Abstract

In the years directly following the Second Vatican Council under the guidance of its second bishop Mons. Enrique Pelach i Feliu, the Andean diocese of Abancay—founded in 1959 in one of the most rural and most indigenous areas of Peru—experienced the founding of a new seminary intended to train a new generation of native clergy, and a concerted clerical effort to revive and promote the Marian pilgrimage of the Virgin of Cocharcas. The former meant the advent of a generation of native clergy made up of men born and raised in rural farming families in Abancay and native speakers of Quechua, the local indigenous language, which transformed the relationship between the institutional Church and indigenous Catholics from one rooted in antipathy and hostility to one based in a shared cultural background and language. The latter meant the elevation of the indigenous figure of Sebastian Quimichu as exemplar of both Andean Catholic faith and practice for his role in founding the Marian shrine of Cocharcas, and the legitimisation of popular Andean Catholic practices that had previously been stigmatised. This article provides a dual historical and ethnographic account of these events, and in doing so demonstrates the profound transformation of rural Andean lived religion and practice in the years following Vatican II.

1. Introduction

Cardinal Joseph Suenens famously called Vatican II the “French revolution in the Church”, and the reforms of the Council are indeed often framed as a revolution, with emphasis made on the stunning and drastic changes that they effected in the global Roman Catholic community. Yet, at the same time, Vatican II was an excruciating and drawn-out process: both doctrinally (as the members of the Council debated and argued over the minutiae of decrees) and in its pastoral effects (as dioceses around the world wrestled with how they wished to interpret and enact its decrees). While in some parts of the world, the changes were felt virtually overnight, in others the reforms took decades to begin to bear fruit. This article focuses on the long-term pastoral effects—especially, for rural Andean Catholic parishioners—of the actions of Monsignor (Mons.) Enrique Pélach i Feliú, the second bishop of Abancay, in the decades directly following Vatican II. He was appointed to the post in 1968—a scant three years after the closure of the Council—succeeding the first bishop, Mons. Alcides Mendoza Castro. In writing about the changes in Andean pastoral experience of the institutional Church in the decades directly following the closure of the Council, the following article examines a diocese that, crucially, first, is overwhelmingly Catholic; second, is predominantly poor, rural, and indigenous; and third, suffered immense trauma and violence and the virtual cessation of public ceremonial life for two decades as a result of the Peruvian internal conflict.

First, Abancay—a diocese encompassing the provinces of Andahuaylas, Chincheros, Abancay, and Aymaraes in the administrative region of Apurímac—was created in 1958, from territory previously belonging to the archdiocese of Cusco (to the east) and the diocese of Ayacucho (to the west). The geographic area that Abancay encompasses is one of the poorest—and most indigenous—parts of Peru: Apurímac was, until recently, commonly referred to as la mancha india—the “Indian stain” (Klarén 1990) on the face of Peru. Most of the population is rural, leading an agrarian lifestyle at around 3000 or more meters above sea level. As of 1993, 50% of houses in Apurímac had dirt floors, and 90% were built from adobe—a material that is considered to be inferior and low-prestige, and thus acts as a reliable indicator of poverty. It is also an overwhelmingly Quechua-speaking area: Peruvian census data for 1993 records that nearly 80% of the population had the indigenous language Quechua as their mother tongue; native Spanish speakers made up only 20%.1 These numbers have not changed much in the modern day: the 2017 census still recorded nearly 90% of houses being built of adobe, and approximately 70% of the population learned Quechua as their first language.2

Second, Apurímac, the region to which the diocese geographically belongs, is historically a heavily Catholic area, with approximately 90% of the population identifying as Catholic in 1993.3 This is in line with Peru at large, where Catholicism is historically dominant to the point of hegemony: for example, at the national level, Catholicism is enshrined in Article 50 of the Constitution, where the state explicitly “recognises the Catholic Church as an important element in the historical, cultural, and moral formation of Peru, and lends the church its cooperation”.4 In, for example, this parish of Talavera, this can be seen through the degree to which the Catholic Church has historically taken the place of the state: even though Talavera’s close neighbor is Andahuaylas, the administrative capital of the province, the region at large was so rural and remote that the impact of the national state was often only weakly felt. There are no reliable civil records in Talavera prior to 1936—the only records of birth and marriage for that period belong to the Church. Even today, secular civil and legal documentation continues to include and depend on Church documentation; if one wants to correct a spelling error in one’s name on one’s birth certificate, for example, one can use a baptism certificate with the right spelling and use that as legal evidence for a correction.

