1. Introduction

This article explores new developments in the worship of Mazu, one of the most popular goddesses in China, due to growing (religious) (trans)national tourism. After contextualizing the cult historically, I will show the contemporary transformations it has experienced, highlighting the actors, media, and processes involved. We shall see that transnational tourism plays a central role in these transformations. To undertake this task, I rely primarily on textual sources to reconstruct how the cult was founded and rendered orthodoxic throughout the centuries. I will juxtapose this with reconstruction accounts of contemporary practices, as well as my own ethnographic work, which included participant observation of important events in the worship of Mazu at her ancestral temple, such as her birthday, the day of “her ascending to Heaven,” and Meizhou’s Mazu Cultural Tourist Festival.

1 This juxtaposition will throw the transformations into relief. A mix of sources—textual and ethnographic—are necessary to place current dynamics in their longue-durée context.

Religious transnational tourism has received some sustained scholarly.

2 Pilgrimages across long distances are an age-old practice that, as the hajj and the camino de Santiago de Compostela show, has been taking place well before the rise of nation-states with the Peace of Westphalia in the 17th century. In contrast, trans-national religious tourism, that is, religious tourism that involves the building of multiple, simultaneous, and constant relationships across national borders, is much newer and has received relatively little attention. The “East,” which in the Western imagination is commonly portrayed as more “spiritual” and “mystical,” is often the destination of these trips.

3 The combination of religion and tourism has become one of the most significant transformations in the Chinese religious landscape. Chinese scholar Ma Jinfu found that, in 1997, there were over 2233 sites of religious tourism in China, including 1630 Buddhist, 335 Daoist, 240 Islamic, and 18 Christian sites.

4 Among them, many famous temples and pilgrimage sites, such as Buddhist and Daoist mountains, are major tourist sites. Every year, thousands of pilgrims travel to these religious sites to fulfill their religious pursuits. In addition, increasing numbers of tourists have been attracted by these religious destinations for their beautiful natural surroundings and rich cultural and historical heritage.

The extant literature notes how the desire for authenticity and commodification, two themes that I will discuss in my article, shape and result from the interplay of religion and tourism.

5 My contribution to this scholarship is the use of the notion of transnationalism to explore how the cult of Mazu—more specifically, the way the devotion to the goddess at her ancestral temple in Meizhou—has changed as a result of pilgrimage and religious tourism from Taiwan and by Chinese people living in other countries abroad.

The modern transformation of Mazu worship is part and parcel of significant changes in the Chinese religious arena as a result of new policies of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regarding freedom of religion and the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage. These changes have been combined with the deepening impact of globalization on China’s economy and culture. One of the most visible examples of this combination is the dramatic growth of religious tourism, both within China and from the diaspora. Starting from the end of the 20th century, Chinese religious traditions, including Buddhism, Daoism, and other popular religions, have seen many of their ancient sacred spaces become increasingly commercialized and folklorized into tourist sites. According to Juan, around 130,000 religious sites in China have been turned into tourist attractions.

6 The case of Meizhou temple provides a good window into the development of religious tourism in China, allowing us to see the incentives and characteristics of this phenomenon and highlighting differences between traditional religious activities and modern innovation.

Today, the Meizhou ancestral temple is one of the most important tourist sites that blends long-standing popular religious beliefs and rituals with cultural pilgrimage and tourism. This is not surprising, given that Mazu is the most prominent Chinese goddess, and that her cult has been transmitted not only all over China, but also to over 20 different countries, following the steps of Chinese diaspora. In fact, while the devotion to Mazu is particularly strong in southeast Asia, Mazu has become a pan-Asian object of worship, transmitted to all throughout of the world. As Lee’s work demonstrates, the term transnationalism implies more than just simply crossing national borders sporadically. Here, I adopt the seminal definition of Linda Basch: “transnationalism is a process that involves the forging and maintenance of “multi-stranded social relations that link together [the migrant’s, tourist’s, or traveler’s] societies of origin and settlement”.

7 We shall see how the worship of Mazu creates shared social spaces and builds networks in which and through which the Chinese in diaspora experience close and strongly affective connections with mainland China.

Contemporary Chinese popular religious practices have received some scholarly attention. For example, Chau Adam Yuet, John Lagerwey, and David Johnson have studied the revival of Chinese popular religious practices such as temple festivals in rural China.

8 All of these scholars understand this revival to be a reflection of or to go hand-in-hand with contemporary economic and political developments, such as the influence of market economy and the state’s new religious policy in the 1990s that opened up more spaces for worship. However, they did not pay enough attention to the role of religious tourism in the revival of Chinese popular religions.

In his study on the Mazu culture derivative and products, Liao Xhien Chih explores the role of tourism in Mazu’s cult, showing how temples to the goddess in Taiwan have adapted some traditional styles of Mazu’s images to design new artifacts to attract more pilgrims and appeal, in particular, to younger generations.

9 Wang Qingsheng also discusses how the interaction of culture, local industry, and tourism led to the development of the Dajia Mazu International Tourism Culture Festival in Taiwan,

10 Wang details a series of policies applied by Taiwan governments to promote traditional culture and tourism. Moreover, he explores the special role that performances by art troupes have had in the development of the festival, which has established the Dajia temple as the inheritor of traditional culture. Huang Ying-Fa’s article “From Religious Pilgrimage to Tourism and Bodily Cultivation: Taiwan Dajia Mazu Pilgrimage” also focuses on Taiwan Dajia Mazu and its transformation from religious pilgrimage to cultural tourism.

11 works provide insightful perspectives on religious tourism in the Taiwan area. Recognizing the socio-political and cultural conditions in mainland China, I would like to complement them by offering a view from Mazu’s ancestral temple.

