Abstract

The four most important King Kong films (1933, 1976, 2005, and 2017) contain religious sentiments that are related to the numinous and mysterious fear of Nature and death that gives meaning to life, and to the institutionalization of society. In this way, as observed in the films, the Society originated by religion is a construction against Nature and Death. Based on these hypotheses, the objective of this work is to (a) show that the social structure of the tribal society that lives on Skull Island is reinforced by the religious feelings that they profess towards the Kong divinity, and (b) reveal the impact that the observation of the generalized alterity that characterizes the isolated tribal society of the island produces on Western visitors—and therefore, on film viewers. The article concludes that the return to New York, after the trip, brings an unexpected guest: the barbarism that is installed in the heart of civilization; that the existing order is reinforced and the society in crisis is renovated; and that the rationality subject to commercial purposes that characterizes modernity has not been able to escape from the religiosity that nests in the depths of the human soul.

1. Introduction

1.1. Comprehensive Sociology and Sociology of Cinema

To develop this article, I will rely fundamentally on three perspectives of Sociology: the comprehensive one of Max Weber, the symbolic and imaginary of the Sociology of Cinema, and the one of the Sociology of Religion, which are linked to two methods—the philosophical hermeneutic and the visual hermeneutic.

Regarding the three orientations of the sociological discipline, first, I will rely on the Weberian Comprehensive or Interpretative Sociology (Weber 2006, pp. 13, 43–44, 172; González García 1992, p. 37; González García 1998, p. 208), for which the social world and the relationships it generates are full of meaning. This is the data with which the sociologist works and which allows him, through the concept of “correspondence in meaning” or “elective affinities”, to find the common links of the different cognitive, aesthetic, economic, political social, and religious dimensions that modernity has fragmented and, in this way, recompose the meaning—the American “worldview” (Muñoz 2001, p. 23). More specifically, I will try to find the general correspondences between the King Kong films and the religiosity of contemporary American society.

Second, the approach to King Kong comes from the Sociology of Cinema, which defends the value of the seventh art as an analytical prism of society and highlights its active symbolization of reality (Francescutti 2012, p. 225). In addition, it takes into account that the cinema constitutes a tool of social analysis that contributes substantially to the construction of social reality (De Miguel Rodríguez and de León 1998, pp. 84–86). Finally, the Sociology of Cinema is linked to the concept of “social imaginary”, as described by E. Morin, in Cinema and Imaginary Man, or Siegfried Kracauer, in From Caligari to Hitler: A psychological history of German cinema. For E. Morin (2011, p. 23 ff), cinema is an objective, subjective, rational–affective, and individual–collective system, which devalues practical reality and increases affective reality—something that it does when carrying out a projective identification, that is, an excitement of the identification with the similar and with the stranger, which differentiates cinema from real life. Furthermore, through photogenicity, a complex quality of shadow, reflection, and double, the cinematographer achieves the dialectical unity of the real and the unreal. It constitutes, in effect, a complex of reality and fiction, a mixed state that rides on waking and sleeping. In this state, it is aesthetics that manage to unify both and what differentiates the cinema from both one and the other. However, it is necessary to bear in mind, according to Morin, that fiction is not reality and that its fictional reality is imaginary. Thus, the cinema transfers the image to the imaginary: “We enter the realm of the imaginary when aspirations, desires -and their negative, the fears-, carry and shape the image to order, according to their logic, dreams, literatures, myths, beliefs, religions, that is, all fictions”. Therefore, the images manifest a latent message, which is that of wishes and fears.

Meanwhile, Siegfried Kracauer (2015, pp. 13–14) defends that the film of a nation reflects its mentality in a more direct way than other artistic media. Specifically, he believes that the US public absorbs what Hollywood wants them to receive, but, in the long run, their wishes determine the nature of American films. Now, more than explicit creeds, what films reflect are psychological tendencies, the deep religious layers of the collective mentality—the collective imaginary, I prefer to call it—that, more or less, run below the conscious dimension.

1.2. The Fear of Nature and Death and Giving Meaning to Life Are at the Origin of Religion

Two aspects are of particular interest to me in this article. First, it is originated by the numinous and mysterious fear of a great, terrible, and hostile Nature and by the awareness that this Nature is inexorably linked with the implacable death that scourges living beings: humans die, precisely, because they are Nature and, therefore, they are religious. But, paradoxically, religion tries, at the same time, to escape from the absurdity that constitutes death, by helping it to become the fundamental hermeneutic principle of human existence, the metaphor of life, and consequently, the one that increases its sense.

“If we were not afraid of death, I do not think the idea of immortality would have been born. Fear is the basis of religious dogma, as of so many things in human life. The fear of human beings, individually or collectively, largely dominates our social life, but the fear of nature is what has given rise to religion.”.(Bertrand Russell 2004, p. 325)

As shown in the quote from the philosopher Russell, fear of Nature, and the death that goes with it, is what has given rise to religion. The “numinous”—the fundamental element of the religious experience and that defines the singular state of the spirit that is aware of the mysterious, terrible, and sacred that inspires fear—appears historically through spells, advice, and myths, in the worship of horrible or wonderful natural objects, which before were nothing more than mere natural images generated by the “primitive” imaginary of “naive” historical times. But the numinous also springs from the cult of the dead (Otto 1996, p. 155). In fact, the horror of death is a universal constant (Morin 1994, pp. 25–30), since, as Feuerbach (2006, p. 155) pointed out, “Everything that lives (everything that is natural, I would add) wants to be preserved, he wants to live and not die”. Indeed, “death was the first mystery, it put man on the path of others and raised his thought from the visible and the invisible, from the temporal to the eternal and from the human to the divine” (De Coulanges 1986, p. 39). This cult constitutes, therefore, the principle of religious sentiment and the idea of the supernatural.

But in the face of religious reality, which calls into question the world of daily life (Bellah 2017, p. 39), the supernatural represents a denial of the natural (Otto 1996, pp. 6–7, 154–56). That supernaturality to which De Coulanges and Otto refer is expressed through direct or indirect means. The terrible and hideous aspect of the “primitive” images or descriptions of the gods, which today seem so repulsive, can still awaken in the “savages” and “naive” human beings the true feeling of a true religious dread. This, then, is a feeling that fuses “dreadful terribleness” and “utmost holiness”. Furthermore, in Western art, the numinous is also externalized through two direct methods of representation, which are darkness (to be perceptible, it has to be contrasted) and silence. Alongside both, art also employs, as an indirect form of the numinous, the sublime (Otto 1996, pp. 88–96; Caro Baroja 1978, p. 107).

Similarly, the historian Ariés (1987, p. 2) explains the germ of the religious in the association of the fight against the fear of nature and death, since one of the most powerful psychological elements of what he calls “the tamed death” would be the defense of society against wild nature. In this way, the reactualization of mortality constitutes a particular case of the global strategy of the human being against Nature, made up of prohibitions, concessions, and atavistic fears.

This is what happens in Christianity, where the “Kingdom of God” is opposed to the natural (Otto 1996, p. 100) and God to mortal human beings: “Here I dare to speak to you, I, I who am dust and ashes” (Genesis, I, 18, 27), Abraham tells Yahweh, in relation to the fate of the sodomites, referring to both elements, significantly, nature and death. In addition, Adam and Eve fall and are expelled from Paradise, from Nature, which has lost its divine aura (Frye 1988, p. 93) and is mythologically defamed through the curse of the ground, adamah (Adam) in Hebrew (Cencillo 1970, pp. 65, 123, 230). It can be said, therefore, that the entire history of the Old Testament has an unnatural accent, insofar as it consists of the confrontation of Yahweh with the cults of Nature, which, in the end, supposes the attempt to abolish it. And it is that where Christians are scandalized, simultaneously, by the fact of dying and by the limits of nature, limits or restrictions that can only be solved by the force of miraculous action (Feuerbach 2006, p. 158; Weber 2017, pp. 63–70).

As will be seen in this article, the fantastic and, particularly, King Kong, like religion, fulfills the function of expressing a revolt or resistance against death (Durand 1992, pp. 465, 468). Not surprisingly, the fear of her and Nature, as well as the characters of the numinous, especially the “frightful terribleness”, the “highest holiness”, the “darkness”, and the “sublime” are present in the god Kong, in the Island of the Skull, and in the religiosity of the tribe that lives there.

But at the same time that religions are determined by fear of Nature and mortality, they try to print a sense of life and death, to move the feeling of absurdity away from the mind of the human being (De Quinto 1962, p. 60). In fact, the world of the dead is presented as a reflection, as a more or less direct or mediated, disguised, and even phantasmagorical expression of the society of the living (Vernant 2001, p. 102). Sure, death constitutes “an image”, a “metaphor” of life (Morin 1994, p. 24). This means that the two are inseparably associated (Buxton 2000, p. 73) and that death “perceived as a discontinuity, is not the one that steals its meaning from life, but the one that makes its greater intensity possible” (Carse 1987, p. 25).

