Abstract

Shamanship is a thing-ish practice. Early missionary observers in Korea noted that features of the landscape, quotidian objects, and specialized paraphernalia figure in the work of shamans (mansin) and in popular religious practice more generally. Subsequent ethnographers observed similar engagements with numinous things, from mountains to painted images, things vested with the presence of soul stuff (yŏng). Should this be considered “animism” as the term is being rethought in anthropological discourse today? Should we consider shamanic materiality in Korea as one more ontological challenge to the nature/culture divide? Drawing on existing ethnography and her own fieldwork, the author examines the (far from uniform) premises that govern the deployment of material things in Korean shaman practice. She argues that while the question of “animism” opens a deeper inquiry into things that have been described but not well-analyzed, the term must be used with clarity, precision, and caution. Most of the material she describes becomes sacred through acts of human agency, revealing an ontology of mobile, mutable spirits who are inducted into or appropriate objects. Some of these things are quotidian, some produced for religious use, and even the presence of gods in landscapes can be affected by human agency. These qualities enable the adaptability of shaman practices in a much transformed and highly commercialized South Korea.

1. Introduction

In early ethnology, shamanship was a phenomenon bursting with things—robes, rattles, and drums—collected, documented, and taken back to museums. The emergence of modern socio-cultural anthropology has been described as an enterprise more immediately concerned with the intangible products of the human social imagination, things that become legible through extended participant observation and with some measure of linguistic fluency. Materiality returned to anthropology over the last few decades with parallel developments in religious studies, art history, social history, and other linked fields. In a manner thoroughly consistent with the core premises of socio-cultural anthropology, we are now encouraged to regard objects, at least some objects, as agentive actors in their own right (Gell 1998; Henare et al. 2007). As a consequence, we are reading more about the roles that different objects play in shamanship, objects that become registers of presence in their own right (e.g., Bacigalupo 2016; Desjarlais 1996; Kendall and Yang 2015; Pedersen 2007; Santos-Granero 2009b), and even new things, such as a vacuum cleaner, reveal uncanny possibilities (Humphrey 1999). The question of shamanic materiality is almost inevitably intertwined with the return of “animism” to the anthropological conversation as an ontological challenge to the nature/culture divide. Much of this writing emerges from studies of Amazonian people where souls or energies are not only resident inside people, animals, and things but are shared and passed between them (Descola [2004] 2014; Viveiros de Castro 2004; Santos-Granero 2009a). Other animistic ontologies have been productively discussed in other places (Pedersen 2007, 2011). Ingold broadly characterizes an indigenous animistic perception of the world and all it contains as in a constant state of rebirth (Ingold 2006) and, for Harvey, it is “the widespread indigenous and increasingly popular ‘alternative’ understanding that humans share this world with a wide range of persons, only some of whom are human” (Harvey 2006, p. xi). The new animism, thus, inverts “a long-established convention” [where] animism is a system of belief that imputes life or spirit to things that are truly inert” (Ingold 2006, p. 9). What was “primitive” and mistaken is now “indigenous” and a salutatory worldview for our troubled planet. I have worked with shamans in Korea, a state society with a long and literate history. In the East and Southeast Asian world, many shamanic and mediumistic traditions and their associated iconographies evoke and, in some instances, were historically associated with courts and kings through long, if fragmented histories (Blacker 1975; Brac de la Perrière 1989; Childs-Johnson 1995; Michael 2015; Sukhu 2012). These are not the shamans who came to anthropology via ethnographies of hunters and herders, not “indigenous” as the term is usually deployed. The powers Korean shamans manifest usually assume human, not animal, form and appear garbed in the accouterments of temporal power, if only the power to disrupt and demand in domestic space. Moreover, whatever their speculative pedigrees, shamans in East and Southeast Asian places are also emphatically contemporary. Korean shamans today inhabit a commoditized lifeworld where the imagery of “raising a tall building” is a prognostication of good fortune and a spirit Official governs the fortune of a family car (Kendall 2009).1

The notion of “anima” appears in passing in a now-classic essay by the renowned Korean folklorist Yim Sŏk-jay. Yim wrote to distinguish those practitioners called “mu” or “mudang” (including the mansin of my descriptions) from a more motley assortment of exorcists and inspirational diviners on the one hand, and from the “shamans” of Mircea Eliade’s generalization on the other (Yim 1970; Eliade [1951] 1970). The extremely well-read Yim describes a multi-faceted polytheism where concepts like “anima,” “mana,” and “magic” (chusul) may have, just possibly, been an ancient influence, but Yim is at pains to assert how Korean spirits, the forms they take, and the work that they do stem from the lived experience of rural Korea as it was there to be studied at the time of his writing (p. 77). While Yim’s intention was to establish a clear and accurate sense of Korean “mudang,” I would like to think that he would have accepted the characterization of “shaman” used by scholars today, an understanding that has been broadened in part by descriptions of Korean practice (Atkinson 1992; Vitebsky 1995). In the spirit of Yim’s clarifying inquiry, “animism” in its 21st-century sense requires a careful examination with respect to the materiality of Korean shamanic practices, the transmissibility of soul stuff, and the mutability of phenomena. In Korea, what, exactly, would we be talking about?

2. “Animism” in Korea?

