1. Introduction

From 2001–2004, there was a comedy drama on British Television’s Channel 4 called ‘Teachers’. The show portrayed a group of non-idealised British secondary school teachers navigating the stresses of the profession and each other. One of these misfits, Ben, played by Matthew Horne, was the RE teacher. The joke around this character was that he had changed religion multiple times in order to please the gods of different faiths, eventually concluding that atheism was the best option as it was impossible to please them all. The portrayal of an RE teacher as an Atheist was presented as the funniest part of the joke. This TV show played on the popular conflation of RE teaching and religiosity in a comedic twist. While we may still recognise this trope, is it supported by evidence? Empirically speaking, should RE teachers be assumed to be ‘religious’ (understood in the broadest sense); or could some be more like Ben from the TV programme who embraces atheism, thereby rendering the joke around his character obsolete? What are some of the key religious beliefs of secondary Religious Education (RE) teachers in England and Scotland? This paper seeks to address this epistemic question empirically.

This research is based on a 2017 dataset comprising teachers who at the time of response were teaching RE in Secondary schools in England and Scotland (11–18-year-old students). England and Scotland, though both part of the United Kingdom (UK) are separate educational jurisdictions, representing unique (and also comparable) historical developments and trajectories, as well as the reality of contemporary political devolution (see

Section 4 and

Section 5 below). This paper begins by contextualising these data through examining the limited existing research into the beliefs of RE teachers. Subsequently, the scholarly debate and evidence relating to secularisation, particularly in the UK, is explored as a theoretical perspective through which the data presented in this paper can be considered. Finally, prior to the data presentation, we argue for a granular, national, approach to understanding and researching RE. Our focus on England and Scotland is guided by our data response levels.

RE in England and Scotland is a mandatory aspect of the primary and secondary school curriculum. We present a brief account of the subject in each country in

Section 5 and

Section 6. Typically, it has evolved away from Christian instruction to a non-confessional, multi-tradition, approach. Our data reveal that the religious beliefs of those teaching the subject mirror the low levels of religious belief revealed in the most recent census surveys of these two countries, though with some interesting variations. Our research also allows us to investigate the qualifications of RE teachers and to cross-reference these with educational jurisdiction and (a)theistic beliefs.

2. Research into the Beliefs of RE Teachers

Within the UK and internationally, research into the beliefs of RE teachers is under-developed (

Baumfield 2012;

Van der Zee 2012;

Everington 2012); furthermore, research into RE teachers has tended to focus on those from Christian backgrounds (

Mead 2006;

Revell and Walters 2010;

Van der Want et al. 2009).

Everington et al. (

2011);

Sikes and Everington (

2001), and

Jackson and Everington (

2017), have, however, conducted research into the biographies of UK RE teachers. They contend that there is a link between the personal experience, belief, and commitments of RE teachers and their practice; and that RE teachers need to reflect on this relationship if they aspire to an impartial approach within the RE classroom. Jackson and Everington argue that ‘impartiality’ is more effective than the attempt to be ‘neutral’ in the classroom. They argue this can, in part, be achieved by teachers being transparent about their own identity. According to Jackson and Everington (ibid.), some with firmly held convictions (both theistic and atheistic) may struggle to achieve this impartiality:

We acknowledge that a teacher exhibiting a form of atheism which regards not only religions, but the study of religions as worthless pursuits would not be able to function effectively as an educational professional in the field. (

Jackson and Everington 2017, p. 9) That said, it may still be the case that in some contexts RE may be taught by non-specialists with no degree background in Religion or cognate areas (

Conroy 2016), and in certain circumstances these teachers may teach RE unwillingly. Research in the Scottish context into the creation of faculties of subject groupings also shows that, in some schools, where RE is grouped alongside Humanities subjects such as History and Geography, teachers qualified in the other disciplines within the faculty can be involved in teaching RE (

Anderson and Nixon 2010).

This might overlook the possibility that a teacher with strong religious beliefs might find it easy to be transparent about their own identity; conversely, those with no religious beliefs may erroneously consider themselves impartial. It would be unlikely that a person who regarded the study of religions as worthless would opt to be an RE teacher. However, in terms of an atheist RE teacher who regards religion as a worthless pursuit, Jackson and Everington point out that there are those who may have negative views of religion, but yet maintain an educational professionalism and make use of their own positions in contributing to an open and exploratory approach to the subject. This echoes the much earlier assertions of

Hull (

1975) that multi-faith RE makes it possible for the religious affiliation to be irrelevant to effective RE teaching. It is also reminiscent of the findings of

Hand and Pearce (

2011) study of teachers’ and pupils’ views on whether or not, and if so how, patriotism should be taught about in schools. They found that, regardless of their own attitudes to patriotism, most of the participants advocated an impartial approach in which young people were enabled to make up their own minds, and note:

[T]he general advocacy of school neutrality on patriotism did not appear to be a reflection of personal indecision about its value. More than half of the teachers and students surveyed agreed or strongly agreed with the proposition that it is a good thing for people to be patriotic. This suggests that many Respondents were alert to the impropriety of equating what one personally believes to be valuable with what it is justifiable to promote in schools.

That said, it is important to acknowledge that it may be an inferential leap to suggest that beliefs about patriotism may be of the same order as religious beliefs. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to infer that RE teachers might similarly distinguish between their personal beliefs about religion and how/what they teach about it. Jackson and Everington assert that:

[T]eachers with a wide variety of religious and non-religious commitments or perspectives are capable, in principle, of teaching an open and reflexive form of Religious Education.

Yet,

Sikes and Everington (

2001);

Wright (

1993) and

Copley (

1997) discuss how RE teachers are often viewed with suspicion and hostility; assumptions and projections of religiosity are often normative for those teaching the subject.

3. Religious Education in Theoretical Perspective: Secularisation

Consideration of the (ir)religious beliefs of teachers benefits from context. What are the sociological framings for these data and how would the data compare with evidence about the beliefs of those within wider UK society, and further with data from each of our identified nations? In terms of the data considered in this research, would the assumptions mentioned at the outset of this paper apply, meaning that RE teachers sit outside of sociological data, or would there be consonance between the RE profession and wider society in England and Scotland?

The British Social Attitudes survey, since its inception, increasingly presents a picture of religion in the UK in decline (

Natcen 2019). In 2018, over half (52%) of those sampled (n = 3879) self-identified as having ‘no religion’ (ibid 2019, p. 5); 64% of people aged 18–34 did not identify as belonging to a religion (ibid 2019, p. 15); and 43% of those brought up within a religion never attended religious services (ibid 2019, p. 9). Since the British Social Attitudes survey commenced in 1983, those self-identifying as ‘Christian’ has fallen from 66% to 38% of the population (ibid 2019, p. 5).

Scholars of secularisation provide various explanations for these significant changes. ‘Secularisation’ is a multi-valent term. It can be understood principally in theological terms; for others, it is a sociological concept. While some take a European perspective; others look globally.

Bruce (

2002,

2011,

2013,

2017) describes secularisation as a decline in:

The power, popularity, prestige, and plausibility of religion… eroded by such features of modernisation as individualism, consumerism, the relegation of religion to the private leisure sphere, the separation of church and state, and increased religious diversity.

Bruce charts this to the democratisation of consciousness in the 16th Century Reformation and presents a measurable decline in attendance and influence. For Bruce this is evident in every measure of religiosity captured in both census and social attitudes surveys, which commenced in the middle of the 19th century. For Bruce, secularisation is inevitable; a corollary of technologically enabled democratic thinking within plural societies. For him, the move to individual spirituality instead of religious affiliation is not the ‘tectonic shift’ imagined by

Heelas and Woodhead (

2008).

Davie (

1994,

2000,

2002,

2013) offers a different interpretation; the ‘mutation’ of religious thinking she imagines as a move (via belief without belonging, vicarious religious, the unchurching of society) from orthodoxy to heterodoxy, while certain metaphysical beliefs retain their currency and have not declined in step with affiliation and attendance. Putting to one side the contested nature of concepts such as ‘orthodoxy’ (from which ‘heterodoxy’ can be identified), we can identify here a theological understanding of ‘secularisation’ (a shift from ‘orthodoxy’) which is manifested sociologically.

Berger (

1999) offers a more global perspective, arguing that the world is as ‘furiously religious as it ever was’ (p. 2) and this is evident in, for example, the rise of Islam and Pentecostal Christianity. This global perspective, also echoed in

Berger et al. (

2008), is helpful in alerting us to the dangers of generalising from small geographical contexts, to making claims across countries and continents; parts of Europe may be the exception to a global picture of religious flourishing. Others have made the case, particularly in relation to the ‘American exception’, that religion flourishes when it is marketized and commodified, adopting the competitive nous to survive within the dominant capitalist paradigm (

Stark and Finke 2000;

Dennett 2007;

Gauthier 2017). Similarly, other writers have claimed that ‘secularisation’ is complex and nuanced, happening differently, depending on national context or history. For example,

Therborn (

1995, p. 274) argues that secularisation ‘has been an uneven process. It has affected the major Protestant Churches more strongly than the Catholic Church, and more fundamentalist brands of Protestantism least.’

Jagodzinski and Dobbelaere (

1995) posit that this may be down to differences in church hierarchy, views of the clergy as intermediaries, and emphasis on the individual within protestant traditions.

Brown (

2001,

2010), again focusing on the UK context, presents, like Bruce, an image of stark decline, which he attributes to the loss of gendered piety and the rise of women’s rights, beginning within the Second World War and surfacing further in the 1960s, aided by enhanced control of reproduction. According to Brown, who bases his claims on an analysis of twentieth century religious discourse, women were often the guarantors of piety within the household, and secularisation is given further traction when they no longer conform to traditional roles within the family.

Parker and Freathy (

2012) similarly identify the 1960s as significant in the de-Christianisation of British society. The 1960s is viewed as a time when multi-culturalism and the challenge to pre-existing hegemonies were on the rise. It is interesting to note that it is in the late 1960s that questions about the role and purpose of Religious Education (or Instruction) within schools in England and Scotland coalesced into moves to reform the subject (see

Section 4 below). Having outlined secularisation as one potential theoretical lens through which to understand RE and the empirical data presented in this paper, we now further lay a foundation for the interpretation of the data through arguing that RE should be understood in a granular national perspective.

In light of these sociological framings for the nature and extent of changes in the landscape of religious belief, this research seeks to cast light on the beliefs of those within the RE teaching profession; a subject which has itself adapted to sociological change in terms of content and pedagogy (see discussion below about the trajectories of change in English and Scottish RE). In terms of the aforementioned sociologists of religion, might it be the case that Bruce’s inevitable secularisation thesis is evident in the RE profession? Or has the pluralism of the 1960s discussed by Brown filtered into the teaching profession, leading to increasing diversity of religious and (a)theistic positioning? Could it be that RE teachers would be exemplars of Davie’s thesis about the mutation of religious identity, whereby many retain theistic conviction but without formal affiliation?

