Mosque Architecture in Cyprus—Visible and Invisible Aspects of Form and Space, 19th to 21st Centuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Muslim Culture in Cyprus

1.1. 19th Century to 1960: From the Late Ottoman Rule to the End of British Colonial Rule

1.2. 1960–1974: Cyprus’s Independence Years to the Division of the Island

1.3. 1974–2001: North Cyprus before Turkey’s Governments Led by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey

1.4. 2002–2021: North Cyprus during Governments Led by the AKP in Turkey

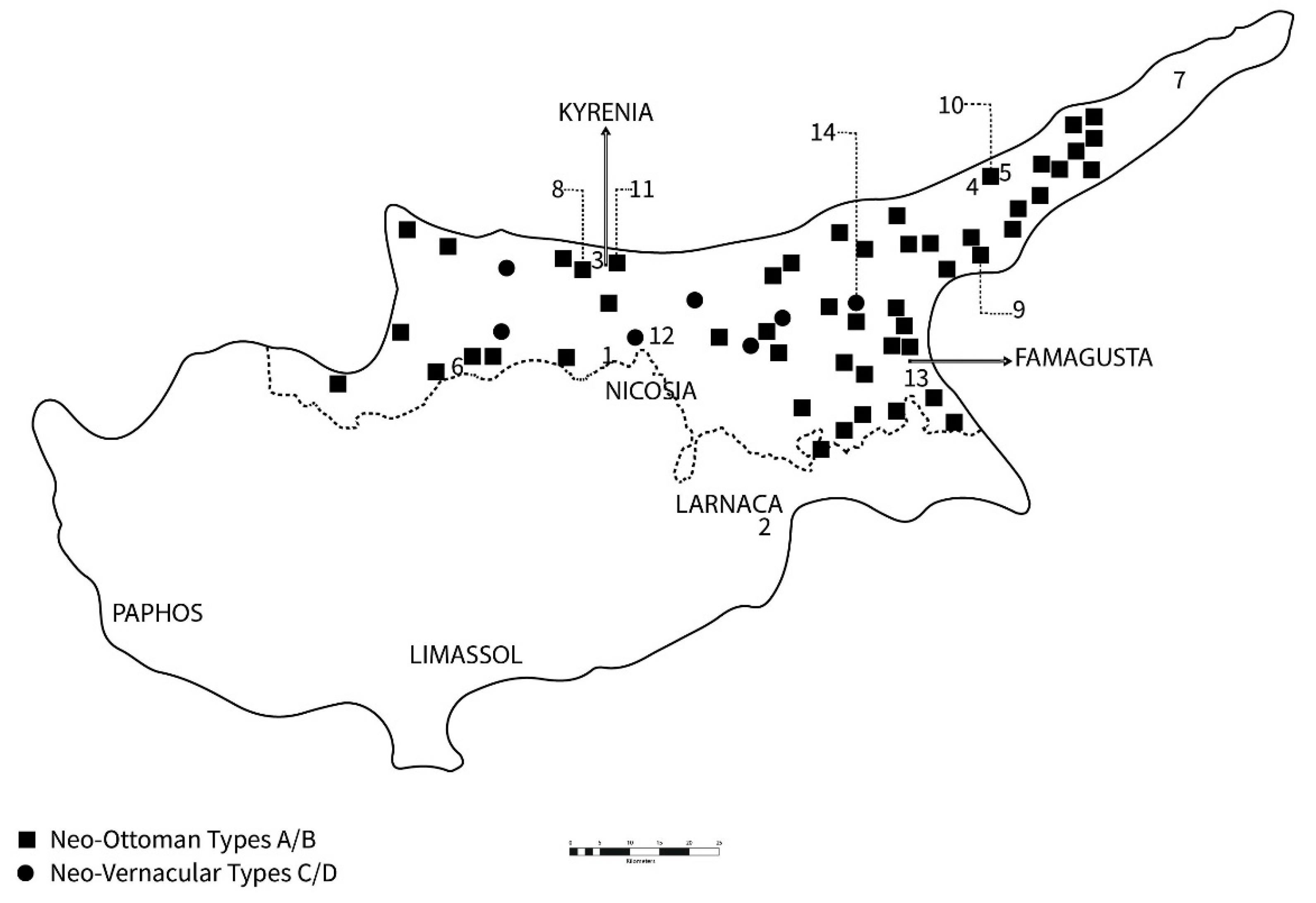

2. Mosque Architecture in Cyprus, 19th to 21st Centuries: Aim and Method of Research

3. Mosque Architecture on Cyprus, 19th to 21st Centuries: Discussion and Results