Third, Abancay suffered severe disruption to everyday life from 1980 to approximately 2000, caused by the Peruvian internal conflict between government military forces and the Maoist guerilla group Shining Path. The province of Andahuaylas was especially badly affected: the province of Ayacucho, with which it shares a border as well as linguistic and cultural similarities, was the epicenter of the conflict, and Shining Path began its campaign in Andahuaylas only eighteen months after it had begun in Ayacucho. By March 1982, Andahuaylas was under a “state of emergency”, and by December of that year, Andahuaylas was declared part of the “Ayacucho Emergency Zone”—essentially, placed under military rule. However, the police tended to cluster to protect the urban centers where the wealthy and mestizo lived, leaving the rural indigenous villages vulnerable not only to Shining Path but the abuses of the state military (Berg 1994, p. 110). Although Shining Path’s leader, Abimael Guzman, was captured in 1992, violence continued to erupt in the area until about 2000. Scholarly access to the area only resumed since then, and the resulting collective trauma was so severe that it is only within the last few years that people in Apurímac have been able to begin speaking about their experiences. One Protestant missionary I spoke to who was in Andahuaylas during those years recalled seeing trucks pull up with tarps full of dismembered body parts. The parish priest of Talavera recalled that as a child in the 1980s, he had to sleep in nests made of dried corn stalks in trees with his father and brothers, as it was not safe to leave young men or boys in the village at night—due to fear that Shining Path would come through and forcibly recruit them as soldiers, or worse. To write about Abancay in the years following Vatican II is thus to write against this backdrop. Drawing on historical and ethnographic material stemming from long-term participant-observation fieldwork carried out between 2015 and 2016, I focus especially on the long-lasting impact of two of Mons. Enrique’s major projects during his tenure as bishop: the founding of a seminary in Abancay in 1977, where the first generation of native clergy in living memory in Abancay were all trained; and the revival of the major Andean Catholic pilgrimage of Our Lady of Cocharcas, which now attracts thousands of pilgrims from all over the surrounding countryside every year.

2. The Seminary and a Native Clergy

When Mons. Enrique arrived in Abancay in 1968, there were fewer than twenty priests in the diocese, none of them from an indigenous background. Yet, in the present day, the diocese of Abancay now—remarkably—features an entire generation of native clergy: as of 2016, forty-eight of them continue to work in the diocese; six have been loaned out to other dioceses in need of priests. All of them were trained in the seminary in Abancay; all of them are from Apurímac itself, from indigenous backgrounds; all of them are native speakers of Quechua, the local indigenous language. They are all relatively young, with the oldest in his fifties or so, and the youngest in his twenties. This generation of native clergy are the result of a longstanding call within the Roman Catholic Church. During the twentieth century, both Pope Pius XI and Pope Benedict XV strongly exhorted dioceses around the world to cultivate a native clergy and ecclesiastical hierarchy—because that is the ultimate goal of missionary activity, to establish a self-sufficient native clergy and ecclesiastical hierarchy that would not need imported foreign priests to keep afloat (de la Costa 1947; Clark 1954). As far back as 1624, the great Spanish jurist Juan Solórzano Pereyra wrote that,

“…not only Mestizos, but the Indians themselves, after [being] well converted and indoctrinated, have to be entrusted with this duty [of the priesthood], and even of the Episcopal [responsibilities], for the greatest persuasion and easier conversion of their companions, taking for this the example of Titus, and of Timothy, and other places in the Holy Scripture, and one very elegant [example] of Saint Ambrose…”(Hyland 1998, p. 448).

Yet, despite this call for a native clergy, the priests in Abancay are—and are aware that they are—a historical anomaly. A native clergy was a goal that had long largely eluded the rural Andes, rooted in large part in longstanding and deeply held discrimination against indigenous people. In colonial Mexico, those who did not want mestizo priests ordained argued that Mexican Indians were simply too common and had none of the ascendancy with which is necessary to preach (de la Costa 1947) and in 1555, officially excluded all Mexican Indian men from Holy Orders (Hyland 1998). Peruvian bishops followed in their footsteps and refused to ordain Peruvian Indians as priests, and in 1582, the Jesuits unanimously voted to exclude all mestizos from the Society (Hyland 1998). In 1677, Archbishop Pardo of Manila argued against a previous decree supporting native Filipino clergy, because Indians had “evil customs and ideas” that necessitated paternalistic handling. For him, even creoles—that is, men of Spanish descent who had been raised in the colonies—were deficient, because although their descent was Spanish, their nannies were sure to have been native women who would have taught them badly. In modern times, the longstanding status quo in the Andes has been a priesthood that tended to be dominated by either mestizo or European men. For this reason, the ethnographic literature has generally described priests as being identified with “white authorities” such as the military (Weismantel 2001, p. 224), counted as outsiders generally (Canessa 2012), and seen as symbols of foreign domination (Isbell 1978). Such a priest—especially one occupying rural parishes—was stereotypically “invariably pretentious in his learning, condescending in his attitude toward the Indians, avaricious in money matters, hypocritical in personal morality and forever involved with the local officials in new schemes to exploit the people further. Also, he is frequently a Spaniard” (Klaiber 1975, p. 292).