Early missionary observers, some of whom knew their Tylor and Frazer, encountered the religious materiality of Korean popular religion with intellectual curiosity, aniconic disgust, and, just possibly, the frisson of a call to arms against “demons.” George Heber Jones, writing about what he characterized as the “spirit worship of the Koreans,” describes a world riddled and tormented by perceptions of unseen forces said to inhabit things: “they hallow to themselves certain material objects, such as sheets of paper, calabashes, whisks of straw, earthen pots, garments, heaps of stones, trees, rocks and springs, and that many of the objects thus sanctified become genuine fetiches (sic.), endowed with the supernatural attributes of the being they represent, this being especially true in the case of portraits sacred to demons” (Jones 1902, p. 40). Jones calls these practices “fetichism”: “Spirit and fetich become so identified in the mind of the devotee that it is hard to determine which has the greater ascendancy, but it is certain that the fetiches, however decayed and filthy they may become from age, are still very sacred and the Korean dreads to show them violence (41) […] He has no refuge from them even in his own house for there they are plastered into or pinned on the walls or tied to the beams” (58).

For Jones and his contemporaries writing in Korea and other places, as for the Victorian anthropologists whom some of them were reading, animistic practices constituted “a vast undergrowth in the religious world through which the student must force his way with axe and torch. […] it is prehistoric, document less and without system, and it lacks all articulation which would permit the religious anatomist to dissect and classify it. […] If we attempt to trace its origin historically, we get lost” (Jones 1902, pp. 40–41). This sense of something stratigraphically underneath and inchoate is implicit in many discussions of popular religion throughout Asia, particularly those aspects that cannot be readily conjoined to so-called world religions and are therefore attached to “a single rubric signifying ‘beginning,’ ‘incipient,’ or ‘elementary’” in Masuzawa’s exegesis (Masuzawa 2005, pp. 4–5). Thus, the anthropologist Cornelius Osgood wrote that “For the Koreans, Shamanism is still an essence of their culture which was distilled in the subarctic night thousands of years before they even reached the Peninsula” (Osgood 1951, p. 217). Invocations of primordialism also appear in contemporary discussions of Korean shamanism, proclaimed by scholars and increasingly by mansin themselves as a tenet of cultural nationalism, an otherwise unprovable commonsense.2 It will be necessary to set mythologized pasts aside, at least for the moment, in order to evaluate the possible utility of a 21st-century approach to the question of “animism” in Korea.

While Jones had his own missionary agenda and a now-archaic vocabulary, he was not a bad observer. His list of “hallowed objects” or “fetiches” includes objects and practices that would be described in greater detail in subsequent writings, both missionary and academic, Korean and foreign. The question becomes: what did these things mean to those who used them? In what sense were they regarded as “hallowed?” and do they, in this condition, belong in a reconceived discussion of “animism” wherein both matter and soul stuff are recognized as mobile? For heuristic purposes, I will group Jones’s itemization of spirited materiality into three different bundles of things. On the one hand—and particularly tempting for a discussion of “animism”—there are the heaps of stones, trees, rocks, and springs whose resident deities the mansin invoke for inspiration. Then there are objects of human manufacture, ordinary things transformed into something more than ordinary through acts of human agency, the sheets of paper, calabashes, whisks of straw, earthen pots, and garments. These enter the discussion either as placings for spirit presence or as their vehicles, a not insignificant distinction. Then, there is the abundant materiality of the shaman’s own shrine, less abundant in Jones’ day—incense pots, candle holders, vessels of rice, brass mirrors, and all manner of offerings. Here too, stored under the altar, are containers of bright costumes and props that mansin use when, with voice and body, they make the gods a performative presence during a kut, their signature ritual. Presiding over the shrine space are what Jones characterized as portraits sacred to demons. Nearly everything in this final bundle had prior lives as objects of commerce and, today, most of them are mass-produced. Inside the shrine, they become more than ordinary, but to different degrees of “more than ordinary.” Everything in my three heuristic bundles, and some that Jones never imagined, such as a television set, become media or conduits in relationships with entities otherwise unseen. Let me deal with each of the three bundles in turn.

2.1. Heaps of Stones, Trees, Rocks and Springs…

The veneration of spiritually empowered sites in East Asia is generally assumed to predate iconic representations of buddhas or other divinity (Wong 2021, p. 2). Numinous features of the landscape—a rock, a tree, a mountain—have been celebrated in Korean communities as sites of divine presence sometimes marked with a community shrine and a periodic celebration of the resident tutelary. Dragon Kings inhabiting significant bodies of water have been similarly feted. Old Seoul shamans relate that for a successful induction into their number, a prospective mansin would hold her initiation kut at the Kuksadang on Inwang Mountain and receive a flow of inspiration standing in front of the Sŏnbawi, a contoured double-headed karst boulder.3 My primary mansin conversation partner, Yonngsu’s Mother, described how, as an intimation of her calling, she would be drawn to the rock to bow and rub her hands in compulsive supplication. The Sŏnbawi and some other renowned rock sites are also efficacious places to offer fertility prayers. Smaller rocks are more portable sources of inspiration. David Kim describes a diviner who has built her practice around a stone, now installed in her shrine, that revealed its numinous qualities through a vision of radiant light (Kim 2015).