This is appreciated in archaic experiences, for which every death announces a birth, while the cycle of human life is part of the natural cycles of death–rebirth. This is so because it is in nature where the archaic mentality recognizes that all death is followed by a new life, as happens with the sacrifice that constitutes the systematic and universal magical exploitation of the fertilizing form of death (Morin 1994, pp. 115–29).

The myths, which are intimately connected in all the religions of antiquity with the cult (Jensen and Gerhart 1966, p. 54), express that the human being tries to understand the present reality in order to control or predict that of the future, something that he achieves by limiting the objective world, since what interests him is stability, order, and to conjure up the fear that generates chaos. Hence, the structure of the myths is based on repetition, on the return to the same thing that offers certainty, which pursues order in the face of chaos and establishing, for this purpose, a time of eternal return or cyclical time as opposed to the indeterminate linear time (Blumenberg and Rubies 2004, pp. 57–62, 82), which represents death.

Along with this, all primitive peoples have rooted in their culture the belief in the afterlife (Sayés 2006, p. 17), in the same way as the great civilizations of the past have offered a variety of answers to the problem of the social integration of death (Vernant 2001, p. 104) and its influence on way of life. For example, this is what has happened in the religions of “redemption”, including Christianity, as Max Weber calls them, in which the presuppositions of rebirth are very different depending on the path of redemption and, which is closely related, the psychological quality of the salvation sought. Therefore, all eschatologies, the set of religious beliefs about the “ultimate realities” of this world, naturally tend to become hope in the hereafter (Sayés 2006, p. 7; Weber 2017, pp. 208–10); Christianity does the same (Caro Baroja 1978, pp. 131, 141; Rogues 1995, p. 87; Feuerbach 2006, p. 192; Sayés 2006, p. 23).

In modern existentialism, death is also inexorably linked to life, while mortality constitutes, according to Heidegger, the fundamental hermeneutical principle of human existence. This means that death belongs to the fundamental structure of the human being as something constantly present, since as soon as it begins to exist, it is “thrown” into this ever-present possibility of dying. It is precisely in death where the human being conquers the totality of life, the authentic existence (Heidegger 1963, pp. 233, 274–75; Pienda 2001, p. 101); it is where “being is freedom towards death” (Carse 1987, p. 436).

1.3. Religion Is Society

The second aspect of religiosity that interests me here is more strictly sociological and refers to religion as the generator of society and its social structure, its ability to establish the unique social identity of a group, by shaping it as a “generalized otherness”, and creates homological relationships between natural and social conditions. Therefore, it can be inferred that the Society instituted by religion is a construction against Nature and the Death that it represents.

Certainly, in traditional peoples, religion is an instituting principle of society (Héran 1987, p. 68; Rappaport 2001, p. 9). For De Coulanges (1986, p. 27), “from religion all institutions, as well as all the private law of the ancients, formed from it their principles, their rules, their uses and their magistracies”. Hence, the sociology of religion of Émile Durkheim, disciple of De Coulanges, seeks to understand the social fact and reveal the logic behind it. Thus, religation would be an appropriate way to understand the social bond, and the aim would be to capture the forms of social aggregation from an imaginary lived in common (Maffesoli 2004, pp. 160–61).

In fact, religion performs two fundamental functions: it constructs the first discourse and creates a universe of values and meanings that provide the identity, the cultural reproduction, and the nomos, the normative integration, of the group. Consequently, religion becomes the first discourse of the social and the first structuring center of society that, in this way, produces itself as the “generalized otherness”. Now, this constitutive structure of the social is made up of knowledge, the mytho-rite, which is an “archetypal mythical structure”, requiring a performative activity, that is, a collective ritual practice in which the meaning of the myth is dramatized, and the solidarity of the group is regenerated, and which gives a “form” to the real, which becomes the sacred (Eliade 1952, p. 22).

All this implies that the divine constitutes a set of relationships, a society (Maffesoli 1985, p. 57) and, therefore, that religion is fundamentally social—collective (Nilsson 1969, p. 205). In fact, all institutions start from it (De Coulanges 1986, p. 27) insofar as the activities and interrelations of the gods are modeled on the customs and institutions of society (Buxton 2000, p. 143). At the same time, the mythical cosmovision and the modes of representation used by religion serve to establish homological relationships between natural and social conditions (Beriain 1998, p. 127) and, more specifically, between the island, King Kong, and human beings constituted in the community.

In short, religion as a whole represents a social, practical, and everyday issue, which explains why social and religious history are practically inseparable (Parker 1988, pp. 299–300).

It can be gathered, then, that the Society instituted by religion supposes a construction against Nature and the Death that it represents. Finally, the practices, myths, rituals, and sacrifices that religion establishes become a particularly useful instrument to control the uncertainty of time and, consequently, to exorcise the crises and fears that they generate, as well as to renew the society.

1.4. Philosophical Hermeneutics, the Hermeneutics of the Image

The three sociological perspectives mentioned are complemented by two methodologies. The first is the “heuristic or interpretive method” from hermeneutics, a very useful science for comprehensive sociology insofar as its central problem is interpretation (Ricoeur 2008, p. 39), so that it is precisely in interpreting where the possibility of giving meaning to the world is found (García 2012, p. 38). Moreover, what is interpreted with social hermeneutics are the things themselves, a text (Lince Campillo 2009, p. 19 ff)—the filmic images, I would add—but seen in their context (Beltrán Villalba 2016, pp. 3–4). It is, more precisely, about finding the deep keys of the texts and images, that is, to reveal their inner religious sense from the outer ideological verbiage or discourse (Grondin 2014, pp. 10–11, 43–107).

As for the Hermeneutics of the Image (Boehm 1978, pp. 444–71), it is very useful for the knowledge of social phenomena to the extent that the aesthetic and social facts form, like the social and religious, an inseparable totality (Fernández Galán and García Ramírez 2012, p. 51) and while the text image is inseparable from its cultural connotations (Amador Bech 1995, p. 10). Interpreting the image implies recognizing its discursive structure, not only apparent or superficial, but also deep (Mitchell 2009, p. 23). Hence, the work of hermeneutics consists of searching in the text itself, in addition to the inner dynamics that make up the image, its ability to project itself outside of itself and generate a world that precisely becomes the objective of the text (Ricoeur 2001, p. 34). On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that iconology, the hegemonic mode of representation in the West of which photography and cinema are part, is an ideological construction considered real and an essential tool of symbolic analysis, with a neighboring discourse (Panofsky 1972, p. 15; Panofsky 2010, p. 11).

In sum, the films express, in addition to their specific problems, an ideology, understood as a system of ideas, values, and precepts that organize or legitimize the actions of individuals or groups (Van Dijk 1998, pp. 16–19). In this sense, iconological analysis of the four versions of King Kong will allow us to find the religious meaning they hide, based on the images themselves, their context, and the director’s intention.

1.5. Goals

Starting from all these theoretical and methodological bases, this work has three fundamental objectives. First, to demonstrate that, in the saga dedicated to the mythical character King Kong, in his four main films—1933, 1976, 2005, and 2017—the presence of the unfathomable mystery of Nature, of the fear of death that lies at its base, and of the organization of the meaning of social life that this entails is consubstantial to him. Specifically, it is a question of checking whether the nature of Skull Island, its mountains, caves, forests, waters, and animals, and its god King Kong are clothed in mystery and whether they produce fear.

Second, to confirm that the social structure of the tribal society living on Skull Island is reinforced by the religious feelings they profess towards their divinity Kong. In this sense, I will try to reveal if this society is or not hierarchical and monotheistic, closed and autarkic or open, matriarchal or patriarchal, hunter and warrior or farmer, and tribal or fraternal.

Thirdly and finally, to reveal the impact on Western visitors—and therefore, on the film viewers—of the observation of the widespread otherness that characterizes the isolated tribal society of Skull Island. In particular, it is a question of finding out what the return to New York represents, whether or not a reinforcement or questioning of the existing order, and whether or not the commercially driven rationality that characterizes modern civilization has been able to escape from the religiosity that nests in the depths of the human soul.

2. Crisis and Religiosity in Contemporary North America: The Context of King Kong

As for the rest of horror films (Gubern 1979, p. 11), the crisis situation contextualizes the four most important and successful North American films that narrate the myth of King Kong. Certainly, there are two other film versions, one Japanese that is not of interest here and the other, with little public and critical success and, therefore, less significant and representative of the American imaginary1. The first version, from 1933, the one that creates the myth, is directed by Merien C. Cooper and Ernest B. Shoedsack; the second, from 1976, by John Guillermin; the third, from 2005, by Peter Jackson; and the fourth, from 2017, by Jordan Vogt-Roberts.

Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere (Roche Cárcel 2017), different crises sustain these four adaptations: that of the 1929 crash, the first; that of oil in 1973, the second; the attack on the Twin Towers of 11 September 2001, the third; and the last one, a military crisis produced, above all, in 1973 and, more recently, with the Gulf Wars, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Thus, in the first case, its content is related to the economic crisis, to ecology in the second, to risk and security in the third, and to military insecurity in the fourth. In any case, it is very significant that all of them were produced only a few years after each of the respective crises.

The crisis of 1929, which shook and trembled this country and the entire Western world between 1929 and 1933, represented, above all, a failure of the economic system, but also a stage of transition from a series of institutions and social forms to a different one—hence, the monetary or financial motivations joined the weaknesses of the international system. The great world economic crisis of 1929 broke a phase of two centuries of long-term growth (Ladurie 1979, p. 60) and led to a deep depression of agriculture and industrial production that brought with it massive unemployment (Kindleberger 1985, pp. 95–125).

The 1933 version of King Kong is deeply rooted in the economic crisis (Gubern 1974, p. 20; Latorre 1982, p. 6; Carroll 1984, p. 215). In fact, it is clearly manifested in the first minutes, then censored, in which images of the effects of the depression in the most marginal neighborhoods of the city of skyscrapers appear, which are of a “crude realism” and a “almost documentary” aspect (Gubern 1974, p. 54).

On the other hand, the 1973 oil crisis brought the world into an economic recession, leaving behind the “golden age” of the planet that was the second post world war (Hobsbawm 2001, p. 29 ff) and establishing itself in the “Age of Uncertainty”, an economy that loses all its security (Galbraith 1984, pp. 137 and 209), opulence (Slater 1973, p. 107), or abundance (Nisbet 1981, p. 166; Galbraith 1985, p. 27 ff). It is the consequence of the interaction of three phenomena: the deceleration of economic growth, the increase in public indebtedness, and business financing (Beinstein 2005; Beinstein 2008, pp. 3–5; Borón 2009, p. 34).

It is no coincidence that, in the 1976 version, the ship that will lead the protagonists to the mysterious new world is precisely the dark Petrox Explorer, a very justified name to express that the fear of the time is found in the oil crisis.

11 September 2001 led to a new world order—in fact, the attack showed the weaknesses of the great superpower, since its total hegemony came into question, breaking the stage of the bipolar structure that emerged from the Cold War and announcing a new stage, more determined by multilateralism and multipolarity. However, this “new” order did not lead to stability since the new actors did not assume a stabilizing role or did not achieve the appropriate international alliances to stabilize the system. The result has been that the United States of America seeks, time after time, to position itself again as the world leader, which has made globalization difficult, since, at the same time it has integrated itself into the global economy, it has accelerated inequalities and has led the system, since then, to become multipolar and unbalanced (Maldonado et al. 2009, pp. 130, 152–53).

The 2005 adaptation was produced a few years after the attack on the Twin Towers. In this sense, it is pertinent to point out that its destruction was advanced in great detail by Hollywood, on various occasions (Ordóñez 2006, p. 99). For example, in the 1976 adaptation, in the final battle between the gorilla and airplanes or helicopters, some pieces of them, burning, brushed or dangerously hit the walls of skyscrapers in anticipation of what would ultimately happen in 2001.

After the Second World War, the American military strategy was dedicated to the conquest of an extensive Eurasian territory distributed from the Balkans to Afghanistan. Significantly, in the center of this strip are the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea Basin, which contain around 70% of the planet’s oil reserves. After the end of the Cold War, the United States filled this space with military bases and even occupied some of its countries with not only energy objectives, but also the consolidation and reinsurance of the dominance of the international financial system (Beinstein 2008, p. 11).

However, due to mistakes being made, these military objectives, in general, failed, perhaps due, as Beinstein (2008, pp. 10–14) points out, to the fact that its operational gigantism ultimately prevented it from capturing the “little world” of the reality it seeks to subdue. Consequently, North America has entered a deep “military crisis”, of its Military–Industrial Complex, which has also led to the general sensation of crisis in the country.

In this context, the 2017 version takes place, which begins precisely with a hand-to-hand combat between a North American and Japanese aviator who have fallen on Skull Island, thus recalling the conflict of World War II. In addition, the Athenea ship leaves the port of Bangkok, the headquarters of the US armed forces deployed in the Vietnam War, and heads to the island full of soldiers, bombs, and weapons, to find a “monster”. The military presence is more than obvious and the large animals that they must face are but a reflection of the fears of a nation that has been militarily humiliated, not only in Vietnam, but also by small countries such as Afghanistan or Syria.

On the other hand, the film, heir to the pacifist movement that, in 1973, fought against the Vietnam War and the New Age religious movements, collects its main postulates. In fact, at the beginning of it can be seen a demonstration against the war and, as it progresses, the pacifist ideas of the surviving American soldier reconciled with his enemy, and the appeals for help to Kong gain more importance.

As has been shown, the contemporary crisis in the Western world is not purely financial, but a crisis of civilization, since it constitutes an integral or multidimensional historical process (Borón 2009, p. 33) of long duration, produced by internal–external tendencies that have ended in the decline of American society and of a substantial part of the rest of the world (Beinstein 2008, p. 10).

In sum, the anxiety and concern caused by the generalized state of crisis has, as a consequence, the unpleasant and pernicious feelings of uncertainty and risk (Roche Cárcel 2012, p. 148 ff) and the increase in religious sentiment. It seems reasonable to think that successive North American crises have helped to further delegitimize the purpose-bound rationality of the capitalist system and to increase religious sentiments, which had never disappeared from American society.

Certainly, religiosity has persisted, particularly in the United States of America. There are very many people with beliefs, more than 70 million, between Protestants and Catholics, in addition to independent churches and Jews (Díez de Velasco 1995, pp. 495, 524). But also, in a very secularized way, the religious enthusiasm and eschatological expectations that inspired their ancestors are detected. This is because both the first settlers and the last European immigrants who traveled to America did so with the idea of finding the land in which to be reborn, that is, to start a new life, since it was believed that the time had come to renew the Christian world and that this rebirth constituted a return to earthly paradise or, at the very least, a new beginning of sacred history. In fact, the literature of the period—sermons, memoirs, and correspondences—allude to paradise and eschatology. In any case, this was the result of a Protestant Reformation seeking an earthly paradise in which the reform of the Church could be perfected. And, indeed, the nostalgia for paradise and the desire for novelty that fascinates Americans today seem to respond to those religious motivations that lead them to wait for a rebirth, a new life (Eliade 1999, pp. 124–34).

In recent years, syncretic and eclectic religious groups have been born, such as the New Age synthesis, which encompass a diverse series of groups and movements whose common denominator is the desire for a New Alliance between man and Nature and that aspire to take into account the affective and imaginary dimensions of the human being, including the ethics of love (Díez de Velasco 1995, p. 508; Champion 1995, pp. 709–31).

We will see that this characterizes, precisely, the latest version of King Kong.

3. Skull Island or the Mystery of Death and Origin

3.1. The Mystery of Skull Island

As will be seen below, the presence of the unfathomable, numinous mystery of human existence, of the fear of Nature and death that lies at its base, and of the organization of the meaning of social life that this entails is consubstantial to Skull Island, the place where King Kong lives. Furthermore, they are deeply imbricated with the religious feelings present in the four most important films that, until now, have been dedicated to this mythical character.

The first three coincide in that the boat in which the protagonists travel and that goes to the island meets a fog bank that surrounds it (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). This is what happens, in fact, in the 1933 film (19′, 45″), where, in addition, the fog also covers the jungle inside (47′, 22″). In the second adaptation, the fog is “perpetual” (08′, 35″), while, in the 2005 adaptation, a sailor announces that it “hides” the island itself (37′, 02″), but also the jungle hidden inside it, among mist (01 h, 10′, 48″). Finally, in the film of 2017, it is a set of clouds and a furious storm, also perennial, that totally covers the island, although the fog is also present when the survivors want to escape it in a self-built ship (01 h, 46′, 24″).

Figure 1.

The island of perpetual mist (1933). https://www.pinterest.com/pin/265923552967922496/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Figure 2.

The mist envelops the island (1976). https://twitter.com/login/error?username_or_email=melin2000&redirect_after_login=%2Fhashtag%2Fkingkongmovie (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Figure 3.

On leaving the island, the fog covers it (2017). https://www.reddit.com/r/MovieDetails/comments/8irzvk/in_kong_skull_island_theres_a_boat_named_gray_fox/ (accessed on1 January 2021).

