuddhi), its deification with mantras (nyāsa), and methods of awakening kuṇḍalinī śakti, the inner energy (Gupta 1992; Flood 1996, pp. 157–62). There were also other, esoteric traditions like those of Nātha Yogis (9th c. C.E.) who combined aspects of Tantra, alchemy, and yogic methods of purification to attain “immortality and embodied perfection” (Alter 2004, p. 21).

It is also interesting to note that, according to Indian epics, a warrior who was on his deathbed became yoga-yukta, literally “yoked to yoga”, with “yoga” here meaning a chariot. However, it was not his own ordinary chariot but a celestial one that, blazing in flames, would soar skywards, taking the warrior’s spirit to the heaven of gods and heroes (White 2012, pp. 3–4). This colourful metaphor suggests that yoga, in the context of a martial art practice, could be understood as a vehicle for salvation, and physical and spiritual development. Hence, for the purpose of this study, it is defined as a practice of disciplining of body and mind for spiritual aims and bodily empowerment.

In fact, many kaḷaripayaṯṯu masters compare the stages of martial art training with those of yoga. In their words, the long-term training of kaḷaripayaṯṯu or yoga internalizes the physical exercises (Zarrilli 1998, p. 85). Additionally, the training “instils in the practitioner a full 360-degree mode of embodied awareness” (Zarrilli 2020, p. 26).

6. Training Routines—Physical Postures and Mental States

As in previous centuries, today’s children begin their kaḷaripayaṯṯu training at an early age, usually when they are seven or nine years old. However, in ancient Kerala, kaḷaripayaṯṯu was taught (in the same way as the performing arts or traditional Indian sciences) according to the rules of the gurukula system. This teaching system required the students to live and train in the house of a gurukkal (Scharfe 2002, p. 280). A similar system of apprenticeship functioned in other places, such as Japan, where students who lived, trained and served in the master’s house were called uchi-deshi, (Jordan 2017, p. 194).

Traditionally, kaḷaripayaṯṯu is taught in three stages: meytāri, kolttāri, and ankatāri. Once enrolled in the kaḷari, adepts undergo rigorous training that is aimed at developing flexibility, general fitness, and endurance. The adepts gradually learn fighting stances, basic dodging, and blocks. Later, fighting techniques and kicks are practiced and the adepts also learn various methods of relaxation. Every kaḷari session begins with an oil self-massage, which helps the adepts to condition and strengthen their bodies before they start the proper exercises. John (2011, p. 17) observes also that some kaḷaris operate longer sessions of prārambha vyāyāma—preparatory acts that are carried out before training begins. These should include breathing exercises (prāṇāyāma), warm-up, and selected yoga postures (āsanas). At times, the adepts are told to perform the āsanas with their eyes closed, so that they can feel their posture and become more aware of their body. Thus, advanced students give the impression that the fluency with which they use particular techniques does not require force. Although this is obviously just an illusion, the finesse achieved after years of training comes from their ability to control muscle tension and from their general bodily awareness. As adepts become advanced, they execute the techniques more dynamically, interpreting individual movements as potential fighting techniques. The next step is to combine the previously learnt techniques into sequences of so-called forms (meytāri)—an element of training also practiced in other traditional martial arts, such as kung fu or karate (Choondal 1988, pp. 60–61). The speed and sequence of the techniques are determined by the trainer, who instructs the students with short commands (vaitari).9 All forms begin with an adept assuming a posture of an elephant, a stable fighting stance that is used later in self-defense. After a series of dynamic kicks, cuts and strikes, an adept practices lion, horse and wild boar positions. Importantly, they are required to perform all these techniques facing the “altar” (pūttaṟa) and, at the end of the training, they leave the kaḷari walking backwards from the pūttaṟa to the exit. Meytāri are most generally performed in groups, synchronously, and sometimes to the accompaniment of drums or other traditional Keralan instruments. Hence, as observed by Sunil Kumar, a gurukkal from CVN Kaḷari, the students are taught to feel the postures and attune their movements to the rhythm of the musical instruments or vaitari. He also points to the meditative qualities of the sequences of movements and bodily controlled exercises.

Hunter and Csikszentmihalyi (2000, p. 12) define flow as a state of experience, whereby a person is completely absorbed, exhilarated, and in control. Drawing on their definition, Pope (2019, p. 304) recognizes a flow state in the practice of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, whereby the students are engaged in grappling sessions and what he calls “flowing with the go”. The masters of kaḷaripayaṯṯu describe a similar mental state by saying that an adept’s body “becomes all eyes” (Zarrilli 1998, p. 202). In this state of total immersion in the act, the kaḷari artists are said to execute techniques without doubt or hesitation. Sieler (2013, p. 189) adds that practitioners of South Indian martial arts strive to achieve a state in which desires are extinguished but sense perceptions are sharpened. The warriors who achieved that state are said to have acted beyond fear, doubt, or anger. Additionally, as noted by Zarrilli (1998, pp. 203–13), they temporarily enter into a transcendent state of divine fury. Karolina Szwed, a kaḷari and yoga teacher, compares this state with the one she experiences while practicing a classical Odissi dance form, a traditional art that originated in the Hindu temples of Orissa:

I understand it as awareness. In [the] Odissi dance that I practice with my teacher Rekha Tandon, we try to be aware first of ourselves and then [the] space around, and lines of architecture of body and space in movements. During the dance practice or performance, we are all eyes but with different energy than [when we are] in [the] kaḷari; in dance it is with softness and openness. We share [the energy] and express ourselves to others; we remain open, with no harsh energy. It works in a similar way [to when we are in the kaḷari] and when [we perform] completely absorbed, it becomes something special and that speciality is something the audience can see and feel.10

Similarly, when I trained for kaḷaripayaṯṯu shows with a team of CVN Kaḷari, we developed a routine that involved repeating the techniques and expanding the awareness of space around us. At the time of a performance, one had to be fully focused on the techniques and hence we learnt to instinctively feel the stage, the space between us, and the audience.