4. RE in National Perspective: The Case for a Granular Approach

Broad developments germane to RE have taken place within the UK and internationally, charted both in research literature (

Jackson 2013) and in international policy publications from organizations such as

The Office for Security and Co-operation in Europe (

2007). These examples chart, across nations within the European continent, pressure on RE in the face of societal change, and changes in educational philosophy, to adopt a multi-religious approach (including a move towards the inclusion of non-religious worldviews), and in many cases across Europe, while maintaining sensitivity to confessional statutes.

The extent and nature of these developments are contested, as is what constitutes viable pedagogies for school RE. We aim to refine this discussion further by exploring any differences between two separate educational jurisdictions within the UK: England and Scotland. Erroneously, distinctions between educational jurisdictions are often ignored within the Academy. For example,

Barnes (

2006), in an article ostensibly about ‘British’ RE cites Working Paper 36 (which only applied to England and Wales) as applying to the subject across Britain, with no acknowledgement of developments in Scotland and Northern Ireland, which, though often similar, are not the same. Other papers on ‘British education’ similarly ignore the reality of a separate Scottish jurisdiction. For example,

Hella and Wright (

2009) wrongly state that education UK-wide was framed by the 1988 Education Act when said Act only applied to England and Wales. Similarly,

Slee (

1989) conflates British with English RE when considering the implications of the 1987 Education Reform Bill. While we recognise the four nations of the UK, this paper concerns England and Scotland as a result of both the weighting of responses to our survey and our own national expertise.

To distinguish between nations, as we do above, is not to ignore similarities.

Roger (

1990) suggests that Scottish educational policy often follows England, citing the chronological and thematic closeness of the 1870 (England) and 1872 (Scotland) Education Acts as an example. In more recent years, this can also be traced with regard to RE. England and Wales’ Durham Report (

Commission on Religious Education 1970) and Working Paper 36 (

Schools Council 1971), and Scotland’s Millar Report (

Scottish Education Department (SED) 1972) do indeed share a lot and it is in no ways contentious to suggest that very similar (and in many cases identical) cultural and academic factors were influential in the formation of these documents. These reports intended to address the perceived failings of Religious ‘Instruction’ in an increasingly pluralistic and secular UK, albeit in English and Scottish contexts, respectively. These reports appeal to Educationalists advocating a child-centred, non-confessional, approach to RE and seek to establish the subject on educational grounds as the ‘fourth R’ (

Commission on Religious Education 1970, p. 59). They argued for the professionalisation of RE teachers and the establishment of professional bodies (Advisors) to oversee subsequent development in the subject. These reports advocated an approach that is exploratory rather than confessional.

If education is culture perpetuating itself (McIntyre [undated], cited in

Jackson 1982) then we are, therefore, perhaps able to discern a degree of cultural homogeneity between Scotland and England.

Walker (

1994) argues further that Scottish education has been systematically anglicised, particularly after the Union of the Crowns in 1707. Though the scope of the present paper is far narrower in that it focuses on factors affecting change in one curricular area, rather than Scottish education in its entirety; perhaps wider international issues and movements are more causally significant in leading to changes in Scotland (albeit solely in the field of RE) than some anglicising trend. This lends credence to the views of Humes (

cited in Walker 1994, p. 220) that the anglicising theory ‘fails to take account of the over-arching concepts and ideas which go beyond nationality and help shape the perceptions of men and women in many different cultures’.

Scotland (5.42 million) is a great deal smaller in terms of population than England (55.62 million) (

The Office for National Statistics 2012). In addition to the issue of size, the lack of published research into the development of specifically Scottish non-denominational RE (

Nixon 2008a,

2008b,

2009,

2012,

2013a,

2013b,

2013c;

Grant and Matemba (

2013);

Franchi and Robinson (

2018) and

Scholes (

2020) aside), may, in part, explain the conflation of English and Scottish RE.

However, Scotland has separate educational, legislative, and ecclesiastical traditions. Of these three traditions, it may be the latter that has been most influential in terms of RE and how it has developed in Scotland. In 1560, John Knox published the Book of Common Discipline in Scotland. This was a manifesto for a school in every parish; a vision of a country where every citizen should be educated (

Knox 1560). The Presbyterian vision which has dominated Scottish public life was modelled on Calvin’s Geneva, with the aspiration that everyone was priest, where any one of any class could access learning in service to their salvation. While education in Scotland adopted the myth of the lad o’pairts (

Paterson 2000;

Anderson 2008) where everyone could, in principle, enter the university; this was not the case, to the same degree, in England (

Iannelli 2007) where Thomas Hardy, in 1894, captured the exclusion of the Working Classes from the academy in his tragically dark Jude the Obscure. It is perhaps simplistic to distinguish between the two nations thus, or for such narratives to be politicised. However, at the present time, these mythologies may still bear fruit. Whilst in Scotland undergraduates pay no tuition fees; the opposite is true in England where students have been paying tuition fees since 2012, a period, incidentally, in which

The British Academy (

2019) charts the decline of the study of Religious Studies and Theology within English universities in particular, by making overt links to the re-introduction of fees.

As stated earlier, Bruce and others (

Bruce 2002,

2011,

2017;

Gregory 2017) link the decline of Christian churches in Britain to the Reformation. Ironically, it seems Luther’s stand of some 500 years ago may have been influential in the creation of the modern secular mindset. ‘Here I stand, I can do no other’ may be the slogan of our individualistic age (

Gregory 2017), his protest modelling the possibility of defiance of hegemonic institutions. Could this be evidenced particularly in terms of secularisation in those countries which adopted predominantly protestant theologies? Might Presbyterianism, with its flatter ecclesiastical structure and more mundane theology (vis à vis Catholicism or Anglicism) be more prone to decline?

In light of what we have explored about secularisation and the importance of differentiating between in England and Scotland in considering RE, the question emerges: what are the religious beliefs of RE teachers in contemporary England and Scotland? We now turn to a more specific look at how RE is framed in England and in Scotland, particularly with a view to how teachers in these jurisdictions are trained and what qualifications are required to become an RE teacher. Below are brief accounts of the status and content of RE; census data (which provide comparison with the British Social Attitudes survey cited above); and what routes and requirements apply with regard to becoming an RE teacher in England and Scotland. This will set the context for our consideration of empirical data in the pursuit of answering the question: What are the (ir)religious beliefs of RE teachers?

5. RE in England

5.1. Curricular Requirements in England

RE in England is required to be taught in all state-funded schools as part of the compulsory curriculum for all school-aged children. Though this requirement includes the 16–18 curriculum, it is seldom taught as part of the regular timetable at this stage, unless students opt to take an examination class in a relevant subject. Though, in 1996, Dearing recommended that 5% (or roughly one hour per week) of curriculum time be designated for RE, time for RE varies greatly. Most schools of a religious character meet or exceed the 5% recommendation, but others fall far below this with many offering no timetabled RE at all (

NATRE 2017). Some primary school pupils have less than one hour of RE per week (

NATRE 2016).

Though a statutory requirement, RE is not a part of the National Curriculum. The only national requirement is that RE should ‘reflect the fact that the religious traditions in Great Britain are in the main Christian whilst taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in Great Britain’ (

Department for Children, Schools and Families 2010). RE curricula are determined according to school type. Each Local Authority (LA) regularly convenes an Agreed Syllabus Conference whose responsibility it is to determine LA’s Locally Agreed Syllabus for Religious Education. Community schools (funded through LAs) are required to follow their Locally Agreed syllabus. Some schools of a religious character are also required to follow their Locally Agreed syllabus; in others RE is determined by the school’s governing body which usually stipulates a syllabus both in keeping with the denominational priorities of the school and conforming with national requirements.

There are an increasing number of Academies and Free Schools in England (

Hilton 2018;

UK Government 2021). These receive their funding directly from the state, rather than through LAs. These schools are not required to follow their Locally Agreed Syllabus, but many do. The type of RE in Academies and Free Schools is determined by the type of funding agreement with the government; in practice, many adopt their Locally Agreed Syllabus at least in part, with RE in schools of a religious character reflecting denominational affiliations (

Jackson 2013;

Department of Education 2012).

Across the range of school types, in addition to the content required nationally, many RE curricula include philosophy and ethics. In 2018, the report of the Commission on RE (2018) identified variation in provision across English schools, set against social and political changes, as well as variations across school governance models in England. The report argued for the place of the subject, as well as re-imagining the scope and title of the subject, as ‘Religion and Worldviews’.

5.2. Census Data

The census which covers the population of England has England and Wales in its jurisdiction, hence the inclusion of data covering Wales in this section. Though the census is of two countries, when considering the extent to which the data represent England it is worth noting that the population of Wales is relatively small (2,903,000 in 2001, and 3,063,000 in 2011). The 2001 and 2011 census surveys of England and Wales included the question ‘What is your religion?’’ (

The Office for National Statistics 2012). These were the first census surveys to include a question on religion since 1851. Despite a campaign by Humanists UK (

https://humanism.org.uk/2020/07/20/2021-census-to-continue-to-use-leading-religion-question/, accessed on 10 January 2021), this question with the same wording, considered by Humanists UK to be leading, remains for the 2021 census survey. It will retain its status as the only voluntary question in the census survey.