In my opinion, this fog and the storm mean the difficulties, the unexpected, and the contingent of the journey to the island as the existing ignorance about its exact situation and what it holds. Therefore, the journey and its destination are surrounded by enigma; moreover—as will be shown below—they represent a return to the mystery of the origin. It is significant, in this respect, that—in the first version—it is indicated that “there is something on that island that no white person has ever seen” (17′, 10″). Jeff Bridges, on the other hand—in the 1976 film—referring to the role played by King Kong for the islanders, declares that “He was the terror, the mystery, the magic of their lives” (01h, 30′, 20″). It is also indicative of what I have been holding the voiceover of the sailor Hayes, who—in the 2005 film—declares that the journey to the island represents a trip “to the night of the first times” (52′, 50″), something that the film producer, Carl Denham, finishes off when, after the death of his assistant, he comments that the latter “has given his life believing that there is still mystery in this world” (01 h, 24′,45″). As will be later clarified, after the return to New York, this mystery has been commercialized, and put on sale, as almost everything in the film.

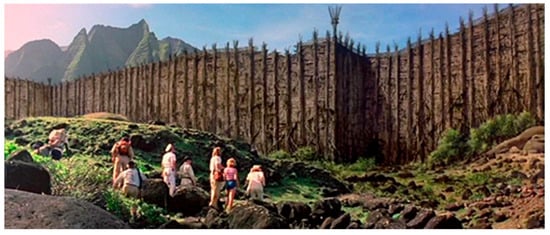

The mystery that the island represents is also corroborated by the difficulty of entering it, as shown by the rugged stone or wooden wall of majestic proportion, which prevents visitors from entering and its inhabitants from leaving. In the 2005 film, for example, the arrival is turbulent, with a rough sea, and the ship colliding with the rocks, to port and starboard (48′, 40″). In the 2017 film, access to the island is equally risky, as is escaping from it alive. In any case, these difficulties work as protection of the island territory, of the physical and mental universe that is preserved in its interior, and of the beings that inhabit it, among them the giant gorilla. Finally, it constitutes a kind of complicated caesura between the outside and the inside and, with them, between the unconscious and the conscious, reality and fiction (Gubern 1974, p. 19), civilization and barbarism, religious feelings and rationality subject to commercial purposes.

3.2. A Journey through Time

On the other hand, for visitors to the island, this border also represents a journey through time and, more specifically, from the critical stage that was momentarily left behind to what lies ahead of them, which is equally full of risks and dangers. Amid this turbulent past and uncertain future, the present they experience upon arrival on the island is no less disturbing, as symbolized by the high walls and palisades or the violent sea storm they encounter.

Now, the nuances of the different versions are remarkably interesting, which distinguish and enrich this temporary, tragic, general vision.

For example, in the 1933 version (Figure 4), the contrast between what is left behind and what is started is evident, because while the horizontality of the sea water highlights its tranquility and “serenity”, the wall in front rises on top of sloping, irregular, sinuous, and “restless” forms (22′, 56″). In addition, the eye of the camera lets you see the progressive verticality, and, with it, the increasing difficulty of ascension that is located in front of the small boat where the sailors are, since the steep island is followed by the wall and, behind it, a very high mountain with almost completely erected walls.

Figure 4.

The outer walls of Skull Island: the ocean, the wall, and the mountains (1933). https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/proxy/3yTNlC8SJYRy_IGNeNFxvhcZXzABt1NCus3CG9-yISnsjidzxA4hAFQRCA4G2rrXGwhjINNfbWxZ_4juVvM-ibuyaFpuIDSkTcTcTBOK0zuFpuxSkTcTBOK0 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

For its part, in the 1976 film (Figure 5), the camera is placed at the same level as the newcomers, so that the high wall barely lets them see behind it, what exists in the interior of the island, with the exception of the wild and almost impregnable peaks of a high mountain (28′, 46″).

Figure 5.

Behind the wall that surrounds the island, there are wild and impregnable mountains (1976). https://www.pinterest.es/pin/499055202450387969/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

In the 2005 film (49′, 50″) (Figure 6), there is no glimpse, as in the other two versions, of any person, on foot or in a boat, but only the undulating wall that mimics the irregular topography of the terrain and, in the background, the sharp mountains, located somewhat far away and next to the wall—all this surrounded by a thick fog that reinforces the feeling of difficulty and mystery.

Figure 6.

The wall and organic forms, exoskeleton, on the Island of the Skull (2005). https://itunes.apple.com/pl/movie/king-kong-2005/id657086845 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

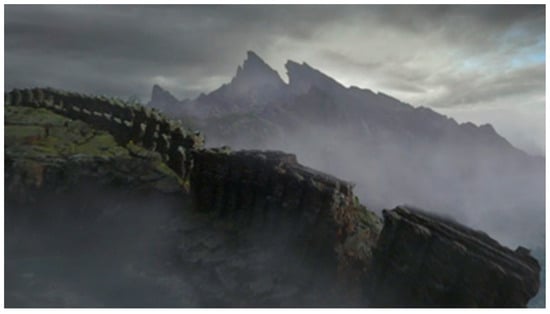

Finally, in the 2017 film (Figure 7), once the helicopters pass through the multiple lightning strikes and the fierce storm, they find themselves in a natural setting of several cliffs isolated by water and, after them, in the distance, a high pointed mountain with two peaks can be seen. Between these atolls, there is also a series of watery and labyrinthine meanders that slow down and visually hide the arrival to the center of the island, and become metaphors announcing what it means to move towards it. In fact, inside, a vertical palisade made of wooden logs protects and, in turn, isolates the town that is located there, while in the King Kong cave, only a small opening allows access, obstructing it.

Figure 7.

Labyrinthine landscape of Skull Island (2017). https://www.kaijubattle.net/saturday-showcase/saturday-showcase-kong-skull-island-concept-art-by-zachary-berger (accessed on 1 January 2021).

3.3. The Mythical Mountain and Cave of the Skull Island or the Cradle and Grave

Kong’s lair is located in a mountain that is, precisely, in the center of the island territory. Not in vain, it is a “sacred mountain” because in it inhabits the one that is considered by the natives their god and because it is the point in which the sky and the earth are united (Eliade 1981, pp. 370–85), constituting the opposition between both worlds—precisely the essence of the religion (Otto 1997, p. 62 ss). Hence, in the mountain, the divine and the human are separated and simultaneously united, and that, in sum, it is, as every liminal space, the place of ambiguity or ambivalence (Turner 1977, pp. 43–44; Turner 1982, p. 23; Turner 1988, pp. 102, 170–71; Alemán Salcedo 2011, pp. 22–388). It is not in vain that the mountains are outside and represent the wild and, consequently, the violent and the marginal, like the giant gorilla itself. Moreover, in them, there are both the reversals of social relations and normal social behavior and the correspondences between the human and the divine, both metamorphoses and the preservation of the past, customs, beliefs, and superstitions (Braudel 1987, p. 25). Hence, they express the primeval, the first living space of humanity and the place of the god on earth, next to the refuge of shepherds and lovers—there, Kong takes the female protagonist of the film, who can procreate a new being. In the same way, if mountains constitute the topic of women, it is because they manifest the subversion of daily life that ends up becoming reversible and, at the same time, because they embody the wombs of pregnant women or overflowing and nutritious breasts (Buxton 2000, pp. 88–101; Husain 2001, p. 54; Vernant 2003, pp. 82, 87).

In the sacred mountain or in the territory of the island, there are a series of caves that fulfill diverse functions. In fact, in all four versions, once the wall or the storm is crossed, the travelers go deep into the island and, between the different vicissitudes and events through which they pass, they enter caves or are affected by them in some way. The mythical caves have been considered, since very ancient times, as sacred (Buxton 2000, pp. 107–11), as they resemble the mythical mountains in that they symbolize the archaic, the birth of the marginalized (King Kong), and the access to the beyond. In fact, they constitute the first city, that of the dead (Mumford 1979, p. 11), since they are used as burial places or are represented as entrances to the other world, although they also embody the vulva or the womb of Mother Earth. In this last sense, they can represent the entrance or the return to the maternal womb and, in this way, symbolize the regression in time, the cultural involution, and the return to the past from the present itself (Gimbutas 1991, p. 233 ss; Gimbutas 1997, p. 47; Husain 2001, pp. 54, 163; Smith 2002, pp. 197, 230–31; Campbell 2015, p. 45; Guénon 1995, p. 213).

Therefore, its existence in the four versions means a trip towards the mystery of the origin incarnated in the maternal womb, although each one of them manifests different variables of this same mitema.