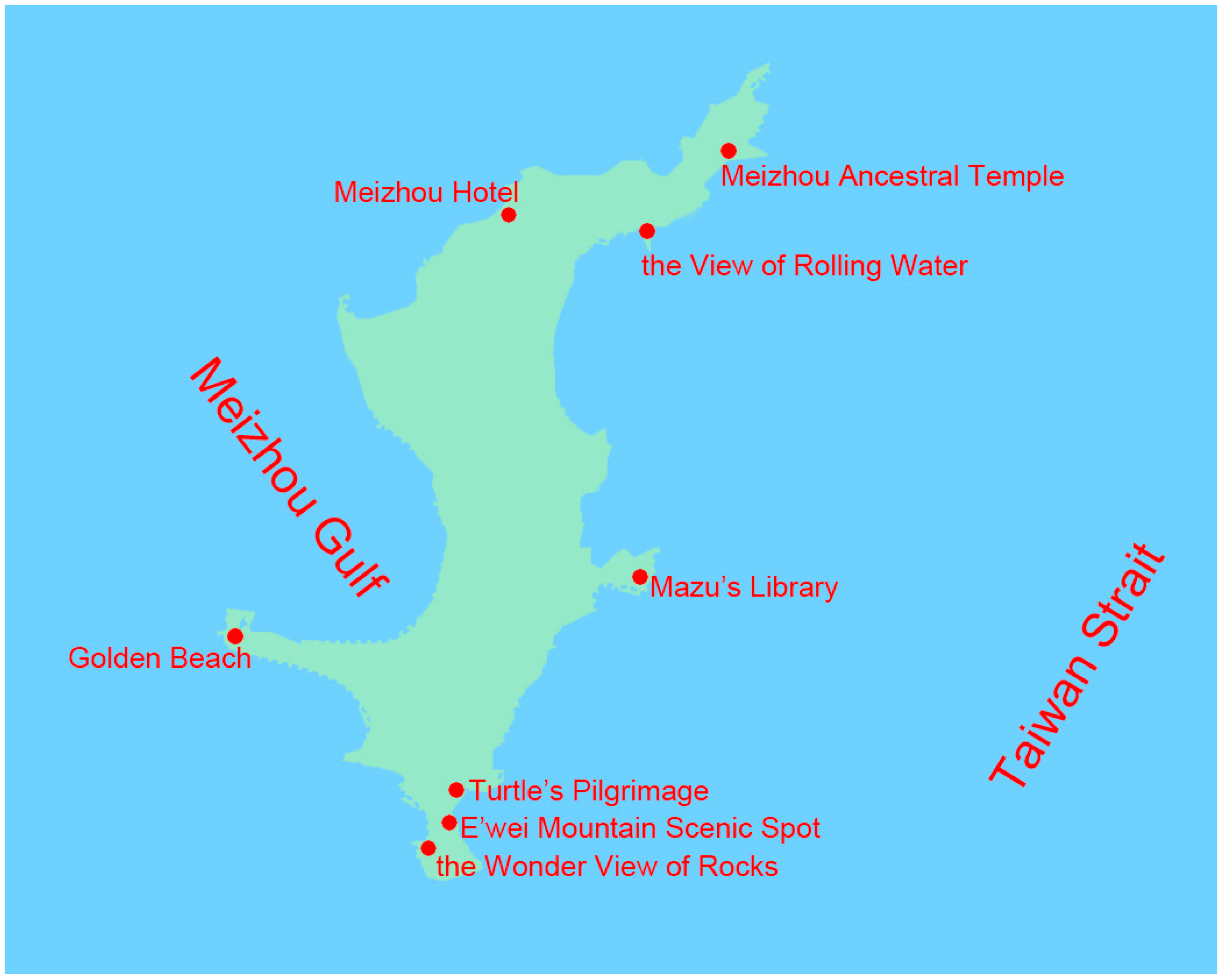

This article builds upon but goes beyond these works, by focusing on transformations linked to tourism in the ancestral temple of Mazu in Meizhou Island, the sanctioned point of origin of the traditions and cult around the goddess. The key questions I pursue are: how has the ancestral temple transformed itself from a place of ancient religious traditions publicly associated with provincial superstition into a famous pilgrimage and tourist site that represents Chinese cultural heritage and serves as a source of identity and belonging for the Chinese diaspora? How has Mazu’s image changed as a result of these transformations? To answer these questions, I examine three major transformations in the devotion to Mazu at the ancestral temple at Meizhou. First, architecturally, the ancestral temple has been refurbished into a national tourist resort, which provides a full array of recreational and leisure services to pilgrims and tourists, in addition to performing traditional rituals. Second, these rituals are no longer just a means to connect devotees with the goddess, but are now performed as a foundational part of China’s cultural heritage. Third, the Meizhou temple reemphasizes its religious hegemony as the original site of Mazu worship by combining traditional rituals such as “dividing incense” with new practices like “Mazu, returning to mother’s home from all over the world.” In the conclusion, I argue that the new developments of Meizhou temple illustrate the political and economic context within which contemporary popular religious traditions are reconstituting themselves in order to survive. These developments also reveal the interaction of popular religious traditions with state interests and economic dynamics, especially modern tourism.

2. The Transformation of a Local Religious Temple into a National Tourist Resort

This section will focus on the way that the Meizhou ancestral temple has evolved from a traditional temple complex to a tourist resort that attracts millions of tourists annually. We will see that the temple association, which was established in the Song dynasty to oversee the site, has played a key role in this evolution through the preservation of traditional architecture and religious–cultural artifacts of historical significance and through the building of new structures more in line with the demands of a growing tourist industry. I will have more to say about the structure and transformation of the temple association and the management of the temple in response to tourism later. For now, I would like to historically trace the architectural evolution of the temple from its origins to the present.

The earliest account of the Meizhou ancestral temple appears in

Shengdun zumiao chongjian shunji miaoji, compiled by Liao Pengfei in 1150, during the Song dynasty.

12 According to Liao,

It was said that she was the goddess was capable of communicating with Heaven. Her surname was Lin and she lived at Meizhou Island. At first, she lived as a female shaman and had the ability to forecast fortune and misfortune. After she died, people enshrined her at this island.

13

As we can see from this historical record, the first temple to worship Mazu was a small shrine established by local people. Historical sources show the expansion and development of this simple shrine into a full-fledged ancestral temple. A mythical story in “

The Record of the Founding Temple in Meizhou Island”

14 sheds light into how this process took place during the Song dynasty:

A merchant, Sanbao, was on his business trip to overseas. Due to bad weather, his ship had to anchor in the Harbor of Meizhou Island. When they were about to leave the next day, the anchor of the ship became stuck on a heavy stone, which could not be removed. After acknowledging that the goddess’s shrine was extremely efficacious, the merchant made a pilgrimage to the shrine, offered incense to the goddess, while praying to the goddess, “If we can return safely home through storms, I will donate a large amount of money to establish a temple for you to thank for your numinous assistance”. With the protection of the goddess, the merchant returned home safely. When the ship was passing through the island, the merchant made his pilgrimage to the goddess’s shrine again. To fulfill his vows, the merchant donated money to enlarge the shrine into a temple in Meizhou.

15The enlargement of the temple complex in Meizhou during the Yuan dynasty stemmed from Mazu’s divine protection of rice transportation. In the second year of the Tianli era (around 1329), the official who was responsible for rice transportation from the capital to Sansha city experienced a seven-day storm at sea. After crying out to the goddess for help, divine lights appeared, and the fleet was guided safely through the storm. Subsequently, the government official donated money to refurbish the ancestral temple

16. In this process of establishment of Mazu’s ancestral temple, we can see the on-going role of the state in sponsoring it and in the promotion of the Mazu cult, in recognition of her divine involvement to protect it and advance its interests. As I have discussed elsewhere, state patronage of the construction of Mazu temples was an important component of her canonization

17.

While all these initiatives consolidated the shrine at Meizhou as a visible and ritually efficacious site, it is only in the Ming and Qing dynasties that Mazu worship reached its heyday. By then, the temple had become a large complex, which included “the Palace of Celestial Empress” (

tianhou dian), a “Facing Heaven” garret (

chaotian ge), a drum and bell tower (

zhonggu lou), a dressing tower (

shuzhuang ge), the temple gate, and Taizi Palace (

taizi dian). Each building of the temple was glorified by a divine manifestation of the goddess as shown in the

Record of the Sagely Manifestation of the Celestial Consort (

Tianfei xiansheng lu).

