Popular Piety and Devotion to Parish Patrons in Poland and Spain, 1948–98

Abstract

1. The Place and Significance of Popular Piety in the Liturgy of the Catholic Church

2. The Essence of the Parish Indulgence and the Forms of Its Implementation

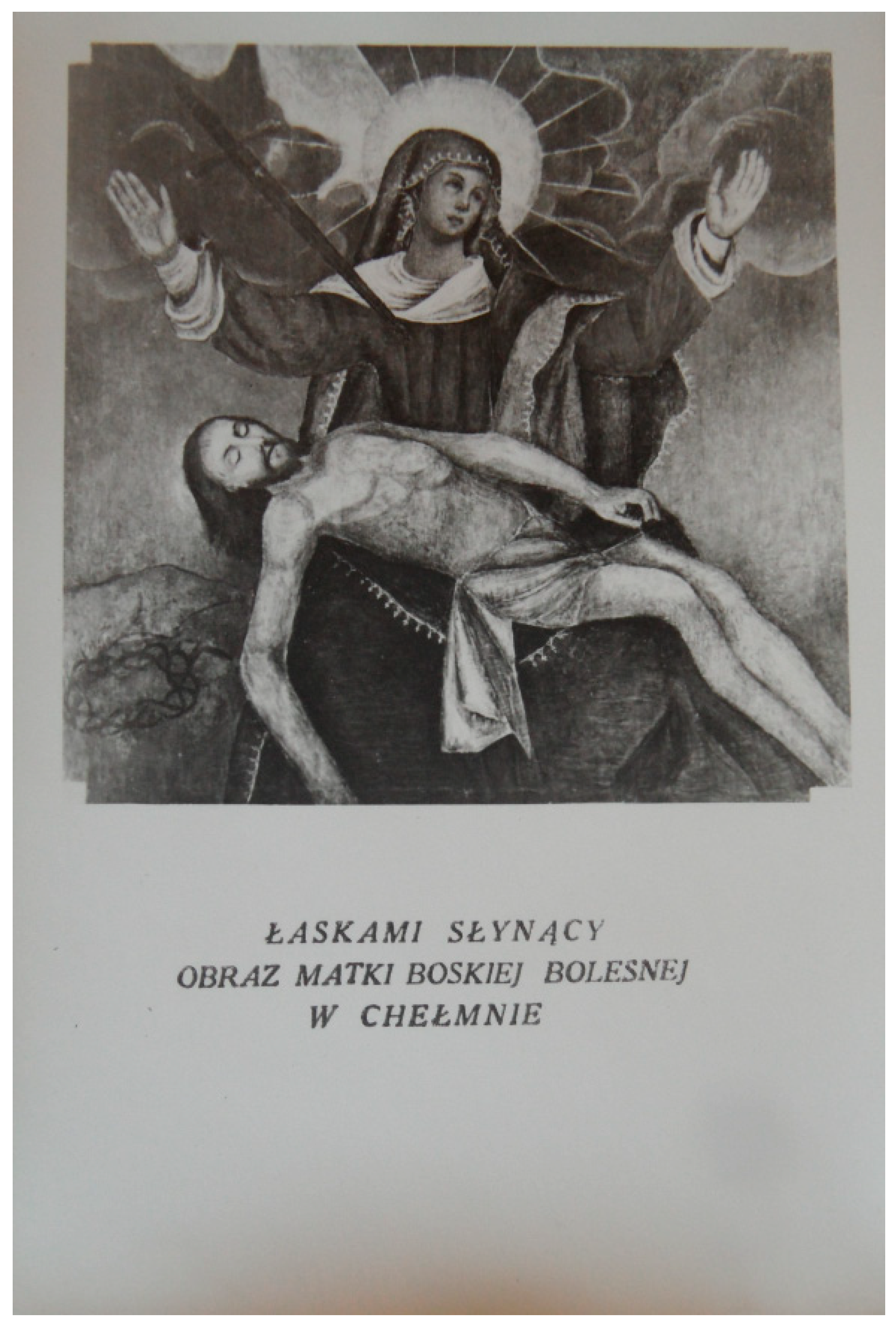

3. Celebration of the Parish Indulgence in the Example of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Sorrows in Chełmno

the faithful easily understand the vital link uniting Son and Mother. They realise that the Son is God and that she, the Mother, is also their mother. They intuit the immaculate holiness of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and in venerating her as the glorious queen of Heaven, they are absolutely certain that she who is full of mercy intercedes for them. Hence, they confidently have recourse to her patronage. The poorest of the poor feel especially close to her. They know that she, like them, was poor, and greatly suffered in meekness and patience. They can identify with her suffering at the crucifixion and death of her Son, as well as rejoice with her in his resurrection. The faithful joyfully celebrate her feasts, make pilgrimage to her sanctuary, sing hymns in her honour, and make votive offerings to her.(DPPL 183)