Celebrations at village shrine trees and at shrines on mountains or beside bodies of water were frequently noted in early 20th-century accounts (e.g., Clark [1932] 1961; Jones 1902) and were still in evidence when the Ministry of Culture, Bureau of Cultural Properties Preservation conducted an ambitious province-by-province survey of folk practices in the 1960s and 1970s (MCBCPP 1969–1978, cum. vols.). In contemporary and nearly completely urbanized South Korea, these community kut are hard to find, save where they have been maintained, with outside encouragement, as cultural heritage. But certain features of the landscape, particularly mountain landscapes, remain active sites of shaman practice where mansin seek out a concentration of powerful gods in spaces conducive to visions, enhancing their own store of inspiration or “bright energy” (myŏnggi) without which a mansin cannot practice. Initiates might spend several days at an isolated mountain site seeking visions that will confirm and empower their calling. Senior shamans return periodically in order to, in the words of one old shaman, “recharge their batteries,” revivify their store of inspiration. I have described elsewhere (Kendall 2009, pp. 184–203) the periodic mountain pilgrimages that mansin make to potent, literally “bright” mountains (myŏng san) and their prayers and offerings on mountain peaks, at springs, and in front of guardian shrine trees along the way (Figure 1). These journeys are now more frequent and far-flung than they were in the 1970s owing to better roads, more ubiquitous vehicles, and even international travel to experience Mount Paektu from the Chinese side of the North Korean border. In South Korea today, the lower slopes of potent mountains have come to be covered with kuttang, commercial spaces rented for kut that can no longer be performed in dense urban residential areas.

Figure 1.

A mansin on Kampak Mountain purifies the site of a sacred spring, 1977. Photograph by author.

Something very like an animistic ontology seems to be at play in these consequential human engagements with entities and energies resident in the landscape, but the substance of this engagement must be cautiously clarified. Mountains, bodies of water, and trees are not gods; they are inhabited by them; a particular mountain god is sovereign on a particular mountain. Likewise, in their discussion of shaman practices in and around the city of Incheon, Kwon and Park (2018) describe the bodies of water as the domains of different divine generals, including the American General MacArthur. The relative potency of a mountain site is mapped not only by the anticipation of gods but by a scheme of potent energy (ki, Chinese qi) in veins (maek) that run through and charge the landscape. This geomancy (p’ungsu, Chinese: fengshui) encourages a concentration of potent gods to descend from the sky onto high mountains and transmit their inspiration to a shaman. Good geomancy is now sometimes offered as a marketing point for a particular mountain kuttang. However ancient the notion of a charged mountain-scape (and this is unknowable), its basic principles came to Korea via scholarly writing and learned practice as a complex technology of person, time, and place that was subsequently adapted to local practice (Yoon 2006). The five-element (ohaeng) cosmology that undergirds geomancy informs divination, traditional medicine, and most ritual practices. It ascribes relative energies to most matter, stone, wood, metal, and the human body as it interacts with the shifting properties of cyclical time and seasonality. This is a world in constant transformation, in Ingold’s sense, but far from primeval or even indigenous. Within this scheme, the energizing potential of a mountain landscape and the presence of powerful gods on mountains is mutable. Energy veins can be altered by changes in the physical landscape, cut or disrupted by roads or other construction. Shamans claim that a mountain’s potency is further diminished by environmental degradation in the form of real estate development and increased recreational access. Because high gods are less likely to descend with the same force onto a stripped and noisy mountain-scape, inspiration does not come so easily on the mountain as it is reported to have done in the past (Kendall 2009, pp. xvii–xviii). The mobility of gods and of a broader universe of spirits is a recurring motif in this discussion.

2.2. Sheets of Paper, Calabashes, Whisks of Straw, Earthen Pots, Garments

Jones notes how some of these things, objects of human manufacture transformed by human agency, “become genuine fetiches, endowed with the supernatural attributes of the being they represent” (Jones 1902, p. 40). The sheets of paper he references are suspended as placings for different house gods, notably, but not exclusively, Sŏngju, the House Lord (Jones 1902, p. 54; Clark [1932] 1961, p. 204); Guillemoz 1983, p. 170, 176, Pls. 12 and 13; Kendall 1985, p. 118). Central to both Clark’s and my account is the notion that the House Lord periodically leaves—because of an accretion of pollutions from births and deaths—and must be graphically inducted back into the purified house through the medium of a shaking pine branch.

Earthen jars (tok, hangari, tanji) filled with grain as placings for different household gods, ancestors, and other family dead appear in many accounts as do small covered baskets and pouches (Akiba 1957, pp. 102–4; Clark [1932] 1961, p. 206; Guillemoz 1983, p. 119, 150, Pls. 9, 10; MCBCPP 1969–1978, “Chŏlla Namdo”, 258–59; 1971 “Chŏlla Pukto”, 94, 96; 1972 “Kyŏngsang Namdo”, 185, 186; 1974 “Kyŏngsang Pukto”, 157–163, 1975; “Ch’ungch’ŏng Namdo”, 174, 1976; “Ch’ungch’ŏng Pukto”, 103, 104; 1978 “Kyŏnggido”, 90–91). Baskets or jars holding bits of cloth or clothing for ancestors or other unquiet dead—including one mansin’s spurned suitor who had committed suicide—had, by the time of my fieldwork, been replaced by small cardboard boxes from the tailor’s shop. I encountered the “calabash” as a gourd dipper filled with rice grain and held in the hands of an infertile woman while a chanting mansin induced the Birth Grandmother (Samsin Halmŏni) into the womb-like vessel (Figure 2). The woman’s hands should shake with the agitation of the descended spirit. She would be instructed to carry the grain-filled gourd home, hoping that the Grandmother would be present and a safe birth forthcoming (MCBCPP 1971, “Chŏlla Pukto”, p. 92; Kendall 1977).

