Personal Resources and Spiritual Change among Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Turn to Religion

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationship between Conservation of Resources, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Spiritual Change

1.2. Relationship between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Spiritual Change

1.3. Relationship between Religious Coping Strategies and Spiritual Change

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Conservation of Resources (COR) Evaluation

2.2.2. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) CheckList (PCL-C)

2.2.3. Coping Inventory (MINI-COPE)

2.2.4. Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI)

2.3. Statistical Methods

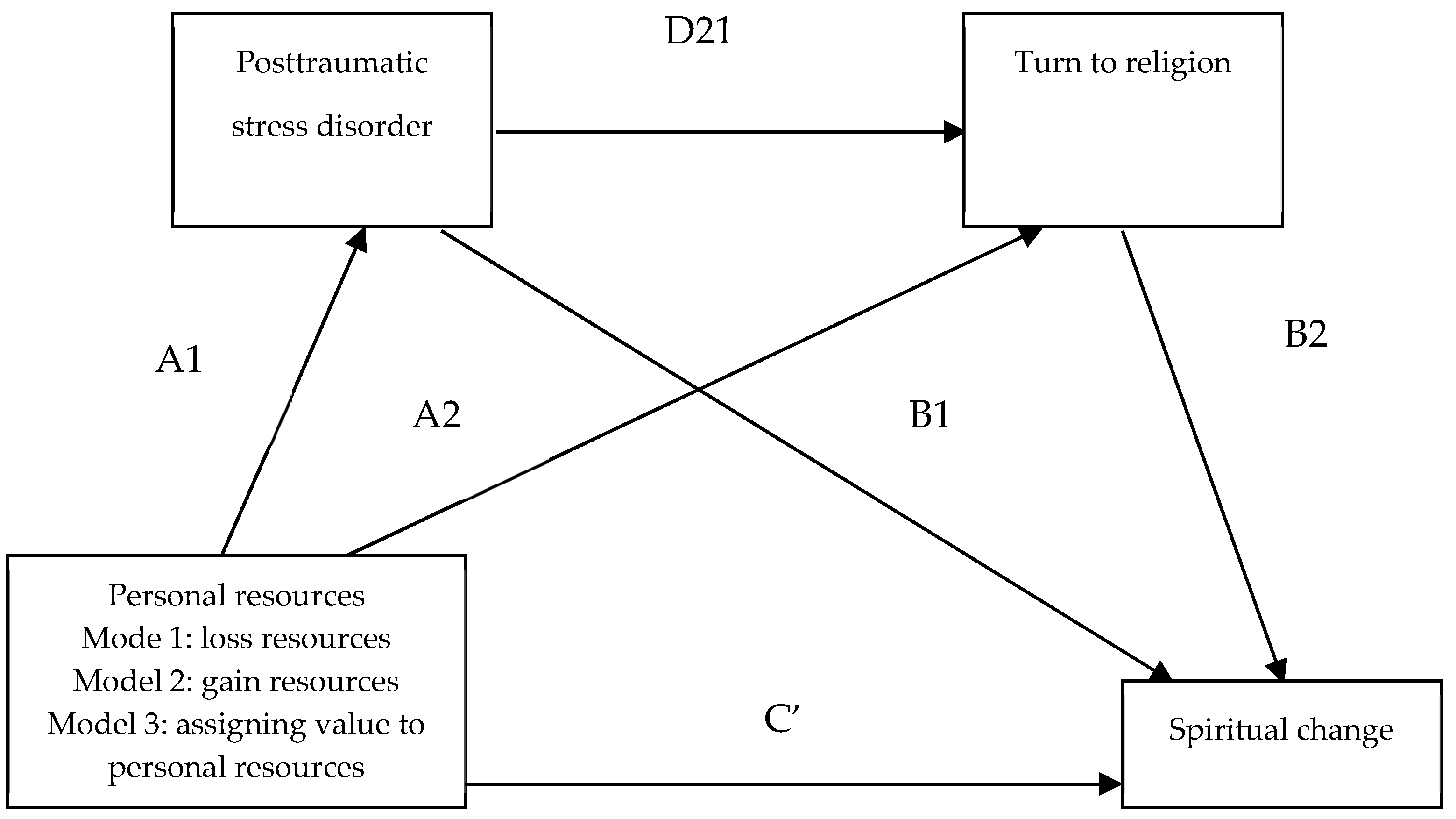

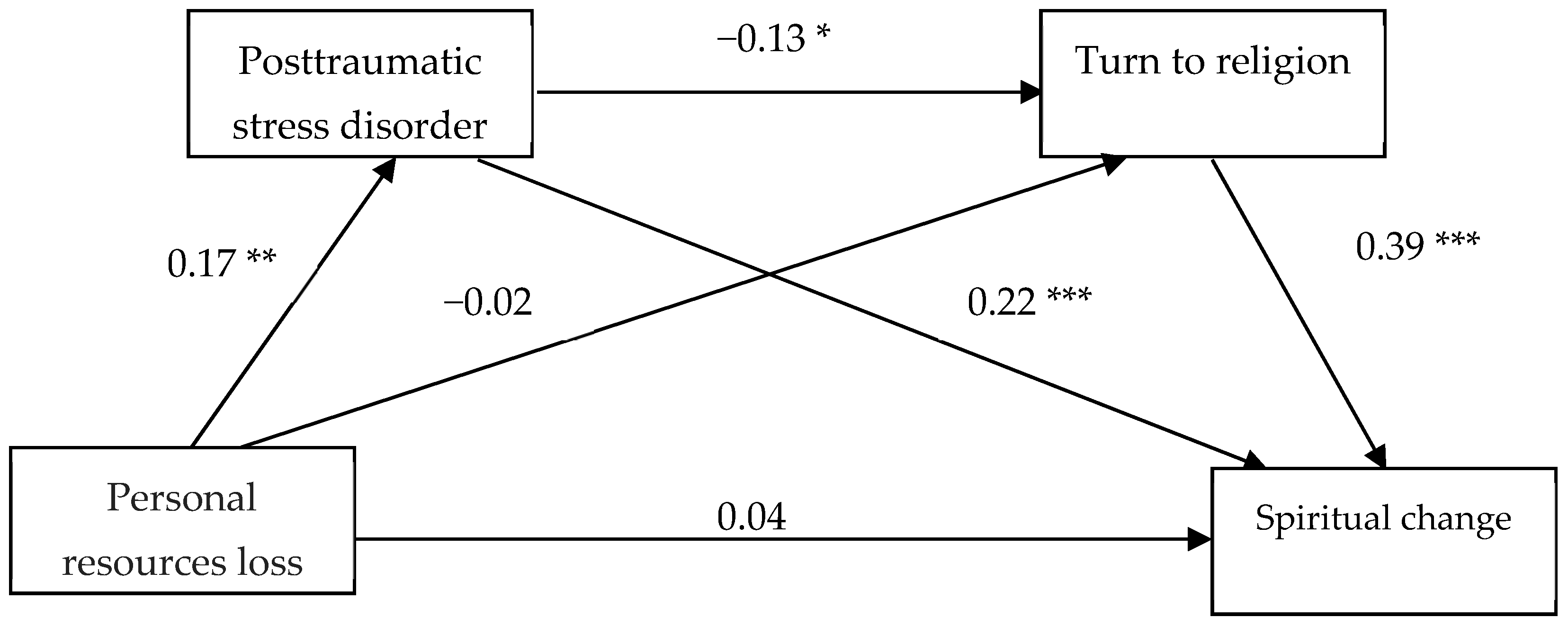

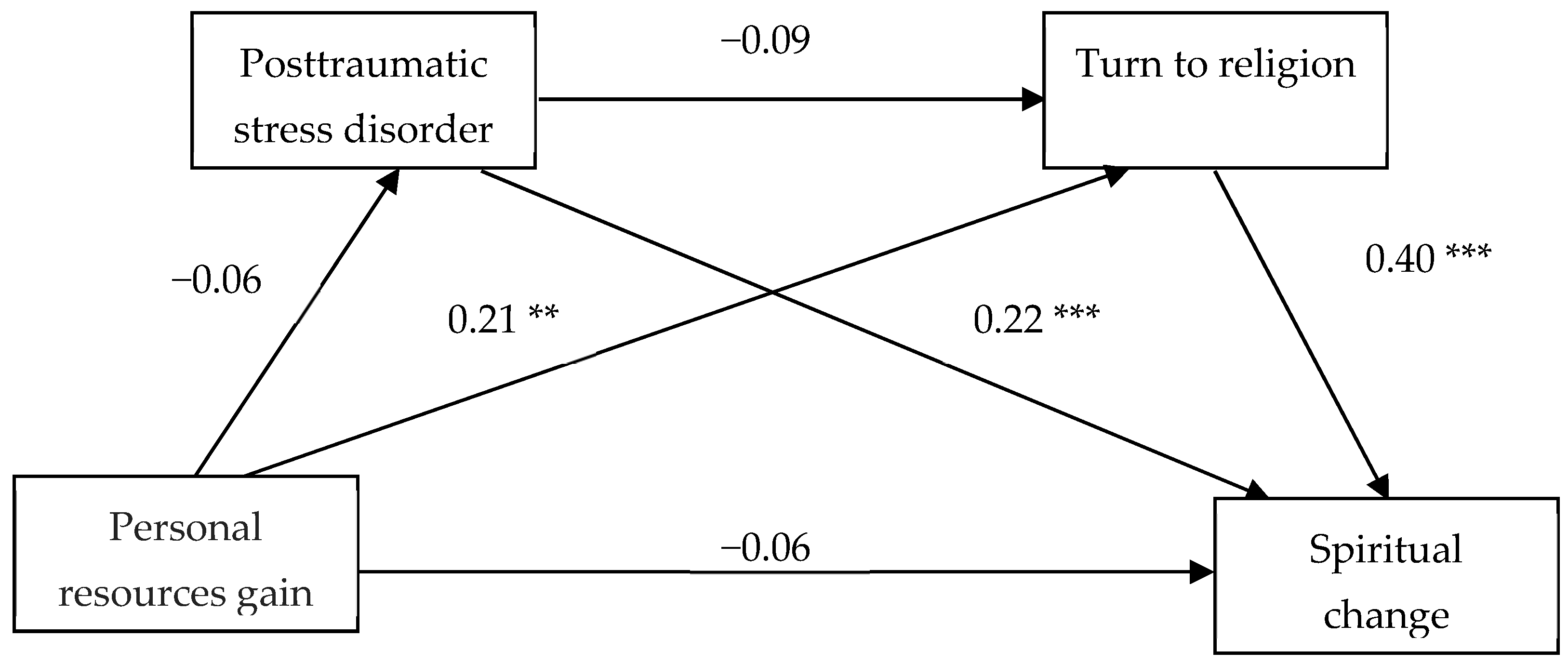

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aghababaei, Naser, Agata Błachnio, and Masoume Aminikhoo. 2018. The Relations of Gratitude to Religiosity, Well-Being, and Personality. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 21: 408–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahles, Joshua J., Amy H. Mezulis, and Melissa R. Hudson. 2016. Religious Coping as a Moderator of the Relationship between Stress and Depressive Symptoms. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., Toni Cascio, Linda K. Santangelo, and Teresa Evans-Campbell. 2005. Hope, Meaning, and Growth Following the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 20: 523–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Gene G., and Erin Vasconcelles. 2005. Religious Coping and Psychological Adjustment to Stress: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 4: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areba, Eunice M., Laura Duckett, Cheryl Robertson, and Kay Savik. 2018. Religious Coping, Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety, and Well-Being Among Somali College Students. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogic, Marija, Anthony Njoku, and Stefan Priebe. 2015. Long-Term Mental Health of War-Refugees: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 15: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Matt, and Blake Victor Kent. 2018. Prayer, Attachment to God, and Changes in Psychological Well-Being in Later Life. Journal of Aging and Health 30: 667–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Peter F. Matthiessen, and Thomas Ostermann. 2005. Engagement of Patients in Religious and Spiritual Practices: Confirmatory Results with the SpREUK-P 1.1 Questionnaire as a Tool of Quality of Life Research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 8: 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shoshi, Mina Westman, and Stevan E. Hobfoll. 2015. The Commerce and Crossover of Resources: Resource Conservation in the Service of Resilience. Stress and Health. Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress 2: 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwaszcz, Joanna, Rafał Bartczuk, and Iwona Niewiadomska. 2019. Structural analysis of resources in those at risk of social marginalization—Hobfoll’s Conservation of Resources Evaluation. Przegląd Psychologiczny 1: 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, Joop. 2004. Public Mental Health and Culture: Disasters as a Challenge to Western Mental Health Care Models, the Self, and PTSD. In Broken Spirits: The Treatment of Asylum Seekers and Refugees with PTSD. Edited by John P. Wilson and Boris Drozdek. New York: Brunner/Routledge Press, pp. 159–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Sharon, Tsachi Ein-Dor, and Zahava Solomon. 2012. Posttraumatic Growth and Posttraumatic Distress: A Longitudinal Study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 1: 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, Kavita M., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2015. Predictors of Growth and Decline Following Spiritual Struggles. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 25: 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowson, Martin, and Maureen Miner. 2015. Interacting Religious Orientations and Personal Well-Being among Australian Church Leaders. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 18: 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Qijuan Fang, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Rebecca A. Steckler. 2013. Hope, Meaning, and Growth Following the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks. Spiritual Struggles and Mental Health: Exploring the Moderating Effects of Religious Identity 23: 214–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, Alan, and Robert Rosenheck. 2004. Trauma, Change in Strength of Religious Faith, and Mental Health Service Use among Veterans Treated for PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 9: 579–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Patricia, Amy Conlon, and Theresa Glaser. 2001. Positive and Negative Life Changes Following Sexual Assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69: 1048–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L., Michele M. Tugade, Christian E. Waugh, and Gregory R. Larkin. 2003. What Good Are Positive Emotions in Crises? A Prospective Study of Resilience and Emotions Following the Terrorist Attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2: 365–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatzer-Levy, Isaac R., and George A. Bonanno. 2014. Optimism and Death: Predicting the Course and Consequences of Depression Trajectories in Response to Heart Attack. Psychological Sciences 12: 2177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galen, Luke William, and James D. Kloet. 2011. Mental well-being in the religious and the non-religious: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 7: 673–89. [Google Scholar]