The mental state “when body becomes eyes” is essential for the proper execution of any weapon technique. When an adept masters the meytāri, a gurukkal introduces them to the basic techniques of fighting with wooden weapons, which include a long staff (kettukari), a short stick (ceruvadi), and a dagger with a curved blade (otta). The otta is also used to teach pressure points called in Malayalam marmas (Sanskrit marman). The techniques of otta are slow, wave-like, sweeping, but also precise. Zarrilli (1998, p. 117) calls them “the culmination and epitome of psychophysiological training”, as they develop physical strength, help cultivate inner, subtle energies in the body, and show how to attack the marmas. The knowledge of vital spots is taught in South India for combative and therapeutic purposes, and thus the masters of the art are respected as both martial artists and healers (Sieler 2013, p. 175). My morning training in CVN Kaḷari usually ended at 8.00 and every time I left the training hall, I saw a long queue of patients waiting for our teacher. After the formal ending of kaḷaripayaṯṯu sessions, our gurukkal would close the door of the kaḷari and call the patients into his office. He used Āyurvedic massage and marma acupressure to treat their muscle injuries, bone displacements, and fractures.

However, during a duel, the masters of kaḷaripayaṯṯu would attack marma points with their hands or legs, while mentally chanting mantras.11 The mantras, Sanskrit monosyllabic formulas, are used to activate subtle energies and to transfer them to the spot, to paralyze an opponent. During one of my research travels to kaḷaris of Northern Kerala, I met gurukkals who admitted to having used mantras during their combat exercises. Some of these masters claimed that the mantras were derived from Paraśurāma Kalpasūtra, a Tantric treatise of Śrīvidyā Śāktism.12 This claim again connects kaḷaripayaṯṯu with Tantra through the reference to this authoritative ritual manual (Wilke 2012, p. 19). In Tantra, a mantra is believed to gain its potency (mantra-caitanya) when it is transmitted from a teacher to a student and should not be acquired in other way. Tantras warn that chanting mantras that have not been received in the traditional manner, but found in books, is a mortal sin equal to the killing of a Brahmin (Kulārṇavatantra 1999, verse 15.21, p.192). The same is true for mantras used in kaḷari—they should be given by a gurukkal to an adept during an initiation ceremony and not be revealed to the uninitiated. Nevertheless, the practice of mental chanting of various monosyllabic mantras during a fight is popular in various styles of kaḷaripayaṯṯu. The application of marmas in a real fight is also a widely discussed topic in Kerala. One may even find gurukkals who, like A.P. Prakasan of Kollam, claim to be able to attack opponents by merely looking at their marmas.

The marmas are also aimed at during combat with weapons. Thus, for instance, when I received the long staff from my gurukkal, he taught me to aim at marma points on the opponent’s forehead and then attack a point above their ankle. Similar instructions are received in the next stage of training called ankatāri—training with bladed weapons. A student begins their ankatāri by learning how to fight with a dagger and a sword. Finally, the adept trains with a flexible sword called an urumi—a weapon traditionally used by a master of kaḷaripayaṯṯu. There is a hypothesis that this weapon began to be used around the 13th or 14th century CE and was inspired by the European long sword (Kumaran 1993, pp. 133–35). In the final stages of kaḷaripayaṯṯu training, students also learn hand-to-hand combat (verum kai prayoga) and a healing massage (Zarrilli 1998, p. 115), which also require the knowledge of the marmas (see Appendix A Figure A2).

In his essay on the embodied spirituality of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, Pope (2019, p. 302) observes that by practicing martial arts, an adept not only hones their physical abilities, but recognizes the human instinct for violence and learns how to use it for spiritual development. Kaḷari adepts, on the other hand, not only learn to rely on their instincts but also expand their awareness of the space around and within them. They become more conscious of their bodies, the vital points, and the energetic centers, and learn how to attain a state of flow.

7. Kaḷari as a Temple of Spiritual Martial Arts—Ritualized Body and the Presence of Gods

As with the households of Nāyars and Brahmins, kaḷaris are often built close to a holy grove (kāvu) (Freeman 1999, p. 261). Generally, a kaḷari is a rectangular room with clearly marked spheres of the sacred and the profane. Adepts practice on a pounded earthen floor under a sloping roof that is sometimes made of palm leaves. When building kaḷaris, it is necessary to consult an astrologer and an expert in traditional architecture (taccaśāstram). The taccaśāstram prescribes that a building should be oriented to the north-west or north-east, which, according to popular belief, is to guarantee prosperity and scare away evil spirits. However, the right location is also believed to protect against accidents during training (Poduval 1948, p. 41).