Figure 2.

This gourd dipper (pakaji) was filled with rice as a fertility charm for the author, 1984). By the 1970s, dippers for domestic use were made of plastic in this shape. Photograph by Homer Williams.

Korean folklorists who combed the countryside in the 1960s and 1970s on behalf of the MCBCPP noted that these material placings were disappearing. Their survey forms included the category pongan sinch’e, literally “the material body-form of the god’s enshrinement.” Their interviews reveal variations within a single village between households where a particular god had a dedicated container, basket, pouch, or signifying strip of paper and households where identical offerings were made in the same locations but without a material marker of presence. During my fieldwork in rural Kyŏnggi Province in 1977 and 1978, I saw housewives set down offerings for the household gods in places appropriate to each god, but only once did I encounter a jar meant to contain a deity. During a kut in a rural home, a mansin assisted the housewife in emptying out old grain, filling the jar with new grain, and setting it on the veranda as a placing for a Talking Female Official (Malhanŭn Yŏ Taegam), the source of this family’s good fortune (Kendall 1985, pp. 113–24). In the mansins’ view, the gods are present in all houses; this particular placing implied a particularly active, demanding presence requiring special attention and respect.

The jars and baskets, then, are containers installed and animated with a presence, much as a statue in a temple is ritually invested with the presence of a buddha; albeit the jars and baskets are rustic forms that would otherwise have had quotidian lives (Figure 3). Prior to their conscription as containers for gods, they had shown no spontaneous indications of uncanny presence. In Peter Pels’ invocation of Tylor, they were not fetishes—objects of innately extraordinary matter—but animated objects; a spirit/soul/god/energy had been inducted into matter (Pels 1998, p. 94). Animation in this context is an action verb describing an intentional performance by a human agent, and because animation can also describe the work of a puppeteer or a cartoonist, perhaps “ensoulment” is the more precise word choice (Santos-Granero 2009b; Silvio 2019).

Figure 3.

The jars are in domestic use, filled with condiments, but because the storage platform is a clean, high place, the tall jar here becomes a temporary platform for offerings to the Mountain God and the Seven Stars, 1977. Photograph by author.

But if jars and baskets are not gods or ancestral souls, are they subsequently transformed by their extended contact with gods or other soul stuff (yŏng) as Jones implied and as a deconsecrated buddha statue or a once-blessed plaster saint is owed respectful treatment (Kendall 2021)? My evidence is limited but suggestive. Robert Sayers, collecting tools and examples of onggi pottery for the American Museum of Natural History, was gifted with a jar once used to house a god (AMNH Anthropology 70.3/5083); since the donor’s family had become Christian, they had no further use for it and wanted him to have it (Figure 4). They had kept it apart and not returned it to its original utilitarian function. Sayers reports a sense of guilt at removing such an object and bringing it to New York (Sayers 1991). I see it another way; his benefactor seized an opportunity to remove an object of ambivalence and possible danger. I remember another jar, one sighted in a mansin’s vision during an initiation kut. Yes, the initiate’s mother confirmed, there had been such a jar in her marital home, one they filled with rice as a site of veneration but, in her time, the practice had lapsed and the container became a water jar, even a piss pot. The mansin expressed horror and told the poor woman that this was why she was having such a miserable life (Lee and Kendall 1991).

Figure 4.

The jar that was once associated with a god. AMNH Anthropology 70.3/5083.

2.3. Garments and Other Vehicles

Clark describes a Christian faith healing for a recent convert, “on the day the woman took sick, some new cloth had been brought into the house, and the devil being angered at thus being ignored punished his former slaves” (Clark [1932] 1961). I read this as a familiar story, bright cloth or clothing attracting the jealous attention of an ancestor or family ghost. I had heard of jealous dead first wives following festive clothing into the house, riding it to intrude and make trouble. A variety of noxious forces would similarly adhere to a delivery of wooden furniture or shiny goods if the transfer had not been timed for an auspicious day. Wealth brought into the house—a new cow, a new car, electronics as attractive “shiny” things—might arouse the anger of the House Site Official who wanted a cup of wine as his cut of the expenditure. In the logic of noxious influences and greedy gods, I once witnessed the spiritual fumigation of a family’s new television set. (Kendall 1984, 1985, pp. 90, 97–99). Garments and television sets are not animated objects in the sense that some jars and baskets become animated. They are less containers to be inhabited than attractants that draw in an unwelcome presence.

The whisk is yet another kind of thing if I take Jones to mean a chori, a rice strainer. These would be suspended over the door at the new year with a small coin in the scoop as a talismanic wish for prosperity (MCBCPP 1969–1978, “Kyŏnggido,” 92). I encountered them as artifacts of playful folklore, made and distributed by the agricultural cooperative to raise funds while housewives used more efficient plastic.