- García-Alandete, Joaquín, and Gloria Bernabé-Valero. 2013. Religious Orientation and Psychological Well-Being among Spanish Undergraduates. Acción Psicológica 10: 133–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, Jarosław, Katarzyna Waszyńska, and Barbara Zyszczyk. 2013. Czynniki ryzyka rozwoju zespołu stresu pourazowego u żołnierzy uczestniczących w misjach pokojowych. Studia Edukacyjne 26: 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars, Muriel A., and Agnes Van Minnen. 2010. Posttraumatic Growth in Exposure Therapy for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 4: 504–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Brian J., Stevan E. Hobfoll, Patrick A. Palmieri, Daphna Canetti-Nisim, Oren Shapira, Robert J. Johnson, and Sandro Galea. 2008. The Psychological Impact of Impending Forced Settler Disengagement in Gaza: Trauma and Posttraumatic Growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Brian J., George A. Bonanno, Paul A. Bolton, and Judith K. Bass. 2014. A Longitudinal Investigation of Changes to Social Resources Associated with Psychological Distress among Kurdish Torture Survivors Living in Northern Iraq. Journal of Traumatic Stress 27: 446–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, Myleme O., Harold G. Koenig, Judith C. Hays, Anedi G. Eme-Akwari, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2001. The Epidemiology of Religious Coping: A Review of Recent Literature. International Review of Psychiatry 13: 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Nicole M., Brian J. Hall, Eric U. Russ, Daphna Canetti, and Stevan E. Hobfoll. 2012. Reciprocal Relationships between Resource Loss and Psychological Distress Following Exposure to Political Violence: An Empirical Investigation of COR Theory’s Loss Spirals. Anxiety, Stress and Coping 25: 679–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, Vicki S., Kerry A. Reynolds, and Patricia L. Tomich. 2006. A Meta-Analytic Review of Benefit Finding and Growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 5: 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, Devon E., and Laurence J. Kirmayer. 2013. Local Responses to Trauma: SymptoM, Affect, and Healing. Transcultural Psychiatry 50: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2001. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Applied Psychology 3: 337–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2002. Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Review of General Psychology 4: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2010. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Edited by Susan Folkman. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 127–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Daphna Canetti-Nisim, and Robert J. Johnson. 2006a. Exposure to Terrorism, Stress-Related Mental Health Symptoms, and Defensive Coping among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74: 207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Melissa Tracy, and Sandro Galea. 2006b. The Impact of Resource Loss and Traumatic Growth on Probable PTSD and Depression Following Terrorist Attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress 6: 867–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Patricia Watson, Carl C. Bell, Richard A. Bryant, Melissa J. Brymer, Matthew J. Friedman, Merle Friedman, Berthold Gersons, Joop T.V.M de Jong, Christopher Layne, and et al. 2007. Five Essential Elements of Immediate and Mid-Term Mass Trauma Intervention: Empirical Evidence. Psychiatry 70: 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Anthony D. Mancini, Brian J. Hall, Daphna Canetti, and George A. Bonanno. 2011. The Limits of Resilience: Distress Following Chronic Political Violence among Palestinians. Social Science and Medicine 72: 1400–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Robert J. Johnson, Daphna Canetti, Patrick A. Palmieri, Brian J. Hall, Iris Lavi, and Sandro Galea. 2012. Can People Remain Engaged and Vigorous in the Face of Trauma? Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. Psychiatry 75: 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Jonathon Halbesleben, Jean Pierre Neveu, and Mina Westman. 2018. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Allison E. Gaffey, and Linzy M. Wagner. 2020. PTSD and the Influence of Context: The Self as a Social Mirror. Journal of Personality 1: 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Charles W., Carl A. Castro, Stephen C. Messer, Dennis McGurk, Dave I. Cotting, and Robert L. Koffman. 2004. Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Mental Health Problems, and Barriers to Care. New England Journal of Medicine 351: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollifield, Michael, Andrea Gory, Jennifer Siedjak, Linda Nguyen, Lucie Holmgreen, and Stevan Hobfoll. 2016. The Benefit of Conserving and Gaining Resources after Trauma: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 5: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interian, Alejandro, Anna Kline, Malvin Janal, Shirley Glynn, and Miklos Losonczy. 2014. Multiple Deployments and Combat Trauma: Do Homefront Stressors Increase the Risk for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms? Journal of Traumatic Stress 27: 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, Oscar, and Robert Seely. 2015. Russian Full-Spectrum Conflict: An Appraisal after Ukraine. Journal of Slavic Military Studies 28: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Stephen, and P. Alex Linley. 2006. Growth Following Adversity: Theoretical Perspectives and Implications for Clinical Practice. Clinical Psychology Review 26: 1041–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Zygfryd, and Nina Ogińska-Bulik. 2009. Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu i Radzenia Sobie ze Stresem. Warsaw: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty, Krzysztof. 2012. Predicting Social Psychological Well-Being Following Trauma: The Role of Postdisaster Social Support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 4: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, Krzysztof, and Fran H. Norris. 