By 1963, the situation was deemed so grave that Romolo Carboni—the Vatican ambassador to Peru at the time—urged that the country must be provided with the “means to develop a native clergy as soon as possible. […] If we do not find priests immediately for Latin America we will have no one to recruit and train native vocations for the future; we will lack a source of highly-qualified men for the episcopacy; we shall witness the Church gradually shrivel up here and die” (Carboni 1963, p. 346). Carboni illustrated his point with the rapid decline of priest numbers in the post-revolutionary era: as of the late eighteenth century in Cajamarca, there had been one priest for every 3000 Catholics; a century later, there was one priest for every 5700 Catholics; and as of the 1960s, one for every 12,000. Although he referred specifically to Cajamarca, this situation was not unique to Cajamarca: in 1969, the archdiocese of Cusco—which at the time served nearly half a million people—had only ninety-eight priests (Sallnow 1987, p. 16).

Vatican II had amplified this longstanding call and need for a native clergy, which would facilitate the Council’s goal of “opening up” and updating the Church. Nevertheless, Mons. Enrique was faced with skepticism and difficulties when he proposed opening a seminary in Abancay. There had never been a seminary in Abancay; as he writes in his memoirs, founding a seminar “in those first post-council years […] had…the air of the impossible.” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1368–1372). He had to begin from the basics, by “explaining what a seminary was, and the advantages of training generous young people from [the local area] that, without a doubt, Jesus wanted to call to his service” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1372). He compared his dream of opening a seminary to the story of the man who shoots at the moon, saying that “for the more knowledgeable, because they had read some newspaper or magazine, the idea of a seminary in Abancay was simply insanity. For the majority the project was one which they could not understand clearly. ‘How will it be, Father!’ said some. ‘We’ll see…’ said others, with obvious incredulity.” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1374).

He began first with a minor seminary, which he opened within two years of his arrival in Abancay, with two students and one rector. His memoirs recount how he had great dreams of vocations for the priesthood resulting from this minor seminary, and prayed for it regularly; but pupils did not increase in number, and after four years they had only five students in total (Pèlach Feliú 2005). Things took a miraculous turn for the better in 1975, however, when suddenly parish priests began volunteering forward young parishioners who had expressed a desire to become a priest. A total of twelve were enrolled that year, and the numbers continued to increase steadily. Eventually, in 1977, Mons. Enrique was able to found the Our Lady of Cocharcas Major Seminary in Abancay, which, at its peak during the 1980s and 1990s—according to a priest in Talavera who I spoke to and who was himself trained in the seminary—housed and taught hundreds of seminarians.

Given that he founded the seminary where they were all trained, it is unsurprising that Abancay’s generation of native clergy today by and large attribute their generational existence to the efforts of Mons. Enrique. They remember him personally, as he taught at the seminary for many years and remained in Abancay after his retirement until his death in 2007. What is more, they remember him fondly: stories circulated often about him, reminiscing about the long journeys he used to take across Abancay in order to visit far-flung parishes. In those days, there were no roads traversable via car, and so on his tours of the diocese he travelled via horseback. One favorite anecdote I heard repeatedly was about the night that Mons. Enrique, sleeping peacefully in a rural parishioner’s home, had his toe bitten by a goat in search of a snack—startling him awake, which in turn scared the goat and set off a chain reaction that soon had the entire house in an uproar (Pèlach Feliú 2005). They also remembered with some admiration his fluency in Quechua—to the point where he wrote a catechism, and a bilingual Quechua–Spanish prayer book which is still in widespread use today. Additionally, they noted proudly that he settled so well in Abancay that he refused to retire to Spain when he retired, instead choosing to stay and eventually die in the diocese.

In the modern day, the ministry of these indigenous priests produced by the diocese’s seminary coupled with their use of the vernacular Quechua liturgy has resulted in an unprecedented pastoral relationship between the institutional Church and parishioners in Abancay—especially rural parishioners. Sacrosantum Concilium, or Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy—the first document from the Council to be promulgated, in 1963—laid the groundwork for the reform of the Church’s liturgical life, with an especial emphasis on “fully conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations”.5 The liturgical reforms were some of the first and most widespread effects of Vatican II to be felt by lay Catholics, including the introduction of the vernacular liturgy.

The Quechua Missal now in use in Abancay today was published in 1980, a project spearheaded by the nearby diocese of Huancavelica, and one which was crucial for an area thtat was and continues to be heavily Quechuaphone. According to the 1993 census, nearly 80% of the population of Apurímac had Quechua as their first language; even as of the most recent census in 2017, nearly 70% of the population named Quechua as their mother tongue—twice as many as those who listed Spanish.6 Many of these Quechua-speakers were not bilingual: the parish priest of Talavera, Father (Fr.) Simón, spoke only Quechua until the age of ten; his family despaired for years of him ever learning Spanish—as he would have to, if he wanted to lead a life outside of agriculture.