2.4. Shamanic Materiality Especially […] in the Case of Portraits Sacred to Demons

The placings for the household gods were ordinary, everyday objects before being dedicated to this work. They appeared in the muted earth tones of rural life—brown jars, tan basketry, white paper. The shaman’s shrine, by contrast, is a place of bright, primary color and specialized form, things made for a particular ritual function (Figure 5). Before the advent of industrial textiles and commercial chemical dyes, Korea was an earth-toned place where most people dressed in off-white. Muted colors remain a sign of taste and decorum among the more conservative sectors of the population. Primary colors, the colors of five-element cosmology, set persons and time apart—court dress, robes worn by brides and grooms, rainbow-sleeved garments for children on holidays, and the billowing pure white robes and peaked caps of Buddhist liturgical dances. This is also the clothing worn in the god pictures that hang above the altar, mirrored in the costumes worn by mansin when they manifest gods during kut, singing their praises, speaking in their voices, miming, and bantering in their personas. Color makes atmosphere, an attribute of transformation and power “at odds with the normal” (Taussig 2009, p. 8)

Figure 5.

A Mansin manifesting a Mountain God in a shrine displaying offerings for a kut. God pictures are on the rear wall; the Buddha image would not have been seen on early 20th-century mansin altars, piles of candles (left) are from clients. Photograph by Homer Williams.

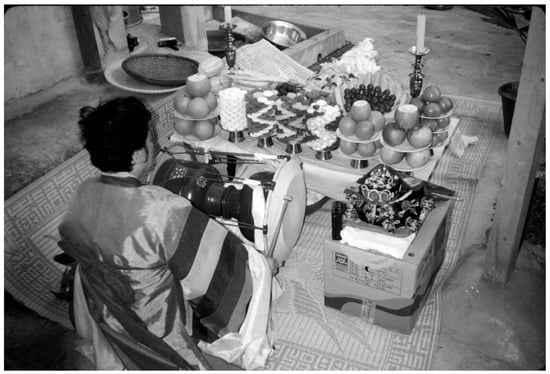

The costumes, and especially the painted images are the most consequential things in the shrine, but the shrine is abundantly thingish and different kinds of objects are transformed by association. Offerings of rice grain, fruit, meat, and alcohol are the basic stuff of rituals large and small. Attractively piled fruit and sweets enhance the surround of a kut as they do 60th, 70th, and first birthday celebrations (Figure 6). Some of the offering food brought in by clients goes back home with them, charged with auspiciousness, and some used to be shared around the community, a piece of rice cake torn off and cast away to mollify any wandering ghost who might have followed the offering home. But in contemporary kut, held discreetly in commercial shrines and nearly always far removed from everyday life, ostentatious piles of fruit and meat are sometimes left to rot, provoking critical media commentary.

Figure 6.

A Mansin performs a kut for the dead in front of an offering tray. Bananas and tomatoes have been added to a traditional display of apples, pears, and carefully constructed towers of traditional sweets. In 2003, the crown to the right of the mansin is more elaborate than it would have been in the 1970s. Photograph by author.

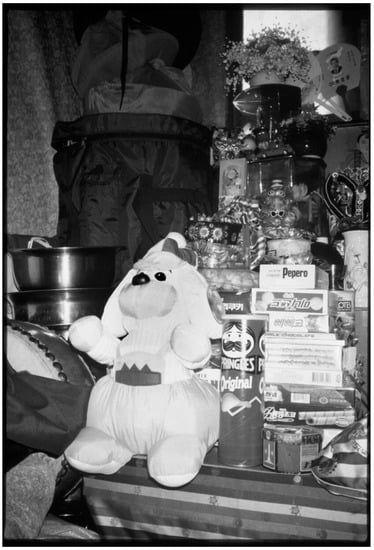

Contemporary abundance is also evident in the more permanent accouterments of the shrine. While jars and baskets dedicated to household gods have disappeared with country houses, the shrines reveal a flowering of shamanic materiality ever more abundant than in the past. Early 20th-century photographs reveal spare altars with basic ritual equipment, occasional candlesticks, a water bowl, cups, an incense pot, or bags of offering rice (e.g., General Commission on Archives and History, United Methodist Church, Mission Albums-Korea; https://web.flet.keio.ac.jp/~shnomura/mura/contents/album_6.htm accessed on 4 March 2012). Today, the shrine of a successful mansin contains multiples of incense pots, candlesticks, stacks of offering bowls, electric lamps in lotus shape, and other goods sold in shops catering to ritual needs (manmulsang). Mansin say that they are expected to return the largess that the gods have brought to them in the form of good business and by this logic, a well-fitted shrine testifies that a mansin enjoys the favor of powerful gods (Kendall 2009, pp. 129–78; for mansin; Yun 2019, pp. 81–101 with respect to Cheju simbang). Some gods have particular tastes; Child Gods receive bags of candy and other treats, Warrior Gods have appetites for meat and alcohol, some being particularly bibulous, and the pock-marked Princess Hogu craves make-up and jewelry to assuage her vanity. Altars sometimes acquire idiosyncratic touches, toys, dolls, or a fish aquarium to amuse the Child Gods while the shaman is out working, or little figurines in the form of childlike monks (Figure 7). Yongsu’s Mother, my primary mansin conversation partner, kept the books I wrote on a tray on her altar (Kendall 2009, pp. 154–76).

Figure 7.