3.1. An Outline of the History of the Sanctuary in Chełmno

On 18 March 1662 (AD), the Father Franciscus Skulski Ordin stayed at the Order of Friars Minor Conventual in Chełmno, while being here at the novitiate he became blind (17 years ago), and for seven or eight Sundays he remained in this blindness. Knowing about the Miraculous Image of the Virgin Mary of Sorrows above the Grubieńska Gate, he went there. The brothers took him there, first he washed his eyes with water from the Spring—built in the shaft under the mountain—then he went to the Image, where he—thanks to this Virgin—regained his health and sight.

Dismiss the plague with Your uplifted Hand.Restore the crop, destroy all the blemishes in the grains.Let the devilish and human anger subside.By your grace, more fruitful crops will follow.

The poor beggar seeks your helpThat you may protect him both day and nightO Mother full of counsel in this image.

3.2. Forms of Popular Piety Related to the Indulgence of Chełmno

This year’s Chełmno indulgence was held in extremely beautiful weather and with an exceptionally large number of pilgrims—some of them already arriving on the eve of the indulgence—pouring into our town from all parts of Pomerania. On Friday morning, trains brought several companies of pilgrims, who were greeted with unrolled banners and a chant in the procession heading for the Gate. Both Dworcowa and Grudziądzka Street—reaching from the Starosta building to the Water Gate—were literally packed with people. This is the evidence on how large masses of people participated in the procession. People attending the celebration are estimated at 12,000. Pilgrimages led by priests from the St. Cross in Grudziądz and from Wabcz parishes were greeted at the Gate by the rev. dean, dr. Rogal, and the companies of pilgrims from St. Trinity church in Bydgoszcz. The last group came by steamboat, and was therefore greeted by the rev. dean in front of the Water Gate. 32 priests arrived. Seven sermons were preached, and innumerable crowds of pilgrims approached at the Lord’s Table.“Nadwiślanin” nr 54 (7 July 1926, p. 2)