3.1. The 19th Century: Mosques in Cyprus from the (Late) Ottoman Period and the Beginning of British Rule

3.2. Mosques in Cyprus from the First Decades of the British Period at the Turn from the 19th to 20th Centuries

3.3. The 1920s to 1974: Mosques in Cyprus from the Rise of Kemalism to the Division of the Island

3.4. 1974 to 2001: Mosques in North Cyprus before Turkey’s AKP-Led Governments

3.5. 2002 to 2021: Mosques in North Cyprus during Turkey’s AKP-Led Governments

3.5.1. Neo-Ottomanism

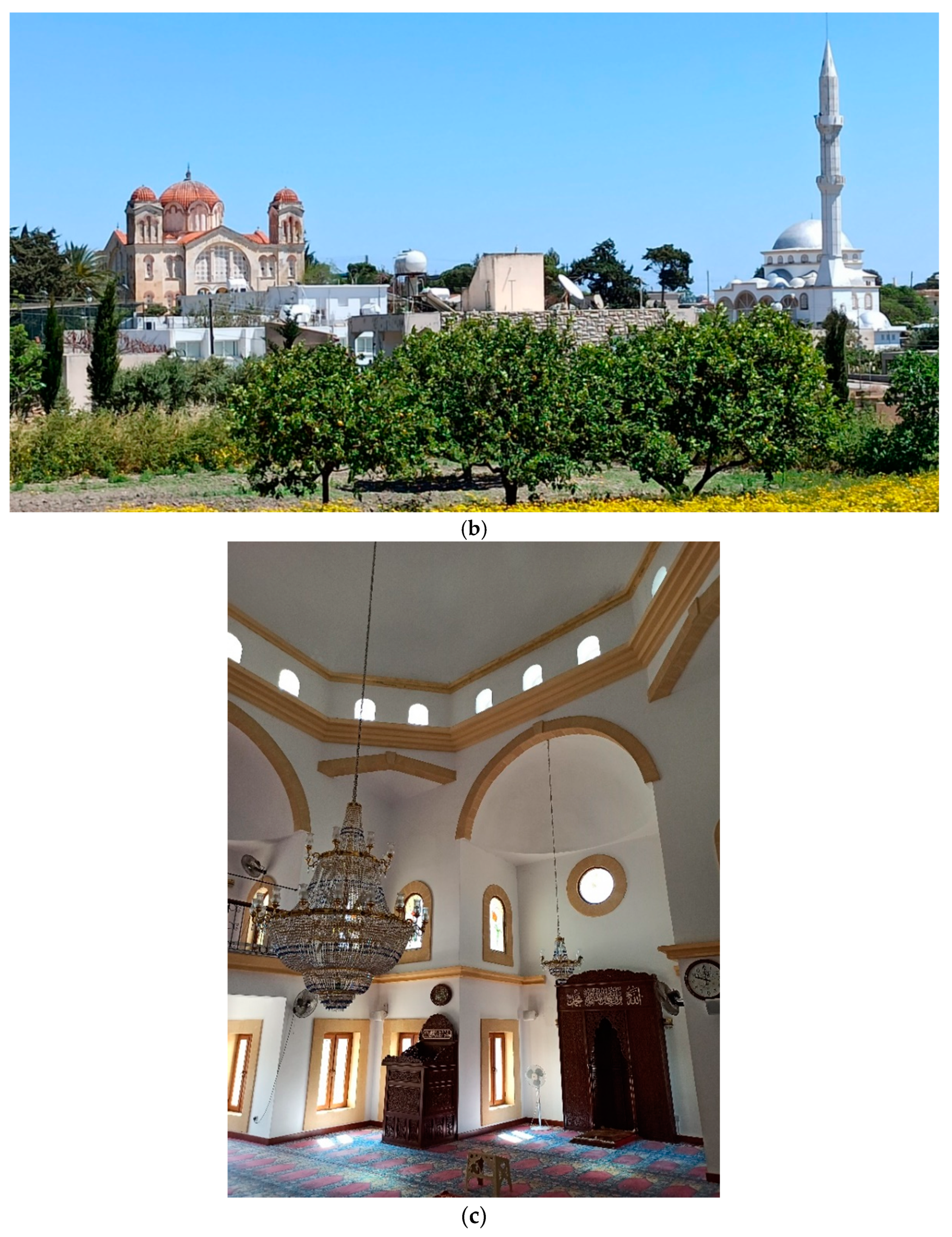

3.5.2. Resilience of the Modern and of the Cypriot Vernacular

4. Main Results and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Realized in 1932 and closed in 1949 due to lack of students, see An (2016, p. 7). |