Kaḷaris have always been built according to the principles of traditional sacred architecture and can be called Hindu temples of martial arts. Many temples in Kerala are called kṣetra—literally a field, but also a sacred space. Bhagavad-gītā, one of the important holy scriptures of Hinduism, uses this term to refer to both a battlefield and the body. In later traditions, the term kṣetra denotes a Hindu temple, body, consciousness and embodied emotions (Marjanovic 2002, p. 29). Hence, a ritual in a temple and a training of kaḷaripayaṯṯu can be called a practice of self-discovery: identification with, and worship of, the supreme, divine consciousness. More importantly, the term kṣetra indicates that the human body is a platform for all religious and transformative practices (Timalsina 2012, p. 74).

According to Hindu architecture, when building any edifice, one should first design a ground plan according to traditional diagrams representing the cosmos. These, in turn, are subdivided into squares ascribed to various deities. All these deities combined are visually represented as parts of the divine body of the Cosmic Person (vastupuruṣa) (Renard 1996, p. 75). The image of vastupuruṣa shows that a construction site is like a human being, with the weaknesses and strong points of the body. Likewise, the diagrams of deities mapped on the ground plan designate areas suitable for different purposes. The architect must therefore take these elements into consideration, when designing a building, so that it can “live a healthy life” (Salvini 2012, p. 39), as well as being a hospitable place for human residents. Thus, there are multiple associations between the body and the temple, or kaḷari. The physical structure of the building is based on the cosmic symmetry of the divine body and thus, an adept training in the kaḷari integrates the microcosm of their body with the divine structures of the macrocosm.

As in a Hindu temple, every action performed in the kaḷari is a ritual act. In CVN Kaḷari, the doors to the kaḷari open with a large doorstep that extends sideways into a platform for the audience. On entering the kaḷari, a student needs to raise their right foot over the doorstep first and then touch the ground with their right hand, invoking the divine patrons and asking for their protection. The training hall is a sacred space that houses altars and images of deities. Indeed, the rituals of invocation (āvāhana) and farewell (visarjana) of these deities are acts that mark the beginning and the end of a kaḷari day. In CVN Kaḷari, the door is opened by the gurukkals or a senior student, at 6.00 am. Then, after lighting the oil lamps, the adepts honor their masters, the gods, and the guardians of the kaḷari. Similarly, the evening training begins at 5.00 pm and ends with the lighting of the lamps (dīpārādhana).

The gods whose images adorn the Hindu kaḷaris are primarily Śiva, Godess Bhagavatī or Nāgabhagavatī (Queen of Serpents), Gaṇapati (The Elephant-headed Remover of Obstacles), and local guardian spirits. The idols of the gods guarding kaḷari, as with those in Hindu temples, require an installation ritual during which the deity is called to a previously prepared idol. In Hindu tradition, there is a distinction between an installation and an invocation rite, the first of which is a one-off act, and the second being a cyclically repeated rite, an element of every act of adoration (pūjā). During the rite of installation, a priest performs prāṇa-pratiṣṭhā, infusing the idols with vital forces. After this ritual, idols cease to function as mere symbols and become living representations of deities (Wheelock 1989, pp. 112–13), who oversee the practice and protect the adepts. Every pūjā, after the installation, includes chanting mantras, venerating the altars with handfuls of flowers, and summoning the divine and human gurus to grace the kaḷari with their presence (Pati 2010, p. 184). There is also a separate altar (guru-pīṭha), at which all the teachers of a given school are worshiped collectively (Zarrilli 1998, p. 305). While the entrance to the kaḷari faces east, the west wall has the most important altar—the pūttaṟa, which takes the form of seven-step raised platform (John 2011, p. 22). The importance of the pūttaṟa is explained in the following section. The corners of kaḷari contain conical representations of the spiritual guardians of directions (lokapālas) that delimit the sacred ground.

8. Kaḷari-Body—Metaphor and Mirror of the Tradition

Upon entering kaḷari, an adept prays and touches the pūttaṟa and then walks clockwise around the kaḷari hall, touching each lokapāla three times and, by doing so, invoking the guardians, and designating a sacred space for the training. Afterwards, they pray to the patron gods of the kaḷari, pay obeisance before the portraits of the former masters of the school, and finally before the current guru, who is seen as a representative of the entire tradition of teachers (guru-paramparā). The gurukkal blesses all the adepts who come to the training; his entry and exit from the kaḷari are accompanied by acts of reverence from the students, namely, touching the master’s feet. Adepts of kaḷaripayaṯṯu, a martial art deeply rooted in the Hindu tradition, believe that only through a guru are liberation and spiritual development possible. The teacher embodies the tradition and the revealed, spiritual gnosis. A gurukkal is, therefore, not only a teacher, but also a medium through whom spiritual power is transmitted. In his study on Tantric practices, Flood (1996, pp. 4–5) uses the now oft-quoted term “entextualisation of the body” to show that the body not only represents, but also becomes, the text, through the Tantric tradition being inscribed on it.13 Tantrics virtually recreate their body with mantras and, by doing so, transcend the constraints of physicality and the illusion of duality. Hence, the body becomes the vehicle for visualizing and conceptualizing scriptures and tradition. The deities, gurus, divine powers, and theological concepts are meditated upon and mapped onto the body through series of nyāsas, acts of ritual touching. Tantric adepts attempt to expand their subjectivity to experience (embody) different worlds and realities before attaining final liberation. The doctrines are internalized in nyāsa, and, by this act, one can realize identity with the divine and, thus, become liberated (Chakravarty and Marjanovic 2012, p. 153). In a similar fashion, the kaḷari adepts, after touching the feet of the gurukkal, pray by touching their own forehead and chest. With this gesture they accept the blessings and inscribe on their body the tradition represented by their gurukkal. The act of touching is an important gesture in many mystical traditions. Tantric body-related rituals not only divinize adepts but heal them by removing the illusion of duality from their mind. The touch grants them freedom from misconceptions (self-projected barriers) and freedom to act according to their divine nature (svātantryavāda) (Rastogi 2011, p. 90).