18 “Pushing over Waves to Help Ships Cross a Storm,” (

Yonglang jizhou), describes the reconstruction project launched by the Commander Zhou to honor the goddess’s divine protection in assisting Ming military ships to fight pirates:

In the seventh year of the Hongwu reign (1374), the commander of Quan Prefecture, Zhou Zuo, [led] warships to patrol and arrest [pirates]. Suddenly, they encountered a strong hurricane springing up. The anchor was broken up and the ship ran aground. Sailors on the ship cried from all sides, knocked their heads, and cried for the goddess’s help. Shortly later, there was a divine light appearing in dark night which suspended in mid-air to illuminate everything together. The divine light also appeared upon the masthead of the ship.

19

The divine light was believed to be a sign of Mazu’s divine protection. Mazu was able to push over huge waves to send military ships to the harbor safely. This story ends with Commander Zhou’s devotional activities to sponsor the reconstruction of the Meizhou ancestral temple, including building the incense pavilion, drum and bell tower, and the temple gate.

20The following episode provides accounts of the establishment of the Facing Heaven Pavilion: “As Commander Zhang conducted warships to patrol the sea, he prayed for the goddess’s blessing. The goddess responded to his prayer, as expected. Commander Zhang then shipped building materials to the Meizhou Island and built a garret on the left side of the central hall, named ‘Facing Heaven Garret’”.

21 Once again, we see here that the expansion of the temple was due to the patronage of mobile groups, whether merchants or imperial officials. In this case, it is a military man charged with projecting the empire’s naval power. This is why we can affirm that the expansion of ancestral temple is part and parcel of the state’s deployment of Mazu as a metaphor for imperial power.

Similar narratives, in which devotees donate money to enlarge the temple, appear in different contexts. That is especially the case in “The Grand Governor Writing Prayer and Memorial” (zongdu zhudao shuwen) and “Building Dressing Tower in Gratitude” (zhuanglou xieguo). These two episodes contain several common elements. First, the goddess manifested herself to provide divine protection to devotees who prayed to her. Second, the devotees donated money or building materials to reestablish the temple in honor of the goddess’ numinous responses. While the Grand Governor Yao Qisheng (1623 to 1683) established the temple building named Taizi Palace, a local devotee sponsored the establishment of the dressing tower.

The above review of the history of Mazu’s ancestral temple at Meizhou illustrates the way that the temple evolved from a small shrine into a splendid complex. That each of the additions and enhancements to the original shrine was associated with a miracle performed by Mazu serves to legitimize and glorify the temple, while simultaneously crafting mythical narratives about the salvific power of the goddess. In other words, the growing size and elaborateness of the building go hand-in-hand with her rising status as an efficacious sacred figure. This tight connection between the glorious history of Mazu’s divine interventions on behalf of her economic and political influential devotees and the gradual-yet significant enlargement of the temple have contributed to making the Meizhou ancestral temple the preeminent sacred site for the worship of the goddess.

The history of the ancestral temple is, however, not a linear one of increasing prominence. During the Cultural Revolution in 1966, Mao launched an attack on all traditional ideas and things, including all religious institutions, activities, and objects. Among other measures, he ordered the closing of all religious institutions, the laicization or imprisonment of clergy, and prohibition of public and private religious activities. In the case of the Meizhou ancestral temple, most of its buildings established in the Qing dynasty were destroyed, as were the three statues of Mazu also constructed during this dynasty.

22Following the death of Mao in 1976, his perpetual revolution began to ebb. Taking advantage of the new context, the temple association, along with local devotees of Meizhou Island, initiated the project to renovate the ancestral temple complex in 1978.

23 Through this renovation project, the temple complex has preserved the traditional architecture style of the Qing dynasty. This process of remodeling the traditional architecture style can be seen as a case of the “invention of tradition,” which Hobsbawm and Ranger characterized as “a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past”

24. The “re-creation” of the traditional buildings establishes an unbroken link with Mazu’s place of birth, further legitimizing the temple as the undisputed inheritor of ancient religious tradition.

From 1998 to 2002, the temple association embarked on a major enlargement project to meet the demands of increasing numbers of pilgrims and tourists.

25 A new wing was constructed, consisting of new modern style structures, such as the square of the Celestial Empress, an opera stage, a temple gate, a drum and bell tower (

zhonggu lou), the Palace of Timely Salvation (

shunji dian), the Palace of the Celestial Empress (

tianhou dian), the Palace of Praying for Blessing (

qifu dian), an exhibition hall of Mazu culture, the Hotel of Praying for Blessing (

qifu binguan), a stone statue of Mazu, and the group sculpture of Mazu’s story.

As we can see from the list of new Mazu temple buildings, the temple association built several structures in line with the development of tourism. For example, the square of the Celestial Empress, which covers 10,000 square meters, sided with viewing stands to accommodate almost 10,000 tourists, is designed to perform large sacrificial ceremonies and other recreational activities. This massive space stands in contrast to the smallness and intimacy of the early shrine. The Palace of Praying for Blessing serves as a place where pilgrims, devotees, and tourists can invite Mazu statues to their homes and light lanterns of blessings. The exhibition hall of Mazu culture showcases her relics, antiques, paintings, and calligraphies. The Hotel of Praying for Blessing provides expanded accommodations for tourists. Before the new constructions of the hotel and other structures, the pilgrimage of devotees from throughout the world posed an enormous logistical problem for the Meizhou temple, as it could not accommodate all of them during the ritual services and performances. A saying circulated among the locals: tourists to Meizhou Island “visit the temple at daytime, while they sleep at night.” Indeed, one pilgrim from the Taiwan area I interviewed told me that he really enjoyed staying in the hotel at night, visiting the temple, and sightseeing the beautiful environment of the Meizhou Island during the daytime.

A 14.34-m-high stone statue of Mazu entitled “the Goddess of Peace” is one of most popular spots for tourists to take pictures and enjoy the scenic view (

Figure 1). It is part of a group of statues that render in modern form Mazu’s story and myths as recorded in

Pictorial Record of Sagely Manifestation from Holy Mother of Celestial Empress (

Tianhou shengmu shengji tuzhi).

26 We can conclude, thus, that tourism is shifting the emphasis in the devotees’ relation to Mazu from the textual representations that circulated widely in pre-modern China and were central to the literati’s construction of her myths to large-scale material representations such as buildings, plazas, and monuments that provide opportunities for tourists to have enjoyable and easily recordable experiences. In addition, the cult of Mazu is increasingly becoming a blend of traditional religious practices and non-religious aesthetic experiences. For instance, the temple association has built some scenic spots to emphasize the beauty of the island’s landscape, such as the pavilion of sea view, the pavilion of sunrising, the pavilion of listening to the roaring water. These scenic spots allow visitors to experience the sacredness of the place beyond the confines of the temple.

The incorporation of the natural environment through place-making practices of landscaping has been critical to transforming the temple into a national tourist resort (See

Figure 2).

27 According to temple history, the Meizhou ancestral temple was under the charge of religious specialists, starting with the monk Shi Zhaocheng (c. 1644) in the late Ming dynasty. The successive generations of temple chairs were inherited from masters to disciples. This genealogy of temple chairs has been abandoned in modern China. To adapt to the changing nature of pilgrimage and religious tourism, the Meizhou ancestral temple has evolved from a religious association managed solely by religious specialists to an entity that integrates religious, economic, and tourist services. Starting from 1986, the temple has been managed by a temple board, consisting of a chairman and board members.