| 2 | See for the hotel: Kiessel (2019, p. 288 note 74). |

| 3 | On the renaming: Keshishian (1990, p. 174). |

| 4 | While three further mosques, including the Nurettin Ersin Paşa mosque in Kyrenia, completed in 1999, were built by other foundations. |

| 5 | Especially after 1983, when the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus (TRNC) was declared, which is recognized only by Turkey. |

| 6 | There were 49 mosques built under the supervision of the Evkaf Construction Department, in addition to the Polat Paşa, the Selim II, and Hala Sultan mosques in Famagusta and Nicosia-Haspolat from 2003, 2017, and 2019, respectively, built by other foundations. |

| 7 | See above on the development of a Turkish identity among Turkish Cypriots (especially: Hatay 2008, pp. 148–49; Nevzat and Hatay 2009, pp. 917–19). |

| 8 | The domed square unit typical of Ottoman-Anatolian mosque architecture goes back to the 14th century (see Hillenbrand 2010, pp. 257–58). |

| 9 | For further images, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arab_Ahmet_Mosque; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hala_Sultan_Tekke (accessed on 22 October 2021). |

| 10 | On the Selimiye mosque, Edirne, see Hillenbrand (2010, pp. 264, 266, fig. 200), and for further images see https://www.archnet.org/sites/1941 (accessed on 22 October 2021). |

| 11 | For images, see https://www.lefkosabelediyesi.org/tarihi-ve-turistik-yerler/sarayonu-camii (accessed on 22 October 2021). |

| 12 | For the major towns, such as Nicosia, the internationally known names are used. As for the villages, the Turkish name is put first, followed by its Greek equivalent if a village is located in North Cyprus, whereas the Greek name is put first, followed by its Turkish equivalent if the location is in the Republic of Cyprus. |

| 13 | See for Photiadis’s church building activity in the next section. |

| 14 | See also An (2016, pp. 8–9), who mentions the addition of minarets to the mosques of Krini and Agridi. |

| 15 | |

| 16 | See the image on http://www.kktcdinhizmetleri.com/tr/camilerimiz (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 17 | According to the Evkaf Construction Department 2021 and according to http://www.kktcdinhizmetleri.com/tr/camilerimiz (accessed on 27 July 2021), it was built in 1982. |

| 18 | See further images on https://www.kibrispostasi.com/c35-KIBRIS_HABERLERI/n117167-Kibrista-dinler-arasi-iletisim (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 19 | Its design goes back at least to 1996, according to http://www.kktcdinhizmetleri.com/tr/camilerimiz (accessed on 20 October 2021). |

| 20 | See on the Selimiye mosque, Hillenbrand (2010, pp. 264, 266, fig. 200), and for further images see https://www.archnet.org/sites/1941 (accessed on 22 October 2021). |

| 21 | It is also possible to read the building as a reduced version of early Ottoman mosques, similar to those in Bursa, where three fully domed spaces (instead of semi-domed “exedrae”) flank the central space and form an inverted “T”. See Stierlin (1998, pp. 85–86, 92). |

| 22 | See also Hammond (2016, p. 142) on Eyüp’s transformation in contemporary Istanbul during the 1990s and 2000s that helped ‘to make Islam more visible and tangible’. |

| 23 | Information is from the construction company Kurtsan Inşaat, Famagusta, and from the Evkaf Construction Department, Nicosia (2021). |

| 24 | http://www.kktcdinhizmetleri.com/tr/camilerimiz (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 25 | For religious place making (in a Muslim-majority context) the development of the religious material landscape (mosques, medreses, tekkes, cemeteries) and the secular built environment (for example hamams, bazaars and hans), the maintenance and restoration of these landscapes, religious rituals such as pilgrimage, social rituals and tourism may play a role, see Hammond (2016, pp. 18–22). |

| 26 | For images see https://tdv.org/tr-TR/proje/kktc-lefkosa-hala-sultan-camii/ (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 27 | A complex of buildings belonging to a pious foundation (vakıf) the center of which is a mosque. Includes usually a school (medrese). |

| 28 | http://www.kktcdinhizmetleri.com/tr/camilerimiz (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 29 | https://tdv.org/tr-TR/proje/kktc-lefkosa-hala-sultan-camii/ (accessed on 27 July 2021); for images of the Selimiye mosque in Edirne see https://www.archnet.org/sites/1941 (accessed on 22 October 2021). |

| 30 | http://www.kktcdinhizmetleri.com/tr/camilerimiz (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 31 | Information is from the Project Affairs Directorate (Proje Işleri Müdürlüğü), Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta (2021). |

| 32 | https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/faisal-mosque-islamabad (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 33 | https://mosqpedia.org/en/mosque/305 (accessed on 27 July 2021). |

| 34 | Information is from Evkaf Construction Department, Nicosia, and Kurtsan construction, Famagusta (2021). |