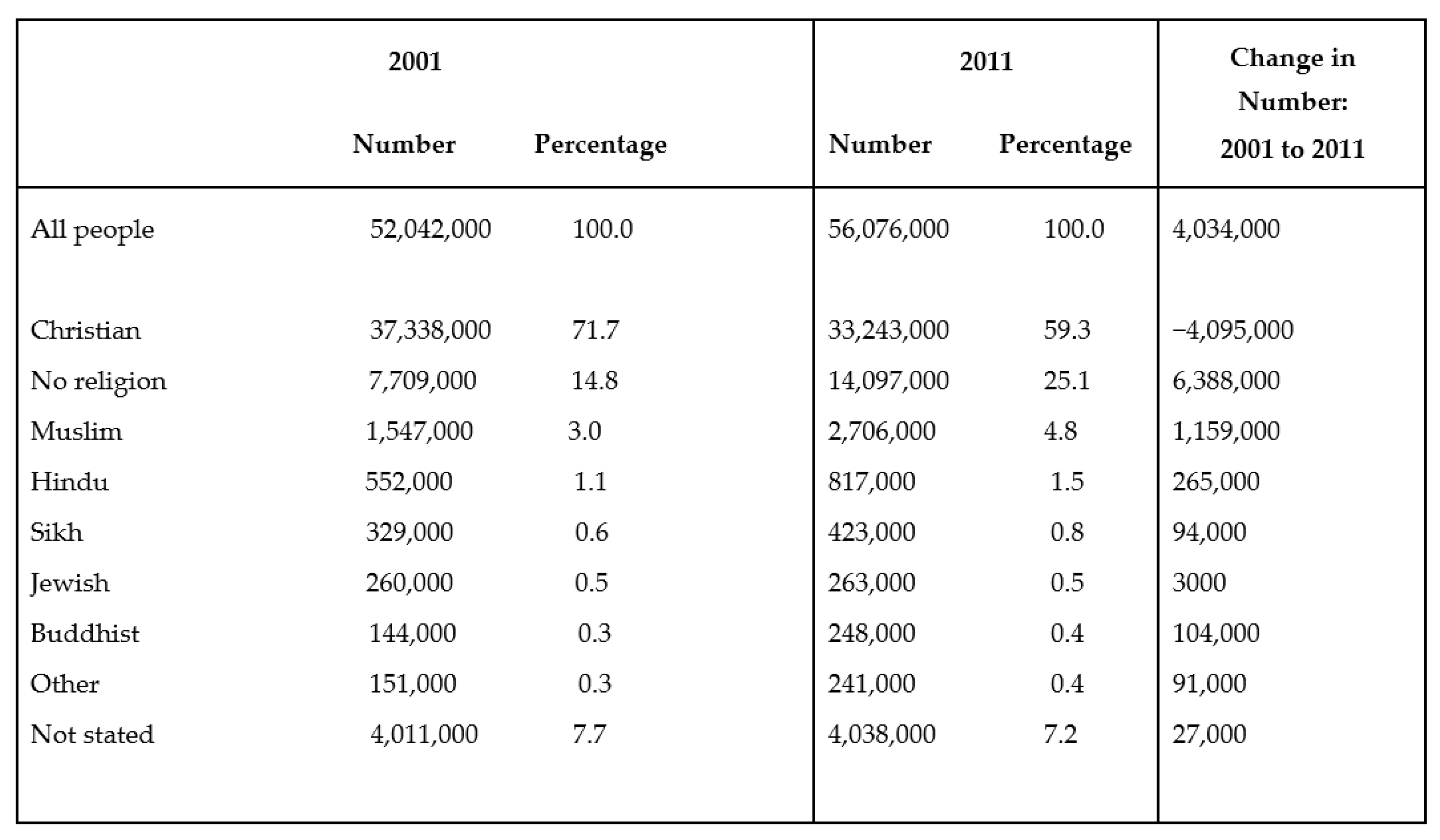

The 2011 census data (see

Figure 1) indicate that there were four million fewer self-identified Christians in England and Wales than in 2001 (a drop from 72% in 2001 down to 59% in 2011):

In 2001, 15% identified as having ‘no religion’, rising to 25% in 2011. Collectively, faith communities other than Christianity identified in the census amounted to 9% of the population in 2011, while 7% did not state their religion. In 2011, ‘others’ included: 56,620 Pagans; 2418 Scientologists; 650 new age; 176,632 Jedi; 1893 Satanist; and 6242 answered ‘heavy metal’. We look forward to the 2021 census survey, to see if the trends suggested by changes from 2001 to 2011 bear out.

5.3. Training to Be an RE Teacher in England

In Local Authority state-funded schools, teachers must have Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) to be able to teach. Academy, Free, and Independent schools can employ teachers without QTS, but in practice, most require QTS. QTS can be achieved by successfully completing an Initial Teacher Education programme, such as a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE). Applicants are required to have the minimum of a C in GCSE English Language and GCSE Mathematics. Some providers require students to have a degree in a relevant subject, but this is not stipulated by Government.

6. RE in Scotland

6.1. Curricular Requirements in Scotland

In Scotland, 85% of schools teach Religious and Moral Education (RME) in non-denominational schools, while 15% teach in a denominational context (

McKinney 2008). The Curriculum (for Excellence) places RE alongside seven other curriculum areas (

Education Scotland 2019). RE is a part of the ‘Broad General Education’, typically until the age of 15–16; though the statutory guidance, like England, states that it should be mandatory until age 18. A range of nationally certificated courses and qualifications exist for pupils from age 15–18; at this level the subject is called Religious, Moral and Philosophical Studies (

Nixon 2013a).

The guidance for the non-denominational RE curriculum is that Christianity must be an aspect of provision (to reflect the influence of Christianity and develop cultural literacy) (

Education Scotland 2019). The curriculum guidance is structured under three strands: Christianity; World Religions Selected for Study; and Development of Beliefs and Values. Within these strands, there are three further curriculum organisers: Beliefs; Values and Issues; and Practices and Traditions. The Scottish Government also provides national Experiences and Outcomes, and Benchmarks, for RE provision, with linked guidance and exemplification (ibid).

6.2. Census Data

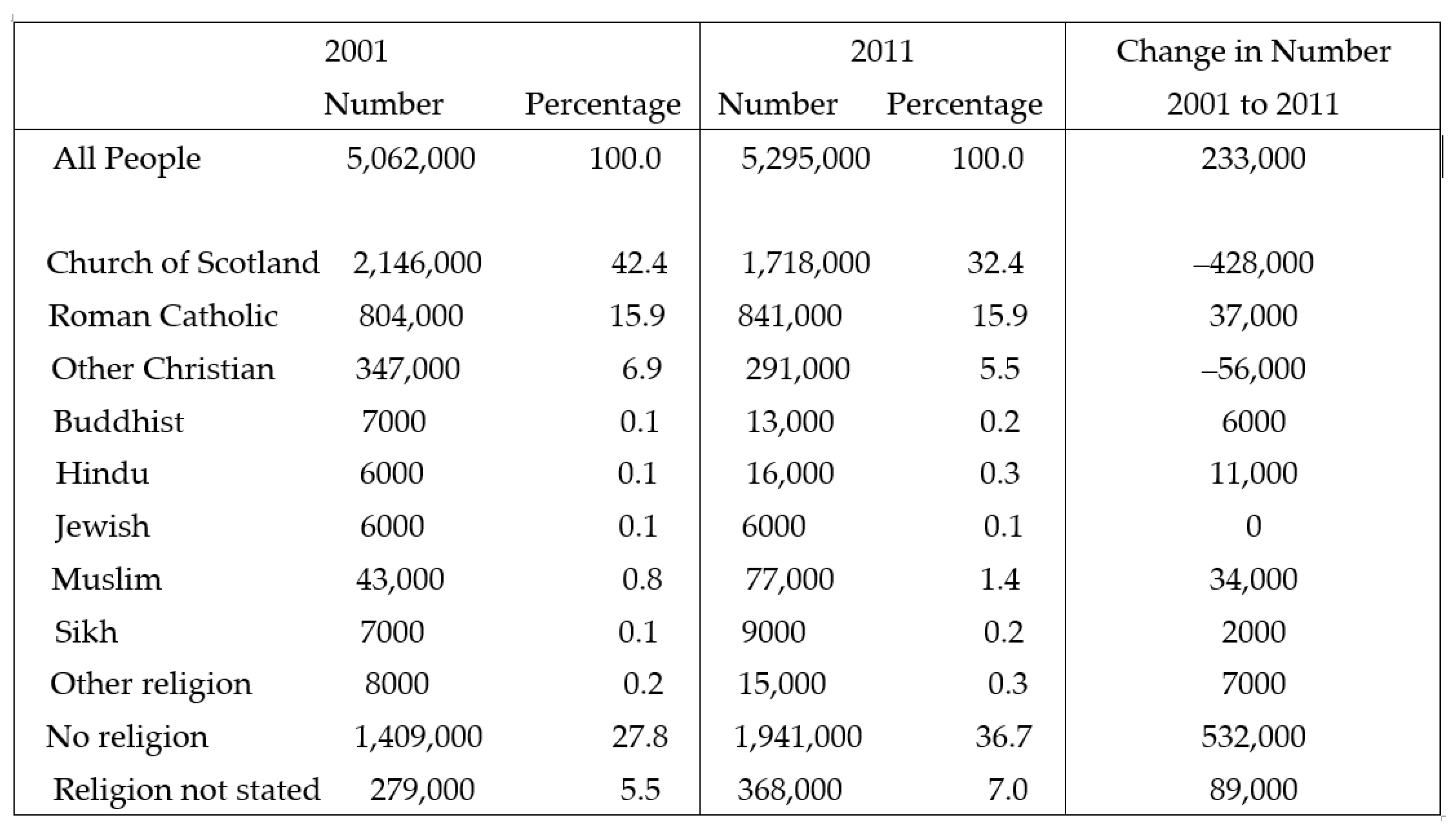

The following are notable aspects of the Scottish census and comparisons with the English and Wales census, and British Social Attitudes Survey:

For the first time, those identifying as ‘Church of Scotland’ (32.4%) were less than those of ‘No Religion’ (36.7%). This is notable for the Church of Scotland is the national church and plays a role in the civic life of the nation;

The number of those identifying as ‘Roman Catholic’ did not decline, compared to the ‘Church of Scotland’ and ‘Other Christian’ categories;

The number of those identifying as ‘No Religion’ (36.7%) is lower than the British Social Attitudes Survey (53%), and

Scotland has more identifying as ‘No Religion’ (36.7%) than ‘England’ (25.1%)

6.3. Becoming an RE teacher in Scotland

Entry to the teaching profession in Scotland is regulated by the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) who set entry requirements and the standards for entry into teaching (

GTCS 2019). The GTCS Memorandum for Entry into Teaching requires either a combined or concurrent degree, which include the study of an RE related subject, education and school placement, or a one-year Professional Graduate Diploma (PGDE) following a degree in an RE related area.

For the latter, applicants must have credits from two or more of these areas: Religious Studies, Philosophy, Theology, Divinity, Sociology of Religion, Anthropology of Religion and Psychology of Religion. Those who wish to teach within the Roman Catholic sector in Scotland require credits in Religious Studies, Theology or Divinity. Like England, there are also pre-requisites for literacy and numeracy in order to qualify to be a Teacher.

Having considered theoretical currents relating to secularisation and the requirements for Teacher Education in England and Scotland, along with the particular natures of RE in these national contexts; we will now draw upon our empirical data in order to establish the qualifications and (ir)religious beliefs of RE teachers.

7. Scope and Methodology

The research presented in this paper is part of a larger study of RE teachers across the UK conducted in 2017 which included questions about demographics, spirituality, political affiliation, and attitudes towards, and understandings of, religion. This study consisted of an online survey distributed using professional networks, Standing Advisory Councils on Religious Education (SACREs), and RE teacher social media groups (N = 465 after exclusions). Research from the larger study, concerned with RE teachers’ beliefs about religion, can be found in

Smith et al. (

2018). However, we have included, in this paper, questions relating to the perception of religion as dangerous, and whether religion should be taught positively, in order to cross-tabulate these responses with degree backgrounds and (ir)religious beliefs (see below).