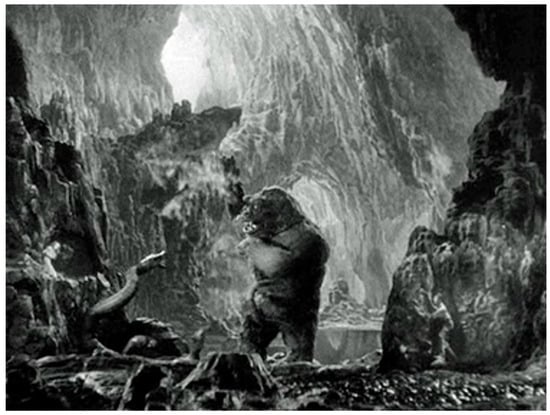

In the 1933 version (01 h, 01′, 50″), for example, the grotto where King Kong lives has a circular (Figure 8), “feminine”, enormous entrance door (Ivanov 1993, pp. 107–17), through which the giant animal can pass without any problem. In addition, the forms of the rocks that surround it have a texture made of scaly folds, almost organic, mimicked by the animal’s hairy body (01 h, 52′, 53″). In this way, it is symbolized that the monkey becomes the origin of the primeval, from where all human beings come from, and consequently, the return to this principle means an escape from humanity itself, which, like history, has led to the disaster of the 1929 crisis that initiates the film (Gubern 1974, p. 20).

Figure 8.

The circular door of King Kong’s lair (1933). http://www.californiaherps.com/films/snakefilms/KingKong1933.html (accessed on 1 January 2021).

In the 1976 version (Figure 9), the access from the beach to the interior of the island is through an open door in the rocky wall with a triangular shape (28′, 46″), Jessica Lange being the first one to cross it, not in vain—this is the typical geometric figure of the feminine in art and religion (GRAP 1993, p. 228; Siret et al. 1995, p. 24; Gimbutas 1997, pp. 42, 47). Here, therefore, the maternal uterus is represented by the whole of the island itself.

Figure 9.

Triangular door of Skull Island. The female protagonist is the first to pass through (1976). http://www.mundodvd.com/king-kong-1976-a-138063/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

In the 2005 film (Figure 10), Jack Driscoll, the famous writer who wants to save Ann Darrow, enters a cave that has a huge circular door (01 h, 33′, 09″), leaving behind the inhospitable and chaotic jungle of trees, branches, and vines, recreated digitally. That is why, in this case, the return to the mother’s womb means, on the one hand, a return to order and an escape from the chaos represented by the crisis of 1929, recreated, in great detail, in the first minutes of the film. But, on the other hand, the digitalization of nature could also express that the maternal uterus is no longer outside of the born, in another body that is the one that generates, but inside the brain that, narcissistic and self-absorbed, transforms human beings into creators of themselves, but at the cost of forgetting or destroying the maternity, and materiality, of nature.

Figure 10.

Large circular door in Kong’s cave (2005). https://www.debate.com.mx/mundo/Las-cuevas-de-King-Kong-podrian-desaparecer-20171004-0436.html (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Finally, in the 2017 version, the enormous “cave”, as a hollow passage, is located underground, where the scientist believes the enormous lizards that reside there could escape and through which the island itself could be subsumed. Humans do not enter this telluric territory, although their feet walk—like the characters of the Odyssey—over abysses and cavities, that is, over the void, floating between life and death (Kerényi 2010, p. 21). No doubt, this is related to the fact that, from that same void, come the lizards that will end up killing and eating several of them. There is also Kong’s lair, in whose outer rocky wall there is naturally a skull molded (1 h, 07′) (Figure 11). Therefore, this and the empty subsoil represent the territory of death—the tombs. The enormous cemetery of Kong’s parents (Figure 12), surrounded by fog, which is full of bones and large skulls, also refers to this: “it is death” comments one of its visitors (1 h, 16′, 22″). Not for nothing—there, the intrepid travelers, who have not heeded the repeated warnings of the American soldier who survived the war of 1945, will be attacked by the giant lizards and several of them will meet a cruel death, when they are swallowed by their open jaws, like caves.

Figure 11.

A skull is carved in Kong’s lair (2017). https://www.comicbookmovie.com/sci-fi/kaiju/king_kong/first-official-kong-skull-island-image-teases-the-enormity-of-the-great-ape-a143485#gs.qcbzic (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Figure 12.

A giant skull in Kong’s parents’ cemetery (2017). https://www.intofilm.org/news-and-views/articles/kong-skull-island-feature (accessed on 1 January 2021).

It is possible that all these ingredients related to the death of the last version of King Kong are linked to the overwhelming presence of war in contemporary American society, that of World War II, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the Gulf War I and II, and its most dire consequence—the destruction of cities, towns, and landscapes and the death of thousands of people.

In any case, in the other three adaptations, the association of the island with death is also present. In the 1933 version, for example, its mountain has precisely the shape of a skull (20′, 25″), which gives it its name, without forgetting that the twelve dead in this unknown territory have had a “horrible death” (01 h, 19′, 03″), especially painful because of its violent and extemporaneous character. In the 1976 film, now when the sailors touch the island’s soil for the first time, it is called “the beach of the skull” by the character played by Jeff Bridges (11′, 20″). Finally, in the 2005 version, at the beginning of the film, some skulls already appear (00′, 52″); when the ship arrives at the island (Figure 13), it meets a dangerous rocky cliff with form of skull (48′, 59″) and at the moment in which Driscoll ascends to the lair of King Kong, to rescue the female protagonist, a skull is seen in the first plane (02 h).

Figure 13.

Upon reaching Skull Island, the Venture collides with skull-shaped cliffs (2005). https://www.deviantart.com/3dnutta/art/King-Kong-Venture-71872158 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

In short, all versions of King Kong express the desire to initiate the entrance to the island, to unveil its mystery and—in a psychoanalytical key—the desire to go through its “door”, the symbol of the feminine, to “penetrate” it. In doing so, they also reveal a possible path to the mystery of mortality and origin, both represented by the maternal womb—the limited, isolated, safe, and protected world of the womb in which, one day, human beings lived happily and from which we were abruptly and definitively expelled and the hollowness or abyss into which we fall after death, or what is the same, simultaneously the cradle and the grave (Eliade 1975, pp. 52, 88; Gimbutas 1989, p. 316; Campbell 1992, p. 389), from which we all come and to which we will all go one day.

In this sense, the anxious search for the origins of life and the mind could be affirmed, the fascination for “the mysteries of nature” and the desire to decipher and penetrate the internal structures of matter manifest a kind of nostalgia of the primordial, of the original, of the universal matrix (Eliade 1999, p. 63; Trías 1997, pp. 79–91). Perhaps also to the interest of North Americans in their origins, it joins the desire to look back, to return to their own beginnings, to recover a primordial situation and history—that is, their absolute beginnings (Eliade 1999, p. 124).

4. The Rites of the Tribe or the Return to the Same, to the Order of Always, Reinforced

4.1. Religion and the Origin of the Island’s Tribal Society

As I indicated in the previous section, the fear of Nature and of death that it represents is at the origin of religion. But, as we shall see below, religion is also the genesis of society itself. So, it could be thought that society is ultimately a construction against Nature and death, the fear, chaos, uncertainty, and contingency it represents.

As Simmel (1964, pp. 17–19) indicates, “the original religious community was the tribe”, so everything I have just indicated is very well illustrated in the community feeling of the tribal society living on Skull Island, reinforced by the religious feelings they profess (Lévêque 1985, p. 188). In this sense, at least three are the religious characters that define this type of society.

4.2. A Hierarchical and Monotheistic Society

First of all, it can be said that the religiousness existing in the four films transmits an idea of a vertical, hierarchical, and monotheistic society. In fact, this religion, and its manifestations and practices of worship—the prayers, the rituals, the dances, the processions, and the sacrifice—implicitly recognize the state of inferiority and dependence of humans in relation to the tutelary divinity (Gil 2001, p. 182) which, in this case, is imagined as gigantic. This is so by the North American taste for the great (Eliade 1999, p. 135) and for the fear of King Kong’s gigantism (Latorre 1982, p. 7), an expression of the sublime, a character that, as seen in the introduction, illustrates the numinous religious sentiment. In fact, the god of the island is much higher than the human beings. No wonder, if in the first version, it is pointed out that “the footprint of King Kong is as big as a house” (44′, 05″); in the second one it is indicated that it is 30 meters (35′, 50″); the same as the wall that surrounds the island, as it is underlined in the third one (37′, 02″). This verticality of the god is symbolically reinforced by the walls of the island, by the high mountains, and by the enormous size of the prehistoric animals. Furthermore, let us remember that Kong is the god that lives on top of the highest mountain of the island, like the gods of Olympus and, therefore, he is the being that touches the firmament. And, simultaneously, he is the upright gorilla, like the humans, that precisely, for this reason, acts as a cosmic axis mediator between the terrestrial and the celestial, between the divine and the human.