Kaḷaripayaṯṯu embraces many acts of entextualization and ritual touching. There are, for instance, various forms of elaborate salutations that entail ritual self-touching. The salute is performed, for example, at the start of important ceremonies. The salutation performed at CVN Kaḷari includes acts of veneration of the tradition by touching prescribed parts of body and a ceremonial touching of the ground (bhūmisparśa). As observed by the gurukkals, these movements are not merely physical exercises but acts of worship of the entire universe and of oneself as a microcosm. Further, the ceremonial touching of one’s body renders it divine and empowered in a similar fashion to the traditions of yoga and Tantra. In fact, the term Tantra is etymologically linked with the Sanskrit word tanu (“body”) and the suffix –tra indicates an instrument or a means of action (Flood 1996, p. 9). Hence, the body is the central instrument in many Tantric practices, aimed at attaining supernatural powers and salvation (Flood 1996). Similarly, the word “yoga” is derived from the Sanskrit root √yuj meaning “to unite” or “yoke”. Arguably, this traditional etymology points to the yogis’s ability to connect physical and spiritual dimensions in their practice and to unite with the consciousness of the universe (Fields 2001, pp. 85–86). Thus, it can be said that kaḷaripayaṯṯunot only has Tantric elements such as nyāsas or mantra chanting but it makes the body a vehicle for inner transformation, in the same way as Tantra. Conversely, kaḷaripayaṯṯuis “yogic” not only through similar postures or breathing exercises but because it unites physical and spiritual planes of activity. Similarly, Karolina Szwed calls yoga the spiritual core of kaḷaripayaṯṯu:

[yoga] is the connection between mind, body, breath and space, it shows us that the movement can be still. I often think, while observing people in kaḷari, yoga or dance training, that some people can execute a technique perfectly, but there is no life in it. I think they may not have a deeper spiritual relation with the art. Maybe it is something that yoga gives. My very personal idea is that kaḷari is my soul and odissi is my heart and yoga is the omnipresent energy.14

9. Spiritual and Physical Salutations

Every kaḷaripayaṯṯu performance or festival starts with an elaborate salutation that shows physical and spiritual aspects of training and which is often meant as an act of veneration for the tradition. According to the tradition of CVN Kaḷari, before performing the salute, an adept should first contemplate the pūttaṟa and touch the floor of the kaḷari. John (2011, p. 23) postulates that the act of touching the floor mimics the act of reverence toward the feet of gods and gurukkals. In Hindu tradition, divine feet are, in many ways, focal points of devotion. In temples, the feet of idols are often ritually washed and elaborately decorated with ankle-bells and flowers. Moreover, in some shrines, holy places, or home altars can be found images of divine feet or a guru’s sandals (Nugteren 2018). A kaḷari adept must also touch a gurukkal’s feet before starting any exercise, upon entering the kaḷari hall, or when asking for permission to leave a training session. On the other hand, the earth-touching gesture (bhūmisparśa) recalls one of the most common iconic images of Buddhism—“Buddha calling the earth to witness”. In this representation, Buddha, seated in a meditative posture, touches the earth with his right hand, invoking Pṛthivī, the goddess of the earth, as the witness of his enlightenment (Niharranjan 2002, p. 138). After touching the ground, the adept touches their own shoulders, paying respect to their masters, their divine guardians, and the tradition. As with the yogic Sun Salutation (Sūrya Namaskāra15), the kaḷari salutation is a flow sequence of several postures that requires adepts to synchronize their breath with the movements of their body. The performers of the kaḷari salutation gracefully change stance, imitating the steps of various animals, and pray while walking towards the pūttaṟa. After several steps, they jump and land on the ground, where they assume a meditative posture. Then, they make a gesture imitating plucking flowers from the ground and making an offering, scattering them all around. The gesture, performed slowly in a contemplative mood, is believed to energize the energy centers (cakras) of the body. According to the mystical physiology of yoga, the cakras are connected with channels (nāḍī) of subtle energy (prāṇa) that can be controlled with yogic exercises. Thus, it can be said that training in kaḷari develops both the physical (sthūla) and the subtle (sūkṣma) body (śarīra). The subtle body is composed of energy networks of micro channels and the aforementioned mystical cakras arranged along the central axis of the spinal cord. It is believed that the dormant energy (kuṇḍalinī śakti) of the human body lies in the lowest cakra, called mūlādhāra. Once awakened, kuṇḍalinī śakti flows through the central channeland renders the body divine and all-powerful (Flood 1996, p. 160). Thus, in esoteric traditions, the practice of yogic postures, prāṇāyāma, and the chanting of mantras are aimed at awakening and using the kuṇḍalinī.16 Similarly, the kaḷari practice of salutation involves slow movements and remaining for a long time in certain yogic postures, to invigorate the body and feel the flow of inner energy. The flow of the movements should be coordinated with breathing. In other styles of kaḷaripayaṯṯu, adepts sometimes perform more elaborate prāṇāyāmas during the salute and even use a Tantric practice of dig-bandhana (“binding the directions”), to secure the sacred space in which to perform the act. “Binding the directions” is a popular Tantric practice of invoking the guardians of the directions to fence out inimical forces. It is also a practice that reveals concerns for the dangers of the boundary between the inside and the outside, the sacred and the profane (White 2000, p. 31). Hence, dig-bandhana additionally secures an area within the sacred space for the adepts to fully focus on their spiritual practice. Therefore, it can be said that in kaḷaripayaṯṯu training, the body is enclosed and secured in several ritualized spaces (see Appendix A Figure A3).