The survey provided UK geographical coverage and confidentiality for Respondents (not merely an ethical consideration, but an important aspect for data integrity when dealing with a sensitive subject area). The survey employed a mixed-methods approach; for example, using 5-point Likert Scales, as well as qualitative open-text comment boxes, which provided further nuance to the quantitative responses.

The focus of this paper is upon current (at the time of response) Secondary and Sixth-Form Teacher-Respondents (n = 355) domiciled in England (n = 238) and Scotland (n = 117). Wales (n = 4) and Northern Ireland (n = 5) are excluded due to limited response levels. While the largest group of Respondents from England and Scotland have been teaching for 6–10 years (Q.3: n = 99 or 27.97% of Respondents [England: n = 70; Scotland: n = 29]), a range of responses by age was evident. The sectoral coverage (Q.4) evident in responses (n = 355 [England: n = 238; Scotland: n = 117]) captured the multifarious nature of education in the UK; however, State Secondary was the majority representation (n = 222 or 62.54%) with a significant weighting to State Secondary in the Scottish context (England: n = 116 or 48.74%; Scotland: n = 106 or 90.60%). Responses (n = 355) were weighted to those in Suburban (Q.5: n = 143 or 40.28%. England: n = 96 or 40.34%; Scotland: n = 47 or 40.17%) and Urban (n = 137 or 38.59%. England: n = 95 or 39.92%; Scotland: n = 42 or 35.90%) areas.

Respondents (n = 354) were concentrated between ages 25 and 54 (Q.7: 25–34: n = 122 or 34.46%; England: n = 81 or 34.18%; Scotland: n = 41 or 35.04%. 35–44: n = 118 or 33.33%; England: n = 80 or 33.76%; Scotland: n = 38 or 32.48%. 45–54: n = 68 or 19.21%; England: n = 48 or 20.25%; Scotland: n = 20 or 17.09%). Female Respondents (n = 256 or 72.32%; England: n = 161 or 67.93%; Scotland: n = 95 or 81.20%) outweighed males (n = 98 or 27.68%; England: n = 76 or 32.07%; Scotland: n = 22 or 18.80%). Respondents overwhelmingly self-identified as White: English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British (Q.11: n = 309 or 87.54%; England: n = 200 or 84.75%; Scotland: n = 109 or 93.16%). Concerning ‘sexual orientation’ (Q.12: n = 349), Heterosexual/Straight comprised the majority of responses (n = 314 or 89.97%; England: n = 208 or 89.66%; Scotland: n = 106 or 90.60%). The majority of Respondents’ schools (Q.13: n = 350) did not have a ‘religious character’ (n = 230 or 65.71%; England: n = 156 or 66.95%; Scotland: n = 74 or 63.25%).

8. Data

The graphs below, accompanied by tables, illustrate the responses to the following questions/prompts, and cross-tabulations of a selection of these:

Q6: Please specify any degree(s) that you have. Select as many as apply.

Q15: Concerning belief in God(s), are you?

Cross-tabulation of degree background Q6 and Q15 belief in God(s).

Q16: What is your religion?

Cross-tabulation of degree background Q6 and Q16 religion.

Q23: Religion is Dangerous.

Cross-tabulation of Q6 degree background and Q23 Religion is dangerous.

Q24: Religion should be taught in a positive way in Religious Education.

Cross-tabulation of Q15 belief about God(s) and Q24 Religion should be taught in a positive way in Religious Education.

The graphs and summaries in subsequent sections are presented with minimal commentary, as key findings are articulated in the

Section 9 of this paper (For a detailed examination of questions 23 and 24,

Nixon 2018).

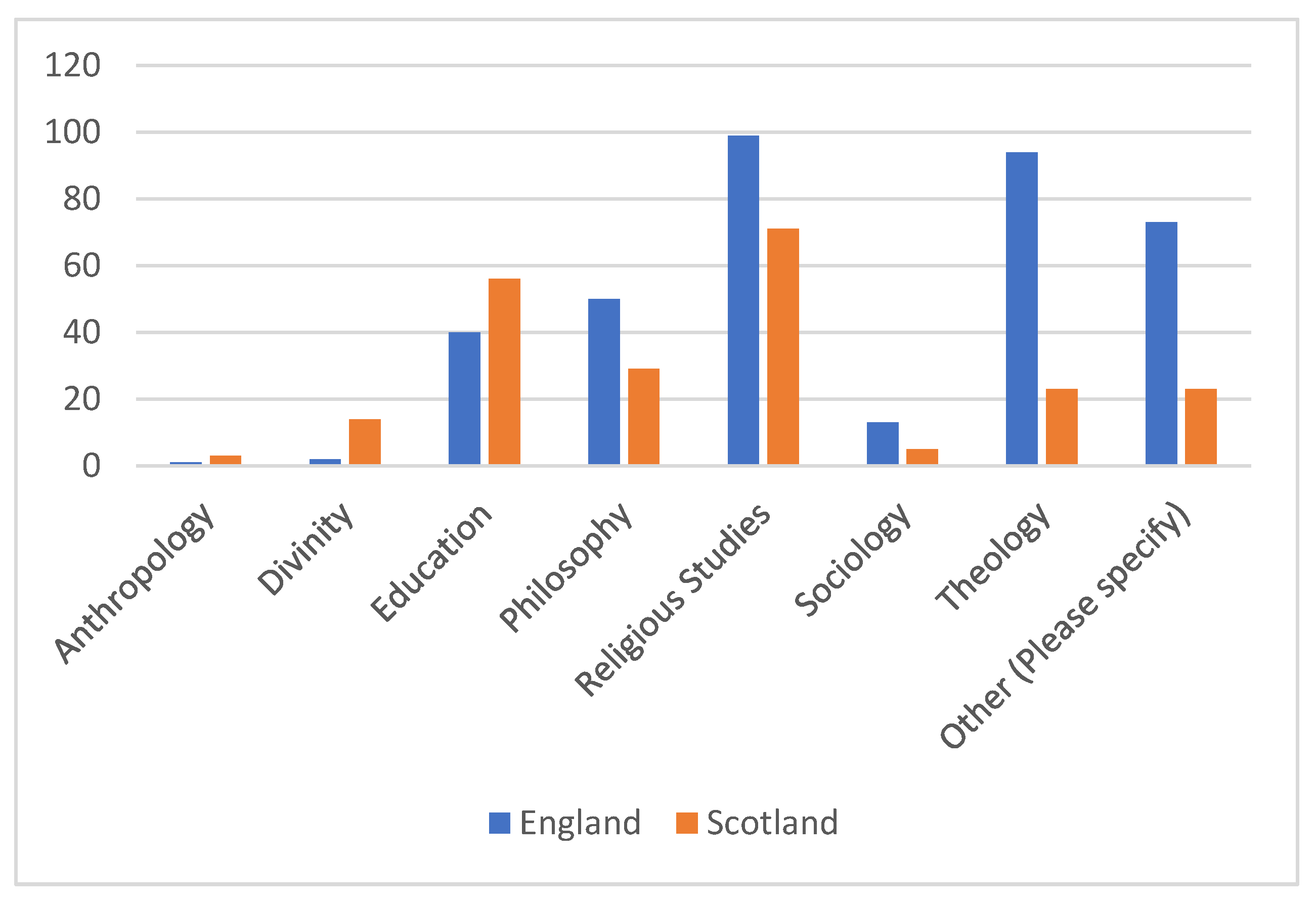

8.1. The Degree Background of Secondary RE Teachers

Q6: ‘Please specify any degrees that you have. Select as many as apply’.

In

Figure 3, a range of pre-selected academic disciplines were considered by the authors to be common among prospective RE teachers, whilst an ‘other’ category afforded the opportunity to capture data outside of these areas. Of the pre-selected response categories, ‘Anthropology’ has a particularly small response rate. It has been included, however, to accurately reflect the response categories available to the participants.

The ‘other’ category was more prevalent in England (n = 72 after 1 exclusion) than in Scotland (n = 23). In England, responses ranged beyond cognate areas from: ‘Business Administration’; ‘Drama’; ‘English Literature’; ‘Environmental Studies…BSc’; ‘Archaeology’; ‘English and Criminology’; ‘French’; ‘Educational Leadership and Management’; to ‘Physical Education’. In Scotland, responses included ‘Film and Media’; ‘Art History’; and ‘Scottish Literature’.