2008. Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21: 274–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Amanda Sonnega, Evelyn Bromet, Michael Hughes, and Christopher B. Nelson. 1995. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52: 1048–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Daniel W., Lynda A. King, Terence M. Keane, David W. Foy, and John A. Fairbank. 1999. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a National Sample of Female and Male Vietnam Veterans: Risk Factors, War-Zone Stressors, and Resilience-Recovery Variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108: 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, and R. David Hayward. 2013. Prayer Beliefs and Change in Life Satisfaction Over Time. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 674–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2014. The Religious Meaning System and Subjective Well-Being. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 36: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, Stephen J., and Tracey A. Ravenson. 2006. Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth: Recovery, resistance, and reconfiguration. In Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth. Edited by Lawrence G. Calhoun and Richard G. Tedeschi. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc., pp. 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Linley, P. Alex, and Stephen Joseph. 2004. Positive Change Following Trauma and Adversity: A Review. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1: 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheux, Annie, and Matthew Price. 2016. The Indirect Effect of Social Support on Post-Trauma Psychopathology via Self-Compassion. Personality and Individual Differences 88: 102–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, J. Curtis, Elizabeth M. Smith, and Rachel H. Fisher. 1997. Perceived Benefit and Mental Health after Three Types of Disaster. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 5: 733–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, Naser, Aemal Akhtar, Jürgen Barth, and Ulrich Schnyder. 2018. Psychiatric Disorders in Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons after Forced Displacement: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, Daisuke, Yutaka Matsuoka, and Yoshiharu Kim. 2010. Posttraumatic Growth, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Resilience of Motor Vehicle Accident Survivors. BioPsychoSocial Medicine 4: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, Virginia E., Sloan C. Alday, and Jeannette R. Ickovits. 1996. Models of life change and posttraumatic growth. In Posttraumatic Growth: Positive Changes in the Aftermath of Crisis. Edited by Richard G. Tedeschi, Crystal L. Park and Lawrence G. Calhoun. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ogińska-Bulik, Nina. 2010. Potraumatyczny rozwój w chorobie nowotworowej—Rola prężności. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne 2: 125–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ogińska-Bulik, Nina. 2016. Negative and positive effects of experienced traumatic events among soldiers participating in military missions—The role of personal resources. Psychiatry 3: 123–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ogińska-Bulik, Nina, and Zygfryd Juczyński. 2010. Posttraumatic growth—Characteristicand measurement. Psychiatry 4: 129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ogińska-Bulik, Nina, and Zygfryd Juczyński. 2012. Consequences of experienced negative life events—Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and posttraumatic growth. Psychiatry 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, Patrick A., Daphna Canetti-Nisim, Sandro Galea, Robert J. Johnson, and Stevan E. Hobfoll. 2008. The Psychological Impact of the Israel-Hezbollah War on Jews and Arabs in Israel: The Impact of Risk and Resilience Factors. Social Science and Medicine 67: 1208–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth Ira, Harold George Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 2000. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2013. Religion and meaning. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 357–78. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L., Lawrence H. Cohen, and Renee L. Murch. 1996. Assessment and Prediction of Stress-Related Growth. Journal of Personality 64: 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzyk, Diana, Iwona Niewiadomska, Stanisław Fel, and Paulina Pietras-Prucnal. 2017. Distribution of resources and substance use among people affected by armed conflict. Psychoprevention Studies 2: 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Ken Kelley. 2011. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods 16: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prucnal, Mateusz, Iwona Niewiadomska, Stanisław Fel, and Joanna Chwaszcz. 2017. Resource distribution and coping strategies among the uniformed services during war. Psychoprevention Studies 2: 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, Carol D., and Burton H. Singer. 2002. Pathways through challenge: Implications for well-being and health. In Pathways to Successful Development: Personality in the Life Course. Edited by Lea Pulkkinen and Avshalom Caspi. London: Cambridge University Press, pp. 302–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Paulo Roberto, José Roberto Frota Gomes Capote, José Renan Miranda Cavalcante Filho, Ticianne Pinto Ferreira, José Nilson Gadelha Dos Santos Filho, and Stênio Da Silva Oliveira. 2017. Religious Coping Methods Predict Depression and Quality of Life among End-Stage Renal Disease Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nephrology 18: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, David N., Andrew J. Preston, Charles F. Kaiser, Vivian E. Olivera, Juan Valdez, and Shannon Schlueter. 