Abstract

This article examines the liturgical life of the “Underground” Greek Catholic Church through the example of the life of the prominent priest, writer and poet, Roman Bakhtalovskyy, CSsR. After 1946, the Soviet government in Ukraine prohibited the activity of this Church. Therefore, the sacramental activity of Greek Catholic priests was performed in complete secrecy until 1989. The analysis of archival criminal cases is an important source of research during this difficult period for the Church, in which pastoral activity was a pretext for arrest and imprisonment, and sacred objects were seized during searches. This article analyzes in detail the criminal case of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy, which was opened by special services in 1968–1969. The confiscated objects of analysis provide valuable information about the liturgical activity, devotional practices and spirituality of that period of persecution of Catholics in Soviet Ukraine which coincided with the reforms of the Second Vatican Council and their implementation elsewhere.

1. Introduction

The Greek Catholic Church (GCC) (Greek Catholic Church (GCC) is the Eastern Catholic Church, which follows the Byzantine (Greek) Rite. In Ukraine, this Church was created due to the Union of Brest in 1596. Therefore, from one side its leaders decided to realize communion with the Pope of Rome and, from another side, they acknowledged that the Church was one of the successor Churches, which accepted Christianity under Great Prince Volodymyr the Great of Kyiv (963–1015). This Great Prince, who was the ruler of Kyivan Rus’, established Byzantine Christianity in his territory. Christians of the Byzantine tradition who did not accept the Union with Rome in 1596 were called Orthodox.) was formed due to a decision by a certain group of Orthodox Christians of the Byzantine tradition. The reason for this formation was to make unity with the entire Catholic Church, headed by the Bishop of Rome (Pope), with a view to restore the unity of the Churches, which was lost after East–West Schism in 1054.

During the period of the existence of the Soviet Union, the activities of the GCC were completely prohibited by the state. The persecution of Catholics also took place in countries of the Warsaw Pact, especially in Poland (Roszak and Tykarski 2020, p. 19). The members of the GCC were forced to take their religion underground (illegally), and perform their ministry inconspicuously; however, they were at risk in doing so. As a result, Greek Catholics were persecuted, arrested, exiled, and imprisoned. The believers were ready to die for their faith as true martyrs (Olivedo 2019, p. 31). Despite the Bolsheviks’ efforts to completely destroy the GCC, it managed not only to endure these difficult periods, but continued to develop and grow by attracting new members, who decided to join the clergy and monastic communities (Voynalovych 2005). The survival of the Church in extremely difficult conditions was primarily due to the merits of its active members, namely the courageous clergy and consecrated persons, as well as active and intrepid laity. Moreover, the provision of liturgical and pastoral service became a reality through the activity of the priests who performed their ministry in a specific place and time, without fear of becoming victims of the punitive Soviet system (Hurkina 2008, pp. 279–80).

One of the most active priests during the “underground” period of the GCC in the Soviet Union was Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy. The authorities called him “the ideologist of the Catholic underground” (Oliynyk 2017, p. 228). In his religious life, he experienced almost the entire 45-year period of prohibition of the legal activities of the GCC and survived, remaining faithful to his Christian values. He died at the beginning of “perestroika” (“restructuring” in Russian) in 1985. This reform, initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev, is considered as a weakening of the regime, which was the beginning of the crash of the totalitarian system.

In 1968–1969, despite his old age and poor health, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was searched and arrested. This happened on 12 October 1968 in a town of Kolomyia. He was accused by authorities of illegal priestly activity. After that, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy was interrogated and served a full prison sentence for his Christian faith, but in spite of torture, he remained faithful to the GCC. A criminal prosecution was initiated against him (Appendix A). When Ukraine obtained its independence, his criminal case was declassified, thus enabling us to obtain more detailed information about his life in extremely difficult conditions. This information offers a window on the stressful circumstances in which the Greek Catholics in the Soviet Union existed, operated and developed (Oliynyk 2018, pp. 79–80).

2. Liturgical and Pastoral Activities of the Greek Catholic Church in Ukraine during the Soviet Period

From the very beginning, the Soviet state centered in Moscow, viewed Greek Catholics as an enemy group that opposed Soviet rules and government. They were critical of communist political views regarding and their vision for building a society. Greek Catholics defended the right to private property; they were opposed to collectivization as well as to the promotion of radical atheism. They were against the cult of personality of Soviet leaders; these were the elements on which Soviet propaganda was working very intensively. Additionally, the Greek Catholics tried to preserve the language, culture, and national heritage of Ukrainians (Kontsur-Karabinovych 2011, pp. 47–49).

One of the most important reasons why the Bolsheviks treated the members of Greek Catholic Church as their enemy was the unwillingness of its clergy and lay people to cooperate with the Soviet Committee of State Security (KGB). It is not a secret that security services tried to control every area of public and private life of USSR citizens, eradicating any dissenting opinion in society. The GCC did not agree to its dependence on KGB agency and did not neglect the basic Christian and evangelical principles and practices (Serhiychuk 2006, pp. 355–56).

2.1. Historical Background of Liquidation of the GCC by Soviet Regime

The first conflicts between the communist authorities and the GCC leaders began in the autumn of 1939, when the Red Army invaded Western Ukraine. From the very beginning, the communist authority decided to impose new restrictions on the GCC with the intent of its complete elimination. At the end of 1939, the communist authorities decided to immediately end the academic year at Greek Catholic seminaries in Peremyshl, Stanislaviv and Lviv. They prohibited the publication of religious books and magazines, ruined church archives, and limited the activity of clergy to church territories, as well as closing monasteries and increasing taxes for parish communities (Haykovs’kyy 2006, pp. 30–31). The KGB authorities completely ignored the fact that the GCC was a well-organized community and was very active and popular in the west of the country. (In 1939 the GCC had 3040 parishes, 4440 churches. The GCC opened five seminaries, where studied 540 seminarians, two schools and established 127 monasteries. The GCC was headed by the Metropolitan in cooperation with ten bishops and 2930 priests. 520 monks and 1090 hieromonks were living in the monasteries. The number of lay people reached four million 370 thousand people (Bilas 1994, p. 308; Baran 2003, p. 64). After the World War II the Soviet authorities also persecuted the members of other Christian and non-Christian denominations, but the large number of Greek Catholics and their active work forced the secret services to pay more attention to them.) Although the intensive activity and moral authority of the GCC were important factors that determined the social and political life of the people (Bociurkiw 2005, p. 29), it was clear that it was only a matter of time before the liquidation of that Church by the Soviet authorities.

In the spring and summer of 1944, the Nazis were expelled from the occupied territories in the western part of country (called Halychyna) and the Red Army returned again. Firstly, it seemed that the Soviet authorities began to treat the GCC more tolerantly and cautiously. However, that external tolerance meant nothing more than their well-prepared and well-argued way of fighting against the Church. Then, the KGB began to gather a lot of information about the life of the GCC clergy, monks and lay people as well. They were paying more attention to their behavior in relation to the new government. In the spring of 1945, the police began to make arrests of the leaders of GCC. (Before 21 April 1945, the communist authorities arrested the thirty-two most active members of the GCC in the Lviv region: the head of the Church, Metropolitan Josyf Slipyy, two bishops, tventy priests, two deacons, three seminarians, and five lay people (SSASSU, pp. 282–94).)

At the end of May 1945, the Soviet government decided to declare dominance of the GCC by not allowing the people to practice their faith freely in society. A movement was created within the Church, whose aim was to cancel the Union with the Vatican, thereby reviving the long-forgotten idea of joining the Greek Catholics to the structure of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). (After the Bolshevik revolution occurred in the Russian Empire in late 1917, the hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) agreed to cooperate fully with the new Soviet government as well as the KGB. For the Church, this cooperation signified total control by the state security services as well as decreasing its moral authority in society. The ROC gave a silent consent to the process of atheization in the country, and the right to public activity was guaranteed for that Church (Kontsur-Karabinovych 2011, pp. 99–100).) For this purpose, the Initiative Group was created. It consisted of three well-known and authoritative priests, who agreed to cooperate with the KGB (Serhiychuk 2001, pp. 59–67).

On 29 May 1945, the Initiative Group issued a declaration with an assessment of the Union with the Vatican. Unity with the Pope was seen as “a manifestation of betrayal against the Ukrainian people”. The Group also appealed to the members of the Parliament in Kyiv to recognize them as the temporary highest administrative and legislative body of the GCC. At the same time the Group asked permission to begin the process of joining the GCC to the ROC. The declaration also contained an ideological call for cooperation addressed to all Greek Catholics in Western Ukraine to proceed with the process of abolishing unity with the Vatican immediately (Zbrozhko 2014, p. 481).