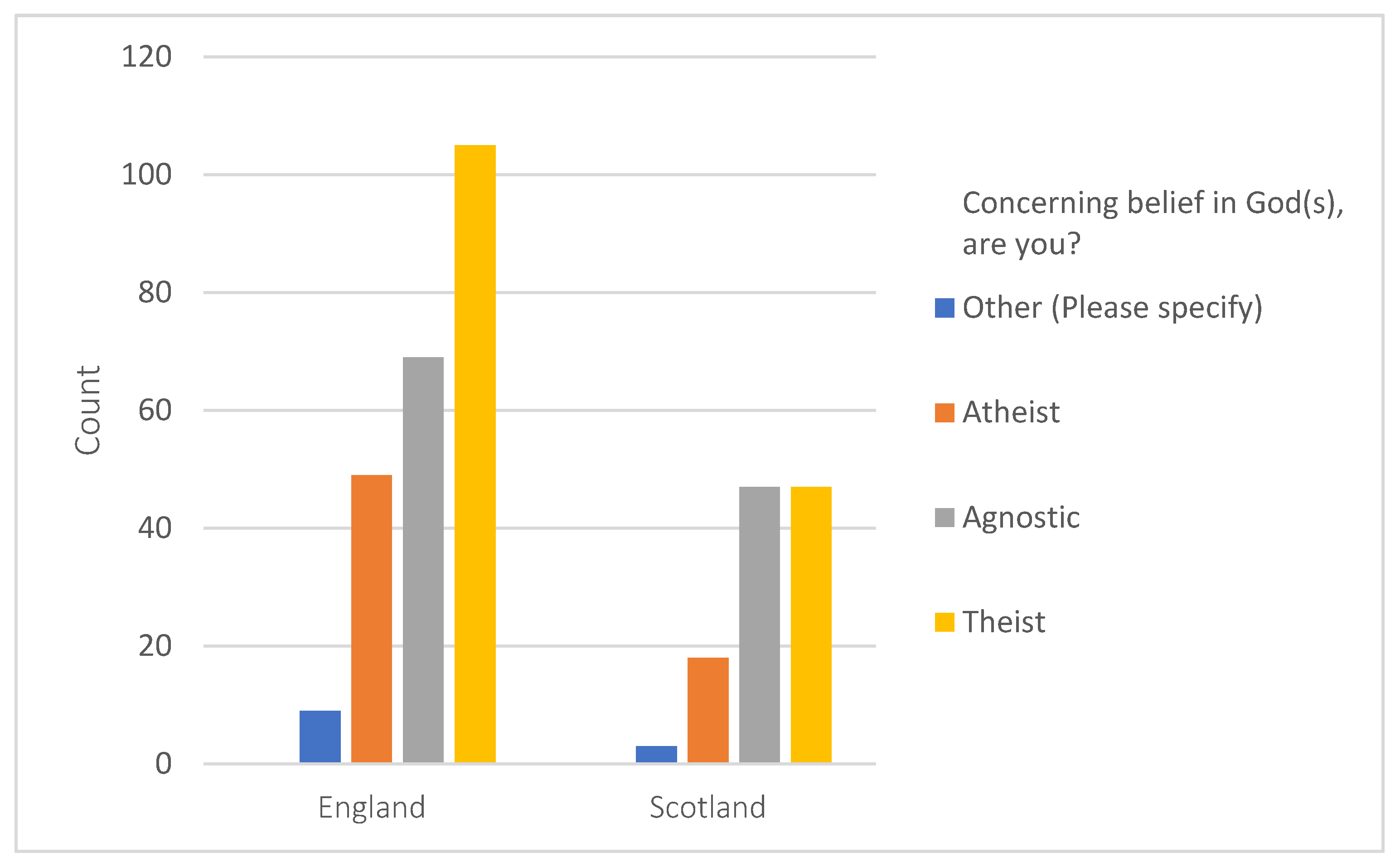

8.2. Belief in God among Secondary RE Teachers

Q15: ‘Concerning belief in God(s), are you?

In addition to the views represented on

Figure 4 a range of ‘other’ responses were also offered for this question (England n = 9; Scotland n = 3). In England, these included ‘More complicated’, ‘Monist’, ‘Impersonal transcendent’, ‘Deist’, ‘religious atheist’, ‘Animist/polytheist’, and ‘Epistemologically agnostic, pragmatically atheist’. In Scotland, ‘Agnostic atheist’, ‘Panentheist’, and ‘I believe there is something but I’m not classifying it as God’ feature.

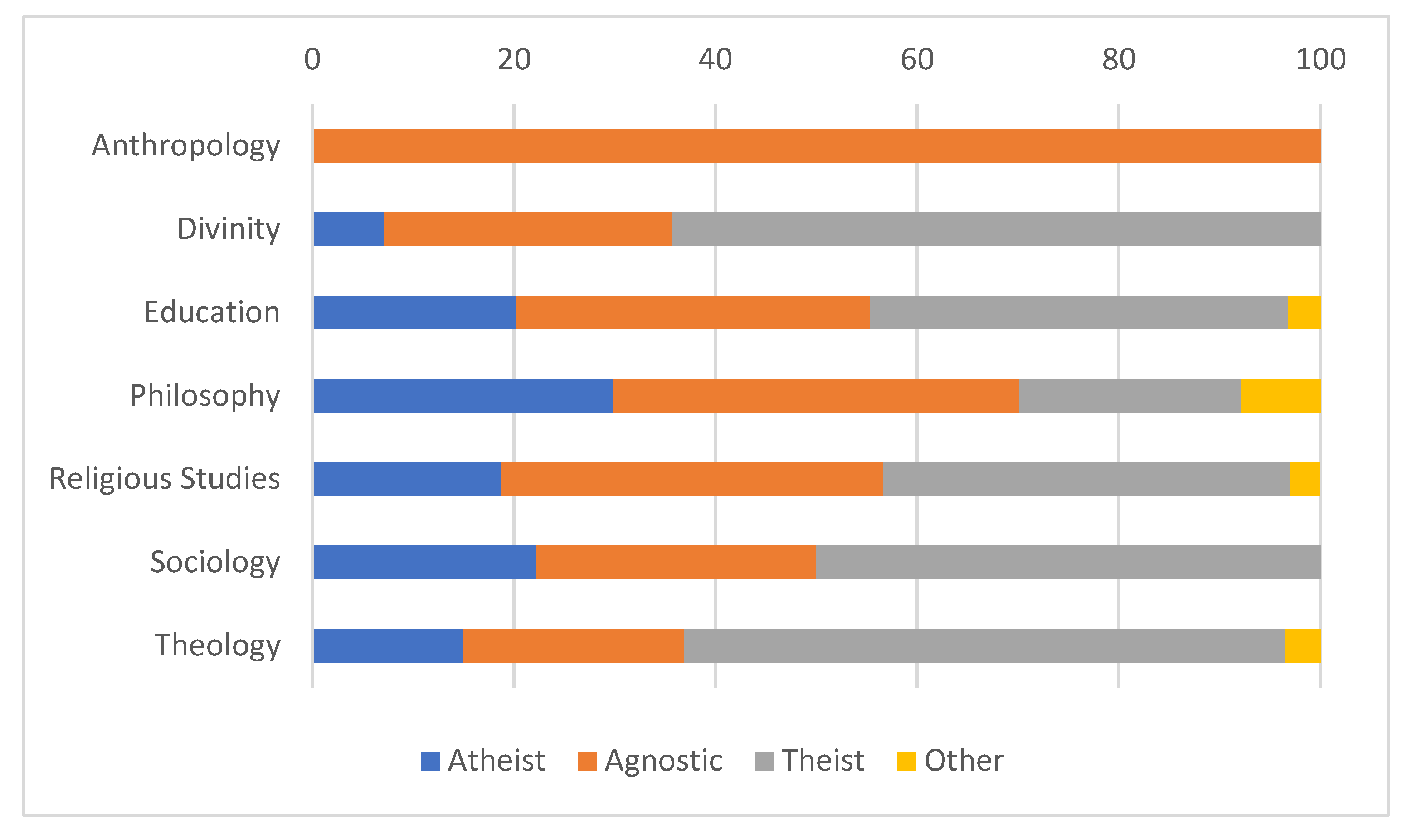

8.3. Belief in God Cross-Tabulated with Degree Background

Q15: ‘Concerning belief in God(s), are you?’

Figure 5 shows degree background cross-tabulated with belief in God. As previously discussed, (Cf. 8.1) the inclusion of Anthropology reflects the pre-selected respondent categories. While the other disciplinary categories, above, are sufficiently weighted to be represented in percentage terms, caution is required concerning Anthropology due to its low response level.

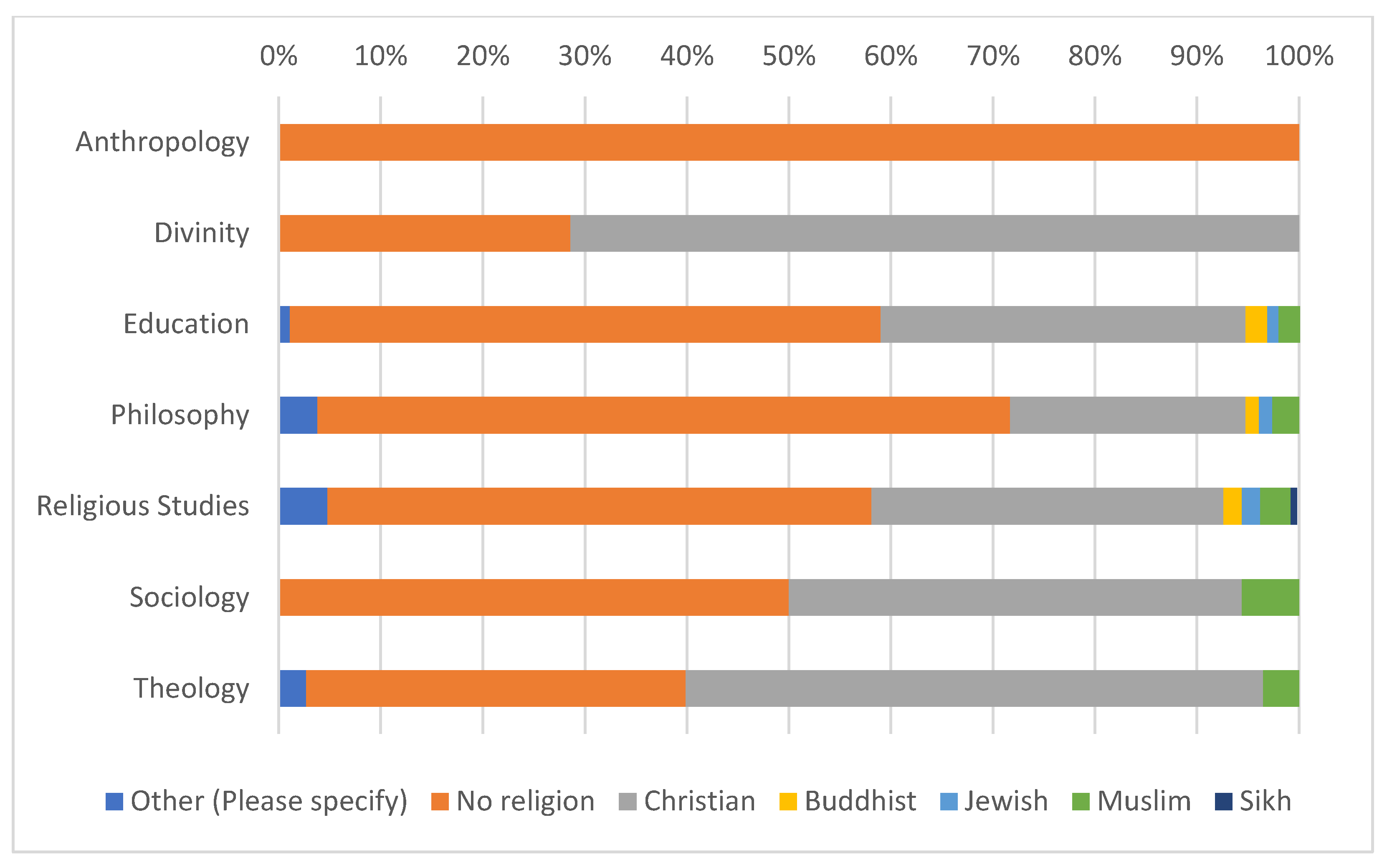

8.4. The Religion of Secondary RE Teachers

Q16: ‘What is your religion?’

In addition to the religions represented in

Figure 6 a range of ‘other’ responses featured (England n = 10; Scotland n = 2). In England, these included ‘Still undecided!!’, ‘No organised religion’, ‘My philosophy is mainly Buddhist but could also be described as monist pantheist in a Western philosophical sense’, ‘I identify as Humanist but understand that’s complex as to whether it is a religion’, ‘Pagan (Druid)’, ‘unsure’, ‘Jain’, and ‘Humanist’. In Scotland, ‘Christian/Buddhist’ and ‘Agnostic’ were listed.