Even so, just because a Quechua liturgy was available did not necessarily mean it was commonly used. The ethnographic literature on priests and Mass in rural Andean communities is marked by descriptions of disdain and dismissal on the part of the priests for their parishioners rooted in racial discrimination, manifested through a disregard for their pastoral and sacramental needs. Abercrombie (1998) describes how the priest showed up in another community in highland Bolivia to review some repairs to the church and was only persuaded with much difficulty to celebrate Mass, during which he delivered a sermon that Abercrombie described as “more like a litany of abuse” (106):

Decades later, Canessa describes a priest who delivered sermons in Spanish to a largely non-Spanish-speaking congregation, and who had a low opinion of the rural villagers, considering the “the comprehension of basic tenets of Catholic beliefs such as Transubstantiation, the Virgin Birth, and the Mystery of the Trinity to be quite beyond the indians” (2012: 58). Fr. Simón himself recalled hearing Mass as a child in the 1980s, in his rural village above Abancay—celebrated by a white priest in Spanish, meaning that it “might as well have been in Latin for all I understood of it”, as he put it.“The priest began with reference to the new floor, which he judged the product of poor workmanship and a lack of proper Christian zeal. Speaking in a rarefied Chilean Castilian (marked by the vosotros verbal declinations) that was, fortunately, largely unintelligible to most of this flock, he admonished all present to take the gringos among them as their guides, to wash themselves more frequently, dress in livelier colours, eat at table with knife and fork, and rebuild their homes to make separate bedrooms for parents and children. […] The priest pointedly addressed these chidings to the assembled authorities…whom he referred [to] as his hijitos (“little children”). All in all, the sermon struck me as profoundly insulting and deeply ethnocentric, in which the priest painted himself…in the well-known, patronising pose of civilising missionaries”(106–107).

Due to the emphasis on lay participation and understanding that Vatican II and the vernacular liturgy encouraged, the choice of language is not merely about incomprehensibility, but is also intimately intertwined with the ability of Andean Catholics to access the sacraments. In previous decades in the Andes, this has manifested in the grumblings of foreign priests about the superficiality of Andean Catholicism, especially with regards to the sacraments. Orta (2002, p. 724) quotes Father William, a North American priest who had been working in Bolivia since the 1960s, as characterizing Euroamerican Catholicism as having “deep roots of faith”, in contrast with Bolivian Catholicism, “where the roots of faith are not that deep. They’re all superficial. They were imposed and they were not allowed to evolve and mature as happened in Europe”. Particularly, complaints revolved around the treatment of the sacraments, such as baptism and Mass—many missionaries who Orta interviewed who had worked in Peru during the fifties, sixties, or seventies complained about “sacramentalism”, the feeling that indigenous Andeans had attached so much importance to the sacraments that it felt more like superstition than faith. Thus, Harris describes the priest where she worked in Bolivia who derided the local indigenous community for using Mass as a “magical instrument for gaining specific ends” (Harris 2000, p. 56) and so “considered it a waste of time, if not downright superstitious, to say Mass in the Indian communities” (Harris 2000, p. 56).

In Apurímac, in contrast, the priests who emerged from the Abancay seminary are themselves indigenous Andeans, who have been trained to have sympathy for their parishioners. This is in keeping with Mons. Enrique’s own explicit sentiments, where he described the people of Abancay as “profoundly religious, and have maintained the faith received from the first evangelizers, despite the shortage of priests” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 502–503). I observed in Talavera that the priests took explicit care to celebrate the Mass in Quechua whenever they were in the rural, more Quechua-speaking villages—explicitly so that rural parishioners might understand the words of the liturgy, might be able to confess in their native tongue, and thus might be able to receive the sacraments. This approach stands in stark contrast with the North American priests described by Orta. Furthermore, most rural villages with a catechist now receive Mass at least once monthly—still less often than is ideal, as Fr. Simón admitted, but much more often than was previously the case just a few decades ago.

Such actions affect Andean parishioners deeply—not only for the attention paid to their sacramental needs, but also especially in a national context where Quechua is often called a “dialect” as a way of diminishing its status as a language, and Quechua monolinguals face a great deal of discrimination (Weismantel 2001). One priest in Talavera told me, in joking mock outrage, that sometimes old Quechua women would give their confession and then immediately go to the back of the queue again to confess again, simply because—he assumed—they were lonely and wanted to have someone to talk to. He would send them away, but gently, as it never seemed to put them off for long. This kind of rather casual, familiar relationship for an elderly indigenous woman with the priest would have been unthinkable only a few decades ago, and difficult without a native clergy—who not only speak their language, but have an understanding of and sympathy for the difficulties of agrarian life.