3.3. Differences in the Celebration of the Indulgence throughout Half a Century

4. Fiestas Patronales and Parroquiales in Spain and the Example of Villamayor de Monjardin (Navarra)

4.1. The Parish and the Organization of the Fiesta; the Cross of Monjardin as an Object of Worship; St. Andrew

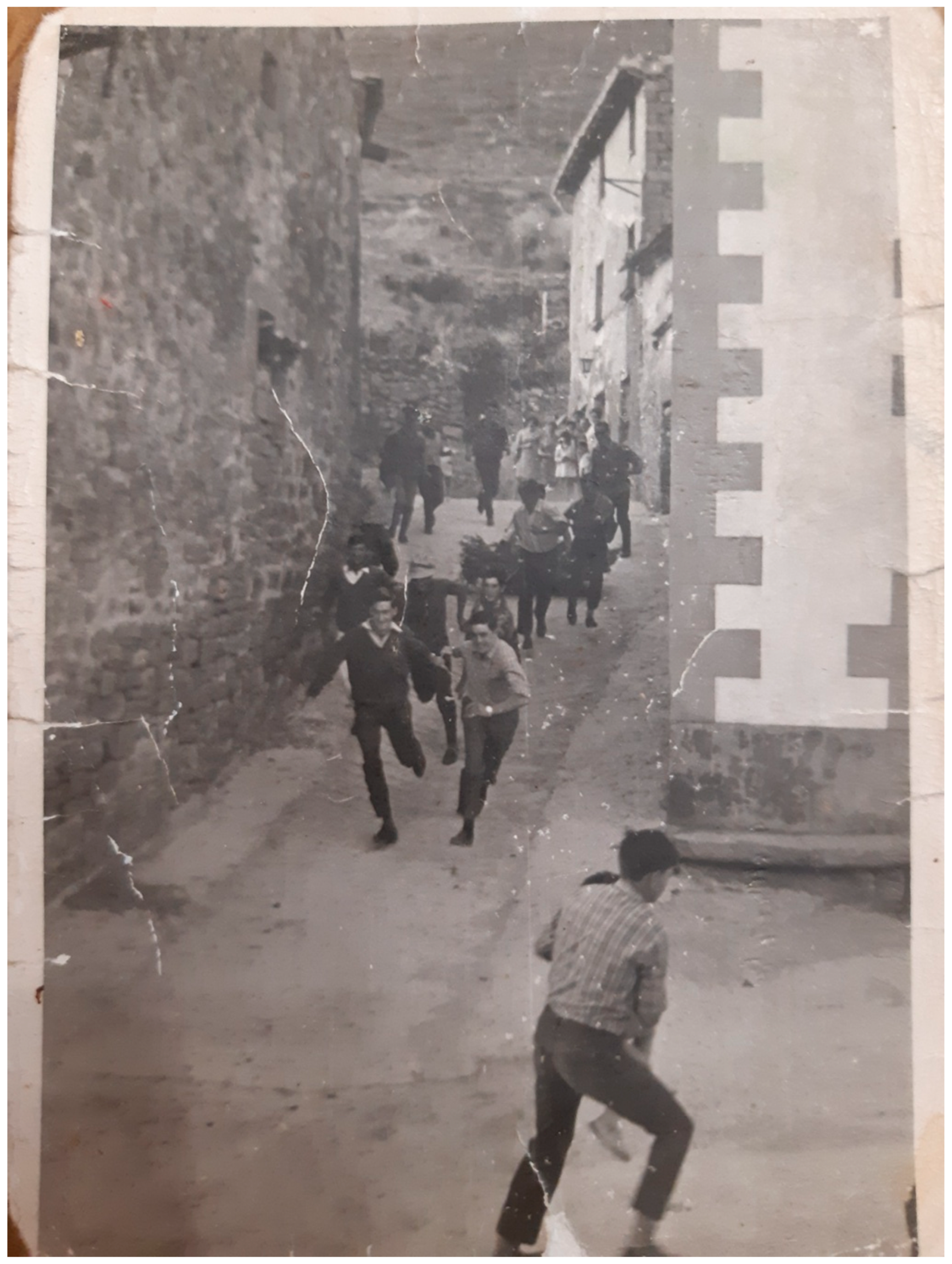

4.2. Forms of Popular Piety during Patronal Feasts

4.3. Changes in the Forms of Celebration in 1948–98. Periodization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCC | Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992). Promulgated by John Paul IIU, October 11. |

| DPPL | Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (2002). Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy: Principles and Guidelines. London: Catholic Truth Society Publications. |

| EN | Pope Paul VI (1975). Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi. On Evangelization in the Modern World. December 8. |

| SC | Second Vatican Council (1963). Sacrosanctum Concilium: Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. December 4. |

References

- Aulet, Silvia, and Dolors Vidal. 2018. Tourism and religion: Sacred spaces as transmitters of heritage values. Church, Communication and Culture 3: 237–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John Anthony. 2017. Christian Witness: Its Grammar and Logic. Biblica et Patristica Thoruniensia 2: 231–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cañada, Alberto. 1976. La Campaña Musulmana de Pamplona. Pamplona: Diputación Foral de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Caro Baroja, Julio. 1971. Etnografía Histórica de Navarra. Pamplona: Caja de Ahorros de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. 1992. Promulgated by John Paul II. October 11. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. 2002. Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy: Principles and Guidelines. London: Catholic Truth Society Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Delicata, Nadia. 2018. Homo technologicus and the Recovery of a Universal Ethic: Maximus the Confessor and Romano Guardini. Scientia et Fides 2: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Moreno, José Maria. 1979. Acuerdos Iglesia-Estado en España: Notas marginales. Estudios Eclesiásticos 54: 283–334. [Google Scholar]

- Donadzki, Mateusz Antoni. 1721. Prawdziwy Abrys Matki Boskiey na Gorach Chełminskich, Śpieszno Ratuiącey Grzesznika Przez Kapłana Swieckiego, Stylem Kaznodzieyskim. Rome: Bibliografia Staropolska. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, Marian. 2006. Myśląc Parafia…Papieża Jana Pawła II Wizja Parafii. Częstochowa: Studium Teologiczno-Pastoralne. [Google Scholar]