8.5. Religion of Secondary RE Teachers Cross-Tabulated with Degree Background

As stated previously caution is required in relation to those with Anthropology given the small numbers.

Figure 7 reveals that the majority of those with Divinity and Theology degrees identified as Christian, albeit with large minorities in both disciplines being non-religious. A significant majority of Philosophy graduates were non-religious and the majority of Religious Studies students also identified as non-religious.

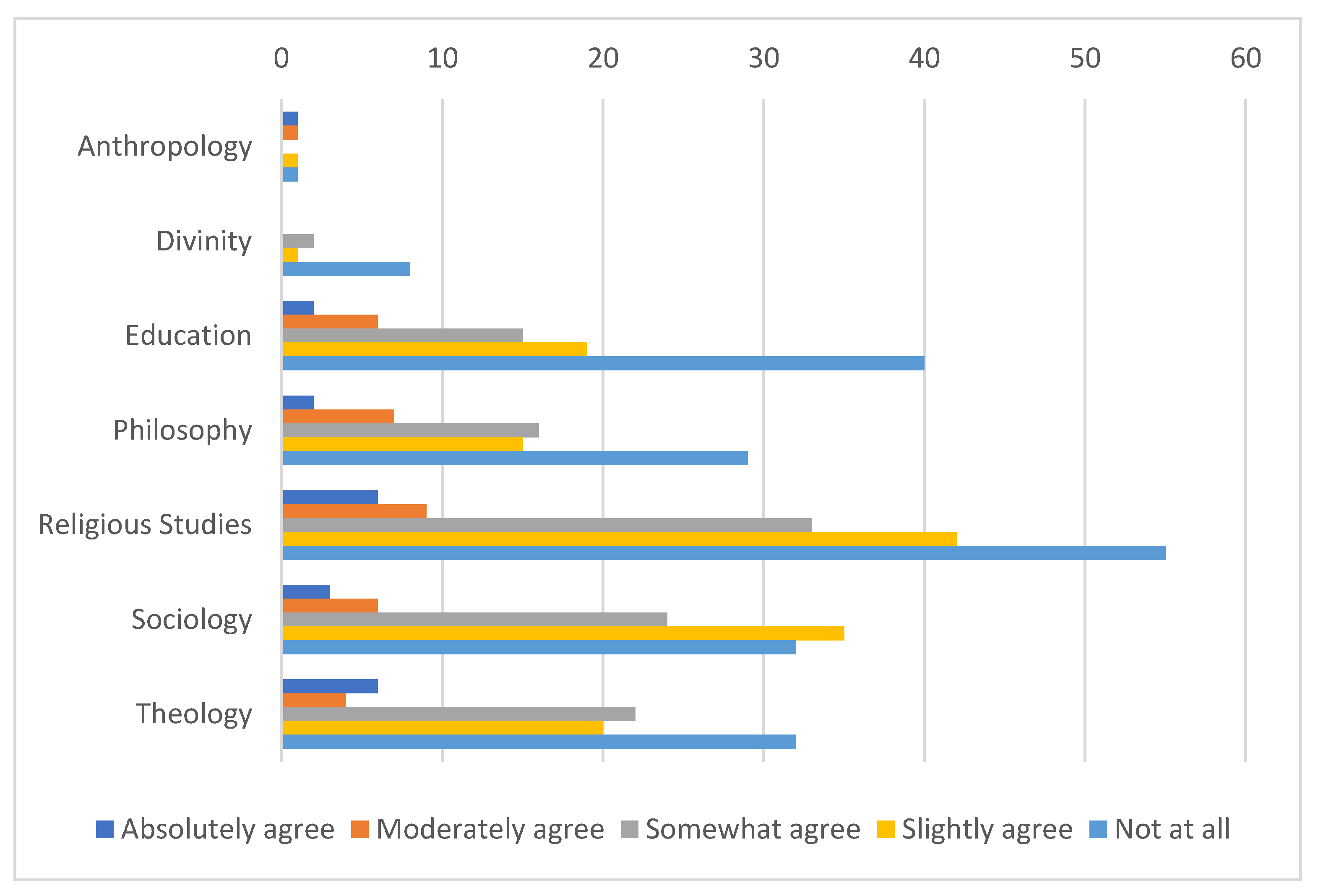

8.6. Do Secondary RE Teachers Think Religion Is Dangerous?

Q23: ‘Religion is dangerous’.

This question was explored in our 2018 paper (Smith et al.), allowing the researchers to explore their hypothesis about an essentialised and possibly sanitised presentaiton of religion in the RE classroom.

Figure 8 shows some variation between England in Scotland, particularly the comparatively large ‘somewhat agree’ and ‘slightly agree’ responses from English teachers compared to those in Scotland.

8.7. Degree Background Q6 Cross-Tabulated with Q23 Religion Is Dangerous

Figure 9 reveals similar patterns across the subject disciplines in terms of their response to the Q23 religion is dangerous, though there are some outliers. RE teachers with Sociology degrees, for example, are the only group for whom the ‘not at all response’ was not the largest.

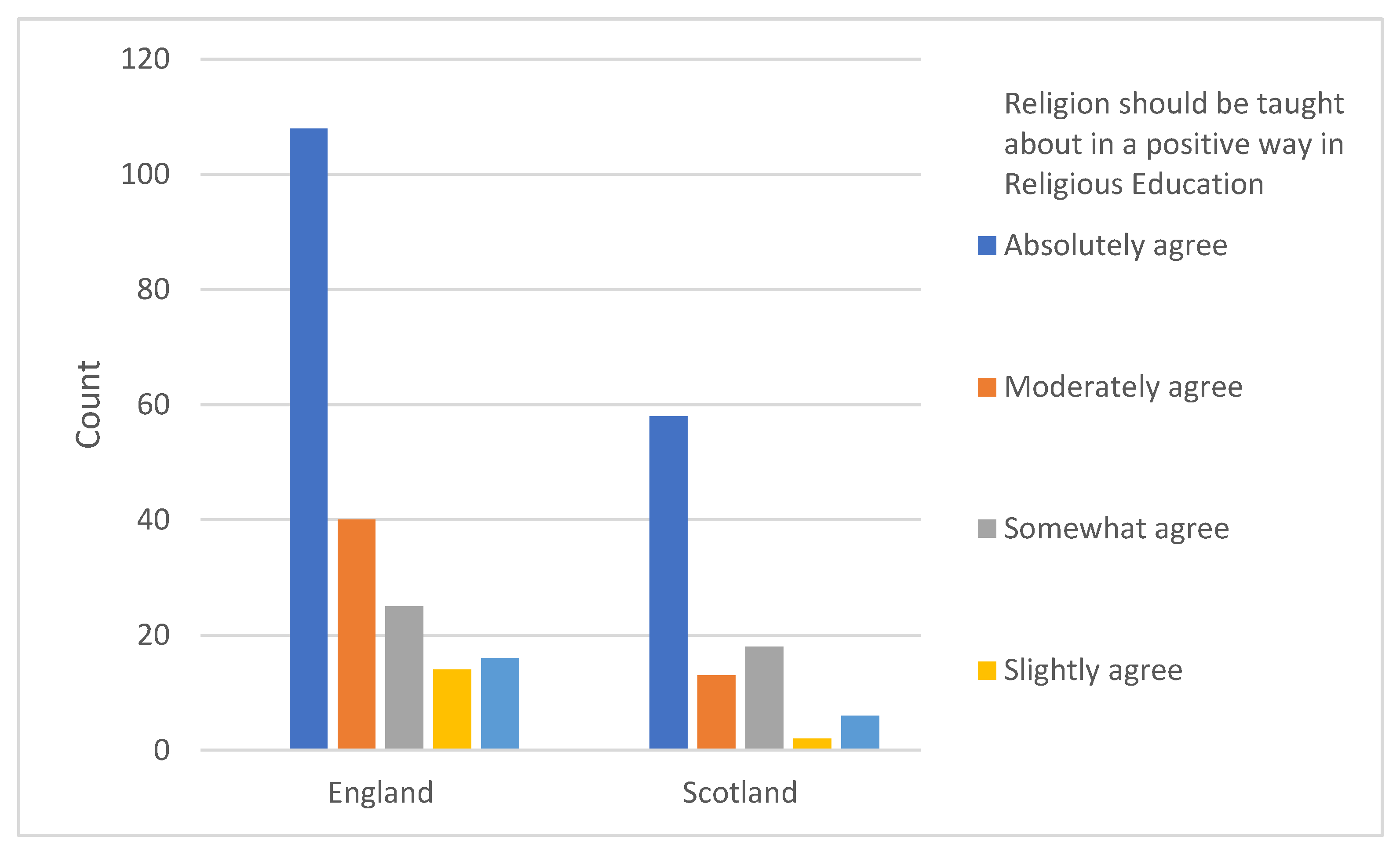

8.8. Do Secondary RE Teachers Think Religion Should Be Taught in a Positive Way?

Q24 ‘Religion should be taught about in a positive way in Religious Education’

Figure 10 shows that the majority of RE teachers in both countries responded ‘Absolutely agree’ when asked if religion should be taught in a positive way.