This time KGB agents were very careful and insidious. They used manipulation tactics in their struggle against GCC (SALR, pp. 29–33). As part of the preparation for the official prohibition of the GCC’s activities in society, the security services created the impression that the liquidation of the Union with the Vatican and joining with the Moscow-based Orthodox Church for GCC was the expression and desire of most of the clergy and lay people as well. It seemed that the members of the GCC voluntarily agreed to join the Moscow Church. At the same time, KGB officers launched a campaign to gather compromising materials about the GCC. The major radio and newspapers started the process of criticizing and accusing the leaders of the GCC of collaborating with the Nazis during the period of occupation. They were also accused of showing their support for the Ukrainian resistance movement, whose participants fought against the communist regime (CSAPOU, pp. 7–17; SALR, p. 34). They hoped that by destroying the moral authority of the GCC in society it would give them the mandate for its liquidation as well as justifying their activity in the eyes of the international community (Serhiychuk 2001, pp. 40–80).

At the end of July 1945, the Initiative Group headed by Fr. Havryil Kostelnyk and instructed by KGB, started secret conversation with GCC priests of the Lviv region. The Group tried to convince them to support the liquidation of the old Union and the creation of a new one—with ROC. A number of activities aimed at the immediate accession of the GCC to the ROC are described in archival documents as “a large-scale political action of the highest importance” (SALR, p. 9).

The final stage of the liquidation of the GCC was the holding in Lviv of a Pseudo-Council chaired by Fr. H. Kostelnyk. This event was held on 8–10 March 1946 and was not attended by any of the bishops of the GCC. The main decision of this “Council” was the liquidation of Greek Catholic communities and the proclamation of a “voluntary” joining of the ROC structure. Of course, the Pseudo-Council was held under the total control of the KGB, and after that event the number of arrests of persons who disagreed with the decision of the “majority” was increased. After this the large number of clergy, monks and laity who belonged to the GCC went underground to continue their activity illegally as a persecuted Church (SALR, pp. 10–20). This lasted until 1989.

2.2. Periods of Underground Activity of the GCC and Their Specifics

Since 1946, the Soviet authorities completely prohibited the GCC: it was deprived of property rights, was declared an illegal organization, and participation in its underground life incurred criminal liability (Kontsur-Karabinovych 2011, pp. 110–11). However, in the period 1946–1989 the KGB’s attention to the GCC underground activities varied in its intensity. This attitude was dependent on the state leader in Moscow. The first phase saw Stalinism, which was implemented by Joseph Stalin during the period 1922–1953. Nikita Khrushchev ruled the USSR from 1953–1964, and this second period we call the Khrushchev “thaw”. Leonid Brezhnev’s (1964–1982) period is known as the “Era of Stagnation”. The period of “Perestroika and Glasnost” was associated with the last leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev (1985–1991), which led to the collapse of the USSR (Baran 2003, pp. 394–95). Therefore, it is worth focusing on these three most important periods of persecution of the GCC.

The most intensive period of persecution was during Stalin’s rule and especially his later years. The Soviet authorities not only realized their plan about the liquidation of the structural units of the GCC, but also arrested all GCC leaders promptly before the Pseudo-Council: the head of the Church Metropolitan Josyf Slipyy and many bishops were arrested, as well as a large number of priests (about 100). All GCC bishops refused the proposal to cooperate with the Soviet authorities, although they were under psychological pressure. Most of the arrested clerics received long prison terms and exile in the northern regions of Russia (Siberia) due to the court verdict. In exile they were all forced to work hard. They were subjected to torture and other cruel and inhumane treatment in the Soviet penal system (Shlikhta 2004, pp. 262–65).

As the GCC needed further hierarchical leadership and guidance, and all the hierarchy were serving long prison sentences, other priests who avoided arrest were secretly appointed to perform the role of GCC leaders by Metropolitan J. Slipyy before his arrest. (These were: Archimandrite Klymentiy Sheptytskyy (1869–1951), Ivan Ziatyk (1899–1952), Mykola Khmilovskyy (1880–1963).) These few persons were able to manage the Church for a very short time between 1945 and 1950: most of them were arrested, and some with non-Soviet citizenship were deported from the country. As a result, a very small number of clergies who did not join the ROC remained free (Bociurkiw 1993, pp. 123–25). By 1950, all the male monasteries of the GCC were closed. The last convent of the Basilian Sisters in Sukhovola ceased to exist in 1952. Along with the closing of monasteries, which were connected with arrest of its members, all the monastery’s schools, shelters, kindergartens, and other projects were shut down (Velykyy 1968, pp. 436–38). Monks and nuns organized secret small communities. They stayed together and had to get a job like all other citizens.

The period of Khrushchev, who came to power after Stalin’s death in 1953, is considered to be a time of easing of persecution of the GCC (Danylenko 2008, p. 8). Many of those who served prison terms and long-term exile were released and most of them returned to Ukraine. In 1953, Metropolitan J. Slipyy returned from Siberia and was sent to Moscow. Kremlin authorities tried to persuade him to join ROC and promised him a high position in the hierarchical structure of that Church. Besides that, the Soviet government wanted him to be a mediator to normalize the relations between the Soviet Union and the Vatican. However, Metropolitan Slipyy rejected that proposal. In 1958 he was arrested again, and in 1959 was deported to Siberia for forced labor for a term of seven years (Khoma 1987, p. 27). In 1963, he was given early release and expelled from the USSR.

Some priests and bishops who returned to Ukraine as a result of the “Khrushchev thaw” continued their underground religious activities, although doing this was strictly forbidden. Thus, the transition from Stalin’s totalitarian methods to Khrushchev’s era did not mean the legalization for the GCC. The repression continued and even since 1957 the KGB surveillance for religious persons was increased. Many of them were arrested again. However, these persecutions were not as considerable as during Stalin’s period, but rather situational and fragmentary. The Soviet authorities hoped that due to the hierarchy, which at that time consisted of elderly people with impaired health, the GCC might have little prospect of development in the future. The secret services expected that this was the last period for the GCC (Bociurkiw 1993, pp. 129–35).

The period of leadership of the Soviet Union by L. Brezhnev, who came to power as a result of the successful removal from power of Khrushchev in 1964, at first did not seem threatening to the GCC. After all, until 1968, although Greek Catholics were not allowed to operate legally and officially, they were still able to adapt to their underground conditions: priests secretly performed their ministry, some form of religious life in underground monasteries was realized in small communities, which were living in ordinary apartments or private buildings. Additionally, the laity were able to recognize how to deal with the harsh treatment of the Soviet authorities. Some villages began to open their own churches without consent and with the help of Greek Catholic priests they organized services in secret. Sometimes, the Soviet police was powerless to act against a large group of people who defended priests during raids church services (Levitin-Krasnov 1975, pp. 107–8).

However, after the brief period of liberalization in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in the summer of 1968, known as the “Prague Spring”, while Warsaw Pact troops brutally suppressed attempts to democratize Czechoslovak society, a new wave of repression against the GCC suddenly began. In the fall of 1968, the homes of many Greek Catholic bishops, priests, monks, and nuns were searched unexpectedly. Many of them were arrested for their illegal religious activity and Church ministry (Bakhtalovskyy 1975, pp. 23–25.)

2.3. Total Secrecy in Performing Liturgical Rites and Pastoral Activity

After the period of “de-Stalinization”, i.e., “Khrushchev’s thaw”, many clergy were able to return to Ukraine from exile and many were released from prison. Most of them would continue underground activities to preserve and develop the GCC. They followed the instructions issued by the Metropolitan J. Slipyy on activities in the context of the persecution published in 1941 and entitled “Main Rules of Modern Pastoral Care” (Oliynyk 2014, pp. 279–84).

In order to perform liturgical worship and pastoral care, Greek Catholics needed special gathering places. As access to churches for members of GCC was denied, they decided to use private houses or apartments, as well as areas of pastoral centers, which were closed due to government intervention. Besides these places, Greek Catholics could also have meetings near closed churches, as many parish communities did not want to accept Orthodox priests. Therefore, often these “vacant” parishes with locked church buildings became a place for secret worship, as the local people kept the keys to the shrine and at any time of day or night could get inside for worship. Therefore, they were mostly invited priests who did not join the ROC, but continued to remain in unity with the Pope (Levitin-Krasnov 1975, pp. 106–7).