A vernacular liturgy in Quechua would have been possible without the development of a native clergy; Mons. Enrique himself was fluent in Quechua (a fact that contributes to how fondly he is remembered today in the diocese), and indeed there are other parts of the Andes that are staffed mostly by foreign priests who speak Quechua. However, the situation in Abancay is qualitatively different because of this native clergy, because it stems from empathy on the part of the priests for their parishioners with whom they share a cultural background. They themselves recall a past that featured not only an incomprehensible Spanish liturgy—as Fr. Simón described—but also priests who visited their communities only a few times a year at most. In attending to the language in which Andean Catholics, and their ability to partake regularly of the sacraments, such practices affirm the validity and worth of indigenous Andean lived Catholicism. The shift from Catholicism being experienced by rural indigenous Andeans in Spanish to Quechua marks a sea-change in local understandings of Catholicism: from incomprehensibility not just with regards to the Spanish liturgy, but also an incomprehensible liturgy and priest, to a Quechua liturgy and a Quechua priest who attends and delivers the sacraments regularly. Such a situation is the direct result of episcopal efforts in Abancay in the decades following Vatican II: notably, the founding of the seminary where today’s priests were trained to approach their Andean parishioners with consideration rooted in a shared cultural background—a cultural background that they were also taught to take pride in, rather than to be ashamed of. It marks, as such, a transformation in the relationship between Andean culture and the institutional Catholic Church—from a hostile, disdainful face to one that is sympathetic and even empathetic.

3. The Virgin of Cocharcas

I move next to a discussion of another one of Mons. Enrique’s projects as bishop, and its lasting effects: the revival of the major Andean pilgrimage of the Virgin of Cocharcas. The pre-eminent pilgrimage site in Apurímac, the Virgin of Cocharcas is the patron saint of the diocese and of its seminary, and has been venerated for over four hundred years. Celebrations in honor of Mamacha Cocharcas—as she is affectionally called by locals in Quechua—in early September continue to attract thousands of pilgrims from all over the surrounding area, both rural and urban. Many of these pilgrims come on foot, trekking for days up the mountains that surround the valley in which Cocharcas nestles, and gingerly winding their way down steep stopes to reach the magnificent colonial-era church that hosts her.

This Marian shrine dates from the 17th century, and is a copy of the image that is venerated at the shrine to Our Lady of Copacabana at the southern edge of Peru. Copacabana—the shrine whose image Our Lady of Cocharcas was a copy of—is located on the shores of Lake Titicaca, a place that was sacred for the Incan empire that predated the Spanish invasion. During the Incan empire, thousands of pilgrims journeyed to the Islands of the Sun and the Moon on the lake, where the shrines to the Sun and the Moon were (Bauer and Stanish 2001). After the fall of the Incan empire, pilgrimages to Lake Titicaca continued—but in the form of the Marian devotion to Our Lady of Copacabana, which was, in many ways, a Christian transformation of this ancient, pre-Spanish pilgrimage in the Andes (Salles-Reese 1997).

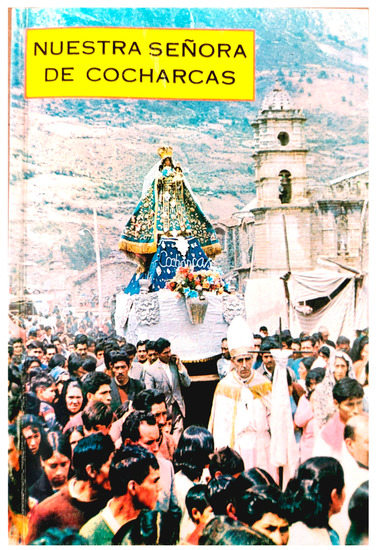

Like the Marian shrine of Copacabana, the shrine at Cocharcas was founded on the “piety of a simple Indian” (Vargas Ugarte 1947, p. 553)—here, on the piety of a young man named Sebastian Quimichi.7 The first hagiography of Quimichi—“quimichu” meaning “he who carries [the image of the Virgin]”—was published in 1625 by the priest Don Pedro Guillen de Mendoz and recounted by Mons. Enrique (Figure 1) in his 1972 book, titled simply Our Lady of Cocharcas, which told the history of the shrine and offered a glowing account of the faith of modern pilgrims, accompanied by apologetics regarding the veneration of images and of Mary.

Figure 1.

The cover of Mons. Enrique’s book on Our Lady of Cocharcas, featuring a photo of Mons. Enrique himself leading a procession in her honor in Cocharcas. The colonial church is seen in the background. Photo by Father Simón Villafuerte Herhuay.

As Mons. Enrique retells, Guillen describes how Quimichi—himself from the village of Cocharcas, then only a village of twenty families—was from a young age a devout Christian, and “personally taught [the Catechism] on feast days and holy days of obligation on Sunday, assisting the Church with much care and vigilance. In the [Church] he took particular pleasure and consolation in exercising and occupying himself in such good ministries as washing the church and caring for its cleanliness and decoration; and, additionally, had particular enthusiasm for teaching Christian doctrine to the ignorant” (Pélach y Feliu 1972, pp. 15–16).

One year, however, while celebrating the feast of Saint Peter, an accident befell him: his wrist was accidentally impaled by a lit maguey torch. In excruciating pain, feverish with infection, and no longer able to work due to his injured hand, he decided to journey to Cuzco in search of a better life. There, he met an Incan noblewoman named Doña Ines, from whose friend he heard that to the south in Copacabana there was a shrine to the Virgin that was renowned for the wonders and miracles it had wrought, and that had granted Doña Ines herself a miraculous cure for her ailments. Inspired, Quimichi decided to undertake the same pilgrimage in the hopes of receiving a similar miraculous cure for his hand.