28 The temple board oversees and manages departments created to improve the temple’s ritual and tourist services. There is now an administrative office for scenic attractions. Taifu company, the temple-owned enterprise, which is affiliated to Antai Hotel and Qifu Hotel, has been contracted to provide accommodations for tourists. In addition, an independent labor service company is responsible for producing the tourist merchandise, as well as managing stores, booth rentals for the temple attraction areas, and Mazu’s pastry shop. The art troupe, Celestial Empress, performs traditional music, dancing, and local opera to attract tourists, while a chanting troupe offers chanting services for Mazu devotees and an “offering production group” is charged with making sacrifice rituals to the goddess. Finally, a medical clinic dispenses medical care for tourists and pilgrims. In other words, tourism has led to the proliferation and formalization of temple functions, as well as to the commodification of religious practices and artifacts.

29 This commodification does not mean that religion is simply a reflection of economic forces. Rather, there is a relation of reciprocal determination between religion and economy. Mayfair Yang argues that the temple’s “ritual economy cannot be seen merely as the result of economic development, for ritual life has also fueled economic growth (it often provides the organizational apparatus, sites, and motivation for economic activity).

30The local government has played a major supporting role in the process of architectural, spatial, and managerial transformation of the ancestral temple. This is because the temple’s high economic and tourist potentials are considered effective vehicles for generating prosperity for the local economy and income for local government.

31 Since 1992, China’s central Communist government has designated Meizhou Island as a national tourist resort, further increasing the profile of the ancestral temple. To develop the tourism to Meizhou, the Putian government sponsored the temple association to refurbish the buildings and religious sites of the ancestral temple. As described in the local government document entitled “Construction Planning of Ancestral Temple”, the reconstruction project was envisioned to “highlight the traditional style and thereby making the temple complex as an ideal of ancient architecture. This temple should be a combination of religious pilgrimage, tourism, academic center, and vocation”.

32 In other words, key to the invention of tradition was making the ancestral temple a “foundational hierophany,” to draw from Mircea Eliade, an axis mundi connecting to primordial, mythical times.

33The invention of tradition, commodification, and architectural reconfiguration of the ancestral temple in Meizhou has made it a major tourist and pilgrimage destination that attracts millions of tourists, including Mazu devotees from oversea. According to the Putian government, the Meizhou temple accommodated around 1.56 million visitors from both mainland and overseas China in 2010.

34 These devotees bring the capital that they have earned through their hard work and success in diaspora, further encouraging more development and commodification. On the one hand, the promotion of Mazu temple by the local government in the Meizhou area has contributed to the transformation of the Mazu cult; on the other hand, this promotion has brought financial income to support local economic and social developments.

3. Reproducing Traditional Culture and Inheriting Legacy: Folklorization (minsu hua)

The construction of the translocal devotion to Mazu was part of a gradual process, in which politics, that is, the actions of and recognition by local and imperial governments, have played a major role, setting the stage for the contemporary, tourist-based promotion of the cult. Let us review this process. According to tradition and official historical records, Mazu worship was incorporated into the Register of Sacrifices (

sidian) starting from the Song dynasty.

35 In the Song era, the Register of Sacrifices referred to a list of ceremonies performed by the emperor and his officials, including rituals performed by local officials at local shrines. Preparing and participating in ritual performances was one of the main responsibilities of local officials. Since then, the Mazu cult was incorporated into the official pantheon under the administration of the Imperial Board of Rites, which standardized sacrifices dedicated to Mazu in accordance with the regulations of the Register of Sacrifices starting from the mid-11th century. As recorded in

Songhui yao, prefects and magistrates were obligated to perform official ceremonies at local Mazu temples recognized by the Song government twice each year, in the mid-months of spring and autumn. In addition, the emperor also dispatched officials to perform official sacrifices in the ancestral temple of Mazu at Meizhou as ordered by imperial edict. The performance of the official sacrifice ceremony ordered by imperial edict was considered as the greatest honor for local cults.

The Qing government established a more routinized and standardized approach to the official rituals dedicated to Mazu. She was incorporated into the official sacrifice system, as can be seen in the regulations presented in the Qing’s Register of Sacrifices from 1733. Since then, the highest-ranking bureaucrat in every part of the country—each province, prefecture, and county—had the duty of worshipping Mazu during the spring and the autumn. In addition to the spring and autumn sacrifices, Qing emperors also issued edicts to dispatch officials from the central government to deliver sacrifices at the ancestral temple of Mazu at Meizhou Island on behalf of the emperors. Qing official texts, such as “Collected Statutes of the Great Qing from the Kangxi Reign” (

Kangxi daqing huidian), stipulated the proper rules, procedures, and materials to be used in official rituals, including the arrangement of orchestras, the literary format of eulogies, ritual garments, honor guards, and the lists of officials who could witness the events.

36 The dates of the standard sacrifices and the offerings first had to be approved by the emperor. The dispatched official and the local officials obligated to perform the ceremony were representatives of the emperor, and thus they ritually enacted the emperor’s attitude of reverence for the deity. In addition, the official prayers written for the sacrifices devoted to the deities elaborately illustrate the emperor’s authority. Specifically, the prayers make it clear that the emperor sent officials to Mazu temples to announce the imperial title of the goddess granted by the court and to reward her contributions to the imperial government.

To give a sense of the ritual etiquette involved, the following is a sketch of the official rituals dedicated to Mazu. The preparations involved the participants purifying themselves for two days. Everything had to be put in order on the day of the ritual, including the three sacrificial animals that would be offered and the many sacrificial instruments used at the occasion. Members of the music office (jiaofang si) played the music. The cantors (zanyin guan) would lead the sacrificer (chengji guan) up to the left gate and into the dressing room. After purifying themselves, the officials assumed their assigned positions in the temple hall. The ceremony began with the ritualist “welcoming the deity” (yingshen). The sacrificer and his assistant presented incense to the deity in front of the altar three times, and performed a ritual sequence of bowing, prostrating, and rising. The ritualist then announced that he would “proceed with the first sacrifice.” Silk, libations, and prayers were offered on the altar by the officials. The master of prayer read the written prayers, placed them on the altar, prostrated thrice, and withdrew. The second and final offerings included two libations: the master of wine offered the wine vessel at both the left and right sides of the altar, and then returned to his place. The ceremony ended by “bidding farewell to the deity” (songshen). All the officials performed three prostrations and nine kowtows, and the prayers, silk, and food were sent away to be burned.

These descriptions of the intricate ritual etiquette at Mazu’s ancestral temple show that it was mostly a top-down affair that required extensive training. It is also clear that the temple had neither the facilities nor the activities to create a total immersive experience for pilgrims and tourists alike. The temple board had not only to transform the sacred space, as we saw above, but also had to enhance its attraction and reputation by renewing its traditions. With this aim in mind, the temple board sought to retain the “original,” official sacrifice ceremony, while staging it for a large audience. At the first tourist festival of Mazu culture in 1993, the performance of this reconstructed official sacrifice ceremony became the centerpiece. Since then, the official sacrifice to Mazu at Meizhou, along with the Yellow Emperor sacrifice at Shan’xi and the Confucius sacrifice at Qufu, have been designated as national sacrifices by the Ministry of Culture.

