The Loss of Self-Dignity and Anger among Polish Young Adults: The Moderating Role of Religiosity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Anger, Age, and Self-Dignity

1.2. Religiosity, Anger, and Self-Dignity

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Questionnaire of Sense of Self-Dignity (QSSD-3)

2.5. Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire

2.6. Religious Meaning System Questionnaire (RMS)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlations

3.3. One-Way ANOVA

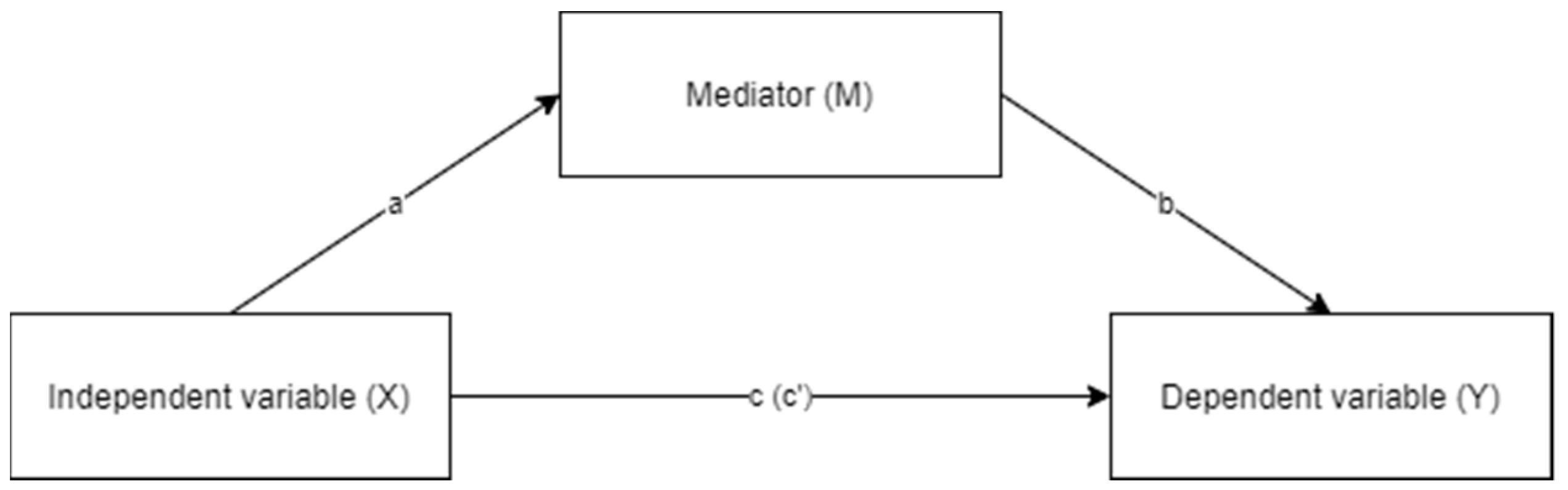

3.4. Mediation Analyses

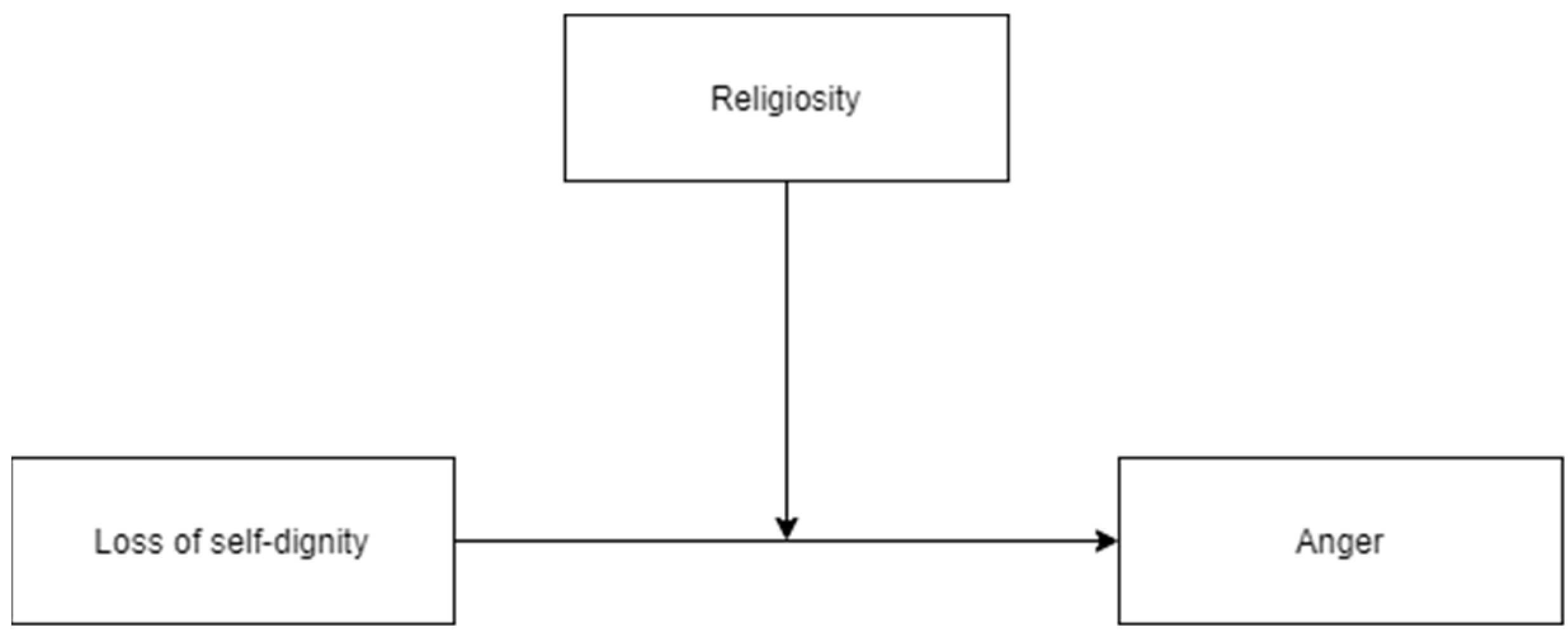

3.5. Moderation Analysis

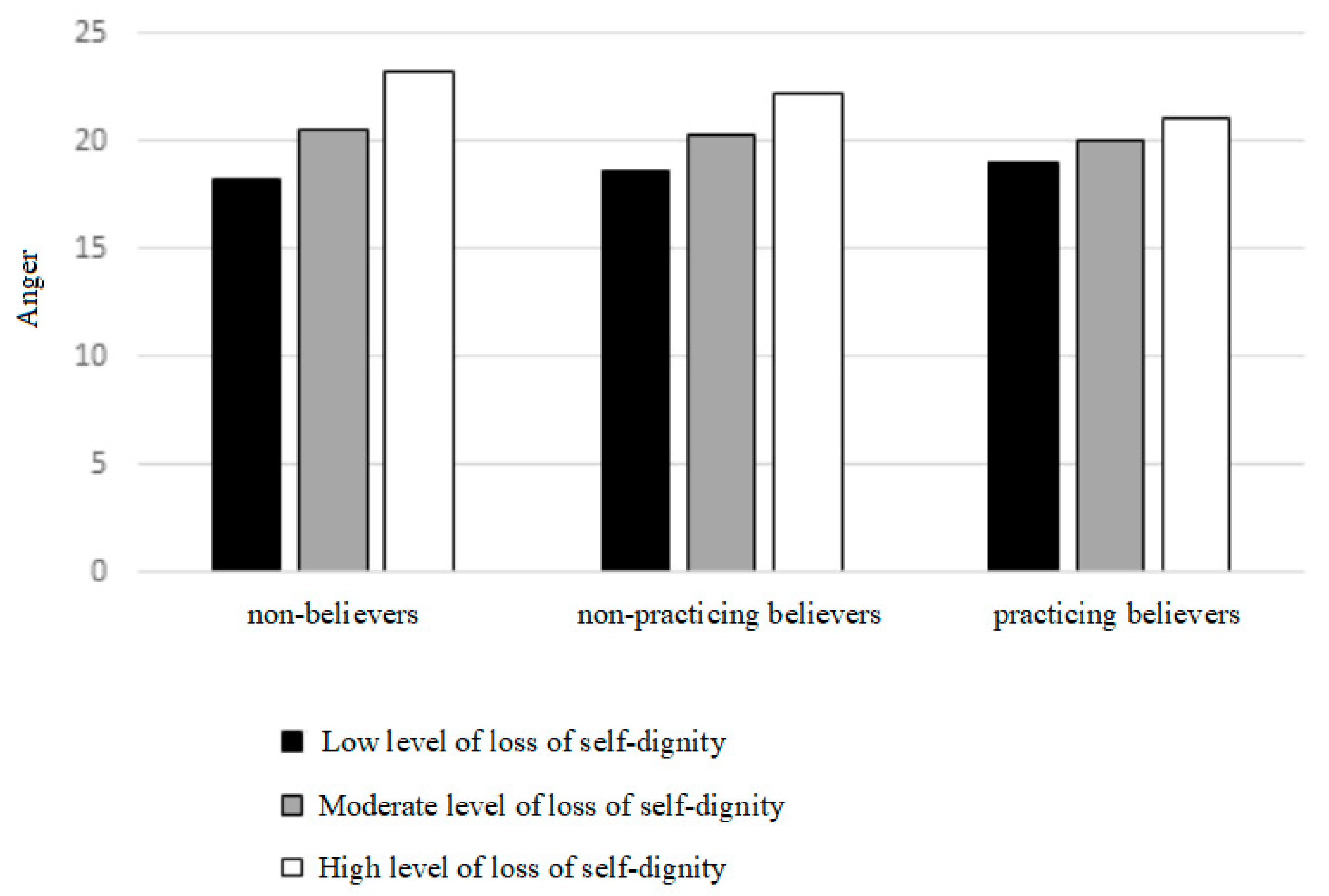

3.5.1. Loss of Self-Dignity, Anger, and Religiosity

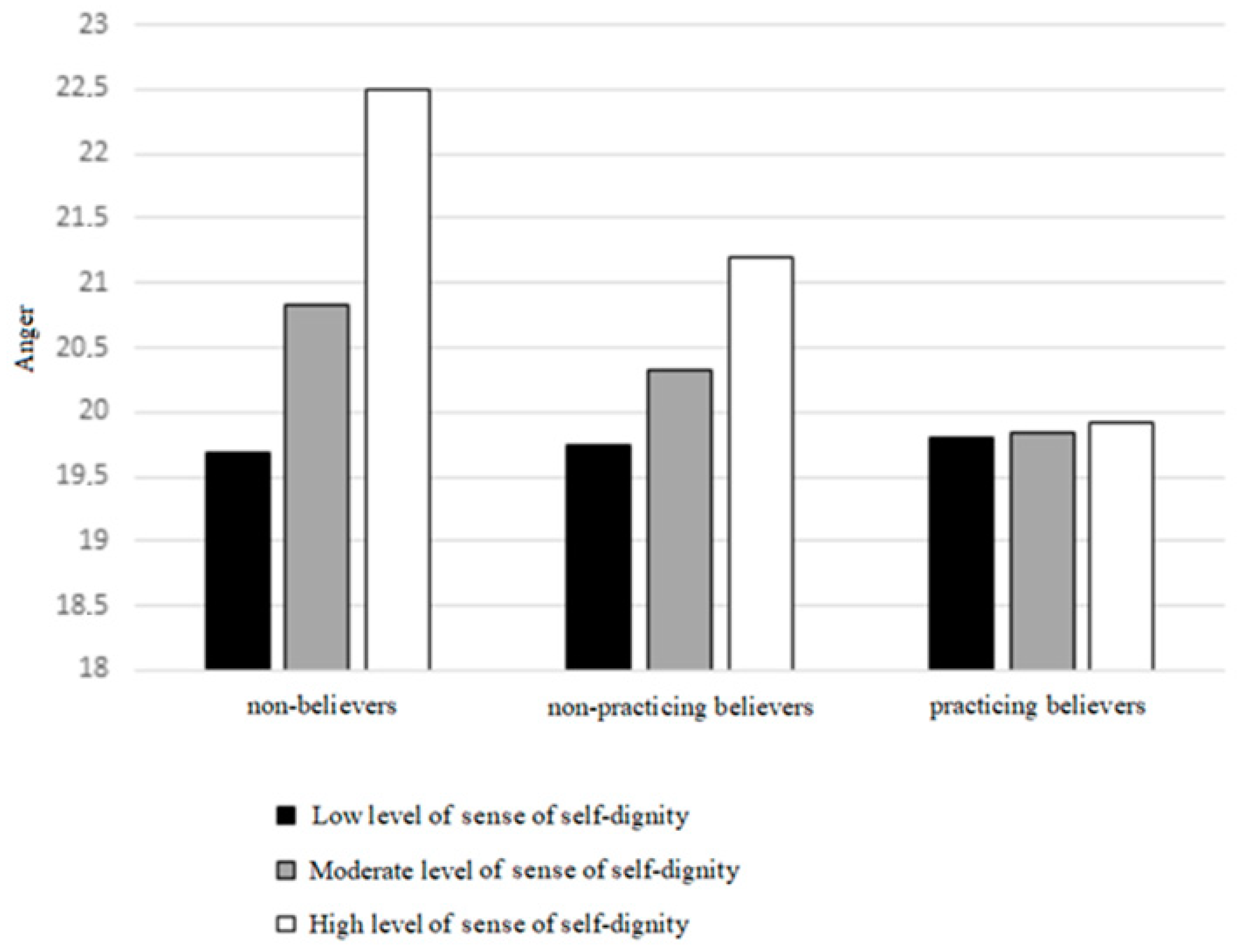

3.5.2. Sense of Self-Dignity, Anger, and Religiosity

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achour, Meguellati, Mohd Roslan Mohd Nor, and Mohd Yakub Zulkifli MohdYusoff. 2016. Islamic personal religiosity as a moderator of job strain and employee’s well-being: The case of Malaysian academic and administrative staff. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1300–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahles, Joshua J., Amy H. Mezulius, and Melissa R. Hudson. 2016. Religious coping as a moderator of the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 228–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, Gene G., and Erin B. Vasconcelles. 2005. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 61: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, Samantha F., Ken Kelley, and Scott E. Maxwell. 2017. Sample-size planning for more accurate statistical power: A method adjusting sample effect sizes for publication bias and uncertainty. Psychological Science 28: 1547–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill, James R. 1983. Studies on anger and aggression. Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist 38: 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, Christopher T., Della C. Loflin, and Hannah Doucette. 2015. Adolescent self-compassion: Associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Personality and Individual Differences 77: 118–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Laura Smart, and Joseph M. Boden. 1996. Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychological Review 103: 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter L. 1990. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, Leonard. 2012. A different view of anger: The cognitive-neoassociation conception of the relation of anger to aggression. Aggressive Behavior 38: 322–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, Leonard, and Eddie Harmon-Jones. 2004. Toward an understanding of the determinants of anger. Emotion 4: 107–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birditt, Kira S., and Karen L. Fingerman. 2003. Age and gender differences in adults’ descriptions of emotional reactions to interpersonal problems. The Journals of Gerontology B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58: 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, Bruce, and Jennifer Crocker. 1995. Religiousness, race, and psychological well-being: Exploring social psychological mediators. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21: 1031–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard-Fields, Fredda, and Abby H. Coats. 2008. The experience of anger and sadness in everyday problems impact age differences in emotion regulations. Developmental Psychology 44: 1547–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, Ryan H., Sander L. Koole, and Brad J. Bushman. 2011. “Pray for those who mistreat you”: Effects of prayer on anger and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37: 830–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Morton B., and Alan B. Forsythe. 1974. Robust tests for the equality of variances. Journal of the American Statistical Association 69: 364–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudek, Paweł, and Stanisława Steuden. 2017a. Predictors of sense of self-signity in late adulthood. A synthesis of own research. Psychoterapia 4: 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Brudek, Paweł, and Stanisława Steuden. 