- Działowski, Gustaw. 1937. Kilka Wspomnień z Czasów Mojego Pobytu w Gimnazjum w Chełmnie (1881–93). In Księga Pamiątkowa Stulecia Gimnazjum Męskiego w Chełmnie 1837–1937. Wąbrzeźno: Drukiem Zakładów Graficznych Bolesława Szczuki, pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dziura, Małgorzata. 2017. Ludowe zwyczaje odpustowe. In Chrześcijaństwo w Religijności Ludowej—1050 lat po Chrzcie Polski. Edited by Zdzisław Kupisiński. Lublin: Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski, pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Clara. 1989. Imaginería Medieval Mariana en Navarra. Pamplona: Institución Principe de Viana. [Google Scholar]

- Gółkowski, Józef. The singing during Holy Mass and the devotion to the Blessed Virgin of Sorrows in the Chełmno Image, famous for its miracles and the most popular Hymns. Chełmno.

- Goñi Gaztambide, José. 1979. Historia de los Obispos de Pamplona. Eunsa: Pamplona: Institución Principe de Viana, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hojak, Piotr. 1988. Sanktuarium Matki Boskiej Bolesnej w Chełmnie w latach II wojny światowej. Studia Pelplińskie 19: 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat, Saša. 2017. Heideggerov posljednji Bog. Bogoslovska Smotra 4: 745–66. [Google Scholar]

- Huzarek, Tomasz. 2018. Thomas Aquinas’ Theory of Knowledge through Connaturality in a Dispute on the Anthropological Principles of Liberalism by John Rawls. Espiritu 156: 403–17. [Google Scholar]

- Isambert, François-André. 1976. La sécularisation interne du christianisme. Revue Française de Sociologie 17: 573–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno Jurio, José Maria. 1988. Calendario Festivo. Invierno. Collecion Panorama no. 10. Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra, Institución Principe de Viana. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak, Czesław. 2016. Sanktuaria i Pielgrzymki. Teologia, Liturgia i Pobożność Ludowa. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak, Czesław. 2017. Liturgia i Pobożność Ludowa w Nauczaniu i Praktyce Kościoła. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, Franciszek. 2017. How has Camino developed? Geographical and Historical Factors behind the Creation and Development of the Way of St. James in Poland. In The Way of St. James: Renewing Insights. Edited by Enrique Alarcón and Piotr Roszak. Pamplona: Eunsa, pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, Franciszek. 2019. Changes in religious tourism in Poland at the beginning of the 21st century. Turyzm/Tourism 29: 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nadolski, Bogusław. 1992. Liturgika. Sakramenty, Sakramentalia, Błogosławieństwa. Poznań: Pallotinum, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, Lluis. 2019. Meaning and Religion: Exploring Mutual Implications. Scientia et Fides 1: 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Agote, Alfonso. 2012. Cambio Religioso en España: Los Avatares de la Secularización. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. [Google Scholar]

- Perszon, Jan. 2019. Teologia ludowa. Kontekst inkulturacji Ewangelii. Pelplin: Bernardinum. [Google Scholar]

- Perszon, Jan. 2020. Pilgrimages in times of trial: The pilgrimage movement and sanctuaries in Polish lands in the second half of the nineteenth century. In Nineteenth-Century European Pilgrimages: A New Golden Age. Edited by Antón M. Pazos. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Pilarz, Krzysztof. 2020. Tożsamość relacyjna. Wybrane wątki biblijnych opowiadań o Adamie i Ewie z Rdz 1–3 jako antropologiczne źródło inspiracji terapeutycznej. Teologia i Człowiek 1: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platovnjak, Ivan. 2017. Vpliv religije in kulture na duhovnost in obratno [Influence of Religion and Culture on Spirituality and Vice-Versa]. Bogoslovni vestnik 2: 337–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Paul, VI. 1975. Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi on Evangelization in the Modern World. Boston: Pauline Books & Media. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Téllez, Alberto, and Wilson Hernando Soto Urrea. 2020. Religion explained? Debate regarding the concept of religion as a ‘natural phenomenon’ in Daniel Dennett’s perspective. Scientia et Fides 1: 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak, Piotr. 2015. Mozarabowie i ich liturgia. Chrystologia rytu hiszpańsko-mozarabskiego. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UMK. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak, Piotr. 2018. Sentido eclesiológico del patrocinio de los santos. Scripta Theologica 1: 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak, Piotr. 2020. Mute Sacrum. Faiths and its Relation to Heritage on the Camino de Santiago. Religions 11: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Salvador. 2012. Some Reflections on Theology and Popular Piety. The Heythrop Journal 53: 961–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martin Gil, Carmelo. 2005. Monjardin. El Castillo y la Villa. Villamayor de Monjardin: Sahats. [Google Scholar]