According to Hindu esoteric traditions, the proper execution of all the above-mentioned elements of practice ultimately awakens kuṇḍalinī and consequently grants bodily enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of rebirth. According to haṭhayoga (Jacobsen 2005, pp. 18–19), the kuṇḍalinī śakti merges with the divine consciousness in the crown cakra (sahasrāra). At this moment, an adept is instantly liberated from the predicaments of the mundane world and united with the divine. In kaḷari, the Śakti Goddess is invoked in the pūttaṟa. However, on the pūttaṟa, the Śakti is visualized with a liṅga—the phallic symbol of Śiva. This emblem of Śiva is located at the top of a conical, seven-step structure resembling a coiled serpent. The symbolism of the pūttaṟa very clearly refers to the Tantric philosophy. In Tantric traditions, the feminine, creative energy permeates and animates the universe. The Tantric adepts believe that Śiva does nothing alone, but always through the inseparable Śakti, the infinite and all-creating power. The presentation of Śiva and Śakti together indicates the goal of spiritual practice: recognition of the ultimate unity of personal soul and god. In kaḷari, the serpentine structure of the pūttaṟa also indicates the aim of the practice—spiritual awakening and bodily empowerment. The pūttaṟa is a constant reminder that the aim of spiritual exercises is to realize the ultimate unity of micro and macrocosmic forces, individual self, and the divine. The steps of the pūttaṟa symbolize seven emanations of this deified creative power that play a role in the formation of successive cosmic cycles (Flood 1996, p. 186).17 The salutation starts and ends with an adept standing still and looking straight at the pūttaṟa, with their hands pressed together in a reverential gesture of añjali mudrā, that symbolizes the unity of spirit and body, divine and human realities. The whole sequence of movements is usually performed in the presence of a lighted lamp, indicating the goal of one’s spiritual journey—attainment of a higher awareness and enlightenment (John 2011, p. 23).

10. Conclusions

During my stay in C.V.N Kaḷari, I met many adepts and, curiously, each of them had a unique motivation for training there. There were children enrolled by their parents, martial artists training to learn new techniques, yogis interested in learning more dynamic forms of body control exercises, and many more. There were also actors, dancers, and performers who wished to find new forms of artistic expression.

However, as I have attempted to show in this article, the body, in traditional kaḷaripayaṯṯu courses, is not only to be trained but also divinized and textualized. The training aims at transforming the gross and subtle bodies and thus helping people to overcome their limitations.

Due to the efforts of masters like K. Narayanan Gurukkal and Kottakkal Kanaran Gurukkal, who popularized Indian martial arts, kaḷaripayaṯṯu training is now taking place in many countries. However, outside Kerala, it is generally taught in gyms, yoga halls, sport clubs, and fitness studios. When I started teaching kaḷaripayaṯṯu in Europe, in 2013, I was eager to teach it the way I had been taught—as a traditional martial art. However, as soon as I stepped into a training hall to meet my first batch of students, I realized that none of them had any experience in martial arts and hardly anyone had any interest in learning a fighting system. Most of them were yogis who had heard about kaḷari-yoga classes being held in gyms and were either interested in learning a more vigorous form of yoga, or were seeking spiritual practices. Thus, paradoxically, in modern times, kaḷaripayaṯṯu is better known as a form of spiritual practice (kaḷari-vidyā) than a martial art. On the other hand, by performing the prescribed movements, the modern adept is still embedded and embodied within a narrative structure of the “kaḷaripayaṯṯu legend”, concerning the traditional martial art that was practiced by ancient Keralan heroes. Thus, the bodies of kaḷaripayaṯṯuadepts become indexes of Hindu, esoteric doctrines, as well as functioning as metaphors and mirrors of the kaḷari traditions.

With regard to traditional training, the present study has attempted to show how the body is ritualized in kaḷari. A person entering a kaḷari, and following all the rules of the training, synchronizes their body with the body of the building and the ritual syntax. The structure of kaḷari buildings designates and superimposes sacred spaces. Thus, to enter the training hall means to leave the ordinariness of life and enter a sphere of sacrum. Victor Turner suggests that ritual is “a liminal mode of being, a threshold state that is momentary and delimited”. He terms this threshold “anti-structure” and the statis that precedes and follows it “structure” (Abrahams 1969, pp. ix–x). The key characteristic of anti-structure is its ephemerality: when the ritual ends, the adept goes back to their reality, though the experience of wonder stays with them. Tulasi (2018, p. 4) observes that everyday ritual practices of Hindu devotees are aligned with the feeling of wonder. Every ritual act is, for them, an attempt to re-experience the wonder, the feeling of the sacred in ordinariness of life. In the same way, every training session in a kaḷari is an attempt to find the sacred space within its walls and within oneself. The embodied spirituality of the kaḷari is a dynamic, rather than static, experience of the sacred. The duels, sequences of yogic exercises, and ritualized salutations are all tools that allow one to find the spiritual dimensions of movement and stillness.