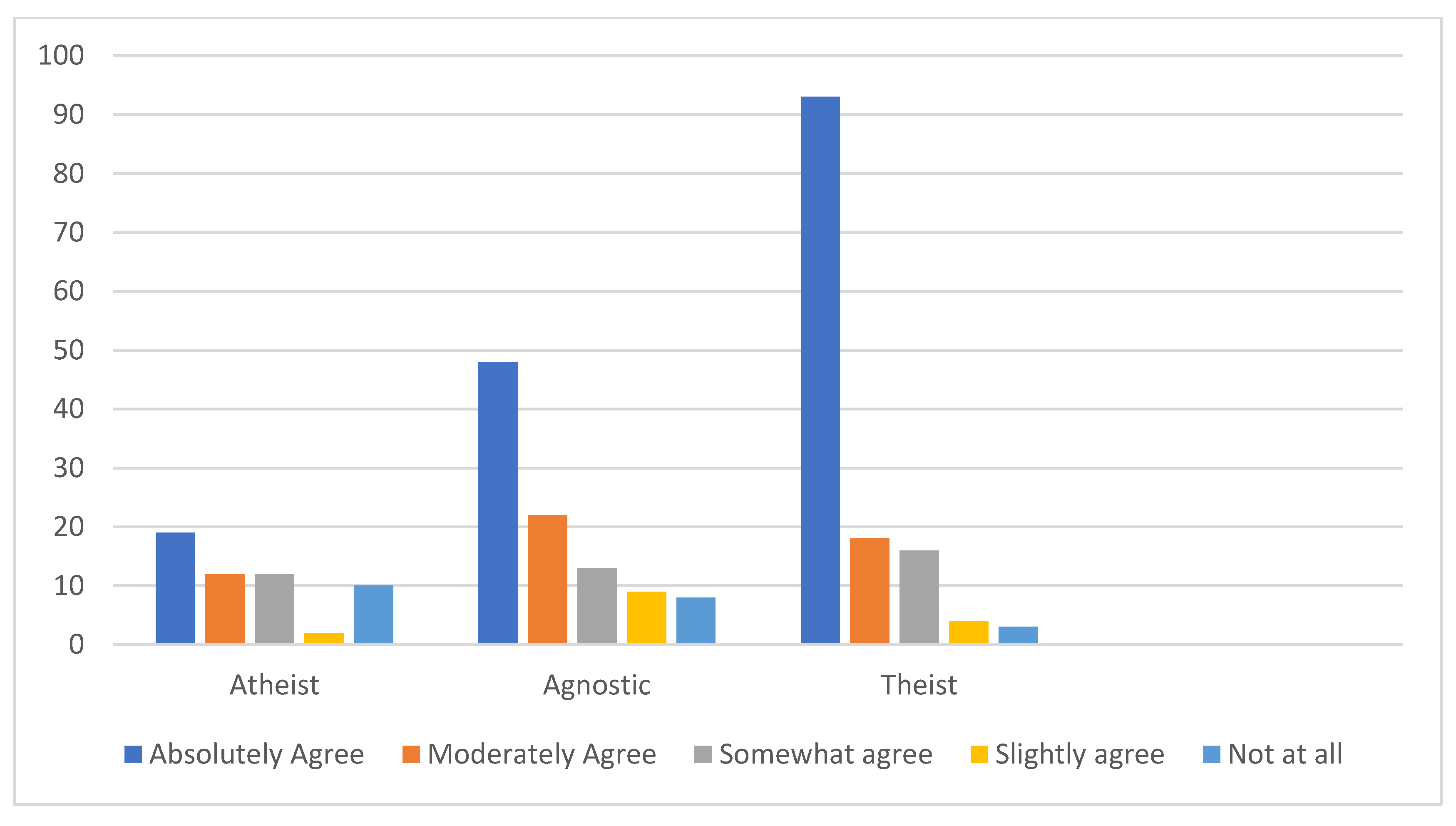

8.9. Belief in God(s) Cross-Tabulated with Views on whether Religion Should Be Taught in a Positive Way in Religious Education

Figure 11 shows a range of beliefs based on (a)theistic positionality regarding how religion should be presented. There is variation between the three groups, though the largest group in all three (albeit markedly so in the theistic and agnostic respondents) was ‘absolutely agree’ when asked if religion should be taught in a positive way. The ‘not at all’ response from atheists was the second smallest category (smallest for the agnostic and theistic respondents).

9. Discussion

The data reveal that RE teachers in England and Scotland come from diverse academic and religious perspectives. RE teachers in both countries have a range of degree backgrounds and outlooks. There are local differences, which can perhaps be explained semantically; for example, the tendency in Scotland to use the Latin ‘Divinity’ where, in England the Greek ‘Theology’ is more prevalent. RE teachers in England have a wide range of degree backgrounds, many of which are loosely or not at all related to the subject they teach. This could relate to the interpretation of Initial Teacher Education providers, or it may be that these teachers have top-up, non-degree, subject relevant qualifications or experience; while there is a greater specificity in Scotland due to the General Teaching Council (Scotland)’s requirements for teaching RE.

In England and Scotland, fewer than 50% of Secondary RE teachers identify as ‘Theist’. The response for ‘Atheist’ was higher in England than in Scotland. When cross-tabulating subject background to belief in God, Philosophy (29.87%), graduates selected ‘Atheist’ the most, while Divinity (64.29%) and Theology (59.65%) graduates opted for ‘Theist’.

One of the most striking findings was that RE teachers are less likely in both England and Scotland to be religious than members of the general population according to 2011 census data. The census data for England show that 25.1% of the population are non-religious, whilst our data revealed that, of our sample, 47.62% (or n = 110) of RE teachers in England have ‘no religion’. In Scotland, where the 2011 census data state that 36.7% of the population have ‘no religion’, our data revealed that, of our sample, 55.65% (or n = 64) have ‘no religion’. It seems that

Hull (

1975) vision of a non-affiliated RE profession is, in large part, realised.

Our data lend support to the position that secularisation, understood as a decline in the power, popularity, prestige, and plausibility of religion, is an uneven process in the UK. In line with census data, our research indicates that Scotland has secularised faster than its southern neighbour. Though our research does not demonstrate the link between rates of secularisation and forms of Christianity, it does support the idea that certain forms of Protestantism have become more vulnerable to declining affiliation. This is perhaps borne out by the Scottish census data which shows there has been no such decline in Scottish Catholic affiliation (though this may also be explicable by migration and the perpetuation of denominational schools in Scotland).

In terms of the sociological perspectives outlined earlier in this paper it seems that the views of Bruce and Brown, discussed in

Section 3 above, about declining affiliation to religion in terms of self-identification are manifest within the RE teaching profession. Furthermore, Davie’s hypothesis that people in the UK and elsewhere ‘believe without belonging’ is not confirmed by the data considered here. Her view that religious identity is mutating away from the congregational milieu while theism is largely retained, is not evident here, where fewer than 50% of RE teachers identified as theists. In both England and Scotland, the largest response, when asked about religious positioning, was non-religious.

A key finding arose in the cross-tabulation with the ‘religion is dangerous’ and ‘religion should be taught in a positive way’ statements. Responses here were mixed; for example, marginally more English teachers responded that religion was ‘not at all’ dangerous than Scottish teachers. While the largest groups of atheist Respondents stated that religion should be taught positively (34.55%), there was a significant difference with the theist response level (69.40%). We have argued elsewhere (

Smith et al. 2018) that there is a tendency, in the face of the pressure for RE to develop social cohesion and foster tolerance, that RE teachers often sanitise and essentialise religions. This pressure may explain why so many, of whatever religious and irreligious persuasion, responded as they did to the ‘religious is dangerous’ and ‘religions should be taught in a positive way’ statements.

Finally, our survey revealed that the pre-service qualifications for RE teachers are varied, and that this variation is more marked in England, perhaps reflecting the multiple routes into the profession therein.

Section 5.3 and

Section 6.3 of this paper, which spelled out the requirements for entry to teaching each of these countries, where these are more prescriptive in Scotland than in England, support this hypothesis.

In England the

Commission on Religious Education (

2018) published its report, recommending that the broadening remit of RE should be reflected in the subject title. The suggested title for RE, Religion and Worldviews, represents a recognition of the need for the title to reflect the inclusion of the study of theistic and non-theistic positions and moral frameworks. Our research revealed that this is also reflected in the degree qualifications of the RE profession where graduates in diverse subjects such as Philosophy, Anthropology and Sociology (all of which can include the study of worldviews) are granted access to the profession.

The aforementioned decline in numbers of graduates of Religious Studies and Theology may also be a consideration here. Could it be that the broadening of pre-service degree qualifications may relate to this decline?

10. Limitations, Conclusions and Implications

There are some limitations to this paper. Responses to the online survey were gathered using RE networks, principally through social media platforms. This precludes certain RE teachers from access to the survey and contributing to the research. Furthermore, respondent were self-selecting and the researchers are blind to the extent to which others did not participate perhaps because they responded negatively to some of the more provocative aspects of the survey (for example, asking RE teachers if religion is dangerous). A further limitation or boundary on the research is that it may not represent many who teach RE, who however are not RE specialists. That is, there may be teachers in schools (as discussed above) who deliver RE with no subject background or initial teacher education RE qualification who did not participate as they may not be involved in the networks used to distribute the survey. This is perhaps to highlight an area for further research about the extent to which non-specialists are involved in RE teaching and issues related to this.

Another aspect of the research that could be considered a limitation is that this is, as far as the authors can establish, the first survey of this kind and scale to be published about the beliefs and positionalities of English and Scottish RE teachers. That is, there is no baseline for comparison. There is therefore a risk of making assumptions about changes in the positionality of RE teachers, for example in assuming that it is surprising that so many self-identify as non-religious, agnostic or atheistic. However, this possible limitation (which admittedly will not be fully addressed until further empirical work is completed) should be contextualized with a reminder that RE was explicitly confessional into the 1970s (see

Section 4 above) in these countries and it remains an area confused with communal worship, rendered suspicious by the perpetuation of the parental right of withdrawal. It may not therefore be an unreasonable assumption to think the RE profession would tend to religiosity/theism, and one that certainly seems to inform communal memory (as evident in the television show mentioned at the outset of this paper).

This research reveals the multiplicity of beliefs and qualifications within the RE profession. As such it points towards further research about the changing nature of RE and possible degree requirements for teaching this area in the secondary school. This paper raises questions about the role and nature of expert subject specific knowledge within RE. Could it be that entry criteria are being broadened to reflect a wider conceptualisation of RE? How does this link to the declining numbers of students studying Religious Studies and Theology towards undergraduate degrees? Should the RE profession be concerned about the future of their discipline? Perhaps if conceptualisations of RE are wedded to a view that religion is the sole object of study then there is, indeed, reason to be fearful.

Most RE teachers in England and Scotland do not believe in God(s); they do not identify as ‘Theist’. Nearly half of RE teachers in England and more than half in Scotland have ‘no religion’. There is a trivial aspect to these findings in that they do not accord with some commonly held presuppositions about the subject and its teachers: the joke mentioned at the outset of this paper about the atheist RE teacher in the 2000s TV show simply does not work at present.