2017b. Questionnaire of Sense of Self-Dignity (QSSD-3): Construction and analysis of psychometric properties. Przegląd psychologiczny 60: 457–77. [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi, Barbara L., Carrie Winterowd, R. Steven Harrist, Nancy Thomson, Kristi Bratkovich, and Sheri Worth. 2010. Spirituality, Anger, and Stress in Early Adolescents. Journal of Religion and Health 49: 445–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, Laura L., Derek M. Isaacowitz, and Susan T. Charles. 1999. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist 54: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, Laura L., Monisha Pasupathi, Ulrich Mayr, and John R. Nesselroade. 2000. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79: 644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, Laura L., Helene H. Fung, and Susan T Charles. 2003. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion 27: 103–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Julia F., Steven Di Costa, Brianna Beck, and Patrick Haggard. 2019. I just lost it! Fear and anger reduce the sense of agency: A study using intentional binding. Experimental Brain Research 237: 1205–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clore, Gerald L., Andrew Ortony, Bruce Dienes, and Frank Fujity. 1993. Where does anger dwell? In Perspectives on Anger and Emotion. Edited by Robert S. Wyer and Thomas K. Srull. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Covington, Martin V. 1984. The self-worth theory of achievement motivation: Findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal 85: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragun, Deborah, Ryan T. Cragun, Brian Nathan, J. E. Sumerau, and Alexandra C. H. Nowakowski. 2016. Do religiosity and spiritual really matter for social, mental, and physical health?: A tale of two samples. Sociological Spectrum 36: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescioni, A. Will, and Roy F. Baumeister. 2013. The four needs for meaning, the value gap, and how (and Whether) society can fill the void. In The Experience of Meaning in Life: Classical Perspectives, Emerging Themes, and Controversies. Edited by Joshua A. Hicks and Clay Routledge. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, Jennifer, Shawna J. Lee, and Lora E. Park. 2004. The pursuit of self-esteem: Implications for good and evil. In The Social Psychology of Good and Evil. Edited by Arthur G. Miller. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 271–302. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Reed T. Deangelis, Terrence D. Hill, and Paul Froese. 2019. Sleep quality and the stress-buffering role of religious involvement: A mediated moderation analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., and Raymond F. Paloutzian. 2003. The psychology of religion. Annual Review of Psychology 54: 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., Shanmukh Kamble, and Nick Stauner. 2017. Anger toward God(s) among undergraduates in India. Religions 8: 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, Maurizio, and Jerrold F. Rosenbaum. 1999. Anger attacks in patients with depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60: 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, Beverley, Mark Baldwin, Lois Collins, Suzanne Patterson, and Riva Benditt. 1999. Anger in close relationships: An interpersonal script analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25: 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fein, Steven, and Steven J. Spencer. 1997. Prejudice as self-image maintenance: Affirming the self through derogating others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Agneta H., and Ira J. Roseman. 2007. Beat them or ban them: The characteristics and social functions of anger and contempt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J., Harry M. Gibson, and Mandy Robbins. 2001. God images and self-worth among adolescents in Scotland. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 4: 103–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Helene H., Minjie Lu, and Derek M. Isaacowitz. 2019. Aging and attention: Meaningfulness may be more important than valence. Psychology and Aging 34: 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbraith, Todd, and Bradley T. Conner. 2015. Religiosity as a moderator of the relation between sensation seeking and substance use for college-aged individuals. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 29: 168–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gausel, Nicolay, and David Bourguignon. 2020. Dropping out of school: Explaining how concerns for the family’s social-image and self-image predict anger. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gausel, Nicolay, and Colin Wayne Leach. 2011. Concern for self-image and social image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. European Journal of Social Psychology 41: 468–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Darren, and Paul Mallery. 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Grudziewska, Ewa, and Marta Mikołajczyk. 2020. The sense of self-dignity of people with mobility disabilities in Poland—a survey report. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 5: 290–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Eran, and James J. Gross. 2011. Intergroup anger in intractable conflict: Long-term sentiments predict anger responses during the Gaza war. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 14 4: 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, Eddie. 2003. Anger and the behavioral approach system. Personality and Individual Differences 35: 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F., Amanda K. Montoya, and Nicholas J. Rockwood. 2017. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal 25: 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Wei, Liu Ru-De, Ding Yi, Oei Tian Po, Fu Xinchen, Jiang Ronghaun, and Jiang Shuyang. 2020. Self-esteem moderates the effect of compromising thinking on forgiveness among Chinese early adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel-Cohen, Yael, Oren Kaplan, Smadar Noy, and Gabriela Kashy-Rosenbaum. 2016. Religiosity as a moderator of self-efficacy and social support in predicting traumatic stress among combat soldiers. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1160–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacelon, Cynthia S. 2003. The dignity of elders in an acute care hospital. Qualitative Health Research 13: 543–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Brenda R, and Cindy S. Bergeman. 2011. How does religiosity enhance well-being? The role of perceived control. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M., and Rasmus Jensen. 2015. Common method bias in public management studies. International Public Management Journal 18: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Campbell, Lauri A., Jennifer M. Knack, Amy M. Waldrip, and Shaun D. Campbell. 2007. Do Big Five personality traits associated with self-control influence the regulation of anger and aggression? Journal of Research in Personality 41: 403–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Kae Hwa, Gyeong-Ju An, and Ardith Z. Doorenbos. 2012. Attitudes of Korean adults towards human dignity: A Q methodology approach. Japan Journal of Nursing Science 9: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Palmer Oliver, and Jerzy Neyman. 1936. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs 1: 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Joshanloo, Mohsen, and Jochen E. Gebauer. 2019. Religiosity’s nomological network and temporal change. European Psychologist 25: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, Mohsen, and Dan Weijers. 2016. Religiosity moderates the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction across the globe. Social Indicators Research 128: 731–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, Dacher, Disa Sauter, Jessica Tracy, and Alan Cowen. 2019. Emotional expression: Advances in basic emotion theory. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 43: 133–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, Michael H., Bruce D. Grannemann, and Lynda C. Barclay. 1989. Stability and level of self-esteem as predictors of anger arousal and hostility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56: 1013–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, Sander, Michael E. McCullough, Julius Kuhl, and Peter HMP Roelofsma. 2010. Why religion’s burdens are light: From religiosity to implicit self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozielecki, Józef. 1977. O Godności Człowieka. Warszawa: Czytelnik. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Neal. 1995. Religiosity and self-esteem among older adults. The Journal of Gerontology 50: 236–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2014. The religious meaning system and subjective well-being: The mediational perspective of meaning in life. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 36: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, Ute, Cathleen Kappes, and Carsten Wrosch. 2014. Emotional aging: A discrete emotions perspective. Frontiers in psychology 5: 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppens, Peter, and Francis Tuerlinckx. 2007. Personality traits predicting anger in self-, ambiguous-, and other caused unpleasant situations. Personality and Individual Differences 42: 1105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, Peter, and Iven Van Mechelen. 2007. Interactional appraisal models for the anger appraisals of threatened self-esteem, other-blame, and frustration. Cognition and Emotion 21: 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, Peter, Iven Van Mechelen, Dirk J. M. Smits, Paul De Boeck, and Eva Ceulemans. 2007. Individual differences in patterns of appraisal and anger experience. Cognition and Emotion 21: 689–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, Robert D., Loren D. Marks, and Matthew D. Marrero. 2011. Religiosity, self-control, and antisocial behavior: Religiosity as a promotive and protective factor. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 32: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Nathaniel M., and David C. Dollahite. 2006. How religiosity helps couples prevent, resolve, and overcome marital conflict. Family Relations 55: 439–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, Avital, Yaira Raz-Hamama, Stephen Z. Levine, and Zahava Solomon. 2009. Posttraumatic growth in adolescence: The role of religiosity, distress, and forgiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 28: 862–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard L. 1993. Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine 55: 234–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, Mark M., Mitchell Berman, and Lea Eubanks. 2008. Religious Activities, Religious Orientation, and Aggressive Behavior. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 311–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Jennifer S., and Dacher Keltner. 2001. Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 146–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddi, Salvatore R., Marnie Brow, Deborah M. Khoshaba, and Mark Vaitkus. 2006. Relationship of hardiness and religiousness to depression and anger. Consulting Psychology Journal Practice and Research 58: 148–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, Eugenia, and Marcin Moroń. 2019. Contingencies of self-worth and global self-esteem among college women: The role of masculine and feminine traits endorsement. Social Psychological Bulletin 14: e33507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-González, María, Javier Lopez, Rosa Romero-Moreno, and Andres Losada. 2010. Anger, spiritual meaning and support from the religious community in dementia caregiving. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 176–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, Robert, and Rudi Dallos. 2004. Roman Catholic couples: Wrath and religion. Family Process 40: 343–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascaro, Nathan, and David H. Rosen. 2006. The role of existential meaning as a buffer against stress. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 46: 168–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, Ray, Curtis Read, and Alisha LeCheminant. 2009. The influence of religiosity on positive and negative outcomes associated with stress among college students. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 12: 501–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienaltowski, Andrew, Paul M. Corballis, Fredda Blanchard-Fields, Nathan A. Parks, and Matthew R. Hilimire. 2011. Anger management: Age differences in emotional modulation of visual processing. Psychology and Aging 26: 224–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mill, Aire, Liisi Kööts-Ausmees, Jüri Allik, and Anu Realo. 2018. The role of co-occurring emotions and personality traits in anger expression. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, Nazrat M., Eleanor Race Mackey, Bridget Armstrong, Ana Jaramillo, and Matilde M. Palmer. 