Funding

The research received funding from Hainan University, research fund RZ2100001144.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The interior of CVN Kaḷari Nadakkavu (author).

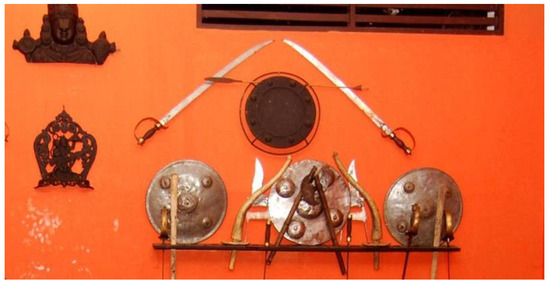

Figure A2.

The weapons in CVN Kaḷari Nadakkavu (author).

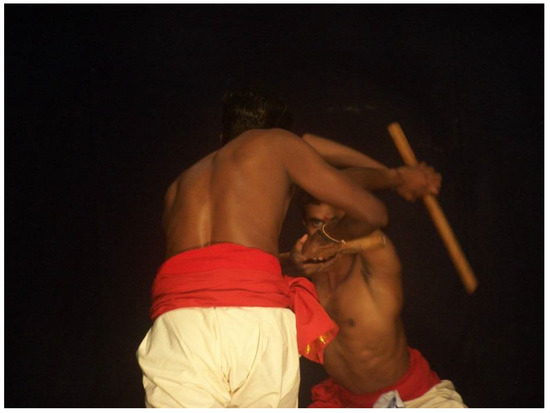

Figure A3.

Kaḷaripayaṯṯu performance in Calicut (author).

Notes

| 1 | I am especially grateful to Karolina Szwed, Sunil Nair Gurukkal and Sasidharan P.K for their insightful remarks on, and help with, this research paper. |

| 2 | Kaḷaripayaṯṯu has been researched by a scholar-practitioner Zarrilli (1998, 2005) and several Keralan gurukkals, for instance John (2011); Nair (2014) and Vijayakumar (2017). Pati (2010) and Choondal (1988) indicated also spiritual aspects of the kaḷaripayaṯṯu training. Moreover, Tarabout (1986); Pasty-Abdul Wahid (2020) and other anthropologists point to the importance of kaḷari for Keralan culture. |

| 3 | Kaḷari-vidyā is a compound composed out of a Malayalam word kaḷari and a Sanskrit term vidyā (knowledge). It is, therefore, not a Malayalam term but a hybrid form that could have been introduced with an advent of Sanskrit culture. On a complex problem of Sanskritization see, for instance, (Staal 1963). |

| 4 | Sasidharan, P.K. private communication, January 2021. |

| 5 | Fields (2001, p. 83) calls the classical yoga system of Patañjali “a comprehensive system of psychophysical healing and religious liberation” that leads an adept towards enlightened embodiment. |

| 6 | prāṇāyāma literally means regulation of the flow of prāṇa (vital energy). |

| 7 | Six-limbed yoga (consisting of prāṇāyāma pratyāhāra dhāraṇā tarka dhyāna and samādhi) is mentioned in Maitrāyaṇīya and Amṛtanāda Upaniṣad and Kālacakra of Buddhism.(Grönbold 1996). On the Six Limbs of yoga in the Tantric system of Monistic Kashmirian Śaiva traditions, see Vasudeva (2004). Conversely, GheraṇḍaSamhita, one of the oldest yogic treatises, promotes a sevenfold path of yoga (Mallinson 2004). |

| 8 | Notably, Singh (1991) titled his translation of a Tantric text Vijñāna Bhairava “The Yoga of Delight, Wonder, and Astonishment”. The text explains techniques of bhāvana in Śaiva Tantra of Kashmir that lead to the experience of a union with all-pervasive, divine consciousness. To experience this, a yogi should turn away from the external reality and search for inner bliss. Thus, Muller-Ortega (1991, p. xiv) explains, the yoga of Vijñāna Bhairava is “wonder-filled, it is the yoga of astonishment—camatkāra”. |

| 9 | Vaitari is an important aspect of CVN Kaḷari routines, but does not occur, for example, in the southern varieties of kaḷaripayyattu. |

| 10 | Karolina Szwed, private communication, January 2021. |

| 11 | Many masters of kaḷaripayyattu and the Tamil martial art varmakkalai believe that attacking marmas is a technique that should be used only in self-defense (Sieler 2013, p. 198). |

| 12 | Sasidharan P.K., private communication, 2011. |

| 13 | Similarly, Csordas (1999, p. 145) observes that embodiment is like a text “an indeterminate methodological field defined by perceptual experience and by mode of presence and engagement in the world”. |

| 14 | Karolina Szwed, private communication, January 2021. |

| 15 | A well-known yogic routine of Sun Salutations (sūryanamaskāra) is a relatively modern addition to yogic practices. It was, in fact, only introduced into the yogic regimen in the twentieth century. Earlier yogic texts describe various reverential acts and prostrations (namaskāras and praṇāmas) but these are not considered techniques of yoga and none of them are performed for the sun (Mallinson and Singleton 2016). |