References

- An, Ahmet Djavit. 2016. The Development of Turkish Cypriot Secularism and Turkish Cypriot Religious Affairs. Eastern Mediterranean Policy 8: 1–11. Available online: https://cceia.unic.ac.cy/wp-content/uploads/EMPN_8.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Asmussen, Jan. 2008. Cyprus at War. Diplomacy and Conflict during the 1974 Crisis. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Bağişkan, Tuncer. 2009. Ottoman, Islamic and Islamised Monuments in Cyprus. Nicosia: Cyprus Turkish Education Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Coureas, Nicholas, Gilles Grivaud, and Chris Schabel. 2012. Frankish & Venetian Nicosia 1191–1570. In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Michaelides Demetrios. Nicosia: Rimal Publications, pp. 111–230. [Google Scholar]

- Dayıoğlu, Ali, and Mete Hatay. 2014. Cyprus. In Yearbook of Muslims in Europe—Volume 7. Edited by Jorgen S. Nielsen, Ahmet Alibašić and Egdūnas Račius. Leiden: Brill, pp. 153–75. [Google Scholar]

- Evkaf Construction Department (=Vakıflar Idaresi–Inşaat Şube Müdürlügü). 2021. Verbal and Written Information on Construction Processes, -Details and -Statistics, Kindly Provided to the Authors. General Contact. Available online: http://www.evkaf.org/site/default.aspx (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Grabar, Oleg. 2005. Die Moschee. In Islam. Kunst und Architektur. Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius. Köln: Könemann, pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, Annette. 2005. Architektur und Kunst. In Islam. Kunst und Architektur. Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius. Köln: Könemann, pp. 592–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Timur Warner. 2016. Mediums of Belief: Muslim Place Making in 20th Century Turkey. Ph.D. thesis, University of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90w4p389 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Hatay, Mete. 2008. The problem of pigeons: Orientalism, xenophobia, and a rhetoric of the ‘local’ in North Cyprus. The Cyprus Review 20: 145–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hatay, Mete. 2015. ‘Reluctant’ Muslims? Turkish Cypriots, Islam, and Sufism. The Cyprus Review 27: 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, Richard. 2010. Islamic Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Ionas, Ioannis. 2003. La Maison Rurale de Chypre (XVIIIe–XX Siècle). Aspects et Techniques de Construction, 2nd ed. Nicosia: Centre de Recherche Scientifique de Chypre. [Google Scholar]

- Keshishian, Kevork K. 1990. Nicosia, Capital of Cyprus Then and Now, 2nd ed. Nicosia: Moufflon Book and Art Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Kiessel, Marko. 2019. Famagusta on Cyprus and the Sea: Hotel Architecture, Urban Development and Tourism during the British Colonial and Early Postcolonial Period. In Famagusta Maritima. Mariners, Merchants, Pilgrims and Mercenaries. Edited by Michael J. K. Walsh. Brill’s Studies in Maritime History. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 7, pp. 264–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kiessel, Marko, and Asu Tozan. 2014. Orthodox Church Architecture in the Northern Districts of Cyprus from the mid-19th century to 1974. Prostor, a Scholarly Journal of Architecture and Urban Planning 22: 160–73. [Google Scholar]

- Markides, Diana. 2012. Nicosia under British Rule. In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Demetrios Michaelides. Nicosia: Rimal Publications, pp. 325–402. [Google Scholar]

- Nevzat, Altay, and Mete Hatay. 2009. Politics, Society and the Decline of Islam in Cyprus: From the Ottoman Era to the Twenty-First Century. Middle Eastern Studies 45: 911–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacostas, Tassos C. 1999. Byzantine Cyprus. The Testimony of its Churches, 650–1200. Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulou-Egoumenidou, Euphrosyne. 2012. Nicosia under Ottoman Rule 1570-1878-Part II. In Historic Nicosia. Edited by Demetrios Michaelides. Nicosia: Rimal Publications, pp. 265–324. [Google Scholar]