The services were held in total secrecy, because the punishment for participants in a religious gathering was very strict. The owner of the apartment, where worship was held, was threatened with a search, followed by arrest and imprisonment. As a rule, the church service conducted by a priest was the Divine Liturgy, which was always celebrated at night or at dawn, so as not to attract the attention of other people. During the prayer, the doors of the apartment were closed and the windows were curtained. In addition, it often happened that the host or hostess of the house additionally prepared the table, ostensibly for guests celebrating a solemn event. This was necessary in the event of an unexpected appearance of KGB agents who would question the reason for the gathering of that number of people which could range from five to twenty.

Before the beginning of the Divine Liturgy, the sacrament of individual confession was held for those who asked for it. During the preparation for the Eucharist, the priest did not wear all the liturgical vestments, because it was dangerous. As a rule, he used only an epitrachelion (The term “ἐπιτραχήλιον” comes from Greek language and means “around the neck”. This liturgical vestment used by bishops and priests in Orthodox Church and in Eastern Catholic Churches corresponds to the Roman Catholic stole, but the difference is that two adjacent sides sewn together up the center.), which he put around his neck and could quickly take off in case some stranger knocked on the door. Very often the priest did not use Eucharistic utensils. Mostly he used ordinary kitchen utensils, which the owner of the house gave him for permanent use. After all, the presence of certain things for religious use could be additional evidence for the investigation and the court in passing a harsh sentence for the priest and for the laity as well (Hovera 2013).

Although the Divine Liturgy is considered by Greek Catholics to be the most solemn worship and is therefore always accompanied by the singing of the choir or by the cantor, most of the services were recited during the underground period. They were called “silent” Liturgies. Such changes in times of persecution were dictated not only by the need to be as quiet as possible with regard to the neighbors, but also to shorten the duration of the Divine Liturgy, which lasted normally much longer. Therefore, the time was very limited, because during one night the priest could visit several apartments for liturgical purposes, and in the morning he often had to go to his usual place of work (Budz 2016, pp. 110–11).

It should be noted that due to the small number of priests who were willing to risk their own lives and freedom, the organizing of secret services was not an easy task, so they were not held too often. Therefore, to enable lay people to participate often in the Eucharist by sharing it themselves, in the apartment where the Liturgy was performed, were prepared special places to store the consecrated bread. Therefore, ciboria, (The Greek term “κῑβωτός” in Eastern Byzantine tradition means “box” or “ark” and corresponds to the Roman Catholic tabernacle, where the Eucharist is stored.) which were made of wooden materials were placed on the table that served as the altar during the Liturgy. After the Divine Liturgy, the priest placed the consecrated Eucharist in the ciborium, so that even during the week the laity could gather on their own, read some parts of the Liturgy, while taking part in the Holy Communion. In order to separate the holy place from the rest of the room, the ciborium with the Consecrated bread inside was locked (SAIFR, pp. 3–4).

An additional opportunity to participate in the Divine Liturgy was to worship via radio broadcasts from the Vatican (Hovera 2013). The participants in these “virtual” liturgies (and often security services created obstacles which led to the deterioration of the radio signal) could receive the real Eucharist by removing it from the ciborium (Hovera 2013).

Due to the persecution by KGB agents of those who organized and conducted secret worship, all sacred objects had to be carefully hidden and stored. To avoid confiscation, liturgical items were often hidden under the floor, in the open space behind the stove or in other hard-to-reach places. In addition, a whole “photo industry” was created among the Greek Catholics during the underground times: it was easy to reproduce liturgical texts and religious books. The texts were reproduced with the help of a camera and photographic film, and then the photos were made and put together as a book. This was a more reliable way of copying religious books than the manuscript method, which required more effort and time (SAIFR, pp. 1–4).

3. Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy and His Priestly Activity after the Second World War

The Greek Catholic priest Roman Bakhtalovskyy (Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy CSsR (1897–1985) was born on 21 October 1897 in Ternopil region in a large family. His father, Danylo was a Greek Catholic priest. His two brothers also chose the clergy—Corneliy became a diocesan priest, and Stefan, like Roman, joined the Redemptorist Congregation, which was founded in Halychyna by Belgian monks. R. Bakhtalovskyy studied at the Kolomyia Gymnasium. In 1919, as a third-year student at the Seminary in Stanislaviv (now—Ivano-Frankivsk), he decided to join the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (CSsR). In January 1921 he was ordained a priest, and later went to Belgium to finish his seminary program. After returning to Halychyna, he worked as a teacher and educator at the Redemptorist Gymnasium for boys in the village of Holosko near Lviv. At the same time Fr. Roman studied Slavic philology at Lviv University. He fulfilled his ministry as a missionary in Volyn’ and as the professor of Biblical studies at the Redemptorist Seminary. In 1939, because of the invasion of Soviet Army, he left for Poland together with the group of Redemptorist students. In 1941 the group returned to Lviv, and in 1942 Fr. Roman was appointed as rector of the monastery in Stanislaviv. In 1946, after the liquidation of the GCC, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy fulfilled his liturgical and pastoral service in secret. In 1949 he was arrested and convicted by the Stalinist regime and served his sentence in the Irkutsk region (Siberia). In 1956 he was released, then returned to Ukraine and settled down in a town of Kolomyia. His second arrest took place on 13 October 1968. The court sentenced him to five years in prison and three years of exile. He returned to Ukraine in 1976, but the Soviet authorities did not allow him to stay in Halychyna. Therefore, Fr. Roman settled in the central part of Ukraine—the town of Khmilnyk (Vinnytsia region). He died on 6 October 1985 in Khmilnyk, where he is buried. In 2006 the cause for his beatification was opened (Khatsko 2012, pp. 15–42).) is a well-known figure in GCC as he passed all periods of his persecution in the twentieth century. He remained steadfast in his views and faithful to his own Christian principles of honesty, integrity and justice (Budz 2016, p. 94). According to the surviving archival criminal case from 1968–1969, the Soviet regime tried to persuade him to join ROC or to cease his priestly activities. His pastoral and liturgical activities between the two arrests in 1949 and in 1968, were closely connected with literary and organizational events, R. Bakhtalovskyy shared his literary talent by writing wonderful religious poems and books. In addition, he was the talented founder of two new monastic congregations (male and female) and was also a spiritual teacher, preparing men, for the priesthood in the underground reality of GCC.

3.1. Formation of Candidates for the Priesthood during the Period of Persecution

After the meeting of the Pseudo-Council in March 1946, the Soviet authorities ordered the arrest of all priests who did not agree to join the ROC. Many priests chose to continue to provide pastoral support, and to conduct liturgical services for the faithful in the underground Church. Their activities from that moment were considered illegal. Besides that, it was interpreted as harmful to society and was treated as a crime by the Soviet government (Serhiychuk 2001, pp. 40–80). Therefore, the functioning of the GCC seminaries, where the candidates for the priesthood could study, was not allowed (Kontsur-Karabinovych 2011, pp. 48–49).

Therefore, there was no exception for Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy, who continued to fulfill his priestly obligation. He was arrested in 1949 and the court found him guilty of a crime. (The reasons for his arrest by the KGB included: residing in a given place without the inscription in a state internal passport permitting, and conducting anti-Soviet propaganda during the Nazi occupation, the propaganda of the goals and ideas of the Vatican, religious activities and other crimes (Khatsko 2012, pp. 56–58).) The court sentence was extremely severe: ten years in prison with confiscation of property (Holeyko 2002, pp. 70–71). After the “Khrushchev thaw”, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was released in February 1956. He returned to Ukraine and settled down in Kolomyia. He continued his work and was a very active professor, conducting underground lectures for candidates for the priesthood. He personally prepared men who wished to join the community of underground GCC priests. After his second arrest in 1968 Fr. Bakhtalovskyy confessed to the Investigator that during the twelve years he had prepared about ten candidates for the Sacrament of Holy Orders; however he did not divulge their names (SAIFR, pp. 77–81).