2002. Hurricane Georges: A Cross-National Study Examining Preparedness, Resource Loss, and Psychological Distress in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress 15: 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahar, Golan, Gal Noyman, Inbal Schnidel-Allon, and Eva Gilboa-Schechtman. 2013. Do PTSD Symptoms and Trauma-Related Cognitions about the Self Constitute a Vicious Cycle? Evidence for Both Cognitive Vulnerability and Scarring Models. Psychiatry Research 205: 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, Ortal, Yael Caspi, Ehud Klein, Barry D. Berger, and Stevan E. Hobfoll. 2011. Resource Loss and Posttraumatic Responses in Bedouin Members of the Israeli Defense Forces. Journal of Traumatic Stress 24: 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Timothy B., Michael E. McCullough, and Justin Poll. 2003. Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and the Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events. Psychological Bulletin 29: 614–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, Zahava, and Rachel Dekel. 2007. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Growth among Israeli Ex-POWs. Journal of Traumatic Stress 20: 303–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Zahava, and Mario Mikulincer. 2006. Trajectories of PTSD: A 20-Year Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 4: 659–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Catherine H., Kristen M. Abraham, Erin E. Bonar, Christine E. McAuliffe, Wendy R. Fogo, David A. Faigin, Hisham Abu Raiya, and Danielle N. Potokar. 2009. Making Meaning from Personal Loss: Religious, Benefit Finding, and Goal-Oriented Attributions. Journal of Loss and Trauma 14: 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Shelley E., Margaret E. Kemeny, Geoffrey M. Reed, Julienne E. Bower, and Tara L. Gruenewald. 2000. Psychological Resources, Positive Illusions, and Health. American Psychologist 55: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, Richard G. 1999. Violence Transformed: Posttraumatic Growth in Survivors and Their Societies. Aggression and Violent Behavior 3: 319–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 1996. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the Positive Legacy of Trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9: 455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, Richard G., and Lawrence G. Calhoun. 2004. Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Psychological Inquiry 15: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Justin, and Mariapaola Barbato. 2020. Positive Religious Coping and Mental Health among Christians and Muslims in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Religions 11: 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, Sian, Michael Power, Nicola Morant, Isaac Marks, and Tim Dalgleish. 2010. Social Support Moderates Outcome in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Exposure Therapy and (or) Cognitive Restructuring for Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 55: 187–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomich, Patricia L., and Vicki S. Helgeson. 2004. Is Finding Something Good in the Bad Always Good? Benefit Finding among Women with Breast Cancer. Health Psychology 23: 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Christy T., Eric Kuhn, Robyn D. Walser, and Kent D. Drescher. 2012. The Relationship between Religiosity, PTSD, and Depressive Symptoms in Veterans in PTSD Residential Treatment. Journal of Psychology and Theology 4: 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Dawne, Brian Smith, Rani Elwy, James Martin, Mark Schultz, Mari Lynn Drainoni, and Susan Eisen. 2011. Predeployment, Deployment, and Postdeployment Risk Factors for Posttraumatic Stress Symptomatology in Female and Male OEF/OIF Veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 120: 819–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, Brian, and Craig S. Wansink. 2013. Are There Atheists in Foxholes? Combat Intensity and Religious Behavior. Journal of Religion and Health 3: 768–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, Frank W., Brett T. Litz, Debra S. Herman, Jennifer a. Huska, and Terence M. Keane. 1993. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX, USA, 24–27 October 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet, Charlotte vanOyen, Karl A. Phipps, Michelle E. Feldman, and Jean C. Beckham. 2004. Posttraumatic Mental and Physical Health Correlates of Forgiveness and Religious Coping in Military Veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 3: 269–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wośko, Patrycja, Iwona Niewiadomska, and Joanna Chwaszcz. 2017. Distribution of resources and post-traumatic growth in people displaced by military operations. Psychoprevention Studies 2: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata, and Małgorzata M. Puchalska-Wasyl. 2020. Can Religious and Spiritual Struggle Enhance Well-Being? Exploring the Mediating Effects of Internal Dialogues. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 1897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Dominika Ziółkowska, and Jacek Śliwak. 2017. Religious support and religious struggle as predictors of quality of life in Alcoholics Anonymous—Moderation by duration of abstinence. Roczniki Psychologiczne 20: 121–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Anna Tychmanowicz, and Dariusz Krok. 2020. Religious Struggle and PsychologicalWell-Being: The Mediating Role of Religious Support and Meaning Making. Religions 11: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, Tanja, and Andreas Maercker. 2006. Posttraumatic Growth in Clinical Psychology—A Critical Review and Introduction of a Two Component Model. Clinical Psychology Review 5: 626–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiebach, Liza, Jean Rhodes, and Lizabeth Roemer. 2010. Resource Loss, Resource Gain, and Mental Health among Survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23: 751–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources loss [1] | - | |||||