2011. Correlates of self-worth and body size dissatisfaction among obese Latino youth. Body Image 8: 173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Novaco, Raymond W., and Claude M. Chemtob. 2002. Anger and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 15: 123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, Mayumi, Julia Picazo, Mark Olfson, Deborah S. Hasin, Shang-Min Liu, Silvia Bernardi, and Carlos Blanco. 2016. Prevalence and correlates of anger in the community: Results from a national survey. CNS Spectrums 20: 130–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortony, Andrew, and Terence J. Turner. 1990. What’s basic about basic emotions? Psychological Review 3: 315–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Lora E., Jennifer Crocker, and Amy K. Kiefer. 2007. Contingencies of self-worth, academic failure, and goal pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33: 1503–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, Michael W., L. Lee Roff, David L. Klemmack, Harold G. Koenig, P. Baker, and R. M. Allman. 2003. Religiosity and mental health in southern, community-dwelling older adults. Aging and Mental Health 7: 390–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawliczek, Christina M., Birgit Derntl, Thilo Kellermann, Ruben C. Gur, Frank Schneider, and Ute Habel. 2013. Anger under control: Neural correlates of frustration as a function of trait aggression. PLoS ONE 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelham, Brett W., and William B. Swann. 1989. From self-conceptions to self-worth: On the sources and structure of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 672–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, Marisol, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Thomas E. Joiner. 2005. Discrepancies between self- and other-esteem as correlates of aggression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 24: 607–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Piotrowski, Jarosław P., Magdalena Żemojtel-Piotrowska, and Amanda Clinton. 2020. Spiritual transcendence as a buffer against death anxiety. Current Psychology 39: 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, John E., Jon D. Kassel, and Ian H. Gotlib. 1995. Level and stability of self-esteem as predictors of depressive symptoms. Personality Individual Differences 19: 217–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, Inma, and Antoni Meseguer-Artola. 2020. Editorial: How to prevent, detect and control common method variance in electronic commerce research. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 15: I–V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, Scott. 2003. Socioeconomic status and the frequency of anger across the life course. Sociological Perspectives 46: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Antje, Michael M. Gielnik, and Sebastian Seibel. 2018. When and how does anger during goal pursuit relate to goal achievement? The roles of persistence and action planning. Motivation and Emotion 43: 205–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren, and Mark D. Reed. 1992. The effects of religion and social support on self-esteem and depression among the suddenly bereaved. Social Indicators Research 26: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, Constantin, and Jochen E. Gebauer. 2020. Do religious people self-enhance? Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, Sarah, Jason Jones, and Brian Thomas-Peter. 2010. Are you looking at me, or am I? Anger, aggression, shame and self-worth in violent individuals. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 29: 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenke, Melissa, Mark J. Landau, and Jeff Greenberg. 2013. Sacred armor: religion’s role as buffer against the anxieties of life and the fear of death. In Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Joonmo, and John Wilson. 2011. Generativity and volunteering. Sociological Forum. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanone, Michael A., Derek Lackaff, and Devan Rosen. 2011. Contingencies of self-worth and social-networking-site behavior. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14: 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroope, Samuel, Blake Victor Kent, Ying Zhang, Namratha Kandula, Alka Kanaya, and Alexandra Schields. 