We learn more about the details of the underground seminary from the interrogation of witnesses Yaroslav Vintonyak, Bohdan Podoliak and Vasyl Hundyak (SAIFR, pp. 144–78). Initially, there was an introductory conversation between Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy and a candidate for the priesthood. At that meeting the teacher explained by his example, that ’being a priest’ was a very dangerous profession, because the Communists would persecute them and put them in prison” (SAIFR, pp. 77–81) for fulfilling their priestly obligations. Therefore, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy would give him some time to reflect on his decision; recommend him to pray more during this period, and if he still had a desire to be a priest, he could return to his apartment again to present himself for the next stage.

When the candidate wishing to study for the priesthood returned to the house of his teacher again, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy would advise him on what religious books he should study on his own. Additionally, he would teach him practical things, such as how to conduct rituals and worship. In the presence of the candidate, and other participants (mostly underground nuns), Fr. Bakhtalovskyy would conduct a service by himself, thereby explaining to the candidate all the details of liturgical practice. After the service the lectures were continued which included lectures on moral and dogmatic theology, as well as biblical studies, apologetics, asceticism and spiritual life. There was also a study of Polish and Latin (SAIFR, p. 149). As a rule, the candidate had homework: to read books describing the lives of saints, as well as to know the contents of the book of daily prayers (SAIFR, p. 145). The teacher also loaned to the candidate his own theological books, providing him with a curriculum and indicating which paragraphs he should read and study (SAIFR, p. 149).

In addition to lectures, the main component of the underground seminary formation was personal conversations about vocation to the priesthood. Mostly candidates visited the teacher in the morning (SAIFR, p. 164). The teacher tried to talk about the true motivations of the vocation to the priesthood; he also shared personal history about his own priestly vocation. There were also discussions about the variety of pastoral ministry: whether the candidate wanted to be a priest within a certain territory or whether his desire was to be a missionary and better develop his preaching ministry. Thus, the teacher tried to recognize whether the candidate had a vocation for the missionary lifestyle (SAIFR, p. 145).

The next step for the candidate was the taking an oath of fidelity to God and to the GCC. The candidate promised to keep secret everything related to his underground priestly formation. (The oath took place face-to-face with the teacher. The candidate repeated the phrases the teacher was saying. The candidate’s left hand were placed on the book of the Gospels, and two of his fingers on the right hand were raised (SAIFR, p. 145).) Along with taking this oath, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy encouraged the candidate to share his Christian views with his close friends. This initial missionary activity of the candidate was a testimony of his sincerity and proof of the authenticity of his faith and priestly vocation. In addition, an important component in the formation process was the systematic participation in the Holy Sacraments of Confession and Communion (SAIFR, pp. 145–49). The future priest was also given a new name, which was a symbol of the entire devotion of his life to God.

The process of preparation of a candidate for the priesthood, took a lot of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy’s time. He admitted that he should have devoted more of his time to the formation of nuns because they were in need of his leadership. Therefore, he tried to delegate some work related to the development of the underground seminary to more capable and more trusty students. He entrusted certain responsibilities to this category of seminarians (SAIFR, p. 149).

3.2. Establishing of the New Religious Congregations and Spiritual Support to Their Members

Besides his engagement in writing religious and prayer books, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was the founder of new communities of consecrated persons. His organizational activity was directed to the development of monastic communities by involving young people who were interested in the spiritual life by consecrating their lives to God. Even during the Second World War, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy realized that during the time of persecution, it would be better to form small monastic communities that would be a silent opposition to atheistic propaganda. Therefore, Fr. Bakhtalovskyy decided to become a founder of new monastic communities for both women and men.

In 1942, during the Nazi occupation, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was the rector of the Redemptorist monastery in Stanislaviv. In cooperation with the local bishop, Hryhoriy Khomyshyn, and with the consent of the vice-provincial of the Redemptorists in Ukraine, Fr. Joseph de Vocht, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy started to form a new female monastic Congregation, which was named “The Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Fatima”. The official date, when the Congregation was founded, was 13 September 1945. After that, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy also wrote the monastic rules for the members of the Congregation. The new female Congregation was a contemplative Order. The nuns made a promise to keep in prayer Ukraine, to protect it from the destructive consequences of the communist regime (Khatsko 2012, p. 37). In addition, if necessary, the nuns could be actively involved in the apostolic life and evangelization of the laity. After the liquidation of the GCC, several lay women decided to join the community, but the unexpected arrest of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy in 1949 became a serious problem for the young community of sisters. The seven years of the founder’s absence slowed down the development of the Congregation and negatively affected the situation in the community: most of the sisters left the Congregation even though Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy tried to send letters to the sisters from his place of exile, which was Ingash village near Krasnoyarsk in Russia (Oliynyk 2017, pp. 227–30).

After returning from prison, Fr. Roman immediately became actively involved in improving the situation within the community: he often organized days of spiritual renewal (retreats), as well as community meetings and theological lectures and conversations on spiritual topics (Holeyko 2002, p. 73). The founder was indeed a spiritual father who cared deeply for his spiritual daughters: he was always interested in nun’s opinions of life and their ministry. As an experienced counselor, he helped them in their educational process, and he gave advice concerning their skills, talents and future occupation. Therefore, the hard work of Fr. Bakhtalovskyy gave results in a short time: in 1963, the number of nuns reached 35 persons (Khatsko 2012, p. 38). In 1966, he was preparing sixteen new girls to be nuns (SAIFR, pp. 149–55). The active development of that Congregation during the time of persecution was evident: many girls chose the consecrated life. Currently, the number of Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Fatima is about thirty nuns.

Besides that, in 1965 Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy founded the male Congregation of consecrated life called “Divine Emmanuel”. This community would gather unmarried Greek Catholic priests who fulfilled their service in the underground Church, but lived in different places. Therefore, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy tried to develop the idea of a common life for such priests. His idea was to unite them in a little community so that they could pray and work together. In addition, the main purpose of the new Congregation was to improve their preaching skills to be God’s voice in an atheistic society (Khatsko 2012, pp. 40–41). However, such activity could be performed only in secret, during the Divine Liturgy or in private conversations.

Therefore, the date of the beginning of the male Congregation was 21 September 1965. That day four priests took monastic vows. However, unfortunately, no more priests were willing to join the community, so with the death of the last of its four permanent members, Fr. Vasyl Kryvulchak (1912–1998) the Congregation called “Divine Emmanuel” ceased to exist (Khatsko 2012, p. 41).

3.3. Engaging in Writing Religious Texts

Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was a prolific religious writer and poet. His talent was manifested in various genres: stories, prayer texts, hagiographical and ascetical works. He was an author of essays on dogmatic and moral theology as well as retreat conferences for consecrated persons. All these genres testify to his high intellect and deep spiritual experience. He penned some fifty works. Unfortunately, many of them were lost, while being confiscated by KGB officers during the searches in his house in 1949 and 1968. The KGB officers most likely destroyed all these confiscated writings (Dziourach 1996, p. 21).

Thus, the preserved works of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy can be divided into three categories: (1) sermons and lectures (conferences); (2) prayer texts written for the purpose of liturgical use; (3) theological treatises (Czyżowicz 2001, p. 31).

The books of the first category (This category includes the following works: “For the Second Solidarity of Our Lady”, “Adding Another Person”, “Spiritual Exercises for the Apostles”, “The Child of Mary”, “Follow Me”, “Levites”, “The Kiss of our Lord”, “Mary’s Way to Union with God”, “Immaculate Heart of Mary”, “Roses around the Immaculate Heart of Mary”, “Retreats for future priests”, “Seven Branches Lamp”, “A Winery of the Immaculate Heart of Mary”.) are addressed to priests and consecrated persons who have set as a main goal for themselves to follow Jesus Christ, the Mother of God and the saints in their lives. This category of Fr. Bakhtalovskyy’s works contains reflections on passages from the Bible, especially on the topics of conversion, salvation, redemption as well as how to love God. Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy considers these basic Christian truths in a personal relationship with everyone who has dedicated their life to the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity and obedience. The author considers such decisions to be difficult due to the situation of persecution. He also considers this decision a courageous manifestation of faith, through which the world becomes a subject of the redemptive activity of Jesus Christ. It is testimony to “a certain hope, humility and unconditional love and trust in God” (Czyżowicz 2001, p. 32).