However, we contend that there are more weighty considerations. The subject, since the 1970s, in both England and Scotland, has tried to establish itself as an educational exploration of religious traditions and wisdom traditions. To an extent, this has been a process impeded by, on the one hand, popular views of the subject, including who teaches it; but on the other, certain historical statutes which, despite their origins in a more Christian UK, remain influential. The common conflation of Religious Education and Collective Worship (England)/Religious Observance (Scotland) and the persistence of the parental right of conscientious withdrawal continue to preserve the ideas that RE is confessional and, linked to this, that it is objectionable. The ongoing confusion between RE and acts of worship, and persistence of the right to withdraw may perpetuate and recycle an intergenerational memory that RE is confessional and that RE teachers are concerned to proselytize young people in schools. There is therefore a dissonance between popular conceptions of the RE profession and the realities of who teaches it. Our research shows that the RE profession is broad, being comprised of professionals from multifarious backgrounds. It is our hope that this may lend impetus to the further recognition of the importance of a non-confessional subject which foregrounds the ubiquity of worldviews, providing a brave dialogic space in which young people can sculpt their own.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; methodology, G.N. and D.S.; software, D.S.; validation, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; formal analysis, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; investigation, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; resources, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.N.; writing—review and editing, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; visualization, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; supervision, G.N., D.S. and J.F.-P.; project administration, G.N.; funding acquisition, n/a. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Aberdeen (June 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Cherie, and Graeme Nixon. 2010. The move to faculty middle management structures in Scottish secondary schools: A case study. School Leadership and Management 30: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Robert. 2008. The History of Scottish Education, pre-1980. In Scottish Education, 3rd ed. Edited by Tom Bryce and Walter Humes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Philip. 2006. The Misrepresentation of Religion in Modern British (Religious) Education. British Journal of Educational Studies 54: 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumfield, Vivienne. 2012. Understanding the Wider Context: Meaning and Purpose in Religious Education. British Journal of Religious Education 34: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter, ed. 1999. The Desecralisation of the West. Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Centre and Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., Grace Davie, and Effie Fokas. 2008. Religious America, Secular Europe?: A theme and Variation. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Calum G. 2001. The Death of Christian Britain—Understanding Secularisation. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Calum G. 2010. What was the religious crisis of the 1960s? Journal of Religious History 34: 468–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularisation in the West. Religion & Modernity Series; Oxford: Blackwell’s. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2011. Secularization: In Defense of an Unfashionable Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2013. Post-Secularity and Religion in Britain: An Empirical Assessment. Journal of Contemporary Religion 28: 369–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, Steve. 2017. Secular Beats Spiritual, The Westernization of the Easternization of the West. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Religious Education. 1970. The Fourth R: The Report of the Commission on Religious Education in Schools. London: National Society and Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Religious Education. 2018. Final Report, Religion and Worldviews: The Way Forward. A National Plan for RE. Available online: https://www.commissiononre.org.uk/final-report-religion-and-worldviews-the-way-forward-a-national-plan-for-re/ (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Conroy, James C. 2016. Religious Education and religious literacy–A professional aspiration? British Journal of Religious Education 38: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, Terence. 1997. Teaching Religion: Fifty Years of Religious Education in England and Wales. Exeter: Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 1994. Religion in Britain Since 1945: Believing without Belonging. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2000. Religion in Modern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2002. Europe: The Exceptional Case. London: Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2013. The Sociology of Religion: A Critical Agenda. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, Daniel C. 2007. Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Children, Schools and Families. 2010. Religious Education in English Schools: Non-Statutory Guidance. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/190260/DCSF-00114-2010.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Department for Education. 2012. Religious Education (RE) and Collective Worship in Academies and Free Schools. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/re-and-collective-worship-in-academies-and-free-schools/religious-education-re-and-collective-worship-in-academies-and-free-schools (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Education Scotland. 2019. Religious and Moral Education. Available online: https://education.gov.scot/scottish-education-system/policy-for-scottish-education/policy-drivers/cfe-(building-from-the-statement-appendix-incl-btc1–5)/curriculum-areas/Religious%20and%20moral%20education (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Everington, Judith. 2012. We’re All in this Together, the Kids and Me’: Beginning Teachers’ Use of their Personal Life Knowledge in the RE Classroom. Journal of Beliefs and Values 33: 343–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everington, Judith Ina Avest, Cok Bakker, and Anna Van der Want. 2011. European religious education teachers’ perceptions of and responses to classroom diversity and their relationship to personal and professional biographies. British Journal of Religious Education 33: 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, Leonardo, and Leon Robinson. 2018. Religious and moral education. In Scottish Education. Edited by Tom Bryce, Walter Humes, Donald Gillies and Aileen Kennedy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 490–96. ISBN 9781474437844. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, François. 2017. Religion Is Not What It Used to Be: Consumerism, Neoliberalism, and the Global Reshaping of Religion, London School of Economics Blog. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/religionglobalsociety/2017/10/religion-is-not-what-it-used-to-be-consumerism-neoliberalism-and-the-global-reshaping-of-religion/?fbclid=IwAR1gJ51ZFwoFZeNKXTXy48Mv-qyxLTKLZKlnHXjPAZvLDeZJ21sbfP6QrM4 (accessed on 16 June 2019).

- Grant, Lynne, and Yonah H. Matemba. 2013. Problems of assessment in religious and moral education: The Scottish case. Journal of Beliefs & Values 34: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Brad S. 2017. Rebel in the Ranks; Martin Luther the Reformation, and the Conflicts that Continue to Shape our World. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- General Teaching Council for Scotland. GTCS. 2019. Memorandum on Entry Requirements for Initial Teacher Education Programmes. Available online: http://www.gtcs.org.uk/web/FILES/about-gtcs/guidelines-for-ite-programmes-in-scotland.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- Hand, Michael, and Jo Pearce. 2011. Patriotism in British schools: Teachers’ and students’ perspectives. Educational Studies 37: 405–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelas, Paul L., and Linda Woodhead. 2008. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality. Hoboken: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hella, Elina, and Andrew Wright. 2009. Learning ‘about’ and ‘from’ religion: Phenomenography, the variation theory of learning and religious education in Finland and the UK. British Journal of Religious Education 31: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, Adrian. 2018. Academies and Free Schools in England: A History and Philosophy of the Gove Act. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, John. 1975. School Worship. London: SCM. [Google Scholar]

- Iannelli, Cristina. 2007. Inequalities in entry to higher education: A comparison over time between Scotland and England and Wales. Higher Education Quarterly 61: 306–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Robert, ed. 1982. World Religions in Education: Approaching World Religions. London: John Murray Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 2013. Religious education in England: The story to 2013. Pedagogiek 33: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Robert, and Judith Everington. 2017. Teaching inclusive religious education impartially: An English perspective. British Journal of Religious Education 39: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodzinski, Wolfgang, and Karel Dobbelaere. 1995. Secularization and Church Religiosity. In the Impact of Values. Edited by J. W. Van Deth and E. Scarbrough. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, John. 1560. The First Book of Discipline. Still Waters Revival Books. Available online: http://www.swrb.com/newslett/actualNLs/bod_ch03.htm (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- McKinney, Stephen. J. 2008. Catholic Schools in Scotland: Mapping the Contemporary Debate and Their Continued Existence in the 21st Century, Glasgow Theses. Glasgow: University of Glasgow. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, Nick. 2006. The Experience of Black African Religious Education Teachers Training in England. British Journal of Religious Education 28: 173–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natcen. 2019. British Social Attitudes Survey Press (Religion). Available online: https://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/39293/1_bsa36_religion.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- National Records for Scotland. 2018. Available online: https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/variables-classification/religion-classification (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- NATRE. 2016. An Analysis of the Provision for RE in Primary Schools Autumn Term 2016. Available online: https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Additional%20Documents/NATRE%20Primary%20Survey%202016%20final.docx (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- NATRE. 2017. The State of the Nation: A report on Religious Education Provision Within Secondary Schools in England. Available online: https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Free%20Resources/SOTN%202017%20Report%20web%20version%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Nixon, Graeme. 2008a. From RE to RMPS: The case for the Philosophication of Religious Education in Scotland. Education in the North 16: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2008b. Religious and Moral Education. In Scottish Education: Beyond Devolution, 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 557–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2009. Postmodernity, Secularism and Democratic approaches to Education: The impact on Religious Education in Scotland. An Analysis of the ‘philosophication’ of Scottish Religious Education in Light of Social and Educational Change. Journal of Empirical Theology 22: 162–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2012. The emergence of philosophy in Scottish secondary school Religious Education. Koers- Bulletin for Christian Scholarship 77: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2013a. Religious and Moral Education (Primary). In Scottish Education: Fourth Edition: Referendum, 4th ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 492–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2013b. Religious and Moral Education (Secondary). In Scottish Education: Fourth Edition: Referendum, 4th ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 640–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2013c. Religious Education on the Darkling Plain: The Emergence of Philosophy within Scottish Religious Education, 1st ed. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Graeme. 2018. Conscientious withdrawal from religious education in Scotland: Anachronism or necessary right? British Journal of Religious Education 40: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Stephen. G., and Rob. J.K. Freathy. 2012. Ethnic diversity, Christian hegemony and the emergence of multi-faith religious education in the 1970s. History of Education 41: 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, Lindsay. 2000. Traditions of Scottish Education’, Education: Institutions of Scotland. East Linton: Tuckwell Press in association with the European Ethnological Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Revell, Lynn, and Rosemary Walters. 2010. Christian Student RE Teachers: Professionalism and Objectivity. Canterbury: Canterbury Christchurch University. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, Angela. 1990. Contemporary Educational Policy Making in Scotland. In Curriculum and Assessment in Scotland—A Policy for the 90’s. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scholes, Stephen. C. 2020. Challenges and Opportunities in Religious Education: Re-Considering Practitioners’ Approaches in Scottish Secondary Schools. Religious Education 115: 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schools Council. 1971. Working Paper 36: Religious Education in Secondary Schools. London: Evan/Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Education Department (SED). 1972. (The Millar Report) Moral and Religious Education in Scottish Schools, Report of a Committee Appointed by the Secretary of State for Scotland. Edinburgh: HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Sikes, Pat, and Judith Everington. 2001. Becoming an RE teacher: A life history approach. British Journal of Religious Education 24: 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, Nicola. 1989. Conflict and reconciliation between competing models of religious education: Some reflections on the British scene. British Journal of Religious Education 11: 128–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, David. R., Graeme Nixon, and Jo Pearce. 2018. Bad Religion as False Religion: An Empirical Study of UK Religious Education Teachers’ Essentialist Religious Discourse. Religions 9: 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- The British Academy. 2019. Theology and Religious Studies Provision in UK Higher Education. Available online: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/theology-religious-studies.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2019).

- The Office for National Statistics. 2012. Religion in England and Wales. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/religion/articles/religioninenglandandwales2011/2012–12-11 (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- The Office for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 2007. Toledo Guiding Principles on Teaching about Religion and Belief in Public Schools. Warsaw: Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. [Google Scholar]

- Therborn, Göran. 1995. European Modernity and Beyond. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government. 2021. Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics. Available online: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Van der Want, Anna, Cok Bakker, Ina Ter Avest, and Judith Everington, eds. 2009. Teachers Responding to Diversity in Europe: Researching Biography and Pedagogy. Munster: Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee, Theo. 2012. Inspiration: A Thought Provoking Concept for RE Teachers. British Journal of Religious Education 34: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Andrew L. 1994. The Revival of the Democratic Intellect. Edinburgh: Polygon. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Andrew. 1993. Religious Education in the Secondary School. London: David Fulton. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).