Despite its claim to be fully grounded in ancient traditions, the restored official sacrifice of Mazu integrates into the traditional ceremony some modern innovations to attract tourists, meet the needs of devotees, and express the current times. In terms of following ritual traditions as described in the official sacrifice of the Qing dynasty, the modern version incorporates the basic traditional ritual structure, including welcoming the goddess, offering incense, offering silk, three sacrifices, the performance of three prostrations and nine kowtows. To show the continuities and variations vis-à-vis the ritual etiquette in the Qing version, here is a sketch of the modern version dedicated to Mazu (I participated in the sacrifice ceremony dedicated to Mazu held at the 21st China Meizhou Mazu Cultural Tourist Festival on 1 November 2019. The description of this sacrifice ceremony is based on my fieldwork observation and the record of Mazu temple at Meizhou Island).

37“The banquet of sacrificial offerings,” a long dining table, is placed on the platform of the Central Hall. Mazu’s sedan and incense altar are situated in the central position of the dining table, symbolizing the goddess’s status and presence at the ceremony (

Figure 3). The area in front of the altar is the area to make offerings to Mazu and to read the eulogy honoring the goddess. The right sides of the altar are the place for purifying. The stage below the banquet contains the leading and assistant sacrificers. The dining table displays sacrificial artifacts and offerings. In line with the traditions, the sacrificial offerings adopt animal offerings of

shaolao (lesser lot), which includes a pig and a sheep.

38 The offering items for three sacrifices include wine vessels, fruits, and flowers.

First, the cantor announces to the fire the salute and beats the big drums as the ceremony opening. The cantor then proclaims that the guard of honor and guardian will assume their position. The leading and assistant sacrificers are led by the ritualists to assume their proper positions (

Figure 3). The performance group, including dancers, musicians, and singers, also assume their proper positions. After that, the songs to welcome the goddess are played. The leading sacrificers cleanse their hands, pick up the incenses, and present incense to Mazu in front of the altar and bow three times. The ritualist will collect the incense and put it in the incense burner. The cantor announces sacrificers will offer the sacrifice of silk. The leading sacrificer will read the eulogy in the traditional style. The ceremony proceeds with the first sacrifice accompanied by playing the music of “the Peace of Ocean.” The wine vessels are offered on the altar, followed by a second sacrifice accompanied by the music of “Peace.” Fruits are offered; the last sacrifice is performed with the music of “Universal Peace” and the silks are presented to the goddess. During the ceremony of three sacrifices, the dancers will perform the traditional dance,

Bayi, with plumed artifacts. The ceremony ends by burning the prayer scrolls and silks, and “bidding farewell to the goddess.” All the sacrificers perform three prostrations and nine kowtows.

The modern version of sacrifice ceremony bears strong family resemblances and shares a common temporal template with the traditional version. As historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot has argued, the selective management of time and memory, what is preserved and what is not, is one of the ways by which elites reproduce power.

39 These two versions of sacrifice ceremony are both organized around the sequence of preparing the ceremony, greeting the goddess, presenting the incenses, reading the prayer, performing three sacrifices, and sending off the goddess. In addition, there are other traditional elements reflected in the modern version, such as the sacrificial offerings, artifacts, musical instruments, and the outfits of cantors and ritualists. The application of traditional elements is to emphasize the glorious history of this sacrificial ceremony. In this sense, the modern version performed by the Meizhou temple is promoted as an expression of the ritual heritage of imperial China and further confirms its religious hegemony as the first Mazu temple in the world.

Nevertheless, to attract modern tourists, there are some innovations in the event. First, the sacrifice ceremony of Meizhou temple adds the performance of

yuewu (dance with music) during the section of three sacrifices. This traditional dance, which is accompanied by sacrificial music,

yuewu, represents an important innovation on the traditional sacrificial dance,

bayi, which is normally used in the sacrificial ceremony dedicated to Confucius and performed by a male dancer. To emphasize the Mazu’s identity as goddess,

yuewu are only performed by 20 year-old female dancers whose body postures are meant to express the female image of a compassionate sea goddess: “a beautiful young girl who saves people in the sea”.

40 (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The dance also uses plumed artifacts and combines some postures from local opera troupes to highlight Mazu’s femininity and her local background. The music that accompanies

Yuewu is composed by modern musicians Lin Hanzu and Zheng Ruilin, incorporating the music of “welcoming the goddess,” and the music of “Peace of Ocean,” “Peace,” and “Universal Peace”.

41 This sacrificial music inherits the style of traditional sacrificial music to emphasize the solemnity and holiness of the ceremony, while incorporating melodies from local music, adding a folkloric element to the performance. Second, the cantor and ritualists are trained female actors who are college students in a local university (

Figure 6). In the traditional sacrificial ceremony, the cantor and ritualists are male officers from the Ministry of Rites. According to the ritual history, women were not allowed to participate in official ritual ceremony. To create an entertaining and alluring atmosphere, the modern version includes female actors with beautiful dancing postures and a female cantor with a nice voice who functions as a host (

Figure 5).

Third, the leading sacrificers are usually the chair of the temple board from the ancestral and affiliated temples. In the sacrificial ceremony I observed, the leading sacrificers were the chair of the temple board of the ancestral temple at Meizhou Island, Lin Jinzan; the temple chair from the Celestial Empress Temple at Taiwan Beigang (beigang tianhou gong), Cai Yongde; the temple chair from the Celestial Empress Temple and the Selangor and Federal Territory Hainan Association in Malaysia, Deng Cairong. In other words, the religious specialists reflect the transnational character of the devotion, including ritualists from key nodes in the diaspora, nodes that are marked by prominent-yet-secondary temples. In the same way, the assistant sacrificers consist of members of the temple board and overseas pilgrims. The move to invite temple chairs and pilgrims from abroad is to reinforce the relationship between the ancestral temple and its affiliated temples beyond the mainland and to generate a unified sense of identity and belonging among all pilgrims who are main customers and donors for the temple attractions at Meizhou. It represents an effort to extend the networks of patronage that were established during the imperial period. As I described above, in the traditional sacrificial ceremony, the leading sacrificers were officers dispatched by the emperor, while the assistant sacrificers were local officers. In this traditional version, the dispatched official and the local officials charged with performing the ceremony were representatives of the emperor, and thus, they ritually enacted the emperor’s attitude of reverence for the deity. In contrast, in the modern ceremony, the reverence that is enacted and that has become central to the religious legitimacy and visibility of the cult is that of the pilgrims and tourists, who are increasingly coming not only from throughout China but also from the Chinese diaspora.

Fourth, the sacrificial ceremony is held on Mazu’s birthday, the day of “her ascending to Heaven”, and of Meizhou’s Mazu Cultural Tourist Festival, a coordination that seeks to increase its tourist appeal. In addition, the performance teams are divided into small-, medium-, and large-scale groups to meet the different ritual requirements. For example, the small-scale group is responsible for providing sacrificial ritual services for pilgrimage groups. This group also performs an abbreviated version of the sacrifice ceremony, which lasts just 12 min, every Sunday morning, making it possible for tourists with busy itineraries to attend, while also requiring them to stay overnight to be able to make it to the ceremony. In turn, the large-scale team performs the traditional sacrifice ritual at the ancestral temple’s Mazu square, which, as stated above, covers 10,000 square meters and is sided with viewing stands to accommodate almost 10,000 tourists.