| 16 | Prāṇāyāma is also utilized by kaḷaripayyattu masters to enhance their fighting techniques and render their bodies invulnerable. On one occasion, I was invited to a kaḷaripayyattu workshop organized by a master of the Tulunadan style. The workshop ended with a demonstration of arjuna vadivu, a particular fighting stance that allows a master to defend all attacks. First, the gurukkal invited volunteers to try to push him off the stage. After several attempts, a group of five or six men resigned and admitted that could not move him. Then, the gurukkal asked for more volunteers to attack him anyway they liked. Again, several attendees tried to kick or punch his body, but he remained unimpressed and blocked most of their attacks still standing in arjuna vadivu. In the end, the master explained that his unique skills were a result of a life-long practice of prāṇāyāma. He claimed that by moving prāṇā to various parts of his body, he could render them resistant to the attacks. He also used prāṇāyāma to “root“ himself to the ground and make his body immovable. Zarrilli (1998, p. 148) describes similar practices of a Vasu gurukkal, who claimed that his praṇava prāṇāyāma performed continuously for 41 days gives one special powers and invincibility. |

| 17 | Various gurukkals add their own interpretation regarding the symbolism of the pūttaṟa. For instance, Zarrilli (1998, pp. 71–72) notes that a master from the Central Kerala ascribed each step to different deities, which might grant special powers to those who achieved a particular state of enlightenment. John (2011, p. 10) identifies the seven steps of the pūttaṟa with seven dhātus, basic tissue elements mentioned in Āyurvedic sources (Fields 2001, p. 43). |

References

- Abrahams, Roger. 1969. Foreword to the Aldine Paperback Edition. In The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Edited by Turner Victor. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, Joseph. 2004. Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, Duarte. 1995. A Description of Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the Beginning of Sixteenth Century. Translated by Henry Stanley. Madras: Asian Educational Services. [Google Scholar]

- Bayly, Susan. 1984. Hindu Kingship and the Origin of Community: Religion, State and Society in Kerala, 1750–1850. Modern Asian Studies 18: 177–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benard, Elisabeth. 1999. Chinnamasta: The Aweful Buddhist and Hindu Tantric Goddess. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, Loriliai. 2007. Renowned Goddess of Desire: Women, Sex, and Speech in Tantra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Douglas. 1992. Auspicious Wisdom: The Texts and Traditions of Śrīvidyā Śākta Tantrism in South India. New York: The University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty, Hemendra Nath, and Boris Marjanovic. 2012. Tantrasāra of Abhinavagupta. New Delhi: Rudra Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrababu, B., and L. Thilagavathi. 2009. Woman, Her History and Her Struggle for Emancipation. New Delhi: Bharathi Puthakalayam. [Google Scholar]

- Choondal, Chummar. 1988. Towards Performance: Studies in Folk Performance, MUSIC, Martial Arts, and Tribal Culture. Trichur: Kerala Folklore Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Csordas, Thomas. 1999. Embodiment and Cultural Phenomenology. In Perspectives on Embodiment. The Intersections of Nature and Culture. Edited by Gail Weiss and Honi Fern Haber. New York: Routledge, pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Jorge. 2008. What does it mean to live a fully embodied spiritual life? International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 27: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, Gregory. 2001. Religious Therapeutic: Body and Health in Yoga, Ayurveda, and Tantra. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, Gavin. 1996. The Tantric Body: The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion. New York: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Rich. 1999. Gods, Groves and the Culture of Nature in Kerala. Modern Asian Studies 33: 257–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, Kathleen. 1952. Changing Kinship Usages in the Setting of Political and Economic Change Among the Nayars of Malabar. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 82: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönbold, Günter. 1996. The Yoga of Six Limbs: An Introduction to the History of Ṣaḍaṅgayoga. Translated by Robert L. Hutwohl. Mexico: Spirit of the Sun Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Sanjukta. 1992. Yoga and Antaryāga in Pāñcarātra. In Ritual and Speculation in Early Tantrism: Studies in Honor of Andre Padoux. Edited by Goudriaan Teun. New Delhi: Satguru Publication, pp. 175–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gurukkal, Rajan. 1992. The Kerala Temple and Early Medieval Agrarian System. Sukupuram: Vallathol Vidyapeetham. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Jeremy, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. The Phenomenology of Body-Mind: The Contrasting Cases of Flow in Sports and Contemplation. Anthropology of Consciousness 11: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, Knut. 2005. Yoga Traditions. In Theory and Practice of Yoga. Edited by Jacobsen Knut. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- John, Shaji. 2011. Kaḷaripayattu: The Martial and Healing Art of Kerala. Kottayam: Koovackal Kappumthala Po Muttuchira. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Brenda. 2017. From Technique to Art. In Copying the Master and Stealing His Secrets: Talent and Training in Japanese Painting. Edited by Jordan Brenda and Weston Victoria. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 178–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kulārṇavatantra. Avalon, Arthur, and Tārānātha Vidyāratna, eds. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Kumaran, Vijayan. 1993. Military Systems of Kerala. Ph.D. thesis, University of Calicut, Malappuram, India. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen, David. 2006. Who Invented Hinduism? New Delhi: Yoda Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James, and Mark Singleton. 2016. Roots of Yoga. Penguin: Kindle edition. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2004. The Gheranda Samhita: The Original Sanskrit and an English. Translated by James Mallinson. Woodstock: YogaVidya.com. [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic, Boris. 2002. Abhinavagupta’s Commentary on Bhagavadita (Gītārtha Saṃgraha). New Delhi: Indica. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Ian. 2007. Bodily practice, performance art, competitive sport: A critique of kaḷaripayaṯṯu, the martial art of Kerala. Contributions to Indian Sociology 41: 143–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Ortega, Paul. 1991. Foreword. In The Yoga of Delight, Wonder, and Astonishment: A Translation of Vijnana Bhairava with an Introduction and Notes by Jaideva Singh. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. xi–xxii. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, Chirakkal Sreedharan. 2014. Kalarippayattu: The Complete Guide to Kerala’s Ancient Martial Art. New Delhi: Westland. [Google Scholar]