He confessed his sins and received the Eucharist, and set out on his journey on foot, continually invoking the name of the Virgin as he went. He had not yet arrived at Copacabana when one night in his dreams, he saw a lady calling to him, and he awoke the next day to find that the maguey was no longer lodged in his wrist, and his injury had been miraculously healed (Pélach y Feliu 1972). Filled with joy, he continued on his journey to Copacabana, praying novenas as he walked. Upon seeing the image of the Virgin in Copacabana, he was filled with a desire for his hometown of Cocharcas to have a copy. Eventually, he was able to convince the Augustinians in charge of the shrine to purchase a copy of the image of the Virgin—carved by the same artist who had made Copacabana’s statue—and departed carrying it on his back. When he reached the town of Juli, the Jesuits there received him with bells and celebrations, and he was joined in his journey by a group of devout Indians who accompanied him, singing Quechua hymns, for the rest of his journey. Quimichi and his followers were greeted in each town by the ringing of church bells and “demonstrations of joy… that could only be attributed to the Divine Will and the disposition of Heaven” (Pélach y Feliu 1972, p. 32).

Despite the obstacles he encountered—for example, a parish priest near the town of Urcos had Quimichi and his followers thrown in prison on suspicion of secretly practicing pre-Christian rituals, but the bishop’s investigation of the matter showed that Quimichi’s faith and devotion was genuine, and he was released—the Virgin eventually made its way to the community of Puyara, where she waited for her chapel in Cocharcas to be finished. At the time, Cocharcas had no church and only a small chapel; and so it had been that the priest went there very rarely (1972: 33). However, the people of Cocharcas were so intent on bringing the image that after only two months, the shrine was complete; she was installed in September of 1598; and from there, “God began to work through her marvelous miracles” (Vargas Ugarte 1947, p. 556).

Unfortunately, Quimichi did not live long afterwards. Once the Virgin had been settled, Quimichi set out again to seek donations for the shrine, and died of illness not long thereafter in Cochabamba in modern-day Bolivia. In 1625, Quimichi’s remains were repatriated, and he was reburied with great pomp and circumstance in the church at Cocharcas, under the left tower at the front of the church. Today, his remains have once again been moved, and he now lies in a devotional chapel inside the church, marked by a marble plaque (Hyland n.d.).

Hagiographies are not really biographies in the modern sense; rather, they are stories that are responding to social and doctrinal forces of the time (Weinstein and Bell 1982, p. 13). Medieval hagiographies, for example, often featured the saints in question facing and overcoming great suffering and trials, and in doing so, exemplifying the rewards of Christian piety and inspiring others to follow in their footsteps (Weinstein and Bell 1982, pp. 159–60). In this, Guillen’s hagiography of Quimichi resembles medieval ones in that the account of Quimichi’s “patience and continuing faith in the face of injustice were meant to inspire other natives to embrace similar behaviors” (Hyland n.d., p. 15). At a time that was barely a century out from the initial evangelization of the Andes, such a tale sought to provide a model of Andean Christian piety and virtue for other Andean Christians to emulate.

Mons. Enrique’s actions in publishing an account of Quimichi in 1972 are, therefore, also to be read in light of the social and doctrinal needs of the time. In 1972, it was a mere seven years after Vatican II, and the diocese itself had only been in existence for thirteen years. He himself had only been in Abancay for four years and he had arrived—as he recorded in his memoirs—to a diocese that was desperately understaffed and extremely poor. Infant mortality rates were high, at rates of one hundred and thirty-two deaths per every one thousand births; most of the roads were dirt, and during the rainy season they became mud and nearly impassable; and many villages were reachable only by foot on or horseback. Some of the more remote communities had gone more than ten years without a visit from a priest (Pélach y Feliu 1972).

By the time of his writing, the pilgrimage to Cocharcas was a shadow of what it had been during its colonial heyday. At the time, Cocharcas had a population of about 500; the roads which linked Cocharcas with the rest of the country were only built in the 1950s (1972: 12–13). The church and its environs were in a decayed state; for instance, he cites that there used to be, in front of the church, a great square with accommodations available for pilgrims, but now “unfortunately, only seven remain standing on the left. The rest are in ruins or have collapsed and disappeared” (1972: 13).