2020. Self-rated religiosity/spirituality and four health outcomes among US South Asian findings from the study on stress, spirituality, and health. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 165–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, Małgorzata, and Celina Timoszyk-Tomczak. 2020. Religious Struggle and Life Satisfaction Among Adult Christians: Self-esteem as a Mediator. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2833–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, Jessica L., and Richard W. Robins. 2004. Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry 15: 103–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. Jay, David Russel, Regan Glover, and Pamela Hutto. 2007. The social antecedents of anger proneness in young adulthood. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48: 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villani, Daniela, Angela Sorgente, Paola Iannello, and Alessandro Antonietti. 2019. The role of spirituality and religiosity in subjective well-being of individuals with different religious status. Frontiers in Psychology 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishkin, Allon. 2020. Variation and consistency in the links between religion and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishkin, Allon, Yochanan E. Bigman, Roni Porat, Nevin Solak, Eran Halperin, and Maya Tamir. 2016. God rest our hearts: Religiosity and cognitive reappraisal. Emotion 16: 252–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishkin, Allon, Shalom H. Schwartz, Ben-Nun Bloom Pazit, Nevin Solak, and Maya Tamir. 2020. Religiosity and desired emotions: Belief maintenance or prosocial facilitation? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 46: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorster, Nico. 2012. A theological perspective on human dignity, equality and freedom. Verbum et Ecclesia 33: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschull, Stefanie B., and Michael H. Kernis. 1996. Level and stability of self-esteem as predictors of children intrinsic motivation and reason for anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22: 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Bernard Lewis. 1951. On the comparison of several mean values: An alternative approach. Biometrika 38: 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Riccardo. 2017. Anger as a basic emotion and its role in personality building and pathological growth: The neuroscientific, developmental and clinical perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wink, Paul, and Julia Scott. 2005. Does religiousness buffer against the fear of death and dying in late adulthood? Findings from a longitudinal study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 60: 207–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterowd, Carrie, Steve Harrist, Nancy Thomason, Sherri Worth, and Barbara Carlozzi. 2005. The relationship of spiritual beliefs and involvement with the experience of anger and stress in college students. Journal of College Student Development 46: 515–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Steven, Andrew Day, and Kevin Howells. 2009. Mindfulnness and the treatment of anger problems. Aggression and Violent Behavior 14: 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Robert K., and Donald J. Veldman. 1965. Introductory Statistics for the Behavioral. New York: Sciences, Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Zajenkowski, Marcin, and Gilles E. Gignac. 2018. Why do angry people overestimate their intelligence? Neuroticism as a suppressor of the association between Trait-Anger and subjectively assessed intelligence. Intelligence 70: 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Ruida, Xu Zhenhua, Tang Honghong, Liu Jiting, Wang Huanqing, An Ying, Mai Xiaoqin, and Liu Chao. 2018. The effect of shame on anger at others: Awereness of the emotion-causing events matters. Cognition and Emotion 33: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, Zachary, Rojo Florencia, Ofstedal Mary Beth, Chiu Chi-Tsun, Saito Yasuhiko, and Jagger Carol. 2018. Religiosity and health: A global comparative study. SSM- Population Health 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Believers | Non-Practicing Believers | Practicing Believers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 154) | (n = 154) | (n = 154) | |