In the process of restoring the sacrificial ceremony, the temple association appropriates old ritual traditions, adapting them and blending them with new practices and media to respond to the demands of tourists and to capture the financial benefits brought by tourism and government agencies. This is a process of “folklorization,” in which local religious and cultural traditions are reinterpreted as “part of the folklore,” expressions of the core cultural identity of a people. This identity can then be preserved, performed, consumed, and marketed nationally and globally as an authentic, intangible cultural heritage. As Zhou argues, cultural “heritagization” becomes a new means of seeking legitimacy for popular religious practices: “Before the rise of intangible cultural heritage, components of folk beliefs such as shrines and temples were protected due to their value as ‘antiquities.’ Now that these places have been declared by the government as ‘heritage conservation units,’ the folk beliefs associated with them have indirectly legitimized”.

42 What is underlying the processes of folklorization and cultural heritagization is a powerful desire for authenticity, a desire by the pilgrims and tourists alike to experience tradition as its most essential, as it was at its origins

43.

In the case of the Meizhou ancestral temple, the sacrificial ceremony at the temple has become the national model for recovering and transmitting traditional culture. Moreover, the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) identified the temple and its reconstituted ceremonies as part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage in 2009. As a result, the temple now benefits from special protection and national funding and can thus be repackaged as something that has universal legal standing and recognition. In effect, this is a new national and global “canonization” of Mazu.

Now, the goddess is not an imperial metaphor, but a trope for promoting religious traditions outside the realm of religion, for circulating traditions stripped of their local, grassroots signification and presented as living inheritors and protectors of Chinese culture and history. This resignification makes them worthy of preservation and national and internal support for politico-economic purposes, including the development of tourism.

4. Goddess of Transnationalism: Reunifying Oversea Chinese and Establishing a Common Cultural Identity

As the uncontested origin of the Mazu cult, the Meizhou ancestral temple draws from its historical prestige through a variety of strategies in order to present itself as a forge of a common cultural identity that reunifies oversea Chinese people with the motherland. A particular case in point is the traditional ritual of “dividing incense,” which is combined with an innovative ritual called “returning to mother’s home” (huinaingjia). The latter enables the temple to package itself as the “mother’s home for Mazu all over the world.” Furthermore, the temple also organizes other celebrations and events that consolidate its reputation as a major center for cultural, tourist, and commercial exchange across the Taiwan strait.

Mazu’s popularity is highest in southeastern coastal China and Taiwan, where her temples are numerous, serving as the springboard for the cult across southeast Asia. The popularity of Mazu worship in Taiwan area was partly attributed to Qing government’s military activities in the conquest of the island, to which the goddess helped with many miraculous interventions. In this sense, Mazu’s presence in Taiwan served to promote the imperial ideology. After taking over Taiwan, the Qing government sponsored the construction of new temples in Taiwan’s administrative centers, as recorded in the local gazetteer of the Taiwan prefecture. When the Qing government first took over the administration of Taiwan in 1727, the Intendent of the General Surveillance Circuit (

xundao), Wu Changzuo, initiated the construction of a Mazu temple, a Guandi temple, and a Guanyin hall in the southeast area of Taiwan.

44 District magistrates in the Taiwan prefecture were obligated to sponsor the construction of official Mazu temples in their designated districts. According to Harry Lamley, during the Qing dynasty era, the construction of official temples and shrines devoted to Mazu and other state-approved deities functioned to sanction the Qing government’s eventual takeover of Taiwan. He states that “This new seat of government was expected to play a civilizing role in the Ko-ma-lan region and to advance Chinese culture here”.

45 To promote Chinese culture in Taiwan, the Qing officials imported images of Mazu, Guanyin, and Guandi. As the devotion to Mazu took root, it served as a mark of imperial power that inscribed the Qing government’s agenda on the Taiwanese landscape and disciplined the local population.

46 In light of the widespread popularity of Mazu in Taiwan, Tischer has argued that her devotion, particularly the collective experience of pilgrimage, allows for the creation of a “cultural intimacy,” a deep sense of belonging among the Taiwanese. In turn, this personally felt, transformative ritual experience enables the production of a “spatially imagined community,” that construes Taiwan as a “Mazu nation.” While recognizing the role of Mazu in the construction of Taiwanese national identity, a focus on tourism calls us to adopt a different analytical scale, one that also understands the devotion of Mazu transnationally (Tischer himself acknowledges that Mazu is open to contestation and multiple interpretations. “To be sure, invocating a national community does not exhaust the range of interpretations borne in Mazu pilgrimages. Being claimed by the Chinese government makes Mazu a dubious ally for the Taiwanese national case, after all”).

47In modern times, all of Mazu’s devotees, regardless of their location, consider the ancestral temple at Meizhou as the sacred origin of Mazu worship and the “mother temple.” Most of the “branch” Mazu temples can trace their lineage to the mother temple through the ritual tradition of “dividing the incense” (

fenxiang) or “dividing efficacy” (

fenling).

48 To found any new branch temple, devotees and ritualists had to go to the ancestral temple to perform this ritual. They would infuse a new statue of the goddess with the incense fragrance of the Mazu statue in ancestral temple and would then take the sacralized statue to the new temple. By sacralizing a new statue of the goddess at the ancestral temple, the new temple, in effect, drew from the goddess’s efficacy and miraculous powers. The ritual of “dividing incense” also takes other forms, including picking up some incense ashes from ancestral temple’s burner and placing them in an urn that is then carried to the new sacred site. By bringing these incense ashes back to the new temple building, the new temple also built a strong affinal connection with the ancestral temple. From this moment on, the new temple and its enshrined statue will have an affiliation with the older temple that puts the new temple into a subordinate position. Through this “dividing incense” system, such relations of affiliation articulate a complex network of hundreds of higher and lower temples, of “mother-daughter” temples.

This ritual tradition can be traced back to the Song dynasty. As Liu Kezhuang wrote in

Baihumiao shieryun, “The numinous consort, a young girl, originated from the Meizhou Island through a slice of fragrant incense, through which her worship flourished all throughout Fujian province, and later spread all over China”.

49 Starting from the late Ming dynasty, the Mazu ancestral temple at Meizhou began spawning offering temples in Taiwan through the ritual of “dividing incense.” According to the statistics collected by Taiwanese scholars, “Since the first time an offspring temple was established in Taiwan through dividing incense, affiliated Mazu temples in Taiwan have flourished to over 2000”.

50Since the early 1980s, Mazu’s cult has served as a crucial vehicle to build contacts with the Taiwanese, attracting financial support from Taiwan and promoting the relationship between mainland and the island. According to Rubinstein, since the 1980s, the affiliated temples in Taiwan have been able to restore the bonds with the ancestral temple in Meizhou.

51 The special bond between the ancestral temple of Mazu and devotees in the Chinese diaspora attracts millions of overseas pilgrims annually. In order to sustain and renew the religious power of the Mazu temples in Taiwan, these affiliated temples periodically organize pilgrimages to the ancestral temple in Meizhou. These pilgrimages are called “incense-presenting trips.” For example, Zhenlan temple in Taiwan was one of the first ones that made a pilgrimage directly to the Meizhou ancestral temple in 1987, celebrating the millennial anniversary of Mazu’s ascension to heaven.