Idiosyncratic offerings for the Child Gods and, on top, a flowery headpiece for Princess Hogu, the early 1990s. Photograph by author.

Particularly consequential are the mirrors, fans, knives, and other media with which the mansin directly engages the gods (Yang 2019). Some of these, along with the incense pots and bowls on the altar, costumes, prayer cushions, and other paraphernalia are inscribed with the names of clients who have particular relationships with particular gods in the mansin’s own pantheon and who have consequently been advised to make this gift, a link between their own household and the power of the shrine. All of this material recalls Pedersen’s (2007, p. 153) evocation of a “knotted virtuality” in the scraps of signifying cloth that connect a Mongolian shaman’s alter to things unseen, but the conduits of connection in the mansin’s shrine are finished products from a specialized commerce in ritual goods. Jongsung Yang suggests, however, that while “in the past, shamans knew where every item in their shrine came from, who made it, and when it was made, with each item having its own meaningful story and a connection to human energy,” these ties are muted when commercial objects are factory-made and purchased in abundance for ostentatious display (Yang 2019, p. 219).

The god pictures (musindo, taenghwa) that hang above the altar, Jones’ “portraits sacred to demons,” are the most significant and power-charged objects in the shrine, indeed in this entire discussion. The portraits function as seats for the gods who work with a particular mansin, gods whose presence she has seen in dreams or visions (Kendall and Yang 2015; Kendall et al. 2015; Kim 1989; Walraven 2009; Yoon 1994). The gods must be present in order for the mansin to practice, to see a vision, hear a voice, feel a bodily sensation, or simply intuit the gods’ intentions, which she must then put into “the true words of the spirits” (parŭn kongsu) conveyed to her client. This is not play-acting or should not be. In mansin logic, the stakes are high and if her words are wrong, she and her clients will suffer.

In the successful resolution of an initiation kut, the gods take up their seats in the shrine, but this outcome is by no means certain. The gods may choose not to enter the paintings, the gods may be present but not strongly present, and the gods may later depart from the shrine and leave the mansin to silence. To sustain the gods’ favor, a mansin daily venerates them in front of their portraits, asking for a clear flow of inspiration. When the paintings are old and tattered, the gods are petitioned to temporarily vacate their seats until clean, new images can be installed. Again, one encounters the anticipated mobility of things unseen in the movement of gods into and out of the paintings.

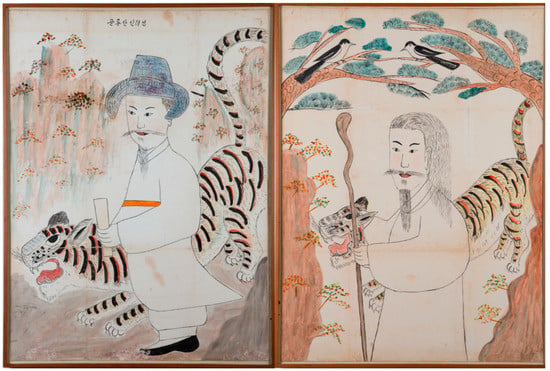

In contrast with the repurposing of domestic objects for sacred use, god pictures are produced for the mansin’s work and have been for many centuries (Yoon 1994). A god picture must be an accurate representation of the deity seen in the mansin’s vision, ideally rendered by a painter who labors to capture the mansin’s description in his own mind and who observes protocols of purity during his work (Figure 8). In the past, a mansin would acquire such paintings only when her gods had favored her with sufficient business to be able to afford them, the installation of the paintings certifying a fully realized mansin. Since the late 20th century, most paintings have been produced in commercial workshops and only a few painters claim to follow traditional production protocols for prayer and purity when executing a commission. Mansin who patronize traditionalist painters describe this kind of work as an essential precondition for a painting that will house a soul, but even the purists will acknowledge that it is the mansin’s own inspiration, the degree to which she is favored by the god, that causes the god to descend into and work through the painting (Kendall et al. 2015). In the 1970s, a far less affluent time than the present, most of the mansin I encountered in rural Kyŏnggi Province hung cheap commercial prints. Today, it is the workshops that are being undersold and supplanted by itinerating painters from China’s Korean Autonomous Region where most of the material contained in the ritual supply shops is also produced (Kendall et al. 2015). Whatever their origin, many regard the objects and paintings from a mansin’s shrine as having souls attached to them, a cause of reticence when old god pictures came to be collected and displayed as art.

Figure 8.

Mountain God paintings are now conventionalized images but these two old images, probably by the same hand, reveal distinctive visions of different Gods on different mountains, early- to mid-20th-century. Museum of Shamanism, photograph by Jongsung Yang.

The mansin’s shrine is a visual cliché in the contemporary Korean imagination, a legible setting when it appears in Korean film and TV drama. And yet, as the foregoing discussion suggests, a visual continuity of color, costume, and painted image elides the many changes in South Korean life over the last century as reflected in the shrine. Relative affluence is indexed in the piles of offering food and material goods on the altar. Rationalized production has meant not only accessible, affordable things, it has generally redefined understandings of how a god picture is made. The shrine also witnesses a shift in the loci of engagement with the gods who are the substance of the mansin’s work. The ordinary jars and baskets once conscripted as spirit placings in country households have become the stuff of folkloric display. The country households whose floorplans once mapped the location of resident gods are also nearly gone. Ritual engagements with the gods, often performed by housewives themselves, have shifted from residential space to the specialist space of the shrine and the kuttang. I say this not as a nostalgic backward glance but to mark sifts in an adaptable ontology of gods who sometimes inhabit things. Can we call this ontology “animism”? Do we gain anything by doing so?