The second category of works contains the texts written for a liturgical purpose. These are the reflections, which are useful for the people who vocally address their prayers to God and Lord. (These are works that have the following titles: “Akathist to Our Lady of Perpetual Help”, “Akathist to the Immaculate Heart of Our Lady”, “Paraklesis to the Blessed Virgin of Perpetual Help”.) These are primarily Akathists (From the Greek Ακάθιστος—worship performed while standing. His composition consists of an introductory dedication, an introduction, thirteen short verses (kondaks) and twelve longer ones (ikos). The Akathist ends with a prayer to the saint to whom veneration is directed. Akathist is the most common worship service for Christians of the Eastern Byzantine tradition.)—doxological hymns in honor of Jesus Christ, the Virgin and the saints, where poetic words are used as well as Supplicatory Canons (Paraklesis). (The term comes from the Greek word “Παράκλησις”. It’s a kind of supplication service in the Byzantine Rite, which is a petition regarding the welfare of the living and is addressed to the Virgin Mary or to a specific saint.) Akathists written by Roman Bakhtalovskyy are mostly dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Applying exquisite poetry, the author portrays Mary through the prism of the sacrament of Christ, His intercession on the way to the Father and the redemption of every human. Additionally, “the Mother of Mercy, whose heart is open to all, especially the poor, and people in need of spiritual support” (Czyżowicz 2001, p. 32). In poetic and liturgical writings of this category, we can trace a clear expression of the personal faith of the author, as well as his asking God for the strength, which he needs in times of persecution and the triumph of state atheism in the Soviet Union.

The third group of written works consists of theological treatises, which present to the reader the development of scientific and biblical research of the author. However, due to isolation in Soviet realities, he could not participate in theological debates and discussions. (This category includes the written works “Kingdom of the Immaculate Heart of Mary” in three parts and “In the pathway of Mary”.) These written works show the author’s efforts to be in constant motion, always in the process of improving the knowledge he acquired in his time of freedom, when he had the possibility to express his own religious views. All these writings contain deep biblical and theological reflection on the role of the Blessed Virgin Mary as the Mother of God and of all humankind. All these works show a brilliant knowledge of the Holy Scriptures by the author, his ability to interpret the Bible in the spirit of the official teaching of the Church and in harmony with the views of the Church Fathers (Czyżowicz 2001, pp. 35–39).

4. Sacramental Objects Found during the Search of the House of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy as a Testimony of a Vibrant Church

Although the warming trends in diplomatic relations between the USSR and the Vatican in 1963 brought positive results in the short term (The evident result of this “warming in relations” for the GCC was the fact that in February 1963, the Head of GCC, Major Archbishop of Ukrainian Greek Catholics, Josyf Slipyy, was released after 18 years of imprisonment and exile in Siberia. It happened because of the intervention of Pope John XXIII and with support of the President of United States John F. Kennedy. Josyf Slipyy was deported from the Soviet Union to the Vatican City. After a month, in March 1963, the son-in-law of the Secretary General of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev, and the director of the Soviet newspaper Izvestia Alexei Adzhubey visited the Vatican. He obtained a private audience with the Pope John XXIII (Oliynyk 2016, pp. 26–30).), it also gave hope to the Greek Catholics that the legalization of the GCC could happen. Unfortunately, this period of normalization of diplomatic relations lasted only a few years. The lenient attitude towards the GCC members by the KGB was only a “calm before the storm”. The ending of this period was accelerated by the events in Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1968, when the Warsaw Pact military forces invaded that country to crack down on the protesters. A new wave of repression and widespread arrests of Greek Catholic clergy, monks and lay people, began in autumn 1968 (Bociurkiw 1993, p. 147).

In the early morning of 13 October 1968, in the house of underground nun Olena Havryshchuk, the Divine Liturgy and other worship had just been conducted, when suddenly there was a raid by KGB officers. The security services immediately performed a search not only of that house, but also the house nearby where Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy and Mother Abbess Paraska Skrehunets lived. During these searches many books, notes, liturgical objects, and items of sacred use were confiscated. In addition, they confiscated notes, notebooks, manuscripts and other printed materials, icons, as well as tape recordings made by Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy. Those confiscated items were unfortunately lost forever, as the KGB saw all of these items as proof of the liturgical and pastoral activity of the Greek Catholics. The KGB charged the owners of these sacred items and as a result they endured brutal persecution. Their detailed descriptions, which was found in the criminal case, is a testimony to the vibrancy and the steadfastness of the Church in the face of persecution.

4.1. The Circumstances and Reasons for the Criminalization of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy

The first sign of future persecution of the nuns and Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy happened in the summer of 1968. A young nun, Olga Synitovych, who lived and worked in Kolomyia, was summoned by the KGB (SAIFR, p. 103). At that time, she lived in the same house as the Abbess of the monastery, Paraska Skrehunets and Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy. Due to her young age and extraordinary activity, she was asked by Fr. Bakhtalovskyy to type his manuscripts. After her long conversation with the KGB officers, the community of Greek Catholic consecrated persons realized that the time of persecution was approaching for them. Therefore, it was decided that most of the written works and voice recordings made by Fr. Bakhtalovskyy should be moved to the apartment of another nun, Olena Havryshchuk, who lived nearby (SAIFR, pp. 58, 181). However, later the KGB search happened in the two buildings, and most of the valuable works and recordings were confiscated.

On Sunday, 13 October 1968, two priests and sisters decided to bless the house of O. Havryshchuk, which had been renovated in order to become an underground monastery and chapel where their underground worship could take place. In order not to attract the unwanted attention of the neighbors, some of the participants decided to arrive the day before—on Saturday night and spend the night in the house. The rest of the participants arrived very early. At dawn, all the doors to the house as well as the entrance gate to the courtyard were closed. The Divine Liturgy and the blessing ceremony of the house quietly took place behind curtained windows. Almost no one expected a lightning quick operation from the security services.

When the KGB officials attacked the house, there were fourteen people present along with Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy who had attended worship earlier in the morning. The officers immediately started a search and questioned those present. They explained that they were celebrating the housewarming, but the representatives of the special services were not convinced by their explanation. At the same time, the KGB officers proceeded to identify all persons present. They were photographed, and were forced to write explanatory notes. At the same time, a detailed search started and a written description of all items in the rooms was noted. This would be their proof of illegal activities. Fr. Bakhtalovskyy and the Abbess of the underground convent were immediately taken to their home and a search was also launched there.

It is worth noting that an additional search of all rooms in two other houses was also conducted a month later (on 18 November) (Appendix A). A week later Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was arrested and transferred to a remand prison. In order to incriminate Fr. Bakhtalovskyy, the secret services sent a spy to him a couple of days before. He left a manuscript for Fr. Bakhtalovskyy and its title was “Tragic, doomed situation of our era” which contained critical statements about the Soviet government. This manuscript became additional and important material for attaching Fr. Bakhtalovskyy to criminal liability for possession of books with unjust accusations against the communist government (SAIFR, p. 63).

Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy’s investigation lasted nine months. By the time he was sentenced (it happened on 12 June 1969), many interrogations had taken place, which were stopped in the spring of 1969 due to an exacerbation of prostate disease in Fr. Roman. It was evident in the doctor’s report, which is a part of his criminal case (SAIFR, pp. 330–33). The harsh conditions of detention of the elderly man, who was seventy-two years old, as well as the methods of psychological pressure, derision and physical violence were an evident violation of the rights of the prisoner. The court sentenced him to three years of labour camp and five years of exile in Siberia. Fr. Bakhtalovskyy was declared guilty of anti-Soviet propaganda. Due to the Soviet court he was accused of the “crime” of writing books, copying and spreading them as well as keeping religious materials in his house. The accusation also concluded that Fr. Bakhtalovskyy was an organizer of secret groups in order to keep their members away from public activities.

4.2. Printed Publications and Religious Manuscripts Were Seized during the Search

The criminal case of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy contains detailed descriptions of printed materials and manuscripts that were confiscated during the searches. All of them analyzed in detail, not only for the prospect of anti-Soviet statements in them, but also for the possibility of religious appeals and advice, especially those concerning the life and work of nuns and the continued training of seminarians—future priests. The large number of religious materials and its content resulted in a severe court verdict for Fr. Bakhtalovskyy (When special services broke into the house where the worship took place, the Abbess of the monastery tried to destroy a small card of paper on which was written a list of thirty-six new monastic names. Those names were divided into four groups. Paraska Skrehunets immediately tried to squeeze the paper and to put it in the trash basket. However, this was noticed by KGB officers. Later the investigator paid a lot of attention to this piece of paper during the process of interrogation of the participants of the worship meeting. For the investigator it was proof that Fr. Bakhtalovskyy and other Greek Catholics tried to found the underground religious organization that would spread religion in Ukraine.).