- Second Vatican Council. 1963. Sacrosanctum Concilium: Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. December 4. Available online: https://adoremus.org/1963/12/sacrosanctum-concilium/ (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Seryczyńska, Berenika. 2019. Creative Escapism and the Camino de Santiago. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 5: 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tanco, Jesús. 2003. Un ritual y sus signos: Los sanfermines de Pamplona. In Fiesta. I Ceri di Gubbio. I Tori di Pamplona. Universitá per Stranieri di Perugia. Encuentro cultural. Perugia-Gubbio, 14–15 de mayo, 2002. Perugia: Morlachchi Editore, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tykarski, Sławomir. 2019. The evolution of modern marriage: From community to individualization: Theological reflection. Cauriensia 14: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, Łukasz. 2018. Religious tourism in Christian sanctuaries: The implications of mixed interests for the communication of the faith. Church, Communication and Culture 3: 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wółkowski, Jan. 2019. Relacje między Kościołem powszechnym a Kościołami lokalnymi w myśli ks. José Ramóna Villara. Teologia w Polsce 1: 225–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, Marek. 2006. Chełmińska Mater Dolorosa. In Chełmno Zabytkami Malowane. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoski Dom Wydawniczy Margrafsen, pp. 267–96. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Church may have more than one patron saint, which results in the parish experiencing two indulgences per year. Usually one of them is celebrated more solemnly than the other, gathering more faithful. |

| 2 | In the pre-conciliar liturgy, there were four classes of liturgical celebrations, depending on the importance of the feast in question. Such a gradation has always existed in the history of the liturgy, and in the case of the 1st class it concerned the possibility of celebrating the vigil. Details are provided in the General Rubrics of the Tridentine Missal, Chapter 2, Section 8. |

| 3 | “Boże coś Polskę” is a Catholic religious hymn which aspired to be recognized as the national anthem after Poland regained independence in 1918. |

| 4 | The rite of “papal crowns” refers to the pious institutional act of the Pope, in which he bestows an ornamental crown, diadem or halo to a Marian image or statue that is venerated in a particular locality. |

| 5 | “Nadwiślanin” no. 66 (15 July 1861), p. 4. Author’s translation. |

| 6 | See “Pilgrim” no. 76 (6 July 1882), pp. 2–3. |

| 7 | While discussing this part of the article, it should be clarified that the acquired information and historical records derive from before 1948 and date back to the 1920s and 1930s. This is due to historical and political conditions. During World War II, from 1939–1945, Poland was under Nazi occupation, which impeded the traditional celebration of the indulgence on account of anti-religious regulations. In view of the dramatic war events, there was no intention of perpetuating the pilgrimage celebrations. Moreover, at that time, due to the prohibition of the Germans regarding the impossibility for the faithful—from outside Chełmno—of coming to the sanctuary, the pilgrimage movement ceased completely, which forced the traditional celebration of the indulgence to be abandoned. A similar situation took place after the end of the war. In Poland, under the influence of the Soviet Union, communism, atheization and a systemic struggle with the church and religion prevailed. There was no possibility of publishing topics promoting faith or providing information on religious events in the press. Hence, little can be found about the Chełmno indulgence. The situation changed after 1989, when communism collapsed in Poland. Although the partially obtained materials go beyond the time frame adopted in the article, this does not in any way affect the reliability of the presentation of the issue related to experiencing the parish church indulgence in Chełmno. On the functioning of the Chełmno sanctuary during World War II, see (Hojak 1988) |

| 8 | The data comes from the parish bulletin “Głos” no. 61 (1–2 July 1997), p. 3. |

| 9 | See Kalendarz Kościelny dla Parafji Chełmińskiej na rok Pański 1934, p. 22. A year earlier, 12,000 Communions were distributed, and 38 priests were listening to confessions in the confessional. See Kalendarz Kościelny dla Parafji Chełmińskiej na rok Pański 1933, p. 26. To illustrate the number of arriving pilgrims, it is worth noting that as of 17 April 1926, the number of Chełmno inhabitants was 10,571. Thus, the crowd of believers participating in the indulgence was in fact huge. See “Nadwiślanin” No. 31 (17 April 1926), p. 3. |