3. Conclusions

Gods, souls, and more generalized spirits make use of different kinds of material things and they do so in different ways. This is not, in Tylor’s sense, an animist worldview that invests inert matter with spirit, nor do spirits, in the strictest sense, become pots or baskets or even trees and mountains. Material objects are not, in Ingold’s sense, “alive,” although in five-element cosmology they might be considered energized to different degrees or in shaman practice, charged with spirit presence much as a mansin’s mortal body is charged with inspiration. A 21st-century perspectivism developed in another place applies best to a mansin’s capacity to sometimes see and feel the world through the eyes and appetites of a greedy god or a hungry ghost, but as an avatar of recognizably human-like forms (cf. Viveiros de Castro 2004). The mobility of gods, spirits, souls, energies, the mutability of their presence has been a salient motif in the foregoing discussion, activities compatible with, if not identical to Ingold’s sense of a world constantly being reborn and of new animism writing more generally. In the Korean examples, the mobility of spirit necessitates acts by human agents to invite and encourage their presence in otherwise inanimate things and in shaman bodies. I suggested above that “animation” is best understood in these contexts as an action verb, a generalization extended to most of the things that I have been describing. Human agency, combined with spirit intention, causes gods to be present in jars or baskets and paintings and may also cause them to depart. Even with respect to a landscape where spirit presence may be ontologically anterior to human acts, the supplicant encounters the divine in a state of carefully prepared purification. Conversely, human activities can trouble the landscape, the household, or the shrine, disrupting and disbursing both gods and energies. Mobility and the role of human agency have made this an adaptable ontology, such that practices once associated with farming households are sustained in the mansin’s shrine and the commercial kuttang. Likewise, gods and mansin have incorporated a variety of new goods, most significantly god images as the products of rationalized production. This is not a primordial, nor even an “indigenous” Korean worldview melting into air, but rather, an ontology that continues to take shape within an emergent South Korean present. If “animism” has any use at all in a discussion of shamanic materiality in Korea, it is in causing us to take a closer look at things on the ground, to see them as mobile, and to not shy away from the contrasts between a “now” and a not so distant “then.”

Funding

My fieldwork in Korea between 1976 and 1977 was supported by the U.S. Fulbright Commission, the Social Science Research Council, and the National Science Foundation. Initial research on shaman paintings was supported by the Northeast Asia Area Council, Association for Asian Studies. Many research trips to Korea since 1983 have been supported by the Jane Belo Tanenbaum Fund, American Museum of Natural History.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of he Declaration of Helsinki. Recent research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the American Museum of Natural History 9 October 2008; AMNH did not have an IRB before that time. I submitted a statement of ethical intention to the Office of Grants and Fellowships, Columbia University for research done in the 1970s. All of my research has been conducted according to the ethical standards of the American Anthropological Association in order to ensure the safety and confidentiality of my subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data’ for this article is from my fieldnotes which, under the terms of my IRB approval and the assurances I have given my subjects, are held in confidence.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Akiba, Takashi. 1957. A Study on Korean Folkways. Asian Folklore Studies 14: 1–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Atkinson, Jane Monig. 1992. Shamanisms Today. Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 307–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupo, Ana Mariella. 2016. Thunder Shaman: Making History with Mapuche Spirits in Chile and Patagonia. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blacker, Carmen. 1975. The Catalpa Bow. London: George Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Brac de la Perrière, Bénédicte. 1989. Les rituels de possession en Birmanie: Du culte d’État aux cérémonies privées. Paris: Research on civilizations editions. [Google Scholar]