52 pilgrimage group of Zhenlan temple, consisting of 17 temple board members, brought a Mazu statue with them. When they arrived at the Meizhou temple, ritualists there performed the ritual of “dividing incense,” putting the Zhenlan temple’s Mazu statue in front of the altar of Meizhou Mazu to enjoy the incense and divide the goddess’ religious efficacy. The sacred objects brought back with the pilgrimage group included “a Meizhou Mazu statue, a carved stone steal, an embroidered altar skirt, and the incense burner and ashes from Meizhou temple”

53 that symbolizes the renewal of the direct relationship between the Zhenlan temple and the ancestral temple. The pioneering pilgrimage journey made by Zhenlan temple set a pattern that would be repeated by other temples in Taiwan. In recent years, there has been an increasing number of religious pilgrimages by Taiwanese worshippers of Mazu to the Meizhou temple.

From the Meizhou ancestral temple’s perspective, the increasing number of Taiwan religious pilgrims not only leads to more personal donations, which were crucial for the restoration of the temple in 1980s, but also to an explosion of religious tourism to Meizhou Island. Being aware of its privileged position as the most sacred pilgrimage site, the ancestral temple has developed the new ritual of “returning to mother’s home” (huinaingjia).

This ritual is based on the tradition of “dividing incense.” On special events, in particular on Mazu’s birthday and the day of “her ascension to heaven,” the Meizhou ancestral temple will invite Mazu devotees and affiliated Mazu temples to return to “the mother’s home”. The pilgrimage group, usually consisting of temple members and other devotees, bring their Mazu statue. The ancestral temple will then hold a small scale of sacrificial ceremony for the pilgrimage group. In this way, the Mazu statue brought by them also shows her homage to the original image at Meizhou. Then, the pilgrims will hold the statue of the affiliated temple and go around her with an incense burner from the Meizhou temple while whispering “Mazu is returning to mother’s home.” After presenting incense to the Meizhou mother, the statue of the affiliated temple will be put on the altar to enjoy the incense of the mother temple. The ritual ends with an exchange of souvenirs between temples.

“Returning to mother’s home” has two meanings. First, the relationship between Meizhou’s ancestral temple and other affiliated temples is understood as a mother and daughter kin relation. That is why pilgrimages from affiliated temples in Taiwan to the ancestral temple in Meizhou are seen as a “return to the mother’s home.” According to Steven Sangren, this kinship between the ancestral temple and affiliated temples is affinal rather than agnatic. Namely, belonging is determined through marriage, not exclusively by descent from shared male ancestors (fathers). As Sangren points out, “It is significant that the kinship metaphor used in describing the related phenomena of pilgrimages (chin-hsiang) and temple branching (fen-hsiang-literally, “dividing the incense burner”) is affinal rather than agnatic. The deity images present in branch temples are similar to brides who return on a customary visit to their natal homes (lao-niangchia). During annual pilgrimages these images are taken from branch temples (or from the temples of local territorial cults where Ma Tsu maybe worshiped as a subsidiary deity) and returned to home temples where they are passed over the incense burners and ritually rejuvenated”.

54 Just as the married daughter can gain succor and confidence from her mother upon returning home, renewing a link that may have been weakened by distance and time and by dwelling in another household, so too the secondary Mazu temples abroad can strengthen their religious legitimacy and authority through the pilgrimages to the Meizhou temple.

Second, “returning to mother’s home” is also a metaphor for the Chinese diaspora, retrieving its common cultural roots and establishing community identity. The trip to visit the “Meizhou mother ancestor” (

Meizhou mazu) is a journey back in space and time. Not only is it as if the married daughter who left the mother’s home for a distant marriage comes back, but also the pilgrimage signifies a return to a primordial place, a place where an extended spiritual family originated. The pilgrimage made by the Chinese diaspora is a reunion with the mother culture and a restoration of their common memory as both Chinese and Mazu devotees. Sangren puts it well: Mazu has the maternal power to bring together all the children in the family, producing “an inclusive effect among Taiwanese (uniting otherwise competitive Hakka, Chang-chou, and Ch’uan-chou factions)”.

55 Beyond that, the Meizhou mother has the power to unify all devotees throughout the world and to establish a shared transnational identity among them. As I indicated in the introduction, I follow Linda Basch’s and her colleagues’ pioneering definition of transnationalism, which is “the processes by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement. We call these processes transnationalism to emphasize that many immigrants today build social fields that cross geographic, cultural, and political borders”.

56 In the last two decades, the literature on transnationalism has grown exponentially, but at the heart of this approach is a pointed critique of “methodological nationalism,” the dominant perspective in the social sciences and humanities that takes the nation-state as a static, unified and given unit of analysis.

57 Without denying the continued centrality of the nation and national identity, the literature on transnationalism places the nation within multiple spatial scales, from the local to the global, that shape it and to which it creatively responds.

Adopting a transnational approach enriches our understanding of the cult of Mazu.

58 Through their pilgrimage to the Meizhou ancestral temple and their participation in powerful and highly emotive performances of a culture that is deemed foundational, the Chinese diaspora construct a common identity and a sense of belonging that transcend their geographic and political boundaries. As Yang points out, “it would seem that cross-strait Mazu pilgrimages are creating a regional ritual space and religious community of Chinese coastal peoples that do not conform to existing political borders”.

59The mix of traditional and newly-created rituals attract over 200,000 Chinese people living abroad to Meizhou temple annually.

60 Since 1989, when the first wave of Taiwanese pilgrims undertook their “presenting incense” trip to Meizhou, the ancestral temple has organized a variety of events to promote cultural, tourist, and commercial exchanges between overseas Chinese and mainland China. For example, the ancestral temple organized academic and cultural exchange conferences between Taiwan and mainland China.

61 In terms of the tourist exchanges, the ancestral temple organized a photography exhibition with the theme of “Affection and Beauty of Meizhou Island,” which showcased thousands of photographs from artists across the Taiwan strait. To celebrate the approval of Putian city as one of the tourist ports that is eligible to make direct trips across the Taiwan strait, the ancestral temple invited over 50 Mazu temples in Taiwan and 7000 Taiwan devotees to undertake a four-day pilgrimage. During the 10th Mazu Culture Tourist Festival, the event “Mazus in the world returning to mother’s home” (

tianxia mazu hui niangjia) attracted over 300 Mazu statues of affiliated temples. The commercial exchange is attested to by the “Mazu and Health” forum across the Taiwan strait which promotes the business cooperation between Putian and Taiwan companies. As a result, 18 business contracts worth a total of 7 billion dollars were signed.

By emphasizing its status as the birthplace of Mazu’s worship and as a symbol of cultural integration among the Chinese people in the mainland China and abroad, the new approaches adopted by the Meizhou temple have successfully attracted affiliated temples and overseas devotees, in particular Taiwanese devotees to undertake a pilgrimage to their ancestral and spiritual home.