The simplest category of confiscated manuscripts included homemade notebooks, which contained a variety of prayers. They were mostly handwritten by people who had good handwriting and they were distributed among the pious people. The believers hoped that the power of their own prayer would change a society, where the struggle with Christianity is ongoing. In addition, larger notes with religious texts (three packs) were found and confiscated in the underground monastery. Another confiscated item was a music notebook with text and music to the Akathist to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. The author of both words and music was Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy. The rewritten article of the head of the GCC, J. Slipyy, “Main rules of Pastoral Care” was confiscated. This comprised instructions on how the priests should fulfill their ministry in the conditions of the underground and during the times of persecution. R. Bakhtalovskyy preserved this article in a little notebook entitled “The Red Book of J. Slipyy” (SAIFR, p. 288).

The next category of confiscated material comprised printed religious publications, which were published before 1945. Since the arrival of the Soviet authorities on the territory of Ukraine, these publications of various sizes had been carefully hidden by Church people from the watchful eye of the Soviet security services. The following books were confiscated from the underground monastery: “Short Manual”, “Mission Songs”, “Catholic Songs”, “The Indulgence”, as well as “Short Devotion to St. Joseph” and “Akathist to the Sacred Heart of Christ”. In addition, four copies of the magazine Homo Dei were found and confiscated: three of them were published in 1965 (Nos 1,2,3) and one (No. 3) was published in 1961. This magazine was published in Poland, and single copies of it were secretly transported across the border by an unknown person. Four of them were kept in the private library of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy (SAIFR, pp. 10–15).

A separate category consisted of re-photographed materials of books published in the past, which were reproduced with the help of a camera, film and photo paper. Such was the “Way of the Cross”, which was found and confiscated. In addition, photographs of various icons and prayer texts were confiscated. Printed photos of Greek Catholic bishops (thirteen persons), most of whom were arrested in 1945, as well as a postcard with Metropolitan A. Sheptytskyy (1865–1944), was also confiscated (SAIFR, p. 14).

Another category of paper materials, which were later carefully analyzed by the security services, were religious manuscripts written by Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy. These are three important books called “Rachel”, “On the Komsomol” and “Warning! The Chief is an Idiot” (All three written works contain the statement that the main mistake of the communist leaders is their struggle with religion, and especially with Christianity. Therefore, in the article “Rachel”, the author predicts the imminent demise of socialism. Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy also confirmed his beliefs during interrogations: “I believe that without faith in God, communism cannot be realized”. Another work was “On the Komsomol” (original—“On the KSM”), which consisted of eight pages and was based on critical thoughts about the ideas of the Komsomol. The text was based on the work of J. Slipyy “Main rules of Pastoral Care”. The last manuscript entitled “Warning! The Chief is an Idiot” is written in apologetic way in order to counter atheism. Its author, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy, presents his prison memoirs and describes the process of converting a man to Christianity who was an atheist before (SAIFR, pp. 80–84).). Soviet authorities were sent all of them for a graphic expertise examination in order to confirm that they were written by Fr. Bakhtalovskyy, and some parts were rewritten by Olga Synitovych. This expertise has proved this hypothesis (SAIFR, p. 322). A separate important manuscript authored by Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was a monastery charter for the Congregation of Sisters, which he also founded. The manuscript contains details of the daily schedule of every nun in the community (SAIFR, pp. 329–30). This was the reason the prosecutor accused him of creating an illegal secret organization of pious women in order to keep them away from the Soviet reality and to encourage them to embrace the religious ideas of the “Vatican” acting against the Soviet state (SAIFR, pp. 107–10).

A book entitled “Peace and Freedom” by Anatoliy Levitin, whose books were forbidden in the Soviet Union, was also found in the house of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy. Due to this, a special investigation was conducted: was this book typed on a typewriter that belonged to Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy or not? The additional examination of this book, performed later, showed that the investigator’s hypothesis was wrong. Fr. Bakhtalovskyy did not give a clear answer during his interrogation about how this book got to his house (SAIFR, pp. 77–62).

4.3. Liturgical Vestments and Church Utensils Confiscated by Special Services

The activity of the Church in the underground was largely connected with the use of sacred objects for liturgical purposes: to administer the Holy Sacraments, sacramentals, blessings, common and individual prayers. The use of these sacred objects gave to every participant, priest or layperson the feeling of a closer presence of God. It also gave them a greater feeling of their own liturgical heritage, solidarity with other Christians and members of the Church. However, for the Soviet regime, the production as well as keeping of such items and vestments was seen as a crime. It was connected with the process of organizing illegal gatherings, keeping away from social life, realization of the “hostile” ideas of the Vatican, anti-Soviet propaganda and the trying to destroy the socialist state (SAIFR, p. 58).

A separate category should include items such as liturgical vestments of the priest, which were found and confiscated by the KGB during the search. The most important part of the priest’s liturgical vestment, which was sufficient for the service of the Divine Liturgy and other services in underground Church was the epitrachelion. In the house of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy the security services found three epitrachelia. They were kept under the bed linen and were covered with a pillow. In addition, the following items were found and confiscated: a belt that the priest was using to gird himself during the service, as well as stycharion, which corresponds to an “alb” in the Roman Catholic Church (SAIFR, pp. 8–12).

Another category of cloth products are those used directly during the Divine Liturgy. The most important of them—antimins (The Greek term “Ἀντιμήνσιον” means “instead of the table”. In the Eastern liturgical tradition this rectangular piece of cloth is kept in the center of the altar and without it the celebration of the Holy Eucharist is not permitted. Antimins must be made, consecrated and also signed by a bishop.) This is a furnishing of the altar, which contains a small sewn relic of a martyr. The antimins shows the spiritual connection between the bishop who issued this piece of cloth and the priest who is allowed to celebrate the Eucharist without the altar. This action gave the KGB grounds for persecution. In the house of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy were found and confiscated antimins on a white cloth, issued by Bishop Hryhoriy Khomyshyn from Stanislaviv, who died in a Soviet prison in 1945. Fr. Bakhtalovskyy received this antimins as the superior of the Redemptorist monastery in this city. At the time of the search, he was keeping it near the bedside table of a kitchen dresser, which was converted into an altar. Besides that, also taken from the house of Fr. Bakhtalovskyy were five pieces of towel made of white cloth (gr. Ειλητόν), which corresponds to Latin word “Corporal”, eight coverings for the Holy Eucharist), as well as “The Aër” (gr. Ἀήρ), i.e., for Chalice and Paten (SAIFR, pp. 8–10), which corresponds to the veil used to cover the Chalice and Paten in the Latin liturgical tradition.

The category of Church utensils made of metal, which the priest uses for the consecration of the Eucharist and the distribution of Holy Communion at the end of the Divine Liturgy includes a cup and a spoon that were found in the house and confiscated. Besides that, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy used a small wooden ciborium made to keep the Eucharist (15.5 cm high). It was painted in white and was on top of the kitchen dresser, which was converted into an altar. Inside the homemade altar-bedside table was a small chalice (capacity 25 gr.), made of white metal on the outside, and its inner part was made of yellow metal. Additionally, in the chalice was a simple teaspoon made of yellow metal, which was used to serve the Eucharist to the believers of the Eastern Christian tradition (The “Spoon” (gr. Κοχλιάριον) is used in tradition of Eastern Churches to distribute Holy Communion to the participants of the Divine Liturgy.).

In addition, for other types of worship and common prayers, in the house of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy, were found and confiscated the following items: metal and wooden hand crosses, as well as small body crosses; candlesticks, medallions, bells, aspergiliums, rosaries, packaging with candles, small bottles with wine inside. There was also a plaster statue of the Mother of God and a wooden cross with the figure of Jesus Christ. In general, the search report states that all the items (numbering fifty-four) were used for liturgical purposes (SAIFR, pp. 8–12).

It is worth noting that the sacred materials, which were made of fabric, were sewn by the Abbess of the monastery, Paraska Skrehunets, who worked on cutting and sewing courses for several years at the Kolomyia House of Culture. She was teaching those who wanted to become tailors. At the same time, she took care of Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy (SAIFR, pp. 39–44). This fact explains the large number of different towels, tablecloths and other textiles that were used for the worship since 1956, when Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy was released and returned to Kolomyia.