- Niharranjan, Ray. 2002. An Introduction to the Study of Theravada Buddhism in Burma. A Study in Indo-Burmese Historical and Cultural Relations from the Earliest Times to the British Conques. Bangkok: Orchid Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nugteren, Albertina. 2018. Bare Feet and Sacred Ground: “Viṣṇu Was Here”. Religions 9: 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasty-Abdul Wahid, Marianne. 2020. Bloodthirsty, or Not, that Is the Question: An Ethnography-Based Discussion of Bhadrakāḷi’s Use of Violence in Popular Worship, Ritual Performing Arts and Narratives in Central Kerala (South India). Religions 11: 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, George. 2010. Kaḷari and Kaḷarippayattu of Kerala, South India: Nexus of the celestial, the corporeal, and the terrestrial. Contemporary South Asia 18: 175–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, Elamkulam. 1970. Studies in Kerala History. Kottayam: National Book Stall. [Google Scholar]

- Poduval, R. Vasudeva. 1948. Architecture in Travancore. In The Arts and crafts of Travancore. Edited by Stella Kramrich, R. Vasudeva Poduval and James Henry Cousins. Madras: The Royal India Society and Government of Travancore, pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Mick. 2019. Flow with the go: Brazilian Jiu Jitsu as embodied spirituality. Practical Theology 12: 301–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, Navjivan. 1993. The Yogic Disciplines in the Monistic Śaiva Tantric Traditions of Kashmir: Threefold, Fourfold, and Six-Limbed. In Ritual and Speculation in Early Tantrism: Studies in Honor of Andre Padoux. Edited by Goudriaan Teun. New Delhi: Sri Sat Guru Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, Navjivan. 2011. Kāśmīra kī Śaiva Saṃskṛti me kul aur Kram-Mat. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld. [Google Scholar]

- Renard, John. 1996. Comparative Religious Architecture: Islamic and Hindu Ritual Space. Religion and the Arts 1: 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvini, Mattia. 2012. The Samarāṅganasūtradhāra: Themes and Context for the Science of Vāstu. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 22: 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbacker, Stuart. 2012. Power and Meaning in the Yogasūtra of Patañjali. In Yoga Powers Extraordinary Capacities Attained Through Meditation and Concentration. Edited by Jacobsen Knut. Leiden: Brill, pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe, Harmut. 2002. Education in Ancient India. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sieler, Roman. 2013. Kaḷari and Vaittiyacālai: Medicine and Martial Arts Intertwined. Asian Medicine 7: 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Jaideva. 1991. The Yoga of Delight, Wonder, and Astonishment: A Translation of Vijnana Bhairava with an Introduction and Notes by Jaideva Singh. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Staal, Frits. 1963. Sanskrit and Sanskritization. The Journal of Asian Studies 22: 261–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabout, Gilles. 1986. Sacrifier et Donner à voir en Pays Malabar. Les fêtes de Temple au Kerala (Inde du Sud): Etude anthropologique. Paris: Ecole Française d’Extrême Orient, vol. CXLVII. [Google Scholar]

- Timalsina, Stanweshar. 2012. Reconstructing the Tantric Body: Elements of the Symbolism of Body in the Monistic Kaula and Trika Tantric Traditions. International Journal of Hindu Studies 16: 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trousdale, Ann. 2013. Embodied spirituality. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 18: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulasi, Srinivas. 2018. The Cow in the Elevator: An Anthropology of Wonder. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ulland, Dagfinn. 2012. Embodied Spirituality. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 34: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, Somdeva. 2004. The Yoga of the Mālinīvijayottaratantra. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar, Ke. 2017. Kalarippayattu—Keralathinte Sakthiyum Soundaryavum. Trivandrum: The State Institute of Language. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock, Wade. 1989. Mantra in Vedic and Tantric ritual. In Understanding Mantras. Edited by Alper Harvey. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. 96–122. [Google Scholar]

- White, David. 2000. Introduction. In Tantra in Practice. Edited by White Gordon. Princeton: Princeton University, pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- White, David. 2012. Introduction. In Yoga in Practice. Edited by White Gordon. Princeton: Princeton University, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Annette. 2012. Recoding the Natural and Animating the Imaginary. Kaula Body-practices in the Paraśurāma-Kalpasūtra, Ritual Transfers, and the Politics of Representation. In Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and Beyond. Edited by István Keul. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 19–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrilli, Philip. 1998. When the Body Becomes All Eyes: Paradigms, Discourses and Practices of Power in Kaḷarippayattu, a South Indian Martial Art. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrilli, Philip. 2005. ‘Kaḷarippayattu is Eighty Percent Mental and Only the Remainder is Physical’: Power, Agency and Self in a South Asian Martial Art. In Subaltern Sports: Politics and Sports in South Asia. Edited by Mills James. London: Anthem Press, pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrilli, Philip. 2020. Toward) A Phenomenology of Acting. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).