- Childs-Johnson, Elizabeth. 1995. The Ghost Head Mask and Metamorphic Shang Imagery. Early China 20: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Charles Allen. 1961. The Religions of Old Korea. Reprint. Seoul: Society of Christian Literature. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 2014. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais, Robert R. 1996. Presence. In The Performance of Healing. Edited by Carol Laderman and Marina Roseman. New York: Routledge, pp. 143–64. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1970. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Translated by Willard R. Trask. New York: Pantheon Books. First published 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemoz, Alexandre. 1983. Les Algues Les Anciens, Les Dieux: La Vie et La Relgion D’un Village de Pêchers-Agriculteurs Coréens. Paris: Le Léopard d’Or. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Graham. 2006. Animism: Respecting the Living World. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henare, Amiria, Martin Holbraad, and Sari Wastell. 2007. Introduction: Thinking Through Things. In Thinking through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. Edited by Amira Henare, Martin Holbraad and Sari Wastell. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, Caroline. 1999. Shamans in the City. Anthropology Today 15: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 2006. Rethinking the Animate. Re-Animating Thought. Ethnos 71: 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelli, Roger L. 1986. The Origins of Korean Folklore Scholarship. Journal of American Folklore 99: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, George Heber. 1902. The Spirit Worship of the Koreans. Transactions of the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 2: 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Laurel. 1977. Receiving the Samsin Grandmother: Conception Rituals in Korea. Transactions of the Korea Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 52: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Laurel. 1984. Wives, Lesser Wives, and Ghosts: Supernatural Conflict in a Korean Village. Asian Folklore Studies 43: 214–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Laurel. 1985. Shamans, Housewives, and Other Restless Spirits: Women in Korean Ritual Life. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Laurel. 2009. Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF, South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Laurel. 2021. Mediums and Magical Things: Statues, Paintings, and Masks in Asian Places. Berkeley: University of California Press, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Laurel, and Jongsung Yang. 2015. What is an Animated Image? Korean Shaman Paintings as Objects of Ambiguity. Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 5: 153–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Laurel, Jongsung Yang, and Yul Soo Yoon. 2015. God Pictures in Korean Contexts: The Ownership and Meaning of Shaman Paintings. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Taegon. 1989. Han’Gugmusindo (Korean Shaman Paintings). Seoul: Yŏlhwadang. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Dong-Kyu. 2012. Reconfiguration of Korean shamanic ritual: Negotiating Practices among Shamans, Clients, and Multiple Ideologies. Journal of Korean Religions 3: 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, David. 2015. Visions in Stones: Spirit Matters and the Charm of Small Things in Korean Shamanic Rock Divination. Anthropology and Humanism 40: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Heonik, and Jun Hwan Park. 2018. American Power in Korean Shamanism. Journal of Korean Religions 9: 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Diana S., and Laurel Kendall. 1991. An Initiation Kut for a Korean Shaman. Los Angeles and Honolulu: Center for Visual Anthropology, University of California, and distributed by the University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Masuzawa, Tomoko. 2005. The Invention of World Religions Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- MCBCPP (Ministry of Culture, Bureau of Cultural Properties Preservation). 1969–1978. Han’guk Minsin Chonghap Chosa Pogosŏ (Report on the Cumulative Investigation of Korean Folk Belief). Cum. vols. Arranged by Province. Seoul: Ministry of Culture, Bureau of Cultural Properties Preservation. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Thomas. 2015. Shaman Theory and the Early Chinese Wu. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 83: 649–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, Cornelius. 1951. The Koreans and Their Culture. New York: Ronald. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jun Hwan. 2012. Money is the Filial Child. But, at the same time, it is also the Enemy!": Korean Shamanic Rituals for Luck and Fortune. Journal of Korean Religions 3: 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Morten Axel. 2007. Talismans of Thought: Shamanist Ontologies and Extended Cognition in Northern Mongolia. In Thinking through Things: Theorizing Artifacts Ethnographically. Edited by Amiria Henare, Martin Holbraad and Sari Wastell. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 141–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Morten Axel. 2011. Not Quite Shamans: Spirit Worlds and Political Lives in Northern Mongolia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pels, Peter. 1998. The Spirit of Matter: On Fetish, Rarity, Fact, and Fancy. In Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces. Edited by Patricia Spayer. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando, ed. 2009a. The Occult Life of Things: Native Amazonian Theories of Materiality and Personhood. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2009b. Introduction: Amerindian Constructional Views of the World. In The Occult Life of Things: Native Amazonian Theories of Materiality and Personhood. Edited by Fernando Santos-Granero. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfati, Liora. 2021. Contemporary Korean Shamanism: From Ritual to Digital. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Sayers, Robert. 1991. Museum Collecting in a Postmodern World: A Korean Example. Museum Anthropology 14: 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvio, Teri. 2019. Puppets, Gods, and Brands: Theorizing the Age of Animation from Taiwan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhu, Gopal. 2012. The Shaman and the Heresiarch: A New Interpretation of the Li Sao. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taussig, Michael. 2009. What Color is the Sacred? Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vitebsky, Piers. 1995. The Shaman: Voyages of the Soul, Trance, Ecstasy and Healing from Siberia to the Amazon. London: Macmillan Reference Books. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo B. 2004. Exchanging Perspectives: The Transformation of Objects into Subjects in Amerindian Ontologies. Common Knowledge 10: 463–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraven, Boudewijin. 2009. National pantheon, regional deities, personal spirits? Musindo, Sŏngsu, and the nature of Korean shamanism. Asian Ethnology 68: 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy. 2021. Introduction. Ars Orientalis 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Jongsung (Museum of Shamanism). 2019. Sacred Shaman Implements. Seoul: The Museum of Shamanism. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, Suk-Jay (Yim Sŏk-Jay). 1970. Han’guk Musok yŏn’gu sŏsŏl (Introduction to Korean “mu-ism”). Journal of Asian Women (Seoul) 9: 73–90, 161–71, 212–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Yul Soo. 1994. Hwehwasaro salp’yŏponŭn han’gugŭi musindo [Looking at Korean shaman paintings through the history of visual art]. In Kŭrimŭro Ponŭn Han’gugŭi Musindo [Korean Shaman Paintings Seen as Paintings]. Edited by Yul Soo Yun. Seoul: Igach’aek, pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Hong-Key. 2006. The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Kyoim. 2019. The Shaman’s Wages: Trading in Ritual on Cheju Island. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For recent accounts of contemporary shaman practice see (Kim 2012; Park 2012; Sarfati 2021; Yun 2019). |

| 2 | This discourse has a historical context in Korea (Janelli 1986; Kendall 2009, pp. 11–24). |

| 3 | The site is now contested by Buddhist competition on the mountain. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).