We must also count on the fact that King Kong is, at the same time, the king of the territory, the powerful animal that is worshipped—feared—by the aborigines and that directly reflects, as it happens in traditional societies, the concrete experience of the human group, that is, an ambiguous relationship of domination/submission (Lévêque 1985, p. 29). All at once, it is an ancestral deity, cause, and origin of a pristine and primary religious fear, numinous, the characteristic of this horror film (Latorre 1982, p. 8; Cabo 2006, p. 17; Fernández Valentí 2008, p. 60).

Thus, Kong is the monarch of the earth and the only god, with the priest of the tribe assuming the role of delegate of this omnimode power. That is to say, Kong incarnates a monotheistic divinity, with genealogy (in the last version, which shows the cemetery of his parents) or without it and without descendants which is what happens in the rest of the versions. In this respect, it is significant that, as stated in the 1933 film, Kong is part of “a unique kind of animal” (41′, 16″), while in the 1976 film, his longevity is revealed (“300 years of freedom end this way”, states one of the characters (01 h, 29′, 46″))—a longevity proper to a Greek divinity or to one of the Old Testament prophets.

4.3. A Closed and Autarkic Society

Secondly, the island’s society is closed, autarkic, and self-sufficient. In this sense, it is revealing that, in three of the versions of the saga, reference is made to the circular geometry of the island or the giant gorilla. Because the island is far from the known world, it is not permeable to the changes or ideas that come from outside, and because it is limited by water, high mountains, fog, or storm, it folds in on itself.

This is what happens, for example, in the first adaptation in which the door of King Kong’s lair is circular, while in the second one, the references to the circle are multiple: “in the magic circle” you will find the largest oil deposit, says one of the secondary characters (08′,10″); when one of the sailors shows a map, the island is located precisely in the center of a circle (09, 53″); the puddle of a colored liquid that is in the tribe’s settlement is circular (35′, 02″); one of his sailors explains that “King Kong moved in a circle” (01 h, 04′, 48″); the gorilla meets the female protagonist in an area of circular volcanoes (01 h, 16′, 53″); one of the pilots communicates to his companions that “we will fly in a circle over him” (02 h.); and at the moment in which King Kong has fallen to the ground, dead, from the top of the Twin Towers, two circles are formed around his body (Figure 14), that of the people who surround him and that of the fountain that is next to him (02 h, 06′,40″). Finally, in the 2005 version, the entrance to the island is also circular (51′, 39″), while the crowd surrounding the dead ape also forms a circle (02 h, 43′, 08″).

Figure 14.

King Kong’s deceased body is surrounded by a crowd, forming a circle (1976). https://www.todocoleccion.net/cine-fotos-postales/king-kong-1976~x31533754 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

The circularity of the island, of the lair, or of King Kong himself expresses the two existential modalities characteristic of human beings (Eliade 2009, p. 21), since it constitutes a limex that delimits the interior, sacred space, and contrasts it with the exterior, profane and daily space. However, the succession of circles on the island, the sea water that surrounds it, the outer wall that surrounds it, the protective wall of the village against King Kong and his lair, indicates that, unlike the ancient societies in which polarization dominates (Durkheim 1993, p. 88), the profane does not have a clearly defined place in this territory. In addition, in the village, the rites that mimic the movements of the gorilla, and its wedding, flood its small territory without it being clearly differentiated from the sacred.

This explains why the films wish to emphasize that the profane would rather be represented by those outsiders who observe the religious ritual and by the place from which they come, as will be seen in the following section.

In any case, if the island and its god are circularly delimited, so is the island’s tribal society, with its own traditions, rituals, and customs, so strange in the eyes of visiting observers. And, if this is so, then it can be inferred that this society has a cyclical conception of time, marked, as will be seen later, by the sacrifice offered recursively to its almost eternal divinity and that it intends to exorcise the linear temporality of death.

4.4. A Hybrid, Matriarchal–Patriarchal, Hunter–Warrior, and Tribal–Fraternal Society

Thirdly, the island’s society is hybrid, matriarchal and patriarchal. Its divinities, which are of truly diverse origins, are united in a syncretic myth that seeks, precisely, to relate the masculine and feminine aspects of the divine and, consequently, to fuse the two societies, that of the Mother Goddess and that of the masculine God (Campbell 2015, pp. 207, 213).

On the one hand, in the 1933 movie, in the lost and remote island, old material divinities, not heavenly, of the Mother Goddess survive; that is, the very island, water, mountain, forest, earth, and sky, all of them full of danger and producing a numinous fear. So, it is not strange that they constitute the true natural components where King Kong and natives live, and from this, we can see that the fundamental elements of religiosity are basically natural, material, and carnal. In addition, in the 2005 version, the tribe is guided by an old witch and her young daughter (Figure 15 and Figure 16), witnesses of a society that still takes into account a certain sacred role of women (Montagne 2008, p. 245).

Figure 15.

An old witch guides the tribe (2005). https://www.google.es/imgres?imgurl=https://pm1.narvii.com/6860/5366dbdce98d1a1a8fb2cff189afad7a3e00227fr1-512-287v2_hq.jpg&imgrefurl=https://aminoapps.com/c/horror/page/blog/peter-jacksons-king-kong-review/WJdF_XuL825Brg35dZPzr7ojPqqBgjE&h=287&w=512&tbnid=WZ4Uc2NMO7gUGM&tbnh=168&tbnw=300&usg=AI4_-kQ_hO7zVPk4Jw7LCSB9Zh7MDtk-kQ&vet=1&docid=qb-A9OSXyKEEfM&itg=1&hl=es (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Figure 16.

The daughter of the witch (2005). https://www.pinterest.es/pin/247205467020036176/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Now, in this first version, if the matriarchal ingredients of society are evident, so are the patriarchal ones. Not in vain, the chief of the tribe is a man, his god is male, and a virgin is sacrificed to this divinity, something typical in the hunting societies of prehistory (Flynn 2002, p. 25; Iriarte and González 2008, pp. 77–263; Jordán Montés 2005, pp. 68–69). In this sense, the members of the tribe do not seem to be farmers or stockbreeders since no tools or farm animals are shown in the film, although some chickens are (01 h, 11′, 15″), so they must be hunters or gatherers. Furthermore, they do not sacrifice animals to the god Kong either, but their youngest women are.

The patriarchal society, on the other hand, can also be seen in a multitude of icons that refer to the phallus or to the male principle, such as, for example, the walls in which pointed sticks stand out at their summit, the pointed mountains, the spears of the members of the tribe or the posts where the actress is tied up, in the versions from 1933 and 2005 (Gubern 1974, p. 15).

In addition to this, in the 1976 film, the aborigines who participate in the rite, disguised in ritual clothing and masks or with painted faces and carrying spears, are all men (36′).

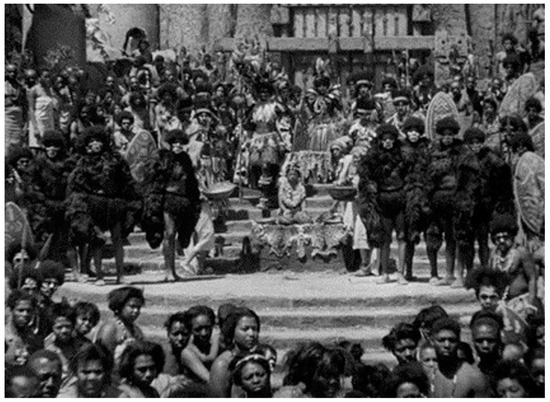

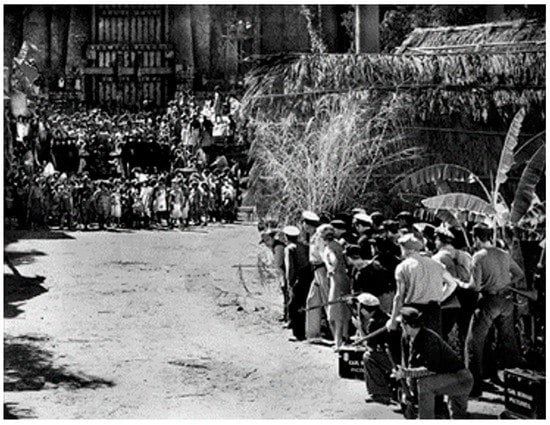

When members of the tribe perform an ancestral marriage rite, in the 1933 version (25′, 04″), the woman who is the object of the ritual, dressed in white, is significantly kneeling while around her dance the men dressed in gorilla skins and performing ceremonies with feathers, a male sign of war, garlands and wreaths of flowers, feminine metaphors, abound (Figure 17). And the fact is that she is the bride, as the chief of the tribe says (28′, 15″), the one who is going to be prepared to get married, but with King Kong, which means that, in fact, she is going to be sacrificed, given to the monster, and never returned to the tribe again.

Figure 17.