| Resources gain [2] | 0.154 ** | - | ||||

| Assigning value to personal resources [3] | 0.021 | 0.696 *** | - | |||

| Spiritual change [4] | 0.068 | 0.006 | 0.161 ** | - | ||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [5] | 0.184 ** | −0.043 | 0.186 ** | 0.177 ** | - | |

| Turning to religion [6] | −0.035 | 0.214 *** | 0.326 *** | 0.352 *** | −0.107 | - |

| M (SD) | 36.56 (15.20) | 56.06 (16.98) | 66.17 (18.22) | 6.01 (2.48) | 20.51 (13.87) | 2.62 (1.75) |

| Alpha | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.69 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niewiadomska, I.; Jurek, K.; Chwaszcz, J.; Wośko, P.; Korżyńska-Piętas, M. Personal Resources and Spiritual Change among Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Turn to Religion. Religions 2021, 12, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030182

Niewiadomska I, Jurek K, Chwaszcz J, Wośko P, Korżyńska-Piętas M. Personal Resources and Spiritual Change among Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Turn to Religion. Religions. 2021; 12(3):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030182

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiewiadomska, Iwona, Krzysztof Jurek, Joanna Chwaszcz, Patrycja Wośko, and Magdalena Korżyńska-Piętas. 2021. "Personal Resources and Spiritual Change among Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Turn to Religion" Religions 12, no. 3: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030182

APA StyleNiewiadomska, I., Jurek, K., Chwaszcz, J., Wośko, P., & Korżyńska-Piętas, M. (2021). Personal Resources and Spiritual Change among Participants’ Hostilities in Ukraine: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Turn to Religion. Religions, 12(3), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030182