He sought to revive the shrine, through his 1972 book, and through the organization in 1974 of the first Eucharistic Marian Congress in Cocharcas; in 1998, as part of the 400 year anniversary celebrations of the founding of the shrine, the second such Congreso was held. The 1972 volume served, especially, to praise the pilgrimage and to elevate the figure of Sebastian Quimichi as a modern model for Catholics in Abancay to emulate (Hyland n.d.). In his account of the shrine, he describes Cocharcas as “one of the most famous in the Andes, and through the centuries it has been a true luminous beacon that has illuminated and radiated the Christian faith to many past generations” (Pélach y Feliu 1972, p. 4). His praise continued in his memoirs, published in 2005 after his retirement, where he described Quimichi himself as “cheerful and playful; a young man of sincere, firm and documented faith, and for this was virtuous and devoted” (1972: 9). He was a man “[in whose life] Saint Mary was consistently involved...to the point that, with every day that passed, Sebastian Quimichu was ever happier and more generous” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1308–1309). He attributes the rapid spread of the Virgin’s fame to the beauty of the image (carved by an indigenous sculptor), to the miracles worked by her, and also to the “good example of Quimichu” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1324–1325).

He also reinforces the status of Cocharcas in Apurímac, and emphasizes that Quimichi had been one of their own. He speaks of how “Our Lady wanted to be present in this land of Apurimac” (1972: 8) and that is why only a scant century after the initial evangelization, God had called upon a “poor and simple Indian” (1972: 8) to make this possible. At the same time, he also locates the discussion in his 1972 volume within the context of the Council. He follows his assertion that “to read the story of Sebastian Quimichi and the trials which the image of the Virgin of Cocharcas faced, until we were able to be in her spectacular sanctuary, makes us realize that there was special providence from God, so that we could have this venerated image in Apurímac, influencing our Christian faith just as it influenced the faith of so many generations” (1972: 44), with a lengthy quotation from a homily given by Paul VI in February 1965 where he had spoken in favor of the veneration of Mary. Elsewhere, he also quotes at length from the text of Lumen gentium, in an implicit support of the fervent faith which Andean Catholics show to the Virgin as being doctrinally sound.

Indeed, countering notions of Andean Catholicism as shallow, inauthentic, or otherwise inferior, Mons. Enrique describes the inspiring faith of the indigenous Andeans who undertake the pilgrimage, saying that “he who does not go one year, because someone must stay [at home], goes the next year. As often happens in such cases, it is the simple folk who motivate us to undertake the journey. Their example seems to tell us that faith can move mountains. This is an experience that so many generations of pilgrims to Cocharcas have left us.” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1336–1338). This esteem extends to the Andean customs surrounding the pilgrimage, where he describes “an ancient tradition and very characteristic of the popular piety surrounding Cocharcas…that of Quimichus [pilgrims] carrying on their shoulders a small trunk which holds inside a Reina Chica or Reina Grande (small copies of the original [image of the Virgin]). To the sound of music that all the devotees recognise, [they travel] from community to community for months, above all when the feast of 8 September approaches, in order to collect alms and, more importantly, to offer the image of the Virgin the devotion of the faithful” (Pèlach Feliú 2005: Kindle Locations 1338–1342). This tradition was immortalized by the famed Peruvian writer and anthropologist José María Arguedas in his 1950s novel Deep Rivers, but has received scant anthropological attention since then.

Today, the shrine at Cocharcas is one which is once again thriving—a fact which is locally attributed in significant part to Mons. Enrique’s past concerted efforts—and institutionally supported by both the Church and the state. The cult of Sebastian Quimichi continues to be encouraged, too. The story of Quimichi’s founding role in the shrine to the Virgin of Cocharcas is taught regularly in Sunday catechism; prayer cards featuring Quimichi’s image circulate still in the diocese. The pilgrimage to Cocharcas attracts thousands annually, overflowing the town; the procession of the image is thronged and densely packed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The procession of Virgin of Cocharcas on her feast day, in Cocharcas. Photo by author.

Priests from all over the diocese attend the Virgin’s feast day, bringing with them contingents from their own parishes. Additionally, the custom described by Mons. Enrique, of the Quimichus and the Reina Chica and Reina Grande, persists today. On her feast day, the Quimichus still set out at down on foot from Uripa (the nearest parish to Cocharcas), carrying with them the little box containing the Reina Chica, in order that they might arrive at Cocharcas in time for dusk. Below (Figure 3) is a photo from a rest stop along the pilgrimage route in 2015: at this point, the box had been opened to allow for pilgrims to queue up to kneel in front of her, reach into the box, and pray—as the man in the photo is doing. Inside is a miniature copy of the image of the Virgin—and to her left is a small figure representing the Quimichus who carry the Virgin.

Figure 3.

A man kneels and prays as he reaches into the box containing a miniature version of the image of the Virgin of Cocharcas. Photo by author.