Ritual scene of the settlement on Skull Island where preparations are made for “King Kong’s bride”. Dances in monkey costumes and white paint on their faces. https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/proxy/Ktl_kG_d4msb2WO_6Za9JzrqfT0ZgF14LbltZaluXmsZ2Dek2mYzWcCHdr6ngYXQDmVdRIxFaikN29QEaTp0K8ZMskHmJOnJzDdXejUgppZKV3OwsOr3dbRl9Ul0q4Rvat5ENq6wg7bH1-UW3S8MQ4NJ0u-32zvE (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Thus, it does not seem that the society of the first three adaptations knows the degree of development of agriculture or livestock but is in a state of civilization more fully inserted in the natural world and in hunting and warring societies.

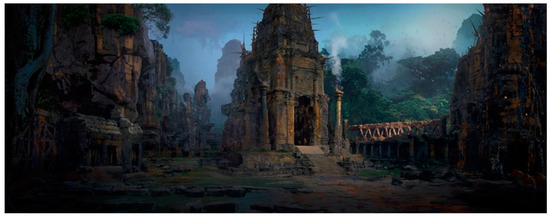

On the contrary, the pacifist members of the 2017 film’s tribe do not look like warriors and, moreover, Kong is a god with different characters from the previous versions. He is clearly a benefactor for the islanders, “the last of their saviors” (53′, 16″), so they worship him without apparent submission or fear. This divinity, then, resembles more Christ or Buddha than Yahweh, while their society would be closer to the evolutionary stage of the “prophetic or salvation era”, with its ethics of brotherhood, announced by Max Weber (2017, p. 417). In contrast, in previous adaptations, “tribal societies” prevail, while the “individualistic modern society”, capitalist or rationalist (Bellah 2017, pp. 279–300), defines New York more appropriately.

Expressions of this brotherhood before the god and before the members of the tribe are the same paintings that men and women wear on their faces (50′, 52″) (Figure 18), the absence of sacrifice of the young women, the buildings that look like Buddhist temples (Figure 19), and the fact that they are a man and a woman, equally, as leaders. Moreover, their orange paintings, their clothes, and the pacifist ideology they profess gives them a Hindu or Buddhist air (non-violence, Ainsa, is fundamental in Hindu religions (López 2006, p. 261 ff)) which, on the other hand, marries well with their savior god, although, of course, the natives are serious and never laugh, a sign of the serious tone of the character of their worship. On the other hand, the same type of paintings appears inside the phantasmagoric ship abandoned on the island, Wandered, perhaps a veiled reference to the “pilgrims” and the pilgrimage that is so important in the religiosity of India and, particularly, in Buddhism (De Give 1992, p. 27 ff). Not in vain, here, the tribe has built a sacred enclosure (51′, 37″), a center of worship of their protective god against the giant lizards, as explained by the iconology of the primitive drawings on the walls and numerous objects.

Figure 18.

The leaders of the tribe are a man and a woman. The members wear paintings on their faces and bodies almost as if they were Buddhist “monks” (2017). http://phubb.blogspot.com/2017/08/kong-skull-island-2017_3.html (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Figure 19.

The constructions of the town of Skull Island look like Buddhist temples (2017). https://formlanguage.artstation.com/projects/eXweZ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

4.5. The Sacrifices and Rites of Passage in King Kong or the Exorcism of the Crisis and the Renewal of Society

In the four versions of King Kong, the sacrifice is a central religious ceremony, although the gorilla is present in all of them, while the woman is the protagonist in only three. The main function of this sacrifice ritual is to overcome any form of social crisis and the continuous crises of society that are at the origin of each of the King Kong films (Roche Cárcel 2017, p. 511 ff), giving it, therefore, continuity. In this sense, the mechanism of sacrifice continues to work in today’s capitalist society, inasmuch as the last one crisis, that of 2008, like the 1929 crack that is at the base of the 1933 version, “is making the magnitude of such violence clear, with a flagrant visibility of the relations of domination in society that has led to more and more sectors and social groups affected by a growing vulnerability being led to the sacrifice of markets that must be appeased” (Alonso and Rodríguez 2013, p. 97).

At the same time, the sacrifice perpetually renews the year, dramatized by the rituals that celebrate the annihilation of the old to be replaced by the new; or with the succession of generations that, in the initiation rites with sacrifice, is achieved through the replacement of the old generation by a younger one (Burkert 2011, pp. 57–70).

But let us see how the two types of sacrifice develop in the saga of the giant gorilla.

In relation to the sacrifice of King Kong (Figure 20), the film seeks to appease in the audience the gigantic fears of the past and present, real and filmic, as well as ending the old to renew society and give it continuity. In this sense, King Kong embodies both Nature and the monarchical political system and is part of an atavistic world and society, which the American republican, industrial, and modern society wishes to come off or forget.

Figure 20.

King Kong is crucified (1933). https://www.tíritumind.com/check-onscreen-evolution-king-kong/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Therefore, in the 1933 film, the great gorilla is tied with chains in a crucifixion posture (01 h, 19′, 30″), with an evident religious and martyr connotation (Gubern 1974, p. 17).

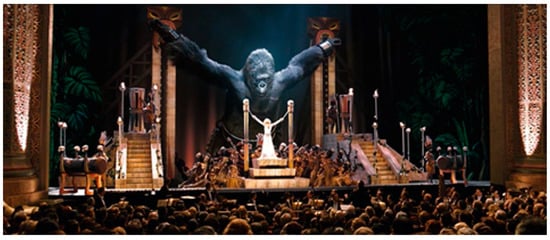

Likewise, in the 2005 film, Kong is presented to New York society in a theater, chained to an altar of sacrifice located just in front of another one where the beautiful actress is tied (02 h, 21′, 18″) (Figure 21). In this way, they want to distinguish the cruel sacrifice of a human being that is done in the ancestral tribal society of Skull Island, from the more permitted sacrifice of an animal in modern American society, that which is accustomed to slaughter, commercially—millions of animals in specialized slaughterhouses. This ideological contrast is reinforced iconographically by presenting Ann and the gorilla face to face, but in contrast, because if she is human, female, short, blonde, and dressed in white, he is an animal, a gorilla, very tall, naked, and with dark hair. However, in spite of the differences, both are sacrificed for the benefit of a patriarchal society, the tribal one, but also the New York one that flees from both the fear of nature and the ancestral religiosity that the monster represents and whose sacrifice was intended to exorcise.

Figure 21.

The double sacrifice, King Kong and the female protagonist (2005). https://twitter.com/login/error?username_or_email=melin2000&redirect_after_login=%2Fcinemartistry%2Fstatus%2F867802830735888384 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

On the other hand, Kong’s martyrdom, in the 2017 version, differs from previous movies in that the gorilla is not placed on the cross, but is about to be burned to death by the colonel of the American army, to the point that we witness his body completely surrounded by flames (01 h, 32′, 40″) (Figure 22). From a religious point of view, it is very similar to the rites of purification and immolation of sacrifice and the dead, in India (López 2006, p. 266), for example, waiting for its rebirth in the next life (Zimmer et al. 1995, p. 21 ff). No wonder Kong emerges, surprisingly, safe and sound from the flames that totally surround him.

Figure 22.

King Kong is cremated as in Indian religions (2017). https://karllindberg.artstation.com/projects/4vqQL (accessed on 1 January 2021).

In front of this religious feeling, there is that of the military man, who wants to kill Kong, the god, the king, and what he represents, with a modern mentality that exemplifies, with its obsession, stubbornness, cruelty, and scarce reflection on the unwanted consequences, the “monster of reason” (Rousseau 2003, p. 265); Goya, Caprichos. The dream of reason produces monsters (Vaughan 1995, p. 86). It is significant, in this respect, that he considers that “man is the only king”.

As far as the sacrifice of women is concerned (Figure 23), being tied to a sacrificial altar, it fulfills different functions from those of the gorilla. In King Kong, this rite is similar to those of passage (Turner 1982, p. 24; Van Gennep 1986, pp. 20–30; Turner 1988, pp. 134–35, 206; Alemán Salcedo 2011, pp. 69, 351), as the young woman will pass through the city gate (37′, 22″, in the first version; 47′, in the second), leaving behind her previous biological stage and entering the heart of the island, a symbol of the new life cycle.

Figure 23.

The blonde woman is sacrificed on an altar (1933). https://www.pinterest.es/pin/354165958186059607/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

However, when she is handed over to King Kong, the display of this ritual in the film differs from traditional rites of passage in that she will not only cease to belong to her society, but, and this is the worst, she will no longer be alive. It therefore fits better into a human sacrifice, with which that society seeks to divert to a “sacrificial” victim the violence of King Kong, itself an embodiment of the violence of the contemporary economic crisis, that threatens to hurt its own members and those it seeks to protect at any cost. Sacrifice therefore serves the function of controlling internal violence and preventing the outbreak of social conflict. Consequently, the “primitive” religiosity of the island, and that of North America, domesticate violence, regulate it, and channel it, concentrating it into a scapegoat (Girard 1983, pp. 12–27).