| 10 | See “Dziennik Bydgoski” no. 150 (4 July 1939), p. 7. |

| 11 | See “Nadwiślanin” 1922, no. 42 (9 July 1922), p. 2. |

| 12 | See “Głos” no. 61 (1–2 July 1997), pp. 3–4. Cf. “Pielgrzym” no. 83 (13 July 1926), p. 3. To illustrate: the distance between Chełmno and Gdynia is about 150 km, Puck 170 km, Brusy 90 km, Czersk 70 km. |

| 13 | See “Głos” no. 62 (31 August 1997), p. 4. |

| 14 | See “Głos” no. 83 (1–2 July 1998), p. 4. |

| 15 | See Historia cudownego obrazu Matki Boskiej Bolesnej w Chełmnie, Wąbrzeźno 1938, pp. 25–27. |

| 16 | The reprint of the litany text can be found in “Głos” no. 61 (1–2 July 1997). |

| 17 | An exemplary calendar of the indulgence celebration, see “Głos” no. 82 (21 June 1998), p. 1. |

| 18 | “Głos” no. 61 (1–2 July 1997), p. 2. |

| 19 | See “Przegląd Chełmiński” no. 74 (5 July 1938), p. 3. |

| 20 | The change in question can be well seen when comparing the posters—informing about the Chełmno Days from the 1970s (available at the Museum of the Chełmno Land under the reference number MZCH/E/810, MZCH/E/703) and the 1990s (“Nadwiślanin” no. 6 (June 1993), “Nadwiślanin” no. 12 (19 June 1997), p. 4). |

| 21 | For the indulgence in 1933, the local printing house issued a special souvenir of the Chełmno indulgence with the text of a prayer to the Mother of God. |

| 22 | See “Czas Chełmna” no. 27 (9 July 1998), pp. 1.8–9; “Nadwiślanin” no. 27 (8 July 1998), p. 1. |

| 23 | “Przegląd Chełmiński” no. 74 (5 July 1938), p. 3. |

| 24 | After the end of World War II, thanks to the interference of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in Poland, a communist regime prevailed, with the main goal of a broadband atheization of the society and a fight against the Church, for which there was supposed to be no place in public space. Structural measures were taken to abolish religion lessons in schools, interfere with the appointment of new bishops, take the lands (land) that belonged to the Church, remove nuns from hospitals as nurses and replace them with lay people, recruit clergy as secret state collaborators who were to report on prominent people, especially their bishops and superiors. The communist state apparatus used intimidation and blackmail in its methods, but also physical violence and imprisonment, which happened to Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, who in that time was the primate of Poland. However, the Polish community, due to the steadfast attitude of the episcopate and clergy, did not succumb to the process of atheization, and what is more - the Church has become a symbol of freedom and independence. So there could be no question of secularization. Paradoxically, it was only after the fall of communism in 1989, when the process of atheization subsided, that secularization began, which was not so much related to the new political system, but to trends of changes coming from Western Europe, such as: postmodernism, globalization, individualism, moral permissiveness. Thus, the process of secularization is not related to the Second Vatican Council, as to the socio-cultural changes. |

| 25 | “Nadwiślanin” no. 10 (2 July 1990), p. 2. |

| 26 | It is similar in the neighborhood of Villamayor: St. Martin of Tours is the patron of the church in Ayegui, while St. Cyprian is the patron of the whole town, in whose honor a chapel was raised on Mount Montejurra. In Villatuerta, the parish is dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the feast days refer to the cult of St. Veremundo. |

| 27 | These were two different ways to ring the bell. |

| 28 | The Spanish pendón—along banner hanging from a pole, generally finished in two ends, which is carried in processions as the insignia of a church, a brotherhood. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roszak, P.; Tykarski, S. Popular Piety and Devotion to Parish Patrons in Poland and Spain, 1948–98. Religions 2020, 11, 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120658

Roszak P, Tykarski S. Popular Piety and Devotion to Parish Patrons in Poland and Spain, 1948–98. Religions. 2020; 11(12):658. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120658

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoszak, Piotr, and Sławomir Tykarski. 2020. "Popular Piety and Devotion to Parish Patrons in Poland and Spain, 1948–98" Religions 11, no. 12: 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120658

APA StyleRoszak, P., & Tykarski, S. (2020). Popular Piety and Devotion to Parish Patrons in Poland and Spain, 1948–98. Religions, 11(12), 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120658