The traditional ritual of “dividing incense” is crucial in building a transnational cultural community. The annually “returning to mother’s home” pilgrimage trip serves to renew the sense of belonging that stretches the bounds of the nation to include all those places where Chinese immigrants live. Tourism has played a major role in this unbounding of Mazu, from an imperial metaphor to a trope of global identity and belonging.

5. The Actors Underlying the Development of Religious Tourism in Modern China

The transformation of Mazu worship into religious tourism in modern China is not simply a product of changing dynamics in “the religious” and “tourism” fields. At a deeper level, it is a sign of radical changes in the larger sociopolitical environment. In this section, I will discuss the political and economic agencies that led to this transformation. Post-1978, mainland China witnessed a wave of reinventions and innovations of old religious traditions that have adapted them to a modern context. This wave was the product of a new religious policy adopted by Chinese governments, as well as changes in official discourses regarding the legitimacy of religions, the impact of market economics, and the actions of local government to boost the local economy. Let me take up each of these dynamics.

The revival of popular religious traditions, including Mazu’s cult across southeast China, was in large part made possible by a dramatic shift in the government’s attitudes to Chinese religions. Before the enactment of the new constitution and Document 19, all religions had to contend with the dominant ideology, Marxism, which defines religion as “the opium of the people.” With this understanding of religion, the Communist government asserted its supervision over religions by implementing religious policies that restricted the activities of religious institutions, priests, and believers. Popular religious practices were tagged as superstition, which was not protected by the law. However, the revision of the constitution adopted in 1982 and the implementation of “Document 19” that circulated in the same year ushered in a new period of religious tolerance. For instance, Document 19 states that “the basic policy the Party has adopted toward the religious question is that of respect for and protection of the freedom of religious belief”.

62 This religious liberty clause provides official justification for a restoration of popular religions and the protection of the freedom of individual religious belief. Along with the policy of religious tolerance, “official religious associations were reinstated, officially designated places of religious worship were reopened, and religious communities were allowed and even encouraged to engage in international exchanges with their coreligionists”.

63 This religious policy also distinguishes normal religious life from other illegal activities tagged as superstitions or evil cults. Normal religious activities permitted by the government and law include scripture chanting, ritual performance, self-cultivation, publishing religious books, and selling religious products. Religious activities, such as “divination, sorcery, exorcism, spirit procession, and fengshui,” were categorized as superstitions and illegal.

64 One policy in Document 19 emphasizes the tourist significance of some sacred sites with long history:

Churches and temples located at famous mountains and scenic resorts are not only religious sites, but also facilities with high historical and antique values. These churches and temples should be carefully maintained, the antiquity should be well preserved, the architecture should be properly renovated, the environment should be fully protected. In this way, these religious sites will become tourist sites with clean, peaceful, and beautiful environments.

65 In addition to the changing religious policy, another political factor that has contributed to the revival of Chinese popular religious traditions is the emergence of other channels for institutional legitimation, such as the Chinese government’s strong support for intangible cultural heritage. In 2004, PRC governments issued a decision to support the “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage,” which was first promulgated by The General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2003.

66 “Intangible cultural heritage,” as defined in the convention, comprises the following domains: “oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage; performing arts; social practices, rituals and festive events; knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; traditional craftsmanship”.

67 On the basis of the UNESCO convention, the Chinese government issued “Suggestions for Reinforcing Our National Efforts to Safeguard the Intangible Cultural Heritage,” which provides a detailed account of administrative procedures to implement the convention at a national level. According to the suggestions, the Ministry of Culture, together with provincial and county level cultural affairs bureaus, takes the responsibility to evaluate whether the items of traditional culture are qualified to be registered as intangible heritage. Once these items have been designated as such, they will benefit from special legal protection and financial support. This policy has opened a legal channel for popular religious practices to gain official recognition from central and local governments. As it happened during imperial China, recognition from the central government translates into legitimacy and authority, which, in turn, has served to increase the visibility of these practices and organizations and to attract more economic resources, including tourism. Thus, religious associations, in particular cults to popular deities and local ritual traditions, have enthusiastically devoted themselves to applying for the registration as intangible heritage. Now, major local cults to deities, such as Qingshui laozu, Mazu, and some cults to civilizing heroes, including Yu the great, Confucius, and the Yellow Emperor, are all inscribed in the list of cultural heritage protection. In 2009, UNESCO decided to inscribe Mazu worship on the list of cultural heritage protection for several reasons. First, Mazu worship is recognized by different social groups as a symbol of identity and is passed on as a continuous tradition from generation to generation. Second, the inclusion of Mazu worship into the list of “Intangible cultural heritage” promotes cultural diversity and human creativity. Third, actors at every level, from local temples and provincial and county level cultural affairs bureaus to the central government, are engaged in the promotion of the worship of Mazu, highlighting the significance of the cult. Fourth, the Mazu worship has been recognized by the Chinese Ministry of Culture as worthy of being included into the national list of “Intangible cultural heritage”.

68 In line with the policy of religious tolerance adopted by central government, local governments have also become important agents in the development of religious tourism. Specifically, local governments are actively involved in restoring and promoting religious institutions in their jurisdictions to bring income from tourism, as well as supporting the application of intangible cultural heritage to benefit from special funding by central government. In the case of Mazu worship, the government of Fujian province and the local government of Putian city where the ancestral temple is located have been at the forefront in the promotion of tourism to the temple. In fact, officials from the Fujian government and the Putian government actively participate in the Meizhou’s Mazu Cultural Tourist Festival. As described in the local government document entitled “Construction Planning of the Ancestral Temple”, the local government sponsored the restoration of Meizhou ancestral temple in 1980s in order to boost the development of local tourism.

Beyond political factors, the market economy has also played a significant role in the revitalization of Chinese popular religious traditions. As I hinted above in discussing how official recognition has translated into increased public visibility, the expansion of the market economy in China has opened more opportunities for temple associations to increase their incomes. Specifically, the operation, and even survival, of temples in a market economy are increasingly dependent on donations and income generated by tourism and the provision of ritual services. In this dramatic changing economic context, temples have shifted from having religious associations to becoming socioeconomic entities. For example, Shaolin temple now operates as a commercial complex that provides all kinds of Kungfu performances as commodities to attract tourists. This has allowed it to transform itself from a Buddhist temple to one of the most popular tourist sites in China. The abbot Shi Yongxin has been referred as the “CEO monk”.

69 Similarly, we saw how the association at Mazu’s ancestral temple has become more differentiated and institutionalized to serve non-ritual functions. To attract more donations from devotees, temples now have to provide commodified ritual services and religious goods, as well as to organize activities such as religious tourism which were not traditionally connected with worship.

70Last but not least, the renewal of popular Chinese religion and, in particular, the national and transnational spread of the devotion to Mazu, has been aided by the increasing effort to reunify mainland China and Taiwan. The late 1980s and 1990s, large-scale pilgrimage activities across the strait was witnessed. The central government has encouraged temples and devotees from overseas to rebuild their spiritual connection with the ancestral temples in mainland China, retrieving their lost cultural roots and building a common religious community. The construction of a shared sense of spiritual and cultural belonging dovetails with the government’s desire to promote China’s political reunification and to project its influence globally.

71 In line with the mainland state agencies, the Meizhou ancestral temple and other original temples of popular deities have reshaped themselves as symbols of cultural exchange and common community.