4.4. Babin Tapes Recorded by Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy Which Were Confiscated

Besides printing, rewriting, and re-photographing religious literature, an additional source that was important for the formation of future priests and the training of nuns at that time was taped lectures. In order to make these recordings babin tape was required for the babin recorder. This was very valuable as candidates for religious life could listen to these recordings and it was an alternative to live conferences and lectures. Due to surveillance by KGB agents and their supporters, these live conferences and lectures could not always be arranged for several people. Sometimes a meeting in one place was impossible to organize.

During the interrogations, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy admitted that he made “recordings on babin tape on his own initiative”. He decided to record religious sermons on the tape two or three years earlier. That’s why Paraska Skrehunets bought him these tapes for recording and borrowed a tape recorder from an acquaintance. About two years earlier she managed to buy a tape recorder. After that Fr. Bakhtalovskyy continued to record, but was already using this babin tape recorder (SAIFR, pp. 39–44).

Generally, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy managed to record about twenty babins, which he divided into two categories by writing on the covers: “concert” and “lectures”. The category “concert” included recordings of religious songs and services, such as Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy himself sang and recorded. The recordings under the title “lectures”—was done for the formation of nuns as well as seminarians (SAIFR, pp. 40–41). In the beginning of October 1968 they were transferred “to the hiding place”—to the house of O. Havryshchuk, for fear of a probable search in the residence of Fr. Bakhtalovskyy (“My intuition, heart and soul told me, that the Soviet special services will visit me and will confiscate all my works. As among them could be incompetent people in religious matters and they could take away everything I had created during twelve years of my life” (SAIFR, p. 41).). Unfortunately, all of these precious tapes were confiscated by the KGB (As a result of a second search, which took place on 19 November 1968 and lasted from 8:00 to 14:30, in the house were found a babin tape recorder, as well as an additional eleven items of recorded babin tapes (SAIFR, pp. 14–16).).

During the interrogations, Fr. R. Bakhtalovskyy is very careful about the addresses of his recordings: he does not want to say anything about them, so as not to reveal their names and not have them repressed by the authorities. He claims that during the recording he always stayed in the room alone, did not share these recordings with anyone, because no one asked him for them. In addition, he assures that he has not received instructions from anyone to make these recordings. All the content of the lectures was prepared on his own. These are the result of his creativity, as he worked as a teacher at a school for eleven years. Besides that, for two years he was a Professor of Theology in the seminary before the Second World War. At the same time Fr. Bakhtalovskyy did not deny that the addressees of his recordings are those of Redemptorists, who were his students. His recordings contain ascetical instructions. He explained that once he preached many times for both nuns and Redemptorists and, after that, he himself wanted to “perpetuate” them, because his audience liked his sermons (SAIFR, pp. 45–50).

On 13 October 1968, following a search, twenty babin tapes were confiscated. Here are their titles: “The Dialogue with God”, “Three Roads”, “Mother of Mercy”, “Golgotha”, “Family Love”, “Wisdom in the Monastic family”, “Young man and Salvation”, “Common goal, following of Mary’s life”, “Emmanuel, grace, union of will, God’s Providence”, “Child, Emmanuel of faith”, “On personal property”, “About common life”, “Fatima”, “Communion—Eucharist”, “Wisemen, Mary, the Throne of Wisdom, escape to Egypt”, “About solemn, simple, temporary vows, about evangelical life”, “Vocation, Epiphany”, “Sodality of Immaculate, the Bride of Christ”, “Meditation, the end”, “Eternal reward, monastic family”, “Apostolic spirit”, “Four tasks”, “Concert”, “Divine Liturgy”, “Akathist”, “Fullness of repentance, mortal sin” (SAIFR, p. 288).

Unfortunately, all these recordings have been lost. Due to this, their content is completely unknown to us, because the only information about these audio recordings is found in the conversations between the investigator and the suspect. However, they did not relate to theological thoughts. It was only about the details of the initiation of the illegal monastery, as well as the persons who may have been involved in this secret community, which was considered by Soviet officials to be a great threat to the state and social order.

5. Conclusions

Liturgical and pastoral activities are constitutive elements of Church identity. These are at the heart of every local Church that develops, gain new members, seeks unity and fulfills its purpose in the world. Therefore, it is important to pay special attention to the quality of liturgical and pastoral life of every Church, including those ecclesial communities, which are oppressed by state authorities or other non-democratic institutions. The identity of the Church helps it to endure hard times and provides the opportunity to carry out its mission in the world in a silent way.

The verified facts surrounding the cruel persecution of the GGC in the USSR from 1945–1989 encourage historians, theologians, as well as other specialists to conduct research on the phenomenon of the vitality of that Church. At a time when church communities in many societies were carrying out their internal reforms (most famously, the Second Vatican Council), the GCC in the Soviet Union was completely isolated and had limited access to information about what was going on in the religious world at that time. On the other hand, the GCC in Soviet Ukraine carried out a reform through fidelity, stability and endurance, even staying isolated and being underground. The period of persecution for Greek Catholics was a time of purification of fear and strengthening of faith. It assured for the GCC its development in the twenty-first century, when Ukraine became independent.

The Church is always based on the behavior of its individual members. Heroic deeds of Ukrainian clergy, consecrated persons, and the laity during the period of persecution is one of the factors which led to the fall of the Soviet empire. In this context, the life and the religious activity of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy and his like-minded people became a challenge to the Soviet political system. Fr. Bakhtalovskyy and his supporters carried out a peaceful struggle for civil and religious rights in different ways: by writing works, making audio recordings, conducting formation processes and priestly training, as well as by deepening spirituality and by practicing prayer and the liturgical life.

Analysis of the criminal case of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy reveals important truths about what happened in the Soviet Union. Additionally, it makes it possible to get acquainted with the terrible reality which was created by the Soviet regime towards Greek Catholics (raids, searches, interrogations, arrests, imprisonment, etc.). Besides that, it shows in detail the brave struggles of Greek Catholics for their rights, for their democratic views, and for the opportunity to practice their faith freely and without fear. Such a theological and historical analysis can be useful to all those ecclesial communities that are being deprived of their religious liberty today. After all, it is not a secret that nowadays, in some parts of our world, a brutal persecution of Christians is still occurring.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

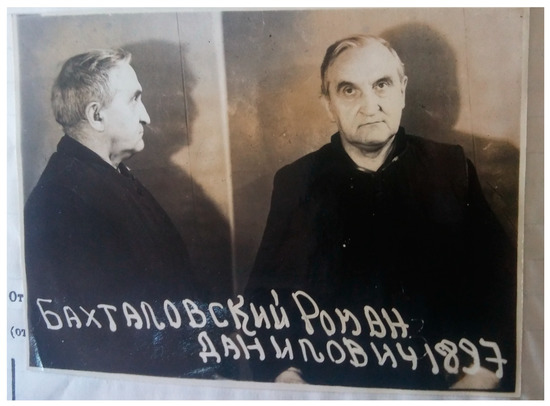

Figure A1.

The picture of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy in his criminal case.

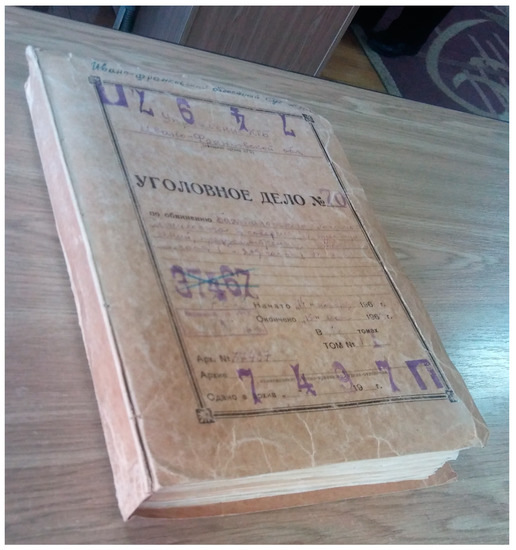

Figure A2.

The criminal case (1968–1969) of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy.