But, on the other hand, the sacrifice of the female victim fulfills another important function in King Kong, since, paraphrasing the philosopher María Zambrano (1973, p. 39), men give something to the male god, the fresh flesh of the nubile woman, to try to calm the latter’s rage. In return, the divinity will leave humans in peace, momentarily, until the next and recursive sacrifice, and, meanwhile, society’s fear is partially appeased.

The luck for the unfortunate woman who was to be sacrificed, in the 1933 version, is that the members of the tribe find, by chance, an even more appropriate victim: a beautiful woman, foreigner, with “golden hair” (28′, 55″), blond and golden, who will surely be a “gift” (29′, 05″), much more exciting and appreciated by the giant gorilla. Otherwise, the sticks where our protagonist is tied up, violently, have a phallic form—as has been indicated—and are surrounded, as in the 2005 adaptation, by torches of fire (36′, 20″) (Figure 24), a patriarchal metaphor of the feminine brilliance that will attract, that will “warm up”, the wild beast.

Figure 24.

The woman is sacrificed on an altar surrounded by fire (2005). https://quotesgram.com/king-kong-2005-quotes/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

5. Conclusions: The Survival of Religiosity in the City of Skyscrapers

5.1. New York or the Return to the Same, Reinforced Order

When, in the 1933 version, the sailors and the leading actress enter the island and contemplate the rites performed by the natives (25′, 09″) (Figure 25), they are prey to amazement and terror. That is why I understand that the same thing happens to them as to the théorós of ancient Greece, an envoy to other cities who observed, at a certain distance (he was a foreigner), the festivities and religious rites that were celebrated there. But this distance was not insurmountable, since that religion was similar to his and, therefore, did not seem to him to be totally alien (Parménides 2007, p. 65). Something similar happens to the North American visitors to the island, since with the tribal rites, they remember their own, hierarchical and patriarchal, which still represent the deep roots of their modern society. Thus, just as on Skull Island, its city also abounds in phallic icons, the towers, the tall and steep chimney of the ship, the weapons of the sailors, the bridges, the trains, and the airplanes (Mumford 1979, p. 24), and the verticality in the skyscrapers is equally present. In this last sense, the sequence, from the 1976 version, in which the shapes of the two mountain peaks where King Kong lives resemble the twin towers where he will battle with the helicopters (01 h, 52′, 08″) is very interesting.

Figure 25.

The outsiders contemplate, “hunt”, the rites of the natives. https://c4.wallpaperflare.com/wallpaper/96/407/736/movie-king-kong-1933-wallpaper-preview.jpg (accessed on 1 January 2021).

Furthermore, far from the old religiosity disappearing, in the modern civilization, echoes of it survive, as the god Kong also produces terror in the streets of the Big Apple. Without forgetting that he is sacrificed—crucified, chained with his arms in cross, in an evident religious connotation and of martyrdom, by the rationalist mercantile society and of patriarchal face, in an identical way as it is, in the island of the Skull, Ann Darrow by the “savages” of the island.

However, New York society considers the religiousness of the Isla de la Calavera as something atavistic, wild, and primitive, especially in the second and third versions. Thus, in the 1976 version, the character Wilson, upon contemplating the ritual of the tribe, declares that “it is a religion of madmen” and, in an ironic way, that “the priest dresses as a monkey for the ceremony” (40′, 47″). At the beginning of the 2015 version, the island is already defined as “a primitive world”, as “the ruins of an ancient civilization” (08′, 10″) and, moreover, the natives are characterized as aggressive and frightened; in fact, they kill one of the newcomers (57′, 50″). Because of this, the ritual they carry out is ridiculed, and spectacularized, later on in the theater of New York (02 h, 19′ 45″), at the same time that it is considered a “wild ritual”, in which the “sacrifice of a sweet woman” was executed (02 h, 20′, 45″).

In short, the result of the myth of King Kong is that the travelers in the film, and the spectators of reality, contemplate themselves through the observation of “the other”, of the generalized otherness that the tribal religion implies and the generalized crisis of values and identity (Augé 1996, p. 11 ff.) that contemporary American society is experiencing. Now, it is extremely paradoxical that what reflects this otherness are his own fears, what truly frightens him, what he really is. Not in vain, the Other is always the projection, the rejection, or the denial of a part of the I, that is, that “the Other is the I plus the representation of the difference between both” (Nair and De Lucas 1999, p. 125).

Thus, the journey towards the other imaginary, towards the circular island of King Kong, being a myth, does not presuppose more than a return to the New York island, in which the fears of the present are replaced by the filmic ones, returning again to the order of always socially reinforced (Burke 1991, p. 288). Once this point is reached, one may ask what then remains in this society with a male and rationalistic face at the moment when the god-king is sacrificed. In this respect, linked to what has been defended in this article, one could answer that hierarchical, self-absorbed, and narcissistic humans feel melancholy about what they could have been or stopped being and are still not as civilized as they would like to be.

5.2. From the Earth to the Sky: A Human Journey Opposite to That of the Gorilla

Therefore, it is very revealing that King Kong, and the concept of Nature and the type of religiosity it represents, are defeated in the first three versions. By whom or why, has technology really killed them? In the 2005 film, after saying goodbye to his love, King Kong finally falls down. In a very striking image (02 h, 41′, 53″), one can see how his body flies at full speed towards the ground, towards the void through which nature feels horror (Gubern 1974, pp. 83–84). Meanwhile, in the dome of the skyscraper, the woman’s body, the object of his desire, remains lying and immobile, and increasingly distant.

It is true that, in these three film adaptations, before the image of King Kong collapsed on the ground, shrunk and “emptied of its form”, the question of who ultimately killed the beast is answered in the same way. In the 2005 film, for example, a journalist says that King Kong is a “dumb animal who knows nothing” and that it has been the planes—the modern technique—that have brought him down. To which Denham responds that it was not the planes, but “It was Beauty that killed the Beast!” (02 h, 43′, 53″).

But has it really been love—Beauty—that has managed to defeat Nature and the divinity incarnated in King Kong? Honestly, I am afraid it is not. It was clearly the airplanes that did it. In relation to this, although it has nothing to do with King Kong, the photo posted on the Internet of the inauguration of the four new skyscrapers in Madrid is very revealing, accompanied, on the occasion, by a last generation military plane (in the 1933 version of King Kong, there are four fighters that attack the gorilla (01 h, 28′, 15″)). After all, technology accompanies technology—that is, skyscrapers that want to “rip the sky” are linked to the planes that fly over them. In this sense, it should be remembered that the fundamental objective of science and technology is, like that of religion, to know Nature in order to overcome its “hostile, capricious and deadly nature” (Horkheimer and Adorno 1999, pp. 60, 70). In addition, the “magical” desire to fly (Eliade 1995, p. 102 ff) has always escorted the human being since he became aware that he is a human being who wants to “rise” from nature to transcend it, “religiously”, and, in short, to distinguish himself from it. Or what is the same, to make exactly a trip, this one fully human, in the opposite sense to that of King Kong, the animal, that from the sky goes towards the ground.

But is it not this upward journey a sign of the continuing need for religious feeling in North American contemporary society?

5.3. An Unfinished Myth, Fed by a Succession of Crises and Fears

The 2017 film offers another, perhaps more hopeful, message, although it is also full of disturbing omens. Kong is not killed by humans; moreover, a part of them helps him in his mission to destroy the real monster of the film, the giant lizard. Furthermore, his size is growing more and more, which indicates that his future presence, physical and spiritual, will increase with time in the island society, in the one of New York, and in the whole world. Without forgetting that, it announces another probable future version and that, therefore, the history and the myth of King Kong have not ended, nor have the social crises and the fears and anxieties that they generate, which are the ones that stimulate the horror movies (Gubern 1979, p. 11; Kracauer 2015, p. 40).

However, uncertainty also accompanies the utopian message of the 2017 film, for as the British soldier, with the function of an explorer, tells the photographer, “nothing comes back from the war”, at least “not completely” (1 h, 06′). This realistic assertion seems to be confirmed by the balance of the traumatic crises and dramatic events experienced by contemporary American, and, in part, Western, society, after which nothing has been the same: the crisis of January 29, the oil crisis, the 2008 crisis, the attack on the Twin Towers, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the Gulf War, the war against the Coronavirus, the attempted “coup d’état” of 6 January 2021.

Perhaps, for this reason, we should not forget that crises generate fears and that these renew the myth of King Kong and the religious background that nests in the human soul.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alemán Salcedo, Eliana. 2011. Homo Transiens, Liminaridad y Límites en Disputa. Claves Interpretativas Para una Sociología de lo Liminar. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Pública de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain. [Google Scholar]