| Age | 18–35 | 18–35 | 18–35 |

| (M = 21.09; SD = 3.39) | (M = 21.49; SD = 3.66) | (M = 21.21; SD = 3.61) | |

| Sex | 100 women (64.9%) | 103 women (66.9%) | 123 women (79.9%) |

| 54 men (35.1%) | 51 men (33.1%) | 31 men (20.1%) | |

| Education level | 0 primary (0%) | 1 primary (0.6%) | 1 primary (0.6%) |

| 13 lower secondary (8.4%) | 14 lower secondary (9.1%) | 14 lower secondary (9.1%) | |

| 4 vocational (2.6%) | 4 vocational (2.6%) | 2 vocational (1.3%) | |

| 110 secondary (71.4%) | 104 secondary (67.5%) | 108 secondary (70.1%) | |

| 27 higher (17.5%) | 31 higher (20.1%) | 29 higher (18.8%) |

| Group/Variable | M | SD | Sk | Kurt | K-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research sample (n = 462) | |||||

| Loss of self-dignity | 18.60 | 5.85 | 1 | 2.66 | 0.098 *** |

| Sense of self-dignity | 106.07 | 20.74 | 0.37 | −0.03 | 0.078 *** |

| Anger | 20.41 | 5.73 | 0.07 | −0.51 | 0.047 * |

| Religious orientation | 28.23 | 15.09 | 0.65 | −0.42 | 0.113 *** |

| Religious meaning | 36.97 | 16.14 | 0.20 | −0.97 | 0.072 *** |

| Non-believers (n = 154) | |||||

| Loss of self-dignity | 19.12 | 5.94 | 0.81 | 1.89 | 0.071 |

| Sense of self-dignity | 103.80 | 20.83 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.059 |