- Schaar, Kenneth W., Michael Given, and George Theocharous. 1995. Under the Clock. Colonial Architecture and History in Cyprus, 1878–1960. Nicosia: Bank of Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, Thomas. 2015. Turkey’s mosque-building diplomacy. Al-Monitor. Available online: https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2015/02/turkey-mosque-building-soft-power.html (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Sonmez, Mustafa. 2021. Turkey’s religious agency grows even richer, more powerful. Al-Monitor. Available online: https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/05/turkeys-religious-agency-grows-even-richer-more-powerful (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Stierlin, Henri. 1998. Turkey. From the Selçuks to the Ottomans. Köln: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Tastekin, Fehim. 2021. Erdogan furious as his Islamic ambitions stumble in Turkish Cyprus. Al-Monitor. Available online: https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/04/erdogan-furious-his-islamic-ambitions-stumble-turkish-cyprus (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Tozan, Asu. 2008. Urbanization and Architecture in Cyprus as an Example of Colonial Modernization (1878–1960). Ph.D. thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Zencirci, Gizem. 2014. Civil Society’s History: New Constructions of Ottoman Heritage by the Justice and Development Party in Turkey. European Journal of Turkish Studies—Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey 19: 1–20. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/ejts/5076 (accessed on 27 July 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Type/Style | Main Mosques Discussed in Text | Features/Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Vernacular (19th to 20th centuries) | Yedikonuk/Ephtakomi | Mosque function abandoned. Rectangular prayer hall, flat saddle roof, no minaret, two inner arches from prayer to front wall, three bays, mihrab in central bay. |

| Kyrenia, Ağa Cafer Paşa mosque | Rectangular prayer hall, flat saddle roof, minaret, arcaded front portico with three pointed arches, three inner arches from prayer- to front wall, four inner bays. | |

| Neo-vernacular (since 2015) | Type C: Akova/Gypsou | Rectangular prayer hall, asymmetric saddle roof, minaret, arcaded front portico with five pointed arches, four inner pointed arches from prayer to front wall, five bays, mihrab in central bay, portico, and details like window frames/arches cladded with imitation of ashlar stones. |

| Ottoman (16th and 19th centuries) | Nicosia, Arab Ahmet Paşa mosque | Square prayer hall, octagonal tambour with four arched windows alternating with four semidomes, central dome, minaret, arcaded front portico with three pointed arches and three small domes. |

| Larnaca, mosque of Hala Sultan Tekke | Square prayer hall, octagonal tambour with a semidome above every corner of the square, central dome, minaret, arcaded front portico with four pointed arches. | |

| Neo-Ottoman (since 1998) | Type B: Kyrenia, Nurettin Ersin Paşa mosque, Yedikonuk/Ephtakomi, Doğanköy (Kyrenia) | Square prayer hall with a central dome and lateral/flanking extensions, covered by semidomes and small domes, arcaded front portico with three pointed arches/two lateral domes, one or two minarets, historicizing exterior and interior detailing, such as extensive interior blue-colored tiling (Kyrenia), window frames, cornices, arches cladded with imitation of (local) ashlar stone. |

| Type A: Kaleçik/Gastria | Square prayer hall, octagonal tambour, minaret, central dome, arcaded front portico with three (pointed) arches and three domes, historicizing exterior and interior detailing, such as window frames, cornices, arches cladded with imitation of (local) ashlar stone. | |

| Haspolat/Mia Milia, Hala Sultan mosque (2019) | Replica of the Selimiye mosque, Edirne, Turkey. | |

| Church conversion (after 1974) | Yedikonuk/Ephtakomi, St. George Zümrütköy/Katokopia, BVM | Historicist neo-Byzantine style. Mosque function abandoned. Replaced by neo-Ottoman mosque, type B. Modern neo-Byzantine style. Functioning as mosque. Campanile functions as minaret, mihrab installed in southern cross-arm. |

| Modern (1991 and 2017) | Dipkarpaz/Rizokarpaso Famagusta, Selim II. mosque | Square prayer hall, central dome over tambour, arcaded front portico with five pointed arches and five small domes, minaret, rather modern aesthetic. Square prayer hall, pyramidal roof with exposed steel structure, naturally lighted mihrab niche, minaret. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiessel, M.; Tozan, A. Mosque Architecture in Cyprus—Visible and Invisible Aspects of Form and Space, 19th to 21st Centuries. Religions 2021, 12, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121055

Kiessel M, Tozan A. Mosque Architecture in Cyprus—Visible and Invisible Aspects of Form and Space, 19th to 21st Centuries. Religions. 2021; 12(12):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121055

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiessel, Marko, and Asu Tozan. 2021. "Mosque Architecture in Cyprus—Visible and Invisible Aspects of Form and Space, 19th to 21st Centuries" Religions 12, no. 12: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121055

APA StyleKiessel, M., & Tozan, A. (2021). Mosque Architecture in Cyprus—Visible and Invisible Aspects of Form and Space, 19th to 21st Centuries. Religions, 12(12), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121055