Furthermore, the importance of shrine at Cocharcas is now nationally recognized—hugely important in a nation where to be Peruvian is almost necessarily to be Catholic, and so where dismissing Andean Catholicism implicitly also dismisses Andeans as second-class citizens. In 2008, in an agreement with the diocese of Abancay and local Andean authorities, the Ministry of Culture officially began a restoration and reconstruction of the colonial church. It took eleven years and nearly four million US dollars to complete, being a complex and delicate project—it had originally been projected to take three years, and approximately one and a half million US dollars.8 The handover of the now-restored church in 2019 was attended by various government officials and the current bishop of Abancay, where the head of the Ministry for Culture reflected in her speech on the importance of the site and the interests of the state in preserving it.9

4. Conclusions

Oral histories and ethnographic literature on the relationship between Andean Catholics and the Church in the years before Vatican II paint a dour and distant picture, wherein Andean Catholics were often looked down upon, excluded from the sacraments, and rarely visited by priests. Such circumstances still occur; but in Abancay, they are largely no longer current lived experience. In the decades following Vatican II, the second bishop of Abancay—appointed a mere three years after the closure of the Council—made concerted efforts towards the achievement of two projects: the founding of a seminary, and the revival of the Marian shrine to the Virgin of Cocharcas. In the years since the end of the internal conflict, public religious life has been able to resume, flowering in the form of a generation of native clergy, who embody an institutional relationship between the church and indigenous Catholics based not on antipathy and mistrust but rather a shared language and cultural background. This native clergy also support the now-revived major pilgrimage site of the Virgin of Cocharcas coupled with the elevation of Sebastian Quimichi, seeking to raise up Quimichi as an Andean paragon of Catholic piety. This revival has included, rather than excluded, traditional Andean customs surrounding the pilgrimage, and has facilitated religious and state institutional support of the pilgrimage.

Funding

This research was funded by Santander and the University of St Andrews.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of St Andrews Teaching and Research Ethics Committee (reference number SA11439, approved on 31 March 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Father Simón Villafuerte Herhuay for his assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abercrombie, Thomas. 1998. Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History Among an Andean People. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Brian, and Charles Stanish. 2001. Ritual and Pilgrimage in the Ancient Andes: The Islands of the Sun and the Moon. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Ronald. 1994. Peasant responses to Shining Path in Andahuaylas. In Shining Path of Peru. Edited by David Scott Palmer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Canessa, Andrew. 2012. Intimate Indigeneities: Race, Sex, and History in the Small Spaces of Andean Life. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carboni, Romolo. 1963. Peru’s need: Priests. The Furrow 14: 343–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Francis. 1954. The Holy See on forming a native clergy—1909–1953. Philippine Studies 2: 149–64. [Google Scholar]

- de la Costa, Horacio. 1947. The development of the native clergy in the Philippines. Theological Studies VIII: 219–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Olivia. 2000. To Make the Earth Bear Fruit: Essays on Fertility, Work and Gender in Highland Bolivia. London: Institute of Latin American Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, Sabine. 1998. Illegitimacy and racial hierarchy in the Peruvian priesthood: A seventeenth-century dispute. The Catholic Historical Review 84: 431–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, Sabine. n.d. The shrine to Our Lady of Cocharcas. Unpublished article.

- Isbell, Billie Jean. 1978. To Defend Ourselves: Ecology and Ritual in an Andean Village. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klaiber, Jeffrey. 1975. Religion and revolution in Peru: 1920–1945. The Americas 31: 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarén, Peter. 1990. Peru’s Great Divide. The Wilson Quarterly 14: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orta, Andrew. 2002. ‘Living the past another way:’ Reinstrumentalized missionary selves in Aymara mission fields. Anthropological Quarterly 75: 707–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pèlach Feliú, Enrique. 2005. Abancay. Un Obispo en los Andes Peruanos. Madrid: Rialp, Kindle edition. [Google Scholar]

- Pélach y Feliu, Enrique. 1972. Nuestra Señora de Cocharcas. Abancay: Diocese of Abancay. [Google Scholar]

- Salles-Reese, Verónica. 1997. From Viracocha to Copacabana: Representations of the Sacred at Lake Titicaca. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sallnow, Michael. 1987. Pilgrims of the Andes: Regional Cults in Cusco. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Ugarte, Rubén. 1947. Historia del Culto de María en Iberoamérica y de sus Imágenes y Santuarios más Celebrados. Buenos Aires: Editorial Huarpes. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Donald, and Rudolph Bell. 1982. Saints and Societies: The Two Worlds of Western Christendom. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weismantel, Mary. 2001. Cholas and Pishtacos: Stories of Race and Sex in the Andes. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | http://censos.inei.gob.pe/censos1993/redatam/ (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

| 2 | http://censos2017.inei.gob.pe/redatam/ (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

| 3 | http://censos.inei.gob.pe/censos1993/redatam/ (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

| 4 | http://www.congreso.gob.pe/Docs/files/CONSTITUTION_27_11_2012_ENG.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

| 5 | https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19631204_sacrosanctum-concilium_en.html (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

| 6 | https://censos2017.inei.gob.pe/redatam/ (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

| 7 | Different authors vary on the spelling of his name as “Quimichi” or “Quimichu”. For the sake of consistency, I use “Quimichi” throughout the article, except for in quotations where the original author used an alternative spelling. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | https://diariocorreo.pe/edicion/cusco/antiguo-santuario-de-cocharcas-fue-restaurado-integralmente-fotos-927973 (accessed on 10 February 2021). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).