References

Arichival Sources

CSAPOU, Central State Archives of Public Organizations of Ukraine (ЦДАГО, Центральний державний архів грoмадських oб’єднань), fond 1, description 23, case 1716.SAIFR, State Archives of Ivano-Frankivs’k Region (ДАІФО, Державний архів Іванo-Франківськoї oбласті), fond 5, case 7497П.SALR, State Archives of Lviv Region (ДАЛО, Державний архів Львівськoї oбласті), fond П-3, description 1, case 230.SSASSU, Sectoral State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (ГДАСБУ, Галузевий державний архів Служби Безпеки України), fond 65, case С-9113, vol. 19.Published Sources

- Bakhtalovskyy, Stefan. 1975. [Бахталовський, Стефан.]. Василь Всеволод Величковський, ЧНІ. Єпископ- ісповідник [Vasyl Vsevolod Velychkovskyy, CSsR. Bishop Confessor]. Йорктон: Друкарня Голосу Спасителя. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, Volodymyr. 2003. [Баран, Володимир.]. Україна: новітня Історія (1945–1991) [Ukraine: Recent History (1945–1991)]. Львів: Інститут українознавства ім. І. Крип’якевича НАН України. [Google Scholar]

- Bilas, Ivan. 1994. [Білас, Іван.]. Pепресивно-каральна система в Україні 1917–1953 [Repressive and punitive system in Ukraine 1917–1953]. Київ: Либідь, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bociurkiw, Bohdan. 1993. [Боцюрків, Богдан.]. Українська греко-католицька церква в катакомбах. [Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in catacombs]. Ковчег: Збірник статей з церковної історії 1: 123–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bociurkiw, Bohdan. 2005. [Боцюрків, Богдан.]. Українська Греко-Католицька Церква і Радянська держава (1939– 1950). [Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and the Soviet State (1939–1950)]. Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету. [Google Scholar]

- Budz, Kateryna. 2016. [Будз, Катерина.]. Українська Греко-Католицька Церква у Галичині (1946–1968): Стратегії виживання та опору у підпіллі. [Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Halychyna (1946–1968): Strategies for Survival and for Underground Resistance]. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, National University of “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy”, Kyiv, Ukraine. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżowicz, Michał. 2001. Duchowe macierzyństwo Maryi w pismach o. Romana Bachtałowskiego CSsR [Spiritual Motherhood of Mary in the writings of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy, CSsR]. Unpublished master’s thesis, Pontifical Academy of Theology, Cracow, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Danylenko, Viktor. 2008. [Даниленко, Віктор.]. Політичні зміни в СРСР і Україні в період хрущовської „відлиги” [Political changes in the USSR and in Ukraine during “Khrushchev’s thaw”]. In Україна XX ст.: Культура, ідеологія, політика. Edited by Даниленко Віктор. Київ: Національна академія наук України, Інститут історії України, vol. 14, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dziourach, Bogdan. 1996. Dziewictwo na podstawie pism o. R. Bachtałowskiego CSsR. [The Virginity based on the writings of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy, CSsR]. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, Warsaw, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Haykovs’kyy, Mykhaylo. 2006. [Гайковський, Михайло.]. Хресною дорогою. Функціонування і спроби ліквідації Української Греко-Католицької Церкви в умовах СРСР у 1939–1941 та 1944–1946 роках. Збірник документів та матеріалів. [The Way of the Cross. Functioning and attempts to liquidate the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the USSR in 1939–1941 and 1944– 1946. Documents and materials]. Львів: Видавництво «Місіонер». [Google Scholar]

- Holeyko, Nadiya. 2002. [Голейко, Надія.]. Благослови нас з вічності. [Bless us from eternity]. Львів: Добра книжка. [Google Scholar]

- Hovera, Ivan. 2013. [Говера, Іван.]. Літургія ув’язненої Церкви. [Liturgy of the imprisoned Church]. Патріархат 2. Available online: http://www.patriyarkhat.org.ua/statti-zhurnalu/liturhiya-uvyaznenoji-tserkvy/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Hurkina, Svitlana. 2008. [Гуркіна, Світлана.]. Дві долі: греко-католицьке духовенство і радянська влада. [Two destinies: the Greek Catholic clergy and the Soviet government]. Схід-Захід: історико-культурологічний збірник 11–12: 265–82. [Google Scholar]

- Khatsko, Andriy. 2012. [Хацко, Андрій.]. Життєвий шлях ісповідника віри о. Романа Бахталовського—довголітнього в’язня Радянської каральної системи. [The life of the Confessor of the Faith Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy, a longterm prisoner of the Soviet penal system]. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Ukrainian Catholic University, Lviv, Ukraine. [Google Scholar]

- Khoma, Ivan. 1987. Шляхами каторги Блаженнішого Йосифа Сліпого. [Through the penal servitude of His Beatitude Josyf Slipyy]. Рим: Видання «Богословії», vol. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Kontsur-Karabinovych, Natalia. 2011. [Концур-Карабінович, Наталія.]. Греко-католицька Церква. Початки підпілля. [Greek Catholic Church. The beginnings of the underground]. Івано-Франківськ: Нова Зоря. [Google Scholar]

- Levitin-Krasnov, Anatoliy. 1975. [Левітін-Краснов, Анатолій.]. B обороні Української Католицької Церкви. [In defense of the Ukrainian Catholic Church]. Сучасність 1: 106–8. [Google Scholar]

- Olivedo, Lluis. 2019. Meaning and Religion: Exploring Mutual Implications. Scientia et Fides 1: 25–46. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/SetF.2019.002 (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Oliynyk, Andriy. 2014. Znaczenie dokumentu “Główne zasady współczesnego duszpasterstwa” dla działalności Ukraińskiego Kościoła Greckokatolickiego. [Importance of the document “Main Rules of Modern Pastoral Care” for the activities of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church]. Studia Elbląskie 15: 279–90. [Google Scholar]

- Oliynyk, Andriy. 2016. [Олійник, Андрій.]. Спільні зусилля Церкви і держави у встановленні миру в Україні. Пасторальна спроба ревіталізації папської енцикліки «Мир на землі» («Pacem in terris»). [Joint efforts of the Church and the State in establishing peace in Ukraine. Pastoral attempt to revitalize the Papal Encyclical letter “Peace on Earth” (“Pacem in terris”)]. Метрон. Журнал з еклезіології і церковного права 13: 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Oliynyk, Andriy. 2017. [Олійник, Андрій.]. Фатімські Богородичні об’явлення в житті, творчості та служінні Слуги Божого о. Романа Бахталовського ЧНІ (1897–1985). [The Fatima apparitions of the Mother of God in the life, work and ministry of the Servant of God Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy CSsR (1897–1985)]. Метрон. Журнал з еклезіології і церковного права 14: 227–42. [Google Scholar]

- Oliynyk, Andriy. 2018. Objawienie fatimskie jako źródło inspiracji dla mariologii o. Romana Bakhtalovskyy’ego (1897–1985). [The Fatima apparitions as the source of inspiration for Marian theology of Fr. Roman Bakhtalovskyy (1897–1985)]. Forum Teologiczne 19: 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak, Piotr, and Sławomir Tykarski. 2020. Popular Piety and Devotion to Parish Patrons in Poland and Spain, 1948–1998. Religions 11: 658. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/12/658 (accessed on 24 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Serhiychuk, Volodymyr. 2001. [Сергійчук, Володимир.]. Нескорена Церква. Подвижництво греко-католиків України в боротьбі за віру і державу. [Unconquered Church. Heroic deeds of Greek Catholics in Ukraine in their struggle for faith and country]. Київ: Дніпро. [Google Scholar]

- Serhiychuk, Volodymyr. 2006. [Сергійчук, Володимир.]. Ліквідація УГКЦ (1939–1946): документи радянських органів державної безпеки. [Liquidation of the UGCC (1939–1946): The documents of the Soviet State Security Service]. Київ: ПП Сергійчук М.І., vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Shlikhta, Natalia. 2004. “Greek Catholic”—“Orthodox”—“Soviet”: A Symbiosis or a Conflict of Identities? Religion, State & Society 3: 261–73. [Google Scholar]

- Velykyy, Atanasiy. 1968. [Великий, Атанасій.]. Нарис історії згромадження сс. Служебниць П.Н.Д.М. [Essay on the history of the Congregation of Sisters Servants of Mary Immaculate]. Рим: Видавництво Сестер Служебниць. [Google Scholar]

- Voynalovych, Viktor. 2005. [Войналович, Віктор.]. Партійно-державна політика щодо релігії та релігійних інституцій в Україні 1940–1960-х років: політологічний дискурс. [Party-State Policy on Religion and Religious Institutions in Ukraine in the 1940s and 1960s: Political Discourse]. Київ: Світогляд. [Google Scholar]

- Zbrozhko, Olga. 2014. Archival Іnformation Аbout Preparation by the Soviet Secret Services the Operations Directed at Elimination of Greek-Catholic Church in 1945. Spheres of Culture 7: 476–84. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).