| Anger | 20.87 | 6.24 | 0.04 | −0.54 | 0.046 |

| Religious orientation | 16.80 | 8.44 | 1.60 | 2.05 | 0.210 *** |

| Religious meaning | 22.01 | 8.66 | 0.65 | −0.30 | 0.098 ** |

| Non-practicing believers (n = 154) | |||||

| Loss of self-dignity | 18.69 | 5.88 | 1.26 | 3.81 | 0.115 *** |

| Sense of self-dignity | 104.45 | 18.63 | 0.59 | 0.16 | 0.076 * |

| Anger | 20.47 | 5.42 | −0.18 | −0.42 | 0.065 |

| Religious orientation | 24.97 | 10.32 | 0.94 | 1.75 | 0.073 * |

| Religious meaning | 35.51 | 10.22 | 0.07 | −0.49 | 0.058 |

| Practicing believers (n = 154) | |||||

| Loss of self-dignity | 17.97 | 5.69 | 0.99 | 2.64 | 0.117 *** |

| Sense of self-dignity | 109.97 | 22.18 | 0.23 | −0.54 | 0.108 *** |

| Anger | 19.88 | 5.48 | 0.28 | −0.58 | 0.083 * |

| Religious orientation | 42.92 | 12.18 | 0.01 | −0.21 | 0.082 * |

| Religious meaning | 53.40 | 10.32 | −0.42 | −0.32 | 0.067 |

| SD | COG | LOS | REL | EXP | P-A | V-A | ANG | HOS | RO | RM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | 1 | 0.83 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.82 ** | 0.79 ** | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.16 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.15 ** | |

| COG | - | 1 | −0.05 | 0.71 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.09 | 0.14 ** | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.14 ** | 0.15 ** | |

| LOS | - | - | 1 | 0.03 | 0.39 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.04 | 0.30 ** | 0.31 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | |

| REL | - | - | - | 1 | 0.50 ** | −0.12 * | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.14 ** | 0.15 ** | |

| EXP | - | - | - | - | 1 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.18 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.11 * | 0.13 ** | |

| P-A | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.39 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.01 | −0.14 ** | |

| V-A | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.51 ** | 0.34 ** | −0.09 | −0.16 ** | |

| ANG | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.52 ** | −0.08 | −0.12 ** | |

| HOS | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | −0.09 | −0.12 ** | |

| RO | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.87 ** | |

| RM | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Variable | A | B | A-B | SE | p | W(df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO | N-B | N-PB | −8.18 * | 1.075 | <0.001 | 238.790(2, 299) *** |

| PB | −26.12 * | 1.194 | <0.001 | |||

| N-PB | N-B | 8.18 * | 1.075 | <0.001 | ||

| PB | −17.95 * | 1.287 | <0.001 | |||

| PB | N-B | 26.12 * | 1.194 | <0.001 | ||

| N-PB | 17.95 * | 1.287 | <0.001 | |||

| RM | NB | N-PB | −13.51 * | 1.079 | <0.001 | 417.401(2, 303) *** |

| PB | −31.40 * | 1.086 | <0.001 | |||

| N-PB | N-B | 13.506 * | 1.079 | <0.001 | ||

| PB | −17.890 * | 1.170 | <0.001 | |||

| PB | N-B | 31.396 * | 1.086 | <0.001 | ||

| N-PB | 17.890 * | 1.170 | <0.001 |

| Model | X | M | Y | a | b | c | c’ | Indirect | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RO | LOS | ANG | −0.01 | 0.29 *** | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.01 | [−0.01; 0.01] |

| 2 | RM | LOS | ANG | −0.01 | 0.29 *** | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.01 | [−0.01; 0.01] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodzeń, W.; Kulik, M.M.; Malinowska, A.; Kroplewski, Z.; Szcześniak, M. The Loss of Self-Dignity and Anger among Polish Young Adults: The Moderating Role of Religiosity. Religions 2021, 12, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040284

Rodzeń W, Kulik MM, Malinowska A, Kroplewski Z, Szcześniak M. The Loss of Self-Dignity and Anger among Polish Young Adults: The Moderating Role of Religiosity. Religions. 2021; 12(4):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040284

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodzeń, Wojciech, Małgorzata Maria Kulik, Agnieszka Malinowska, Zdzisław Kroplewski, and Małgorzata Szcześniak. 2021. "The Loss of Self-Dignity and Anger among Polish Young Adults: The Moderating Role of Religiosity" Religions 12, no. 4: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040284

APA StyleRodzeń, W., Kulik, M. M., Malinowska, A., Kroplewski, Z., & Szcześniak, M. (2021). The Loss of Self-Dignity and Anger among Polish Young Adults: The Moderating Role of Religiosity. Religions, 12(4), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040284